Abstract

Background

Accurately estimating cardiovascular risk is fundamental to good decision-making in cardiovascular disease (CVD) prevention, but risk scores developed in one population often perform poorly in dissimilar populations. We sought to examine whether a large integrated health system can use their electronic health data to better predict individual patients’ risk of developing cardiovascular disease (CVD).

Methods

We created a cohort using all patients ages 45–80 who used Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) ambulatory care services in 2006 with no history of CVD, heart failure, or loop diuretics. Our outcome variable was new-onset CVD in 2007–11. We then developed a series of recalibrated scores, including a fully re-fit “VA Risk Score – CVD (VARS-CVD).” We tested the different scores using standard measures of prediction quality.

Results

For the 1,512,092 patients in the study, the ASCVD risk score had similar discrimination as the VARS-CVD (C-statistic of 0.66 in men and 0.73 in women), but the ASCVD model had poor calibration, predicting 63% more events than observed. Calibration was excellent in the fully recalibrated VARS-CVD tool, but simpler techniques tested proved less reliable.

Conclusions

We found that local electronic health record data can be used to estimate CVD better than an established risk score based on research populations. Recalibration improved estimates dramatically, and the type of recalibration was important. Such tools can also easily be integrated into health system’s electronic health record and can be more readily updated.

Introduction

Knowing a patient’s chance of developing an illness is central to all good medical decision-making since developing personalized treatment strategies requires estimating each patient’s risk of developing that particular disease.1–5 This risk-based principal underlies the 2013 ACC/AHA guidelines for cholesterol-lowering statin drugs,6,7 which recommend using a patient’s estimated CVD risk to guide primary cardiovascular disease (CVD) prevention. Risk has long played a central role in guiding aspirin use8 and blood pressure treatment internationally,9 but these recommendations produced considerable controversy, in part because critics noted that the associated risk score (the Atherosclerotic CVD score, or ASCVD score) had inconsistent results in some populations.10

The inconsistency between populations is not surprising. Risk scores often are inconsistent between populations and time periods.11,12 One potential solution to this problem in the era of Big Data is to create risk scores using a healthcare system’s own data instead of relying on externally developed scores from actively followed cohort studies. This approach could have several advantages. First, it eliminates the problem of results varying between populations, since the risk score would be calibrated to the population in which it will be used. Second, the tool could be updated whenever the local healthcare system finds it useful, instead of depending on the investigators of a particular cohort study. Third, the tool would use data from actual patients, not the research volunteers used in cohort studies, who can be decidedly non-representative. Finally, the data in cohort studies are gathered in research settings;7 it is unclear how well this data reflects true clinical practice, especially since some variables (like blood pressure and smoking status) are measured less reliably in the usual outpatient setting. Higher-quality data collected in research settings could lead to risk scores with excellent discrimination in the original analyses, but worse in clinical practice.

Creating a risk score using a healthcare system’s observed clinical data, however, also carries substantial risks. The lack of research-quality data could mean that a real-world risk score will predict events poorly. Missing data, for example from patients not receiving lab draws, could also limit the score’s accuracy.

The US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) is the country’s largest integrated healthcare system and has been a leader in using the electronic health record (EHR) for clinical care.13 This paper tests the feasibility of re-creating the ASCVD risk score to the VA population using information available in the VA EHR. While most directly relevant to statin use following the ACC/AHA guidelines, this work is intended to guide care for all of cardiovascular prevention. To do this, we developed three models of increasing data and analytic requirements for adapting the ASCVD tool to the VA population: Population Recalibrated, Regression Recalibrated, and the VA Risk Score-CVD (VARS-CVD). The Population Recalibrated model adjusts for differences between the study cohort and the target population using population-level demographic information. This data would likely be easily available to health system leaders. The Regression Recalibrated method re-scales individual-level ASCVD scores. The VARS-CVD model is fully refitted for all the ASCVD model predictors.14

We compared the three models using common measures of calibration and discrimination. Calibration assesses how closely the predicted risk probabilities reflect true risk by comparing predicted outcomes to observed ones. Discrimination measures the ability of a risk prediction tool to distinguish between those who will and will not have an event during the follow-up period. Both could be impacted by using clinical EHR data. We hypothesized that re-creating the scores with EHR data would improve calibration without dramatically harming clinical discrimination. This approach could provide a model for how other health systems can create risk scores that are evidence-based, practical for applied use, and calibrated to their own patients in many conditions using EHR data.

Methods

Data sources

We used national data from the outpatient, inpatient, labchem, pharmacy, vital signs, and health factors datasets from the VA; Medicare inpatient, MedPAR, carrier, and outpatient data files from CMS; and data from the National Death Index (Supplemental Table 1).

Population

We identified all VA patients aged 45–80 who had no documented history of CVD or clinical heart failure, who had at least two outpatient visits to specific ambulatory care clinics during 2006 (Supplemental Table 2), and who were alive at the start of follow-up of January 1, 2007. We excluded patients on loop diuretics because of concern for undocumented CHF. We excluded patients who died from a non-CVD cause of death during 2007, since this likely represents pre-existing serious illness that would make primary prevention inappropriate. We did not exclude people who were on statins because we intend this risk score to have broader use than just statin decisions.

We randomly selected two-thirds of the dataset to serve as a derivation cohort for model building and used the remaining third for validation. All reported results for prediction quality are from the validation cohort.

Risk predictors

Our analyses focused on the variables in the ASCVD risk model (Supplemental Tables 3–6). These variables have strong theoretical and empirical evidence supporting their use, are available to practicing clinicians in the EHR, and allow for direct comparison with the ASCVD score. For laboratory and vital signs measures we used the average of the last two values from 2004 through 2006 (Supplemental Table 3); for past medical history and diagnoses we used data from 2001–2006; for patient demographics (date of birth, race, and sex) we used any recorded value from 2001 through 2011; and to assess medication use we used prescription fill data from 2006. We excluded biologically implausible measurements (Supplemental Table 3). Missing values were imputed 20 times and replaced with the mean of the imputed values. Analyses showed that imputation did not substantially alter our findings (Supplemental Tables 13–15 for details).

Outcome variables

Our outcome was “hard” CVD events during the five year follow-up period from 1/1/2007 to 12/31/2011. Hard CVD events included the first occurrence of nonfatal myocardial infarction, CHD death, fatal or nonfatal stroke, based on the 2013 ACC/AHA cholesterol guideline (Supplemental Table 6).6 We used ICD9 diagnosis codes from inpatient admissions to define nonfatal events, including AMI15 and stroke.16,17 Fatal CV events were defined using ICD10 codes from NDI data (I00–I99). We also examined a shorter period using 3-years of follow-up data (2007–2009) in sensitivity analyses, which did not improve model prediction.

Prediction models

First, we computed the risk score reported by the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association’s (ASCVD) Score, which is derived from pooled cohort data and is the basis of current statin guidelines for primary CVD prevention. 6,7 The ASCVD score was originally created from a pooled sample of 5 large NIH-funded cohorts - the Framingham Study, the Framingham Offspring Study, Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities, Cardiovascular Health Study, and Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults.7 The standard ASCVD Risk Equation is as follows:

Where IndX′B is the sum of the individual patient’s covariate values multiplied by the coefficients from the ASCVD equation and MeanX′β is the race and sex specific overall mean “coefficient X value” sum. Thus, the estimated 5-year risk of a first event is calculated by 1 minus the survival rate at 5-years, raised to the power of the exponent of IndX′β minus MeanX′β. The published ASCVD score uses 10 years of follow-up. We computed 5-year ASCVD risk scores using the published regression coefficients, but with the intercept coefficient (beta-zero) based on 5 years of follow-up events obtained directly from the tool developers.

Next, we considered three different methods for recalibrating the ASCVD model for the VA patient population. The Population Recalibrated method mimics a situation in which population averages are available but individual patient-level data is not, for example when using technical reports instead of individual data. We first computed the 5-year VARS survival rate within each sex/race group for our cohort. Then we calculated the MeanX′β for each sex/race group in VARS using our population level averages using the functional form and the estimated hazard ratios from the published ASCVD risk equations.

Where S5 is the VARS 5-year survival rate (“population specific”), IndX′β reflects the average patient covariate values multiplied by the ASCVD coefficients, and MeanX′β is the average CV risk hazard within the VARS population.

The Regression Recalibrated technique was designed as a simple method for recalibration that assumes the basic relationships between specific variables and risk is stable, but overall risk varies between populations. This technique keeps the basic risk factor coefficients unchanged, possibly improving comparability and limiting overfitting. It is also consistent with a model for risk prediction that assumes the effect of these risk factors is biologically causal and hence relatively stable between populations. We used the ASCVD 5-year score as a predictor in a logistic regression model to create the regression recalibrated risk score.

Where β0 and β1 are estimated in our sample and X is the ASCVD score calculated using the ASCVD coefficients, 5-year survival rate, and values for MeanX′β (citation). The model was fit separately for men and women in the derivation cohort. The resulting regression intercepts and slopes were used to create transformations of the ASCVD scores for patients.

Finally, we created a fully refitted model that re-estimated the effect size of each of the ASCVD variables. This was the pre-specified “VA Risk Score for Cardiovascular Disease (VARS-CVD)” model. This model used sex-specific 5-year CVD logistic regression risk equations fit on the derivation portion of our dataset.

Where β0 and β = (β1,…,βp) are estimated in our sample and x = (x1,…,xp) are the observed covariates. The covariates included in the model mirror the established traditional risk factors included in the ASCVD: age, smoking status, non-HDL cholesterol, race (black/non-black), diabetes and systolic blood pressure. We included main effects and age interactions for all covariates in both the male and female VARS-CVD models.

In all three recalibrated models, we created separate models for men and women, and included a main effect term for African-American in both the male and female regression models. In comparison, the ASCVD score created four models for gender and race. We were limited by having relatively few African-American women in our dataset. We also do not know precisely which interactions were tested for the ASCVD score, so we could not mirror them. We did not create separate models for other terms because this has not been done historically in most risk scores and because the effects of the individual variables on prediction (historically or in our model) did not seem large enough to make it appropriate.

For all 3 recalibrated models, to generalize our 5-year results to other published results using 10-year risk scores, we estimated 10-year risk based on our 5-year risk score using the following calculation:

Analysis

For each risk score we report the C-statistic, the Hosmer-Lemeshow Goodness of Fit statistic (GoF), and the Brier score to quantify discrimination (ability of a risk prediction equation to distinguish between those who do and do not have an event during the follow-up period) and calibration (how closely the predicted probabilities reflect true risk) within the validation cohort. We calculated cut-points of our 5-year risk score to differentiate low, medium, and high-risk. We defined low-risk as less than the 10-year ASCVD score cutoff of 7.5%, which guides the current cholesterol guidelines.6 We defined high risk as greater than the commonly-used cut-point of 20% 10-year risk.18,19 We then categorized samples for each risk score into low (10-year CVD risk of under 7.5%), medium (about a 7.5%–20%) or high (>20%) risk. We then found analogous 5-year cut-points that resulted in the same percent of patients in each risk group. The resulting 5-year cutpoints were <3% (low risk), 3% – 9% (medium risk), and >9% (high risk).

In sensitivity analyses described in Supplement 4, we examined the potential impact of uncaptured events where a patient has a non-fatal cardiovascular event at a non-VA facility that is paid for by non-VA sources. We also looked at a variety of prespecified subgroups.

The study was approved by the IRB of the VA Ann Arbor Healthcare System with a waiver of informed consent.

Results

Description of variables examined

Table 1 summarizes patient baseline characteristics. Compared to the pooled cohort sample of 5 large NIH-funded cohorts used to create the ASCVD score and other commonly used risk scores, the VA Risk Score (VARS) cohort is much larger, older, predominantly male, has higher diabetes prevalence and is on more medicines for blood pressure and cholesterol (also see Supplemental Table 7). 7 There were no differences between the derivation and validation cohorts.

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics for Baseline Measures

| Total | Men | Women | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No of Patients | 1,512,092 | 1,435,937 | 76,155 |

| Age, mean ± SD, years | 61.7 ± 8.6 | 62.0 ± 8.6 | 55.6 ± 7.4 |

| Male, No. (%) | 1,435,937 (95.0) | 1,435,937 (100) | 0 (0) |

| Current Smoker, No. (%) | 397,047 (26.3) | 377,755 (26.3) | 19,292 (25.3) |

| SBP, mean ± SD, mmHg | 135.4 ± 15.1 | 135.6 ± 15.1 | 131.1 ± 15.6 |

| Total Cholesterol/HDL ratio, mean ± SD, mg/dL | 4.4 ± 1.4 | 4.4 ± 1.4 | 4.0 ± 1.3 |

| Total Cholesterol, mean ± SD, mg/dL | 184.7 ± 35.0 | 183.8 ± 34.8 | 201.7 ± 35.3 |

| HDL Cholesterol, mean ± SD, mg/dL | 45.1 ± 13.24 | 44.6 ± 12.95 | 54.55 ± 14.93 |

| NonHDL, mean ± SD, mg/dL | 139.6 ± 34.4 | 139.2 ± 34.3 | 147.12 ± 35.5 |

| Type 2 Diabetes, No. (%) | 367,793 (24.3) | 355,857 (24.8) | 11,936 (15.7) |

| Treated Hypertension, No. (%) | 809,424 (53.5) | 779,618 (54.3) | 29,806 (39.1) |

| Statin Use, No. (%) | 562,619 (37.2) | 541,082 (37.7) | 21,537 (28.3) |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| White | 1,073,446 (71.0) | 1,030,367 (71.8) | 43,079 (56.6) |

| Black | 216,492 (14.3) | 204,196 (14.2) | 12,296 (16.2) |

| Other | 221,315 (14.6) | 200,584 (14.0) | 20,731 (27.2) |

The exclusions are described in detail in Supplemental Table 8. The most common exclusions were due to patient age or history of any cardiovascular disease. Descriptions of the outcomes are in Supplemental Table 9.

Assessment of prediction models

Overall, discrimination was similar across the models within each sex, but their calibration to the VA population varied dramatically (Table 2). The models had greater C-statistics (area under the ROC curve, a measure of discrimination) in women than in men. Within each sex, the ASCVD score had the lowest C-statistic and the VARS-CVD the largest, although the difference was small. The Population and Regression Recalibrated methods resulted in C-statistics identical to the ASCVD score in men. In women, the Regression Recalibrated had the same C-statistic as the ASCVD score, but the Population Recalibrated method had a very slight improvement. The model parameters for the VARS-CVD model are in Supplemental Table 10.

Table 2.

Discrimination and calibration of models in validation cohort

| Men | C-statistic | Brier score | Goodness of Fit Statistic | Average predicted event rate(5-yr) | Average predicted event rate(10-yr) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ASCVD | 0.657 | 0.055 | 8318 | 0.091 | 0.196 |

| Population Recalibrated | 0.657 | 0.053 | 2820 | 0.073 | 0.136 |

| Regression Recalibrated | 0.657 | 0.053 | 1046 | 0.056 | 0.108 |

| VARS-CVD | 0.664 | 0.052 | 17.4 | 0.056 | 0.108 |

| Women | |||||

| ASCVD | 0.726 | 0.019 | 49.0 | 0.023 | 0.064 |

| Population Recalibrated | 0.727 | 0.020 | 199 | 0.035 | 0.066 |

| Regression Recalibrated | 0.726 | 0.019 | 79.2 | 0.022 | 0.043 |

| VARS-CVD | 0.728 | 0.019 | 23.2 | 0.021 | 0.043 |

Note. C-Statistic, Brier Score, and Goodness of Fit statistic are based on the 5-year risk model. We estimated the Average Predicted event rate (10-yr) using the following: Pr(CV Event in 10 yrs | age) = Pr (CV event in 5 yrs | age) + [(1 − Pr (CV event in 5 yrs | age)) * Pr (CV event in 5 yrs | age + 5)]

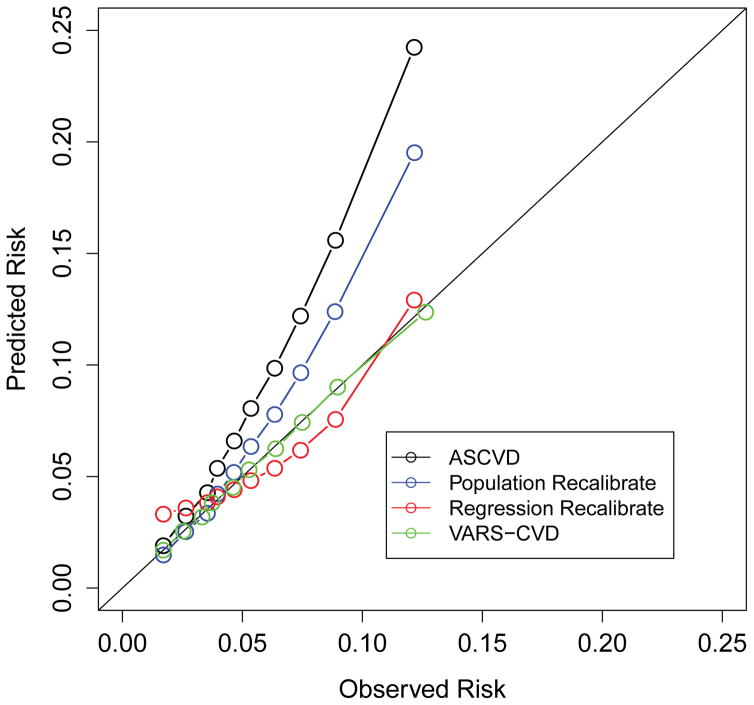

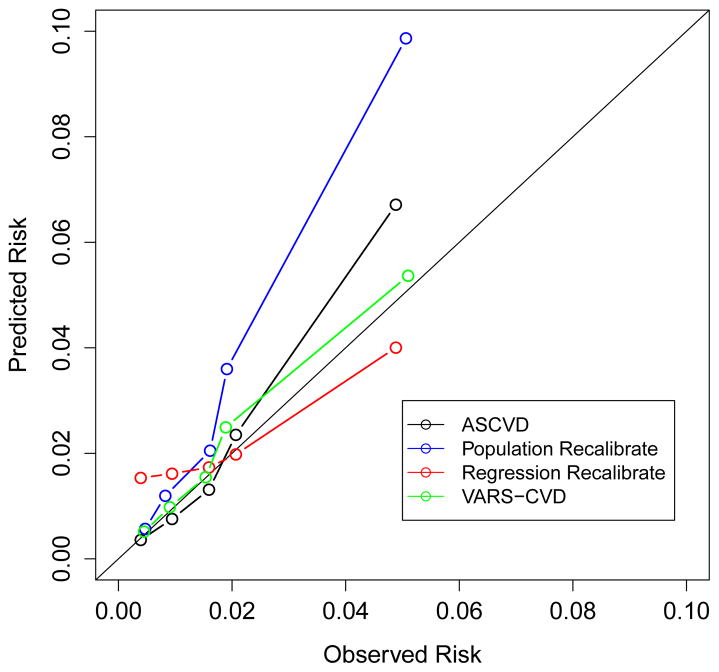

The improvement in calibration between predicted risk probabilities and the recalibrated tools was more dramatic (Table 2). The standard ASCVD score substantially over-estimated CVD events with an average predicted event rate of 0.091 events vs. 0.056 observed events, per 5 years (Table 2). Most of this over-estimation was in those with higher observed risk (Figure 1). This was especially true in the population recalibrated system.

Figure 1.

Predicted and observed CVD event rates for the ASCVD score and three re-calibrated scores. Each dot represents a decile of risk in men and a quintile of risk in women, reflecting the smaller number of women in the study. Figure 1a is in men, figure 1b is in women.

The results for the women were less dramatic. The ASCVD score only slightly overestimated event rates (0.023 average predicted events vs. 0.021 observed, per 5 years, GoF 49.0). The Population Recalibrated had a minimal effect on the discrimination and made calibration substantially worse, especially at the higher values (Table 2 and Figure 1). (Note that the GoF statistic cannot be directly compared between the models for men and women due to differences in sample size.) Results were very similar in multiple subgroups (Supplemental Table 11).

Risk Reclassification

The clinical implications of improved calibration are seen in the dramatic effect on patient risk reclassification (Table 3 and Supplemental Table 12). Of the 189,491 participants classified as high CVD risk (5-year risk >9%, estimated 10-year CVD risk > 20%) by the ASCVD score, 62.6% were reclassified down to medium risk (5-year risk between 3% and 9%, estimated 10-year CVD risk between 7.5% and 20%) by VARS-CVD; of the 233,450 classified as medium risk by ASCVD, 19.9% were reclassified as low risk (5-year risk < 3%, estimated 10-year CVD risk < 7.5%) and 0.2% to high risk by VARS-CVD; and of the 81,090 participants classified as low CVD risk by the ASCVD tool, 3.6% were reclassified as medium risk (by VARS-CVD (Table 3). The reclassification of patients from high to medium risk was similar when comparing the original ASCVD score to the other scores; reclassification between the VARS-CVD, Population Recalibrated, and Regression Recalibrated scores was less common (Table 3 and Supplemental Table 12).

Table 3.

Reclassification using common treatment cut-points.* Each cell represents the predicted risk group for each study participant by the different prediction techniques.

| ASCVD | Regression Recalibrated | VARS-CVD | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Low | Medium | High | Low | Medium | High | Total | |

| Low (≤3%) | 19,750 (24.4%) | 61,340 (75.6%) | 0 (0.0%) | 78,195 (96.4%) | 2,895 (3.6%) | 0 (0.0%) | 81,090 |

| Medium (3–9%) | 3,277 (1.4%) | 230,173 (98.6%) | 0 (0.0%) | 46,494 (19.9%) | 186,414 (79.9%) | 542 (0.2%) | 233,450 |

| High (>9%) | 0 (0.0%) | 145,451 (76.8%) | 44,030 (23.2%) | 14 (0.01%) | 118,538 (62.6%) | 70,939 (37.4%) | 189,491 |

Cut-points use 5-year cut-points of 3% and 9% 5-year risk, which closely approximate the 7.5% and 20% cut-points seen in current guidelines.

Of the 422,941 people who would be recommended statin use by the ASCVD criteria, 46,508 (11.0%) actually have a less than 7.5% chance of having a heart attack or stroke in 10 years and should not be recommended to start a statin.

The locally-developed risk scores predicted lower event rates for almost all participants than the ASCVD score. This included reclassifying almost 20 times more people to lower risk groups than higher risk groups (Table 3, Supplemental Table 13, and Supplemental Figure 1). These findings were particularly striking among individuals with ASCVD predicted risk scores >9% (Supplemental Figure 1).

Missing and Misclassified Data

Missing data, imputation, and misclassified results, including from uncaptured cardiovascular events, had small effects on the models. Full details of this evaluation are in Supplemental Tables 13–16 and Supplemental Figures 1 and 2.

Discussion

We found that a large managed care organization can use their own electronic health records and administrative outcome data to create a cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk prediction score with substantial advantages over those developed in traditional cohort studies. The VARS-CVD score is much better calibrated than the externally-developed ASCVD score.7,12 The ASCVD score, developed from data pooled from 5 cohort studies, had similar statistical discrimination to our internally-developed VA Risk Score for Cardiovascular Disease (VARS-CVD), but systematically over-estimated the observed risk in our cohort by almost 60%.20

Our findings have substantial implications for risk-based prevention of CVD. CVD risk prediction is central to the 2013 ACC/AHA Clinical Practice Guidelines on the Treatment of Blood Cholesterol. These guidelines remain controversial, in part due to observed over-prediction when the ASCVD score was examined in some study populations. 20 However, it is well-established that risk scores developed in one population often mis-predict in other populations since people always have risk factors that are not easily measured.12 For example, exercise and life stress are established risk factors, but are vexingly difficult to measure. 21

Unfortunately, current clinical research continues to look for a single, “correct” risk score22,23 and clinical practice uses only one risk score.6,22 This study demonstrates how the cholesterol guidelines, and other risk-based guidelines, could instead be easier to use and more accurate if we create many local risk scores. Our results indicate that instead of accepting calibration error or ignoring overall risk altogether we should use locally recalibrated or newly developed risk scores created from EHRs. Further, the real-world data has strengths that may at first seem like weaknesses. For example, large cohort studies usually measure blood pressure averaging multiple measures following careful protocols.7 In contrast, an internally developed risk score uses the risk factor how it’s measured in practice.

EHR-based risk prediction scores like VARS-CVD have other advantages over cohort-derived scores. An organization’s risk profile can change from population-wide trends and changing demographics. Since we used information that is easily available (Table 4), organizations can develop and update risk scores independently. These results can be integrated into local decision support tools based on their needs. EHR-based scores can also have much larger populations. While our patient population was 95% men, there were still 6 times more women in our sample as in the ASCVD score development population. Further, advances in wearable technology, genetics and electronic health records could soon provide dramatic advances in risk prediction unavailable in existing cohorts. 24,25

Table 4.

Comparison of a health system-specific risk score to traditional scores

| Features | Current Scores | Advantage of health system-based score |

|---|---|---|

| Calibration | Often poor | Good |

| Discrimination | Decent | Decent |

| External validity | Varies | Not needed |

| Ease of use | Often difficult | Automated into workflow |

| Population relevance | Debatable | Ideal |

| Ease of updating | Difficult, out of organizational control | Moderate, based on organizational data |

| Ease of improvement | Follows large cohort development | Follows new data in EHR |

| Age restrictions | Commonly used | Per local decisions |

| Comorbidity restrictions | Often necessary due to sample size | Less common risk factors can be included |

We used three different recalibration techniques, each designed to approximate a different real-world situation. The first, Population Recalibrated, is meant to resemble how health-system managers, with easy access to population-level descriptive information about their patients could roughly approximate their patient’s risk. The second, Regression Recalibrated, used a simple logistic regression between the results of the ASCVD score and the observed outcome in our database. This keeps the basic risk ratios unchanged, potentially improving comparability and limiting overfitting. While better than using the ASCVD score, these models had poor calibration. Finally, in the full recalibration technique (VARS-CVD), we used the individual predictors and recalibrated the entire model. We had wondered whether the simpler recalibration techniques would be “good enough” for organizations, but found that their mis-calibration was quite large.

The strengths of this study – including the use of clinical data – also lead to its weaknesses. Important data was missing for some patients. We think this is partly why our study’s discrimination was not better than previous scores.

Our study used administrative data for identifying outcomes, as opposed to chart review or full adjudication, which will create some estimation errors. 26,27 Although there are advantages to fully adjudicating outcomes, they are also prone to capture minor events that have unclear clinical importance, such as increases in troponin. Further, CVD mortality, especially, is known to be over-estimated in administrative databases. 28 This over-estimation makes our findings less dramatic, since we found fewer events than the ASCVD score would have predicted.

We would have liked to assess other cardiovascular risk scores, such as the Reynolds Scores, but they include variables that were not clinically available in our EHR, such as family history and C-reactive protein. Differences between existing scores are summarized in Supplemental Table 3. Finally, ideally we would have tested our risk score on patients from after the score was completed, rather than the same time period. This was not practical due to data limitations.

While other scores were based on 10 years of follow-up, we developed our score using 5 year follow-up. We did this for three reasons: 1) to minimize the impact of changes in lipid and blood pressure medication that might be made during follow-up of an initial disease-free cohort, 2) we think this is a more reasonable basis for decision-making since decisions should probably be reassessed at least every 3–5 years, and 3) the full 10 years of data is not fully-reliable in our dataset. We cannot find a clinical reason why 10 years became common many years ago.

This work has policy and clinical implications. We have shown that clinical risk scores can be made efficiently within a single EHR. This could be done at many other managed care organizations and for many other clinical conditions. As EHRs improve, scores like the VARS-CVD score can easily be improved and re-calibrated to new populations. As “Big Data” becomes more central to patient self-management, work like this can point the way towards how these tools can be used in clinical practice, preventing CVD events while guiding statin use for patients who are more likely to benefit.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding sources: This work was supported by VA IIR 11-088, VA IIR-15-432, and VA Career Development Award 12-021 (Sussman). Support for VA/CMS data is provided by the Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Office of Research and Development, Health Services Research and Development, VA Information Resource Center (Project Numbers SDR 02-237 and 98-004).

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: None

All of the authors participated in the preparation of the manuscript

References

- 1.Hayward RA, Kent DM, Vijan S, Hofer TP. Reporting clinical trial results to inform providers, payers, and consumers. Health affairs (Project Hope) 2005 Nov-Dec;24(6):1571–1581. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.24.6.1571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hayward RA, Krumholz HM, Zulman DM, Timbie JW, Vijan S. Optimizing statin treatment for primary prevention of coronary artery disease. Ann Intern Med. Jan 19;152(2):69–77. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-152-2-201001190-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sussman J, Vijan S, Hayward R. Using benefit-based tailored treatment to improve the use of antihypertensive medications. Circulation. 2013 Nov 19;128(21):2309–2317. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.002290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sussman JB, Kent DM, Nelson JP, Hayward RA. Improving diabetes prevention with benefit based tailored treatment: risk based reanalysis of Diabetes Prevention Program. BMJ. 2015;350:h454. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sussman JB, Vijan S, Choi H, Hayward RA. Individual and population benefits of daily aspirin therapy: a proposal for personalizing national guidelines. Circulation. Cardiovascular quality and outcomes. 2011 May;4(3):268–275. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.110.959239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stone NJ, Robinson JG, Lichtenstein AH, et al. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the treatment of blood cholesterol to reduce atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2014 Jun 24;129(25 Suppl 2):S1–45. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000437738.63853.7a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goff DC, Jr, Lloyd-Jones DM, Bennett G, et al. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the assessment of cardiovascular risk: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2014 Jun 24;129(25 Suppl 2):S49–73. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000437741.48606.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aspirin for the prevention of cardiovascular disease: U S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009 Mar 17;150(6):396–404. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-6-200903170-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Williams B, Poulter NR, Brown MJ, et al. British Hypertension Society guidelines for hypertension management 2004 (BHS-IV): summary. BMJ. 2004 Mar 13;328(7440):634–640. doi: 10.1136/bmj.328.7440.634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ridker PM, Cook NR. Statins: new American guidelines for prevention of cardiovascular disease. Lancet. 2013 Nov 30;382(9907):1762–1765. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62388-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.D’Agostino RB, Sr, Grundy S, Sullivan LM, Wilson P Group CHDRP. Validation of the Framingham coronary heart disease prediction scores: results of a multiple ethnic groups investigation. JAMA. 2001 Jul 11;286(2):180–187. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.2.180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Siontis GC, Tzoulaki I, Siontis KC, Ioannidis JP. Comparisons of established risk prediction models for cardiovascular disease: systematic review. BMJ. 2012 May 24;344:e3318. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e3318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Render ML, Freyberg RW, Hasselbeck R, et al. Infrastructure for quality transformation: measurement and reporting in veterans administration intensive care units. BMJ quality & safety. 2011 Jun;20(6):498–507. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs.2009.037218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Steyerberg EW. Clinical prediction models : a practical approach to development, validation, and updating. New York, NY: Springer; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Krumholz HM, Merrill AR, Schone EM, et al. Patterns of hospital performance in acute myocardial infarction and heart failure 30-day mortality and readmission. Circulation. Cardiovascular quality and outcomes. 2009 Sep;2(5):407–413. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.109.883256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Niesner K, Murff HJ, Griffin MR, et al. Validation of VA administrative data algorithms for identifying cardiovascular disease hospitalization. Epidemiology. 2013 Mar;24(2):334–335. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3182821e75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Roumie CL, Mitchel E, Gideon PS, Varas-Lorenzo C, Castellsague J, Griffin MR. Validation of ICD-9 codes with a high positive predictive value for incident strokes resulting in hospitalization using Medicaid health data. Pharmacoepidemiology and drug safety. 2008 Jan;17(1):20–26. doi: 10.1002/pds.1518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.National Cholesterol Education Program Expert Panel on Detection E, Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in A. Third Report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) final report. Circulation. 2002 Dec 17;106(25):3143–3421. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Board JBS. Joint British Societies’ consensus recommendations for the prevention of cardiovascular disease (JBS3) Heart. 2014 Apr;100(Suppl 2):ii1–ii67. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2014-305693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ridker PM, Cook NR. Comparing cardiovascular risk prediction scores. Ann Intern Med. 2015 Feb 17;162(4):313–314. doi: 10.7326/M14-2820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee IM, Sesso HD, Paffenbarger RS., Jr Physical activity and coronary heart disease risk in men: does the duration of exercise episodes predict risk? Circulation. 2000 Aug 29;102(9):981–986. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.9.981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cook NR, Ridker PM. Calibration of the Pooled Cohort Equations for Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease: An Update. Ann Intern Med. 2016 Dec 06;165(11):786–794. doi: 10.7326/M16-1739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Damen JA, Hooft L, Schuit E, et al. Prediction models for cardiovascular disease risk in the general population: systematic review. BMJ. 2016 May 16;353:i2416. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yeboah J, McClelland RL, Polonsky TS, et al. Comparison of novel risk markers for improvement in cardiovascular risk assessment in intermediate-risk individuals. JAMA. 2012 Aug 22;308(8):788–795. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.9624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hartley CJ, Naghavi M, Parodi O, Pattichis CS, Poon CC, Zhang YT. Cardiovascular health informatics: risk screening and intervention. IEEE transactions on information technology in biomedicine : a publication of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society. 2012 Sep;16(5):791–794. doi: 10.1109/TITB.2012.2216057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McCormick N, Bhole V, Lacaille D, Avina-Zubieta JA. Validity of Diagnostic Codes for Acute Stroke in Administrative Databases: A Systematic Review. PloS one. 2015;10(8):e0135834. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0135834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McCormick N, Lacaille D, Bhole V, Avina-Zubieta JA. Validity of myocardial infarction diagnoses in administrative databases: a systematic review. PloS one. 2014;9(3):e92286. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0092286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Govindan S, Shapiro L, Langa KM, Iwashyna TJ. Death certificates underestimate infections as proximal causes of death in the U.S. PloS one. 2014;9(5):e97714. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0097714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.