Abstract

Background

The aim of this study was to evaluate the use of a glucose meter with surgical patients under general anesthesia in the operating room.

Methods

Glucose measurements were performed intraoperatively on 368 paired capillary and arterial whole blood samples using a Nova StatStrip (Nova Biomedical, Waltham Ma) glucose meter and compared to 368 reference arterial whole blood glucose measurements by blood gas analyzer in 196 patients. Primary outcomes were median bias (meter minus reference), percent glucose meter samples meeting accuracy criteria for subcutaneous insulin dosing as defined by Parkes error grid analysis for Type I Diabetes, and accuracy criteria for intravenous insulin infusion as defined by Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute guidelines. Time under anesthesia, patient position, diabetes status and other variables were studied to determine whether any affected glucose meter bias.

Results

Median bias (interquartile range) was −4 (−9, 0) mg/dL, which did not differ from median arterial meter bias of −5 (−9, −1) mg/dL (p=0.32). All capillary and arterial glucose meter values met acceptability criteria for subcutaneous insulin dosing, while only 89% (327/368) of capillary and 93% (344/368) arterial glucose meter values met accuracy criteria for intravenous insulin infusion. Time, patient position, and diabetes status were not associated with meter bias.

Conclusions

Capillary and arterial blood glucose measured using the glucose meter are acceptable for intraoperative subcutaneous insulin dosing. Whole blood glucose on the meter did not meet accuracy guidelines established specifically for more intensive (e.g. intravenous insulin) glycemic control in the acute care environment.

INTRODUCTION

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, approximately 9.3% of the United States population has diabetes, with 27% of the population being undiagnosed1. While glycemic control for critically ill patients remain controversial2–4, glycemic control using insulin in patient with diabetes undergoing surgery has become an increasingly common quality metric5. Treatment of hyperglycemia requires monitoring of blood glucose, as even a single episode of severe hypoglycemia (glucose < 40 mg/dL) may increase the risk of death in the hospital up to two-fold6. Guidelines recommend glucose monitoring for patients under general anesthesia if the patient receives insulin, the procedure is longer than one-two hours, or if there is concern for hyper- or hypoglycemia7,8.

Glucose monitoring can be done using laboratory serum or plasma glucose analysis, whole blood glucose by blood gas analyzer, or whole blood glucose by glucose meter. While laboratory and blood gas analysis methods require an arterial or venous blood specimen, most glucose meters can also analyze capillary (via fingerstick) blood. Glucose analysis by laboratory methods is more time consuming and expensive than glucose meter testing and may not provide timely results for dosing insulin or treating hyper- or hypoglycemia in the operating room (OR).

The correlation between results from glucose meters and laboratory glucose measurements varies between meter technologies9 and correlation in the hypoglycemic and hyperglycemic ranges is poor for some meters10,11. Though newer technologies may provide more accuracy12–14, there is still concern about the use of meters in the critically ill15,16. Studies have demonstrated potentially dangerous discrepancies in capillary glucose measurement in patients on vasopressor therapy10,17, patients in shock18 or with poor tissue perfusion19, and in other critically ill patient populations20. Consequently, no glucose meter is currently approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for use with capillary samples in critically ill hospitalized patients.

While the FDA has not provided a definition of what constitutes “critically ill” for purposes of capillary glucose testing, previous studies21 have shown that factors expected to change rapidly during anesthesia and surgery can affect glucose meter accuracy. These factors include hematocrit, blood pressure, peripheral perfusion, temperature, anesthesia technique, medications, PO2 and pH. Vasopressor therapy has been associated with glucose meter outliers in the intensive care unit. Therefore patients receiving vasopressors intraoperatively may also be at risk of glucose meter errors or outliers. Despite these concerns, very few studies of glucose meter accuracy in the OR have been performed.

The aim of this study was to assess the accuracy of a newer glucose meter technology (Nova StatStrip, Nova Biomedical Corp., Waltham, MA) with hematocrit and interference correction, in the OR with patients under general anesthesia. We hypothesized that capillary and arterial whole blood samples analyzed on the glucose meter would meet established accuracy criteria for safe and effective insulin dosing. We also studied the impact of patient position, time under general anesthesia (early vs. late paired measurements), diabetes status, and other clinical and laboratory variables on the relationship between glucose meter and reference glucose concentrations.

MATERIALS and METHODS

Patient Selection

Members of the Anesthesia Clinical Research Unit performed a manual scan of the following day’s surgical listing for all patients scheduled for thoracic, vascular or neurologic surgery from August 2014–March 2015 (N=234 screened). Study participants had to be 18 years or older, have a pre-operative hemoglobin > 10 mg/dL, and speak English. A diagnosis of diabetes was neither an inclusion or exclusion criteria. Glucose testing was performed only on patients who had an arterial catheter placed. The decision to place an arterial catheter was at the discretion of the anesthesia provider at the time of surgery and the anesthesia provider was not aware of the patient’s study participation. The study design was approved by the Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board and written informed consent was obtained from all subjects.

Sample Collection and glucose analysis

Sample collection was performed by the Mayo Clinic Clinical Trials Research Unit. Members of Clinical Trials Research Unit nursing staff came to the OR approximately 30 minutes after the arterial catheter placement and obtained the first set of samples. Each set included (1) a capillary fingerstick sample tested on the glucose meter, (2) an arterial whole blood sample tested on the glucose meter, and (3) an arterial whole blood sample tested in the laboratory on a blood gas analyzer (Radiometer ABL90, Radiometer America Inc, Brea, CA). The arterial whole blood used for samples (2) and (3) were from the same blood draw, and were collected in a 3 mL lithium heparin blood gas syringe. The arterial glucose result from the laboratory blood gas analyzer was considered the reference value. Arterial blood samples were obtained within 10 minutes of capillary sampling, and laboratory blood glucose analysis was performed within 10 minutes of arterial whole blood collection. Staff from the Clinical Trials Research Unit obtained a second set of samples approximately 60 minutes after the first set. All patients were under general anesthesia at the time of both glucose sample collections. Capillary samples from patients in the lateral position were obtained from a finger on the lower (dependent) hand. Staff from the Clinical Trials Research Unit were trained on glucose meter operation and capillary sampling according to manufacturer’s instructions and laboratory procedures. Blood gas analyzer testing was performed by trained technologists in the testing laboratory and the blood gas data, including glucose, was available to providers for clinical use.

Perioperative data

Subject data including temperature, systolic and diastolic blood pressure, mean arterial pressure, heart rate, as well clinical variables and patient demographic information was extracted using a customized, integrative relational research database that contains a near-real time copy of clinical, administrative, and environmental exposure data from the Electronic Medical Record, Hospital Surgical Listing, and Mayo Clinic Life Sciences System databases22,23. All intraoperative variables were electronically captured with 3-minute resolution. Additional laboratory data (hemoglobin, pH, PCO2, PO2) was obtained from the sample submitted for reference glucose determination on the blood gas analyzer, or retrieved from clinical databases. Manual review of the data for fidelity was performed with removal of obvious errors resulting from measurement techniques.

Statistical analysis

Primary outcomes for the study were median bias, and percent glucose meter samples meeting accuracy criteria for subcutaneous and intravenous insulin infusion.

Median (interquartile range, IQR) bias between capillary glucose meter and reference glucose concentration, and median (IQR) bias between arterial glucose meter and reference glucose concentration was calculated (meter glucose minus reference glucose). Univariate linear regression with generalized estimating equations (GEE) analysis was used to assess for differences in median bias between capillary bias and arterial bias, while accounting for the correlation between up to two observations per patient. To assess whether time under general anesthesia impacted glucose meter accuracy, linear regression with GEE was also used to determine if glucose meter bias differed between samples collected early during surgery (within 30 minutes after arterial catheter placement) versus later during surgery (approximately 60 minutes after the initial capillary sample). We also performed linear regression with GEE to determine if limb position during surgery (lateral vs. supine) affected capillary glucose bias.

Clinical concordance between glucose meter and reference glucose values for subcutaneous insulin dosing was assessed using the Parkes error grid for Type 1 Diabetes24, developed by a consensus of endocrinologists to define glucose meter accuracy needed for safe and effective subcutaneous insulin dosing. The Parkes error grid displays the relationship between glucose meter and reference glucose by use of an error grid divided into five risk zones. Zone A represents no effect on clinical action (glucose meter and reference glucose value would lead to the same clinical action). Zone B represents altered clinical action with little or no effect on clinical outcome. Zone C represents altered clinical action—likely to impact clinical outcome; Zone D altered clinical action—could have significant medical risk; and Zone E altered clinical action—could have dangerous consequences24. Consistent with the ISO 15197:2013 guideline used by glucose meter manufacturers25, we defined acceptable accuracy for subcutaneous insulin dosing as 99% of glucose meter values within Zones A and B on the Parkes error grid.

We defined accuracy requirements for more intensive glucose monitoring (e.g. that required for intravenous insulin dosing) using the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute guideline CLSI POCT12-A326. CLSI POCT12-A3 is a consensus guideline developed to define accuracy requirements for acute care use of glucose meters (including intravenous insulin administration). It states that 95% of glucose meter results should be within ± 12 mg/dL of reference glucose value for reference glucose values <100 mg/dL and ± 12.5% for reference glucose ≥100 mg/dL. In addition, the guidelines require that no more than 2% of results contain error exceeding ± 15 mg/dL (for reference glucose <75 mg/dL) or 20% (for reference glucose ≥75 mg/dL)26.

CLSI POCT12-A3 guidelines suggest a minimum of 200 measurements from 100 samples be measured to determine accuracy in a given patient population. In previous studies we were able to differentiate glucose meter bias between capillary and arterial samples with 100 samples27. We used the CLSI guidelines and previous experience to determine that 300 or more measurements from 150 or more patients would allow us to differentiate glucose meter bias in capillary and arterial samples.

Univariate linear regression with GEE was used to perform post-hoc statistical analysis to determine whether clinical variables such as age, sex, diabetes status, disease severity (age-adjusted Charlson comorbidity index28), body mass index, temperature, blood pressure (systolic, diastolic and mean arterial), or heart rate impacted the relationship (bias) between either capillary or arterial glucose meter and reference glucose concentration (secondary outcomes). For age-adjusted Charlson comorbidity index28, we compared glucose meter bias in patients with few comorbidities (index 0–3) to patients with more comorbidities (index 4–6). For blood pressure the average systolic, diastolic and mean arterial pressure in the 15 minutes before a capillary sampling (measurements were recorded every three minutes) was used to determine whether blood pressure impacted the accuracy of capillary or arterial glucose meter measurement. A similar approach was used for heart rate and temperature (average value within 15 minutes of capillary sampling). Before the study we planned the use of univariate analysis with GEE to determine whether laboratory variables including pH, hemoglobin, PO2, and PCO2 affected glucose meter bias (secondary outcomes). All tests were two-sided, and p<0.05 was considered statistically significant. SAS v9.4M3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC) was used for all analyses.

RESULTS

Participants

Two-hundred and thirty-five subjects were assessed for study eligibility. Fifteen refused to participate, one had a starting hemoglobin <10mg/dL, and one did not speak English. Of the 218 subjects that were consented, twenty-two subjects did not have at least one pair of capillary and arterial samples drawn (arms not accessible, arterial catheter not placed, surgery cancelled) or were missing one or more glucose values for comparison. Thus 196 patients had one or more complete sets of samples obtained for analysis. One hundred ninety two complete sets were obtained for analysis at the first blood draw (within 30 minutes of arterial catheter placement), while 176 complete second sample sets (approximately one hour after first sample) were obtained. Characteristics of the participants studied and the surgical procedures, including positioning, fluid administration, and vasopressor use are provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Participant, surgery, and anesthesia characteristics.

| Age, y, median (IQR) | 61 (53, 68) |

| Female N (%) | 98 (50) |

| Height, cm, median (IQR) | 171 (163, 179) |

| Weight, kg, median (IQR) | 83.6 (70.3, 100.5) |

| BMI, kg/m2, median (IQR) | 28.8 (24.6, 33.4) |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 21 (11) |

| Charlson comorbidity score, age adjusted (IQR) | 3 (2,3) |

| Surgery type | |

| Intracranial, n (%) | 81 (41) |

| Thoracic, n (%) | 97 (49) |

| General, urological, spine, n (%) | 18 (9) |

| Surgical position | |

| Supine, n (%) | 78 (40) |

| Lateral, n (%) | 112 (57) |

| Prone, n (%) | 6 (3) |

| Anesthetic type | |

| Volatile anesthesia, n (%) | 179 (91) |

| Intravenous anesthesia, n (%) | 3 (2) |

| Intravenous and volatile anesthesia, n (%) | 14 (7) |

| Insulin, n (%) | 12 (6) |

| Intravenous fluids, mL, median (IQR) | 834 (545, 1288) |

| Vasopressors, n (%) | 92 (47) |

| Phenylephrine, mcg, median (IQR) | 300 (133, 600) |

| Ephedrine, mg, median (IQR) | 15 (10, 30) |

| Phenylephrine infusion, n (%) | 18 (9) |

IQR = interquartile range. Insulin is number of patients who had any insulin administered subcutaneously within 12 hours prior to surgery or as an intravenous infusion during the sampling period. Intravenous fluids are the total volume of all fluids (crystalloid and colloid) administered during the sampling period. Vasopressors are the number of patients who had a vasoactive medication administered during sampling period (phenylephrine, ephedrine, or vasopressin; phenylephrine was the only vasoactive medication administered as an infusion).

Median bias and accuracy criteria

Median (IQR) bias among the 192 capillary samples collected within 30 minutes of arterial catheter placement was −4 (−8, −1) mg/dL; while median (IQR) capillary bias among the 176 samples collected ~ 60 minutes after the first sampling was −5 (−10, 0) mg/dL (p =0.85, no difference in median bias between first and second collection). Thus, time under anesthesia (time in surgery) did not affect the accuracy of capillary sampling for glucose. Time under anesthesia also did not impact the accuracy of arterial sampling (data not shown). We therefore combined early and late measurements for all subsequent statistical analysis (n=368 for all subsequent analysis).

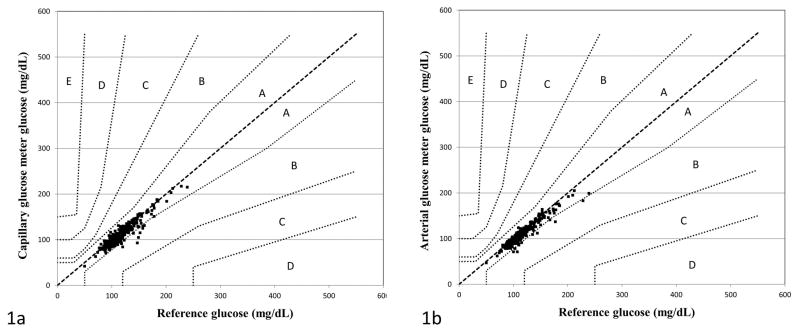

The glucose meter slightly but systematically underestimated glucose concentrations using both capillary and arterial samples. Median (IQR) bias between capillary glucose meter and reference glucose was −4 (−9, 0) mg/dL; while median (IQR) bias between arterial glucose meter and reference glucose was −5 (−9, −1) mg/dL (p=0.32, no significant difference between capillary and arterial meter bias). Parkes error grid analysis for Type 1 Diabetes was used to assess the clinical concordance of glucose meter values (both capillary and arterial) for subcutaneous insulin dosing. All capillary and arterial glucose meter values were within Zones A and B of the Parkes error grid (i.e. 100% of meter results met accuracy criteria), with the vast majority falling into Zone A (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Clinical concordance between capillary glucose meter (1a) and arterial glucose meter (1b) and reference glucose values as demonstrated by the Parkes error grid for Type 1 Diabetes. To meet ISO 15197:2013 accuracy guidelines, 99% of glucose meter values must fall within zone A (no effect on clinical action) or zone B (altered clinical action—little or no effect on clinical outcome). Zones C-E on the error grid represent progressively more serious insulin dosing errors that may lead to patient harm.

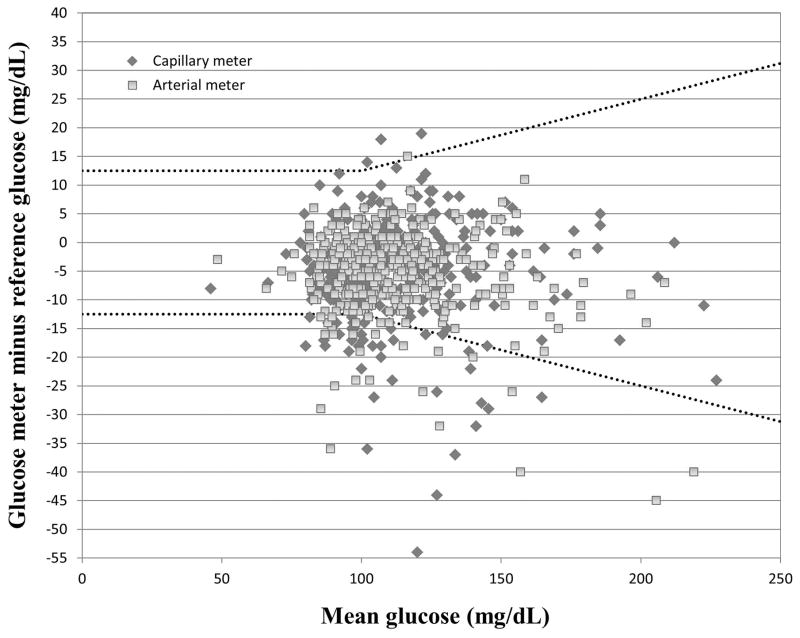

Capillary glucose bias ranged from −44 mg/dL to 19 mg/dL, while arterial glucose bias ranged from −45 mg/dL to 15 mg/dL (Figure 2). Three hundred twenty seven of 368 (89%) capillary and 344 of 368 (93%) arterial glucose meter values met CLSI POCT12-A3 accuracy guidelines for intravenous insulin dosing (±12 mg/dL at reference glucose <100 mg/dL and ±12.5% at reference glucose≥100 mg/dL). Glucose meter “outlier” results, those exceeding 20% of the reference glucose value, were observed with 7/368 (2%) of both capillary and arterial glucose meter values.

Figure 2.

Bland Altman plot of capillary and arterial glucose meter bias (glucose meter minus reference glucose) vs. mean of glucose meter and reference glucose value. Dashed lines represent CLSI POCT12-A3 error tolerances of ± 12.5 mg/dL (reference glucose < 100 mg/dl) and ±12.5% (reference glucose ≥100 mg/dL).

Impact of limb position on capillary and arterial bias

One hundred twelve patients had 213 capillary meter measurements during surgery with limbs in the lateral position, while 78 patients had 144 capillary measurements in the supine position and 6 patients had 11 measurements in the prone position. Median capillary glucose bias for measurements in the lateral position was −4 (−9, 0) mg/dL; compared to −4 (−9, 0) mg/dL for measurements in the supine position (p=0.92). Analysis was not conducted for measurements in the prone position due to the small number of measurements. Similarly, limb position did not impact arterial glucose meter bias (data not shown).

Impact of clinical variables on capillary and arterial glucose meter measurement

We performed univariate linear regression with GEE to determine whether age, sex, diabetes status, disease severity as measured by age-adjusted Charlson comorbidity index, body mass index, blood pressure or heart rate impacted the relationship between capillary or arterial whole blood (glucose meter) and reference glucose concentration. Among clinical variables, only age-adjusted Charlson comorbidity index demonstrated a statistically significant relationship to capillary glucose meter bias (p=0.04). However the magnitude (slope estimate) of that effect was small (1.9 mg/dL increase in bias for patients with higher risk scores) (Table 2). Diabetes status did not impact either capillary or arterial glucose meter bias (Table 2). For arterial whole blood glucose measured on the meter, only mean diastolic blood pressure in the 15 minutes before testing had a significant effect on glucose meter bias, but again the magnitude of the effect was small (0.7 mg/dL per 10 mm Hg change in diastolic blood pressure, p=0.03) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Relationship between clinical variables and capillary and arterial glucose meter bias (compared to reference glucose). Slope estimate is from univariate linear regression with generalized estimating equations, and estimates magnitude of change in glucose meter bias per unit of variable (for continuous variables) or between groups (for categorical variables). Slope estimates include 95th percentile confidence intervals. P < 0.05 indicates statistically significant relationship between variable and glucose meter bias.

| Capillary glucose meter bias | Arterial glucose meter bias | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Unit change | Slope estimate (mg/dL) [95% CI] | P value | Slope estimate (mg/dL) [95% CI] | P value |

| Gender | Male vs Female | −0.38 [−2.18, 1.43] | 0.68 | 0.34 [−1.23, 1.91] | 0.67 |

| Age | 10 years | −0.59 [−1.30, 0.12] | 0.11 | −0.24 [−0.81, 0.33] | 0.40 |

| Diabetes status | Diabetes vs. no diabetes | −0.58 [−4.61, 3.44] | 0.78 | −2.68 [−6.44, 1.08] | 0.19 |

| Charlson age-adjusted comorbidity index | Risk score 4–6 vs. 0–3 | −1.90 [−3.68, −0.11] | 0.04 | −1.09 [−2.65, 0.47] | 0.17 |

| Body mass index | 1 kg/m2 | −0.05[−0.17, 0.06] | 0.34 | −0.03 [−0.13, 0.07] | 0.54 |

| Mean systolic BP | 10 mm Hg | −0.82 [−1.71, 0.06] | 0.09 | −0.48 [−1.02, 0.07] | 0.10 |

| Mean diastolic BP | 10 mm Hg | −0.19 [−1.37, 0.99] | 0.75 | −0.73 [−1.40, −0.07] | 0.03 |

| Mean temperature | 1 ° C | 0.96 [−3.60, 5.53] | 0.68 | 2.61 [−1.80, 7.02] | 0.27 |

| Mean heart rate | 1 beat/minute | −0.03 [−0.15, 0.10] | 0.67 | −0.03 [−0.10, 0.05] | 0.48 |

Among laboratory variables, only PCO2 significantly impacted the relationship between capillary glucose meter and reference glucose (p=0.04). As with clinical variables, the magnitude (slope estimate) of these effects was small (1.5 mg/dL change in bias per 10 mm Hg PCO2, Table 3). There were no laboratory variables that impacted the relationship between arterial glucose meter and reference glucose concentration (Table 3).

Table 3.

Relationship between laboratory variables and capillary and arterial glucose meter bias (compared to reference glucose). Slope estimate is from univariate linear regression with generalized estimating equations and estimates magnitude of change in glucose meter bias per unit of variable. Slope estimates include 95th percentile confidence intervals. P < 0.05 indicates statistically significant relationship between variable and glucose meter bias.

| Capillary glucose meter bias | Arterial glucose meter bias | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Unit change | Slope estimate (mg/dL) [95% CI] | P value | Slope estimate (mg/dL) [95% CI] | P value |

| Hemoglobin | 1 mg/dL | 0.09 [−0.54, 0.72] | 0.77 | 0.31 [−0.26, 0.89] | 0.28 |

| pH | 0.1 pH unit | 1.55 [−0.13, 3.23] | 0.08 | −0.03 [−1.21, 1.15] | 0.96 |

| PO2 | 10 mm Hg | 0.05 [−0.03, 0.12] | 0.22 | 0.01 [−0.05, 0.07] | 0.76 |

| PCO2 | 10 mm Hg | −1.54 [−2.85, −0.22] | 0.04 | 0.35 [−0.66, 1.35] | 0.49 |

DISCUSSION

The use of glucose meters in critically ill patients remains controversial. A number of variables including hematocrit, PO2, PCO2, pH, and medications may interfere with or impact the accuracy of glucose meters9,29–31. The accuracy of capillary (fingerstick) glucose measurement in critically ill patients is of even greater concern; as previous studies have demonstrated potentially dangerous discrepancies in capillary glucose measurement in patients on vasopressor therapy10,17, patients in shock18 or with poor tissue perfusion19, and other critically ill patient populations20. Studies have also found that systematic (mean or median) glucose meter bias differs for capillary glucose meter samples compared to arterial or venous whole blood samples10,27,32.

Many of the studies demonstrating limitations to glucose meters were performed with older glucose meter technologies that did not correct for hematocrit or other interferences. Newer meter technologies may provide more accurate glucose measurement12–14 when used on critically ill patients, though studies have not specifically addressed capillary sampling or use of meters intraoperatively. One previous study33 specifically examined glucose measurements in the OR, although few patients were under anesthesia at the time of sample collection. Their data suggests that performance of glucose meters in the OR could be much worse than in the intensive care unit. That study compared glucose meter and central laboratory measurements that were collected within 5 minutes of each other, using both arterial and venous blood samples.

We found that median bias did not differ between capillary and arterial blood specimens tested using the blood glucose meter. Outliers (glucose meter value >20% different from reference) were also rare with both capillary and arterial glucose meter samples. Thus, we observed improved accuracy of glucose meter measurement compared to previous reports, especially for capillary whole blood glucose. It is important to interpret studies of glucose meter accuracy in the context of the generation and type of meter technology used. For both capillary and arterial samples, 100% of values were within Zones A and B on the Parkes error grid for Type I Diabetes, indicating excellent clinical concordance between glucose meter and reference glucose values for subcutaneous insulin dosing. We conclude that improved accuracy (reduced systematic bias and number/percent of outliers) allows for safe subcutaneous insulin dosing in the OR using both capillary and arterial samples on the glucose meter.

The glucose meter accuracy required for more intensive glycemic control protocols remains controversial. We assessed glucose meter accuracy for more intensive glycemic control protocols using the CLSI POCT12-A3 guidelines. Whereas Parkes Error grid analysis was developed to reflect accuracy required for self-monitoring of blood glucose (subcutaneous insulin dosing), CLSI POCT12-A3 guidelines were developed to reflect accuracy requirements for various uses of glucose meters in the acute care environment. Specifically, the CLSI guidelines comment on required accuracy for intravenous insulin glycemic control protocols26. Compared to glucose correction using subcutaneous insulin, glycemic control protocols using intravenous insulin increase the rate of hypoglycemia in the intensive care unit up to 5-fold34. Error simulation models suggest that glucose meters that exceed 10–15% total error allow for large insulin dosing errors (those most likely to result in hypoglycemia) during intravenous insulin therapy using common protocols35–37. Finally both error simulation models and empiric data demonstrate that as glucose meter error increases above 10–15%, there is a decrease in the efficacy of glycemic control (increased rate of hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia, increased glycemic variability) during intravenous insulin infusion38,39. These and other justifications have been used to define more stringent accuracy requirements for use of glucose meters for intravenous insulin infusion in the acute care setting.

Three hundred forty-four of 368 (93%) of arterial whole blood glucose values met CLSI POCT12-A3 guidelines. Thus with arterial samples the glucose meter just failed to meet CLSI POCT12-A3 accuracy requirements (95%). Only 368 (89%) of capillary whole blood glucose measurements met these same accuracy requirements. The large number of glucose meter measurements that underestimated true glucose by > 12.5% would be expected to impact glycemic control efficacy (rates of hyperglycemia and glycemic variability) in the context of intravenous glycemic control protocols. Thus caution should be exercised when using glucose meters for this purpose intraoperatively, and capillary sampling is best avoided when using meters for more intensive glycemic control protocols.

A secondary aim of our study was to identify clinical and laboratory variables associated with glucose meter bias and/or outliers. We found a statistically significant relationship between disease severity (age-adjusted Charlson comorbidity index) and capillary glucose meter bias, though the magnitude of this effect was small. Partial pressure of carbon dioxide also had a statistically significant but small impact on capillary glucose bias. For arterial glucose meter samples, only mean diastolic blood pressure in the 15 minutes prior to sampling was associated with glucose meter bias, but again the magnitude of this effect was small. Patient position, time under general anesthesia (early vs. late measurement), diabetes status, and other clinical and laboratory variables were not significantly associated with glucose meter bias. Likely because we observed less systematic bias and fewer outliers compared to previous studies, we were not able to identify clinical or laboratory variables that had a major effect on glucose meter performance.

The StatStrip device FDA labeling cautions against use of capillary samples for some intensively treated patients, but does not specify exactly which patients should not have capillary sampling performed. The FDA has not given glucose meter manufacturers clear guidance on the number of different patient populations (surgical, surgical ICU, medical ICU, etc.) or number of patients that should be evaluated to determine the effectiveness of capillary glucose sampling for intensively treated patients. Accuracy criteria have also not been clearly defined by FDA, though criteria close to those defined in CLSI POCT12-A3 have been suggested.

Patients in the OR share many characteristics with other intensively treated patient populations, including acute physiologic alterations to blood pressure, PO2, PCO2, pH that are associated with glucose meter error. Surgical patients often receive vasopressors and other intravenous fluids and medications commonly used among critically ill or intensively treated patients. These factors, along with the paucity of published data on intraoperative glucose meter accuracy, make it unclear whether capillary sampling is appropriate in the OR. Many patients in our study received vasopressor therapy and patients had a wide range of comorbidities (age-adjusted Charlson risk score) (Table 1). The results of this study will therefore help users evaluate the safety and efficacy of capillary sampling for either subcutaneous or intravenous insulin dosing during surgery. The results may also prove useful for glucose meter manufacturers in demonstrating the accuracy of capillary glucose meter testing in one intensively treated patient population.

Our study was limited in that we only studied adult patients during thoracic, vascular, and neurologic surgery, and studied only a single capillary sampling site (finger). Patients were selected for the study based upon availability of an arterial catheter for sampling, rather than a specific comorbidity or condition associated with glucose meter inaccuracy. In addition, no patients had hypoglycemia (reference glucose < 70 mg/dL). We have observed similar bias for glucose values < 70 mg/dL in previous studies using this device37. All patients were under general anesthesia at the time of capillary sampling, which may have led to more accurate capillary glucose measurement due to the vasodilating effects of general anesthesia. Finally, we tested only one point of care glucose meter model. The results obtained in this study may not be generalizable to all glucose meters, especially older technologies. Further studies are necessary to determine whether glucose meter accuracy may differ in other types of surgery or other acute care patient populations such as patients in intensive care units.

Conclusion

Median bias for arterial whole blood glucose meter samples collected intraoperatively was – 5 mg/dL, which did not differ from median bias of −4 mg/dL for capillary glucose meter samples. In contrast to findings of previous studies that used older glucose meter technologies, we found that neither the systematic (median) bias nor the number/percent of outlier results differed between capillary and arterial glucose meter samples. One hundred percent of both capillary and arterial glucose values were within Zones A and B on the Parkes error grid for Type I diabetes, demonstrating that both capillary and arterial whole blood glucose can be used to safely dose subcutaneous insulin in the OR. Neither arterial nor capillary whole blood glucose met CSLI POCT12-A3 guidelines, suggesting that caution must be exercised when using glucose meter values for intravenous or more intensive glycemic control protocols.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge Mayo Clinic Anesthesia Clinical Research Unit study coordinators Mr. Wayne Weber and Ms. Melissa Passe for their help with data extraction, Ms. Man Li, Ms. Lavonne M. Liedl, and the staff of the Mayo Clinic Anesthesia Clinical Research Unit for their efforts in identifying, recruiting, and consenting participants, Ms. Sarah Wolhart for help in preparing the protocol, and the staff of the Mayo Clinic Clinical Research and Trials Unit for performing point-of-care measurements.

Footnotes

Clinical trial number: This study did not involve assignment of patients to treatment groups and therefore did not require registry as a clinical trial.

Disclosure of funding: This project was supported by Grant Number UL1 TR000135 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), the Mayo Clinic Department of Laboratory Medicine and Pathology, and the Mayo Clinic Department of Anesthesiology.

Conflicts of interest: Brad S. Karon has received travel support from Nova Biomedical Corporation.

REFERECNES

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Accessed December 17, 2015];2014 National Diabetes Statistics Report. http://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/data/statistics/2014statisticsreport.html.

- 2.NICE-SUGAR Study Investigators. Intensive versus conventional glucose control in critically ill patients. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1283–1297. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0810625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lewis K, Kane-Gill S, Bobek M, Dasta J. Intensive insulin therapy in critically ill patients. Ann Pharmacother. 2004;38:1243–51. doi: 10.1345/aph.1D211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Van den Berghe G, Wouters P, Weekers F, Verwaest C, Bruyninckx F, Schietz M, Vlasselaers D, Ferdinande P, Lauwers P, Bouillon R. Intensive insulin therapy in critically ill patients. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:1359–67. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa011300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kwon S, Thompson R, Dellinger P, Yanez D, Farrohki E, Flum D. Importance of perioperative glycemic control in general surgery: a report from the Surgical Care and Outcomes Assessment Program. Ann Surg. 2013;257:8–14. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31827b6bbc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Krinsley J, Grover A. Severe hypoglycemia in critically ill patients: Risk factors and outcomes. Crit Care Med. 2007;35:2262–7. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000282073.98414.4B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dhatariya K, Levy N, Kilvert A, Watson B, Cousins D, Flanagan D, Hilton L, Jairam C, Leyden K, Lipp A, Lobo D, Sinclair-Hammersley M, Rayman G. NHS Diabetes guideline for the perioperative management of the adult patient with diabetes. Diabet Med. 2012;29 doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2012.03582.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Joshi G, Chung F, Vann M, Ahmad S, Gan T, Goulson D, Merrill D, Twersky R. Society for Ambulatory Anesthesia consensus statement on perioperative blood glucose management in diabetic patients undergoing ambulatory surgery. Anesth Analg. 2010;111:1378–87. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e3181f9c288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Karon B, Griesmann L, Scott R, Bryant S, DuBois J, Shirey T, Presti S, Santrach P. Evaluation of the impact of hematocrit and other interference on the accuracy of hospital-based glucose meters. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2008;10:111–20. doi: 10.1089/dia.2007.0257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kanji S, Buffie J, Hutton B, Bunting P, Singh A, McDonald K, Fergusson D, McIntyre L, Hebert P. Reliability of point-of-care testing for glucose measurement in critically ill adults. Crit Care Med. 2005;33:2778–85. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000189939.10881.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Khan A, Vasquez Y, Gray J, Wians F, Kroll M. The variability of results between point-of-care testing glucose meters and the central laboratory analyzer. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2006;130:1527–32. doi: 10.5858/2006-130-1527-TVORBP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Karon B, Blanshan C, Deobald G, Wockenfus A. Retrospective evaluation of the accuracy of Roche AccuChek Inform and Nova StatStrip glucose meters when used on critically ill patients. Diabetes Tech Therap. 2014;16:828–32. doi: 10.1089/dia.2014.0074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Louie R, Curtis C, Toffaletti J, Handel E, Slingerland R, Fokkert M, Muller W, Weinert S, Lee D, Kotagiri S. Performance evaluation of a glucose monitoring system for point-of-care testing with the critically ill patient population. Point of Care. 2015;14:37–41. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mitsios J, Ashby L, Haverstick D, Bruns D, Scott M. Analytical evaluation of a new glucose meter system in 15 different critical care settings. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2013;7:1282–1287. doi: 10.1177/193229681300700518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dungan K, Chapman J, Braithwaite S, Buse J. Glucose measurement: Confounding issues in setting targets for inpatient management. Diabetes Care. 2007;30:403–9. doi: 10.2337/dc06-1679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Scott M, Bruns D, Boyd J, Sacks D. Tight glucose control in the intensive care unit: Are glucose meters up to the task? Clin Chem. 2008;55:18–20. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2008.117291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ellis M, Benjamin K, Cornell M, Decker K, Farrell D, McGugan L, Porter G, Shearin H, Zhao Y, Granger B. Suitability of capillary blood glucose analysis in patients receiving vasopresors. Am J Crit Care. 2013;22:423–30. doi: 10.4037/ajcc2013692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sylvain H, Pokorny M, English S, Benson N, Whitley T, Ferenczy C, Harrison J. Accuracy of fingerstick glucose values in shock patients. Am J Crit Care. 1995;4:44–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Desachy A, Vuagant A, Ghazali A, Baudin O, Longuet O, Calvat S, Gissot V. Accuracy of bedside glucometry in critically ill patients: Influence of clinical characteristics and perfusion index. Mayo Clin Proc. 2008;83:400–405. doi: 10.4065/83.4.400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Critchell C, Savarese V, Callahan A, Aboud C, Jabbour S, Marik P. Accuracy of bedside capillary glucose measurements in critically ill patients. Intensive Care Med. 2007;33:2079–84. doi: 10.1007/s00134-007-0835-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rice M, Pitkin A, Coursin D. Review article: glucose measurement in the operating room: more complicated than it seems. Anesth Analg. 2010;110:1056–65. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e3181cc07de. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Herasevich V, Kor D, Li M, Pickering B. ICU data mart: a non-iT approach. A team of clinicians, researchers and informatics personnel at the Mayo Clinic have taken a homegrown approach to building an ICU data mart. Healthc Inform. 2011;28:44–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Holtby H, Skowno J, Kor D, Flick R, Uezono S. New technologies in pediatric anesthesia. Paediatr Anaesth. 2012;22:952–61. doi: 10.1111/pan.12007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Parkes J, Slatin S, Pardo S, Ginsberg B. A new consensus error grid to evaluate the clinical significance of inaccuracies in the measurement of blood glucose. Diabetes Care. 2000;23:1143–8. doi: 10.2337/diacare.23.8.1143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Standardization IOf. In vitro diagnostic test systems-Requirements for blood glucose monitoring systems for self-testing in managing Diabetes Mellitus. Report Number ISO 15197 2003. 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 26.CLSI. Point of care blood glucose testing in acute and chronic care facilities: Approved guideline. 3. Wayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; 2013. CLSI Document POCT12- A3. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Karon B, Gandhi G, Nuttall G, Bryant S, Schaff H, McMahon M, Santrach P. Accuracy of Roche Accu-Chek Inform whole blood capillary, arterial, and venous glucose values in patients receiving intensive intravenous insulin therapy after cardiac surgery. Am J Clin Pathol. 2007;127:919–26. doi: 10.1309/6RFQCKAAJGKWB8M4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Charlson M, Szatrowski T, Peterson J, Gold J. Validation of a combined comorbidity index. J Clin Epidemiol. 1994;47:1245–51. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(94)90129-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tang Z, Du X, Louie R, Kost G. Effects of drugs on glucose measurement with handheld glucose meters and a portable glucose analyzer. Am J Clin Pathol. 2000;113:75–86. doi: 10.1309/QAW1-X5XW-BVRQ-5LKQ. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tang Z, Louie R, Lee J, Lee D, Miller E, GJK Oxygen effects on glucose meter measurements with glucose dehydrogenase- and oxidase-based strips for point-of-care testing. Crit Care Med. 2001;29:1062–70. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200105000-00038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Watkinson P, Barber V, Amira E, James T, Taylor R, Young J. The effects of precision, haematocrit, pH, and oxygen tension on point-of-care glucose measurements in critically ill patients: a prospective study. Ann Clin Biochem. 2012;49:144–151. doi: 10.1258/acb.2011.011162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Petersen J, Graves D, Tacker D, Okorodudu A, Mohammad A, Cardenas V. Comparison of POCT and central laboratory blood glucose results using arterial, capillary, and venous samples from MICU patients on a tight glycemic control protocol. Clin Chim Acta. 2008;396:10–3. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2008.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mraovic B, Schwenk E, Epstein R. Intraoperative accuracy of a point-of-care glucose meter compared with simultaneous central laboratory measurements. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2012;6:541–546. doi: 10.1177/193229681200600308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wiener B, Wiener D, Larson R. Benefits and risks of tight glucose control in critically ill adults. JAMA. 2008;300:933–944. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.8.933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Boyd J, Bruns D. Monte Carlo simulation in establishing analytical quality requirements for clinical laboratory tests. Methods Enzymol. 2009;467:411–33. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(09)67016-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Karon B, Boyd J, Klee G. Glucose meter performance criteria for tight glycemic control estimated by simulation modeling. Clin Chem. 2010;56:1091–1097. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2010.145367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Karon B, Boyd J, Klee G. Empiric validation of simulation models for estimating glucose meter performance criteria for moderate levels of glycemic control. Diabetes Tech Therap. 2013;15 doi: 10.1089/dia2013.0086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Boyd J, Bruns D. Effects of measurement frequency on analytical quality required for glucose measurement in intensive care units: assessments by simulation models. Clin Chem. 2014;60:644–650. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2013.216366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Karon B, Meeusen J, Bryant S. Impact of Glucose Meter Error on Glycemic Variability and Time in Target Range During Glycemic Control After Cardiovascular Surgery. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2016;10:336–42. doi: 10.1177/1932296815602099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]