Abstract

Background:

The inferior glenohumeral ligament, the most important static anterior stabilizer of the shoulder, becomes disrupted in humeral avulsion of the glenohumeral ligament (HAGL) lesions. Unfortunately, HAGL lesions commonly go unrecognized. A missed HAGL during an index operation to treat anterior shoulder instability may lead to persistent instability. Currently, there are no large studies describing the indications for surgical repair or the outcomes of patients with HAGL lesions.

Purpose:

To search the literature to identify surgical indications for the treatment of HAGL lesions and discuss reported outcomes.

Study Design:

Systematic review; Level of evidence, 4.

Methods:

Two reviewers completed a comprehensive literature search of 3 online databases (MEDLINE, EMBASE, and Cochrane Library) from inception until May 25, 2016, using the keywords “humeral avulsion of the glenohumeral ligament” or “HAGL” to generate a broad search. Systematic screening of eligible studies was undertaken in duplicate. Abstracted data were organized in table format, with descriptive statistics presented.

Results:

After screening, 18 studies comprising 118 patients were found that described surgical intervention and outcomes for HAGL lesions. The mean patient was 22 years (range, 12-50 years), and 82% were male. Sports injuries represented 72% of all HAGL injuries. The main surgical indication was primary anterior instability, followed by pain and failed nonoperative management. Commonly associated injuries in patients with identified HAGL lesions included a Bankart lesion (15%), Hill-Sachs lesions (13%), and glenoid bone loss (7%). Reporting of outcome scores varied among the included studies. Meta-analysis was not possible, but all included studies reported significantly improved postoperative stability and function. There were no demonstrated differences in outcomes for patients treated with open versus arthroscopic surgical techniques. All but 2 patients undergoing operative management for HAGL lesions were able to return to sport at their previous levels; these included Olympians and professional athletes.

Conclusion:

HAGL lesions typically occur in younger male patients and are often associated with Bankart lesions and bone loss. Open and arthroscopic management techniques are both effective in preventing recurrent instability.

Keywords: humeral avulsion of the glenohumeral ligament, HAGL, shoulder, instability, sports

Traumatic anterior shoulder instability can cause significant morbidity, preventing return to work or sport.24 The majority of these patients sustain a Bankart lesion (detachment of the anteroinferior labrum), but a less common injury termed a humeral avulsion of the glenohumeral ligament (HAGL) can also occur. Studies place the prevalence of arthroscopically confirmed HAGL lesions at 7.5% to 9.3% of cases of primary shoulder instability.3,34

The inferior glenohumeral ligament (IGHL) is the most important static stabilizer of the shoulder.15,19 A stretch or tear of the anterior band of the IGHL at the glenoid insertion may occur with or without concomitant injury to the labrum and capsule. More infrequently, the disruption occurs at the humeral insertion or midsubstance.2,21,31 Disruption typically occurs with anterior dislocation of the shoulder with the arm in abduction and external rotation, the position in which the IGHL is most stressed.19 Biomechanical studies indicate that the location of the avulsion may depend on the positioning of the arm as well as whether the injury is related to a tension- or compression-type mechanism. There is an increased likelihood of a HAGL lesion with hyperabduction and external rotation, whereas there is an increased likelihood of an associated Bankart lesion with 90° of abduction with compression.16

The HAGL lesion may occur in isolation or as part of a complex defect involving a Hill-Sachs lesion, with or without labral damage.5 The extent of injury is often fully appreciated and diagnosed only at the time of shoulder arthroscopy.5 In the setting of multiple injuries, the HAGL may go unrecognized and cause continued instability.23 Similarly, a missed HAGL during an operation to treat anterior shoulder instability can be a cause of recurrent dislocation or instability.3,17,23

Currently, there are no comprehensive systematic reviews describing the indications for surgical repair or the outcomes of patients with HAGL lesions. The objective of this systematic review was to search the literature to identify surgical indications in the treatment of HAGL lesions and discuss reported outcomes.

Methods

We performed a systematic review of journal articles describing surgical indications and outcomes for HAGL deformity. This study was conducted according to guidance from the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions and was reported according to the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses) statement.11,18

Eligibility Criteria

Included in this review were all studies that reported on indications for, or outcomes following, surgical management of a HAGL lesion. We included data from all study designs that were performed on humans. Exclusion criteria included cadaveric studies and articles unavailable in English.

Search Strategy

Two reviewers completed a comprehensive literature search of 3 online databases (MEDLINE, EMBASE, and Cochrane Library) from inception until May 25, 2016. We used the keywords “Humeral Avulsion of the Glenohumeral Ligament” or “HAGL” to generate a broad search. We formalized the research question and relevant inclusion and exclusion criteria a priori.

Two reviewers independently screened all titles and abstracts and then read the full-text versions of potentially eligible studies for final inclusion. All discrepancies were resolved by consensus or consultation with the senior author. References of included studies were hand-searched for additional eligible studies.

Data Abstraction

Abstraction of relevant data from included studies was completed by 2 reviewers independently and in duplicate. Relevant data included study design, level of evidence, sample size, patient demographic data (age, sex), mechanism of trauma, associated injuries, indication for surgery, intervention used, follow-up length, loss to follow-up data, and surgical outcomes and complications. The data were entered into a Microsoft Excel 2013 database.

Statistical Analysis and Quality Assessment

Discrete variables were reported as counts or proportions and normally distributed continuous variables as means with standard deviations. We quantified interobserver agreement for the reviewers’ assessments of article eligibility using Cohen kappa (κ) and interpreted values according to Landis and Koch as follows: 0, poor; 0.01-0.20, slight; 0.21-0.40, fair; 0.41-0.60, moderate; 0.61-0.80, substantial; and 0.81-1.00, almost perfect.28 Assessment of the quality of evidence was performed with the system outlined by Wright et al35 (levels 1-5). All statistical analyses were performed with Microsoft Excel.

Results

Systematic Search

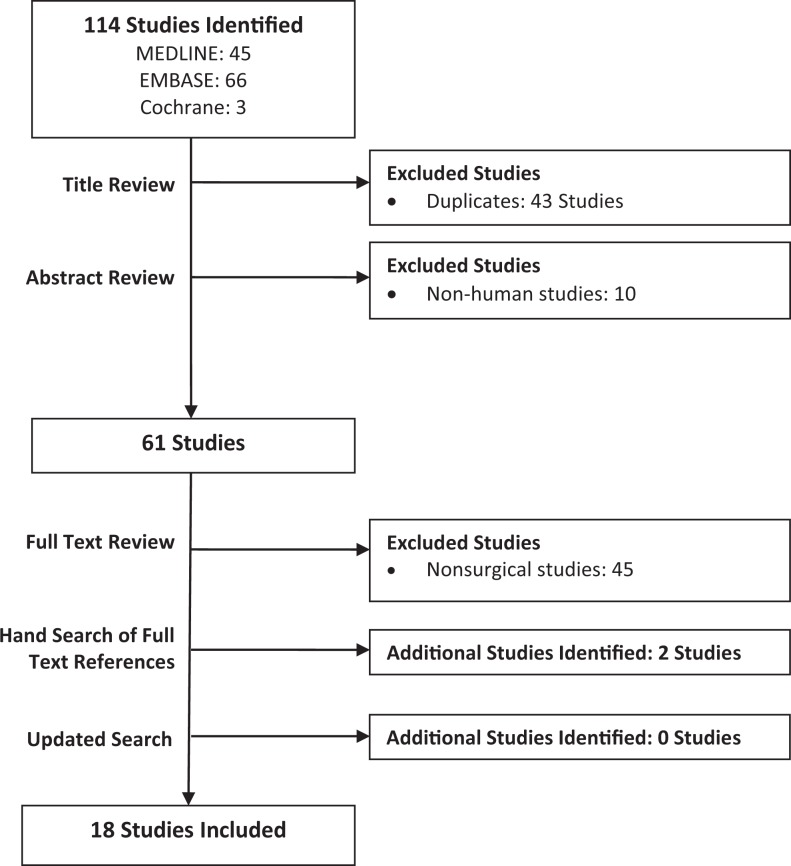

Our initial database search yielded 114 studies. After screening, 18 studies were found that described surgical intervention and outcomes for HAGL lesions. The flowchart in Figure 1 displays the results of each step of the literature search. Interobserver agreement between the reviewers for article inclusion was almost perfect for the title, abstract, and full-text stages, with κ statistics of 0.893 (95% CI, 0.834-0.952), 0.944 (95% CI, 0.891-0.998), and 0.936 (95% CI, 0.850-1.000), respectively. It was not feasible to conduct a meta-analysis, owing to inconsistent reporting of patient outcomes and because all included studies were case reports or case series (level 4 evidence) with no comparison group for pooled analysis. The MINORS (methodological index for nonrandomized studies) scores revealed a generally low quality of evidence with respect to the included investigations (Appendix).29

Figure 1.

Identification of articles.

Patient Demographics

This review examined data from a combined total of 118 patients treated surgically for a HAGL lesion. The average patient age was 22 years (range, 12-50 years), and 82% were male. The mean follow-up period was 26 months (range, 4-60 months). Sports injuries represented 72% of all HAGL injuries. The most common sports or activities associated with this injury were rugby (n = 32), CrossFit (11), baseball (6), volleyball (6), football (5), and pull-ups (5).

Indications for Treatment

The reported indications for treatment and concomitant injuries are shown in Table 1. Primary anterior shoulder instability was the surgical indication for 55 patients in 7 studies.3,8,10,23,27,33,34 Revision surgery for ongoing instability following primary Bankart repair was the indication in 6 patients. Pain was a primary surgical indication for 11 patients in 3 trials.6,26,30 A failed nonoperative management course, ranging from 1 to 22 months, was the surgical indication in 4 studies13,20,22,25 comprising 31 patients. Preoperatively, HAGL lesions were confirmed by either magnetic resonance imaging or magnetic resonance arthrogram in 5 studies1,7,12,22,32 for total of 44 total patients. One author12 reported that 3 of 6 HAGL lesions were missed on magnetic resonance imaging and confirmed intraoperatively.

TABLE 1.

Indications for Surgery and Concomitant Injuriesa

| First Author | No. | Indications for Surgery | Other Bony Injury | Other Soft Tissue Injury |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bokor (1999)3 | 41 | 35 had primary anterior shoulder instability. 6 failed arthroscopic repair targeting other lesions. | Bankart lesion (6, 14.6%) | Subscapularis scarring (8, 19.5%), other cuff tear (7, 17.1%) |

| Smith (2014)30 | 1 | Persistent pain and instability following 4 wk of nonoperative treatment. MRI study revealed avulsion of pIGHL and teres minor. | Teres minor avulsion (1, 100%) | |

| Chang (2014)7 | 4 | Preoperative MRA confirming lesion on all patients. | Rotator cuff tear (2, 50%), posterior labral tear (1, 25%), SLAP tear (1, 25%) | |

| Taljanovic (2011)32 | 4 | Preoperative MRA confirming lesion on all patients. | Rotator cuff tendon tear (3, 75%), SLAP lesion (1, 25%), posterior labral tear (1, 25%) | |

| Provencher (2014)22 | 23 | Failed nonoperative management of shoulder dysfunction with confirmed HAGL tear on MRA. | Labral tear, not specified (10, 43.5%) | |

| Bhatia (2012)1 | 7 | All patients had thorough clinical examination, CT, and MRA. | Glenoid bone loss (7, 100%), Hill-Sachs lesion (7, 100%) | |

| Huberty (2006)12 | 6 | All 6 patients had preoperative MRI; 3 of 6 missed the HAGL lesion later confirmed arthroscopically. | Bankart lesion (6, 100%) | |

| Kon (2005)13 | 3 | Persistent instability in young active patients. All patients had preoperative MRA and 3D-CT. | Bankart lesion (2, 66.7%), Hill-Sachs lesion (2, 66.7%) | |

| Chhabra (2004)8 | 1 | Ongoing symptoms 9 mo after injury. Preoperative MRA results positive for pHAGL lesion. | Glenoid defect (1, 100%) | |

| Schippinger (2001)26 | 1 | Young athletic patient. Lesion sustained from a traumatic dislocation after an initial arthroscopic Bankart repair. No preoperative MRA or CT. | Bankart lesion (1, 100%) | Capsular injury (1, 100%) |

| Shah (2010)27 | 1 | Failure of nonoperative treatment to correct instability in young professional athlete. Preoperative MRI. | Bankart lesion (1, 100%) | |

| Gehrmann (2003)10 | 1 | Young competitive athlete with worsening symptoms after 10 mo of nonoperative management. MRA confirmed IGHL tear. | ||

| Rhee (2007)23 | 6 | Recurrent instability. | Bankart lesion (4, 66.7%) | Cuff tear (1, 16.7%), SLAP lesion (1, 16.7%) |

| Wolf (1995)34 | 6 | Persistent shoulder instability. All 6 HAGL lesions diagnosed on arthroscopy. | Hill-Sachs lesion (2, 33.3%) | |

| Oberlander (1996)20 | 3 | Persistent shoulder instability in 2 patients. One patient was treated nonoperatively. | Hill-Sachs lesion (2, 66.7%) | Supraspinatus tear (1, 33%) |

| Rothberg (2009)25 | 2 | Persistent shoulder instability. | Hill-Sachs lesion (2, 100%) | |

| Warner (1997)33 | 1 | Persistent shoulder instability. | Hill-Sachs and Bankart lesion (1, 100%) | |

| Castagna (2007)6 | 9 | Variable but consistent pain and instability; 7 of 9 had preoperative MRA. All HAGL lesions diagnosed on arthroscopy. | Bankart lesion (4, 44%) | SLAP (1, 11%), ALPSA (1,11%) |

a3D-CT, 3-dimensional computed tomography; ALPSA, anterior labral periosteal sleeve avulsion; HAGL, humeral avulsion of the glenohumeral ligament; IGHL, inferior glenohumeral ligament; MRA, magnetic resonance arthrogram; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; pHAGL, posterior humeral avulsion of the glenohumeral ligament; pIGHL, posterior inferior glenohumeral ligament; SLAP, superior labral anterior and posterior.

Associated Injuries

Of 120 patients with identified HAGL lesions, 18 (15%) had a Bankart lesion and 8 (7%) had demonstrated glenoid bone loss, with 16 (13%) sustaining a concurrent Hill-Sachs lesion. HAGL lesions were also associated with subscapularis tendon scarring in 8 (7%) patients; supraspinatus and teres minor tendon tears were each reported in 1 (0.8%); and rotator cuff tears, not otherwise specified, were reported in 13 (11%) with HAGL lesions. Additionally, SLAP (superior labral anterior and posterior) tears were reported in 4 (3.3%), posterior labrum tears in 2 (1.7%), and an ALPSA (anterior labral periosteal sleeve avulsion) lesion in 1 (0.8%) with HAGL lesions. Labral tears not otherwise specified were reported in 10 (8.3%) patients with concomitant HAGL lesions.

Surgical Technique

Surgical outcomes and complications are shown in Table 2. Two patients did not undergo surgical treatment of their HAGL lesions, leaving 118 patients for surgical evaluation. Open surgical management of HAGL lesions was reported by 8 studies1,10,20,22,23,27,33,34 comprising 33 patients, while arthroscopic surgery was performed in 12 studies∥ totaling 44 patients. Three studies6,23,24 reported outcomes of patients receiving either open or arthroscopic HAGL lesion management. The operative technique was not reported in 1 study of 41 (35%) patients.3 No combined approaches were reported.

TABLE 2.

Patient Outcome Scoresa

| First Author | No. | Open Repair | Arthroscopic Repair | Outcome | Return to Sport |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bokor (1999)3 | 41 | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified |

| Smith (2014)30 | 1 | 1 | No complaints of pain or instability. Full range of motion on examination with full 5 of 5 rotator cuff strength. Stable posterior load-and-shift stress test with no apprehension. Postoperative MRI showed excellent reapproximation of the capsule and teres minor tendon 7 wk after surgery. | 1 of 1, full return to activity | |

| Chang (2014)7 | 4 | 3 | The 1 nonoperative patient had ongoing symptoms and rehab at the final 4-mo follow-up. | 3 of 3 returned to professional play | |

| Taljanovic (2011)32 | 4 | 4 | 4 of 4 had full cuff strength and no instability or apprehension on examination. | 4 of 4 returned to NCAA or professional volleyball for at least 2 y | |

| Provencher (2014)22 | 23 | 14 | 9 | WOSI: preoperative, 54%; postoperative, 17%; SANE: preoperative, 50%; postoperative, 87%. | 21 of 23 (91%) demonstrated satisfaction and a return to full activity |

| Bhatia (2013)1 | 7 | 7 | Normal clinical examination results and no functional limitations at final follow-up. WOSI: preoperative, 52%, postoperative, 1%; OSIS: preoperative, 50; postoperative, 12; Rowe: 95 of 100, postoperative. | ||

| Huberty (2006)12 | 6 | 6 | No recurrent instability at final follow-up. UCLA shoulder score: preoperative, 18.3; postoperative, 33.0. | ||

| Kon (2005)13 | 3 | 3 | Return to full activity and full patient satisfaction at final follow-up time. No recurrent instability or apprehension. Rowe: postoperative, 100, 100, and 92. | 3 of 3 | |

| Chhabra (2004)8 | 1 | 1 | No pain or instability at final follow-up with return to all activity. | 1 of 1 | |

| Schippinger (2001)26 | 1 | 1 | No complaints of pain or instability. | 1 of 1 returned to international-level competition | |

| Shah (2010)27 | 1 | 1 | Full return to strength and range of motion. Patient returned to competitive play, improving his player efficiency rating and leading the league in scoring upon return to play. | 1 of 1 | |

| Gehrmann (2003)10 | 1 | 1 | No recurrence reported at 13 mo postoperation. Patient returned to overhead throwing and sport without complication. | 1 of 1 | |

| Rhee (2007)23 | 6 | 5 | 1 | No reported dislocation following operation. No patient reporting discomfort or disability to daily function or sports activity. Rowe: preoperative, 24; postoperative, 92; Constant score: preoperative, 72; postoperative, 87. | 2 of 2 professional athletes returned to play |

| Wolf (1995)34 | 6 | 2 | 4 | All patients pain free and free of instability at final follow-up. | 6 of 6 |

| Oberlander (1996)20 | 3 | 2 | All patients symptom free at final follow-up, including 1 treated nonoperatively. | 1 of 1 | |

| Rothberg (2009)25 | 2 | 2 | Both patients stable and pain free at 1-y follow-up. | 2 of 2 | |

| Warner (1997)33 | 1 | 1 | No pain or instability at 26-mo final follow-up. Full return to sport. | 1 of 1 | |

| Castagna (2007)6 | 9 | 9 | UCLA rating score: preoperative, 16.3; postoperative, 34.7; Constant score: preoperative, 52.3; postoperative, 80.2; SST score: preoperative, 7.9; postoperative, 4.2. | 9 of 9 reported being able to participate in all desired sports activities without any symptoms or limitations |

aMRI, magnetic resonance imaging; NCAA, National Collegiate Athletic Association; OSIS, Oxford shoulder instability score; SANE, single-assessment numerical evaluation; SST, Simple Shoulder Test; UCLA, University of California, Los Angeles; WOSI, Western Ontario Shoulder Instability Index.

Outcomes

Outcomes were reported for 79 patients in 17 studies (all but Bokor et al3). There were no demonstrated differences in outcomes postoperatively for patients treated with open versus arthroscopic surgical techniques. Only 2 of the 79 patients undergoing operative management for their HAGL lesions were unable to return to play in a sport at their previous levels. Notably, several Olympic and professional athletes were able to return to play at their previous levels. Reporting of outcome scores was varied and inconsistent among studies. The largest group, 67% of included trials, cited an outcome of no patient-reported pain or clinically demonstrated instability (via apprehension test) in 34 patients. Three studies1,13,23 measured surgical outcomes via the Rowe score for shoulder instability in 16 patients, with an average postoperative score of 94%. Two studies1,22 used the Western Ontario Shoulder Instability Index in 30 patients, with an average preoperative score of 54% and postoperative score of 13%. Two studies6,12,23 used both the UCLA (University of California, Los Angeles) Shoulder Rating Scale and Constant Shoulder Score in 15 patients (average pre- and postoperative UCLA scores of 17 and 34 and Constant scores of 60 and 83, respectively). A multitude of other outcome measures were utilized in individual studies, as summarized in Table 2. It is worth noting that of the 2 patients treated nonoperatively, 1 had symptomatic instability at final follow-up.

Discussion

The main indication for operative management of a HAGL lesion was instability, followed by pain. Whereas a majority of patients (58%) underwent arthroscopic surgical management of their HAGL lesions, no difference in outcome was shown between open and arthroscopic management. While outcome reporting was inconsistent among the included studies, the majority of patients demonstrated resolution of instability and pain cessation with surgical treatment of their HAGL lesions. All but 2 patients returned to their previous levels of play; these included a few professional and Olympic athletes. Regarding demographics, the typical HAGL patient was male (82%), 23 years old, and sustained the injury from sport. While HAGL lesions may occur in isolation, more commonly, other bony or rotator cuff tear pathologies are present.5,9,26,32,33 In our review, 19% of patients also suffered from some form of rotator cuff tear or scarring, while 13% of patients had concurrent glenoid bone loss. HAGL lesions may go unnoticed in the setting of multiple shoulder injuries and, if missed during the index surgery, may necessitate revision surgery because of persistent instability.

Our findings highlight the importance of recognizing HAGL lesions in patients with recurrent anterior shoulder instability and pain. This lesion should be considered (1) in the presence of a known Bankart lesion, Hill-Sachs defect, or rotator cuff pathology and (2) in the absence of any other demonstrable cause of chronic shoulder instability and pain. The importance of a history of chronic shoulder pain and anterior instability in the failed nonoperatively or operatively managed patient should prompt consideration of a HAGL lesion.6 The importance of a thorough examination during arthroscopy must be underscored. As mentioned, identification of the HAGL lesion complex is difficult. Bhatia and DasGupta1 reported success with the use of a magnetic resonance arthrogram and arthroscopic evaluation to identify HAGL lesions. Currently, the most ideal imaging modality for HAGL lesions is the magnetic resonance arthrogram.13 The finding of a J-shaped axillary pouch in the inferior glenohumeral ligament complex, instead of the usual U-shape, as coupled with a convincing clinical history, warrants surgical investigation/treatment.4

Strengths

At present, this work represents the largest systematic review of HAGL lesion surgical outcomes and is the first to report on surgical indications. It has been reported that patients who are managed nonoperatively for HAGL lesions have shoulder instability recurrence rates as high as 90%.14 Thus, we sought to examine only surgical outcomes for HAGL deformities. Our results corroborate those of a recently conducted smaller systematic review of HAGL lesions by Longo et al.14 In their review, Longo et al reported on a total of 42 HAGL lesions, for which 25 patients underwent operative management. Broadened search criteria and a thorough review of the references of included trials allowed this current systematic review to be increasingly inclusive of studies reporting on the surgical management of HAGL lesions, thus allowing our analysis to include a total of 118 patients. Additionally, our review exclusively synthesized reports of operative indications and outcomes of HAGL lesions, given the paucity of reported outcomes for nonoperatively managed HAGL lesions.

Limitations

Our findings are limited primarily by the quality of the included studies in our review, which are all level 4 case series and case reports. Our major limitations within these trials stemmed from incomplete and/or inadequate reporting across the included studies. Although we aimed to abstract data to further subdivide pathology (Table 2), very limited data were reported on HAGL lesion size, athlete demographics, and levels of competition pre- and postinjury. Outcomes were difficult to analyze, as few studies utilized the same outcome measures in their reports. Additionally, most of the trials contained fewer than 10 patients, indicating the rarity of this lesion. We included only studies published in English, and this may have led to a publication bias.

Conclusion

The HAGL lesion is now a well-recognized cause for recurrent anterior shoulder instability. HAGL lesions respond poorly to nonoperative management, and functional outcomes appear to be good for patients undergoing either open or arthroscopic management. The absence of any level 1 or 2 evidence studies on HAGL lesion surgical treatment is concerning but not unexpected, considering the lower occurrence of HAGL lesions as compared with Bankart lesions. Most systematic reviews conclude with a statement suggesting that well-constructed multicenter randomized controlled trials are required. To better characterize and understand the outcome of surgical management of HAGL lesions, we recommend that researchers and surgeons focus on developing prospective registries using contemporary and relevant outcome tools.

Appendix

MINORS Score by Studya

| First Author | Year | Study Location | Study Design | Level of Evidence | Length of Follow-up, mo | MINORS Score (Out of 16) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bokor3 | 1999 | Australia | Retrospective case review | 4 | Not reported | 9 |

| Smith30 | 2014 | USA | Case series | 4 | Not reported | 7 |

| Chang7 | 2014 | USA | Case series | 4 | 4-60 | 5 |

| Taljanovic32 | 2011 | USA | Case series | 4 | 24-60 | 10 |

| Provencher22 | 2014 | USA | Case series | 4 | 24-68 | 11 |

| Bhatia1 | 2013 | India | Case series | 4 | 20 | 11 |

| Huberty12 | 2006 | USA | Case series | 4 | 31.8 | 10 |

| Kon13 | 2005 | Japan | Case series | 4 | 12-24 | 10 |

| Chhabra8 | 2004 | USA | Case report | 5 | 9 | 8 |

| Schippinger26 | 2001 | Austria | Case report | 5 | 12 | 6 |

| Shah27 | 2010 | USA | Case report | 5 | 36 | 7 |

| Gehrmann10 | 2003 | USA | Case report | 5 | 13 | 7 |

| Rhee23 | 2007 | South Korea | Case series | 4 | 20-52 | 10 |

| Wolf34 | 1995 | USA | Case series | 4 | 26-54 | 8 |

| Oberlander20 | 1996 | USA | Case series | 4 | 24-36 | 8 |

| Rothberg25 | 2009 | USA | Case series | 4 | 12 | 9 |

| Warner33 | 1997 | USA | Case report | 5 | 26 | 8 |

| Castagna6 | 2007 | USA | Case series | 4 | 28-39 | 11 |

aMINORS, methodological index for nonrandomized studies.

Footnotes

One or more of the authors has declared the following potential conflict of interest or source of funding: G.S.A. is a consultant for Wright Medical, Imascap, and Exactech.

References

- 1. Bhatia DN, DasGupta B. Surgical treatment of significant glenoid bone defects and associated humeral avulsions of glenohumeral ligament (HAGL) lesions in anterior shoulder instability. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2013;21(7):1603–1609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bigliani LU, Pollock RG, Soslowsky LJ, Flatow EL, Pawluk RJ, Mow VC. Tensile properties of the inferior glenohumeral ligament. J Orthop Res. 1992;10(2):187–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bokor D, Conboy V, Olson C. Anterior instability of the glenohumeral joint with humeral avulsion of the glenohumeral ligament. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1999;81:93–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bui-Mansfield LT, Banks KP, Taylor DC. Humeral avulsion of the glenohumeral ligaments the HAGL lesion. Am J Sports Med. 2007;35(11):1960–1966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bui-Mansfield LT, Taylor DC, Uhorchak JM, Tenuta JJ. Humeral avulsions of the glenohumeral ligament: imaging features and a review of the literature. Am J Roentgenol. 2002;179(3):649–655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Castagna A, Snyder SJ, Conti M, Borroni M, Massazza G, Garofalo R. Posterior humeral avulsion of the glenohumeral ligament: a clinical review of 9 cases. Arthroscopy. 2007;23(8):809–815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chang EY, Hoenecke HR, Jr, Fronek J, Huang BK, Chung CB. Humeral avulsions of the inferior glenohumeral ligament complex involving the axillary pouch in professional baseball players. Skeletal Radiol. 2014;43(1):35–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chhabra A, Diduch DR, Anderson M. Arthroscopic repair of a posterior humeral avulsion of the inferior glenohumeral ligament (HAGL) lesion. Arthroscopy. 2004;20:73–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Field LD, Bokor DJ, Savoie FH. Humeral and glenoid detachment of the anterior inferior glenohumeral ligament: a cause of anterior shoulder instability. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1997;6(1):6–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gehrmann RM, DeLuca PF, Bartolozzi AR. Humeral avulsion of the glenohumeral ligament caused by microtrauma to the anterior capsule in an overhand throwing athlete: a case report. Am J Sports Med. 2003;31(4):617–619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Higgins JP, Green S Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Vol 5 Hoboken, NJ: Wiley Online Library; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Huberty DP, Burkhart SS. Arthroscopic repair of anterior humeral avulsion of the glenohumeral ligaments. Techniques in Shoulder & Elbow Surgery. 2006;7(4):186–190. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kon Y, Shiozaki H, Sugaya H. Arthroscopic repair of a humeral avulsion of the glenohumeral ligament lesion. Arthroscopy. 2005;21(5):632, e631–e632, e636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Longo UG, Rizzello G, Ciuffreda M, et al. Humeral avulsion of the glenohumeral ligaments: a systematic review. Arthroscopy. 2016;32(9):1868–1876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lugo R, Kung P, Ma CB. Shoulder biomechanics. Eur J Radiol. 2008;68(1):16–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. McMahon P, Dettling J, Sandusky M, Tibone J, Lee T. The anterior band of the inferior glenohumeral ligament assessment of its permanent deformation and the anatomy of its glenoid attachment. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1999;81(3):406–413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Melvin JS, MacKenzie JD, Nacke E, Sennett BJ, Wells L. MRI of HAGL lesions: four arthroscopically confirmed cases of false-positive diagnosis. Am J Roentgenol. 2008;191(3):730–734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(4):264–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. O’Connell PW, Nuber GW, Mileski RA, Lautenschlager E. The contribution of the glenohumeral ligaments to anterior stability of the shoulder joint. Am J Sports Med. 1990;18(6):579–584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Oberlander MA, Morgan BE, Visotsky JL. The BHAGL lesion: a new variant of anterior shoulder instability. Arthroscopy. 1996;12(5):627–633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Park KJ, Tamboli M, Nguyen LY, McGarry MH, Lee TQ. A large humeral avulsion of the glenohumeral ligaments decreases stability that can be restored with repair. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014;472(8):2372–2379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Provencher M, McCormick F, LeClere LE, Dewing CB, Solomon DJ. A prospective outcome evaluation of humeral avulsions of the glenohumeral ligament (HAGL) tears repairs in an active population. Orthop J Sports Med. 2014;2(1 suppl):2325967114S2325900013. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Rhee YG, Cho NS. Anterior shoulder instability with humeral avulsion of the glenohumeral ligament lesion. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2007;16(2):188–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Robinson CM, Seah M, Akhtar MA. The epidemiology, risk of recurrence, and functional outcome after an acute traumatic posterior dislocation of the shoulder. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011;93(17):1605–1613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Rothberg DL, Burks RT. Capsular tear in line with the inferior glenohumeral ligament: a cause of anterior glenohumeral instability in 2 patients. Arthroscopy. 2009;25(8):934–936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Schippinger G, Vasiu PS, Fankhauser F, Clement HG. HAGL lesion occurring after successful arthroscopic Bankart repair. Arthroscopy. 2001;17(2):206–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Shah AA, Selesnick FH. Traumatic shoulder dislocation with combined bankart lesion and humeral avulsion of the glenohumeral ligament in a professional basketball player: three-year follow-up of surgical stabilization. Arthroscopy. 2010;26(10):1404–1408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Sim J, Wright CC. The kappa statistic in reliability studies: use, interpretation, and sample size requirements. Phys Ther. 2005;85(3):257–268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Slim K, Nini E, Forestier D, Kwiatkowski F, Panis Y, Chipponi J. Methodological index for non-randomized studies (MINORS): development and validation of a new instrument. ANZ J Surg. 2003;73(9):712–716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Smith PA, Nuelle CW, Bradley JP. Arthroscopic repair of a posterior bony humeral avulsion of the glenohumeral ligament with associated teres minor avulsion. Arthrosc Tech. 2014;3(1):e89–e94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Southgate DF, Bokor DJ, Longo UG, Wallace AL, Bull AM. The effect of humeral avulsion of the glenohumeral ligaments and humeral repair site on joint laxity: a biomechanical study. Arthroscopy. 2013;29(6):990–997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Taljanovic MS, Nisbet JK, Hunter TB, Cohen RP, Rogers LF. Humeral avulsion of the inferior glenohumeral ligament in college female volleyball players caused by repetitive microtrauma. Am J Sports Med. 2011;39(5):1067–1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Warner JJ, Beim GM. Combined Bankart and HAGL lesion associated with anterior shoulder instability. Arthroscopy. 1997;13(6):749–752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Wolf EM, Cheng JC, Dickson K. Humeral avulsion of glenohumeral ligaments as a cause of anterior shoulder instability. Arthroscopy. 1995;11(5):600–607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Wright JG, Swiontkowski MF, Heckman JD. Introducing levels of evidence to the journal. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85(1):1–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]