Short abstract

Engaging adolescents with their health can prevent a lifetime of bad habits and should be a priority for an efficient future health service

It is easy to understand why a national sickness service, as the NHS has been described,1 might choose largely to ignore young people. The common perception is that young people are rarely ill. However, in setting out its plans for the NHS, the government is now calling for a shift to a service focusing on the whole of health and wellbeing.2,3 The national service framework for children, young people and maternity provides a lever for local change, but securing the short and longer term gains in population health and reducing health inequality will call for a much keener focus on the health of young people.

Background

Before the government's 2002 spending review, Derek Wanless was asked to consider what would be required to provide high quality health services in 20 years' time. Wanless showed that the least expensive future scenario, and the one that also gave the best health outcomes, was the “fully engaged” scenario: the level of public engagement in relation to health is high and people are confident in the health system and demand high quality health care. The health service is responsive, with high rates of technology uptake, particularly in relation to disease prevention, and resources are used efficiently.1

The potentially “fully engaged” citizens of 20 years' time are today's seven million young people. However, the health of young people seems to have little priority in the United Kingdom. Aside from the teenage pregnancy strategy, few public health initiatives focus on adolescent health. So what might a fully engaged scenario look like for today's young people?

Where are we now?

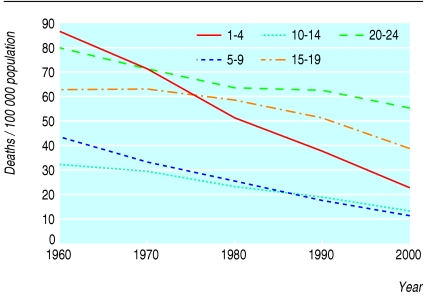

For adolescents (defined by the World Health Organisation as 10-20 years of age), key public health indicators in priority areas such as obesity, smoking, sexually transmitted infections, and teenage pregnancy, have shown adverse trends or no change in the past 20 years (see bmj.com). This is against a background of considerable gains in the health of young children and older people. At the same time, the prevalence of common long term illnesses such as asthma and diabetes has increased, and advances in the treatment of congenital conditions have resulted in new cohorts with diseases largely unknown to adult physicians.4 Mortality in young people has also fallen much less than in children (figure). This reflects increased mortality from injury and suicide, rising from 11% of total deaths among 15-19 year olds in 1901-10 to 57% in 2003.5

The trends in adolescent health are strongly linked with health inequalities. Risk behaviours such as binge drinking, delinquency, and illicit drug use may contribute to the development of health and social inequalities during the transition from adolescence to adulthood.6–8 Health inequalities linked with ethnicity disproportionately affect young people, as the adolescent population is more ethnically diverse than older groups.

Figure 1.

Age specific mortality in England and Wales, 1960-20005

Need for engagement

Adolescence is a critical period for engaging the population in health. New health behaviours are laid down that are maintained into adulthood and influence lifelong health. During adolescence, young people begin to explore “adult” behaviours including smoking, drinking, drug use, violence, and sexual intimacy. The continuities between adolescent health and adult health seem stronger than those between childhood and adulthood (table). The odds ratios and proportion of the variance in adult outcomes (as represented by adjusted R2) explained by adolescent data are both around three times that for childhood.

A prominent theme in recent government policy has been supporting self care for patients with long term conditions.2,3 Self management behaviours in long term illness are also laid down in adolescence. It makes sense to focus “expert patient” initiatives on young people, in whom the payback will be greater over longer periods.

Coexistence of adolescent health problems

Figure 2.

Engaging adolescents in health will produce long term benefits

Credit: JIM VARNEY/SPL

Interventions to improve young people's health have traditionally focused on single issues. However, risk behaviours such as smoking, drinking and drug use as well as sexual risk and violence coexist in high risk young people.9 The Health Survey for England 2002 showed that 11-15 year olds who smoked regularly were more than three times as likely also to drink regularly (P < 0.0001) and six times more likely to have serious psychological distress (P < 0.0001) after sex, age, and social class had been taken into account.10

This clustering reflects the existence of common predisposing and protective factors for health risk behaviours that arise largely out of adolescent developmental processes.11 Interventions based on such common factors seem to be the most effective in combating obesity, smoking, and other problems.12,13

Current health service responsiveness to young people

Use of health services increases from mid-childhood into and through adolescence. Inpatient bed use increases through adolescence, even when obstetric and mental health use is excluded (see bmj.com).14 The escalation of mental health admissions through adolescence is even greater, with admissions minimal in children under 11 years but increasing 14-fold by age 15 years.15 In primary care, just under three quarters of young people attend their general practitioner each year,16 but average consultation times are shorter than for children or adults.17 Few youth specific services exist, yet there is considerable evidence that young people avoid using services not designed for them and that they believe are not respectful or confidential.18

Table 1.

Associations between adult (30 years) health outcomes and risk factors in childhood (10 years) and adolescence (16 years) in the 1970 British birth cohortw1 w2

| Risk factor | Odds ratio (95% CI)† | % of variance in adult outcome explained (adjusted R2) |

|---|---|---|

| Smoking (risk of adult smoking ≥11 cigarettes/day) | ||

| Age 10 years: smokes any cigarettes regularly | 2.0 (1.3 to 3.2)* | 5 |

| Age 16 years: regularly smokes 1 or more cigarettes per week | 7.5 (6.0 to 9.3)*** | 21 |

| Obesity (risk of adult BMI ≥30) | ||

| Childhood obesity (BMI ≥95th centile) | 4.2 (2.8 to 6.2)*** | 8 |

| Adolescent obesity (BMI ≥95th centile) | 11.6 (8.9 to 15.5)*** | 20 |

| Psychological distress (risk of adult distress on malaise inventory) | ||

| Age 10 years: high scorer on Rutter parent scale | 1.5 (1.4 to 1.7)*** | 2 |

| Age 16 years: high scorer on malaise inventory self report | 5.5 (3.3 to 9.2)*** | 8 |

P<0.01, **P<0.001, ***P<0.0001; BMI=body mass index.

All odds ratios are controlled for sex, childhood and adult social class, and maternal educational status. Analyses for obesity are also controlled for height in childhood and adulthood and parental body mass index. Odds ratios for smoking are adjusted for age.

Achieving youth engagement with health

Improving services to allow young people to engage with their health will result in both short term and long term population health gains. Such changes must be part of a broader strategy to reduce inequalities. We suggest the following actions.

Specific public health focus on young people's health

Stop focus on single issue approaches—Public health policy, practice, and research need to develop approaches for young people that focus on common predisposing and protective factors affecting physical and mental health. This must extend beyond health to education, social services, and the justice system.

Develop separate policy for youth—Young people should be recognised as a distinct group in policy formulation and implementation. The effect of policy initiatives on young people's health should be examined specifically.

Reformulate age banding of data—The commonly provided age bandings of 5-15 years and 16-44 years in national data provide no information on trends in adolescent health.

Develop research programmes and networks in adolescent health—Research centres have been effective in translating research based advocacy into service innovations (for example, evidence based school programmes to promote good mental health19 and education programmes for general practitioners based on research into the barriers preventing adolescents from accessing primary health care20). The networks would also have a role in promoting and supporting training.

Refinement of health and health inequality indicators for young people—This would allow local targets to be set for health issues such as obesity and mental health as well as the existing national target to reduce teenage pregnancy.3

Redesign of the Healthy Schools programme—The programme needs to embed health promotion in multiple areas of the curriculum (as has been shown effective in combating obesity21) and facilitate change in the school environment to promote mental health (as has been shown to be effective in reducing risk behaviours19).

Direct engagement of young people through information technology

Introduction of “smart” cards for young people in the United Kingdom is currently under consideration. The smart card should be linked to the introduction of user held health records, which would help engage young people with their health. Cards should also be linked to improved access to age appropriate services (although cards must not be used to limit access), provision of health information, and patient led appointment booking systems.

Provide clinical services that engage young people

Young people need health services that are responsive and sophisticated yet easy to access. Staff must be highly trained in the problems facing young people and culturally competent. Services need to be designed to reduce health inequalities and promote widespread access to information through the use of information technology.1 Providing appropriate services will require improvement of existing services, provision of training across all levels of the health service, and the development of new youth health services where appropriate.

Training—Randomised trials show that the skills needed to communicate effectively with young people can be learnt.20 Skills in adolescent health must be taught to those in training and at postgraduate level in medical, nursing, and allied professions. Brief exposure to adolescent health should be a necessary part of training of groups such as paediatricians, as currently works well in the United States.

Improve the capacity of primary care services to work with young people—Audit and implementation tools should be developed to allow general practices to provide the most important aspects of primary care identified by young people, including confidentiality, respect, privacy, easy confidential access, staff communication skills, age appropriate health promotion, and dedicated young people's clinics with flexible appointment times. Teenagers should be re-registered with practices at 14-15 years to allow them to develop a relationship with their general practitioner outside that of their parents. School health services should be strengthened and extended and explicitly linked with extension of the Healthy Schools programme.

Youth health services—New health services designed for and by young people should be provided in metropolitan areas, particularly those with high levels of deprivation. These services should provide primary care as well as sexual health, drug, and alcohol and counselling services, and should be jointly sited with social services and education provision as “one stop shops”.

Secondary care—Fuller engagement of young people in secondary care can be achieved through the development of specific adolescent clinics, effective management of the transition from paediatric to adult care, and promotion of self management through expert patient programmes. Specific medical inpatient services for young people should also be provided routinely wherever possible.14 Dedicated youth psychiatric services are needed to deal with early onset psychotic illnesses and substance use issues.22

Achieving change

The health service lacks sufficiently trained professionals to service the above developments. The bulk of clinical work will continue to be provided by existing primary and secondary care services, but a small number of professionals in adolescent health will be needed in each region to build capacity through training, research, and development.

Some of the changes, particularly training and identification of national indicators for youth health, are achievable quickly with modest investment. Others, including routine re-registration of young people with general practices and the development and evaluation of models for youth health services, should be urgent priorities for investment.

Summary box

Key public health indicators for young people's health have shown adverse trends or no change in the past 20 years

Adolescence is a critical period for engaging the population in health because new health behaviours are laid down that track into adulthood

Effective interventions require recognition of the coexistence of multiple health problems in young people

Policies that focus on young people's health need to be developed together with services that engage young people with their health

Supplementary Material

Morbidity data and further references are on bmj.com

Morbidity data and further references are on bmj.com

Contributors and sources: RMV is the United Kingdom's only consultant in adolescent medicine and is a member of the intercollegiate adolescent working party of the Academy of Medical Sciences. He currently is completing a research leave fellowship in adolescent health funded by the Health Foundation. MB is a deputy director of public health for London and an honorary senior lecturer in public health at the Institute of Child Health, London. RMV did the analyses for this article from data on the 1970 British Birth Cohort and the Health Survey for England 2002 obtained from the UK Data Archive, University of Essex. RMV also contributed to planning and writing the paper and did the literature review. MB contributed to planning and writing the paper. RMV is the guarantor.

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Wanless D. Securing our future health: taking a long term view. London: Department of Health, 2002.

- 2.Department of Health. NHS improvement plan: putting people at the heart of public services. London: DoH, 2004.

- 3.Department of Health. National standards, local action: health and social care standards and planning framework 2005/06-2007/08. London: DoH, 2004. www.dh.gov.uk (search for 3533).

- 4.Newacheck P, Taylor W. Childhood chronic illness: prevalence, severity and impact. Am J Public Health 1992;82: 364-71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Office for National Statistics. Deaths by age, sex and underlying cause in England and Wales, 2003. London: Stationery Office, 2004.

- 6.Koivusilta LK, Rimpela AH, Rimpela MK. Health-related lifestyle in adolescence—origin of social class differences in health? Health Educ Res 1999;14: 339-55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.West P. Rethinking the health selection explanation for health inequalities. Soc Sci Med 1991;32: 373-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.West P. Health inequalities in the early years: is there equalisation in youth? Soc Sci Med 1997;44: 833-58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shrier LA, Emans SJ, Woods ER, DuRant RH. The association of sexual risk behaviors and problem drug behaviors in high school students. J Adolesc Health 1997;20: 377-83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Department of Health. Health survey for England 2002. London: Stationery Office, 2003.

- 11.Resnick MD, Bearman PS, Blum R, Bauman KE, Harris KM, Jones J. et al. Protecting adolescents from harm. Findings from the national longitudinal study on adolescent health. JAMA 1998;278: 823-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bond L, Glover S, Godfrey C, Butler H, Patton GC. Building capacity for system-level change in schools: lessons from the Gatehouse project. Health Educ Behav 2001;28: 368-83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gortmaker SL, Peterson K, Wiecha J, Sobol AM, Dixit S, Fox MK, et al. Reducing obesity via a school-based interdisciplinary intervention among youth: planet health. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 1999;153: 409-18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Viner RM. National survey of use of hospital beds by adolescents aged 12 to 19 in the United Kingdom. BMJ 2001;322: 957-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Royal College of Psychiatrists Research Unit. National in-patient child and adolescent psychiatry study (NICAPS). London: RCPsych, 2001.

- 16.Joint Working Party on Adolescent Health of the Royal Medical and Nursing Colleges of the UK. Bridging the gaps: healthcare for adolescent. London: Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health, 2003.

- 17.Jacobson LD, Wilkinson C, Owen P. Is the potential of teenage consultations being missed? A study of consultation times in primary care. Fam Pract 1994;11: 296-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jacobson L, Richardson G, Parry-Langdon N, Donovan C. How do teenagers and primary healthcare providers view each other? An overview of key themes. Br J Gen Pract 2001;51: 811-6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Patton GC, Glover S, Bond L, Butler H, Godfrey C, Di Pietro G, et al. The Gatehouse project: a systematic approach to mental health promotion in secondary schools. Aust NZ J Psychiatry 2000;34: 586-93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sanci LA, Coffey CM, Veit FC, Carr-Gregg M, Patton GC, Day N, et al. Evaluation of the effectiveness of an educational intervention for general practitioners in adolescent health care: randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2000;320: 224-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wiecha JL, El Ayadi AM, Fuemmeler BF, Carter JE, Handler S, Johnson S, et al. Diffusion of an integrated health education program in an urban school system: planet health. J Pediatr Psychol 2004;29: 467-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Patton G. An epidemiological case for a separate adolescent psychiatry? Aust NZ J Psychiatry 1996;30: 563-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.