The UN's millennium development goals on maternal and child health will not be met unless dozens of countries swiftly create national maternal and child health services with universal access, according to the World Health Organization's 2005 World Health Report.

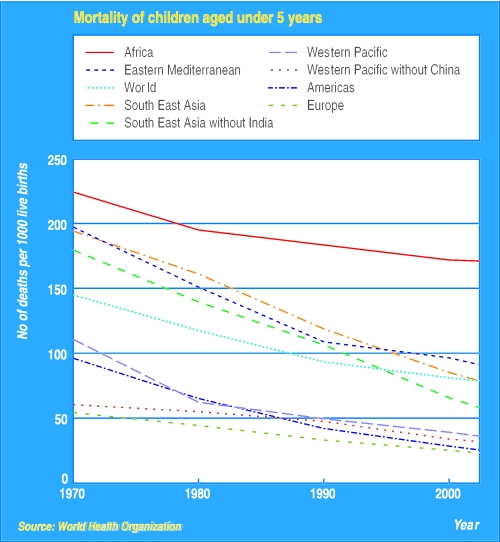

The report, which was published last week to coincide with world health day (7 April), estimates that each year 3.3 million babies are stillborn, more than four million die in their first month of life, and a further 6.6 million children die before the age of five years. The number of women dying each year as a result of pregnancy, abortion, or childbirth is more than half a million, including about 70 000 deaths caused by unsafe abortions.

WHO argues that the same formula used by European nations in the early 20th century to reduce maternal mortality has brought dramatic results in Thailand, Sri Lanka, Egypt, and Malaysia. These countries at least halved their maternal mortality in less than 10 years by training and certifying large numbers of midwives and backing them with well equipped regional hospitals.

“It is crucial that the whole package be available and on offer to all, immediately, at every childbirth,” conclude the report's authors. “Where universal access is not achieved, positive results are delayed. This explains why the USA lagged so far behind a number of northern European countries in the 1930s.”

Figure 1.

Dr Gudjón Magnússon, of WHO's programme for reducing disease burden, said: “The evidence shows that partial solutions cannot improve maternal and child health. Success is mainly due to the systematic strengthening of integrated health systems that provide care and support to every mother and child.”

The report found, however, that some of the poorest countries would have to more than double their healthcare budgets between now and 2015 to meet the twin millennium development goals of reducing mortality in children aged under five by two thirds and maternal mortality by three quarters from the 1990 levels.

WHO concludes that “reaching all children with a package of essential child health interventions necessary to comply with and even go beyond the MDGs [millennium development goals] is technically feasible within the next decade.”

But it will require an investment of $52.4bn (£28bn; €40bn) over current expenditure in the 75 countries with the highest child mortality. In the 21 countries with the poorest coverage, the report finds, “current public expenditure on health would have to grow by 27% as of 2006, rising to around 76% in 2015.”

Achieving universal access to maternal and neonatal care is no longer feasible by 2015, the report concludes, and the millennium development goal for maternal health is out of reach in some countries. But “realistic” scenarios could provide access to a full package of first level and back up care for 101 million mothers in 75 countries at a cost of about $39bn.

To meet this less ambitious goal in the 20 countries with the fewest perinatal services, public spending on health would have to increase by 43% over the next decade.

The World Health Report 2005: Make Every Mother and Child Count is available at www.who.int/whr/2005/en/index.html