Abstract

BACKGROUND CONTEXT

Osteosarcoma (OGS) and Ewing sarcoma (EWS) are the two classic primary malignant bone tumors. Due to the rarity of these tumors, evidence on demographics, survival determinants, and treatment outcomes for primary disease of the spine are limited and derived from small case series.

PURPOSE

To use population-level data to determine the epidemiology and prognostic indicators in patients with OGS and EWS of the osseous spine.

STUDY DESIGN/SETTING

Large-scale retrospective study.

PATIENT SAMPLE

Patients diagnosed with OGS and EWS of the spine in the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) registry from 1973 to 2012.

OUTCOME MEASURES

Overall survival (OS) and disease-specific survival (DSS).

METHODS

Two separate queries of the SEER registry were performed to identify patients with OGS and EWS of the osseous spine from 1973–2012. Study variables included age, sex, race, year of diagnosis, tumor size, extent of disease (EOD), and treatment with surgery and/or radiation therapy. Primary outcome was defined as OS and DSS in months. Univariate survival analysis was performed using the Kaplan-Meier method and the log-rank test. Multivariate analysis was performed using Cox proportional hazards regression models.

RESULTS

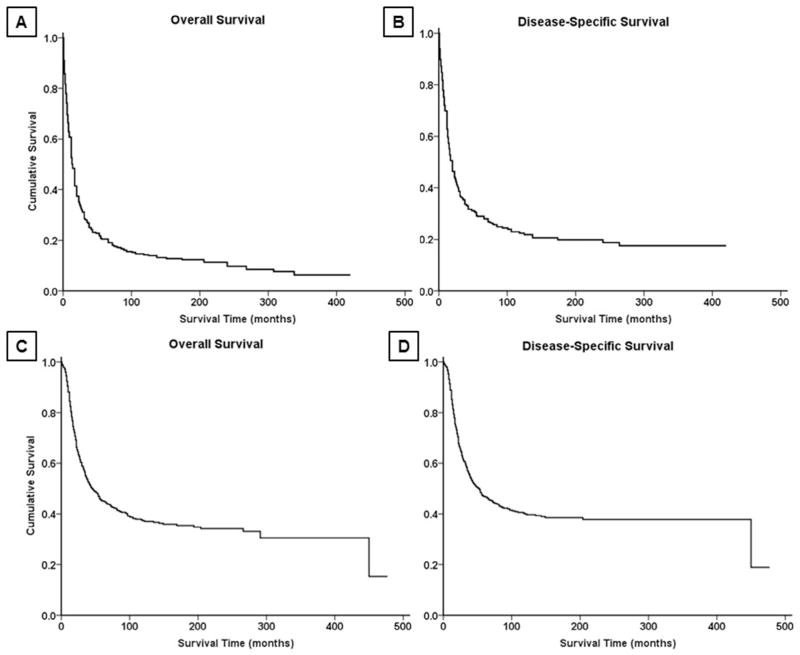

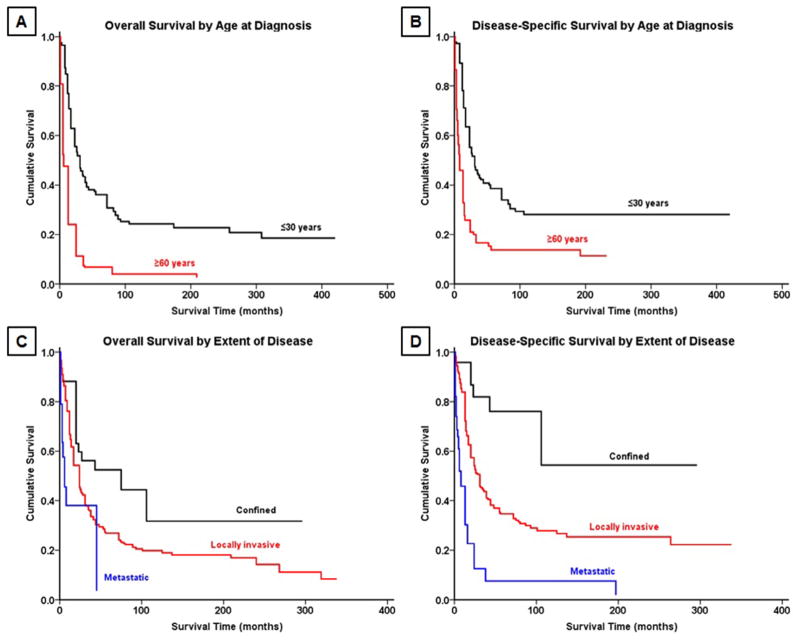

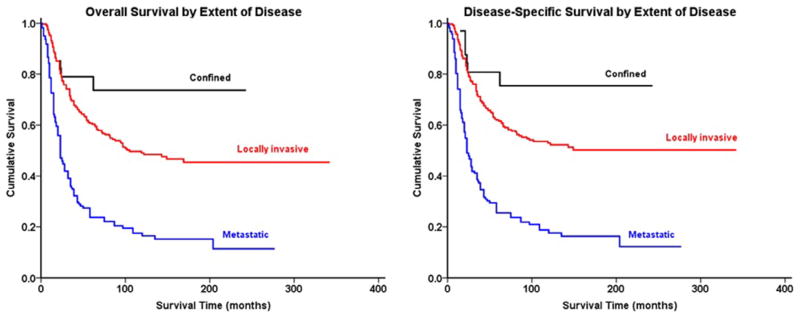

The search identified 648 patients with primary OGS and 736 patients with primary EWS of the spine from 1973 to 2012. Mean age at diagnosis was 48.1 and 19.9 years for OGS and EWS, respectively, with OGS showing a bimodal distribution. The median OS and DSS were 1.3 and 1.7 years, respectively, for OGS, with OGS in Paget’s disease having worse OS (0.7 years) relative to the mean (log-rank p=.006). The median OS and DSS for EWS were 3.9 and 4.3 years, respectively. Multivariate cox regression analysis showed that age (OS p<.001, DSS p<.001), decade of diagnosis (OS p=.049), surgical resection (OS p<.001, DSS p<.001), and EOD (OS p<.001, DSS p<.001) were independent positive prognostic indicators for spinal OGS; radiation therapy predicted worse OS (hazard ratio [HR] 1.48, confidence interval [CI] 1.05–2.10, p=.027) and DSS (HR 1.74, CI 1.13–2.66, p=.012) for OGS. For EWS, age (OS p<.001, DSS p<.001), surgical resection (OS p=.030, DSS p=.046), tumor size (OS p<.001, DSS p<.001), and EOD (OS p<.001, DSS p<.001) were independent determinants of improved survival; radiation therapy trended toward improved survival but did not achieve statistical significance for both OS (HR 0.76, CI 0.54–1.07, p=.113) and DSS (0.76, CI 0.54, 1.08, p=.126).

CONCLUSIONS

Age, surgical resection, and EOD are key survival determinants for both OGS and EWS of the spine. Radiation therapy may be associated with worse outcomes in patients with OGS, and is of potential benefit in EWS. Overall prognosis has improved in patients with OGS of the spine over the last four decades.

Keywords: Ewing sarcoma, Osteosarcoma, Radiation therapy, Spine, Surgical resection, Survival

Introduction

Malignant primary osseous tumors of the spine are rare, accounting for 5% of all osseous neoplasms [1]. Osteosarcoma (OGS) is the most frequently occurring malignant tumor of bone, with peak frequency in adolescence when the growth spurt occurs [2]. Despite histological variants, all OGS share in common neoplastic osteoblasts producing osteoid as the proliferating cell of origin. Histologically, four main subtypes of OGS exist based on the predominant cell type: osteogenic, chondroblastic, fibroblastic, and secondary OGS [2]. Ionizing radiation, Paget’s disease of the bone, enchondromatosis, hereditary multiple exostoses, and fibrous dysplasia have all been suggested to be risk factors and potential secondary causes for the development of OGS [3]. In the spine, they have a predilection for the lumbosacral region. The treatment of OGS has been drastically improved in the late 1980s to early 1990s by the introduction of staged multiagent chemotherapy [2,4,5]. In the treatment of OGS, chemotherapy typically precedes surgical treatment with local excision with wide margins so as to minimize the possibility of local recurrence or metastatic dissemination [6]. Similar to other primary osseous tumors such as chondrosarcoma, OGS has been shown to be relatively resistant to radiotherapy [2,7–10]. Thus, radiation for OGS is generally reserved only for palliative therapy or for treating microscopic residual disease following surgery [11].

Ewing sarcoma (EWS) is the second most common malignant osseous tumor in children and adolescents (second only to OGS), occurring primarily in the second decade of life [2]. EWS encompasses a group of small round blue cell malignancies, of which 85%–90% have the classic t(11;22) EWS/FLI1 translocation. Therapy for EWS includes aggressive multimodal therapy with radiation, surgery, and chemotherapy, which allows 50%–60% of those without metastases to achieve long-term, relapse-free survival [2]. Although it is widely accepted that treatment should begin with chemotherapy (as with OGS), subsequent therapy with radiation and surgery and the degree to which each is performed are still debated [13–15].

Small case series of treatment outcomes for patients with spinal OGS or EWS at individual institutions have been reported [12,16,17], but due partially to the infrequency of this malignancy in the axial skeleton, reports have been limited in terms of number of patients despite data spanning several decades. The Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) registry began collecting cancer-related information in 1973 and today represents 30% of the US population, serving as a comprehensive source of population-level cancer data [18]. The advantages of using such a database include multi-institutional data with a large patient pool for greater statistical power. The SEER database has been queried in a series of reports in the past to include all malignant tumors of the osseous spine, including OGS and EWS from 1973 to 2003 [1,19–21]. However, analyses of treatment modalities have not been performed using multivariate regression to account for confounding factors and identify independent prognostic indicators in the treatment of spinal OGS or EWS to date. The purpose of the present study was to use the SEER database to report updated data on demographics and clinicopathologic features, as well as use multivariate regression modeling to compare and contrast specific prognostic indicators and treatment outcomes for patients with high-grade OGS and EWS of the osseous spine from 1973 to 2012.

Materials and methods

A population-based search for patients diagnosed with OGS and EWS of the spine was performed using the case-listing session protocol of the National Cancer Institute’s SEER 18 database [www.seer.cancer.gov]. No internal review board approval was required in the present study because the database uses publicly available information with no personal identifiers. The SEER database is widely used and has been validated independently for analysis of primary osseous tumors of the extremities [22] and spine [2,20].

Patients diagnosed with OGS of the spine from 1973 to 2012, the widest date ranges available in the latest version of the software, were reviewed. Site-specific codes were first used to identify all primary tumors that originated in the osseous spine: C41.2 (vertebral column) and C41.4 (pelvic bones, sacrum, coccyx, and associated joints). Histologic International Classification of Diseases (ICD)-0-3 codes were then reviewed for all cases to identify the following histological subtypes with at least one case for osteosarcoma: “osteosarcoma, NOS” (9180/3), “chondroblastic osteosarcoma” (9181/3), “fibroblastic osteosarcoma” (9182/3), “telangiectatic osteosarcoma” (9183/3), “osteosarcoma in Paget’s disease” (9184/3), “small cell osteosarcoma” (9185/3), “central osteosarcoma” (9186/3), “intraosseous well-differentiated osteosarcoma” (9187/3), “periosteal osteosarcoma” (9193/3), and “high grade surface osteosarcoma” (9194/3). “Parosteal osteosarcoma” (9192/3) was excluded from the study as they are low-grade tumors by definition. EWS was identified using the single ICD code “Ewing sarcoma” (9260/3). The following primary data were extracted for analysis: patient age, year of diagnosis, sex, race, histologic subtype (ICD), tumor extent and tumor size from both extent of disease (EOD) and collaborative stage (CS) coding methods, treatment with surgery and/or radiation therapy, cause of death, and survival months. Extent of disease was manually reclassified using EOD and CS coding into three main categories as previously established in the literature [19]: confined (defined as tumor encasement within the periosteum), locally invasive (defined as further contiguous extension beyond the periosteum without distant involvement), and metastatic. The SEER registry provides no data relating to the use of chemotherapy and chemotherapy was not an analyzed treatment modality in the present study.

Primary outcome was defined as time in months from diagnosis to death from any cause for overall survival (OS), and time from diagnosis to death specific to the cancer-related diagnosis for disease-specific survival (DSS). Descriptive epidemiological and survival statistics were calculated for all variables. OS and DSS curves were calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method. Differences in survival were inferentially tested using the log-rank test with either pairwise or stratified comparison for categorical and ordinal or continuous, respectively. Covariates were assessed for predictive performance with multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression models, using hazard ratios with corresponding 95% confidence intervals, with regard to OS and DSS. Comparisons between groups were deemed statistically significant at the p<.05 threshold. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 21 software (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

Demographic data

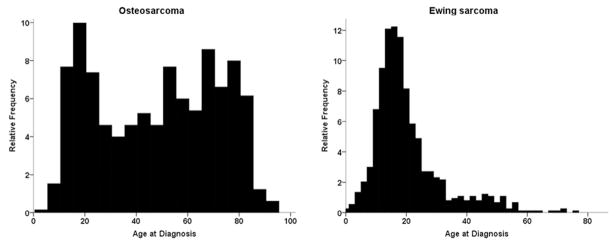

The search identified 648 patients with primary OGS and 736 patients with primary EWS of the osseous spine from 1973 to 2012. Among cases of OGS, chondroblastic (15.7%), fibroblastic (4.5%), and OGS in Paget’s disease (4.3%) were the most common histologic variants, with the majority of cases being listed as OGS, not otherwise specified (Table 1). Demographically, 55.4% and 63.9% of patients with OGS and EWS, respectively, were male (Table 2); 82.2% of patients with OGS and 91.0% of patients with EWS were white. For patients with OGS, the mean and median ages were 48.1 and 51 years, respectively, with ages ranging from 3 to 94 and a bimodal distribution (Fig. 1). For EWS, the mean and median ages were 19.9 and 17 years, with age ranging from 0 (diagnosed at birth) to 75 years, with unimodal distribution (Fig. 1). At diagnosis, 59.3% and 60.5% of cases of OGS and EWS, respectively, were from the year 2000 and beyond. Extent of disease was known in 77.8% of OGS cases, with the majority of cases presenting as locally invasive disease (48.2%), with similar findings in EWS cases—known in 82.6% and 47.6% locally invasive. The average tumor size at the time of diagnosis was similar across both OGS (8.8±5.8 cm) and EWS (8.1±5.6 cm). After diagnosis, 12.0% of patients with OGS received both surgery and radiation, 38.3% underwent surgery alone, and 15.9% underwent radiation alone; 28.9% received neither surgical resection nor radiation therapy. For patients with EWS, 24.9% received both surgery and radiation, 14.3% underwent surgery alone, and 37.9% underwent radiation only; 17.3% received neither surgical resection nor radiation therapy.

Table 1.

Histologic subtype of osteosarcoma of the spine (n=648)

| Subtype | % of cohort (n) |

|---|---|

| Osteosarcoma, not otherwise specified | 70.9 (460) |

| Chondroblastic osteosarcoma | 15.7 (102) |

| Fibroblastic osteosarcoma | 4.5 (29) |

| Telangiectatic osteosarcoma | 1.7 (11) |

| Osteosarcoma in Paget disease | 4.3 (28) |

| Small-cell osteosarcoma | 1.4 (9) |

| Central osteosarcoma | 0.8 (5) |

| Intraosseous well-differentiated osteosarcoma | 0.3 (2) |

| Periosteal osteosarcoma | 0.2 (1) |

| High-grade surface osteosarcoma | 0.2 (1) |

Table 2.

Osteosarcoma (n=648) and Ewing sarcoma demographics (n=736)

| Osteosarcoma (n=648) | Ewing sarcoma (n=736) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Years | Age | Years |

| Mean | 48.1±23.8 | Mean | 19.9±11.6 |

| Median | 51 | Median | 17.0 |

| Min | 3 | Min | 0 |

| Max | 94 | Max | 75 |

| Characteristic | Percentage (n) | Characteristic | Percentage (n) |

| Sex | Sex | ||

| Female | 44.6 (289) | Female | 36.1 (266) |

| Male | 55.4 (359) | Male | 63.9 (470) |

| Race | Race | ||

| White | 82.2 (533) | White | 91.0 (670) |

| Black | 11.1 (72) | Black | 2.9 (21) |

| Other | 6.5 (42) | Other | 6.0 (44) |

| Unknown | 0.2 (1) | Unknown | 0.1 (1) |

| Decade | Decade | ||

| 1970s | 9.4 (61) | 1970s | 7.9 (58) |

| 1980s | 13.2 (86) | 1980s | 11.5 (85) |

| 1990s | 18.1 (117) | 1990s | 20.1 (148) |

| 2000s | 59.3 (384) | 2000s | 60.5 (448) |

| Extent of disease | Extent of disease | ||

| Confined | 5.2 (34) | Confined | 4.6 (34) |

| Locally invasive | 48.2 (312) | Locally invasive | 47.6 (350) |

| Metastasis | 24.4 (158) | Metastasis | 30.4 (224) |

| Unknown | 22.2 (144) | Unknown | 17.4 (128) |

| Surgery performed* | Surgery performed* | ||

| Yes | 50.0 (324) | Yes | 40.2 (296) |

| No | 46.8 (303) | No | 56.1 (413) |

| Unknown | 3.2 (21) | Unknown | 3.7 (27) |

| Radiation therapy* | Radiation therapy* | ||

| Yes | 29.9 (194) | Yes | 65.1 (479) |

| No | 68.2 (442) | No | 31.9 (235) |

| Unknown* | 1.8 (12) | Unknown* | 3.0 (22) |

| Treatment modality* | Treatment modality* | ||

| Surgery+Radiation | 12.0 (78) | Surgery+Radiation | 24.9 (183) |

| Surgery only | 38.3 (248) | Surgery only | 14.3 (105) |

| Radiation only | 15.9 (103) | Radiation only | 37.9 (279) |

| No therapy | 28.9 (187) | No therapy | 17.3 (127) |

| Unknown* | 4.9 (32) | Unknown* | 5.7 (42) |

| Size (cm) | Size (cm) | ||

| Mean | 8.8±5.8 | Mean | 8.1±5.6 |

| Median | 8.0 | Median | 7.5 |

Indicates that category distributions for surgery performed and radiation therapy are not additive to treatment modality because they are not necessarily independent events.

Fig. 1.

Age distribution histograms for cohorts of patients with osteosarcoma (OGS) and Ewing sarcoma of the osseous spine. OGS demonstrates a bimodal age distribution with peaks in the teen years and ≥60 years.

Univariate survival analysis

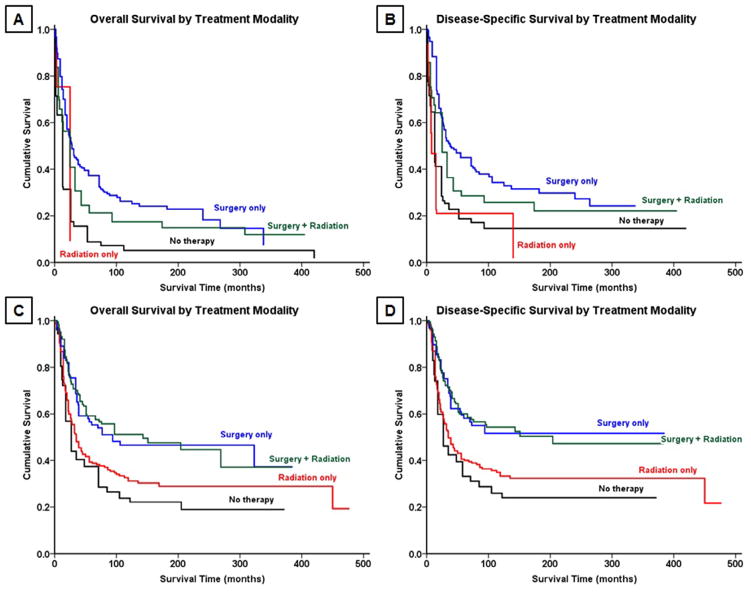

Survival analysis from Kaplan-Meier curves (Fig. 2A–B) revealed that the 5-year OS and DSS for all patients with OGS of the spine were 18% and 27%, respectively (Table 3). In contrast, patients with EWS (Fig. 2C–D) had a 5-year OS of 44% and DSS of 45%. Demographically, the Kaplan-Meier univariate survival analysis revealed that greater age was associated with worse survival for both OGS, with patients ≥60 years having significantly worse prognosis than patients under age 30 (OS log-rank p<.001, DSS log-rank p<.001, Table 4, Fig. 3A–B), and EWS (OS log-rank p<.001, DSS log-rank p<.001, Table 4). As a cohort, in patients with EWS, white patients had significantly better survival than black patients (OS log-rank p=.013, DSS log-rank p=.026); no significant racial differences in survival were seen, however, in patients with OGS (OS log-rank p=.800, DSS log-rank p=.825). OS and DSS showed a statistically significant difference in survival based on EOD at presentation in both OGS (OS log-rank p<.001, DSS log-rank p<.001, Fig. 3C–D) and EWS (OS log-rank p<.001, DSS log-rank p<.001, Fig. 4A–B). Similarly, increasing tumor size was associated with worse survival for both OGS (OS log-rank p<.001, DSS log-rank p<.001) and EWS (OS log-rank p<.001, DSS log-rank p<.001). For both OGS and EWS, sex was not associated with significant differences in survival (Table 4). More recent decade of diagnosis was associated with improved OS (log-rank p<.001) and DSS (log-rank p<.001) for EWS on univariate analysis; however, no such association was found for OGS. Among treatment groups for OGS, patients who underwent surgery demonstrated significantly better survival than patients who underwent surgery and radiation therapy (OS log-rank p=.032, DSS log-rank p=.023, Table 4, Fig. 5A–B); radiation therapy was associated with worse outcomes on Kaplan-Meier analysis. For EWS, surgical resection was associated with improved outcomes for both OS and DSS (OS log-rank p<.001, DSS log-rank p<.001, Fig. 5C–D) whereas radiation therapy was not associated with a statistically significant change in survival for cohorts overall or when combined with surgery (Table 4).

Fig. 2.

Kaplan-Meier analysis of overall survival and disease-specific survival in patients with (A,B) osteosarcoma and (C,D) Ewing sarcoma of the spine.

Table 3.

Survival data

| Osteosarcoma (n=648) | ||

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Median survival (years) | Overall survival | Disease-specific survival |

| Overall | 1.3 | 1.7 |

| Age at diagnosis | ||

| ≤30 years | 2.5 | 2.5 |

| ≥60 years | 0.7 | 0.8 |

| Subtype (minimum 10 cases) | ||

| Osteosarcoma, not otherwise specified | 1.1 | 1.6 |

| Chondroblastic osteosarcoma | 1.7 | 1.9 |

| Fibroblastic osteosarcoma | 2.7 | 6.1 |

| Telangiectatic osteosarcoma | 2.8 | 2.8 |

| Osteosarcoma in Paget’s disease | 0.7 | 1.2 |

| Decade of diagnosis | ||

| 1970s | 0.9 | 1.0 |

| 1980s | 0.9 | 1.2 |

| 1990s | 1.3 | 1.6 |

| 2000s | 1.5 | 2.0 |

| Extent of disease | ||

| Confined | 4.3 | N/A |

| Locally invasive | 1.9 | 2.5 |

| Metastatic | 0.7 | 0.8 |

| Treatment modality | ||

| Surgery+Radiation therapy | 1.7 | 2.2 |

| Surgery only | 3.6 | 3.4 |

| Radiation only | 0.7 | 0.8 |

| No therapy | 0.8 | 1.0 |

|

| ||

| Percent survival | ||

|

| ||

| At 2 years | 27 | 36 |

| At 5 years | 18 | 27 |

| At 10 years | 14 | 22 |

|

| ||

| Ewing sarcoma (n=736) | ||

|

| ||

| Median survival (years) | Overall survival | Disease-specific survival |

|

| ||

| Overall | 3.9 | 4.3 |

| Decade of diagnosis | ||

| 1970s | 1.7 | 1.7 |

| 1980s | 2.5 | 2.7 |

| 1990s | 3.6 | 4.0 |

| 2000s | 5.9 | 6.3 |

| Extent of disease | ||

| Confined | N/A | N/A |

| Locally invasive | 8.9 | N/A |

| Metastatic | 1.9 | 2.0 |

| Treatment modality | ||

| Surgery+Radiation therapy | 11.6 | 16.1 |

| Surgery only | 6.7 | N/A |

| Radiation only | 2.8 | 3.0 |

| No therapy | 2.0 | 2.2 |

| Percent survival | ||

| At 2 years | 55 | 57 |

| At 5 years | 44 | 45 |

| At 10 years | 37 | 40 |

Table 4.

Univariate analysis of variables using Kaplan-Meier method

| Osteosarcoma (n=648) | ||

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Characteristic | OS (log-rank p) | DSS (log-rank p) |

| Age at diagnosis | <.001 | <.001 |

| Age at diagnosis (≤30 vs. ≥60 years) | <.001 | <.001 |

| Race | ||

| White vs. Black | .800 | .825 |

| Black vs. Other | .752 | .687 |

| White vs. Other | .864 | .675 |

| Sex | .288 | .585 |

| Decade of diagnosis | .381 | .249 |

| Subtype | ||

| Osteoblastic vs. chondroblastic | .006 | .201 |

| Osteoblastic vs. fibroblastic | .005 | .031 |

| Osteoblastic vs. telangiectatic | .022 | .184 |

| Osteoblastic vs. Paget | .076 | .869 |

| Chondroblastic vs. fibroblastic | .231 | .088 |

| Chondroblastic vs. telangiectatic | .239 | .394 |

| Chondroblastic vs. Paget | .001 | .475 |

| Fibroblastic vs. telangiectatic | .618 | .900 |

| Fibroblastic vs. Paget | .001 | .152 |

| Telangiectatic vs. Paget | .007 | .751 |

| Surgical resection | <.001 | <.001 |

| Radiation therapy | <.001 | <.001 |

| Treatment modality | <.001 | <.001 |

| Surgery+Radiation vs. Surgery only | .032 | .023 |

| Surgery+Radiation vs. Radiation only | <.001 | <.001 |

| Surgery+Radiation vs. No therapy | <.001 | .014 |

| Surgery vs. Radiation only | <.001 | <.001 |

| Surgery vs. No therapy | <.001 | <.001 |

| Radiation vs. No therapy | .155 | .014 |

| Extent of disease | <.001 | <.001 |

| Size (cm) | <.001 | <.001 |

|

| ||

| Ewing sarcoma (n=736) | ||

|

| ||

| Characteristic | OS (log-rank p) | DSS (log-rank p) |

|

| ||

| Age at diagnosis | <.001 | <.001 |

| Race | ||

| White vs. Black | .013 | .029 |

| Black vs. Other | .545 | .746 |

| White vs. Other | .021 | .021 |

| Sex | .546 | .541 |

| Decade of diagnosis | <.001 | <.001 |

| Surgical resection | <.001 | <.001 |

| Radiation therapy | .113 | .211 |

| Treatment modality | ||

| Surgery+Radiation vs. Surgery only | .675 | .893 |

| Surgery+Radiation vs. Radiation only | <.001 | <.001 |

| Surgery+Radiation vs. No therapy | <.001 | <.001 |

| Surgery vs. Radiation only | .005 | .002 |

| Surgery vs. No therapy | <.001 | <.001 |

| Radiation vs. No therapy | .032 | .076 |

| Extent of disease | <.001 | <.001 |

| Size (cm) | <.001 | <.001 |

Fig. 3.

Kaplan-Meier analysis demonstrating overall survival and disease-specific survival in patients with osteosarcoma of the spine stratified by (A,B) age and (C,D) extent of disease.

Fig. 4.

Kaplan-Meier analysis demonstrating (left) overall survival and (right) disease-specific survival in patients with Ewing sarcoma of the spine stratified by extent of disease.

Fig. 5.

Kaplan-Meier analysis demonstrating overall survival and disease-specific survival by treatment modality with surgical resection and/or radiation therapy for patients with (A,B) osteosarcoma and (C,D) Ewing sarcoma.

Multivariate analysis and independent prognostic indicators

Using our multivariate analysis model (Table 5) for patients with OGS, age at diagnosis (hazard ratio [HR] 1.03, confidence interval [CI] 1.02–1.04, p<.001), radiation therapy (HR 1.48, CI 1.05–2.10, p=.027), and EOD (HR 2.49, CI 1.82–3.41, p<.001) were found to be independent negative predictors of OS, whereas more recent decade of diagnosis (HR 0.77, CI 0.59–0.99, p=.049) and surgical resection (HR 0.55, CI 0.38–0.75, p<.001) were found to be a positive predictor. Age (HR 1.02, CI 1.01–1.03, p<.001), radiation therapy (HR 1.79, CI 1.17–2.73, p=.007), and EOD (HR 2.34, CI 1.58–3.48, p<.001) were found to be negative independent predictors, and surgical resection (HR 0.46, CI 0.31–0.69, p<.001) was a positive predictor for DSS.

Table 5.

Cox proportional hazards model for multivariate analysis

| Characteristic | Overall survival

|

Disease-specific survival

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | p-Value | HR (95% CI) | p-Value | |

| All osteosarcoma cases (n=648) | ||||

| Age | 1.03 (1.02–1.04) | <.001 | 1.02 (1.01–1.03) | <.001 |

| Race | 1.13 (0.90–1.42) | .310 | 1.11 (0.83–1.50) | .473 |

| Sex | 0.78 (0.57–1.07) | .124 | 0.80 (0.54–1.19) | .276 |

| Decade of diagnosis | 0.77 (0.59–0.99) | .049 | 0.83 (0.60–1.15) | .261 |

| Tumor subtype | 1.01 (0.91–1.12) | .918 | 1.04 (0.93–1.16) | .545 |

| Surgery | 0.55 (0.40–0.77) | <.001 | 0.46 (0.31–0.69) | <.001 |

| Radiation therapy | 1.48 (1.05–2.10) | .027 | 1.79 (1.17–2.73) | .007 |

| Size (cm) | 1.00 (0.98–1.03) | .784 | 1.01 (0.98–1.05) | .470 |

| Extent of disease | 2.49 (1.82–3.41) | <.001 | 2.34 (1.57–3.48) | <.001 |

| Osteosarcoma: 1990–2012 (n=501) | ||||

| Age | 1.02 (1.01–1.03) | <.001 | 1.02 (1.01–1.03) | <.001 |

| Race | 1.12 (0.89–1.41) | .317 | 1.10 (0.82–1.48) | .517 |

| Sex | 0.81 (0.58–1.12) | .205 | 0.82 (0.55–1.23) | .336 |

| Tumor subtype | 1.01 (0.91–1.12) | .824 | 1.04 (0.93–1.16) | .491 |

| Surgery | 0.53 (0.38–0.75) | <.001 | 0.45 (0.29–0.68) | <.001 |

| Radiation therapy | 1.49 (1.05–2.12) | .027 | 1.74 (1.13–2.66) | .012 |

| Size (cm) | 1.02 (0.99–1.05) | .202 | 1.02 (0.99–1.06) | .267 |

| Extent of disease | 2.32 (1.68–3.20) | <.001 | 2.23 (1.48–3.36) | <.001 |

| All Ewing sarcoma cases (n=736) | ||||

| Age | 1.03 (1.01–1.04) | <.001 | 1.03 (1.02–1.05) | <.001 |

| Race | 1.41 (1.08–1.83) | .011 | 1.50 (1.12–2.00) | .006 |

| Sex | 0.88 (0.65–1.21) | .432 | 0.91 (0.65–1.26) | .559 |

| Decade of diagnosis | 0.80 (0.61–1.03) | .085 | 0.81 (0.61–1.07) | .131 |

| Surgery | 0.69 (0.49–0.96) | .030 | 0.72 (0.50–1.02) | .064 |

| Radiation therapy | 0.78 (0.57–1.08) | .139 | 0.82 (0.58–1.15) | .238 |

| Size (cm) | 1.05 (1.03–1.08) | <.001 | 1.05 (1.02–1.08) | <.001 |

| Extent of disease | 2.72 (2.00–3.70) | <.001 | 2.67 (1.94–3.68) | <.001 |

| Ewing sarcoma: 1990–2012 (n=596) | ||||

| Age | 1.02 (1.01–1.04) | <.001 | 1.03 (1.02–1.05) | <.001 |

| Race | 1.40 (1.06–1.84) | .017 | 1.57 (1.17–2.11) | .003 |

| Sex | 0.87 (0.63–1.20) | .394 | 0.87 (0.63–1.22) | .431 |

| Surgery | 0.64 (0.45–0.91) | .012 | 0.69 (0.48–0.99) | .046 |

| Radiation therapy | 0.76 (0.54–1.07) | .113 | 0.76 (0.54–1.08) | .126 |

| Size (cm) | 1.05 (1.02–1.09) | .002 | 1.05 (1.01–1.08) | .011 |

| Extent of disease | 2.56 (1.87–3.51) | <.001 | 2.59 (1.87–3.58) | <.001 |

CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio.

In patients with EWS, age (HR 1.03, CI 1.01–1.04, p<.001) and EOD (HR 2.72, CI 2.00–3.70, p<.001) were, similar to OGS, both independent negative predictors of OS, but also were race (HR 1.41, CI 1.08–1.83, p=.011) and tumor size (HR 1.05, CI 1.03–1.08, p<.001). Similar to OGS, surgical intervention conferred improved OS in patients with EWS. Unlike patients with OGS, however, neither decade of diagnosis nor radiation therapy had bearing on OS in patients with EWS. In analysis of DSS, only age (HR 1.03, CI 1.02–1.05, p<.001), tumor size (HR 1.05, CI 1.02–1.08, p<.001), and EOD (HR 2.67, CI 1.94–3.68, p<.001) were found to be negative predictors. No significant positive predictors of DSS in patients with EWS were found (Table 5).

Sex and tumor subtype were nonsignificant independent predictors of both OS and DSS across both OGS and EWS. Finally, to account for the potential advances in radiotherapy influencing survival, the multivariate analysis model was next used to ascertain the independent effects of these variables on survival in patients treated after the year 1990. There was no difference in outcomes from the cohort for all years with respect to radiotherapy (Table 5).

Discussion

Both OGS and EWS of the osseous spine are considered to be rare malignancies, and have the potential for both locally invasive destruction and systemic metastasis. As primary osseous tumors of the spine, they are difficult to control due to both their invasive nature and their proximity to critical structures of the spinal cord and nerve roots, precluding widely negative surgical margins in a significant proportion of cases [15]. This limitation, in combination with the paucity of reported case series of spinal OGS or EWS, has fueled debate surrounding optimal treatment. In the present study, we used the SEER registry to characterize and compare the epidemiology, prognostic determinants, and treatment outcomes of patients with OGS and EWS of the osseous spine. Advantages of such a study design include a large sample size and statistical power otherwise unachievable through conventional chart review at a single institutional level.

Our study found the average age at diagnosis of OGS to be 48.1 and EWS to be 19.9 years. Whereas EWS is roughly normally distributed about the mean, OGS has a bimodal age distribution. We also found that there was a 3:2 predilection of males to females in EWS, which has been previously supported in smaller studies of EWS [12]. No gender predilection was found, however, in our cohort of OGS patients, despite previous literature with smaller case series citing a male predilection [23]. In terms of survival outcomes, patients with spinal OGS had a dismal overall median survival of 1.3 years, and a 5-year OS and DSS of 18% and 27%, respectively. These outcomes were poorer relative to patients with EWS, who had an overall median survival of 3.9 years and 5-year OS and DSS of 44% and 45%. It should be noted that among tumor histologies of OGS, we found that OGS in the context of Paget’s disease portended a relatively dismal prognosis in the spine (OS of 0.7 years) when compared with the rest of the patient cohort of OGS. These are recognized as particularly aggressive tumors and frequently occur in patients who are of older age [24,25]. Difference in survival between OGS in Paget’s disease may be due to Paget’s occurring relatively in older patients [25,26], who may be less tolerant of chemotherapy and with other comorbidities rendering a lower likelihood of surviving cancer overall. Independent of age, however, distinct biology of osteosarcoma has been reported in Paget’s, in which stromal elements may play a role in the malignant degeneration of bone [25], which may likely result in more aggressive disease and thus shorter survival.

We also found EOD to be an independent prognostic indicator of both OS and DSS across both EWS and OGS. This association stands to reason when considering that both these malignancies are classically known to be aggressive malignancies with significant soft tissue extension, particularly in the spine [23,27]. Notably, tumor size was found to be an independent survival determinant in patients with OGS, a finding that is consistent with prior cohort studies with smaller patient pools [17]. In contrast to OGS, however, tumor size in EWS showed no predictive ability for survival across both OS and DSS.

The present study also found that patient age at diagnosis portended worse outcomes in both OS and DSS for both OGS and EWS. This trend is understandable given the aggressive therapies needed to treat such diseases. In the case of OGS, the poorer outcomes in Paget’s disease stands to reason when considering that patients diagnosed with the disease are generally of older age. In context, this finding is consistent with children tolerating higher doses of chemotherapy [28]. Although there was no racial predilection found in terms of survival for patients with OGS, in patients with EWS, black patients did have significantly worse outcomes than white patients. It is known that EWS is less common in patients of African descent [2]; thus, this finding may be due to a lower pretest probability of EWS in the black population, leading to diagnosis at a later stage in the disease. Although there was an observed trend, the decade of diagnosis (1970s, 1980s, etc.) was not found to be associated with a statistically significant improvement in OS in multivariate analysis of EWS. However, multivariate analysis showed that OS in patients with OGS did significantly improve based on decade of diagnosis, consistent with prior reports. In context, this may likely be due to the introduction of multiagent chemotherapy for OGS in the early 1990s [4], a time before single agent chemotherapy was used.

With regard to treatment outcomes, the multivariate linear regression model used in the present study assesses the independence of the effect of these treatment modalities to confounding factors such as age, tumor grade, and EOD. In our univariate Kaplan-Meier analysis of treatment modalities, we found that patients who underwent surgical resection in both OGS and EWS had significantly improved survival. Although patients who received radiation therapy had an overall worse prognosis in OGS, a trend toward improvement in survival (but without statistically significant prognostic effect) was observed in EWS of the spine. This finding is consistent despite accounting for EOD and other variables such as tumor size and age in our multivariate model, and furthermore, when doing separate analyses for patients diagnosed after 1990 to account for contemporary improvements in radiotherapy technology over time. OGS is notoriously radioresistant [29,30]; thus, radiotherapy is likely not a good therapy in the treatment of OGS in the spine unless used for palliative purposes or as a last resort. Indeed, we acknowledge the high likelihood of confounding bias here, wherein clinicians treating patients in the present study cohort are more likely to use radiotherapy in patients with advanced OGS of the spine. Here, radiotherapy is likely more frequently used for locoregional control in inoperable cases with significant cord compression [31–33]. In patients with EWS, a study with 512 patients by Bacci et al. showed that radiotherapy may be of potential benefit to patients if adequate surgical margins could not be achieved and full dose (44.8 Gy) is used [34]. Notably, however, the study found that radiotherapy adjuvant to surgery conferred no benefit to patients when adequate surgical margins could be attained [34]. Nevertheless, although our study did note a nonstatistically significant trend toward improvement in survival in EWS, caution must be heeded before administration of radiotherapy, as sarcoma secondary to radiotherapy after EWS is well known and shown to occur in a dose-dependent manner [35]. We acknowledge that the SEER database cannot clearly and simply elucidate an explanation for such a differential effect of radiation therapy in survival. For instance, it may be possible that subjects receiving radiotherapy were more likely to have locally invasive disease precluding surgery or be inoperable, thus already portending a worse prognosis before therapy, a possibility that could not be captured by the resolution of EOD found in the SEER database. Future institutional studies focusing exclusively on OGS and EWS of the spine may be warranted to delineate this as well as the role of advances in targeted radiotherapy.

Treatment for both spinal OGS and EWS has traditionally consisted of multimodal therapy, with neoadjuvant multiagent chemotherapy followed by surgery and radiation [28]. Although the SEER database reports whether surgical intervention was performed, no data on use of chemotherapy or specific type of chemotherapy are available in the database, representing a limitation of the present study, particularly with the advent of multiagent chemotherapy having had such a profound influence on improved survival in patients with OGS [2,4]. Furthermore, the SEER database is limited in its ability to retrospectively analyze certain other surgical variables, such as margin status, extent of surgical resection, and postoperative tumor recurrence. The use of SEER registry is not without other limitations, which includes limited ability to analyze variables such as temporality and methodology of radiation therapy, tumor recurrence, and medical comorbidities affecting survival. Finally, there are also concerns surrounding misclassification of clinicopathologic variables due to lack of centralized review by a pathologist. Despite these limitations, however, to our knowledge the present study represents the largest analysis evaluating the epidemiology, prognostic factors, and outcomes in patients with either OGS or EWS of the spine.

Conclusions

The present study represents the single largest series with comprehensive epidemiological and outcome data on patients with either OGS or EWS of the spine. Survival analysis suggests that surgical resection is beneficial across all patients presenting with tumors that are confined to the periosteum, locally invasive, or with disseminated metastases. Age at time of diagnosis, surgical resection, and EOD were found to be statistically and clinically significant survival determinants for both OGS and EWS of the spine. Treatment with radiotherapy may be associated with poorer outcomes in patients with OGS, whereas conferring potential benefit in those with EWS. Further studies examining different means of radiotherapy may shed more light with respect to improvements in outcomes.

Evidence & Methods.

Context

The authors accessed the SEER registry to gain insight into the prognosis and impact of treatments for osteosarcoma and Ewing’s sarcoma of the spine.

Contribution

They found that age, surgical resection, and extent of disease impacted outcomes; but that mean survival (especially of patients with osteosarcoma of the spine) remains, sadly, a major concern.

Implications

The value of registry assessments depends wholly on the quality of the data contained in the registry. Unfortunately, much data that might prove helpful are missing from the database. What was the impact of chemotherapy? Specific types of chemotherapy? While radiation appeared to negatively impact osteosarcoma outcomes, was this because they were more advanced and treatment was meant for pain relief (not survival) and actually helped in that role? That said, while many questions are unanswered by the study, the information and quality of analysis presented represent a step-up from the historical institutionally-based small case series reports of the past.

Acknowledgments

We thank the UCLA Statistical Consulting Group through the Institute for Digital Research and Education for assistance with statistical analysis.

Footnotes

FDA device/drug status: Not applicable.

Author disclosures: AA: Nothing to disclose. JS: Nothing to disclose. DYP: Nothing to disclose. HYP: Nothing to disclose. HY: Nothing to disclose. NMB: Nothing to disclose. ANS: Nothing to disclose.

References

- 1.Mukherjee D, Chaichana KL, Gokaslan ZL, Aaronson O, Cheng JS, McGirt MJ. Survival of patients with malignant primary osseous spinal neoplasms: results from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database from 1973 to 2003. J Neurosurg Spine. 2011;14:143–50. doi: 10.3171/2010.10.SPINE10189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sundaresan N, Rosen G, Boriani S. Primary malignant tumors of the spine. Orthop Clin North Am. 2009;40:21–36. doi: 10.1016/j.ocl.2008.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barker JP, Monument MJ, Jones KB, Putnam AR, Randall RL. Secondary osteosarcoma: is there a predilection for the chondroblastic subtype? Orthopedics. 2015;38:e359–66. doi: 10.3928/01477447-20150504-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sundaresan N, Rosen G, Huvos AG, Krol G. Combined treatment of osteosarcoma of the spine. Neurosurgery. 1988;23:714–19. doi: 10.1227/00006123-198812000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Meyers PA. Systemic therapy for osteosarcoma and Ewing sarcoma. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2015:e644–7. doi: 10.14694/EdBook_AM.2015.35.e644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kawahara N, Tomita K, Fujita T, Maruo S, Otsuka S, Kinoshita G. Osteosarcoma of the thoracolumbar spine: total en bloc spondylectomy. A case report. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1997;79:453–8. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199703000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Holliday EB, Mitra HS, Somerson JS, Rhines LD, Mahajan A, Brown PD, et al. Postoperative proton therapy for chordomas and chondrosarcomas of the spine. Spine. 2015;40:544–9. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0000000000000804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hsu W, Kosztowski TA, Zaidi HA, Dorsi M, Gokaslan ZL, Wolinsky J-P. Multidisciplinary management of primary tumors of the vertebral column. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2009;10:107–25. doi: 10.1007/s11864-009-0102-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Delaney TF, Kepka L, Goldberg SI, Hornicek FJ, Gebhardt MC, Yoon SS, et al. Radiation therapy for control of soft-tissue sarcomas resected with positive margins. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2007;67:1460–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.11.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zagars GK, Ballo MT. Significance of dose in postoperative radiotherapy for soft tissue sarcoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2003;56:473–81. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(02)04573-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.DeLaney TF, Park L, Goldberg SI, Hug EB, Liebsch NJ, Munzenrider JE, et al. Radiotherapy for local control of osteosarcoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2005;61:492–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2004.05.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marco RAW, Gentry JB, Rhines LD, Lewis VO, Wolinski JP, Jaffe N, et al. Ewing’s sarcoma of the mobile spine. Spine. 2005;30:769–73. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000157755.17502.d6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rock J, Kole M, Yin F-F, Ryu S, Guttierez J, Rosenblum M. Radiosurgical treatment for Ewing’s sarcoma of the lumbar spine: case report. Spine. 2002;27:E471–5. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200211010-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.La TH, Meyers PA, Wexler LH, Alektiar KM, Healey JH, Laquaglia MP, et al. Radiation therapy for Ewing’s sarcoma: results from Memorial Sloan-Kettering in the modern era. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006;64:544–50. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2005.07.299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schuck A, Ahrens S, von Schorlemer I, Kuhlen M, Paulussen M, Hunold A, et al. Radiotherapy in Ewing tumors of the vertebrae: treatment results and local relapse analysis of the CESS 81/86 and EICESS 92 trials. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2005;63:1562–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2005.05.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dini LI, Mendonça R, Gallo P. Primary Ewing sarcoma of the spine: case report. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2006;64:654–9. doi: 10.1590/s0004-282x2006000400026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ozaki T, Flege S, Liljenqvist U, Hillmann A, Delling G, Salzer-Kuntschik M, et al. Osteosarcoma of the spine: experience of the Cooperative Osteosarcoma Study Group. Cancer. 2002;94:1069–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nathoo N, Mendel E. The National Cancer Institute’s SEER registry and primary malignant osseous spine tumors. World Neurosurg. 2011;76:531–2. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2011.06.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mukherjee D, Chaichana KL, Adogwa O, Gokaslan Z, Aaronson O, Cheng JS, et al. Association of extent of local tumor invasion and survival in patients with malignant primary osseous spinal neoplasms from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database. World Neurosurg. 2011;76:580–5. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2011.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mukherjee D, Chaichana KL, Parker SL, Gokaslan ZL, McGirt MJ. Association of surgical resection and survival in patients with malignant primary osseous spinal neoplasms from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database. Eur Spine J. 2013;22:1375–82. doi: 10.1007/s00586-012-2621-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McGirt MJ, Gokaslan ZL, Chaichana KL. Preoperative grading scale to predict survival in patients undergoing resection of malignant primary osseous spinal neoplasms. Spine J. 2011;11:190–6. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2011.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Duchman KR, Lynch CF, Buckwalter JA, Miller BJ. Estimated cause-specific survival continues to improve over time in patients with chondrosarcoma. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014;472:2516–25. doi: 10.1007/s11999-014-3600-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Orguc S, Arkun R. Primary tumors of the spine. Semin Musculoskelet Radiol. 2014;18:280–99. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1375570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hansen MF, Nellissery MJ, Bhatia P. Common mechanisms of osteosarcoma and Paget’s disease. J Bone Miner Res. 1999;14(Suppl 2):39–44. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650140209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hansen MF, Seton M, Merchant A. Osteosarcoma in Paget’s disease of bone. J Bone Miner Res. 2006;21:P58–63. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.06s211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huvos AG, Butler A, Bretsky SS. Osteogenic sarcoma associated with Paget’s disease of bone. A clinicopathologic study of 65 patients. Cancer. 1983;52:1489–95. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19831015)52:8<1489::aid-cncr2820520826>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bernard S, Brian P, Flemming D. Primary osseous tumors of the spine. Semin Musculoskelet Radiol. 2013;17:203–20. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1343097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sciubba DM, Okuno SH, Dekutoski MB, Gokaslan ZL. Ewing and osteogenic sarcoma: evidence for multidisciplinary management. Spine. 2009;34:S58–68. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181ba6436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zuch D, Giang A-H, Shapovalov Y, Schwarz E, Rosier R, O’Keefe R, et al. Targeting radioresistant osteosarcoma cells with parthenolide. J Cell Biochem. 2012;113:1282–91. doi: 10.1002/jcb.24002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fuchs B, Pritchard DJ. Etiology of osteosarcoma. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2002:40–52. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200204000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schoenfeld AJ, Hornicek FJ, Pedlow FX, Kobayashi W, Garcia RT, DeLaney TF, et al. Osteosarcoma of the spine: experience in 26 patients treated at the Massachusetts General Hospital. Spine J. 2010;10:708–14. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2010.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang W, Tanaka M, Sugimoto Y, Takigawa T, Ozaki T. Carbon-ion radiotherapy of spinal osteosarcoma with long-term follow. Eur Spine J. 2016;25(Suppl 1):113–17. doi: 10.1007/s00586-015-4202-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Blattmann C, Oertel S, Schulz-Ertner D, Rieken S, Haufe S, Ewerbeck V, et al. Non-randomized therapy trial to determine the safety and efficacy of heavy ion radiotherapy in patients with non-resectable osteosarcoma. BMC Cancer. 2010;10:96. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-10-96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bacci G, Longhi A, Briccoli A, Bertoni F, Versari M, Picci P. The role of surgical margins in treatment of Ewing’s sarcoma family tumors: experience of a single institution with 512 patients treated with adjuvant and neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006;65:766–72. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kuttesch JF, Wexler LH, Marcus RB, Fairclough D, Weaver-McClure L, White M, et al. Second malignancies after Ewing’s sarcoma: radiation dose-dependency of secondary sarcomas. J Clin Oncol. 1996;14:2818–25. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1996.14.10.2818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]