Abstract

Cellular damage caused by reactive oxygen species is believed to be a major contributor to age-associated diseases. Previously, we characterized the Caenorhabditis elegans Brap2 ortholog (BRAP-2) and found that it is required to prevent larval arrest in response to elevated levels of oxidative stress. Here, we report that C. elegans brap-2 mutants display increased expression of SKN-1-dependent, phase II detoxification enzymes that is dependent on PMK-1 (a p38 MAPK C. elegans ortholog). An RNA-interference screen was conducted using a transcription factor library to identify genes required for increased expression of the SKN-1 target gst-4 in brap-2 mutants. We identified ELT-3, a member of the GATA transcription factor family, as a positive regulator of gst-4p::gfp expression. We found that ELT-3 interacts with SKN-1 to activate gst-4 transcription in vitro and that elt-3 is required for enhanced gst-4 expression in the brap-2(ok1492) mutant in vivo. Furthermore, nematodes overexpressing SKN-1 required ELT-3 for life-span extension. Taken together, these results suggest a model where BRAP-2 acts as negative regulator of SKN-1 through inhibition of p38 MAPK activity, and that the GATA transcription factor ELT-3 is required along with SKN-1 for the phase II detoxification response in C. elegans.

Keywords: oxidative stress, SKN-1, GATA transcription factors, BRAP-2, ELT-3

REACTIVE oxygen species (ROS) can cause damage to a variety of cellular components and are believed to contribute to the development of diseases associated with aging such as Alzheimer’s or Parkinson’s. The overproduction of these oxygen derivatives can lead to extensive tissue and cellular damage that ultimately leads to cell death (Finkel 2011). To cope with changes in ROS levels and to maintain homeostasis and cell survival, organisms possess a sophisticated defense mechanism that induces the expression of detoxification enzymes to remove excessive oxygen radicals. Two key regulators of the mammalian stress response are FOXO and the NF-E2-related factor (Nrf2) transcription factors, which are responsible for inducing the expression of genes required for detoxifying stress compounds and promoting longevity (Moi et al. 1994; Itoh et al. 1999; Kops et al. 2002).

Nrf2 is evolutionarily conserved and is present in Caenorhabditis elegans, where it is known as SKN-1 (Blackwell et al. 2015). SKN-1 was initially identified as the transcription factor that initiates endoderm specification during embryogenesis (Bowerman et al. 1992, 1993). However, like its homolog in humans, SKN-1 also functions in regulating the expression of the C. elegans phase II detoxification response (An and Blackwell 2003). In the intestine, the main detoxification organ in C. elegans, SKN-1 accumulates in nuclei and activates target genes in response to environmental stresses. Genes upregulated by activated SKN-1 include glutathione-S-transferase 4 (gst-4), the γ-glutamine cysteine synthetase heavy chain (gcs-1), and a wide range of genes that are involved in membrane, lysosomal, and proteasomal homeostasis (Oliveira et al. 2009). However, these detoxification genes are often regulated through complex transcriptional networks, and some SKN-1 target genes are also under the regulatory control of SKN-1-independent mechanisms.

Nrf2/SKN-1 activity is regulated by proteasomal degradation and by phosphorylation-dependent control of subcellular localization. Phosphorylation of Nrf2/SKN-1 by specific kinases can either promote or prevent translocation from the cytosol to the nucleus, where gene expression can then be initiated. Kinase-signaling pathways that promote Nrf2/SKN-1nuclear localization, thus acting as positive regulators, include the p38/Erk MAPK pathways and the JNK stress-activated pathway (Inoue et al. 2005; Okuyama et al. 2010); while negative regulators (i.e., phosphorylation that promotes cytosolic localization) of Nrf2/SKN-1 include GSK-3β and SGK-1 pathways (An et al. 2005; Tullet et al. 2008). Nrf2 is negatively regulated by the oxidative stress sensor Keap1 that promotes cytoplasmic localization and degradation of Nrf2 (Kobayashi et al. 2006). Proteasomal degradation of Nrf2 also occurs in a Keap1-independent manner, demonstrated by mutations in Nrf2 that abolish the Nrf2/Keap1 interaction yet still exhibits targeted degradation (Suzuki and Yamamoto 2015). C. elegans lacks a Keap1 ortholog; however, the C. elegans protein WDR-23 (which interacts with the CUL-4/DDB-1 complex) acts analogously by targeting SKN-1 for degradation, thus preventing its accumulation (Choe et al. 2009).

Our interest lies in further understanding the mechanisms by which an organism responds to oxidative conditions. To this end, we examined the role of Brap2 (BRCA1-binding protein 2 or Brap as listed in the Human Genome Organisation database) in this response. Mammalian Brap2 is an E3 ubiquitin ligase that inhibits Brca1 nuclear localization by binding to the Brca1 nuclear localization signal motifs (Li et al. 1998). Brap2 also acts as a cytoplasmic retention protein that prevents nuclear import of the SV40 large T antigen, mitosin (CENP-F), p21WAF1/CIP1, Cdc14, along with a number of proteins isolated by yeast two-hybrid screening using a testis library (Li et al. 1998; Chen et al. 2009; Davies et al. 2013; Fatima et al. 2015). Brap2 was found to be auto-polyubiquitinated in response to Ras activation. This action then releases the Brap2 inhibition of kinase suppressor of Ras (KSR) and activates the KSR–RAF–MEK complex, resulting in increased stimulus-dependent MEK activation (Matheny et al. 2004).

Previously, we identified the C. elegans Brap2 ortholog (BRAP-2) and found that it is required to prevent larval arrest in response to elevated levels of ROS (Koon and Kubiseski 2010). Because brap-2 mutants display increased sensitivity to oxidative stress, we measured the expression levels of ROS detoxification enzymes in these animals. The work presented here provides evidence for a new role for BRAP-2 in response to oxidative stress through SKN-1. We report that the brap-2(ok1492) mutation triggered a PMK-1-/SKN-1-dependent induction of the phase II detoxification response. An RNA interference (RNAi) screen found that this enhancement is dependent on the transcription factor ELT-3, a member of the GATA transcription factor family. We demonstrate that ELT-3 physically interacts with SKN-1 to activate gst-4 transcription in vitro and that worms overexpressing SKN-1 required ELT-3 for the phase II detoxification response in vivo. Together, these observations suggest a model where the removal of BRAP-2 leads to the PMK-1-dependent activation of SKN-1 and ELT-3 to promote expression of nematode phase II detoxification enzymes.

Materials and Methods

C. elegans strains

All C. elegans strains were maintained as described by Brenner (1974). Experiments were performed at 20° unless stated otherwise. C. elegans strains used in this study are listed in Supplemental Material, Table S1. Unless noted, all C. elegans strains were obtained from the Caenorhabditis Genetics Center.

GFP reporter analysis

To investigate GFP expression in a brap-2(ok1492) background, transgenic worms were generated using standard C. elegans techniques and confirmed by single-worm PCR. L4-stage animals were picked and anesthetized using 25 mM Levamisole (#L9756, Sigma Chemical, St. Louis, MO) and mounted on 2% agarose pads. Images of fluorescent animals were taken using a Carl Zeiss (Thornwood, NY) LSM 700 confocal laser-scanning microscope with Zen 2010 Software. For SKN-1B/C::GFP localization studies, the accumulation of nuclear localization was categorically quantified (n = 22). “Low” refers to animals in which SKN-1B/C::GFP was barely detectable in either anterior or posterior intestinal nuclei, “medium” refers to detection in both anterior and poster intestinal nuclei, and “high” refers to detection throughout the intestinal nuclei (Inoue et al. 2005).

Cell culture and transfection

Human embryonic kidney (HEK) cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum. For transfection, 5 µg (pull-down assay) or 0.5 µg (luciferase assay) of mammalian expression constructs were cotransfected in HEK-293T cells using the transfection reagent polyethylenimine.

Pull-down assay and Western blot

A GST pull-down assay was performed to investigate SKN-1/ELT-3 interaction. HEK-293T cells were cotransfected with plasmids coding EGFP::SKN-1 and GST::ELT-3, and cells were lysed in Tris-buffered saline containing 1% NP-40 and Complete Protease Inhibitor Cocktail (#D06159166, Calbiochem, San Diego, LA) 72 hr after transfection. The GST-tagged protein was then pulled down from cell lysates using glutathione sepharose beads (#17-0756-01, Roche), according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Samples were analyzed by standard SDS polyacrylamide gel, followed by Western blot analysis. The antibodies used were anti-GST (#2622, NEB), and anti-GFP (1:5000) (#SC-9996, Santa Cruz).

For Western blots of whole-worm lysates, synchronized adult worms were grown for each genotype. Packed worms (100 µl) were washed with M9 buffer and resuspended in worm lysis buffer [50 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, 1 mM EDTA, protease inhibitor and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (#P5726 and #P0044, Sigma Chemical)] followed by sonication (10 sec ON/10 sec OFF, 10% amplitude for 2 min). The lysates were cleared by centrifugation and the total protein lysate concentrations were quantified using a bicinchoninic acid (BCA) assay according to the manufacturer’s protocol (#23227, Thermo Scientific). Western blots were performed by loading 50 µg of total protein lysates and blots were probed with anti-phospho p38 MAPK antibody (1:200) (#4511, NEB) and anti-tubulin (1:1000) (#3873, Cell Signal). The PMK-1 band densities were measured and normalized to their respective anti-tubulin protein levels using ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health).

Luciferase assay

The gst-4 promoter region (724 bp) was amplified from wild-type C. elegans genomic DNA by PCR, and the DNA product was cloned into a KpnI digested pGL4.10 luciferase vector using the In-Fusion HD Cloning Plus, following the manufacturer’s instructions (#638909, Clontech).

HEK293T cells were transfected with the promoter plasmid, designated transcription factor plasmids, and the pRL-TK Renilla internal control vector in a six-well plate. Cell lysates were collected after 48 hr transfection and luciferase assays were performed using the Promega (Madison, PA) Dual-Glo Luciferase Assay System (E2920) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Each transfection was done in triplicate and samples were then averaged. The Firefly and Renilla luminescence signals from the cells were detected using the Wallac 1420 Plate Reader.

Paraquat/arsenite treatment

N2 and elt-3 strains were collected with M9 buffer and treated with 100 mM paraquat (#856177, Sigma Chemical) or 5 mM sodium arsenite (#35000-1L-R, Sigma Chemical) for 2 hr to induce stress shock, followed by RNA isolation, and quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) for gst-4 messenger RNA (mRNA) quantification. M9 buffer treatment was performed simultaneously as control. The experiment was completed in three independent trials. To assay for arsenite and paraquat toxicity, young adults were placed in M9 buffer as above and the number of surviving worms were counted at the indicated times. Results from the three independent trials were pooled and the average number of surviving animals (± SE) per time point was plotted.

Transcription factor RNAi screening and RNAi assays

To identify new regulators and coactivators of SKN-1, an RNAi screen was performed using a near-complete transcription factor RNAi library that contains 882 of the 934 predicted transcription factors (Reece-Hoyes et al. 2005) and 30 unconventional DNA binding proteins (Table S2), as described previously (MacNeil et al. 2015). The RNAi screen was performed in 96-well plates, with each transgenic strain screened in three independent trials using dvIs19 and brap-2(ok1492);dvIs19 strains which express GFP under the control of the gst-4 promoter. RNAi was carried out by feeding animals with bacteria containing a plasmid with the ORF of a specific transcription factor, and the change in GFP expression in the whole worm was visually monitored in the RNAi-treated worms. Each plate contained a positive (RNAi for gfp) and negative (empty vector pL4440) control. Animals that showed a diminished GFP expression in at least two of the three trials were scored as positives, excluding RNAi samples that produced dead, sick, or slow-growing worms. Further RNAi assays to validate the positive candidates were carried out by feeding worms double-stranded RNA on bacterial NGM plates containing ampicillin (100 µg/ml), IPTG (0.4 mM), and tetracycline (12.5 µg/ml).

Chromatin immunoprecipitation

Protein lysates were prepared and chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) was performed as described with some modification (Mukhopadhyay et al. 2008; Claycomb et al. 2009). Briefly, synchronized L4 worms were collected and frozen worm pellets were prepared using liquid nitrogen prior to sonicating and cross-linking. Lysates were collected by centrifugation and the total protein concentration was determined using a Thermo Fisher BCA Assay Kit (#23227). An amount of 0.5 mg of total protein lysates along with IgG (#ab37415, Abcam) or anti-GFP (#ab290, Abcam) antibody was used for overnight incubation. DNA collected from reverse cross-linking was resuspended in 25 µl double-distilled H2O followed by qRT-PCR. The sequences of oligonucleotides used in this study are listed in Table S3.

RNA isolation and qRT-PCR

For each strain, mixed-stage worms were collected and washed three times with M9 buffer. Total RNA was isolated using TRI Reagent (#93289, Sigma Chemical) as described by the manufacturer’s protocol. The collected RNA was then treated with DNA-free DNA Removal Kit (#AM1906, Ambion). Total RNA concentration was determined using the Thermo Fisher NanoDrop2000 and 0.5 µg of RNA was used to carry out reverse-transcription PCR with Applied Biosystems (Foster City, CA) RNA-to-cDNA Kit (#4387406) in a 20-µl reaction following the manufacturer’s protocol. SYBR Green (#98005, FroggaBio) qRT-PCR was conducted using QIAGEN (Valencia, CA) Rotor-Gene Q Detection System and analyzed using the comparative method (ΔΔCt). qRT-PCR data were derived from three independent replicates. Results were graphed and the mRNA expression level of each strain was compared relative to N2. The endogenous control used for normalization was act-1 (Tullet et al. 2008) unless otherwise specified. act-1 mRNA levels were compared to other reference genes in a number of strains used in this study, and its level of expression was consistent between them (Figure S1A in File S1). A standard curve for each set of primers was constructed using a serial dilution of complementary DNA to verify equal amplification efficiency.

Statistics

Statistical analysis was performed with Prism 7 software (GraphPad). Statistical significance was determined using a Student’s t-test when two means were compared and P-values < 0.05 were taken to indicated statistical significance. Error bars represent ± SEM.

Life-span assay

Life-span assays were performed as previously described (Wilkinson et al. 2012). The long-lived strain LD1250 (ldEx7) and N2 were raised at 20° on NGM plates seeded with Escherichia coli HT115. At L1, 40 worms were placed onto elt-3 RNAi seeded plates. Worms were transferred to fresh plates (away from progeny) and survival was scored every day as response to prodding. Missing nematodes or worms that died from vulval bursting were censored. The online program Oasis2 was used to generate the Kaplan–Meier curves and log-rank analysis was used to compare the significance of the survival curves using median life span (Han et al. 2016).

Data availability

Strains are available upon request or through the Caenorhabditis Genetics Center. All the data necessary for confirming the conclusions presented in the article are represented fully within the article and Supplemental Material.

Results

brap-2 mutants display increased expression of phase II detoxification genes

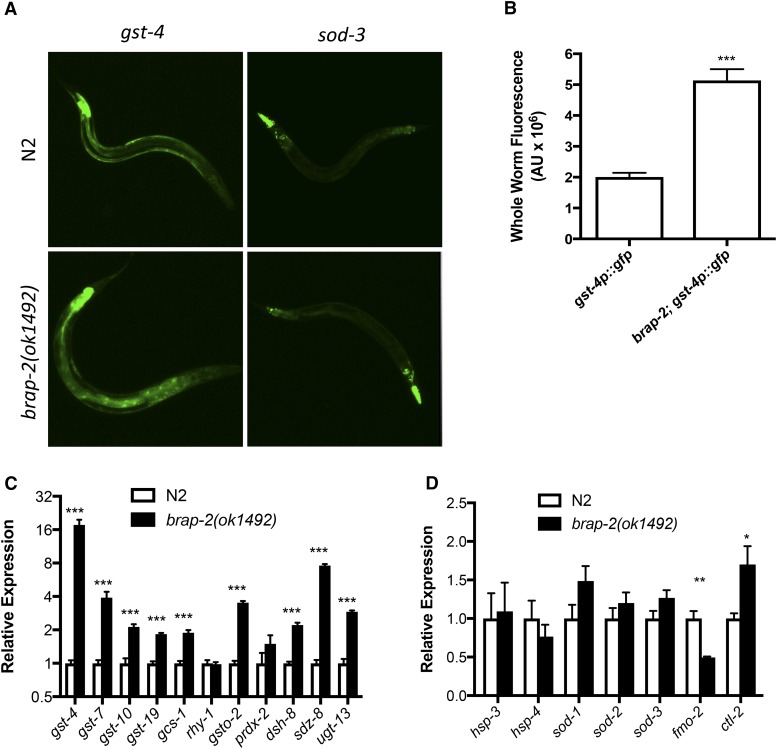

Our current interest in studying the mechanisms controlling an organism’s response to oxidizing conditions came about from studying the physiological role of C. elegans BRAP-2. We observed that brap-2(ok1492) worms arrest at the L1 larval stage when exposed to oxidative stress, and we hypothesized that the brap-2(ok1492) mutant may have altered expression of ROS detoxification enzymes. To test this hypothesis, we used transgenic animals carrying either the transcriptional oxidative-stress-sensitive reporters gst-4p::gfp (a SKN-1 reporter gene) or sod-3p::gfp (a DAF-16 responsive transgene) and analyzed GFP expression levels in wild-type and brap-2(ok1492) mutant animals. We found that brap-2(ok1492) worms expressed elevated levels of GFP in intestinal and hypodermal cells in gst-4p::GFP animals compared to wild-type animals, while no change in sod-3p::gfp reporter levels was observed (Figure 1A). We also measured whole-worm fluorescence of animals expressing GFP under control of the gst-4 promoter and found that the brap-2 mutant worms had a 2.5-fold increase in GFP levels compared to wild type (Figure 1B). We next examined endogenous mRNA levels by qRT-PCR. Consistent with the results obtained from fluorescent microscopy, relative to wild-type animals, brap-2(ok1492) mutants displayed an ∼10- to 15-fold increase in gst-4 expression (Figure 1C and Figure S1B in File S1). To confirm activation of phase II genes, we examined 10 additional phase II genes and 8 out of 10 showed a significant increase in expression in the brap-2 mutant relative to wild type (Figure 1C). We also quantified mRNA levels of other nonphase II stress response genes, and of the seven tested, we found one, ctl-2, increased in the brap-2 mutant by 1.7 times as compared to wild type (Figure 1D). Therefore, the brap-2(ok1492) mutation generates a specific activation of the phase II detoxification genes and not a general stress response.

Figure 1.

gst-4 expression levels are higher in brap-2(ok1492) worms. (A) brap-2(ok1492) mutants display increased gst-4p::GFP in hypodermis and the intestine, but the sod-3p::GFP expression is not affected. (B) GFP levels of brap-2(ok1492) worms expressing gst-4p::GFP were ∼2.5 times that of wild type. Quantification was done using ImageJ (n = 18 for each sample). (C) The mRNA levels of 11 phase II detoxification genes (log2 scale) were compared between wild type and brap-2(ok1492) mutants. A significant increase in mRNA levels was found in 9 of 11 phase II genes in the mutant strain. (D) The mRNA levels of nonphase II stress-related genes were measured by qPCR. Of the seven genes tested, only one showed a significant increase in the brap-2(ok1492) mutant. *** P < 0.001, ** P < 0.01, * P < 0.05.

In response to oxidative stress, the phase II detoxification genes in C. elegans are induced by the transcription factor SKN-1. To determine whether the activation of these genes in brap-2(ok1492) mutants is mediated by SKN-1, RNAi was used to knockdown skn-1 in brap-2(ok1492) animals. As expected, a reduction of gst-4 expression was seen with skn-1 depletion (Figure 2A). In addition, skn-1(zu67) (a loss-of-function mutant of skn-1) and brap-2(ok1492); skn-1(zu67) mutants demonstrated a decrease in gst-4 levels (Figure 2B). These results indicate that the increased expression of gst-4 in brap-2(ok1492) mutants is dependent on the transcription factor SKN-1.

Figure 2.

Enhanced gst-4 expression in brap-2(ok1492) requires SKN-1. (A) Synchronized gst-4p::gfp and brap-2(ok1492);gst-4p::gfp worms were grown in control (L4440) or skn-1 RNAi. brap-2(ok1492) shows decreased gst-4 expression when skn-1 is knocked down in L4 worms. (B) RNA was extracted and the gst-4 mRNA levels (log2 scale) were quantified using qRT-PCR. The brap-2(ok1492);skn-1(zu67) double mutant showed a reduction of gst-4 mRNA expression. ** P < 0.01.

As a common mechanism of SKN-1 control is the regulation of its transport into the nucleus, we investigated the subcellular localization of SKN-1 in N2 and brap-2(ok1492) worms. C. elegans skn-1 encodes three splice variants (SKN-1A, SKN-1B, and SKN-1C), each with its own distinct expression pattern and function. SKN-1A is an ER-associated isoform involved in promoting transcriptional response to proteasomal dysfunction, while SKN-1B and SKN-1C have roles in caloric restriction and stress resistance, respectively (An and Blackwell 2003; Bishop and Guarente 2007; Glover-Cutter et al. 2013; Lehrbach and Ruvkun 2016). Using L4 nematodes carrying a translational skn-1b/c::gfp reporter, we found that, in the absence of brap-2, the incidence of SKN-1B/C localization within intestinal nuclei was 2.6-fold higher compared to wild-type animals (Figure 3, A and B). This suggests that BRAP-2 functions to inhibit the nuclear localization of SKN-1, either directly or indirectly. To determine whether BRAP-2 inhibits SKN-1 nuclear localization through direct interaction with SKN-1, we attempted to co-immunoprecipitate the two proteins. However, we were unable to detect a physical interaction between BRAP-2 and SKN-1.

Figure 3.

Increased SKN-1 intestinal nuclear localization and binding to the gst-4 promoter in brap-2(ok1492). (A) Localization of skn-1::gfp in N2 (top) and brap-2(ok1492) (bottom) worms. Synchronized worms were grown on NGM plates and L4 worms were picked to visualize GFP expression using confocal microscopy. The white arrows indicate the locations of intestinal nuclei. Results indicated an accumulation of SKN-1::GFP in intestinal nuclei in brap-2(ok1492) animals. (B) Percentage of SKN-1::GFP nuclear localization in brap-2(ok1492) and N2 worms were categorically scored and quantified as described in Materials and Methods. The percentage of nuclear localization increased 2.6-fold in brap-2 mutant worms as compared to wild type. (C) RNA was isolated from N2 and brap-2(ok1492) worms followed by quantification of skn-1a, skn-1b, and skn-1c mRNA transcript levels using qRT-PCR. Results demonstrated an enhanced skn-1b and skn-1c expression in brap-2(ok1492). *** P < 0.001, ** P < 0.01 vs. N2. (D) Isoform-specific RNAi of skn-1a, skn-1b, and skn-1c isoforms of skn-1 was performed and gst-4 mRNA levels quantified by qRT-PCR. Knockdown of skn-1c showed a significant reduction of gst-4 expression (log2 scale) in in wild-type and brap-2 mutant animals. *** P < 0.001. (E) ChIP–qPCR analysis of SKN-1 binding at two gst-4 promoter regions in skn-1::gfp::3xFlag- and brap-2(ok1492); skn-1::gfp::3xFlag-expressing worms. Relative percentage input is normalized to N2 (absence of GFP antigen). Data represented the mean of four independent trials.

Interestingly, we saw an overall increase in intestinal skn-1::gfp expression in brap-2 mutant animals, suggesting that skn-1 is transcriptionally upregulated in brap-2(ok1492) mutant worms. To determine if the brap-2 mutation causes an increase in endogenous skn-1 expression, qRT-PCR was performed and revealed a 1.5-fold increase in skn-1b and a 2.75-fold increase in skn-1c mRNA levels in brap-2(ok1492), indicating that an accumulation of SKN-1 probably occurs in brap-2 mutant worms (Figure 3C). Notably, we also used skn-1 isoform-specific RNAi constructs to determine the isoform responsible for increased gst-4 expression in brap-2 mutant worms and found that when skn-1c, but not skn-1a or skn-1b, was knocked down, it resulted in a decrease in gst-4 mRNA levels (Figure 3D). Therefore, the brap-2(ok1492) mutant increases both the amount of SKN-1C and its subcellular localization to the nucleus.

SKN-1 directly binds to the promoter regions of its target genes to increase their expression. The modENCODE project has mapped SKN-1 transcription factor binding sites at every stage of C. elegans development using ChIP. These data reveal an enrichment of SKN-1 binding to a number of sites in the gst-4 promoter at the L4 stage of development. Using ChIP, we examined two gst-4 promoter regions containing the canonical SKN-1 binding sites WWTRTCAT or TCTTATCA (An and Blackwell 2003). ChIP–quantitative PCR (qRT-PCR) analysis revealed at least a twofold enrichment in SKN-1 binding at two gst-4 promoter sites in brap-2(ok1492) mutants expressing SKN-1::GFP::3xFLAG compared to wild type at the L4 stage (Figure 3E). These findings confirm that the activation of gst-4 is dependent on the direct interaction of SKN-1 on the gst-4 promoter, and that this interaction is enhanced in the brap-2(ok1492) mutant.

Regulation of SKN-1 by BRAP-2 involves the p38 MAPK pathway

Since SKN-1 is mainly localized in the nucleus of brap-2(ok1492) mutants and we could not detect a physical interaction between BRAP-2 and SKN-1, we hypothesized that the change in SKN-1 subcellular localization may be due to the phosphorylation state of SKN-1. One candidate kinase that may carry out this phosphorylation is PMK-1 (the C. elegans ortholog of mammalian p38 MAPK) whose phosphorylation of SKN-1 promotes its nuclear localization, resulting in activation of SKN-1 target genes that promote longevity (Inoue et al. 2005).

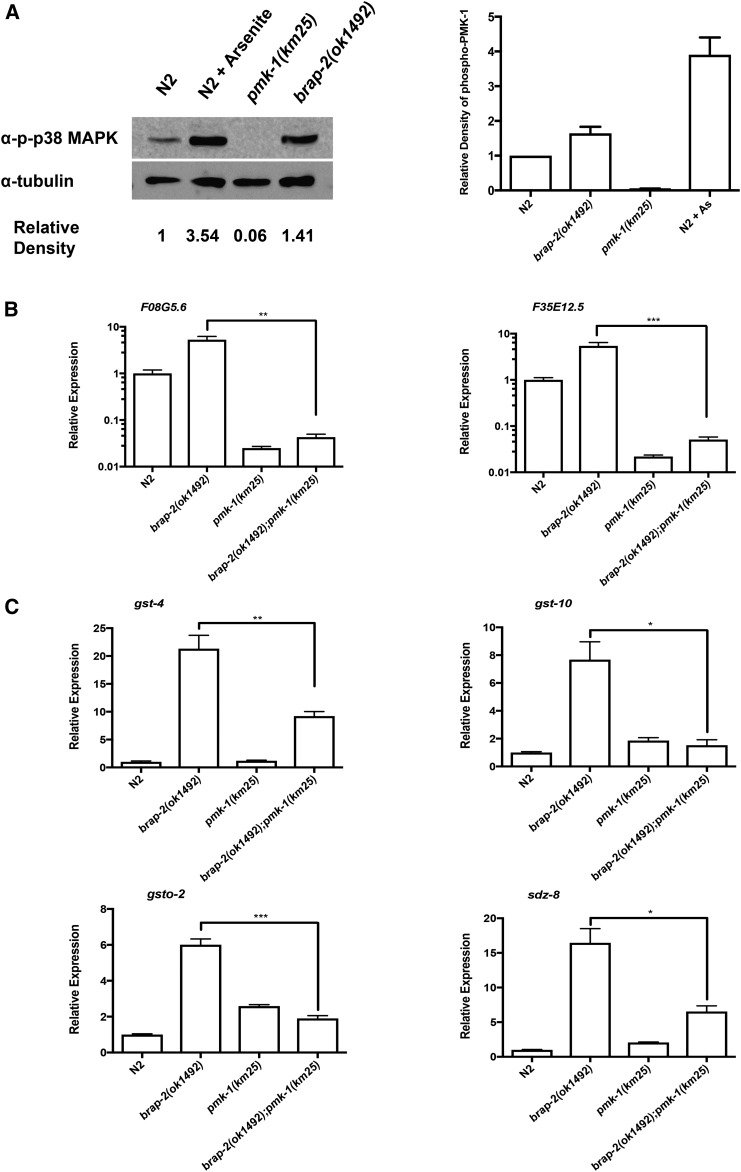

We asked if the p38/PMK-1 pathway was required for BRAP-2 regulation of the SKN-1 detoxification pathway and we found that the brap-2(ok1492) mutation induced a 1.4-fold increase in phospho-PMK levels, as measured by Western blot (Figure 4A); indicative of a modest increase in activated PMK levels. We also quantified the expression of two genes, F08G5.6 and F35E12.5, previously shown to be targets of pmk-1 (Troemel et al. 2006; Cornejo Castro et al. 2010). We found higher levels of mRNA for these two transcripts in brap-2(ok1492) animals compared to wild type, and that this increase was dependent on functional PMK-1, consistent with PMK-1 being activated in brap-2(ok1492) (Figure 4B). Furthermore, we found that PMK-1 was at least partially required for the enhanced expression of phase II detoxification enzymes in brap-2 mutants, as the brap-2;pmk-1 double mutant showed a significant decrease in the mRNA levels of genes tested compared to the brap-2 mutant (Figure 4C). These findings indicate that the p38 MAPK pathway is at least partially responsible for regulating the expression of phase II detoxification genes in the brap-2(ok1492) animals, although whether this is due to BRAP-2 directly regulating PMK-1 activity or some indirect mechanism of activation in the mutant animals remains to be determined.

Figure 4.

PMK-1 is activated in brap-2(ok1492) mutants and is partially required for enhanced gst-4 expression. (A) Phosphorylation level of PMK-1 is increased in brap-2 mutants. (Left) A Western blot of lysates from wild-type, brap-2(ok1492), pmk-1(km25), and wild-type worms treated with arsenite probed with an α-phospho-p38 antibody. (Right) Relative intensity of bands corresponding to phospho-PMK levels were compared to α-tubulin levels using ImageJ and normalized to wild type. The experiment was carried out three times and the relative intensity of the phospho-PMK bands were pooled and graphed. (B) As a measure of PMK-1 activity, transcript levels of two pmk-1 targets (left, F08G5.6; and right, F35E12.5) in brap-2, pmk-1, and brap-2;pmk-1 mutants were measured using qRT-PCR (log10 scale). brap-2(ok1492) animals showed higher levels of transcripts that were dependent on functional pmk-1. (C) PMK-1 is required to promote phase II detoxification gene expression in brap-2(ok1492) worms. The mRNA levels of (top left) gst-4, (top right) gst-10, (bottom left) gsto-2, and (bottom right) sdz-8 were quantified using qRT-PCR. The brap-2;pmk-1 double mutant showed a reduction of mRNA expression for each gene tested. *** P < 0.001, ** P < 0.01, * P < 0.05.

The ELT-3 GATA transcription factor is required for gst-4 expression

Transcription factors are integral components of gene regulatory networks, serving as key regulators of gene activation or repression. The regulation of gene expression could be a product of the interactions between multiple transcription factors, and identifying transcription factors that work in combination with SKN-1 will increase our understanding of the complex regulatory network involved in the phase II detoxification response. Since brap-2(ok1492) activated a signaling cascade that enhanced the SKN-1 phase II detoxification pathway, we used the brap-2(ok1492);gst-4p::gfp strain as the basis for an RNAi screen to test for transcription factors that, when knocked down, suppress gst-4p::gfp expression. Out of 912 tested clones, we identified 18 transcription factors that, when knocked down, resulted in decreased GFP expression in brap-2(ok1492) (Table S4). Among the candidates were three GATA transcription factor family members (elt-1, elt-2, and elt-3), suggesting that GATA transcription factors may play an important role in regulating expression of phase II detoxification enzymes in C. elegans. elt-3 was chosen for further study because it is a potential regulator of aging (Budovskaya et al. 2008) and because elt-3 homozygous mutant animals are viable and amenable to genetic studies. We observed that brap-2(ok1492) worms treated with elt-3 RNAi displayed reduced levels of GFP compared to wild type (Figure 5A). To further validate our RNAi screen, we quantified mRNA levels in brap-2(ok1492);elt-3(vp1) double mutants and found a >60% reduction in gst-4 expression (Figure 5B). These results indicate that ELT-3 is required for the induction of gst-4 expression in the absence of BRAP-2.

Figure 5.

Loss of elt-3 reduced gst-4 expression in brap-2(ok1492) mutants. (A) Synchronized gst-4p::gfp and brap-2(ok1492); gst-4p::gfp worms were grown on control (L4440) or elt-3 RNAi plates and GFP expression was examined at L4 stage of development. brap-2(ok1492) worms show a reduced gst-4p::gfp expression when elt-3 is knocked down. (B) Synchronized worms were grown on NGM plates followed by RNA extraction and qRT-PCR. The double mutant brap-2(ok1492);elt-3(vp1) shows a 70% reduction in gst-4 mRNA expression in comparison to brap-2(ok1492). *** P < 0.001, ** P < 0.01.

After defining the importance of ELT-3 in the expression of gst-4, we asked whether ELT-3 could coactivate and thus enhance SKN-1 activity. To determine if ELT-3 is required for the activation of gst-4 during oxidative stress, we measured gst-4 mRNA levels after arsenite or paraquat treatment in elt-3 mutants. In response to either stressor, gst-4 mRNA levels increased in wild-type animals. However, induction of gst-4 mRNA was significantly decreased in elt-3(vp1) mutants relative to wild-type animals, indicating that ELT-3 is required to induce SKN-1 targets upon oxidative stress (Figure 6A). We also measured the ability of elt-3 mutant worms to survive exposure to oxidative stress. We found that elt-3(vp1) animals were hypersensitive to arsenite, but responded similarly to paraquat as the wild type (Figure 6B and Table S5). The reason for the difference between arsenite and paraquat treatments is not known, but may be due to differences of mechanisms of action in promoting oxidative stress (Lee et al. 2003), or differences in the tissues these compounds may target in vivo.

Figure 6.

ELT-3 is required for gst-4 expression during oxidative stress and synergistically activates gst-4 promoter expression through interaction with SKN-1. (A) Synchronized worms were collected and treated with (left) 5 mM sodium arsenite (As) or (right) 100 mM paraquat (PQ) for 2 hr followed by RNA isolation. qRT-PCR was performed to measure the gst-4 mRNA transcript levels. (B) Survival assays of N2 and elt-3(vp1) strains were determined in (left) arsenite and (right) paraquat. Results indicated ELT-3 is essential for gst-4 expression during oxidative stress and that elt-3 mutant worms are more susceptible to arsenite exposure compared to wild type. (C) Luciferase assay was performed and the transcriptional activity was determined by the activation of the gst-4 promoter/luciferase reporter vector. Maximum activation occurs upon coexpression of both ELT-3 and SKN-1 constructs. (D) A pull down of GST-ELT-3 fusion protein using glutathione sepharose and Western blot using anti-GFP antibody to detect GFP-SKN-1 fusion protein. This assay reveals that EGFP::SKN-1 and GST::ELT-3 physically interact in vitro. * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001.

We then tested whether SKN-1 and ELT-3 physically interact to promote gene expression. ELT-3 activation of gst-4 appears to be direct and, furthermore, ELT-3 binds to the promoters of phase II detoxification enzymes at regions that overlap those of SKN-1, as indicated by modENCODE genome-wide ChIP surveys (Figure S2 in File S1). We generated a luciferase reporter construct using the gst-4 promoter that we transfected into HEK293T cells along with SKN-1 and/or ELT-3. Although a moderate increase in gst-4 promoter expression was seen when either SKN-1 or ELT-3 alone was transfected, a synergistic increase in luciferase expression was detected in the presence of both SKN-1 and ELT-3 (Figure 6C). Furthermore, we cotransfected HEK293T cells with tagged SKN-1 and/or ELT-3 and detected an interaction between SKN-1 and ELT-3 in vitro, suggesting that these two transcription factors heterodimerize (Figure 6D). Therefore, the data presented here show that the GATA transcription factor ELT-3 has an essential role in regulating gst-4 and the oxidative stress response with SKN-1.

Since skn-1b and skn-1c mRNA levels are increased in brap-2(ok1492) mutants, we asked whether ELT-3 was required for this increase. We found that the induction of skn-1b and skn-1c transcripts observed in the brap-2 mutant was completely lost in brap-2(ok1492);elt-3(vp1) double mutants (Figure S3A in File S1). Since SKN-1 has also been found to interact with its own promoter (Gerstein et al. 2010; Figure S3B in File S1), we also tested if SKN-1 could function with ELT-3 in inducing skn-1c expression. We generated a luciferase reporter construct containing the skn-1c promoter, used it to transfect HEK293T cells along with expression vectors for SKN-1 and ELT-3, and found that ELT-3 and SKN-1 synergistically induced the skn-1c promoter (Figure S3C in File S1). These results show that ELT-3 was required for the induction of SKN-1C in the brap-2 mutant, and that these inductions likely required SKN-1.

We also determined the expression pattern and cellular localization of ELT-3 in vivo. The translational reporter strain elt-3::gfp was used and we were able to detect ELT-3 in hypodermal nuclei in both the wild type and brap-2(ok1492) (Figure S4 in File S1). Thus, unlike SKN-1, ELT-3 subcellular localization appears to be independent of BRAP-2 activity. Furthermore, no change in ELT-3::GFP levels was seen when wild-type and brap-2(ok1492) worms were compared, indicating that the brap-2 mutation does not influence ELT-3 expression.

SKN-1 has been shown to promote longevity under certain conditions (Blackwell et al. 2015). For example, while transgenes that produce high levels of SKN-1 are harmful, moderate levels of SKN-1 overexpression lead to life-span extension (Tullet et al. 2008; Blackwell et al. 2015). A number of skn-1 gain-of-function mutations have been identified. A mutation in SKN-1 that disrupts its interaction with the inhibitor WDR-23 and promotes SKN-1 stability leads to life-span extension (Choe et al. 2009), while two other characterized gain-of-function mutations (lax120 and lax188) have no significant effect on life span (Paek et al. 2012); demonstrating the complexity of SKN-1’s role in life-span extension. Since the transcription factor ELT-3 is involved in the regulation of aging and is needed for phase II detoxification gene expression, we sought to determine whether ELT-3 is required to coactivate the SKN-1 regulated pathway for life-span extension. To test this, we used the moderately expressing SKN-1 transgenic strain (LD1250; Tullet et al. 2008), knocked down elt-3 by RNAi, and performed a life-span assay. Overexpressing SKN-1 significantly increased life span compared to wild type, while RNAi-mediated knockdown of elt-3 in this strain prevented this increase (Figure 7 and Table S6). This may indicate that the enhanced life span observed in transgenic animals overexpressing SKN-1 is dependent on functional ELT-3, although it is possible that the decrease in life span could be due to the elt-3 mutation making the animals less healthy in general. Since brap-2(ok1492) activates SKN-1, we also asked if the brap-2(ok1492) animals had an increased life span. However, brap-2(ok1492) worms demonstrated a shorter life span compared to wild type (Figure S5 in File S1), possibly due to either an insufficient amount of activated SKN-1, inactivation of other detoxification enzymes (such as phase I detoxification enzymes), and/or modification of some as-yet-unidentified pathway or physiological process in the brap-2 mutant that prevents life span extension.

Figure 7.

Extended life span in overexpressing SKN-1 requires ELT-3. Survival curves of N2 and worms containing the SKN-1 transgene [strain LD1250 (ldEx7) expressing skn-1b/c::gfp] fed on control bacteria (L4440) or bacteria expressing elt-3 RNAi from L1 worms at 20°. While skn-1b/c::gfp has a significantly longer life span than N2 (mean life spans are 16.7 ± 0.79 days and 13.6 ± 0.62 days, respectively; n = 40), less extension of life span was observed in overexpressing SKN-1B/C in elt-3 RNAi (skn-1b/c::gfp mean = 11.1 ± 0.45 days compared to N2 mean = 11.1 ± 0.38 days; n = 40). Two independent experiments were performed, data represents one trial.

Discussion

The work presented here identifies new roles for BRAP-2 and ELT-3 in oxidative stress response through the transcription factor SKN-1. Using C. elegans as a model organism, we have shown that the expression of the phase II detoxification genes is increased in the brap-2(ok1492) deletion mutant. This strain was used to perform a transcription factor-specific RNAi screen which identified the GATA transcription factor ELT-3 as a regulator of gst-4 expression. We also demonstrated that BRAP-2 and the PMK-1 pathway are involved in regulating the SKN-1/ELT-3 response to oxidative stress. Recently, the related GATA transcription factor ELT-2 was shown to control C. elegans immune responses in a p38-dependent manner (Block et al. 2015), indicating that the p38 MAPK pathway may play a general role in regulating GATA transcription factor function in response to different types of stress.

Previously, we demonstrated that the brap-2(ok1492) mutant worms are sensitive to oxidative stress, as they undergo L1 larval arrest when exposed to paraquat (Koon and Kubiseski 2010). Paradoxically, we find and report here that these animals have higher mRNA expression of SKN-1-dependent phase II detoxification enzymes, which would presumably lead to an enhancement of the cellular mechanisms to deal with ROS and a reduction in oxidative stress. One possibility to explain this paradox is that SKN-1-dependent phase II detoxification enzymes by themselves are insufficient in completely removing oxidative stress, and alternate signaling pathways or mechanisms are also required. These alternate pathways may be compromised in brap-2(ok1492) mutants, preventing them from fully detoxifying ROS compared to wild-type animals, and enhancing their sensitivity to ROS-producing compounds such as paraquat.

The SKN-1 ortholog Nrf2 is a regulator of the major pathways that control detoxification and oxidative stress responses in humans. Defective Nrf2 regulation is commonly found in human diseases, including cancer and Parkinson’s disease, and Nrf2 is a candidate target in designing therapeutic agents for attenuation of oxidative stress. Although we do not know if mammalian Brap2 has a similar function in the regulation of Nrf2, our findings in C. elegans identify candidate regulatory mechanisms that may also play a role in the oxidative stress response in mammals.

The increased expression of gst-4 in brap-2(ok1492) mutants provided an opportunity to identify novel transcription factors required for phase II detoxification response in C. elegans using a genetic suppression screen. We identified elt-3 as a regulator of gst-4. In the worm, GATA transcription factors have well-established roles in directing tissue-specific developmental processes (Block and Shapira 2015). elt-3 is a member of the GATA family of transcription factors that is expressed in the epidermis during development (Gilleard et al. 1999; Gilleard and McGhee 2001; McGhee 2013b). SKN-1A/C::GFP transgenes readily show expression in intestinal cells; however, SKN-1-induced detoxification gene expression can be detected in the hypodermis, suggesting that SKN-1 is active in some tissues when present at low levels (Paek et al. 2012). We show that SKN-1 and ELT-3 interact in vitro and together enhance transcriptional activity of phase II target genes, indicating that ELT-3 is likely involved in the regulation of this signaling pathway in hypodermal cells. It has been reported that elt-3 is vital to the regulation of aging, where it is responsible for regulating the expression of specific genes, including sod-3; that it is involved in somatic aging; and that elt-3 is regulated by the DAF-2 insulin-like signaling pathway, where elt-3 loss of function reverses the life-span extension observed in daf-2 mutants (Budovskaya et al. 2008), although this result is controversial (Kim et al. 2012; Tonsaker et al. 2012; Kim et al. 2013; McGhee 2013a). ELT-2, a GATA transcription factor expressed in the intestine, has also been shown to be deactivated during aging and overexpression of ELT-2 extends life span (Mann et al. 2016), so it is possible that ELT-2 and SKN-1 may heterodimerize in the intestine to activate expression of phase II detoxification enzymes as a response to oxidative stress.

Overall, these studies indicate that GATA transcription factors play a role in promoting longevity in C.elegans. ELT-3 shows the highest homology to GATA3, a protein that is highly expressed in human epidermal tissues and lymphocytes (Molkentin 2000; Kaufman et al. 2003). We would predict that, if this process were conserved between C. elegans and humans, Nrf2 and GATA3 (or a closely related GATA transcription factor) would function together to regulate the phase II detoxification response in mammalian cells. Although, to our knowledge, a direct role of GATA3 in regulating response to oxidative stress has not yet been characterized, Nrf2 and GATA3 have been shown to activate cytokine production in response to tert-butylhydroquinone (a synthetic antioxidant) in CD4+ T cells (Rockwell et al. 2012).

Like mammals, nematodes have well-developed lines of defense for protection against toxic compounds. The C. elegans genome encodes a wide range of stress response genes, providing systematic stress response and detoxification strategies. The transcription factor SKN-1 is regarded as a master regulator for the expression of phase II detoxification genes. Our data indicates that BRAP-2 regulates the oxidative stress response by negatively regulating both skn-1 transcript levels and subcellular localization of SKN-1. While most studies have focused on the post-translational modification of SKN-1 [such as phosphorylation and ubiquitination (An et al. 2005; Inoue et al. 2005; Tullet et al. 2008; Choe et al. 2009; Okuyama et al. 2010)] as the main mechanism of regulation, our work suggests that skn-1 transcription is induced upon oxidative stress, as determined by qRT-PCR, and that this induction requires ELT-3.

Oxidative stress is believed to play a critical role in the progression of many diseases including cancer and neurodegenerative diseases. The work presented here provides insight into BRAP2’s and SKN-1’s roles in the oxidative stress response. We believe that using C. elegans to study the coordination of p38 MAPK signaling through proteins such as BRAP-2 enable us to gain a better understanding of diseases caused by stress, as well as identify new targets for future therapies. C. elegans mutants lacking BRAP-2 are highly sensitive to oxidative stress, providing us with a valuable genetic tool to reveal a possible new role for BRAP-2 in the regulation of the SKN-1/ELT-3 complex in response to oxidative stress through the p38 MAPK pathway.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental material is available online at www.genetics.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1534/genetics.116.198788/-/DC1.

Acknowledgments

We thank Keith Blackwell for the SKN-1-overexpressing strain LD1250 (ldEx7) and Jim McGhee for elt-3(vp1) (JG1). A number of strains were provided by the Caenorhabditis Genetics Center, which is funded by the National Institutes of Health Office of Research Infrastructure Programs (P40 OD-010440). A.J.M.W. and L.T.M. were supported by the National Institutes of Health grants DK-068429 and GM-082971. D.D is a recipient of the Ontario Graduate Scholarship. Q.H., D.R.D., and T.J.K were supported by a grant from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada.

Footnotes

Communicating editor: B. Goldstein

Literature Cited

- An J. H., Blackwell T. K., 2003. SKN-1 links C. elegans mesendodermal specification to a conserved oxidative stress response. Genes Dev. 17: 1882–1893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- An J. H., Vranas K., Lucke M., Inoue H., Hisamoto N., et al. , 2005. Regulation of the Caenorhabditis elegans oxidative stress defense protein SKN-1 by glycogen synthase kinase-3. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102: 16275–16280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishop N. A., Guarente L., 2007. Two neurons mediate diet-restriction-induced longevity in C. elegans. Nature 447: 545–549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackwell T. K., Steinbaugh M. J., Hourihan J. M., Ewald C. Y., Isik M., 2015. SKN-1/Nrf, stress responses, and aging in Caenorhabditis elegans. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 88: 290–301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Block D. H., Shapira M., 2015. GATA transcription factors as tissue-specific master regulators for induced responses. Worm 4: e1118607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Block D. H. S., Twumasi-Boateng K., Kang H. S., Carlisle J. A., Hanganu A., et al. , 2015. The developmental intestinal regulator ELT-2 controls p38-dependent immune responses in adult C. elegans. PLoS Genet. 11: e1005265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowerman B., Eaton B. A., Priess J. R., 1992. skn-1, a maternally expressed gene required to specify the fate of ventral blastomeres in the early C. elegans embryo. Cell 68: 1061–1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowerman B., Draper B. W., Mello C. C., Priess J. R., 1993. The maternal gene skn-1 encodes a protein that is distributed unequally in early C. elegans embryos. Cell 74: 443–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenner S., 1974. The genetics of Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 77: 71–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budovskaya Y. V., Wu K., Southworth L. K., Jiang M., Tedesco P., et al. , 2008. An elt-3/elt-5/elt-6 GATA transcription circuit guides aging in C. elegans. Cell 134: 291–303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J., Hu H., Zhang S., He M., Hu R., 2009. Brap2 facilitates HsCdc14A Lys-63 linked ubiquitin modification. Biotechnol. Lett. 5: 615–621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choe K. P., Przybysz A. J., Strange K., 2009. The WD40 repeat protein WDR-23 functions with the CUL4/DDB1 ubiquitin ligase to regulate nuclear abundance and activity of SKN-1 in Caenorhabditis elegans. Mol. Cell. Biol. 29: 2704–2715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claycomb J. M., Batista P. J., Pang K. M., Gu W., Vasale J. J., et al. , 2009. The Argonaute CSR-1 and its 22G-RNA cofactors are required for holocentric chromosome segregation. Cell 139: 123–134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornejo Castro E. M., Waak J., Weber S. S., Fiesel F. C., Oberhettinger P., et al. , 2010. Parkinson’s disease-associated DJ-1 modulates innate immunity signaling in Caenorhabditis elegans. J. Neural Transm. (Vienna) 117: 599–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies R. G., Wagstaff K. M., McLaughlin E. A., Loveland K. L., Jans D. A., 2013. The BRCA1-binding protein BRAP2 can act as a cytoplasmic retention factor for nuclear and nuclear envelope-localizing testicular proteins. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1833: 3436–3444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fatima S., Wagstaff K. M., Loveland K. L., Jans D. A., 2015. Interactome of the negative regulator of nuclear import BRCA1-binding protein 2. Sci. Rep. 5: 9459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkel T., 2011. Signal transduction by reactive oxygen species. J. Cell Biol. 194: 7–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerstein M. B., Lu Z. J., Van Nostrand E. L., Cheng C., Arshinoff B. I., et al. , 2010. Integrative analysis of the Caenorhabditis elegans genome by the modENCODE project. Science 330: 1775–1787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilleard J. S., McGhee J. D., 2001. Activation of hypodermal differentiation in the Caenorhabditis elegans embryo by GATA transcription factors ELT-1 and ELT-3. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21: 2533–2544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilleard J. S., Shafi Y., Barry J. D., McGhee J. D., 1999. ELT-3: a Caenorhabditis elegans GATA factor expressed in the embryonic epidermis during morphogenesis. Dev. Biol. 208: 265–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glover-Cutter K. M., Lin S., Blackwell T. K., 2013. Integration of the unfolded protein and oxidative stress responses through SKN-1/Nrf. PLoS Genet. 9: e1003701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han S. K., Lee D., Lee H., Kim D., Son H. G., et al. , 2016. OASIS 2: online application for survival analysis 2 with features for the analysis of maximal lifespan and healthspan in aging research. Oncotarget 7: 56147–56152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue H., Hisamoto N., An J. H., Oliveira R. P., Nishida E., et al. , 2005. The C. elegans p38 MAPK pathway regulates nuclear localization of the transcription factor SKN-1 in oxidative stress response. Genes Dev. 19: 2278–2283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itoh K., Wakabayashi N., Katoh Y., Ishii T., Igarashi K., et al. , 1999. Keap1 represses nuclear activation of antioxidant responsive elements by Nrf2 through binding to the amino-terminal Neh2 domain. Genes Dev. 13: 76–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman C. K., Zhou P., Pasolli H. A., Rendl M., Bolotin D., et al. , 2003. GATA-3: an unexpected regulator of cell lineage determination in skin. Genes Dev. 17: 2108–2122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S. K., Budovskaya Y. V., Johnson T. E., 2012. Response to Tonsaker et al. Mech. Ageing Dev. 133: 54–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S. K., Budovskaya Y. V., Johnson T. E., 2013. Reconciliation of daf-2 suppression by elt-3 in Caenorhabditis elegans from Tonsaker et al. (2012) and Kim et al. (2012). Mech. Ageing Dev. 134: 64–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi A., Kang M.-I., Watai Y., Tong K. I., Shibata T., et al. , 2006. Oxidative and electrophilic stresses activate Nrf2 through inhibition of ubiquitination activity of Keap1. Mol. Cell. Biol. 26: 221–229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koon J. C., Kubiseski T. J., 2010. Developmental arrest of Caenorhabditis elegans BRAP-2 mutant exposed to oxidative stress is dependent on BRC-1. J. Biol. Chem. 285: 13437–13443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kops G. J. P. L., Dansen T. B., Polderman P. E., Saarloos I., Wirtz K. W. A., et al. , 2002. Forkhead transcription factor FOXO3a protects quiescent cells from oxidative stress. Nature 419: 316–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S. S., Lee R. Y. N., Fraser A. G., Kamath R. S., Ahringer J., et al. , 2003. A systematic RNAi screen identifies a critical role for mitochondria in C. elegans longevity. Nat. Genet. 33: 40–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehrbach N. J., Ruvkun G., 2016. Proteasome dysfunction triggers activation of SKN-1A/Nrf1 by the aspartic protease DDI-1. Elife 5: e17721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S., Ku C. Y., Farmer A. A., Cong Y. S., Chen C. F., et al. , 1998. Identification of a novel cytoplasmic protein that specifically binds to nuclear localization signal motifs. J. Biol. Chem. 273: 6183–6189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacNeil L. T., Pons C., Arda H. E., Giese G. E., Myers C. L., et al. , 2015. Transcription factor activity mapping of a tissue-specific in vivo gene regulatory network. Cell Syst. 1: 152–162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann F. G., Van Nostrand E. L., Friedland A. E., Liu X., Kim S. K., 2016. Deactivation of the GATA transcription factor ELT-2 is a major driver of normal aging in C. elegans. PLoS Genet. 12: e1005956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matheny S. A., Chen C., Kortum R. L., Razidlo G. L., Lewis R. E., et al. , 2004. Ras regulates assembly of mitogenic signalling complexes through the effector protein IMP. Nature 427: 256–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGhee J. D., 2013a Reply to the second letter from Drs. Kim, Budovskaya and Johnson. Mech. Ageing Dev. 134: 66–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGhee J. D., 2013b The Caenorhabditis elegans intestine. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Dev. Biol. 2: 347–367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moi P., Chan K., Asunis I., Cao A., Kan Y. W., 1994. Isolation of NF-E2-related factor 2 (Nrf2), a NF-E2-like basic leucine zipper transcriptional activator that binds to the tandem NF-E2/AP1 repeat of the beta-globin locus control region. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91: 9926–9930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molkentin J. D., 2000. The zinc finger-containing transcription factors GATA-4, -5, and -6. Ubiquitously expressed regulators of tissue-specific gene expression. J. Biol. Chem. 275: 38949–38952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukhopadhyay A., Deplancke B., Walhout A. J. M., Tissenbaum H. A., 2008. Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) coupled to detection by quantitative real-time PCR to study transcription factor binding to DNA in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nat. Protoc. 3: 698–709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okuyama T., Inoue H., Ookuma S., Satoh T., Kano K., et al. , 2010. The ERK-MAPK pathway regulates longevity through SKN-1 and insulin-like signaling in Caenorhabditis elegans. J. Biol. Chem. 285: 30274–30281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira R. P., Porter Abate J., Dilks K., Landis J., Ashraf J., et al. , 2009. Condition-adapted stress and longevity gene regulation by Caenorhabditis elegans SKN-1/Nrf. Aging Cell 8: 524–541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paek J., Lo J. Y., Narasimhan S. D., Nguyen T. N., Glover-Cutter K., et al. , 2012. Mitochondrial SKN-1/Nrf mediates a conserved starvation response. Cell Metab. 16: 526–537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reece-Hoyes J. S., Deplancke B., Shingles J., Grove C. A., Hope I. A., et al. , 2005. A compendium of Caenorhabditis elegans regulatory transcription factors: a resource for mapping transcription regulatory networks. Genome Biol. 6: R110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rockwell C. E., Zhang M., Fields P. E., Klaassen C. D., 2012. Th2 skewing by activation of Nrf2 in CD4(+) T cells. J. Immunol. 188: 1630–1637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki T., Yamamoto M., 2015. Molecular basis of the Keap1-Nrf2 system. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 88: 93–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tonsaker T., Pratt R. M., McGhee J. D., 2012. Re-evaluating the role of ELT-3 in a GATA transcription factor circuit proposed to guide aging in C. elegans. Mech. Ageing Dev. 133: 50–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Troemel E. R., Chu S. W., Reinke V., Lee S. S., Ausubel F. M., et al. , 2006. p38 MAPK regulates expression of immune response genes and contributes to longevity in C. elegans. PLoS Genet. 2: e183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tullet J. M. A., Hertweck M., An J. H., Baker J., Hwang J. Y., et al. , 2008. Direct inhibition of the longevity-promoting factor SKN-1 by insulin-like signaling in C. elegans. Cell 132: 1025–1038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson D. S., Taylor R. C., Dillin A., 2012. Analysis of aging in Caenorhabditis elegans. Methods Cell Biol. 107: 353–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Strains are available upon request or through the Caenorhabditis Genetics Center. All the data necessary for confirming the conclusions presented in the article are represented fully within the article and Supplemental Material.