Abstract

Receptor-interacting protein 140 (RIP140) is best known for its functional role as a wide-spectrum transcriptional co-regulator. It is highly expressed in metabolic tissues including mature adipocyte. In the past decade, molecular biological and biochemical studies revealed extensive and sequential post-translational modifications (PTMs) of RIP140. Some of these PTMs affect RIP140’s sub-cellular distribution and biological activities that contribute to the development and progression of metabolic diseases. The biological activity of RIP140 that translocates to the cytoplasm in adipocytes is to regulate glucose uptake, adiponectin secretion and lipolysis. Accumulation of RIP140 in the cytoplasm promotes adipocyte dysfunctions, and provides a biomarker of early stages of metabolic diseases. Administering compounds that reduce cytoplasmic accumulation of RIP140 in high fat diet-fed animals can ameliorate metabolic dysfunctions, manifested in improving insulin sensitivity and adiponectin secretion, and reducing incidences of hepatic steatosis. This review summarizes studies demonstrating RIP140’s PTMs and biological activities in the cytoplasm of adipocyte, signaling pathways stimulating these PTMs, and a proof-of-concept that targeting cytoplasmic RIP140 can be an effective strategy in managing metabolic diseases.

Keywords: RIP140, Post translational modification (PTM), Adipocyte, Type II diabetes mellitus (T2DM), Endothelin-1 (ET-1), Ambresentan, GLUT4, Adiponectin, Nuclear translocation, Biomarker, Therapeutics

INTRODUCTION

Adipocyte Dysfunctions and Metabolic Disorders

Metabolic syndrome, also known as syndrome X, presents one of the most challenging health issues in the modern society. Patients with metabolic syndrome tend to have multiple metabolic and inflammatory disorders, including type II diabetes mellitus (T2DM), atherosclerosis, hypertension, cardiomyopathy, rheumatoid arthritis and Alzheimer’s diseases [1–3]. The main features of metabolic syndrome include the decrease in circulating HDL and the increase in circulating triglyceride (TG), low density lipoprotein (LDL) and fasting blood glucose (4). Epidemiological and etiological analyses reveal that obesity is the major trigger for metabolic syndrome. Mechanistically, it is known that the enlarged and dysfunctional adipose tissues play a critical role in aggravating metabolic disorders [1, 5].

Adipose tissues, initially considered as inert tissues that merely store energy as TG, consist of two major types, white (WAT) and brown (BAT) adipose tissues, that have distinct functions in modulating whole body metabolism and energy homeostasis. BAT has higher mitochondrial activities and expresses marginally detectable levels of RIP140. Upon exposure to a low temperature, BAT utilizes TG to produce heat and maintain body temperature. Conversely, WAT stores energy after food intake and expresses much higher levels of RIP140. The stored energy is usually utilized during fasting, through TG hydrolysis [1, 6], to release glycerol and free fatty acids. Released fatty acids provide energy for other tissues and can produce ketone body in the liver. In addition to storing and utilizing lipid, there are also important metabolic processes occurred in adipocytes. For instance, insulin can promote glucose transporter 4 (GLUT4) trafficking to facilitate glucose uptake in adipocytes. In fact, insulin-stimulated glucose uptake in adipocytes is vital to the maintenance of systemic insulin sensitivity [7]. To this end, a defect in GLUT4 trafficking or loss of GLUT4 expression in adipocytes can also induce systemic insulin resistance in muscle and liver, which results in diabetes [1, 7]. Additionally, adipocytes, mainly white adipocytes, can secret various cytokines such as adiponectin, resistin, and leptin to modulate multiple physiological processes including systemic insulin sensitivity, glucose and lipid metabolism, inflammatory potential, and animal behavior [1, 8–10]. Adiponectin can elevate systemic insulin sensitivity, improve endothelial function, and produce anti-inflammatory effects - all are protective against the development of metabolic and cardiovascular diseases (e.g., cardiac hypertrophy, ischemic heart disease and heart failure) [9, 11, 12]. Leptin can down regulate appetite, exacerbate inflammatory response, modulate bone mass, and affect puberty [13, 14].

Dysfunctions in adipocyte could be detrimental because of the potential to damage a wide spectrum of physiological processes. High caloric diet-induced adipocyte dysfunctions include reduced glucose uptake, increased release of free fatty acids, and dramatic changes in their secreted adipokine profiles [1]. In obese individuals and patients of T2DM, adiponectin secretion is decreased but leptin secretion is increased despite the increase in their adipose tissue mass, which further aggravates disease progression [1]. Disturbing adipocyte lipid storage and glucose uptake can elevate systemic insulin resistance and elicit lipotoxicity in liver and muscle [1, 15, 16]. Deregulating lipolysis can dampen cardiac function by increasing aberrant lipid deposition in cardiomyocytes. The accumulation of lipid in heart eventually causes lipotoxic cardiomyopathy, one metabolic disorder with a high mortality [5, 16, 17]. All these studies show that maintaining normal functions of adipocytes is vital to the homeostatic control of metabolism, behavior, and cardiovascular functions. An interesting theory suggests that obesity, which usually is associated with enlarged adipocytes, may reflect the adaptation of the system to reduce lipotoxicity and can be protective because it may reduce over-nutrition induced metabolic burden [16, 18]. However, after prolonged morbid obesity, adipocytes reduce the ability to store TG and uptake glucose, and alter their secreted adipokine profiles, thereby contributing to the development of metabolic diseases.

The Physiological Role of RIP140

Receptor-interacting protein 140 (RIP140), also known as receptor interacting protein 1 (NRIP1) was initially identified as a coregulatory protein of estrogen receptor α (ERα) and orphan nuclear receptor TR2 [19–21]. Subsequently, RIP140 was found to interact with a wide spectrum of transcription factors including all the nuclear receptors tested. In most of these studies, RIP140 was shown to exert a corepressive activity for target gene transcription, primarily by recruiting repressive co-regulatory molecules such as HDAC3, CtBP and CDK8 [22–24]. In contrast, several studies showed that RIP140 could also act as a transcription coactivator, most notably for NF-kB’s activation of proinflammatory cytokine production in macrophages [25, 26]. RIP140 expression was detected mainly in ovary, heart and metabolic tissues such as adipose, muscle, and liver. In adipocytes, RIP140 was found to repress the expression of UCP1 and GLUT4 to reduce mitochondria activity and glucose uptake, respectively [27, 28], and to increase the expression of key lipogenic enzymes to promote lipogenesis [27, 29]. The physiological role for RIP140 in ovulation and metabolism was demonstrated in studies using RIP140-null mice. These whole body RIP140 knockout mice were defected in ovulation and resistant to high-fat diet (HFD)-induced T2DM and associated metabolic disorders [27, 30–32]. Interestingly, RIP140 appeared to also regulate gluconeogenesis and lipid storage in hepatocytes, could be involved in the metabolic response during starvation and in cancer cachexia [33], and might affect skeletal muscle and cardiac muscle metabolism to modulate muscle strength and cardiac functions [2, 34]. All these studies suggest that RIP140 is involved in diet-induced diabetes and metabolic diseases through its nuclear activity in adipocytes, liver and muscle.

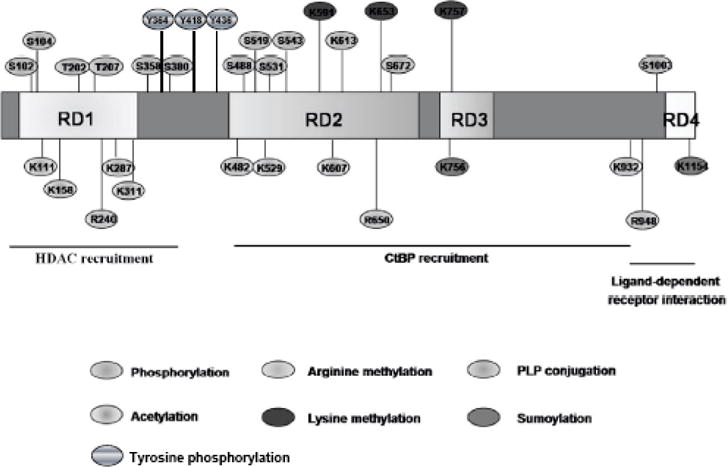

A systemic mass-spectrometry investigation revealed surprisingly complex post translational modifications (PTMs) of RIP140. The PTMs of RIP140 include phosphorylation, acetylation, methylation, PLP conjugation, ubiquitination, and sumoylation [31, 35–43], which can modulate its gene regulatory activity, protein stability, cellular distribution, and/or interacting partners (Fig. 1 and Table 1) [31, 44]. These PTMs can be categorized into two principal pathways, one is to stimulate RIP140 nuclear export and cytoplasmic activities and the second is to enhance RIP140 nuclear retention and its gene regulatory activities (Fig. 2). Conceivably, signaling pathways that elicit these PTMs of RIP140 can modulate normal adipocyte functions. This review summarizes those PTMs related to RIP140‘s cytoplasmic distribution and activities in adipocytes, as well as signaling pathways triggering these PTMs. The pathophysiological manifestation of these PTMs is reviewed with a particular focus on the development of metabolic diseases.

Fig. (1).

Schematic illustration of post-translational modifications (PTMs) of RIP140. The boxes indicate the full length RIP140 with repressive domains 1 to 4 (RDs 1–4).

Table 1.

Post-translational Modifications of RIP140

| Modification | Residues | Enzyme | Function |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Phosphorylation | S102, S1003 | PKCε | Nuclear export |

| T202, T207 | Erk2 | Transrepression | |

| S104, S358, S380, S488 | ? | ? | |

| S519, S531, S543, S672 | |||

| Y364, Y418, Y436 | Sky | Ubiquitination | |

|

| |||

| Methlation | R240, R650, R948 P | PRMT1 | Nuclear export |

| K591, K653, K757 | ? | Transrepression | |

|

| |||

| Acetylation | K158, K287 | P300 | Transrepression |

| K111, K311, K482, K529 | ? | ? | |

| K 687, K932 | |||

|

| |||

| PLP conjugation | K613 | ? | Transrepression |

|

| |||

| Sumoylation | K757, K1157 | ? | Transrepression |

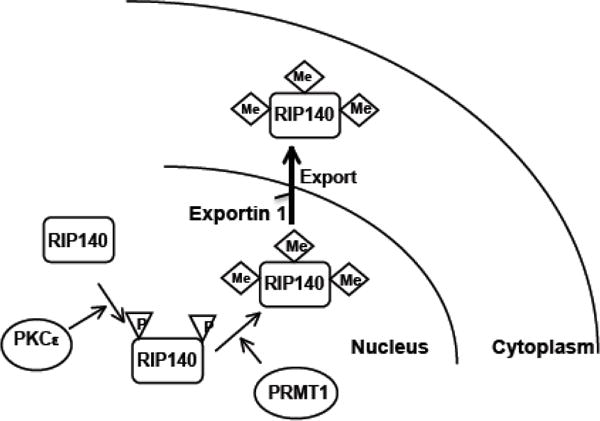

Fig. (2).

Sequential phosphorylation then methylation promotes nuclear export of RIP140. Activated nuclear PKCe phosphorylates RIP140 on Ser-102 and Ser-1003. Phosphorylation on RIP140 then facilitates its recruiting PRMT1 through the action of 14-3-3. The associated PRMT1 triggers arginine methylation on Arg-240, Arg-650, and Arg-948. The arginine-methylated RIP140 recruits exportin-1, leading to nuclear export of RIP140.

Cellular Signaling to Promote Nuclear Export of RIP140

There are various forms of PTMs that could occur on RIP140. Among these, a cascade of sequential PTMs is specifically responsible for RIP140’s nuclear export, or cytoplasmic accumulation, in adipocytes. This pathway is initiated from nuclear PKCε-mediated phosphorylation on Ser-102 and Ser-1003 of RIP140 in the nuclei, which triggers 14-3-3-dependent recruitment of protein arginine methyl transferase 1 (PRMT1) that methylates Arg240, Arg650, and Arg948 of RIP140 [19, 20]. After arginine methylation, the modified RIP140 is then exported to the cytoplasm by associating with exportin 1. It appears that, along 3T3-L1 adipocyte differentiation processes, RIP140 expression is gradually elevated and increasingly exported to the cytoplasm, in consistence with the increase in its serine phosphorylation followed by subsequent arginine methylation [40]. The functional relevance of these enzymes was demonstrated by silencing or inhibiting PKCε or PRMT1, which reduced the cytoplasmic RIP140 level by enhancing its nuclear retention, resulting in increased lipid accumulation in adipocytes.

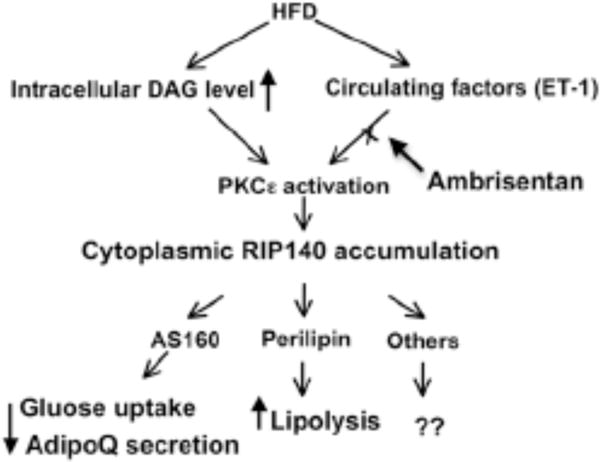

In mice, HFD feeding could increase nuclear PKCε activity, which elevates the cytoplasmic RIP140 level in epididymal adipose tissue [45]. This may be due to accumulated intracellular DAG that stimulates PKCε [46], the principal trigger for RIP140’s nuclear export pathway. This is supported by the finding that a DAG kinase inhibitor (that blocks DAG catabolism to elevate DAG level) could enhance RIP140 accumulation in the cytoplasm [26]. In addition to intrinsic signals like intracellular lipid accumulation, circulating endothelin-1 (ET-1) can also provide an extrinsic signal to activate PKCε in adipocytes (Fig. 2) [26, 47]. ET-1, the most potent vasoconstrictor secreted by endothelial cells, regulates important biological processes such as wound healing and regulation of blood vessel tone. ET-1 is the major therapeutic target in managing pulmonary hypertension and pulmonary fibrosis [48–50]. Clinically, obese and T2DM patients have higher levels of circulating ET-1. Several studies have suggested that elevated circulating ET-1 might contribute to adipocyte dysfunctions [50–52]. In agreement with these suggestions, we have demonstrated that ET-1 indeed stimulates the accumulation of RIP140 in the cytoplasm of adipocytes [47]. It appears that after binding to ETA receptor on adipocytes, ET-1 activates PLCβ to produce DAG, which activates nuclear PKCε [47]. Accordingly, targeting either PLCβ or PKCε by inhibitors or siRNAs can effectively diminish ET-1-induced accumulation of RIP140 in the cytoplasm of adipocytes. Importantly, we have demonstrated that a clinically approved ETA antagonist, ambrisentan, effectively blocks the accumulation of cytoplasmic RIP140 in primary epididymal adipose tissues in HFD-fed mice and abrogates the progression of metabolic syndromes in these animals (see the following section). Altogether, these studies demonstrated two major pathways that can stimulate RIP140’s nuclear export: intrinsic and extrinsic pathways. The intrinsic pathway is initiated by the accumulation of intracellular lipid content, especially the DAG level, whereas the extrinsic pathway is elicited by circulating ET-1. Both pathways utilize nuclear PKCε to promote the accumulation of RIP140 in the cytoplasm, supporting PKCε-PRMT1 as the principal pathway to modulate RIP140’s nuclear export in vitro and in vivo. In addition to ET-1, several inflammatory cytokines such as RANTES and CCL5 can also activate PLCβ [53, 54]. Therefore, inflammatory cytokines may also stimulate nuclear export of RIP140 to affect adipocyte functions.

Functions of Cytoplasmic RIP140 in Adipocytes

In studies using ultracentrifugation to separate subcellular fractions of adipocytes, RIP140 was detected in fractions of nucleus, cytosol, endoplasmic reticulum and lipid droplet, but not in mitochondria. This result was supported in immunochemical analyses of adipocytes co-labeled with markers of specific organelles [26]. The pattern of sub-cellular distribution of RIP140 in adipocytes suggests that RIP140 may interact with a wide spectrum of proteins to exert distinct functions in different subcellular locations (Fig. 3). By examining RIP140-interacting proteins identified from a yeast two hybrid screening, we have determined an important functional role for RIP140 in adipocytes, mediated by its interacting with an Akt substrate AS160 [45]. AS160, a GTPase-activating protein (GAP), can dampen vesicle transport, docking and tethering by inactivating different Rab GTPases. AS160’s activity can be blocked by Akt-mediated phosphorylation [7, 45, 55], which is negated by its interacting with RIP140 (see following). In adipocytes, GLUT4 transporter is carried in specialized vesicles (GLUT4 vesicles) whose trafficking to plasma membrane can be inhibited by AS160 in resting cells. Upon insulin stimulation, Akt is activated to phosphorylate AS160 whose activity (inactivating Rab GTPases) is then inhibited, which leads to a robust increase in GLUT4 vesicle trafficking [7, 55]. Relevant to this pathway, cytoplasmic RIP140 competes with Akt for AS160 binding, rendering hypo-phosphorylation of AS160 even after insulin stimulation, which maintains AS160 activity to impede GLUT4 vesicle trafficking and glucose uptake [45]. In agreement with this result, RIP140-null adipocytes rescued with a mutated RIP140 that could not be exported to the cytoplasm have increased glucose uptake, as compared to RIP140-null adipocytes rescued with the wild-type RIP140. Since a short-term HFD readily stimulates RIP140’s nuclear export in adipocytes, the accumulation of RIP140 in the cytoplasm may in fact indicate an early, pre-diabetic condition that impedes adipocytes’ normal functions.

Fig. (3).

HFD-induced accumulation of RIP140 in the cytoplasm and the biological activities of cytoplasmic RIP140 in adipocytes. HFD-feeding elevates circulating ET-1 and DAG levels. Increase in ET-1 and intracellular DAG activates PKCe, initiating the signaling pathway to stimulate nuclear export of RIP140. In the cytoplasm, RIP140 can interact with AS160 to block the traffic of GLUT4 and adiponectin vesicles. Cytoplasmic RIP140 can also interact with perilipin on the surface of lipid droplets to increase lipolysis. Ambrisentan blocks ET-1 signal to reduce RIP140’s accumulation in the cytoplasm, thereby lessening the severity of HFD-induced metabolic diseases.

Another function of RIP140 is to decrease adiponectin secretion. Adiponectin is stored in trafficking adiponectin vesicles around the trans-Golgi networks (TGNs); trafficking of these vesicles is also stimulated by insulin [11]. Cytoplasmic RIP140 also retards adiponectin secretion from adipocytes [56]. Interestingly, this inhibition is not caused by ER retention or changes in disulfide bond formation for adiponectin oligomers. Rather, cytoplasmic RIP140 inhibits adiponectin secretion by maintaining AS160 activity that also modulates the traffic of adiponectin vesicles. Therefore, by interacting with AS160, cytoplasmic RIP140 can reduce adiponectin secretion and GLUT4 vesicle trafficking. However, the specific Rabs regulating adiponectin vesicles remain to be determined [55].

The third cytoplasmic function of RIP140 in adipocytes is exerted through its association with lipid droplets (LDs) via direct interaction with perilipin A [26]. Perilipin A, a structural protein of lipid droplets, can regulate the formation of LDs. By interacting with perilipin A, RIP140 promotes lipolysis through recruiting hormone-sensitive lipase (HSL) to LDs and releasing the comparative gene identification-58 (CGI-58), an activator of adipose triglyceride lipase (ATGL), to activate ATGL. These dynamic changes in molecular interactions result in increased substrate availability for HSL and the activation of ATGL. As such, nuclear RIP140 acts to promote lipogenesis in differentiating adipocytes; but in fully differentiated adipocytes, RIP140 leaves the nucleus, rendering reduced lipogenesis [38–40]. Furthermore, the accumulation of RIP140 in the cytoplasm would promote lipolysis to further reduce the lipid contents. RIP140 located to the cytoplasm also impedes glucose uptake, which would decrease the available carbon source for lipogenesis and further contribute to diminished lipid accumulation. Therefore, the net outcome of exporting RIP140 from the nucleus to the cytoplasm in adipocytes is to reduce their overall lipid load, which could be important for their survival and in maintaining normal functions. It would be interesting to determine whether cytoplasmic RIP140 may modulate adipocytes’ survival.

Cytoplasmic RIP140 as A New Therapeutic Target in Managing Metabolic Diseases

HFD feeding stimulates RIP140’s accumulation in the cytoplasm of adipocytes through both intrinsic (intracellular lipid content) and extrinsic (circulating ET-1) stimulations; the cytoplasmic RIP140 could dampen glucose uptake and adiponectin secretion and increase lipolysis. As such, the accumulation of RIP140 in the cytoplasm of adipocytes may serve as a biomarker of early stages of metabolic disease. Accordingly, reducing cytoplasmic RIP140 in adipocytes might be beneficial. To provide a proof-of-concept, we have shown that a clinically approved drug that blocks ET-1 signaling, ETA antagonist ambrisentan, can substantially reduce HFD-induced cytoplasmic accumulation of RIP140 in their epididymal adipose tissues [47]. Further, primary adipocytes from ambrisentan-treated mice are more efficient in glucose uptake, and these animals have higher concentrations of circulating adiponectin, fewer inflammatory signs (such as crown like structures) in their epididymal adipose tissues, better glucose tolerance, and fewer incidences of liver steatosis, as compared to the placebo control (saline) or the control treatment (hydralazine) [47]. This study demonstrates the benefit of blocking nuclear export of RIP140 to prevent and manage diet-induced diabetes and other metabolic disorders. However, it remains to be determined whether ETA agonists would enhance lipid accumulation by retaining nuclear RIP140. A better understanding of the control of nuclear export of RIP140 could be helpful to the design of therapeutic drugs that may modify the disease course of metabolic syndromes related to adipocyte dysfunctions and uncontrolled lipogenesis. Novel drugs may be developed to harness the benefits of increasing lipid loads with reduced detrimental effects such as lipolysis and insulin resistance in adipocytes.

CONCLUSION

RIP140 plays important roles in metabolism and can contribute to the development of metabolic diseases [25, 26, 28, 30, 31, 45]. Recent studies have further revealed surprisingly complicated PTMs of RIP140, as well as complex signaling pathways leading to these PTMs. Of particular significance is the wide spectrum of biological consequences elicited by these PTMs. To this end, accumulation of RIP140 in adipocyte cytoplasm can be detrimental because of its effects on multiple processes aggravating the severity of metabolic diseases, such as reducing glucose uptake and adiponectin secretion and increasing lipolysis. Since PTMs of RIP140 in adipocytes are triggered by alterations in the pathophysiological and/or nutritional status, drugs targeting any step in the signaling cascades triggering these PTMs could be useful in managing metabolic diseases. However, it is unclear whether RIP140 can be exported to the cytoplasm in other types of cells such as macrophages that also express high levels of RIP140. It is also unclear whether RIP140 could affect cytoplasmic processes in cell types other than adipocytes. Understanding signal specificity in a particular biological context involving RIP140 is vital to the development of therapeutics that could have a greater therapeutic index. It has been suggested that RIP140 antagonizes another metabolic regulator PGC-1; it will be interesting to investigate whether the activity of RIP140 in the cytoplasm can be regulated by PGC-1 and if RIP140 may cooperate with PGC-1 to modulate the metabolic status of adipocytes.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grants DA11190, DK60521, DK060521-O7S1, K02-DA13926, DK54733, DK054733-09S1 and Distinguished McKnight Professorship of University of Minnesota (L.-N. Wei) and AHA predoctoral fellowship to P.-C. Ho.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors(s) confirm that this article content has no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Guilherme A, Virbasius JV, Puri V, Czech MP. Adipocyte dysfunctions linking obesity to insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008 May;9(5):367–77. doi: 10.1038/nrm2391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fritah A, Steel JH, Nichol D, et al. Elevated expression of the metabolic regulator receptor-interacting protein 140 results in cardiac hypertrophy and impaired cardiac function. Cardiovasc Res. 2010 Jun 1;86(3):443–51. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvp418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McInnes IB, Schett G. The pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2011 Dec 8;365(23):2205–19. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1004965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ford ES, Giles WH, Dietz WH. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome among US adults: findings from the third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. JAMA. 2002 Jan 16;287(3):356–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.3.356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leichman JG, Lavis VR, Aguilar D, Wilson CR, Taegtmeyer H. The metabolic syndrome and the heart—a considered opinion. Clin Res Cardiol. 2006 Jan;95(Suppl 1):i134–41. doi: 10.1007/s00392-006-1119-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zimmermann R, Lass A, Haemmerle G, Zechner R. Fate of fat: the role of adipose triglyceride lipase in lipolysis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009 Jun;1791(6):494–500. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2008.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Herman MA, Kahn BB. Glucose transport and sensing in the maintenance of glucose homeostasis and metabolic harmony. J Clin Invest. 2006 Jul;116(7):1767–75. doi: 10.1172/JCI29027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Antoniades C, Antonopoulos AS, Tousoulis D, Stefanadis C. Adiponectin: from obesity to cardiovascular disease. Obes Rev. 2009 May;10(3):269–79. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2009.00571.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dridi S, Taouis M. Adiponectin and energy homeostasis: consensus and controversy. J Nutr Biochem. 2009 Nov;20(11):831–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2009.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Feuerer M. Lean, but not obese, fat is enriched for a unique population of regulatory T cells that affect metabolic parameters. Nat Med. 2009;15:930–9. doi: 10.1038/nm.2002. [10.1038/nm.2002] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kadowaki T, Yamauchi T, Kubota N, Hara K, Ueki K, Tobe K. Adiponectin and adiponectin receptors in insulin resistance, diabetes, and the metabolic syndrome. J Clin Invest. 2006 Jul;116(7):1784–92. doi: 10.1172/JCI29126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Folco EJ, Rocha VZ, Lopez-Ilasaca M, Libby P. Adiponectin inhibits pro-inflammatory signaling in human macrophages independent of interleukin-10. J Biol Chem. 2009 Sep 18;284(38):25569–75. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.019786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee EB. Obesity, leptin, and Alzheimer’s disease. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2011 Dec;1243:15–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2011.06274.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gomez R, Conde J, Scotece M, Gomez-Reino JJ, Lago F, Gualillo O. What’s new in our understanding of the role of adipokines in rheumatic diseases? Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2011 Sep;7(9):528–36. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2011.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gaidhu MP, Anthony NM, Patel P, Hawke TJ, Ceddia RB. Dysregulation of lipolysis and lipid metabolism in visceral and subcutaneous adipocytes by high-fat diet: role of ATGL, HSL, and AMPK. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2010 Apr;298(4):C961–71. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00547.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Unger RH, Scherer PE. Gluttony, sloth and the metabolic syndrome: a roadmap to lipotoxicity. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2010 Jun;21(6):345–52. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2010.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Szczepaniak LS, Victor RG, Orci L, Unger RH. Forgotten but not gone: the rediscovery of fatty heart, the most common unrecognized disease in America. Circ Res. 2007 Oct 12;101(8):759–67. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.160457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang MY, Grayburn P, Chen S, Ravazzola M, Orci L, Unger RH. Adipogenic capacity and the susceptibility to type 2 diabetes and metabolic syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008 Apr 22;105(16):6139–44. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801981105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cavailles V, Dauvois S, L’Horset F, et al. Nuclear factor RIP140 modulates transcriptional activation by the estrogen receptor. EMBO J. 1995 Aug 1;14(15):3741–51. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb00044.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee CH, Chinpaisal C, Wei LN. Cloning and characterization of mouse RIP140, a corepressor for nuclear orphan receptor TR2. Mol Cell Biol. 1998 Nov;18(11):6745–55. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.11.6745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee CH, Wei LN. Characterization of receptor-interacting protein 140 in retinoid receptor activities. J Biol Chem. 1999 Oct 29;274(44):31320–6. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.44.31320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wei LN, Hu X, Chandra D, Seto E, Farooqui M. Receptor-interacting protein 140 directly recruits histone deacetylases for gene silencing. J Biol Chem. 2000 Dec 29;275(52):40782–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M004821200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vo N, Fjeld C, Goodman RH. Acetylation of nuclear hormone receptor-interacting protein RIP140 regulates binding of the transcriptional corepressor CtBP. Mol Cell Biol. 2001 Sep;21(18):6181–8. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.18.6181-6188.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Persaud SD, Huang WH, Park SW, Wei LN. Gene repressive activity of RIP140 through direct interaction with CDK8. Mol Endocrinol. 2011 Oct;25(10):1689–98. doi: 10.1210/me.2011-1072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zschiedrich I, Hardeland U, Krones-Herzig A, et al. Coactivator function of RIP140 for NFkappaB/RelA-dependent cytokine gene expression. Blood. 2008 Jul 15;112(2):264–76. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-11-121699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ho PC, Chuang YS, Hung CH, Wei LN. Cytoplasmic receptor-interacting protein 140 (RIP140) interacts with perilipin to regulate lipolysis. Cell Signal. 2011 Aug;23(8):1396–403. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2011.03.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Christian M, Kiskinis E, Debevec D, Leonardsson G, White R, Parker MG. RIP140-targeted repression of gene expression in adipocytes. Mol Cell Biol. 2005 Nov;25(21):9383–91. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.21.9383-9391.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Powelka AM, Seth A, Virbasius JV, et al. Suppression of oxidative metabolism and mitochondrial biogenesis by the transcriptional corepressor RIP140 in mouse adipocytes. J Clin Invest. 2006 Jan;116(1):125–36. doi: 10.1172/JCI26040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Christian M, White R, Parker MG. Metabolic regulation by the nuclear receptor corepressor RIP140. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2006 Aug;17(6):243–50. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2006.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fritah A, Christian M, Parker MG. The metabolic coregulator RIP140: an update. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2010 Sep;299(3):E335–40. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00243.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mostaqul Huq MD, Gupta P, Wei LN. Post-translational modifications of nuclear co-repressor RIP140: a therapeutic target for metabolic diseases. Curr Med Chem. 2008;15(4):386–92. doi: 10.2174/092986708783497382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Leonardsson G, Steel JH, Christian M, et al. Nuclear receptor corepressor RIP140 regulates fat accumulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004 Jun 1;101(22):8437–42. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401013101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Berriel Diaz M, Krones-Herzig A, Metzger D, et al. Nuclear receptor cofactor receptor interacting protein 140 controls hepatic triglyceride metabolism during wasting in mice. Hepatology. 2008 Sep;48(3):782–91. doi: 10.1002/hep.22383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Seth A, Steel JH, Nichol D, et al. The transcriptional corepressor RIP140 regulates oxidative metabolism in skeletal muscle. Cell Metab. 2007 Sep;6(3):236–45. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Huq MD, Khan SA, Park SW, Wei LN. Mapping of phosphorylation sites of nuclear corepressor receptor interacting protein 140 by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectroscopy. Proteomics. 2005 May;5(8):2157–66. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200401090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Huq MD, Wei LN. Post-translational modification of nuclear corepressor receptor-interacting protein 140 by acetylation. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2005 Jul;4(7):975–83. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M500015-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gupta P, Huq MD, Khan SA, Tsai NP, Wei LN. Regulation of corepressive activity of and HDAC recruitment to RIP140 by site-specific phosphorylation. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2005 Nov;4(11):1776–84. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M500236-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Huq MD, Tsai NP, Lin YP, Higgins L, Wei LN. Vitamin B6 conjugation to nuclear corepressor RIP140 and its role in gene regulation. Nat Chem Biol. 2007 Mar;3(3):161–5. doi: 10.1038/nchembio861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mostaqul Huq MD, Gupta P, Tsai NP, White R, Parker MG, Wei LN. Suppression of receptor interacting protein 140 repressive activity by protein arginine methylation. EMBO J. 2006 Nov 1;25(21):5094–104. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gupta P, Ho PC, Huq MD, Khan AA, Tsai NP, Wei LN. PKCepsilon stimulated arginine methylation of RIP140 for its nuclear-cytoplasmic export in adipocyte differentiation. PLoS One. 2008;3(7):e2658. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ho PC, Gupta P, Tsui YC, Ha SG, Huq M, Wei LN. Modulation of lysine acetylation-stimulated repressive activity by Erk2-mediated phosphorylation of RIP140 in adipocyte differentiation. Cell Signal. 2008 Oct;20(10):1911–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2008.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Huq MD, Ha SG, Barcelona H, Wei LN. Lysine methylation of nuclear co-repressor receptor interacting protein 140. J Proteome Res. 2009 Mar;8(3):1156–67. doi: 10.1021/pr800569c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ho PC, Tsui YC, Feng X, Greaves DR, Wei LN. NF-kappaB-mediated degradation of the coactivator RIP140 regulates inflammatory responses and contributes to endotoxin tolerance. Nat Immunol. 2012 Mar 4; doi: 10.1038/ni.2238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Clague MJ, Urbe S. Ubiquitin: same molecule, different degradation pathways. Cell. 2010 Nov 24;143(5):682–5. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ho PC, Lin YW, Tsui YC, Gupta P, Wei LN. A negative regulatory pathway of GLUT4 trafficking in adipocyte: new function of RIP140 in the cytoplasm via AS160. Cell Metab. 2009 Dec;10(6):516–23. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2009.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gregor MF, Hotamisligil GS. Thematic review series: Adipocyte Biology. Adipocyte stress: the endoplasmic reticulum and metabolic disease. J Lipid Res. 2007 Sep;48(9):1905–14. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R700007-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ho PC, Tsui YC, Lin YW, Persaud YSD, Wei LN. Endothelin-1 promotes cytoplasmic accumulation of RIP140 through a ET(A)-PLCbeta-PKCepsilon pathway. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2011 Dec 19; doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2011.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Potenza MA, Gagliardi S, Nacci C, Carratu MR, Montagnani M. Endothelial dysfunction in diabetes: from mechanisms to therapeutic targets. Curr Med Chem. 2009;16(1):94–112. doi: 10.2174/092986709787002853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rehsia NS, Dhalla NS. Potential of endothelin-1 and vasopressin antagonists for the treatment of congestive heart failure. Heart Fail Rev. 2010 Jan;15(1):85–101. doi: 10.1007/s10741-009-9152-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schneider JG, Tilly N, Hierl T, et al. Elevated plasma endothelin-1 levels in diabetes mellitus. Am J Hypertens. 2002 Nov;15(11):967–72. doi: 10.1016/s0895-7061(02)03060-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Takahashi K, Ghatei MA, Lam HC, O’Halloran DJ, Bloom SR. Elevated plasma endothelin in patients with diabetes mellitus. Diabetologia. 1990 May;33(5):306–10. doi: 10.1007/BF00403325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bedi D, Clarke KJ, Dennis JC, et al. Endothelin-1 inhibits adiponectin secretion through a phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate/actin-dependent mechanism. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006 Jun 23;345(1):332–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.04.098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ignatov A, Robert J, Gregory-Evans C, Schaller HC. RANTES stimulates Ca2+ mobilization and inositol trisphosphate (IP3) formation in cells transfected with G protein-coupled receptor 75. Br J Pharmacol. 2006 Nov;149(5):490–7. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Shideman CR, Hu S, Peterson PK, Thayer SA. CCL5 evokes calcium signals in microglia through a kinase-, phosphoinositide-, and nucleotide-dependent mechanism. J Neurosci Res. 2006 Jun;83(8):1471–84. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sakamoto K, Holman GD. Emerging role for AS160/TBC1D4 and TBC1D1 in the regulation of GLUT4 traffic. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2008 Jul;295(1):E29–37. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.90331.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ho PC, Wei LN. Negative regulation of adiponectin secretion by receptor interacting protein 140 (RIP140) Cell Signal. 2012 Jan;24(1):71–6. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2011.07.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]