Abstract

Vesicular acetylcholine transporter (VAChT) is a reliable biomarker for assessing cholinergic dysfunction associated with dementia. We recently reported three new potent and selective carbon-11 labeled VAChT radiotracers. Herein, we report the resolution with a Chiralcel OD column of three additional fluorine containing VAChT ligands in which a fluoroethoxy or fluoroethylamino moiety was substituted for the methoxy group. An in vitro competitive binding assay showed (−)-7 had high potency for VAChT (Ki-VAChT = 0.31 ± 0.03 nM) and excellent selectivity for VAChT versus σ receptors (Ki-σ1= 1869 ± 248 nM, Ki-σ2 = 5482 ± 144 nM). Three different radiolabeling approaches were explored; the radiosynthesis. (−)-[18F]7 was successfully accomplished via a stepwise two-pot, three-step method with moderate yield (11 ± 2%) and high radiochemical purity (> 98%). PET imaging studies in a nonhuman primate indicated that (−)-[18F]7 rapidly entered the brain and accumulated in the VAChT-enriched striatum. Uptake of (−)-[18F]7 in the target striatal area peaked at 10 min and displayed improved clearance kinetics compared to our VAChT tracer [18F]VAT, which has been approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for first-in-man studies. These studies justify further investigation of (−)-[18F]7 and exploration of the structure-activity relationships of these fluoroethoxy and fluoroethylamino analogs.

Keywords: VAChT, radiosynthesis, fluorine-18, enantiomer, nonhuman primate, PET imaging

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

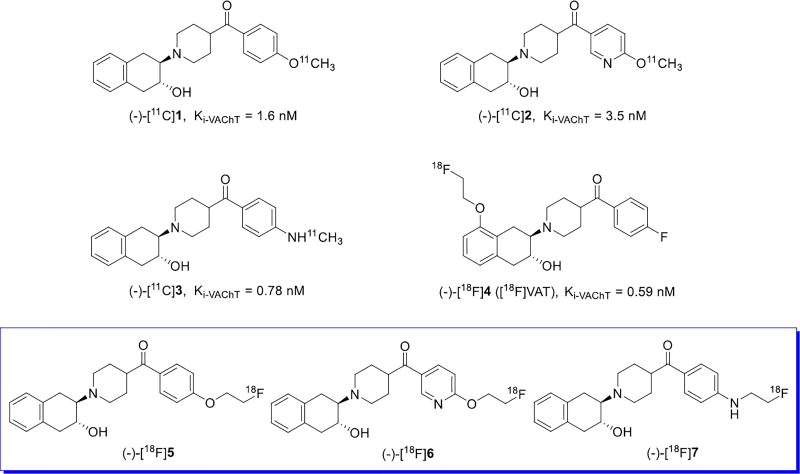

Acetylcholine was the first neurotransmitter discovered to be related to motor and memory functions.1, 2 The loading of acetylcholine into secretory organelles in presynaptic cholinergic neurons is regulated by the vesicular acetylcholine transporter (VAChT), which is a transmembrane binding protein consisting of 550 amino acid polypeptides.3, 4 Cholinergic dysfunction in the central nervous system (CNS) is closely associated with cognitive dysfunction in dementias such as Alzheimer’s disease (AD), Parkinson’s disease (PD), and Progressive Supranuclear Palsy.5, 6 The depletion of presynaptic cholinergic function including VAChT activity is considered to be more clinically significant than changes in postsynaptic cholinergic functions.7–9 Quantification of VAChT provides a reliable biomarker of cholinergic dysfunction related to cognitive impairment. The aminoalcohol compound, trans-2-(4-phenylpiperidino)cyclohexanol (vesamicol), which non-competitively inhibits the transport of acetylcholine through binding to VAChT, has served as the lead structure for the development of numerous VAChT radioligands.10, 11 Positron emission tomography (PET) and single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) are noninvasive and sensitive imaging modalities for mapping neuroreceptors, enzyme, and transporter expression levels, characterizing pharmacokinetics, and assessing drug occupancy of specific binding sites in living subjects. Most PET and SPECT VAChT tracers are based on the vesamicol scaffold.11 Many proposed VAChT radioligands lack selectivity for VAChT over sigma receptors because the VAChT and sigma receptor binding sites have similar pharmacophores closely resembling vesamicol.12 Furthermore, implementation of the selective ligands has been hampered due to slow brain equilibrium kinetics, fast metabolism, and high plasma protein binding which have precluded studies in human patients. Prior to the approval of [18F]VAT for first-in-man studies, only two radioligands, (−)-5-[123I]iodo-benzovesamicol ((−)-[123I]IBVM)13 and (−)-[18F]fluoroethoxy-benzovesamicol ((−)-[18F]FEOBV),14 had been used with limitations to map VAChT expression in human subjects. We have evaluated several VAChT radioligands in preclinical models,15–22 and recently reported three potent and selective (Ki-VAChT < 5 nM, selectivity over σ receptor > 35-fold) carbon-11 labeled enantiopure carbonyl-containing benzovesamicol analogues ((−)-[11C]1–3, Figure 1). Acute biodistribution, autoradiography, and metabolism studies in male Sprague-Dawley rats, and 2-h dynamic PET imaging studies in nonhuman primates (NHPs) revealed favorable imaging properties for the carbon-11 tracers.18,19,23 Nevertheless, the short half-life of carbon-11 (20.4 min) requires that carbon-11 labeled radiopharmaceuticals be produced close to the PET imaging facilities. The longer half-life of fluorine-18 (109.8 min) allows multiple-step synthesis and distribution of fluorine-18 labeled radiopharmaceuticals within a 3–4 h driving distance. Thus, development of a fluorine-18 labeled radiopharmaceutical for VAChT that penetrates the blood brain barrier would facilitate imaging studies in a wider population of patients with dementia. [18F]VAT ((−)-[18F]4, Figure 1) demonstrated preclinical specificity for VAChT in rodent and nonhuman primates; radiation dosimetry estimation indicated the acceptable dose of [18F]VAT should generate high quality human images.15, 24 We have successfully automated the production of [18F]VAT in a current Good Manufacturing Practice (cGMP) facility and obtained exploratory Investigational New Drug (exploratory IND) approval from the Food and Drug Administration (FDA).21 The suitability of [18F]VAT implementation in human diseases is currently under investigation in human subjects. To make sure we identify the most promising VAChT radiopharmaceutical for clinical use, herein we reported our investigation of three new fluorine-containing enantiomers of the previously reported carbon-11 carbonyl-containing benzovesamicol VAChT analogues.15, 16, 23 We used the strategy of replacing the methoxy group with a fluoroethoxy or fluoroethylamino group to generate the compounds 5–7 and their fluorine-18 labeled counterparts as shown in Figure 1.25–27 Chiral resolution of the racemic isomers was performed. The binding affinity of each enantiomer was determined and the most potent and selective compound, (−)-7 was radiolabeled with fluorine-18; brain uptake of (−)-[18F]7 was investigated in a nonhuman primate.

Figure 1.

Structures of reported enantiomeric VAChT tracers (−)-[11C]1–3, (−)-[18F]4 and new enantiomeric VAChT tracers (−)-[18F]5–7

2. Results and discussion

2.1. Chemistry

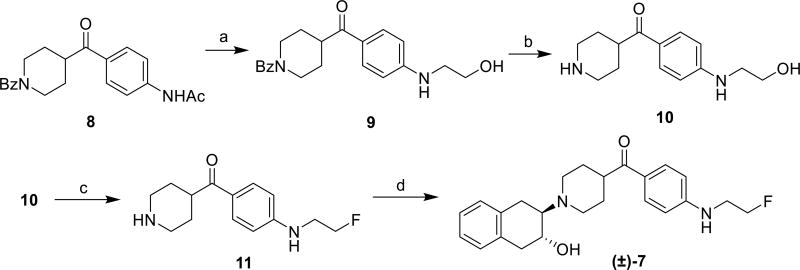

Syntheses of the target racemic compounds 5 and 6 were achieved by following previous publications.22, 23, 27 Compound (±)-7 was synthesized as described in Scheme 1. Treatment of N-(4-(1-benzoylpiperidine-4-carbonyl)phenyl)acetamide 8 28 with NaH and 2-bromoethyl benzoate produced the N-ethyl alcohol 9, which was subjected to acidolysis to yield compound 10. Fluorination of the primary alcohol in compound 10 was achieved by the reaction with diethylaminosulfur trifluoride (DAST) in 62% yield to give compound 11. Ring opening of the epoxy 1a,2,7,7a–tetrahydronaphtho[2,3-b]oxirene16 with compound 11 provided the target compound (±)-7 in 77% yield. Optically pure enantiomers of compounds (±)-5–7 were obtained by normal phase chiral separation using a Chiralcel OD column. Optimization of the conditions for chiral high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) separation of the enantiomers focused on identifying the most appropriate chiral stationary phase (CSP), mobile phase, and flow rate. Many CSPs are commercially available. The tris(3,5-dimethylphenylcarbamate) cellulose coated silica column (Chiralcel OD) was selected based on the structure of the racemic compounds; (±)-5–7 possess a hydroxyl group on the chiral center, the Chiralcel OD column is known to be highly efficient in resolving compounds with similar hydroxyl chirality.29 A mixture of hexane and 2-propanol was used for the mobile phase. Under these separation conditions, the enantiomers of (±)-5–7 were successfully resolved with an enantiomeric excess > 95% as determined by chiral analytical HPLC (Chiralcel OD column, 250 × 4.6 mm).

Scheme 1.

Reagents and conditions: (a) NaH, BrCH2CH2OBz, THF, 60 °C, overnight, 46%; (b) HCI/EtOH, reflux, 3 d, 84%; (c) diethylaminosulfur trifluoride (DAST), rt, 4 h, 62%; (d) 1a,2,7,7a-tetrahydronaphtho[2,3-b]oxirene, Et3N, EtOH, reflux, 3 d, 77%.

2.2. In vitro binding studies

To determine the binding affinities and selectivity of the resolved enantiomers, a competitive binding assay was performed for VAChT, σ1 and σ2 receptors. VAChT binding (Ki, nM) was measured by displacement of (−)-[3H]vesamicol in PC12A123.7 cells expressed human VAChT, as described.15 The σ1 and σ2 binding affinities were conducted by displacement of (+)-[3H]pentazocine in rat brain and [3H]-1,3-di-ortho-tolylguanidine ([3H]DTG) in the presence of 1 µM (+)-pentazocine in guinea pig membranes, respectively.30 The results are summarized in Table 1. The minus isomers were generally more potent than the plus isomers or the racemic counterparts for VAChT; (−)-isomers of these new ligands showed 7–23 fold higher binding affinities than the (+)-counterparts, and were 2–8 fold more potent than the racemic compounds. Similar binding trends have been observed for other VAChT compounds with similar structures.15, 29 Enantiomers (+)-6, (−)-6, (+)-7, (−)-7 displayed good potency for VAChT with Ki value less than 5 nM; at 4.35, 0.37, 2.31, and 0.31 nM, respectively; (−)-7 was the most potent compound with Ki value of 0.31 nM for VAChT. In addition, (−)-7 displayed >5000-fold selectivity for VAChT over σ1 receptor although enantiomeric (+)-5, (−)-5, (+)-6, (−)-6 had moderate to good selectivity over σ1 receptor (6–430-folds). All racemic compounds and their enantiomeric counterparts showed good selectivity for VAChT over σ2 receptors (>500-fold). Compared to our reported carbon-11 labeled VAChT compounds, (−)-7 was 2-fold more potent than (−)-3, 5-fold more potent than (−)-1 with much higher selectivity than (−)-1 over σ1/σ2 receptors. Compounds 5–7 also have appropriate lipophilicity with the logP values within 2–3, suggesting they may be able to penetrate the blood brain barrier and enter into the brain. Compound (−)-[18F]7 was chosen for radiolabeling and brain uptake was further evaluated in a NHP.

Table 1.

Binding affinities of racemic and enantiomeric compounds 5–7 for VAChT, σ1,and σ2 receptors

| Entry | Compound | Ki, nM a

|

σ1/VAChT | σ2/VAChT | log P b | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VAChT | σ1 | σ2 | |||||

| 1 | (±)-5c | 38.0 ± 3.8 | 2120 ± 50 | 1860 ± 140 | 56 | 49 | 2.87 |

| (+)-5 | 396 ± 120 | 7380 ± 1240 | 3410 ± 270 | 19 | 9 | ||

| (−)-5 | 17.0 ± 1.8 | 7360 ± 710 | 4970 ± 180 | 433 | 292 | ||

|

| |||||||

| 2 | (±)-6d | 1.74 ± 0.32 | 13.2 ± 0.2 | 1890 ± 240 | 8 | 1086 | 3.15 |

| (+)-6 | 4.35 ± 0.51 | 24.7 ± 3.9 | 2960 ± 410 | 6 | 680 | ||

| (−)-6 | 0.37 ± 0.04 | 7.23 ± 0.36 | 5840 ± 770 | 20 | 15784 | ||

|

| |||||||

| 3 | (±)-7 | 2.68 ± 0.23 | --- | --- | --- | --- | 2.91 |

| (+)-7 | 2.31 ±0.20 | 1250 ± 70 | >10,000 | 541 | 4329 | ||

| (−)-7 | 0.31 ±0.03 | 1870 ± 250 | 5480 ± 140 | 6032 | 17677 | ||

2.3. Syntheses of precursors and radiosyntheses of (±)-[18F]7 or (−)-[18F]7

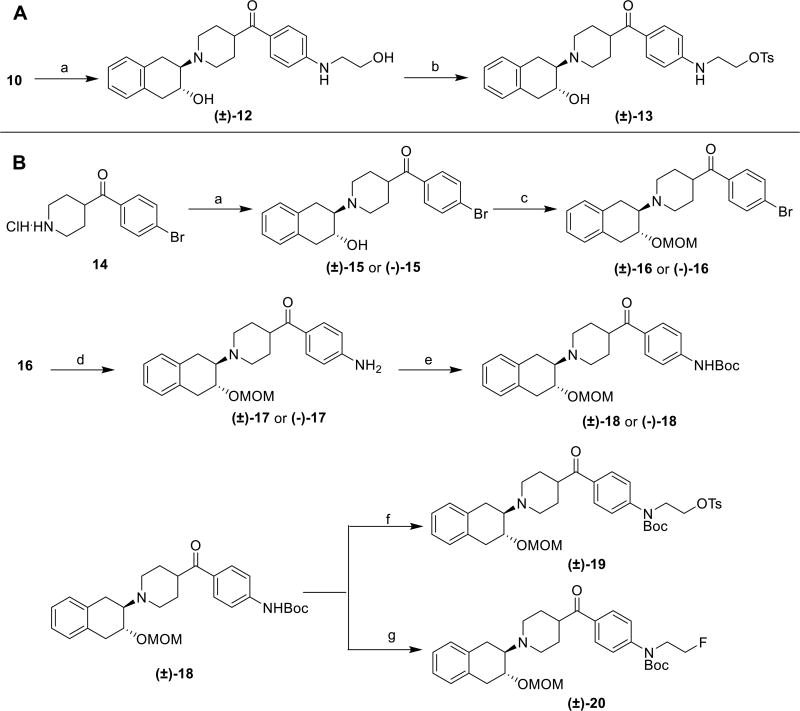

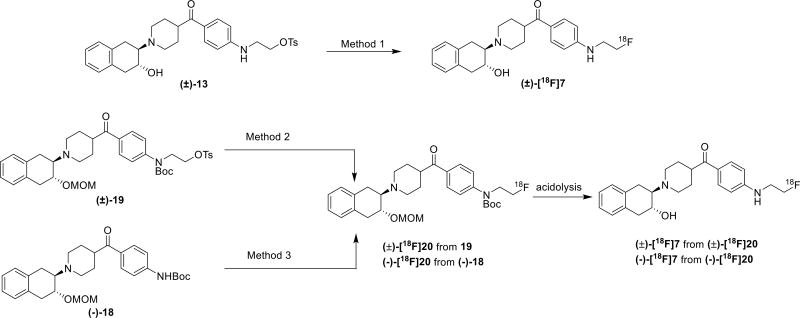

The synthesis of the radiolabeling precursor commenced from the intermediate 10. The tosylate precursor for one step radiolabeling with (±)-[18F]7 was first considered because tosylate/fluoride displacement is the most convenient fluorine incorporation method since it requires a short radiolabeling time thereby reducing radiation exposure. Reaction of compound 10 with 1a,2,7,7a–tetrahydronaphtho[2,3-b]oxirene gave compound (±)-12, which was reacted with tosyl chloride to provide the radiolabeling precursor (±)-13 (Scheme 2, A). The radiosynthesis of (±)-[18F]7 using the precursor (±)-13 was conducted in different solvents including acetonitrile, dimethylformamide (DMF), and dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and appropriate temperature (Scheme 3). However, no (±)-[18F]7 was collected from a semi-preparative HPLC purification system except an unknown nonradioactive polar peak was observed from the HPLC UV chromatograph; most of the precursor were decomposed under these conditions (Table 2, entries 1–3). Only a small amount of product (0.9% decay corrected yield, Table 2, entry 4) was collected when 1,4-dioxane was used as the reaction solvent. The discouraging radiochemical yield was probably attributed to the instability of the tosylate precursor under heated conditions by which intramolecular ring closure reaction to form aziridine or benzenaminium caused the failure of fluorine-18 incorporation. We envisioned that the second amine would be deprotonated in the presence of strong basic fluoride anion and led to decomposition of the precursor prior to the nucleophilic substitution reaction. To overcome the challenge of the radiosynthesizing (±)-[18F]7, next we tried to mask the second amine with a tert-butyloxycarbonyl protecting group (Boc) to increase the stability of the precursor under heated condition. The synthesis of the second radiolabeling precursor (±)-19 was outlined in Scheme 2B. Reaction of commercially available 14 with 1a,2,7,7a–tetrahydronaphtho[2,3-b]oxirene offered compound (±)-15 in 93% yield. Protection of the secondary hydroxyl group in compound (±)-15 with a methoxymethyl (MOM) group afforded compound (±)-16, which was reacted with ammonium hydroxide under copper iodide catalysis, followed by Boc anhydride protection that yielded a secondary amine (±)-18. Reaction of (±)-18 with ethylene ditosylate at 40 °C gave the Boc protected tosylate precursor (±)-19 in 75% yield. The order for adding the reagents and reaction temperature were crucial for reliable synthesis of the desired product (±)-19. Otherwise production of 2-oxazolidinone or vinyl 4-methylbenzenesulfonate may be the predominate product.31 By similar strategy, the standard reference for the radiolabeling intermediate (±)-20 was obtained by the reaction of compound (±)-18 with the 2-fluoroethyl tosylate. Since the minus enantiomer was more potent for VAChT, we also conducted chiral separation of compound (±)-15 using a Chiralcel OD column to obtain the corresponding resolved minus compound (−)-15. The optically pure (−)-16, (−)-17 and (−)-18 were synthesized using the same procedure as their corresponding racemic compounds shown in Scheme 2B. Compound (−)-18 was also used as the radiolabeling precursor for Method 3.

Scheme 2.

Reagents and conditions: (a) 1a,2,7,7a-tetrahydronaphtho[2,3-b]oxirene, Et3N, EtOH, reflux, 77% for compound (±)-12, 93% for compound (±)-15; (b) TsCl, 4-dimethylaminopyridine (DMAP), Et3N, 59%; (c) chloromethyl methyl ether (MOMCl), iPr2NEt, DMAP, CH2Cl2, 87% for (±)-16, 83% for (−)-16; (d) NH3·H2O, Cul, K3PO4, 90 °C, 83% for (±)-17, 77% for (−)-17; (e) Boc2O, Et3N, DMAP, CH2Cl2, 66% for (±)-18, 50% for (−)-18; (f) TsOCH2CH2OTs, NaH, DMF, 40 °C, 75%; (g) TsOCH2CH2F, NaH, DMF, 60 °C, 59%.

Scheme 3.

Radiolabeling of (±)-[18F]7 and (−)-[18F]7 using three different methods.

Table 2.

Condition screening for the radiolabeling of (±)-[18F]7 ((−)-[18F]7).

| Entry | Base | Solvent | Temperature or Microwave |

Results | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Method 1 for (±)-[18F]7 | For (±)-[18F]7 | ||||

|

| |||||

| 1 | K2CO3 | MeCN | 80 °C | N.P. a | |

| 2 | K2CO3 | DMF | 80 °C | N.P. | |

| 3 | K2CO3 | DMSO | 90 °C | N.P. | |

| 4 | K2CO3 | 1,4-dioxane | 90 °C | 0.9% b | |

|

| |||||

| Method 2 for (±)-[18F]7 | For (±)-[18F]20c | For (±)-[18F]7d | |||

|

| |||||

| 5 | K2CO3 | DMSO | 110 °C | 4.8% e | N/Af |

| 6 | K2CO3 | DMSO | 110 °C | 5.3% g | N/A |

| 7 | K2CO3 | MeCN | 110 °C | 16% | 4% |

|

| |||||

| Method 3 for (−)-[18F]7 | |||||

|

| |||||

| 8 | TBAHCO3 | MeCN | 110 °C | 11% h | N/A |

| 9 | TBAHCO3 | MeCN | 110 °C | 21% i(8%) | N/A |

| 10 | TBAHCO3 | MeCN | 110 °C | 29% j(9%) | N/A |

| 11 | TBAHCO3 | tBuOH/MeCN (3/1, v/v) | 110 °C | 6.0% | N/A |

| 12 | TBAHCO3 | DMSO | 65 W, 120 s × 2 | 10% | N/A |

| 13 | TBAHCO3 | DMF | 50 W, 120 s × 2 | 16% (7%) | N/A |

| 14 | Cs2CO3 | DMSO | 100 °C | 1.9% | N/A |

| 15 | NaH | DMF | 85 °C | 47% (37%) | 11% |

| 16 | NaH | DMF | 110 °C | 2.1% k | N/A |

Note:

N.P., no product was detected by HPLC;

decay corrected yield determined by HPLC;

[18F]fluoride incorporation yield determined by radioTLC otherwise noted, the yields in the parenthesis are referred to the decay corrected yield determined by HPLC for the second radiolabeling;

decay corrected yield determined by HPLC;

reaction time 10 min;

N/A, reaction not performed;

reaction time 20 min;

reaction time 10 min;

reaction time 20 min;

the precursor was added in three portions;

decay corrected yield determined by HPLC

Starting with the Boc-protected precursor (±)-19, we tested the radiosynthesis of (±)-[18F]7 in DMSO at 110 °C, using potassium carbonate as the base. The conversion was less than 5% monitored by radioactive thin-layer chromatography (TLC); longer reaction times did not improve the incorporation of [18F]fluoride (Table 2, entries 5–6). When acetonitrile was used as the solvent, the fluorine-18 incorporation was increased to 16%. Acidolysis of the MOM and Boc-protecting groups provided the target tracer (±)-[18F]7 in radiochemical yield of 4% with decay correction. The yield was remarkably improved compared to our initial attempt, but the dose (~ 0.07 GBq) of the final radioactivity product is not sufficient for PET studies in nonhuman primates , which typically require an injected dose of 0.07 – 0.3 GBq.32 The precursor (±)-19 decomposed during storage as identified with TLC, even when the tosylate precursor was stored in the freezer. Others have reported that nitrogen-containing tosylate is prone to decompose under storage and makes the reproducibility and reliability for radiolabeling uncertain.31 We reported a two-pot, two-step synthesis of [18F]VAT in a cGMP facility that had good reproducibility and afforded high quality [18F]VAT suitable for clinic investigation; this procedure improved the radiochemical yield and avoided decomposition of the precursor.21 Therefore, we decided to introduce the [18F]fluoroethyl moiety in situ starting with the enantiomeric precursor (−)-18. Nucleophilic substitution of ethylene ditosylate with dried [18F]fluoride afforded 2-[18F]fluoroethyl tosylate in a reliable yield (55 ± 3%, n > 10, decay corrected to the end of synthesis); typically 2.6 – 3.0 GBq of 2-[18F]fluoroethyl tosylate was collected from semi-preparative HPLC fraction starting from 5.6 – 6.7 GBq of dried K[18F]fluoride. Next we optimized the reaction conditions for the 2-[18F]fluoroethyl incorporation with (−)-18. Using tetrabutylammonium hydrogen carbonate as the base, acetonitrile as reaction solvent, at 110 °C for 10 min, approximately 11% incorporation of [18F]fluoride was achieved; increasing the reaction time to 20 min, increased the conversion of [18F]fluoride to 21% monitored by radioactive TLC. After purification using reversed phase semi-preparative HPLC, an 8% yield of (−)-[18F]20 (decay corrected to the end of synthesis) was achieved (Table 2, entries 8–9). In consideration of the competition between decomposition of the precursor (−)-18 and [18F]fluoride incorporation, the precursor was added to the reaction vessel via a stepwise method. A slightly higher incorporation yield was observed when the precursor was added in three portions, this approach afforded (−)-[18F]20 with yield of 9% (decay corrected) (Table 2, entry 10). Because the radiochemistry yield of intermediate (−)-[18F]20 was less than 10% and one additional acidolysis step was required to obtain (−)-[18F]7, we explored improvements that would afford a higher radiochemical yield of (−)-[18F]7. We initially replaced the acetonitrile reaction solvent with tert-butanol/acetonitrile co-solvents, but the incorporation yield of [18F]fluoride was not sufficiently improved (Table 2, entry 11). Microwave used to assist the reaction using either DMSO or DMF as solvent also failed to improve the radiochemical yield (Table 2, entries 12–13). Replacing potassium carbonate base with cesium carbonate decreased the [18F]fluoride incorporation (Table 2, entry 14). Fortunately, when using DMF as solvent and sodium hydride as the base, and heating at 85 °C, the incorporation yield of [18F]fluoride was improved to 47%, and radiochemical yield of (−)-[18F]20 was 37% with decay correction. Further acidolysis of (−)-[18F]20 with 6M aqueous HCl afforded (−)-[18F]7 with 11% radiochemical yield after decay correction. Increasing the temperature to 110 °C significantly reduced the [18F]fluoroethyl incorporation for the second step, probably due to the decomposition of the precursor or the accelerated elimination of 2-[18F]fluoroethyl tosylate under higher temperature (Table 2, entries 15–16). The final product of (−)-[18F]7 was authenticated by co-injection of the tracer with nonradiolabeled standard compound (−)-7. Overall, the three step procedure of making (−)-[18F]7 was achieved with a yield of 9 – 11% (decay corrected to the end of synthesis) in 150 min including the [18F]fluoride drying step, with specific activity of 37 – 148 GBq/µmol and radiochemical purity > 98%.

A tosylate precursor is usually employed for one-step fluorine-18 radiolabeling by a tosylate/[18F]fluoride displacement reaction which reduces processing time and radiation exposure to the radiochemists. In our method for (±)-[18F]7, the one-step fluorine-18 radiolabeling using the secondary amine precursor (±)-13 afforded only a trace amount of (±)-[18F]7 under different reaction conditions; most [18F]fluoride remained intact in the Alumina N Sep-Pak cartridge with significant decomposition of the precursor. To avoid the quick decomposition of the precursor, we protected the secondary amine using a Boc group; when starting with this Boc-protected precursor, the [18F]fluoride incorporation yield was remarkably increased and (±)-[18F]7 was produced at approximately 4% radiochemical yield after HPLC purification. However, the deliverable radioactivity of (±)-[18F]7 was not sufficient for routine PET studies in NHPs. In addition, the stability of the tosylate precursor would be a concern for long time storage. With our successful experience in the production of [18F]VAT under a cGMP facility, we adopted a stepwise strategy to introduce the [18F]fluoroethyl moiety into the stable precursor (−)-18, resulted from enantiomeric intermediate (−)-15. Enantiomeric resolution of compound 15 using a normal phase Chiralcel OD column resulted in an excellent baseline separation of the two isomers. Base plays a critical role in [18F]fluoroethyl incorporation with (−)-18, and sodium hydride was the optimized choice. Due to the potential competition between the intramolecular ring-closure and elimination of 2-[18F]fluoroethyl tosylate, the heating temperature is also critical to achieve a higher radiochemistry yield of (−)-[18F]7 (Scheme 3). Together, the three-step radiolabeling procedure produced (−)-[18F]7 at ~10% radiochemistry yield after decay correction, with high chemical purity, delivering sufficient radioactive dose of (−)-[18F]7 for NHP PET studies. While the dose we obtained was enough for animal studies, the two-pot three-step radiolabeling strategy is laborious; the translation of these procedures into a cGMP facility would be challenging compared to [18F]VAT. The procedure could be improved by a simplified radiosynthesis of the intermediate 2-[18F]fluoroethyl tosylate, which can be purified by solid phase extraction method without HPLC purification.26 Another strategy that could prove useful involves the production of 2-[18F]fluoroethylamine derivative, followed by coupling with a halogen-substituted vesamicol analogue.

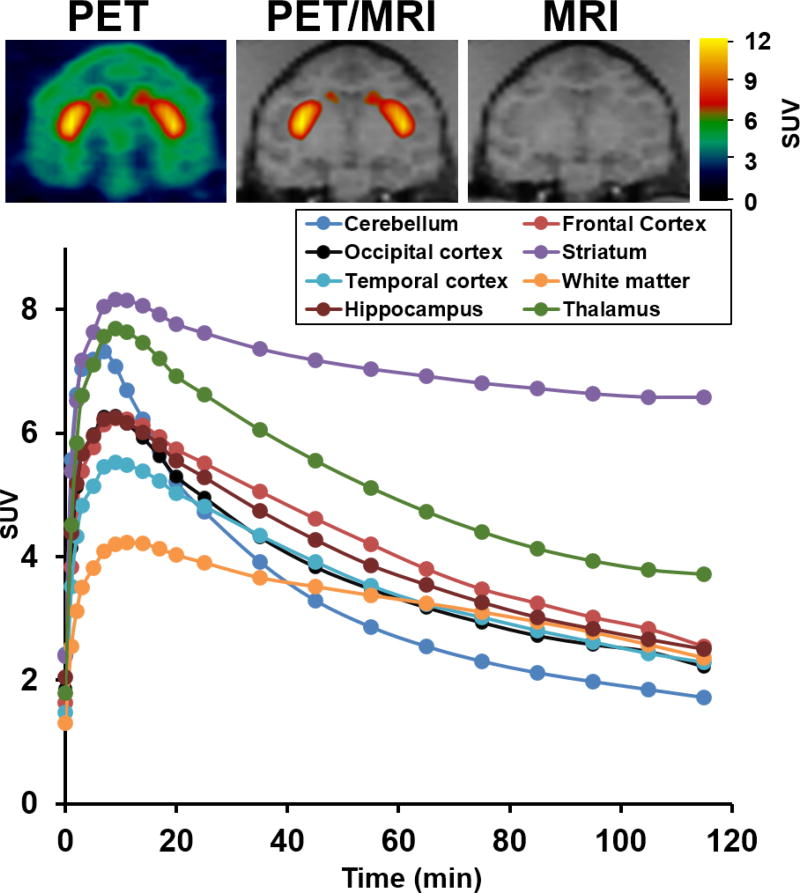

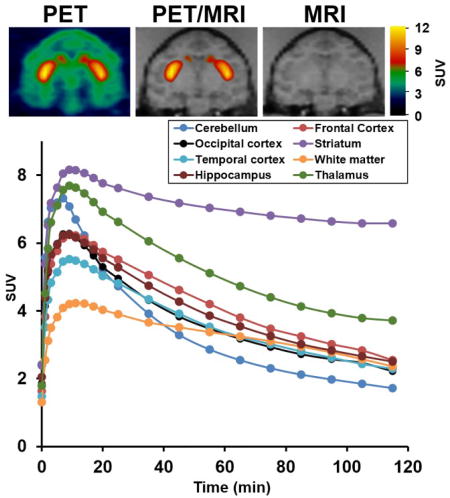

2.4. MicroPET studies in nonhuman primates

Two PET studies of (−)-[18F]7 in a male cynomolgus macaque (Figure 2) were performed with a greater than 4-week interval between the two PET scans. The microPET imaging results demonstrated that (−)-[18F]7 was able to penetrate the blood brain barrier and had the highest accumulation in the VAChT-enriched striatum. The lowest tracer uptake was observed in the cerebellum, which is consistent with VAChT distribution in the brain and our previous PET studies;15, 24, 25, 30, 33 cerebellum was chosen as the reference region for imaging modeling analysis for the reference tissue model.34 The uptake of radioactivity peaked at ~10 min in most regional brains including striatum, cortex, hippocampus, and thalamus, followed by a quick washout kinetics except in the VAChT-enriched region striatum for which activity was retained for ~ 100 min. The thalamus had the second highest uptake of radioactivity compared to cortex and hippocampus, this observation was consistent with the distribution of other VAChT tracers in the brain NHPs, for example (−)-[18F]FEOBV.14 Furthermore, negligible skull uptake of the radioactivity was observed in the image of the NHP, indicating no in vivo metabolic defluorination of (−)-[18F]7. Overall, the microPET studies in NHPs suggested (−)-[18F]7 has favorable kinetics in the NHP brain and deserves further investigation.

Figure 2.

MicroPET study of (−)-[18F]7 in a male cynomolgus macaque. (A) Representative image top panel left: PET image; middle: co-registration of MRI and PET, right: MR image. (B) Tissue time-activity curve (TAC). Striatum has the highest uptake and the cerebellum has the lowest uptake.

3. Experimental

3.1. Chemistry

All solvents and reagents were obtained commercially and used as received, unless otherwise stated. All anhydrous reactions were carried out in oven-dried or flame-dried, and nitrogen purged glassware. Reactions were monitored by thin layer chromatography (TLC) using silica gel 60 F254 glass plates (EMD Chemicals Inc.). Flash column chromatography was performed over silica gel (32–63 µm), HPLC grade solvents were used for chromatography. 1H NMR and 13C NMR spectra were carried out on a Varian Mercury-VX 400 MHz spectrometer. The 13C NMR spectra were recorded at 101 MHz. The chemical shifts are reported as δ values (ppm) relative to tetramethylsilane (TMS) as an internal reference. The Spectra System was used for both analytical and semi-preparative HPLC. A Chiralcel OD normal phase HPLC column was used to separate the enantiomeric isomers from racemic compounds. The optical rotation for each enantiopure compound was determined on an automatic polarimeter (Autopol 111, Rudolph Research, Flanders, NJ).

General procedure for the enantiomeric resolution by chiral HPLC

Enantiomeric resolution of compound was accomplished by HPLC using a 250 mm × 10 mm Chiralcel OD column (UV 254 nm). The optical purity was determined by chiral analytical HPLC with the same mobile phase (Chiralcel OD column, 250 mm × 4.6 mm, 1 mL/min, UV 254 nm). The oxalate salts were prepared by following the procedure: to the resolved optically pure compound in 1.0 mL dichloromethane was added a solution of oxalic acid (1.0 eq.) in 1.0 mL ethyl acetate. The resulting mixture was stirred at room temperature for 10 min, and the precipitate was collected by vacuum filtration.

Racemic compounds (4-(2-fluoroethoxy)phenyl)(1-(3-hydroxy-1,2,3,4-tetrahydronaphthalen-2-yl)piperidin-4-yl)methanone, (±)-5 and (6-(2-fluoroethoxy)pyridin-3-yl)(1-(3-hydroxy-1,2,3,4-tetrahydronaphthalen-2-yl)piperidin-4-yl)methanone, (±)-6 were synthesized by following our published procedures18, 20, 22, 23, 27 and resolved by a Chiralcel OD column.

HPLC resolution of Compound (±)-5

(±)-5

1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD) δ 7.89 (d, J = 8.9 Hz, 2H), 7.00 – 6.95 (m, 6H), 4.64 (td, J = 47.6, 4.0 Hz, 2H), 4.21 (td, J = 28.8, 4.0 Hz, 2H), 3.87 (td, J = 9.3, 5.8 Hz, 1H), 3.35 – 3.30 (m, 1H), 3.07 (dd, J = 15.8, 5.6 Hz, 1H), 2.96 – 2.86 (m, 3H), 2.82 – 2.73 (m, 3H), 2.67 (dd, J = 15.8, 9.6 Hz, 1H), 2.54 (dd, J = 11.5, 9.6 Hz, 1H), 1.80 – 1.65 (m, 4H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, CD3OD) δ 202.1, 162.7, 134.8, 133.7, 130.44, 130.39, 129.0, 128.3, 125.7, 125.7, 114.1, 81.5 (d, J = 169.7 Hz), 67.4 (d, J = 20.2 Hz), 66.5, 66.4, 50.4, 46.0, 43.0, 37.7, 29.0, 28.8, 26.9. HRMS (ESI) Calcd for C24H29FNO3 [M+H]+ 398.2126, found: 398.2122.

HPLC condition

Chiralcel OD column (250 × 10 mm) consisting of mobile phase isopropanol/hexane (1/1, v/v) at a flow rate of 4.0 mL/min. 23 mg of (+)-5 (ee 95.0%) and 28 mg of (−)-5 (ee 96.2%) were obtained as light yellow solids.

(+)-5

Melting point (MP): 121–123 °C. The optical rotation of (+)-5 was [α]D20 = +49.2° (0.80 mg/mL in MeOH).

(−)-5

MP: 122–124 °C. The optical rotation of (−)-5 was [α]D20 = −53.1° (1.47 mg/mL in MeOH).

HPLC resolution of Compound (±)-6

(±)-6

1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3COCD3) δ 8.46 (d, J = 2.5 Hz, 1H), 7.84 (dd, J = 9.6, 2.7 Hz, 1H), 6.98 – 6.93 (m, 4H), 6.35 (d, J = 9.6 Hz, 1H), 4.63 (dt, J = 48.0 Hz, 4.2 Hz, 2H), 4.27 (dt, J = 26.1, 4.8 Hz, 2H), 3.71 (td, J = 9.9, 5.8 Hz, 1H), 3.17 – 3.10 (m, 1H), 3.03 (dd, J = 16.1, 5.8 Hz, 1H), 2.89 – 2.82 (m, 1H), 2.79 – 2.67 (m, 4H), 2.64 – 2.51 (m, 2H), 2.35 (td, J = 11.5, 2.3 Hz, 1H), 1.78 – 1.56 (m, 4H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, CD3COCD3) δ 197.4, 161.5, 144.3, 138.0, 135.2, 134.2, 128.90, 128.85, 125.8, 125.7, 119.3, 115.6, 81.1 (d, J = 167.7 Hz), 66.1 (d, J = 96.0 Hz), 51.4, 50.3, 50.1, 44.9, 42.7, 38.0, 26.2. MP 86 – 88 °C. HRMS (ESI) Calcd for C23H28FN2O3 [M+H]+ 399.2078, found: 399.2075.

HPLC condition

Chiralcel OD column (250 × 10 mm) consisting of mobile phase isopropanol/hexane (1/1, v/v) at a flow rate of 4.0 mL/min. 9.0 mg of (+)-6 (ee > 98%) and 8.0 mg of (−)-6 (ee > 98%) were obtained as viscous gels.

(+)-6

The optical rotation of (+)-6 was [α]D20 = +38.7° (3.59 mg/mL in MeOH). Anal. Calcd for C23H27FN2O3 • C2H2O4: C, 61.47; H, 5.98; N, 5.73. Found: C, 58.83; H, 5.71; N, 5.40.

(−)-6

The optical rotation of (−)-6 was [α]D20 = −38.6° (0.41 mg/mL in MeOH). Anal. Calcd for C23H27FN2O3 • C2H2O4: C, 61.47; H, 5.98; N, 5.73. Found: C, 59.69; H, 6.02; N, 5.74.

(1-Benzoylpiperidin-4-yl)(4-((2-hydroxyethyl)amino)phenyl)methanone 9

Sodium hydride (239 mg, 6.0 mmol) was added to a solution of 8 (698 mg, 2.0 mmol) in THF (25 mL) under room temperature. The mixture was heated up to 60 °C, and then 2-bromoethyl benzoate (303 mg, 1.32 mmol) was added into the reaction mixture. The resulting mixture was stirred at 60 °C overnight. All volatiles were removed under reduced pressure. Water (20 mL) was added to the residue, and the mixture was extracted with CH2Cl2 (20 mL × 3). The combined organic layers were dried over anhydrous sodium sulfate and concentrated under reduced pressure. The crude product was purified by silica gel column chromatography using ethyl acetate/hexane(1/1, v/v) and 175 mg 8 was recoved. This provided compound 9 (240 mg, 46%) as a pale yellow solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.38 (br, 5H), 7.10 (s, 2H), 6.69 – 6.46 (m, 2H), 4.72 – 4.30 (m, 4H), 4.23 – 4.02 (m, 1H), 3.86 – 3.54 (m, 3H), 3.53 – 3.17 (m, 3H), 2.58 (d, J = 57.9 Hz, 2H), 2.26 (d, J = 65.2 Hz, 2H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3): δ 199.5, 170.4, 166.7, 136.1, 133.3, 130.7, 129.7, 128.5, 126.8, 112.5, 63.0, 43.4, 42.6, 28.9, 28.5. MP 160 – 161 °C.

(4-((2-Hydroxyethyl)amino)phenyl)(piperidin-4-yl)methanone 10

A solution of 9 (240 mg, 0.68 mmol) in EtOH (6 mL) and concentrated hydrochloric acid (9 mL, 12 M) was heated to reflux for 3 d. All volatiles were removed under reduced pressure. The yellow residue was washed with Et2O (10 mL × 2), and the ethereal layer was discarded. To the residue was added NaOH (30 mL, 1 M) and it was then extracted with CH2Cl2 (20 mL × 3). The combined organic layers were washed using brine, dried over anhydrous sodium sulfate and concentrated under reduced pressure to give compound 10 (143 mg, 84%) as a yellow gel. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD δ 7.78 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 2H), 6.61 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 2H), 3.70 (t, J = 5.7 Hz, 2H), 3.48 – 3.41 (m, 1H), 3.28 (t, J = 5.7 Hz, 2H), 3.19 – 3.12 (m, 2H), 2.82 (td, J = 12.3, 2.3 Hz, 2H), 1.81 – 1.63 (m, 4H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, CD3OD) δ 200.9, 153.6, 130.7, 123.3, 111.0, 59.9, 44.7, 44.4, 41.5, 28.1. HRMS (ESI) Calcd for C14H21N2O2 [M+H]+ 249.1598, found: 249.1595.

(4-((2-Fluoroethyl)amino)phenyl)(piperidin-4-yl)methanone 11

Compound 10 (143 mg, 0 57 mmol) was dissolved in 1,2-dimethoxyethane (5 mL) and cooled to −50 °C. Diethylaminosulfur trifluoride (DAST, 111 mg, 0.69 mmol) in 1,2-dimethoxyethane (2 mL) was added dropwise. The resulting solution was stirred for 10 min under −50 °C, warmed up to rt and stirred for additional 4 h. To the reaction mixture was added saturated K2CO3 solution (20 mL). The product was extracted with CH2Cl2 (15 mL × 3). The combined organic layers were washed with brine, dried over anhydrous sodium sulfate and concentrated under reduced pressure. The crude product was purified by silica gel column chromatography using CH2Cl2/MeOH/Et3N (9/1/5%, v/v/v) to give compound 11 (90 mg, 62%) as a yellow oil. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3SOCD3) δ 7.75 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 2H), 6.89 (t, J = 5.6 Hz, 1H), 6.63 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 2H), 4.52 (dt, J = 47.6, 4.8 Hz, 2H), 3.58 – 3.53 (m, 1H), 3.46 – 3.36 (m, 2H), 3.23 – 3.20 (m, 2H), 2.98 – 2.92 (m, 2H), 1.81 – 1.67 (m, 4H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, CD3OD δ 199.5, 153.5, 130.7, 123.1, 111.0, 81.8 (d, J = 168.7 Hz), 43.2, 42.8 (d, J = 20.2 Hz), 39.4, 25.9. HRMS (ESI) Calcd for C14H20FN2O [M+H]+ 251.1551, found: 251.1552.

(4-((2-Fluoroethyl)amino)phenyl)(1-(3-hydroxy-1,2,3,4-tetrahydronaphthalen-2-yl)piperidin-4-yl)methanone (±)-7

To a solution of 11 (90 mg, 0.36 mmol) in EtOH (6 mL) was added Et3N (182 mg, 1.80 mmol) and 1a,2,7,7a–tetrahydronaphtho[2,3-b]oxirene (63 mg, 0.43 mmol). The resulting solution was refluxed for 3 d. The volatiles were removed under reduced pressure, and the residue was directly purified by silica gel column chromatography using hexanes/EtOAc (1/5, v/v) to EtOAc to give compound (±)-7 (110 mg, 77%) as an off white solid. MP: 182 – 184 °C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.79 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 2H), 7.19 −6.99 (m, 4H), 6.55 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 2H), 4.63 (t, J = 4.7 Hz, 1H), 4.52 – 4.48 (m, 2H), 4.23 (br, 1H), 3.83 – 3.77 (m, 1H), 3.51 – 3.41 (m, 2H), 3.27 – 3.15 (m, 2H), 2.92 – 2.88 (m, 1H), 2.84 – 2.79 (m, 1H), 2.77 – 2.68 (m, 4H), 2.33 (t, J = 10.7 Hz, 1H), 1.83 – 1.74 (m, 4H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 200.5, 151.5, 134.8, 134.0, 130.7, 129.3, 129.1, 126.1, 126.0, 125.7, 111.8, 82.1 (d, J = 168.7 Hz), 66.0 (d, J = 93.9 Hz), 52.1, 44.7, 43.6, 43.4, 43.1, 37.8, 29.8, 29.4, 26.0.

HPLC resolution of Compound (±)-7

HPLC condition

Chiralcel OD column (250 × 10 mm) consisting of mobile phase isopropanol/hexane (3/7, v/v) at a flow rate of 4.0 mL/min. 18.0 mg of (+)-7 (retention time 25 min; ee > 98%) and 20.2 mg of (−)-7 (retention time 42 min; ee > 98%) were obtained.

(+)-7

(+)-7 oxalate was obtained as a white solid (19.7 mg, 89 % yield). MP: 185 – 186 °C. The optical rotation of (+)-7 oxalate was [α]D20 = +47.5 ° (0.40 mg/mL in 1/1 acetonitrile/H2O). HRMS (ESI) Calcd for C24H30FN2O2 (free base, [M+H]+) 397.2286, found: 397.2288.

(−)-7

(−)-7 oxalate was obtained as a white solid (20.7 mg, 84%). MP: 190 – 193 °C. The optical rotation of (−)-7 was [α]D20 = −50.6 ° (0.53 mg/mL in 1/1 acetonitrile/H2O). HRMS (ESI) Calcd for C24H30FN2O2 (free base, [M+H]+) 397.2286, found: 397.2288.

(1-(3-Hydroxy-1,2,3,4-tetrahydronaphthalen-2-yl)piperidin-4-yl)(4-((2-hydroxyethyl)amino)phenyl)methanone (±)-12

To a solution of 10 (22 mg, 0.13 mmol) in EtOH (1 mL) was added Et3N (64 mg, 0.64 mmol) and 1a,2,7,7a–tetrahydronaphtho[2,3-b]oxirene (37 mg, 0.25 mmol). The resulting solution was refluxed overnight. The mixture was concentrated in vacuo and the residue was subjected to silica gel column chromatography using EtOAc as the eluent to give compound (±)-12 (27 mg, 77%) as a solid. MP 108 – 110 °C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.76 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 2H), 7.07 – 7.01 (m, 4H), 6.54 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 2H), 4.62 (br, 1H), 3.83 – 3.76 (m, 3H), 3.31 – 3.29 (m, 2H), 3.26 – 3.15 (m, 2H), 2.92 – 2.87 (m, 1H), 2.85 – 2.82 (m, 1H), 2.79 – 2.70 (m, 4H), 2.34 (t, J = 10.3 Hz, 1H), 1.88 – 1.73 (m, 4H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 200.6, 152.2, 134.7, 133.9, 130.7, 129.3, 129.1, 126.2, 126.0, 125.3, 111.8, 66.5, 65.6, 60.9, 52.0, 45.2, 44.8, 42.9, 37.8, 29.7, 29.3, 26.1. HRMS (ESI) Calcd for C24H31N2O3 [M+H]+ 395.2329, found: 395.2345.

2-((4-(1-(3-Hydroxy-1,2,3,4-tetrahydronaphthalen-2-yl)piperidine-4-carbonyl)phenyl)amino)ethyl 4-methylbenzenesulfonate (±)-13

To a solution of compound (±)-12 (17 mg, 0.044 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (1 mL) was added DMAP (13 mg, 0.11 mmol), 4-toluenesulfonyl chloride (TsCl, 10.1 mg, 0.053 mmol) successively at 0 °C, the reaction mixture was stirred at 0 °C for 2 h and then stored in a refrigerator overnight. The reaction was quenched with 2 M aqueous solution and extracted with CH2Cl2. The combined organic phase was washed with saturated sodium chloride solution and dried over anhydrous sodium sulfate. The concentrated residue was subjected to silica gel column chromatography using hexane/EtOAc (1/1, v/v) to provide compound (±)-13 (14 mg, 59% yield) as a gel. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3COCD3) δ 7.65 (dd, J = 21.0, 8.5 Hz, 4H), 7.26 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 2H), 6.99 – 6.93 (m, 2H), 6.50 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 2H), 5.80 (t, J = 6.0 Hz, 1H), 4.07 (t, J = 5.3 Hz, 2H), 3.75 – 3.69 (m, 1H), 3.44 – 3.40 (m, 2H), 3.23 – 3.17 (m, 1H), 3.04 (dd, J = 16.1, 5.8 Hz, 1H), 2.88 – 2.83 (m, 2H), 2.79 – 2.76 (m, 1H), 2.65 – 2.53 (m, 3H), 2.40 – 2.35 (m, 1H), 2.27 (s, 3H), 1.74 – 1.58 (m, 4H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, CD3COCD3) δ 199.3, 151.9, 144.9, 135.2, 134.2, 132.9, 130.3, 129.9, 128.92, 128.87, 127.8, 125.8, 125.7, 125.0, 111.3, 68.3, 66.7, 65.6, 51.7, 44.9, 42.8, 41.4, 38.0, 26.1, 20.6. HRMS (ESI) Calcd for C31H37N2O5S [M+H]+ 549.2418, found: 549.2442.

(4-Bromophenyl)(1-(3-hydroxy-1,2,3,4-tetrahydronaphthalen-2-yl)piperidin-4-yl)methanone (±)-15 and its chiral separation

To a solution of commercially available 14 (3.0 g, 9.9 mmol) in EtOH (45 mL) was added Et3N (5.7 mL, 40 mmol) and 1a,2,7,7a–tetrahydronaphtho[2,3-b]oxirene (1.7 g, 11.7 mmol). The resulting solution was refluxed overnight in a sealed tube. The reaction mixture was concentrated in vacuo and the residue was subjected to silica gel column chromatography using hexane/EtOAc/Et3N (1/1/2%, v/v/v) as the eluent to give compound (±)-15 (3.8 g, 93%) as a viscous oil. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.79 (d, J = 7.9 Hz, 2H), 7.60 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 2H), 7.14 – 7.07 (m, 4H), 4.18 (br, 1H), 3.86 (td, J = 9.9, 6.1 Hz, 1H), 3.32 – 3.21 (m, 2H), 3.00 – 2.93 (m, 1H), 2.89 – 2.76 (m, 6H), 2.40 (t, J = 10.7 Hz, 1H), 1.93 – 1.75 (m, 4H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 201.4, 134.7, 134.6, 133.9, 132.0, 129.8, 129.3, 129.1, 128.1, 126.2, 126.0, 66.5, 65.6, 51.8, 44.7, 43.7, 37.8, 29.4, 29.1, 26.1. HRMS (ESI) Calcd for C22H25BrNO2 [M+H]+ 414.1063, found: 414.1086. Racemic (±)-15 was resolved by a Chiralcel OD column (250 × 10 mm) consisting of mobile phase ethanol at a flow rate of 4.0 mL/min. The optical rotation of (−)-15 was [α]D20 = −26.9° (1.10 mg/mL in CHCl3).

(4-Bromophenyl)(1-(3-(methoxymethoxy)-1,2,3,4-tetrahydronaphthalen-2-yl)piperidin-4-yl)methanone (±)-16

To a solution of compound (±)-15 (1.14 g, 2.8 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (40 mL) was added iPr2NEt (2.9 mL, 16.5 mmol), DMAP (34 mg, 0.28 mmol), MOMCl (0.89 g, 11 mmol) successively at 0 °C. The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature overnight. Water was added to quench the reaction and the mixture was extracted with CH2Cl2. The combined organic phase was washed with saturated sodium bicarbonate solution, saturated sodium chloride solution, respectively, and dried over anhydrous sodium sulfate. The concentrated residue was subjected to silica gel column chromatography using hexane/EtOAc/Et3N (3/1/2%, v/v/v) as the eluent to provide compound (±)-16 (1.1 g, 87% yield) as a viscous oil. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.72 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 2H), 7.53 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H), 7.10 – 6.96 (m, 4H), 4.74 (dd, J = 15.5, 6.9 Hz, 2H), 4.03 – 3.91 (m, 1H), 3.37 (s, 3H), 3.12 (dt, J = 11.3, 5.1 Hz, 2H), 3.00 – 2.85 (m, 4H), 2.79 (dd, J = 16.0, 8.0 Hz, 2H), 2.58 – 2.40 (m, 2H), 1.82 – 1.64 (m, 4H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 201.6, 135.7, 134.8, 134.5, 131.9, 129.8, 128.4, 128.1, 127.9, 126.1, 126.0, 95.6, 73.7, 64.8, 55.7, 50.1, 48.0, 44.1, 35.8, 29.3, 29.1, 28.6. HRMS (ESI) Calcd for C24H29BrNO3 [M+H]+ 458.1325, found: 458.1351. (−)-16 was prepared according to the same procedure used for the synthesis of compound (±)-16. The spectra were identical with compound (±)-16. 366 mg of (−)-16 was obtained as a viscous oil in 83% yield. The optical rotation of (−)-16 was [α]D20 = −30.3° (1.00 mg/mL in CHCl3).

(4-Aminophenyl)(1-(3-(methoxymethoxy)-1,2,3,4-tetrahydronaphthalen-2-yl)piperidin-4-yl)methanone (±)-17

To a solution of compound (±)-16 (530 mg, 1.2 mmol) in DMF (4.5 mL) was added CuI (36 mg, 0.19 mmol), K3PO4 (589 g, 2.6 mmol) and concentrated NH3.H2O (3 mL) under nitrogen flow. The reaction was stirred at 90 °C in a sealed tube overnight. The reaction solution was cooled down to room temperature and extracted with CH2Cl2. The combined organic phase was washed with water, saturated aqueous sodium chloride, and dried over anhydrous Na2SO4. The organic phase was concentrated in vacuo and the residue was subjected to silica gel chromatography (hexane/EtOAc/Et3N = 1/1/2%, v/v/v) to give the target compound (±)-17 as a viscous oil (380 mg, 83% yield). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3COCD3) δ 7.64 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 2H), 6.96 – 6.94 (m, 4H), 6.56 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 2H), 5.31 (br, 2H), 4.63 (s, 2H), 3.93 (dd, J = 12.0, 6.3 Hz, 1H), 3.23 (s, 3H), 3.11 – 3.07 (m, 1H), 2.99 (dd, J = 16.0, 5.1 Hz, 1H), 2.89 – 2.77 (m, 3H), 2.74 – 2.64 (m, 3H), 2.49 – 2.39 (m, 2H), 1.65 – 1.44 (m, 4H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, CD3COCD3) δ 199.4, 153.1, 136.2, 135.0, 130.4, 128.2, 127.9, 125.8, 125.7, 124.9, 113.0, 95.3, 73.6, 64.9, 54.7, 50.1, 48.8, 42.9, 35.0, 29.8, 29.6. HRMS (ESI) Calcd for C24H31N2O3 [M+H]+ 395.2329, found: 395.2353. (−)-17 was prepared according to the same procedure used for the synthesis of compound (±)-17. The spectra were identical with compound (±)-17. 110 mg of (−)-17 was obtained as a viscous oil in 77% yield. The optical rotation of (−)-17 was [α]D20 = −44.2° (1.10 mg/mL in CHCl3).

Tert-butyl (4-(1-(3-(methoxymethoxy)-1,2,3,4-tetrahydronaphthalen-2-yl)piperidine-4-carbonyl)-phenyl)carbamate (±)-18

To a solution of (±)-17 (350 mg, 0.89 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (10 mL) was added DMAP (12 mg, 0.09 mmol), Et3N (0.37 mL, 2.7 mmol) successively. Boc2O (580 mg, 2.7 mmol) was added in one portion to the above solution. The reaction was stirred at rt overnight. The mixture was concentrated and subjected to silica gel chromatography (hexane/EtOAc/Et3N = 2/1/2%, v/v/v) to afford the product (±)-18 as a light yellow solid (290 mg, 66% yield). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.87 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 7.30 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 7.06 – 7.00 (m, 4H), 4.74 (dd, J = 15.3, 6.9 Hz, 2H), 4.00 – 3.95 (m, 1H), 3.36 (s, 3H), 3.18 – 3.09 (m, 2H), 2.92 – 2.88 (m, 4H), 2.82 – 2.76 (m, 2H), 2.58 – 2.43 (m, 2H), 1.79 – 1.68 (m, 4H), 1.37 (s, 9H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 201.8, 154.0, 151.4, 142.6, 135.7, 135.2, 134.6, 128.9, 128.4, 128.1, 128.0, 126.1, 126.0, 95.6, 84.1, 73.6, 64.8, 55.7, 50.1, 48.0, 44.3, 35.8, 29.4, 29.2, 28.5, 27.9. MP 76 – 78 °C. HRMS (ESI) Calcd for C29H39N2O5 [M+H]+ 495.2853, found: 495.2865. (−)-18 was prepared according to the same procedure used for the synthesis of compound (±)-18. The spectra were identical with compound (±)-18. 69 mg of (−)-18 was obtained as a light yellow solid in 50% yield. The optical rotation of (−)-18 was [α]D20 = −30.5° (1.00 mg/mL in CHCl3).

2-((Tert-butoxycarbonyl)(4-(1-(3-(methoxymethoxy)-1,2,3,4-tetrahydronaphthalen-2-yl)piperidine-4-carbonyl)phenyl)amino)ethyl 4-methylbenzenesulfonate (±)-19

To a suspension of NaH (2.3 mg, 0.1 mmol) in anhydrous DMF (1 mL) was added a solution of (±)-18 (40 mg, 0.08 mmol) in DMF (0.5 mL) at 0 °C. The solution was stirred at 0 °C for 10 min and then was added dropwise to a solution of ethylene ditosylate (60 mg, 0.16 mmol) in DMF (0.5 mL) at 40 °C. The reaction mixture was stirred at 40 °C for 30 min. Water was added to quench the reaction and the mixture was extracted with EtOAc. The combined organic phase was washed with water, saturated aqueous sodium chloride, and dried over anhydrous Na2SO4. The organic phase was concentrated in vacuo and the residue was subjected to silica gel chromatography to give the target compound (±)-19 as a light yellow gel (42 mg, 75% yield). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3COCD3) δ 7.82 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H), 7.62 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 2H), 7.33 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 2H), 7.21 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H), 7.01 – 6.94 (m, 4H), 4.66 (s, 2H), 4.09 (t, J = 5.3 Hz, 2H), 4.04 – 3.91 (m, 1H), 3.85 (t, J = 5.3 Hz, 2H), 3.35 – 3.28 (m, 1H), 3.25 (s, 3H), 3.06 – 2.99 (m, 2H), 2.79 – 2.71 (m, 5H), 2.57 – 2.44 (m, 2H), 2.33 (s, 3H), 1.81 – 1.47 (m, 4H), 1.27 (s, 9H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, CD3COCD3) δ 201.6, 153.3, 146.6, 145.1, 133.0, 130.0, 129.3, 128.7, 128.2, 128.1, 127.9, 127.8, 126.5, 125.9, 125.8, 117.1, 95.4, 80.6, 73.6, 67.7, 64.9, 61.6, 54.8, 49.8, 48.6, 45.8, 44.7, 35.0, 27.4, 20.6. HRMS (ESI) Calcd for C38H49N2O8S [M+H]+ 693.3204, found: 693.3225.

Tert-butyl (2-fluoroethyl)(4-(1-(3-(methoxymethoxy)-1,2,3,4-tetrahydronaphthalen-2-yl)piperidine-4-carbonyl)phenyl)carbamate (±)-20

To a suspension of NaH (2.4 mg, 0.1 mmol) in anhydrous DMF (1 mL) was added a solution of (±)-19 (20 mg, 0.04 mmol) in DMF (0.5 mL) at 0 °C. The solution was stirred at 0 °C for 10 min and then was added dropwise to a solution of 2-fluoroethyl tosylate (17 mg, 0.08 mmol) in DMF (0.5 mL) at 60 °C. The reaction mixture was stirred at 60 °C for 3 h. Water was added to quench the reaction and the mixture was extracted with EtOAc. The combined organic phase was washed with water, saturated aqueous sodium chloride solution, and dried over anhydrous Na2SO4. The combined organic phase was concentrated in vacuo and the residue was subjected to silica gel chromatography (hexane/EtOAc/Et3N = 2/1/2%, v/v/v) to give the target compound (±)-20 as a light yellow gel (13 mg, 59% yield). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.84 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H), 7.29 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H), 7.07 – 7.01 (m, 4H), 4.74 (dd, J = 16.4, 6.9 Hz, 2H), 4.54 (dt, J = 47.4, 4.9 Hz, 2H), 3.98 (dd, J = 13.2, 7.9 Hz, 1H), 3.87 (dt, J = 24.9, 4.9 Hz, 2H), 3.37 (s, 3H), 3.19 – 3.10 (m, 2H), 3.00 −2.92 (m, 4H), 2.82 – 2.76 (m, 2H), 2.61 – 2.45 (m, 2H), 1.89 – 1.70 (m, 4H), 1.39 (s, 9H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 201.7, 153.9, 146.9, 134.5, 133.4, 128.9, 128.4, 128.2, 126.5, 126.2, 126.0, 125.9, 95.6, 81.7 (d, J = 170.7 Hz), 81.4, 73.6, 64.8, 55.7, 50.6 (d, J = 21.2 Hz), 50.1, 48.0, 44.1, 35.8, 29.2, 28.2. HRMS (ESI) Calcd for C31H42FN2O5 [M+H]+ 541.3072, found: 541.3098.

3.2. In vitro competitive binding assay

VAChT binding affinity studies

Binding affinities of the new compounds were determined by competing them against 5 nM [3H]vesamicol for binding to human VAChT present in synaptic-like microvesicles in postnuclear supernatant prepared from PC12A123.7 cells.35 Nonspecific binding was determined from samples that contained 1 µM of nonradioactive (±)-vesamicol. The test compounds were assayed in increments of 10-fold from 0.1 to 10,000 nM concentration. The surfaces of containers were pre-coated with Sigmacote (Sigma-Aldrich, MO). Samples containing 200 µg postnuclear supernatant in 200 µL of 110 mM potassium tartrate, 20 mM HEPES (pH 7.4 with KOH), 1 mM dithiothreitol and 0.02% sodium azide were incubated at 22 °C for 24 h. A volume of 90 µL was filtered in duplicate through GF/F glass fiber filters coated with polyethylenimine and washed quickly three times with l mL of the same buffer. Filter-bound radioactivity was determined by liquid scintillation spectrometry for 10 min per sample. Averaged data were fitted by regression with a rectangular hyperbola to estimate Ki All compounds were independently assayed at least two times.

Sigma receptors binding affinity studies

The σ receptor binding affinity studies were performed following our previously reported procedure.22 The σ1 receptor binding assays were performed in 96-well plates by incubating test compounds with approximately 300 µg protein of guinea pig brain membrane homogenates and 5 nM (+)-[3H]pentazocine (1.30 GBq/µmol, Perkin Elmer, Boston, MA). Non-specific binding was determined from samples containing 10 µM cold haloperidol. The σ2 receptor binding assays were similarly performed by incubating test compound(s) with rat liver membrane homogenates (~300 µg protein) and ~5 nM [3H]DTG (2.15 GBq/µmol, Perkin Elmer, Boston, MA) in the presence of 1 µM (+)-pentazocine to block σ1 sites. Non-specific binding was determined from samples that contained 10 µM of cold haloperidol. Data from the competitive inhibition experiments were modeled using nonlinear regression analysis to determine the concentration that inhibits 50% of the specific binding of the radioligand (IC50 value). Competitive binding curves were best fit to a one-site fit and gave pseudo-Hill coefficients of 0.6 – 1.0. Ki values were calculated using the method of Cheng and Prusoff 36 and are presented as the mean ± SEM. For these calculations, we used a Kd value of 7.89 nM for (+)-[3H]pentazocine in guinea pig brains and a Kd value of 30.73 nM for [3H]ditolylguanidine in rat livers.

3.3. Radiochemistry

The radiosynthesis of 2-[18F]fluoroethyl tosylate was accomplished according to our published procedure.20, 21, 24 To the dried the solution of 2-[18F]fluoroethyl tosylate (2.6 – 3.0 GBq) was added (−)-18 (2 – 4 mg) in anhydrous DMF (200 µL), then a suspension of 95% sodium hydride in anhydrous DMF (4 – 5 equivalent, 100 µL) was added in one portion. The vessel was capped, vortexed, and then heated at 85 °C for 15 min. Subsequently, 6 M aqueous hydrochloric acid (100 µL) solution was added to the reaction mixture and the reaction was heated at 100 °C for 6 min. Upon cooling to room temperature, the mixture was diluted with 2.8 mL solution consisting of 2.5 mL HPLC mobile phase (acetonitrile in 0.1 M ammonium formate buffer, 3/7, v/v, pH 4.5) and 0.3 mL of 6 M aqueous sodium hydroxide solution. The solution was loaded onto a semi-preparative HPLC system for purification. The HPLC system contains a 5 mL injection loop, an Agilent SB-C18 column (250 × 4.6 mm, 5 µ), a UV detector at 254 nm, and a radioactivity detector. With acetonitrile/0.1 M ammonium formate buffer (30/70, v/v, pH 4.5) as eluent and at a flow rate of 4 mL/min, the retention time of the product was 25 – 27 min. The product collection was diluted using sterile water (~ 50 mL) and then passed through a C18 Sep-Pak Plus cartridge. The trapped product was eluted using ethanol (0.6 mL), followed by 0.9% saline (5.4 mL). After sterile filtration into a glass vial, (−)-[18F]7 was ready for quality control (QC) analysis and animal studies. To check the quality of the (−)-[18F]7, an aliquot of sample was co-injected with nonradiolabeled standard (−)-7 sample solution onto an analytical HPLC system equipped with an Agilent Zorbax SB-C18 column (250 × 4.6 mm, 5 µ) and UV absorbance at 254 nm; the mobile phase consisted of acetonitrile/0.1 M ammonium formate buffer (54/46, v/v, pH 4.5). Under these conditions, the retention time of (−)-[18F]7 was 5.5 min at a flow rate of 1.0 mL/min. The radiochemical purity was > 98%, the radiochemical yield for the three-step labeling was 11 ± 2% (decay corrected to the end of synthesis) and the specific activity was 37 – 148 GBq/µmol (decay corrected to the end of synthesis). The synthesis of (−)-[18F]7 took about 150 min including [18F]fluorine drying step.

3.4. MicroPET studies in NHP and image analysis

All the experiments conducted in NHP were in compliance with the Guidelines for the Care and Use of Research Animals under protocols approved by Washington University School of Medicine Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC). NHP scans and image analysis were conducted according to our published methods. 15, 20, 34, 37–39 Two PET studies were performed on an adult male cynomolgus monkey (7.3 kg) with a microPET Focus 220 scanner (Concorde/CTI/Siemens Microsystems, Knoxville, TN). The animal was fasted for 12 h prior to each PET study and a 2 h dynamic emission scan was acquired after administration of 145 – 190 MBq of (−)-[18F]7 via the venous catheter. PET scans were collected from 0 to 120 min with the following time frames: 3 × 1 min, 4 × 2 min, 3 × 3 min and 20 × 5 min. PET image reconstructed resolution was < 2.0 mm full width half maximum for all 3 dimensions at the center of the field of view. Emission data were corrected using individual attenuation, scatter and random correction and reconstructed using filtered back projection. For quantitative analyses, three-dimensional ROIs (cerebellum, frontal cortex, occipital cortex, striatum, temporal cortex, white matter, hippocampus, and thalamus) were transformed to the baseline PET space and then overlaid on all reconstructed PET images to obtain tissue time–activity curves. Activity measures were standardized to body weight and dose of radioactivity injected to yield standardized uptake value (SUV).

4. Conclusions

Six enantiomeric VAChT compounds containing either fluoroethoxy or fluoroethylamino moiety were synthesized and successfully resolved using a Chiralcel OD column. The in vitro competitive binding assay showed that one of the enantiomers, (−)-7, had potency for VAChT (Ki-VAChT = 0.31 nM) and very good selectivity towards σ1 and σ2 receptors (Ki-σ1 = 1869 nM, Ki-σ2 = 5482 nM). The radiosynthesis of (−)-[18F]7 was explored using three radiolabeling strategies and it was found that a stepwise two-pot three-step radiolabeling strategy is the best approach to the synthesis of (−)-[18F]7 which was accomplished with 11 ± 2% yield, high chemical and radiochemical purity. Initially microPET study demonstrated that (−)-[18F]7 displayed high accumulation in the VAChT-enriched striatum, with rapid washout kinetics from the reference cerebellar region. The promising PET imaging results prompted us to further characterize this tracer in NHPs for its potential suitability as a VAChT PET tracer for clinical use.

Supplementary Material

Highlight.

A high potent and selective enantiomer for VAChT was identified and F-18 radiolabeling with three methods were explored. PET studies in nonhuman primate indicate (−)-[18F]7 is a promising radiotracer for imaging VAChT in vivo.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by United States NIH Grants NS061025, NS075527 and MH092797. The authors thank Robert Dennett of Washington University Cyclotron Facilities for [18F]fluoride production. Optical rotation was determined in the laboratory of Dr. Douglas F. Covey in the Department of Molecular Biology and Pharmacology of Washington University. The authors thank John Hood, Emily Williams, and Darryl Craig for their assistance with the nonhuman primate microPET studies. The authors acknowledge NMR core facility of Washington University St. Louis for research assistance.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Associated content

1H NMR and 13C NMR spectra for new compounds are available free of charge via the internet at http://pubs.rsc.org.

References and notes

- 1.Higley MJ, Picciotto MR. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2014;29:88–95. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2014.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kilbourn MR. J. Labelled Comp. Radiopharm. 2013;56:167–171. doi: 10.1002/jlcr.2998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arvidsson U, Riedl M, Elde R, Meister B. J. Comp. Neurol. 1997;378:454–467. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eiden LE. J. Neurochem. 1998;70:2227–2240. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1998.70062227.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schliebs R, Arendt T. J. Neural. Transm. 2006;113:1625–1644. doi: 10.1007/s00702-006-0579-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hilker R, Thomas AV, Klein JC, Weisenbach S, Kalbe E, Burghaus L, Jacobs AH, Herholz K, Heiss WD. Neurology. 2005;65:1716–1722. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000191154.78131.f6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kuhl DE, Minoshima S, Fessler JA, Frey KA, Foster NL, Ficaro EP, Wieland DM, Koeppe RA. Ann. Neurol. 1996;40:399–410. doi: 10.1002/ana.410400309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Efange SM, Garland EM, Staley JK, Khare AB, Mash DC. Neurobiol. Aging. 1997;18:407–413. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(97)00038-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Prado VF, Martins-Silva C, de Castro BM, Lima RF, Barros DM, Amaral E, Ramsey AJ, Sotnikova TD, Ramirez MR, Kim HG, Rossato JI, Koenen J, Quan H, Cota VR, Moraes MF, Gomez MV, Guatimosim C, Wetsel WC, Kushmerick C, Pereira GS, Gainetdinov RR, Izquierdo I, Caron MG, Prado MA. Neuron. 2006;51:601–612. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Giboureau N, Som IM, Boucher-Arnold A, Guilloteau D, Kassiou M. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2010;10:1569–1583. doi: 10.2174/156802610793176846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Efange SM. FASEB J. 2000;14:2401–2413. doi: 10.1096/fj.00-0204rev. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Efange SM, Mach RH, Smith CR, Khare AB, Foulon C, Akella SK, Childers SR, Parsons SM. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1995;49:791–797. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(94)00541-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kuhl DE, Koeppe RA, Fessler JA, Minoshima S, Ackermann RJ, Carey JE, Gildersleeve DL, Frey KA, Wieland DM. J. Nucl. Med. 1994;35:405–410. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Petrou M, Frey KA, Kilbourn MR, Scott PJ, Raffel DM, Bohnen NI, Muller ML, Albin RL, Koeppe RA. J. Nucl. Med. 2014;55:396–404. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.113.124792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tu Z, Efange SM, Xu J, Li S, Jones LA, Parsons SM, Mach RH. J. Med. Chem. 2009;52:1358–1369. doi: 10.1021/jm8012344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Efange SM, Khare AB, von Hohenberg K, Mach RH, Parsons SM, Tu Z. J. Med. Chem. 2010;53:2825–2835. doi: 10.1021/jm9017916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tu Z, Wang W, Cui J, Zhang X, Lu X, Xu J, Parsons SM. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2012;20:4422–4429. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2012.05.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Padakanti PK, Zhang X, Jin H, Cui J, Wang R, Li J, Flores HP, Parsons SM, Perlmutter JS, Tu Z. Mol. Imaging Biol. 2014;16:773–780. doi: 10.1007/s11307-014-0749-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu H, Jin H, Li J, Zhang X, Kaneshige K, Parsons SM, Perlmutter JS, Tu Z. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2015;752:18–25. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2015.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tu Z, Zhang X, Jin H, Yue X, Padakanti PK, Yu L, Liu H, Flores HP, Kaneshige K, Parsons SM, Perlmutter JS. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2015;23:4699–4709. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2015.05.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yue X, Bognar C, Zhang X, Gaehle G, Moerlein SM, Perlmutter JS, Tu Z. Appl. Radiat. Isot. 2016;107:40–46. doi: 10.1016/j.apradiso.2015.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Padakanti PK, Zhang X, Li J, Parsons SM, Perlmutter JS, Tu Z. Mol. Imaging Biol. 2014;16:765–772. doi: 10.1007/s11307-014-0748-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li J, Zhang X, Zhang Z, Padakanti PK, Jin H, Cui J, Li A, Zeng D, Rath NP, Flores H, Perlmutter JS, Parsons SM, Tu Z. J. Med. Chem. 2013;56:6216–6233. doi: 10.1021/jm400664x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Karimi M, Tu Z, Yue X, Zhang X, Jin H, Perlmutter JS, Laforest R. EJNMMI Res. 2015;5:73. doi: 10.1186/s13550-015-0149-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hocke C, Prante O, Salama I, Hubner H, Lober S, Kuwert T, Gmeiner P. ChemMedChem. 2008;3:788–793. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.200700327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kniess T, Laube M, Brust P, Steinbach J. MedChemComm. 2015;6:1714–1754. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Padakanti P, Yu L, Fan J, Li S, Li A, Mach R, Parsons S, Permutters J, Tu Z. J Nucl. Med. 2012;53(S1):402. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Crouzel C, Venet M, Irie T, Sanz G, Boullais C. J. Labelled Comp. Radiopharm. 1988;25:403–414. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Efange SM, Michelson RH, Dutta AK, Parsons SM. J. Med. Chem. 1991;34:2638–2643. doi: 10.1021/jm00112a044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang W, Cui J, Lu X, Padakanti PK, Xu J, Parsons SM, Luedtke RR, Rath NP, Tu Z. J. Med. Chem. 2011;54:5362–5372. doi: 10.1021/jm200203f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Berndt U, Stanetty C, Wanek T, Kuntner C, Stanek J, Berger M, Bauer M, Henriksen G, Wester H-J, Kvaternik H, Angelberger P, Noe C. J. Labelled Comp. Radiopharm. 2008;51:137–145. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cherry SR, Gambhir SS. ILAR J. 2001;42:219–232. doi: 10.1093/ilar.42.3.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tu Z, Xu J, Jones LA, Li S, Dumstorff C, Vangveravong S, Chen DL, Wheeler KT, Welch MJ, Mach RH. J. Med. Chem. 2007;50:3194–3204. doi: 10.1021/jm0614883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jin H, Zhang X, Yue X, Liu H, Li J, Yang H, Flores H, Su Y, Parsons SM, Perlmutter JS, Tu Z. Nucl. Med. Biol. 2016;43:131–139. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2015.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zea-Ponce Y, Mavel S, Assaad T, Kruse SE, Parsons SM, Emond P, Chalon S, Giboureau N, Kassiou M, Guilloteau D. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2005;13:745–753. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2004.10.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cheng Y, Prusoff WH. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1973;22:3099–3108. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(73)90196-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li J, Zhang X, Jin H, Fan J, Flores H, Perlmutter JS, Tu Z. J. Med. Chem. 2015;58:8584–8600. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b01205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu H, Jin H, Yue X, Zhang X, Yang H, Li J, Flores H, Su Y, Perlmutter JS, Tu Z. NeuroImage. 2015;121:253–262. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2015.07.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fan J, Zhang X, Li J, Jin H, Padakanti PK, Jones LA, Flores HP, Su Y, Perlmutter JS, Tu Z. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2014;22:2648–2654. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2014.03.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.