Summary

Interval-censored competing risks data arise when each study subject may experience an event or failure from one of several causes and the failure time is not observed directly but rather is known to lie in an interval between two examinations. We formulate the effects of possibly time-varying (external) covariates on the cumulative incidence or sub-distribution function of competing risks (i.e., the marginal probability of failure from a specific cause) through a broad class of semiparametric regression models that captures both proportional and non-proportional hazards structures for the sub-distribution. We allow each subject to have an arbitrary number of examinations and accommodate missing information on the cause of failure. We consider nonparametric maximum likelihood estimation and devise a fast and stable EM-type algorithm for its computation. We then establish the consistency, asymptotic normality, and semiparametric efficiency of the resulting estimators for the regression parameters by appealing to modern empirical process theory. In addition, we show through extensive simulation studies that the proposed methods perform well in realistic situations. Finally, we provide an application to a study on HIV-1 infection with different viral subtypes.

Keywords: Cumulative incidence, Interval censoring, Nonparametric maximum likelihood estimation, Self-consistency algorithm, Time-varying covariates, Transformation models

1. Introduction

In clinical and epidemiological studies, the event of interest is often asymptomatic, such that the event time or failure time cannot be exactly observed but is rather known to lie in an interval between two examination times. An additional complication arises when there are several distinct causes or types of failure. The resulting data are referred to as interval-censored competing risks data. Such data are commonly encountered in HIV/AIDS research, where seroconversion with different HIV-1 viral subtypes is determined through periodic blood tests (Hudgens et al., 2001). Such data are also encountered in cancer clinical trials, where different types of adverse events may occur during reporting periods and the follow-up for each patient is terminated upon occurrence of any adverse event.

The distribution function of the failure time with competing risks can be decomposed into the sub-distribution functions of the constituent risks. The sub-distribution function, also known as the cumulative incidence, represents the cumulative probability of failure from a specific cause over time (Kalbfleisch and Prentice, 2002, §8.2). This quantity is clinically relevant because it characterizes the ultimate experience of the subject.

Several methods are available to make inference about the cumulative incidence with right-censored competing-risks data (e.g., Gray, 1988; Fine and Gray, 1999; Kalbfleisch and Pren-tice, 2002, §8.2; Martinussen and Scheike, 2006, Ch. 10; Mao and Lin, 2016). Because none of the failure times are observed exactly under interval censoring, it is much more challenging, both theoretically and computationally, to deal with interval-censored than right-censored data. The literature on the cumulative incidence for interval-censored competing risks data has focused on one-sample estimation. Specifically, Hudgens et al. (2001) adapted the self-consistency algorithm of Turnbull (1976) to compute the nonparametric maximum likelihood estimator (NPMLE). Jewell et al. (2003) studied the NPMLE and other estimators with current status data, where each subject is examined only once. Groeneboom et al. (2008a; 2008b) established rigorous asymptotic theory for the NPMLE with current status data. Li and Fine (2013) studied kernel-smoothed nonparametric estimation in current status data.

In this article, we consider a general class of semiparametric regression models for competing risks data with potentially time-varying (external) covariates. This class of models encompasses both proportional and non-proportional sub-distribution hazards structures. We study the NPMLEs for these models when there is a random sequence of examination times for each subject and the cause of failure information may be partially missing. We develop a fast and stable EM-type algorithm by extending the self-consistency formula of Turnbull (1976). We establish that, under mild conditions, the proposed estimators for the regression parameters are consistent and asymptotically normal. In addition, the estimators attain the semiparametric efficiency bound with a covariance matrix that can be consistently estimated by the profile likelihood method (Murphy and van der Vaart, 2000). The proofs involve careful use of modern empirical processes theory (van der Vaart and Wellner, 1996) and semiparametric efficiency theory (Bickel et al., 1993) to address unique challenges posed by the combination of interval censoring and competing risks. We evaluate the operating characteristics of the proposed numerical and inferential procedures through extensive simulation studies. Finally, we describe an application to a clinical study of HIV/AIDS, in which a cohort of injecting drug users was followed for evidence of seroconversion with HIV-1 viral subtypes B and E.

2. Methods

2.1 Data and Models

Suppose that T is a failure time with K competing risks or causes of failure. Let D ∈ {1, …, K} indicate the cause of failure, and let Z(·) denote a p-vector of possibly time-varying external covariates. We formulate the effects of Z on (T, D) through the conditional cumulative incidence or sub-distribution functions

Equivalently, we consider the conditional sub-distribution hazard function

which is the conditional hazard function for the improper random variable , where I(·) is the indicator function. It is easy to see that Fk(t; Z) = 1 − exp{−Λk(t; Z)}, where .

We adopt a class of semiparametric transformation models for each risk

| (1) |

where Gk(·) is a known increasing function, βk is a set of regression parameters, and Λk(·) is an arbitrary increasing function with Λk(0) = 0 (Mao and Lin, 2016). The choices of Gk(x) = x and Gk(x) = log(1 + x) correspond to the proportional hazards and proportional odds models, respectively, for the sub-distribution. When Z consists of only time-invariant covariates, equation (1) can be expressed in the form of a linear transformation model

where gk(·) is a known increasing function, and Qk(·) is an arbitrary increasing function (Cheng et al., 1995; Chen et al., 2002; Lu and Ying, 2004). The choices of gk(x) = log{−log(1−x)} and log{x/(1 − x)} yield the proportional hazards and proportional odds models, respectively.

We consider a general interval-censoring scheme under which each subject has an arbitrary sequence of examination times and the information on the cause of failure is possibly missing. Specifically, let U1 < U2 < … < UJ denote a random sequence of examination times, where J is a random integer. Define Δ = (Δ1, …, ΔJ)T, where Δj = I(Uj−1 < T ≤ Uj) (j = 1, …, J), and U0 = 0. Also, write D̃ = DI(Δ ≠ 0). In addition, let ξ indicate, by the values 1 versus 0, whether or not the cause of failure is observed. We set ξ = 1 if D̃ = 0. Then, the observed data for a random sample of n subjects consist of (Ji, Ui, Δi, ξi, ξiD̃i, Zi) (i = 1, …, n), where Ui = (Ui0, Ui1, …, Ui,Ji)T, and Δi = (Δi1, …, Δi,Ji)T.

2.2 Nonparametric Maximum Likelihood Estimation

Write and Λ = (Λ1, …, ΛK). We estimate β and Λ by the nonparametric maximum likelihood approach. Suppose that (T, D) is independent of (U, J) conditional on Z and that the cause of failure is missing at random (MAR). Then, the likelihood for (β, Λ) can be written as

where the first and second factors correspond to Fk(Uij; Zi) − Fk(Ui,j−1; Zi) and , respectively, and the last factor corresponds to the overall survival function . This likelihood is similar to that of the mixed-case censoring of Hudgens et al. (2014), but it pertains to semiparametric regression models instead of parametric distribution functions. Let (Li, Ri] denote the interval among (Ui0, Ui1], …, (Ui,Ji, ∞] that contains Ti. Then, the above likelihood can be written as

| (2) |

To maximize (2), we treat Λk as a right-continuous step function that jumps at the two ends of the intervals. Specifically, let tk1 < … < tk,mk denote the distinct values of Li and Ri with ξiD̃i = k or ξi = 0. In addition, let λkj denote the jump size of Λk at tkj, and let Zikj = Zi(tkj). Then, the likelihood given in (2) becomes

| (3) |

2.3 Numerical Algorithm

Direct maximization of (3) is difficult due to the high dimensionality of λkj. This task is further complicated by the fact that, unlike the right-censoring case, the maximizers for some λkj are zero and thus lie at the boundary of the parameter space. To overcome such difficulties in the univariate case, Turnbull (1972) proposed a self-consistency formula for computation of NPMLE, which is essentially an EM algorithm based on completely observed data. Herein, we propose a novel EM algorithm that extends Turnbull’s formula to regression analysis with competing risks.

Let Nk(u, v] denote the number of events of the kth type that occur in the interval (u, v]. For the ith subject with Ri < ∞, let sik1 < sik2 < … < sik,jik denote the distinct values of tkj in the interval (Li, Ri], such that the interval (Li, Ri] is partitioned into a sequence of sub-intervals (sik0, sik1], …, (sik,jik−1, sik,jik], where sik0 = Li. In the “complete data”, we know which sub-interval the failure time lies in, along with the cause of failure. That is, the complete data consist of the full paths of Nk(0, ·] (k = 1, ···, K), and the missing data are the unknown cause of failure and the precise location of each event within the observed interval. Then, the complete-data log-likelihood takes the form

where Nki denotes the counting process Nk for the ith subject, , Fk(t; Z, βk, Λk) = 1−exp{−Λk(t; Z)}, and ΔFk(t; Z, βk, Λk) is the jump size of Fk(·; Z, βk, Λk) at t.

In the M-step, we maximize

| (4) |

where ŵikj is the conditional probability that the ith subject experiences a failure of the kth cause in (sik,j−1, sikj] given the subject’s failure information. If ξiD̃i = k′, then

If ξi = 0, then

If Ri = ∞, then ŵikj = 0.

When maximizing (4), we update the parameters using a one-step self-consistency type formula. The first-order approximation to ΔFk(tkj; Z, βk, Λk) is , where . Here and in the sequel, f′(t) = df(t)/dt for any function f. Thus, the objective function in (4) can be approximated by

| (5) |

where mk is the total number of the tkj. We set the derivative of (5) with respect to λkj to zero to obtain an updating formula for λkj

To update β, we use a one-step Newton-Raphson algorithm based on (5).

We set the initial value of β to 0 and the initial value of λkj to n−1. We iterate between the E- and M-steps until the sum of the absolute differences of the parameter estimates between two successive iterations is less than a small number. To increase the chance of reaching the global maximum, we suggest using a range of initial values for β. The resulting estimators for β and Λ are denoted as β̂ and Λ̂, respectively.

The proposed algorithm has several desirable features. First, the conditional expectations in the E-step have simple analytic forms. Second, the M-step involves only a single analytic update for λkj and thus avoids large-scale optimization over high-dimensional parameters. Finally, the algorithm is applicable to any transformation model and time-varying covariates.

2.4 Asymptotic Properties

We show in the Web Appendix that, under mild regularity conditions, β̂ and Λ̂ are consistent, and n1/2(β̂ − β) is asymptotically zero-mean normal with a covariance matrix that attains the semiparametric efficiency bound in the sense of Bickel et al. (1993). The estimator Λ̂ is only n1/3-consistent, and its asymptotic distribution is unknown even in the univariate case (Huang and Wellner, 1997). Nonetheless, consistency alone allows one to predict the covariate-specific cumulative incidence.

Because Λ̂ is not -consistent, the variance of β̂ cannot be estimated by the familiar Louis formula. Thus, we appeal to the profile likelihood method (Murphy and van der Vaart, 2000). The profile likelihood for β is defined as

where 𝒞 is the space of Λ, in which Λk is a step function with non-negative jumps at tkj. We propose to estimate the covariance matrix of β̂ by the negative inverse of the matrix whose (j, k)th element is

where ej is the jth canonical vector in ℝd, hn is a constant of the order n−1/2, and p is the dimension of β. The consistency of this estimator follows from the profile likelihood theory of Murphy and van der Vaart (2000). To evaluate pln(β), we adopt the EM algorithm described in Section 2.2 by using Λ̂ as the initial value for Λ and holding β fixed in the iterations.

2.5 Reduced-Data Likelihood

We can estimate the parameters separately for each risk by using the reduced-data likelihood along the lines of Jewell et al. (2003) and Hudgens et al. (2014). Assume that there are no missing values on the causes of failure. In the reduced data, the subjects who experience the risk of interest and those who are right censored remain intact, whereas those who experience the other risks are treated as right censored at the last examination time UJ (Hudgens et al., 2014). For the kth risk, the reduced data consist of {Ji, Ui, I(D̃i = k) Δi, Zi} (i = 1, …, n), and the corresponding likelihood for (βk, Λk) is

which can be written as

| (6) |

We can maximize (6) by adapting the algorithm of Section 2.2. The resulting estimators are referred to as naive estimators.

With the exception of semiparametric efficiency, the asymptotic properties of the full-data NPMLEs carry over to the naive estimators by setting K = 1. The reason that efficiency is not attained by the naive estimators is because the reduced data do not contain all relevant information about the risk of interest. For example, the overall survival function, which combines the risk of interest with other risks in the full-data likelihood, is not included in the reduced-data likelihood.

In the reduced data for a particular risk, a subject who experiences a different risk is treated as right censored at the last potential examination time UJ. This examination time may be unknown if the available data consist only of (Li, Ri) (i = 1, …, n). It might be tempting to replace Ui,Ji in (6) by Ri if the ith subject experiences a different risk and Ui,Ji is unavailable. However, the corresponding likelihood would involve parameters for other risks, such that the resulting naive estimators would be biased.

We have assumed that ξi = 1 for all i = 1, …, n. When there are missing values on the causes of failure, it is natural to consider only complete cases, i.e., subjects with non-missing values. (Note that right-censored observations are complete cases because their causes of failure are naturally unknown.) The complete-case analysis, however, is generally biased. Suppose, for instance, that missingness is completely random among subjects who are not right censored. Since shorter failure times are less likely to be right censored than longer failure times and thus are more likely to be associated with missing causes and discarded, the cumulative incidence will be underestimated. If the probability of right censoring depends on covariates, then the naive estimator for the regression parameter will also be biased.

3. Simulation Studies

We carried out simulation studies to assess the performance of the NPMLE and naive methods in realistic settings. We let Z1(t) = B1I(t ≤ V) + B2I(t > V) and Z2 ~ Unif[0, 1], where B1 and B2 are independent Bernoulli(0.5), and V is Unif[0, 3]. In addition, we let U1 and U2 − U1 be two independent random variables distributed as the minimum of 1.5 and an exponential random variable with hazard e0.5Z2−0.5. We considered K = 2 and Gk(x) =r−1 log(1 + rx) with r = 0, 1, and 0.5. We set Λ1(t) = Λ2(t) = 0.1(1 − e−t), β1 = (0.25, −0.25)T, and β2 = (−0.25, 0.25)T. We first assumed that the causes of failure are completely observed. Under these conditions, the event rate for each cause was roughly 15%. We generated 10,000 replicates for each scenario. Convergence criteria were met when the sum of the absolute differences of all the parameter estimates between two successive iterations fell below 10−4. For both the NPMLE and the naive estimator, the algorithms converged in about 100 iterations. For variance estimation, we set hn = n−1/2. We also experimented with other values of hn, including 10n−1/2, and the results differed only at the third decimal place.

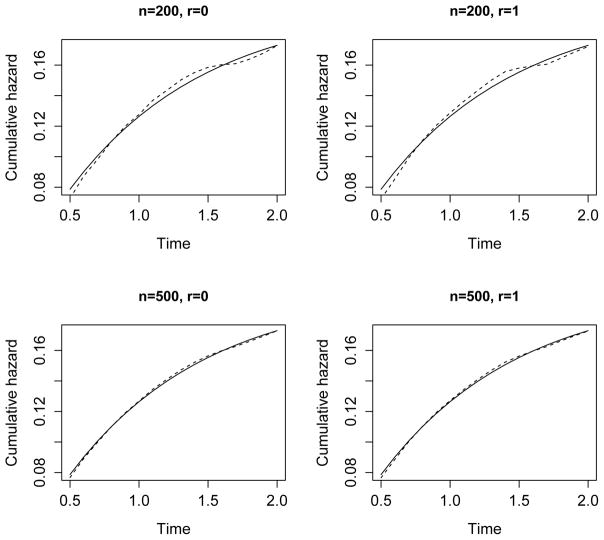

The results for β1 = (β11, β12)T are summarized in Table 1. For both the NPMLE and naive methods, the parameter estimators are virtually unbiased, and the standard error estimators reflect the true variability well. As a result, the empirical coverage probabilities of the confidence intervals are close to the nominal level. The NPMLE has smaller variance than the naive estimator. As shown in Figure 1, the NPMLE has little bias in estimating the cumulative hazard function, especially when n = 500.

Table 1.

Simulation results on the estimation of β1 with complete data.

| n | r | NPMLE

|

Naive

|

RE | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bias | SE | SEE | CP | Bias | SE | SEE | CP | ||||

| 200 | 0 | β11 | 0.004 | 0.298 | 0.303 | 0.961 | 0.003 | 0.312 | 0.318 | 0.956 | 1.098 |

| β12 | −0.003 | 0.663 | 0.666 | 0.955 | 0.001 | 0.691 | 0.693 | 0.953 | 1.087 | ||

| 0.5 | β11 | −0.010 | 0.302 | 0.307 | 0.955 | −0.010 | 0.315 | 0.320 | 0.954 | 1.087 | |

| β12 | 0.012 | 0.670 | 0.675 | 0.958 | 0.010 | 0.699 | 0.700 | 0.954 | 1.089 | ||

| 1 | β11 | −0.006 | 0.302 | 0.304 | 0.954 | −0.009 | 0.314 | 0.320 | 0.958 | 1.083 | |

| β12 | 0.011 | 0.679 | 0.685 | 0.960 | 0.012 | 0.708 | 0.710 | 0.953 | 1.085 | ||

| 500 | 0 | β11 | 0.002 | 0.187 | 0.188 | 0.950 | 0.011 | 0.201 | 0.205 | 0.959 | 1.152 |

| β12 | 0.002 | 0.416 | 0.417 | 0.951 | 0.006 | 0.440 | 0.440 | 0.954 | 1.118 | ||

| 0.5 | β11 | −0.003 | 0.192 | 0.190 | 0.947 | −0.010 | 0.197 | 0.197 | 0.955 | 1.050 | |

| β12 | −0.003 | 0.426 | 0.430 | 0.953 | 0.005 | 0.438 | 0.439 | 0.951 | 1.055 | ||

| 1 | β11 | −0.002 | 0.194 | 0.196 | 0.952 | 0.000 | 0.199 | 0.200 | 0.963 | 1.052 | |

| β12 | 0.000 | 0.429 | 0.431 | 0.953 | −0.002 | 0.449 | 0.452 | 0.955 | 1.099 | ||

Note: Bias and SE are the bias and standard error of the parameter estimator; SEE is the mean of the standard error estimator; CP is the coverage probability of the 95% confidence interval; RE is the variance of the naive estimator over that of the NPMLE. Each entry is based on 10,000 replicates.

Figure 1.

Estimation of the cumulative hazard function Λ1(·) by the NPMLE. The true values and the mean estimates (based on 10,000 replicates) are shown by the solid and dashed curves, respectively.

Next, we simulated missing values on the causes of failure by assuming that the probability of ξ = 0 is 0.3 given that the subject is not right censored. The results for the estimation of β1 by the NPMLE and the complete-case naive estimator are summarized in Table 2. The NPMLE continues to perform well. The naive estimator is substantially less efficient and is severely biased for β12 as a result of the dependence of the right censoring time on Z2.

Table 2.

Simulation results on the estimation of β1 with missing data.

| n | r | NPMLE

|

Naive

|

RE | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bias | SE | SEE | CP | Bias | SE | SEE | CP | ||||

| 200 | 0 | β11 | 0.010 | 0.319 | 0.322 | 0.956 | −0.002 | 0.345 | 0.350 | 0.959 | 1.169 |

| β12 | 0.002 | 0.703 | 0.705 | 0.955 | 0.122 | 0.767 | 0.771 | 0.930 | 1.190 | ||

| 0.5 | β11 | 0.015 | 0.329 | 0.332 | 0.954 | 0.005 | 0.360 | 0.366 | 0.957 | 1.198 | |

| β12 | −0.001 | 0.710 | 0.717 | 0.964 | 0.130 | 0.777 | 0.783 | 0.924 | 1.199 | ||

| 1 | β11 | −0.002 | 0.329 | 0.332 | 0.953 | −0.013 | 0.357 | 0.364 | 0.957 | 1.178 | |

| β12 | 0.007 | 0.721 | 0.724 | 0.955 | 0.122 | 0.781 | 0.787 | 0.921 | 1.174 | ||

| 500 | 0 | β11 | −0.003 | 0.198 | 0.202 | 0.955 | 0.002 | 0.216 | 0.217 | 0.953 | 1.187 |

| β12 | −0.005 | 0.444 | 0.443 | 0.950 | 0.131 | 0.489 | 0.490 | 0.821 | 1.213 | ||

| 0.5 | β11 | 0.000 | 0.205 | 0.203 | 0.947 | −0.004 | 0.224 | 0.226 | 0.952 | 1.198 | |

| β12 | 0.000 | 0.446 | 0.450 | 0.952 | 0.138 | 0.488 | 0.488 | 0.813 | 1.195 | ||

| 1 | β11 | 0.005 | 0.206 | 0.206 | 0.950 | −0.005 | 0.228 | 0.229 | 0.952 | 1.231 | |

| β12 | 0.000 | 0.453 | 0.451 | 0.946 | 0.119 | 0.498 | 0.499 | 0.834 | 1.206 | ||

Note: See the Note to Table 1.

4. An HIV Study

The Bangkok Metropolitan Administration (BMA) conducted a prospective study on a cohort of 1,209 initially HIV-seronegative injecting drug users (Hudgens et al., 2001). The study was designed to investigate risk factors for HIV incidence and develop better prevention strategies. The subjects were followed from 1995 to 1998 at 15 BMA drug treatment clinics. Blood tests were conducted on each participant approximately every 4 months post recruitment for evidence of HIV-1 seroconversion (i.e., detection of HIV-1 antibodies in the serum). By December 1998, there were 133 HIV-1 seroconversions and approximately 2,300 person-years of follow-up. Out of the 133 seroconversions, 27 were of viral subtype B, and 99 of subtype E. The subtypes for the remaining 7 were unknown but assumed to be either B or E.

We apply the proposed methods to the data derived from this study by treating the two HIV-1 subtypes as competing risks with partially missing information. We investigate the influence of potential risk factors on the cumulative incidence of HIV-1 seroconversion with time since recruitment as the principal time scale. The potential risk factors include age at baseline (in years), gender (female vs male), whether the subject had a history of needle sharing (yes vs no), whether s/he had an imprisonment history before recruitment, and whether s/he had been imprisoned before recruitment and injected drug during imprisonment (yes vs no). We consider logarithmic transformation functions and . The log-likelihood is maximized at r1 = 1.6 and r2 = 0.2, which is the combination of transformation functions that would be selected by the AIC criterion. Table 3 shows the results for this combination, as well as the results for r1 = r2 = 0 (proportional hazards) and r1 = r2 = 1 (proportional odds).

Table 3.

Analysis of the BMA HIV-1 study.

| NPMLE

|

Naive

|

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Substype B

|

Subtype E

|

Substype B

|

Subtype E

|

|||||||||

| Est | SE | p-value | Est | SE | p-value | Est | SE | p-value | Est | SE | p-value | |

| Proportional hazards | ||||||||||||

| Age | −0.027 | 0.182 | 0.883 | −0.268 | 0.099 | 0.007 | 0.009 | 0.199 | 0.963 | −0.285 | 0.097 | 0.003 |

| Gender | −0.116 | 0.444 | 0.793 | 0.618 | 0.277 | 0.026 | 0.020 | 0.551 | 0.970 | 0.628 | 0.377 | 0.096 |

| Needle | 1.038 | 0.240 | <0.001 | −0.031 | 0.196 | 0.875 | 1.033 | 0.301 | 0.001 | −0.010 | 0.265 | 0.969 |

| Drug | 0.098 | 0.139 | 0.479 | 0.374 | 0.194 | 0.054 | 0.018 | 0.186 | 0.924 | 0.334 | 0.198 | 0.091 |

| Prison | −0.557 | 0.424 | 0.189 | 0.727 | 0.216 | 0.001 | −0.599 | 0.500 | 0.231 | 0.737 | 0.227 | 0.001 |

| Proportional odds | ||||||||||||

| Age | 0.085 | 0.184 | 0.646 | −0.305 | 0.104 | 0.003 | −0.010 | 0.194 | 0.959 | −0.272 | 0.132 | 0.039 |

| Gender | −0.143 | 0.454 | 0.752 | 0.677 | 0.355 | 0.057 | 0.022 | 0.531 | 0.967 | 0.729 | 0.431 | 0.091 |

| Needle | 0.975 | 0.238 | <0.001 | −0.064 | 0.222 | 0.775 | 1.071 | 0.282 | <0.001 | −0.055 | 0.277 | 0.841 |

| Drug | 0.118 | 0.113 | 0.300 | 0.425 | 0.194 | 0.028 | −0.019 | 0.203 | 0.926 | 0.334 | 0.199 | 0.093 |

| Prison | −0.588 | 0.450 | 0.191 | 0.757 | 0.193 | <0.001 | −0.513 | 0.543 | 0.344 | 0.717 | 0.244 | 0.003 |

| Selected model | ||||||||||||

| Age | 0.085 | 0.182 | 0.639 | −0.264 | 0.090 | 0.003 | −0.053 | 0.203 | 0.794 | −0.256 | 0.119 | 0.032 |

| Gender | −0.107 | 0.507 | 0.832 | 0.521 | 0.350 | 0.136 | 0.018 | 0.585 | 0.976 | 0.591 | 0.430 | 0.169 |

| Needle | 0.998 | 0.235 | <0.001 | −0.075 | 0.244 | 0.760 | 0.996 | 0.274 | <0.001 | −0.025 | 0.281 | 0.930 |

| Drug | 0.123 | 0.133 | 0.356 | 0.362 | 0.195 | 0.064 | 0.030 | 0.190 | 0.876 | 0.325 | 0.240 | 0.176 |

| Prison | −0.552 | 0.421 | 0.190 | 0.769 | 0.188 | <0.001 | −0.508 | 0.520 | 0.329 | 0.716 | 0.241 | 0.003 |

Note: Est and SE denote the parameter estimate and (estimated) standard error.

There are considerable differences in the parameter estimates between the NPMLE and naive methods; the latter tends to produce larger standard errors than the former. The effects of risk factors on the two competing risks are quite different. By the NPMLE, needle sharing significantly increases the incidence of seroconversion with HIV-1 subtype B, but its effect on subtype E is minimal. Younger age and imprisonment history significantly increase the incidence of seroconversion with subtype E; drug injection has a marginally significant effect on the incidence of subtype E. None of these risk factors, however, are significantly associated with the incidence of subtype B. To illustrate the joint inference by the NPMLE, we conduct a joint test for the effects of imprisonment history on the two viral subtypes. The test statistic is 12.8, which is highly significant.

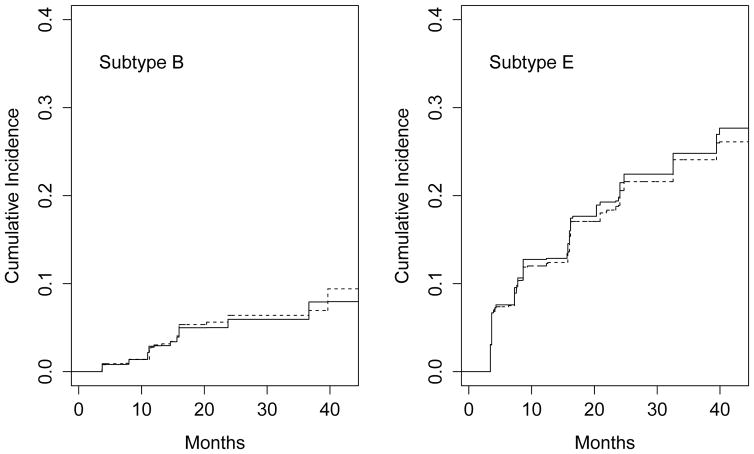

To illustrate prediction, we display in Figure 2 the NPMLE and naive estimates of the cumulative incidence function for a 32-year-old female with a history of needle sharing, drug injection, and imprisonment before recruitment. The cumulative incidence of seroconversion with HIV-1 subtype E is much higher than that of subtype B. The naive method yields noticeably different estimates than the NPMLE, especially for subtype E. The discrepancies are likely due to omission of failures with unknown causes, which are mostly assigned to subtype E by the NPMLE.

Figure 2.

Estimated cumulative incidence of seroconversion in the BMA HIV-1 study for a 32-year-old woman with needle sharing, drug injection, and imprisonment before recruitment. The solid and dashed curves pertain to the NPMLE and naive methods, respectively.

Table 4 shows the results from the approach of mid-point imputation, i.e., using the the mid-point of the interval to impute the failure time. The parameter estimates differ considerably from their NPMLE counterparts in Table 3, and the standard error estimates tend to be reduced. Thus, the significance levels for some of the risk factors are changed, indicating the importance of using statistically valid methods for analysis of interval-censored data.

Table 4.

Analysis of the BMA HIV-1 study using mid-point imputation.

| Substype B

|

Subtype E

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Est | SE | p-value | Est | SE | p-value | |

| Proportional hazards | ||||||

| Age | 0.020 | 0.155 | 0.899 | −0.213 | 0.083 | 0.010 |

| Gender | −0.216 | 0.453 | 0.633 | 0.414 | 0.320 | 0.196 |

| Needle | 1.140 | 0.214 | < 0.001 | −0.002 | 0.216 | 0.994 |

| Drug | −0.010 | 0.122 | 0.933 | 0.474 | 0.169 | 0.005 |

| Prison | −0.524 | 0.354 | 0.138 | 0.613 | 0.171 | < 0.001 |

| Proportional odds | ||||||

| Age | 0.052 | 0.165 | 0.752 | −0.202 | 0.076 | 0.008 |

| Gender | −0.304 | 0.429 | 0.479 | 0.341 | 0.314 | 0.278 |

| Needle | 1.008 | 0.202 | < 0.001 | 0.014 | 0.213 | 0.949 |

| Drug | −0.056 | 0.120 | 0.643 | 0.490 | 0.173 | 0.005 |

| Prison | −0.492 | 0.353 | 0.163 | 0.787 | 0.165 | < 0.001 |

| Selected model | ||||||

| Age | 0.046 | 0.160 | 0.776 | −0.166 | 0.079 | 0.036 |

| Gender | −0.233 | 0.447 | 0.602 | 0.413 | 0.308 | 0.180 |

| Needle | 1.140 | 0.207 | < 0.001 | 0.053 | 0.215 | 0.803 |

| Drug | −0.015 | 0.117 | 0.898 | 0.450 | 0.172 | 0.009 |

| Prison | −0.474 | 0.371 | 0.201 | 0.696 | 0.166 | < 0.001 |

Note: See the Note to Table 3.

5. Discussion

There is some literature on the NPMLE for interval-censored univariate failure time data; see Huang (1996), Huang and Wellner (1997), and Zeng et al. (2016). It is more difficult to establish the asymptotic properties of the NPMLE for interval-censored competing risks data with partially missing causes of failure. First, the multiplicity of failure types requires that the least favorable directions hold simultaneously for all nuisance tangent spaces. Second, as the probability of missing the cause of failure information may depend on the examination times and the covariates, the proof for the existence of a solution to the normal equations for the least favorable directions requires careful arguments for the smoothness of the score and information operators.

The computation of the NPMLE with interval-censored competing risks data also poses new challenges. The iterative convex minorant (ICM) algorithm (Huang and Wellner, 1997; Groeneboom and Jongbloed, 2014) is not applicable to time-varying covariates or incomplete cause-of-failure data because in such cases the nuisance parameters are entangled in the likelihood so that the diagonal approximation to the Hessian matrix becomes inaccurate. In addition, the ICM algorithm tends to be unstable for large datasets because it attempts to update a large number of parameters simultaneously using a quasi-Newton method (Wang et al., 2015). By sacrificing some computational speed, our EM algorithm updates each parameter using a self-consistency equation and is thus more reliable. We have not encountered any non-convergence in our extensive numerical studies. In the simulation studies, it took about 10 and 40 seconds to analyze a dataset with n = 200 and 500, respectively. We have included an R program in the Supplementary Materials.

In practice, it may be difficult to determine the causes of failure for all study subjects, especially when the ascertainment requires an extra (and possibly costly) step. In the BMA study, for instance, the HIV-1 subtype information required genotyping the viral DNA (Hudgens et al., 2001). The NPMLE approach enables one to make valid and efficient inference in the presence of missing information on the causes of failure.

We have studied both the NPMLE and naive estimators. The naive estimator may be preferable if the interest lies only in a subset of risks. However, the naive estimator is less satisfactory than the NPMLE for several reasons. First, the naive estimator is not statistically efficient. Second, it cannot properly handle unknown causes of failure. Finally, it does not provide simultaneous inference, which is often desirable because an increase in the incidence of one risk naturally reduces the incidence of other risks.

In independent work, Li (2016) proposed a spline-based method for the Fine and Gray (1999) model with interval-censored data. It is difficult to choose the number of knots and their locations. With right-censored data, one can use the quantiles of the observed failure times as the knots. This strategy is not applicable to interval-censored data due to the lack of exact observations. Specifically, because the examination times are not the actual event times, the cumulative baseline hazard functions may not jump at those locations. If there is no jump between two specified knots, the computation will be unstable. The NPMLE approach is advantageous in that it allows the jump points of the cumulative hazard functions to be determined in a data-adaptive manner and thus offers a fully automated solution.

In some applications, a subset of risks is interval censored while the rest is right censored. For example, in the Breastfeeding, Antiretrovirals, and Nutrition study, there were three competing risks: infant HIV infection, weening, and infant death prior to infection or weening (Hudgens et al. 2014). While the first two risks were interval censored, the time to death was known exactly or right censored. We plan to extend our work to this type of competing risks data.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health awards R01GM047845, R01AI029168, R01CA082659, and P01CA142538. The authors thank the Editor, an Associate Editor, and a referee for their helpful comments.

Footnotes

Web Appendix, referenced in Section 2.4, and the R code implementing the methodology are available with this paper at the Biometrics website on Wiley Online Library.

References

- Bickel PJ, Klaassen CAJ, Ritov Y, Wellner JA. Efficient and Adaptive Estimation for Semiparametric Models. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Chen K, Jin Z, Ying Z. Semiparametric analysis of transformation models with censored data. Biometrika. 2002;89:659–668. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng SC, Wei LJ, Ying Z. Analysis of transformation models with censored data. Biometrika. 1995;82:835–845. [Google Scholar]

- Fine JP, Gray RJ. A proportional hazards model for the subdistribution of a competing risk. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1999;94:496–509. [Google Scholar]

- Gray RJ. A class of K-sample tests for comparing the cumulative incidence of a competing risk. The Annals of Statistics. 1988;16:1141–1154. [Google Scholar]

- Groeneboom P, Jongbloed G. Nonparametric Estimation Under Shape Constraints: Estimators, Algorithms and Asymptotics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Groeneboom P, Maathuis MH, Wellner JA. Current status data with competing risks: consistency and rates of convergence of the MLE. The Annals of Statistics. 2008a;36:1031–1063. doi: 10.1214/009053607000000983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groeneboom P, Maathuis MH, Wellner JA. Current status data with competing risks: limiting distribution of the MLE. The Annals of Statistics. 2008b;36:1064–1089. doi: 10.1214/009053607000000983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang J. Efficient estimation for the proportional hazards model with interval censoring. The Annals of Statistics. 1996;24:540–568. [Google Scholar]

- Huang J, Wellner JA. Interval censored survival data: a review of recent progress. In: Lin DY, Fleming TR, editors. Proceedings of the First Seattle Symposium in Biostatistics: Survival Analysis. New York: Springer-Verlag; 1997. pp. 123–169. [Google Scholar]

- Hudgens MG, Satten GA, Longini IM. Nonparametric maximum likelihood estimation for competing risks survival data subject to interval censoring and truncation. Biometrics. 2001;57:74–80. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341x.2001.00074.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudgens MG, Li C, Fine JP. Parametric likelihood inference for interval censored competing risks data. Biometrics. 2014;70:1–9. doi: 10.1111/biom.12109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jewell NP, van der Laan M, Henneman T. Nonparametric estimation from current status data with competing risks. Biometrika. 2003;90:183–197. [Google Scholar]

- Kalbfleisch JD, Prentice RL. The Statistical Analysis of Failure Time Data. 2. Hoboken: John Wiley; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Li C. The Fine-Gray model under interval censored competing risks data. Journal of Multivariate Analysis. 2016;143:327–344. doi: 10.1016/j.jmva.2015.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C, Fine JP. Smoothed nonparametric estimation for current status competing risks data. Biometrika. 2013;100:173–187. [Google Scholar]

- Lu W, Ying Z. On semiparametric transformation cure models. Biometrika. 2004;91:331–343. [Google Scholar]

- Mao L, Lin DY. Efficient estimation of semiparametric transformation models for the cumulative incidence of competing risks. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, Series B. 2016 doi: 10.1111/rssb.12177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinussen T, Scheike TH. Dynamic Regression Models for Survival Data. New York: Springer-Verlag; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy SA, Van der Vaart AW. On profile likelihood. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 2000;95:449–465. [Google Scholar]

- Turnbull BW. The empirical distribution function with arbitrarily grouped, censored and truncated data. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, Series B. 1976:290–295. [Google Scholar]

- van der Vaart AW, Wellner JA. Weak Convergence and Empirical Processes. New York: Springer-Verlag; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, McMahan CS, Hudgens MG, Qureshi ZP. A flexible, computationally efficient method for fitting the proportional hazards model to interval censored data. Biometrics. 2015;72:22231. doi: 10.1111/biom.12389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng D, Mao L, Lin DY. Maximum likelihood estimation for semiparametric transformation models with interval-censored data. Biometrika. 2016;103:253–271. doi: 10.1093/biomet/asw013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.