In a recent article, Lopez-Chavez et al1 reported a high mutational rate of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) in Peruvian patients (37%) that is higher than in other Latin American countries such as Mexico, Bolivia, Venezuela, and in a mixture of Latinos in the United States. High mutational rates of the EGFR gene in Peruvian patients were reported previously in independent cohorts. Mas et al2 reported a frequency of 39.3% (n = 122), and Arrieta et al3 reported a frequency of 51.1% (n = 393). Although the frequency of EGFR mutations in Peruvian patients is higher than other reports, these rates could be explained by environmental factors.

However, ancestry could also play an important role in explaining this fact. We would like to point out two events that could lead to a gene flow explaining the high prevalence of EGFR mutations in Peruvian patients. Population of the Americas in the late Pleistocene epoch by migrants from Asia through the Bering land bridge shaped the genetic pool of Native Americans. The second event occurred after slavery was abolished in Peru and a massive wave of Chinese workers reached the Peruvian coast (approximately 100,000 between 1849 and 1880), with a Peruvian population estimated at 2 million in 1850.4,5

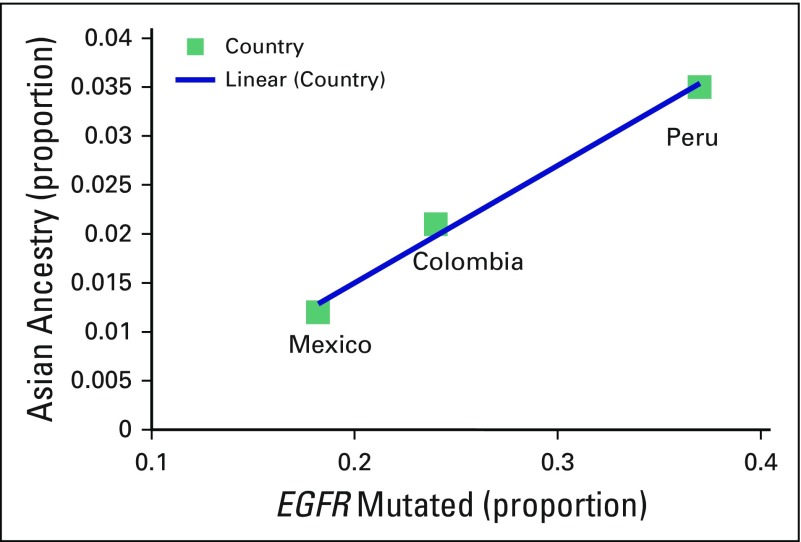

Although there are not many projects that are evaluating Asian ancestry markers in Latin American countries, data for ancestry admixture proportions for Mexico, Colombia, and Peru (0.012, 0.021, and 0.035, respectively) suggest a correlation between ancestry proportion and rate of EGFR mutations (Fig 1).1,6-8

Fig 1.

Graph showing a correlation between the proportion of Asian ancestry in Latin American countries and rates of EGFR mutations in non–small-cell lung cancer. EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor.

On the other hand, the Helicobacter pylori bacterium accompanied humans in the migration waves. These bacteria are not only a chronic pathogen in humans, but also coevolve with their hosts and have been used to trace human migration routes.9 Work by Devi et al10 with Peruvian strains of H. pylori found considerable homology with Asian strains. Another interesting fact is the high prevalence of human T-cell lymphotropic virus, ranging from 7% to 25%, in several Peruvian cities. This pattern is typical of some Asian countries such as Japan.

High rates of EGFR mutations in Peruvian patients with non–small-cell lung cancer could be a signature of Asian ancestry in the Peruvian population.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

AUTHORS’ DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO’s conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/jco/site/ifc.

Joseph A. Pinto

No relationship to disclose

Luis A. Mas

No relationship to disclose

Henry L. Gomez

No relationship to disclose

REFERENCES

- 1.Lopez-Chavez A, Thomas A, Evbuomwan MO, et al. EGFR mutations in Latinos from the United States and Latin America. J Glob Oncol. 2016;2:259–267. doi: 10.1200/JGO.2015.002105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mas L, Gómez de la Torre JC, Barletta C. Estado mutacional de los exones 19 y 21 de EGFR en adenocarcinoma de pulmón: Estudio en 122 pacientes peruanos y revisión de la evidencia de eficacia del inhibidor tirosina kinasa erlotinib. Carcinos. 2011;2:52–61. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arrieta O, Cardona AF, Martín C, et al. Updated frequency of EGFR and KRAS mutations in nonsmall-cell lung cancer in Latin America: The Latin-American Consortium for the Investigation of Lung Cancer (CLICaP) J Thorac Oncol. 2015;10:838–843. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0000000000000481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.La Torre Silva R. La inmigración China en el Perú (1850-1890). Boletín de la Sociedad Peruana de Medicina Interna 5: 1992 http://sisbib.unmsm.edu.pe/BvRevistas/spmi/v05n3/Inmigraci%C3%B3n.htm.

- 5.Gootenberg P. Población y etnicidad en el Perú republicano (siglo XIX): Algunas revisiones. Lima. 1995 http://repositorio.iep.org.pe/handle/IEP/318.

- 6.Silva-Zolezzi I, Hidalgo-Miranda A, Estrada-Gil J, et al. Analysis of genomic diversity in Mexican Mestizo populations to develop genomic medicine in Mexico. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:8611–8616. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903045106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sandoval JR, Salazar-Granara A, Acosta O, et al. Tracing the genomic ancestry of Peruvians reveals a major legacy of pre-Columbian ancestors. J Hum Genet. 2013;58:627–634. doi: 10.1038/jhg.2013.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rishishwar L, Conley AB, Wigington CH, et al. Ancestry, admixture and fitness in Colombian genomes. Sci Rep. 2015;5:12376. doi: 10.1038/srep12376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Falush D, Wirth T, Linz B, et al. Traces of human migrations in Helicobacter pylori populations. Science. 2003;299:1582–1585. doi: 10.1126/science.1080857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Devi SM, Ahmed I, Khan AA, et al. Genomes of Helicobacter pylori from native Peruvians suggest admixture of ancestral and modern lineages and reveal a Western type cag-pathogenicity island. BMC Genomics. 2006;7:191. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-7-191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]