Abstract

AIM

To assess the vitamin D (VD) deficiency as a prognostic factor and effect of replenishment of VD on mortality in decompensated cirrhosis.

METHODS

Patients with decompensated liver cirrhosis were screened for serum VD levels. A total of 101 VD deficient patients (< 20 ng/mL) were randomly enrolled in two groups: Treatment group (n = 51) and control group (n = 50). Treatment group received VD treatment in the form of intramuscular cholecalciferol 300000 IU as loading dose and 800 IU/d oral as maintenance dose along with 1000 mg oral calcium supplementation. The VD level, clinical parameters and survival of both the groups were compared for 6-mo.

RESULTS

Prevalence of vitamin D deficiency (VDD) in decompensated CLD was 84.31%. The mean (SD) age of the patients in the treatment group (M:F: 40:11) and control group (M:F: 37:13) were 46.2 (± 14.93) years and 43.28 (± 12.53) years, respectively. Baseline mean (CI) VD (ng/mL) in control group and treatment group were 9.15 (8.35-9.94) and 9.65 (8.63-10.7), respectively. Mean (CI) serum VD level (ng/mL) at 6-mo in control group and treatment group were 9.02 (6.88-11.17) and 29 (23-35), respectively. Over the period of time the VD, calcium and phosphorus level was improved in treatment group compared to control group. There was non-significant trend seen in greater survival (69% vs 64%; P > 0.05) and longer survival (155 d vs 141 d; P > 0.05) in treatment group compared to control group. VD level had no significant association with mortality (P > 0.05). In multivariate analysis, treatment with VD supplement was found significantly (P < 0.05; adjusted hazard ratio: 0.48) associated with survival of the patients over 6-mo.

CONCLUSION

VD deficiency is very common in patients of decompensated CLD. Replenishment of VD may improve survival in patients with decompensated liver cirrhosis.

Keywords: Chronic liver diseases, Vitamin D, Vitamin D deficiency, Decompensated liver cirrhosis, Survival

Core tip: This was a prospective study to assess the vitamin D (VD) deficiency as a prognostic factor for survival in patients with decompensated chronic liver diseases (n = 101) and effect of replenishment of VD on all-cause mortality in decompensated liver cirrhosis. Treatment with VD supplement was found associated with survival of the patients over 6-mo. Replenishment of VD along with calcium supplementation may improve survival in patients with decompensated cirrhosis. These findings need to be confirmed in larger multicenter studies.

INTRODUCTION

Vitamin D (VD) is widely known as a regulator of calcium and bone metabolism. Deficiency of VD, a secosteroid causes rickets in children and osteomalacia in adults. Role of VD is not limited to bone mineral metabolism. It has pleiotropic effects including cellular proliferation and differentiation[1]. It has important role in activation of lymphocytes and immunomodulation. The role of VD in the activation and regulation of both innate and adaptive immune systems has been described[2]. There are reports suggesting VD also has anti-inflammatory and anti-fibrotic properties. These functions have been implicated in the pathogenesis and treatment of infections, autoimmune, cardiovascular, and degenerative diseases and several types of cancer[1-5].

Worldwide, hepatic cirrhosis is a common cause of mortality and morbidity. Liver plays important role in conversion of inactive VD into active 25-hydroxy VD (25-OH VD)[6]. Vitamin D deficiency (VDD) is very common in patients of chronic liver diseases (CLD). VDD is well described in cholestatic liver diseases. However, the role of VDD in the natural history of noncholestatic CLD is not well described[7]. The data regarding the association of VDD with complications and prognosis in patients of CLD are scarce and heterogeneous[8-10]. There are few reports are available regarding the effect of VD supplementation on the natural history of VD deficient people, especially patients with decompensated CLD[11-14]. Effect of VD supplementation to prevent mortality in VD deficient patients with decompansated CLD is not known. The aims of this study were to assess the VD levels in a cohort of patients with decompensated liver cirrhosis and effect of VD replenishment on all-cause mortality in patient with VD deficient decompensated cirrhosis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This study was a single centre prospective study conducted in the Department of Gastroenterology in a tertiary care center of Eastern India over the period of 2-year. All patients provided a written informed consent before enrolment. For patients with altered sensorium, an informed consent was obtained from the next of kin. The study was approved by the institute’s ethical review committee.

Inclusion criteria: Decompensated cirrhosis of liver, Child Turcott Pugh (CTP) score ≥ 10, age between 18 years to 70 years. The following patients were excluded from the study: Septicemia, infection with HIV, episodes of variceal bleeding within 6 wk, hepatocellular carcinoma or any malignancy, hepatorenal syndrome at the time of enrolment, significant cardiac and respiratory disease, pregnancy, patients being taken up for transplant and refusal to participate in the study.

Detailed clinical history and physical examination of patients was done. All patients were tested for complete blood count, liver function tests, prothrombin time, blood sugar, alpha-fetoprotein, renal function tests, serum electrolytes, serum calcium, serum phosphorus, serum 25-OH VD, urine routine microscopic examination and culture, blood culture for aerobic and anaerobic organism, chest radiographs, endoscopy and color Doppler ultrasonography of abdomen. Patients also underwent diagnostic paracentesis and fluid analysis for protein, albumin, TLC, differential cell counts, and culture sensitivity. All of them were tested for HBsAg, anti-hepatitis B core antigen (HBc) IgG (total), and anti-hepatitis C virus (HCV) by ELISA. Appropriate tests for autoimmune liver disease, Wilson disease, and hemochromatosis (ANA, ASMA, anti-LKM1, serum ceruloplasmin, 24 h urinary copper analysis, and serum ferritin) were performed. The following investigations; anti-hepatitis E virus (HEV) IgM, anti-hepatitis A virus (HAV) IgM, and CT of whole abdomen were done whenever required.

Patients of CLD were diagnosed with the help of characteristic medical history, compatible physical examinations, blood investigations, radiological imaging and endoscopy. The diagnosis of CLD was defined on the basis of at least one of the following: Endoscopic evidence of esophageal varices of at least grade II in size, undisputable evidence on utrasonography or CT scan of cirrhosis of the liver and/or presence of portosystemic collaterals, and prior liver biopsy showing evidence of liver cirrhosis. Decompensated CLD was defined as CLD complicated with ascites and/or gastrointestinal variceal bleeding[15].

Patients with decompensated CLD were screened for serum 25-hydroxy VD (25-OH D) levels. Blood for 25-OH VD estimation was collected on admission. The assay was performed within 24 h of sample collection. Quantitative assessment of total 25-OH D was performed by direct competitive chemiluminescence immunoassay using commercially available kit Unicel® DxI 800 immunoassay systems (Beckman Coulter, Inc. CA, United States) (detection range 4-150 ng/mL in 250 μL of serum). The classification of the 25-OH VD status were as follows: Severe deficiency: < 10 ng/mL; deficiency: 10-20 ng/mL; insufficiency: 20-29 ng/mL; sufficiency: 30-100 ng/mL; (To convert results into SI units: ng/mL × 2.5 = nmol/L)[16]. Patient with serum VD level < 20 ng/mL was considered as VD deficient.

Patients with deficient VD level were randomly divided into treatment and control groups. Total number of VD deficient patients enrolled in study was 101. Fifty one patients were included in treatment group who received VD treatment in the form of intramuscular cholecalciferol 300000 IU as loading dose and 800 IU/d oral as maintenance dose along with 1000 mg oral calcium supplementation. Fifty VD deficient patients were not supplemented with VD acts as control group. Monitoring of VD; serum calcium and serum phosphorus was done monthly for 6-mo or till death, whichever occur earlier. Supplementation of VD was stopped if features of hypercalcemia, kidney stone, or serum 25 OH VD level > 80 nmol/L (> 32 ng/mL) observed.

Patients were treated with general supportive measures. Patients with hepatic encephalopathy were treated with anti-hepatic encephalopathy regimen. Renal failure was managed with either intravenous human albumin with or without intravenous terlipressin and dialysis as when indicated. Those without renal failure and encephalopathy were treated with diuretics for ascites. Therapeutic paracentesis was performed as when indicated. Patients were treated with inotropes for hypotension and with assisted ventilation for respiratory failure. Oral anti-viral drugs were used for the treatment of HBV infection. Treatment of alcoholism was done with abstinence and medications to increase abstinence. Those who were discharged in stable condition were followed up on outpatient basis.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analysis were performed using Stata version 10 (Stata Corp, TX, United States). The primary outcome was survival observed over a period of 6-mo. Continuous variables were presented as mean with 95%CI and categorical variables were reported as frequencies and percentages. Survival analysis was performed using Kaplan-Meir method followed by log-rank test for binary variables and Cox-proportional hazard method for continuous variable. Baseline variables between test and control group was compared using t-test for difference of means. A P-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

We evaluated 153 patients of decompensated CLD (CTP Score ≥ 10). Out of 153, 129 (84.31%) patients were deficient in serum VD. Out of 129, 28 patients were excluded from study due to following reason; upper gastrointestinal bleeding within 6 wk (18), hepatorenal syndrome (4), hepatocellular carcinoma (2), age < 18 years (2) and age > 70 years (1). A total of 101 patients were randomly enrolled in two groups: Treatment group (n = 51) and control group (n = 50). The mean age of the patients in the treatment group and control were 46.2 years (± 14.93) and 43.28 years (± 12.53), respectively. Male:female ratio in the treatment group and control were 40:11 and 37:13, respectively. There was no significant difference in age and sex ratio of two groups. The treatment and control groups were similar with respect to etiology of liver diseases. Most common etiology of CLD was ethanol in both control (n = 24; 48%) and treatment (n = 19; 38%) groups, followed by HBV (control = 20%; treatment = 24%), cryptogenic CLD (control = 14%; treatment = 20%), and hepatitis C virus (control = 8%; treatment = 8%). Other uncommon etiologies were NASH and Wilson disease.

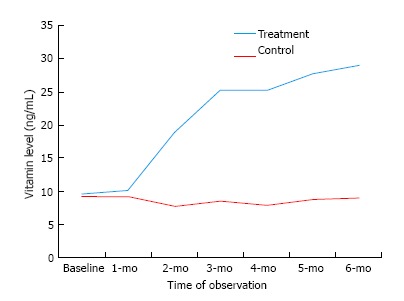

The baseline parameters in both the treatment and control groups were comparable (P > 0.05), except fever and blood TLC which were significantly higher in control group as compared to treatment group (P < 0.05) (Table 1). Baseline serum VD (ng/mL) in control group and treatment group were 9.15 (8.35-9.94) and 9.65 (8.63-10.7), respectively. Serum VD (ng/mL) at 6-mo in control group and treatment group were 9.02 (6.88-11.17) and 29 (23-35), respectively. Baseline serum calcium (mg/dL) in control group and treatment group were 7.8 (7.6-8.00) and 7.59 (7.4-7.7), respectively. Serum calcium (mg/dL) at 6-mo in control group and treatment group were 5.5 (4.23-6.6) and 6.7 (5.31-8.08), respectively. Baseline serum phosphorus (mg/dL) in control group and treatment group were 3.8 (3.7-4.06) and 3.68 (3.53-3.83), respectively. Serum phosphorus (mg/dL) at 6-mo in control group and treatment group were 2.68 (2.09-3.27) and 3.31 (2.61-4.10), respectively. Comparisons of level of VD, calcium and phosphorous over a period of 6 mo is summarized in Table 2. As compared to control group the levels of VD, calcium and phosphorus were higher in treatment group. Over the period of time the VD levels was better improved in treatment group compared to control group (Figure 1). Although, the level of serum calcium and phosphorus were decreasing over the period of time in both groups but treatment group had less decline compared to control group.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients in treatment (n = 51) and control group (n = 50) n (%)

| Parameters | Control groups (n = 50) | Treatment groups (n = 51) | P value |

| Age (yr) (mean ± SD) | 43.28 ± 12.53 | 46.21 ± 14.93 | > 0.05 |

| Sex (M:F) | 37:13 | 40:11 | |

| Mean (CI) serum bilirubin (mg/dL) | 8.95 (6.62-11.29) | 6.89 (5.15-8.64) | > 0.05 |

| Mean (CI) PT - INR | 1.50 (1.41-1.59) | 1.43 (1.37-1.48) | > 0.05 |

| ALT (IU/L) | 92 (61-119) | 84 (62-106) | > 0.05 |

| AST (IU/L) | 157 (98-215) | 127 (106-147) | > 0.05 |

| Mean (CI) serum albumin (g/dL) | 2.41 (2.32-2.50) | 2.38 (2.28-2.49) | > 0.05 |

| Mean (CI) serum creatinine | 1.11 (1.04-1.17) | 1.18 (1.13-1.24) | > 0.05 |

| Mean (CI) blood TLC (mm3/μL) | 10902 (9481-12322) | 8407 (7238-9576) | < 0.05 |

| Mean (CI) Ascitic fluid TLC (mm3/μL) | 233.84 (187.41-280.27) | 237.92 (193.48-282.32) | > 0.05 |

| Ascites | 50 (100) | 51 (100) | > 0.05 |

| Jaundice | 40 (80) | 41 (80.4) | > 0.05 |

| Encephalopathy | 21 (42) | 27 (52.94) | > 0.05 |

| Fever | 19 (38) | 10 (20) | < 0.05 |

| Mean (CI) CTP score | 10.92 (10.64-11.20) | 11.17 (10.83-11.52) | > 0.05 |

| Mean (CI) MELD score | 19.02 (17.91-20.12) | 18.62 (17.70-19.54) | > 0.05 |

| Etiology of CLD (%) | Ethanol (48), HBV (20), Cryptogenic (14), HCV (8), Ethanol + HBV (6), NASH (2), Wilson’s disease (2) | Ethanol (38), HBV (24), Cryptogenic (20), Ethanol + HBV (10), HCV (8), NASH (4) |

PT: Prothrombin time; AST: Aspartate aminotransferase; ALT: Alanine aminotransferase; CTP: Child Turcott Pugh.

Table 2.

Comparisons of level of vitamin D, calcium and phosphorous over a period of 6 mo

| Baseline | 3rd month | 6th month | ||

| Mean (CI) vitamin D (ng/mL) | Control | 9.15 (8.35-9.94) | 8.54 (6.95-10.13) | 9.02 (6.88-11.17) |

| Treatment | 9.65 (8.63-10.7) | 25.35 (21.59-29.10) | 29 (23-35) | |

| Mean (CI) calcium (mg/dL) | Control | 7.8 (7.6-8.00) | 6.2 (5.2-7.2) | 5.5 (4.23-6.6) |

| Treatment | 7.59 (7.4-7.7) | 7.7 (6.9-8.6) | 6.7 (5.31-8.08) | |

| Mean (CI) phosphorus (mg/dL) | Control | 3.8 (3.7-4.06) | 3.01 (2.51-3.51) | 2.68 (2.09-3.27) |

| Treatment | 3.68 (3.53-3.83) | 3.8 (3.3-4.2) | 3.31 (2.61-4.10) | |

Figure 1.

Comparison of vitamin D level between treatment and control group.

CTP score and model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) score at baseline were similar in treatment and control group (P > 0.05). We observed a decline in CTP score and MELD score in both the groups over the period of 6-mo time. The proportion of survival in treatment group (69%) was higher compared to control group (64%), but the difference was statistically not significant (P > 0.05). Also the mean survival duration in treatment group was 155 d (95%CI: 142-167) compared to control group, i.e., 141 d (95%CI: 125-157) (P > 0.05). Comparisons of CTP score, MELD score and survival over a period of 6-mo is summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Comparison of Child Turcott Pugh/Model For End-Stage Liver Disease score and survival (treatment vs control group)

| Parameters | Treatment group (n = 51) | Control group (n = 50) | P value |

| CTP score, mean (95%CI) | |||

| At base line | 11.17 (10.83-11.52) | 10.92 (10.64-11.20) | > 0.05 |

| 6th month | 6.09 (4.85-7.33) | 5.92 (4.63-7.20) | > 0.05 |

| MELD score, mean (95%CI) | |||

| At base line | 18.62 (17.70-19.54) | 19.02 (17.91-20.12) | > 0.05 |

| 6th month | 9.03 (7.09-10.97) | 8.82 (6.81-10.82) | > 0.05 |

| Survival at 6-mo | |||

| Survival | 35/51 (69%) | 32/50 (64%) | > 0.05 |

| Mean (CI) survival (d) | 155 (142-167) | 141 (125-157) | > 0.05 |

CTP: Child Turcott Pugh; MELD: Model for end-stage liver disease.

In univariate and multivariate analysis, the various parameters including bilirubin, creatinine, ascitic fluid TLC, CTP score, and MELD score were found significantly (P < 0.05) associated with 6-mo survival of the patients (Table 4). In univariate analysis, the parameters including hepatic encephalopathy, blood TLC, serum sodium, creatinine, PT- INR were also found significantly (P < 0.05) associated with 6-mo survival of the patients.

Table 4.

Factors associated with survival

| Methods, variables [mean (CI)] |

Univariate analysis |

Multivariate analysis |

||

| Crude HR (95%CI) | P value | Adjusted HR (95%CI) | P value | |

| Hepatic encephalopathy | 1.53 (1.15-2.01) | < 0.05 | ||

| Bilirubin | 1.04 (1.01-1.08) | < 0.05 | 0.90 (0.83-0.98) | < 0.05 |

| AST | 1.00 (0.99-1.00) | > 0.05 | ||

| Creatinine | 228 (21-2445) | < 0.05 | 57.43 (2.16-1522) | < 0.05 |

| PT-INR | 6.63 (2.52-17.5) | < 0.05 | ||

| Ascitic fluid TLC | 1.004 (1.002-1.006) | < 0.05 | 1.02 (1.00-1.04) | < 0.05 |

| Blood TLC | 1.00 (0.99-1.00) | > 0.05 | ||

| Serum Sodium | 0.92 (0.87-0.97) | < 0.05 | ||

| Treatment with VD | 0.92 (0.81-1.03) | > 0.05 | 0.46 (0.22-0.95) | < 0.05 |

| CTP score | 2.21 (1.69-2.89) | < 0.05 | 1.39 (1.00-1.95) | < 0.05 |

| MELD score | 1.34 (1.23-1.47) | < 0.05 | 1.60 (1.26-2.02) | < 0.05 |

PT: Prothrombin time; AST: Aspartate aminotransferase; VD: Vitamin D; CTP: Child Turcott Pugh; MELD: Model for end-stage liver disease.

Serum VD level had no significant association with mortality (P > 0.05). In the univariate analysis the unadjusted hazard ratio for the effect of VD supplementation on mortality was 0.92 (95%CI: 0.81-1.03) and it was not found significant (P > 0.05). In multivariate analysis, treatment with VD supplement was found significantly (P < 0.05) associated with survival of the patients over 6-mo. However, adjusted hazard ratio was < 1 (0.48), implying the significance of this result is low. Factors like treatment was also included into the model because we have observed that the levels of VD, calcium, and phosphorus were better in treatment group compared to control group.

DISCUSSION

We enrolled 101 patients in study; 51 and 50 patients in treatment and control group, respectively. Majority of patients were male in both treatment group and control groups. Mean age of presentation in both treatment group and control group was fourth decade. Ethanol was most common etiology of CLD followed by HBV infection. Alcohol is most common cause of CLD in many parts of India[17]. In our study cohort, all patients had advanced decompensated cirrhosis (CTP-C) with CTP score of ≥ 10. Almost all patients (100%) had ascites and 80% had jaundice. However, most of the previous studies have included patients of all three CTP classes[10,18] (Table 5).

Table 5.

Vitamin D deficiency in chronic liver disease

| Ref. | Disease (n) | Prevalence of VDD | Findings/conclusions |

| Ko et al[27], 2016 | Compensated CLD (n = 207) | 80% overall; 35% < 10 ng/mL; 45% < 20 ng/mL | VDD (< 10 ng/mL) in advanced vs no advanced fibrosis: 53% vs 24% (P < 0.05) |

| Gevora et al[28], 2014 | HCV related CLD (n = 296) | 82% < 80 nmol/L; 16% < 25 nmol/L | The inverse relationship noted between VD levels and viral load, liver fibrosis and treatment outcomes |

| Trépo et al[8], 2013 | ALD (n = 324) | 59% < 10 ng/mL | VDD are significantly associated with increased liver damage and mortality |

| Kitson et al[21], 2013 | HCV-1 related CLD (n = 274) | 48% < 75 nmol/L; 16% < 50 nmol/L | VD level is not associated with SVR or fibrosis stage, but VDD is associated with high activity grade |

| Arteh et al[19], 2010 | CLD (n = 113) | 92% < 32 ng/mL | VDD in cirrhotics vs noncirrhotics: 30% vs 14% (P = 0.05) |

| Costa Silva et al[29], 2015 | Cirrhosis (n = 133) | 70% < 30 ng/mL; 14% < 20 ng/mL | Significantly lower levels of VD were found at the time of acute decompensation |

| Savic et al[30], 2014 | ALD (n = 30) | 67% < 50 nmol/L | Highest prevalence of VDD were seen in CTP-C patients (P < 0.05) |

| Corey et al[31], 2014 | ESLD (n = 158) | 67% < 25 ng/mL | VDD is common among patients with ESLD awaiting LT |

| Putz-Bankuti et al[9], 2012 | Cirrhosis (n = 75) | 53% < 20 ng/mL | VD levels are inversely correlated with MELD and CTP scores (P < 0.05) |

| Malham et al[32], 2011 | Alcoholic cirrhosis (n = 89) | 85% < 50 nmol/L 55% < 25 nmol/L | VDD in cirrhosis relates to liver dysfunction rather than aetiology |

| Trépo et al[8], 2015 | Cirrhosis (n = 251) | 92% Overall; 69% < 10 ng/mL; 24% < 20 ng/mL | VDD in decompensated cirrhosis are associated with infectious complications and mortality |

| Anty et al[10], 2014 | Cirrhosis (n = 88) | 57% < 10 ng/mL | Severe VDD is a predictor of infection [OR = 5.44 (1.35-21.97), P < 0.05] |

| Stokes et al[18], 2014 | Cirrhosis (n = 65) | 86% < 20 ng/mL | VD levels is an independent predictors of survival [OR = 6.3 (1.2-31.2); P < 0.05] |

| Fernández Fernández et al[13], 2016 | CLD (n = 94) | 87% < 30 ng/mL or < 20 ng/mL | VD supplementation significantly improves CTP score |

| Zhang et al[14], 2016 | Cirrhosis with SBP (n = 119) | 100% | VD supplementation can up-regulate peritoneal macrophage VDR and LL-37 expressions and enhance defence against SBP |

| Rode et al[26], 2010 | CLD (n = 158) | 64% 25-54 nmol/L; 14% < 25 nmol/L | VDD improves with oral VD supplementation and VD levels fall without supplementation |

| Present study | Decompensated cirrhosis (n = 101) | 84% < 20 ng/mL | VD levels improved with VD supplementation. VD supplementation may increase the survival probability of patients of decompensated cirrhosis |

To convert results into SI units: ng/mL × 2.5 = nmol/L. VD: Vitamin D; VDD: Vitamin D deficiency; SBP: Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis; LT: Liver transplant; ALD: Alcoholic liver disease; ESLD: End stage liver disease.

Prevalence of VD deficiency is very high among patients with CLD. Most of the studies have showed VD deficiency in more than two-third patients with CLD (Tables 5 and 6). In a study by Arteh et al[19], VD deficiency was seen in more than 90% of patients with CLD, and at least one-third of them were suffering from severe VD deficiency. In another study, VD deficiency or insufficiency was found in 87% of the patients with CLD. VD levels were significantly lower in patients with CLD (15.9 ng/mL) and in alcoholic liver disease[13]. VD deficiency is common among patients with alcoholic liver disease[8], hepatitis C[20,21] and chronic hepatitis B (CHB) patients[22]. In our patient cohort of decompensated CLD, 84.31% patients had deficiency of serum VD.

Table 6.

Vitamin D deficiency and liver disease

| Ref. | Disease (n) | Prevalence of VDD | Findings/conclusions |

| Wong et al[22], 2015 | CHB (n = 426) | 82% < 32 ng/mL | VDD is associated with adverse clinical outcomes |

| Bril et al[33], 2015 | NASH (n = 239) | 31% < 30 ng/mL; 47% < 20 ng/mL | VD level is not associated the severity of NASH |

| Finkelmeier et al[34], 2014 | HCC (n = 200) | 38% < 20 ng/mL; 35% < 10 ng/mL | VD levels negatively correlated with the stage of cirrhosis as well as with stages of HCC |

| Guzmán-Fulgencio et al[35], 2014 | HIV-HCV coinfection (n = 174) | 16% < 25 nmol/L | VDD is associated with severity of liver disease F ≥ 2 [OR = 8.47 (1.88-38.3); P < 0.05] and A ≥ 2 [OR = 3.25 (1.06-10.1); P < 0.05] |

| Avihingsanon[36], 2014 | HCV (n = 331) HCV-HIV coinfection (n = 130) | < 30 ng/mL | Hypovitaminosis D is a predictor of advanced fibrosis [OR = 2.48 (1.09-5.67); P < 0.05] |

| El-Maouche et al[37], 2013 | HCV-HIV coinfection (n = 116) | 41% < 15 ng/mL | VDD is not associated with significant liver fibrosis (METAVIR ≥ 2) |

| Terrier et al[38], 2011 | HIV-HCV coinfection (n = 189) | 85% ≤ 30 ng/mL | Low VD level correlate with severe liver fibrosis |

| Petta et al[20], 2010 | HCV-1 (n = 197) | 73% ≤ 30 ng/mL | Low VD is linked to severe fibrosis and low SVR on interferon-based therapy |

| Fisher et al[39], 2007 | Noncholestatic CLD (n = 100) | 68% < 50 nmol/L, 23% 50-80 nmol/L | VDD is common in noncholestatic CLD |

To convert results into SI units: ng/mL × 2.5 = nmol/L. VD: Vitamin D; VDD: Vitamin D deficiency; CHB: Chronic hepatitis B; NASH: Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis; NAFLD: Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease; HCC: Hepatocellular carcinoma.

Studies have showed association of VD deficiency with the degree of liver dysfunction. Because of the association of VD deficiency with hepatic insufficiency and infections, authors have suggested the use of VD as a prognostic marker in the liver cirrhosis[10,18]. In a study, VD deficiency in patients of CLD was proportional to the severity of liver dysfunction[13]. Putz-Bankuti et al[9] measured VD level of 75 patients of CLD and patients were followed for median duration of 3.6 years. The study showed a statistically significant inverse correlations of 25(OH) D levels with the degree of liver function (MELD score and CTP score). In a prospective cohort study (n = 251) done by Finkelmeier et al[23], the mean serum concentration of VD was 8.93 ± 7.1 ng/mL, and 25(OH)D3 levels showed a inverse correlation with the MELD score.

Bacterial infections are the common cause of morbidity and mortality in patients with cirrhosis[24]. VD deficiency is associated with bacterial infections in cirrhotic patients. In a non-randomized study done by Anty et al[10], severe VD (<10 ng/mL) deficiency was seen in 56.8% of cirrhotic patients. As compared with the others, the severe VD deficient patients had significantly more infection rate (54% vs 29%, P < 0.05). A severe VD deficiency was a predictor of infection [OR = 5.44 (1.35-21.97); P < 0.05] independently of the CTP score [OR = 2.09 (1.47-2.97); P < 0.05]. VD exerts its antimicrobial effect through VD receptor (VDR), and LL-37, a VD-dependent antimicrobial peptide. In a study by Zhang et al[25] the ascites with spontaneous bacterial peritonitits (SBP) group showed significantly higher levels of both VDR and LL-37 mRNA expressions in peritoneal leukocytes than the ascites without SBP group (P < 0.05). Vitamin supplementations in patients of VD deficient patients have showed up-regulation of VDR and LL-37 in patients with SBP[14].

The association between VD deficiency and increased mortality is still controversial. Low 25-OH VD level has been reported to be associated with increased mortality in patients with CLD[8]. Studies have showed increased risk of complication and mortality in VD deficient patients with CLD. In a prospective study (n = 251), Finkelmeier et al[23] has showed significantly lower 25(OH) D3 levels in the patients with decompensated cirrhosis and infectious complications compared to patients without complications. Low 25(OH) D3 was associated with mortality in univariate and multivariate Cox regression models. Stokes et al[18] identified low VD levels and MELD scores as independent predictors of survival (P < 0.05) in patients with advanced liver cirrhosis. VD level of 6.0 ng/mL was determined as optimal cut-off for discriminating survivors from nonsurvivors. In a study, age- and gender-adjusted relative risk (95%CI) was 6.37 (1.75-23.2) for hepatic decompensation and 4.31 (1.38-13.5) for mortality within the first vs the third 25(OH) D tertile (P < 0.05). However, after additional adjustment for CTP or MELD score, associations between VD levels and hepatic decompansation and mortality showed a non-significant trend[9]. In our study cohort, VD level had no significant association with mortality. In this study, treatment with VD supplement was found significantly (P < 0.05) associated with survival of the patients over 6-mo. However, adjusted hazard ratio was < 1, implying the significance of this result is low.

Current clinical guidelines address the issue of VD supplementation for bone disease in liver cirrhosis and cholestatic disorders[16]. Role of VD supplementation to prolong survival in VD deficient liver cirrhotic patient is not known. A few studies have showed that VD supplementation may prolong life span in older people[11,12] . Authors have showed oral VD supplementation replenishes VD levels[26], improves CTP score[13], and enhance defence against SBP[14]. In a study by Fernández Fernández et al[13], after VD supplementation, significant improvements were observed in functional status assessed by the MELD and CTP score (P < 0.05). In our study cohort, over the period of time VD level was improved in treatment group compared to control group. We observed a decline in CTP and MELD score in both the groups over the period of 6-mo time, which can be explained by supportive therapy. However, we did not observed a greater decline in CTP score and MELD score in the treatment group compared to control group. Results of our study showed statistically non-significant trend in greater survival (69% vs 64%; P > 0.05) and longer survival (155 d vs 141 d; P > 0.05) in treatment group compared to control group. We did not find a study suggesting increase in survival of patients of VD deficient decompensated CLD after therapy with VD.

We also reviewed the data on the prevalence and the role of VDD in patients with liver disease. A concise literature review of VDD in patients with noncholestatic liver disease is summarized in Tables 5 and 6[27-39].

The dose of VD and mode of administration in VD deficient/insufficient patient of CLD is not clear. Lim et al[40] suggested periodic monitoring of VD in patients with CLD. Therapy is required in those with VD levels < 30 ng/mL, which includes administration of 5000 IU of vitamin D3 daily or 50000 IU of vitamin D2 or D3 weekly for 3 mo, followed by 1000 IU/d indefinitely. In a systemic review authors have recommended that vitamin D3 be used for supplementation over vitamin D2. A single VD doses ≥ 300000 IU are most effective at increasing VD levels[41]. Although both oral and intramuscular administration routes are effective and safe, intramuscular administration is more effective in increasing VD levels[42,43]. In our study, we used intramuscular cholecalciferol 300000 IU as loading dose and 800 IU/d oral as maintenance dose along with 1000 mg oral calcium supplementation.

There are a few limitations of our study, each of which are the relatively small sample size, single center study, and lack of an age and sex matched VD deficient control population without cirrhosis. We did not study the relationship of parathyroid hormone level on serum calcium and phosphorous levels. Impact of VD supplementation in various etiologies of CLD was also not assessed because of small number of patients in each sub-group. Therefore, the findings of this study need to be confirmed in larger multicenter studies.

In conclusion, VD deficiency is very common in patients of decompensated CLD. Replenishment of VD along with calcium supplementation may improve survival in patients with decompensated liver cirrhosis.

COMMENTS

Background

Function of vitamin D (VD) is not limited to bone mineral metabolism. The role of VD has also been implicated in the pathogenesis and treatment of infections, autoimmune, cardiovascular, and degenerative diseases and several types of cancer. Liver plays important role in conversion of inactive VD into active 25-hydroxy VD (25-OH VD). Vitamin D deficiency (VDD) is very common in patients of chronic liver disease (CLD). The role of VDD in the natural history of non-cholestatic CLD is not well described. Recently, VD deficiency is found to be associated with complications of CLD.

Research frontiers

The data regarding the association of VDD with complications and prognosis in patients with CLD are limited. The available literature suggests the association of VD deficiency with degree of liver fibrosis and functional liver dysfunction. There is increasing focus to find the relationship between the VD level and prognosis in patients with CLD. There are few studies suggesting the role of oral VD supplementation in replenishing VD levels, improving CTP score, and enhancing defence against spontaneous bacterial peritonitis in patients with CLD. More studies are necessary to establish the prognostic role of VDD in decompensated CLD. Current clinical guidelines address the issue of VD supplementation for bone disease in liver cirrhosis and cholestatic disorders. Effect of VD replenishment in increasing survival of patients with VD deficient decompensated cirrhosis has to be elucidated.

Innovations and breakthroughs

The current trial was designed to assess the VDD as a prognostic factor for survival in patients with decompensated CLD and effect of replenishment of VD on all-cause mortality in decompensated liver cirrhosis. Authors also performed concise review of role of VDD in patients with noncholestatic liver disease. In this study, there is suggestion that replenishment of VD may improve survival in patients with VD deficient decompensated cirrhosis compared to similarly-treated controls.

Applications

The results of the study add important scientific information on prognostic role of VD deficiency in patients with decompensated cirrhosis. This study provides evidence supporting the investigation of VD supplementation in improving prognosis in VD deficient patients with decompensated cirrhosis.

Terminology

Vitamin D deficiency: Patient with serum vitamin D level < 20 ng/mL is defined as vitamin D deficient.

Peer-review

The manuscript is well written and covers an area of current clinical interest. The data is presented and described well and comes from a reasonably sized cohort of patients.

Footnotes

Institutional review board statement: The study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Indira Gandhi Institute of Medical Sciences, Sheikhpura, Patna, India.

Informed consent statement: All study participants, or their legal guardian, provided written consent prior to study enrolment.

Conflict-of-interest statement: The authors of this manuscript having no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Data sharing statement: There is no additional data available.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: India

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

Peer-review started: November 15, 2016

First decision: December 20, 2016

Article in press: June 8, 2017

P- Reviewer: Lalor P, Sirin G S- Editor: Kong JX L- Editor: A E- Editor: Lu YJ

References

- 1.Holick MF. Vitamin D deficiency. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:266–281. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra070553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mahon BD, Wittke A, Weaver V, Cantorna MT. The targets of vitamin D depend on the differentiation and activation status of CD4 positive T cells. J Cell Biochem. 2003;89:922–932. doi: 10.1002/jcb.10580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Miragliotta G, Miragliotta L. Vitamin D and infectious diseases. Endocr Metab Immune Disord Drug Targets. 2014;14:267–271. doi: 10.2174/1871530314666141027102627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pilz S, Tomaschitz A, Obermayer-Pietsch B, Dobnig H, Pieber TR. Epidemiology of vitamin D insufficiency and cancer mortality. Anticancer Res. 2009;29:3699–3704. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pilz S, Tomaschitz A, Drechsler C, Dekker JM, März W. Vitamin D deficiency and myocardial diseases. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2010;54:1103–1113. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.200900474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.DeLuca HF. Overview of general physiologic features and functions of vitamin D. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;80:1689S–1696S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/80.6.1689S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kitson MT, Roberts SK. D-livering the message: the importance of vitamin D status in chronic liver disease. J Hepatol. 2012;57:897–909. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2012.04.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Trépo E, Ouziel R, Pradat P, Momozawa Y, Quertinmont E, Gervy C, Gustot T, Degré D, Vercruysse V, Deltenre P, et al. Marked 25-hydroxyvitamin D deficiency is associated with poor prognosis in patients with alcoholic liver disease. J Hepatol. 2013;59:344–350. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2013.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Putz-Bankuti C, Pilz S, Stojakovic T, Scharnagl H, Pieber TR, Trauner M, Obermayer-Pietsch B, Stauber RE. Association of 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels with liver dysfunction and mortality in chronic liver disease. Liver Int. 2012;32:845–851. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2011.02735.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Anty R, Tonohouan M, Ferrari-Panaia P, Piche T, Pariente A, Anstee QM, Gual P, Tran A. Low Levels of 25-Hydroxy Vitamin D are Independently Associated with the Risk of Bacterial Infection in Cirrhotic Patients. Clin Transl Gastroenterol. 2014;5:e56. doi: 10.1038/ctg.2014.6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bjelakovic G, Gluud LL, Nikolova D, Whitfield K, Wetterslev J, Simonetti RG, Bjelakovic M, Gluud C. Vitamin D supplementation for prevention of mortality in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;(1):CD007470. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007470.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bolland MJ, Grey A, Gamble GD, Reid IR. The effect of vitamin D supplementation on skeletal, vascular, or cancer outcomes: a trial sequential meta-analysis. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2014;2:307–320. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(13)70212-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fernández Fernández N, Linares Torres P, Joáo Matias D, Jorquera Plaza F, Olcoz Goñi JL. [Vitamin D deficiency in chronic liver disease, clinical-epidemiological analysis and report after vitamin d supplementation] Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;39:305–310. doi: 10.1016/j.gastrohep.2015.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang C, Zhao L, Ding Y, Sheng Q, Bai H, An Z, Xia T, Wang J, Dou X. Enhanced LL-37 expression following vitamin D supplementation in patients with cirrhosis and spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Liver Int. 2016;36:68–75. doi: 10.1111/liv.12888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Primignani M, Carpinelli L, Preatoni P, Battaglia G, Carta A, Prada A, Cestari R, Angeli P, Gatta A, Rossi A, et al. Natural history of portal hypertensive gastropathy in patients with liver cirrhosis. The New Italian Endoscopic Club for the study and treatment of esophageal varices (NIEC) Gastroenterology. 2000;119:181–187. doi: 10.1053/gast.2000.8555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Holick MF, Binkley NC, Bischoff-Ferrari HA, Gordon CM, Hanley DA, Heaney RP, Murad MH, Weaver CM; Endocrine Society. Evaluation, treatment, and prevention of vitamin D deficiency: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96:1911–1930. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-0385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jha AK, Nijhawan S, Rai RR, Nepalia S, Jain P, Suchismita A. Etiology, clinical profile, and inhospital mortality of acute-on-chronic liver failure: a prospective study. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2013;32:108–114. doi: 10.1007/s12664-012-0295-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stokes CS, Krawczyk M, Reichel C, Lammert F, Grünhage F. Vitamin D deficiency is associated with mortality in patients with advanced liver cirrhosis. Eur J Clin Invest. 2014;44:176–183. doi: 10.1111/eci.12205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arteh J, Narra S, Nair S. Prevalence of vitamin D deficiency in chronic liver disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55:2624–2628. doi: 10.1007/s10620-009-1069-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Petta S, Cammà C, Scazzone C, Tripodo C, Di Marco V, Bono A, Cabibi D, Licata G, Porcasi R, Marchesini G, et al. Low vitamin D serum level is related to severe fibrosis and low responsiveness to interferon-based therapy in genotype 1 chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2010;51:1158–1167. doi: 10.1002/hep.23489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kitson MT, Dore GJ, George J, Button P, McCaughan GW, Crawford DH, Sievert W, Weltman MD, Cheng WS, Roberts SK. Vitamin D status does not predict sustained virologic response or fibrosis stage in chronic hepatitis C genotype 1 infection. J Hepatol. 2013;58:467–472. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2012.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wong GL, Chan HL, Chan HY, Tse CH, Chim AM, Lo AO, Wong VW. Adverse effects of vitamin D deficiency on outcomes of patients with chronic hepatitis B. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13:783–790.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2014.09.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Finkelmeier F, Kronenberger B, Zeuzem S, Piiper A, Waidmann O. Low 25-Hydroxyvitamin D Levels Are Associated with Infections and Mortality in Patients with Cirrhosis. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0132119. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0132119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Arvaniti V, D’Amico G, Fede G, Manousou P, Tsochatzis E, Pleguezuelo M, Burroughs AK. Infections in patients with cirrhosis increase mortality four-fold and should be used in determining prognosis. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:1246–1256, 1256.e1-1256.e5. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang C, Zhao L, Ma L, Lv C, Ding Y, Xia T, Wang J, Dou X. Vitamin D status and expression of vitamin D receptor and LL-37 in patients with spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Dig Dis Sci. 2012;57:182–188. doi: 10.1007/s10620-011-1824-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rode A, Fourlanos S, Nicoll A. Oral vitamin D replacement is effective in chronic liver disease. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 2010;34:618–620. doi: 10.1016/j.gcb.2010.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ko BJ, Kim YS, Kim SG, Park JH, Lee SH, Jeong SW, Jang JY, Kim HS, Kim BS, Kim SM, et al. Relationship between 25-Hydroxyvitamin D Levels and Liver Fibrosis as Assessed by Transient Elastography in Patients with Chronic Liver Disease. Gut Liver. 2016;10:818–825. doi: 10.5009/gnl15331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gerova DI, Galunska BT, Ivanova II, Kotzev IA, Tchervenkov TG, Balev SP, Svinarov DA. Prevalence of vitamin D deficiency and insufficiency in Bulgarian patients with chronic hepatitis C viral infection. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 2014;74:665–672. doi: 10.3109/00365513.2014.930710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Costa Silva M, Erotides Silva T, de Alentar ML, Honório Coelho MS, Wildner LM, Bazzo ML, González-Chica DA, Dantas-Corrêa EB, Narciso-Schiavon JL, Schiavon Lde L. Factors associated with 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels in patients with liver cirrhosis. Ann Hepatol. 2015;14:99–107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Savic Z, Damjanov D, Curic N, Kovacev-Zavisic B, Hadnadjev L, Novakovic-Paro J, Nikolic S. Vitamin D status, bone metabolism and bone mass in patients with alcoholic liver cirrhosis. Bratisl Lek Listy. 2014;115:573–578. doi: 10.4149/bll_2014_111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Corey RL, Whitaker MD, Crowell MD, Keddis MT, Aqel B, Balan V, Byrne T, Carey E, Douglas DD, Harrison ME, et al. Vitamin D deficiency, parathyroid hormone levels, and bone disease among patients with end-stage liver disease and normal serum creatinine awaiting liver transplantation. Clin Transplant. 2014;28:579–584. doi: 10.1111/ctr.12351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Malham M, Jørgensen SP, Ott P, Agnholt J, Vilstrup H, Borre M, Dahlerup JF. Vitamin D deficiency in cirrhosis relates to liver dysfunction rather than aetiology. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:922–925. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i7.922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bril F, Maximos M, Portillo-Sanchez P, Biernacki D, Lomonaco R, Subbarayan S, Correa M, Lo M, Suman A, Cusi K. Relationship of vitamin D with insulin resistance and disease severity in non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. J Hepatol. 2015;62:405–411. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2014.08.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Finkelmeier F, Kronenberger B, Köberle V, Bojunga J, Zeuzem S, Trojan J, Piiper A, Waidmann O. Severe 25-hydroxyvitamin D deficiency identifies a poor prognosis in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma - a prospective cohort study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;39:1204–1212. doi: 10.1111/apt.12731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Guzmán-Fulgencio M, García-Álvarez M, Berenguer J, Jiménez-Sousa MÁ, Cosín J, Pineda-Tenor D, Carrero A, Aldámiz T, Alvarez E, López JC, Resino S. Vitamin D deficiency is associated with severity of liver disease in HIV/HCV coinfected patients. J Infect. 2014;68:176–184. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2013.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Avihingsanon A, Jitmitraparp S, Tangkijvanich P, Ramautarsing RA, Apornpong T, Jirajariyavej S, Putcharoen O, Treeprasertsuk S, Akkarathamrongsin S, Poovorawan Y, et al. Advanced liver fibrosis by transient elastography, fibrosis 4, and alanine aminotransferase/platelet ratio index among Asian hepatitis C with and without human immunodeficiency virus infection: role of vitamin D levels. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;29:1706–1714. doi: 10.1111/jgh.12613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.El-Maouche D, Mehta SH, Sutcliffe CG, Higgins Y, Torbenson MS, Moore RD, Thomas DL, Sulkowski MS, Brown TT. Vitamin D deficiency and its relation to bone mineral density and liver fibrosis in HIV-HCV coinfection. Antivir Ther. 2013;18:237–242. doi: 10.3851/IMP2264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Terrier B, Carrat F, Geri G, Pol S, Piroth L, Halfon P, Poynard T, Souberbielle JC, Cacoub P. Low 25-OH vitamin D serum levels correlate with severe fibrosis in HIV-HCV co-infected patients with chronic hepatitis. J Hepatol. 2011;55:756–761. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2011.01.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fisher L, Fisher A. Vitamin D and parathyroid hormone in outpatients with noncholestatic chronic liver disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:513–520. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2006.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lim LY, Chalasani N. Vitamin d deficiency in patients with chronic liver disease and cirrhosis. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2012;14:67–73. doi: 10.1007/s11894-011-0231-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kearns MD, Alvarez JA, Tangpricha V. Large, single-dose, oral vitamin D supplementation in adult populations: a systematic review. Endocr Pract. 2014;20:341–351. doi: 10.4158/EP13265.RA. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Masood MQ, Khan A, Awan S, Dar F, Naz S, Naureen G, Saghir S, Jabbar A. Comparison of vitamin d replacement strategies with high-dose intramuscular or oral cholecalciferol: a prospective intervention study. Endocr Pract. 2015;21:1125–1133. doi: 10.4158/EP15680.OR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tellioglu A, Basaran S, Guzel R, Seydaoglu G. Efficacy and safety of high dose intramuscular or oral cholecalciferol in vitamin D deficient/insufficient elderly. Maturitas. 2012;72:332–338. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2012.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]