Abstract

This research examined adolescents’ written text messages with sexual content to investigate how sexting relates to sexual activity and borderline personality features. Participants (N = 181, 85 girls) completed a measure of borderline personality features prior to 10th grade and were subsequently given smartphones configured to capture the content of their text messages. Four days of text messaging were micro-coded for content related to sex. Following 12th grade, participants reported on their sexual activity and again completed a measure of borderline personality features. Results showed that engaging in sexting at age 16 was associated with reporting an early sexual debut, having sexual intercourse experience, having multiple sex partners, and engaging in drug use in combination with sexual activity two years later. Girls engaging in sex talk were more likely to have had sexual intercourse by age 18. Text messaging about hypothetical sex in grade 10 also predicted borderline personality features at age 18. These findings suggest that sending text messages with sexual content poses risks for adolescents. Programs to prevent risky sexual activity and to promote psychological health could be enhanced by teaching adolescents to use digital communication responsibly.

Keywords: Text Messaging, Sexting, Sexual Activity, Risky Sexual Activity, Borderline Personality Features, Adolescents

1. Introduction

Adolescents prefer text messaging as a way to communicate with peers, even above face-to-face communication (Lenhart, 2012), and texting may play an important role in emerging sexual relationships. Sexting refers to sending sexually explicit or suggestive images, videos, or text messages via digital communication (Cox Communications, 2009). Although sending nude or nearly nude pictures has serious psychological and legal consequences, we should not ignore the practice of adolescents sending sexually suggestive written text messages. Adolescents more frequently exchange written sext messages than sexual images (Drouin, Ross, & Tobin, 2015; Fleschler-Peskin et al., 2013; The National Campaign to Prevent Teen and Unplanned Pregnancy [NCPTUP], 2008). Further, teens’ engagement in sex talk using other forms of digital communication has been linked to increased sexual behavior intent, increased risks of victimization, and unwanted sexual solicitation (e.g., Moreno, Brockman, Wasserheit & Christakis, 2012, Brown, Keller, & Stern, 2009). Thus, the current study defined sexting as sending text messages containing written sexual content and unlike previous studies, this research examined the actual content of adolescents’ text messages.

Sexting may confer risk for early sexual activity and other risky sexual behaviors, as well as other forms of maladjustment. Indeed, the immediacy of sexting could contribute to the emergence of borderline personality features given that it constitutes a source of attention and reassurance seeking for vulnerable youth desperate for relationships. The primary goals of this study were to: examine the prevalence of sexting among a typically developing adolescent sample, examine whether sending text messages about sex relates to sexual activity, examine whether sexting predicts borderline personality features above and beyond sexual activity, and examine whether borderline personality features predict engaging in sexting. The current study also explored gender differences in sending text messages discussing sex. Because younger adolescents are in an important developmental period of establishing identity and mid-to late-adolescence is a time for sexual exploration, understanding the relations between sexting, sexual activity, and adjustment is vital to developing prevention programs for risky sexual behavior (DeLamater & Friedrich, 2002).

Sending text messages about sex may relate to actual sexual activity because adolescents co-construct their online and offline identities. Co-construction theory suggests that in both their offline relationships and in their digital communication, adolescents work through critical developmental issues such as identity formation, autonomy development, intimacy, and sexual identity (Subrahmanyam & Greenfield, 2008). Adolescents’ online and offline identities and social relationships are psychologically connected and influence adolescent identity formation.

Furthermore, because adolescents’ online relationships often provide developmental contexts for offline relationships, examining adolescents’ exploration of intimate disclosure in the context of digital communication might provide insight into the relation between sexting and psychological outcomes. Previous research suggests that engaging in sexting is linked to psychological disorders such as histrionic personality disorder, social anxiety, and attachment anxiety among young adults (Drouin & Landgraff, 2012; Ferguson, 2011; Reid & Reid, 2007; Weisskirch & Delevi, 2011). In light of the associations between sexting and psychological disorders with symptomology similar to borderline personality disorder (BPD), examining sexting behaviors as a possible predictor of borderline personality features seems warranted as does the idea that BPD features and sexting are likely reciprocally related.

1.1 Digital communication and adolescent sexuality

Digital technologies are attractive to adolescents as a source of sexual information and exploration because they are widely available, are always on, and are viewed as being safe (Brown et al., 2009; Subrahmanyam, Greenfield, & Tynes, 2004). Rather than communicate face-to-face, adolescents prefer to text one another during the initial stages of a romantic relationship due to the privacy, sense of constant connectedness, and ease of conversing (Pascoe, 2011). The findings suggest that adolescents perceive a sense of control over their environment when communicating by text messaging. Given the discreet, dyadic nature of text messaging and considering that adults rarely monitor adolescents’ text messaging, adolescents may use texting as a forum for sexual discussion (Devitt & Roker, 2009). Therefore, analyzing adolescents’ text messages about sex allows access to what might be considered privileged information, information that might be difficult to obtain using self-report methods.

Little is known about why teens engage in sexting, under what conditions they engage in sexting, and the consequences associated with the behavior. Sexting might be understood in the context of the co-construction model of development which suggests that adolescents often meet peers offline and seek to pursue or enhance their relationships online (Pascoe, 2011; Subrahmanyam & Greenfield, 2008). The co-construction model of adolescent development suggests that when interacting with peers via digital communication such as text messaging, adolescents are co-constructing their environment rather than simply being shaped by their environment (Subrahmanyam et al., 2006). For instance, many youth display their sexual orientation on social networking sites, post stories and poems about sex, write blogs detailing sexual experiences, and share sexually explicit pictures and messages via cell phones; thus they are detailing their offline sexual experiences in an online forum (Brown et al., 2009). As a result, adolescents are able to openly present a digital persona that might be difficult to communicate in the real world. For example they can communicate a digital identity that is either sexual or not, in a relationship or not, or open to new experiences, and in doing so they are able to address multiple key developmental tasks of adolescence including identity formation, autonomy, intimacy, and sexuality.

According to an internet survey conducted by a popular media outlet, adolescents more frequently send sexually suggestive messages than nude or semi-nude pictures or videos, with 39% reporting having sent a sexually suggestive message and 48% reporting having received such messages (NCPTUP, 2008). Further, approximately 25% of high school students reported sending and 32% reported receiving sexually suggestive written text messages (Fleschler-Peskin et al., 2013); and 68% of young adult participants reported sending a text-only sext message as opposed to 47% of participants who reported sending a sexually explicit picture (Drouin et al., 2015). Twenty-two percent of teens reported being more forward and aggressive when sending text messages containing sexually suggestive words than they are in face-to-face conversations (NCPTUP, 2008). Considering the possibly aggressive nature of sext messages, sexting could be associated with sadness, depression, and suicidal thoughts (Dake, Price, Maziarz, & Ward, 2012). Sexting was related to symptoms of anxiety and depression when sexting was consensual, but unwanted (i.e., one of the participants felt coerced into participating; Drouin et al., 2015). Sexting has also been shown to be related to psychosocial problems such as low self-esteem (Ybarra & Mitchell, 2014) and to digital media dating violence (Reed, Tolman, & Ward, 2016; Van Ouytsel, Ponnet, Walrave, 2016).

1.2 Adolescent sexting and sexual activity

Adolescence is characterized by emerging independence, identity formation challenges, the development of intimacy, and the formation of romantic relationships (Katzman, 2010; Tolman & McClelland, 2011). Within this context, sexting may be a form of sexual experimentation, a means of addressing emerging sexual feelings, and a way of establishing moral values (Katzman, 2010; Lenhart, 2009). Sexting in the form of explicit images may be a proxy for face-to-face sexual contact for some youth (Lenhart, 2009). Not all teens who sext engage in sexual activity (Dake et al., 2012); thus sexting might be considered beneficial for adolescents. Indeed, sharing sexual content by cell phones allows adolescents to address sexual desires and construct a sexual identity without the pressure of face-to face physical sexual relationships which are often unstable and a source of regret for many adolescents (The National Campaign to Prevent Teen Pregnancy, With One Voice, 2007). Yet sexting can lead to consequences such as engagement in digital media dating violence (Van Ouytsel, et al., 2016).

For other teens, sexting is used to enhance an already sexual relationship (Lenhart, 2009). However, sharing sexual content by cell phone may be problematic as it may promote a view of sex as risk-free. Consequently, sexually inexperienced teens may feel increased pressure to engage in sexual activity before they are physically or mentally ready (Moreno et al., 2009). Early sexual debut (i.e., having sexual intercourse prior to the age of 16) is often associated with psychological maladjustment (Spriggs & Halpern, 2008).

In addition, sexting may be associated with increased sexual behavior. Defining sexting as sending nude or nearly nude photos or videos of themselves or someone else, researchers categorized a sample of young adults (ages 18 – 24) as: non-sexters, receivers, senders, and two-way sexters (i.e., senders and receivers; Gordon-Messer, Bauermeister, Gordonzinski, & Zimmerman, 2012). Although sexting was not related to risky sexual behavior, sexting was associated with increased sexual activity. Receivers of sexts were three times more likely to be sexually active, and two-way sexters were 14 times more likely to be sexually active than non-sexters.

Sparse empirical evidence supports the link between the exchange of text-only sext messages and sexual activity among adolescents. For instance, sex talk on youths’ Facebook profiles is positively related to sexual behavior intent and can negatively affect potential romantic partner perceptions such that adolescents who publicly display sex talk may be viewed as casual sex partners or sexual objects rather than serious relationship partners (Moreno et al., 2012). Moreover, adolescents’ public online references to sex have been associated with increased risks of victimization and unwanted sexual solicitation (Brown et al., 2009). Recent findings suggest that offline sexual coercion has been linked to sexting behaviors such as sending and receiving wanted and unwanted sext messages among adolescents (Choi, Van Ouytsel, & Temple, 2016) and college students (Englander, 2015).

1.3 Sexting and borderline personality features

Borderline personality disorder (BPD) is characterized by impulsive behavior, unstable interpersonal relationships, and desperate attempts to avoid abandonment (American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2013). Because text messaging promotes a perception of constant connectedness, text messaging is one context in which adolescents with borderline features may engage in attention seeking behaviors such as sexting. BPD is typically not diagnosed prior to the age of 18 (APA, 2013); nevertheless, evidence suggests that children and younger adolescents often display precursors of the personality disorder throughout development (e.g., emotional instability; impulsivity; overly close, overly dependent, and unstable interpersonal relationships; and a skewed or unstable sense of self; Crick, Woods, Murray-Close, & Han, 2007). Frequently engaging in sexting could exacerbate vulnerable adolescents’ fears of abandonment, impulsivity, desperate needs to have enmeshed relationships, and a sense of self that relies on attention from others. Adolescents who engage in sexting may receive peer reinforcement for impulsive, attention-seeking behavior, and this may further contribute to the emergence of borderline features.

We expect that BPD features and sexting will be reciprocally related. Individuals with BPD generally experience episodes of anxiety, depression, and mood reactivity in response to environmental stressors (Adams, Bernat, & Luscher, 2001). Adolescents may engage in sexting to cope with negative emotions that are often associated with borderline personality features (e.g., boredom; Lenhart, 2009). Similarly, adolescents with borderline personality features may use sexting to instantaneously avoid feelings of loneliness or to salvage relationships they perceive as being in jeopardy.

Evidence also suggests that sending text messages with sexual content is associated with histrionic personality disorder, social anxiety, and attachment anxiety among young adults (Drouin & Landgraff, 2012; Ferguson, 2011; Reid & Reid, 2007; Weisskirch & Delevi, 2011), as well as low self-esteem (Ybarra & Mitchell, 2014), feelings of hopelessness (Dake et al., 2012), and facets of impulsivity (Champion & Pedersen, 2015; Temple et al., 2014). Adolescents who engage in sexting also experience emotional health issues such as depression, suicide ideation and attempts, and feelings of loneliness (Dake et al., 2012; Temple et al., 2014). Taken together, these findings suggest that examining sexting as it relates to borderline personality features seems warranted.

1.4 Present study

The primary purpose of this study was to identify the prevalence of sexting among a typically developing adolescent sample and to examine how observed sexting relates to sexual activity (sexual intercourse and risky sexual behaviors) and to borderline personality features. Fifteen-year-old participants were provided with BlackBerry devices with paid service plans configured so that the content of text messages sent and received was saved to a secure online archive for later coding and analysis. Four days of text messaging communication was coded for content related to sex, both discussion of actual sex and hypothetical sex. Participants completed a measure of borderline personality features prior to their 10th grade year, and completed a measure of sexual activity and the same measure of borderline personality features at the end of 12th grade.

The current investigation is one of a few studies that have examined text messaging in a naturalistic setting (e.g., reference withheld for blind review, 2014; reference withheld for blind review, 2012). Rather than relying on self-reports, examining participants’ text message communication about sex allows access to what adolescents are saying about their sexual experiences and exploration, thus providing a less biased examination of whether discussions about sex are related to engaging in sexual activity and to borderline personality features.

Boys talk more about sex than girls in online chat rooms (Subrahmanyam, Smahel, & Greenfield, 2006) and feel more comfortable discussing romantic issues with girls in the privacy of digital communication (Pascoe, 2011). Therefore, we hypothesized that:

H1. Boys would engage in sexting more than girls

The co-construction model of development suggests that adolescents’ offline and online relationships may further develop in response to processes taking place in online relationships; for instance, offline relationships may benefit from increased intimacy as online relationships persist (Subrahmanyam & Greenfield, 2008). This development of intimacy may engender exploration and declaration of sexual desires among adolescents which can help facilitate the transition of online sexual relationships to offline sexual relationships (Brown et al., 2011). Thus, even though sexting is not always associated with sexual activity (Dake et al., 2012; Lenhart, 2009), self-reports of sending sexually explicit or suggestive images are found to be consistently related to risky sexual behaviors (Benotsch, Snipes Martin, & Bull, 2012; Dake et al., 2012; Temple et al., 2012) and sex talk displayed on social networking website profiles is associated with the intent to engage in sexual behavior (Moreno et al., 2012) indicating an association between the online activity of sexting and the offline activity of sexual behavior. Therefore, we hypothesized that:

H2. Compared with adolescents who had not engaged in sexting, adolescents who engaged in sexting would report an earlier onset of intercourse and having ever engaged in sexual intercourse (H2a)

We also hypothesized that sexting would be related to having more than one sex partner in the past year (H2b), to having used alcohol or drugs prior to having sexual intercourse within the past year (H2c), and to not using birth control when having sexual intercourse (H2d). Although sexting has been linked to risky sexual behavior for girls (Benotsch et al., 2012; Ferguson, 2011; Temple et al., 2012), this has not been the case for boys. Therefore, we predicted that sexting would only be associated with risky sexual activity for girls (H2e).

Similar to anxiously attached individuals who possess an intense, extreme need for closeness in relationships (Drouin & Landgraff, 2012), individuals with borderline personality features have a strong need for closeness accompanied by impulsivity, leading to tumultuous, clingy, and unstable relationships (Crick et al., 2007; Gunderson, 2007). Empirical evidence suggests that children at risk for developing BPD may have failed to negotiate important developmental tasks such as identity formation and autonomy development (Geiger & Crick, 2001), and adolescents who experience identity issues often engage in risky online behaviors such as sexting (Pridgen, 2010). Findings from these studies provide additional support for the co-construction model of development with adolescents’ digital communication use manifesting psychologically in their offline world. Therefore, we hypothesized that:

H3. Sexting behaviors would be positively associated with borderline personality features (H3a)

Because sexting promotes intimacy without the need for actual physical contact, it was expected that talking about sex via text message communication would predict borderline personality features at age 18 above and beyond sexual activity (H3b). Given that sexting is a novel phenomenon and few studies have examined the relation between sexting behaviors and personality disorder traits, it is difficult to suggest theoretically guided hypotheses with regard to gender differences in this relation. Nonetheless, because girls are more susceptible to internalizing symptoms and self- objectification in relation to sexting than are boys (Brown et al., 2009) we hypothesized that sexting would more strongly relate to borderline personality features for girls (H3c). Further, because borderline personality features and sexting may be reciprocally related, we hypothesized that a predisposition to borderline personality features would predict sexting (H3d).

2. Material and methods

2.1 Participants

Participants included 181 10th grade adolescents (85 girls and 96 boys, 15–16 years old) with text messaging data who participated in an ongoing longitudinal study of relationships and adjustment. Participants were initially recruited when they were either finishing the third grade or beginning the fourth grade of a diverse public school district in the Southwestern United States and were contacted yearly until they completed the 12th grade. Attrition between the 10th grade data collection period and the summer following 12th grade was 12.7%, primarily as a result of participants moving out of state. T-tests revealed that participants with and without 12th grade data did not differ significantly on baseline borderline personality features, t(167) = .43, p =.881 d = 0.11 or overall frequency of sex talk in grade 10, t(179) = .67, p =.526, d = 0.17. The sample was 16.1% African American, 1.0% Asian, 44.9% Caucasian, 14.1% Hispanic, and 7.3% mixed ethnicity (16.6% did not disclose their ethnicity). Parents reported annual income on a five-point scale: less than $25,000 (13.7%), $26,000–$50,000 (14.6%), $51,000 – $75,000 (19.0%), $76,000 – $100,000 (15.6%), and greater than $101,000 (22.9%) (14.1% did not disclose income). Most children had married parents (58.0%), though some had divorced parents (12.7%), never married parents (9.8%), separated parents (3.4%), remarried parents (2.9%), or widowed parents (2.4%). Because our goal was to include all youth who engaged in sexting, our sample included participants reporting other-sex (93.9%) and same-sex sexual encounters (6.1%).

2.2 Procedures

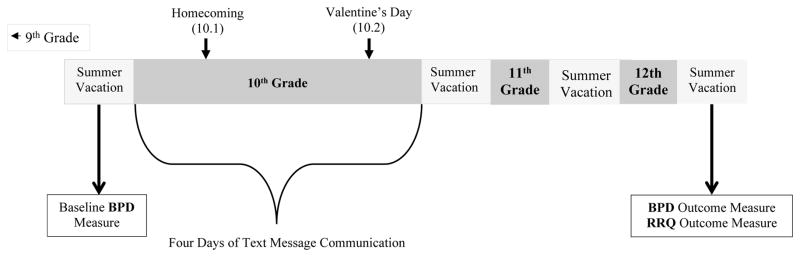

Consent for the children’s participation was initially sought by distributing parental permission letters in the public school classrooms. The initial consent rate for the sample was 55%. A graphical representation of data collection time periods and procedures is included in Figure 1. During the summer before 9th grade, participants were provided with BlackBerry devices with paid service plans including voice minutes, unlimited texting plans, and data plans providing direct access to the Internet. Participants were encouraged to use the BlackBerries as their primary cell phone; however, participants were not prohibited from communicating online using computers and other devices. Although approximately 80% of participants reported owning other cell phones prior to enrolling in the current study (reference withheld for blind review, 2014), analyses of other measures identifying adolescents’ use and liking of the BlackBerry devices and text messaging conversation content provide evidence indicating heavy usage. For example, as substantiated from billing records, the frequencies of text messages sent and received using the BlackBerry devices matched frequencies reported in national survey data (Lenhart, 2012). Further, the instances of open discussions related to sexual themes and conversations containing profanity were similar to those found in previous studies examining adolescents’ conversations in unsupervised digital communication settings, thus indicating that participants were not necessarily concerned with self-censoring (Subrahmanyam et al., 2006; reference withheld for blind review, 2012). Finally, self-reported use and liking of the BlackBerry cell phone indicated heavy usage and preference such that on a 5-point scale participants reported using the device Most of the time and Always (M =4.64, SD =0.70) and liking the device quite a bit with the average response being between Like it and Like it a lot (M =4.65, SD =0.72 (reference withheld for blind review, 2012).

Figure 1.

Timeline of data collection procedures including baseline borderline personality measure, 10th grade text message coding, summer data collection period, and borderline personality and romantic relationships questionnaire 2 years later

All incoming and outgoing digital communication was captured and stored in a secure, off-site archive maintained by Global Relay, a company specializing in archiving text-messaging communication. The archive presents text messages in a readable format so that electronic searches are possible. To address possible ethical concerns, the archive was monitored weekly by searching for a customized list of words and phrases that may indicate the need for intervention (e.g., words that indicate abuse, self-harm, or suicidality). Instances of these words and phrases were flagged and the archive was reviewed by searching content sent and received before and after the flagged word(s) to identify if parents or authorities should be contacted (reference withheld for blind review, 2012).

The current study analyzes four days of text message data collected at two time points during the participants’ 10th grade year, self-reports of dating practices and sexual behaviors collected following the participants’ 12th grade year, and self-reports of borderline personality features collected prior to 10th grade and after 12th grade. The four days of text messaging data were micro-coded as two, 2-day periods identified as Data Point 10.1 and Data Point 10.2.

2.3 Measures

2.3.1. Coding of text messages

In keeping with the overarching goals of our longitudinal study, a detailed micro-coding system for text messaging was developed to capture social aggression, antisocial behavior, sex, and prosocial communication. Although the content of the text messaging was micro-coded for positive talk, neutral talk, social aggression, antisocial behavior, and sex, this study only examined sex talk (i.e., all utterances regarding actual or hypothetical sexual behaviors). An utterance refers to a unit of communication that conveys a complete thought such as a complete sentence (e.g., “Are you coming over today?”) or monosyllabic response (e.g., “Sure”). Each utterance for the two, two-day periods was coded into the categories above by a team of coders trained to use a coding system designed for the current study. Unintelligible text message content was discussed with the entire coding team during ongoing coding meetings. If consensus was not reached, the utterance was coded as neutral talk.

Due to the large volume of text messages received in our archive each month (approximately 500,000 text messages), it was not possible to code all text message communication sent and received. Our goal was to collect text message data during periods of high social activity; thus, the first data point (10.1) includes text messages from a two-day period in the fall leading up to each school’s Homecoming weekend (a major event involving a special football game and a dance). The second data point contains text messages from the second half of the school year, Valentine’s Day and the day prior (10.2). If a participant did not have any text message data during the chosen 2-day period, alternative dates were chosen by searching before and after the 2-day period until two acceptable days were located. A team of undergraduate research assistants formatted the coding transcripts, which were then saved into Microsoft Excel spreadsheets. Data Points 10.1 and 10.2 were saved in separate spreadsheets. Although contacts were labeled in participants’ phone books, they were seldom uniquely identifiable as most phone numbers were stored with a first name only or a nickname. We did not have informed consent from all individuals in participants’ contact lists; however, researchers in the field of digital communication argue that consent is not needed because the information need not be uniquely identifiable (Subrahmanyam et al., 2006).

Transcripts were formatted and randomly assigned to a team of 24-trained coders. Coders were trained on the micro-coding system over an 8-week period. Coders met weekly to discuss coding challenges, and were required to achieve inter-coder reliability greater than κ = .6. A kappa statistic ranging between .61 and .80 is identified as a substantial strength of agreement in terms of inter-rater reliability (Landis & Koch, 1977). The coding coordinator coded 20% of all transcripts for reliability. A de-identified, formatted transcript excerpt, containing sexual behavior content codes is presented in the Appendix, along with definitions and examples of each code.

2.3.2. Sexual behavior content codes

Sexual text message utterances were coded for the specific sexual behaviors being discussed that had actually occurred or were occurring at that time (ACSEX); or discussions of sexual behaviors that were planned, might occur, or had not yet occurred (HYSEX, i.e., what if or have you ever scenarios). Content codes included arousal, kiss, rub, oral, sex, and gensex. Examples and definitions of the sexual behavior content codes are presented in the Appendix.

Analyses of the 10.1 and 10.2 data revealed that five of the “AC” sex talk codes (ACARSL, ACGENSEX, ACKISS, ACRUB, and ACSEX) were reliable (κ = .63, .64, .71, .67, and .70, respectively). Further, five of the “HY” sex talk codes (HYRARSL, HYKISS, HYORAL, HYRUB, and HYSEX) were reliable (κ = .62, .85, .87, .69, and .73, respectively).

2.3.3. Early sexual activity and risky sexual behaviors

Designed for the current study, the 40-item Romantic Relationships Questionnaire (RRQ) assessed dating practices and risky sexual behaviors as participants moved into adolescence, and was adapted from the Dating Questionnaire (Connolly, Craig, Goldberg, & Pepler, 2004), the Romantic History Questionnaire (RHQ; Buhrmester, 2001), and the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health (Add Health; see Harris et al., 2009). The RRQ was first administered during the summer prior to participants entering the 8th grade and was modified throughout the longitudinal study to accommodate their increasing maturity. Participants reported on sexual activity following completion of the 12th grade by completing seven items from the RRQ. The first item assessed sexual intercourse experience defined as vaginal or anal intercourse, in the context of same-sex and/or opposite sex experiences, “Have you ever had sex with someone of the opposite sex?; “Have you ever had sex with someone of the same sex?” The second item assessed age of sexual debut: “How old were you the first time you ever had sex with someone of the opposite sex?”; “How old were you the first time you had sex with someone of the same sex?” To capture a more complete representation of sexual activity the same-sex questionnaire items were also included for all questions inquiring about risky sexual behaviors. For all analyses, the sexual activity question related to having ever had sex (with either a same-sex or other-sex partner) was dummy coded with “0” indicating not having had sexual intercourse and “1” indicating having had sexual intercourse. Early sexual debut was dummy coded “0” and“1” with “0” indicating either having had sex after the age of 15 or having never had sex and “1” indicating having had sex prior to the age of 16.

The last five items identified risky sexual behaviors occurring over the last year such as having multiple sex partners, alcohol and drug use in connection with sex, and having sex without birth control. Participants reported on how many different partners they had sexual intercourse with and substance use in connection with sex (“How often has alcohol been part of your romantic and sexual activities?”; “How often have drugs been part of your romantic and sexual activities?”). These two questions were rated on a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 = Never to 5 = Always. Last, participants reported how often they used some form of birth control or disease prevention when having sex and how often they themselves or their partner wore a condom when having sex; responses for these items ranged from 0 = Never to 5 = Every time. Participants could also indicate that they had not had sex.

The RRQ contained modified versions of questions assessing risky sexual behavior taken from the Add Health survey, which assesses health-risk behaviors among adolescents (see Harris et al., 2009). Reliability for the scores on theses scales from the Add Health survey has been demonstrated with alpha coefficients among Wave 1 participants ranging from .72 to .87 (Sieving et al., 2001). However, subscale items related to substance use with sex and contraceptive use self-efficacy had lower internal consistency (α = .65 for both subscales). Previous studies have found that reliability of self-reported sexual behaviors among adolescents and young adults tends to be moderate with mean reliability ranging from .51 to .66 (see Schrimshaw, Rosario, Meyer-Bahlburg, & Scharf-Matlick, 2006). Reliability for the items assessing contraceptive use and substance use in connection with sex in the current study was .59, which falls within the range of .51 and .66 from previous research using adolescents’ self-reports of sexual behavior.

2.3.4. Borderline personality disorder features

During the summer prior to beginning 10th grade, participants completed the McLean Screening Measure for BPD (MSI-BPD; Zanarini et al., 2003), as a baseline measure of borderline personality features. During a laboratory visit of the summer following the 12th grade, participants again completed the McLean Screening Measure for BPD as a follow up measure. The McLean screening measure is a 10-item, dichotomous, self-report measure for measuring BPD in adolescents and adults. The 10 items of the MSI-BPD target all nine of the DSM-IV criteria for BPD. Sample items from the MSI-BPD include, “Have you had at least two other problems with impulsivity (e.g., eating binges and spending sprees, drinking too much and verbal outbursts?”); and “Have you chronically felt empty?” Items of the MSI-BPD were summed to obtain a total score; higher scores indicate more features of BPD. The McLean screening measure has been shown to be reliable in an outpatient sample of 101youth ages 15 – 25, α = .78, and displayed convergent validity with other measures of BPD (Chanen et al., 2008). The measure was successful in correctly identifying cases and non-cases of BPD in early adulthood (18–25), with .90 (sensitivity) and .93 (specificity); the internal consistency was also acceptable, α = .74 (Zanarini et al., 2003). Reliability of the BPD-MSI in the current study was similar to past research (10th grade: α = .76; 12th grade: α =.81).

3. Results

3.1. Prevalence rates and gender differences in sex talk

During the four days in which text messaging was micro-coded, a total of 181 participants sent and received an average of 713 text message utterances containing both sexual and non-sexual content, with a range of 2 to 5396 utterances. The overall frequency of sex talk was highly variable across the sample with about 35% (n = 63) not engaging in sex talk, 24% (n = 44) engaging in 1–5 utterances, and about 18% (n = 33) sending and/or receiving greater than 30 sex talk utterances during the four-day period. Independent samples t-tests revealed no significant gender differences in overall frequency of sex talk, t(179) = −.87, p = .577, d = 0.13 (H1). However, we did find differences in frequency of sex talk and having ever had sex between adolescents indicating same-sex sexual encounters and those who had not had same-sex sexual encounters. Adolescents indicating same-sex sexual encounters (n = 11) engaged in more sex talk utterances t(153) = 3.49, p = .001, d = 0.63, and endorsed having ever had sex t(153) = 2.95, p = .001, d = 1.25, more often than those who answered no to the same-sex item. Additional t-tests revealed that participants endorsing same-sex sexual encounters versus those who had not had same-sex sexual encounters did not significantly differ on any other variables.

Table 1 presents descriptive statistics for each sexual behavior content code for those participants engaging in sex talk (n = 118). Over the four-day period, these participants sent and received a total of 3,594 sex talk utterances.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics and Intercorrelations of Text Message Utterances Containing Actual Sex Talk and Hypothetical Sex Talk Over a 4-Day Period (Kappa Values in Parentheses)

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | Participants Engaging in Utterances | M | SD | Min | Max | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ACARSL | (.63) | 48 (26.52%) | 2.76 | 6.95 | 0 | 56 | ||||||||||||

| 2 | ACGENSEX | .30** | (.64) | 28 (15.47%) | 0.56 | 1.41 | 0 | 8 | |||||||||||

| 3 | ACKISS | .28** | .10 | (.71) | 33 (18.23%) | 0.80 | 2.14 | 0 | 17 | ||||||||||

| 4 | ACORALa | .07 | −.03 | .07 | - | 9 (4.97%) | 0.19 | 0.90 | 0 | 7 | |||||||||

| 5 | ACRUB | .72** | .16* | .08 | .03 | (.67) | 23 (12.71%) | 0.93 | 3.78 | 0 | 35 | ||||||||

| 6 | ACSEX | .47** | .37** | .13 | .05 | .30** | (.70) | 42 (23.20%) | 1.27 | 2.68 | 0 | 15 | |||||||

| 7 | HYARSL | .71** | .29** | .18* | .01 | .58** | .32** | (.62) | 59 (32.60%) | 5.44 | 12.05 | 0 | 74 | ||||||

| 8 | HYGENSEX | .63** | .24** | .05 | .01 | .59** | .27** | .75** | (.52) | 75 (41.44%) | 4.81 | 9.21 | 0 | 45 | |||||

| 9 | HYKISS | .46** | .06 | .23** | −.02 | .35** | .24** | .67** | .63** | (.85) | 58 (32.04%) | 3.44 | 8.23 | 0 | 60 | ||||

| 10 | HYORAL | .71** | .17* | .17* | .08 | .60** | .35** | .88** | .67** | .71** | (.87) | 40 (22.10%) | 2.35 | 6.33 | 0 | 43 | |||

| 11 | HYRUB | .48** | .14 | .06 | −.02 | .67** | .29** | .66** | .69** | .65** | .66** | (.87) | 42 (23.20%) | 1.75 | 4.21 | 0 | 28 | ||

| 12 | HYSEX | .86** | .15* | .25** | .11 | .65** | .44** | .80** | .62** | .60** | .86** | .59** | (.73) | 69 (38.12%) | 6.16 | 15.20 | 0 | 131 | |

| 13 | TOTSEX | .85** | .26** | .25 | .07 | .71** | .45** | .92** | .82** | .75** | .92** | .76** | .92** | (.80) | 118 (69.12%) | 57.48 | 30.46 | 1 | 412 |

Note:

p < .05,

p < .01.

Codes beginning with the temporal prefix “AC” indicate discussions of actual sexual activity and codes beginning with the temporal prefix “HY” indicate discussions of hypothetical sexual activity.

The ACORAL code did not appear in any of the coded reliability transcripts.

Participants’ discussion of the individual sexual behaviors varied in frequency and content. Frequency counts of sex talk utterances grouped by actual sex talk versus hypothetical sex talk revealed that the majority of sex talk utterances were text messages related to discussions of hypothetical (HY, n = 108 sending or receiving one or more sex talk utterances) as opposed to actual (AC, n = 81 sending or receiving one or more sex talk utterances) sexual behavior. Independent samples t-tests revealed significant gender differences with boys sending and receiving more utterances than girls discussing actual sexual behavior: general sexual activity, t(179) = −1.40, p = .014, d= 0.21; kissing, t(179) = −2.10, p < .001, d= 0.31, and oral sex, t(179) = −2.23, p < .001, d = 0.33. However, no gender differences emerged for discussions of hypothetical sexual behavior (arousal t(179) = −0.63, p = .772, d = 0.09; general sexual activity, t(179) = −0.29, p = .800, d = 0.04; kissing, t(179) = −0.84, p =.242, d = 0.13; oral sex, t(179) = −0.54, p = .584, d = 0.08; rubbing, t(179) = 0.27, p = .262, d = 0.04; and sexual intercourse, t(179) = −1.22, p = .139, d = 0.18). Table 1 also displays correlations among the sex talk codes within each temporal prefix over the four-day period examined. With the exception of the actual oral sexual behavior content code, the majority of the sexual behavior content codes were moderately to strongly correlated (r’s ranged from .24 to .88). Inter-item correlation analyses revealed that the actual sexual behavior codes were moderately inter-correlated (average r = .21) and the hypothetical sex talk codes were strongly correlated (average r = .70). Overall the actual and hypothetical sex talk codes were moderately correlated (r = .38).

3.2. Relation between sex talk and sexual activity

Table 2 presents zero-order correlations between sending and receiving text messages about sex in grade 10 (age = 16) and self-reports of sexual behaviors at age 18. Text messaging about hypothetical and actual sex were both correlated with early sexual debut (H2a), having multiple sex partners (H2b), and drug use in combination with sexual activity at age 18 (H2c), as well as with borderline personality features (H3a). In addition, text messaging about hypothetical sex was associated with having ever had sex (H2a).

Table 2.

Correlations between Text Message Communication about Sex, Borderline Personality Features, and Sexual Behaviors in Adolescents

| Study Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Hypothetical Sex Talk Grade 10 | |||||||||||

| 2. | Actual Sex Talk Grade 10 | .76** | ||||||||||

| 3. | Borderline Features Grade 10 | .19* | .12 | |||||||||

| 4. | Borderline Features Age 18 | .34** | .22** | .44** | ||||||||

| 5. | Early Sexual Debut a | .24** | .18* | .29** | .28** | |||||||

| 6. | Ever Had Sex a | .18* | .15 | .33** | .35** | .49** | ||||||

| 7. | Multiple Sex Partners Age 18 | .63** | .63** | .03 | .27** | .33** | .28** | |||||

| 8. | Alcohol and Sex Age 18 | .08 | .14 | .06 | .14 | .25** | .27** | .29** | ||||

| 9. | Drugs and Sex Age 18 | .28** | .34** | .01 | .28** | .38** | .23** | .56** | .51** | |||

| 10. | Inconsistent Birth Control Age 18 | .10 | .09 | .09 | .28** | .11 | .46** | .07 | .12 | .11 | ||

| 11. | Inconsistent Condom Use Age 18 | .14 | .05 | .30** | .30** | .24** | .38** | .08 | .09 | .24** | .36** | |

|

| ||||||||||||

| M | 15.61 | 4.25 | 1.97 | 2.30 | .26 | .59 | 1.44 | 1.40 | 1.23 | 2.01 | 1.74 | |

| SD | 40.09 | 10.50 | 2.14 | 2.44 | .44 | .49 | 4.29 | .74 | .69 | 1.62 | 1.36 | |

Note:

p < .05;

p. < .01.

Mean value is proportion of participants coded as “1” indicating endorsement of specified sexual

By age 18, 45.1% of girls and 54.9% of boys reported having ever had sex, with 40.0% of sexually active girls and 60.0% of sexually active boys reporting an early sexual debut (i.e., before the age of 16). Of those reporting having had sexual intercourse, 39.0% of girls and 48.0% of boys indicated having more than one sexual partner over the previous 12 months. Independent samples t-tests revealed significant gender differences with respect to drug use in combination with sexual activity, t(101) = −1.63, p = .004, d = 0.32; with boys (26.0%) being were more likely than girls (13.3%) to report having engaged in this behavior. There were no differences between girls (38.9%) and boys (38.0%) when reporting alcohol use in combination with sexual activity, t(101) = −0.09, p =.323, d = 0.02. About 57% of teens (26.8% of girls and 30.0% of boys) reported having never used birth control in the last 12 months and 19.5% of girls as well as 14.0% of boys reported never using condoms over the last 12 months when engaging in sexual activity. The remaining responses to the item measuring birth control use and disease prevention were inconsistent across the sample with 29.7% of participants endorsing the use of some type of birth control or disease prevention most times, 6.6% endorsing birth control use or disease prevention half of the time, and 16.5% endorsing the use of birth control or disease prevention only sometimes during the last 12 months.

Logistic regression analyses examined whether degree of sex talk predicts engaging in sexual behaviors. Square root transformations were performed on all count variables used in the regression analyses (i.e., frequency of sex talk). The effects of gender (effects coded such that girls = −1 and boys = 1) were examined in all analyses and all continuous predictor variables were grand-mean centered. The logistic regression analysis model examining whether sexting in grade 10 (age 16) predicts sexual activity at 18 years, and whether such a relation is moderated by gender, is represented by the following regression equation:

Engaging in hypothetical sex talk increased the odds of having ever had sex by 1.51 and engaging in actual sex talk increased the odds of ever having had sex by 1.62 (H2a; see Table 3). The main effect of gender was not significant; however, the interaction between sex talk and gender was significant for hypothetical sex talk and marginally significant for actual sex talk. Simple slopes analyses (Aiken and West, 1991) revealed that girls who engaged in hypothetical sex talk in grade 10 (age 16) were 2.07 times more likely to have had sex by age 18 (p = .005); in contrast, boys who engaged in hypothetical sex talk were only 1.10 times more likely to have had sex by age 18 (p = .291) (H2e). In addition, as shown in Table 3, texting about hypothetical and actual sex at age 16 both enhanced the likelihood of having had an early sexual debut; however, these findings did not differ by gender (H2e).

Table 3.

Logistic Regression Examining Hypothetical (HYSEX) and Actual (ACSEX) Sex Talk in Grade 10 Predicting Adolescent Sexual Activity at Age 18

| Ever Had Sex | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Predictors | b | SE | exp (b) | p | 95% C.I.a |

| Gender | −.28 | .24 | .76 | .247 | .48 – 1.21 |

| HYSEX Sex Talk GR 10 | .41** | .14 | 1.51 | .003 | 1.15 – 1.97 |

| HYSEX Sex Talk GR 10 X Gender | −.32* | .14 | .73 | .021 | .55 – .95 |

| Constant | .66* | .24 | 1.94 | .005 | |

|

| |||||

| b | SE | exp (b) | p | 95% C.I.a | |

|

| |||||

| Gender | −.09 | .20 | .91 | .647 | .62 – 1.34 |

| ACSEX Sex Talk GR 10 | .49* | .22 | 1.62 | .026 | 1.06 – 2.49 |

| ACSEX Sex Talk GR 10 X Gender | −.37† | .22 | .69 | .089 | .45 – 1.06 |

| Constant | .48* | .20 | 1.62 | .014 | |

| Early Sex Debut | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Predictors | b | SE | exp (b) | p | 95% C.I.a |

| Gender | .13 | .20 | 1.14 | .508 | .78 – 1.66 |

| HYSEX Sex Talk GR 10 | .17* | .06 | 1.18 | .009 | 1.04 – 1.33 |

| HYSEX Sex Talk GR 10 X Gender | .02 | .06 | 1.02 | .724 | .90 – 1.16 |

| Constant | −1.12*** | .19 | .33 | <.001 | |

|

| |||||

| b | SE | exp (b) | p | 95% C.I.a | |

|

| |||||

| Gender | .14 | .19 | 1.15 | .460 | .79 – 1.66 |

| ACSEX Sex Talk GR 10 | .28* | .13 | 1.32 | .025 | 1.04 – 1.69 |

| ACSEX Sex Talk GR 10 X Gender | −.04 | .13 | .96 | .755 | .75 – 1.23 |

| Constant | −1.10*** | .19 | .33 | <.001 | |

Note: Gender was effects coded such that girls = −1 and boys = 1.

C.I. = confidence interval for exp (b).

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001,

< .10.

3.3. Relations between sex talk in grade 10, adolescent sexual activity, and borderline personality features at age 18

Linear multiple regressions were conducted using the following equation to test the hypothesis that communicating about sex via text messages in grade 10 predicts borderline personality features two years later, at age 18 (H3b):

Table 4 presents the results for text messages about hypothetical sex and risky sexual behavior. Cook’s distances were calculated to identify possible outliers. Regression analyses were run with and without outliers and results did not substantially change; thus, all analyses presented in the current study include outliers. To coincide with text messaging data time of collection, 10th grade baseline levels of borderline personality features were also included as a control variable. Because ‘alcohol and sex’, and ‘drugs and sex’ were strongly correlated with one another (r = .51; see Table 2), a composite variable called substance use and sex was created and examined as a predictor. Similarly, a composite variable called pregnancy and disease risk was created that combined the variables of inconsistent birth control use and inconsistent condom use (r = .36). Results indicated that discussing hypothetical sex via text message communication in grade 10 (age 16) significantly predicted borderline personality features two years later at age 18, even when controlling for baseline borderline personality features and when including adolescent sexual behavior in all of the regression models (H3b). No gender differences emerged (H3c).

Table 4.

Hypothetical Sex Talk via Text Message Communication in Grade 10 and Adolescents’ Risky Sexual Behavior Predicting Borderline Personality Disorder Features at Age 18

| Predictors | Borderline Personality Features at Age 18 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ever Had Sex | b | SE | β | p |

|

| ||||

| Constant | 1.75*** | .28 | .000 | |

| Gender | −.18 | .28 | −.07 | .503 |

| Borderline Personality Features Grade 10 | .37*** | .09 | .32 | .000 |

| Ever Had Sex | .94* | .38 | .19 | .015 |

| Ever Had Sex X Gender | .10 | .37 | .03 | .789 |

| Hypothetical Sex Talk Grade 10 | .21** | .06 | .25 | .001 |

| Hypothetical Sex Talk Grade 10 X Gender | .01 | .06 | .02 | .816 |

|

| ||||

| Early Sexual Debut | b | SE | β | p |

|

| ||||

| Constant | 2.13*** | .21 | .000 | |

| Gender | −.13 | .20 | −.06 | .515 |

| Borderline Personality Features Grade 10 | .39*** | .09 | .34 | .000 |

| Early Sex Debut | .70 | .44 | .12 | .112 |

| Early Sex X Gender | .04 | .43 | .01 | .919 |

| Hypothetical Sex Talk Grade 10 | .22** | .06 | .26 | .001 |

| Hypothetical Sex Talk Grade 10 X Gender | −.00 | .06 | −.00 | .970 |

|

| ||||

| Substance Use and Sex | b | SE | β | p |

|

| ||||

| Constant | 2.32*** | .18 | .000 | |

| Gender | −.16 | .18 | −.07 | .362 |

| Borderline Personality Features Grade 10 | .43*** | .08 | .38 | .000 |

| Substance Use and Sex | .88* | .35 | .22 | .012 |

| Substance Use and Sex X Gender | −.21 | .35 | −.06 | .546 |

| Hypothetical Sex Talk Grade 10 | .21** | .06 | .25 | .001 |

| Hypothetical Sex Talk Grade 10 X Gender | .03 | .06 | .04 | .632 |

|

| ||||

| Use of Birth Control and Disease Prevention | b | SE | β | p |

|

| ||||

| Constant | 2.28*** | .17 | .000 | |

| Gender | −.04 | .17 | −.02 | .790 |

| Borderline Personality Features Grade 10 | .39*** | .08 | .34 | .000 |

| Pregnancy and Disease Risk | .47** | .15 | .23 | .002 |

| Pregnancy and Disease Risk X Gender | −.13 | .15 | −.07 | .375 |

| Hypothetical Sex Talk Grade 10 | .19** | .06 | .22 | .003 |

| Hypothetical Sex Talk Grade 10 X Gender | .06 | .06 | .07 | .318 |

|

| ||||

| Multiple Sex Partners | b | SE | β | p |

|

| ||||

| Constant | 2.36*** | .18 | .000 | |

| Gender | −.13 | .18 | −.06 | .458 |

| Borderline Personality Features Grade 10 | .40*** | .09 | .35 | .000 |

| Multiple Sex Partners | .79† | .42 | .21 | .060 |

| Multiple Sex Partners X Gender | .05 | .41 | .01 | .903 |

| Hypothetical Sex Talk Grade 10 | .16* | .07 | .18 | .028 |

| Hypothetical Sex Talk Grade 10 X Gender | −.04 | .07 | −.05 | .561 |

Note: Gender was effects coded such that girls = −1 and boys = 1.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001,

< .10.

Next, analyses examined whether text messaging about actual sex and risky sexual behavior were predictors of borderline personality features at age 18. Discussing actual sex via text messaging was not a significant predictor in any of the models.

3.4. Concurrent relations between borderline personality features and engaging in sex talk

The regression model examining whether borderline personality features measured during grade 10 predicts concurrent digital communication about sex is represented by the following equation:

The analyses did not yield any significant effects or interactions involving gender for borderline personality features predicting hypothetical or actual sex talk (H3d).

4. Discussion

Overall, the results supported the hypotheses that sexting at age 16 would be associated with sexual activity and risky sexual behavior (H2), and borderline personality features at age 18 (H3). Findings from this naturalistic study of text messaging suggest that sexting can be viewed as a modern expression of normal adolescent sexual development (Angelides, 2013). In this typically developing sample, 65% of adolescents engaged in sexting, with 92% of those engaged in sexting sending or receiving at least one text message discussing hypothetical sexual behaviors, and 68% of sexting participants sending or receiving at least one text message discussing actual sexual behavior. Despite being a normative behavior, these finding suggest that sexting may also be associate with increased risk.

The current study’s prevalence rates are much higher than those from national surveys and previous studies examining adolescents’ self-reports of exchanging nude pictures which range from 1.3% to 15% (Lenhart, 2009; Mitchell, Finkelhor, James, & Wolak, 2012) and from 15% to 50% (Dake et al., 2012; Dowdell, Burgess, & Flores, 2011; Strassberg, McKinnon, Sustaita, & Rullo, 2012; Temple et al., 2012). However, these prevalence rates are comparable to investigations examining sending and receiving sexually suggestive text-only messages which range from 54% (Fleschler-Peskin et al., 2013) to 87% (NCPTUP, 2008).

Although boys were hypothesized to engage in sexting more than girls (H1), our findings were consistent with previous studies of sexting that have no found gender differences in the overall sexting behavior (Gordon-Messer et al., 2012; Temple et al., 2012; Weisskirch & Delevi, 2011). However, boys’ texting contained more utterances discussing sexual behavior that had actually occurred, suggesting that boys might be more willing to discuss actual sexual experiences than girls. Alternatively, boys might have more peers who discuss actual sexual activity than girls. It is also possible that boys are more likely to talk about sexual behavior as having occurred (even if it has not) as a way of developing and sharing a sexual identity.

Adolescent exposure to sex talk is associated with the intent to engage in sexual behavior and promotes sexually permissive attitudes, which may encourage adolescents to engage in risky sexual behaviors (Moreno et al., 2012). These results showed that engaging in sexting at age 16 was associated with reporting an early sexual debut and having sexual intercourse experience (H2a), having multiple sex partners (H2b), and engaging in drug use in combination (H2c) with sexual activity two years later. These findings are consistent with previous research that has found associations between exchanging sexually explicit images and having sexual intercourse (Temple et al., 2012), having multiple sex partners (Dake et al., 2012; Temple et al., 2012), and using alcohol or drugs prior to engaging in sexual activity (Temple et al., 2012). These results examining the actual content of adolescents’ text messaging provide additional evidence that adolescents’ sexting relates to engaging in risky sexual behaviors rather than promoting safe sex practices when engaging in physical sexual intercourse (Temple et al., 2012). However, it is important to note that relations between sexting and sexual activity are likely reciprocal. Having engaged in sexual intercourse was a predictor of text messaging about hypothetical sex. The findings support the possibility that text messaging about hypothetical sex might be part of a constellation of risky behavior including sexual activity.

Results partially supported the hypothesis that engaging in sex talk would be associated with risky sexual activity for girls, but not for boys (H2e). Girls who exchanged text messages about hypothetical sex were more likely than boys to have had sexual intercourse by age 18. These findings imply that girls might engage in sexting as a relationship strategy when involved in an intimate relationship or as an invitation to engage in sexual activity when one hopes to be in a relationship (Lenhart, 2009). Young women tend to engage in unwanted but consensual sexting more so than young men, particularly as a result of commitment manipulation (e.g., if you loved me you would send me a sext; Drouin et al., 2015). In addition, girls who present themselves as being very sexual are at risk for sexual solicitation, which in turn may lead to sexual activity (Brown et al., 2009). For boys, sexting might be perceived more permissively and positively, and thus not necessarily be related to actual sexual activity or risky sexual behavior (Temple et al, 2012). Boys feel more comfortable discussing romantic topics via digital communication than girls and prefer to discuss these topics using digital communication rather than talking face-to-face (Pascoe, 2011). For boys then, sexting may be part of an experimental phase (Lenhart, 2009).

Results supported the hypothesis that sexting at age 16 would be associated with borderline personality features at age 18, but only for discussions of hypothetical sex (H3b). Discussing hypothetical sex at age 16 predicted borderline personality features at age 18 even when controlling for pre-existing borderline personality features and for risky sexual behavior. Perhaps discussions of actual sex occurred in the context of a romantic relationship, and thus were less indicative of impulsivity and attention seeking than frequent sexting about hypothetical sexual behaviors.

Texting about hypothetical sex may become habitual and facilitate the impulsive, sensation-seeking features of borderline personality. These findings suggest that sexting may contribute to psychological distress for adolescents, as has also been found in previous work (Delevi & Weisskirch, 2013; Drouin & Landgraff, 2012; Ferguson, 2011). Certain features of borderline personality, such as inappropriate emotional expression and mood reactivity may intensify in ambiguous relational situations such as texting about hypothetical sex. Considering that adolescents’ sext messages are typically overly aggressive (NCPTUP, 2008), senders of text messages about hypothetical sex may engage in behaviors that are perceived as sexually harassing (Valkenburg & Peter, 2011); thus the receiver of a sext may not respond or might respond in a rejecting manner. Texting about hypothetical sex might relate to borderline personality features through its association with increased risks of rejection and thereby increase affective instability in the sender.

The results did not support the hypothesis that having a predisposition to borderline personality predicts adolescents engaging in text message conversations about sex (H3d). Although previous studies have found a link between psychological maladjustment such as depression, anxiety, and low self-esteem and sexting (Gordon-Messer et al., 2012), these studies have relied on concurrent, self-report measures that may be biased by social desirability, whereas this study examined the actual content of sexting.

4.1. Limitations and strengths

The findings of this study must be interpreted in light of methodological limitations. First, for ethical reasons and because of technological limitations, the current study did not examine the practice of sending or receiving sexually explicit pictures; therefore it was not possible to examine differences in behavioral outcomes between the two sexting behaviors (i.e., sending text-only sex messages and sending sexual images). Nevertheless, it is interesting that the correlates of exchanging text-only sex messages within the current adolescent sample were similar to findings of previous research examining sending or receiving sexually explicit images (Benotsch et al., 2012; Dake et al., 2012; Ferguson, 2011; Gordon-Messer et al., 2012; Temple et al., 2012). These similarities suggest there might be few differences in behavioral outcomes between the two types of sexting behaviors. In addition, although previous research examining these data suggests that adolescents communicated openly over the course of the longitudinal study (reference withheld for blind review), it is possible that participants censored their communication because they knew it was being monitored. However, considering the high prevalence rate of sexting among participants it is highly unlikely that participants were concerned with self-censoring.

Second, receivers of adolescents’ text messages were not always clearly identifiable. Consequently, it was difficult to determine whether the exchange of sexual text messages occurred exclusively between romantic partners, potential romantic partners, or casual sex partners. Prior research suggests that sexting is typically a reciprocal behavior that tends to be very common in romantic relationships (Drouin & Landgraff, 2012; Gordon-Messer et al., 2012). Yet adolescents who participate in sexting with individuals they are simply seeking to hook-up with are likely to incur sexual risks such as having sex with a new partner for the first time after sexting with them, having sexual intercourse with multiple partners, and having unprotected sex (Benotsch et al., 2012). Future research should examine the context in which sexting occurs.

It is also important to note that the current study did not distinguish between sending and receiving sext messages and it is possible that sending sexual text messages and receiving sexual text messages might be associated with distinct outcomes. For example, receivers of sexts were three times more likely to report having ever sex had and two-way sexters were 14 times more likely to having ever had sex compared to non-sexters (Gordon-Messer et al., 2012).

The current study’s data were coded using microcoding techniques in which trained individuals categorized each text message utterance into a small set of categories. Thus, a more traditional coding system was utilized in analyzing a portion of the large corpus of text messages sent and received among participants. Considering the massive volume of text messaging data archived on a monthly basis (i.e., approximately 500,000 text messages) it may have been advantageous to utilize a more contemporary, technologically focused analytical method such as text mining in assessing the micro level content of text messages exchanged. Future studies should consider the application of such data mining techniques to possibly enhance the quality of information obtained by means of text messaging communication.

Last, it is most important to note that although sexting predicted engaging in risky sexual behavior and borderline personality features two years later, the findings should be interpreted with caution as we cannot determine causality from these findings. We did not explicitly examine whether adolescents’ sexual experiences preceded or followed sexting behaviors. Sexting is often reported as a common practice among teens already in sexually active relationships (Lenhart, 2009). In these instances, sexting behaviors would precede sexual intercourse. Perhaps sexting enhances intimacy in these relationships which is thought to be an important aspect of adolescent development. Future studies should examine sexting and sexual behaviors among teens with the intent of identifying whether the online practice of sexting is a preliminary step to physical sexual activity or an enhancement of sexual activity. Still, this research had important strengths. First, this is one of the first studies of sexting to examine the actual content of adolescents’ text message communication. These results may provide a more objective view of the prevalence of sexting and of the association between adolescent sexting and sexual activities. Second, this is the first study to examine the association between sending text message communication about sex and borderline personality features. Most previous research has investigated sexual behavioral outcomes associated with the practice of sending or exchanging nude or semi-nude images; few studies have examined the association between the more frequent practice of sending text-only sex messages and psychological outcomes such as borderline personality disorder. These results support the importance of understanding the implications of exchanging text messages containing written sexual content among adolescents.

4.3 Conclusions

Given that adolescents feel more comfortable flirting and communicating by text message as a prelude to participating in face-to-face dating practices (Pascoe, 2011), sexting might play a major role in adolescents initiating and maintaining interpersonal relationships that will eventually move to and persist in offline forums. However, the current study suggests that texting about hypothetical sexual situations might be problematic as this behavior predicts future borderline personality features. So although sexting may add to the perception of intimacy in a relationship, it may also increase over-reactivity to interpersonal attention that contributes to the emergence of borderline personality features.

So that we can begin to develop theoretical models related to the behavior of sexting and with the goal of understanding the impact of sexting behaviors on adolescents’ well-being, as well as any social implications of sexting, future analyses should include other measures of adjustment that might be related to this behavior. For instance, future research could explore other personality characteristics that might be related to sexting such as impulsivity, conscientiousness, openness, sensation seeking, and low self-esteem. In addition, because sexting has been linked to sleep deprivation and fatigue (Chalfen, 2010), future research might examine whether there is an association between sexting and physical health issues such as somatic complaints. Future research should also continue to examine the actual content of adolescents’ text message communication rather than relying on adolescents’ self-reports of sending sext messages. Careful investigation of the effects of sexting could bolster prevention and education programs to mitigate the potential consequences associated with the misuse of technology and with early sexual activity for adolescents.

Highlights.

65% of adolescents engaged in sending or receiving texts with written sexual content.

Sexting at age 16 predicted risky sexual activity at age 18.

Texting about hypothetical sex at age 16 predicted borderline personality features at age 18.

Acknowledgments

The preparation of this manuscript was supported by two grants from the Eunice Kennedy Schriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development: R01 HD060995 and R21 HD072165. We are grateful to the adolescents and families who participated, to an excellent team of coders, and to a local school system who prefers to go unnamed.

Appendix – Definitions of Codes and an Excerpt from a Transcript

| Definition of Content Codes and Examples | Excerpt from a Transcript |

|---|---|

| Hypothetical Sex (HY) - Utterances discussing sexual behaviors that have not actually occurred, “You should come over after school so we can have sex.” | (05:53:29 PM EST) Max says to Participant (SMS): Ok wat u doin |

| Actual Sex (AC) - Utterances recalling sexual encounters that one has engaged in or is currently engaging in, “After the party on Thursday, Tina and I did it.”, “My hands are back in motion now.” referring to masturbation. | (05:53:45 PM EST) Max says to Participant (SMS): Ok babi u tired |

| Arousal (ACARSL, HYARSL) - Utterances discussing being aroused without mentioning specific sexual behaviors, “I’m so horny”; “I love it when you’re naughty” | (05:53:53 PM EST) Participant says to Max (SMS): N im runnin my hands up n dwn yo body 2 be continued…;) (HYRUB)* |

| Kissing (ACKISS, HYKISS) - Utterances discussing kissing or making out, “I saw Rob kissing Tina” | (05:53:54 PM EST) Participant says to Max (SMS): U calm dwn n say im sorry n i say 4wht u say i nutted n i say thts y im on birthcontrol nw its yo turn 2 b on top n i climb to the back n pull u on top of me (HYSEX)* |

| Rub (ACRUB, HYRUB) - Utterances describing instances of grabbing or rubbing a body part (e.g., discussing masturbation or “grinding” on someone), “Tim was grinding on Ms. Johnson at the dance”, “My hands are back in motion now.” | (05:53:55 PM EST) Participant says to Max (SMS): Right n my pussy cuz u 4got 2 pull out bt u dnt care @ the moment n u shakin n breathn hard but i say nw baby U gt used to tht cuz u aint had no real pussy n (HYSEX)* |

| Oral (ACORAL, HYORAL) - References to oral sex or alluding to, but not actually mentioning oral sex, “What would you be doing on your knees if you were here, “Joycelyn gave me a blow job yesterday” | (05:53:55 PM EST) Participant says to Max (SMS): N go real fast n it strt feelin so good u srtt scratchin my ass n back n runnin yo hands thru my hair n pullin it til u say O SHIT n bust a big ass nut (HYRUB, HYSEX)* |

| Sex (ACSEX, HYSEX) - References to vaginal or anal sexual intercourse, “How many girls have you had sex with?”, “I’ve screwed 10 girls” | (05:53:56 PM EST) Participant says to Max (SMS): (HYSEX)* I gt used to it so i speed up n let it go deeper n moan n it str feel in better the deeper n faster i go n the more moanin i do thn i strt short strokin a lil |

| Gensex (ACGENSEX, HYGENSEX) - Discussions of engagement in obvious sexual behavior, however, it is unclear which specific sexual behavior is being discussed, ““How far have you gone?”, “Josh totally made his move last night.” | (05:53:57 PM EST) Participant says to Max (SMS): (HYRUB, HYKISS, HYSEX)* Grind on yo dick thru yo pants n let u kiss on my neck n tits thn i slowly inch on yo dick shile yo hands on my waist n i strt ridn real slow @ first but thn |

| (05:53:58 PM EST) Participant says to Max (SMS): (HYSEX, HYKISS)* So i say o really? Thn give me tht dick right nw so u say give me tht pussy n i climb 2 yo side n sit facin u thn strt kissin u while i take off yo shirt n |

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Adams HE, Bernat JA, Luscher KA. Borderline personality disorder: An overview. In: Sutker PB, Adams HE, Sutker PB, Adams HE, editors. Comprehensive handbook of psychopathology. 3. New York, NY, US: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers; 2001. pp. 491–507. [Google Scholar]

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders; DSM-5. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Angelides S. ‘Technology, hormones, and stupidity’: The affective politics of teenage sexting. Sexualities. 2013;16(5–6):665–689. doi: 10.1177/1363460713487289. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Benotsch EG, Snipes DJ, Martin AM, Bull SS. Sexting, substance use, and sexual risk behavior in young adults. Journal Of Adolescent Health. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Block MJ, Westen D, Ludolph P, Wixom J, Jackson A. Distinguishing female borderline adolescents from normal and other disturbed female adolescents. Psychiatry. 1991;54:89–103. doi: 10.1080/00332747.1991.11024535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown JD, Keller S, Stern S. Sex, sexuality, and sexed: Adolescents and the media. The Prevention Researcher. 2009;16(4) tpronline.org retrieved September 2, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Byers ES. Beyond the birds and the bees and was it good for you?: Thirty years of research on sexual communication. Canadian Psychology. 2011;52(1):20–28. [Google Scholar]

- Buhrmester DP. Romantic development: Is early involvement good or bad?. Poster presented at the biennial meeting of the Society for Research on Child Development; Minneapolis, MN. 2001. Apr, [Google Scholar]

- Chalfen R. Commentary sexting as adolescent social communication. Journal of Children and Media. 2010;4(3):350–354. doi: 10.1080/17482798.2010.486144. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chanen AM, Jovev M, Djaja D, McDougall E, Yuen H, Rawlings D, Jackson HJ. Screening for borderline personality disorder in outpatient youth. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2008;22(4):353–364. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2008.22.4.353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi H, Van Ouytsel J, Temple JR. Association between sexting and sexual coercion among female adolescents. Journal Of Adolescence. 2016;53:164–168. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2016.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Champion AR, Pedersen CL. Investigating differences between sexters and non-sexters on attitudes, subjective norms, and risky sexual behaviours. Canadian Journal Of Human Sexuality. 2015;24(3):205–214. [Google Scholar]

- Connolly J, Craig W, Goldberg A, Pepler D. Mixed-gender groups, dating, and romantic relationships in early adolescence. Journal of Research on Adolescence (Blackwell Publishing Limited) 2004;14(2):185–207. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2004.01402003.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cox Communications. Teen online & wireless safety survey: Cyberbullying, sexting, and parental controls. Atlanta, GA: Cox Communications, National Center for Missing & Exploited Children; 2009. May, Retrieved from http://ww2.cox.com/wcm/en/aboutus/datasheet/sandiego/internetsafety.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Crick NR, Woods K, Murray-Close D, Han G. The development of borderline personality disorder: Current progress and future directions. In: Freeman A, Reinecke MA, editors. Personality disorders in childhood and adolescence. Hoboken, NJ US: John Wiley & Sons Inc; 2007. pp. 341–384. [Google Scholar]

- Dake JA, Price JH, Maziarz L, Ward B. Prevalence and Correlates of Sexting Behavior in Adolescents. American Journal of Sexuality Education. 2012;7(1):1–15. doi: 10.1080/15546128.2012.650959. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- DeLamater J, Friedrich W. Human sexual development. Journal of Sex Research. 2002;39(1):10–14. doi: 10.1080/00224490209552113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delevi R, Weisskirch RS. Personality factors as predictors of sexting. Computers In Human Behavior. 2013;29(6):2589–2594. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2013.06.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Devitt K, Roker D. The Role of Mobile Phones in Family Communication. Children & Society. 2009;23(3):189–202. doi: 10.1111/j.1099-0860.2008.00166.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dowdell EB, Burgess AW, Flores J. Online Social Networking Patterns Among Adolescents, Young Adults, and Sexual Offenders. American Journal of Nursing. 2011;111(7):28–38. doi: 10.1097/01.NAJ.0000399310.83160.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drouin M, Landgraff C. Texting, sexting, and attachment in college students’ romantic relationships. Computers in Human Behavior. 2012;28(2):444–449. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2011.10.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Drouin M, Ross J, Tobin E. Sexting: A new, digital vehicle for intimate partner aggression? Computers In Human Behavior. 2015;50:197–204. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2015.04.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Englander EK. Coerced sexting and revenge porn among teens. Bullying, Teen Aggression and Social Media. 2015;1(2):19–21. [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson C. Sexting behaviors among young Hispanic women: incidence and association with other high-risk sexual behaviors. The Psychiatric Quarterly. 2011;82(3):239–243. doi: 10.1007/s11126-010-9165-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleschler-Peskin M, Markham CM, Addy RC, Shegog R, Thiel M, Tortolero SR. Prevalence and patterns of sexting among ethnic minority urban high school students. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking. 2013;16(6):454–459. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2012.0452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geiger TC, Crick NR. A developmental psychopathology perspective on vulnerability to personality disorders. In: Ingram RE, Price JM, editors. Vulnerability to psychopathology: Risk across the lifespan. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2001. pp. 57–102. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon-Messer D, Bauermeister J, Grodzinski A, Zimmerman M. Sexting among young adults. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunderson J. Disturbed relationships as a phenotype for borderline personality disorder. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 2007;164(11):1637–1640. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.07071125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris KM, Halpern CT, Whitsel E, Hussey J, Tabor J, Entzel P, Udry JR. The National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health: Research Design. 2009 Retrieved from http://www.cpc.unc.edu/projects/addhealth/design.

- Katzman D. Sexting: Keeping teens safe and responsible in a technologically savvy world. Pediatrics & Child Health. 2010;15(1):41–45. doi: 10.1093/pch/15.1.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977;33(1):159–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenhart A. Teens and sexting: How and why minor teens are sending sexually suggestive nude or nearly nude images via text messaging. 2009 Retrieved from http://www.pewinternet.org/*/media//Files/Reports/2009/PIP_Teens_and_Sexting.pdf.

- Lenhart A. Teens, smartphones, & texting: Texting volume is up while the frequency of voice calling is down. About one in four teens say they own smartphones. 2012 Retrieved from http://pewinternet.org/~/media//Files/Reports/2012/PIP_Teens_Smartphones_and_Texting.pdf.

- Mitchell KJ, Finkelhor D, Jones LM, Wolak J. Prevalence and characteristics of youth sexting: a national study. Pediatrics. 2012;129(1):13–20. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-1730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]