Abstract

Objective

The accuracy of various 10-year cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk calculators in Indians may not be the same as in other populations. Present study was conducted to compare the various calculators for CVD risk assessment and statin eligibility according to different guidelines.

Methods

Consecutive 1110 patients who presented after their first myocardial infarction were included. Their CVD risk was calculated using Framingham Risk score- Coronary heart disease (FRS-CHD), Framingham Risk Score- Cardiovascular Disease (FRS-CVD), QRISK2, Joint British Society risk calculator 3 (JBS3), American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA), atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) and WHO risk charts, assuming that they had presented one day before cardiac event for risk assessment. Eligibility for statin uses was also looked into using ACC/AHA, NICE and Canadian guidelines.

Results

FRS-CVD risk assessment model has performed the best as it could identify the highest number of patients (51.9%) to be at high CVD risk while WHO and ASCVD calculators have performed the worst (only 16.2% and 28.3% patients respectively were stratified into high CVD risk) considering 20% as cut off for high risk definition. QRISK2, JBS3 and FRS-CHD have performed intermediately. Using NICE, ACC/AHA and Canadian guidelines; 76%, 69% and 44.6% patients respectively were found to be eligible for statin use.

Conclusion

FRS-CVD appears to be the most useful for CVD risk assessment in Indians, but the difference may be because FRS-CVD estimates risk for several additional outcomes as compared with other risk scores. For statin eligibility, however, NICE guideline use is the most appropriate.

Keywords: Cardiovascular risk calculators, Primary prevention, Myocardial infarction, Cardiovascular risk score

1. Introduction

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) burden is large and is growing in South Asia.1 In these countries, the age of onset of first myocardial infarction is on average 10 years earlier as compared with other countries.2 INTERHEART and INTERSTROKE study found that more than 86% of CVD was attributable to nine key risk factors (smoking, lipids, hypertension, diabetes, obesity, diet, physical activity, alcohol consumption and psychosocial factors).3, 4 Unlike other traditional risk factors, the prevalence of diabetes mellitus is uniformly higher in South Asians than in many other populations.5 Tobacco use is generally low among South Asian men and very less among South Asian women.6 South Asian Indians have low HDL and high triglyceride levels. LDL particles are smaller and denser. Lipoprotein (a), C-reactive protein, homocysteine, and plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 levels tend to be higher in South Asians than in white populations.6, 7 So, the risks of having cardiovascular disease with the same traditional risk factors differ in Indian population.

Cardiovascular risk prediction models are important in the prevention and management of cardiovascular diseases. Many risk estimation systems are in existence.8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13 The best known and probably the most widely used globally is the Framingham Risk Score. Several modified versions of the 10-year Framingham Risk Calculator equation, QRISK2 model, the American Heart Association (AHA) and the American College of Cardiology (ACC) developed Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease (ASCVD) risk score calculator are used in clinical practice to identify and treat high-risk populations as well as to communicate risk effectively.14 Different guidelines recommend different risk score calculators to assess the 10-year cardiovascular risk and their management depending on their risk scores.15, 16, 17, 18

There are various concerns when adopting a risk prediction model for the clinical assessment of a patient to determine treatment options. The most important of which is the local applicability and modifiability of the risk model. Considering the Indian population who develop CAD at an earlier age and also have higher frequency of emerging risk factors,19 the performance of the previous models may not be equal and accurate. Previous study by Kanjilal et al. found that Framingham Risk Score (old version) was able to identify only 5% of their population to be at high risk.20 Recent retrospective study by Bansal et al. in Indian patients who already had acute myocardial infarction found that the Joint British Society risk calculator 3 (JBS3) performs the best.21

So, the present study was conducted with the aims and objectives of comparing the various 10-year cardiovascular risk prediction scores in a patient population who presented with acute myocardial infarction and also to compare the various guideline recommendations for statin eligibility in these patients as a part of primary prevention measure depending on their respective risk scores had they presented just before their clinical event with the same risk factors for their 10-year CV risk assessment.

2. Methods

Consecutive patients of 25–85 years age who were presented with recent history of acute myocardial infarction (MI) were included in the study. The diagnosis of MI was based on 3rd universal definition of MI.22 All patients underwent detailed clinical evaluation including history and physical examination. Height and body weight were measured and body mass index (BMI) was calculated. Blood pressure was measured and hypertension was defined according to JNC criteria.23 Smoking was defined according to NHIS definitions.24 Blood samples were collected at the time of hospital admission and were evaluated for HbA1c levels, random blood sugar level, renal function tests and routine haemogram. Fasting blood samples were collected on the next day and were evaluated for fasting blood sugar levels and lipid profile. HDL level <40 mg/dl in male and <50 mg/dl in female was considered as low HDL while triglyceride level of more than 150 mg/dl was taken as high. The e-GFR (estimated glomerular filtration rate) was calculated from MDRD (Modification of Diet in Renal Disease) study equation.25 HbA1c levels were measured using Bio-Rad D-10 dual program (Bio-Rad Co., Hercules, CA) using ion-exchange high-performance liquid chromatography. Ethical clearance for the study was obtained from institutional ethical committee.

Based on the data their risk scores were calculated. Online calculators available at www.framinghamheartstudy.org/risk-functions/cardiovascular-disease/10-year-risk.php, http://tools.acc.org/ASCVD-Risk-Estimator/, http://www.qrisk.org/, http://www.jbs3risk.com/JBS3Risk.swf, http://CVdrisk.nhlbi.nih.gov/for Framingham Risk Score-Cardiovascular Disease (FRS-CVD), ACC/AHA Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease (ASCVD) risk score, QRISK2, Joint British Society calculator-3 (JBS3), Framingham Coronary Heart-Disease Risk Score (FRS-CHD) respectively were used for the calculations. WHO/ISH CV risk calculations were done using WHO/ISH chart. Minor adjustments were done in risk factors as per the calculator requirement. All calculators provided the risk score in numeric values except the WHO/ISH model that gave the risk in categories.

We have also divided the risk categories into high (10-year risk score ≥20%) and low risk (10-year risk score <20%) groups in each model to identify which model maximally identifies the high risk groups. For “Statin Eligibility” categorization the respective guideline directed risk calculators and risk score cut offs were used. For this purpose, we have used ACC/AHA 2013 guideline which uses ASCVD risk score and a cut off of ≥7.5% for initiation of moderate to high intensity statin, NICE 2014 guideline which uses QRISK2 risk engine and offers atorvastatin 20 mg daily who have a score ≥10% and Canadian 2012 guideline using FRS CVD risk score with cut off of ≥20% for statin initiation.

Age, gender, systolic blood pressure, total & HDL cholesterol, smoking status and treatment for hypertension were considered in FRS-CHD risk score calculation. Diabetes was considered as a CVD equivalent. In FRS-CVD, diabetes was considered as a risk factor for score calculation. In ASCVD calculator, race was taken into account as an additional factor. In QRISK2 the presence of chronic kidney disease, atrial fibrillation, rheumatoid arthritis, family history of CVD, ethnicity along with body mass index were also considered along with the classical risk factors. JBS3 used the same risk factors for risk score calculation as QRISK2.

2.1. Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was done using IBM SPSS statistics 20 package. All values were expressed as mean (±standard deviation) or as percentages. Standard descriptive analysis was performed to analyse the baseline characteristics of the study population. The categorized risk estimates derived from the different risk scores were compared either using Wilcoxon's signed rank test for the non-dichotomized risk scores and the dichotomized risk scores were compared using Mc-Nemar test. Pearson’s correlation coefficient (r) was estimated to assess the relationship between various risk score calculators. A p value ≤0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Baseline characteristics

Baseline characteristics of the study population are presented in Table 1. The average age of the whole population was 57.3 ± 9.5 years. Males were predominant. Only 3.6% of the study population had young MI patients. Most were non-obese subjects with average BMI of 26.1 ± 18.4 kg/m2. The prevalence of hypertension, smoking, diabetes mellitus (DM) was almost similar, each constituting about 30% of the study population. Average LDL was lower than expected i.e. 86.7 ± 32.2 mg/dl. A low HDL and high triglyceride were highly prevalent. Only 2.5% had a family history of premature CVD. Around 85% suffered a STEMI. Only 8 of our patients were known cases of chronic kidney disease (CKD), 1 had proven rheumatoid arthritis while 4 had chronic atrial fibrillation (AF).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the study population (n = 1110).

| Parameter | Value (%)* |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 57.3 ± 9.5 |

| Gender (Male/Female) | 886/114 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 26.1 ± 18.4 |

| SBP (mm Hg) | 130.3 ± 19.1 |

| DBP (mmHg) | 79.0 ± 9.4 |

| LDL (mg/dl) | 86.7 ± 32.2 |

| HDL (mg/dl) | 31.9 ± 8.7 |

| TG (mg/dl) | 186.9 ± 120.8 |

| RBS (mg/dl) | 134.9 ± 66.6 |

| Serum creatinine (mg/dl) | 1.1 ± 0.3 |

| Hypertension | 179 (32.2%) |

| Diabetes | 184 (33.1%) |

| Smoker | 175 (31.5%) |

| Family history of premature CVD | 14 (2.5) |

| Myocardial Infarction type STEMI NSTEMI |

1019 (83.7) 91 (16.3) |

| Young MI (<40 year old) | 40 (3.6) |

*Numbers in parentheses indicate% of total population. Abbreviations: BMI = Body mass index, SBP = Systolic blood pressure, DBP = Diastolic blood pressure, LDL = Low density lipoprotein, HDL = High density lipoprotein, TG = Triglyceride, RBS = Random blood sugar, MI = Myocardial infarction, STEMI = ST elevation myocardial infarction, NSTEMI = Non ST elevation myocardial infarction.

3.2. 10-year CV risk score

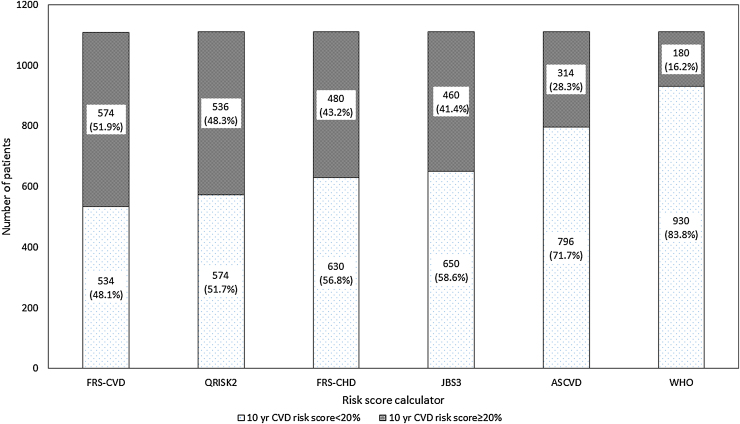

When the 10-year risk scores of the total population was calculated (Table 2), FRS global CVD risk score could identify maximum number of patients with high CVD risk (risk score ≥20%) followed by QRISK2 calculator. WHO risk calculator and ASCVD risk score calculator had performed the worst. WHO risk score calculator has stratified more than 50% of the acute MI patients to have a 10-year CVD risk to be less than 10% while ASCVD score calculator has stratified more than 40% to have score less than 10%. JBS3 and Framingham-CHD had performed intermediately (Fig. 1).

Table 2.

10-year CV risk scores using different risk calculator (n = 1110).

| 10-year risk | FRS-CVD (%)* | ASCVD (%)* | QRISK2 (%)* | JBS3 (%)* | WHO (%)* | FRS-CHD (%)* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <10% | 212 (19.1) | 448 (40.4) | 264 (23.8) | 326 (29.4) | 594 (53.5) | 356 (32.1) |

| 10–<20% | 322 (29) | 348 (31.4) | 310 (27.9) | 324 (29.2) | 336 (30.3) | 274 (24.7) |

| 20– <30% | 254 (22.9) | 198 (17.8) | 252 (22.7) | 242 (21.8) | 80 (7.2) | 90 (8.1) |

| 30– <40% | 150 (13.5) | 82 (7.4) | 156 (14.1) | 128 (11.5) | 64 (5.8) | 390 (35.1) |

| ≥40% | 172 (15.5) | 34 (3.1) | 128 (11.5) | 90 (8.1) | 36 (3.2) | – |

*Number in parentheses indicate percentage of total population,

P value <0.005 for all except between JBS-3 and FRSCHD models.

Abbreviations: FRSCVD = Framingham Risk Score Cardiovascular disease (global), ASCVD = Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular disease, JBS = Joint British Society, WHO = World Health Organisation, FRSCHD = Framingham Risk Score Coronary Heart Disease.

Fig. 1.

10-year dichotomized risk categorization of the patient population by various risk score calculators.

When we considered the dichotomized risk score (high i.e. ≥20% or low <20%), the pattern did not differ much (Table 3). WHO risk score calculator again had performed the worst. WHO risk score and ASCVD risk score calculators could identify only 16.2% and 28.3% of study population to be in high risk for CVD events respectively whereas FRS global CVD risk score calculated more than 50% of the patients to be in high risk category. QRISK2 put 48.3% of the MI patients to be in high risk category. The difference was significant for all except between JBS3 and FRS-CHD models when we considered the non-dichotomized risk categories. But for dichotomized risk categories the FRS-CVD and QRISK2 were also not differed significantly.

Table 3.

10-year dichotomized risk categories (n = 1110).

| 10-year risk | FRS-CVD (%) | ASCVD (%) | QRSIK2 (%) | JBS3 (%) | FRS-CHD (%) | WHO (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <20% | 534 (48.1) | 796 (71.7) | 574 (51.7) | 650 (58.6) | 630 (56.8) | 930 (83.8) |

| ≥20% | 576 (51.9) | 314 (28.3) | 536 (48.3) | 460 (41.4) | 480 (43.2) | 180 (16.2) |

*Number in parentheses indicate percentage of total population.

P value <0.005 for all except between JBS-3 and FRS-CHD models, FRS-CVD and QRISK-2.

Abbreviations: FRSCVD = Framingham Risk Score Cardiovascular disease (global), ASCVD = Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular disease, JBS = Joint British Society, WHO = World Health Organisation, FRS-CHD = Framingham Risk Score Coronary Heart Disease.

When we applied the risk scores in non-diabetic subjects (Table 4) the risk stratification power of FRS-CHD risk calculator deteriorated and 85% of the study patients were diagnosed as low risk cases for CVD events.

Table 4.

10-year dichotomized risk in non-diabetic patients (n = 740).

| 10-year risk | FRS-CVD (%) | ASCVD (%) | QRSIK2 (%) | JBS3 (%) | FRS-CHD (%) | WHO (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <20% | 410 (55.4) | 590 (79.7) | 454 (61.4) | 484 (65.4) | 628 (84.9) | 670 (90.5) |

| ≥20% | 330 (44.6) | 150 (20.3) | 286 (38.6) | 256 (34.6) | 112 (15.1) | 70 (9.5) |

*Number in parentheses indicate percentage of total population.

Abbreviations: FRSCVD = Framingham Risk Score Cardiovascular Disease (global), ASCVD = Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease, JBS = Joint British Society, WHO = World Health Organization, FRS-CHD = Framingham Risk Score Coronary Heart Disease.

3.3. Statin eligibility

Considering the guideline based recommendation for statin initiation for primary prevention of cardiovascular diseases, 76% of study population would have received statins using recent NICE guidelines and 69% by following the ACC/AHA 2010 guidelines. Canadian guideline using FRS-CVD global risk score, only 44.6% of study subjects were eligible for statins (Table 5).

Table 5.

Statin eligibility in accordance to different guidelines using different risk scores (n = 1110).

| Guidelines (risk calculator)* | Statin eligible |

|---|---|

| ACC/AHA-2013 (ASCVD ≥7.5%) | 766 (69%) |

| Canadian-2012 (FRS-CVD ≥20%) | 330 (44.6%) |

| NICE-2014 (QRISK2 ≥10%) | 846 (76%) |

*Risk calculator used by the guideline is in parentheses.

Abbreviations: ACC/AHA = American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association, ASCVD = Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease, FRS-CVD = Framingham Cardiovascular Disease.

4. Discussion

The results of the present study showed that the FRS global CVD risk assessment model could stratify maximum number of patients into high risk for hard cardiovascular events. QRISK2, JBS3, FRS-CHD have performed intermediately. ACC/AHA-ASCVD risk score calculator and WHO risk score calculator could identify least number of patients to be in high risk so has performed the worst in our patient population considering 20% as cut off for high risk definition. To the best of our knowledge this study is the first study from India that has used and compared global FRS-CVD model with QRISK2 and also compared statin eligibility criteria by various guidelines.

However, it should be noted that FRS-CVD estimates risk for a large combination of CVD outcomes including coronary death, myocardial infarction, coronary insufficiency, angina, ischemic stroke, haemorrhagic stroke, transient ischemic attack, peripheral artery disease and heart failure. In contrast, the other risk engines/tools estimate risk mainly for myocardial infarction (fatal and non-fatal) and stroke only. Thus, FRS-CVD is not directly comparable to other tools and may not perform the best in Indians if the same outcomes were to be measured with all the risk assessment tools.

For the prevention of cardiovascular diseases in high risk population it becomes essential to find out 10-year CVD risk that can help us in identifying high CVD risk individuals neither by underestimating nor by overestimating the risk. Framingham risk equation for CV risk calculation tends to overestimate CV risk by approximately 5% in UK men. QRISK2 developed by Collins et al. for use in Unite Kingdom has been seen to under predict the risk in South Asians.26, 27

Similarly, ACC/AHA-ASCVD risk calculator is likely to underestimate risk in South Asian Americans and it does not consider the family history or the emerging risk factors which are common in Asian population in CV risk calculation. Chai et al. in an Asian Study examined the validity of the pooled cohort risk score in a primary care setting.28 The ACC/AHA risk calculator was found to be appropriate for risk prediction in primary setting in the absence of treatment but over predicted the risk if subjects received treatment for risk factors. In those patients with pooled cohort risk score <7.5%, about two-thirds of these patients have a FRS of >10%. This was because of the events predicted in FRS in comparison to ASCVD risk estimator giving a magnified view of the risk.

Kanjilal et al. had compared FRS-1998, JBS and SCORE risk calculators in unaffected Asian Indians with family history of CAD.20 They showed that the Framingham-based risk scores (Framingham and the Joint British Societies) and the European SCORE underestimate the risk of cardiovascular disease morbidity and mortality in Asian Indians. In their study only 5% Asian Indians were found to be at high risk, so substantially underestimated the risk. However, except for the family history the prevalence of other major CVD risk factors was low in their cohort- hypertension only 13.2%, diabetes 7.4%, smoking 10.6%, etc. In our study, we did not analyse the SCORE risk calculator but the FRS-CVD and JBS3 have performed better. However, the Framingham risk calculator we used in our study was an updated version of that used by Kanjilal et al.

Recently, Bansal et al. had studied 194 patients attending a CV disease prevention clinic at a tertiary care centre in north India.29 Four risk assessment models (Framingham Risk score, ACC/AHA risk score, JBS3 risk score and the WHO risk score) were applied. The estimated risk scores were correlated with carotid intima-media thickness (CIMT) and coronary calcium score (CCS). Overall, ACC/AHA risk score calculator and WHO risk score calculator significantly underestimated the CV risk as compared to JBS and FRS, with JBS being the least likely to underestimate the risk. Further, only JBS and FRS risk scores, but not ACC/AHA and WHO risk scores, demonstrated consistent relationship with CIMT and CCS.

In a previous study by the Bansal et al., the JBS risk score was found to be the best risk calculator, as it could identify 55.9% of their study population at high risk using ≥20% as cut off for a high risk score.21 JBS risk calculator identified the largest proportion of the patients as being at “high-risk” while the Framingham and ACC/AHA-ASCVD risk score calculator performing worse than JBS to identify the high risk. In the Framingham risk calculator, they had used the updated FRS global CVD risk score which is expected to give a higher score value but was found to perform worse than JBS risk engine. In our study, the FRS global CVD risk calculator was found to perform the best followed by QRISK2.

QRISK2 is a British risk assessment tool and seems to work very well in Indians. In this context, it should be noted that JBS3 risk calculator is also based on QRISK data only (albeit QRISK lifetime). For this reason, both JBS3 and QRISK2 provide similar estimates for 10-year CVD risk, except in diabetics in whom QRISK lifetime seems to provide lower 10-year risk estimates. Previous studies by Bansal et al.21, 29 found JBS3 to be the most suited for Indians (QRISK2 was not included in their studies). Thus, it appears that for estimation of 10-year risk of myocardial infarction and stroke in Indians, these British risk scores may be more suited rather than the US based risk calculators.

Statin therapy is one of the most important preventive measures and has been recommended for patients who are at high risk for development of future CVD. Different guidelines recommend statin therapy for high risk subgroups as identified by using different risk score calculators. Mortensen et al. had evaluated the risk-based statin eligibility for primary prevention in accordance to the recommendations of different guidelines in 393 nondiabetics patients hospitalized for the first MI, assuming that they had a health check-up a day before acute MI.30 The SCORE risk based European society guideline restricted the statin eligibility for primary prevention substantially by reclassifying many noneastern European people from ‘high-risk’ to ‘low-risk’, whereas the eligibility was expanded by using the ACC/AHA guidelines and new NICE guidelines by lowering the decision threshold.

In our study the ACC/AHA guideline recommendations stratified 69% of our population in the statin eligible group. The NICE guideline recommendation has performed the best as it identified the maximum number of patients (76%) for statin eligibility and this point further corroborates that QRISK2 risk calculator works well in the Indian. Though the FRS-CVD risk score was good in stratifying maximum number of patients into high risk, the Canadian guideline 2012 identified statin eligibility for only 44.6% even after using FRS global CV in comparison to the previous two guidelines using ACC/AHA and QRISK2 calculators.

4.1. Study limitations

The primary limitation of our study is that the risk scores used in our study are primarily intended for identifying high risk population free of cardiovascular disease, not for patients who already have developed a hard CV event. Secondly, in few patients the characters were minimally modified to make them suitable for risk calculations. Thirdly, FRS-CVD which was found to be most useful in our study is not directly comparable to other risk calculators as it estimates risk for few additional CVD outcomes in comparison to other risk score calculators. So, it is possible that FRS-CVD may not perform the best in Indians if the same outcomes were to be measured with all the risk calculators. Fourthly, for statin eligibility NICE guideline has performed the best in highest risk category but could not analyse how it would recommend for low risk population. Finally, it would have been more appropriate to use only one risk estimate but apply different thresholds for defining statin eligibility.

5. Conclusions

For identification of high CVD risk group, FRS-CVD is most useful while for statin eligibility for primary prevention, NICE guideline use appears to be most useful in our patient population who already had an acute myocardial infarction. This is to be tested in large scale prospective studies.

Key message.

What was known

-

•

In Indians the 10 year CVD risk score calculators do not behave the same as in western population.

New

-

•

For identification of high CVD risk group in Indians, FRS-CVD risk assessment model is most useful while for statin eligibility, NICE guideline use (using QRISK2) is most appropriate for our population.

References

- 1.Gaziano T.A., Bitton A., Anand S. Growing epidemic of coronary heart disease in low- and middle-income countries. Curr Probl Cardiol. 2010;35:72–115. doi: 10.1016/j.cpcardiol.2009.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siegel Karen R., Patel Shivani A., Ali Mohammed K. Non-communicable diseases in South Asia: contemporary perspectives. Br Med Bull. 2014;111(1):31–44. doi: 10.1093/bmb/ldu018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rosengren A., Hawken S., Ounpuu S. Association of psychosocial risk factors with risk of acute myocardial infarction in 11119 cases and 13648 controls from 52 countries (the INTERHEART study): case-control study. Lancet. 2004;364:953–962. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17019-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.O’Donnell Martin J., Xavier Denis, Liu Lisheng. Risk factors for ischaemic and intracerebral haemorrhagic stroke in 22 countries (the INTERSTROKE study): a case-control study. Lancet. 2010;376:112–123. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60834-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.King H., Aubert R.E., Herman W.H. Global burden of diabetes, 1995–2025: prevalence, numerical estimates, and projections. Diabetes Care. 1998;21:1414–1431. doi: 10.2337/diacare.21.9.1414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Anand S.S., Yusuf S., Vuksan V. Difference in risk factors, atherosclerosis, and cardiovascular disease between ethnic groups in Canada: the Study of Health Assessment and Risk in Ethnic groups (SHARE) Lancet. 2000;356:279–284. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)02502-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vaduganathan M., Rao R.S., Koschinsky M. Evaluation of Lp (a) and other independent risk factors for CHD in Asian Indians and their USA counterparts. J Lipid Res. 2001;42:631–638. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.D’Agostino R.B., Sr., Vasan R.S., Pencina M.J. General cardiovascular risk profile for use in primary care: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 2008;117:743–753. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.699579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Conroy R.M., Pyörälä K., Fitzgerald A.P. Estimation of ten-year risk of fatal cardiovascular disease in Europe: the SCORE project. Eur Heart J. 2003;24:987–1003. doi: 10.1016/s0195-668x(03)00114-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Woodward M., Brindle P., Tunstall-Pedoe H. Adding social deprivation and family history to cardiovascular risk assessment: the ASSIGN score from the Scottish Heart Health Extended Cohort (SHHEC) Heart. 2007;93:172–176. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2006.108167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hippisley-Cox J., Coupland C., Vinogradova Y. Predicting cardiovascular risk in England and Wales: prospective derivation and validation of QRISK2. BMJ. 2008;336:1475–1482. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39609.449676.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Assmann G., Cullen P., Schulte H. Simple scoring scheme for calculating the risk of acute coronary events based on the 10-year follow-up of the Prospective Cardiovascular Munster (PROCAM) study. Circulation. 2002;105:310–315. doi: 10.1161/hc0302.102575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.WHO; Geneva: 2007. World Health Organization Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease Guidelines for Assessment and Management of Cardiovascular Risk. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goff D.C., Jr, Lloyd-Jones D.M., Bennett G. ACC/AHA guideline on the assessment of cardiovascular risk: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2014;(25 Suppl. 2):S49–S73. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000437741.48606.98. [June 24] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stone N.J., Robinson J.G., Lichtenstein A.H. ACC/AHA guideline on the treatment of blood cholesterol to reduce atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2014;(25 Suppl. 2):S1–45. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000437738.63853.7a. [June 24] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Anderson T.J., Grégoire J., Hegele R.A. Update of the Canadian cardiovascular society guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of dyslipidemia for the prevention of cardiovascular disease in the adult. Can J Cardiol. 2012;2013(29):151–167. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2012.11.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.2014. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence.https://www.nice.org.uk/news/article/nice-recommends-wider-use-of-statins-for-prevention-of-CVd [Accessed 9th December 2015] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reiner Željko, Catapano Alberico L., De Backer Guy. ESC/EAS Guidelines for the management of dyslipidaemias. Eur Heart J. 2011;32:1769–1818. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sharma M., Ganguly N.K. Premature coronary artery disease in Indians and its associated risk factors. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2005;1(3):217–225. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kanjilal S., Rao V.S., Mukherjee M. Application of cardiovascular disease risk prediction models and the relevance of novel biomarkers to risk stratification in Asian Indians. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2008;4:199–211. doi: 10.2147/vhrm.2008.04.01.199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bansal M., Kasliwal R.R., Trehan N. Comparative accuracy of different risk scores in assessing cardiovascular risk in Indians: a study in patients with first myocardial infarction. Indian Heart J. 2014;66:580–586. doi: 10.1016/j.ihj.2014.10.399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thygesen Kristian, Alpert Joseph S., Jaffe Allan S. Third universal definition of myocardial infarction ESC/ACCF/AHA/WHF expert consensus document. Circulation. 2012;126:2020–2035. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31826e1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lenfant C., Chobanian A.V., Jones D.W. Joint national committee on the prevention, detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure. seventh report of the joint national committee on the prevention, detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure (JNC 7): resetting the hypertension sails. Hypertension. 2003;41:1178–1179. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000075790.33892.AE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nelson D.E., Powell-Griner E., Town M. A comparison of national estimates from the national health interview survey and the behavioural risk factor surveillance system. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(8):1335–1341. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.8.1335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Greene T., Bourgoignie J.J., Habwe V. Baseline characteristics in the modification of diet in renal disease study. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1993;4(5):1221–1236. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V451221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Collins G.S., Altman D.G. An independent and external validation of QRISK2 cardiovascular disease risk score: a prospective open cohort study. BMJ. 2010;340:c2442. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c2442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tillin Therese, Hughes Alun D., Whincup Peter. Ethnicity and prediction of cardiovascular disease: performance of QRISK2 and Framingham scores in a UK tri-ethnic prospective cohort study (SABRE—Southall and Brent Revisited) Heart. 2014;100(1):60–67. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2013-304474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chia Y.C., Lim H.M., Ching S.M. Validation of the pooled cohort risk score in an Asian population- a retrospective cohort study. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2014;14(November (163)) doi: 10.1186/1471-2261-14-163. [20] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bansal M., Kasliwal R.R., Trehan N. Relationship between different cardiovascular risk scores and measures of subclinical atherosclerosis in an Indian population. Indian Heart J. 2015;67:332–340. doi: 10.1016/j.ihj.2015.04.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mortensen M.B., Falk E. Real-life evaluation of European and American high-risk strategies for primary prevention of cardiovascular disease in patients with first myocardial infarction. BMJ Open. 2014;4(10):e005991. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-005991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]