INTRODUCTION

Schistosomiasis is caused by nematode worms of the Schistosoma genus, including Schistosoma mansoni, Schistosoma japonicum, and Schistosoma haematobium as the main species. It is an endemic disease in tropical and subtropical regions.1 At least 230 million people worldwide are infested with Schistosoma species.2 In Brazil, approximately 25 million people live in areas at risk for S mansoni.3

Schistosoma eggs accumulate in the submucosa of the colon and induce inflammation, which triggers a severe granulomatous reaction that is complicated by microabscesses, ulceration, nodules, polyps, and hyperplasia.4 Along with hyperplasia, it has been observed that S japonicum eggs induce colorectal carcinoma (CRC).5,6

Besides CRC, S japonicum has also been implicated in liver cancer development.4 In addition, an association between S haematobium and bladder cancer has also been described.7 However, the association between S mansoni and CRC is scarce in the literature. In patients with S mansoni–associated CRC, patients are younger, their tumors are multicentric and present with mucinous histology, and there is a greater risk of lymph node metastasis and microsatellite instability (MSI).8 We report two patients with concurrent diagnosis of CRC and intestinal schistosomiasis and the potentially implicated carcinogenesis steps.

CASE REPORTS

The first patient was a 45-year-old woman who presented with abdominal pain, weight loss, and diarrhea. She underwent a colonoscopy in October 2014, which revealed a 3-cm tumor in her cecum. A right colectomy was performed in January 2015, and a well-differentiated mucinous adenocarcinoma of 2.5 × 1.5 × 1.5 cm invading into the muscularis propria was identified. No perineural or lymphovascular invasion was observed, but a mild tumor inflammatory infiltrate was present. Margins were free, and metastasis to one of 24 lymph nodes was documented. Ileal schistosomiasis was found in the specimen. MSI was confirmed by immunohistochemistry (loss of MLH1 and PMS2). All RAS mutations were negative. She received 6-month adjuvant capecitabine- and oxaliplatin-based chemotherapy. Last follow-up visit was on June 13, 2016.

The second patient was a 47-year-old man who had a personal history of hepatosplenic schistosomiasis. In 2012, he underwent a right hemicolectomy as a result of complications of appendicitis. In March 2014, splenectomy and an esophageal varices clamp were performed as a result of GI hemorrhage. In November 2014, he presented with diarrhea, and colonoscopy showed a 2-cm tumor next to the ileum–transverse colon anastomosis. In March 2015, the specimen analyzed from a segmental colectomy showed a 3.5 × 1.8 cm mucinous moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma infiltrating subserosa, with free margins, presence of lymphovascular invasion, no perineural infiltration, and a mild lymphocytic infiltrate observed. No lymph nodes were identified in the specimen, but a granulomatous reaction in response to Schistosoma eggs in his ileum and colonic mucosa and Merkel diverticula were described by the pathologist. MSI was negative by immunohistochemistry, but exon 2 KRAS mutation (c.38G>A:p.G13D) was identified. Because of his comorbidities, he did not receive adjuvant chemotherapy. Last follow-up visit was on June 13, 2016.

In both patients, KRAS/NRAS exons 2, 3, and 4 were amplified by polymerase chain reaction, and second-generation sequencing was performed using MiSeq (Illumina, San Diego, CA). The patients were tested for MSI using the immunohistochemistry antibodies MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, and PMS2.

DISCUSSION

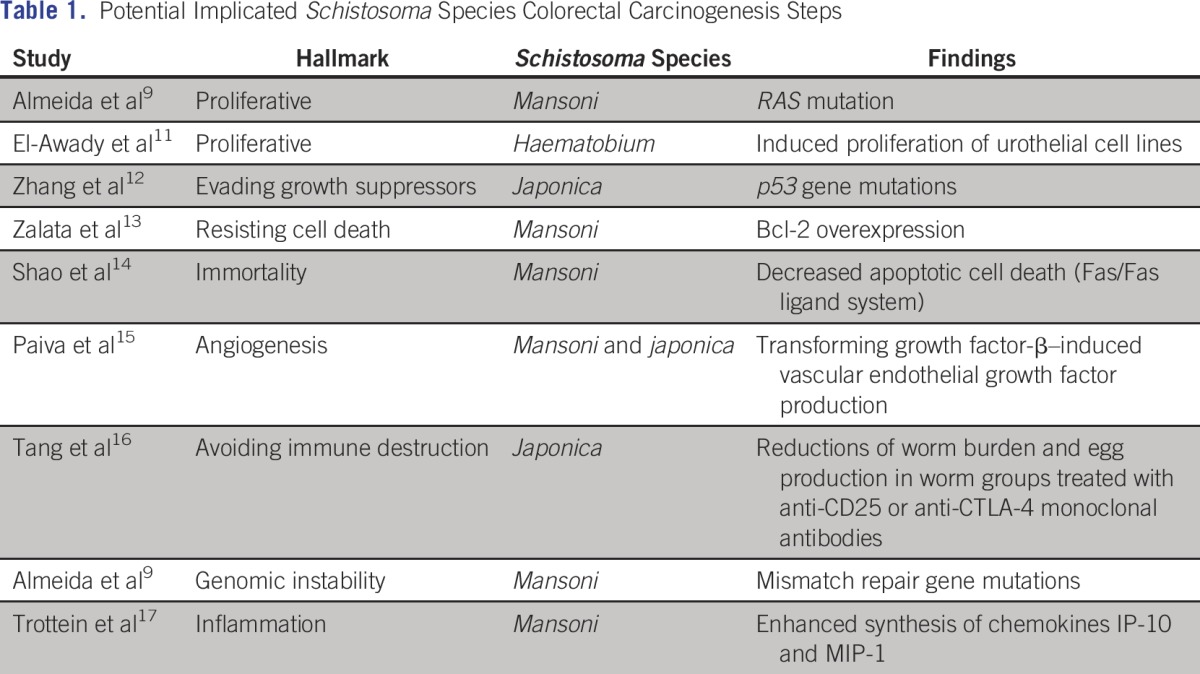

Whether Schistosoma induces carcinogenesis and its steps is not clear yet. Hanahan and Weinberg10 have proposed six hallmarks of cancer that they define as “distinctive and complementary capabilities that enable tumor growth and metastatic dissemination.” These include sustained proliferative signaling, evading growth suppressors, resisting cell death, enabling replicative immortality, inducing angiogenesis, and activating invasion and metastasis. In addition to these six hallmarks, Hanahan and Weinberg10 outline two emerging hallmarks and two enabling characteristics that make it possible for tumor cells to acquire the core hallmarks. The two emerging hallmarks are deregulating cellular energetics and avoiding immune destruction. The two enabling characteristics are properties of cancer cells that facilitate the acquisition of the hallmarks. The first of these characteristics is genomic instability, which enables the acquisition of the multiple mutations required for multistep tumorigenesis. The second enabling characteristic is tumor-promoting inflammation, which reflects the rapidly advancing concept that inflammatory responses can actually facilitate tumor initiation and progression in some contexts.10 According to these hallmarks, we found in the literature some evidence of the carcinogenesis steps involving schistosomiasis (Table 1).

Table 1.

– Potential Implicated Schistosoma Species Colorectal Carcinogenesis Steps

In conclusion, the age of the patients and their mucinous subtype were in accordance with the literature.8 RAS mutation, along with the presence of MSI, may be implicated in the carcinogenesis of S mansoni–associated CRC or represent coincidental events. If the first is correct, it would determine treatment and prognosis implications among patients infested with S mansoni. Because Schistosoma may be associated with colorectal carcinogenesis, it is necessary to create a specific protocol for screening of CRC in Schistosoma-endemic areas.18

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Administrative support: Gustavo Fernandes Godoy Almeida, Maxwell Alex de Lima Moura, Lais Neares Barbosa Ribeiro, Bruno Rolim de Brito, Ana Lucia Coutinho Domingues

Provision of study materials or patients: Gustavo Fernandes Godoy Almeida, Paula Carvalho de Abreu e Lima, Joao Bosco Oliveira Filho, Mariana Montenegro de Melo Lira, Marcelo do Rego Maciel Souto Maior, Ana Lucia Coutinho Domingues

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/jco/site/ifc.

Gustavo Fernandes Godoy Almeida

Speakers' Bureau: Mundipharma

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Mundipharma

Filipe Wanick Sarinho

No relationship to disclose

Paula Carvalho de Abreu e Lima

No relationship to disclose

Joao Bosco Oliveira Filho

Honoraria: Merck, AstraZeneca, Novartis

Consulting or Advisory Role: AstraZeneca, Novartis

Research Funding: Novartis

Maxwell Alex de Lima Moura

No relationship to disclose

Lais Neares Barbosa Ribeiro

No relationship to disclose

Bruno Rolim de Brito

No relationship to disclose

Mariana Montenegro de Melo Lira

No relationship to disclose

Marcelo do Rego Maciel Souto Maior

No relationship to disclose

Ana Lucia Coutinho Domingues

No relationship to disclose

REFERENCES

- 1.Hosho K, Ikebuchi Y, Ueki M, et al. Schistosomiasis japonica identified by laparoscopy and colonoscopy. Dig Endosc. 2010;22:133–136. doi: 10.1111/j.1443-1661.2010.00935.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Colley DG, Bustinduy AL, Secor WE, et al. Human schistosomiasis. Lancet. 2014;383:2253–2264. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61949-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ministerio da Saude, Secretaria de Vigilancia em Saude: Guia de Vigilancia Epidemiologica (ed 7). Brasilia, Brazil, Ministerio da Saude, 2012.

- 4.Gray DJ, Ross AG, Li YS, et al. Diagnosis and management of schistosomiasis. BMJ. 2011;342:d2651. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d2651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Matsuda K, Masaki T, Ishii S, et al. Possible associations of rectal carcinoma with Schistosoma japonicum infection and membranous nephropathy: A case report with a review. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 1999;29:576–581. doi: 10.1093/jjco/29.11.576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu W, Zeng HZ, Wang QM, et al. Schistosomiasis combined with colorectal carcinoma diagnosed based on endoscopic findings and clinicopathological characteristics: A report on 32 cases. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2013;14:4839–4842. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2013.14.8.4839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mostafa MH, Sheweita SA, O’Connor PJ. Relationship between schistosomiasis and bladder cancer. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1999;12:97–111. doi: 10.1128/cmr.12.1.97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-8-68. Salim OEH, Hamid HKS, Mekki SO, et al: Colorectal carcinoma associated with schistosomiasis: A possible causal relationship. World J Surg Oncol 8:68, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Almeida GFG, Mattos LAR Jr, Brito BR, et al: DNA repair defect and RAS mutation in Schistosoma mansoni–associated colorectal cancer patients: Carcinogenesis steps or mere coincidence? J Clin Oncol 34, 2016 (abstr e23279) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: The next generation. Cell. 2011;144:646–674. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.El-Awady MK, Gad YZ, Wen Y, et al. Schistosoma haematobium soluble egg antigens induce proliferation of urothelial and endothelial cells. World J Urol. 2001;19:263–266. doi: 10.1007/s003450100217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang R, Takahashi S, Orita S, et al. p53 gene mutations in rectal cancer associated with schistosomiasis japonica in Chinese patients. Cancer Lett. 1998;131:215–221. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(98)00154-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zalata KR, Nasif WA, Ming SC, et al. p53, Bcl-2 and C-Myc expressions in colorectal carcinoma associated with schistosomiasis in Egypt. Cell Oncol. 2005;27:245–253. doi: 10.1155/2005/547010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shao Q, Tohma Y, Ohgaki H, et al. Altered expression of Fas (APO-1, CD95) and Fas ligand in the liver of mice infected with Schistosoma japonicum and Schistosoma mansoni: Implications for liver carcinogenesis. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2002;3:361–366. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Paiva LA, Coelho KA, Luna-Gomes T, et al. Schistosome infection-derived hepatic stellate cells are cellular source of prostaglandin D₂: Role in TGF-β-stimulated VEGF production. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2015;95:57–62. doi: 10.1016/j.plefa.2015.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tang CL, Lei JH, Guan F, et al. Effect of cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 on CD4(+)CD25(+) regulatory T cells in murine schistosomiasis japonica. Exp Parasitol. 2014;136:74–78. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2013.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Trottein F, Pavelka N, Vizzardelli C, et al. A type I IFN-dependent pathway induced by Schistosoma mansoni eggs in mouse myeloid dendritic cells generates an inflammatory signature. J Immunol. 2004;172:3011–3017. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.5.3011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Konishi T, Watanabe T, Shibahara J, et al. Surveillance colonoscopy should be conducted in patients with colorectal schistosomiasis even after successful treatment of the disease. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol. 2006;19:245–246. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]