ABSTRACT

Non-aureus staphylococci (NAS), the bacteria most commonly isolated from the bovine udder, potentially protect the udder against infection by major mastitis pathogens due to bacteriocin production. In this study, we determined the inhibitory capability of 441 bovine NAS isolates (comprising 26 species) against bovine Staphylococcus aureus. Furthermore, inhibiting isolates were tested against a human methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) isolate using a cross-streaking method. We determined the presence of bacteriocin clusters in NAS whole genomes using genome mining tools, BLAST, and comparison of genomes of closely related inhibiting and noninhibiting isolates and determined the genetic organization of any identified bacteriocin biosynthetic gene clusters. Forty isolates from 9 species (S. capitis, S. chromogenes, S. epidermidis, S. pasteuri, S. saprophyticus, S. sciuri, S. simulans, S. warneri, and S. xylosus) inhibited growth of S. aureus in vitro, 23 isolates of which, from S. capitis, S. chromogenes, S. epidermidis, S. pasteuri, S. simulans, and S. xylosus, also inhibited MRSA. One hundred five putative bacteriocin gene clusters encompassing 6 different classes (lanthipeptides, sactipeptides, lasso peptides, class IIa, class IIc, and class IId) in 95 whole genomes from 16 species were identified. A total of 25 novel bacteriocin precursors were described. In conclusion, NAS from bovine mammary glands are a source of potential bacteriocins, with >21% being possible producers, representing potential for future characterization and prospective clinical applications.

IMPORTANCE Mastitis (particularly infections caused by Staphylococcus aureus) costs Canadian dairy producers $400 million/year and is the leading cause of antibiotic use on dairy farms. With increasing antibiotic resistance and regulations regarding use, there is impetus to explore bacteriocins (bacterially produced antimicrobial peptides) for treatment and prevention of bacterial infections. We examined the ability of 441 NAS bacteria from Canadian bovine milk samples to inhibit growth of S. aureus in the laboratory. Overall, 9% inhibited growth of S. aureus and 58% of those also inhibited MRSA. In NAS whole-genome sequences, we identified >21% of NAS as having bacteriocin genes. Our study represents a foundation to further explore NAS bacteriocins for clinical use.

KEYWORDS: Staphylococcus, Staphylococcus aureus, bacteriocins, cattle, coagulase-negative staphylococci, mastitis

INTRODUCTION

Non-aureus staphylococci (NAS), a heterogeneous group of approximately 50 species that can be considered teat skin opportunists and minor pathogens, are the bacteria most commonly isolated from the bovine udder (1–4). Several studies reported that NAS may confer protection against intramammary infection (IMI) by major mastitis pathogens (5, 6). In a challenge study, 53% of Staphylococcus chromogenes-infected quarters were protected from S. aureus challenge (6). In another study, S. chromogenes isolates inhibited in vitro growth of all tested Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus dysgalactiae, and Streptococcus uberis isolates but none of the Gram-negative isolates (5). Similarly, NAS strains from Brazilian bovine mastitis cases, including Staphylococcus epidermidis, Staphylococcus simulans, Staphylococcus saprophyticus, Staphylococcus hominis, and Staphylococcus arlettae, inhibited growth of Corynebacterium fimi (7). The isolated antimicrobial substances were considered to be bacteriocins due to sensitivity to proteolytic enzymes (7). Recently, Braem et al. identified NAS strains (from 6 species) that inhibited S. aureus, S. uberis, and S. dysgalactiae, and an inhibitory substance (from an inhibiting S. chromogenes) was isolated and identified to be a nukacin-like bacteriocin (8).

Bacteriocins are ribosomally synthesized and posttranslationally modified peptides (RiPPs) produced by Gram-positive bacteria that mainly inhibit growth of similar bacterial species or occasionally a broad spectrum of bacteria (9). As regulations surrounding antibiotic usage get stricter, bacteriocins represent potential alternatives to antibiotics (10). Currently, nisin, produced by Lactococcus lactis, is available for use in the dairy industry in the form of Wipe Out, with germicidal activity against S. aureus and S. agalactiae (11). Lacticin 3147, another bacteriocin produced by L. lactis, was tested for use in a teat sealant and reduced the number of S. aureus organisms recovered from the bovine mammary gland 18 h postchallenge compared to infusion with teat sealant alone (12).

Traditionally, identification of novel bacteriocins used culture-based approaches that involved screening numerous isolates for antimicrobial activity, followed by lengthy biochemical characterization. However, due to growing accessibility of genome sequence data, in silico screening (genome mining) is a promising approach to identify novel biosynthetic gene clusters. Although bacteriocin precursor genes are often small and lack homology, making in silico identification challenging, bacteriocin-associated genes present on the same operon are highly conserved. Therefore, the associated modification genes are used in classification schemes, with 2 classes: class I, posttranslationally modified bacteriocins, including lanthipeptides, sactipeptides, and lasso peptides; and class II, nonmodified or cyclic peptides (9). By screening genomes for bacteriocin-associated genes, new lanthipeptides (13, 14) and new class IIa bacteriocin gene clusters (15) have been identified. In addition, BLAST-based approaches have been used to identify bacteriocins in cyanobacteria (16) and to identify lanthipeptide clusters by using a transport gene for screening (17). Current software-based approaches (e.g., BAGEL3 and antiSMASH) combine direct mining for the structural gene with indirect mining for bacteriocin-associated genes. Using this approach, novel bacteriocins were identified in ruminal bacteria (18), anaerobic bacteria (19), lactic acid bacteria (20), and human gut microbiota (21). A large in silico screen apparently has not been done on NAS whole genomes, which could be the foundation for future investigations into alternatives for antimicrobials in the dairy industry.

The first objective was to determine the inhibitory capability of 441 bovine NAS isolates from 26 species against a bovine S. aureus isolate and a human methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) isolate. The second objective was to identify and describe the organization of bacteriocin biosynthetic gene clusters in the corresponding 441 whole-genome sequences.

RESULTS

Phenotypic testing.

Out of 441 NAS isolates, 40 isolates (9.1%) from 9 species (S. capitis, S. chromogenes, S. epidermidis, S. pasteuri, S. saprophyticus, S. sciuri, S. simulans, S. warneri, and S. xylosus) inhibited growth of the bovine clinical mastitis S. aureus isolate (Table 1). Of the 40 inhibiting isolates, 23 (57.5%) from S. capitis, S. chromogenes, S. epidermidis, S. pasteuri, S. simulans, and S. xylosus also inhibited growth of the MRSA isolate.

TABLE 1.

Bacteriocin gene clusters identified in bovine non-aureus staphylococcal genomes and inhibitory phenotypes tested against S. aureus and MRSA

| Species (n) | No. of isolatesa | Group ID |

In vitro inhibition (n) |

No. of bacteriocin gene clusters |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S. aureus | MRSAb | Class I |

Class II |

Total | ||||||||

| Lanthipeptide | Sactipeptide | Lasso peptide | a | b | c | d | ||||||

| S. agnetis (13) | 13 | SAG | − | NT | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| S. arlettae (15) | 15 | SAR | − | NT | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| S. auricularis (2) | 2 | SAU | − | NT | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| S. capitis (22) | 5 | SCAP1 | − | NT | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 5 | SCAP2 | + | + | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| 1 | SCAP3 | − | NT | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | |

| 1 | SCAP4 | + | + | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| 1 | SCAP4 | + | − | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | |

| 7 | SCAP5 | + (7) | + (5) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 2 | SCAP6 | − | NT | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| S. caprae (1) | 1 | SCAR | − | NT | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| S. chromogenes (82) | 2 | SCH1 | + | + | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 1 | SCH2 | + | + | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 79 | SCH3 | − | NT | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| S. cohnii (24) | 2 | SCO1 | − | NT | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 22 | SCO2 | − | NT | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| S. devriesei (8) | 8 | SDE | − | NT | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| S. epidermidis (26) | 2* | SEP1 | + | + | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 24 | SEP2 | − | NT | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| S. equorum (17) | 2 | SEQ1 | − | NT | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 3 | SEQ2 | − | NT | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| 1 | SEQ3 | − | NT | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| 11 | SEQ4 | − | NT | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| S. fleurettii (2) | 2 | SFL1 | − | NT | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| S. gallinarum (21) | 14 | SGA1 | − | NT | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 2 | SGA2 | − | NT | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | |

| 5 | SGA3 | − | NT | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| S. haemolyticus (29) | 1 | SHA1 | − | NT | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 28 | SHA2 | − | NT | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| S. hominis (11) | 11 | SHO | − | NT | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| S. hyicus (3) | 1 | SHY1 | − | NT | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 2 | SHY2 | − | NT | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| S. kloosii (1) | 1 | SKL | − | NT | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| S. nepalensis (2) | 2 | SNE | − | NT | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| S. pasteuri (6) | 1 | SPA1 | + | + | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 5 | SPA2 | − | NT | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| S. saprophyticus (16) | 1 | SSA1 | − | NT | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 1 | SSA2 | + | − | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 14 | SSA2 | − | NT | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| S. sciuri (30) | 3 | SSC1 | − | NT | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 1 | SSC2 | + | − | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| 1 | SSC3 | + | − | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| 1 | SSC4 | + | − | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| 1 | SSC4 | − | NT | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| 6 | SSC5 | + (6) | − | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 17 | SSC6 | − | NT | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| S. simulans (42) | 19 | SSI1 | − | NT | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 1 | SSI2 | − | NT | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | |

| 1* | SSI3 | + | − | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | |

| 1* | SSI4 | + | − | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | |

| 3 | SSI5 | + | + | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | |

| 2 | SSI6 | + | + | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| 1 | SSI7 | + | − | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 14 | SSI8 | − | NT | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| S. succinus (15) | 1 | SSU1 | − | NT | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 14 | SSU2 | − | NT | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| S. vitulinus (6) | 1 | SVI1 | − | NT | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 5 | SVI2 | − | NT | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| S. warneri (19) | 5 | SWA1 | − | NT | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 1 | SWA2 | + | − | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 13 | SWA3 | − | NT | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| S. xylosus (28) | 8 | SXY1 | − | NT | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 1* | SXY2 | + | + | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| 19 | SXY3 | − | NT | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

An asterisk indicates inhibitory activity was achieved with the chloroform-extracted product and inhibition was suppressed with the addition of proteinase K.

NT, not tested.

Effect of proteinase K on inhibition.

Out of 21 inhibitors that were potential producers of bacteriocins, five isolates inhibited growth of S. aureus in the well diffusion assay after chloroform extraction. Inhibition by all 5 isolates was eliminated with the addition of proteinase K.

Screening of genomes for bacteriocin clusters.

In the 441 NAS genomes, 184 putative bacteriocin gene clusters belonging to 143 isolates were identified. A total of 105 clusters from 95 isolates belonging to 16 species were determined to be viable clusters, whereas the others were eliminated due to the absence of either a structural gene or essential bacteriocin-associated genes (Table 1). Overall, 21.5% of NAS potentially produced bacteriocins. Ten of the 441 genomes encoded 2 clusters of different classes/types, whereas the remaining 85 potential producers contained 1 cluster. Of the 40 inhibitors, 21 were putative producers, whereas no viable bacteriocin gene clusters were identified in 19 inhibitors.

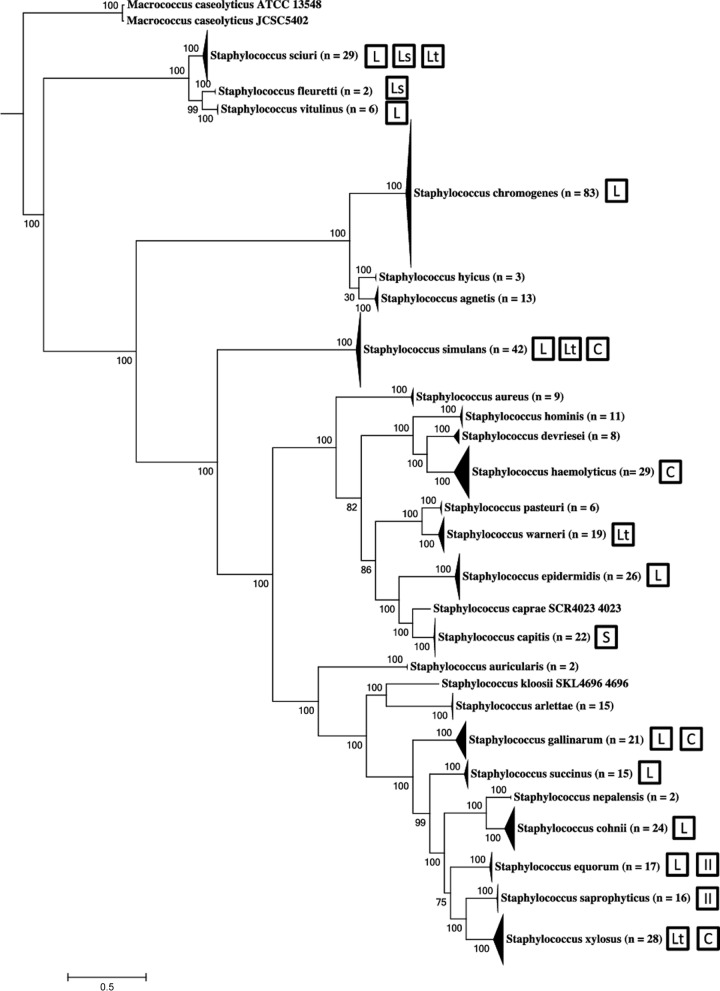

Class II bacteriocins were most frequently identified, with 69 clusters in 68 isolates from S. equorum, S. gallinarum, S. haemolyticus, S. hyicus, S. saprophyticus, S. sciuri, S. simulans, S. succinus, S. warneri, and S. xylosus (Fig. 1). Nine of the class II potential producers were also inhibitors. For class I bacteriocins, lanthipeptides were the most frequently identified type, with 29 clusters in 29 isolates from S. capitis, S. chromogenes, S. cohnii, S. epidermidis, S. equorum, S. gallinarum, S. sciuri, S. simulans, S. succinus, and S. vitulinus (Fig. 1). Fifteen of the 29 potential lanthipeptide producers were also inhibitors. Three sactipeptide clusters were identified from 3 S. capitis isolates, 2 of which were inhibitors. Lastly, 4 lasso peptide clusters were identified in 2 noninhibiting S. fleurettii genomes, a noninhibiting S. sciuri genome, and an inhibiting S. sciuri genome. Putative bacteriocin-associated genes were distributed throughout the phylogeny of NAS (22) (Fig. 1), although no isolates from S. agnetis (n = 13), S. arlettae (n = 15), S. auricularis (n = 2), S. caprae (n = 1), S. devriesei (n = 8), S. hominis (n = 11), S. kloosii (n = 1), S. nepalensis (n = 2), and S. pasteuri (n = 6) contained putative bacteriocin gene clusters. There was no obvious clustering based on phylogeny or class of bacteriocin.

FIG 1.

Distribution of bacteriocin biosynthetic gene clusters in species of non-aureus staphylococci isolated from milk of Canadian dairy cows, displayed on the phylogenetic tree from Naushad et al. (22). Bacteriocin types are indicated by the following abbreviations: L, lanthipeptide; S, sactipeptide; Ls, lasso peptide; II, class II double glycine leader peptides; C, circular bacteriocins; Lt, lactococcin-like.

Class I bacteriocins. (i) Lanthipeptide clusters.

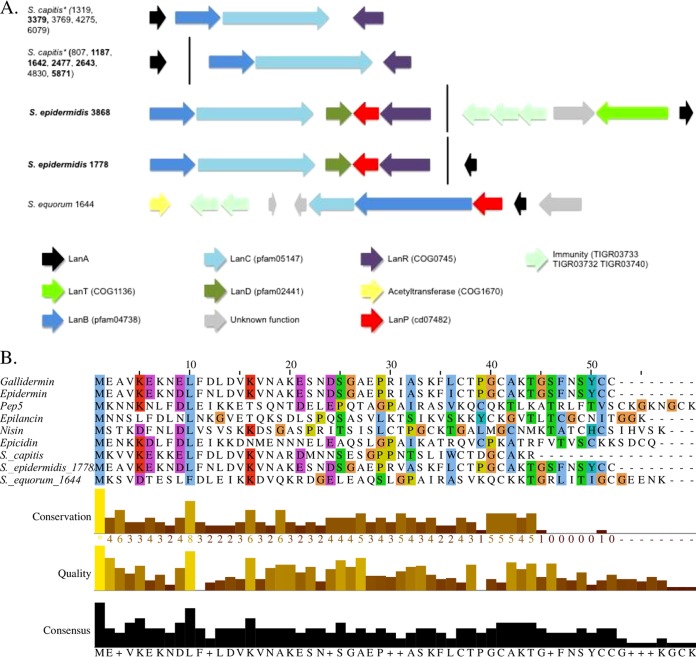

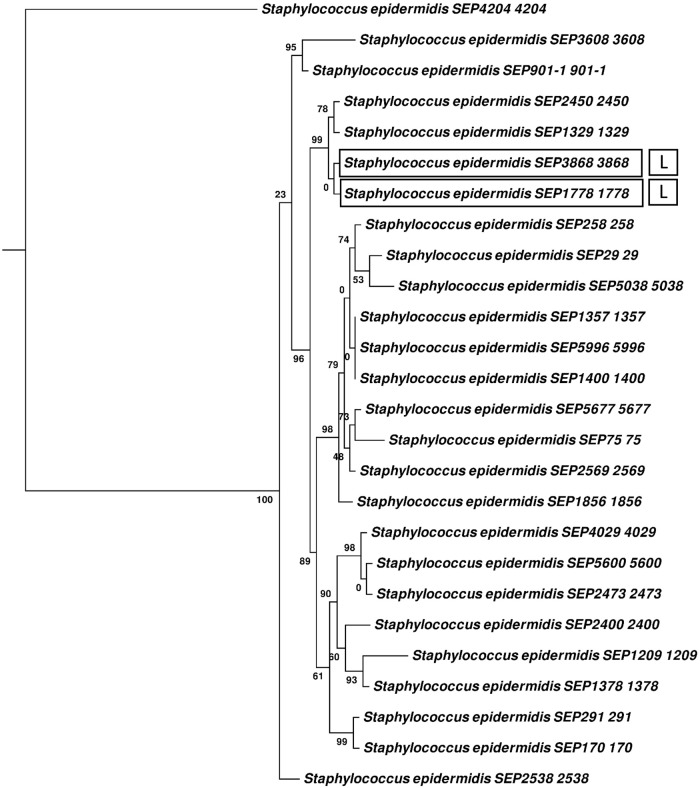

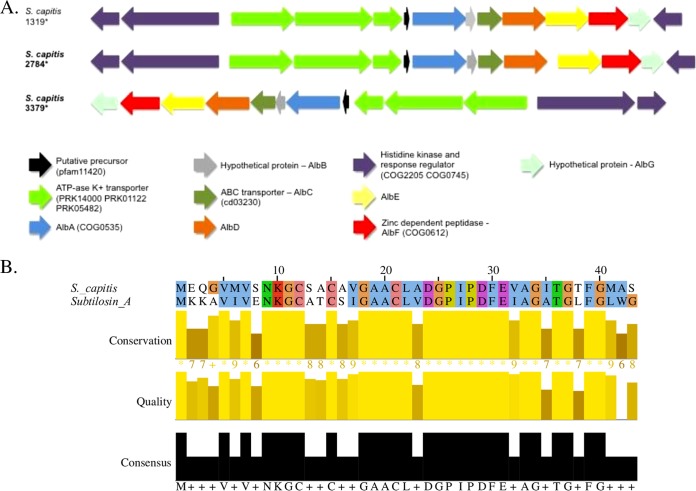

Twenty-nine lanthipeptide gene clusters were detected in NAS genomes (Table 1). Fifteen clusters were classified as type 1 (Fig. 2); 12 of those clusters, all from S. capitis, had identical LanA structural peptides (Fig. 2). Six of the 12 potential S. capitis producers also were inhibitors. The 44-amino-acid (aa) precursor shared 59% identity with nisin (a Lactococcus lactis bacteriocin) and contained the conserved domain pfam02052. Two of the remaining type 1 clusters came from 2 inhibiting isolates of S. epidermidis, containing an identical 52-aa precursor peptide, including the epidermin-conserved domain (TIGR03731), and shared 96% identity with epidermin (GenBank accession number P08136) (Fig. 2). The cluster in S. epidermidis 1778 additionally contained the LanFEG immunity system and a LanT protein (Fig. 2). These 2 isolates were both the only inhibitors and only potential producers identified in S. epidermidis, suggesting that the bacteriocin was responsible for in vitro inhibition (Fig. 3). The final type 1 lanthipeptide cluster identified was detected in noninhibitor S. equorum 1644. This cluster harbored a 57-aa precursor that contained the type 1 lanthipeptide conserved domain pfam08130 and shared 53% identity with Pep5 and 48% identity with epicidin 280 (Fig. 2). This precursor was not identified in any of our other 440 isolates. Four of the 5 clusters contained a LanR regulator, whereas 3 of the 5 contained a LanP protease.

FIG 2.

Biosynthetic gene clusters and LanA alignments of type 1 lanthipeptides identified in non-aureus staphylococci isolated from milk of Canadian dairy cows. (A) Biosynthetic gene clusters of type 1 lanthipeptides, with inhibiting non-aureus staphylococci isolates in boldface and identical precursors in different cluster organizations indicated by an asterisk. (B) Multiple-sequence alignments of LanA genes identified in type 1 lanthipeptide clusters and known bacteriocins nisin (accession number P13068), gallidermin (accession number P21838), epidermin (accession number P08136), epilancin K7 (accession number Q57312), pep5 (accession number P19578), and epicidin 280 (accession number O54220). +, the modal value of that column is shared by more than one residue.

FIG 3.

Phylogenetic tree of Staphylococcus epidermidis isolates from bovine milk indicating growth inhibition against Staphylococcus aureus and genomically identified bacteriocin clusters. The percentage of trees in which the associated isolates clustered together is shown next to the branches, with branch lengths measured in numbers of substitutions per site. Phenotypically inhibiting isolates are surrounded with a box. L, lanthipeptide bacteriocin gene cluster.

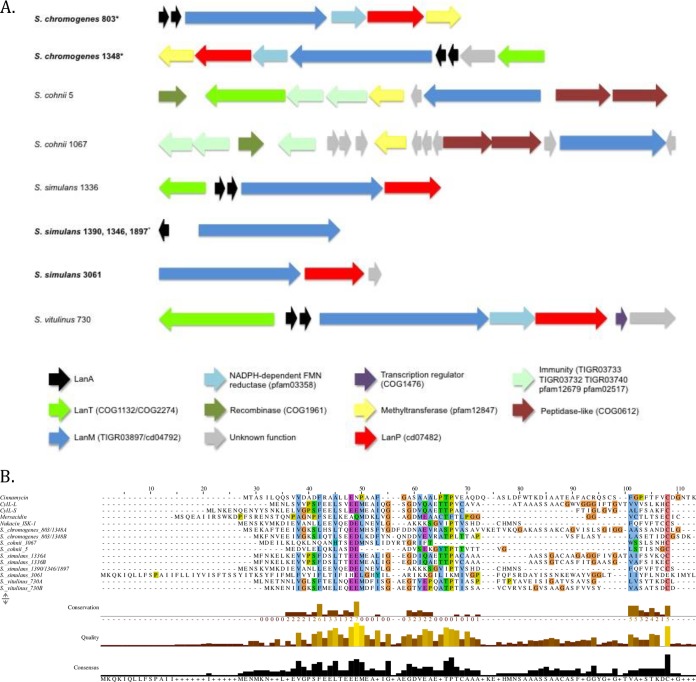

Fourteen of the 29 lanthipeptide clusters contained the type 2 LanM modification system. Ten of those clusters contained single LanM proteins (Fig. 4). Of those 10 clusters, 2 inhibitors from S. chromogenes contained 61-aa LanA1 and 82-aa A2 precursors, which contained the mersacidin conserved domain (pfam16934); the A1 precursor shared 20% identity with the Cyl-L component of cytolysin produced by Enterococcus faecalis, and the A2 precursor shared 26% identity with the Cyl-S component of cytolysin (Fig. 4), whereas A1 and A2 shared 40% identity with each other (Fig. 4). The S. chromogenes 1348 cluster additionally contained a LanT transporter (Fig. 4). Staphylococcus cohnii 5 contained a cluster with a 39-aa hypothetical protein that shared 19% identity with LanA from mersacidin, although no bacteriocin-associated conserved domains were identified during BLASTp analysis. Staphylococcus cohnii 1067 also had no identified structural peptide, although a 41-aa hypothetical protein adjacent to LanM shared 21% identity with the S. cohnii 5 potential LanA and 25% with LanA from S. simulans 1336 identified in this study. Staphylococcus simulans 1336, a noninhibitor, contained a 2-component lanthipeptide, where the 68-aa A1 shared 56% identity with the Cyl-L component of cytolysin and the 68-aa A2 shared 57% identity with Cyl-L. Furthermore, A1 and A2 have 80% identity with one another and contained the 2-component Enterococcus faecalis cytolysin (EFC) conserved domain (pfam16934). The next 3 lanthipeptide clusters were from 3 inhibiting S. simulans isolates, and all contained identical clusters with LanA peptides (conserved domain pfam04604) that were identical to NukA, the structural peptide for nukacin ISK-1 (GenBank accession number Q9KWM4). Another cluster, in S. simulans 3061, contained a 105-aa hypothetical protein which may function as a LanA (Fig. 4) and shared 15% identity with a potential LanA in S. cohnii 5. Lastly, S. vitulinus 730 contained 2 LanA peptides, which shared 53% identity with each other. Furthermore, A1 shared 35% identity with Cyl-L and A2 shared 32% identity with both Cyl-S and mersacidin. Three clusters contained an NADPH-dependent flavin mononucleotide (FMN) reductase (not normally associated with lanthipeptide clusters).

FIG 4.

Biosynthetic gene clusters and LanA alignments of type 2 lanthipeptides with a single LanM identified in non-aureus staphylococci isolated from milk of Canadian dairy cows. (A) Biosynthetic gene clusters of type 2 lanthipeptides, with inhibiting NAS isolates in boldface and identical precursors in various cluster organizations within the same species indicated by an asterisk. (B) Multiple-sequence alignments of LanA genes identified in type 2 lanthipeptide clusters and known bacteriocins cinnamycin (accession number P29827), cytolysin-L (accession number H7C7B0), cytolysin-S (accession number H7C7B5), mersacidin (accession number P43683), and nukacin ISK-1 (accession number Q9KWM4).

The remaining 4 lanthipeptide clusters were part of a different category of type 2 lanthipeptides that contain 2 structural peptides, plus dual LanM proteins, where each LanM protein is responsible for modifying a distinct precursor peptide (Fig. 5). Staphylococcus succinus 6028 contained a 73-aa A1 precursor and a 68-aa A2 precursor. Staphylococcus succinus 6028A1 shared 34% identity with lacticin 3147A1, whereas the A2 precursor shared 32% identity with lacticin 3147A2. In inhibitor S. sciuri 225, the 63-aa A1 precursor shared 28% identity with lacticin 3147A1, and the 68-aa A2 precursor shared 36% identity with lacticin 3147A2 and 40% identity with lichenicidin A2. Lastly, S. gallinarum 2094 and 1388 contained identical novel two-peptide type 2 lanthipeptide biosynthetic clusters with 83-aa A1 precursors (conserved domain pfam14867) that shared 34% identity with lichenicidin A1 and 68-aa A2 precursors that shared 43% identity with lichenicidin A2. The 2 precursors, A1 and A2, shared 21.9% identity with each other. Three of the 4 clusters contained a LanP protease.

FIG 5.

Biosynthetic gene clusters and LanA alignments of type 2 lanthipeptides with dual LanM enzymes identified in non-aureus staphylococci isolated from milk of Canadian dairy cows. (A) Biosynthetic gene clusters of identified dual precursor type 2 lanthipeptides, with inhibiting NAS isolates in boldface. (B-1) Multiple-sequence alignments of LanA1 genes identified in type 2 lanthipeptide clusters and known bacteriocins lacticin 3147 A1 (accession number O87236), lichenicidin A1 (accession number P86475), and staphylococcin C55 A1 (accession number Q9S4D3). (B-2) Multiple-sequence alignments of LanA2 genes identified in type 2 lanthipeptide clusters and known bacteriocins lacticin 3147 A2 (accession number O87237), lichenicidin A2 (accession number P86476), and staphylococcin C55 A2 (accession number Q9S4D2).

(ii) Sactipeptide clusters.

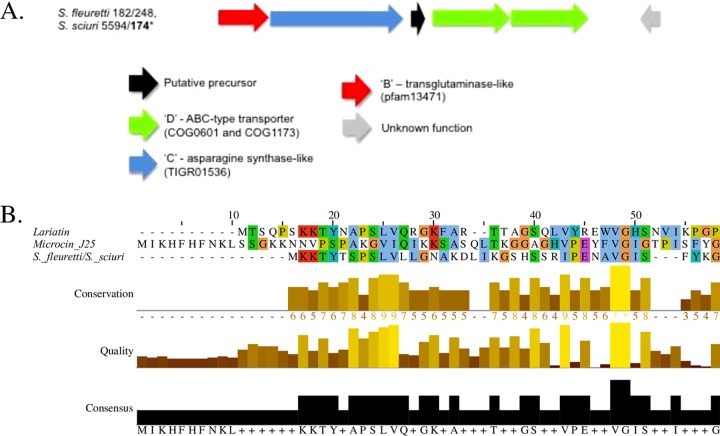

A total of 26 potential subtilosin A-like clusters were identified, although 23 were excluded due to the absence of the critical AlbF gene (18), leaving 3 S. capitis isolates that contained viable clusters (Table 1). In S. capitis 1319 (noninhibitor), 2487 (inhibitor), and 3379 (inhibitor), the structural peptides all were identical and shared 63% identity with the subtilosin A precursor, SboA (accession number O07623) (Fig. 6).

FIG 6.

Biosynthetic gene clusters and alignments of precursor peptides from sactipeptides identified in non-aureus staphylococci isolated from milk of Canadian dairy cows. (A) Biosynthetic gene clusters of identified sactipeptides, with inhibiting non-aureus staphylococcal isolates indicated using boldface and identical precursors indicated by an asterisk. (B) Sequence alignment of the identified sactipeptide precursor and known sactipeptide subtilosin A (accession number O07623).

(iii) Lasso peptide clusters.

Three noninhibiting NAS isolates, 2 S. fleurettii isolates and 1 S. sciuri isolate, along with an inhibiting S. sciuri isolate, contained identical clusters encoding a lasso peptide (Fig. 7). The 40-aa structural peptide, termed A, shared no identified conserved domains but shared 31% identity with a previously characterized lasso peptide, lariatin, produced by Rhodococcus sp. strain K01-B0171 (23).

FIG 7.

Biosynthetic gene clusters and alignments of precursor peptides from the lasso peptide identified in non-aureus staphylococci isolated from milk of Canadian dairy cows. (A) Biosynthetic gene cluster of the identified lasso peptide. (B) Sequence alignments of the identified lasso peptide precursor and known lasso peptides lariatin (UniProtKB accession number H7C8I3) and microcin J25 (accession number Q9X2V7).

Class II bacteriocins. (i) Double-glycine leader.

Three S. equorum isolates and 1 S. saprophyticus isolate (all noninhibitors) encoded bacteriocin clusters that contained 2 precursor peptides that were annotated as bacteriocin class II with double-glycine leader peptides (Fig. 8). Although the precursor peptides in all 4 clusters were identical, additional associated proteins varied. The S. saprophyticus isolate and 2 of the S. sciuri clusters contained a SecA protein, possibly related to secretion.

FIG 8.

Biosynthetic gene clusters of class II double glycine leader peptide bacteriocins identified in non-aureus staphylococci isolated from milk of Canadian dairy cows. Identical precursors are identified by an asterisk.

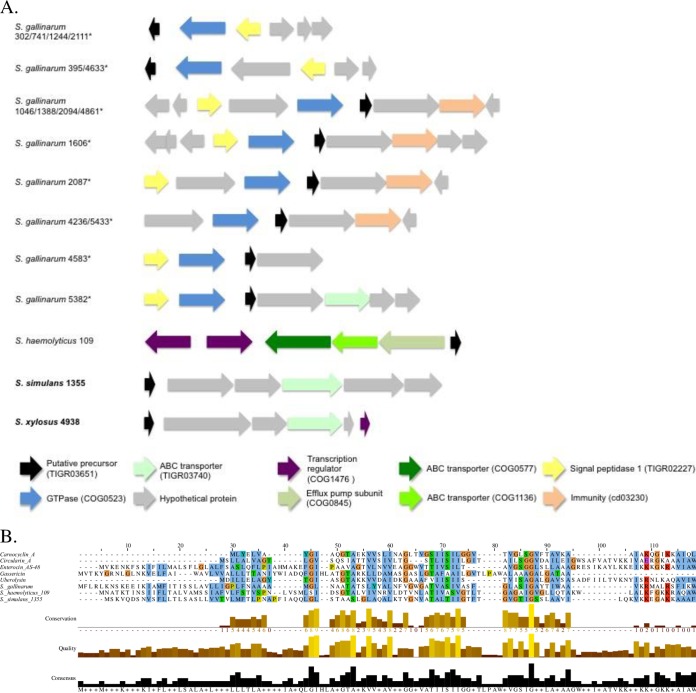

(ii) Class IIc circular bacteriocin clusters.

Nineteen isolates, 2 of which were inhibitors (across various clades of NAS phylogeny; Fig. 1), contained circular bacteriocin gene clusters encoding 4 distinct bacteriocins (Fig. 9). Of the 19 identified clusters, 16 were in S. gallinarum isolates and all 16 precursors were identical, although the clusters contained various bacteriocin-associated genes (Fig. 9). The S. gallinarum precursor shared 25% identity with both gassericin and enterocin AS-48 (Fig. 9). All but 2 of the clusters contained a signal peptidase. Staphylococcus haemolyticus 109 contained a 97-aa structural peptide sharing 25% identity with both circularin and enterocin AS-48. The cluster identified in inhibiting S. simulans 1355 contained a structural peptide (conserved domain TIGR03651) with 23% identity with enterocin AS-48. The final cluster, identified in inhibiting S. xylosus 4938, contained a precursor with 32% identity with circularin A.

FIG 9.

Biosynthetic gene clusters and precursor alignments of class IIc circular bacteriocins identified in non-aureus staphylococci isolated from milk of Canadian dairy cows. (A) Biosynthetic gene clusters of identified class IIc bacteriocins, with inhibiting NAS isolates indicated in boldface and identical precursors in S. gallinarum indicated by asterisks. (B) Alignment of precursor peptides from identified class IIc bacteriocins and known bacteriocins carnocyclin A (accession number B2MVM5), circularin A (accession number Q5L226 [Bactibase accession number BAC164]), enterocin AS-48 (accession number Q47765), gassericin (accession number O24790), and uberolysin (accession number A5H1G9).

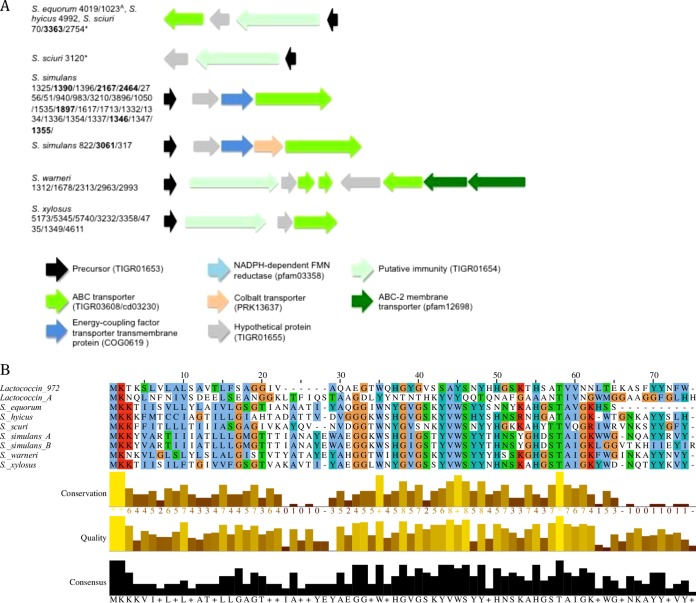

(iii) Class IId clusters.

Forty-seven NAS genomes contained complete lactococcin-like clusters (Fig. 10). Of these 47 potential producers, 8 were inhibitors. Twenty-seven lactococcin-like clusters were identified in 27 S. simulans isolates. Eleven isolates contained a 94-aa structural precursor, whereas the remaining 15 contained a 105-aa structural precursor, with 88% identity with each other (Fig. 10).

FIG 10.

Biosynthetic gene clusters and precursor alignments of class IId lactococcin-like bacteriocins identified in non-aureus staphylococci isolated from milk of Canadian dairy cows. (A) Biosynthetic gene clusters of identified class IId bacteriocins, with inhibiting NAS isolates indicated in boldface, identical precursors in S. equorum indicated by a superscript letter A, and identical precursors in S. sciuri indicated by asterisks. (B) Alignments of precursor peptides from identified class II bacteriocins and known bacteriocins lactococcin 972 (accession number O86283) and lactococcin A (accession number P0A313).

Fourteen isolates contained clusters with the same organization of genes, although the precursor gene (conserved domain pfam09683) varied slightly among isolates (Fig. 10). All 8 S. xylosus isolates in this group contained identical 93-aa structural genes with 62% identity with the structural gene identified in the 2 S. equorum clusters. The S. hyicus cluster's structural peptide shared 52% identity with the S. xylosus cluster's structural peptide. Lastly, 3 S. sciuri isolate structural peptides shared 43% identity with the S. xylosus precursor.

An additional S. sciuri isolate with a structural peptide identical to that of the other S. sciuri isolates mentioned above was identified, although it lacked the ABC transporter in the cluster. The remaining 5 clusters were identified in S. warneri. The 95-aa putative precursor shared 60% identity with the 94-aa precursor from S. simulans (Fig. 10).

DISCUSSION

In this study, 95 isolates (22%) of 441 NAS encoded 105 bacteriocin biosynthetic gene clusters, making them potential bacteriocin producers. Bacteriocin gene clusters were detected in S. capitis, S. chromogenes, S. cohnii, S. epidermidis, S. equorum, S. fleurettii, S. gallinarum, S. haemolyticus, S. hyicus, S. saprophyticus, S. sciuri, S. simulans, S. succinus, S. vitulinus, S. warneri, and S. xylosus. According to the phylogenetic tree, bacteriocin gene clusters are spread throughout the NAS phylogeny, although lasso peptides were only present in 2 species from the same clade and sactipeptides were only identified in S. capitis. In contrast, only 40 (9%) of 441 NAS were inhibitors when antimicrobial activity was tested in vitro against a bovine clinical mastitis S. aureus isolate. We identified a higher percentage of NAS with antimicrobial activity than a previous study that reported only 6.4% of NAS from bovine mastitis cases were inhibitory (7). The NAS isolated from the teat apex skin of dairy cows may have potential for greater bacteriocin production, as 13% of those isolates had antimicrobial properties in one study (8).

Our study identified 29 lanthipeptide clusters from 29 NAS isolates. Both type 1 and 2 lanthipeptides were identified in NAS genomes. Lanthipeptides are characterized by the presence of several uncommon amino acids, including meso-lanthionine and 3-methyl-lanthionine, the result of posttranslational modifications (24). For type 1 lanthipeptides, dehydration of the serine and threonine residues to dehydroalanine (Dha) and dehydrobutyrine (Dhb) residues in the prepeptide, LanA, is completed by a dehydratase (LanB). Thereafter, thioether cross-links are formed on the dehydrated amino acids by a cyclase (generically termed LanC), whereas each specific bacteriocin has its individual naming system, for example, nisB and nisC for nisin. More than 50 lanthipeptides from Gram-positive bacteria have been isolated and described (25), with genome mining identifying many more potential compounds (26). Previously uncommon genes, e.g., those encoding FMN reductase and N-acetyltransferases, were identified in some clusters in our study, which have been reported in multiple lanthipeptide clusters identified by M. Singh and D. Sareen (17). As we learn more about posttranslational modifications, these genes could help identify novel clusters in additional genomes. Type 1 lanthipeptides were identified in S. capitis, S. epidermidis, and S. equorum. The S. epidermidis strains harboring the bacteriocin biosynthetic gene cluster also inhibited S. aureus. The structural gene had 96% similarity to the gene encoding epidermin, the lanthipeptide most frequently produced by NAS (27) and reported to inhibit human MRSA (28) and S. aureus isolated from bovine mastitis (29). Only 6 of 12 S. capitis potential lanthipeptide producers were inhibitors; therefore, if it is in fact the bacteriocin identified that is responsible for the inhibition, perhaps the bacteriocin cluster is not being expressed in the 6 noninhibitors. The S. equorum potential producer was also a noninhibitor but harbors a gene that likely encodes a novel bacteriocin (similar to pep5 and epidicin 280). Type 1 lanthipeptide prepeptides typically have an FNLD conserved region at approximately positions −15 to −20 and a proline at −2 from the cleavage site and have roles in modifications of the peptide (30). Only the LanA identified in the S. epidermidis strains had the FNLD conserved region and the proline at −2. The LanA identified in S. capitis had an FDLD motif with the proline at −2, similar to gallidermin and lanthipeptides recently identified in ruminal bacteria (18). However, the S. equorum LanA had an FDLE motif, similar to pep5 and epicidin 280, which had the closest identity when aligned.

One of the most common lanthipeptides identified in NAS to date has been nukacin-like bacteriocin. In our study, nukacin was discovered in 3 inhibiting S. simulans isolates. The LanA precursor was identical to nukacin ISK-1 produced by S. warneri (31), nukacin 3299 produced by S. simulans (32), and nukacin L217 produced by S. chromogenes (8). The findings that both nukacin 3299 and nukacin L217 producer strains were also isolated from bovine milk and the potential nukacin producer in our study was able to inhibit S. aureus suggest a role for this bacteriocin in NAS colonization and pathogen inhibition in the udder environment.

Type 2 lanthipeptides are characterized by a bifunctional enzyme, LanM, responsible for both dehydration and cyclization, whereas the C terminus shares homology with LanC cyclases of the type 1 lanthipeptides (25). Ten of 14 clusters identified contained a single LanM, with 4 containing 2 LanA precursors. The 2 LanA precursors in each cluster had a high sequence identity (80% for the S. simulans 1336 cluster), suggesting that the same single LanM enzyme could modify both precursors. For dual precursors with low sequence identity (e.g., in lichenicidin and haloduracin), there are multiple LanM enzymes to modify each unique precursor (33, 34). These represent a distinct group of type 2 lanthipeptides, of which 3 were identified in our study. Here, A1 and A2 precursors shared 26, 35, and 22% identity with one another for clusters in S. succinus, S. sciuri, and S. gallinarum, respectively. However, only the S. sciuri isolate was an inhibitor. Unlike type 2 lanthipeptides produced by ruminal bacteria (18), eight type 2 clusters in this study harbored the LanP protease.

Sactipeptides are a group of class I bacteriocins that contain a sulfur-to-α-carbon linkage, catalyzed by a recombinant S-adenosylmethionine (rSAM) protein (35, 36). They were originally only isolated from Bacillus species, although genome mining has now identified putative gene clusters in the genera Clostridium, Blautia, Kandleria, Lachnobacterium, Peptostreptococcus, Roseburia, and Ruminococcus (18, 21, 37). One sactipeptide cluster was identified in 3 isolates in our study, although the bacteriocin-associated genes varied slightly between clusters. Our analysis identified a histidine kinase (HK) and response regulator (RR) in each cluster, indicating that bacteriocins are subjected to a 2-component regulatory system, previously only reported in sactipeptide clusters from ruminal bacteria (18). Two of the 3 cluster-containing isolates were also inhibitors, although the S. capitis 3379 isolate additionally contained a lanthipeptide that could be responsible for inhibition. The inhibiting S. capitis 2784 did not contain any additional clusters to our knowledge, although subtilosin A, which this novel bacteriocin is most related to, moderately inhibited S. aureus in vitro (38). Thus, the noninhibiting S. capitis potential producer may not have been expressing its bacteriocin gene, or the inhibition by the other two isolates was due to another product.

Lasso peptides are an emerging group of RiPPs that do not undergo extensive modification, although they are folded so that the C terminus is threaded through a ring formed by a single isopeptide bond, yielding their signature lariat-like form (39). To the best of our knowledge, no lasso peptides have been identified in Staphylococcus species (40). In this study, an identical, novel cluster was identified in 3 noninhibiting isolates, 2 from S. fleurettii and 1 from S. sciuri, along with 1 inhibiting S. sciuri. The identified clusters contained all 4 of the essential enzymes (ABCD) for peptide production (19), a transglutaminase-like protein that is likely encoded by the B gene and acts as a protease to cleave the leader sequence, a protein with an asparagine synthase conserved domain, which is likely encoded by the C gene responsible for isopeptide bond formation, and 2 units of an ABC-type dipeptide/oligopeptide/nickel transport system functioning as the D gene product, as well as a 53-aa putative protein.

Although most identified putative bacteriocin clusters in this study were class II, there are only 12 unique precursors in those clusters, compared to the 15 unique lanthipeptide precursors identified. To date, the majority of class II bacteriocins in Staphylococcus species have been identified in S. aureus (27). The first circular bacteriocin in Staphylococcus species, discovered in 2014, was aureocyclicin 4185 from S. aureus 4185 (41). Here, we identified putative novel circular bacteriocin gene clusters from S. gallinarum, S. haemolyticus, S. simulans, and S. xylosus. These bacteriocin precursors had limited similarity to previously characterized circular bacteriocins, but all contained the conserved domain associated with the circularin A/uberolysin family. Although the S. xylosus potential producer was not the only producer in the species (lactococcin-like clusters were also identified in other isolates), it was the only inhibitor in the species, suggesting that this bacteriocin is responsible for activity against S. aureus, although further investigation after isolation and purification of the peptide is needed. The S. simulans isolate was also an inhibitor in vitro, but potential producers from S. gallinarum and S. haemolyticus were noninhibitors, suggesting these bacteriocins either have a different spectrum of activity or were not activated.

Class IId bacteriocins are described as linear non-pediocin-like. Lactococcin 972 belongs to this group and is produced by Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis IPLA 972 (42). The gene cluster, along with the LclA precursor, encodes a transporter, LclB, and an immunity gene product (19). The 7 class IId lactococcin-like precursors all had various degrees of similarity with one another, but all contained the lactococcin 972 conserved domain. Generally, lactococcin-like bacteriocins have a narrow spectrum of activity against Lactococcus species due to the nature of their binding to receptors (43), indicating it was unlikely that these potential producers would be inhibitory against S. aureus. Nonetheless, 8 of 47 lactococcin-like potential producers were inhibitors. Of these 8 inhibitors, 4 also contained a lanthipeptide cluster, whereas 1 also contained a circular bacteriocin cluster, which could have been the bacteriocins responsible for S. aureus inhibition. Remaining inhibitors could harbor an unidentified novel bacteriocin responsible for inhibition or could be producing a nonbacteriocin inhibitory substance. All of these novel bacteriocins will need further assessments for spectrum of activity and biochemical characterization to complete identification.

When comparing phenotype and genotype, 95 NAS contained bacteriocin biosynthetic gene clusters, whereas only 40 of the NAS had inhibition toward S. aureus. This could be due to several factors, including that bacteriocins produced were not effective against inhibiting S. aureus or the condition tested in vitro did not lead to sufficient levels of bacteriocin production (44). This highlights a substantial benefit of genome mining, as variability of in vitro inhibition testing is negated, enabling clusters that may be silent or repressed in vitro to be identified. Of the 40 inhibitors, 21 were identified as potential producers, and the peptide nature of the inhibitory product was confirmed in five of these isolates by elimination of the inhibition with the addition of proteinase K. Further investigation into the remaining isolates should be carried out to optimize the extraction conditions to obtain inhibition in the well diffusion assay and to confirm the proteinaceous nature of the inhibitory compound. Bacteriocin gene clusters were not detected for the remaining 19 inhibiting isolates, perhaps due to inhibition from production of other inhibiting substances, e.g., low-molecular-weight antibiotics, lytic enzymes, or metabolic by-products (45). It could also be due to the nature of the detection software, as identification of clusters using antiSMASH is based on similarity to previously described genes, with potential to miss completely novel clusters. However, as knowledge increases regarding bacteriocin-associated genes and structural precursors, detection methods will improve and more bacteriocins will be described, allowing for even greater detection. In order to conduct the most comprehensive analysis of bacteriocins currently available, our analysis methods were ordered and combined to maximize detection. By first using antiSMASH and BLAST searches using the BAGEL databases, we identified the bulk of the genomes containing bacteriocin gene clusters. We then used any precursor genes in clusters identified by antiSMASH for further BLAST searches in our whole genomes, which led to identification of additional lasso peptide clusters not detected by antiSMASH. Lastly, using our phenotypic results, comparing genomes of inhibitors to closely related noninhibitors in the same species, and using BLAST searches to analyze unique sequences in the inhibitor led to identification of bacteriocin-associated genes in 6 of 19 inhibitors not initially identified as producers. However, no complete clusters were identified in these isolates due to the absence of peptide precursor genes in close proximity upon visualization in Geneious.

In conclusion, all clusters identified, excluding the nukacin identified in S. simulans and the epidermin variant identified in S. epidermidis, were novel bacteriocin clusters, having less than 70% identity with previously described bacteriocins. The combination of genome mining tools, such as antiSMASH along with BLAST searches, makes discovery of novel bacteriocins quicker and more comprehensive than conventional approaches. The identified putative producers should be further studied to characterize the bacteriocins described here in order to elucidate structures, modes of action, and spectrum of activity. The NAS isolated from mammary origin are a rich source of bacteriocins, with >21% being potential producers, thereby representing a promising source for future research and potential clinical applications.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Isolates.

NAS isolates and an S. aureus isolate from a clinical case of bovine mastitis were collected by the National Cohort of Dairy Farms (NCDF), conducted across Canada during 2007 and 2008, as described by Reyher et al. (46). The Canadian Bovine Mastitis and Milk Quality Research Network (CBMQRN) at the University of Montreal stored the samples before sending them to the University of Calgary. Overall, 441 NAS isolates were selected from the stock of 5,507 isolates of the 25 NAS species identified previously (22, 47). These isolates originated from 87 herds across Canada from Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island, New Brunswick (representing Atlantic Canada), Québec and Ontario (representing Central Canada), and Alberta (representing Western Canada) (46). Isolates included 68 NAS isolates from clinical mastitis cases, 26 multidrug-resistant (MDR) isolates, a maximum of 1 isolate per cow of any uncommon species (defined as <20 unique isolates at cow level), and a maximum of 1 randomly selected isolate per cow for all other species until 441 were chosen (22). The multidrug-resistant MRSA clinical strain H176 was obtained from K. Zhang's laboratory at the University of Calgary.

Phenotypic testing.

All 441 NAS isolates were tested for antimicrobial activity against an S. aureus isolate (derived from clinical mastitis). Only the NAS isolates that inhibited this S. aureus strain were tested against the MRSA strain. Testing was done using a cross-streaking method, modified from a previous report (5). Each isolate was plated on 5% defibrinated sheep blood agar plates (BD Diagnostics, Mississauga, ON, Canada) and incubated overnight at 37°C. A single colony was diluted in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) to a McFarland 0.5 standard and was used to inoculate a center streak (5 mm) on a 5% sheep blood agar plate and subsequently incubated at 37°C for 24 h. On day 2, the agar was loosened from the plate with sterile metal tweezers and flipped onto the lid of the plate so the NAS center streak was face down. A 100-μl volume of a 10−3 dilution in PBS of a McFarland 0.5 standard of a single colony from an overnight culture on 5% sheep blood agar of S. aureus then was spread over the entire agar surface and incubated at 37°C for 24 h. On day 3, plates were examined for bacterial growth, and any inhibition (total or partial) of pathogen growth was recorded. All experiments included a negative control (PBS was used to make the center streak on day 1).

Effect of proteinase K on inhibition.

Strains that were both inhibitors of S. aureus and potential bacteriocin producers were tested to confirm the peptide nature of the inhibitory product using proteinase K (20 mg ml−1; Sigma-Aldrich) and an agar well diffusion assay (48). Concentrated cell-free supernatant was obtained from brain heart infusion (BHI) cultures of the 21 inhibiting and potentially producing NAS isolates by performing a modified version of chloroform extraction as described previously (49). Briefly, 40 ml of BHI broth was inoculated with 0.1% of an overnight culture of NAS and incubated at 37°C for approximately 20 h. Cells were removed by centrifugation at 4,500 × g at 4°C for 15 min. Twenty milliliters of chloroform (Sigma-Aldrich) was mixed with the cell-free supernatant of each NAS and stirred vigorously for 20 min, followed by centrifugation at 4,500 × g at 4°C for 15 min. The cloudy interfacial precipitate was collected and dried overnight. The dried product was dissolved in 1 ml PBS using a magnetic spinner at 4°C for 24 h. Proteinase K was added to a sample of each concentrated cell-free supernatant, and samples with and without proteinase K were incubated at 37°C for 1 h. Residual inhibition was tested using an agar well diffusion assay (48) using the same bovine S. aureus isolate as used in the cross-streaking test.

Whole-genome sequencing, assembly, and annotation.

Sequencing, assembly, and annotation for NAS and the clinical mastitis S. aureus isolate were performed as described previously (22). Briefly, genomic DNA was extracted with a DNeasy blood and tissue kit (Qiagen, Toronto, ON, Canada) according to the corresponding protocol for Gram-positive bacteria. Sequencing of these samples was performed using the Illumina MiSeq platform (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA); DNA libraries for sequencing were prepared using a Nextera XT DNA library preparation kit (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). All sequencing steps, including cluster generation, paired-end sequencing (2 by 250 bp), and primary data analysis for quality control, were performed on the instrument. Genome assembly was automated using the Snakemake workflow engine (50). Raw read pairs were screened for adapters and quality trimmed using Cutadapt 1.8.3 (51) as implemented in Trim Galore! 0.4.0 (with default parameters). Genomes were assembled using Spades 3.6.0 (52) using the built-in error correction and default parameters. To assess coverage, reads were mapped back to the assembled genome using BWA 0.7.12-r1039 (53). Contigs of >200 bp were annotated with Prokka 1.11 (54) using the provided Staphylococcus database. Assembly quality was evaluated with Quast 3.0 (55). Contigs, as well as the annotated protein sequences, were used for custom BLAST searches using SequenceServer (56).

Screening of genomes for bacteriocin clusters.

Identification of biosynthetic gene clusters related to secondary metabolite production and analysis of sequences of interest was done using antiSMASH 3 (57). Each gene in identified clusters was further examined using the BLASTP web server on NCBI (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST), and the presence of conserved domains from the Conserved Domain Database (58) was noted in each coding region and compared to previously identified known conserved domains in bacteriocin-associated genes (18). Putative gene clusters were classified according to Cotter et al. (10). Additionally, any identified structural genes in the NAS genomes were used for further BLAST searches against our NAS genomes to potentially identify any clusters not detected by antiSMASH.

BLAST.

The 441 NAS whole genomes were assessed by BLAST for any bacteriocin structural genes contained in class I, II, and III databases from BAGEL (http://bagel.molgenrug.nl/index.php/bacteriocin-database). Any genomic regions with identified bacteriocin-associated genes after the BLAST search were visualized using Geneious version 8.1.6 (59) to determine if the bacteriocin gene cluster was complete by assessing if the structural gene and known essential associated genes were present using the BLASTP web server on NCBI (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST).

Genome comparison.

To further identify potential bacteriocin-associated genes, genomes of the inhibiting NAS were compared to closely related genomes of noninhibiting NAS of the same species according to the phylogenetic trees of each species. For this purpose, the phylogenetic trees for each species of NAS were constructed using methods described previously (22). Briefly, trees were rooted using Macrococcus caseolyticus and created based on the core genome of the individual NAS species. The core set was identified using the UCLUST algorithm (60), and protein families with at least 30% sequence identity and 50% sequence length were considered core. However, protein families present in ≥95% of the input genomes were considered core, and protein families containing potential paralogous sequences (duplicated sequence in the same genome) were excluded. Each protein family was individually aligned using MAFFT 7 (61). Aligned amino acid positions which contained gaps in more than 50% of genomes were excluded from further analysis. Remaining amino acid positions were concatenated to create a combined data set. A maximum-likelihood tree based on this alignment was constructed using FastTree 2.1 (62) using the Whelan and Goldman substitution model (63).

Comparisons were done by identifying shared genes, present in both closely related inhibiting and noninhibiting isolates, using Spine, a Web-based application that identifies common sequences in the input genomes (64). Sequences unique to inhibiting isolates were then determined using AGEnt by subtracting the output of shared sequences acquired from Spine from the genome of an inhibiting isolate (64). Sequences unique to inhibiting isolates were then visualized using Geneious version 8.1.6 (59), and genes and conserved domains were determined using the BLASTn web server on NCBI (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST) and Conserved Domain Database (58) to establish any additional bacteriocin-associated sequences.

Precursor gene alignments.

Protein alignments of precursor peptides were generated using MUSCLE (65). Sequence alignments were viewed and edited with Jalview alignment editor (66).

Accession number(s).

Data were previously submitted to NCBI under BioProject number PRJNA342349.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank all dairy producers, animal health technicians, and Canadian Bovine Mastitis and Milk Quality Research Network (CBMQRN) regional coordinators (Trevor De Vries, University of Guelph, Canada; Jean-Philippe Roy and Luc Des Côteaux, University of Montreal, Canada; Kristen Reyher, University of Prince Edward Island, Canada; and Herman Barkema, University of Calgary, Canada) who participated in data collection. The bacterial isolates were provided by the CBMQRN. We also thank Matthew Workentine for his assistance with bioinformatics and Aaron Lucko for his work in the laboratory. Finally, we thank John Kastelic for editing the manuscript.

This work was partially funded through the NSERC Industrial Research Chair in Infectious Diseases of Dairy Cattle. This project was also part of the Canadian Bovine Mastitis and Milk Quality Research Network (CBMQRN) program, funded by Dairy Farmers of Canada and Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada through the Dairy Research Cluster 2 Program. The CBMQRN pathogen and data collections were financed by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (Ottawa, ON, Canada), Alberta Milk (Edmonton, AB, Canada), Dairy Farmers of New Brunswick (Sussex, New Brunswick, Canada), Dairy Farmers of Nova Scotia (Lower Truro, NS, Canada), Dairy Farmers of Ontario (Mississauga, ON, Canada), Dairy Farmers of Prince Edward Island (Charlottetown, PE, Canada), Novalait, Inc. (Quebec City, QC, Canada), Dairy Farmers of Canada (Ottawa, ON, Canada), Canadian Dairy Network (Guelph, ON, Canada), Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (Ottawa, ON, Canada), Public Health Agency of Canada (Ottawa, ON, Canada), Technology PEI, Inc. (Charlottetown, PE, Canada), Université de Montréal (Montréal, QC, Canada), and University of Prince Edward Island (Charlottetown, PE, Canada) through the CBMQRN (Saint-Hyacinthe, QC, Canada). D.A.C. and S.N. were supported by an NSERC-CREATE in milk quality scholarship.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.01015-17.

REFERENCES

- 1.Piepers S, De Meulemeester L, de Kruif A, Opsomer G, Barkema HW, De Vliegher S. 2007. Prevalence and distribution of mastitis pathogens in subclinically infected dairy cows in Flanders, Belgium. J Dairy Res 74:1–21. doi: 10.1017/S0022029907002841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pitkälä A, Haveri M, Pyörälä S, Myllys V, Honkanen-Buzalski T. 2004. Bovine mastitis in Finland 2001–prevalence, distribution of bacteria, and antimicrobial resistance. J Dairy Sci 87:2433–2441. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(04)73366-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sampimon OC, Barkema HW, Berends IMGA, Sol J, Lam TJGM. 2009. Prevalence and herd-level risk factors for intramammary infection with coagulase-negative staphylococci in Dutch dairy herds. Vet Microbiol 134:37–44. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2008.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.White DG, Harmon RJ, Matos JES, Langlois BE. 1989. Isolation and identification of coagulase-negative Staphylococcus species from bovine body sites and streak canals of nulliparous heifers. J Dairy Sci 72:1886–1892. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(89)79307-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.De Vliegher S, Opsomer G, Vanrolleghem A, Devriese LA, Sampimon OC, Sol J, Barkema HW, Haesebrouck F, de Kruif A. 2004. In vitro growth inhibition of major mastitis pathogens by Staphylococcus chromogenes originating from teat apices of dairy heifers. Vet Microbiol 101:215–221. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2004.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Matthews KR, Harmon RJ, Smith BA. 1990. Protective effect of Staphylococcus chromogenes infection against Staphylococcus aureus infection in the lactating bovine mammary gland. J Dairy Sci 73:3457–3462. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(90)79044-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.dos Santos Nascimento J, Fagundes PC, Brito MAVP, Santos KRN, Bastos MCF. 2005. Production of bacteriocins by coagulase-negative staphylococci involved in bovine mastitis. Vet Microbiol 106:61–71. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2004.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Braem G, Stijlemans B, Van Haken W, De Vliegher S, De Vuyst L, Leroy F. 2014. Antibacterial activities of coagulase-negative staphylococci from bovine teat apex skin and their inhibitory effect on mastitis-related pathogens. J Appl Microbiol 116:1084–1093. doi: 10.1111/jam.12447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cotter PD, Hill C, Ross RP. 2005. Bacteriocins: developing innate immunity for food. Nat Rev Microbiol 3:777–788. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cotter PD, Ross RP, Hill C. 2013. Bacteriocins—a viable alternative to antibiotics? Nat Rev Microbiol 11:95–105. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sears PM, Smith BS, Stewart WK, Gonzalez RN, Rubino SD, Gusik SA, Kulisek ES, Projan SJ, Blackburn P. 1992. Evaluation of a nisin-based germicidal formulation on teat skin of live cows. J Dairy Sci 75:3185–3190. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(92)78083-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Crispie F, Twomey D, Flynn J, Hill C, Ross P, Meaney W. 2005. The lantibiotic lacticin 3147 produced in a milk-based medium improves the efficacy of a bismuth-based teat seal in cattle deliberately infected with Staphylococcus aureus. J Dairy Res 72:159–167. doi: 10.1017/S0022029905000816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marsh AJ, O'Sullivan O, Ross RP, Cotter PD, Hill C. 2010. In silico analysis highlights the frequency and diversity of type 1 lantibiotic gene clusters in genome sequenced bacteria. BMC Genomics 11:679–700. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-11-679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Begley M, Cotter PD, Hill C, Ross RP. 2009. Identification of a novel two-peptide lantibiotic, lichenicidin, following rational genome mining for LanM proteins. Appl Environ Microbiol 75:5451–5460. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00730-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kjos M, Borrero J, Opsata M, Birri DJ, Holo H, Cintas LM, Snipen L, Hernández PE, Nes IF, Diep DB. 2011. Target recognition, resistance, immunity and genome mining of class II bacteriocins from Gram-positive bacteria. Microbiology 157:3256–3267. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.052571-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang H, Fewer DP, Sivonen K. 2011. Genome mining demonstrates the widespread occurrence of gene clusters encoding bacteriocins in cyanobacteria. PLoS One 6:e22384. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0022384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Singh M, Sareen D. 2014. Novel LanT associated lantibiotic clusters identified by genome database mining. PLoS One 9:e91352. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0091352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Azevedo AC, Bento CBP, Ruiz JC, Queiroz MV, Mantovani HC. 2015. Distribution and genetic diversity of bacteriocin gene clusters in rumen microbial genomes. Appl Environ Microbiol 81:7290–7304. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01223-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Letzel A-C, Pidot SJ, Hertweck C. 2014. Genome mining for ribosomally synthesized and post-translationally modified peptides (RiPPs) in anaerobic bacteria. BMC Genomics 15:983. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-15-983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Singh NP, Tiwari A, Bansal A, Thakur S, Sharma G, Gabrani R. 2015. Genome level analysis of bacteriocins of lactic acid bacteria. Comput Biol Chem 56:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.compbiolchem.2015.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Walsh CJ, Guinane CM, Hill C, Ross RP, O'Toole PW, Cotter PD. 2015. In silico identification of bacteriocin gene clusters in the gastrointestinal tract, based on the Human Microbiome Project's reference genome database. BMC Microbiol 15:183. doi: 10.1186/s12866-015-0515-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Naushad S, Barkema H, Luby C, Condas L, Nobrega D, Carson D, De Buck J. 2016. Comprehensive phylogenetic analysis of bovine non-aureus staphylococci species based on whole-genome sequencing. Front Microbiol 7:1990. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.01990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Iwatsuki M, Tomoda H, Uchida R, Gouda H, Hirono S, Omura S. 2006. Lariatins, antimycobacterial peptides produced by rhodococcus sp. K01-B0171, have a lasso structure. J Am Chem Soc 128:7486–7491. doi: 10.1021/ja056780z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bierbaum G, Götz F, Peschel A, Kupke T, van de Kamp M, Sahl HG. 1996. The biosynthesis of the lantibiotics epidermin, gallidermin, Pep5 and epilancin K7. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 69:119–127. doi: 10.1007/BF00399417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Asaduzzaman SM, Sonomoto K. 2009. Lantibiotics: diverse activities and unique modes of action. J Biosci Bioeng 107:475–487. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiosc.2009.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Knerr PJ, van der Donk WA. 2012. Discovery, biosynthesis, and engineering of lantipeptides. Annu Rev Biochem 81:479–505. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-060110-113521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bastos MCF, Ceotto H, Coelho MLV, Nascimento JS. 2009. Staphylococcal antimicrobial peptides: relevant properties and potential biotechnological applications. Curr Pharm Biotechnol 10:38–61. doi: 10.2174/138920109787048580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nascimento JS, Ceotto H, Nascimento SB, Giambiagi-deMarval M, Santos KRN, Bastos MCF. 2006. Bacteriocins as alternative agents for control of multiresistant staphylococcal strains. Lett Appl Microbiol 42:215–221. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-765X.2005.01832.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Varella Coelho ML, Nascimento JS, Fagundes PC, Madureira DJ, Oliveira SS, Vasconcelos Paiva Brito MA, Freire Bastos MDC. 2007. Activity of staphylococcal bacteriocins against Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus agalactiae involved in bovine mastitis. Res Microbiol 158:625–630. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2007.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lubelski J, Rink R, Khusainov R, Moll GN, Kuipers OP. 2008. Biosynthesis, immunity, regulation, mode of action and engineering of the model lantibiotic nisin. Cell Mol Life Sci 65:455–476. doi: 10.1007/s00018-007-7171-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sashihara T, Toshihiro S, Hirokazu K, Toshimasa H, Asaho A. 2000. A novel lantibiotic, Nukacin ISK-1, of Staphylococcus warneri ISK-1. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 64:2420. doi: 10.1271/bbb.64.2420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ceotto H, Holo H, da Costa KFS, Nascimento JS, Salehian Z, Nes IF, Bastos MDC. 2010. Nukacin 3299, a lantibiotic produced by Staphylococcus simulans 3299 identical to nukacin ISK-1. Vet Microbiol 146:124–131. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2010.04.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dischinger J, Josten M, Szekat C, Sahl H-G, Bierbaum G. 2009. Production of the novel two-peptide lantibiotic lichenicidin by Bacillus licheniformis DSM 13. PLoS One 4:e6788. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McClerren AL, Cooper LE, Quan C, Thomas PM, Kelleher NL, van der Donk WA. 2006. Discovery and in vitro biosynthesis of haloduracin, a two-component lantibiotic. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103:17243–17248. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606088103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fluhe L, Marahiel MA. 2013. Radical S-adenosylmethionine enzyme catalyzed thioether bond formation in sactipeptide biosynthesis. Curr Opin Chem Biol 17:605–612. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2013.06.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Arnison PG, Bibb MJ, Bierbaum G, Bowers AA, Bugni TS, Bulaj G, Camarero JA, Campopiano DJ, Challis GL, Clardy J, Cotter PD, Craik DJ, Dawson M, Dittmann E, Donadio S, Dorrestein PC, Entian K-D, Fischbach MA, Garavelli JS, Göransson U, Gruber CW, Haft DH, Hemscheidt TK, Hertweck C, Hill C, Horswill AR, Jaspars M, Kelly WL, Klinman JP, Kuipers OP, Link AJ, Liu W, Marahiel MA, Mitchell DA, Moll GN, Moore BS, Müller R, Nair SK, Nes IF, Norris GE, Olivera BM, Onaka H, Patchett ML, Piel J, Reaney MJT, Rebuffat S, Ross RP, Sahl H-G, Schmidt EW, Selsted ME, et al. . 2013. Ribosomally synthesized and post-translationally modified peptide natural products: overview and recommendations for a universal nomenclature. Nat Prod Rep 30:108–160. doi: 10.1039/C2NP20085F. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Murphy K, O'Sullivan O, Rea MC, Cotter PD, Ross RP, Hill C. 2011. Genome mining for radical SAM protein determinants reveals multiple sactibiotic-like gene clusters. PLoS One 6:e20852. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shelburne CE, An FY, Dholpe V, Ramamoorthy A, Lopatin DE, Lantz MS. 2007. The spectrum of antimicrobial activity of the bacteriocin subtilosin A. J Antimicrob Chemother 59:297–300. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkl495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Maksimov MO, Link AJ. 2014. Prospecting genomes for lasso peptides. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol 41:333–344. doi: 10.1007/s10295-013-1357-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hegemann JD, Zimmermann M, Xie X, Marahiel MA. 2015. Lasso peptides: an intriguing class of bacterial natural products. Acc Chem Res 48:1909–1919. doi: 10.1021/acs.accounts.5b00156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Potter A, Ceotto H, Coelho MLV, Guimarães AJ, Bastos MDC. 2014. The gene cluster of aureocyclicin 4185: the first cyclic bacteriocin of Staphylococcus aureus. Microbiology 160:917–928. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.075689-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Martínez B, Fernández Ma Suárez JE, Rodríguez A. 1999. Synthesis of lactococcin 972, a bacteriocin produced by Lactococcus lactis IPLA 972, depends on the expression of a plasmid-encoded bicistronic operon. Microbiology 145:3155–3161. doi: 10.1099/00221287-145-11-3155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kjos M, Nes IF, Diep DB. 2009. Class II one-peptide bacteriocins target a phylogenetically defined subgroup of mannose phosphotransferase systems on sensitive cells. Microbiology 155:2949. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.030015-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nascimento JS, Abrantes J, Giambiagi-deMarval M, Bastos MCF. 2004. Growth conditions required for bacteriocin production by strains of Staphylococcus aureus. World J Microbiol Biotechnol 20:941–947. doi: 10.1007/s11274-004-3626-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Leroy F, De Vuyst L. 2004. Lactic acid bacteria as functional starter cultures for the food fermentation industry. Trends Food Sci Technol 15:67–78. doi: 10.1016/j.tifs.2003.09.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Reyher KK, Dufour S, Barkema HW, Des Côteaux L, DeVries TJ, Dohoo IR, Keefe GP, Roy JP, Scholl DT. 2011. The national cohort of dairy farms–a data collection platform for mastitis research in Canada. J Dairy Sci 94:1616–1626. doi: 10.3168/jds.2010-3180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Condas L, De Buck J, Nobrega D, Carson D, Naushad S, Kastelic J, De Vliegher S, Zadoks RN, Middleton J, Dufour S, Barkema HW. 2017. Prevalence of non-aureus staphylococci isolated from milk samples in Canadian dairy herds. J Dairy Sci 100:5592–5612. doi: 10.3168/jds.2016-12478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schillinger U, Lücke FK. 1989. Antibacterial activity of Lactobacillus sake isolated from meat. Appl Environ Microbiol 55:1901–1906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Burianek LL, Yousef AE. 2000. Solvent extraction of bacteriocins from liquid cultures. Lett Appl Microbiol 31:193–197. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.2000.00802.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Köster J, Rahmann S. 2012. Snakemake—a scalable bioinformatics workflow engine. Bioinformatics 28:2520–2522. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Martin M. 2011. Cutadapt removes adapter sequences from high-throughput sequencing reads. EMBnet J 17:10–12. doi: 10.14806/ej.17.1.200. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nurk S, Bankevich A, Antipov D, Gurevich AA, Korobeynikov A, Lapidus A, Prjibelski AD, Pyshkin A, Sirotkin A, Sirotkin Y, Stepanauskas R, Clingenpeel SR, Woyke T, McLean JS, Lasken R, Tesler G, Alekseyev MA, Pevzner PA. 2013. Assembling single-cell genomes and mini-metagenomes from chimeric MDA products. J Comput Biol 20:714–737. doi: 10.1089/cmb.2013.0084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Li H, Durbin R. 2009. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows–Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 25:1754–1760. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Seemann T. 2014. Prokka: rapid prokaryotic genome annotation. Bioinformatics 30:2068–2069. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gurevich A, Saveliev V, Vyahhi N, Tesler G. 2013. QUAST: quality assessment tool for genome assemblies. Bioinformatics 29:1072–1075. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Priyam A, Woodcroft BJ, Rai V, Munagala A, Moghul I, Ter F, Gibbins MA, Moon H, Leonard G, Rumpf W, Wurm Y. 2015. Sequenceserver: a modern graphical user interface for custom BLAST databases. bioRxiv doi: 10.1101/033142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Weber T, Blin K, Duddela S, Krug D, Kim HU, Bruccoleri R, Lee SY, Fischbach MA, Müller R, Wohlleben W, Breitling R, Takano E, Medema MH. 2015. antiSMASH 3.0—a comprehensive resource for the genome mining of biosynthetic gene clusters. Nucleic Acids Res 43:W237–W243. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Marchler-Bauer A, Bo Y, Han L, He J, Lanczycki CJ, Lu S, Chitsaz F, Derbyshire MK, Geer RC, Gonzales NR, Gwadz M, Hurwitz DI, Lu F, Marchler GH, Song JS, Thanki N, Wang Z, Yamashita RA, Zhang D, Zheng C, Geer LY, Bryant SH. 2017. CDD/SPARCLE: functional classification of proteins via subfamily domain architectures. Nucleic Acids Res 45:D200–D203. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw1129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kearse M, Moir R, Wilson A, Stones-Havas S, Cheung M, Sturrock S, Buxton S, Cooper A, Markowitz S, Duran C, Thierer T, Ashton B, Meintjes P, Drummond A. 2012. Geneious Basic: an integrated and extendable desktop software platform for the organization and analysis of sequence data. Bioinformatics 28:1647–1649. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Edgar RC. 2010. Search and clustering orders of magnitude faster than BLAST. Bioinformatics 26:2460–2461. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Katoh K, Standley DM. 2013. MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: improvements in performance and usability. Mol Biol Evol 30:772–780. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Price MN, Dehal PS, Arkin AP. 2010. FastTree 2—approximately maximum-likelihood trees for large alignments. PLoS One 5:e9490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Whelan S, Goldman N. 2001. A general empirical model of protein evolution derived from multiple protein families using a maximum-likelihood approach. Mol Biol Evol 18:691–699. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a003851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ozer EA, Allen JP, Hauser AR. 2014. Characterization of the core and accessory genomes of Pseudomonas aeruginosa using bioinformatic tools Spine and AGEnt. BMC Genomics 15:737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Edgar RC. 2004. MUSCLE: a multiple sequence alignment method with reduced time and space complexity. BMC Bioinformatics 5:113. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-5-113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Waterhouse AM, Procter JB, Martin DMA, Clamp M, Barton GJ. 2009. Jalview version 2—a multiple sequence alignment editor and analysis workbench. Bioinformatics 25:1189–1191. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.