Abstract

Strains of Serratia marcescens, originally isolated from the gut lumen of adult female Anopheles stephensi mosquitoes, established persistent infection at high rates in adult A. stephensi whether fed to larvae or in the sugar meal to adults. By contrast, the congener S. fonticola originating from Aedes triseriatus had lower infection in A. stephensi, suggesting co-adaptation of Serratia strains in different species of host mosquitoes. Coinfection at high infection rate in adult A. stephensi resulted after feeding S. marcescens and Elizabethkingia anophelis in the sugar meal, but when fed together to larvae, infection rates with E. anophelis were much higher than were S. marcescens in adult A. stephensi, suggesting a suppression effect of coinfection across life stages. A primary isolate of S. marcescens was resistant to all tested antibiotics, showed high survival in the mosquito gut, and produced alpha-hemolysins which contributed to lysis of erythrocytes ingested with the blood meal. Genomes of two primary isolates from A. stephensi, designated S. marcescens ano1 and ano2, were sequenced and compared to other Serratia symbionts associated with insects, nematodes and plants. Serratia marcescens ano1 and ano2 had predicted virulence factors possibly involved in attacking parasites and/or causing opportunistic infection in mosquito hosts. S. marcescens ano1 and ano2 possessed multiple mechanisms for antagonism against other microorganisms, including production of bacteriocins and multi-antibiotic resistance determinants. These genes contributing to potential anti-malaria activity including serralysins, hemolysins and chitinases are only found in some Serratia species. It is interesting that genome sequences in S. marcescens ano1 and ano2 are distinctly different from those in Serratia sp. Ag1 and Ag2 which were isolated from Anopheles gambiae. Compared to Serratia sp. Ag1 and Ag2, S. marcescens ano1 and ano2 have more rRNAs and many important genes involved in commensal and anti-parasite traits.

Keywords: Serratia, antimicrobial, symbionts, commensal, virulence factors, comparative genomics

Introduction

Bacteria of the genus Serratia are Gram-negative, rod-shaped, facultative anaerobes (Grimont and Grimont, 2006). These bacteria are ubiquitously distributed in soil, sediments, water, plant roots, on surfaces of animals, as well as in the gastrointestinal tract of animals. Serratia marcescens or S. marcescens-like bacteria have been reported living symbiotically with, and sometimes causing disease in, economically important insects and nematodes (Benoit et al., 1990; Stanley et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2014; Aggarwal et al., 2015; Pei et al., 2015; Chen et al., 2016). For example, S. marcescens infection caused acute mortality in mosquitoes and reduced fitness in survivors (Bahia et al., 2014). Some S. marcescens strains were pathogenic to apple maggot flies Rhagoletis pomonella and to house flies Musca domestica (Benoit et al., 1990; Lauzon et al., 2003). Chitinase-producing S. marcescens showed insecticidal activity in caterpillars of the moth, Spodoptera litura (Aggarwal et al., 2015). Nematodes in soil tolerate infection with S. marcescens, and transfer the infection upon encounter to their insect hosts, whence pathology in the insects becomes apparent (Abebe et al., 2011). Pathology in insects infected by S. marcescens appears to be related to establishment of disseminated infection in the hemolymph, whilst infection in the gut lumen is tolerated (Nehme et al., 2007).

The physiological activity of S. marcescens in the mosquito gut lumen remains largely unknown. However, presence of S. marcescens in that lumen is associated with anti-malaria parasite activity, presenting the possibility that manipulation of natural populations of vector mosquitoes with S. marcescens infection could control malaria transmission. For example, introduction of a low dose of S. marcescens (103 cells/μl) per os suppressed Plasmodium development in the Anopheles gambiae gut (Bahia et al., 2014). In the same study, in vitro tests demonstrated that live S. marcescens cells or cell-free culture broth inhibited Plasmodium ookinete development, a stage that forms in the mosquito gut lumen (Bahia et al., 2014). Moreover, in Anopheles albimanus, only 1% of female mosquitoes became infected with Plasmodium vivax when S. marcescens was simultaneously introduced per os in the blood meal, whereas 71% of mosquitoes became infected with advanced stages of the parasite when S. marcescens was excluded from the blood meal (Gonzalez-Ceron et al., 2003). The inhibition of Plasmodium development in the Anopheles midgut by S. marcescens could be mediated by multiple mechanisms, such as production of metabolites with anti-parasite properties (Lazaro et al., 2002; Azambuja et al., 2005; Bahia et al., 2014). For example, prodigiosin or its tripyrrole pigment derivatives, produced by various bacteria including S. marcescens, demonstrated strong inhibitory activity against P. falciparum (Lazaro et al., 2002; Azambuja et al., 2005). Experiments provided evidence that direct contact between S. marcescens and Plasmodium cells inhibited parasite development in the midgut lumen, an effect possibly mediated by increased expression of a flagellum-specific biosynthesis pathway (Bando et al., 2013). Serratia marcescens modulated the mosquito immune system to interfere with the development of malaria parasites (Stathopoulos et al., 2014). Further, genetic variation in immune-related genes influenced the course of infection of S. marcescens in A. gambiae, involving the peptidoglycan recognition factor, type 3 fibronectin binding proteins, and antibacterial activity of a gustatory Gr9 receptor (Stathopoulos et al., 2014).

Characterizations of the adult Anopheles microbiome showed that Serratia bacteria were a predominant member of the microbiota in the midgut lumen (Wang et al., 2011; Chen et al., 2016). Genomes of Serratia sp. Ag1 and Ag2 isolated from the African malaria vector mosquito A. gambiae were recently sequenced and annotated, because of the potential importance of these bacteria to the mosquitoes' immune response, to malaria parasite development, and to pathogenicity of the bacteria to mosquitoes (Bahia et al., 2014; Pei et al., 2015). Nevertheless, comparative genomic and functional analyses are lacking in those Serratia forming symbiotic and pathogenic relationships with insect hosts; nor are there detailed studies on interactions between commensal Serratia and other bacterial symbionts in mosquito hosts. Given that S. marcescens has traits suitable for control of mosquito-borne parasites, a physiological and comparative genome analysis for S. marcescens would contribute to (1) development of an efficient paratransgenesis biocontrol strategy (i.e., malaria vector control), (2) incorporation of the effectors/virulence factors from Serratia into mosquito symbionts for efficient paratransgenesis systems, and (3) elucidation of the ecophysiology of the diversity of commensals in the mosquito midgut (Bando et al., 2013; Bahia et al., 2014; Aggarwal et al., 2015). Here, we investigated the interaction, persistence and competition amongst different Serratia species and strains associated with mosquito gut infection, and with the bacterium Elizabethkingia anophelis, another commensal found in that same environment, often together with S. marcescens. Further, we tested antimicrobial resistance and hemolytic capabilities to better understand the physiological role of S. marcescens as commensals in midgut. Lastly, with the completion of genome sequencing, assembly and annotation, we explored gene repertoire and gene diversity in comparison with other Serratia strains and species.

Materials and methods

Culture conditions

Serratia marcescens strains, designated here ano1 and ano2, were isolated from two female A. stephensi (LBT and LB1) in our laboratory colony by aseptic dissection of the midgut using sterile tuberculin syringes and needles, followed by plating midgut contents plus sterile saline on Luria-Bertani agar (BD, USA) (Chen et al., 2016). Serratia fonticola strain MSU001 was isolated similarly from a female Aedes triseriatus Say from our laboratory colony. History of mosquito strains is reported elsewhere (Chen et al., 2014, 2015, 2016). Serratia marcescens strain ano1, S. marcescens strain ano2, Serratia fonticola strain MSU001 and their derivatives (see below) were cultured in LB by shaking at 28°C. A dual luciferase expression system was used to mark bacterial strains for quantification. A NanoLuc luciferase-tagged E. anophelis (SCH814) used in this study was previously established and grown on CYE medium (Chen et al., 2015); the firefly system was developed for strains isolated here (see below). Escherichia coli DH5α and E. coli λ pir were used for cloning and conjugative transfer of DNA, respectively. E. coli cells for experiments were grown aerobically in LB broth at 37°C. Bacto agar (Difco, Detroit, MI) was added to a final concentration of 20 g/l. Kanamycin (100 μg/ml) was added for plasmid selection in E. coli, but a higher concentration of kanamycin (600 μg/ml) was required for plasmid selection in Serratia spp.

Molecular manipulation

Isolation and purification of bacterial genomic DNA were performed with the Wizard Genomic DNA Purification Kit (Promega, CA, USA). Integrity and quantity of DNA were assessed using gel electrophoresis, a NanoDrop 2000 UV-Vis spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, MA, USA) and Qubit 2.0 fluorometer (Life Technologies, MA, USA), respectively.

The firefly reporter vector was developed based on the wide-range plasmid pBBR1 MCS2 (Chen and Hickey, 2011). The fluc gene was cloned from vector GL4.50 (Promega, WI) with forward primer Walker219 (aggatcctttaagaaggagatatacatatggaagacgccaaaaacataaag) and reverse primer Walker208 (agcatgcttacaatttggactttccgcccttc) with BamHI and SphI on its 5′ and 3′-end, respectively. The amplicon was gel purified and ligated into the T-easy vector (pSCH955). The insert was released from pSCH955 by the restriction enzymes BamHI and SphI and cloned into the same sites on pBBR1 MCS2 downstream of the Plac promoter (pSCH956). Plasmid pSCH956 was introduced into E. coli S17 lamda pir to facilitate conjugation, creating the donor strain for the fluc reporter plasmid (SCH981). SCH981 was mixed with recipient S. marcescens ano1 or S. fonticola MSU001 conjugatively to transfer plasmid pSCH956, leading to firefly reporter strains SCH983 (S. marcescens) or SCH985 (S. fonticola), respectively.

Bacterial interactions and luciferase activity determination

Laboratory rearing procedures for A. stephensi mosquitoes were previously described (Chen et al., 2015). To investigate persistence of infection of bacteria in host mosquitoes, we performed experiments with S. marcescens alone, S. marcescens and E. anophelis together, or S. fonticola and E. anophelis together, using strains with NanoLuc and firefly reporters as described above to quantify presence of bacteria in the mosquito gut lumen. The first experiment was designed to investigate bacterial persistence in live larvae, across molts and metamorphosis past the pupal stage into the adult stage, when bacteria were fed to larvae. When larval A. stephensi reached 3rd instar, individual reporter bacteria SCH983 (S. marcescens with firefly reporter), SCH985 (S. fonticola with firefly reporter) or SCH814 (E. anophelis with NanoLuc reporter) or combinations of them (SCH814/SCH983 or SCH814/SCH985) were added to sterile water in plastic dishes (final concentration adjusted to approximately 4 × 108 CFU/ml) containing 50 larvae, and larvae allowed to feed on the suspension for 24 h, after which the regular larval food regime (Tetra fish food) was continued. Upon metamorphosis, pupae were retrieved, rinsed with sterile water, and transferred into distilled water in cages for adult emergence. After holding the adults for 4 days (during which time they were provided 10% sucrose solution prepared with sterile water), at least 24 adults were randomly sampled and proceeded as described previously (Chen et al., 2015). A second experiment was conducted to investigate persistence of bacterial infection when introduced to adult mosquitoes. The same bacterial preparations as those described in the larval experiment above were fed to adults (1 day of post-emergence) in 10% sucrose solution. After ad lib. feeding for 24 h, the bacterial solution was replaced with fresh, sterile 10% sucrose solution and mosquitoes were sampled at intervals thereafter, and surface-sterilized by immersion in 70% ethanol followed by extensive washings in sterile Milli-Q water. Mosquitoes were homogenized in sterile phosphate buffered saline (PBS), diluted if necessary, and immediately subjected to the Nano-Glo Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay (Promega, WI).

Antibiotic susceptibility test

Susceptibility to different antibiotics was tested by minimal inhibition concentration methods in LB broth (European Committee for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing of the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases, 2003). Cultures were incubated at 28°C for 24 h under aerobic conditions and the OD600nm interpreted according to the manufacturer's instructions. Assays were performed in triplicates.

Urase production

Urease production was tested by using BBL urase test broth (BD, MD, USA). Serratia marcescens strain ano1 or E. coli DH5α was inoculated to the broth and incubated for 48 h.

Hemolytic assays and erythrocyte digestion test

Hemolysin production in S. marcescens strain ano1 was tested by inoculating bacterial cells on Remel Blood Agar plate (Thermo Scientific, KS). Hemolytic activity was evaluated following incubation at 28°C for 48 h. Staphylococcus aureus and Elizabethkingia meningoseptica were used as the positive controls of beta- and alpha-hemolysin, respectively. Bovine whole blood cells (Hemostat Laboratories, CA) were washed with phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and re-suspended in 1 mL of PBS. Serratia marcescens strain ano1 (final concentration, 4.5 × 108 cells/mL) was incubated with above washed blood cells for 48 h. The erythrocytes were counted using a hemocytometer under microscopy. The negative control was the same as the treatment without introduction of bacteria.

Genome sequencing, assembly, and annotation

Next generation sequencing (NGS) libraries were prepared using the Illumina TruSeq Nano DNA Library Preparation Kit following standard procedures recommended by the manufacturer. Completed libraries were evaluated using a combination of Qubit dsDNA HS, Caliper LabChipGX HS DNA and Kapa Illumina Library Quantification qPCR assays. Libraries were combined in a single pool for multiplexed sequencing and this pool was loaded on one standard MiSeq flow cell (v2) and sequencing was performed in a 2 × 250 bp paired end format using a v2, 500 cycle reagent cartridge. Base calling was done by Illumina Real Time Analysis (RTA) v1.18.54 and output of RTA was demultiplexed and converted to FastQ format with Illumina Bcl2fastq v1.8.4.

De novo assembly was performed using SPAdes (version 3.9.0) (Bankevich et al., 2012). The reads were assembled using SPAdes (version 3.9.0) and further edited by using DNASTAR (v1.12) (Nurk et al., 2013). Initial prediction and annotation of open reading frames (ORF) and tRNA/rRNA gene prediction were carried out with the Rapid Annotation using Subsystem Technology server (RAST) (Overbeek et al., 2014). Gene annotation was carried out by NCBI Prokaryotic Genome Automatic Annotation Pipeline (PGAAP 3.3) (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genome/annotation_prok/).

Bioinformatics

The functional categorization and classification for predicted ORFs were performed by RAST server-based SEED viewer (Overbeek et al., 2014). Multi-drug resistance genes were predicted in the Comprehensive Antibiotic Resistance Database (McArthur et al., 2013). Prophage prediction was done with PHAST (Zhou et al., 2011) and Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats (CRISPR) were predicted by CRISPRfinder (Grissa et al., 2007). For genome similarity assessment, average nucleotide identity (ANI) was computed using EDGAR 2.0 (Blom et al., 2016).

The pan genome, core genome, and specific genes of S. marcescens ano1 and ano2 were analyzed by comparing with those in 11 representative Serratia genomes using EDGAR 2.0 (Blom et al., 2016). The development of pan genome and core genome sizes was approximated using the core/pan development feature. The core genome calculated by EDGAR 2.0 was used to infer a phylogeny for the 13 Serratia genomes in this study. The 27,144 amino acid sequences (2,088 per genome) of the core genome were aligned set-wise using MUSCLE v3.8.31 (Edgar, 2004), resulting in a large multiple alignment with 9,015,188 amino acid residues in total (693,476 per genome). This large alignment was used to construct a phylogenetic tree using the neighbor-joining method as implemented in the PHYLIP package (Felsenstein, 1989).

Accession of the genome sequences

The data from these Whole Genome Shotgun projects have been deposited at DDBJ/ENA/GenBank under the accession. The version described in this paper is version MJVB00000000 and MJVC00000000 for S. marcescens ano1 and ano2, respectively. The BioProject designations for this project are PPRJNA340333 and PRJNA340334, and BioSample accession numbers are SAMN05712591 and SAMN05712592 for S. marcescens ano1 and ano2, respectively.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using SAS (version 9.2; SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

Colonization and interaction by Serratia and E. anophelis in mosquitoes

When S. marcescens ano1 was fed to 3rd instar A. stephensi larvae, the infection persisted to the adult stage for 62.5% (15/24) of adults at 4 days after adult emergence (Table 1), as evidenced by positive luciferase assay relative to negative controls. When S. marcescens ano1 was fed in a sugar meal to adult mosquitoes for 24 h, infection rates of the guts were 98.5% (39/40) when dissected 4 days later (Table 1). By contrast, 17.1% (6/35) and 32.5% (13/40) of the guts of A. stephensi adults were positive for S. fonticola MSU001 when fed to larval and adult stages, respectively, demonstrating that S. fonticola isolated from A. triseriatus had relatively poorer colonization and persistence than did S. marcescens in A. stephensi. When E. anophelis strain was fed to larvae and adults respectively, 87.5% (35/40) and 100% (40/40) infection rates were observed (Table 1). When S. marcescens was introduced together with E. anophelis to the adult host by sugar meal at a cell concentration ratio of 1:1, both of the bacteria had similar infection rates (92.5 and 95%, respectively), using the Dual Luciferase assay. These infection rates were comparable to those in adults introduced with a single bacterial species (Table 1). However, when they were co-introduced in the larval stage, the S. marcescens infection in A. stephensi (22.9%) was lower than that of the single S. marcescens species (62.5%), while NanoLuc-labeled E. anophelis after feeding to larvae reached an infection rate of 100% in adults whether fed with S. marcescens or fed alone. A similar trend was also observed in the co-infection experiment between S. fonticola and E. anopheles (Table 1). These results further demonstrated that infection rate of S. fonticola in A. stephensi was lower than that of S. marcescens when they were co-introduced at either larval or adult stages, suggesting that S. marcescens was co-adapted for infection in A. stephensi. Overall, the rank of infection rate to A. stephensi for the three selected bacteria was E. anophelis > S. marcescens > S. fonticola.

Table 1.

Interaction among S. marcescens ano1, S. fonticola, and E. anophelis in larval and adult mosquitoes.

| Single | Single | Single | Double | Double | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E. anophelis | S. marcescens | S. fonticola | S. fonticola | E. anophelis | S. marcescens | E. anophelis | |

Larvae

|

87.5% (35/40) | 62.5% (15/24) | 17.1% (6/35) | 7.5% (3/40) | 100% (40/40) | 22.9% (8/35) | 100% (35/35) |

Adults

|

100% (40/40) | 98.5% (39/40) | 32.5% (13/40) | 25% (10/40) | 90% (36/40) | 92.5% (37/40) | 95% (38/40) |

Individual S. marcescens ano1 (Firefly reporter), S. fonticola (Firefly reporter), and E. anophelis (NanoLuc reporter) or combinations of them were orally fed to larval or adult mosquitoes. The bacterial infection in mosquito was quantified by using Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay kit as described in Materials and Methods. The infection rates are shown as percentages on the top and the numbers in brackets are individuals analyzed.

Genome features and phylogenetic inferences

The assembly of strain ano1 contained 44 contigs with a size of 5.45 Mbp (Table 2). The assembly of strain ano2 contained 71 contigs with a size of 5.47 Mbp (Table 2). The ano1 genome included 5,082 coding sequences (CDS) and 119 RNA genes. The ano2 genome included 5,058 CDS and 118 RNA genes (Table 2). Among the 13 Serratia genomes selected for comparative analysis here, ano1 or ano2 had the most CDSs (Table 2). The average GC content for ano1 and ano2 was 59.6 and 59.5%, respectively, consistent with other S. marcescens; however, the average GC content in S. marcescens was much higher than that in other Serratia spp. (Table 2). No plasmid sequence was found in either ano1 or ano2, congruent with our inability to isolate plasmids from the two S. marcescens strains. RAST analysis showed that ano1 and ano2 have at least 589 and 588 subsystems, respectively (Figure S1).

Table 2.

Genome features for selected Serratia spp. or Serratia-like bacteria.

| Strains | Genome size (Mb) | Gene count | CRISPR count | GC (%) | Predicted CDS | Total RNA | Accession number | Isolation site | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S. marcescens ano1 | 5.45 | 5,131 | 0 | 60 | 5,082 | 119 | MJVB00000000 | Mosquito | This study |

| S. marcescens ano2 | 5.47 | 5,176 | 0 | 60 | 5,058 | 118 | MJVC00000000 | Mosquito | This study |

| Serratia sp. Ag1 | 5.35 | 5,061 | 5 | 52 | 4,773 | 85 | JQEI00000000 | Mosquito | Pei et al., 2015 |

| Serratia sp. Ag2 | 5.32 | 5,031 | 5 | 52 | 4,706 | 85 | JQEJ00000000 | Mosquito | Pei et al., 2015 |

| S. marcescens Db11 | 5.11 | 4,831 | 0 | 60 | 4,721 | 110 | HG326223.1 | Drosophila | Iguchi et al., 2014 |

| S. marcescens MCB | 5.30 | 5,048 | 0 | 59 | 4,874 | 174 | JPQY00000000 | Nematodes | Serepa and Gray, 2014 |

| Serratia sp. TEL | 5.00 | 4,732 | 2 | 59 | 4,544 | 188 | KP711410 | Nematodes | Lephoto and Gray, 2015 |

| S. marcescens FGI94 | 4.86 | 4,609 | 4 | 59 | 4,438 | 171 | CP003942 | Fungus garden | Li P. et al., 2015 |

| S. plymuthica S13 | 5.47 | 5,125 | 0 | 56 | 5,018 | 107 | NC_021659 | Plant | Müller et al., 2013 |

| S. proteamaculans 568 | 5.50 | 5,063 | 0 | 55 | 4,954 | 109 | CP000826 | Plant | Abebe-Akele et al., 2015 |

| S. liquefaciens ATCC 27592 | 5.28 | 5,023 | 0 | 55 | 4,914 | 109 | CP006252 | Milk | Nicholson et al., 2013 |

| S. marcescens WW4 | 5.24 | 4,919 | 0 | 60 | 4,818 | 101 | CP003959 | Paper machine | Chung et al., 2013 |

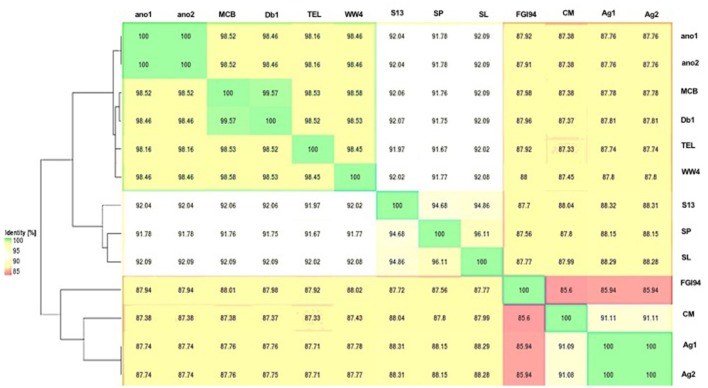

The difference in genome features between ano1 and ano2 was not remarkable (Table 2, Figure 1, and Figure S2). The calculated ANI between ano1 and ano2 shows 100% identity, indicating that S. marcescens ano1 and ano2 were the same strain (Figure 1). ANI values indicated that these two isolates belong to S. marcescens species as they were more than 95% identical to those in S. marcescens MCB (Serepa and Gray, 2014) and S. marcescens Db1 (Flyg et al., 1980), previously isolated from nematodes and fruit flies, respectively (Figure 1). Serratia sp. TEL could be assigned to S. marcescens because it had a high ANI value (>95%) with those of S. marcescens MCB and S. marcescens Db1. It is interesting that, compared to that in S. marcescens FGI94, low ANI values (<89%) in most of the selected Serratia were found, highlighting that different Serratia sp. exist in various insects. Phylogenetic trees (based on genome analysis) showed that ano1 and ano2 were most closely related to Serratia sp. TEL and S. marcescens WW4 (Figure S3). It is interesting that Serratia sp. Ag1 and Ag2 have more CRISPR elements than do other Serratia (Table 2). We did not detect any CRISPR elements in ano1 and ano2. Remarkably, Serratia sp. Ag1 and Ag2 isolated from mosquito A. gambiae have different genome features compared to ano1 and ano2, such as GC content, ANI values and predicted CDS (Table 2, Figure 1, and Figure S3 and see below).

Figure 1.

Average nucleotide identity dendogram for the selected Serratia spp. ANI matrix generated by complete genome sequences was used to calculate an ANI divergence dendrogram. The hosts for these isolates were shown on the right panel. Ano1, S. marcescens ano1; Ano2, S. marcescens ano2; Ag1, Serratia sp. Ag1; Ag2, Serratia sp. Ag2; MCB, S. marcescens MCB; Db11, S. marcescens Db11; TEL, Serratia sp. TEL; FGI94, S. marcescens FGI94; Sp, S. plymuthica S13; Sl, S. liquefaciens ATCC 27592; WW4, S. marcescens WW4.

Serratia marcescens strains ano1 and ano2 had 5 predicted prophages (Table S1). Two of the prophages (prophage 3 and 4) were possibly complete because they consisted of tails, heads, portals, integrases, lysins and other component proteins involving phage structure and assembly. Mosquito isolates Ag1 and Ag2 have two incomplete prophages. The number of predicted prophages in other Serratia ranged from 1 to 8. Collectively, these prophages varied in size and gene organization, indicating their diversity in Serratia (Table S1).

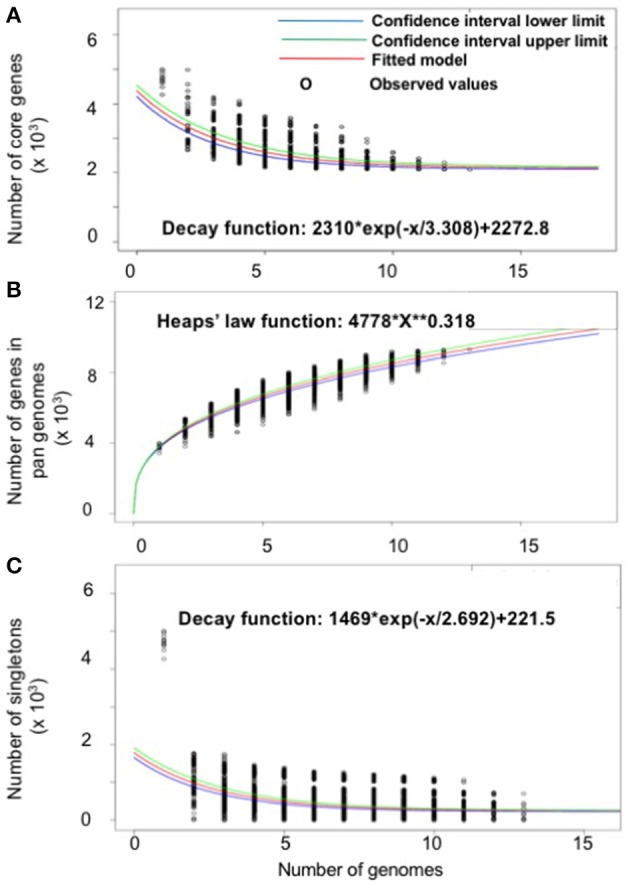

Gene repertoire of S. marcescens

The gene repertoire of the selected Serratia species was analyzed using their ubiquitous genes (core genome) and different homologous genes families (pan-genome) amongst the selected Serratia genomes. The pan-genome plot shows that the power trend line had not reached a plateau (Figure 2A), demonstrating that Serratia displays an open pan-genome. Serratia core genome analysis showed that the number of shared genes decreased with the addition of the input genomes and was predicted to converge against 2,127 (see Figure 2B). Singleton development plot data indicated that up to 240 new genes could be expected with every newly sequenced genome (Figure 2C). The core genome for the 13 selected Serratia was calculated to be 2,088 CDS per genome; given the assumption that the approximation slightly over-predicts the real core genome size, the current core genome likely represents the Serratia genus quite well.

Figure 2.

Pan, core, and singleton genome evolution according to the number of selected Serratia genomes. (A) Number of genes (pan-genome) for a given number of genomes sequentially added. (B) Number of shared genes (core genome) as a function of the number of genomes sequentially added. (C) Number of unique genes (accessory genome) for a given number of genomes sequentially added.

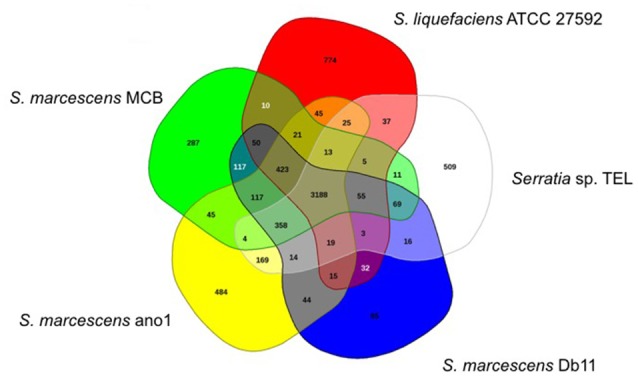

Serratia marcescens ano1 and ano2 shared at least 4985 genes (data not shown). Only 13 and 12 genes were uniquely present in strains ano1 and ano2, respectively, a result within the error rate of incomplete sequencing and likely artifact. Also, among its relatives, the ano1 genome shared in common genes ranging from 2936 to 3749 in number, with the lowest number shared with Serratia sp. Ag2, indicating diverse physiological functions in the selected Serratia (Figure 3 and Figure S4). For example, S. marcescens ano1 shared at least 4198, 4178, 4172, and 3788 common genes with strains S. liquefaciens, S. marcescens Db11, S. marcescens MCB and Serratia sp. TEL, which accounts for approximately 84.0, 83.6, 83.5, and 75.8% of its encoding genes, respectively; the above 5 selected S. marcescens shared 3188 common genes (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Venn diagram of shared and unique genes in the selected Serratia. The unique and shared genome among the compared genomes was determined by a dual cutoff of 30% or greater amino acid identity and sequence length coverage of at least 70%. Analysis was done using the MAUVE genome alignment tool. 1, S. liquefaciens; 2, S. marcescens MCB; 3, S. marcescens ano1; 4, S. marcescens Db11, and 5, Serratia sp. TEL.

Antimicrobial resistance

Serratia marcescens ano1 was resistant to nearly all of the selected antibiotics including class β-lactams, aminoglycosides, tetracycline, aminoglycosides, macrolides, glycopeptides, and ansamycins, showing that ano1 is a multi-drug resistant strain (Table 3). At least 18 predicted enzymes/proteins conferring antibiotic resistance were predicted by CARD and RAST SEED subsystem (Figure S1 and Table S2). The predicted proteins include those conferring antibiotic resistance to β-lactams, fosfomycin, mupirocin, polymyxin, aminocoumarin, aminoglycoside, isoniazid and fluoroquinolone. Furthermore, up to 37 efflux pumps were identified, possibly contributing to tetracycline, rifampin, aminocoumarin, aminoglycoside, fluoroquinolone, macrolide as well as β-lactam resistance (Table S2). Comparative study of Serratia genomes showed that all of them have potential resistance against four classes of antibiotics: fluoroquinolone, polymyxin, mupirocin, and fosfomycin.

Table 3.

Antibiotic susceptibility tests in S. marcescens.

| Drug class | Antibiotics | Susceptibility* |

|---|---|---|

| Ansamycins | Rifampicin | R |

| Glycopeptides | Vancomycin | R |

| Macrolides | Erythromycin | R |

| Chloramphenicol | R | |

| Pimaricin | R | |

| Aminoglycosides | Streptomycin | R |

| Phenylmethanesulfonyl fluroide | R | |

| Phosphomycin | R | |

| Tetracyclines | Tetracycline | R |

| β-lactam | Ampicillin | R |

| Carbenicillin | R | |

| Cephalosporin | R | |

| Aminoglycosides | Kanamycin | R |

R refers to resistant. The final concentration for tested antibiotics is 10 μg/ml.

Most of the S. marcescens strains had genes encoding antimicrobial compound synthesis proteins such as hydrogen cyanide (OHT38223), bacteriocin (colicin V, OHT33745) and pyoverdine (OHT34953) (also see next), indicating that they have potential to inhibit the growth of similar or closely related bacterial strain(s) (Table S3). Ano1 and ano2 carried the gene cluster of biosynthesis of bacteriocin, consisting of 19 opening reading frames (ORFs). Most of them were conserved among the Serratia genomes examined here, including those isolated from mosquitoes and nematodes (Table S3). It is noteworthy that prodigiosin gene synthesis clusters were absent in S. marcescens ano1, also lacking in several insect symbionts (Table S4).

Virulence factors predicted in Serratia

Strains ano1 and ano2 had a probability of acting as a pathogen of 72.9% according to the probability values assigned by PathogenFinder (Cosentino et al., 2013). Ano1 genome matched 41 pathogenic families and 12 non-pathogenic families in the database (data not shown). Furthermore, a total of 37 putative virulence factors were predicted by VFDB, which mainly account for flagella formation, lipooligosaccharide (LOS), attacking enzymes, iron uptake and transportation, different secretion systems and hemolysis of red blood cells (Table 4). It is interesting that several predicted virulence factors in ano1 and ano2 such as gluP, manC, urase, shu, and fleQ were either missed or showed low identity (<40%) in mosquito symbionts Serratia sp. Ag1 and Ag2 (Table 4). For example, gluP (encoding L-fucose:H+ symporter permease, BGV45_11240), participates in chronic infection and acts an important virulence factor in Brucella abortus (Xavier Mariana et al., 2013). manC, a mannose-1-phosphate guanylyltransferase gene (forming O-antigen) (Lee et al., 1992), was absent in Ag2 though there is a manC-like gene in Ag1 showing a significantly low identity (37%). This manC gene is absent in environmental isolate S. marcescens FGI94. An iron transporter gene, shu (Mourer et al., 2015), existed in most of the selected Serratia strains (>87%) while it was absent in those in Ag1 and Ag2 (Table 4).

Table 4.

Prediction of virulence factors in Serratia spp.

| Locus ID | Gene | Predicted gene products | Selected Serratia spp. and their isolation sites* | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mosquitoes | Fly | Nematodes | Fungi | Plants | Milk | Paper | ||||||||

| Ano1 | Ano2 | Ag1 | Ag2 | MCB | Db11 | TEL | FGI94 | Sp | Sl | WW4 | ||||

| FLAGELLA FORMATION | ||||||||||||||

| OHT36767 | flgN | Flagella synthesis | 100 | 100 | 63 | 63 | 98 | 98 | 99 | 67 | 83 | 82 | 98 | |

| OHT36770 | flgB | Basal-body rod protein | 100 | 100 | 82 | 82 | 98 | 98 | 97 | 87 | 89 | 90 | 98 | |

| OHT36762 | flhB | Biosynthetic protein | 100 | 100 | 82 | 82 | 99 | 99 | 99 | 87 | 0 | 93 | 99 | |

| OHT36750 | motA | Motor protein | 100 | 100 | 95 | 95 | 99 | 100 | 99 | 96 | 96 | 98 | 100 | |

| OHT38566 | fleQ | Transcriptional regulator | 100 | 100 | 48 | 48 | 94 | 94 | 48 | 47 | 47 | 49 | 94 | |

| OHT36783 | fliQ | Biosynthetic protein | 100 | 100 | 98 | 98 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 94 | 94 | 95 | 100 | |

| OHT36774 | flgF | Basal-body rod protein | 100 | 100 | 86 | 86 | 99 | 99 | 97 | 88 | 95 | 94 | 97 | |

| OHT36782 | fliR | Biosynthetic protein | 100 | 100 | 84 | 84 | 99 | 99 | 99 | 87 | 93 | 92 | 99 | |

| OHT42321 | tsr | Chemotaxis protein I | 100 | 100 | 56 | 56 | 99 | 99 | 98 | 88 | 92 | 92 | 98 | |

| EXTRACELLULAR CELL STRUCTURES | ||||||||||||||

| LPS | OHT35016 | gluP | L-fucose:H+ symporter permease | 100 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 99 | 99 | 98 | 86 | 91 | 91 | 99 |

| OHT39654 | fabZ | (3R)-hydroxymyristoyl ACP dehydratase | 100 | 100 | 98 | 98 | 100 | 99 | 100 | 98 | 97 | 97 | 99 | |

| LOS | OHT38306 | msbA | Lipid transporter ATP-binding/permease | 100 | 100 | 93 | 93 | 99 | 99 | 99 | 94 | 93 | 94 | 99 |

| OHT32281 | msbB | lipid A biosynthesis | 100 | 100 | 93 | 93 | 100 | 100 | 29 | 94 | 93 | 94 | 100 | |

| OHT38430 | galE | UDP-glucose 4-epimerase | 100 | 100 | 79 | 79 | 77 | 94 | 92 | 74 | 87 | 88 | 94 | |

| OHT38979 | manC | O-antigen synthesis | 100 | 100 | 37 | 0 | 59 | 61 | 60 | 0 | 60 | 59 | 61 | |

| OHT39625 | lpxD | UDP-3-O-(3-hydroxymyristoyl) glucosamine N-acyltransferase | 100 | 100 | 96 | 96 | 99 | 99 | 99 | 95 | 96 | 97 | 99 | |

| OHT41381 | rfaF | ADP-heptose-LPS heptosyltransferase II | 100 | 100 | 90 | 90 | 98 | 98 | 98 | 89 | 91 | 90 | 99 | |

| Fimbriae | OHT32112 | lpfB | Long polar fimbrial chaperone protein LpfB | 100 | 100 | 75 | 75 | 38 | 56 | 99 | 66 | 86 | 42 | 53 |

| OHT35997 | papC | Usher protein PapC | 100 | 100 | 60 | 60 | 75 | 75 | 75 | 73 | 74 | 65 | 81 | |

| IRON METABOLISM | ||||||||||||||

| OHT36555 | entA | 2,3-dihydro-2,3-dihydroxybenzoate dehydrogenase | 100 | 100 | 68 | 68 | 99 | 99 | 100 | 69 | 66 | 67 | 99 | |

| OHT33653 | fepG | Iron-enterobactin ABC transporter permease | 100 | 100 | 64 | 64 | 99 | 99 | 98 | 63 | 63 | 66 | 98 | |

| OHT37918 | fes | Ferric enterobactin esterase | 100 | 100 | 72 | 72 | 98 | 98 | 95 | 78 | 69 | 69 | 99 | |

| OHT35700 | shuU | ABC transport system | 100 | 100 | 39 | 39 | 99 | 99 | 99 | 85 | 95 | 93 | 99 | |

| OHT38589 | fbpC | Iron(III) ABC transporter | 100 | 100 | 87 | 87 | 98 | 98 | 52 | 88 | 93 | 91 | 99 | |

| SECRETION SYSTEM | ||||||||||||||

| OHT38930 | xcpR | T2SS protein E | 100 | 100 | 64 | 64 | 48 | 48 | 94 | 66 | 87 | 47 | 48 | |

| OHT36978 | hsiJ1 | T6SS protein HsiJ1 | 100 | 100 | 80 | 80 | 99 | 99 | 99 | 93 | 0 | 0 | 99 | |

| OHT37058 | mtrD | T3SS protein MtrD | 100 | 100 | 91 | 91 | 99 | 99 | 99 | 90 | 93 | 95 | 99 | |

| REGULATION | ||||||||||||||

| OHT35771 | caf1R | F1 operon positive regulatory protein | 100 | 100 | 74 | 74 | 98 | 98 | 97 | 77 | 81 | 79 | 97 | |

| OHT34240 | pilR | Two-component response regulator | 100 | 100 | 89 | 89 | 98 | 98 | 95 | 87 | 88 | 89 | 95 | |

| OHT36991 | chpD | Transcriptional regulator | 100 | 100 | 81 | 81 | 99 | 99 | 98 | 79 | 85 | 81 | 98 | |

| OHT37846 | fleR/flrC | σ54 response regulator | 100 | 100 | 96 | 96 | 100 | 100 | 99 | 96 | 96 | 96 | 99 | |

| ENZYMES | ||||||||||||||

| OHT42068 | ureA | Urease α subunit | 100 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 95 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| OHT35629 | aprA | alkaline metalloproteinase | 100 | 100 | 59 | 59 | 97 | 97 | 96 | 62 | 61 | 82 | 97 | |

| OTHERS | ||||||||||||||

| OHT35425 | IlpA | Immunogenic lipoprotein A | 100 | 100 | 69 | 69 | 98 | 98 | 98 | 69 | 91 | 97 | 98 | |

| OHT33698 | ccmB | Cytochrome c biogenesis | 100 | 100 | 93 | 93 | 99 | 99 | 99 | 95 | 95 | 94 | 98 | |

| OHT41640 | algU | Alginate biosynthesis protein | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 99 | 100 | 99 | 100 | |

Ano1, S. marcescens ano1; Ano2, S. marcescens ano2; Ag1, Serratia sp. Ag1; Ag2, Serratia sp. Ag2; MCB, S. marcescens MCB; Db11, S. marcescens Db11; TEL, Serratia sp. TEL; FGI94, S. marcescens FGI94; Sp, S. plymuthica S13; Sl, S. liquefaciens ATCC 27592; WW4, S. marcescens WW4. The protein sequences from S. marcescens ano1 were used to blast (blastP) against those in the other selected Serratia species. The gene product is regarded as absence if the identity is below 60%.

Chitinases

At least 4 different chitinase genes encode chitinase A (OHT33328 and OHT32204), chitinase B (OHT36384) and chitinase C (OHT38806) in S. marcescens ano1 (Table 5). ChiA digests chitins from the reducing end while ChiB works on the chitin chain from the non-reducing end, indicating that they are processive enzymes (Suzuki et al., 2002; Orikoshi et al., 2005; Vaaje-Kolstad et al., 2013). Instead, ChiC acts as an endo-acting enzyme which cuts chitin chain in the middle (Vaaje-Kolstad et al., 2013). ChiC exists in most of the selected Serratia. However, an efficient chitin degradation requires a synergistic action of ChiA, ChiB, and ChiC in S. marcescens (Orikoshi et al., 2005; Vaaje-Kolstad et al., 2013). Besides the different catalytic domains (all belonging to GH18 superfamily) (Tian et al., 2014), ChiA1, ChiB and ChiC chitinases have various accessory functional domains (Table 5) such as fibronectin type III (OHT33328), chitin-binding (OHT38806), or cellulose-binding (OHT36384) domains while ChiA2 has only catalytic one (OHT32204) (Tran et al., 2011). Previous studies showed that CBD or chitin-binding domains greatly affected the catalytic activity and substrate affinity in chitinases (Dahiya et al., 2006; Tian et al., 2014). Therefore, the chitinases with various functional domain(s) may provide different physiological roles in S. marcescens (Dahiya et al., 2006). The four chitinase genes dispersedly spread in S. marcescens ano1 genomes, rather than cluster together to form an operon (data not shown). Such arrangement indicates that they may be induced under the different conditions and regulated by different mechanisms. No genes encoding chitinase (cutoff, 60% identity) were found in Serratia sp. Ag1 and Ag2, indicating that they have a poor ability to use chitin as carbon or nitrogen sources from environment or in insects. As expected, in S. marcescens FGI94, a lack of ChiA1 and ChiB as production of large amount of chitinase will disrupt its symbiotic relationship with fungi (by degrading chitins in fungal cell walls; Li P. et al., 2015). Instead, similar to ano1 or ano2, Db1, MCB, and TEL have ChiA1, ChiB, and ChiC. WW4 has the complete chitin degradation enzyme system, which is consistent with its living niche (paper machine) where the plant materials are abundant (Chung et al., 2013).

Table 5.

Comparison of chitinases in selected Serratia spp.

| Chitinases | Mosquitoes | Files | Nematodes | Fingi | Plants | Milk | Paper | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ano1 | Ano2 | Ag1 | Ag2 | MCB | Db11 | TEL | FGI94 | Sp | SL | WW4 | |

|

100 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 99 | 99 | 99 | 0 | 94 | 95 | 99 |

|

100 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 96 | 96 | 28 | 0 | 86 | 84 | 99 |

|

100 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 99 | 99 | 99 | 0 | 94 | 93 | 99 |

|

100 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 98 | 97 | 98 | 83 | 86 | 87 | 99 |

*The left panel shows the organization of the conserved accessory and catalytic domains in various chitinases. The length is not scaled. FN3, fibronectin type III domain. CBD, cellulose-binding domain. ChBD, chitin-binding domain. Ano1, S. marcescens ano1; Ano2, S. marcescens ano2; Ag1, Serratia sp. Ag1; Ag2, Serratia sp. Ag2; MCB, S. marcescens MCB; Db11, S. marcescens Db11; TEL, Serratia sp. TEL; FGI94, S. marcescens FGI94; Sp, S. plymuthica S13; Sl, S. liquefaciens ATCC 27592; WW4, S. marcescens WW4. The protein sequences from S. marcescens ano1 were used to blast (blastP) against those in the other selected Serratia species. The gene product is regarded as absence if the identity is below 60%.

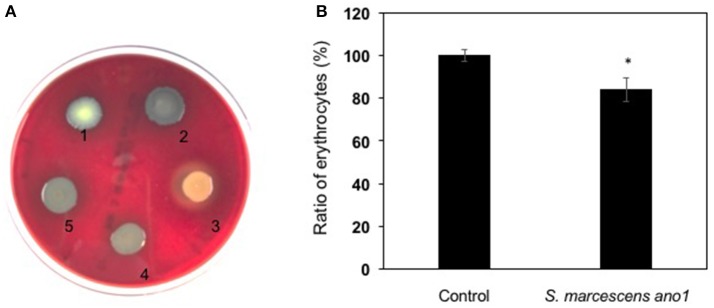

Hemolysins and serralysins

Serratia marcescens ano1 and ano2 were hemolytic strains with alpha-hemolysin activity (Figure 4A). Red blood cell lysis experiment was further conducted by inoculating S. marcescens ano1 in bovine whole cells (Figure 4B). At least 16% of erythrocytes were disrupted within 48 h (Figure 4B). The commensal S. marcescens living in mosquito midgut may not utilize the hemolysin(s) for pathogenesis unless they accidently invade the host through liaison and enter the insect hemolymph (Chen et al. unpublished data).

Figure 4.

Demonstration of alpha-hemolysin production and lysis of erythrocytes by S. marcescens. (A) Demonstration of hemolysin production in S. fonicola MSU001 (colony1), S. marcescens ano1 (colony 2), S.aureus (colony 3, beta-hemolysin control), E. meningoseptica (colony 4, alpha-hemolysin control), and S. marcescens ano1 (colony 5). (B) Lysis of the red blood cells by S. marcescens ano1. The control was the same as the treatment except no bacterial cells were inoculated. The asterisk indicates there was a significant difference between the control and treatment (student t-test, p < 0.01). Values are means of single measurements from triplicate cultures (±standard deviations).

Serralysin genes are present in most of the insect associated Serratia (S. marcescens MCB, S. marcescens Db1 and Serratia sp. TEL) with high identity in amino acid sequences (>60%) (Table 6). S. marcescens ano1 possesses at least 5 genes encoding serralysins or serralysin-like proteins (OHT33392, OHT35629, OHT35861, OHT36525, and OHT38015) (Table 6). It is interesting that Serratia sp. Ag1 and Ag2 have only two of them (Table 6). At least three serralysin genes are found in plant or fungi symbionts S. marcescens, S. plymuthica S13, and S. marcescens FGI94, respectively. In this study, we identified an additional one based on the genome mining method (Table 6).

Table 6.

Comparison of serralysins in selected Serratia spp.*

| Mosquitoes | Flies | Nematodes | Fungi | Plants | Paper | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Serralysin | Ano1 | Ano2 | Ag1 | Ag2 | MCB | Db11 | TEL | FGI94 | Sp | Sl | WW4 |

| OHT33392 | 100 | 100 | 81 | 81 | 98 | 98 | 98 | 81 | 90 | 93 | 97 |

| OHT38015 | 100 | 100 | 61 | 61 | 63 | 63 | 63 | 61 | 71 | 74 | 95 |

| OHT35629 | 100 | 100 | 59 | 59 | 97 | 97 | 96 | 62 | 61 | 82 | 97 |

| OHT36525 | 100 | 100 | 53 | 53 | 92 | 95 | 95 | 53 | 53 | 53 | 95 |

| OHT35861 | 100 | 100 | 48 | 48 | 99 | 99 | 98 | 49 | 46 | 78 | 99 |

Ano1, S. marcescens ano1; Ano2, S. marcescens ano2; Ag1, Serratia sp. Ag1; Ag2, Serratia sp. Ag2; MCB, S. marcescens MCB; Db11, S. marcescens Db11; TEL, Serratia sp. TEL; FGI94, S. marcescens FGI94; Sp, S. plymuthica S13; Sl, S. liquefaciens ATCC 27592; WW4, S. marcescens WW4. The protein sequences from S. marcescens ano1were used to blast (blastP) against those in the other selected Serratia species. The gene product is regarded as absence if the identity is below 60%.

Ureases

ureA, encoding an α-subunit ureases, was predicted as the virulence factor (Table 3). Among the selected Serratia, only ano1, ano2 and TEL carry ureA (Table 3). Further examination of the three selected Serratia genomes showed that there is an operon consisting of 9 genes possibly involved in urea metabolism (Figure S5). Serratia marcescens strain ano1 was confirmed to urease production positive (data not shown), indicating that the “ure” operon is functional in ano1. In this “ure” operon, three genes (ure A, B, and C) were predicted to encode α, β, and γ subunits, respectively (Carlini and Ligabue-Braun, 2016). Genes ure D, E, F, and G encode urease accessory proteins that participate in assembly and activation of ureases (Carlini and Ligabue-Braun, 2016). Additionally, urea transporter (utp) and nickel transporter (nixA) genes immediately locate downstream of urease structure protein or accessory protein encoding genes (Carlini and Ligabue-Braun, 2016). However, the ure operon is only found in 14 out of 101 Serratia genomes publically available in the IMG/MER (cutoff date, Dec.1, 2016). We found mosquito or nematode-associated Serratia (ano1, ano2, TEL) with this operon.

Iron and heme metabolism

Enterobactin synthesis gene clusters and their organization were conserved in all S. marcescens genomes (Table 7). Several operons encoding ferrichrome ABC transporters (fhu operon), ferric siderophore ABC transporters (fep operon) and ferric citrate outer membrane transporters (fec operon) were found (Table 7). Serratia marcescens ano1 and ano2 had a delicate set of heme uptake/storage systems (Table 7). The has operon encoding the heme uptake system includes an RNA polymerase sigma factor (OHT42022.1), putative iron sensor protein (OHT42023.1), TonB-dependent heme receptor (OHT42024.1), hemophore HasA (OHT42025.1), peptidase (OHT42071.1), hemolysin transporter (OHT42026.1), and TonB-like protein (OHT42027.1). This system ensures that, after heme/hemin is released from hemoglobins or other iron containing proteins, they can be efficiently processed, stored and transported. The ferric uptake regulator (Müller et al., 2013) has a key role in modulating iron uptake, and the genome of S. marcescens strain ano1 and ano2 is predicted to encode a Fur protein (OHT38796.1). However, the fur gene is not close to any iron metabolism genes in S. marcescens (data not shown).

Table 7.

Iron metabolism genes in selected Serratia spp.*

| Iron-utilization system | Genes | Predicted gene products | Ano1 | Ano2 | Db11 | FGI94 | Sp | TEL | MCB | Ag1 | Ag2 | Sl | WW4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The ent operon and entA- and entD-homologs | |||||||||||||

| entFSCEB | Enterobactin synthase subunit F, enterobactin exporter, isochorismate synthase,enterobactin synthase subunit E & isochorismatase | 100 | 100 | 99 | 84 | 82 | 97 | 99 | 81 | 81 | 83 | 98 | |

| 100 | 100 | 99 | 54 | 59 | 99 | 99 | 59 | 59 | 59 | 99 | |||

| pswP | Putative 4'-phosphopantetheinyl transferase (entD homolog) | 100 | 100 | 94 | 54 | 80 | 94 | 96 | 64 | 64 | 77 | 91 | |

| A gene cluster for siderophore synthesis | |||||||||||||

| Predicted transporter, siderophore synthetase CbsF homolog, putative siderophore biosynthesis protein & ferric siderophore esterase | 100 | 100 | 100 | 94 | 57 | 100 | 100 | 60 | 60 | 57 | 99 | ||

| The fhu operon | |||||||||||||

| fhuBDC | Ferrichrome ABC transporter (permease, substrate-binding & ATP-binding proteins) | 100 | 100 | 94 | 72 | 82 | 96 | 96 | 0 | 0 | 84 | 93 | |

| fhuA | Ferrichrome outer membrane transporter | 100 | 100 | 96 | 56 | 73 | 93 | 96 | 0 | 0 | 75 | 94 | |

| The fep operon | |||||||||||||

| fepBDGC | Ferric siderophore ABC transporter (substrate-binding, permease, & ATP-binding proteins) | 100 | 100 | 94 | 64 | 61 | 99 | 94 | 54 | 54 | 53 | 96 | |

| The fec operon | |||||||||||||

| fecARI | Ferric citrate outer membrane transporter, transmembrane signal transducer & RNA polymerase sigma factor | 100 | 100 | 91 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 93 | 0 | 0 | 67 | 94 | |

| The has operon | |||||||||||||

| hasIERADEB | RNA polymerase sigma factor, putative iron sensor protein, TonB-dependent heme receptor, hemophore HasA, heme acquisition ABC transporter (ATPbinding/permease & substrate-binding proteins) & TonB-like protein | 100 | 100 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 99 | |

| The hem operon | |||||||||||||

| hemVUTSR | Hemin ABC transporter (ATP-binding, permease, & substrate-binding proteins), hemindegrading protein & TonB-dependent hemin receptor | 100 | 100 | 99 | 81 | 81 | 83 | 97 | 55 | 55 | 83 | 100 | |

| hemP | Hemin uptake protein | 100 | 100 | 97 | 89 | 87 | 87 | 97 | 0 | 0 | 87 | 100 | |

| The hms operon | |||||||||||||

| hmsSRFH | Hemin storage system (HmsS, HmsR, HmsF, & HmsH proteins) | 100 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 | |

Ano1, S. marcescens ano1; Ano2, S. marcescens ano2; Ag1, Serratia sp. Ag1; Ag2, Serratia sp. Ag2; MCB, S. marcescens MCB; Db11, S. marcescens Db11; TEL, Serratia sp. TEL; FGI94, S. marcescens FGI94; Sp, S. plymuthica S13; Sl, S. liquefaciens ATCC 27592; WW4, S. marcescens WW4. The protein sequences from S. marcescens ano1 were used to blast (blastP) against those in the other selected Serratia species. The gene product is regarded as absence if the identity is below 60%.

Discussion

We report here that mosquito-commensal S. marcescens bacteria have many genes encoding various virulence factors such as flagella formation, lipooligosaccharide (LOS), iron uptake and transportation, serralysins, hemolysins, and chitinases, indicating that they have great potential to disrupt the development of malaria parasites through different avenues (Lazaro et al., 2002; Gonzalez-Ceron et al., 2003; Azambuja et al., 2005; Bahia et al., 2014). Regardless of the mechanisms, the ability to colonize the midgut and persist over time must precede any anti-parasite activity (Bahia et al., 2014). By using S. marcescens ano1 as a representative bacterium to study the interaction between gut bacteria and mosquito, we further demonstrated commensal isolate S. marcescens ano1 was able to successfully re-colonize and transstadially persist in the A. stephensi mosquito gut. This bacterium can be introduced alone or in combination with other microbes such as E. anophelis as a commensal cocktail without substantial inhibition of the members of the consortium, as shown in the bacteria-bacteria interaction experiment (Table 1). Moreover, this isolate was amenable to genetic manipulation (exemplified by expression of reporter genes), opening the possibility to utilize S. marcescens for paratransgenic vector control. These properties are extremely important for developing paratransgenic reagents in control of malaria parasite transmission and understanding the bacterial interactions with other gut symbionts as well as the host mosquito.

Biofilm formation is important for establishing microbe-insect symbiosis (Kim et al., 2014). Serratia marcescens and E. anophelis had better capability to infect and colonize A. stephensi than did S. fonticola (Table 1). We speculate that adherence and biofilm formation characteristics in S. marcescens and E. anophelis possibly contribute to their successful colonization in A. stephensi. In vitro studies showed that biofilm production in S. marcescens was two times higher than that in S. fonticola (Hamieh et al., 2015). Previous results showed that some specific genes in commensals modulated the biofilm growth and thus facilitated the bacteria-insect symbiosis (Kim et al., 2014; Powell et al., 2016). Biofilms in S. marcescens are tightly controlled by a set of sophisticated system including quorum sensing, type 1 fimbriae, and carbon and nitrogen sources (Labbate et al., 2007; Shanks et al., 2007). Shanks et al. (2007) reported that disruption of type I fimbrial genes in S. marcescens resulted in severe deficiencies in biofilm formation (Shanks et al., 2007). In the same study, their results showed that biofilm formation was remarkably affected by a mutation of oxyR, a transcription factor participating in regulate oxidative stress response (Shanks et al., 2007). Moreover, the bacterial biofilm formation in insect midgut was greatly influenced by gut environment that is frequently changed with the host developmental stages and diet types (Wang et al., 2011; Chen et al., 2016). Our results and others also showed that blood meals dramatically influenced the composition of microbial community, demonstrating that the bacterial ability to respond to the dramatic stress determines their survival in mosquito gut (Wang et al., 2011; Chen et al., 2016). Li et al. reported that the addition of hemoglobin enhanced the attachment of E. anophelis to the substratum of the matrix and biofilm biovolume rather than iron (Li Y. et al., 2015). Further, our preliminary data showed that transposon-mediated mutation of a Bacteriodes aerotolerance (Bat) protein gene in E. anophelis resulted in a low biofilm formation and also inability to colonize A. stephensi (Chen et al. unpublished data). However, it remains unclear if there are different gene determinations for biofilm formation in our A. triseriatus-isolate S. fonticola MSU001 due to the lack of the genome sequences. Future comparative genomic and functional analysis among S. marcescens ano1, S. fonticola MSU001, and E. anophelis MSU001 will provide better insights into the molecular mechanisms involving in bacterial biofilm formation and colonization.

Bacterial shift from one host to another will encounter the different stressors. To successfully colonize the mosquito host gut, microbes should circumvent: (1) digestion and destructive factors such as secreted lysozyme, antibacterial peptides, and other immune factors from the host; (2) inhibition effects from other microbes (e.g., antibiotics); and (3) stressors such as nutrient limitation and high pH in the mosquito gut. Previous studies showed that gut microbes such as S. marcescens and Elizabethkingia could tolerate high pH and/or resist digestion (Chen et al., 2015, 2016). Coexistence with predominant bacteria showed that Serratia may evolve to cooperate their activity in a niche such as mosquito midgut. Unfortunately, the detailed molecular mechanisms involved in bacterial survival in mosquito hosts are poorly investigated (Dillon and Dillon, 2004; Bahia et al., 2014). Particularly, genomic, physiological and systematic characterization of commensal bacteria such as S. marcescens isolated from mosquitoes has been understudied (Pei et al., 2015). However, the study on bacterial interspecies competition demonstrated that S. marcescens could inhibited the growth of Sphingomonas and Burkholderiaceae members (Labbate et al., 2007). Competitive colonization was previously reported in the desert locust Schistocerca gregaria where bacterial diversity was shown to increase in the absence of S. marcescens (Dillon and Charnley, 2002). In vitro studies showed that extracts from E. meningoseptica had the antimicrobial properties, actively repressing gram-positive and negative bacteria and yeast (Ngwa et al., 2013). Our previous studies also showed E. anophelis survived in and consecutively associated with A. stephensi and A. gambiae mosquitoes rather than A. triseriatus (Chen et al., 2015). Further, we demonstrated that E. anophelis was more resistant to the digestion by A. stephensi and A. gambiae mosquitoes than by A. triseriatus, indicating that the bacterial ability to adapt in the gut environment is critical for persistence (Chen et al., 2015). Poor persistence of S. fonticola MSU001 in A. stephensi remains unexplored but it may be explained by its intolerance of the stress in the new host gut. Additional analyses are warranted to better understand the degree of interactions among the gut microbiota.

Mosquito-associated S. marcescens show distinctly different features from those isolated from environmental (free-living) or clinical settings (Lauzon et al., 2003; Iguchi et al., 2014; Lephoto and Gray, 2015). For example, our findings show that S. marcescens ano1 and ano2 lack genes encoding prodigiosins which are typically produced by many Serratia spp. and Enterobacter spp. (Williamson et al., 2006). Prodigiosins induced fragmentation of DNA, causing apoptosis in infected cells (Montaner et al., 2000). Prodigiosins were toxic to P. falciparum (Lazaro et al., 2002) and T. cruzi (Azambuja et al., 2004) and lethal to host mosquitoes (Patil et al., 2011; Suryawanshi et al., 2015). Absence of prodigiosins in mosquito-associated Serratia is consistent with their commensal life style. Moreover, another remarkable characteristic of commensal S. marcescens ano1 is production of urease with a complete urease gene cassette. By contrast, clinically important Serratia isolates are typically urease-negative. Urease, a nickel-containing metalloenzyme, catalyzes the hydrolysis reaction of urea and converts it to carbon dioxide and ammonia (Burne and Chen, 2000). In the mosquito or nematode native habitats (e.g., rice fields or soils), a high concentration of urea occurs after nitrogen fertilization (Victor and Reuben, 2000). Further, urease-producing, mosquito-associated Serratia possibly utilize available urea and arginine released from ingested animal erythrocytes as the nitrogen source for growth; consequently, the metabolites (such as ammonia) may contribute to regulate pH in the mosquito gut (Linser et al., 2009). On the other hand, some microbial ureases have insecticidal or fungal-toxic activity (Stanisçuaski et al., 2005; Becker-Ritt et al., 2007). This mode of toxicity relies on an internal peptide released upon proteolysis of ingested urease by insect digestive enzymes (Stanisçuaski et al., 2005). The intact protein and its derived peptide(s) are neurotoxic to insects or eukaryotic parasites and affect a number of other physiological functions such as diuresis, muscle contraction and immunity status (Stanisçuaski et al., 2005). Microbial ureases are fungitoxic to filamentous fungi and yeasts through a mechanism involving cell membrane permeabilization (Becker-Ritt et al., 2007).

Serratia marcescens ano1 has a sophisticated chitin digestion system that may facilitate depolymerization of chitin ingested with detritus by larval mosquitoes. Thus, Serratia may directly obtain nutrients from chitin degradation products, which may provide a labile carbon source to mosquito hosts (Vaaje-Kolstad et al., 2013). Furthermore, addition of chitotriose (intermediate chitin degradation products) into blood meal completely abolished P. vivax infectivity in Anopheles tessellatus. Chitotriose blocked the ookinete binding sites (GlcNAc residues) present in glycoproteins of the epithelium in gut. Moreover, chitinase secreted by S. marcescens could degrade the chitin structure on the gut lumen surface of insects (Hamilton et al., 2014), destroying the parasites' binding sites. However, more studies are warranted to elucidate if S. marcescens blocks malaria parasites' infection in mosquitoes through the chitinase production pathway.

Serratia marcescens secreted hemolysin which lysed animal erythrocytes in the blood meal; this facilitated acquisition of nutrients from the blood meal for the bacterial commensals and the mosquito host simultaneously (Gaio Ade et al., 2011). Removal of Serratia and/or other commensal bacteria caused reduced egg production, indicating that Serratia contributes to mosquito fecundity (Azambuja et al., 2004; Gaio Ade et al., 2011). Hemolysins in Serratia or Serratia-like bacteria had some different characteristics from the typical ones described previously (Ralf, 2005; Peraro and van der Goot, 2016). The hemolysin ShlA (OHT39701.1) in S. marcescens was secreted through and next activated by ShlB (OHT39702.1) which was a component of the two partner secretion system (TPSS, type V-secretion system) (Pramanik et al., 2014). After being processed, active format of secreted ShlA bond to erythrocytes and led to cell lysis by pore formation (Di Venanzio et al., 2014; Pramanik et al., 2014). In S. marcescens, genes shlA and shlB were tandemly organized and transcriptionally regulated by RcsB (Di Venanzio et al., 2014). The expression of shlA was induced under the low iron condition and low temperature. Furthermore, ShlA was also shown to have additional functions, such as promoting vacuolization and apoptosis in host. Besides blood cells, hemolysins damage epithelial barriers, thus promoting bacterial invasion and dissemination (Nagamatsu et al., 2015; Ristow and Welch, 2016). Direct contact between S. marcescens Db11 and infected C. elegans was required for killing effect, indicating that the function of hemolysins synergized other components in S. marcescens Db11 for pathogenicity (Kurz and Ewbank, 2000; Kurz et al., 2003). Moreover, hemolysins attacked various immune cells as an immune evasion strategy (Smith et al., 2015).

Serralysins, belonging to a conserved metalloprotease superfamily, degrade various host defense proteins such as immunoglobulins, antimicrobial peptides (defensin), complement proteins, as well as some structural proteins with barrier functions (Potempa and Pike, 2009; Ishii et al., 2014). Serratia marcescens PIC3611 had at least 4 experimentally-verified serralysins (i.e., PrtS, SlpB, SlpC, and SlpD; Shanks et al., 2015). Expression of prtS alone was sufficient for cytotoxicity of a corneal cell line (Shanks et al., 2015). However, various serralysins may have differential cytotoxicity, depending on the host cell type(s) (Ishii et al., 2014; Shanks et al., 2015). Serralysins in entomopathogenic S. marcescens notably increased the release of phagocytic hemocytes into silkworm hemolymph but it was not lethal to the moths (Ishii et al., 2014). Hemolymph invasion of S. marcescens Ss1 suppressed the immune response in honey bees, which led to fast bacterial growth in the bees (Burritt et al., 2016). The bacterial propagation in the hemolymph possibly caused permeabilization of organ membranes, resulting in leakage of circulatory and digestive contents into the hemolymph (Burritt et al., 2016).

Microbiota in the female mosquito may encounter two distinct iron-stressing circumstances, depending on the available food types (i.e., sugar or blood meal). When plant nectar is ingested, iron is very limited in the mosquito gut (Gonzales and Hansen, 2016). A sudden, high concentration of iron/heme will be available in the midgut when erythrocytes are ingested and digested by female mosquitoes (Benoit et al., 2011). Under the first scenario, gut microbiota need to scavenge iron either from the insect host or other microbes. Serratia marcescens may secrete enterobactin to acquire iron (Angerer et al., 1992). Collectively, our discovery of the heme uptake, transportation and storage gene clusters agree with previous reports of iron acquisition by S. marcescens (Angerer et al., 1992) and with the consistent presence and persistence of Serratia in mosquitoes. Enterobactin chelates a very low concentration of environmental ferric ion (Fe3+) at extremely high affinity (greater than EDTA) and delivers the soluble iron to the bacteria. Chelated and/or free forms of iron from the environment can be transported into bacterial cells through different iron transportation systems. It is very important for Serratia to produce siderophores with high iron affinity and have diverse iron transporters, which allows them to compete other microbiota under very limited iron in mosquito gut. On the other hand, the free radicals and oxidative molecules caused by high titers of heme or iron are harmful for some midgut bacteria after blood cells being lysed (Graça-Souza et al., 2006). Bacteria surviving in such environments are expected to have a capability to deal with these high iron stressing condition (Graça-Souza et al., 2006).

Author contributions

SC and EW conceived the study and participated in its design and coordination. SC performed the experiments, whole genome sequencing, annotation, and comparative analysis. JB contributed to the genome analysis. SC and EW wrote the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This project was funded by NIH grant R37AI21884.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fmicb.2017.01483/full#supplementary-material

References

- Abebe E., Akele F.-A., Morrison J., Cooper V., Thomas W. K. (2011). An insect pathogenic symbiosis between a Caenorhabditis and Serratia. Virulence 2, 158–161. 10.4161/viru.2.2.15337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abebe-Akele F., Tisa L. S., Cooper V. S., Hatcher P. J., Abebe E., Thomas W. K. (2015). Genome sequence and comparative analysis of a putative entomopathogenic Serratia isolated from Caenorhabditis briggsae. BMC Genomics 16:531 10.1186/s12864-015-1697-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aggarwal C., Paul S., Tripathi V., Paul B., Khan M. A. (2015). Chitinolytic activity in Serratia marcescens (strain SEN) and potency against different larval instars of Spodoptera litura with effect of sublethal doses on insect development. BioControl 60, 631–640. 10.1007/s10526-015-9674-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Angerer A., Klupp B., Braun V. (1992). Iron transport systems of Serratia marcescens. J. Bacteriol. 174, 1378–1387. 10.1128/jb.174.4.1378-1387.1992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azambuja P., Feder D., Garcia E. S. (2004). Isolation of Serratia marcescens in the midgut of Rhodnius prolixus: impact on the establishment of the parasite Trypanosoma cruzi in the vector. Exp. Parasitol. 107, 89–96. 10.1016/j.exppara.2004.04.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azambuja P., Garcia E. S., Ratcliffe N. A. (2005). Gut microbiota and parasite transmission by insect vectors. Trends Parasitol. 21, 568–572. 10.1016/j.pt.2005.09.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahia A. C., Dong Y., Blumberg B. J., Mlambo G., Tripathi A., BenMarzouk-Hidalgo O. J., et al. (2014). Exploring Anopheles gut bacteria for Plasmodium blocking activity. Environ. Microbiol. 16, 2980–2994. 10.1111/1462-2920.12381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bando H., Okado K., Guelbeogo W. M., Badolo A., Aonuma H., Nelson B., et al. (2013). Intra-specific diversity of Serratia marcescens in Anopheles mosquito midgut defines Plasmodium transmission capacity. Sci. Rep. 3:1641. 10.1038/srep01641 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bankevich A., Nurk S., Antipov D., Gurevich A. A., Dvorkin M., Kulikov A. S., et al. (2012). SPAdes: a new genome assembly algorithm and its applications to single-cell sequencing. J. Comput. Biol. 19, 455–477. 10.1089/cmb.2012.0021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker-Ritt A. B., Martinelli A. H. S., Mitidieri S., Feder V., Wassermann G. E., Santi L., et al. (2007). Antifungal activity of plant and bacterial ureases. Toxicon 50, 971–983. 10.1016/j.toxicon.2007.07.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benoit J. B., Lopez-Martinez G., Patrick K. R., Phillips Z. P., Krause T. B., Denlinger D. L. (2011). Drinking a hot blood meal elicits a protective heat shock response in mosquitoes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 8026–8029. 10.1073/pnas.1105195108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benoit T. G., Wilson G. R., Pryor N., Bull D. L. (1990). Isolation and pathogenicity of Serratia marcescens from adult house flies infected with Entomophthora muscae. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 55, 142–144. 10.1016/0022-2011(90)90047-A [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blom J., Kreis J., Spänig S., Juhre T., Bertelli C., Ernst C., et al. (2016). EDGAR 2.0: an enhanced software platform for comparative gene content analyses. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, W22–W28. 10.1093/nar/gkw255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burne R. A., Chen Y.-Y. M. (2000). Bacterial ureases in infectious diseases. Microb. Infect. 2, 533–542. 10.1016/S1286-4579(00)00312-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burritt N. L., Foss N. J., Neeno-Eckwall E. C., Church J. O., Hilger A. M., Hildebrand J. A., et al. (2016). Sepsis and hemocyte loss in honey bees (Apis mellifera) infected with Serratia marcescens strain sicaria. PLoS ONE 11:e0167752. 10.1371/journal.pone.0167752 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlini C. R., Ligabue-Braun R. (2016). Ureases as multifunctional toxic proteins: a review. Toxicon 110, 90–109. 10.1016/j.toxicon.2015.11.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S., Bagdasarian M., Walker E. D. (2015). Elizabethkingia anophelis: molecular manipulation and interactions with mosquito hosts. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 81, 2233–2243. 10.1128/AEM.03733-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S., Hickey W. J. (2011). Development of tools for genetic analysis of phenanthrene degradation and nanopod production by Delftia sp. Cs1-4. Front. Microbiol. 2:187. 10.3389/fmicb.2011.00187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S., Kaufman M. G., Korir M. L., Walker E. D. (2014). Ingestibility, digestibility, and engineered biological control potential of Flavobacterium hibernum, isolated from larval mosquito habitats. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 80, 1150–1158. 10.1128/AEM.03319-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S., Zhao J., Joshi D., Xi Z., Norman B., Walker E. D. (2016). Persistent infection by Wolbachia wAlbB has no effect on composition of the gut microbiota in adult female Anopheles stephensi. Front. Microbiol. 7:1485. 10.3389/fmicb.2016.01485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung W.-C., Chen L.-L., Lo W.-S., Kuo P.-A., Tu J., Kuo C.-H. (2013). Complete genome sequence of Serratia marcescens WW4. Genome Announc. 1:e00126–e00113. 10.1128/genomeA.00126-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosentino S., Voldby Larsen M., Møller Aarestrup F., Lund O. (2013). PathogenFinder-distinguishing friend from foe using bacterial whole genome sequence data. PLoS ONE 8:e77302. 10.1371/journal.pone.0077302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahiya N., Tewari R., Hoondal G. S. (2006). Biotechnological aspects of chitinolytic enzymes: a review. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 71, 773–782. 10.1007/s00253-005-0183-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dillon R., Charnley K. (2002). Mutualism between the desert locust Schistocerca gregaria and its gut microbiota. Res. Microbiol. 153, 503–509. 10.1016/S0923-2508(02)01361-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dillon R., Dillon V. (2004). The gut bacteria of insects: nonpathogenic interactions. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 49, 71–92. 10.1146/annurev.ento.49.061802.123416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Venanzio G., Stepanenko T. M., García Véscovi E. (2014). Serratia marcescens ShlA pore-forming toxin is responsible for early induction of autophagy in host cells and is transcriptionally regulated by rcsB. Infect. Immun. 82, 3542–3554. 10.1128/IAI.01682-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar R. C. (2004). MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res. 32, 1792–1797. 10.1093/nar/gkh340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- European Committee for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing of the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases (2003). Determination of minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) of antibacterial agents by broth dilution. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 9, ix–xv. 10.1046/j.1469-0691.2003.00790.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Felsenstein J. (1989). PHYLIP - Phylogeny Inference Package (Version 3.2). Cladistics 5, 164–166. [Google Scholar]

- Flyg C., Kenne K., Boman H. G. (1980). Insect pathogenic properties of Serratia marcescens: phage-resistant mutants with a decreased resistance to cecropia immunity and a decreased virulence to drosophila. Microbiology 120, 173–181. 10.1099/00221287-120-1-173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaio Ade O., Gusmão D. S., Santos A. V., Berbert-Molina M. A., Pimenta P. F., Lemos F. J. (2011). Contribution of midgut bacteria to blood digestion and egg production in Aedes aegypti (diptera: culicidae) (L.). Parasit. Vectors 4:105. 10.1186/1756-3305-4-105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales K. K., Hansen I. A. (2016). Artificial Diets for Mosquitoes. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 13:1267 10.3390/ijerph13121267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Ceron L., Santillan F., Rodriguez M. H., Mendez D., Hernandez-Avila J. E. (2003). Bacteria in midguts of field-collected Anopheles albimanus block Plasmodium vivax sporogonic development. J. Med. Entomol. 40, 371–374. 10.1603/0022-2585-40.3.371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graça-Souza A. V., Maya-Monteiro C., Paiva-Silva G. O., Braz G. R. C., Paes M. C., Sorgine M. H. F., et al. (2006). Adaptations against heme toxicity in blood-feeding arthropods. Insect. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 36, 322–335. 10.1016/j.ibmb.2006.01.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimont F., Grimont P. A. D. (2006). The genus Serratia, in The Prokaryotes: Volume 6: Proteobacteria: Gamma Subclass, eds Dworkin M., Falkow S., Rosenberg E., Schleifer K.-H., Stackebrandt E. (New York, NY: Springer; ), 219–244. [Google Scholar]

- Grissa I., Vergnaud G., Pourcel C. (2007). CRISPRFinder: a web tool to identify clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats. Nucleic Acids Res. 35, W52–W57. 10.1093/nar/gkm360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamieh A., Olama Z., Khawaja G., Holail H. (2015). Bacterial diversity and biofilm formation in drinking water distribution system in Lebanon. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. App. Sci. 4, 976–990. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton J. J., Marlow V. L., Owen R. A., Costa Md A. A., Guo M., Buchanan G., et al. (2014). A holin and an endopeptidase are essential for chitinolytic protein secretion in Serratia marcescens. J. Cell Biol. 207, 615–626. 10.1083/jcb.201404127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iguchi A., Nagaya Y., Pradel E., Ooka T., Ogura Y., Katsura K., et al. (2014). Genome evolution and plasticity of Serratia marcescens, an important multidrug-resistant nosocomial pathogen. Genome Biol. Evol. 6, 2096–2110. 10.1093/gbe/evu160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishii K., Adachi T., Hamamoto H., Sekimizu K. (2014). Serratia marcescens suppresses host cellular immunity via the production of an adhesion-inhibitory factor against immunosurveillance cells. J. Biol. Chem. 289, 5876–5888. 10.1074/jbc.M113.544536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J. K., Kwon J. Y., Kim S. K., Han S. H., Won Y. J., Lee J. H., et al. (2014). Purine biosynthesis, biofilm formation, and persistence of an insect-microbe gut symbiosis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 80, 4374–4382. 10.1128/AEM.00739-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurz C. L., Chauvet S., Andrès E., Aurouze M., Vallet I., Michel G. P., et al. (2003). Virulence factors of the human opportunistic pathogen Serratia marcescens identified by in vivo screening. EMBO J. 22, 1451–1460. 10.1093/emboj/cdg159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurz C. L., Ewbank J. J. (2000). Caenorhabditis elegans for the study of host-pathogen interactions. Trends Microbiol. 8, 142–144. 10.1016/S0966-842X(99)01691-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labbate M., Zhu H., Thung L., Bandara R., Larsen M. R., Willcox M. D. P., et al. (2007). Quorum-sensing regulation of adhesion in Serratia marcescens MG1 is surface dependent. J. Bacteriol. 189, 2702–2711. 10.1128/JB.01582-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauzon C., Bussert T., Sjogren R., Prokopy R. (2003). Serratia marcescens as a bacterial pathogen of Rhagoletis pomonella flies (Diptera: Tephritidae). EJE 100, 87–92. 10.14411/eje.2003.017 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lazaro J. E., Nitcheu J., Predicala R. Z., Mangalindan G. C., Nesslany F., Marzin D., et al. (2002). Heptyl prodigiosin, a bacterial metabolite, is antimalarial in vivo and non-mutagenic in vitro. J. Nat. Toxins 11, 367–377. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S. J., Romana L. K., Reeves P. R. (1992). Sequence and structural analysis of the rfb (O antigen) gene cluster from a group C1 Salmonella enterica strain. Microbiology 138, 1843–1855. 10.1099/00221287-138-9-1843 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lephoto T. E., Gray V. M. (2015). Genome sequencing and annotation of Serratia sp. strain TEL. Genomics Data 6, 54–56. 10.1016/j.gdata.2015.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li P., Kwok A. H. Y., Jiang J., Ran T., Xu D., Wang W., et al. (2015). Comparative genome analyses of Serratia marcescens FS14 reveals its high antagonistic potential. PLoS ONE 10:e0123061. 10.1371/journal.pone.0123061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Liu Y., Chew S. C., Tay M., Salido M. M. S., Teo J., et al. (2015). Complete genome sequence and transcriptomic analysis of the novel pathogen Elizabethkingia anophelis in response to oxidative stress. Genome Biol. Evol. 7, 1676–1685. 10.1093/gbe/evv101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linser P. J., Smith K. E., Seron T. J., Neira Oviedo M. (2009). Carbonic anhydrases and anion transport in mosquito midgut pH regulation. J. Exp. Biol. 212, 1662–1671. 10.1242/jeb.028084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McArthur A. G., Waglechner N., Nizam F., Yan A., Azad M. A., Baylay A. J., et al. (2013). The comprehensive antibiotic resistance database. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 57, 3348–3357. 10.1128/AAC.00419-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montaner B., Navarro S., Piqué M., Vilaseca M., Martinell M., Giralt E., et al. (2000). Prodigiosin from the supernatant of Serratia marcescens induces apoptosis in haematopoietic cancer cell lines. Br. J. Pharmacol. 131, 585–593. 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mourer T., Jacques J.-F., Brault A., Bisaillon M., Labbé S. (2015). Shu1 is a cell-surface protein involved in iron acquisition from heme in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. J. Biol. Chem. 290, 10176–10190. 10.1074/jbc.M115.642058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]