Abstract

Patient-reported experience is a critical part of measuring health care quality. There are limited data on racial differences in patient experience. Using patient-level data for 2009–10 from the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS), we compared blacks’ and whites’ responses on measures of overall hospital rating, communication, clinical processes, and hospital environment. In unadjusted results, there were no substantive differences between blacks’ and whites’ ratings of hospitals. Blacks were less likely to recommend hospitals but reported more positive experiences, compared to whites. Higher educational attainment and self-reported worse health status were associated with more negative evaluations in both races. Additionally, blacks rated minority-serving hospitals worse than other hospitals on all HCAHPS measures. Taken together, there were surprisingly few meaningful differences in patient experience between blacks and whites across US hospitals. Although blacks tend to receive care at worse-performing hospitals, compared to whites, within any given hospital black patients tend to report better experience than whites do.

Patient-reported experience in health care is widely recognized as an important quality metric.1 Payers and policy makers are increasingly using this metric to hold hospitals accountable, and performance on patient-reported experience measures has received widespread attention.2 One area of particular concern is racial disparities in patients’ experiences. Previous studies have shown that patients who report poor experiences with health systems are more likely to delay further care and are at higher risk of nonadherence to treatment recommendations, compared to patients who report better experiences.3–6 These patterns of delay and non-adherence are more commonly seen among minority patients than among white patients.7–10 Therefore, understanding how patient experience varies between minority and white patients is particularly salient.

In this study we focused on the experience of care for black patients compared to that of white patients (for information related to Hispanics, see online Appendix Exhibit A1).11 There are reasons to be concerned that black patients may have worse experiences with health care than whites. Because of various historical events, black patients have lower levels of trust in the health care system and physicians, which may contribute to their experience.12,13 It is possible that because of such factors as lack of cultural competency, some health care providers may be less effective at communicating with black patients or addressing their needs than they are with white patients. Previous work has shown that distrust of the health care system is associated with lower rates of recommended disease prevention and treatment of acute and chronic illness, as well as worse health status.13 It is critically important to understand both the extent to which black patients may have differences in experience with hospital care and how those differences might be addressed.

Care for black patients is highly concentrated: About 10 percent of US hospitals care for nearly half of all black patients.14 A previous study found that the top 10 percent of hospitals by proportion of black patients admitted during 2009–10— which we call minority-serving hospitals—are more likely than other hospitals to report providing cultural competency training.15 Furthermore, hospitals with higher cultural competency scores have better Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS) scores both overall and specifically for minority patients, compared to other hospitals.16 In turn, hospitals with higher HCAHPS scores do better on measures of clinical performance, compared to other hospitals.17

In addition, hospitals in communities with higher proportions of minority residents employ a higher fraction of clinical providers who are minorities themselves, compared to other hospitals.18,19 Research has shown that when minority patients are cared for by minority providers, the patients are more likely to rate their care highly than when minority patients are cared by nonminority providers.18,20 Taken together, these previous findings led us to hypothesize that racial disparities in patient experience would be smaller in hospitals that serve a disproportionately high number of black patients than in other hospitals.

Although there is robust evidence of racial differences in care patterns and outcomes, less is known about racial differences in patient experience.21,22 Mark Haviland and colleagues found that blacks gave a mix of higher and lower ratings on measures of satisfaction regarding their individual health plans, compared to whites.22 Elizabeth Goldstein and coauthors found that for a group of hospitals that voluntarily chose to report data, there were very few differences in patient experience between blacks and whites.21 However, neither study directly examined care delivered at minority-serving hospitals. Our study examined patient experience across all US hospitals, avoiding potential bias from over-or underreporting by different types of hospitals, and it included hospitals with large concentrations of black patients.

In this study we sought to answer three questions. First, do blacks have worse patient experience in US hospitals compared to whites? Second, if gaps in patient experience do exist, to what extent do they vary according to patients’ level of education or self-reported health status? Previous work has shown that these factors affect patients’ outcomes and experiences.23,24 Finally, are differences in experiences between black and white patients predominantly seen within the same hospitals, or are they driven primarily by site of care? We hypothesized that black patients’ experiences of care would be better at hospitals that served large numbers of black patients than at hospitals that served mostly white patients— and, thus, that differences in patient experience between blacks and whites would be smaller at hospitals that served large numbers of black patients.

Study Data And Methods

DATA

We used patient-level data obtained from the 2009 and 2010 HCAHPS surveys of hospitals. Hospitals are required to report to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) data on measures including those of inpatient experience. The HCAHPS survey was developed by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality and is administered by hospitals to a random sample of adult patients from forty-eight hours to six weeks after discharge.

The survey reports the following two global measures of a patient’s overall experience: an overall rating of the hospital on a scale from 0 to 10, and whether or not the patient would recommend the hospital. The survey also reports six composite measures: communication with physicians, communication with nurses, communication about medications, pain control, discharge process, and staff responsiveness. The methodology used by CMS to calculate composite scores has been described previously.25

In addition, the survey reports two patient measures of aspects of the hospital environment: cleanliness and quietness. The survey also contains self-reported information on the patient’s age, sex, race, health status, primary language spoken at home, reason for admission, and level of education. In this study we included only patients who identified themselves as black or white. We excluded Hispanic patients (including those who reported themselves as Hispanic black or Hispanic white) and patients from other minority groups (for information related to other minority groups, see Appendix Exhibit A1).11

Because of CMS regulations, patient-level data are available to researchers only in ways that make it statistically impossible to identify individual hospitals. Therefore, we could obtain data on only the following three variables to characterize the hospitals where patients received their care: each hospital’s proportion of inpatient admissions who were black Medicare patients, hospital size (small, or fewer than 100 beds; medium, or 100–399 beds; or large, or 400 beds or more—the size ranges used by the American Hospital Association), and whether or not the hospital was a major teaching hospital (defined as being a member of the Council of Teaching Hospitals of the Association of American Medical Colleges).

We classified the 10 percent of hospitals with the highest proportion of black patients admitted as minority-serving hospitals and the other 90 percent of hospitals as non-minority-serving hospitals. Our data were obtained from the Iowa Quality Improvement Organization, and linkage of the American Hospital Association survey data to HCAHPS data was conducted by MassPRO.

OUTCOMES

Our primary outcomes were the following two global measures of a patient’s experience: the overall rating of the hospital on a scale from 0 to 10, and whether the patient would recommend the hospital. Our secondary outcomes were the eight other measures described above (the six composite measures and the two patient measures of the hospital environment). Each primary and secondary outcome was dichotomized as follows: a rating of 9 or 10 versus a rating of 8 or below for hospital rating; a rating of “definitely yes” versus “definitely no,” “probably no,” and “probably yes” for recommendation; “yes” versus “no” for the discharge domain; and “always” versus “never,” “sometimes,” and “usually” for the remaining measures. For example, with regard to communication with doctors, patients were asked, “How often did the doctors treat you with courtesy and respect?” A composite score was then created, as described by CMS.25

ANALYSIS

We used chi-square tests to compare the characteristics of black and white patients and those of the two types of hospitals. We also used chi-square tests to compare racial differences in patient experience for the primary and secondary outcomes.

Next, we built multivariable logistic regression models, using generalized estimating equations to account for clustering at the hospital level. To capture overall differences between black and white patients, we used an independent correlation structure. To account for within-hospital correlation, we used an empirical correlation matrix. These models adjusted for baseline differences in self-reported age, sex, health status, education, primary language spoken at home, and reason for admission.

To identify within-hospital racial differences, we then built a multilevel logistic regression model using hospital random effects. Finally, we reran models that used generalized estimating equations and that were stratified by education, health status, and type of hospital (minority-serving or other). The analyses within subgroups were preceded by tests for effect modification using interaction terms between race and each of the three stratification factors.

Analyses were performed using SAS, version 9.4. The study was approved by the Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health Institutional Review Board’s Committee on the Use of Human Subjects.

LIMITATIONS

Our study had several limitations. First, we used HCAHPS measures, which on average had only a 30 percent response rate. However, extensive testing of the measures suggests that the results are not substantially affected by nonresponse bias, especially when factors such as response mode are taken into account. In fact, CMS has enough confidence in these measures to include scores on them in its Hospital Value-Based Purchasing (VBP) Program.

Second, HCAHPS measures are inherently subjective. We were therefore unable to distinguish between differences in behavior of physicians and nurses within hospitals and differences in patients’ expectations.26 However, one could argue that providers’ behavior and patients’ expectations are not easily separable, given that the former can shape the latter. In any case, it is critically important to examine patient experience despite unmeasurable factors such as underlying expectations.

Finally, our data reflected care before the start of Hospital VBP Program and therefore did not reflect changes that might have resulted from the program. It is possible that trends in patient experience may have changed since the program’s introduction. However, we think any substantial differences are unlikely, since national HCAHPS scores have risen only slightly over the past few years, and there is little evidence that they would have risen more for one racial group than for another.27

Study Results

PATIENT CHARACTERISTICS

We had data on 4,365,175 respondents who completed the HCAHPS survey during 2009–10 (Exhibit 1). Black respondents made up 9.8 percent of the sample, and white respondents the remaining 90.2 percent. Compared to white patients, black patients were more likely to be younger than age sixty-five, to be female, to report their health status as fair or poor, and to have been admitted for a medical reason, and were less likely to have graduated from high school.

Exhibit 1.

Characteristics of black and white adult patients admitted to US hospitals in 2009–10

| Characteristic | Black | White |

|---|---|---|

| Number | 426,385 | 3,938,790 |

|

Age (years) | ||

| Less than 65 | 66.8% | 47.1% |

| 65–69 | 9.3 | 11.2 |

| 70–79 | 14.9 | 22.4 |

| 80 or more | 8.9 | 19.0 |

|

Sex | ||

| Male | 32.5 | 38.6 |

| Female | 67.5 | 60.8 |

|

Education | ||

| Less than high school | 24.3 | 13.7 |

| High school graduate or GED | 32.1 | 33.1 |

| Some college or beyond | 43.5 | 53.1 |

|

Overall health | ||

| Excellent | 13.1 | 12.5 |

| Very good or good | 55.0 | 58.4 |

| Fair or poor | 31.9 | 29.1 |

|

Reason for admission | ||

| Maternity care | 11.2 | 10.6 |

| Medical | 60.3 | 52.5 |

| Surgical | 28.4 | 36.9 |

SOURCE Authors’ analysis of data for 2009–10 from the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems.

NOTES Some percentages do not sum to 100 because of rounding. All differences between blacks and whites were significant (p < 0.001).

HOSPITAL CHARACTERISTICS

Of the 3,796 hospitals included in our study, 364 hospitals (9.6 percent) were designated as minority-serving hospitals based on their proportion of black patients (Appendix Exhibit A2).11 These hospitals were more likely than the remaining hospitals to be large (36.1 percent versus 23.4 percent; p < 0.001) and to be teaching hospitals (34.8 percent versus 13.3 percent; p < 0.001). Unsurprisingly, the proportion of black patients in minority-serving hospitals was much higher than in other hospitals (41.2 percent versus 6.4 percent; p < 0.001).

PATIENT SATISFACTION BY RACE

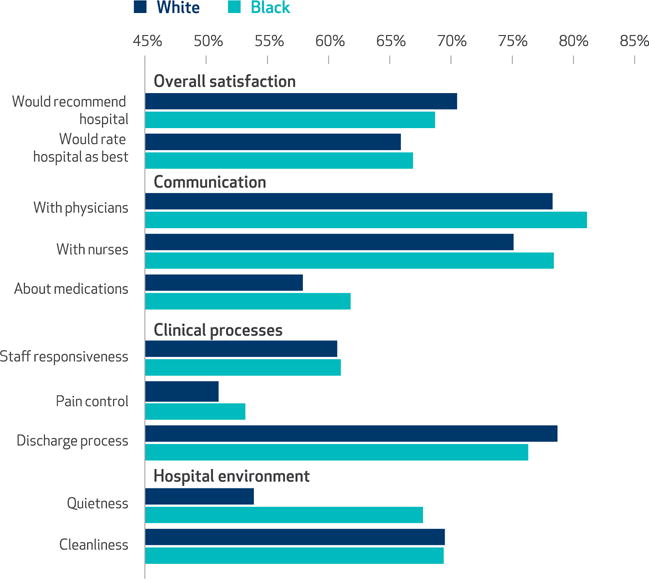

We examined the unadjusted and adjusted relationship between patient experience, which included two global measures of satisfaction and eight secondary domains of clinical care, and race (for adjusted results, see Exhibit 2; for unadjusted results, see Appendix Exhibit A3).11 In unadjusted results, there was no significant difference between blacks and whites in rating hospitals best (66.5 percent versus 65.9 percent; p = 0.37), but blacks were less likely than whites to recommend hospitals (68.1 percent versus 70.6 percent; p < 0.001) (see Appendix Exhibit A4).11 On the other measures, blacks reported more positive experiences than whites for seven of eight measures (Exhibit 3).

Exhibit 2. Differences between black and white hospital patients in patient experience, adjusted by patients’ characteristics, 2009–10.

SOURCE Authors’ analysis of data for 2009–10 from the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Health-care Providers and Systems. NOTES Multivariable regression models were used to adjust for differences between black and white satisfaction scores in self-reported age, sex, health status, education, primary language spoken at home, and reason for admission. Differences for all measures were significant (p < 0.01) except for cleanliness (p = 0.798).

Exhibit 3.

Adjusted differences in black and white patients’ hospital experiences, overall and within and between hospitals, 2009–10

| HCAHPS measure | Overall difference | Within-hospital component of difference | Between-hospital component of differencea |

|---|---|---|---|

|

OVERALL SATISFACTION | |||

| Would recommend hospital | −1.9%**** | 0.7%**** | −2.7% |

| Would rate hospital as best | 1.0**** | 3.8**** | −2.8 |

|

COMMUNICATION | |||

| With physicians | 2.8**** | 3.8**** | −1.0 |

| With nurses | 3.3**** | 5.4**** | −2.1 |

| About medications | 3.9**** | 5.4**** | −1.5 |

|

CLINICAL PROCESSES | |||

| Staff responsiveness | 0.3 | 0.9**** | −2.5 |

| Pain control | 2.2**** | 4.3**** | −2.1 |

| Discharge process | −2.3**** | −0.5**** | −1.9 |

|

HOSPITAL ENVIRONMENT | |||

| Quietness | 13.8**** | 13.9**** | −0.1 |

| Cleanliness | 0.1 | 2.8**** | −2.9 |

SOURCE Authors’ analysis of data for 2009–10 from the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS).

NOTE Multivariable regression models were used to adjust differences between black and white patients’ satisfaction scores for age, sex, health status, education, primary language spoken at home, and source of admission.

Determined by subtracting the within-hospital component of difference from the adjusted overall difference. The percentages in this column indicate the average difference in the performance scores on satisfaction between hospitals where blacks, on average, receive care and hospitals where whites, on average, receive care.

p < 0.001

In models adjusted by patient characteristics, results were similar except that blacks were slightly more likely than whites to rate hospitals best (66.9 percent versus 65.9 percent; p < 0.001) (see Appendix Exhibit A4).11

EFFECT OF EDUCATION

We stratified our results by education and health status. In both unadjusted (data not shown) and adjusted models (Exhibit 4), patients of both races with at least some college were less likely to recommend hospitals or give them the highest rating, compared to patients with less education. For both blacks and whites, higher educational attainment was also associated with more negative evaluations of communication measures, staff responsiveness, and both hospital environment measures (Exhibit 4). These stratified results were significant for all measures of patient experience. Moreover, adjusted differences in experience between blacks and whites were narrower among patients with at least some college for all measures except that related to the discharge process, compared to patients with less education.

Exhibit 4.

Adjusted differences in black and white patients’ hospital experiences, by level of education, 2009–10

| HCAHPS measure | High school or less

|

Some college or beyond

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Black | White | Difference | Black | White | Difference | |

|

OVERALL SATISFACTION | ||||||

| Would recommend hospital | 71.9% | 69.9% | 2.0%**** | 67.9% | 68.8% | −0.8%**** |

| Would rate hospital as best | 74.7 | 69.6 | 5.1**** | 64.7 | 63.0 | 1.7**** |

|

COMMUNICATION | ||||||

| With physicians | 85.2 | 80.5 | 4.7**** | 80.1 | 78.0 | 2.1**** |

| With nurses | 83.4 | 77.8 | 5.6**** | 78.3 | 74.1 | 4.2**** |

| About medications | 69.9 | 62.8 | 7.2**** | 60.0 | 56.8 | 3.2**** |

|

CLINICAL PROCESSES | ||||||

| Staff responsiveness | 70.3 | 65.4 | 4.9**** | 60.8 | 60.3 | 0.5 |

| Pain control | 58.2 | 53.8 | 4.4**** | 52.1 | 48.9 | 3.1**** |

| Discharge process | 77.6 | 78.2 | −0.6 | 76.9 | 77.5 | −0.6**** |

|

HOSPITAL ENVIRONMENT | ||||||

| Quietness | 77.6 | 63.4 | 14.2**** | 65.4 | 52.9 | 12.5**** |

| Cleanliness | 83.4 | 77.8 | 5.6**** | 78.3 | 74.1 | 4.2**** |

SOURCE Authors’ analysis of data for 2009–10 from the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS).

NOTES Multivariable regression models were used to adjust differences between black and white satisfaction scores for age, sex, health status, education, primary language spoken at home, and source of admission. Differences between values do not all match values precisely because of rounding. All interactions between education and race were significant (p < 0.001).

p < 0.001

EFFECT OF HEALTH STATUS

When we examined the effect of health status, patients who reported having either poor or fair health scored lower on all measures of patient experience, compared to patients who reported having good or excellent health, in both unadjusted (data not shown) and adjusted models (Appendix Exhibit A6).11 The patterns of differences between blacks and whites with different health statuses were consistent with the overall differences we found, with blacks reporting more positive experiences than whites across all ten measures.

PATIENT SATISFACTION BY SITE OF CARE

In our within-hospital analyses, which controlled for the influence of individual hospitals on the patient experience measures, blacks were slightly more likely than whites to recommend hospitals (69.7 percent versus 68.2 percent; p < 0.001) (see Appendix Exhibit A4).11 This was different from what we found in our unadjusted models and in our models that were adjusted by patient mix and survey mode only. In addition, the gap between blacks’ and whites’ experiences was wider in our within-hospital analyses than in the unadjusted models for the hospital rating and for seven of the eight secondary measures (Exhibit 3). Blacks were generally more positive in the within-hospital analyses than in the overall ones, except for satisfaction with the discharge process (see Appendix Exhibit A4).11

We subtracted the within-hospital differences from the overall differences to obtain the between-hospital components of difference. These estimated components reflect the differences in hospital scores attributable to the influence of hospitals on patient experience—which, in turn, reflects the differences in the average patient experience between minority-serving hospitals and other hospitals. The between-hospital components of difference between blacks and whites were −2.7 percent for recommendation of hospitals and −2.8 percent for ratings of hospitals (Exhibit 3). For all eight secondary domains, the components were also negative. The negative signs suggest that black patients get care at hospitals where, on average, the experience of care is worse for all patients.

We compared patient experience in minority-serving hospitals versus that in other hospitals, given that care of black patients is highly concentrated in a few hospitals. Overall, patients were less likely to recommend minority-serving hospitals than other hospitals (67.2 percent versus 71.7 percent; p < 0.001) and less likely to give minority-serving hospitals a high rating, compared to other hospitals (64.5 percent versus 67.2 percent; p < 0.001) (Appendix Exhibit A5).11

When we stratified our results by race, we found that, compared to whites, blacks were more likely to recommend other hospitals (73.1 percent versus 71.6 percent; p < 0.001) and less likely to recommend minority-serving hospitals (66.1 percent versus 68.0 percent; p < 0.005) (Appendix Exhibit A7).11 Similarly, black respondents were more likely than whites to rate other hospitals as best (71.1 percent versus 67.0 percent; p < 0.001). There was no significant difference in the rating of minority-serving hospitals between the two races (65.2 percent for blacks versus 64.2 percent for whites; p = 0.10). A formal test of interaction between race and site of care was significant for both overall hospital rating and recommendation of hospital (p < 0.001 for both).

Discussion

In our national sample of US hospitals, we found surprisingly few meaningful differences in patient experience between black and white patients. Blacks generally reported more positive experiences than whites did. Even in the area of communication, where concerns about cultural competence may be heightened, we found that black patients generally reported more positive experiences with both physicians and nurses than white patients did. However, the gap between races in patient experience was smaller among patients with at least some college than among those with less education.

We also found that while all patients gave minority-serving hospitals worse scores than other hospitals, black patients seemed to rate them no more highly than white patients did. In fact, black patients reported a better experience in other hospitals than in minority-serving hospitals across the board. Taken together, these findings offer some reassurance about the experiences of black patients compared to those of white patients in US hospitals. However, they also raise important concerns that black patients’ care is concentrated in hospitals that perform poorly on patient experience for all patients.

Our findings of racial differences by patients’ characteristics and sites of care have important implications for the health outcomes of minority patients. Our results indicate that minority patients, on average, receive care at hospitals that perform significantly worse than others on measures of patient satisfaction. Previous studies have shown that hospitals with the highest HCAHPS scores perform higher on quality measures of clinical processes, compared to hospitals with the lowest HCAHPS scores.17 Given that minority patients are already at higher risk of nonadherence to treatment recommendations and are more likely to experience delays in care, compared to white patients, the fact that minority patients are receiving care at minority-serving hospitals that perform worse on all measures of satisfaction raises particular concerns.

Our study confirms our hypothesis that site of care may be an important component of patient experience for blacks—but in a direction opposite to what we predicted. We tested the hypothesis that a high concentration of black patients in a given hospital would improve that hospital’s ability to provide a better experience for blacks, compared to hospitals with low concentrations of black patients. However, we found that minority-serving hospitals actually perform worse than other hospitals on patient experience of care for both blacks and whites.

Since the 2003 Institute of Medicine report Unequal Treatment highlighted racial disparities in care,28 increasing attention has been paid to the notion of cultural competency training to improve care delivered to minority patients. Previous work has shown that hospitals that deliver more culturally competent care have higher overall HCAHPS scores and also do particularly well with minority patients.16 Our findings suggest that enough effective cultural competency training may not be occurring in minority-serving hospitals, possibly because these institutions have fewer resources than other hospitals or focus on different priority areas. Policy efforts and interventions aimed at improving patient experience for minority patients may be more effective if they target minority-serving hospitals in particular, instead of trying to increase cultural competency training across all hospitals.

We observed a consistent pattern of blacks reporting more positive experiences than whites in terms of most measures of care. This finding may reflect racial differences in treatment, expectations, or both. For example, our results suggest that black and white patients may have different expectations for quietness in the hospital, given that whites were less satisfied than blacks with the level of quietness, and it is unlikely that black patients would be systematically allocated to quieter hospital rooms across the country, compared to whites. It is less clear what explains small differences in global rating measures (overall hospital ratings and likeliness to recommend the hospital).

Our findings of a narrower gap in patient experience between blacks and whites with higher educational attainment than between those with less education may also reflect differences in underlying expectations. Higher educational attainment correlates closely with higher socioeconomic status and greater financial security. Thus, compared to less educated patients, more educated patients may have higher expectations for health and a greater demand for a certain level of care, which translates to lower evaluations of hospital experience.29–31

We are unaware of any previous study that examined racial differences in patient experience across a nationally representative group of US hospitals. Goldstein and colleagues evaluated a subset of hospitals that voluntarily reported patient experience scores and found results somewhat similar to ours.21 Previous work has shown that physician groups that choose to voluntarily report data are different from those that choose not to, with higher performers more likely than lower performers to volunteer.32 Thus, examining all hospitals that are required to respond provides a more comprehensive and valid assessment of patient experience for blacks and whites in US hospitals.

Other studies focusing on commercial and Medicaid health plans have found that minorities tend to rate their plans lower than do whites.30 However, these gaps are largely due to within-plan instead of between-plan differences. Our findings are consistent with a broader set of studies suggesting that differences in care patterns between white and black patients are often driven more by where people receive care (that is, black patients’ disproportionately receiving care at hospitals with poor quality compared to hospitals with low concentrations of minority patients) than by being treated differently within the same institution, although this varies by condition and metric examined.14,33 For example, Tom LaVeist and colleagues found that health disparities are mitigated when patients receive care under similar conditions.34

Our work thus has important policy implications. First, minority-serving hospitals may be different from other hospitals—more lacking in resources or technical skills needed to provide patient-centered care. Therefore, efforts aimed at improving the experience of black patients needs to focus on minority-serving hospitals and to do so in ways that are likely to be effective in the institutions’ specific context. For example, identifying minority-serving hospitals that are particularly effective at delivering patient-centered care and then disseminating their practices may be a more effective approach to improving care at other similar hospitals than focusing on a broader set of high-performing institutions, most of which are likely to care for few minority patients. CMS has a series of programs focused on helping hospitals improve, though we are unaware of any program that specifically targets minority-serving institutions.

Finally, given that we know black patients have higher hospital readmission rates than whites,35 an area of concern is the small but consistent racial difference in receipt of adequate hospital discharge information. These findings may suggest one reason why gaps in readmission rates exist between blacks and whites. Both minority-serving and other hospitals appear to do a worse job ensuring effective discharge planning for black patients than for white patients. It may be that hospitals and policy makers need to make additional efforts in this area to ensure that all patients receive effective discharge planning and care coordination, particularly patients whose experience in this area has been suboptimal.

Conclusion

We found that across US hospitals, blacks reported comparable or even better patient experience than whites. These differences vary somewhat by educational status, with wider racial gaps among patients with lower levels of educational attainment than those with more education. Finally, while minority-serving hospitals tend to have lower levels of performance with all of their patients, we found no evidence that they were particularly adept at maximizing patient experience for blacks. These results suggest that policies and strategic efforts related to patient experience should focus on targeting the small number of hospitals that disproportionately care for black patients and on trying to improve their performance with all patients. ▪

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institute on Minority Health and Disparities (Grant No. 1R01MD006230-01A1) at the National Institutes of Health (NIH). The NIH had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; or preparation, review, and approval of the article.

Contributor Information

José F. Figueroa, Physician in the Department of Medicine at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, in Boston, Massachusetts

Jie Zheng, Senior statistician at the Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health, in Boston.

E. John Orav, Associate professor of biostatistics at the Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health.

Ashish K. Jha, Professor of health policy and management at the Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health

NOTES

- 1.Institute of Medicine. Crossing the quality chasm: a new health system for the 21st century. Washington (DC): National Academies Press; 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare program; hospital inpatient value-based purchasing program. Final rule. Fed Regist. 2011;76(88):26490–547. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Apter AJ, Reisine ST, Affleck G, Barrows E, ZuWallack RL. Adherence with twice-daily dosing of inhaled steroids. Socioeconomic and health-belief differences. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;157(6 Pt I):1810–7. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.157.6.9712007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Little P, Everitt H, Williamson I, Warner G, Moore M, Gould C, et al. Observational study of effect of patient centredness and positive approach on outcomes of general practice consultations. BMJ. 2001;323(7318):908–11. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7318.908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ruiz-Moral R, Pérula de Torres LA, Jaramillo-Martin I. The effect of patients’ met expectations on consultation outcomes. A study with family medicine residents. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(1):86–91. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0113-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. 2010 national healthcare disparities report [Internet] Rockville (MD): AHRQ; [last reviewed 2013; Jan cited 2016 Jun 15]. Available for download from: http://archive.ahrq.gov/research/findings/nhqrdr/nhdr10/ [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kulik A, Shrank WH, Levin R, Choudhry NK. Adherence to statin therapy in elderly patients after hospitalization for coronary revascularization. Am J Cardiol. 2011;107(10):1409–14. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2011.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roth MT, Esserman DA, Ivey JL, Weinberger M. Racial disparities in the quality of medication use in older adults: baseline findings from a longitudinal study. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(3):228–34. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1180-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dominick KL, Golightly YM, Bosworth HB. Racial differences in analgesic/anti-inflammatory medication adherence among patients with osteoarthritis. Ethn Dis. 2005;15(1):116–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaplan RC, Bhalodkar NC, Brown EJ, White J, Brown DL. Race, ethnicity, and sociocultural characteristics predict noncompliance with lipid-lowering medications. Prev Med. 2004;39(6):1249–55. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.04.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.To access the Appendix, click on the Appendix link in the box to the right of the article online.

- 12.Brandon DT, Isaac LA, LaVeist TA. The legacy of Tuskegee and trust in medical care: is Tuskegee responsible for race differences in mistrust of medical care? J Natl Med Assoc. 2005;97(7):951–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Armstrong K, Putt M, Halbert CH, Grande D, Schwartz JS, Liao K, et al. Prior experiences of racial discrimination and racial differences in health care system distrust. Med Care. 2013;51(2):144–50. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31827310a1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jha AK, Orav EJ, Li Z, Epstein AM. Concentration and quality of hospitals that care for elderly black patients. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(11):1177–82. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.11.1177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jha AK, Epstein AM. Governance around quality of care at hospitals that disproportionately care for black patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(3):297–303. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1880-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weech-Maldonado R, Elliott MN, Pradhan R, Schiller C, Hall A, Hays RD. Can hospital cultural competency reduce disparities in patient experiences with care? Med Care. 2012;50(Suppl):S48–55. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3182610ad1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jha AK, Orav EJ, Zheng J, Epstein AM. Patients’ perception of hospital care in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(18):1921–31. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0804116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cooper LA, Powe NR (Johns Hopkins University Baltimore, MD) Disparities in patient experiences, health care processes, and outcomes: the role of patient-provider racial, ethnic, and language concordance. New York (NY): Commonwealth Fund; 2004. Jul, [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marrast L, Zallman L, Woolhandler S, Bor D, McCormick D. Minority physicians’ role in the care of underserved patients: diversifying the physician workforce may be key in addressing health disparities. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(2):289–91. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.12756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cabral RR, Smith TB. Racial/ethnic matching of clients and therapists in mental health services: a meta-analytic review of preferences, perceptions, and outcomes. J Couns Psychol. 2011;58(4):537–54. doi: 10.1037/a0025266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goldstein E, Elliott MN, Lehrman WG, Hambarsoomian K, Giordano LA. Racial/ethnic differences in patients’ perceptions of inpatient care using the HCAHPS survey. Med Care Res Rev. 2010;67(1):74–92. doi: 10.1177/1077558709341066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Haviland MG, Morales LS, Dial TH, Pincus HA. Race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and satisfaction with health care. Am J Med Qual. 2005;20(4):195–203. doi: 10.1177/1062860605275754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Merlino JI, Kestranek C, Bokar D, Sun Z, Nissen SE, Longworth DL. HCAHPS survey results: impact of severity of illness on hospitals’ performance on HCAHPS survey results. J Patient Exp. 2014;1(2):16–21. doi: 10.1177/237437431400100204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Olshansky SJ, Antonucci T, Berkman L, Binstock RH, Boersch-Supan A, Cacioppo JT, et al. Differences in life expectancy due to race and educational differences are widening, and many may not catch up. Health Aff (Millwood) 2012;31(8):1803–13. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Calculation of HCAHPS scores: from raw data to publicly reported results [Internet] Baltimore (MD): CMS; 2011. Mar, [cited 2016 Jun 15]. Available from: http://www.hcahpsonline.org/Files/Calculation%20of%20HCAHPS%20Scores.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhu J, Weingart SN, Ritter GA, Tompkins CP, Garnick DW. Racial/ethnic disparities in patient experience with communication in hospitals: real differences or measurement errors? Med Care. 2015;53(5):446–54. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems. Summary analyses [Internet] Baltimore (MD): Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services; [cited 2016 Jun 21]. Available from: http://www.hcahpsonline.org/Files/December_2015_Summary_Analyses_Survey_Results.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Institute of Medicine. Unequal treatment: confronting racial and ethnic disparities in healthcare. Washington (DC): National Academies Press; 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Weech-Maldonado R, Morales LS, Spritzer K, Elliott M, Hays RD. Racial and ethnic differences in parents’ assessments of pediatric care in Medicaid managed care. Health Serv Res. 2001;36(3):575–94. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Weech-Maldonado R, Elliott MN, Morales LS, Spritzer K, Marshall GN, Hays RD. Health plan effects on patient assessments of medicaid managed care among racial/ethnic minorities. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19(2):136–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.30235.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Young GJ, Meterko M, Desai KR. Patient satisfaction with hospital care: effects of demographic and institutional characteristics. Med Care. 2000;38(3):325–34. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200003000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rosenthal MB, Frank RG, Li Z, Epstein AM. Early experience with pay-for-performance: from concept to practice. JAMA. 2005;294(14):1788–93. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.14.1788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hasnain-Wynia R, Baker DW, Nerenz D, Feinglass J, Beal AC, Landrum MB, et al. Disparities in health care are driven by where minority patients seek care: examination of the hospital quality alliance measures. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(12):1233–9. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.12.1233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.LaVeist T, Pollack K, Thorpe R, Fesahazion R, Gaskin D. Place, not race: disparities dissipate in southwest Baltimore when blacks and whites live under similar conditions. Health Aff (Millwood) 2011;30(10):1880–7. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Joynt KE, Orav EJ, Jha AK. Thirty-day readmission rates for Medicare beneficiaries by race and site of care. JAMA. 2011;305(7):675–81. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.