Short abstract

The use of conceptual models can help to bridge the gap between research findings and policy development, illustrated here by the complex area of primary care mental health services

The trend is towards greater use of research evidence (especially systematic reviews) in the development of health policy. However, systematic reviews have traditionally been designed for clinical decision making, and linking such evidence to the broader perspectives and goals of policy makers is complex.1 In such cases, conceptual models are often useful. Models are abstract representations of complex areas—“inventions of the human mind to place facts, events and theories in an orderly manner.”2 We will attempt to illustrate the way in which such models can assist in the application of evidence from systematic reviews to policy, using the example of mental health care in primary care.

Models of primary care mental health

Mental health problems are an important source of burden worldwide, and a key recommendation of the World Health Organization is that treatment should be based in primary care.3 Mental health care in primary care has been defined as “the provision of basic preventive and curative mental health care at the first point of contact of entry into the health care system.”4

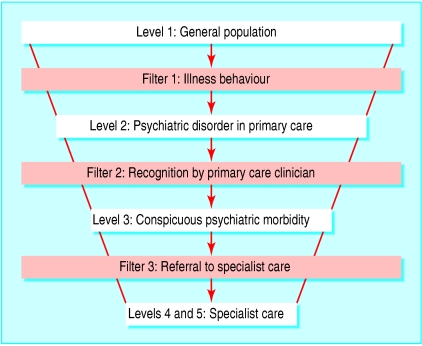

The structure of mental health care in primary care is generally understood in terms of the “pathways to care” model.5 Accessing mental health care involves passing through five levels and three filters between the community and specialist care (fig 1). This model highlights the importance of the primary care clinician, whose ability to detect disorder in presenting patients (filter 2) and propensity to refer (filter 3) represent key barriers to care. The model also highlights the decreasing proportion of the total population who access higher levels.

Fig 1.

Pathways to care model

A wide range of mental health problems present in primary care, and the table shows a useful typology.6 A distinction is often made between “severe and long term mental health disorders” (type 1 in the table) and “common mental health disorders” (types 2-4). Although primary care has an important role to play in the management of more severe disorders, common disorders are generally viewed as the main remit of primary care and are the current focus. As can be seen in the table, each type may be amenable to different treatments (such as general support, drug treatment, and psychological therapy), and these different treatments are available at different levels of the pathways to care model. For example, drug treatment is available at level 3, whereas more complex psychological therapies are generally restricted to level 4.

Table 1.

Typology of mental health disorders in primary care6

| Type | Description | Example disorders | Current care |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Severe mental disorders, unlikely to remit spontaneously, associated with major disability | Schizophrenia, organic disorders, bipolar disorder | Involves both primary and secondary care |

| 2 | Well defined disorders, associated with disability, for which there are effective pharmacological and psychological treatments. Disorders may remit, but relapse is common | Anxious depression, pure depression, generalised anxiety, panic disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder | Can usually be managed entirely within primary care |

| 3 | Disorders in which drugs have a more limited role, but for which psychological therapies are available | Phobias, somatised presentations of distress, eating disorder, chronic fatigue | Rarely treated within primary care; only a small proportion of cases are treated by specialist services |

| 4 | Disorders that tend to resolve spontaneously | Bereavement, adjustment disorder | Supportive help, rather than a specific mental health skill, is needed |

Goals of mental health care in primary care

Given these models of service structure and burden, what are primary care mental health services supposed to achieve? The first two aims are the focus of conventional systematic reviews:

Effectiveness—services should improve health and wellbeing

Efficiency—limited resources should be distributed to maximise health gains to society.

Other aims are also important, however, and are highlighted by the pathways to care model but less often dealt with explicitly in systematic reviews:

Access—service provision should meet the need for services in the community

Equity—resources should be distributed according to need.

Models of quality improvement in primary care mental health

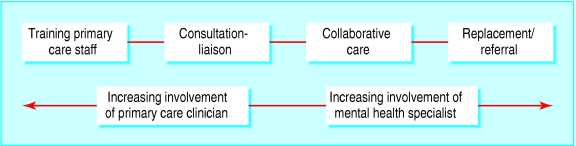

Policy makers are faced with a huge number of disparate interventions intended to improve quality. To reduce this complexity, we describe four “models,” which represent qualitatively different ways of improving quality.7-9 These are abstractions designed to capture key dimensions of the models rather than the complex and idiosyncratic ways in which they might be implemented in clinical contexts.

Training primary care staff—This involves the provision of knowledge and skills concerning mental health care to primary care clinicians.4 It might involve improving prescribing or providing skills in psychological therapy. Training can involve widespread dissemination of information and guidelines or more intensive practice based education seminars.

Consultation-liaison—This is a variant of the training model but involves mental health specialists entering into an ongoing educational relationship with primary care clinicians, to support them in caring for individual patients.7 Referral to specialist care is needed in a small proportion of cases.

Collaborative care—Collaborative care can involve aspects of both training and consultation-liaison but also includes the addition of new quasi-specialist staff (so called case managers) who work with patients and liaise with primary care clinicians and specialists in order to improve quality of care.8 Often based on the principles of chronic disease management, this model may also involve screening, education of patients, changes in practice routines, and developments in information technology.10

Replacement/referral—In this model the primary responsibility for the management of the presenting problem is passed to the specialist for the duration of treatment. This model is most often associated with psychological therapy.

In the United Kingdom, quality improvement activities in the past decade have focused on two of these models. “Top down” policy drivers have focused on the training model, reflected in the “Defeat Depression” campaign. “Bottom up” quality improvement driven by practitioners has generally focused on increasing use of the replacement/referral model (for example, the rise of counselling and other psychological therapy services).

These models can be ordered along a key dimension relating to the importance of the primary care clinician in the management of mental health problems and the degree to which the model focuses on improving their skills and confidence (fig 2). The primary care clinician has the greatest involvement in the training model, and that involvement decreases in the consultation-liaison, collaborative care, and replacement/referral models.

Fig 2.

Models of mental health care in primary care

The degree of involvement of the primary care clinician provides a link between quality improvement models, the pathways to care model, and goals such as access and equity. Assuming equivalent effectiveness, models that put greater focus on increasing the abilities of primary care clinicians have the greatest potential impact on access and equity. This is because these models can most readily influence filter 2 and treatment at level 3, which can potentially influence the largest numbers of patients (that is, all patients with common mental health problems presenting in primary care). In contrast, models that require considerable specialist involvement at the level of the individual patient (such as collaborative care and replacement/referral) can affect the smaller proportion of patients who pass filter 3.

Integrating conceptual models with the evidence base

To examine the relation between conceptual models and the evidence base, we did a meta-review—that is, a review of all available reviews of the evidence. This approach has already been used in two previous reviews of UK mental health,11,12 and although not as comprehensive as a primary systematic review, it provides a useful overview of the evidence.

We used the Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects and the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews as the primary source of reviews. We also searched Medline, Embase, CINAHL, and PsycINFO for recently published reviews not included in the primary sources at the time of the search, as well as searching our personal reference lists. The electronic search strategy is available from the authors. The included reviews are presented on bmj.com together with a simple summary of the results and an assessment of quality made using standardised criteria.13 The results are described below.

Training

We identified two high quality reviews on training. One review reported that most types of training (such as passive dissemination of guidelines and short term courses) were ineffective in improving outcome in patients.w1 w2 The other review examined the effects of more intensive training in psychosocial interventions for general practitioners and found more consistent evidence of benefit.w3

Consultation-liaison

We identified two reviews of consultation-liaison. Limited and inconsistent evidence existed to show that consultation-liaison can affect the behaviour of primary care clinicians,w4 w5 but there was no clear evidence that such benefits could be generalised to the wider practice population.w4 w5 Another lower quality review identified two studies, both of which failed to show any benefit on outcome in patients.w6

Collaborative care

We identified five reviews of collaborative care.w1 w2 w7-w10 Although the exact definition of the intervention varied, all five reviews reported relatively consistent evidence of clinical effectiveness. One high quality review reported standardised effect sizes,w8 which suggested that collaborative care showed small to medium effects on health status, patient satisfaction, and compliance according to conventional criteria. Limited information was available on cost effectiveness, but one review reported that collaborative care was generally more effective and more costly.w8 No consistent pattern of effectiveness existed with respect to methodological quality.

Replacement/referral

We identified eight reviews of replacement/referral, which were of variable quality.w4 w6 w11-w18 The reviews involved several different psychological therapies provided by a range of professionals. Most of the reviews reported that replacement/referral models were generally clinically effective, at least in the short term, with effects potentially moderated by the type of therapy and patients. The effect size reported in two reviews was small to medium in magnitude.w11 w12 w16 We found no consistent pattern of effectiveness with respect to methodological quality.

Conclusions

What are the overall implications of the meta-review for policy makers? Clearly, insufficient evidence exists to provide a definitive answer as to the clinical effectiveness and cost effectiveness of individual models and their impact on access and equity or to provide a rigorous comparison between models. All the reviews reported problems with the quality of the included studies, and the amount of evidence available for some models (such as consultation-liaison) is limited. Continuing evaluation of these models and new ways of providing them (for example, primary care mental health workers) is essential. The meta-review does, however, have an important function in challenging assumptions about quality improvement in primary care mental health services and in highlighting key issues for the future.

Summary points

Applying evidence from systematic reviews to policy and service development is important, but several practical barriers exist

Barriers include the gap between the narrow focus of research studies and the broader perspectives of policy makers

Conceptual models are abstract representations of complex issues; they can simplify issues and more clearly highlight the relation between particular research studies and the broader context

This paper shows the application of conceptual models concerning service structure, burden, and quality improvement in the context of mental health care in primary care

The application of conceptual models may help bridge the gap between the results of research and the needs of policy makers

It was nearly 40 years ago that Shepherd argued that “administrative and medical logic alike therefore suggest that the cardinal requirement for improvement of the mental health services in this country is not a large expansion and proliferation of psychiatric agencies, but rather a strengthening of the family doctor in his therapeutic role.”14 The advantages of the training model in terms of access and equity have been described earlier, and Shepherd's statement remains true in principle. However, although some evidence exists for the effectiveness of training interventions, overall the impact is inconsistent. The difference in the results of the two reviews of training suggests that the training model may be limited by the paradox that training that is feasible within current educational structures (such as guidelines and short training courses) is not effective, whereas more intensive training is effective but may not be feasible.15 The role of training models cannot be dismissed, however. Educational interventions might need to be delivered in the context of other effective mechanisms, such as financial incentives.16

The reviews of collaborative care and replacement/referral models were in agreement that such models are generally effective in improving outcomes, but their limitations must be considered. Collaborative care interventions often involve drug treatment, have generally been tested on patients with more severe disorders, and focus on patients at risk of relapse and recurrence. They may therefore be relevant for only a proportion of patients and may be less relevant for patients who have problems of type 3 and type 4. Equally, both collaborative care and replacement/referral models rely on mental health specialists (fig 2), which means that limitations in the workforce may further limit their impact on access and equity goals. The current interest in self help and stepped care is one way of achieving the effectiveness of the replacement/referral model without limiting access,17 and similar interest exists in the use of non-mental health staff (such as practice nurses) as case managers in collaborative care models. However, the degree to which these improvements in access are achievable without loss of effectiveness is unclear.

In conclusion, conceptual models can assist in the interpretation of evidence in a policy context. Future research may seek to formally link systematic review evidence with conceptual models through decision analytic modelling,18 which may provide a more solid bridge between the evidence and the policy context.

Supplementary Material

A summary of the reviews included and extra references are on bmj.com

A summary of the reviews included and extra references are on bmj.com

Contributors and sources: PB and SG are health services researchers with extensive experience in the application of systematic review methods to policy in mental health. This paper draws together previously published conceptual and empirical reviews in this area. Both authors were involved in the conception and design of the study, data extraction, and writing of the paper. PB is the guarantor of the paper.

Funding: The National Primary Care Research and Development Centre is funded by the Department of Health, but the views expressed in the paper are those of the authors alone.

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Black N. Evidence based policy: proceed with care. BMJ 2001;323: 275-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siegler M, Osmond H. Models of madness, models of medicine. New York: Macmillan, 1974.

- 3.World Health Organization. The world health report 2001—mental health: new understanding, new hope. Geneva: WHO, 2001.

- 4.World Health Organization. ATLAS: mental health resources in the world 2001. Geneva: WHO, 2001.

- 5.Goldberg D, Huxley P. Mental illness in the community: the pathway to psychiatric care. London: Tavistock, 1980.

- 6.Goldberg D, Gournay K. The general practitioner, the psychiatrist and the burden of mental health care. London: Maudsley Hospital, Institute of Psychiatry, 1997.

- 7.Gask L, Sibbald B, Creed F. Evaluating models of working at the interface between mental health services and primary care. Br J Psychiatry 1997;170: 6-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Katon W, Von Korff M, Lin E, Simon G. Rethinking practitioner roles in chronic illness: the specialist, primary care physician and the practice nurse. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2001;23: 138-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pincus H. Patient-oriented models for linking primary care and mental health care. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 1987;9: 95-101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wagner E, Austin B, Von Korff M. Organizing care for patients with chronic illness. Milbank Q 1996;74: 511-43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Department of Health. Treatment choice in psychological therapies and counselling: evidence based clinical practice guideline. London: Department of Health, 2001.

- 12.Centre for Reviews and Dissemination. Scoping review of the effectiveness of mental health services. York: University of York, Centre for Reviews and Dissemination, 2001.

- 13.Oxman A, Guyatt G. Guidelines for reading review articles. Can Med Assoc J 1988;138: 697-703. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shepherd M, Cooper B, Brown A, Kalton G. Psychiatric illness in general practice. London: Oxford University Press, 1966.

- 15.Kendrick T. Why can't GPs follow guidelines on depression? BMJ 2000;320: 200-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shekelle P. New contract for general practitioners. BMJ 2003;326: 457-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lovell K, Richards D. Multiple access points and levels of entry (MAPLE): ensuring choice, accessibility and equity for CBT services. Behav Cognit Psychother 2000;28: 379-91. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Valenstein M, Vijan S, Zeber J, Boehm K, Buttar A. The cost-utility of screening for depression in primary care. Ann Intern Med 2001;134: 345-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.