Abstract

A recent trial demonstrated that patients with knee osteoarthritis treated with a sodium hyaluronate and corticosteroid combination (Cingal) experienced greater pain reductions compared with those treated with sodium hyaluronate alone (Monovisc) or saline up to 3 weeks postinjection. In this study, injections were administered by 1 of 3 approaches; however, there is currently no consensus on which, if any, of these techniques produce a more favorable outcome. To provide additional insight on this topic, the results of the previous trial were reanalyzed to determine whether (1) the effect of Cingal was significant within each injection technique and (2) pain reductions were similar between injection techniques across all treatment groups. Greater pain reductions with Cingal up to 3 weeks were only significant in the anteromedial subgroup. Across all therapies, both the anteromedial and anterolateral techniques demonstrated significantly greater pain reductions than the lateral midpatellar approach at 18 and 26 weeks.

Keywords: Knee osteoarthritis, intra-articular injection, anterolateral, anteromedial, lateral midpatellar

Introduction

Knee osteoarthritis (OA) results in the progressive loss of the articular cartilage, severe pain, and disability in the affected joint.1–6 As the condition is chronic and nonfatal, it can significantly impact an individual’s long-term quality of life.6,7 The goals of OA management are to reduce pain, improve function, slow progression of the disease, and delay surgical intervention.1,3,5

Intra-articular injections, such as a corticosteroid (CS) and hyaluronic acid (HA), may be used to treat knee OA after more conservative methods fail.8–16 They may be administered via a number of different techniques.17,18 These various approaches have been experimented to find the most accurate method of injection that provides optimal therapeutic effect and limits damage to the surrounding joint structures; however, results have been variable and there is still little consensus in the current literature.18–22 Incorrect placement of the needle also causes more pain and discomfort to the patient during and after the procedure, which can have implications on the efficacy of the product being injected.20 Considering the cost for such a small volume of product, research on this topic is essential to determine whether the injection technique could influence clinical outcomes.22,23

The Cingal 13-01 trial was a randomized trial evaluating a cross-linked sodium hyaluronate (Monovisc) combined with a CS (triamcinolone hexacetonide) injection, known as Cingal, for the treatment of knee OA. In this study, physicians injected the product using 1 of 3 approaches: anterolateral, anteromedial, or lateral midpatellar. The injection technique was the choice of the treating physician, presumably based on their technical skill set and personal preference. The results of this trial showed that patients treated with Cingal experienced significantly greater pain reductions than both the Monovisc and saline groups up to 3 weeks postinjection and from 12 to 26 weeks compared with the saline group only.24 The purpose of this subgroup analysis was 2-fold: (1) to determine whether the effect of Cingal, as seen in the primary study, was significant within each of these injection techniques and (2) to determine whether pain reductions were similar between injection techniques across all treatment groups.

Methods

The Cingal 13-01 (NCT01891396) was a randomized, double-blind, saline-controlled, multicenter clinical trial that compared Cingal with both Monovisc and saline. Cingal is a single-injection, cross-linked sodium hyaluronate (Monovisc, 88 mg) combined with a CS (triamcinolone hexacetonide, 18 mg), supplied as a 4-mL unit dose in a 5-mL syringe.24 Monovisc is a single-injection, cross-linked HA injection (molecular weight: 1000-2900 kDa) indicated for the treatment of pain in knee OA.24 Table 1 presents the baseline characteristics of the patients included in this trial. In short, the inclusion criteria of this study were patients diagnosed with Kellgren-Lawrence (KL) grade I-III knee OA, aged 40 to 75 years with a body mass index (BMI) ⩽40 kg/m2 and a baseline Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Arthritis Index (WOMAC) pain score between ⩾40 and ⩽90 mm on a 100-mm scale. Twenty-seven sites in Europe and Canada enrolled 368 patients with knee OA and followed them for 26 weeks, with additional visits scheduled at 1, 3, 6, 12, and 18 weeks. The randomization ratio of the study was 2 (Cingal):2 (Monovisc):1 (saline).24 The primary outcome of the Cingal 13-01 trial was the change from baseline WOMAC pain score in the intention-to-treat (ITT) population at 12 weeks postinjection (Supplementary Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients in the Cingal 13-01 trial by treatment arm.

| Characteristic | Cingal (n = 149) | Monovisc (n = 150) | Saline (n = 69) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y (mean ± SD) | 57.52 ± 8.39 | 59.19 ± 8.62 | 58.03 ± 9.02 |

| Female, No. (%) | 97 (65.10) | 99 (66.00) | 51 (73.91) |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 (mean ± SD) | 28.9 ± 4.7 | 28.4 ± 4.5 | 29.1 ± 4.5 |

| Kellgren-Lawrence grade, No. (%) | |||

| I | 36 (24.2) | 24 (16.0) | 17 (24.6) |

| II | 84 (56.4) | 98 (65.3) | 38 (55.1) |

| III | 29 (19.4) | 27 (18.0) | 14 (20.3) |

| IV | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.7) | 0 (0.0) |

| WOMAC pain, mm (mean ± SD) | 59.0 ± 12.4 | 61.0 ± 11.7 | 58.8 ± 10.6 |

| WOMAC stiffness, mm (mean ± SD) | 53.6 ± 19.3 | 57.2 ± 17.1 | 54.2 ± 17.9 |

| WOMAC function, mm (mean ± SD) | 55.0 ± 16.2 | 56.8 ± 16.8 | 55.8 ± 15.7 |

Abbreviation: WOMAC, Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Arthritis Index.

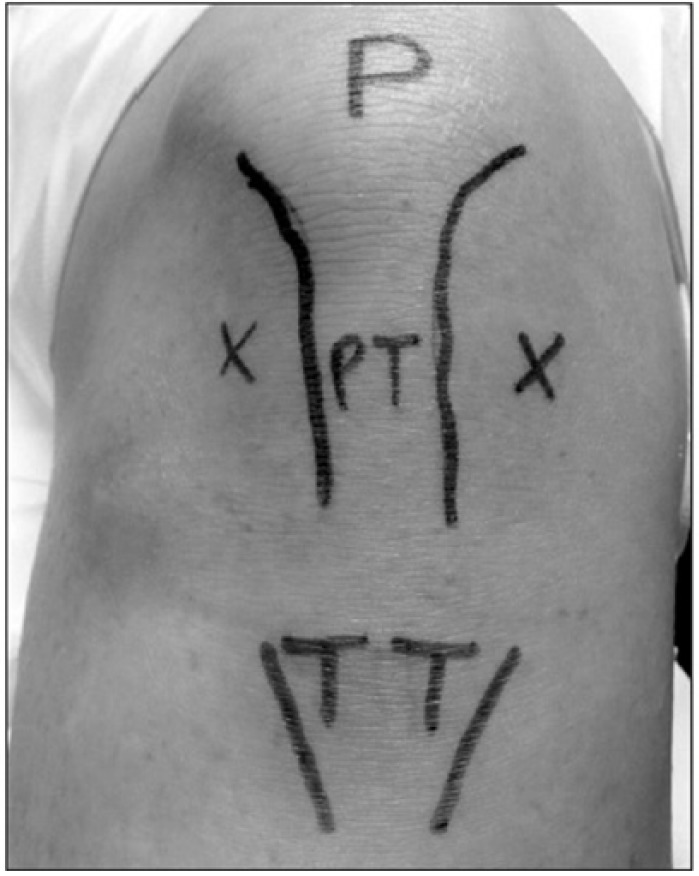

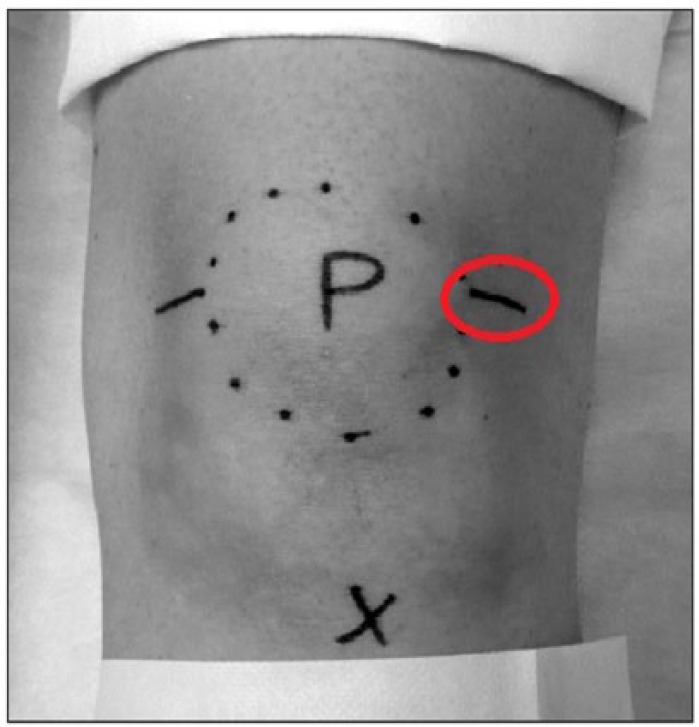

The 3 physician-chosen injection techniques used in the 13-01 trial were the anterolateral, anteromedial, and lateral midpatellar approaches. Both the anterolateral and anteromedial techniques use an arthroscopic (“portal analogue”) approach. With the knee flexed at 90°, the needle is introduced either lateral or medial to the patellar tendon and is directed upward toward the femoral notch (Figure 1).17 The lateral midpatellar approach is performed by directing the needle at a 45° angle toward the middle of the medial aspect of the joint with the knee in extension (Figure 2).17

Figure 1.

Anteromedial and anterolateral approaches. Photograph of left knee. Crosses indicate the anteromedial and anterolateral approaches to injection of the knee joint. P indicates patella; PT, patellar tendon; TT, tibial tuberosity. Adapted from Douglas.17

Figure 2.

Lateral midpatellar approach. Photograph of left knee. Patella (P) is circled. The tibial tuberosity is marked with a cross. Line in red circle indicates lateral midpatellar approach to injection of the knee joint. Adapted from Douglas.17

We conducted post hoc analyses of the primary outcome (WOMAC pain) for each of the 3 injection techniques to determine whether the effect of Cingal, as seen in the primary study, was significant within each of these subgroups. The ITT population included all randomized subjects who received treatment. We also evaluated changes in the WOMAC stiffness and function subscales as secondary outcomes. For exploratory purposes, we pooled the results of all patients receiving the same injection technique, regardless of treatment allocation, to determine whether pain reductions were similar between injection techniques across all treatment groups.

We performed statistical analyses using the SAS software 9.1.3 or higher. We used the last pretreatment observation as the baseline value for calculating posttreatment changes from baseline. As the WOMAC is a continuous outcome variable, on a 0- to 100-mm scale, we compared treatment arms with an analysis of variance using the multiple imputation methodology. The multiple imputation methodology uses a mixed-effects repeated measures model to predict any missing values. We considered a P value less than .05 to be statistically significant.

Results

A total of 368 patients were randomized into the Cingal 13-01 study, with 85 patients receiving an anterolateral injection, 139 receiving an anteromedial injection, and 144 receiving a lateral midpatellar injection. Within the anterolateral subgroup, 35 patients (41.2%) were treated with Cingal, 36 (42.4%) with Monovisc, and 14 (16.5%) with saline. In the anteromedial subgroup, 54 patients (38.8%) were treated with Cingal, 59 (42.4%) with Monovisc, and 26 (18.7%) with saline. In the lateral midpatellar subgroup, 60 patients (41.7%) were treated with Cingal, 55 (38.2%) with Monovisc, and 29 (20.1%) with saline. Table 2 provides their baseline WOMAC subscale scores by injection technique and treatment arm.

Table 2.

Baseline WOMAC subscale scores by injection technique and treatment arm.

| Anterolateral | WOMAC subscale | Cingal (n = 35) | Monovisc (n = 36) | Saline (n = 14) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pain, mm (mean ± SD) | 60.2 ± 11.0 | 61.1 ± 11.5 | 60.3 ± 11.3 | |

| Stiffness, mm (mean ± SD) | 56.1 ± 17.4 | 59.7 ± 18.5 | 58.1 ± 17.2 | |

| Function, mm (mean ± SD) | 59.9 ± 11.9 | 58.5 ± 18.2 | 61.7 ± 10.7 | |

| Anteromedial | WOMAC subscale | Cingal (n = 54) | Monovisc (n = 59) | Saline (n = 26) |

| Pain, mm (mean ± SD) | 59.2 ± 13.3 | 60.3 ± 12.3 | 61.4 ± 11.1 | |

| Stiffness, mm (mean ± SD) | 56.6 ± 21.9 | 58.3 ± 16.7 | 59.6 ± 18.7 | |

| Function, mm (mean ± SD) | 59.5 ± 16.7 | 61.0 ± 14.4 | 61.7 ± 15.3 | |

| Lateral midpatellar | WOMAC subscale | Cingal (n = 60) | Monovisc (n = 55) | Saline (n = 29) |

| Pain, mm (mean ± SD) | 58.1 ± 12.4 | 61.7 ± 11.5 | 55.7 ± 9.3 | |

| Stiffness, mm (mean ± SD) | 49.4 ± 17.3 | 54.5 ± 16.5 | 47.6 ± 15.9 | |

| Function, mm (mean ± SD) | 48.1 ± 15.6 | 51.0 ± 16.9 | 47.7 ± 14.9 |

Abbreviation: WOMAC, Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Arthritis Index.

Primary outcome

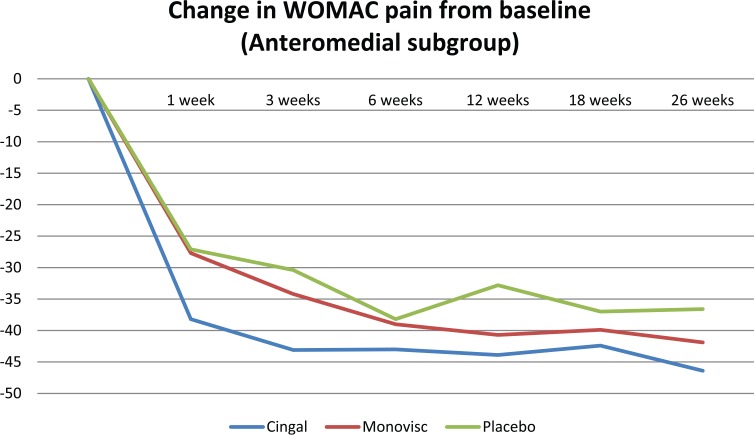

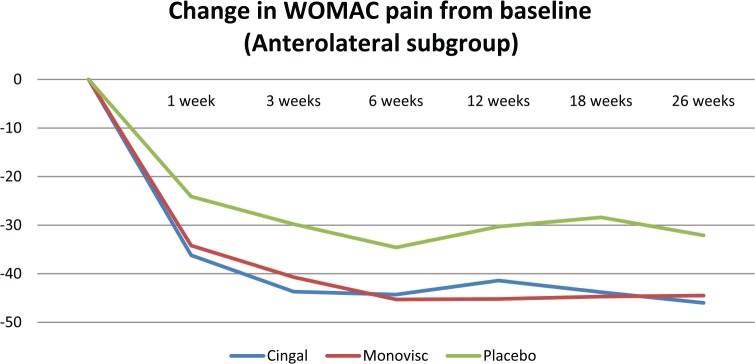

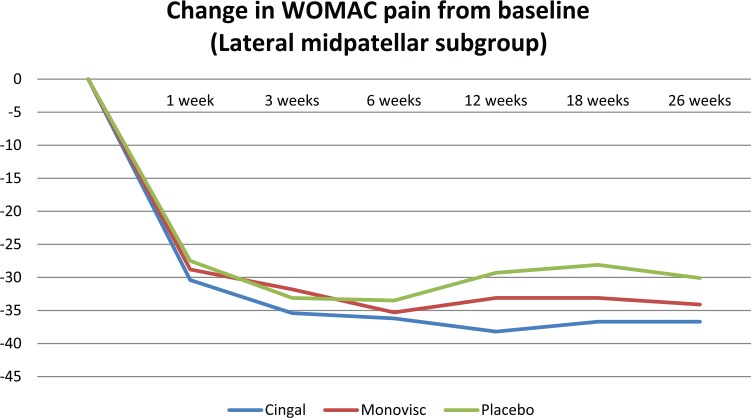

Cingal demonstrated significantly greater pain reductions than both Monovisc alone and saline up to 3 weeks postinjection in the anteromedial injection subgroup only (Table 3; Figure 3). There were no statistically significant differences in pain scores, at any time point, between treatment arms in the anterolateral or lateral midpatellar injection subgroup (Table 3; Figures 4 and 5).

Table 3.

Change in WOMAC pain (100 mm) from baseline by study visit, injection technique, and treatment arm.

| Injection technique | Treatment arm | Difference from baseline |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Week 1 (mean ± SD) | Week 3 (mean ± SD) | Week 6 (mean ± SD) | Week 12 (mean ± SD) | Week 18 (mean ± SD) | Week 26 (mean ± SD) | ||

| Anterolateral (AL) | Cingal | −36.2 ± 21.5 | −43.7 ± 18.7 | −44.3 ± 19.1 | −41.4 ± 21.2 | −43.8 ± 18.7 | −46.0 ± 15.8 |

| Monovisc | −34.2 ± 18.1 | −40.7 ± 18.5 | −45.3 ± 15.9 | −45.2 ± 18.7 | −44.7 ± 23.4 | −44.5 ± 23.8 | |

| Saline | −24.1 ± 14.0 | −29.8 ± 13.2 | −34.6 ± 12.8 | −30.3 ± 18.6 | −28.4 ± 25.9 | −32.1 ± 25.7 | |

| ANOVA (P value) | .1285 | .0535 | .1224 | .0601 | .0526 | .1088 | |

| Anteromedial (AM) | Cingal | −38.2 ± 22.2 | −43.1 ± 22.0 | −43.0 ± 23.2 | −43.9 ± 23.1 | −42.4 ± 23.2 | −46.4 ± 19.8 |

| Monovisc | −27.7 ± 24.0 | −34.2 ± 24.5 | −39.0 ± 23.2 | −40.7 ± 24.5 | −39.9 ± 25.1 | −41.9 ± 24.0 | |

| Saline | −27.1 ± 22.5 | −30.4 ± 22.1 | −38.2 ± 21.9 | −32.8 ± 25.8 | −37.0 ± 26.0 | −36.6 ± 21.5 | |

| ANOVA (P value) | .0312* | .0383+ | .5752 | .1616 | .6438 | .1642 | |

| Lateral midpatellar (LM) | Cingal | −30.4 ± 18.7 | −35.4 ± 18.3 | −36.2 ± 18.7 | −38.2 ± 17.4 | −36.7 ± 18.2 | −36.7 ± 18.1 |

| Monovisc | −28.8 ± 20.2 | −31.8 ± 20.0 | −35.3 ± 18.3 | −33.1 ± 19.9 | −33.1 ± 21.6 | −34.1 ± 20.0 | |

| Saline | −27.5 ± 16.0 | −33.1 ± 18.4 | −33.5 ± 21.8 | −29.3 ± 24.8 | −28.1 ± 21.6 | −30.1 ± 24.1 | |

| ANOVA (P value) | .7671 | .5997 | .8258 | .1190 | .1716 | .3566 | |

Abbreviations: ANOVA, analysis of variance; WOMAC, Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Arthritis Index.

Statistically significant result (P < .05). Cingal demonstrated a significantly greater reduction in pain at this visit compared with both Monovisc and saline (P = .0168 and .0458, respectively), with no significant difference between Monovisc and saline (P = .9154).

Statistically significant result (P < .05). Cingal demonstrated a significantly greater reduction in pain at this visit compared with both Monovisc and saline (P = .0449 and .0231, respectively), with no significant difference between Monovisc and saline (P = .4782).

Post hoc power analysis results at 12 weeks: 55% (AL), 38% (AM), and 43% (LM).

Figure 3.

Change in WOMAC pain (100 mm) from baseline in the anteromedial injection subgroup. WOMAC indicates Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Arthritis Index.

Figure 4.

Change in WOMAC pain (100 mm) from baseline in the anterolateral injection subgroup. WOMAC indicates Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Arthritis Index.

Figure 5.

Change in WOMAC pain (100 mm) from baseline in the lateral midpatellar injection subgroup. WOMAC indicates Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Arthritis Index.

Secondary outcomes

In all injection technique subgroups, there were no statistically significant differences in stiffness scores between treatment arms from baseline to 26 weeks postinjection (Supplementary Table 2; Supplementary Figures 1 to 3).

Cingal demonstrated a significant improvement in function compared with saline at 1 week postinjection in the anteromedial injection subgroup only, but there were no significant differences between Cingal and Monovisc (Supplementary Table 3; Supplementary Figure 4). In both the anterolateral and lateral midpatellar subgroups, there were no statistically significant differences in WOMAC function between treatment arms at any time point (Supplementary Table 3; Supplementary Figures 5 and 6).

Exploratory analysis

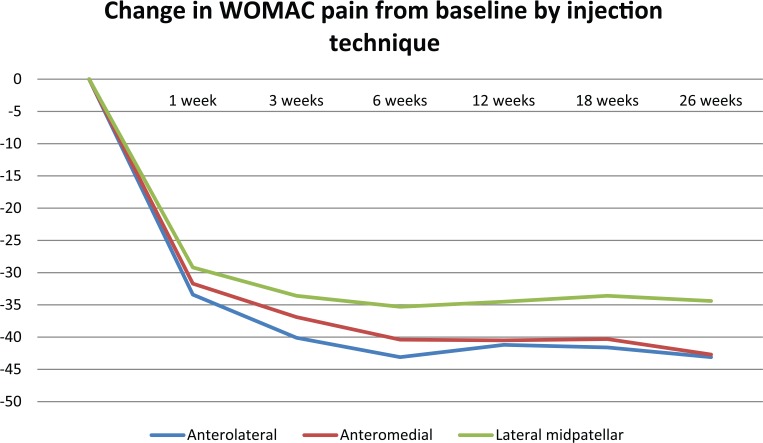

Across all treatment groups, both the anterolateral and anteromedial techniques demonstrated significantly greater pain reductions than the lateral midpatellar approach at 18 and 26 weeks postinjection only (Table 4; Figure 6). At 6 weeks, patients treated with an anterolateral injection experienced significantly greater pain reductions than those treated via the lateral midpatellar approach. Pain scores were not significantly different between the 3 techniques at 1 and 3 weeks postinjection.

Table 4.

Change in WOMAC pain (100 mm) from baseline by study visit and injection technique.

| Injection technique | Baseline (mean ± SD) | Difference from baseline |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Week 1 (mean ± SD) | Week 3 (mean ± SD) | Week 6 (mean ± SD) | Week 12 (mean ± SD) | Week 18 (mean ± SD) | Week 26 (mean ± SD) | ||

| Anterolateral (AL) | 60.6 ± 11.3 | −33.4 ± 18.8 | −40.1 ± 17.7 | −43.1 ± 16.7 | −41.2 ± 19.7 | −41.6 ± 21.9 | −43.1 ± 20.8 |

| Anteromedial (AM) | 60.1 ± 12.5 | −31.7 ± 23.0 | −36.9 ± 23.1 | −40.4 ± 23.0 | −40.5 ± 24.2 | −40.3 ± 24.5 | −42.7 ± 21.9 |

| Lateral midpatellar (LM) | 59.0 ± 11.4 | −29.2 ± 18.7 | −33.6 ± 19.0 | −35.3 ± 19.2 | −34.5 ± 19.8 | −33.6 ± 20.2 | −34.4 ± 20.0 |

| ANOVA (P value) | — | .2969 | .0621 | .0118* | .0248* | .0101* | .0009* |

| AL vs AM (P value) | — | .8182 | .4898 | .5963 | .9697 | .9059 | .9894 |

| AL vs LM (P value) | — | .2915 | .0527 | .0139* | .0608 | .0245* | .0071* |

| AM vs LM (P value) | — | .5597 | .3621 | .0868 | .0514 | .0318* | .0027* |

Abbreviations: ANOVA, analysis of variance; WOMAC, Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Arthritis Index.

Post hoc power analysis result at 12 weeks: 68%.

Statistically significant result (P < .05).

Figure 6.

Change in WOMAC pain (100 mm) from baseline by injection technique.

Discussion

The Cingal 13-01 trial provided evidence that in patients with knee OA, treatment with a cross-linked sodium hyaluronate combined with a CS (triamcinolone hexacetonide) results in significantly greater pain reductions compared with both viscosupplementation alone and saline up to 3 weeks postinjection. In this study, intra-articular drug infiltration was administered by 1 of 3 different injection techniques (ie, the anterolateral, anteromedial, or lateral midpatellar) at the discretion of the treating physician, as there is currently no standard approach to injection. The results of the subgroup analyses suggested that (1) treatment with Cingal might be most efficacious using the anteromedial technique and (2) both the anteromedial and anterolateral techniques may produce a more favorable outcome than the lateral midpatellar approach in the administration of any intra-articular therapy up to 26 weeks postinjection.

Although subgroup analyses are typically considered underpowered,25 they are useful in identifying if certain baseline prognostic variables might have an influence on outcomes that could warrant further investigation. Although additional research with adequately powered studies is required, these results suggest that the anteromedial injection technique may be the preferred option for patients with knee OA receiving treatment with Cingal. This injection technique was the only 1 of the 3 that resulted in significantly greater pain relief with Cingal compared with both Monovisc alone and saline up to 3 weeks postinjection, as seen in the primary study (Cingal 13-01 trial).

Douglas previously stated that both the anterolateral and anteromedial techniques are reported to involve little pain and discomfort, whereas Wind and Smolinski suggested that the lateral midpatellar approach may not be reliable for routine injections of low volumes of fluid into the knee, as it only results in good intra-articular delivery less than half the time with a high incidence of soft-tissue infiltration.17,22 The results of our exploratory analysis would agree with their conclusions. It is important to note, however, that such observations may not only be attributed to the effect of the injection technique itself but may also be due to a physician’s experience with the approach. Another caveat to this comparison is that a physician’s decision as to which injection technique is most appropriate may be influenced by where in the joint the OA is located. If this was the case among some of the study investigators, then the type of knee OA (eg, medial versus lateral compartment OA) could also explain differences in treatment responses.

Previous studies that compared these injection techniques offer conflicting recommendations. Jackson et al20 recommended using the lateral midpatellar approach as, according to their study, it resulted in the greatest accuracy (93%) relative to the anterolateral (71%) and anteromedial (75%) techniques while also citing that the lateral midpatellar approach allows the needle to pass through a minimal amount of soft tissue to reach the intra-articular space. Esenyel et al26 also compared the accuracy of all 3 injection techniques and determined that the anterolateral approach was the most accurate (85%), but this was not statistically significant compared with the accuracy rates of both the anteromedial (73%) and lateral midpatellar (76%) techniques. After conducting a review of the literature, Januchowski and Overdorf18 stated that any of the approaches from the lateral side are consistently more accurate than the medial approach. Telikicherla and Kamath23 evaluated the anterolateral and lateral midpatellar techniques and calculated accuracy rates of 87.4% and 91.5%, respectively. Finally, in a systematic review with statistical pooling of accuracy rates, Hermans et al27 calculated estimates of 85% (95% confidence interval [CI]: 68%-100%), 72% (95% CI: 65%-78%), and 67% (95% CI: 43%-91%) for the lateral midpatellar, anteromedial, and anterolateral approaches, respectively; however, the studies included in this systematic review examined a range of different patient populations. There is also limited research on whether there are certain considerations, related to factors such as a physician’s prior experience, the literature, or patient or disease characteristics, which might influence a physician’s decision to choose a particular injection technique over another.

One of the strengths of our study was that we acquired the data from a randomized clinical trial, ensuring comparable patient populations and similar distributions of prognostic variables between treatment arms at baseline.28 Second, we analyzed the data using the ITT principle, which allowed us to include all randomized patients into the analyses and maintain the prognostic balance achieved from the randomization process.29–31 Also, the scale evaluated in our study (ie, the WOMAC) is a previously validated health measure developed specifically for patients with knee OA to assess their changes in pain, stiffness, and physical function during clinical trials.32,33 A final strength of our analysis was that we determined comparative effects between treatment arms both in the short-term and longer-term follow-ups. Individual treatments may only have a significant effect for just a few weeks, whereas others may require a longer period of time before demonstrating any efficacy at all. The ability to identify such differences would be clinically meaningful and could help physicians optimize therapy for their patients to reduce symptoms throughout the disease’s progression. A weakness of our study was that the subgroup analyses were underpowered (the post hoc power analysis revealed that they had 38% to 55% power to detect differences at a significance level of 0.05) and we cannot make any definitive conclusions based on their results. Our exploratory analysis may be confounded by the inclusion of patients who received saline injections; however, the randomization ratio of 2:2:1 from the original 13-01 trial was preserved within each injection technique subgroup, and the proportions of those who received saline across these subgroups were similar. There was also imbalance in the sample sizes of the injection technique subgroups as just 85 patients received an anterolateral injection compared with 139 and 144 for the anteromedial and lateral midpatellar approaches, respectively. The trial investigators only included patients with a KL grade between I and III and a BMI ⩽40 kg/m2; therefore, we cannot generalize the results to patients with the most severe case of knee OA (KL grade IV) nor to those who are considered more obese. Also, further research should investigate whether differential effects might exist across these methods depending on OA severity. Another consideration is that we did not know the proportion of patients who had an injection that was truly intra-articular and a re-evaluation of the outcomes that only includes such patients may have different results. This study only enrolled patients from clinical sites in Canada and Europe, and it is possible that patients outside of these geographical locations may not have a similar response to these different therapies and injection techniques.

Conclusions

To provide some additional insight on the controversy surrounding the various injection techniques, we conducted subgroup analyses of a previous trial that demonstrated significantly greater pain relief up to 3 weeks with a sodium hyaluronate and CS combination (Cingal) relative to both sodium hyaluronate alone (Monovisc) and saline. In this trial, physicians administered treatment using an anteromedial, anterolateral, or lateral midpatellar approach. Greater pain reductions with Cingal relative to both Monovisc and saline were statistically significant up to 3 weeks in the anteromedial subgroup only, whereas pain reductions were not significantly different between these treatments at subsequent visits up to 26 weeks. Pain reductions were not significantly different between Cingal, Monovisc, and saline in the anterolateral or lateral midpatellar subgroup. A separate analysis revealed that across all therapies, both the anterolateral and anteromedial approaches resulted in significantly greater pain reductions than the lateral midpatellar method at 18 and 26 weeks postinjection. Prior studies on the topic provide conflicting results, and additional investigations are required before we can make any definitive conclusions.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Peer review:Two peer reviewers contributed to the peer review report. Reviewers’ reports totaled 282 words, excluding any confidential comments to the academic editor.

Funding:The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study was funded by a research grant from Pendopharm.

Declaration of conflicting interests:The author(s) declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: R.D. discloses speaking for Pendopharm, consulting for Anika Therapeutics, and teaching for Arthrex. M.L. is a consultant for Pendopharm. E.L.B. discloses speaking for Pendopharm, consulting for Zimmer Biomet and Bodycad, and teaching for Smith & Nephew and Stryker.

Author Contributions: ELB, RTD, ML, and RM conceived and designed the experiments. CV analyzed the data and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. ELB, RTD, CV, ML, and RM contributed to the writing of the manuscript; agree with manuscript results and conclusions; jointly developed the structure and arguments for the paper; and made critical revisions and approved final version. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

References

- 1. Losina E, Daigle ME, Suter LG, et al. Disease-modifying drugs for knee osteoarthritis: can they be cost-effective? Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2013;21:655–667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Marsh JD, Birmingham TB, Giffin JR, et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis of arthroscopic surgery compared with non-operative management for osteoarthritis of the knee. BMJ Open. 2016;6:e009949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ozturk C, Atamaz F, Hepguler S, Argin M, Arkun R. The safety and efficacy of intraarticular hyaluronan with/without corticosteroid in knee osteoarthritis: 1-year, single-blind, randomized study. Rheumatol Int. 2006;26:314–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Puig-Junoy J, Ruiz Zamora A. Socio-economic costs of osteoarthritis: a systematic review of cost-of-illness studies. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2015;44:531–541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Rosen J, Sancheti P, Fierlinger A, Niazi F, Johal H, Bedi A. Cost-effectiveness of different forms of intra-articular injections for the treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee. Adv Ther. 2016;33:998–1011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Tarride JE, Haq M, O’Reilly DJ, et al. The excess burden of osteoarthritis in the province of Ontario, Canada. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64:1153–1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Maetzel A, Li LC, Pencharz J, Tomlinson G, Bombardier C. The economic burden associated with osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, and hypertension: a comparative study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2004;63:395–401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Osteoarthritis: Care and Management. London: NICE; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bruyere O, Cooper C, Pelletier JP, et al. A consensus statement on the European Society for Clinical and Economic Aspects of Osteoporosis and Osteoarthritis (ESCEO) algorithm for the management of knee osteoarthritis—from evidence-based medicine to the real-life setting. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2016;45:S3–S11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. The Non-surgical Management of Hip and Knee Osteoarthritis Working Group. VA/DoD clinical practice guideline for the non-surgical management of hip and knee osteoarthritis. https://www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/CD/OA/VADoDOACPGFINAL090214.pdf. Published 2014.

- 11. Hochberg MC, Altman RD, April KT, et al. American College of Rheumatology 2012 recommendations for the use of nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic therapies in osteoarthritis of the hand, hip, and knee. Arthritis Care Res. 2012;64:465–474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Jevsevar DS. Treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee: evidence-based guideline, 2nd edition. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2013;21:571–576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Jordan KM, Arden NK, Doherty M, et al. EULAR recommendations 2003: an evidence based approach to the management of knee osteoarthritis: report of a Task Force of the Standing Committee for International Clinical Studies Including Therapeutic Trials (ESCISIT). Ann Rheum Dis. 2003;62:1145–1155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. McAlindon TE, Bannuru RR, Sullivan MC, et al. OARSI guidelines for the non-surgical management of knee osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2014;22:363–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. National Collaborating Centre for Chronic Conditions. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence: Guidance. Osteoarthritis: National Clinical Guideline for Care and Management in Adults. London: Royal College of Physicians; 2008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sinusas K. Osteoarthritis: diagnosis and treatment. Am Fam Physician. 2012;85:49–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Douglas RJ. Aspiration and injection of the knee joint: approach portal. Knee Surg Relat Res. 2014;26:1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Januchowski R, Overdorf P. Approach to knee injections: a review of the literature. Osteopat Fam Physician. 2014;6:28–32. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gaffney K, Ledingham J, Perry JD. Intra-articular triamcinolone hexacetonide in knee osteoarthritis: factors influencing the clinical response. Ann Rheum Dis. 1995;54:379–381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Jackson DW, Evans NA, Thomas BM. Accuracy of needle placement into the intra-articular space of the knee. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2002;84-A:1522–1527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Jones A, Regan M, Ledingham J, Pattrick M, Manhire A, Doherty M. Importance of placement of intra-articular steroid injections. BMJ. 1993;307:1329–1330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wind WM, Jr, Smolinski RJ. Reliability of common knee injection sites with low-volume injections. J Arthroplasty. 2004;19:858–861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Telikicherla M, Kamath SU. Accuracy of needle placement into the intra-articular space of the knee in osteoarthritis patients for viscosupplementation. J Clin Diagn Res. 2016;10:RC15–RC17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hangody L, Szody R, Lukasik P, et al. Intraarticular injection of a cross-linked sodium hyaluronate combined with triamcinolone hexacetonide (Cingal) to provide symptomatic relief of osteoarthritis of the knee: a randomized; double-blind: placebo-controlled multicenter clinical trial [published online ahead of print May 1, 2017]. Cartilage. doi: 10.1177/1947603517703732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Byth K, Gebski V. Factorial designs: a graphical aid for choosing study designs accounting for interaction. Clin Trials. 2004;1:315–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Esenyel C, Demirhan M, Esenyel M, et al. Comparison of four different intra-articular injection sites in the knee: a cadaver study. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2007;15:573–577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hermans J, Bierma-Zeinstra SM, Bos PK, Verhaar JA, Reijman M. The most accurate approach for intra-articular needle placement in the knee joint: a systematic review. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2011;41:106–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Evaniew N, Carrasco-Labra A, Devereaux PJ, et al. How to use a randomized clinical trial addressing a surgical procedure: users’ guide to the medical literature. JAMA Surg. 2016;151:657–662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Higgins JPT, Green S, eds. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Vol 4 Chichester: John Wiley & Sons; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lewis JA, Machin D. Intention to treat—who should use ITT? Br J Cancer. 1993;68:647–650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Newell DJ. Intention-to-treat analysis: implications for quantitative and qualitative research. Int J Epidemiol. 1992;21:837–841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Bellamy N, Buchanan WW, Goldsmith CH, Campbell J, Stitt LW. Validation study of WOMAC: a health status instrument for measuring clinically important patient relevant outcomes to antirheumatic drug therapy in patients with osteoarthritis of the hip or knee. J Rheumatol. 1988;15:1833–1840. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Brazier JE, Harper R, Munro J, Walters SJ, Snaith ML. Generic and condition-specific outcome measures for people with osteoarthritis of the knee. Rheumatology (Oxford). 1999;38:870–877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.