Abstract

Background

In human cortical neural progenitor cells, we investigated the effects of propofol on calcium homeostasis in both the ryanodine and inositol 1, 4, 5-trisphosphate calcium release channels. We also studied propofol-mediated effects on autophagy, cell survival and neuro- and gliogenesis.

Methods

The dose response relationship between propofol concentration and duration was studied in NPCs. Cell viability was measured by 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide and lactate dehydrogenase release assays. The effects of propofol on cytosolic calcium concentration were evaluated using Fura-2 and autophagy activity was determined by LC3II expression levels with Western blot. Proliferation and differentiation were evaluated by bromodeoxyuridine incorporation and immunostaining with neuronal and glial markers.

Results

Propofol dose- and time-dependently induced cell damage and elevated LC3II expression, most robustly at 200 μM for 24 h (67±11% of control, n=12 to 19) and 6 h (2.4±0.5 compared with 0.6±0.1 of control, n=7), respectively. Treatment with 200 μM propofol also increased cytosolic calcium concentration (346±71% of control, n=22 to 34). Propofol at 10 μM stimulated NPC proliferation and promoted neuronal cell fate, while propofol at 200 μM impaired neuronal proliferation and promoted glial cell fate (n=12 to 20). Co-treatment with ryanodine and inositol 1, 4, 5-trisphosphate receptor antagonists and inhibitors, cytosolic Ca2+ chelators, or autophagy inhibitors mostly mitigated the propofol-mediated effects on survival, proliferation and differentiation.

Conclusions

These results suggest that propofol-mediated cell survival or neurogenesis is closely associated with propofol’s effects on autophagy by activation of ryanodine and inositol 1, 4, 5-trisphosphate receptors.

Keywords: Autophagy, Propofol, Dantrolene, Anesthetics, Calcium, Neurodegeneration, Stem cells, Neurogenesis, Cell proliferation

Introduction

Propofol, the most commonly used intravenous anesthetic agent, has been reported to cause brain cell degeneration1, as well as learning and behavior deficits2, in neonatal rodents. These studies have raised significant safety concerns over the administration of anesthetics in the pediatric population and we propose that propofol may regulate neurogenesis when administered early in life. Neural progenitor cells (NPCs), which are plentiful in the postnatal developing rodent brain, are capable of differentiating into neurons and glial cells and provide a promising cell model to probe the underlying mechanisms governing anesthetic-induced neurotoxicity. Previous studies, testing the administration of isoflurane, have identified neuronal apoptosis in immature neurons3 but not in NPCs.4,5 However, changes in both proliferation and differentiation of NPCs were identified.4,5 It remains unknown whether propofol has the same effect on NPCs as isoflurane. The aim of this study is to determine propofol’s effects on, and the role of, autophagy activity in cortical-derived NPC viability, proliferation and differentiation.

Materials and Methods

NPC cultures

ReNcell CX cells, an immortalized human NPC line obtained from human fetal cortex (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA), were cultured following the manufacturer’s protocol. For all experiments, cells frozen between passages 6 and 15 were thawed and resuspended in laminin-coated (Sigma-Aldrich, Saint Louis, Missouri) T75 cm2 tissue culture flasks in ReNcell NSC Maintenance Medium (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA). To ensure that the cells remained in a proliferative state, 20 ng/ml of fibroblast growth factor-basic (bFGF) (Sigma-Aldrich, Saint Louis, Missouri) and epidermal growth factor (EGF) (Millipore, Billerica, MA) were added to the medium. The cell cultures were maintained in an incubator at 37°C, 95% humidity, and 5% CO2. Culture medium was replaced every 24 h. Differentiation was induced by withdrawal of both growth factors (bFGF and EGF) at a confluence of approximately 70%.

Determination of Cytotoxicity

MTT (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (Sigma-Aldrich, Saint Louis, MO) reduction assays were used to measure the cellular redox activity, a relatively early cell damage indicator. The assay measured the activity of mitochondrial dehydrogenase, which reduces MTT to formazan. MTT (0.5 mg/ml) was added to the growth medium in 96-well plates and incubated with NPCs for 4 h at 37°C. Formazan was solubilized from the medium in 150μl dimethyl sulfoxide and the optical density measured at 540 nm (Synergy™ H1 microplate reader, BioTek, Winooski, VT). An LDH (lactate dehydrogenase) release assay (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL) was used to quantify disruption of membrane integrity, an indicator of later stage cell damage, as described previously,6 by measuring lactate dehydrogenase released by the cells into the medium. Briefly, 50 μl of the medium was added to 96- well plates with the reaction mixture for 30 min at room temperature. The reaction was stopped and the mixture solution measured at 490nm and 680nm (Synergy™ H1 microplate reader, BioTek, Winooski, VT). Background signal of the medium was deducted from control signals. The mean signal was determined from 6–10 wells per condition from 3–4 separate cultures for each condition (n=18). The data were presented as a percentage of vehicle control.

Cell Proliferation Assays

ReNcell CX cells were plated onto laminin-coated coverslips for 4 hours in the proliferation medium containing the growth factors (see NPC cultures above). BrdU, 5-Bromodeoxyuridine (Invitrogen, Eugene, OR) at a concentration of 10μM was mixed with the medium 24h before the end of the propofol treatment. Then, the cells were fixed (4% paraformaldehyde) and permeabilized (0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS). The cells then underwent acid treatment (1N HCL on ice for 10 min followed by 2N HCL at room temperature for 10 min) which separated the DNA into single strands so that the primary antibody could detect the BrdU. After incubation with blocking serum (1% bovine serum and 10% goat serum in PBS), the cells were incubated overnight with rat monoclonal anti-BrdU primary antibody (1:100) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX) at 4°C. The cells were washed (0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS) and BrdU detected with fluorescently labeled secondary antibody conjugated with anti-rat IgG (1:1,000 for 2h) (Invitrogen, Eugene, OR). The immunostained cells were mounted on microscope slides with Prolong Gold Antifade Reagent containing DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole, Invitrogen, Eugene, OR) for visualization of cell nuclei. The cells were imaged on an Olympus BX41TF fluorescence microscope (200×; Olympus USA, Center Valley, PA) equipped with iVision v10.10.5 software (Biovision Technologies, Exton, PA). The number of DAPI-labeled cells and the number of BrdU-labeled cells were counted, and the mean number of cells calculated from 5 random areas of each coverslip, with 5–10 cover slips per condition, from 3–4 different cultures. The experimental n equals the number of coverslips. The data were expressed as the percentage of the number of BrdU-positive cells to the total number of cells.

Cell Differentiation Assays

ReNcell CX cells were initially cultured with the same proliferation medium containing growth factors (see NPC Cultures) until just before the differentiation experiments, when the medium was replaced with medium devoid of growth factors. After the propofol treatment, the cells were allowed to differentiate for an additional three days, fixed (4% formaldehyde), and processed for immunocytochemistry overnight at 4°C using mouse monoclonal antibody reactive to the neuronal marker, Tuj1 (1:200) (Covance, Princeton, NJ) or rabbit polyclonal antibody reactive to astrocytes, glial fibrillary acidic protein GFAP (1:1,500) (Millipore, Billerica, MA). Thereafter, cells were incubated with Alexa-594 goat anti-mouse (1:1,000) and Alexa-488 goat anti-rabbit IgG antibodies (1:1,000) (Invitrogen, Eugene, OR) at room temperature for 1 h to visualize the primary antibody signal. The slides with immunostained cells were coverslipped with Prolong Gold Antifade Reagent containing DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole) to visualize cell nuclei, examined on an Olympus BX41TF fluorescence microscope (200×; Olympus USA, Center Valley, PA), and images acquired using iVision v10.10.5 software (Biovision Technologies, Exton, PA). Tuj1- or GFAP-positive cells overlapping with DAPI signal were analyzed at ten random locations on each slide. The number of DAPI-labeled cells and the number of Tuj1- or GFAP-positive cells were counted, and the mean number of Tuj1- or GFAP positive cells calculated for each slide and the mean determined for 3 slides per condition. The n equals the number of slides. The data were expressed as the percentage of the number of Tuj1- or GFAP-positive cells to the total number of cells.

Western Blot Analysis

A 6-well cell culture plate on ice was washed once with ice-cold PBS. After aspiration of PBS, 100μl ice-cold lysis buffer (1% Triton X-100, 150 mM NaCl and 50 mM Tris–HCl) was added to each well and maintained on ice for 5 min. The homogenate was collected with a cell scraper and then centrifuged at 4°C in a microcentrifuge at 10,000g for 30 min. The supernatant was gently collected and preserved at -70 °C for future use. BCA assay determined the protein concentration with a BCA kit (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL). For electrophoresis, 25 to 30 μg of protein from different samples were loaded on 15% SDS-PAGE (sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis) gels, run with a constant current, and then the protein transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (BIO-RAD, Hercules, CA) using a wet transfer system (BIO-RAD, Hercules, CA). The membranes were blocked with 5% non-fat dry milk dissolved in phosphate-buffered saline with 0.2% Tween-20 (PBST) for 1 h at room temperature, and incubated overnight at 4°C with the primary rabbit monoclonal antibody against LC3 (1:1,000) (Cell Signaling Technology, Boston, MA), or primary mouse monoclonal antibody against β-actin (1:3,000) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX). This was followed by a wash with secondary antibody conjugated with anti-rabbit and anti-mouse IgG conjugated with horseradish peroxidase (1:10,000) (BIO-RAD, Hercules, CA) at room temperature for 1 h. The protein on the membranes was detected in a Kodak Image Station 4000MM Pro (Kodak, Rochester, NY) ECL Prime Western Blotting Detection Reagent (GE Healthcare, Buckinghamshire, UK) and images were acquired with Carestream imaging software v5.3.4 (Carestream Health, New Haven, CT). Signal intensity was quantitatively analyzed with ImageJ v1.49 software (https://imagej.nih.gov/ij/download.html) and the β-actin loading control was used for normalization. The n equals the number of wells for each condition.

Measurement Cytosolic Ca2+ Concentration

The NPC cytosolic Ca2+ concentrations ([Ca2+]c) were measured by Fura-2 AM fluorescence (Invitrogen, Eugene, OR) on an Olympus IX70 inverted system microscope (Olympus USA, Center Valley, PA) equipped with a photometer and IPLab v3.71 software (Scientific Instrument Company, Campbell, CA), as previously described.6 Briefly, NPCs were plated onto a 35mm laminin-coated culture dishes for 4 h, washed 3 times in Ca2+-free Dulbecco’s modified eagle medium (DMEM, Gibco, Grand Island, NY), loaded with 2.5 μm Fura-2 AM in the same buffer at 37 °C for 30 min, then washed and incubated in Ca2+-free DMEM for another 30 min at 37 °C. The cells were exposed to propofol (200 μM) in least essential medium (MEM, Gibco, Grand Island, NY) and fluorescence intensities were determined by recording at 340 and 380 nm excitation and at 510 nm emission, for up to 5 min, for each treatment. Data were presented as a ratio of 340/380 nm of fluorescence intensity normalized to baseline. After each imaging experiment, the trypan blue exclusion assay was routinely used to ensure that the cells for [Ca2+]c measurements were healthy and living.

Dose selection of the pharmacological agents

The doses of dantrolene and xestospongin C used in this experiment were the same as those used in our previous study with the same cell line.6 In a pilot study, we conducted dose responses for BAPTA-AM and Baf-A1 (data not shown). The maximum concentration that did not induce cytotoxicity (5 μM and 400 nM respectively) was chosen for this study. The dose of lithium used (2 mM and 10 mM) was based on previous studies.7,8

Statistical Analysis

The statistical analyses were performed and graphs created using GraphPad Prism 6 software (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA). The sample sizes we used were based on previous publications6,9,10 One set of MTT and LDH data for the dose response was excluded for suspicious contamination. Parametric variables were expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) with a Gaussian distribution. Data were analyzed using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey multiple comparisons testing or two-way ANOVA using propofol concentration and exposure duration as the between-group factors followed by the Bonferroni multiple comparisons test, as detailed in the figure legends. Results were considered statistically significant with P < 0.05, based on two-tailed analysis.

Results

Propofol induces neural progenitor cell cytotoxicity through excessive autophagy by over-activation of InsP3 and/or ryanodine receptors

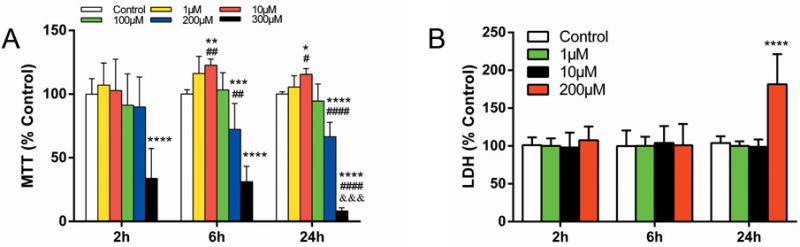

ReNcell CX NPCs were exposed to different concentrations of propofol (1 to 300 μM), for 2, 6, or 24 h. MTT assays determined that treatment with 10 μM propofol, a clinically relevant concentration, increased cell viability after the 6 h and 24 h exposures. On the contrary, propofol at 200 or 300 μM for the same duration (6 h and 24 h) decreased cell viability, while 100 μM propofol had no effect on cell survival throughout the experiment (Fig. 1A). However, LDH assays showed significant cytotoxicity was only observed with the 200 μM propofol treatment for 24 h, indicating late stage cell death (Fig. 1B). Our results suggested that the concentration and exposure duration of propofol were the determining factors for the survival of ReNcell CX NPCs.

Figure 1. Propofol induces neural progenitor cell cytotoxicity in a time- and dose-dependent manner.

ReNcell CX human neural progenitor cells (NPCs) were exposed to different concentrations of propofol (1 to 300 μM) for 2, 6 or 24 h. (A) The MTT (3-(4, 5-dimethyithiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl-tetrazolium bromide) reduction assay was used to determine relatively early cell damage. Treatment with 10 μM propofol increased while 200 μM propofol decreased cell viability after 6h and 24h exposures. 300μM propofol induced remarkable cell damage at all three time points relative to vehicle control. ## P < 0.01, #### P < 0.0001 compared with treatment for 2 h with the same concentration; &&& P < 0.001 compared with treatment for 6h; * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001, **** P < 0.0001, compared with vehicle controls at corresponding time points (n=19 at 2 h; n=12 at 6 h; n=17 at 24 h). (B) Relatively late cell damage was determined by lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) release assay. Only 200 μM propofol treatment for 24 h exhibited significant cell damage (**** P < 0.0001 compared with vehicle controls, n=18). All data are expressed as the mean ± SD from at least three separate experiments with duplicates or triplicates and analyzed by two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey multiple comparison tests.

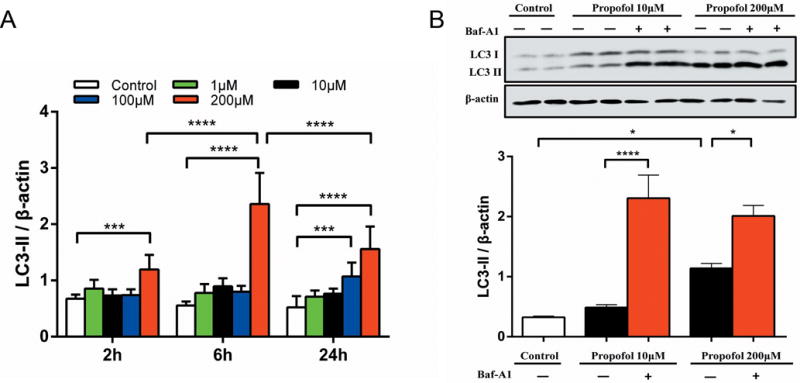

Previous studies suggested that propofol impacted cellular biology through an autophagy-involved regulatory mechanism.11,12 In this study, we proposed that autophagy plays a role in the cytotoxicity induced by propofol. Western blots showed a time- and concentration-dependent increase in the level of the autophagy biomarker, LC3II, during propofol treatment, peaking at 24 h with 100 μM and at 6 h with 200μM propofol (Fig. 2A). However, exposure to 10 μM propofol, a clinically relevant concentration, did not show a significant difference in LC3II (Fig. 2A) in ReNcell CX NPCs. In order to differentiate between the induction of autophagy from the impairment of autophagy flux, bafilomycin was added to the culture media at 22 h of the 24 h propofol exposure period. Further increases in the LC3II level after the bafilomycin treatment indicated the induction of autophagy by propofol (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2. Propofol induced autophagy in neural progenitor cells.

ReNcell CX human neural progenitor cells (NPCs) were exposed to propofol concentrations ranging from 1–200 μM for 2, 6 or 24 h. (A) Quantitative analysis of Western blots of the autophagy biomarker, LC3II. The LC3-II/β-actin ratio showed that 200 μM propofol increased the levels of LC3-II at exposure durations at all time points (n=7). (B) A representative immunoblot of LC3II from three separate experiments from NPCs cultured with 10 μM or 200 μM propofol for 24 h and the densitometric analysis of the LC3II/β-actin ratio. Further increases in the LC3II level after bafilomycin (Baf-A1; 400 nM) treatment indicated induction of autophagy by propofol (n=6). All bar graphs presented as mean ± SD from three separate experiments with duplicate samples, and analyzed by two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey multiple comparison tests. *P < 0.05, *** P < 0.001 or **** P < 0.0001 compared with corresponding time control or as indicated.

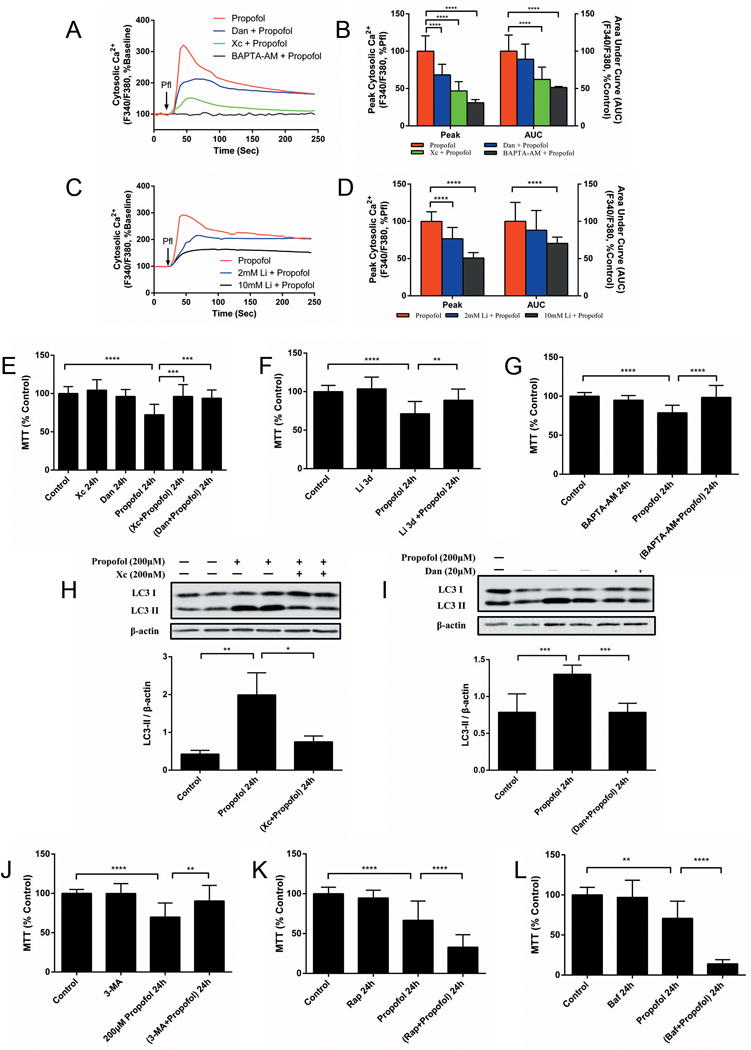

Previously, we detected that isoflurane induced ReNcell CX cytotoxicity by Ca2+ release from the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) through inositol 1, 4, 5-trisphosphate (InsP3) and/or ryanodine (RYR) receptors.6 To evaluate the role of Ca2+ release from InsP3 and RYR receptors may have in the propofol-mediated cytotoxicity, the intracellular Ca2+ concentrations were measured after propofol treatments in the presence of, the InsP3R antagonist, xestospongin C, the ryanodine receptor antagonist, dantrolene, the intracellular Ca2+ chelator, BAPTA-AM, or the InsP3 production inhibitor, lithium. Propofol alone induced a greater elevation in the cytosolic Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]c) than in the presence of Xc, dantrolene or BAPTA-AM (Fig. 3A, B). Pre-treatment with 2 mM or 10 mM lithium significantly decreased the peak amplitudes and area under curve (AUC) of propofol-evoked [Ca2+]c signals (Fig. 3C, D). These results suggested that propofol possibly increased the [Ca2+]c by Ca2+ release from the InsP3 or RYR receptors into the ER. Thus, we propose that the cytotoxicity induced by propofol was mediated by these ER membrane receptors’ excessive release of calcium into the cytosol. The MTT reduction assays showed that co-treatment with Xc, dantrolene, BAPTA-AM, or lithium inhibited ReNcell CX cell damage induced by 200 μM propofol for 24 h (Fig. 3E–G).

Figure 3. Propofol induces neural progenitor cell damage through excessive autophagy by InsP3 and/or ryanodine receptors.

(A) Average calcium response to 200 μM propofol (arrow) in NPCs cultured in normal medium or medium pretreated with 200 nm of the InsP3 receptor antagonist, xestospongin C (Xc), 20 μM of the ryanodine receptor antagonist, dantrolene (Dan) or 5 μM of the intracellular calcium chelator, BAPTA-AM. Changes in Fura-2 AM intensities from at least fifteen single cells in three separate experiments were measured to assess the F340/F380 ratio, a representative indicator for the cytosolic calcium concentration ([Ca2+]c). The F340/F380 ratios were normalized to baseline. (B) Pre-treatment with Xc, Dan or BAPTA-AM decreased the peak amplitudes and the areas under the curve (AUC) of the propofol-evoked [Ca2+]c signals. **** P < 0.0001 compared with propofol administration alone. (C) Average calcium response to 200 μM propofol (arrow) in NPCs cultured in normal medium or medium pretreated with InsP3 production inhibitor lithium (Li; 2 mM or 10 mM). (D) Pre-treatment of 2 mM or 10 mM Li significantly decreased the peak amplitudes and AUC of propofol-evoked [Ca2+]c signals. **** P < 0.0001 compared with propofol administration alone. Cell viability, determined with the MTT (3-(4,5-dimethyithiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl-tetrazolium bromide) reduction assay, detected inhibition of cell damage induced by 200 μM propofol for 24 h (E) after co-treatment with Xc and Dan, and (F) pre-treatment with Li for 3 days, and (G) co-treatment with BAPTA-AM. The data (E-F) are expressed as the mean ± SD from at least three separate experiments and analyzed by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey multiple comparison tests. ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001, or **** P < 0.0001, respectively. (H) A representative immunoblot of LC3II of three separate experiments from cells cultured with 200 μM propofol for 24 h with or without Xc, (I) Dan and the quantitative analysis of LC3II/β-actin ratio (mean ± SD). Co-treatment with Xc or Dan alleviated the propofol-induced elevation in the autophagy biomarker, LC3II. (J) Similarly, the NPC cytotoxicity induced by 200μM propofol for 24 h, was mitigated by co-treatment with 5nM of the autophagy inhibitor, 3-methyladenine (3-MA). Co-treatment with (K) autophagy inducer, rapamycin (Rap; 100 nM), or (L) autophagy flux inhibitor, bafilomycin (Baf; 1nM), promoted NPC damage induced by 200 μM propofol for 24 h. The data (I–J) are expressed as the mean ± SD from at least three separate experiments, and analyzed by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey multiple comparison tests. ** P < 0.01, **** P < 0.0001.

We further questioned whether InsP3Rs and/or RYRs were also involved in the induction of autophagy flux stimulated by propofol. Blockage of InsP3Rs or RYRs significantly alleviated propofol-induced elevation of the autophagy biomarker LC3II (fig.3 H, I). ReNcell CX cell damage induced by 200 μM propofol for 24 h was mitigated by co-treatment with autophagy inhibitor 3-methyladenine and promoted by co-treatment with the autophagy inducer, rapamycin, or the autophagy flux inhibitor, bafilomycin (Fig. 3J–L), meaning that excessive autophagy activity was associated with propofol-induced cell damage - which may have resulted in type II autophagic cell death.13

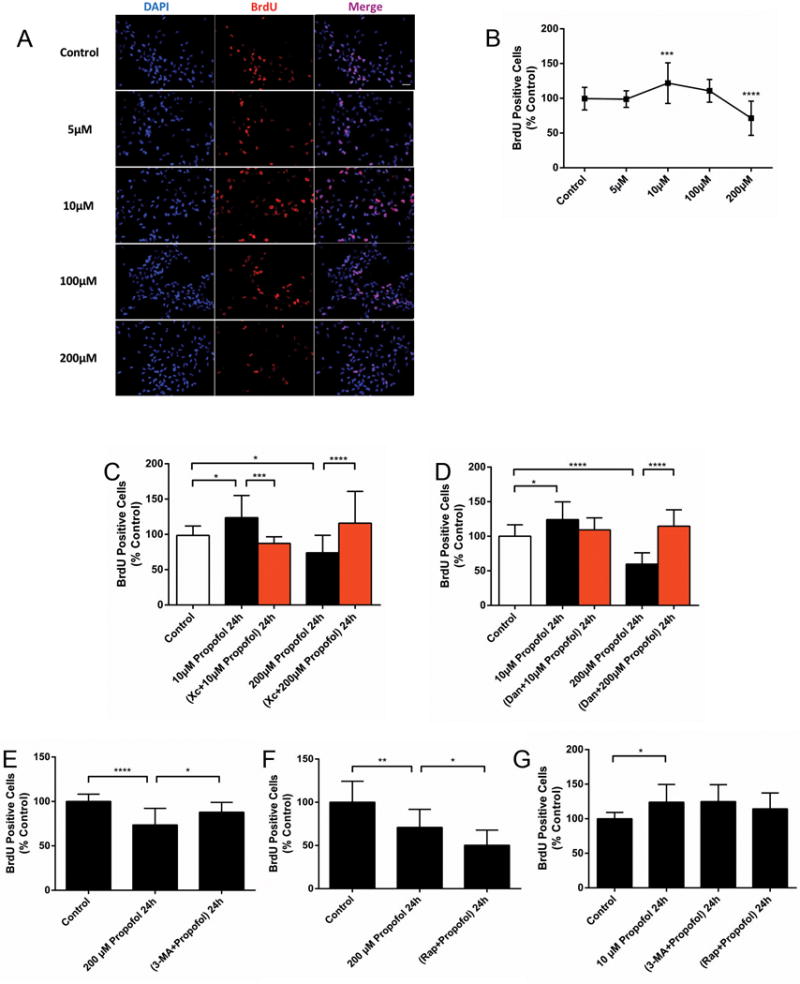

Propofol affects proliferation in neural progenitor cells and regulation of autophagy

As autophagy is involved in differentiation and development,14,15 we investigated whether autophagy plays a role in the effects of propofol on proliferation. The impact of propofol on the proliferation of ReNcell NPCs was assessed at various concentrations and exposure times. Compared with control cells, exposure to the clinical concentration of propofol (10 μM) for 24 h promoted cell proliferation, while 200 μM propofol treatment significantly decreased proliferation (Fig. 4A, B). Interestingly, co-treatment with xestospongin C or dantrolene alleviated the dual effects of propofol on NPC proliferation, except for the dantrolene treatment with 10 μM propofol (Fig. 4C, D). These results suggest that the dual effects of propofol on cell proliferation is mediated by calcium released from the ER, while the distinctly opposing impact of differing concentration may be due to the amount of calcium released. Propofol at 200 μM for 24h significantly impaired proliferation, but this could be inhibited by autophagy inhibitor, 3-methyladenine (3-MA), and potentiated by autophagy inducer, rapamycin (Fig. 4E, F). However, co-treatment with 3-MA or rapamycin had no effect on the 10 μM propofol-induced proliferation increase (Fig. 4G). These results suggest that suppression of proliferation induced by propofol at 200 μM for 24 h was related to increased autophagy activity, whereas the clinical concentration of propofol accelerated cell proliferation via a non-autophagy mechanism.

Figure 4. Propofol affects neural progenitor cell proliferation and regulation of autophagy.

(A) Representative images showing the double immunostaining of cell nuclei with DAPI (blue, arrows) and 5-bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU, red, arrows) in ReNcell CX neural progenitor cells (NPCs) with or without propofol (10, 200 μM) for 24 h. Scale bar = 50 μm. (B) Quantitative analysis of the effect of a 24 h exposure to 10 μM or 200 μM propofol on the proliferation of BrdU-positive NPCs. Exposure to 10 μM propofol increased the percent of BrdU-positive cells, while 200 μM propofol resulted in significantly decreased proliferation (n=30). (C) Quantitative analysis of the effect of a 24 h exposure to 10 μM or 200 μM propofol on the proliferation of BrdU-positive NPCs, with or without the InsP3 receptor antagonist, xestospongin C (Xc; 50 nm), or (D) the ryanodine receptor antagonist, dantrolene (Dan, 1 μM). Co-treatment with Xc (n=20) or Dan (n=14) alleviated the dual effects of propofol on NPC proliferation. (E) Quantitative analysis of the effect of a 24 h exposure to 10 μM or 200 μM propofol on the proliferation of BrdU-positive NPCs, with or without the autophagy inhibitor, 3-methyladenine (3-MA, 5mM), or the autophagy inducer, rapamycin (Rap; 100 nM). Propofol significantly impaired proliferation at 200 μM for 24h, which was inhibited by 3-MA (n=15) and (F) potentiated by Rap (n=15). (G) Co-treatment with 3-MA or Rap had no effect on 10 μM propofol-induced increase of proliferation (n=17). The above data are expressed as the mean ± SD from at least three separate experiments, and analyzed by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey multiple comparison tests. * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001, or **** P < 0.0001, compared with vehicle control or as indicated.

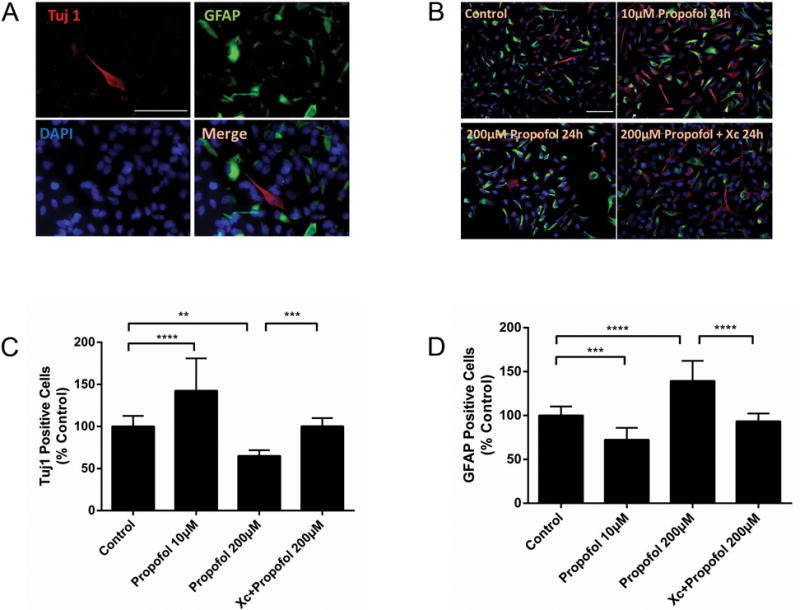

Propofol affects neural progenitor cell differentiation via activation of InsP3Rs

Exposure to 10 μM propofol for 24 h promoted neuronal fate as measured by the increase in Tuj1-positive cells and suppressed glial fate as determined by the decrease of GFAP-positive cells (Fig. 5A, B). On the contrary, 200 μM propofol decreased the percent of Tuj1-positive cells and increased GFAP-positive cells, indicating an enhancement of glial fate. Consistent with propofol’s effects on cytotoxicity and proliferation, co-treatment with the InsP3R antagonist, xestospongin C, mitigates these dual effects of propofol, suggesting the prominent role of InsP3Rs in these processes (Fig. 5C, D).

Figure 5. Propofol affects neural progenitor cell differentiation via InsP3 receptors.

(A) Representative micrographs showing immunostaining for Tuj1, neuronal class III β-tubulin (red), GFAP, glial fibrillary acidic protein (green), and DAPI (blue) of ReNcell neural progenitor cells (NPCs) cultured in differentiation medium for 3 days. (B) Representative micrographs showing immunostaining of Tuj1 (red), GFAP (green) and DAPI (blue) of NPCs cultured with 10 μM or 200 μM propofol, with or without the InsP3 receptor antagonist, xestospongin C (Xc; 50 nm), followed by differentiation medium for 3 days. (C) Tuj1-positive or (D) GFAP-positive cells were counted and the data expressed as a percentage of controls. Propofol, at 10 μM, increased Tuj1-positive neuronal cells but decreased the GFAP-positive glial cells. Propofol 200 μM had the opposite effects of deceasing Tuj1-positive cells and increasing GFAP-positive cells. These effects could be mitigated by co-treatment with Xc. Scale bar = 50 μm. The data are expressed as the mean ± SD and analyzed by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey multiple comparison tests. ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001 or **** P < 0.0001.

Discussion

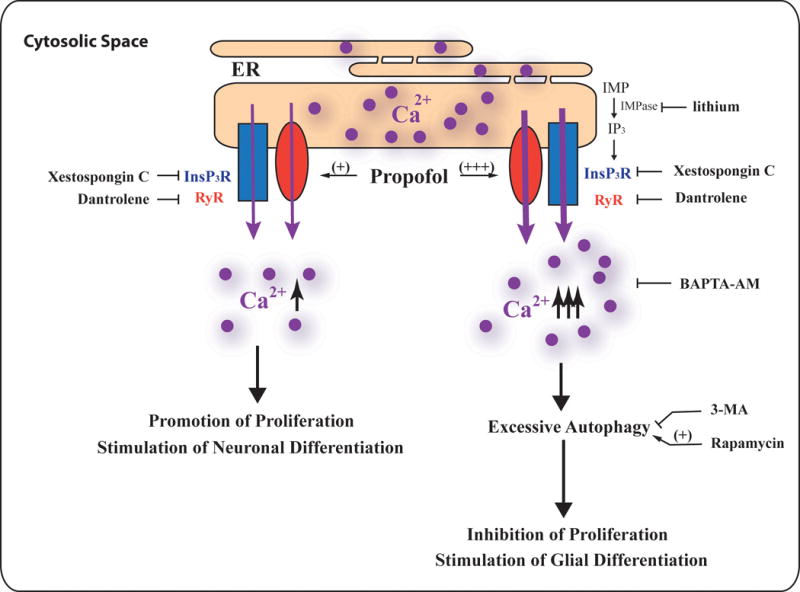

This study examined the effects of propofol on human cortex-derived neural progenitor cells and the role of calcium-mediated autophagy pathway in neurogenesis and neurodegeneration. We found that propofol induced Ca2+ release from the endoplasmic reticulum of NPCs by activation of the InsP3R and/or RYR. A clinically relevant dose of propofol promoted cell proliferation and favored neuronal cell fate via adequate activation of the InsP3R and adequate autophagy. However, a high dose of propofol induced cell damage and favored glial cell fate through excessive autophagy by over-activation of InsP3Rs and RYRs.

Previous studies have shown that propofol can induce both excitotoxic and apoptotic cell death16 in cell cultures17,18 and in animal models19,20, although the mechanism is not clear. Most of the previous studies have focused on the anesthetic-induced type 1 cell death (apoptosis),21,22 but cells can also die from type 2 (autophagic cell death) or type 3 cell death (necrosis). Palanisamy et al.23 recently demonstrated that propofol, at approximately 15 and 30 μM, for a 4 h exposure, did not induce rat primary NPC necrotic cell death and apoptosis. However, prolonged use of propofol for 24 h transiently impaired proliferation. Consistent with these results, we detected significant NPC cytotoxicity at an extremely high pharmacological concentration (200 μM) but not at clinically relevant concentrations (1, 10 μM). In contrast, propofol, at 10 μM for 24 h, in this study, promoted NPC proliferation while propofol, at about 15 μM (2.5 μg/ml), transiently impaired rat primary NPC proliferation in the previous study.23 The discrepancy between these two studies is likely due to the different types of cells, primary vs. immortalized NPCs. Future studies in rat primary NPCs at clinically relevant concentrations will be needed to sort out these differences.

There is a consensus that autophagy is required for cell survival and is involved in various physiological events, including immune responses, cancer, aging and neurodegeneration,24,25 as well as brain development and differentiation.14,15,26 A recent study has shown that knockdown of the of the autophagy-related gene Atg5 inhibited cortical NPC differentiation but increased proliferation during embryonic brain development.27 The exact role of autophagy during neurogenesis, as well as the consequences of pharmacological stresses, such as anesthetics, on autophagy are unclear.

Like most anesthetics including pentobarbital, ketamine, and isoflurane, propofol exhibited up-regulation of autophagy in skeletal muscles28 and human umbilical vein endothelial cells.11 This dose-dependent stimulatory effect of propofol on autophagy flux was also observed in our experiments. To implicate autophagy as a possible contribution to neurogenesis, an autophagy inducer or inhibitor was applied together with propofol. As confirmed by MTT and proliferation assays, cell damage or decreased proliferation correlated with excessive induction of autophagy flux by propofol exposure. Consistent with our results, autophagy is believed to be a double-edged sword in ischemia and preconditioning.29 Physiological autophagy eliminates harmful protein aggregates and damaged organelles in cells and thus limits the transmission of harmful signaling; excessive or pathological autophagy, however, induces type II autophagy cell death and causes irreversible injury.

We also explored changes in cytosolic calcium concentrations [Ca2+]c as a possible mechanism for our observed effects. Previously, propofol has been reported to increased [Ca2+]c in glia, neurons30 and neural stem/progenitor cells31 and that an increase in [Ca2+]c within the physiological range promotes cell proliferation, differentiation, synthesis and catabolism.32 Similarly, we found that [Ca2+]c almost tripled after propofol treatment and we posit that propofol initiated a Ca2+-dependent signaling pathway.

The γ-aminobutyric acid type A (GABAA) receptor is one of the likely targets for propofol. Previous research has shown that activation of GABAA receptors by isoflurane during brain development may cause cell membrane depolarization, Ca2+ influx through voltage dependent Ca2+ channels, and increased [Ca2+]c.33 Recently, InsP3Rs have been implicated as a molecular target for isoflurane and to be involved in anesthetic-mediated neurotoxicity.10 The InsP3Rs and RYRs are the main channels through which Ca2+ leaves the ER, though a small amount of Ca2+ leaves the ER through the so-called leak channel. The increase in the [Ca2+]c after isoflurane administration in mature neurons was caused primarily by calcium release from intracellular stores, most likely from the ER. Therefore, we propose that the mechanism of propofol’s impact on neurogenesis on NPCs is InsP3R activation, followed by a rise in the [Ca2+]c, and finally either the induction or an over-activation of autophagy, depending on the amount of Ca2+ released (Fig. 6). Indeed, we found that InsP3R inhibition prevented most of the effects of propofol on cell viability, autophagy, proliferation and differentiation. Although the mechanisms underlying these observed results by propofol in human cortical NPCs are not fully apparent, our results suggest the involvement of InsP3Rs and RYRs. Since the mitochondria and the ER have intracellular communication sites, they may also regulate Ca2+ homeostasis by uptake of calcium released by the ER,34 especially when intracellular calcium concentrations are high, such as after exposures to anesthetics. A previous study35 demonstrated that mitochondrial Ca2+ concentrations are increased after isoflurane-mediated Ca2+ release from the ER via activation of InsP3R, followed by transfer into mitochondria. It is important that future studies investigate whether propofol has similar effects, because mitochondria play important roles in ATP production and autophagy regulation.36

Figure 6. Summary of the effects of propofol on NPC proliferation and differentiation.

Exposure to a clinically relevant concentration of propofol induces calcium release from the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) through the activation of the calcium channels, inositol-1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors (InsP3R) and/or ryanodine receptors (RyR). This results in a moderate increase in the concentration of cytosolic calcium that stimulates neuronal progenitor cell (NPC) proliferation and neuronal and glial cell differentiation. These effects involve a non-autophagy mechanism. On the other hand, a prolonged exposure, to a high concentration of propofol, induces the over-activation of InsP3Rs and/or RYRs on the ER membrane thereby allowing the buildup of intracellular Ca2+. This elevated concentration of cytosolic calcium leads to excessive autophagy and the inhibition of NPC proliferation, which contributes to the propofol-mediated neurotoxicity.

The outcome of either physiologic autophagy or pathological autophagy may be explained by InsP3Rs and intracellular Ca2+ signaling. While apparently contradictory, both autophagic flux37 and inhibition38 result from autolysosomal formation from an increase in autophagosomes to lysosomes. Our experimental data provide compelling evidence for both the propofol-mediated dose-dependent increase in [Ca2+]c and the subsequent induction of autophagy. The different outcomes of autophagy are possibly due to a divergent role of the InsP3R with respect to basal- versus stress- induced autophagy and the different spatio-temporal characteristics of Ca2+ signals that can be generated, each having distinct impacts on different steps in the autophagy pathway.

There is evidence, from in vitro39 and in vivo40 studies, that lithium, a common drug for the treatment of neuropsychiatric disorders, has facilitated neurogenesis and reduced the neurotoxicity induced by certain stressors, including anesthetics.41 It has been proposed that the mechanism for the neuroprotective properties of lithium result from its interactions with cell survival and cell death pathways. Lithium can affect intracellular Ca2+ homeostasis by inhibiting N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor-mediated Ca2+ entry into the cell, as well as reducing InsP3 production by inhibiting inositol monophosphatase. Lithium can also affect autophagy via its regulation of intracellular Ca2+ homeostasis,42 inhibition of GSK-3β and activation of the inhibitory regulator mTOR.43 Thus, the effects of lithium observed in our experiment may be explained by its effects on the regulation of calcium homeostasis and the associated autophagy process. In addition, lithium may affect propofol’s effects due to their mutual interaction at the voltage-gated Na+ channel, as both have been demonstrated to affect these Na+ channels.44 Thus the effects of lithium appear to outweigh the effects of propofol at lower concentrations than at higher anesthetic concentrations.

Propofol exposure during the period of rapid brain development in neonatal animals has negatively impacted hippocampal structure and function, resulting in subsequent cognitive impairment.2,45 The mechanisms for propofol’s deleterious effects during development are conflicting, including interference with neural stem cell function, neurogenesis, and synapse formation.46,47 Such controversy may be due to confounding variables in the use of animal models.48,49 In an attempt to reduce such variables, we chose to study neural progenitor cells in vitro. Our results suggested that at clinically relevant concentrations of propofol, proliferation contributed more to the increased cell viability than differentiation. Although increased cell viability may also be due to suppressed apoptosis, a previous study indicated that apoptosis was not a major factor associated with improved viability when neural stem cells were treated with propofol.9 Propofol administration is generally considered to be excitotoxic neurodegeneration, which is fundamentally different, both in type and sequence, from that of the apoptotic phenomenon.16 Propofol toxicity was only observed at concentrations that exceeded clinically relevant concentrations. Corresponding with previous results, propofol, at clinical concentrations, increased neural progenitor cell differentiation into neurons50 whereas differentiation into astrocytes was decreased.51

When interpreting the data presented in our study, some limitations must be considered. Our investigations into the mechanisms of the propofol induced changes on calcium homeostasis and autophagy, and thus NPC fate, were not exhaustive. Recent studies indicated enhanced CREB phosphorylation may play a role in the Ca2+-mediated pathway9 and in both proliferation and differentiation of neural stem cells.52 Furthermore, the protective effect of xenon preconditioning for asphyxia is thought to involve pCREB-regulated protein synthesis in rat brain.53 Downstream signaling after CREB activation may be the key to direct stem cell fate and further study is required to elucidate the mechanisms.

In conclusion, only extreme, high pharmacological concentrations of propofol adversely affect NPC cell viability in vitro by excessive autophagy through a Ca2+-mediated pathway. Clinically relevant doses of propofol enhance proliferation of NPCs and increase neuronal differentiation by a Ca2+-related non-autophagic mechanism.

Acknowledgments

We appreciate the valuable discussions and support from Roderic G. Eckenhoff, MD, Maryellen F. Eckenhoff, PhD, and Lee A. Fleisher, MD at the Department of Anesthesiology and Critical Care, University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine, Philadelphia, PA 19104, USA.

Source of Financial Support: This work was supported by National Institute of General Medical Science, National Institute of Health, Baltimore, Maryland, R01 NIH to HW (K08-GM073224, R01GM084979, 3R01GM084979-02S1, 2R01GM084979-06A1), and March of Dimes Birth Defects Foundation Research Grant (#12-FY08-167 to H.W.), White Plains, New York, and the bridging fund from the Department of Anaesthesiology, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: All authors declare no competing financial interest.

Abstract of this research work was presented at the Society for Neuroscience annual meeting in Nov 14, 2016 at San Diego, CA.

References

- 1.Milanovic D, Popic J, Pesic V, Loncarevic-Vasiljkovic N, Kanazir S, Jevtovic-Todorovic V, Ruzdijic S. Regional and temporal profiles of calpain and caspase-3 activities in postnatal rat brain following repeated propofol administration. Dev Neurosci. 2010;32:288–301. doi: 10.1159/000316970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Karen T, Schlager GW, Bendix I, Sifringer M, Herrmann R, Pantazis C, Enot D, Keller M, Kerner T, Felderhoff-Mueser U. Effect of propofol in the immature rat brain on short- and long-term neurodevelopmental outcome. PLoS One. 2013;8:e64480. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0064480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Istaphanous GK, Howard J, Nan X, Hughes EA, McCann JC, McAuliffe JJ, Danzer SC, Loepke AW. Comparison of the neuroapoptotic properties of equipotent anesthetic concentrations of desflurane, isoflurane, or sevoflurane in neonatal mice. Anesthesiology. 2011;114:578–87. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3182084a70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sall JW, Stratmann G, Leong J, McKleroy W, Mason D, Shenoy S, Pleasure SJ, Bickler PE. Isoflurane inhibits growth but does not cause cell death in hippocampal neural precursor cells grown in culture. Anesthesiology. 2009;110:826–33. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e31819b62e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Culley DJ, Boyd JD, Palanisamy A, Xie Z, Kojima K, Vacanti CA, Tanzi RE, Crosby G. Isoflurane decreases self-renewal capacity of rat cultured neural stem cells. Anesthesiology. 2011;115:754–63. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e318223b78b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhao X, Yang Z, Liang G, Wu Z, Peng Y, Joseph DJ, Inan S, Wei H. Dual effects of isoflurane on proliferation, differentiation, and survival in human neuroprogenitor cells. Anesthesiology. 2013;118:537–49. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3182833fae. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bosche B, Schafer M, Graf R, Hartel FV, Schafer U, Noll T. Lithium prevents early cytosolic calcium increase and secondary injurious calcium overload in glycolytically inhibited endothelial cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2013;434:268–72. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2013.03.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.De-Paula VJ, Kerr DS, de Carvalho MP, Schaeffer EL, Talib LL, Gattaz WF, Forlenza OV. Long-Term Lithium Treatment Increases cPLA(2) and iPLA(2) Activity in Cultured Cortical and Hippocampal Neurons. Molecules. 2015;20:19878–85. doi: 10.3390/molecules201119663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tao T, Zhao Z, Hao L, Gu M, Chen L, Tang J. Propofol promotes proliferation of cultured adult rat hippocampal neural stem cells. J Neurosurg Anesthesiol. 2013;25:299–305. doi: 10.1097/ANA.0b013e31828baa93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Joseph JD, Peng Y, Mak DO, Cheung KH, Vais H, Foskett JK, Wei H. General anesthetic isoflurane modulates inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor calcium channel opening. Anesthesiology. 2014;121:528–37. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000000316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chang CY, Chen PH, Lu SC, Hsieh MC, Lin CW, Lee HM, Jawan B, Kao YH. Propofol-enhanced autophagy increases motility and angiogenic capacity of cultured human umbilical vascular endothelial cells. Life Sci. 2015;142:49–59. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2015.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cui DR, Wang L, Jiang W, Qi AH, Zhou QH, Zhang XL. Propofol prevents cerebral ischemia-triggered autophagy activation and cell death in the rat hippocampus through the NF-kappaB/p53 signaling pathway. Neuroscience. 2013;246:117–32. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2013.04.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Green DR, Llambi F. Cell Death Signaling. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2015;7 doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a006080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhao Y, Huang Q, Yang J, Lou M, Wang A, Dong J, Qin Z, Zhang T. Autophagy impairment inhibits differentiation of glioma stem/progenitor cells. Brain Res. 2010;1313:250–8. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vazquez P, Arroba AI, Cecconi F, de la Rosa EJ, Boya P, de Pablo F. Atg5 and Ambra1 differentially modulate neurogenesis in neural stem cells. Autophagy. 2012;8:187–99. doi: 10.4161/auto.8.2.18535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ishimaru MJ, Ikonomidou C, Tenkova TI, Der TC, Dikranian K, Sesma MA, Olney JW. Distinguishing excitotoxic from apoptotic neurodegeneration in the developing rat brain. J Comp Neurol. 1999;408:461–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Luo T, Wu J, Kabadi SV, Sabirzhanov B, Guanciale K, Hanscom M, Faden J, Cardiff K, Bengson CJ, Faden AI. Propofol limits microglial activation after experimental brain trauma through inhibition of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidase. Anesthesiology. 2013;119:1370–88. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000000020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pearn ML, Hu Y, Niesman IR, Patel HH, Drummond JC, Roth DM, Akassoglou K, Patel PM, Head BP. Propofol neurotoxicity is mediated by p75 neurotrophin receptor activation. Anesthesiology. 2012;116:352–61. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e318242a48c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yang B, Liang G, Khojasteh S, Wu Z, Yang W, Joseph D, Wei H. Comparison of neurodegeneration and cognitive impairment in neonatal mice exposed to propofol or isoflurane. PLoS One. 2014;9:e99171. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0099171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Creeley C, Dikranian K, Dissen G, Martin L, Olney J, Brambrink A. Propofol-induced apoptosis of neurones and oligodendrocytes in fetal and neonatal rhesus macaque brain. Br J Anaesth. 2013;110(Suppl 1):i29–38. doi: 10.1093/bja/aet173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Peng J, Drobish JK, Liang G, Wu Z, Liu C, Joseph DJ, Abdou H, Eckenhoff MF, Wei H. Anesthetic preconditioning inhibits isoflurane-mediated apoptosis in the developing rat brain. Anesth Analg. 2014;119:939–46. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000000380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brambrink AM, Back SA, Riddle A, Gong X, Moravec MD, Dissen GA, Creeley CE, Dikranian KT, Olney JW. Isoflurane-induced apoptosis of oligodendrocytes in the neonatal primate brain. Ann Neurol. 2012;72:525–35. doi: 10.1002/ana.23652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Palanisamy A, Friese MB, Cotran E, Moller L, Boyd JD, Crosby G, Culley DJ. Prolonged Treatment with Propofol Transiently Impairs Proliferation but Not Survival of Rat Neural Progenitor Cells In Vitro. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0158058. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0158058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Levine B, Kroemer G. Autophagy in the pathogenesis of disease. Cell. 2008;132:27–42. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.12.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mizushima N, Levine B. Autophagy in mammalian development and differentiation. Nat Cell Biol. 2010;12:823–30. doi: 10.1038/ncb0910-823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Boya P, Mellen MA, de la Rosa EJ. How autophagy is related to programmed cell death during the development of the nervous system. Biochem Soc Trans. 2008;36:813–7. doi: 10.1042/BST0360813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lv X, Jiang H, Li B, Liang Q, Wang S, Zhao Q, Jiao J. The crucial role of Atg5 in cortical neurogenesis during early brain development. Sci Rep. 2014;4:6010. doi: 10.1038/srep06010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kashiwagi A, Hosokawa S, Maeyama Y, Ueki R, Kaneki M, Martyn JA, Yasuhara S. Anesthesia with Disuse Leads to Autophagy Up-regulation in the Skeletal Muscle. Anesthesiology. 2015;122:1075–83. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000000561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sheng R, Qin ZH. The divergent roles of autophagy in ischemia and preconditioning. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2015;36:411–20. doi: 10.1038/aps.2014.151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kahraman S, Zup SL, McCarthy MM, Fiskum G. GABAergic mechanism of propofol toxicity in immature neurons. J Neurosurg Anesthesiol. 2008;20:233–40. doi: 10.1097/ANA.0b013e31817ec34d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tozuka Y, Fukuda S, Namba T, Seki T, Hisatsune T. GABAergic excitation promotes neuronal differentiation in adult hippocampal progenitor cells. Neuron. 2005;47:803–15. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rushton DJ, Mattis VB, Svendsen CN, Allen ND, Kemp PJ. Stimulation of GABA-induced Ca2+ influx enhances maturation of human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived neurons. PLoS One. 2013;8:e81031. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0081031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhao YL, Xiang Q, Shi QY, Li SY, Tan L, Wang JT, Jin XG, Luo AL. GABAergic excitotoxicity injury of the immature hippocampal pyramidal neurons’ exposure to isoflurane. Anesth Analg. 2011;113:1152–60. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e318230b3fd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.De Stefani D, Raffaello A, Teardo E, Szabo I, Rizzuto R. A forty-kilodalton protein of the inner membrane is the mitochondrial calcium uniporter. Nature. 2011;476:336–40. doi: 10.1038/nature10230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yang H, Liang G, Hawkins BJ, Madesh M, Pierwola A, Wei H. Inhalational anesthetics induce cell damage by disruption of intracellular calcium homeostasis with different potencies. Anesthesiology. 2008;109:243–50. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e31817f5c47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cardenas C, Miller RA, Smith I, Bui T, Molgo J, Muller M, Vais H, Cheung KH, Yang J, Parker I, Thompson CB, Birnbaum MJ, Hallows KR, Foskett JK. Essential regulation of cell bioenergetics by constitutive InsP3 receptor Ca2+ transfer to mitochondria. Cell. 2010;142:270–83. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Decuypere JP, Parys JB, Bultynck G. ITPRs/inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors in autophagy: From enemy to ally. Autophagy. 2015;11:1944–8. doi: 10.1080/15548627.2015.1083666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Decuypere JP, Bultynck G, Parys JB. A dual role for Ca(2+) in autophagy regulation. Cell Calcium. 2011;50:242–50. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2011.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hashimoto R, Senatorov V, Kanai H, Leeds P, Chuang DM. Lithium stimulates progenitor proliferation in cultured brain neurons. Neuroscience. 2003;117:55–61. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(02)00577-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bianchi P, Ciani E, Contestabile A, Guidi S, Bartesaghi R. Lithium restores neurogenesis in the subventricular zone of the Ts65Dn mouse, a model for Down syndrome. Brain Pathol. 2010;20:106–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2008.00246.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Straiko MM, Young C, Cattano D, Creeley CE, Wang H, Smith DJ, Johnson SA, Li ES, Olney JW. Lithium protects against anesthesia-induced developmental neuroapoptosis. Anesthesiology. 2009;110:862–8. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e31819b5eab. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chiu CT, Chuang DM. Molecular actions and therapeutic potential of lithium in preclinical and clinical studies of CNS disorders. Pharmacol Ther. 2010;128:281–304. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2010.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sarkar S, Perlstein EO, Imarisio S, Pineau S, Cordenier A, Maglathlin RL, Webster JA, Lewis TA, O’Kane CJ, Schreiber SL, Rubinsztein DC. Small molecules enhance autophagy and reduce toxicity in Huntington’s disease models. Nat Chem Biol. 2007;3:331–8. doi: 10.1038/nchembio883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sibarov DA, Abushik PA, Poguzhelskaya EE, Bolshakov KV, Antonov SM. Inhibition of Plasma Membrane Na/Ca-Exchanger by KB-R7943 or Lithium Reveals Its Role in Ca-Dependent N-methyl-d-aspartate Receptor Inactivation. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2015;355:484–95. doi: 10.1124/jpet.115.227173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kargaran P, Lenglet S, Montecucco F, Mach F, Copin JC, Vutskits L. Impact of propofol anaesthesia on cytokine expression profiles in the developing rat brain: a randomised placebo-controlled experimental in-vivo study. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2015;32:336–45. doi: 10.1097/EJA.0000000000000128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sall JW, Stratmann G, Leong J, McKleroy W, Mason D, Shenoy S, Pleasure SJ, Bickler PE. Isoflurane inhibits growth but does not cause cell death in hippocampal neural precursor cells grown in culture. Anesthesiology. 2009;110:826–33. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e31819b62e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stratmann G, Sall JW, May LD, Bell JS, Magnusson KR, Rau V, Visrodia KH, Alvi RS, Ku B, Lee MT, Dai R. Isoflurane differentially affects neurogenesis and long-term neurocognitive function in 60-day-old and 7-day-old rats. Anesthesiology. 2009;110:834–48. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e31819c463d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lasarzik I, Winkelheide U, Stallmann S, Orth C, Schneider A, Tresch A, Werner C, Engelhard K. Assessment of postischemic neurogenesis in rats with cerebral ischemia and propofol anesthesia. Anesthesiology. 2009;110:529–37. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e318195b4fe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Huang J, Jing S, Chen X, Bao X, Du Z, Li H, Yang T, Fan X. Propofol Administration During Early Postnatal Life Suppresses Hippocampal Neurogenesis. Mol Neurobiol. 2016;53:1031–44. doi: 10.1007/s12035-014-9052-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sall JW, Stratmann G, Leong J, Woodward E, Bickler PE. Propofol at clinically relevant concentrations increases neuronal differentiation but is not toxic to hippocampal neural precursor cells in vitro. Anesthesiology. 2012;117:1080–90. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e31826f8d86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Li Q, Lu J, Wang X. Propofol and remifentanil at moderate and high concentrations affect proliferation and differentiation of neural stem/progenitor cells. Neural Regen Res. 2014;9:2002–7. doi: 10.4103/1673-5374.145384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Miyamoto N, Tanaka R, Zhang N, Shimura H, Onodera M, Mochizuki H, Hattori N, Urabe T. Crucial role for Ser133-phosphorylated form of cyclic AMP-responsive element binding protein signaling in the differentiation and survival of neural progenitors under chronic cerebral hypoperfusion. Neuroscience. 2009;162:525–36. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ma D, Hossain M, Pettet GK, Luo Y, Lim T, Akimov S, Sanders RD, Franks NP, Maze M. Xenon preconditioning reduces brain damage from neonatal asphyxia in rats. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2006;26:199–208. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]