Abstract

Context:

Ice hockey is a high-speed, full-contact sport with a high risk of head/face/neck (HFN) injuries. However, men's and women's ice hockey differ; checking is allowed only among men.

Objectives:

To describe the epidemiology of HFN injuries in collegiate men's and women's ice hockey during the 2009−2010 through 2013−2014 academic years.

Design:

Descriptive epidemiology study.

Setting:

Ice hockey data from the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) Injury Surveillance Program during the 2009−2010 through 2013−2014 academic years.

Patients or Other Participants:

Fifty-seven men's and 26 women's collegiate ice hockey programs from all NCAA divisions provided 106 and 51 team-seasons of data, respectively.

Main Outcome Measure(s):

Injury rates per 1000 athlete-exposures and rate ratios with 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

Results:

The NCAA Injury Surveillance Program reported 496 and 131 HFN injuries in men's and women's ice hockey, respectively. The HFN injury rate was higher in men than in women (1.75 versus 1.16/1000 athlete-exposures; incidence rate ratio = 1.51; 95% CI = 1.25, 1.84). The proportion of HFN injuries from checking was higher in men than in women for competitions (38.5% versus 13.6%; injury proportion ratio = 2.82; 95% CI = 1.64, 4.85) and practices (21.9% versus 2.3%; injury proportion ratio = 9.41; 95% CI = 1.31, 67.69). The most common HFN injury diagnosis was concussion; most concussions occurred in men's competitions from player contact while checking (25.9%). Player contact during general play comprised the largest proportion of concussions in men's practices (25.9%), women's competitions (25.0%), and women's practices (24.0%). While 166 lacerations were reported in men, none were reported in women. In men, most lacerations occurred from player contact during checking in competitions (41.8%) and player contact during general play in practices (15.0%).

Conclusions:

A larger proportion of HFN injuries in ice hockey occurred during checking in men versus women. Concussion was the most common HFN injury and was most often due to player contact. Lacerations were reported only among men and were mostly due to checking. Injury-prevention programs should aim to reduce checking-related injuries.

Key Words: concussions, lacerations, sex disparities

Key Points

Concussion was the most common head/face/neck (HFN) injury among collegiate ice hockey players.

The most common mechanism of HFN injuries was player contact; however, checking accounted for a larger proportion of HFN injuries.

Lacerations were reported only among men, and checking was the most common cause of lacerations.

Injury-prevention programs should aim to reduce checking-related injuries.

Sport-related head injuries are gaining recognition as a public health problem that affects millions of people in the United States.1 The risk is especially high for those who participate in elite amateur sports.2−4 A major concern in ice hockey is injuries sustained to the head/face/neck (HFN) due to the high speeds and contact involved in the sport.5,6 Among high school athletes, boys' ice hockey had the second highest rate of concussion behind football.3 Among female collegiate athletes, ice hockey had the highest rate of concussion.2,7

Despite the growing literature related to concussion in ice hockey, limited information is available on the epidemiology of HFN injuries among collegiate players.6,8 Concussions were the most common injury to male collegiate ice hockey players and the majority of injuries occurred in games.9 In an accelerometer study,8 male collegiate players accumulated more impacts than female players; these impacts tended to be harder (ie, higher linear acceleration) on average. Of particular interest is the role that checking may play in HNF injuries. The rules in men's collegiate and youth hockey allow for checking, whereas those in women's collegiate and youth hockey do not. Checking greatly increased the rate of head injuries among youth players.10

Although based on small samples, these findings are important because both repetitive head trauma (ie, subconcussive impacts) and recurrent concussions may be associated with the later development of mental health concerns and chronic brain disease.11−17 In the present study, we used data from the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) Injury Surveillance Program (ISP) to describe the epidemiology of HFN injuries in collegiate men's and women's ice hockey players during the 2009−2010 through 2013−2014 academic years. This study builds on previous research by Agel and Harvey,9 who described ice hockey injuries among NCAA players from 1988−1989 through 2003−2004, by providing more recent data as well as more closely examining injuries to a specific anatomical region. A better understanding of these injuries sustained during collegiate ice hockey will inform the development of interventions to prevent such injuries.

METHODS

All data were obtained from the NCAA-ISP during the 2009−2010 through 2013−2014 academic years. Fifty-seven men's and 26 women's collegiate ice hockey programs from all NCAA divisions provided 106 and 51 team-seasons of data, respectively. A team-season is defined as 1 program's participation in 1 season. In total, there were 682 and 436 total team-seasons during the 2009−2010 through 2013−2014 academic years, respectively, in men's and women's ice hockey18; thus, our sample represents 15.5% and 11.7% of all team-seasons in the NCAA during the study period. The methods of the NCAA-ISP have been previously described in depth but are summarized below.19

Data Collection

The NCAA-ISP is composed of collegiate teams across all sports staffed by athletic trainers (ATs) who voluntarily report injury and exposure data. Only varsity-level practice and competition events were included in the ISP datasets. Junior varsity programs, as well as weightlifting and conditioning sessions, were excluded.

The ATs from participating teams reported injuries in real time via their electronic medical record applications throughout the academic year. Common data elements that included injury and exposure information were de-identified, recoded, and exported into a hockey-specific database for the present analysis. In addition to injuries, the ISP captured other sport-related adverse health events such as illnesses and skin infections. For each event, the AT completed a detailed event report on the injury or condition (eg, site, diagnosis, severity) and the circumstances (eg, activity, mechanism, event type [ie, competition or practice], playing surface). The ATs were able to view and update previously submitted information as needed during the course of a season. To provide athlete-exposure (AE) data, ATs also supplied the number of student-athletes participating in each practice and competition.

As data were exported, they passed through an automated verification process that conducted a series of range and consistency checks.19 Data were reviewed and invalid values were flagged. The automated verification process would notify the AT and data quality-control staff, who would assist the AT in resolving the problem.

Definitions

Injury.

A reportable injury occurred as a result of participation in an NCAA-sanctioned practice or competition and required attention from an AT or physician. We relied on the medical expertise of the team medical staff to appropriately identify specific diagnoses. However, in the case of concussion, ATs were encouraged to follow the definition provided by the Consensus Statement on Concussion in Sport.20

Athlete-Exposure.

A reportable AE was defined as 1 student-athlete participating in 1 NCAA-sanctioned practice or competition in which he or she was exposed to the possibility of athletic injury, regardless of the time associated with that participation. Only athletes with actual playing time in a competition were included in competition exposures.

Event Type.

Event type was the specific event (ie, practice, competition) in which the injury was reported to have occurred.

Injury Mechanism.

Injury mechanism was defined as the manner in which the student-athlete sustained the injury. In the NCAA-ISP, ATs selected from a preset list of options: player contact, surface contact, equipment contact, contact with out-of-bounds object, noncontact, overuse, illness, infection, and other/unknown. In ice hockey, equipment contact could be further defined as contact with the stick, skate, puck, boards, and goal.

Injury Activity.

Injury activity was defined as the specific action in which the student-athlete was engaged when he or she sustained the injury. Athletic trainers selected from a preset list of options: checking, defending, general play, and handling puck.

Participation-Restriction Time.

Injuries were categorized by the number of days of participation restriction (ie, date of injury subtracted from the date of return). Non–time-loss (NTL) injuries resulted in participation restriction of less than 24 hours. Time-loss (TL) injuries resulted in participation restriction of at least 24 hours; severe injuries21 were those TL injuries resulting in participation restriction of more than 3 weeks, the student-athlete choosing to prematurely end the season (for medical or nonmedical reasons associated with the injury), or a medical professional requiring the student-athlete to prematurely end the season.

Computing National Estimates

To calculate national estimates of the number of HFN injuries in ice hockey, poststratification sample weights, based on sport, division, and academic year, were applied to each reported injury and AE.19 Poststratification sample weights were calculated using the formula

where weightijk is the weight for the ith sport of the jth division in the kth year. Weights for all data were further adjusted to correct for underreporting, according to findings of Kucera et al,22 who estimated that the NCAA-ISP captured 88.3% of all TL medical-care injury events. Weighted counts were scaled up by a factor of (0.883)−1.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed to assess rates and distributions of HFN injuries sustained during collegiate men's and women's ice hockey. We calculated HFN injury rates overall and then specifically for practices and for competitions. Injury rates were calculated per 1000 AEs. Incidence rate ratios (IRRs) compared injury rates between men and women and between practices and competitions. We also examined injury rates and distributions of injuries by body part, injury mechanism, injury activity, and diagnosis. Injury proportion ratios (IPRs) compared injury distributions between men and women and between practices and competitions for body part, injury mechanism, injury activity, and diagnosis. All IRRs and IPRs with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) that did not include 1.00 were considered statistically significant. Data were analyzed using SAS Enterprise Guide software (version 5.2; SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Overall Frequencies, National Estimates, and Rates

We identified 496 and 131 HFN injuries in men's and women's ice hockey, respectively, in the NCAA-ISP (Table 1). These HFN injuries accounted for 18.3% and 17.3% of all injuries reported in men's and women's ice hockey, respectively. The majority of HFN injuries occurred in competitions (men: 80.6%; women: 67.2%). The 496 and 131 HFN injuries represent a national estimate of 3390 and 932 HFN injuries sustained over the past 5 years in men's and women's ice hockey players, respectively (Table 1). These numbers equate to approximately 678 and 186 HFN injuries annually, respectively.

Table 1. .

Counts, National Estimates, and Rates Per 1000 Athlete-Exposures (AEs) of Head/Face/Neck Injuries in National Collegiate Athletic Association Men's and Women's Ice Hockey, 2009−2010 Through 2013−2014 Academic Yearsa

| Event Type |

Count |

% of All Injuries Within Sport |

National Estimate of Head/Face/Neck Injuries |

Rate Per 1000 AEs (95% Confidence Interval) |

| Men's ice hockey | ||||

| Competition | 400 | 21.8 | 2745 | 5.86 (5.28, 6.43) |

| Practice | 96 | 11.0 | 645 | 0.45 (0.36, 0.54) |

| Overall | 496 | 18.3 | 3390 | 1.75 (1.60, 1.91) |

| Women's ice hockey | ||||

| Competition | 88 | 22.4 | 635 | 2.95 (2.33, 3.56) |

| Practice | 43 | 11.7 | 296 | 0.52 (0.36, 0.67) |

| Overall | 131 | 17.3 | 932b | 1.16 (0.96, 1.35) |

Data originated from the National Collegiate Athletic Association Injury Surveillance Program, 2009−2010 through 2013−2014 academic years.

For national estimates of data for women's ice hockey, the sum of competition and practice does not equal the overall total due to rounding error.

The HFN injury rates were 1.75 and 1.16/1000 AEs in men's and women's ice hockey, respectively. The HFN injury rate was higher in men than in women (IRR = 1.51; 95% CI = 1.25, 1.84). This finding was retained in our analysis of competitions (5.86 versus 2.95/1000 AEs; IRR = 1.99; 95% CI = 1.58, 2.50) but not practices (0.45 versus 0.52/1000 AEs; IRR = 0.87; 95% CI = 0.61, 1.24).

Participation-Restriction Time

Participation-restriction data were missing for small proportions of injuries in men's (competition: 2.5%; practice: 3.1%) and women's (competition: 2.3%; practice: 7.0%) ice hockey. Most HFN injuries in men's competition were NTL (53.8%); in contrast, most injuries in men's practices (62.5%), women's competitions (75.0%), and women's practices (62.8%) were TL. When considering only TL injuries, HFN injury rates were 2.56/1000 AEs in men's competitions, 0.28/1000 AEs in men's practices, 2.21/1000 AEs in women's competitions, and 0.32/1000 AEs in women's practices.

The proportion of HFN injuries in competitions that were NTL was higher in men than in women (IPR = 2.37; 95% CI = 1.59, 3.51). Also, the proportion of HFN injuries in men that were NTL was higher in competitions than in practices (IPR = 1.56; 95% CI = 1.17, 2.09).

The proportion of HFN injuries that were defined as severe was highest in men's practices (18.8%), followed by women's competitions (12.5%), men's competitions (10.5%), and women's practices (4.7%). The proportion of HFN injuries in men that were severe was higher during practices than during competitions (IPR = 1.79; 95% CI = 1.08, 2.96).

Body Part Injured

During practices and competitions in both men's and women's ice hockey, most HFN injuries occurred to the head/face, followed by the cervical spine/neck, and mouth (Table 2). The proportion of HFN injuries during practices that were sustained to the cervical spine/neck was higher in women than in men (25.6% versus 11.5%; IPR = 2.23; 95% CI = 1.05, 4.75).

Table 2. .

Body Parts Injured in Head/Face/Neck Injuries in National Collegiate Athletics Association Men's and Women's Ice Hockey Players, 2009−2010 Through 2013−2014 Academic Yearsa

| Body Part |

Practice Injuries |

Competition Injuries |

||||||

| No. (%) |

Rate per 1000 AEs (95% CI) |

% Severeb |

% NTLc |

No. (%) |

Rate per 1000 AEs (95% CI) |

% Severeb |

% NTLc |

|

| Men's ice hockey | ||||||||

| Head/face | 73 (76.0) | 0.34 (0.26, 0.42) | 23.3 | 23.3 | 322 (80.5) | 4.71 (4.20, 5.23) | 12.1 | 48.1 |

| Cervical spine/neck | 11 (11.5) | 0.05 (0.02, 0.08) | 9.1 | 45.5 | 47 (11.8) | 0.69 (0.49, 0.88) | 2.1 | 72.3 |

| Mouth | 7 (7.3) | 0.03 (0.01, 0.06) | 0.0 | 100.0 | 19 (4.8) | 0.28 (0.15, 0.40) | 10.5 | 79.0 |

| Nose | 1 (1.0) | 7 (1.8) | 0.10 (0.03, 0.18) | 0.0 | 85.7 | |||

| Ear | 4 (4.2) | 5 (1.3) | 0.07 (0.01, 0.14) | 0.0 | 100.0 | |||

| Eye | 0 | 0 | ||||||

| Women's ice hockey | ||||||||

| Head/face | 26 (60.5) | 0.31 (0.19, 0.43) | 7.7 | 3.9 | 69 (78.4) | 2.31 (1.77, 2.86) | 15.9 | 14.5 |

| Cervical spine/neck | 11 (25.6) | 0.13 (0.05, 0.21) | 0.0 | 54.6 | 16 (18.2) | 0.54 (0.27, 0.80) | 0.0 | 43.8 |

| Mouth | 3 (7.0) | 3 (3.4) | ||||||

| Nose | 1 (2.3) | 0 | ||||||

| Ear | 1 (2.3) | 0 | ||||||

| Eye | 1 (2.3) | 0 | ||||||

Abbreviations: AE, athlete-exposure; CI, confidence interval; NTL, non-time loss.

Note: Rates, % severe, and % NTL injuries were not calculated for injuries with counts <5.

Severe injuries defined as those resulting in participation restriction of more than 3 weeks or a premature end to the season.

NTL injuries defined as those resulting in participation restriction of less than 24 hours.

Injury Mechanism

During practices and competitions in both men's and women's ice hockey, most HFN injuries were due to player contact (Table 3). The proportion of HFN injuries that were due to player contact was higher in women than in men during competitions (75.3% versus 46.6%; IPR = 1.62; 95% CI = 1.25, 2.03) and practices (52.1% versus 27.9%; IPR = 1.87; 95% CI = 1.11, 3.13). Although the proportion of HFN injuries that were due to player contact was higher during competitions than during practices in men (75.3% versus 52.1%; IPR = 1.44; 95% CI = 1.18, 1.76), this was not the case for women (46.6% versus 27.9%; IPR = 1.67; 95% CI = 0.98, 2.84).

Table 3. .

Injury Mechanisms of Head/Face/Neck Injuries in National Collegiate Athletics Association Men's and Women's Ice Hockey Players, 2009−2010 Through 2013−2014 Academic Yearsa

| Injury Mechanism |

Practice Injuries |

Competition Injuries |

||||||

| No. (%) |

Rate per 1000 AEs (95% CI) |

% Severeb |

% NTLc |

No. (%) |

Rate per 1000 AEs (95% CI) |

% Severeb |

% NTLc |

|

| Men's ice hockey | ||||||||

| Player contact | 50 (52.1) | 0.23 (0.17, 0.30) | 22.0 | 26.0 | 301 (75.3) | 4.41 (3.91, 4.90) | 11.3 | 53.8 |

| Surface contact | 7 (7.3) | 0.03 (0.01, 0.06) | 28.6 | 14.3 | 24 (6.0) | 0.35 (0.21, 0.49) | 0.0 | 37.5 |

| Stick contact | 7 (7.3) | 0.03 (0.01, 0.06) | 0.0 | 100.0 | 17 (4.3) | 0.25 (0.13, 0.37) | 0.0 | 82.4 |

| Puck contact | 11 (11.5) | 0.05 (0.02, 0.08) | 0.0 | 54.5 | 9 (2.3) | 0.13 (0.05, 0.22) | 11.1 | 77.8 |

| Boards contact | 8 (8.3) | 0.04 (0.01, 0.06) | 25.0 | 12.5 | 31 (7.8) | 0.45 (0.29, 0.61) | 12.9 | 32.3 |

| Goal contact | 2 (2.1) | 0 | ||||||

| Other equipment contact | 0 | 5 (1.3) | 0.07 (0.01, 0.14) | 0.0 | 100.0 | |||

| Out-of-bound object contact | 0 | 3 (0.8) | ||||||

| Non-contact | 2 (2.1) | 0 | ||||||

| Overuse | 0 | 0 | ||||||

| Illness/infection | 0 | 1 (0.3) | ||||||

| Unknown | 9 (9.4) | 0.04 (0.01, 0.07) | 33.3 | 22.2 | 9 (2.3) | 0.13 (0.05, 0.22) | 22.2 | 66.7 |

| Women's ice hockey | ||||||||

| Player contact | 12 (27.9) | 0.14 (0.06, 0.23) | 8.3 | 25.0 | 41 (46.6) | 1.37 (0.95, 1.79) | 14.6 | 12.2 |

| Surface contact | 9 (20.9) | 0.11 (0.04, 0.18) | 11.1 | 0.0 | 18 (20.5) | 0.60 (0.32, 0.88) | 16.7 | 22.2 |

| Stick contact | 1 (2.3) | 8 (9.1) | 0.27 (0.08, 0.45) | 0.0 | 75.0 | |||

| Puck contact | 6 (14.0) | 0.07 (0.01, 0.13) | 0.0 | 16.7 | 0 | |||

| Boards contact | 2 (4.7) | 7 (8.0) | 0.23 (0.06, 0.41) | 14.3 | 14.3 | |||

| Goal contact | 0 | 4 (4.5) | ||||||

| Other equipment contact | 1 (2.3) | 0 | ||||||

| Out-of-bound object contact | 2 (4.7) | 5 (5.7) | 0.17 (0.02, 0.31) | 0.0 | 40.0 | |||

| Non-contact | 4 (9.3) | 0 | ||||||

| Overuse | 1 (2.3) | 0 | ||||||

| Illness/Infection | 2 (4.7) | 0 | ||||||

| Unknown | 3 (7.0) | 5 (5.7) | 0.17 (0.02, 0.31) | 20.0 | 20.0 | |||

Abbreviations: AE, athlete-exposure; CI, confidence interval; NTL, non-time loss.

Note: Rates, % severe, % NTL injuries were not calculated for injuries with counts <5.

Severe injuries defined as those resulting in participation restriction of more than 3 weeks or a premature end to the season.

NTL injuries defined as those resulting in participation restriction of less than 24 hours.

Equipment contact (eg, contact with the stick, puck, boards) accounted for large proportions of HFN injuries. The proportion of HFN injuries in men that were due to equipment contact was higher in practices than in competitions (39.6% versus 15.5%; IPR = 2.55; 95% CI = 1.82, 3.58). In addition, surface contact comprised larger proportions of HFN injuries in women than men in competitions (20.5% versus 6.0%; IPR = 3.41; 95% CI = 1.94, 6.00) and practices (20.9% versus 7.3%; IPR = 2.87; 95% CI = 1.14, 7.20).

Injury Activity

Within competitions and practices in both men's and women's ice hockey, most HFN injuries occurred during general play and checking (Table 4). The proportion of HFN injuries that occurred during checking was higher in men than in women during competitions (38.5% versus 13.6%; IPR = 2.82; 95% CI = 1.64, 4.85) and practices (21.9% versus 2.3%; IPR = 9.41; 95% CI = 1.31, 67.69). The proportion of HFN injuries that occurred during checking was higher during competitions than during practices in men (38.5% versus 21.9%; IPR = 1.76; 95% CI = 1.18, 2.62) but not in women (13.6% versus 2.3%; IPR = 5.86; 95% CI = 0.79, 43.64).

Table 4. .

Injury Activities of Head/Face/Neck Injuries in National Collegiate Athletics Association Men's and Women's Ice Hockey Players, 2009−2010 Through 2013−2014 Academic Yearsa

| Injury Activity |

Practice Injuries |

Competition Injuries |

||||||

| No. (%) |

Rate per 1000 AEs (95% CI) |

% Severeb |

% NTLc |

No. (%) |

Rate per 1000 AEs (95% CI) |

% Severeb |

% NTLc |

|

| Men's ice hockey | ||||||||

| Blocking shot | 5 (5.2) | 0.02 (0.00, 0.04) | 0.0 | 40.0 | 5 (1.3) | 0.07 (0.01, 0.14) | 0.0 | 80.0 |

| Checking | 21 (21.9) | 0.10 (0.06, 0.14) | 19.0 | 33.3 | 154 (38.5) | 2.25 (1.90, 2.61) | 5.2 | 65.6 |

| Conditioning | 2 (2.1) | 1 (0.3) | ||||||

| Defending | 7 (7.3) | 0.03 (0.01, 0.06) | 28.6 | 42.9 | 29 (7.3) | 0.42 (0.27, 0.58) | 10.3 | 55.2 |

| General play | 36 (37.5) | 0.17 (0.11, 0.22) | 22.2 | 27.8 | 105 (26.3) | 1.54 (1.24, 1.83) | 11.4 | 45.7 |

| Goaltending | 4 (4.2) | 0 | ||||||

| Handling puck | 7 (7.3) | 0.03 (0.01, 0.06) | 14.3 | 28.6 | 50 (12.5) | 0.73 (0.53, 0.93) | 14.0 | 46.0 |

| Passing | 0 | 13 (3.3) | 0.19 (0.09, 0.29) | 46.2 | 23.1 | |||

| Receiving pass | 4 (4.2) | 10 (2.5) | 0.15 (0.06, 0.24) | 30.0 | 30.0 | |||

| Shooting | 0 | 9 (2.3) | 0.13 (0.05, 0.22) | 0.0 | 33.3 | |||

| Unknown | 10 (10.4) | 0.05 (0.02, 0.08) | 10.0 | 50.0 | 24 (6.0) | 0.35 (0.21, 0.49) | 12.5 | 54.2 |

| Women's ice hockey | ||||||||

| Blocking shot | 0 | 0 | ||||||

| Checking | 1 (2.3) | 12 (13.6) | 0.40 (0.17, 0.63) | 16.7 | 25.0 | |||

| Conditioning | 2 (4.7) | 1 (1.1) | ||||||

| Defending | 5 (11.6) | 0.06 (0.01, 0.11) | 0.0 | 20.0 | 18 (20.5) | 0.60 (0.32, 0.88) | 5.6 | 22.2 |

| General play | 20 (46.5) | 0.24 (0.13, 0.34) | 10.0 | 25.0 | 39 (44.3) | 1.31 (0.90, 1.72) | 17.9 | 17.9 |

| Goaltending | 5 (11.6) | 0.06 (0.01, 0.11) | 0.0 | 0.0 | 5 (5.7) | 0.17 (0.02, 0.31) | 0.0 | 20.0 |

| Handling puck | 1 (2.3) | 4 (4.5) | 25.0 | 0.0 | ||||

| Passing | 0 | 0 | ||||||

| Receiving pass | 1 (2.3) | 1 (1.1) | 0.0 | |||||

| Shooting | 1 (2.3) | 1 (1.1) | 0.0 | |||||

| Unknown | 7 (16.3) | 0.08 (0.02, 0.15) | 0.0 | 71.4 | 7 (8.0) | 0.23 (0.06, 0.41) | 0.0 | 57.1 |

Abbreviations: AE, athlete-exposure; CI, confidence interval; NTL, non-time loss.

Note: Rates, % severe, % NTL injuries were not calculated for injuries with counts <5.

Severe injuries defined as those resulting in participation restriction of more than 3 weeks or a premature end to the season.

NTL injuries defined as those resulting in participation restriction of less than 24 hours.

For women, defending contributed to a large proportion of HFN injuries. The proportion of HFN injuries that occurred while defending was higher in women than in men during competitions (20.5% versus 7.3%; IPR = 2.82; 95% CI = 1.64, 4.85) but not practices (11.6% versus 7.3%; IPR = 1.59; 95% CI = 0.54, 4.74).

Injury Diagnosis

Concussions.

Within competitions and practices in both men's and women's ice hockey, the most common HFN injuries were concussions (Table 5). The proportion of HFN injuries in competitions that were concussions was higher in women than in men (68.2% versus 42.5%; IPR = 1.60; 95% CI = 1.34, 1.93). Also, the proportion of HFN injuries in men that were concussions was higher during practices than during competitions (56.3% versus 42.5%; IPR = 1.32; 95% CI = 1.07, 1.63). It is interesting that 16 concussions in men's competitions (9.4%) were NTL; this contrasts with the lower counts seen in men's practices (n = 1), women's competitions (n = 2), and women's practices (n = 1).

Table 5. .

Diagnoses of Head/Face/Neck Injuries in National Collegiate Athletics Association Men's and Women's Ice Hockey Players, 2009−2010 Through 2013−2014 Academic Yearsa

| Diagnosis |

Practice Injuries |

Competition Injuries |

||||||

| No. (%) |

Rate per 1000 AEs (95% CI) |

% Severeb |

% NTLc |

No. (%) |

Rate per 1000 AEs (95% CI) |

% Severeb |

% NTLc |

|

| Men's ice hockey | ||||||||

| Concussion | 54 (56.3) | 0.25 (0.18, 0.32) | 31.5 | 1.9 | 170 (42.5) | 2.49 (2.11, 2.86) | 20.6 | 9.4 |

| Contusion | 4 (4.2) | 18 (4.5) | 0.26 (0.14, 0.39) | 0.0 | 94.4 | |||

| Dental injury | 4 (4.2) | 7 (1.8) | 0.10 (0.03, 0.18) | 0.0 | 100.0 | |||

| Fracture | 1 (1.0) | 8 (2.0) | 0.12 (0.04, 0.20) | 50.0 | 37.5 | |||

| Laceration | 20 (20.8) | 0.09 (0.05, 0.13) | 0.0 | 80.0 | 146 (36.5) | 2.14 (1.79, 2.48) | 2.1 | 93.2 |

| Spasm | 0 | 8 (2.0) | 0.12 (0.04, 0.20) | 0.0 | 100.0 | |||

| Strain | 5 (5.2) | 0.02 (0.00, 0.04) | 0.0 | 20.0 | 21 (5.3) | 0.31 (0.18, 0.44) | 0.0 | 61.9 |

| Other | 8 (8.3) | 0.04 (0.01, 0.06) | 0.0 | 87.5 | 22 (5.5) | 0.32 (0.19, 0.46) | 0.0 | 68.2 |

| Women's ice hockey | ||||||||

| Concussion | 25 (58.1) | 0.30 (0.18, 0.42) | 8.0 | 4.0 | 60 (68.2) | 2.01 (1.50, 2.52) | 18.3 | 3.3 |

| Contusion | 3 (7.0) | 13 (14.8) | 0.44 (0.20, 0.67) | 0.0 | 84.6 | |||

| Dental injury | 0 | 1 (1.1) | ||||||

| Fracture | 0 | 0 | ||||||

| Laceration | 0 | 0 | ||||||

| Spasm | 3 (7.0) | 0 | ||||||

| Strain | 5 (11.6) | 0.06 (0.01, 0.11) | 0.0 | 60.0 | 8 (9.1) | 0.27 (0.08, 0.45) | 0.0 | 25.0 |

| Other | 7 (16.3) | 0.08 (0.02, 0.15) | 0.0 | 85.7 | 6 (6.8) | 0.20 (0.04, 0.36) | 0.0 | 66.7 |

Abbreviations: AE, athlete-exposure; CI, confidence interval; NTL, non-time loss.

Note: Rates, % severe, % NTL injuries were not calculated for injuries with counts <5.

Severe injuries defined as those resulting in participation restriction of more than 3 weeks or a premature end to the season.

NTL injuries defined as those resulting in participation restriction of less than 24 hours.

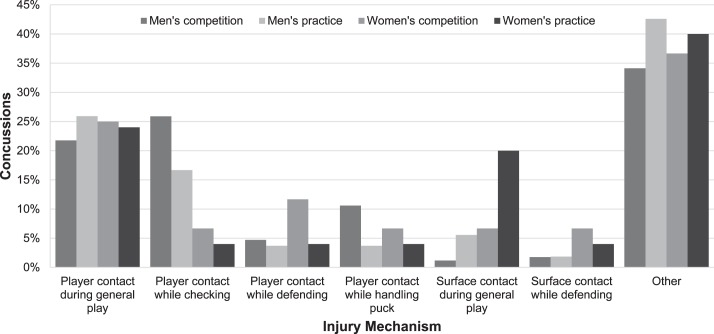

Most concussions in men's competitions were due to player contact while checking (25.9%), followed by player contact during general play (21.8%; Figure 1). Player contact during general play was responsible for the largest proportion of concussions in men's practices (25.9%), women's competitions (25.0%), and women's practices (24.0%). In addition, surface contact during general play also composed a large proportion of concussions in women's practices (20.0%).

Figure 1. .

Common injury mechanisms and activity pairings associated with concussions in National Collegiate Athletic Association men's and women's ice hockey, 2009−2010 through 2013−2014 academic years.

Lacerations.

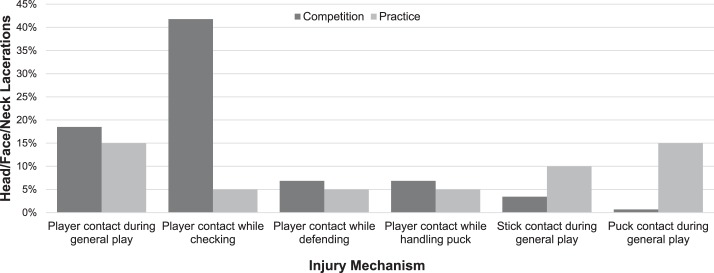

Although lacerations were the second most common diagnosis for male hockey players (IRR = 2.14/1000 AEs), zero lacerations were recorded for women over the study period. Lacerations accounted for 36.5% and 20.8% of HFN injuries in men's ice hockey competitions and practices, respectively (Table 5), almost all of which were NTL (competitions: 93.2%; practices: 80.0%). The proportion of HFN injuries in men that were lacerations was higher during competitions than during practices (IPR = 1.75; 95% CI = 1.16, 2.64). Most lacerations in men's competitions were due to player contact during checking (41.8%) and player contact during general play (18.5%; Figure 2). Most lacerations in men's practices were due to player contact during general play (15.0%) and puck contact during general play (15.0%).

Figure 2. .

Common injury mechanisms and activity pairings associated with lacerations in National Collegiate Athletic Association men's ice hockey, 2009−2010 through 2013−2014 academic years.

DISCUSSION

This study builds on previous injury-surveillance research of NCAA hockey players by Agel and Harvey9 and Agel et al.23,24 Although earlier authors focused on concussions specifically, we investigated all HNF injuries reported in the NCAA-ISP, thereby situating concussions in the broader context of these injuries. Unlike previous investigations of NCAA hockey players,9,23,24 our data included NTL injuries, which presents a more complete understanding of HFN injuries among NCAA ice hockey players.

Ice hockey injury data from the 1988−1989 through 2003−2004 academic years22,23 were collected via a previous iteration of the NCAA-ISP.25 Using information from these publications (ie, overall injury rates and the proportion of injuries that were to the HFN), we can estimate the HFN injury rates for that study period. Compared with the HFN injury rates from the 1988−1989 through 2003−2004 academic years, the rates for the current study period (ie, 2009−2010 through 2013−2014) were similar in men's competitions (2.56 versus 2.51/1000 AEs), lower in men's practices (0.20 versus 0.28/1000 AEs), and higher in women's competitions (3.20 versus 2.21/1000 AEs) and practices (0.41 versus 0.32/1000 AEs). Differences may be due to variations in data collection19 and samples during the study periods. Because both studies collected limited data on individual- and team-level characteristics, such as gameplay tactics or practice drills used, we are unable to pinpoint specifics that may explain potential changes across time. Thus, future research is recommended to examine the associations between HFN injuries and such factors.

We found that HFN injury rates were higher in competitions than in practices for both men and women, which is consistent with previous literature9,23,24 on collegiate ice hockey injuries. The intensity of gameplay may be higher in competitions versus practices.7,23 In addition, because practices are controlled environments in which teams develop overall skills and prepare for future competitions, many injuries in competition may originate from unanticipated impacts, which have been measured as having greater linear acceleration than anticipated contact.26 The NCAA-ISP was unable to account for such impacts or variations in the intensity levels during competitions and practices; further research to directly measure whether hits are anticipated would help to better explain variations in injury rates by event types.

Although competition HFN injury rates were higher for men than for women, practice rates did not differ. The fact that checking is legal in men's ice hockey and not in women's ice hockey may contribute to such a difference in competition rates, particularly because player contact and checking contributed to large proportions of HFN injuries among men. The controlled environments of practices may deter checking within men's ice hockey and thus create similar injury risks for men and women. Previous researchers9,25 have also found mixed results related to sex differences in collegiate ice hockey injury rates. Such variations may be attributable to differences in factors such as the athlete and team samples studied or the study period. Consequently, future investigators should determine the specific settings in which sex differences in ice hockey injury incidence exist.

Concussions were the most common HFN injury for both men and women in collegiate ice hockey. This finding is consistent with earlier data23,24 showing that concussions were one of the most common injuries for male collegiate ice hockey players overall and the most common injury for their female counterparts. However, a greater proportion of HFN injuries were diagnosed as concussions in women than in men during competitions. This is in part because women had fewer types of HFN injuries overall, leading to concussions making up a greater proportion. However, biological and social factors may also contribute to this finding. Among collegiate athletes, females have a decreased head-neck segment mass with less girth and strength than males.27 Women may also be more likely to report concussions, which may account for the higher reported rate.28−30 Unfortunately, such factors were not examined in the NCAA-ISP.

It is a concern that a number of concussions, particularly in men's ice hockey competitions, were NTL (ie, participation restriction time <24 hours). According to the most recent consensus statement on concussion in sport20 and the 2010 NCAA concussion guidelines,31 concussed athletes should not return to play on the same day as the injury, as this may result in the delayed onset of worse symptoms. However, the data may be the result of student-athletes presenting with delayed sport-related concussion symptoms; the symptoms may have also been initially attributed to other ailments (eg, headache caused by dehydration), with further examination after the competition or practice suggesting a concussion diagnosis. Additional research is needed to continue examining ways to ensure appropriate management of concussions as athletes return to participation in sports. Although ATs are well educated in concussion identification and management, continued research and education would improve their skillsets. At the same time, more research is also needed to determine the long-term effects of these head injuries among ice hockey players. Repeated blows to the head can cause long-term brain damage.17 It is unknown if these subconcussive impacts among collegiate hockey players occur with enough frequency to have the same potential for long-term effects.

Lacerations were a common diagnosis among male hockey players; however, none were reported in women during the study period. Previous research9,23,24 involving NCAA-ISP data did not demonstrate a significant number of laceration injuries, most likely because these authors did not record NTL injuries. This finding is unique to our study. Additional surveillance is required to better gauge the validity of this sex difference. Anecdotal evidence has indicated that facial lacerations may occur when the facemask has not been properly secured and a player is struck or from the blunt force trauma of a hit. Further investigation could determine how helmet and facemask use and misuse contribute to lacerations in hockey players and why men are disproportionately affected. Modifications to rules regarding facemasks and mouth guards have reduced facial injuries in youth hockey players.32

Because the differences between men's and women's player contact and checking rules offer a possible explanation for some of these results, further examination of rules regarding legal and illegal contact is warranted. Checking is an inherent part of men's ice hockey, so banning such contact would potentially be met with backlash from the ice hockey community.33 At the same time, it should be noted that the practice rates for HFN injuries in our study appear low, especially compared with concussion rates for many other high contact and collision sports, such as football, soccer, and wrestling.2,34 Thus, reductions in HFN injury risk related to player contact may best occur within competitions through closer regulation of in-game contact.

One potential approach to mitigating the risk of HFN injuries is to modify the environments surrounding in-game collisions.35,36 For instance, a larger ice surface may reduce player contact,37 although such a change may require substantial resources to enact universally, limiting its feasibility. Rule changes driven by evidence-based findings may be a more feasible intervention to reduce HFN injuries. For example, Mihalik et al26 demonstrated that, among youth players, collisions on open ice result in a greater acceleration of the head than collisions with the boards. Although further study is needed to determine if these findings also exist among collegiate players, changing the rules to ban open-ice checking may help to reduce HFN injuries. In a meta-analysis of interventions to reduce injuries in youth players, another group38 found that banning checking reduced injuries among players. Although changing the rules to ban checking in men's ice hockey might not be culturally acceptable, another avenue for reducing dangerous hits may be for referees and linesmen to more strictly enforce harsh penalties on hits that violate the current rules. Such a change may mitigate any incentive for players to use a dangerous check and potentially cause a concussion or any other HFN injury. However, we did not examine whether injuries were associated with illegal hits, which highlights the need for more research on this topic. Further work is also needed to determine the feasibility of such an intervention. Continued surveillance will also help to identify trends in HFN injuries that could highlight additional areas in which rule changes may help to mitigate the injury risk.

LIMITATIONS

The NCAA-ISP uses a convenience sample of ice hockey programs that provide injury and exposure data. Thus, findings may not be generalizable to programs that did not participate or do not exist in other sports settings (eg, junior colleges, high school, recreational leagues). If players did not seek medical attention after an injury or they sought diagnosis or treatment from another medical professional, their AT would not have recorded the injury in the NCAA-ISP. Finally, because injury-surveillance systems such as the NCAA-ISP rely on multiple data collectors,19 reporting variations among the ATs collecting injury and exposure data may exist. However, this concern is minimized by working with the electronic medical record applications, which are used by ATs in their daily clinical practice, to obtain de-identified data. Also, ATs are clinical professionals trained to work alongside other team medical staff to accurately identify and report injuries. Furthermore, the Datalys Center provides initial training and ongoing support to help ensure complete data are provided to the NCAA-ISP.19 Nevertheless, given that variations in reporting have been found at the high school level for football,39 it is essential to continue exploring the validity and reliability of data collected by injury-surveillance systems. Although previous researchers22 have found good validity for data from the previous iteration of the NCAA-ISP for women's soccer, additional examinations that consider NTL injury data and the updated methods are warranted.

CONCLUSIONS

The rates of HFN injuries in ice hockey players were higher among men and during competitions. Concussions were the most common HFN injuries across both sexes and event types, and lacerations were reported only among men. For both men and women, the most common mechanism of HFN injuries was player contact; however, checking accounted for a much larger proportion of HFN injuries. Safety initiatives and prevention programs should aim to reduce checking-related injuries.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The NCAA-ISP data were provided by the Datalys Center for Sports Injury Research and Prevention, Inc. The ISP was funded by the NCAA. The content of this manuscript is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NCAA. We thank the many ATs who have volunteered their time and efforts to submit data to the NCAA-ISP. Their efforts are greatly appreciated and have had a tremendously positive effect on the safety of collegiate athletes.

REFERENCES

- 1. Langlois JA, Rutland-Brown W, Wald MM. . The epidemiology and impact of traumatic brain injury: a brief overview. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2006; 21 5: 375– 378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Zuckerman SL, Kerr ZY, Yengo-Kahn A, Wasserman E, Covassin T, Solomon GS. . Epidemiology of sports-related concussion in NCAA athletes from 2009−2010 to 2013−2014: incidence, recurrence, and mechanisms. Am J Sports Med. 2015; 43 11: 2654– 2662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Marar M, McIlvain NM, Fields SK, Comstock RD. . Epidemiology of concussions among United States high school athletes in 20 sports. Am J Sports Med. 2012; 40 4: 747– 755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wasserman EB, Kerr ZY, Zuckerman SL, Covassin T. . Epidemiology of sports-related concussions in National Collegiate Athletic Association athletes from 2009−2010 to 2013−2014: symptom prevalence, symptom resolution time, and return-to-play time. Am J Sports Med. 2016; 44 1: 226– 233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Stuart MJ, Smith A. . Injuries in Junior A ice hockey: a three-year prospective study. Am J Sports Med. 1995; 23 4: 458– 461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wilcox BJ, Beckwith JG, Greenwald RM, et al. . Head impact exposure in male and female collegiate ice hockey players. J Biomech. 2014; 47 1: 109– 114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hootman JM, Dick R, Agel J. . Epidemiology of collegiate injuries for 15 sports: summary and recommendations for injury prevention initiatives. J Athl Train. 2007; 42 2: 311– 319. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Brainard LL, Beckwith JG, Chu JJ, et al. . Gender differences in head impacts sustained by collegiate ice hockey players. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2012; 44 2: 297– 304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Agel J, Harvey EJ. A. 7-year review of men's and women's ice hockey injuries in the NCAA. Can J Surg. 2010; 53 5: 319– 323. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Emery C, Kang J, Shrier I, et al. . Risk of injury associated with bodychecking experience among youth hockey players. CMAJ. 2011; 183 11: 1249– 1256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chamard E, Théoret H, Skopelja EN, Forwell LA, Johnson AM, Echlin PS. . A prospective study of physician-observed concussion during a varsity university hockey season: metabolic changes in ice hockey players. Part 4 of 4. Neurosurg Focus. 2012; 33 6: E4: 1− 7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Guskiewicz KM, McCrea M, Marshall SW, et al. . Cumulative effects associated with recurrent concussion in collegiate football players: the NCAA Concussion Study. JAMA. 2003; 290 19: 2549– 2555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Guskiewicz KM, Weaver NL, Padua DA, Garrett WE Jr.. Epidemiology of concussion in collegiate and high school football players. Am J Sports Med. 2000; 28 5: 643– 650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kerr ZY, Marshall SW, Harding HP Jr Guskiewicz KM. . Nine-year risk of depression diagnosis increases with increasing self-reported concussions in retired professional football players. Am J Sports Med. 2012; 40 10: 2206– 2212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Stern RA, Riley DO, Daneshvar DH, Nowinski CJ, Cantu RC, McKee AC. . Long-term consequences of repetitive brain trauma: chronic traumatic encephalopathy. PM R. 2011; 3 10 suppl 2: S460– S467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Iverson GL, Gaetz M, Lovell MR, Collins MW. . Cumulative effects of concussion in amateur athletes. Brain Inj. 2004; 18 5: 433– 443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bailes JE, Petraglia AL, Omalu BI, Nauman E, Talavage T. . Role of subconcussion in repetitive mild traumatic brain injury. J Neurosurg. 2013; 119 5: 1235– 1245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Irick E. . NCAA Sports Sponsorship And Participation Rates Report: 1981−82 to 2013−14. Indianapolis, IN: National Collegiate Athletics Association; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kerr ZY, Dompier TP, Snook EM, et al. . National Collegiate Athletic Association injury surveillance system: review of methods for 2004−2005 through 2013−2014 data collection. J Athl Train. 2014; 49 4: 552– 560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. McCrory P, Meeuwisse WH, Aubry M, et al. . Consensus statement on concussion in sport: the 4th International Conference on Concussion in Sport held in Zurich, November 2012. Br J Sports Med. 2013; 47 5: 250– 258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Darrow CJ, Collins CL, Yard EE, Comstock RD. . Epidemiology of severe injuries among United States high school athletes: 2005−2007. Am J Sports Med. 2009; 37 9: 1798– 1805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kucera KL, Marshall SW, Bell DR, DiStefano MJ, Goerger CP, Oyama S. . Validity of soccer injury data from the National Collegiate Athletic Association's Injury Surveillance System. J Athl Train. 2011; 46 5: 489– 499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Agel J, Dompier TP, Dick R, Marshall SW. . Descriptive epidemiology of collegiate men's ice hockey injuries: National Collegiate Athletic Association Injury Surveillance System, 1988−1989 through 2003−2004. J Athl Train. 2007; 42 2: 241– 248. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Agel J, Dick R, Nelson B, Marshall SW, Dompier TP. . Descriptive epidemiology of collegiate women's ice hockey injuries: National Collegiate Athletic Association Injury Surveillance System, 2000−2001 through 2003−2004. J Athl Train. 2007; 42 2: 249– 254. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Dick R, Agel J, Marshall SW. . National Collegiate Athletic Association Injury Surveillance System commentaries: introduction and methods. J Athl Train. 2007; 42 2: 173– 182. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Mihalik JP, Blackburn JT, Greenwald RM, Cantu RC, Marshall SW, Guskiewicz KM. . Collision type and player anticipation affect head impact severity among youth ice hockey players. Pediatrics. 2010; 125 6: E1394– E1401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Tierney RT, Sitler MR, Swanik CB, Swanik KA, Higgins M, Torg J. . Gender differences in head-neck segment dynamic stabilization during head acceleration. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2005; 37 2: 272– 279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Broshek DK, Kaushik T, Freeman JR, Erlanger D, Webbe F, Barth JT. . Sex differences in outcome following sports-related concussion. J Neurosurg. 2005; 102 5: 856– 863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Llewellyn T, Burdette GT, Joyner AB, Buckley TA. . Concussion reporting rates at the conclusion of an intercollegiate athletic career. Clin J Sport Med. 2014; 24 1: 76– 79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kerr ZY, Register-Mihalik JK, Marshall SW, Evenson KR, Mihalik JP, Guskiewicz KM. . Disclosure and non-disclosure of concussion and concussion symptoms in athletes: review and application of the socio-ecological framework. Brain Inj. 2014; 28 8: 1009– 1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Concussion diagnosis and management best practices: diagnosis and management of sport-related concussion guidelines. National Collegiate Athletic Association Web site. http://www.ncaa.org/health-and-safety/concussion-guidelines. Accessed February 20, 2017.

- 32. Murray TM, Livingston LA. . Hockey helmets, face masks, and injurious behavior. Pediatrics. 1995; 95 3: 419– 421. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Theberge N. . It's part of the game: physicality and the production of gender in women's hockey. Gender Soc. 1997; 11 1: 69– 87. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kerr ZY, Marshall SW, Dompier TP, Corlette J, Klossner DA, Gilchrist J. . College sports-related injuries—United States, 2009−10 through 2013−14 academic years. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015; 64 48: 1330– 1336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Runyan CW. . Using the Haddon matrix: introducing the third dimension. Inj Prev. 2015; 21 2: 126– 130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Haddon W., Jr. Options for the prevention of motor vehicle crash injury. Isr J Med Sci. 1980; 16 1: 45– 65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Wennberg R. . Effect of ice surface size on collision rates and head impacts at the World Junior Hockey Championships, 2002 to 2004. Clin J Sport Med. 2005; 15 2: 67– 72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Cusimano MD, Nastis S, Zuccaro L. . Effectiveness of interventions to reduce aggression and injuries among ice hockey players: a systematic review. CMAJ. 2013; 185 1: E57– E69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kerr ZY, Lynall RC, Mauntel TC, Dompier TP. . High school football injury rates and services by athletic trainer employment status. J Athl Train. 2016; 51 1: 70– 73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]