Abstract

A heavy load of nitrogenous compounds reflects nutrient loss and influences water quality in large rivers. Nitrogenous concentrations and dual isotopes of nitrate were measured to ascertain the spatial and temporal distributions of nitrate transformation in the Yellow River, the second-longest river in China. Assessment of the long-term record indicates that [NO3 −–N] has increased by two-fold over the past three decades. Weekly observation of ammonium over a twelve-year period revealed high concentrations and suggests impairment of water quality, particularly since 2011. The estimated total dissolved nitrogen flux was 7.2 times higher in middle reaches than that at head waters. Anthropogenic nitrogen sources become more important in lower section of the upper reaches and middle reaches because of intensive agricultural activities and urban input. Nitrate in the lower reaches was mainly derived from transportation of upstream nitrate and point sources from cities. The spatial variation of ammonium and nitrate isotopes show that nitrification is a key process governing nitrogen transformation. Riverine biological processes could potentially be responsible for the shift of nitrate isotope signature. The first step to reducing nitrogen load and improving water quality will be containment and careful management of sources from urban input, sewage waste and irrigation runoff.

Introduction

Elevated concentrations of nitrogenous compounds in riverine environments is well demonstrated as having detrimental consequences for human and ecosystem health1, 2. Long-term monitoring is crucial to understanding nitrogen (N) dynamics and transformation in rivers. Over the past 50 years, the nitrogen load in watersheds has been heavily impacted by urbanization and land-use practices associated with intensification of agriculture and animal farming3, 4. N export to the sea by large rivers has increased significantly during the past five decades, with up to a six-fold increase in N fluxes caused by human activity observed in the United States2, 5, 6.

Nitrate and ammonium are the two dominant forms of reactive N entering the aquatic environment. The major sources of nitrate are atmospheric deposition, chemical fertilizers, soil organic nitrogen (SON), manure, and sewage effluents7. The nitrogen cycle in riverine systems involves several transformations, primarily nitrification, denitrification and biological uptake7, 8. Elucidation of the sources of nitrogen and riverine transformations that most influence N export is essential for understanding the sustainability of freshwater systems and environmental changes on the Earth’s surface4, 8. Paired stable nitrogen and oxygen isotopes are a powerful tool that is highly suitable for this research objective7–13.

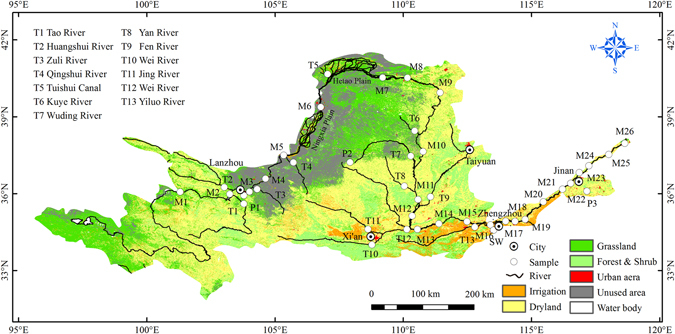

The Yellow River (YR) is the second longest rivers in China, with drainage area of 7.95 × 105 km2 and an annual average discharge of 5.8 × 1011 m3 and so is a significant drainage system globally. The Yellow River provides 140 million people with drinking and irrigation water in regions where the water supply per person is less than one third of the national average and water quality has suffered greatly from pollution14. Few long-term studies of riverine nitrogen in the YR have been conducted, and even fewer studies have used the dual isotopes of nitrate to identify its sources and behaviors15–20. In this study, samples representing the whole watershed were collected across the wet and dry seasons (Fig. 1) to understand the spatial variations in nitrogen speciation and concentration based on water chemistry and nitrate isotopic composition. Three representative sites were then identified from the main channel of YR for monthly sampling to further constrain temporal variation. These three sites are M1 in the headwaters with a relatively natural drainage area, M17 in the middle reaches, constituting 97% of the entire basin area and M23 in the lower reaches, respectively. The riverbed in the lower reaches is above ground level due to the combined effect of levee bank construction and sediment deposition from the highly sediment laden waters discharged from the middle reaches.

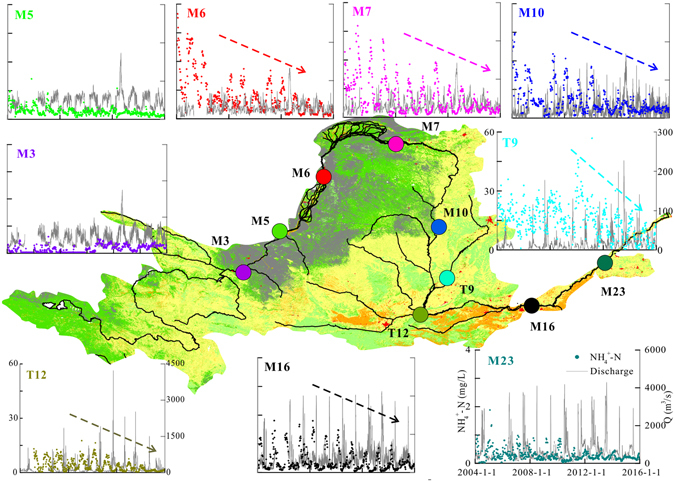

Figure 1.

Land use of Yellow River Basin and sampling sites where M indicates samples collected from the mainstream; T indicates samples collected from tributaries; P indicates precipitation samples and SW indicates sewage waste). Map produced using ArcGIS software 9.3 (http://www.arcgis.com/features/index.html).

Results

Seasonal variation in concentration of nitrogen compounds and chloride

The concentration of total dissolved nitrogen ([TDN]) ranged from 0.53 to 4.1 mg·L−1 (mean ± 1 SD = 2.6 ± 1.0 mg ·L−1, n = 26) in the main channel (in future referred to as mainstream) during the high flow season (Figure S1), which is lower than [TDN] in the low flow season (4.7 to 8.5 mg·L−1 and n = 16, mean = 6.0 ± 1.1 mg·L−1) (one-tailed t-test, p < 0.0001, α = 0.05). The [TDN] in tributaries ranged from 0.54 to 12.0 mg·L−1 with a mean value of 4.3 ± 3.6 mg·L−1 (n = 13) during the high flow season (Figure S1), and 7.0 to 33.5 mg·L−1 (n = 6) in the low flow season.

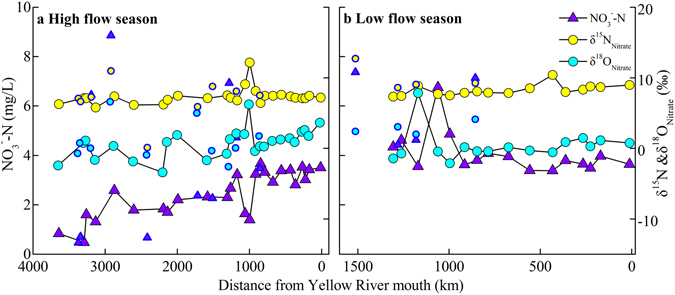

Nitrate was the dominant nitrogenous compound during both two flow seasons (Figure S1). [NO3 −–N] from main stream in the high flow season were generally lower than that in the low flow season (Fig. 2). The average [NO3 −–N] of 2.5 ± 0.9 mg·L−1 in the mainstream was higher than that of the two other major rivers (Songhua River 1.06 ± 0.69 mg·L−1and the Changjiang River 0.78 ± 0.3 mg·L−1) in China during the high flow season10, 21. All mainstream samples exhibited [NH4 +–N], dissolved organic nitrogen concentration ([DON]) and [NO2 −–N] of less than 0.5 mg·L−1 (Figure S1). Three tributary samples (T6, T9 and T10) had [NH4 +–N] of greater than 2.0 mg·L−1. The [NH4 +–N] and [DON] relatively increased relative to other compounds during the low flow season, particularly DON in the mainstream samples. The highest [NH4 +–N] and [NO2 −–N] was observed at T9 (Fen River) during both flow seasons, and the highest [DON] was observed at T9 during the low flow season (Figure S1).

Figure 2.

The distance variation of [NO3 −–N] and nitrate isotopes in Yellow River, scatter symbol indicates tributary samples.

The [Cl−] in mainstream ranged from 4.67 to 121.4 mg·L−1 (mean = 75.1 ± 29.8 mg ·L−1, n = 26) during the high flow season (Figure S1). High [Cl−] were detected in some of tributaries which ranged from 19.96 to 584.4 mg·L−1 (mean = 169.1 ± 193.0 mg ·L−1, n = 13) during the high flow season. Almost all samples had higher [Cl−] in the low flow season than that in the high flow season (Figure S1).

Monthly monitoring of nitrogen compound concentrations

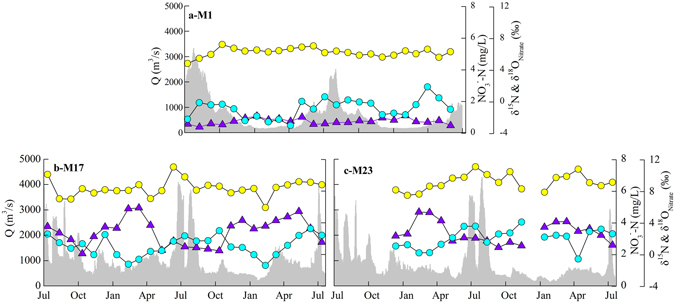

The TDN exhibited variation between the three chosen monthly monitoring sites. The [TDN] at M1 (0.59 to 1.7 mg·L−1, mean = 0.95 ± 0.30 mg·L−1, and n = 24) was lower than that at the other two sites (one-tailed t-test, p < 0.0001, α = 0.05) (Figure S2). The [TDN] at M17 ranged from 2.4 to 5.8 mg·L−1 (Figure S2), with a mean value of 4.0 ± 0.93 mg·L−1(n = 25). The [TDN] at site M23 ranged from 3.0 to 5.6 mg·L−1 (Figure S2), with a mean value of 4.0 ± 0.75 mg·L−1(n = 19). Furthermore, up to 80% of the samples at M17 and M23, and 54% of samples at M1 have a [NO3 −–N]/[TDN] ratio of greater than 80%, indicating that nitrate represented a substantial proportion of the TDN. The [NO3 −–N] at the M17 and M23 sites was three to four times higher than that at M1 sites. Three samples at M17 had [NO2 −–N] of greater than 0.30 mg·L−1 during the low flow season. The [TDN] also exhibited temporal variation from 2012 to 2014, with higher concentrations observed during the low flow season at all three sites. The [NO3 −–N] was higher during the dry seasons (from November to April) than in the wet season because of reduction in water fluxes and a relatively high load of nitrogen from anthropogenic inputs (Fig. 3), in agreement with the previous studies21.

Figure 3.

The variations of nitrate characteristics in monthly samples (symbols are same to Fig. 2).

The flux of N at sites monitored monthly was estimated using the concentration of TDN (C) and water discharge (Q) with the equation: F = C × Q. The average calculated TDN flux were 1.77 × 105 ston/year at M1, 12.7 × 105 ton/year at M17 and 11.0 × 105 ton/year at M23 based on the above equation.

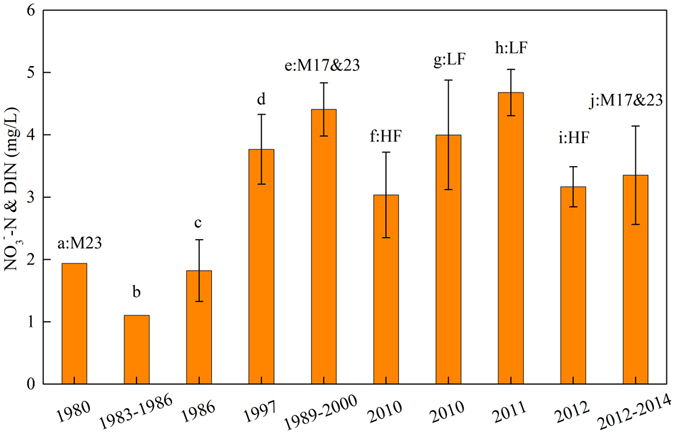

Long-term variation of N species in the Yellow River

As illustrated in Fig. 4, the [NO3 −–N] or dissolved inorganic nitrogen concentration ([DIN]) has increased over the past thirty years. For example, the average [NO3 −–N] at Luokou station (M23) had increased from 1.94 mg·L−1 (n = 24) in the 1980s to 3.4 ± 0.7 mg·L−1 (n = 19) during 2012 to 2014, which indicates that the [NO3 −–N] has increased by approximately two-fold during the past thirty years. High [NO3 −–N] was also found in the Yellow River during the low flow season in 2011 (Fig. 4). Results showed a relatively constant [NO3 −–N] (approximately 4.0 mg·L−1) in the middle and lower reaches of the YR in recent years. Although an increasing trend in [NO3 −–N] is observed over the past three decades, [NO3 −–N] during the period 2012 to 2014 was lower than the average [NO3 −–N] during 1989 to 2000.

Figure 4.

[NO3 −–N] (mean ± sd) in the Yellow River from Tongguan (M13) to the downstream in different years. The branch gives the range of the data, and the histogram gives the average value. (a) Samples from Luokou station (M23) during 1980 (n = 24)22; (b) Samples from lower part of river from November 1983 to August 198623; (c)Samples at August 1986 (n = 5)24; (d) Annual average concentration of NO3 − –N in the seven mainstream stations during 199717; (e) Average concentration of DIN in the two mainstream stations (M17 and M23) from 1989 to 200025; (f) Samples in the high flow season in this study (n = 14); (g) Samples in the low flow season in this study (n = 14); (h) Samples collected from Tongdaoguai (M9) to Lijin (M26) during October 2011(n = 13)16; (i) Sample in the high flow season during 2012 (n = 9)26; (j) Average concentration of NO3 − –N in two mainstream stations (M17 and M23) from 2012 to 2014 in this study.

Figure 5 shows the long-term variation of [NH4 +–N] during the period 2004–2015 at nine stations. Significant spatial and temporal variation is observed in the long-term monitoring data. The lowest [NH4 +–N] in the water sample was found at M3 station located in the upper reaches among all nine monitoring sites. A gradual increase occurs from station M3 to station M5, and a three-fold increase is observed between stations M5 and M6. In the middle reaches, [NH4 +–N] decreased between stations M7 and M16.

Figure 5.

The weekly variations of [NH4 +-N] at the main stations of Yellow River and two tributaries during 2004 to 2015. The data was obtained from Data Center in Ministry of Environmental Protection of the People’s Republic of China (http://datacenter.mep.gov.cn/). The left y-axis indicates [NH4 +-N] and right y-axis indicates water discharge (Q). The x-axis indicates date from 1/1/2004 to 1/1 2016. The range of y-axis is same for all mainstream sites and x-axis is same for all sites. Map produced using ArcGIS software 9.3 (http://www.arcgis.com/features/index.html).

The [NH4 +–N] in two major tributaries ranged from 0.19 to 60.7 mg·L−1 at T9 and from 0.14 to 17.6 mg·L−1 at T12, with mean values of 14.4 mg·L−1 and 3.71 mg·L−1, respectively, which are quite high concentrations for surface water. The values of [NH4 +–N] at T9 and T12 are higher than that of the other stations located in the mainstream (Table S1). Additionally, there is significant seasonal variation in [NH4 +–N] at these sites, with an increase observed from October to December and a decrease until April of the next year. The discharge between 2011 and 2015 did not change greatly at these sites (Fig. 5), but the maximum and average of [NH4 +–N] decreased at most stations between 2011 and 2015, which suggests that environmental protection measures have played an important role in water quality improvement in recent years.

Seasonal variation in isotopic composition of nitrate

The δ15Nnitrate values ranged from 7.3‰ to 13.7‰ with a mean value of 8.8 ± 1.6‰ (n = 22) during the low flow season and from 0.1‰ to 12.2‰ with a mean value of 6.9 ± 2.1‰ (n = 39) during the high flow season, respectively. The δ15Nnitrate values were higher during the low flow season than those during the high flow season (one-tailed t-test, p < 0.0001, α = 0.05). Tributary samples have lower average δ15N values (6.0‰, n = 13) than mainstream samples (7.3‰, n = 26) during the high flow season. Samples from the middle reaches had a higher average δ15Nnitrate value (8.0‰, n = 9) than that in the upper reaches (6.7‰, n = 9) and lower reaches (7.3‰, n = 8) during the high flow season. However, the average δ15Nnitrate value of samples in the middle reaches was lower than that in the lower reaches (7.8 ± 0.5‰ compared to 8.7 ± 0.5‰) during the low flow season (Fig. 2). The δ18Onitrate value did not show significant variation between the low and high flow seasons, ranging between −3.6–6.4‰ in the high flow season and −5.0–7.9‰ in the low flow season, respectively. The mainstream water samples generally exhibited narrow variation in nitrate isotopic values, with the exception of several samples during the low flow season. However, the δ15Nnitrate values in the tributaries during the low flow season varied significantly (Figs. 1 and 2).

Rain samples collected from the upper reaches and middle reaches yielded δ15Nnitrate of −5.5‰ and −3.3‰, and δ18Onitrate of 52.7‰ and 68.1‰, respectively, during the high flow season. One snow sample exhibited higher isotope values than the rain samples, with δ15Nnitrate = 10.1‰, and δ18Onitrate = 73.1‰ (Table S2). Two types of nitrogen fertilizers were collected from the lower reaches of the YR with δ15N = −0.1‰ for urea and −0.4‰ for di-ammonium phosphate (Table S2).

Monthly monitoring of nitrate isotopes

The nitrate isotopic values in water samples at M1 ranged from 4.9‰ to 7.3‰ for δ15N, with an average value of 6.3 ± 0.5‰ (n = 24), and from −3.0‰ to 1.9‰ for δ18Onitrate, with an average value of −0.8 ± 1.2‰ (n = 25). The δ15Nnitrate values varied from 6.0‰ to 11.1‰ in the samples at M17 and from 7.5‰ to 11.1‰ in the samples at M23 (n = 19), showing a wider nitrogen isotope range relative to that of the samples at M1. The δ18Onitrate values ranged from −1.3‰ to 3.3‰ at M17 and −0.5‰ to 4.2‰ at M23 (Fig. 3).

Discussion

The spatial variation of N species in the Yellow River Basin during 2010 and 2011

The upper section of the upper reaches (upstream of site M3) constitute 28% of the entire drainage area of the YR, contributing more than 56% of discharge14. High concentrations of [Cl−] in the municipal sewage and contaminated groundwater has previously been observed, which indicates that most of the Cl− was mainly of anthropogenic origin11, 27. Two tributaries (T1 and T2) and three mainstream samples (M1–M3) in the upper reaches (UR), with low population density (9.5 person/km2)28, had relative low [Cl−] and [NO3 −–N] for these five sites, which amounted to one third of those from other mainstream sites. This result suggests minimal contamination from human activities in this section of the YR. The degree of influence of industrial and agricultural activities on water quality gradually increased after site M3, such as the polluted tributaries of T3 and T4. A heavy load of Cl− and NO3 −–N in river water samples was also detected in the tributaries of the middle reaches (TMR). Ningxia Plain and Hetao Plain are important agricultural districts, where YR water is diverted for irrigation of farmland by a drainage network (shown in Fig. 1 between M5 and M9). Water returning to the YR from these farming regions through drainage channels and groundwater connected with farmland may be a source of nutrients derived from fertilizers and other agricultural sources. Previous studies have calculated that greater than 50% of water diverted for irrigation in these districts returns to the YR, resulting in a significant increase in the concentration of nitrogenous compounds14, 28, 29.

The concentration of nitrogen increased between M12 and M13, following the input of two major tributaries (T9, Fen River and T12, Wei River) and indicating high nitrogen concentrations in these tributaries. A significant decrease in [NO3 −–N] was observed between two water conservancy projects, Sanmen Valley Reservoir (near M14) and Xiaolangdi Reservoir (near M15), where water is retained for prolonged periods (Fig. 2). Although the lower reaches (LR) have a high population density (4717 person/km2) and developed economy28, [NO3 −–N] showed only a slight increase from 2.9 to 3.5 mg·L−1 between sites M19 and M26, which may be related to the small number of tributaries entering the main body of the YR. The primary inputs in this section are point sources from industry and domestic waste in city and urban areas.

Monthly variation of N species at monitoring sites during 2012 to 2014

The monthly trend in NO3 −–N differs between the two years over which continuous monthly data was collected (Fig. 3), which suggested that nitrate concentration was determined by a variety of factors. The estimation of N flux (see results) also indicates that the tributary river between M1 and M17 contributes approximately 86% nitrogen load. Both the concentration and N flux data suggest that the output of N from the YR is mainly derived from the lower section of the upper reaches (M3 to M9) and middle reaches.

The significant seasonal variation in precipitation and agricultural activities may affect riverine nitrogen sources and budget. There are two water discharge peaks, from March to May and from May to October (Fig. 3). The low [TDN] is likely to be due to dilution by snowmelt during the first peak and precipitation during the second. This period is otherwise characterised by high nitrogen input from agricultural activities; the nitrogen flux increased from both point and diffuse sources. The [NO3 −–N] was generally higher at M23 during the second peak than that at M17, suggesting that the relatively constant point sources are more likely to be responsible for the nitrogen concentrations observed in this reach of the YR (Fig. 3).

Spatial and temporal variation of nitrate sources in the Yellow River

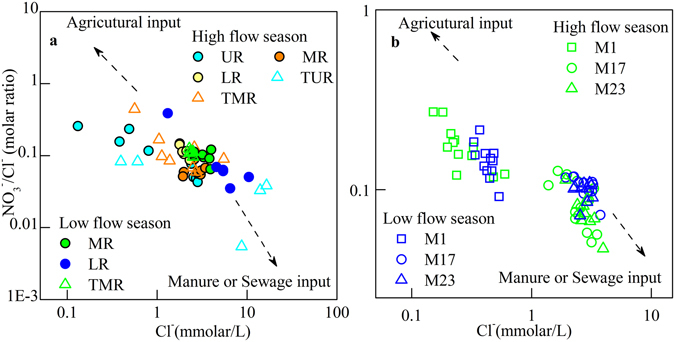

The ratio of [NO3 −]/[Cl−] can be used as an indicator of mixing or biological processes affecting nitrate distribution in the watershed, due to the conservative chemical behavior of chloride10, 11. Generally, chemical fertilizer contain high concentrations of NO3 − contents and has a high ratio of [NO3 −]/[Cl−], and sewage waste has high [Cl−] content and a low ratio of [NO3 −]/[Cl−]11, 27. Six upstream samples (Fig. 6a) exhibited low [Cl−] content and similarly δ15N, suggesting a constant natural nitrogen source. The [Cl−] in the mainstream samples increased from M5, and the molar ratio of [NO3 −]/[Cl−] decreased, which suggested the contribution of sewage waste is increasing, especially during the low flow season. Although the [Cl−] and [NO3 −]/[Cl−] in tributaries exhibited more variation than mainstream samples during the high flow season (Fig. 6a), the small variation in the mainstream values indicates that sufficient mixing occurs in the mainstream to homogenize the signature. The monthly monitored sites (Fig. 6b) displayed significant variation from the low [Cl−] and molar ratio of [NO3 −]/[Cl−] at M1, which is similar to the water samples from the upstream sites (Fig. 6a).

Figure 6.

(a) The relationship between [Cl−] and [NO3 −]/[Cl−] for spatial data during the high and low season, YR indicates Yellow River; (b) The relationship between [Cl−] and [NO3 −]/[Cl−] for time series data at three selected sites. UR stands for mainstream samples at upper reaches of YR. MR means mainstream samples at middle reach of YR. LR means mainstream samples at lower reach of YR. TUR means tributaries at UR. TMR means tributaries at MR.

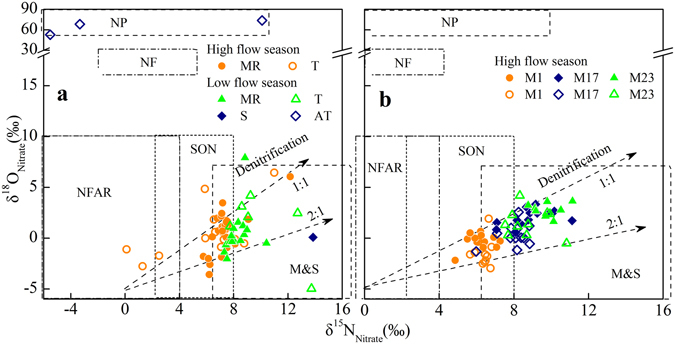

The isotopic composition of various nitrogen sources in the study area is shown in Table S2. The content of SON in soil profiles in Loess Plateau decreased and δ15NSON increased from top to bottom, and ranged from 1.9 to 8.2‰ (n = 95) with low isotope values in the topsoil of the Loess Plateau (1.9 to 5.1‰, n = 5)30. The major forms of N in sewage and hydrolysis fertilizers are NH4 + (NH3) and organic N, which are subsequently converted into nitrate or N2 by nitrification, volatilization and denitrification. Nitrate derived from sewage with a higher δ15N value than that of raw material is usually characterized by δ15N between 7‰ and 25‰8, 27. The δ18Onitrate values of nitrate derived from nitrification of ammonium from urea fertilizers and rain (NFAR) (Fig. 7) are related to the oxygen isotopic composition of O2 and H2O in the surrounding environment with a chemical stoichiometric ratio of 1:2. The δ18Owater ranged from −10.7 to −7.6‰ in all water samples except for one sample (T5) with high δ18Owater (−3.0‰), which was published in our previous study for the spatial sites31. Consequently, nitrate derived from microbial nitrification has δ18Onitrate values ranging from 0.7 to 2.8‰. However, several factors would influence the δ18Onitrate values during nitrification, such as O exchange between NO2 − and H2O and the diffusion of oxygen, which may lead to a ratio of oxygen atoms from water and O2 of greater than 2:1 during nitrification7, 32–34. In this study, more than 50% of water samples had δ18Onitrate values lower than 0.7‰, suggesting nitrification occurred under low oxygen conditions. Under these anoxic condition, oxygen atoms from water may be a more important source than free oxygen during nitrification. Therefore, the sewage and riverine nitrate with low δ18Onitrate values would be primarily impacted by the nitrification process. Nitrate fertilizer (NF) formed from atmospheric oxygen has a distinctive δ18O value (18 to 22‰), which is same to the δ18Oair (23.5‰) (Fig. 7)7.

Figure 7.

Relationship between δ15Nnitrate and δ18Onitrate values during 2010 to 2011 (a) and at three monthly sites during 2012 to 2014 (b). MR indicates main reaches samples. T stands for tributaries samples. S stands sewage waste sample. AT stands for atmospheric precipitation samples. Other abbreviations for sources were introduced in the text.

Nitrate derived from the atmosphere precipitation (NP) via photochemical reactions involves compounds enriched in18O and thus has higher δ18Onitrate values than other nitrate sources (Fig. 7)7. To estimate the contribution of atmospheric deposition to riverine nitrate concentrations, a mixing-model based on mass balance equations was used (Supplementary Equations). The average δ18Onitrate value from atmospheric deposition was assumed to be 64.8‰ and the δ18Owater during nitrification was calculated to be 0.7 to 2.8‰. If the contribution from atmospheric deposition is 10%, the δ18Onitrate value from mixing these two sources would range from 7.1‰ to 9.0‰, based on the mixing model. The δ18Onitrate values were between −3.0‰ and 1.9‰, which indicates that the contribution from atmospheric precipitation was limited. Therefore, atmospheric nitrate is not a major source for the YR, which is in agreement with previous studies based on limited sampling campaigns16, 35.

The riverine nitrate in the Yellow River might be impacted by various factors in different zone due to sparse distribution of dual isotopic characteristics (Fig. 7a). The riverine nitrate in tributaries in the upper reaches would be derived from the nitrification of manure and sewage waste (M&S) as well as chemical fertilizers, based on the dual isotopic pattern of nitrate. The Fen River and Wei River entered the mainstream with high NO3 −–N, and low δ15Nnitrate (1.3‰, 2.5‰, respectively) and δ18Onitrate (−2.8‰, −1.7‰, respectively) values, indicating that chemical fertilizer was the major source for these two rivers, similar to the results of other study16. Although these two river catchments had high population densities, the abundant rainfall during the high flow season and routine application of fertilizers may lead to a major contribution from chemical fertilizers. The isotopic values of these two tributaries changed significantly between the two seasons, with high isotope values in the low flow season. These two major tributaries had high NH4 +–N during both two seasons, but the samples had higher [NH4 +–N] and δ15N values during the low flow season than that during the high flow season, indicating that manure and sewage waste were the major source instead of nitrogen from agriculture. The high DON and nitrate isotopic composition (δ15N: 7.7–12.7‰; δ18Onitrate: 1.2–4.2‰) of the water samples collected from other tributaries showed that manure and sewage waste were major contributors to riverine nitrate during this period.

The small monthly variation of dual isotopes (M1, Fig. 6b) suggests that nitrate sources were constant in the headwaters. The catchment area for M1 is the alpine zone, where more than 60% of land use is natural grassland28. Therefore, SON might be a more important nitrate source. Nitrate concentration increased slightly during the low flow season, when the level of microbial activity is lower due to low temperature conditions, and the average nitrate concentration (0.75 ± 0.19 mg·L−1) suggests the presence of other nitrogen sources with high nitrogen concentrations and similar δ15N values (4.9 to 7.3‰). Animal manure produced by free grazing of livestock in this region may be responsible for the variation in nitrate concentrations. Therefore, nitrate in the upper reaches (M1) is mainly derived from mineralization of SON and animal manure. The increased [NH4 +–N] at long-term monitoring sites located in the lower section of the upper reaches (M3–M9), suggests an anthropogenic source of N, such as nearby urban areas. Although fertilizer application and precipitation are limited during the low flow season, flood irrigation would allow nitrogenous fertilizers to infiltrate the groundwater, resulting in nutrient discharge into rivers36. Therefore, sewage waste and chemical fertilizer may be responsible for the high [NH4 +–N]. Riverine nitrate in the middle reaches exhibited a wider range in δ15N than that in the upper and lower reaches, which suggests that multiple nitrogen sources contribute to the middle reaches across different seasons. The distribution of nitrate isotope values in the middle reaches indicates that nitrate sourced in the upper reaches of the YR and the tributaries located in the middle reaches are impacted by multiple sources, including chemical fertilizers, SON, manure and sewage waste. The higher isotope values of nitrate at M17 and M23 than at M1 indicate the addition of further sources between these sites that are enriched in15N, such as manure and sewage waste, or that riverine nitrate is affected by isotopic fractionation by denitrification. The [NO3 −–N] is higher in the lower reaches, but the isotopic values showed no significant change, indicating similar sources to those encountered in the middle reaches.

Overall, it can be concluded that the tributaries in the middle reaches were polluted by manure or sewage waste and this dominated the nitrate pool. Nitrate in samples from the upper reaches would be from SON, while agricultural sources, chemical fertilizer and manure waste dominate in the lower section of the upper reaches. The middle reaches are influenced by multiple sources and may be affected by the significant variations observed in tributaries during high flow season. The concentration of nitrogen and difference in isotopic signature of nitrate indicates that manure and sewage waste was a larger contributor to the Yellow River Basin during the low flow season.

Major transformations in the riverine nitrogen cycle

The main processes that control nitrogen dynamics in ecosystems commonly result in an increase in the δ15N of the substrate, unless the reactions go to completion7, such as ammonia losses from organic matter within manure, which may result in δ15N values higher than 25‰27. The middle and lower reaches of the basin drained a greater area of agricultural land and were subject to fertilizer application during the high flow season. In theory, the nitrogen isotope values during this season may have low values close to 0‰. However, the measured compositions were greater than the theoretical values, which indicates that volatilisation may occur and enrich the heavy isotopes. Xing and Zhu (2002) reported that the loss of N through volatilization of urea was 22% in agricultural land based on mass budget37. The volatilization process follows the Rayleigh distillation equation with an overall fractionation effect of approximately −20‰38. Based on the conversion factors, the Rayleigh fractionation equation, and δ15N values of nitrogenous fertilizers collected within the basin, the δ15N of the residual fertilizer nitrate would be 4.6‰, which is close to that observed in tributary samples from the middle reaches.

Nitrification is a multi-step oxidation process mediated by several different autotrophic organisms. Several samples showed δ18Onitrate values higher than the theoretical δ18Onitrate value (2.8‰), indicating that nitrification was the major transformation in the nitrogen cycle. Additionally, the long-term observation of ammonium showed high concentration in the low flow season and low concentrations during the high flow season with warm temperature, indicating that nitrification was the dominant process controlling the temporal variation of ammonium. Meanwhile, the increasing trends of oxygen isotopic values in water and oxygen isotopic values of nitrate along the flow path suggest nitrification played an important role in production of nitrate31.

However, nitrate isotopic values would increase during other biological processes in the riverine system, such as algae uptake and denitrification7, 39. The decreased concentration and highest dual isotopes of nitrate in the mainstream of the Xiaolangdi water conservancy project (M15, Fig. 2) suggested riverine nitrate may be affected by algae assimilation uptake and denitrification. As indicated by Fig. 7b, a positive relationship between δ15N and δ18Onitrate was observed (δ18Onitrate = 0.79 × δ15N-5.47, R2 = 0.49, p < 0.0001), particularly for samples collected in the high flow season (δ18Onitrate = 0.73 × δ15N-4.53, R2 = 0.70, p < 0.0001). The decreased nitrate concentration and increased δ18Onitrate value at M1 and M17 sites during the high flow season (Fig. 3) may reflect dilution, an increased contribution from atmospheric nitrate, and denitrification. Liu et al.16 reported that the nitrate transformation might be mainly influenced by microbial denitrification as the high concentration of suspended sediment makes it difficult for algae/phytoplankton to grow16. High concentration of suspended sediment can accelerate rates of denitrification, even in aerobic waters16, 18. Moreover, denitrification could remove N in riverine water column at equivalent or higher rates than headwaters40. Therefore, the increased δ18Onitrate values during the high flow season indicate that nitrate isotopes would be affected by denitrification in this studied river.

Nitrate characteristics in the Yellow River compared to other large rivers worldwide

Table 1 lists [NO3 −–N] and isotopic composition of nitrate in large rivers obtained at long-term monitoring sites, which collect biweekly or monthly samples for more than one year. Due to the influence of snowmelt-derived water, the nitrate characteristics show lower [NO3 −–N] and δ15N, and higher δ18Onitrate in Saint Lawrence River than in the other four large rivers9, 41, 42. Although the upper reaches of the YR also includes the snow region, the nitrate characteristics at the M17 site (Table 1) appear to differ from those of the Saint Lawrence River. Among the four large rivers worldwide, the [NO3 −–N] is the highest in the YR. Nitrate isotopes are similar with those of two German large rivers that are highly impacted by human activities, with higher δ15N and lower δ18Onitrate than that of the Saint Lawrence River and Mississippi River9, 41, 42.

Table 1.

Nitrate characteristics for long-term monitoring sites in large rivers.

| River | Length | Basin Area | Mean- [NO3 −–N] | Mean-δ15Nnitrate | Mean-δ18Onitrate | Sample Number |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| km | 105 km2 | mg/L | ‰ | ‰ | ||

| Mississippi River42 | 6020 | 32.2 | 1.45 ± 0.5 | 7.7 ± 0.3 | 4.6 ± 0.3 | 22 |

| Yellow River | 5465 | 7.95 | 3.4 ± 0.86 | 8.4 ± 1.1 | 1.2 ± 1.3 | 25 |

| Saint Lawrence River41 | 1287 | 3.00 | 0.43 ± 0.08 | 5.7 ± 0.7 | 5.4 ± 1.4 | 41 |

| Rhine River9 | 1320 | 1.85 | 2.7 ± 0.7 | 8.2 | 0.4 | 24 |

| Elbe River9 | 1165 | 1.48 | 2.6 ± 1.4 | 8.5 | 1.3 | 16 |

These rivers exhibited seasonal variations is nitrate pool composition, such as low NO3 −–N during the high flow season and high δ15N during the low flow season, reflecting variation in hydrological and nitrate sources43, 44. The high contribution of urban sewage waste may be responsible for the high δ15N during the low flow season. Nitrate isotopic composition is closely related to the nitrate sources and water flow in the Illinois River, with isotope values in river samples close to that of tile drain samples during the high flow period and treated wastewater during the low flow period39. The difference of nitrate isotopic values among M1, M17 and M23 sites in the present study also suggests that nitrate isotopic composition depends on the sources, as in M1, and the water flow state, as observed in the seasonal variation between flow seasons in M17 and M23.

In this study, the long-term variations of nitrogen compound concentrations suggest nitrate is the dominant nitrogen compound during both flow seasons. The tributaries exhibit high [NO3 −–N] and [NH4 +–N]. Moreover, the [DON] and [NH4 +–N] exhibit seasonal variation, with high concentrations in the low flow season. Nitrogen sources in two major tributaries are different, due to agricultural import during the high flow season and manure and sewage waste in the low flow season. The middle reaches in the YR received nitrate from tributaries with a distinct agricultural signature and urban input. The dual isotopic compositions of nitrate during low flow season indicate an increased contribution of sewage waste. Moreover, the isotopic compositions of nitrate and the hydraulic conditions imply that lower reaches riverine nitrate is mainly derived from sewage waste from cities, particularly domestic and industrial waste. The trends of [NO3 −–N] and [NH4 +–N] observed in monthly samples suggest nitrogen pollution has decreased. The results also suggest that riverine processes affect nitrogen transformation and transport processes, such as nitrification and denitrification. The nitrogen concentrations in the YR are relatively high compared with other large rivers around the world. The urban input of sewage waste and irrigation water should be managed to further reduce the nitrogen load and improve water quality in the Yellow River Basin.

Methods

Study Area

The Yellow River (Huang River), located between 32°10′N–41°50′N and 95°53′E–119°10′E, is the world's fifth longest river and the second longest river in China, with a length of 5464 km. The mainstream of the YR is commonly divided into three sections, the upper reaches (M1–M9), middle reaches (M9–M18) and lower reaches (M18–M26) (detail in Table 1 and Fig. 1). The upper reaches can also be divided into two sections, the upper section which is upstream of site M3 and the lower section between sites M4 and M9. An unusually large amount of mud and sand (37.8 kg/m3) is discharged into the river from the Loess Plateau located in the middle reaches which constitutes 92% of riverine silts, making it the most sediment-laden river in the world and the spectacle after which it is named14. The riverbed in the lower reaches is elevated above the ground surface by more than 10m in some areas, due to the building of levee banks to combat flooding accompanied by continuous sediment deposition due to the extremely high sediment transport from the middle reaches. The abundant hydrodynamic resources distributed in the middle reaches where the elevation of the river drops 890 m make it highly suitable for hydroelectric power generation. Two major water conservancy projects (Sanmen Valley Reservoir near M14 and Xiaolangdi Reservoir near M15) are located in the middle reaches. The two largest tributaries (Wei River and Fen River) of the YR are in the middle reaches.

The Yellow River Basin has a continental monsoon climate and most of the basin belongs to the temperate-arid and semi-arid climates14, 28. The three primary agricultural production basins are Ningxia Plain and Hetao Plain, Fen Wei Basin (Fen River and Wei River) and lower reaches. In the agricultural regions, synthetic fertilizers are generally applied twice a year, in July for summer crops and October for winter crops. However, manure is also applied periodically throughout the year. Three large cities, Xi’an, Zhengzhou, and Jinan, each have populations of greater than seven million people, and more than three million people live in urban areas surrounding the mainstream or major tributaries. Dry land area accounts for 80% of the basin area. The cultivated land is mainly in the middle and lower reaches, with 7.2% irrigated agricultural area. The majority of grazing land is located in the upper reaches. Grassland, cropland, wetlands, and urban areas account for 60%, 29.5%, 1.1%, and 6% respectively28.

Sampling campaigns

The seasonal water samples were collected from the mainstream of the YR and its major tributaries in August of 2010 and February of 2011, corresponding to the high and low flow seasons respectively. Water samples comprised 26 mainstream water samples (M1–M26), 13 tributary water samples (T1–T13), and 2 rain water samples during the high flow season. The upper reaches were frozen in winter, resulting in low water discharge into the mainstream. Therefore, water samples were collected from the middle and lower reaches during the low flow season, comprising 22 river samples (16 mainstream and 6 tributaries), one snow sample and one sewage sample. Additionally, three sites (M1, M17 and M23) were selected for monthly sampling from July 2012 to June 2014. Water samples were filtered through 0.45-µm cellulose-acetate filter paper at the field site and collected in 100mL opaque plastic bottles for nutrient and nitrate isotope analysis, and samples for isotopic analysis were refrigerated at 4°C.

Laboratory analysis

Anion (Cl− and NO3 −) concentrations (mg/L) were determined using a Dionex ion chromatography (IC) system 90 (Dionex Corp., Sunnyvale, CA, USA). The N concentrations (mg/L) of NH4 +, NO2 −, and TDN in the filtered samples were analyzed using an automatic flow analyzer (SKALAR Sans Plus Systems) after the field work. The nitrogen detection limit was 5 μg·L−1 for NO2 −–N, 10 μg·L−1 for NO3 −–N 10 μg·L−1for NH4 +–N, and 20 μg·L−1 for TDN. The DON concentration was calculated by subtracting DIN (the sum of NO3 −, NO2 −, and NH4 + concentrations) from the TDN. Denitrifer bacteria were used to transform the nitrate to nitrous oxide (N2O). Isotopic analysis of the N2O product was performed using an isotope ratio mass spectrometer after purification using Trace Gas Pre-concentrator unit45. For calibration, four international nitrate (USGS-32, USGS-34, USGS-35 and IAEA-N3) and experimental reference materials were treated in an identical manner as the filtered water samples. The analytical precision for the samples analyzed in duplicate was 0.3‰ for δ15N and 0.5‰ for δ18O of nitrate.

The isotope ratios are reported as delta (δ) expressed in per mil (‰) using the usual delta notation:

| 1 |

where R = 15N/14N or18O/16O. The15N/14N reference was N2 in air and the18O/16O reference was Vienna standard mean ocean water.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

Two anonymous reviewers and Prof. A. Baker are thanked for their valuable comments on an earlier version of this manuscript. We thank Prof. Susan Waldron and Dr Sarah Buckerfield for fruitful discussions and editing. We also thank Drs. Hong-Ming Cai, Dong Zhang, Xiao-Dong Li, Li-Li Zhang and Bai-Ling Fan for their help during the sample collection. This study was financially supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 41403105, 41422303), the Ministry of Science and Technology of China through Grant (No. 2016YFA0601000) and CRP F33021 by the IAEA.

Author Contributions

S.L. Li and C.Q. Liu designed the study. F.J. Yue, S.L. Li, H. Ding and Z.Q. Zhao conducted the field sampling; F.J. and S.L. conducted data analysis. The manuscript was written by F.J., S.L. and C.Q. All of authors discussed the results and reviewed the manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at doi:10.1038/s41598-017-08756-7

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Si-Liang Li, Email: siliang.li@tju.edu.cn.

Cong-Qiang Liu, Email: liucongqiang@vip.skleg.cn.

References

- 1.Fewtrell L. Drinking-water nitrate, methemoglobinemia, and global burden of disease: a discussion. Environ. Health. Persp. 2004;14:1371–1374. doi: 10.1289/ehp.7216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McIsaac GF, David MB, Gertner GZ, Goolsby DA. Eutrophication: nitrate flux in the Mississippi River. Nature. 2001;414:166–167. doi: 10.1038/35102672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Galloway JN, et al. Transformation of the nitrogen cycle: recent trends, questions, and potential solutions. Science. 2008;320:889–892. doi: 10.1126/science.1136674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gruber N, Galloway JN. An Earth-system perspective of the global nitrogen cycle. Nature. 2008;451:293–296. doi: 10.1038/nature06592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Howarth RW, Marino R. Nitrogen as the limiting nutrient for eutrophication in coastal marine ecosystems: Evolving views over three decades. Limnol. Oceanogr. 2006;51:364–376. doi: 10.4319/lo.2006.51.1_part_2.0364. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boyer EW, et al. Riverine nitrogen export from the continents to the coasts. Global Biogeochem. Cy. 2006;20 doi: 10.1029/2005GB002537. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kendall, C., Elliott, E. M. & Wankel, S. D. Tracing anthropogenic inputs of nitrogen to ecosystems. Stable isotopes in ecology and environmental science 375–449 (2007).

- 8.Mayer B, et al. Sources of nitrate in rivers draining sixteen watersheds in the northeastern US: Isotopic constraints. Biogeochemistry. 2002;57:171–197. doi: 10.1023/A:1015744002496. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Johannsen A, Dahnke K, Emeis K. Isotopic composition of nitrate in five German rivers discharging into the North Sea. Org. Geochem. 2008;39:1678–1689. doi: 10.1016/j.orggeochem.2008.03.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li SL, et al. Assessment of the sources of nitrate in the Changjiang River, China using a nitrogen and oxygen isotopic approach. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2010;44:1573–1578. doi: 10.1021/es902670n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu CQ, Li SL, Lang YC, Xiao HY. Using δ15N and δ18O values to identify nitrate sources in karst ground water, Guiyang, Southwest China. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2006;40:6928–6933. doi: 10.1021/es0610129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jin Z, et al. Comparing watershed black locust afforestation and natural revegetation impacts on soil nitrogen on the Loess Plateau of China. Sci Rep-Uk. 2016;6 doi: 10.1038/srep25048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu WG, Xing M. Isotopic indicators of carbon and nitrogen cycles in river catchments during soil erosion in the arid Loess Plateau of China. Chem Geol. 2012;296–297:66–72. doi: 10.1016/j.chemgeo.2011.12.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yellow River Conservancy Commission. Yellow River Water Resources (In Chinese) (The Yellow River Publishing House of the Water Resources, 2012).

- 15.Tong YD, et al. Nutrient Loads Flowing into Coastal Waters from the Main Rivers of China (2006–2012) Sci Rep-Uk. 2015;5 doi: 10.1038/srep16678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu T, Wang F, Michalski G, Xia X, Liu S. Using 15N, 17O, and 18O to determine nitrate sources in the Yellow River, China. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013;47:13412–13421. doi: 10.1021/es403357m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xia XH, Zhou JS, Yang ZF. Nitrogen contamination in the Yellow River basin of China. J. Environ. Qual. 2002;31:917–925. doi: 10.2134/jeq2002.0917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu T, Xia X, Liu S, Mou X, Qiu Y. Acceleration of Denitrification in Turbid Rivers Due to Denitrification Occurring on Suspended Sediment in Oxic Waters. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013;47:4053–4061. doi: 10.1021/es304504m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tao Y, Wei M, Ongley E, Li Z, Jingsheng C. Long-term variations and causal factors in nitrogen and phosphorus transport in the Yellow River, China. Estuar. Coast. Shelf S. 2010;86:345–351. doi: 10.1016/j.ecss.2009.05.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen J, He D, Zhang N, Cui S. Characteristics of and human influences on nitrogen contamination in Yellow River system, China. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2004;93:125–138. doi: 10.1023/B:EMAS.0000016796.51583.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yue F-J, et al. Analysis of δ15N and δ18O to identify nitrate sources and transformations in Songhua River, Northeast China. J. Hydrol. 2014;519:329–339. doi: 10.1016/j.jhydrol.2014.07.026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Meybeck M. Carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorus transport by world rivers. Am. J. Sci. 1982;282:40l–450. doi: 10.2475/ajs.282.4.401. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang J, Huang WW, Liu MG, Cui JZ. Eco-Social Impact and Chemical Regimes of Large Chinese Rivers - a Short Discussion. Water Res. 1994;28:609–617. doi: 10.1016/0043-1354(94)90011-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang J, Huang W, Letolle R, Jusserand C. Major element chemistry of the Huanghe (Yellow River), China-weathering processes and chemical fluxes. J. Hydrol. 1995;168:173–203. doi: 10.1016/0022-1694(94)02635-O. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen, J. & Yu, T. Characteristics of nitrogen loss modulus in the Yellow River Basin. J. Agro-Environ. Sci. 23, 833–838 In Chinese (2004).

- 26.Fan BL, et al. Characteristics of carbonate, evaporite and silicate weathering in Huanghe River basin: A comparison among the upstream, midstream and downstream. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2014;96:17–26. doi: 10.1016/j.jseaes.2014.09.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Widory, D., Petelet-Giraud, E., Negrel, P. & Ladouche, B. Tracking the sources of nitrate in groundwater using coupled nitrogen and boron isotopes: A synthesis. Environ. Sci. Technol. 39 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Kusuda, T. The Yellow River: Water and Life (World Scientific, 2010).

- 29.Jia Z, et al. The impact of improving irrigation efficiency on wetland distribution in an agricultural landscape in the upper reaches of the Yellow River in China. Agr. Water Manage. 2013;121:54–61. doi: 10.1016/j.agwat.2013.01.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li, L. B. Isotope geochemistry of soil carbon and nitrogen in typical soil types in Guizhou karstic and Loess Plateau areas Doctor thesis, University of Chinese Academy of Sciences (2012).

- 31.Li S-L, et al. The O and H isotope characteristics of water from major rivers in China. Chin. J. Geochem. 2015;34:28–37. doi: 10.1007/s11631-014-0015-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kool DM, Wrage N, Oenema O, Van Kessel C, Van Groenigen JW. Oxygen exchange with water alters the oxygen isotopic signature of nitrate in soil ecosystems. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2011;43:1180–1185. doi: 10.1016/j.soilbio.2011.02.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fang Y, et al. Low δ18O values of nitrate produced from nitrification in temperate forest soils. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2012;46:8723–8730. doi: 10.1021/es300510r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Casciotti KL, McIlvin M, Buchwald C. Oxygen isotopic exchange and fractionation during bacterial ammonia oxidation. Limnol. Oceanogr. 2010;55:753–762. doi: 10.4319/lo.2009.55.2.0753. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Barnes RT, Raymond PA, Casciotti KL. Dual isotope analyses indicate efficient processing of atmospheric nitrate by forested watersheds in the northeastern US. Biogeochemistry. 2008;90:15–27. doi: 10.1007/s10533-008-9227-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang, X. J., Ren, F. C., Zhao, Y., Luo, J. H. & Chen, X. Q. Seasonal Changes of Nitrate Leaching in Greenhouse Vegetable Field in Yellow River Irrigation Region of Ningxia, China. J. Agro-Environ. Sci. 33, 1964–1972, (In Chinese) (2014).

- 37.Xing GX, Zhu ZL. Regional nitrogen budgets for China and its major watersheds. Biogeochemistry. 2002;57:405–427. doi: 10.1023/A:1016508323200. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Billy C, Billen G, Sebilo M, Birgand F, Tournebize J. Nitrogen isotopic composition of leached nitrate and soil organic matter as an indicator of denitrification in a sloping drained agricultural plot and adjacent uncultivated riparian buffer strips. Soil. Biol. Biochem. 2010;42:108–117. doi: 10.1016/j.soilbio.2009.09.026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Granger J, Sigman DM, Needoba JA, Harrison PJ. Coupled nitrogen and oxygen isotope fractionation of nitrate during assimilation by cultures of marine phytoplankton. Limnol. Oceanogr. 2004;49:1763–1773. doi: 10.4319/lo.2004.49.5.1763. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Reisinger AJ, Tank JL, Hoellein TJ, Hall RO. Sediment, water column, and open-channel denitrification in rivers measured using membrane-inlet mass spectrometry. J. Geophys. Res-Biogeo. 2016;121:1258–1274. doi: 10.1002/2015JG003261. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Thibodeau B, Helie JF, Lehmann MF. Variations of the nitrate isotopic composition in the St. Lawrence River caused by seasonal changes in atmospheric nitrogen inputs. Biogeochemistry. 2013;115:287–298. doi: 10.1007/s10533-013-9834-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.BryantMason A, Xu YJ, Altabet M. Isotopic signature of nitrate in river waters of the lower Mississippi and its distributary, the Atchafalaya. Hydrol. Process. 2013;27:2840–2850. doi: 10.1002/hyp.9420. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nestler A, et al. Isotopes for improved management of nitrate pollution in aqueous resources: review of surface water field studies. Environ. Sci. Pollut. R. 2011;18:519–533. doi: 10.1007/s11356-010-0422-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Panno SV, Kelly WR, Hackley KC, Hwang HH, Martinsek AT. Sources and fate of nitrate in the Illinois River Basin, Illinois. J. Hydrol. 2008;359:174–188. doi: 10.1016/j.jhydrol.2008.06.027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.McIlvin MR, Casciotti KL. Technical Updates to the Bacterial Method for Nitrate Isotopic Analyses. Anal. Chem. 2011;83:1850–1856. doi: 10.1021/ac1028984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.