Abstract

Rationale

The position of C=C within fatty acyl chains affects the biological function of lipids. Ozone induced dissociation-mass spectrometry (OzID-MS) has great potential in determination of lipid double bond position, but has generally been implemented on low resolution ion trap mass spectrometers. In addition, most of the OzID-MS experiments carried out so far were focused on the sodiated adducts of lipids, fragmentation of the most commonly observed protonated ions generated in LC-MS based lipidomics workflow has been less explored.

Methods

Ozone generated in line from an ozone generator was connected to the trap and transfer gas supply line of a Synapt G2 high resolution mass spectrometer. Protonated ions of different phosphatidylcholines (PC) were generated by electrospray ionization through direct infusion. Different parameters, including traveling wave height and velocity, trap entrance and DC potential were adjusted to maximize the OzID efficiency. sn- positional isomers and cis/trans isomers of lipids were compared for their reactivity with ozone.

Results

Traveling Wave height and velocity were tuned to prolong the encounter time between lipid ions and ozone, and resulted in improved OzID efficiency, as did increasing trapping region DC and entrance potential. Under optimized settings, at least 1000 times enhancement in OzID efficiency was achieved compared to that under default settings for monounsaturated PC standards. Monounsaturated C=C in the sn-2 PC isomer reacted faster with ozone than the sn-1 isomer. Similarly, the C=C in trans PC reacted faster than in cis PC.

Conclusions

This is the first implementation of OzID in the trap and transfer region of a traveling wave enabled high resolution mass spectrometer. The OzID reaction efficiency is significantly improved by slowing down ions in the trap region for their prolonged interaction with ozone. This will facilitate application of high resolution OzID-MS in lipidomics.

Keywords: Ozone-induced dissociation mass spectrometry, traveling wave, lipid double bond, lipid isomers

Introduction

Lipids are involved in a wide range of biological processes from being a major component of cell membranes to regulation of metabolic pathways. Changes in lipids are reflected in various pathological and physiological conditions.[1–5] Consequently, lipids have been implicated as biomarkers and major contributors to diverse diseases such as obesity, diabetes, cancers and Alzheimer’s.[6, 7]

The function of a lipid depends on its molecular structure. Lipid isomers that differ only in their fatty acyl C=C position can have very distinctive roles functionally. For example, free fatty acids (FFAs) that contain double bonds at ω6 or ω9 positions inhibit the activity of nicotinic acetylcholine receptor, while the ω11 and ω13 isomers have no such effect.[8] Similarly, FA (18:1, ω3) prevents cardiovascular disease whilst its ω6 double bond positional isomer worsens this disease.[9] Thus, detailed characterization of lipid structures would aid in understanding their biological functions.

Recent advancements in the field of mass spectrometry (MS) have greatly improved the field of lipidomics, as a result more lipids have been identified with better structural annotation.[10–14] However, the determination of carbon-carbon double bond locations within the unsaturated fatty acyl chains still remains a challenge. Different hyphenated mass spectrometry techniques have been used to localize lipid double bond positional isomers. In gas chromatography coupled with mass spectrometry (GC-MS), lipid molecules are derivatized to form methyl esters for volatilization, which is followed by fragmentation with high energy electron ionization. Although this GC-MS analysis can pinpoint the location of a double bond that is closest to the methyl end of the fatty acyl chain, it only allows confident identification of the location of double bonds in monounsaturated lipid species.[15] In addition, the sn- substituent information is lost during the hydrolysis process and therefore GC-MS is incapable of determining C=C positions from intact lipids. On the other hand, the commonly used low energy collision induced dissociation (CID)-MS, is able to assign the sn- positions and identify the total number of carbon on each fatty acyl chain along with their total degree of unsaturation from intact lipids, but struggles to characterize the locations of double bonds without using multistage ion activation techniques on lipid-metal adduct ions.[16–20] Alternatively, high energy CID-MS has been applied to study the structural variation of the fatty acyl chains, yielding a highly complicated fragmentation spectrum embedded with structurally diagnostic product ions.[21–23]

C=C selective ion-molecule reactions are promising techniques that largely overcome the above mentioned limitations. They also offer increased sensitivity and the ability to provide detailed structural information of a given lipid molecule when coupled with mass spectrometry. Xia and co-workers coupled a photochemical reaction online with tandem mass spectrometry. [24–27] When the Paternò-Büchi (PB) reaction product between a lipid ion and acetone is activated using CID, it generates a pair of diagnostic ions originating from the C=C location. Using a 193 nm laser, Brodbelt and co-workers implemented ultraviolet photodissociation on an Orbitrap mass spectrometer to localize C=C in lipids.[28] Another well-known ion-molecule reaction is the ozone-induced dissociation (OzID) pioneered by Blanksby and co-workers, which uses the ozonolysis reaction of C=C to pinpoint the location of double bonds based on the neutral loss of diagnostic fragment ions (aldehyde and Criegee ions).[15, 29–33] OzID has been implemented in both shotgun and LC-MS based lipid analyses, mainly using ion trap MS platforms (Thermo LTQ and AB QTRAP) to characterize the lipid double bond positional isomers; however, the presence of ozone/oxygen results in decreased resolution for helium filled ion traps when ozone/oxygen concentration exceeds a certain percentage in helium.[33] In addition, most of the OzID-MS experiments carried out so far were focused on the sodiated adducts of lipids owing to their stability and predominant presence in shot-gun based lipidomics workflows;[31, 32] fragmentation of the most commonly observed protonated ions generated in LC-MS based lipidomics workflow has been less explored.

In this work, we demonstrate the ozonolysis of protonated lipid ions in a high resolution MS instrument platform to elucidate the locations of double bonds on the lipid fatty acyl chains. The experimental arrangement was based on a Synapt G2 HDMS instrument (Waters Corp., Milford, MA), a MS with high resolution and accurate mass capability that employs Traveling Wave-based stacked ring ion guides (SRIGs) for ion transfer.[34] By modifying the default potential settings, we improved the OzID efficiency by increasing the reaction time between lipid ions and ozone gas in the TriWave region whilst maintaining the duty cycle of the scan. This approach is promising in both shotgun and LC-MS based lipid analysis to fully characterize the structure of unsaturated, intact lipids.

Experimental

Chemicals

C18:2 (10E,12Z) methyl ester was purchased from Nu-Chek Prep, Inc (Elysian, MN). All phospholipid standards were obtained from Avanti Polar lipids, Inc (Alabaster, AL). HPLC grade methanol, acetonitrile (ACN), and isopropanol (IPA) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). LC-MS grade ammonium formate and formic acid were provided by Fisher Scientific (Pittsburgh, PA).

Sample Preparations

C18:2 (10E,12Z) methyl ester standard solution was prepared in methanol (0.1 M NaOH) at a concentration of 25 μM. Phospholipid standard solutions were prepared in the solvent of ACN/IPA/H2O (65/30/5, v/v/v) at a concentration of 25 μM. To aid the formation of protonated ions, 10 mM of ammonium formate and 0.1% formic acid were added into each standard solution. All standards were stored at −20°C. A solution of 2 ng/μL leucine encephalin (Waters, UK) in ACN/H2O (50/50, v/v) with 0.1% formic acid was used as the lock mass for instrument calibrations.

In-line Ozone Generation

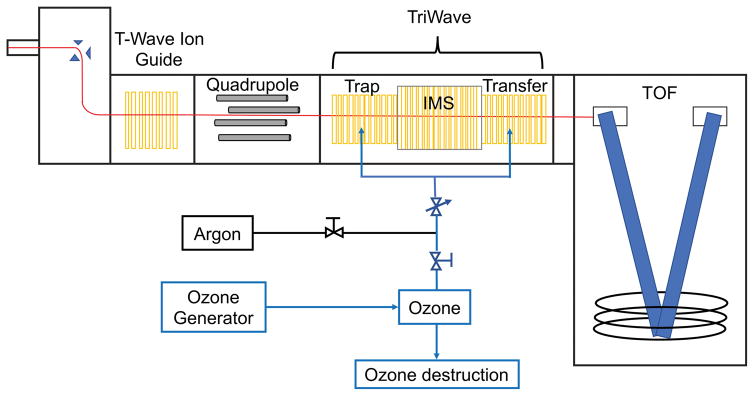

An O3MEGA Integrated Ozone Delivery System (MKS Inc, Andover, MA) was used for in-situ production of ozone from high purity oxygen. The oxygen pressure was set to 15 psi and the ozone system was capable of output up to 18 wt% of ozone at a flow rate of 1.0 slm by varying the power. The generated ozone/oxygen mixture was connected to the mass spectrometer trap/transfer gas supply, with the excess guided to an Ozone Destruct Module (MKS Inc.) to convert ozone back to oxygen before venting to the laboratory exhaust system (Fig. 1). To ensure safe operation of the ozone delivery system, an Ozone Leak Detector/Monitor (Ozone Engineering Inc., El Sobrante, CA) was installed to alarm and shut down ozone production if room ozone concentration exceeded safe levels.

Figure 1.

Schematic of the traveling wave Q-TOF mass spectrometer (Synapt G2) modified to allow OzID in the trap and transfer cells. IMS was off during experiment.

Mass Spectrometry

OzID-MS experiments were performed on a Waters Synapt G2 HDMS (Milford, MA) with MassLynx v4.1 instrument control and data acquisition software. The Synapt G2 HDMS has a TriWave region positioned between a quadrupole mass analyzer and an orthogonal time-of-flight (oa-ToF) mass detector (Fig. 1). The TriWave region is comprised of traveling wave-based SRIGs which have confining radio frequency and superimposed transient DC voltages for ion propulsion. These serve as: collision cell (trap); ion mobility separator (IMS) and ion transport device (transfer) delivering sophisticated ion manipulation functions, including ion accumulation, collision induced dissociation, ion mobility based separation and high speed ion transfer for TOF based detection. In the trap and transfer regions, ions can be manipulated to accumulate or fragment using CID prior or after the IMS region.[35, 36]

The argon collision gas inlet of the mass spectrometer was connected to a stainless-steel T union to accept both argon and ozone, with each line having its own shutoff valve. This inlet supplies collision gas to both trap and transfer cells as configured by the manufacturer (Fig. 1). The gas flow was maintained at 2.0 mL/min using a flow controller (Bronkhorst, Suffolk, UK) operated via MassLynx. At this gas flow rate, pressure at the trap region was at ~1.0 e-2 mbar. The effective ozone concentration during OzID was at 6.0 %, which can be achieved by either diluting the in line generated high concentration ozone with argon or by directly generating ozone at this concentration.

Sample was directly infused using a syringe pump at a flow rate of 5 μL/min, and ionized using the electrospray ionization source. The typical parameter settings for ionization were: source capillary voltage 2.70 kV; sample cone voltage 30V and extraction cone voltage 6.0V; source and desolvation temperature at 40°C and 80°C, respectively; the cone gas and desolvation gas flow rate at 50 L/h and 500 L/h of nitrogen respectively. Precursor ions were mass selected in the quadrupole and reacted with ozone gas in the trap and transfer regions before reaching the ToF detector. Full MS spectra were acquired for every sample. The scan rate was set at 0.2 s/scan. All spectra reported were averaged for 0.5 – 1 min.

The default trap and transfer collision energy were at 4.0 and 2.0 V, respectively. The Wave height and velocity in the trap region were set at 0.5 V and 300 m/s; in the transfer region were set at 0.2 V and 247 m/s. Additionally, the TriWave DC conditions were set as follows: for the trap region: trap DC entrance 2.0 V, trap bias 2V, trap DC −2.0 V, trap DC exit 0.0 V; for the transfer region: transfer DC entrance and exit at 5.0 V and 15.0 V, respectively.

Results and Discussions

1. Parameter optimization for OzID-MS

1.1 Performance of OzID at the default trap and transfer settings

All OzID performances of lipid standards were first studied using default acquisition settings of the Synapt G2 HDMS. In our experimental design, ozone gas was supplied to the trap and transfer regions to perform ozonolysis (Fig. 1). Ion residence time within the TriWave region can be estimated from the traveling wave velocity, which is derived from the distance between pairs of electrodes divided by the time the pulse remains on each pair. For example, the spacing between each electrode pair in the trap and transfer regions is 3 mm; therefore, a 10 μs pulse time gives rise to an average velocity of 300 m/s. Under these default settings, it takes 946 μs for an ion beam to transit through the trap and transfer regions while interacting with neutral gas before reaching the ToF detector.[36]

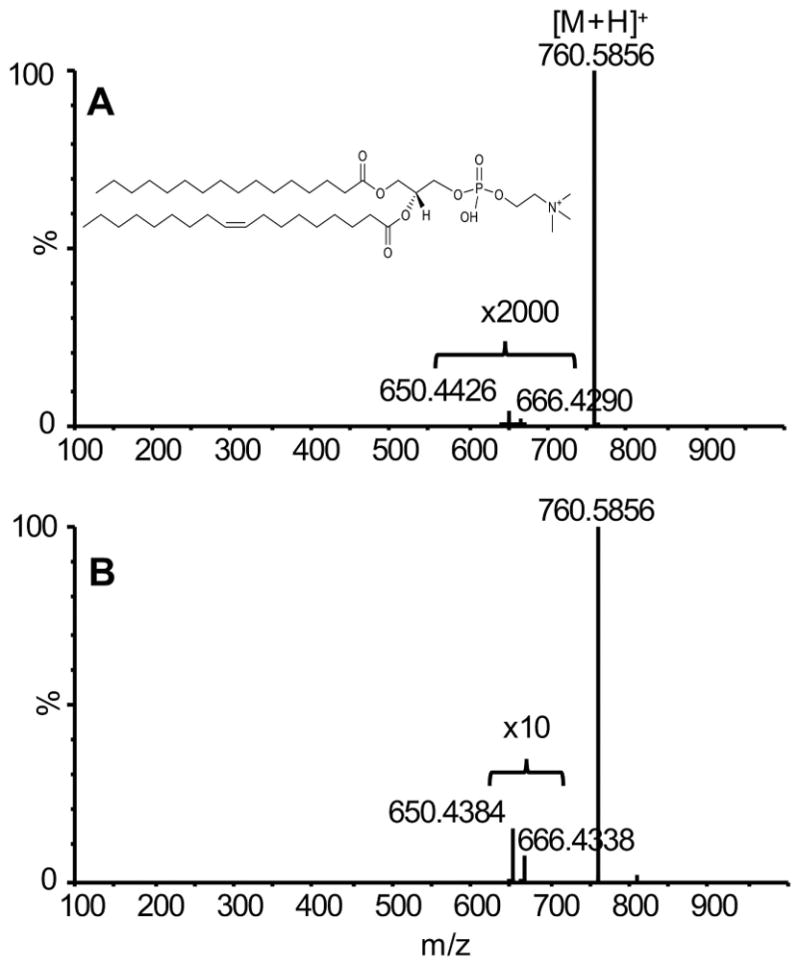

The conjugated lipid standard FAME C18:2(10E,12Z), previously shown to readily undergo ozonolysis was initially used to study OzID efficiency under the instrument default settings.[31] When argon or oxygen was employed as the collision gas, the sodiated adduct (m/z 317) alone was observed in the MS/MS spectrum under the default minimal collision energy used for ion transmission (Fig. 2A). In contrast, when ozone gas was introduced into the collision cells, OzID aldehyde product ions at m/z 223 and 249 were generated, albeit with low intensity (Fig. 2B). These ions are specific to the 10 and 12th position of the double bond location, respectively. Likewise, ozonolysis reaction of the protonated ions of PC (16:0/18:1(9Z)) (m/z 760) resulted in the characteristic neutral loss of 110 Da and 94 Da at the position n-9, which yielded the aldehyde and Criegee products ions at m/z 650 and 666, respectively (Fig. 3A). Compared to conjugated C=C (Fig. 2B), the monounsaturated C=C has ~ 100 times lower OzID efficiency. This is in line with what has been reported previously on the reaction rate difference between conjugated and single C=C when taking into consideration the influence of double bond conformation and metal-ion adduction.[37] It should be noted that these product ions were very weak and could only be observed in the spectra under high magnification. Nevertheless, these results indicated that OzID-MS could be implemented in the Traveling Wave mass spectrometer.

Figure 2.

OzID-MS spectra of FAME C18:2 (10E,12Z) under different MS settings: A, Oxygen, MS/MS at default settings; B, Ozone, MS/MS at default settings; C, Ozone, trap wave height = 0.2 V; D, Ozone, trap wave height = 0.2 V, trap wave velocity = 8 m/s, transfer wave height = 0.4 V and transfer wave velocity = 247 m/s.

Figure 3.

OzID-MS spectra of PC (16:0/18:1(9Z)) under different MS settings: A, Ozone, default settings; B, Ozone, trap wave height = 0.2 V, trap wave velocity = 8 m/s, transfer wave height = 0.4 V and transfer wave velocity = 247 m/s.

1.2 Optimization of traveling wave height and velocity in trap region to improve OzID efficiency

Under the default instrument settings, the traveling wave is set at an elevated wave velocity and wave height in order to reduce ion transmission times whilst maintaining sensitivity.[35] Although this default setting is very beneficial for normal applications, it depresses ozonolysis of unsaturated lipid ions due to the short reaction time with ozone. Thus, modifying the wave height and wave velocity would effectively allow control of the movement of ions across the trap and transfer regions and their reaction time with ozone.

Increasing the height of traveling wave reduces the chance of ions ‘rolling-over’ the waves and so reduces residence time in the collision cells. Based on this, a series of trap wave heights were applied from 0.0 V to 0.5 V (at fixed 300m/s wave velocity) to study the effect on ozonolysis of the sodiated ion of FAME C18:2 (10E,12Z). In Fig. 4A it can be seen that 0.2 V wave height produced the highest yield of the OzID products; the mass spectrum, shown in Fig. 2C, shows a 10× increase in OzID product yield compared to OzID spectrum under default settings (Fig. 2B). Additionally, when the wave height was < 0.2 V, ion impulses were not sufficient to allow the ions to keep up with the traveling wave through the SRIG, leading to significant loss of signal intensity. This is possibly due to the transit time being too long and ions not exiting the TriWave before the interscan period during which a sweep-out pulse is applied to limit cross-talk between precursor and product ions. Likewise, trap wave velocity could be decreased to enhance the OzID reaction (Fig. 4B). Results showed that trap wave velocity of 8 m/s (at fixed 0.2 V wave height) produced the highest relative intensity of the OzID product ions because lipid precursor ions remained in the trap and transfer regions together with ozone gas for 16.65 ms, which is significantly longer than the 946 μs of the default setting. A slight enhancement to the OzID efficiency was observed in the transfer region by altering the wave height to 0.4 V while keeping the defaulted transfer wave velocity at 247 m/s (Fig. 4C & D); however, unlike the trap region, overall there was no significant change in OzID efficiency when varying the wave height or wave velocity. This may be explained by ions having higher velocity (i.e. reduced residence time) in the transfer cell, likely as a result of the trap bias applied in TOF mode which effectively adds to the ion energy and hence velocity in the transfer region.

Figure 4.

Effects of changing traveling wave height and wave velocity on OzID efficiency: A, trap wave height effect; B, trap wave velocity effect; C, transfer wave height effect; D, transfer wave velocity effect. Data obtained by direct infusion of FAME C18:2 (10E,12Z).

Using FAME C18:2 (10E,12Z) as a conjugated C=C containing standard, the optimized traveling wave velocity and height in both trap and transfer regions increased OzID efficiency (I249/I317) ~20,000× when compared with the result obtained under the default settings (Fig. 2D vs Fig. 2B). Identical experiments were performed on PC (16:0/18:1(9Z)) to ensure the improvement of ozonolysis also worked on lipids containing a single C=C (Fig. 3B). Results showed a ~500× improvement in OzID efficiency (I650/I760) using optimized trap and transfer traveling wave height and velocity settings for a monounsaturated lipid (Fig. 3B vs Fig. 3A). The different OzID yield for conjugated and mono C=C is a result of their different reactivity with ozone, as it is known that the former has much faster reaction rate than the latter one.[37]

It is of note that an ion with m/z 263.1630 appeared when FAME C18:2 (10E, 12Z) reacted with ozone under optimized trap and transfer wave height and velocity settings (Fig. 2D). A radical cation of m/z 262 was reported previously from OzID of this compound,[37] however, the accurate mass that we measured for this ion preclude its identity as this radical cation. The exact identity of this ion remains to be determined; it is likely a result of hydrogen abstraction by the radical cation from other gas molecules in the vacuum environment (mass measurement error 2.66 ppm).

1.3 Optimization of trapping DC and entrance potential to further improve OzID efficiency

An alternate strategy that could prolong ion transit time is to increase the trap entrance voltage and trap DC. The trap entrance voltage is the voltage applied to the differential aperture at the entrance to the trap region, immediately after precursor ion selection in the quadrupole section. Trap DC is the potential of the post gate transport region of the trap cell. In the default setting, the trap entrance voltage and trap DC are set at 2V and −2 V, respectively relative to the main trap SRIG, to facilitate transmission of accumulated ions to the IMS cell (Fig. 5). However, these settings adversely decrease reaction time between ozone and lipid precursor ions, reducing efficiency. Alternatively, these settings can be modified to analogously create a “water dam” for the incoming ions, in order to increase residence time and boost the ozonolysis efficiency while maintaining the signal intensity of the spectrum (Fig. 5). Trap entrance and trap DC were optimized at 7V and 0.2V (Fig. 6), respectively, for maximum ozonolysis yield. The high trap entrance voltage would slow/hold the stream of ions at the entrance to the trap region, therefore, lengthen the reaction time of precursor ions with ozone gas exiting the trap. Once the number of ions built up at the trap entrance space charge effects would overwhelm the “dam”, precursor ions and OzID product ions would travel through trap and transfer cells to reach to TOF detector, while OzID was further performed during their transit. It is of note that the optimal ion dam settings are at the expense of reduced overall ion transmission and signal intensity. The trap DC of 0.2 V provided the best compromise (Fig. 6A).

Figure 5.

Diagrams illustrate the transmission of ions through the trap cell in the TriWave region and the effect to gas phase ozonolysis by changing trap entrance voltage and trap DC voltage. Potential hills are based on trap wave height at 0.2 V. Trap entrance DC and trap DC are the voltage applied at the entrance, and the end of trap cells (before ions entering the IMS), respectively. Under the default setting (A) of trap entrance (2V) and trap DC (−2V), ions can easily transmit through trap cell. Upon the increase of trap entrance and trap DC voltage (B), an artificial “ion dam” is created in the trap region to hold ions in this region to react with ozone.

Figure 6.

Effects on changing trap entrance and trap DC on OzID efficiency: A, trap DC effect; B, trap entrance effect. Data obtained by direct infusion of PC (16:0/18:1(9Z)).

The OzID-MS spectrum of protonated PC (16:0/18:1(9Z)) generated using these settings had sufficiently high intensity and signal-to-noise ratios to make the OzID product ions the base peak (Fig. 7A). To our knowledge, this is the first time that ozonolysis of a protonated monounsaturated lipid ion has been demonstrated with such high reaction efficiency, by simply passing the ions through the ozone gas at a slower rate. Compared to the spectrum acquired under the default acquisition setting (Fig. 3A), the aldehyde product ion (m/z 650) represents ~100,000× improvement in OzID efficiency (I650/I760). Even considering all the ion transmission losses with the ion dam settings, the absolute intensity of the aldehyde ion is still >1000× than that of the default settings.

Figure 7.

OzID-MS spectrum of (A) PC (16:0/18:1(9Z)) and (B) PC (18:1(9Z)/16:0) obtained under optimized OzID settings: trap wave height = 0.2 V, trap wave velocity = 8 m/s, transfer wave height = 0.4 V and transfer wave velocity = 247 m/s, trap entrance = 7V and trap DC = 0.2 V.

In addition to the commonly observed OzID products – the aldehyde and Criegee ions, we observed another abundant product ion at m/z 636.4240 (Fig. 7A). This ion is likely to be the further oxidation product of the vinyl peroxide structure of the Criegee ion as illustrated previously.[32] Under the environment of high concentration ozone, the vinyl peroxide ion lost formaldehyde (H2CO) to form the unique product observed. This has similar mass to the direct C=C cleavage product (m/z 636.4599) generated using a high energy collision (~10 keV) either on magnetic sector or TOF/TOF instruments.[21] Because of the low collision energy in our OzID experiments (4 eV) and the high mass measurement accuracy of the Synapt G2, we were able to assign the product ions correctly as the further oxidation product of vinyl peroxide (theoretical mass 636.4240), not the C=C bond direct cleavage.

Overall, the enhancement in efficiency and sensitivity of OzID on the traveling wave mass spectrometry system illustrates the benefit of prolonged reaction time with ozone, and suggests the potential for its integration with a shotgun-based high throughput lipidomics workflow. Application of these settings to differentiate lipid regioisomers was performed below.

2. Difference in the yields of OzID products can distinguish isomeric lipids

It has been reported that lipid isomers can be distinguished using OzID fragment ions of sodiated adducts.[29–33] To see if similar patterns can be observed using protonated lipid ions on this traveling wave-based OzID-MS, we selected four monounsaturated lipid standards: PC (16:0/18:1(9Z)), PC (18:1(9Z)/16:0), PC (18:1(9E)/18:1(9E)) and PC (18:1(9Z)/18:1(9Z)), with the former two representing sn-positional isomers and the latter two as cis-trans configurational isomers. Due to the ammonium formate/formic acid solvents used, protonated ions were the most abundant ions for these lipids and experiments were performed on the protonated ions.

2.1 sn-positional isomers

The OzID-MS spectra of the [M+H]+ ions of the two sn-positional isomers: PC (16:0/18:1(9Z)) and PC (18:1(9Z)/16:0) were acquired under identical ozone concentration and MS instrumental parameter settings (Fig 7A & 7B). The pairs of aldehyde (m/z 650) and Criegee product ions (m/z 666, very weak) observed in each of these spectra are characteristic of the expected neutral loss of 110 Da and 94 Da, resulting from the cleavage at double bond position n-9. Given the same OzID-MS settings, it is reasonable to compare the relative reactivity of these two isomers with ozone based on the ratio of product ion intensity to the precursor ions. Both of the isomers showed the aldehyde ion as the base peak at m/z 650, whereas the precursor ion for each isomer had different relative intensity. For the PC (16:0/18:1(9Z)), the relative intensity of precursor ion (m/z 760) was ~20%, whereas the intensity of the counterpart ion was ~50% of the base peak for PC (18:1(9Z)/16:0) isomer. This observation suggests that ozonolysis rates of the C=C depends on the substitution position of the fatty acyl moiety, and that the C=C in the protonated ions for PC (16:0/18:1(9Z)) isomer reacts ~1.5× faster than that in the PC (18:1(9Z)/16:0). The same observation was made by Poad et al. when they compared the reaction rates using the OzID approach with the addition of collision energy.[32]

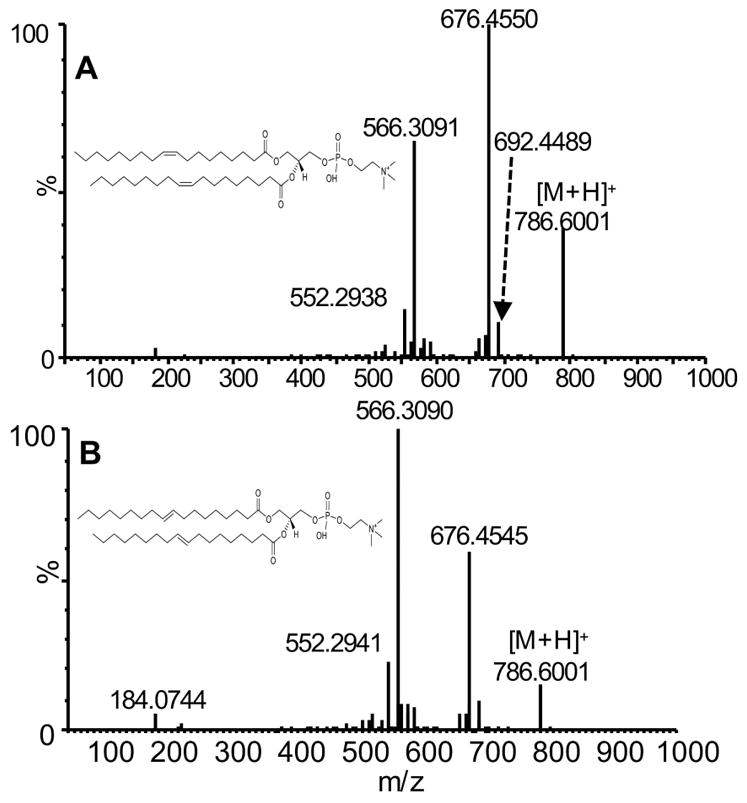

2.2 cis/trans configurational isomers

The OzID-MS spectra obtained from the reaction of ozone with the [M+H]+ ions of the stereoisomeric PC (18:1(9E)/18:1(9E)) and PC (18:1(9Z)/18:1(9Z)) (m/z 786) are shown in Fig. 8. The spectra were obtained under the same OzID settings as described in the analysis of PC (16:0/18:1(9Z)). Since the C=C position is at n-9, the expected neutral losses for the aldehyde (m/z 676) and Criegee ions (m/z 692, weak) are 110 Da and 94 Da when there is a cleavage of only one C=C from either of the fatty acyls. Moreover, we observed the abundant neutral loss of 220 Da, which is dual aldehyde (m/z 566), from the cleavage of double bonds from both sn-1 and sn-2 acyl chains. Comparing the OzID-MS spectra of the two configurational isomers in Fig. 8A & B, it is also interesting to note that the relative abundance of the OzID aldehyde products resulting from the cleavage of two double bonds (m/z 566) and one double bond (m/z 676) differ significantly between the cis- and trans- forms. The base peak in the OzID-MS spectrum of the trans-isomer was at m/z 566 (Fig. 8B), whilst under the same conditions, the cis-isomer spectrum presented a base peak at m/z 676 (Fig. 8A). This clearly indicates the trans- isomer has a higher reaction rate with ozone. Similar observations have been reported by Poad.et al for the OzID of the sodiated adducts of these phosphatidylcholine stereoisomers, in which the reaction rate of trans-isomers is 2.5× that of the cis-isomers. [31] Our observation is also in agreement with the known stability of trans-ozonide as supported by a higher steric hindrance imposed by cis-alkenes when the gas phase kinetics of ozone reaction with neutral cis- and trans- alkenes were measured.[38, 39] This is also consistent with detailed theoretical calculations which show that product branching in ozonolysis reactions are sensitive to the structure of the primary ozonide, which in turn is influenced by the double-bond geometry. Interestingly, we observed an abundant product ion at m/z 552.2938, which is likely to be an aldehyde arising from further oxidation of the Criegee ion in the form of formaldehyde loss under high ozone concentrations, as suggested above. In addition, the signature ion (m/z 184) from the phosphocholine head group loss can be observed, its low intensity and the facile cleavage under CID conditions further confirms the minimal collision energy applied in our experiments.

Figure 8.

OzID-MS spectrum of (A) PC (18:1(9Z)/18:1(9Z)) and (B) PC (18:1(9E)/18:1(9E)) obtained under optimized OzID settings: trap wave height =0.2 V, trap wave velocity = 8 m/s, transfer wave height = 0.4 V and transfer wave velocity = 247 m/s, trap entrance = 7 V and trap DC = 0.2 V.

Conclusions

The data presented here demonstrated that high quality OzID-MS spectra of protonated lipid ions can be obtained routinely from a traveling wave high resolution mass spectrometer. The modification of traveling wave height and velocity, as well as trap DC and entrance potential in the TriWave regions provided a significant enhancement in the ozonolysis efficiency in comparison to the default settings. As demonstrated, the relative abundances of the OzID characteristic aldehyde and Criegee ions can differentiate sn- positional and cis/trans isomers for standard lipids. In addition, the higher ozone concentration used in the current implementation of OzID further oxidizes the Criegee ions to form new product ions as a result of the loss of one formaldehyde from the metastable vinyl peroxide ions. Besides the enhancement of ozonolysis, the high mass accuracy achieved through high-resolution mass measurement on the Synapt G2 MS enables the assignment of OzID fragments without ambiguity.

While our work was under review, implementation of OzID on a similar platform (Synapt G2 Si) has been reported,[40] which explored traveling wave velocity and height for prolonged reaction time between ozone and lipid ion in the IMS region. Although the trap region is shorter in dimension compared to the IMS region and higher vacuum (1.0 e-2 mbar with IMS off) is also present in this region, by creating an ion dam to trap ions to elongate their reaction time with ozone, we achieved the highest efficiency OzID reported to date without sacrificing spectral acquisition rate (total trapping time is only 16.65 ms). Significant improvement in OzID efficiency achieved by Poad et al. by implementing OzID in the high pressure (~ 3 mbar) IMS cell, together with the manipulation of OzID reaction in the trap region detailed in our work, makes the Q-IMS-TOF MS a very versatile platform to implement this C=C specific dissociation technique for unsaturated lipid isomer analysis.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health grant (GM 104678). The authors thank the Triad Mass Spectrometry Facility at the UNCG Chemistry and Biochemistry Department and Dr. Daniel Todd for help with this work. The authors also thank reviewers of this manuscript for their valuable comments.

References

- 1.Fahy E, Cotter D, Sud M, Subramaniam S. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1811:637. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2011.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Oresic M, Hanninen VA, Vidal-Puig A. Trends Biotechnol. 2008;26:647. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2008.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Watson AD. J Lipid Res. 2006;47:2101. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R600022-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown HA, Murphy RC. Nat Chem Biol. 2009;5:602. doi: 10.1038/nchembio0909-602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang M, Wang C, Han RH, Han X. Prog Lipid Res. 2016;61:83. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2015.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yang L, Li M, Shan Y, Shen S, Bai Y, Liu H. J Sep Sci. 2016;39:38. doi: 10.1002/jssc.201500899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhao YY, Cheng XL, Lin RC. Int Rev Cell Mol Biol. 2014;313:1. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-800177-6.00001-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Perillo VL, Fernandez-Nievas GA, Valles AS, Barrantes FJ, Antollini SS. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1818:2511. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2012.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bordoni A, Lopez-Jimenez JA, Spano C, Biagi P, Horrobin DF, Hrelia S. Mol Cell Biochem. 1996;157:217. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4613-1275-8_27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang C, Wang M, Han X. Mol Biosyst. 2015;11:698. doi: 10.1039/c4mb00586d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Knittelfelder OL, Weberhofer BP, Eichmann TO, Kohlwein SD, Rechberger GN. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2014;951–952:119. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2014.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Narvaez-Rivas M, Zhang Q. J Chromatogr A. 2016;1440:123. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2016.02.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yang K, Cheng H, Gross RW, Han X. Anal Chem. 2009;81:4356. doi: 10.1021/ac900241u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jensen N, Gross M. Mass Spectrometry Reviews. 1988;1988:41. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mitchell TW, Pham H, Thomas MC, Blanksby SJ. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2009;877:2722. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2009.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang K, Zhao Z, Gross RW, Han X. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2009;877:2924. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2009.01.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hsu FF, Bohrer A, Turk J. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 1998;9:516. doi: 10.1016/S1044-0305(98)00012-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hsu FF, Turk J. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 1999;10:587. doi: 10.1016/S1044-0305(99)00035-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Han X. Lipidomics: Comprehensive Mass Spectrometry of Lipids. John Wiley & Sons; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hsu FF, Kuhlmann FM, Turk J, Beverley SM. J Mass Spectrom. 2014;49:201. doi: 10.1002/jms.3327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yan Y, Ubukata M, Cody RB, Holy TE, Gross ML. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2014;25:1404. doi: 10.1007/s13361-014-0901-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pittenauer E, Allmaier G. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2009;20:1037. doi: 10.1016/j.jasms.2009.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Griffiths WJ. Mass Spectrom Rev. 2003;22:81. doi: 10.1002/mas.10046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ma X, Chong L, Tian R, Shi R, Hu TY, Ouyang Z, Xia Y. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113:2573. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1523356113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ma X, Xia Y. Angewandte Chemie. 2014;126:2630. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ma X, Zhao X, Li J, Zhang W, Cheng JX, Ouyang Z, Xia Y. Anal Chem. 2016;88:8931. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.6b02834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stinson CA, Xia Y. Analyst. 2016;141:3696. doi: 10.1039/c6an00015k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Klein DR, Brodbelt JS. Anal Chem. 2017;89:1516. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.6b03353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brown SH, Mitchell TW, Blanksby SJ. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1811:807. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2011.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kozlowski RL, Mitchell TW, Blanksby SJ. Sci Rep. 2015;5:9243. doi: 10.1038/srep09243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pham HT, Maccarone AT, Thomas MC, Campbell JL, Mitchell TW, Blanksby SJ. Analyst. 2014;139:204. doi: 10.1039/c3an01712e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Poad BL, Pham HT, Thomas MC, Nealon JR, Campbell JL, Mitchell TW, Blanksby SJ. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2010;21:1989. doi: 10.1016/j.jasms.2010.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thomas MC, Mitchell TW, Harman DG, Deeley JM, Nealon JR, Blanksby SJ. Anal Chem. 2008;80:303. doi: 10.1021/ac7017684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Giles K, Williams JP, Campuzano I. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. 2011;25:1559. doi: 10.1002/rcm.5013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Giles K, Pringle SD, Worthington KR, Little D, Wildgoose JL, Bateman RH. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. 2004;18:2401. doi: 10.1002/rcm.1641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pringle SD, Giles K, Wildgoose JL, Williams JP, Slade SE, Thalassinos K, Bateman RH, Bowers MT, Scrivens JH. International Journal of Mass Spectrometry. 2007;261:1. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pham HT, Maccarone AT, Campbell JL, Mitchell TW, Blanksby SJ. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2013;24:286. doi: 10.1007/s13361-012-0521-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Martinez RI, Herron JT. J Phys Chem. 1988;92:4644. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mason SA, Arey J, Atkinson R. J Phys Chem A. 2009;113:5649. doi: 10.1021/jp9014614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Poad BL, Green MR, Kirk JM, Tomczyk N, Mitchell TW, Blanksby SJ. Anal Chem. 2017;89:4223. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.7b00268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]