Abstract

Interactions between Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeat (CRISPR) RNAs and CRISPR-associated (Cas) proteins form an RNA-guided adaptive immune system in prokaryotes. The adaptive immune system utilizes segments of the genetic material of invasive foreign elements in the CRISPR locus. The loci are transcribed and processed to produce small CRISPR RNAs (crRNAs), with degradation of invading genetic material directed by a combination of complementarity between RNA and DNA and in some cases recognition of adjacent motifs called PAMs (Protospacer Adjacent Motifs). Here we describe a general, high-throughput procedure to test the efficacy of thousands of targets, applying this to the Escherichia coli type I-E Cascade (CRISPR-associated complex for antiviral defense) system. These studies were followed with reciprocal experiments in which the consequence of CRISPR activity was survival in the presence of a lytic phage. From the combined analysis of the Cascade system, we found that (i) type I-E Cascade PAM recognition is more expansive than previously reported, with at least 22 distinct PAMs, with many of the noncanonical PAMs having CRISPR-interference abilities similar to the canonical PAMs; (ii) PAM positioning appears precise, with no evidence for tolerance to PAM slippage in interference; and (iii) while increased guanine-cytosine (GC) content in the spacer is associated with higher CRISPR-interference efficiency, high GC content (>62.5%) decreases CRISPR-interference efficiency. Our findings provide a comprehensive functional profile of Cascade type I-E interference requirements and a method to assay spacer efficacy that can be applied to other CRISPR-Cas systems.

Keywords: CRISPR-Cas, CRISPR-interference, Cascade, guide efficacy, phage

CRISPR-Cas (Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats and CRISPR-associated proteins) are adaptive immune systems in prokaryotes (Bhaya et al. 2011; Terns and Terns 2011; Wiedenheft et al. 2012; Shmakov et al. 2015). There are six types of CRISPR-Cas immune systems (hereafter abbreviated to CRISPR-Cas): type I-VI. These systems rely on a mechanism where captured invading genetic material from bacteriophages, plasmids, or conjugative elements is recognized, processed, and copied between repeats in the CRISPR loci as a spacer (Barrangou et al. 2007; Datsenko et al. 2012; Yosef et al. 2012). The CRISPR spacers are expressed as long transcripts that are processed by Cas proteins either with or without other endogenous proteins to produce small guide RNAs (gRNAs) or CRISPR RNAs (crRNAs) (Brouns et al. 2008; Carte et al. 2008; Haurwitz et al. 2010; Deltcheva et al. 2011; Hatoum-Aslan et al. 2011; Nam et al. 2012). If enough complementarity exists between the target and the crRNA, the Cas proteins cleave the target thus conferring immunity from the invading foreign genetic element (Hale et al. 2009; Jore et al. 2011; Wiedenheft et al. 2011; Jinek et al. 2012). In addition to utilizing complementarity between crRNA and the target, CRISPR-Cas systems can use a protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) for target/nontarget discrimination during interference (Deveau et al. 2008; Mojica et al. 2009; Marraffini and Sontheimer 2010; Semenova et al. 2011; Westra et al. 2012; Sternberg SH et al. 2014).

The Escherichia coli type I-E Cascade system is guided by a 61 nt crRNA and is made up of five different Cas proteins [Cse1 (1); Cse2 (2), Cas7 (6), Cas5 (1), Cas6e (1)] (Jore et al. 2011). The Cascade system recognizes a wide variety of PAM sequences with varying degrees of efficacy. Several PAM sequences found in the initial studies of Cascade are termed “canonical PAMs” (5′-AAG, AGG, ATG, GAG-3′), while an additional set described in later studies are termed “noncanonical PAMs” (5′-CAG, GTG, TAA, TGG, AAA, AAC, AAT, ATA, TAG, TTG-3′) (Westra et al. 2012, 2013; Mulepati and Bailey 2013; Fineran et al. 2014; Hochstrasser et al. 2014; Caliando and Voigt 2015; Leenay et al. 2016). Type I systems are found in various industrially and medically relevant microbial strains (e.g., E. coli, Streptococcus thermophilus, Clostridium autoethanogenum, and Acinetobacter baumannii) (Grissa et al. 2007). Various versatile technological tools have been developed utilizing the Cascade type I-E CRISPR-Cas system. Efficient genome editing and gene repression has been demonstrated in E. coli (Luo et al. 2015; Rath et al. 2015; Chang et al. 2016). Furthermore, the Cascade system has been shown to be applicable in gene editing and transcription repression when delivered in different species of bacteria (Box et al. 2015; Rath et al. 2015). Beyond its value in bacterial genome engineering, the Cascade type I-E system has been a uniquely applicable tool for bacteriophage genome editing (Kiro et al. 2014; Box et al. 2015).

To further our understanding of the specificity of the Cascade system, we developed a high-throughput in vivo method in which a large population of otherwise unrelated crRNA sequences could be assayed in a single experiment. Previous high-throughput methods of crRNA characterization include PAM-SCANR (Leenay et al. 2016) and MS2 screening (Abudayyeh et al. 2016). The PAM-SCANR method utilizes gene repression as a basis assaying varying PAMs (“NNNN”) while holding the target region constant. The PAM-SCANR method offers flexibility in exploring the four bases adjacent to the target region, but is restricted to querying a single target. The MS2 phage screening method uses the expression of a CRISPR-Cas system (C2c2) with a library of spacers tiling a MS2 phage genome. The bacterial strain containing the MS2 spacer library is challenged with MS2 phage and after a period of infection, the remaining crRNAs are sequenced (Abudayyeh et al. 2016). The MS2 phage screening method can be used to assay crRNA function by varying the target and the PAM adjacent flanking region. However, this method requires a characterized lytic phage for the host CRISPR-Cas system in question. In devising a high-throughput assay we chose to assay CRISPR-interference with multiple heterogeneous crRNAs with varying sequence features derived from the λ bacteriophage genome. For a summary of PAMs found in previous studies for the Cascade type I-E system see Supplemental Material, Table S1 in File S3. In contrast to previous methods, our assay utilizes self-targeting/bacterial suicide with a Cascade complex that harbors a functional Cas3 nuclease. The advantage of this method is the ability to test CRISPR-interference with thousands of crRNAs with diverse sequence features before and after the controlled induction of the CRISPR-Cas system. In addition, the results produced from our analysis can be validated via phage infection assays.

This method allows for a detailed investigation of interference requirements and presents a high-throughput way of assaying spacer efficacy that can be adapted for other CRISPR-Cas systems. Our approach revealed extensive PAM promiscuity, with about a third of the 64 possible PAMs having the ability to induce interference. We found that PAM identity was the predominant predictive feature of crRNA CRISPR-interference. We found no evidence of PAM slippage contributing to increased crRNA efficacy for CRISPR-interference but did find evidence for contribution of the base proximal to the PAM (elongated PAM). In addition, moderate GC content increased crRNA CRISPR-interference, while crRNAs with UUU exhibited decreased CRISPR-interference. Finally, low-throughput assays for phage infection in the presence of select crRNAs showed strong concordance with the predicted crRNA CRISPR-interference efficiency from our high-throughput assays, providing additional experimental validation for our approach.

Materials and Methods

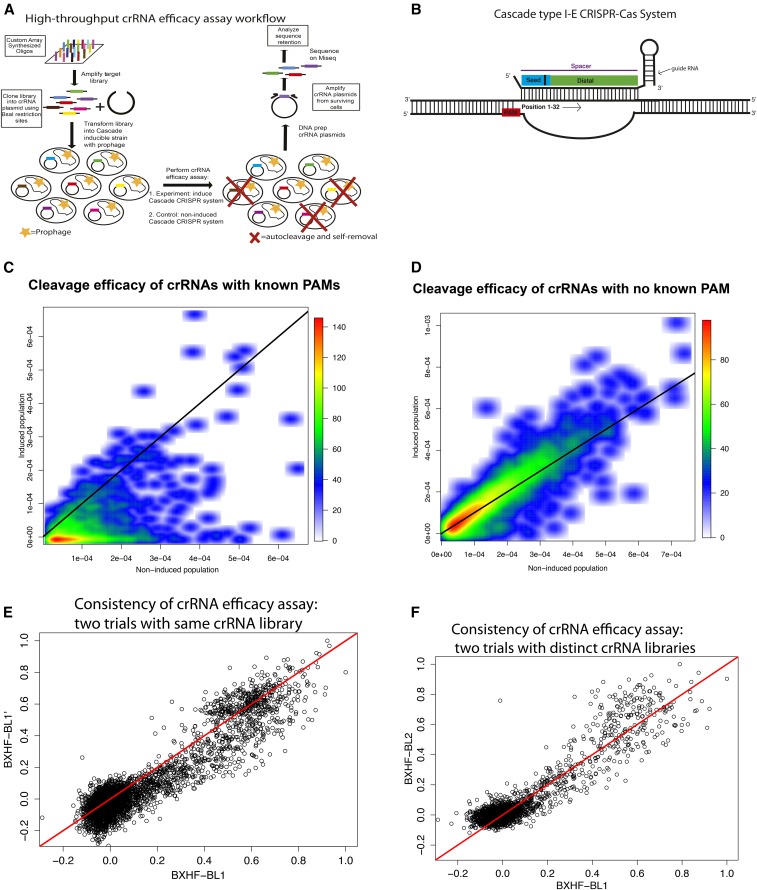

To test the crRNA efficacy of the Cascade type I-E system in a high-throughput and nonbiased way, we tested a selection of crRNAs tiling a target region with a 32-bp window and assayed for CRISPR-interference. The overall design of the in vivo assay includes: (1) integrating the target region (λ prophage) into the ACT-01strain [an E. coli strain with an inducible Cascade system (Caliando and Voigt 2015)], (2) cloning a crRNA library targeting the region into a crRNA expression vector, (3) transforming the crRNA library into the bacterial strain from step 1, (4) performing a growth assay in induced and noninduced conditions, (5) amplifying and DNA sequencing the crRNA templates to determine the representation of each crRNA (percent of reads exactly matching to the crRNA) with and without induction of the CRISPR system, and (6) calculating a retention score for each crRNA based on the log ratio of induced to noninduced representations (Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

Cascade type I-E crRNA efficacy assay. (A) The Cascade spacer/crRNA efficacy assay involves the following steps: (1) synthesis of a spacer/crRNA library tiling the target region (l genome) via pooled oligo synthesis, (2) cloning of the library into a crRNA expression vector (pPD207.846), (3) transformation of the spacer/crRNA library into a bacterial strain with an inducible Cascade CRISPR-Cas system and the target region integrated [ACT-01(Rts) strain], (4) growth assays of the bacterial library with induced and noninduced Cascade conditions, (v) DNA extraction of crRNA plasmid pools, (5) amplification of crRNA regions of plasmid pools with adapters for sequencing, and (6) sequencing on MiSeq high-throughput sequencing platform. (B) Graphical depiction of the crRNA and DNA complex. The colors indicate the PAM (red), seed (blue), and distal (green) regions of the target–crRNA complex. The base closest to the PAM is designated as position 1, so that the base farthest from the PAM is position 32. (C) Density plot of crRNAs’ representation before and after induction of the Cascade CRISPR-Cas system for all crRNAs with a canonical or known functional PAM. The crRNAs that fall along the diagonal have similar representations before and after the induction of the Cascade system. crRNAs that fall below the diagonal are crRNAs that have been removed due to auto-CRISPR-interference while crRNAs that are above or on the diagonal are crRNAs that do not significantly cleave. (D) Density plot of crRNAs’ representation before and after induction of the Cascade CRISPR-Cas system for crRNAs with no known functional PAM. (E) Scatter plot of normalized retention scores of shared crRNAs between replicates of the BXHF-BL1 Cascade spacer library assay results (BXHF-BL1 and BXHF-BL1′). For each library, all crRNAs are divided by the minimum score to scale all retentions from 0 to 1 for plotting. The retentions of each crRNA are strongly concordant between replicates (Pearson correlation = 0.929). (F) Scatter plot of normalized retention scores of shared crRNAs between distinct Cascade spacer library assay results (BXHF-BL1 and BXHF-BL2), plotted using same method as D. Once again, there is strong concordance between assays (Pearson correlation = 0.926).

In describing the assay, we note that the target of our library of crRNAs was a phage genome. This assay can work with any target sequence whether it is an integrated or endogenous sequence. However, it is important to note that utilizing self-targeting may provide a slightly different interference profile compared to using phage or plasmid targeting (Maniv et al. 2016).

Cascade bacterial library strain construction

The inducible Cascade bacterial strain ACT-01 from Caliando and Voigt (2015) originally lacks the target region (λ prophage). To create an ACT-01 derivative with the λ prophage, the ACT-01 strain was grown overnight in liquid enrichment media (LEM) media (see “Protocols” section in Supplemental Materials for recipes). In choosing a λ prophage for these studies, we chose a temperature-sensitive mutant in the phage R gene ((Campbell and Del Campillo-Campbell 1963) the λ-Rts phage was a generous gift from Allan Campbell). A bacterial lawn was made with 100 μl of the overnight culture mixed with 5 ml of 0.7% top agar and spread on an LB plate. About 50 μl of λ-Rts phage was spotted on the bacterial lawn. The plate was left to incubate at 27° overnight. The resulting turbid plaques were streaked out on LB plates. The isolated bacterial strains were tested for the presence of the prophage via inability to replaque with the λ-Rts phage. The ACT-01 strain from (Caliando and Voigt 2015) with the λ-Rts prophage integrated is referred to as the ACT-01(Rts) strain.

Construction of crRNA plasmid library

The plasmid used to express the Cascade crRNA was constructed by redesigning the wild-type E. coli Cascade CRISPR loci. A synthetic DNA fragment of the Cascade CRISPR loci was designed with restriction enzyme sites (BsaI-XhoI-BsaI) replacing the first spacer. The fragment consisted of the CRISPR leader followed by a CRISPR repeat, BsaI-XhoI-BsaI restriction sites, followed by another CRISPR repeat followed by ∼300 bp of endogenous sequence of the end of the CRISPR locus. This new cloning CRISPR loci fragment was inserted next to an arabinose promoter (pPD207.846). The BsaI sites provide an asymmetric and modular insertion site for incorporating libraries of potential crRNA sequences. A unique XhoI site separating the two BsaI sites allows double-digested vector (BsaI+XhoI) to capture inserts with very low religation background. Figure S1 in File S3 depicts a graphical schematic of the crRNA expression vector design.

Large sets of synthetic oligos were obtained through massively parallel synthesis (Custom Array, Bothell, WA), tiling the λ phage genome at 32-nt increments. These were designed for amplification with a constant primer pair AF-BXHF-42 and AF-BXHF-43 (see Table S2 in File S3 for sequences) and gel purified using the Qiagen gel extraction kit. The resulting double-stranded DNA was digested with BsaI enzyme and extracted using phenol + phenol/chloroform + ethanol extraction. The final digested double-stranded fragments are appropriate for ligation into linearized pPD207.846 and ligated with T4 ligase overnight. Figure S2 in File S3 depicts an example oligo sequence through the library construction process. The ligation products were transformed into TOP10 DH5α library competent cells and grown on plates. The transformed colonies were allowed to grow at 37° overnight and subsequently incubated for 2 days at 30°. After the 2-day incubation, ∼20,000 colonies were scraped off plates and plasmid DNA was purified using the Qiagen Midi plasmid prep kit.

The crRNA plasmid library was transformed into the ACT-01(Rts) bacterial strain via electroporation (Bio-Rad Gene Pulser Xcell). Transformed bacterial cells were allowed to recover for an hour at 37° and plated. The bacteria were allowed to grow overnight at 37° and were then moved to 30° for a 2-day incubation. Finally, ∼20,000 ACT-01(Rts) bacterial colonies harboring the crRNA plasmids were scraped off plates and pooled to produce the bacterial spacer library. In this study, two distinct libraries were created and used for experiments: BXHF-BL1 and BXHF-BL2. The bacterial crRNA library was washed with fresh 2×TY media and resuspended in 30 ml of 50% glycerol solution + 0.5% glucose + Kanamycin (50 μg/ml) and stored at −80° for experimental assays.

Cascade spacer in vivo CRISPR-interference assay

About 5–10 μl of frozen spacer bacterial library were inoculated in 25 ml of 2×TY media + Kanamycin + 0.5% glucose and allowed to grow to OD600 of 0.1–0.2 at 37° with agitation. After recovery, aliquots of 100 μl of cells were spun down and the supernatant discarded. The cells were used to inoculate new cultures with either arabinose-induced (Cascade+) or noninduced conditions (Cascade−). The noninduced cultures were grown in 2×TY + Kanamycin + 0.5% glucose. The induced cultures were grown in 2×TY + Kanamycin + 2 mM arabinose (Caliando and Voigt 2015). The cultures were grown at 37° with agitation for 9–12 divisions. All cultures were passaged before stationary phase (OD600 0.7–0.8). After 9–12 divisions, the induced bacterial cultures showed a lag in growth compared to the noninduced cultures (difference of about OD600 0.25–0.3). Once the cultures displayed a growth difference between the induced and noninduced conditions, the bacterial cultures were diluted 1/5000–1/10,000 and grown at 20° with agitation overnight (∼6–10 divisions). Aliquots of 2 ml from each experimental noninduced and induced population were taken at different time points and plasmid DNA prepped (protocol can be found in the “Protocols” section in the Supplemental Materials). Various time points were taken throughout the growth assay, and retention profiles of crRNAs can be found in Figure S3 in File S3. The number of divisions for each library differs but ranges from 15 to 20 divisions (Figure S3 in File S3).

Sequencing adapters were added onto the DNA-prepared plasmids via a two-step PCR. A first round of amplification involved short primers AF-BXHF-73 and AF-BXHF-367 (10–12 cycles) (see Table S2 in File S3). The first round of amplification consists of primers with seven degenerate nucleotides that are necessary to add diversity for high-throughput sequencing. A second round of amplification attached longer primers with index sequences (8–10 cycles). The index sequences used are derived from Illumina Truseq HT Kit [forward primers: AF-KLA- (67–74) and reverse primers: AF-KLA-(124–135); Table S2 in File S3]. Primer sequences can be found in Table S2 in File S3 and amplification information can be found in the “Protocols” section of the Supplemental Materials. All PCR amplifications were performed using Phusion polymerase with GC buffer.

The E. coli MG1655 strain carries a number of cryptic prophage in its chromosome including several fragments matching λ sequence (Blattner et al. 1997; Casjens 2003). To prevent crRNAs with complementarity to the E. coli genome from confounding the analysis, all crRNAs were aligned to the E. coli genome with Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST) using default parameters for short read alignment. All crRNAs with alignment e-values ≤0.001 were removed from analysis. The control set of crRNAs used for comparison consists of crRNAs aligned to the E. coli and λ-Rts genome, and only crRNAs with e-values >0.001 were used for the control set. In addition, the Cascade spacer assay was performed on libraries in bacteria without the λ-Rts prophage target in the genome. Minimal off target effects were observed for the control experiments (Figure S4 in File S3).

A table of all Cascade in vivo high-throughput experiments, experimental conditions, and corresponding data information can be found in Table S3 in File S3.

As noted also by Beloglazova et al. (2015), we observed a small number of highly structured crRNAs with strong Cascade PAMs but little or no ability to cause interference in vivo (Table S4 in File S3). Not all RNAs with strong secondary structure predictions lose their crRNA capabilities and we have not done extensive follow-up to determine either structural determinants for the inhibition or which step of the process has been affected.

Calculation of crRNA retention scores

A log-retention score for each crRNA was calculated by quantifying the representation of each sequence before and after the induction of the Cascade CRISPR-Cas system. The number of assessed crRNAs in each library can vary depending on sequencing depth. Sequences with n ≥ 50 counts and matching the λ-Rts prophage in the noninduced control were considered for the analysis. Each library also contains a control population of crRNAs that did not map either to the λ or E. coli genome (aligned with BLAST with e-values >0.001). The median retention of the control population was subtracted from each calculated retention score for normalization.

For each sequence:

Representation in control: (number of counts without induction of Cascade system + 1)/(total size of library + 1)

Representation in experiment: (number of counts with induction of Cascade system + 1)/(total size of library + 1)

Retention score: (log2(Representation in induced experiment/Representation in noninduction control))-median (retentions of control crRNAs)

Sequencing of λ-Rts bacteriophage

The integrated λ-Rts phage was sequenced using Illumina Nextera reagents. The crRNAs considered in experiments are required to exactly match the λ-Rts genome. The sequenced genome can be found in the attached Supplemental Materials.

Plaque assays

To validate the results of the Cascade in vivo assay, 22 crRNAs were selected from the spacer library screens and plaque assays were performed with a lytic λ phage (a λ∆cI variant; a generous gift from Gerard Koudelka). The selected crRNAs were cloned into pPD207.846 and transformed into the ACT-01 bacterial strain lacking λ-Rts prophage (Caliando and Voigt 2015). A standard phage plaque assay protocol was used to test the 22 candidate crRNAs.

We note that different metrics can be (and have been) used to assess phage resistance (total yield of infectious phage particles following infection, number of plaques on a potentially resistant host, relative plaque size and morphology, etc.). Additionally, the efficacy of CRISPR-Cas systems is dependent on the nature of the target (e.g., phage vs. plasmid; Maniv et al. 2016). In assessing infectivity by phage, we infected the potentially resistant host and observed both plaque size (smaller vs. larger plaques) and plaque number. As the most directly quantitated value, we use plaque numbers to evaluate phage resistance. Corroborating the plaque counts, we observed dramatic differences in plaque size: plaques were universally much smaller on bacteria that carried effective crRNAs. Given the combined observations of smaller and fewer plaques, we note that plaque number provides an evaluative metric for resistance, albeit not necessarily a linear one.

Data availability

All high-throughput retention assay data are deposited at the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) Archive (Study Accession PRJNA388730 (SRP108442)). Provisional “working model” sequence assemblies for plasmid pPD207.846 (File S1) and for the assembled λ-Rts genome (File S2) (Campbell and Del Campillo-Campbell 1963) are provided with this manuscript as Supplemental Material.

Results

Design of in vivo Cascade high-throughput spacer efficacy assay

We designed the in vivo high-throughput spacer screen with the intention of assaying a large population of crRNAs with varying PAMs and sequence characteristics. To develop an assay that would meet these factors, we designed a crRNA library that targeted the λ-Rts phage genome (Campbell and Del Campillo-Campbell 1963). Sequences tiling the λ genome with a window of 32 nts were generated; 12,472 sequences were selected and synthesized via massively parallel solid phase oligo synthesis (Figure 1A). The list of ordered spacers included 5446 sequences that spanned the previously characterized canonical PAMs (5′-AAG, AGG, ATG, GAG-3′) and 7026 randomly selected sequences that did not have a canonical PAM. The oligo library was nonredundant. Table S5 lists all synthesized oligos, with additional detail in Construction of crRNA plasmid library. In this manuscript, position 1 will refer to the first base in the target region closest to the PAM and position 32 will refer to the last position of the target region (Figure 1B).

We chose to use the method of bacterial suicide/self-removal to assay spacer efficacy. In order for the spacer library to have the potential of self-removal by self-targeting, the cloned spacer library was transformed into a previously characterized bacterial strain that is recombination deficient with one copy of the Cascade CRISPR-Cas system (cas3ABCDE) on an arabinose promoter, also known as the ACT-01 strain (Caliando and Voigt 2015). An integrated λ bacteriophage (λ-Rts) (Campbell and Del Campillo-Campbell 1963) (Figure 1A) has been added to the genome through lysogeny to allow targeting by λ-derived spacer sequences. To obtain precise information on the target, we resequenced the genome of the λ-Rts used to produce the target lysogen (File S2). Successful targeting of the prophage genome by the CRISPR-Cas machinery in this system will cause an irreparable double-strand break, resulting in cell death. The induced and noninduced plasmid libraries were extracted (see Supplemental Materials for “Protocol”) and the crRNAs were amplified with sequencing indices and sequenced using the MiSeq (see Table S2 in File S3 for primers used). A retention score was calculated for each crRNA in the library based on crRNA representations before and after induction of the Cascade system (see Calculation of crRNA retention scores for details on CRISPR-interference scores). Negative retention values indicate efficient CRISPR-interference, while zero or positive values suggest lack of CRISPR-interference.

Two separately cloned and pooled bacterial crRNA libraries were tested and analyzed in this study: BXHF-BL1 and BXHF-BL2. Following subtraction of segments that fail to meet threshold criteria, failed to clone, or match the MG1655 genome (see Materials and Methods) the analyzable crRNA populations for BXHF-BL1 and BXHF-BL2 consist of a total of 6829 crRNAs, with 2374 crRNAs present in both libraries and 4455 unique. Protospacer sequences represented below a minimal count number in the uninduced (effectively CRISPR-) control were omitted from the analysis, as were any crRNAs with detectable matches in the E. coli genome (see Cascade spacer in vivo CRISPR-interference assay for details on excluded crRNAs). When examined with a prophage target and with and without Cascade activity, the two libraries both begin with a unimodal distribution of retention scores and later progress to a bimodal distribution of retention scores (Figure S3 in File S3); in the absence of prophage, no evident targeting by the selected crRNAs was observed (Figure S4 in File S3). Figure 1C shows the density of representations of crRNAs with canonical or known PAMs before (x axis) and after (y axis) induction of the Cascade system in the presence of prophage target. The crRNAs that are efficiently removed after the induction of the Cascade system will fall below the diagonal. Figure 1D shows a similar plot to Figure 1C but for crRNAs without any known PAM. As expected, crRNAs with known functional PAMs fall below the diagonal line and the majority of crRNAs with no known PAM fall on the diagonal (Figure 1, C and D). The assay is highly reproducible; sequences shared between the same library assayed at different times (BXHF-BL1 vs. BXHF-BL1′) (Pearson correlation: 0.929; P-value <2.2e−16) and distinct libraries (BXHF-BL1 vs. BXHF-BL2) (Pearson correlation: 0.926; P-value <2.2e−16) have consistent retention scores (Figure 1, E and F). We observed comparable results from the two libraries; the main figures in this manuscript will present results for BXHF-BL1, while additional data from library BXHF-BL2 will be provided in the Supplemental Materials (File S3).

PAM recognition and efficacy of crRNA

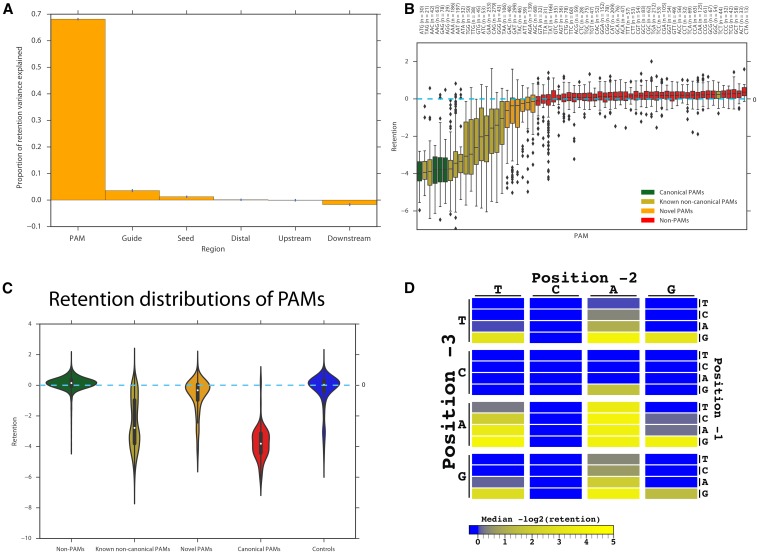

We hypothesized that features of the crRNA sequence, PAM, and target locus determined differences in retention between crRNAs. We trained gradient boosting regression models from Scikit-learn (Pedregosa et al. 2011) (version 0.17.1 with default settings) to predict retention from (a) the PAM, (b) the crRNA/target sequence, (c) the 17 bp upstream of the PAM, and (d) the 20 bp downstream of the crRNA site. The input features provided to the model were (i) base compositions at each position (binary features which are equal to 1 if the input sequence has a particular base at a particular position, and 0 otherwise), (ii) 1–4-mer counts (or 1–3-mer counts in the case of the PAM), and (iii) GC content. Gradient boosting regression is a supervised machine learning method that has been previously used in genomics (Jagadeesh et al. 2016). Unlike univariate statistical tests, gradient boosting can learn to predict a label (in this study: retention) from multiple features (in this study: various aspects of the crRNA and target sequence) simultaneously, while accounting for correlations between the features (Pedregosa et al. 2011). On a held-out test set comprising 20% of the data, models trained on the PAM explained 69.6 ± 0.05% of the variance in retention between crRNAs, while models trained on the crRNA sequence explained 3 ± 1% of the variance, with the predictive accuracy primarily coming from the seed region (1–6 and 8 bp from the PAM) (Figure 2A). This suggests crRNA effectiveness for a crRNA perfectly matched to its target is primarily driven by PAM identity, with a smaller contribution from crRNA and target sequence composition. No consistent contribution to efficacy based on upstream or downstream sequence was observed in these assays.

Figure 2.

Cascade type I-E PAM recognition. (A) Percent of variance in retention (r2) explained by gradient boosting regression models trained on various regions of the crRNA sequence and target locus. The r2 values shown are means over 10 gradient boosting trials with different random seeds; the y axis is the percent variance explained by the model and error bars denote the SEM. (B) Median retention of crRNAs with each PAM, with bootstrapped estimates of the SD of the median retention. (C) Violin plots (Hintze and Nelson 1998) of the distributions of retentions for canonical, known noncanonical, novel, insufficient cleaving PAMs, and controls (crRNAs that do not map to λ-Rts or the E. coli genome). (D) Heat map of −log2 [median(retention)] for all possible PAMs. A nonfunctional PAM would have a positive or zero −log2 [median(retention)] score (strong blue). A functional PAM would have a negative −log2 [median(retention)] with CRISPR-interference efficiency denoted by successively weaker shades of blue or with yellow as CRISPR-interference efficiency increases.

We used internal control data from nontargeting control crRNAs (i.e., crRNAs not matching the E. coli or prophage genome; see Cascade spacer in vivo CRISPR-interference assay for more details on control crRNAs) as a reference in obtaining a distribution of retention scores for spacers corresponding to each of the 64 possible PAM triplets (Figure 2B). Using the Mann–Whitney (MW) test, a total of 22 PAMs were associated with significantly lowered retention scores compared to the control crRNAs at 10% false discovery rate (FDR) (one-tailed MW test), including the four canonical PAMs 5′-AAG, AGG, ATG, and GAG-3′ (Westra et al. 2012),13 of the 14 previously characterized noncanonical PAMs (Westra et al. 2013; Fineran et al. 2014; Caliando and Voigt 2015; Leenay et al. 2016), and four novel PAMs: 5′-GAC, GAT, ATT, and AGC-3′ (the last two of which are significant at 10% FDR but not after Bonferroni correction) (Figure S5 in File S3). Two other novel PAMs, 5′-TAC-3′ and 5′-AGA-3′, were also significant at 10% FDR but failed to replicate. The previously reported weak 5′-TCT-3′ PAM (Westra et al. 2013) showed no significant functionality in our analysis. Only nine PAMs (5′-AAG, AGG, ATG, GAG, AAA, AAC, AAT, ATA, and TAG-3′) had consistently strong CRISPR-interference across previous studies (Westra et al. 2013; Fineran et al. 2014; Caliando and Voigt 2015; Leenay et al. 2016) and our own study; we refer to these as “strong PAMs” for the remaining analysis. Our study showed strong CRISPR-interference for crRNAs with the strong PAMs and with 5′-TGG, GTG, and TTG-3′ (median retention ≤−2). The four novel PAMs are weaker than previously discovered PAMs, but still have markedly more negative retentions than non-PAMs (Figure 2C). Figure 2D shows a heat map of CRISPR-interference degree for all possible PAMs. BXHF-BL2 showed similar results compared to BXHF-BL1. Figure S6 in File S3 shows all the results for BXHF-BL2. Table S1 in File S3 summarizes the PAM findings of the present and past studies on type I-E Cascade PAMs. Of the 64 possible PAMs, about a third had significant CRISPR-interference ability, indicating that Cascade type I-E PAM recognition is more promiscuous than previous studies have indicated. As expected (Westra et al. 2010), a perfect match to the repeat locus produces a fully ineffective PAM (CCG), allowing protection of the native CRISPR array from cleavage.

The Cascade type I-E system in wild-type E. coli is inhibited in native conditions and manipulation has been required to show functional activity (Westra et al. 2010). Previous studies have demonstrated that PAM recognition is influenced by the abundance of interference machinery with higher expression levels shown to expand effective interference (Karvelis et al. 2015; Xie et al. 2015; Hayes et al. 2016). In our studies, we utilize a synthetic promoter previously used to characterize PAM recognition for Cascade with an independent method (Caliando and Voigt 2015). Our findings corroborate the PAMs found by Caliando and Voigt (2015), in addition to identifying novel weak PAMs.

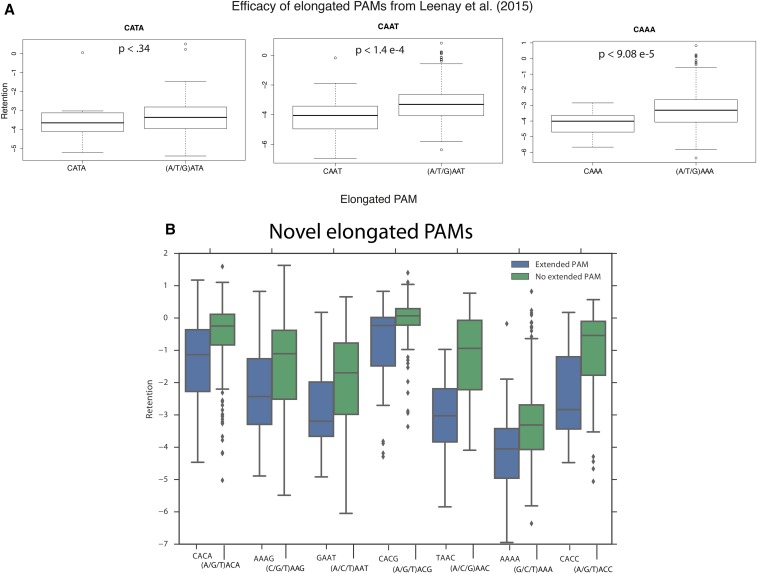

PAM adjacent sequence effects on CRISPR-interference

Some CRISPR-Cas systems are known to have PAM sequences that extend beyond the three-base window analyzed above (Leenay et al. 2016). While we did not observe strong effects for individual nucleotides outside the three-base protospacer-proximal region, at least one such influence was evident from the data. We confirm two of the three elongated PAMs found in a previous study (Leenay et al. 2016). We found that AAT and AAA exhibited lower retention when a C is in the −4 position, compared to other bases [P-value <1.4 e−4 (n = 41 vs. 158) and P-value <9.08 e−5 (n = 33 vs. 158), respectively, one-tailed MW test] (Figure 3A). Although CATA exhibited a trend toward lower retention compared to GATA/TATA/AATA, we did not have sufficient power to call significance (one-tailed MW test: P-value <0.34, n = 11 vs. 22). Examining all possible combinations of PAM and upstream base for differential retention relative to other upstream bases with each PAM, we found seven significant associations after Bonferroni correction (Figure 3B and Table S6 in File S3). These results are replicated in the second library BXHL-BL2 (Figure S7 in File S3).

Figure 3.

Cascade type I-E elongated PAM analysis. (A) Box plots of retentions for crRNAs with previously characterized elongated PAMs (5′-CATA, CAAT, CAAA-3′) (Leenay et al. 2016). (B) Box plots of retentions for crRNAs with novel elongated PAMs found in this study.

Previous studies have shown evidence of PAM slippage in type I-F (Richter et al. 2014; Staals et al. 2016) and type I-E (Shmakov et al. 2014) CRISPR-Cas, whereby PAM recognition during acquisition can be shifted by 1 bp either upstream or downstream from the ordinary PAM site. We analyzed our data for evidence of this phenomenon for Cascade CRISPR-interference. We found that crRNAs with ineffective PAMs (those not detected as significant in this study) did not have significantly lower retentions when “slipped PAM” occurred. We characterize “slipped PAM” as incidences where position −4 to −2 created a strong PAM. crRNAs with “slipped PAMs” had a median retention of 0.14 (n = 759) and crRNAs without had a median retention of 0.15 (n = 2033) (P-value <0.6, one-tailed MW test). We observed a small, significant effect for the slipped PAM site at the −2 to +1 position relative to the crRNA, 1 bp downstream (median retention 0.13 vs. 0.17, n = 1227 vs. 1565, P-value <0.04), but this did not replicate in BXHF-BL2. We were thus unable to detect evidence of PAM slippage effects on CRISPR-interference in the Cascade type I-E system.

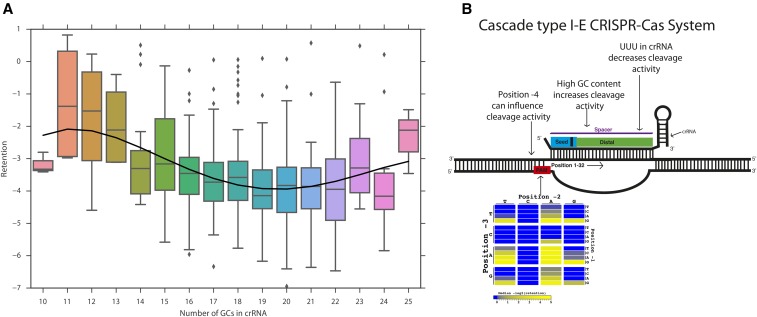

GC content effect on crRNA efficacy

We next considered which other features of the crRNA were associated with lower retention. crRNAs with high GC content tend to be more effective (Spearman correlation −0.19, P-value <5e−7), as previously observed for Cas9 from a type II CRISPR-Cas system. However, extreme GC content, whether low or high, has been reported to be harmful to Cas9 efficiency (Ren et al. 2014; Wang et al. 2014). To investigate whether extreme GC content affects the Cascade type I-E system similarly, we examined the relationship between GC content and retention for the spacers in our library (Figure 4A and Figure S8 in File S3). We found an increase in CRISPR-interference for crRNAs with 13–20 GCs (40.6–62.5% GC content). However, crRNAs with >20 GCs (>62.5%) had reduced CRISPR-interference, similar to the GC content threshold reported for Cas9 (Wang et al. 2014). In addition, the data were fitted on cubic and quadratic models; both models show similar decrease in retention until >62.5%. Overall, the results suggest that a GC content of ∼62.5% is optimal for crRNA activity.

Figure 4.

Cascade-type I-E GC content analysis. (A) Box plots of retention for crRNAs in various GC content bins, with a fourth-degree polynomial fit from the Numpy package (van der Walt et al. 2011). (B) Summary of recognition requirements based on the results found in this work (figure is drawn on a scaffold of the spacer:target interaction as diagrammed in Figure 1B).

Other sequence effects on crRNA efficacy

Previous studies of Cas9 have indicated that crRNAs containing the homopolymeric runs GGGG or UUUU, as well as UUU near the PAM, tend to be less effective (Wu et al. 2014; Wong et al. 2015). Such findings suggest potential premature crRNA transcription stoppage could cause a decrease in Cas9 efficacy. However, E. coli transcription undergoes a distinct mechanism of termination where homopolyermic runs do not cause stoppage [reviewed in Washburn and Gottesman (2015)]. However, we found that a linear regression model trained to predict retention from GC content and UUU counts achieves higher training-set accuracy than a model trained on GC content alone (prediction r2 0.06 vs. 0.04, P-value <0.002, permutation test), suggesting that the presence of UUU is harmful to crRNA effectiveness over and above its effect on GC content. This effect is replicated in BXHF-BL2: GC content alone r2 = 0.2 while GC content with UUU r2 = 0.22 with P-value <0.01. The UUU effect may also contribute to some of the ineffective crRNAs (retention >−2) with strong PAMs: four of the six guides in this category contain UUU (bootstrap P-value <0.009, bootstrap test for BXHF-BL1). A summary of the findings in this study can be found in Figure 4B.

Validation of Cascade in vivo crRNA library assay

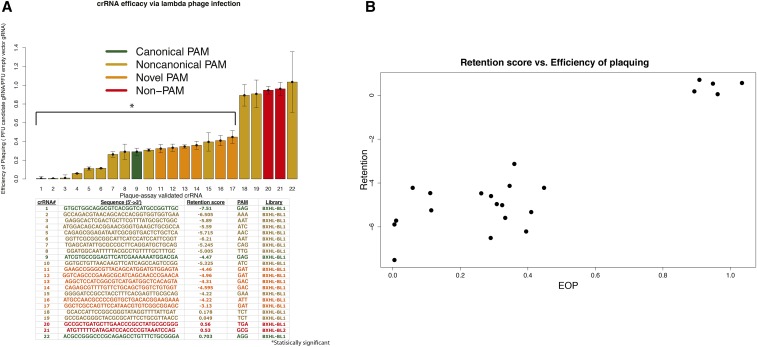

To validate the results of the Cascade in vivo crRNA library assay, plaque assays were performed to assay the ability of the crRNA of interest to confer immunity to phage infection. For these assays, 22 crRNAs were selected from the spacer library screens and cloned into the crRNA expression vector (pPD207.846) and transformed into the ACT-01 bacterial strain lacking λ-Rts prophage (Caliando and Voigt 2015). The crRNAs tested in the individual plaque assays represented a range of retention scores in the original high-throughput data and corresponded to a variety of PAMs. Figure 5A shows the sequences of tested crRNAs, the median retention recorded for each in the high-throughput assays, and ability to fight off infection by phage in independent plaque assays. Immunity in the latter assays was calculated by dividing the median plaque-forming units (PFU) of the candidate crRNA expression vector by the PFU of the empty crRNA. Ratios close to 1 indicate plaque-forming efficiency/sensitivity to phage comparable to having a nonfunctional (empty) crRNA while ratios <1 indicate resistance to plaque formation from phage infection. The 17 crRNAs with negative log-retention scores are resistant to phage infection while the five crRNAs with little or no CRISPR-interference efficacy in the high-throughput assays show little or no ability to protect the bacteria from infection (comparable to empty vector; Figure 5A). We note previously reported CRISPR immunity with similar but distinct plaque assays have shown larger effects of immunity. For details on the differences in metrics and target type (plasmid, phage, host chromosome) see Plaque assays. Figure 5B compares retention scores for each crRNA from the high-throughput assay with the plaquing efficiency from the individual infection assays (Pearson’s correlation: 0.902, P-value = 9.34e−9). The plaque assays corroborate findings of the high-throughput Cascade in vivo crRNA assay and demonstrate that our method of assaying crRNA efficacy via chromosome auto-CRISPR-interference is strongly associated with ability to confer immunity to bacteriophage.

Figure 5.

Plaque assay validation of Cascade type I-E crRNA assay. (A) Barplot of crRNA immunity to phage infection (efficiency of plaquing: EOP). A EOP ratio ∼1 indicates plaque forming efficiency/sensitivity to phage that is comparable to having a nonfunctional (empty) crRNA. A ratio <1 indicates resistance to plaque formation from phage infection. The error bars denote the SD. Each crRNA was assayed at least five times. Bottom, a chart of plaque-assay-validated crRNA sequences with associated ID number, retention, PAM, and library number. (B) Scatterplot of crRNA EOP vs. retention score (Pearson’s correlation: 0.902, P-value = 9.34e−9).

Discussion

We developed a high-throughput method to assay thousands of crRNAs and have applied this to the E. coli type I-E system Cascade. The method explores an extensive spectrum of crRNAs, with application of a gradient-boosting algorithm predicting retention based on the PAM, target, flanking, and seed regions. The availability of previous (lower throughput) analysis for Cascade allowed corroboration of major aspects of the model including the majority of characterized PAMs [both canonical and noncanonical PAMs (Westra et al. 2013; Fineran et al. 2014; Caliando and Voigt 2015; Leenay et al. 2016)], with selective single-spacer assays providing additional corroboration.

Our Cascade analysis provided evidence for substantially broader tolerance of PAMs, with approximately one third of triplets showing specific interference in Cascade CRISPR-interference. We found no evidence for tolerance to PAM slippage for Cascade CRISPR-interference but we did identify previously characterized and novel elongated PAM specificity (Leenay et al. 2016). Intriguingly, both the broad tolerance for PAMs and the elongated PAM specificity correspond with structural observations derived from a Cascade RNA:DNA complex (Hayes et al. 2016). Within the crRNA homology, we found increasing GC content was associated with high CRISPR-interference efficiency (40.6–62.5% GC), although GC content beyond 62.5% seems not to further enhance efficiency. Finally, we were able to validate our findings by testing crRNAs via phage infection and plaque assays. The predicted efficacy of crRNAs in the Cascade spacer assay was highly consistent with the ability of the crRNA to provide immunity to phage infection.

The in vivo method presented in this manuscript can provide critical information regarding optimal PAM usage and crRNA targeting in uncharacterized CRISPR-Cas systems, as well as providing a framework for interpreting repertoires of spacers acquired naturally or synthetically. While offering considerable value, extrapolations from spacer acquisition to spacer efficacy are complicated due to additional constraints related to primed acquisition and preferences of the CRISPR-Cas system to acquire spacers near Chi sites (Mojica et al. 2005; Yosef et al. 2012; Fineran et al. 2014; Levy et al. 2015; Semenova et al. 2016; Shipman et al. 2016). We expect that the capability to investigate selectivity of CRISPR-Cas systems without prior knowledge of effective spacers, and without requiring spacer acquisition, will be particularly useful both in understanding the basic biology of such systems and as a driver for technological advances.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental material is available online at www.genetics.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1534/genetics.117.202580/-/DC1.

Acknowledgments

We thank Allan Campbell, Alice Del Campillo-Campbell, Armin Dale Kaiser, Michael Bassik, Gavin Sherlock, Stuart Kim, Joe Davis, Massa Shoura, Stan Cohen, and colleagues in our laboratories for their help and suggestions. This work was supported by grants R01GM37706 (A.Z.F.) and T32GM00779 (B.X.H.F.), National Science Foundation Graduate Fellowship (B.X.H.F.), Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada PGSD3-476082-2015 (M.W.), and an Alfred Sloan Foundation Fellowship (A.K.).

Author contributions: B.X.H.F. conceived and designed the study (with A.Z.F.), developed experimental methods, performed experiments, and contextualized implications for CRISPR function; M.W. carried out machine learning and statistical analyses (with A.K.). All authors contributed to data analysis and interpretation, and to the manuscript.

Footnotes

This work is dedicated to the friendship and memory of Dr. Julia Pak. Dr. Pak was senior research scientist in the Fire laboratory at Stanford University until she lost her fight to cancer in November 2015. Her passion for mentorship and science is irreplaceable. Her strength against adversity and her kindness is an inspiration for those fortunate enough to have known her.

Communicating editor: D. I. Greenstein

Literature Cited

- Abudayyeh O. O., Gootenberg J. S., Konermann S., Joung J., Slaymaker I. M., et al. , 2016. C2c2 is a single-component programmable RNA-guided RNA-targeting CRISPR effector. Science 353: aaf5573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrangou R., Fremaux C., Deveau H., Richards M., Boyaval P., et al. , 2007. CRISPR provides acquired resistance against viruses in prokaryotes. Science 315: 1709–1712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beloglazova N., Kuznedelov K., Flick R., Datsenko K. A., Brown G., et al. , 2015. CRISPR RNA binding and DNA target recognition by purified Cascade complexes from Escherichia coli. Nucleic Acids Res. 43: 530–543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhaya D., Davison M., Barrangou R., 2011. CRISPR-Cas systems in bacteria and archaea: versatile small RNAs for adaptive defense and regulation. Annu. Rev. Genet. 45: 273–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blattner F. R., Plunkett G., Bloch C. A., Perna N. T., Burland V., et al. , 1997. The complete genome sequence of Escherichia coli K-12. Science 277: 1453–1462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Box A. M., McGuffie M. J., O’Hara B. J., Seed K. D., 2015. Functional analysis of bacteriophage immunity through a type I-E CRISPR-Cas system in vibrio cholerae and its application in bacteriophage genome engineering. J. Bacteriol. 198: 578–590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brouns S. J. J., Jore M. M., Lundgren M., Westra E. R., Slijkhuis R. J. H., et al. , 2008. Small CRISPR RNAs guide antiviral defense in prokaryotes. Science 321: 960–964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caliando B. J., Voigt C. A., 2015. Targeted DNA degradation using a CRISPR device stably carried in the host genome. Nat. Commun. 6: 6989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell A., Del Campillo-Campbell A., 1963. Mutant of λ bacteriophage producing a thermolabile endolysin. J. Bacteriol. 85: 1202–1207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carte J., Wang R., Li H., Terns R. M., Terns M. P., 2008. Cas6 is an endoribonuclease that generates guide RNAs for invader defense in prokaryotes. Genes Dev. 22: 3489–3496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casjens S., 2003. Prophages and bacterial genomics: what have we learned so far? Mol. Microbiol. 49: 277–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang Y., Su T., Qi Q., Liang Q., 2016. Easy regulation of metabolic flux in Escherichia coli using an endogenous type I-E CRISPR-Cas system. Microb. Cell Fact. 15: 195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Datsenko K. A., Pougach K., Tikhonov A., Wanner B. L., Severinov K., et al. , 2012. Molecular memory of prior infections activates the CRISPR/Cas adaptive bacterial immunity system. Nat. Commun. 3: 945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deltcheva E., Chylinski K., Sharma C. M., Gonzales K., Chao Y., et al. , 2011. CRISPR RNA maturation by trans-encoded small RNA and host factor RNase III. Nature 471: 602–607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deveau H., Barrangou R., Garneau J. E., Labonté J., Fremaux C., et al. , 2008. Phage response to CRISPR-encoded resistance in Streptococcus thermophilus. J. Bacteriol. 190: 1390–1400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fineran P. C., Gerritzen M. J. H., Suárez-Diez M., Künne T., Boekhorst J., et al. , 2014. Degenerate target sites mediate rapid primed CRISPR adaptation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 111: E1629–E1638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grissa I., Vergnaud G., Pourcel C., 2007. The CRISPRdb database and tools to display CRISPRs and to generate dictionaries of spacers and repeats. BMC Bioinformatics 8: 172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hale C. R., Zhao P., Olson S., Duff M. O., Graveley B. R., et al. , 2009. RNA-guided RNA cleavage by a CRISPR RNA-Cas protein complex. Cell 139: 945–956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatoum-Aslan A., Maniv I., Marraffini L. A., 2011. Mature clustered, regularly interspaced, short palindromic repeats RNA (crRNA) length is measured by a ruler mechanism anchored at the precursor processing site. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 108: 21218–21222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haurwitz R. E., Jinek M., Wiedenheft B., Zhou K., Doudna J. A., 2010. Sequence- and structure-specific RNA processing by a CRISPR endonuclease. Science 329: 1355–1358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes R. P., Xiao Y., Ding F., van Erp P. B. G., Rajashankar K., et al. , 2016. Structural basis for promiscuous PAM recognition in type I-E Cascade from E. coli. Nature 530: 499–503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hintze J. L., Nelson R. D., 1998. Violin plots: a box plot-density trace synergism. Am. Stat. 52: 181–184. [Google Scholar]

- Hochstrasser M. L., Taylor D. W., Bhat P., Guegler C. K., Sternberg S. H., et al. , 2014. CasA mediates Cas3-catalyzed target degradation during CRISPR RNA-guided interference. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 111: 6618–6623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jagadeesh K. A., Wenger A. M., Berger M. J., Guturu H., Stenson P. D., et al. , 2016. M-CAP eliminates a majority of variants of uncertain significance in clinical exomes at high sensitivity. Nat. Genet. 48: 1581–1586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jinek M., Chylinski K., Fonfara I., Hauer M., Doudna J. A., et al. , 2012. A programmable dual-RNA-guided DNA endonuclease in adaptive bacterial immunity. Science 337: 816–821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jore M. M., Lundgren M., van Duijn E., Bultema J. B., Westra E. R., et al. , 2011. Structural basis for CRISPR RNA-guided DNA recognition by Cascade. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 18: 529–536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karvelis T., Gasiunas G., Young J., Bigelyte G., Silanskas A., et al. , 2015. Rapid characterization of CRISPR-Cas9 protospacer adjacent motif sequence elements. Genome Biol. 16: 253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiro R., Shitrit D., Qimron U., 2014. Efficient engineering of a bacteriophage genome using the type I-E CRISPR-Cas system. RNA Biol. 11: 42–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leenay R. T., Maksimchuk K. R., Slotkowski R. A., Agrawal R. N., Gomaa A. A., et al. , 2016. Identifying and visualizing functional PAM diversity across CRISPR-Cas systems. Mol. Cell 62: 137–147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy A., Goren M. G., Yosef I., Auster O., Manor M., et al. , 2015. CRISPR adaptation biases explain preference for acquisition of foreign DNA. Nature 520: 505–510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo M. L., Mullis A. S., Leenay R. T., Beisel C. L., 2015. Repurposing endogenous type I CRISPR-Cas systems for programmable gene repression. Nucleic Acids Res. 43: 674–681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maniv I., Jiang W., Bikard D., Marraffini L. A., 2016. Impact of different target sequences on type III CRISPR-Cas immunity. J. Bacteriol. 198: 941–950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marraffini L. A., Sontheimer E. J., 2010. Self vs. non-self discrimination during CRISPR RNA-directed immunity. Nature 463: 568–571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mojica F. J. M., Diez-Villasenor C., Garcia-Martinez J., Soria E., 2005. Intervening sequences of regularly spaced prokaryotic repeats derive from foreign genetic elements. J. Mol. Evol. 60: 174–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mojica F. J. M., Díez-Villaseñor C., García-Martínez J., Almendros C., 2009. Short motif sequences determine the targets of the prokaryotic CRISPR defence system. Microbiology 155: 733–740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulepati S., Bailey S., 2013. In vitro reconstitution of an Escherichia coli RNA-guided immune system reveals unidirectional, ATP-dependent degradation of DNA target. J. Biol. Chem. 288: 22184–22192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nam K. H., Haitjema C., Liu X., Ding F., Wang H., et al. , 2012. Cas5d protein processes pre-crRNA and assembles into a cascade-like interference complex in subtype I–C/Dvulg CRISPR-Cas system. Structure 20: 1574–1584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedregosa F., Varoquaux G., Gramfort A., Michel V., Thirion B., et al. , 2011. Scikit-learn: Machine learning in Python. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 12: 2825–2830. [Google Scholar]

- Rath D., Amlinger L., Hoekzema M., Devulapally P. R., Lundgren M., 2015. Efficient programmable gene silencing by Cascade. Nucleic Acids Res. 43: 237–246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren X., Yang Z., Xu J., Sun J., Mao D., et al. , 2014. Enhanced specificity and efficiency of the CRISPR/Cas9 system with optimized sgRNA parameters in Drosophila. Cell Rep. 9: 1151–1162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter C., Dy R. L., McKenzie R. E., Watson B. N. J., Taylor C., et al. , 2014. Priming in the type I-F CRISPR-Cas system triggers strand-independent spacer acquisition, bi-directionally from the primed protospacer. Nucleic Acids Res. 42: 8516–8526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semenova E., Jore M. M., Datsenko K. A., Semenova A., Westra E. R., et al. , 2011. Interference by clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeat (CRISPR) RNA is governed by a seed sequence. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 108: 10098–10103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semenova E., Savitskaya E., Musharova O., Strotskaya A., Vorontsova D., et al. , 2016. Highly efficient primed spacer acquisition from targets destroyed by the Escherichia coli type I-E CRISPR-Cas interfering complex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 113: 7626–7631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shipman S. L., Nivala J., Macklis J. D., Church G. M., 2016. Molecular recordings by directed CRISPR spacer acquisition. Science 353: aaf1175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shmakov S., Savitskaya E., Semenova E., Logacheva M. D., Datsenko K. A., et al. , 2014. Pervasive generation of oppositely oriented spacers during CRISPR adaptation. Nucleic Acids Res. 42: 5907–5916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shmakov S., Abudayyeh O. O., Makarova K. S., Wolf Y. I., Gootenberg J. S., et al. , 2015. Discovery and functional characterization of diverse class 2 CRISPR-Cas systems. Mol. Cell 60: 385–397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staals R. H. J., Jackson S. A., Biswas A., Brouns S. J. J., Brown C. M., et al. , 2016. Interference-driven spacer acquisition is dominant over naive and primed adaptation in a native CRISPR-Cas system. Nat. Commun. 7: 12853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sternberg S. H., Redding S., Jinek M., Greene E. C., Doudna J. A., 2014. DNA interrogation by the CRISPR RNA-guided endonuclease Cas9. Nature 507: 62–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terns M. P., Terns R. M., 2011. CRISPR-based adaptive immune systems. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 14: 321–327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Walt S., Colbert S. C., Varoquaux G., 2011. The NumPy array: a structure for efficient numerical computation. Comput. Sci. Eng. 13: 22–30. [Google Scholar]

- Wang T., Wei J. J., Sabatini D. M., Lander E. S., 2014. Genetic screens in human cells using the CRISPR-Cas9 system. Science 343: 80–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Washburn R. S., Gottesman M. E., 2015. Regulation of transcription elongation and termination. Biomolecules 5: 1063–1078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westra E. R., Pul Ü., Heidrich N., Jore M. M., Lundgren M., et al. , 2010. H-NS-mediated repression of CRISPR-based immunity in Escherichia coli K12 can be relieved by the transcription activator LeuO. Mol. Microbiol. 77: 1380–1393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westra E. R., van Erp P. B. G., Künne T., Wong S. P., Staals R. H. J., et al. , 2012. CRISPR immunity relies on the consecutive binding and degradation of negatively supercoiled invader DNA by Cascade and Cas3. Mol. Cell 46: 595–605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westra E. R., Semenova E., Datsenko K. A., Jackson R. N., Wiedenheft B., et al. , 2013. Type I-E CRISPR-cas systems discriminate target from non-target DNA through base pairing-independent PAM recognition. PLoS Genet. 9: e1003742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiedenheft B., van Duijn E., Bultema J. B., Bultema J., Waghmare S. P., et al. , 2011. RNA-guided complex from a bacterial immune system enhances target recognition through seed sequence interactions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 108: 10092–10097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiedenheft B., Sternberg S. H., Doudna J. A., 2012. RNA-guided genetic silencing systems in bacteria and archaea. Nature 482: 331–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong N., Liu W., Wang X., Doudna J., Charpentier E., et al. , 2015. WU-CRISPR: characteristics of functional guide RNAs for the CRISPR/Cas9 system. Genome Biol. 16: 218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu X., Scott D. A., Kriz A. J., Chiu A. C., Hsu P. D., et al. , 2014. Genome-wide binding of the CRISPR endonuclease Cas9 in mammalian cells. Nat. Biotechnol. 32: 670–676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie K., Minkenberg B., Yang Y., 2015. Boosting CRISPR/Cas9 multiplex editing capability with the endogenous tRNA-processing system. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 112: 3570–3575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yosef I., Goren M. G., Qimron U., 2012. Proteins and DNA elements essential for the CRISPR adaptation process in Escherichia coli. Nucleic Acids Res. 40: 5569–5576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All high-throughput retention assay data are deposited at the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) Archive (Study Accession PRJNA388730 (SRP108442)). Provisional “working model” sequence assemblies for plasmid pPD207.846 (File S1) and for the assembled λ-Rts genome (File S2) (Campbell and Del Campillo-Campbell 1963) are provided with this manuscript as Supplemental Material.