Abstract

The Juvenile Justice (JJ) system has a number of local behavioral health service community linkages for substance abuse, mental health, and HIV services. However, there have only been a few systemic studies that examine and seek to improve these community behavioral health linkages for justice-involved youth. Implementation research is a way of identifying, testing, and understanding effective strategies for translating evidence-based treatment and prevention approaches into service delivery. This article explores benefits and challenges of participatory research within the context of the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA)’s Juvenile Justice Translational Research on Interventions for Adolescents in the Legal System (JJ-TRIALS) implementation behavioral health study. The JJ-TRIALS study has involved JJ partners (representatives from state-level JJ agencies) throughout the study development, design, and implementation. Proponents of participatory research argue that such participation strengthens relations between the community and academia; ensures the relevancy of research questions; increases the capacity of data collection; and enhances program recruitment, sustainability, and extension. The extent of the impact that JJ partners have had on the JJ-TRIALS study will be discussed, as well as the benefits local JJ agencies can derive from both short- and long-term participation. Issues associated with the site selection, participation, and implementation of evidence-based practices also will be discussed.

Keywords: organizational research, implementation research, behavioral health, evidence-based treatment, substance use

Introduction

The juvenile justice (JJ) system (i.e., police, court, juvenile probation, and institutional and community-based correctional services) has a number of community linkages with local behavioral health services. These linkages are critical, given the high prevalence of substance abuse, mental health problems, and HIV within the JJ system. Justice-involved youth report substance use at higher rates than their counterparts who are not justice involved. An estimated 78% of arrested juveniles have prior drug involvement (National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse [CASA], 2004). In comparison, national surveys of the general population indicate that approximately 9% to 38% of American youth report consuming alcohol in the past month; another 9.5% to 16.8% report using illicit drugs in the past month (Johnston, O’Malley, Bachman, & Schulenberg, 2013; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2013). Adolescent substance use is associated with a number of immediate negative consequences and is a risk factor for substance use disorder in both adolescence (Winters & Lee, 2008) and adulthood (Englund, Egeland, Olivia, & Collins, 2008; Stone, Becker, Huber, & Catalano, 2012; Swift, Coffey, Carlin, Degenhardt, & Patton, 2008). Substance use is also linked to a multitude of negative outcomes, including delinquency, psychopathology, social problems, risky sex and sexually transmitted infections (STIs), and health problems (Chan, Dennis, & Funk, 2008; Kandel et al., 1999; Wasserman, McReynolds, Schwalbe, Keating, & Shane, 2010). However, a large proportion of justice-involved youth do not access treatment services (Young, Dembo, & Henderson, 2007). The relatively few services are typically reserved for incarcerated offenders and are not available to justice-involved juveniles in community settings, such as those on probation or parole (Weiss, 2013).

Given the link between substance use problems and justice system involvement, it is important that the JJ system screen for substance use problems (Binard & Prichard, 2008). In an ideal system, this initial screening would lead to linkage to appropriate evidence-based assessments and community services. Many evidence-based interventions targeting adolescent substance abuse currently exist (e.g., Multidimensional Family Therapy; Liddle, Rowe, Dakof, Henderson, & Greenbaum, 2009; for more information see Leukefeld et al., 2015). Unfortunately, implementation of these interventions within the JJ system is variable, incomplete, and nonsystematic at best. However, there have been a few systematic studies that examine and seek to improve community behavioral-health linkages for justice-involved individuals with substance use problems (Friedmann et al., 2015; Welsh et al., 2016).

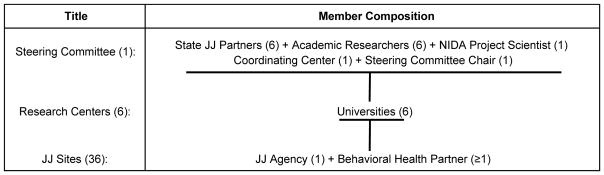

The National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) launched the Juvenile Justice Translational Research on Interventions for Adolescents in the Legal System (JJ-TRIALS) initiative in 2013 to target system-wide improvement in substance use services. JJ-TRIALS is a multisite cooperative agreement grant designed to improve the uptake of evidence-based strategies for addressing substance use among justice-involved youth. JJ-TRIALS includes academic partners from six university research centers, six state-level JJ partners, one coordinating center, and a NIDA project scientist. Table 1 lists the university research centers and state-level JJ partners who participated in JJ-TRIALS. Collectively, the academic partners, JJ partners, coordinating center, and NIDA project scientist formed the initiative’s Steering Committee, which was chaired by a senior justice researcher from a seventh university. The Steering Committee was tasked with developing large-scale projects designed to compare implementation strategies. The goal for these projects was to improve the delivery of evidence-based substance abuse and HIV prevention and treatment services for justice-involved youth. For the first 6 months of the cooperative, the steering committee engaged in an intensive collaborative planning process to develop a plan to meet this directive. Throughout the process of designing these studies, the JJ partners were active participants in helping shape the research questions and overall design.

Table 1.

JJ-TRIALS Research Centers and Juvenile Justice Partners

| Research Center | State-Level JJ Partner Organization | JJ Partner & Steering Committee Member |

|---|---|---|

| Columbia University | NYS Division of Criminal Justice Services Office of Probation and Correctional Alternatives | Patti Donohue Community Corrections Representative, New York State Division of Criminal Justice Services, Office of Probation and Correctional Alternatives Juvenile Operations and Training Director |

| Emory University | Georgia Department of Juvenile Justice | Margaret Cawood, Assistant Deputy Commissioner Michelle Staples-Horne, Medical Director |

| Mississippi State University | Division of Youth Services, Mississippi Department of Human Services | James Maccarrone, Director Division of Youth Services |

| Texas Christian University | Texas Juvenile Justice Department | Nancy Arrigona, Research Manager, Council of State Government Justice Center Formerly the Director of Research and Planning (retired), Texas Juvenile Justice Department |

| Temple University | Florida Department of Juvenile Justice | Judy Roysden, Chief Probation Officer C-13 |

| University of Kentucky | Kentucky Department of Juvenile Justice | Veronica Koontz, Division of Placement Services, Classification Branch Manager |

One of three projects resulting from this collaborative planning effort was a 36-site randomized controlled trial to improve implementation of evidence-based practices around youth substance use. This JJ-TRIALS implementation study involved delivering a 7-month multicomponent training and technical assistance intervention to 36 sites, each with local change teams comprised of a JJ agency (primarily probation departments) and their behavioral health partners (see Figure 1). Three additional pilot sites participated in parts of the intervention as it was being developed, but they did not receive the full intervention and were not included in analyses. This training and technical assistance primarily focused on helping identify and select goals to reduce unmet needs for substance use treatment among the youth these agencies served. Half of these sites were then randomly selected to receive 1 year of external facilitation of the local change team tasked with pursuing their selected goals. At the time of this writing, data collection was ongoing. The overall design of the 36-site RCT is described in detail by Knight and colleagues (2016).

Figure 1.

JJ-TRIALS composition. Steering Committee oversees the six research centers. Each research centers oversees six JJ sites, each comprised of a JJ Agency and at least one Behavioral Health Partner.

The authors of this paper include four of the six JJ partners participating in JJ-TRIALS, two academic research partners who are members of the steering committee, the NIDA project scientist, and several academic partners who have been actively involved in establishing partnerships with participating JJ TRIALS sites. The purpose of this article is to share our collective reflections on the benefits and challenges of the participatory research framework that guided JJ-TRIALS in developing a rigorous implementation study and also in executing that study, which entailed new partnerships between JJ agencies and community treatment partners.

Implementation Research

To date, behavioral health research has focused on developing interventions to address public health concerns, such as mental health and substance use problems, and also, to some extent, the dissemination of evidence-based programs to real-world settings (Proctor et al., 2009). Despite this investment in identifying effective interventions, very little of this research is actually translated into practice and policy—or when it is, the deployment process often lacks systematization (Tabak, Khoong, Chambers, & Brownson, 2012).

Recently, there has been a shift in resources by behavioral health researchers, justice agencies, primary care facilities, and funders toward implementation research. Such research is a way of identifying, testing, and understanding effective strategies for translating treatment and prevention evidence-based approaches into service delivery. The systematic study of integrating evidence-based programs from controlled laboratory settings to real-world contexts (e.g., JJ agencies) has become recognized as an essential component to effective intervention design and dissemination (Peters, Adam, Alonge, Agyepong, & Tran, 2013). Even with this shift, however, calls persist for more efforts to “bridge the yawning gap between best evidence and common practice” (Bhattacharyya, Reeves, & Zwarenstein, 2009) to ensure that the most effective treatments are used, particularly with vulnerable populations.

Though numerous prior studies have sought to improve substance use services for justice-involved youth, to our knowledge, JJ-TRIALS is the largest effort to date to systematically test different implementation strategies for putting evidence-based practices into place in the JJ system. JJ-TRIALS builds on a similar effort funded by NIDA previously, which showed the promise of using local change teams and implementation strategies to improve HIV services and the use of medication-assisted treatment for opiate addiction in adult criminal justice settings (Friedmann et al., 2015; Pearson et al., 2014; Welsh et al., 2016). JJ-TRIALS is engaged in implementation research as a means of identifying, testing, and understanding effective strategies to translate evidence-based screening, referral, and linkage to treatment for substance-using youth under community supervision. Although the application of evidence-based programming within JJ treatment service-delivery agencies has been growing (Greenwood & Welsh, 2012), a more systematic study of implementation processes is essential for standardization of practices (Walker, Bumbarger, & Phillippi, 2015).

JJ-TRIALS as an Example of Participatory Research

The active collaborative approach of JJ-TRIALS is a form of participatory research, which is a strategy used in implementation research to increase the likelihood of sustained change through emphasis on collective action and input (Scott & Shore, 1979). The resulting convergence of perspectives—one focused on science, the other on practice—allows growth and understanding for both researchers and participants (Bergold & Thomas, 2012). Research has shown that participatory research also strengthens relations between organizational partners and academia and increases the capacity of data collection, analysis, and interpretation of findings to sustain program changes (Cashman et al., 2008; Israel, Schulz, Parker, & Becker, 1998). Our experiences are consistent with these findings.

JJ partners participated in all aspects of the JJ-TRIALS study design. As equal voting members of the JJ-TRIALS steering committee, JJ partners play an active role in determining the policies that govern the cooperative, developing and approving research protocols, ensuring that protocols comply with ethical guidelines and regulatory approval processes, monitoring the study protocol process, ensuring data quality, and reviewing study results before dissemination (see Figure 1). In addition to serving on the steering committee, JJ partners participate in study workgroups, advise on key design issues and study approaches, review and comment on study procedures and documents, assist in recruiting and in securing study sites, and co-author presentations and articles.

Examples of JJ Partner Influence on Study Design and Execution

Below are specific examples of ways JJ partners have actively influenced the overall study design and execution.

JJ Partner Influences on JJ-TRIALS Study Design

JJ-TRIALS was designed to be a rigorous implementation study, which required standardization across sites to the best extent possible (see Knight et al., 2016 for details). To standardize implementation at each site, a JJ-TRIALS structured training package was developed, which includes manuals, PowerPoint slides, practice exercises to reinforce didactic training, and tools for sites to use. Trainers were encouraged to tailor training to take into account local conditions. However, extensive efforts were made to ensure that the core training was delivered as consistently as possible and that site-level variations were documented and discussed routinely to ensure consistency across all 36 sites. The key activity of the JJ-TRIALS training for participating sites revolved around establishing a local change team and setting a measureable goal(s) that would reduce the unmet needs of the youth they served with regard to screening, assessment, and referral for substance use services.

JJ-TRIALS drew on the organizational change and strategic planning literature to develop a training system focused on using the SMART goal selection approach (i.e., Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant and Time-bound goals; Bovend’Eerdt, Botell, & Wade, 2009). Local change teams also received training on Data-Driven Decision-Making (DDDM; Schuyler Ikemoto & Marsh, 2007; Orwin, Edwards, Buchanan, Flewelling, & Landy, 2012); Continuous Quality Improvement (CQI) (Dean & Bowen, 1994); and the use of “Plan-Do-Study-Act” (PDSA) cycles to “test” small, incremental steps that can lead to goal achievement (Moule, Evans, & Pollard, 2012; Taylor et al., 2014; Wilkinson & Lynn, 2011). The focus on SMART goals and DDDM was the direct result of a JJ partner suggestion. During an intensive 2-day brainstorming meeting in the first months of JJ-TRIALS, the Kentucky JJ partner made the case that training on data and how to use data was a critical need for the JJ system. The academic partners immediately saw that this was an opportunity where their expertise could be effectively leveraged. This observation from an active, engaged JJ partner was instrumental in determining the design and ultimate vision for JJ-TRIALS.

The training and goal selection was an intensive 7-month process that provided local sites extensive data and rich feedback on each site’s current strengths, as well as opportunities for improvement in addressing substance abuse among the youth served by their respective site. Goal selection was the final step in this process, after which each local change team was expected to pursue their selected goal and to identify new goals as needed. The academic research team checked in with each site monthly to assess progress. The central research question in JJ-TRIALS compared outcomes of those change efforts driven internally by JJ staff, compared with those facilitated by an external coach affiliated with the university-based research teams (see Knight et al., 2016, for more details). The selection of this central research question was also influenced by JJ partner participation. During the design phases of JJ-TRIALS, JJ partner participation helped the academic partners focus on the practical implications of all proposed designs. The design that was ultimately selected was chosen because it was viewed as most informative, from both a scientific and practical perspective, even if it failed to show a difference between the two conditions (i.e., facilitated vs. unfacilitated local change teams). In traditional academic research, such an outcome is often considered a failure. In JJ-TRIALS, finding no differences between these two conditions could indicate that the additional expense and infrastructure of external facilitators is unnecessary—a finding of both practical and scientific value. (Data were also collected to evaluate the overall effect of the training and other components of JJ-TRIALS.)

JJ Partner Involvement in Recruiting JJ Sites

JJ partners were instrumental in helping the academic partners identify, connect with, and select potential JJ sites. Collaboratively, JJ-TRIALS academic research partners and JJ partners identified key characteristics that were essential for ensuring the ability of sites to participate in the study as designed (see Knight et al., 2016). These criteria were meant to be as inclusive as possible, ensuring that the protocol would be flexible enough to meet partner needs while also ensuring fidelity to the requirements of the overall protocol. JJ partners played an active role in helping the academic partners identify sites in their state that would meet these criteria and navigate any unique issues within each system. JJ partner support also gave JJ-TRIALS investigators credibility when they approached potential sites. In New York State, for example, the six local sites (local county probation departments) were selected by the JJ partner, who works in a state-level agency responsible for funding and regulation of all 58 local probation departments in New York. The JJ partner from New York helped identify the sites based on her knowledge of their openness to engage in such initiatives, as well as their capacity to meet the technical requirements for participation.

In Georgia, the JJ partner was the Assistant Deputy Commissioner of Juvenile Justice for the state. She helped JJ investigators navigate a state system that is highly variable in local organization, including geographic location, judicial jurisdiction, and administrative oversight. As such, the successful collaboration with the academic partner required sensitivity to the unique processes, jargon, and culture of each JJ partner. Extensive communication facilitated common understanding of JJ-TRIALS and clarified what participation would involve. With the assistance of the Assistant Deputy Commissioner, six main trial sites and one pilot site were successfully recruited to participate in Georgia. In two sites, which were both independent agencies located in an urban area, the youth served by the participating justice agency were committed to the Georgia Department of Juvenile Justice with an assigned probation officer. The other five sites were considered dependent courts, staffed by probation officers. Youth served in these counties were either committed or probated. Partner involvement was essential for research partners to navigate this complex system.

Partner Involvement in Intervention Activities

The idea of fidelity with flexibility was a foundation of the JJ-TRIALS protocol. The success of JJ-TRIALS required balancing fidelity to the overall protocol to ensure scientific rigor (a priority for academic partners) with flexibility to address diversity among participating sites. To be sure, this concept required responsiveness to needs and desires (a priority for JJ partners and participating sites). JJ partners were crucial to achieving this balance as they functioned as a liaison between the JJ-TRIALS academic partners and local sites. Throughout the JJ-TRIALS project (but especially when the study launched), JJ partners facilitated a feedback loop whereby the research team received constructive feedback from sites that allowed them to quickly make any necessary changes to the protocol. Sometimes feedback from sites was contradictory, but discussions that included JJ partners and academic partners led to solutions that often allowed flexible tailoring to site needs while maintaining scientific rigor. In New York, for example, sites were particularly interested in the JJ-TRIALS behavioral health training, which included online informational sessions and web-based live-activity sessions. However, interest in the behavioral health training was highly variable across sites and states. JJ partners helped the academic researchers understand the variations across states (e.g., continuing education requirements) that contributed to these diverse reactions to JJ-TRIALS components. Ultimately, JJ-TRIALS developed a flexible framework to address and document this site diversity.

Another example of partners ensuring fidelity with flexibility was in the criteria that were used to determine change team composition. Across all JJ sites, local JJ staff identified one or two behavioral health partners to join them as part of the local change team. Like the criteria for selecting sites, the criteria for selecting behavioral health partners were intentionally flexible. Similarly, the criteria for local change team composition were left generally broad, with the primary requirement being that both JJ staff and local behavioral health partners participated. Across JJ-TRIALS, local change teams consisted of 8 to 10 members, though the composition of these teams was diverse. A prototypical local change team would include, for example, a chief probation officer, the program director of a local behavioral health agency, a juvenile court administrator, and a JJ DATA manager, along with front-line staff. Sites were allowed to determine membership of their local change team with few constraints. This commitment flexibility allowed local sites to adapt the intervention to meet their needs.

JJ partners also helped academic partners understand major system changes that would be relevant to local sites. For example, immediately before launching JJ-TRIALS, Georgia had adopted legal mandates requiring the use of evidence-based treatment programs. Even so, many JJ youth were not successfully accessing or participating in services. The JJ-TRIALS intervention was an opportunity for sites in Georgia, which included local JJ agencies as well as partnering behavioral health agencies, to openly discuss perceived challenges to implementation of these mandates. Similar conversations about locally relevant issues took place at all sites participating in JJ-TRIALS. JJ partner participation ensured that JJ-TRIALS investigators were also informed of such issues, which enabled the latter to produce tailored materials for each site.

Reflections on the Benefits and Challenges of a Participatory Model

The participatory, flexible development of the JJ-TRIALS has benefited all involved partners. JJ partners benefit by establishing and building relationships with academic research partners and by leading efforts to improve their state systems in a way that furthers existing research but also ensures practical benefits to participating sites. JJ partners made many contributions to the design that increased the practical benefits of JJ-TRIALS participation for JJ sites. In addition to the anecdotes mentioned in this paper, active JJ partner participation resulted in improved study materials and reports, as well as better site feedback, training, and targeted data collection from sites. JJ partner participation has ensured that the burden of participation in sites is always a consideration when intervention activities or data-collection activities are proposed. Active JJ partner participation ensures that the scientific objectives of JJ-TRIALS are always considered in balance with the practical and long-term usefulness and value from the perspective of participating JJ sites. Ensuring practical usefulness also enhances the scientific value of JJ-TRIALS by increasing the likelihood that changes will be sustained even after the research project ends, a key concern in implementation science (Proctor et al., 2015; Wiltsey Stirman et al., 2012).

Partnerships of the sort described herein are not without their challenges, however. For JJ partners, participation in a collaborative effort such as JJ-TRIALS required a large commitment of time, a willingness to learn new jargon, and dedication to issues that may seem largely esoteric and unrelated to the day-to-day challenges they face. Also needed was a willingness to champion the value of participation and research to sites and other state-level leaders. For academic partners, participation in this collaborative effort required a willingness to factor in additional processes and time for soliciting feedback from partners; to be open and respectful to different perspectives; and, at times, to have a willingness to rethink a preferred approach entirely. The tension inherent in the concept of fidelity with flexibility requires creative methodological thinking on the part of researchers and extensive ongoing conversations to maintain a commitment to this principle.

For participating JJ sites, the benefits of participation in this initiative were counterbalanced by the additional time and reporting requirements that are inherent in any research endeavor. For a system that is notoriously underfunded and overworked, participation in a research study such as this required a commitment of time, energy, and resources that can be difficult to muster. Our experiences suggest that participatory research will not work without a deep commitment from both partners and a profound respect for the perspective of the other parties. Strong leadership is necessary, as is a respect for the additional time and process that is involved in seeking out the diverse perspectives of those participating in JJ-TRIALS.

Summary, Recommendations, and Conclusions

For future investigators who hope to follow in the path of JJ-TRIALS, we recommend academic researchers ensure that JJ partners are treated as true partners with a voice in all aspects of study design. Researchers should engage with JJ partners from study conception through the dissemination of findings. Biannual in-person meetings and frequent phone meetings, which include both JJ and academic partners, have built a strong sense of camaraderie and interpersonal and professional respect within JJ-TRIALS. This respect was built by a commitment to allocating time at meetings for JJ partners to offer feedback, ensuring that JJ partners are voting members of the steering committee, and including interested JJ partners as active participants in the overall scientific design process.

Further, we recommend that JJ-TRIALS partners co-author manuscripts and serve as presenters and discussants at scientific conferences. We also suggest that they participate in work groups tasked with solving difficult methodological challenges. Academic partners are interested and willing to work with JJ partners to develop presentations at professional conferences that the JJ partners routinely attend. Common slides have been developed for JJ-TRIALS presentations, and these slides ensure that the contributions of JJ partners are recognized, along with academic partners, in each presentation on JJ-TRIALS. In short, academic partners and JJ partners hold each other in high regard and are committed to making this a valuable experience for all involved parties.

This type of collaboration—between the worlds of academia and of juvenile corrections—represented by JJ-TRIALS is often rare due to diverse cultural and, at times, competing interests of stakeholders (Aarons et al., 2014). Despite the challenges involved in collaboration between academia and the justice systems, our experiences reveal numerous benefits of such partnerships. We encourage other researchers to engage in this challenging but highly rewarding process. JJ partner involvement in JJ-TRIALS has been crucial to the development of a study we all believe will be influential on the field as a whole when completed in 2018. Together, we are building models for successful collaboration and approaches to improve the ability of the justice system to adopt and implement evidence-based policies and procedures to better address justice-involved youth in need of substance abuse, mental health, and HIV services.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded under the JJ-TRIALS cooperative agreement, funded at the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) by the National Institutes of Health (NIH). The authors gratefully acknowledge the collaborative contributions of NIDA and support from the following grant awards: Chestnut Health Systems (U01DA036221); Columbia University (U01DA036226); Emory University (U01DA036233); Mississippi State University (U01DA036176); Temple University (U01DA036225); Texas Christian University (U01DA036224); and the University of Kentucky (U01DA036158; T32DA035200). NIDA Science Officer on this project is Tisha Wiley. Clinical Trials Registration: NCT02672150. The contents of this publication are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIDA, NIH, or the participating universities or juvenile justice systems.

Biographies

Carl G. Leukefeld, PhD

Carl Leukefeld is Professor of Behavioral Science, Chair of the Department of Behavioral Science, and the Bell Alcohol and Addictions Endowed Chair at the University of Kentucky. His research, teaching, publications and clinical interests, which began at the National Institute on Drug Abuse, include addictions and dependency behavior, assessment, translational interventions, HIV, criminal justice, and health services.

Margaret Cawood, MS

Margaret Cawood is a Deputy Commissioner with Georgia Department of Juvenile Justice. With a Master of Science in Criminology from Florida State University, she has over 30 years of experience in the youth service field. During her sixteen years with Georgia Department of Juvenile Justice, she has had leadership responsibilities over detention centers, field operations and juvenile justice reform implementation. In her current capacity with DJJ Division of Support Services she is responsible for health, behavioral health, programming, training, classification and transportation for Georgia’s state run juvenile justice system. Prior to joining DJJ, Mrs. Cawood implemented and supervised child and adolescent community based services in both Tennessee and Georgia. In 2008, the Northwest Georgia Region received a SAMHSA System of Care Grant to develop an integrated system of services and supports for youth with mental health needs. Mrs. Cawood served in a leadership capacity in the successful grant implementation. She currently serves on Georgia’s Interagency Directors’ Team, a multi-agency leadership collaborative which is a subgroup of the Georgia Behavioral Health Coordinating Council. Mrs. Cawood has provided workshop presentations in both Georgia and nationally specializing in topics such as juvenile justice, system of care and leadership.

Tisha Wiley, PhD

Tisha Wiley is a program director at the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) and the NIDA Project Scientist for the JJ-TRIALS cooperative. She received her Ph.D. in Social Psychology from the University of Illinois at Chicago.

Angela A. Robertson, PhD

Dr. Angela Robertson received her Master’s degree in Clinical Psychology from East Carolina University in 1978 and worked in community mental health and substance abuse treatment for 16 years. She obtained her Doctorate in Sociology from Mississippi State University in 2003. Since 1994, Dr. Robertson has been conducting multi-site and longitudinal research on behavioral interventions to reduce alcohol and drug use, impaired driving, STI/HIV risk behavior, and criminal recidivism among substance abusing and offender populations.

Jacqueline Horan Fisher, PhD

Jacqueline Horan Fisher is an Associate Research Scientist within the Adolescent and Family Research department at The National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse (CASA). Her research focuses on understanding predictors and trajectories of adolescent delinquency, legal system involvement, and substance use. She uses this research to inform the development of evidence-based intervention techniques for youth involved in the behavioral healthcare system and to improve behavioral health service delivery to justice-involved youth.

Nancy Arrigona, MPA

Nancy Arrigona is a research manager with the Council on State Governments Justice Center working with a focus toward juvenile justice issues, working with states to assess system performance and increase data capacity and the use of data in decision making. Prior to joining the Justice Center, Nancy was Director of Research and Planning with the Texas Juvenile Justice Department (TJJD). As Director she is responsible for conducting juvenile justice program evaluations, policy impact analysis, cost effectiveness studies, performance measure development, the development and implementation of statewide assessment instruments and tools and statistical modeling and analysis. Nancy was the Director of Research for the Texas Juvenile Probation Commission prior to the merger which created the TJJD and was the Director of Research for the Texas Criminal Justice Policy Council prior to her employment with the Juvenile Probation Commission. She has developed, designed, and directed evaluations of pilot and existing programs in corrections, juvenile justice, prevention, human services, mental health, and education and designed and implemented the Risk and Needs Assessment Instrument used by juvenile probation departments throughout the state. She acts as an advisor on the development of evaluation designs and the implementation of research efforts, and serves as a member to numerous advisory boards and task force efforts. Ms. Arrigona has over twenty-five years of experience in criminal justice and juvenile justice research.

Patricia Donohue, MPA

Patricia M. Donohue is a Community Correction Representative III with the DCJS Office of Probation and Correctional Alternatives. She is responsible for juvenile justice and training at OPCA. From 2002–2004, Patti was a Criminal Justice Program Representative with DCJS in the Office of Funding and Program Assistance, developing and managing grants to localities. Patti also worked for the NYS Council on Children and Families from 1999 to 2002 as a Certified Restorative Justice Trainer; and for the Albany County Probation Department from 1985 to 1999, as a POT, PO, Senior PO, and Probation Supervisor, primarily in the Juvenile Intake/Diversion Unit. Patti holds a Master’s Degree in Criminal Justice from SUNY Albany and a Master’s Degree in Public Administration from Marist College.

Michelle Staples-Horne, MD, MS, MPH

Dr. Michelle Staples-Horne has been Medical Director for the Georgia Department of Juvenile Justice (DJJ) for over twenty-three years. She is responsible for the clinical supervision of medical services to over 1300 youth served daily by the Department in 28 secure facilities across the state. She serves as Adjunct Faculty for Morehouse School of Medicine’s Department of Pediatrics and for Emory University’s Rollins School of Public Health. Dr. Staples-Horne has provided training, subject matter expert legal consultation, and contributed numerous scientific articles and book chapters on correctional health care. She is the recipient of the American College of Correctional Physician’s Armond Start Award of Excellence and the National Commission on Correctional Health Care’s Bernard P. Harrison Award of Merit for leadership and advocacy in serving the health care needs of youth in custody. She is currently serving on the Board of Commissioners for the American Correctional Association.

Philip W. Harris, PhD

Phil Harris has directed research on police and correctional decision making, evaluations of juvenile delinquency programs, prediction of juvenile recidivism, and the development of information systems that serve to improve decisions made about delinquent youths. His recent publications have appeared in Justice Quarterly, Cityscape, OJJDP’s Journal of Juvenile Justice, Criminology, the Journal of Adolescence, the Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, the Professional Geographer, Statistical Analysis and Data Mining, and the Journal of Youth and Adolescence. He also co-authored the book, Criminal Justice Policy and Planning (Elsevier-Anderson, 2016). He is co-founder of and strategic planning adviser to the Council of Juvenile Correctional Administrators.

Richard Dembo, PhD

Dr. Dembo has published extensively in the field of juvenile justice. He was Principal Researcher on the Miami-Dade, National Demonstration Project from 2000–2009, which transformed the front end of the juvenile justice system in that County. He is very community involved. He has been a major party in the flow of millions of dollars in federal, state and local funds into the University of South Florida and the Tampa Bay area for various research and service delivery projects addressing the needs of high risk youth, their families and their surrounding communities.

Judy Roysden, BA

Judy Roysden has served the State of Florida Department of Juvenile Justice (DJJ) and the community for over thirty-one years. She has extensive work experience in the field, starting her career as an intern in the dependency/delinquency field with the Department of Health and Rehabilitative Services and then with the formation of the Department of Juvenile Justice in 1994. She has worked in all branches of the Juvenile Justice Department, starting with detention services, and then onto probation and community intervention. She has served as Chief Probation Officer for Polk, Highlands and Hardee County for five years and then returned to Hillsborough County in 2011 as Chief Probation Officer. She oversees the Department of Juvenile Justice’s probation and community intervention services in Hillsborough County.

She has piloted several programs in Polk and Hillsborough to include the Georgetown Crossover Initiative, Community Based Intervention Implementation, the Juvenile Alternative Detention Initiative, and Juvenile Justice Systems Improvement Project.

Judy Roysden holds a bachelor’s degree in Criminal Justice from the University of South Florida and completed her Certified Public Management training from Florida State University.

Katherine R. Marks, PhD

Katherine Marks is a postdoctoral fellow in the Department of Behavioral Science at the University of Kentucky. Her research focus is on the recovering process from substance use disorders, with a particular interest in women and environmental factors that can support recovering outcomes. Dr. Marks has also conducted research on cognitive, behavioral, and pharmacological interventions for substance use disorders. Dr. Marks holds a Ph.D. from the University of Kentucky in Experimental Psychology.

Contributor Information

Carl G. Leukefeld, Department of Behavioral Science, University of Kentucky.

Margaret Cawood, Georgia Department of Juvenile Justice.

Tisha Wiley, National Institute on Drug Abuse.

Angela A. Robertson, Social Science Research Center, Mississippi State University.

Jacqueline Horan Fisher, The National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse.

Nancy Arrigona, Council of State Governments Justice Center.

Patricia Donohue, New York State Division of Criminal Justice Services.

Michelle Staples-Horne, Georgia Department of Juvenile Justice.

Philip W. Harris, Department of Criminal Justice, Temple University.

Richard Dembo, Department of Criminology, University of South Florida.

Judy Roysden, Florida Department of Juvenile Justice.

Katherine R. Marks, Department of Behavioral Science, University of Kentucky.

References

- Aarons GA, Fettes D, Hurlburt M, Palkinkas L, Gunderson L, Willging C, Chaffin M. Collaboration, negotiation, and coalescence for interagency collaborative teams to scale-up evidence-based practice. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2014;43(6):915–928. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2013.876642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergold J, Thomas S. Participatory research methods: A methodological approach in motion. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung/Forum: Qualitative Social Research. 2012;13(1) Art. 30. [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharyya O, Reeves S, Zwarenstein M. What is implementation research? Rationale, concepts, and practices. Research on Social Work Practice. 2009;19(5):491–502. [Google Scholar]

- Binard J, Prichard M. Model policies for juvenile justice and substance abuse treatment: A report by Reclaiming Futures. Princeton, NJ: Robert Wood Johnson Foundation; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Bovend’Eerdt TJ, Botell RE, Wade DT. Writing SMART rehabilitation goals and achieving goal attainment scaling: A practical guide. Clinical Rehabilitation. 2009;23(4):352–361. doi: 10.1177/0269215508101741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cashman SB, Adeky S, Allen AJ, 3rd, Corburn J, Israel BA, Montaño J, Rafelito A, Rhodes SD, Swanston S, Wallerstein N, Eng E. The power and the promise: Working with communities to analyze data, interpret findings, and get to outcomes. American Journal of Public Health. 2008;98(8):1407–1417. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.113571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan YF, Dennis ML, Funk RR. Prevalence and comorbidity of major internalizing and externalizing problems among adolescents and adults presenting to substance abuse treatment. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2008;34:14–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2006.12.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dean JW, Bowen DE. Management theory and total quality: Improving research and practice through theory development. Academy of Management Review. 1994;19(3):392–418. [Google Scholar]

- Englund MM, Egeland B, Olivia EM, Collins WA. Childhood and adolescent predictors of heavy drinking and alcohol use disorders in early adulthood: A longitudinal developmental analysis. Addiction. 2008;103:23–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02174.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedmann PD, Wilson D, Knudsen HK, Ducharme LJ, Welsh WN, Frisman L, Knight K, Lin HJ, James A, Albizu-Garcia CE, Pankow J, Hall EA, Urbine TF, Abdel-Salam S, Duvall JL, Vocci FJ. Effect of an organizational linkage intervention on staff perceptions of medication-assisted treatment and referral intentions in community corrections. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2015;50:50–58. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2014.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenwood PW, Welsh BC. Promoting evidence-based practice in delinquency prevention at the state level: Principles, progress, and policy directions. Criminology & Public Policy. 2012;11(3):493–513. [Google Scholar]

- Israel BA, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, Becker AB. Review of community-based research: Assessing partnership approaches to improve public health. Annual Review of Public Health. 1998;19:173–202. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.19.1.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use 1975–2012: 2012 overview—key findings on adolescent drug use. Ann Arbor, MI: Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kandel DB, Johnson JG, Bird HR, Weissman MM, Goodman SH, Lahey BB, Regier DA, Schwab-Stone ME. Psychiatric comorbidity among adolescents with substance use disorders: Findings from the MECA Study. Journal of the American Academy for Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1999;38:693–699. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199906000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight DK, Belenko S, Wiley T, Robertson AA, Arrigona N, Dennis M, Bartkowski JP, McReynolds LS, Becan JE, Knudsen HK, Wasserman GA, Rose E, DiClemente R, Leukefeld C JJ TRIALS Cooperative. Study protocol: Juvenile Justice—Translational Research on Interventions for Adolescents in the Legal System (JJ-TRIALS): A cluster randomized trial targeting system-wide improvement in substance use services. Implementation Science. 2016;11(1):57. doi: 10.1186/s13012-016-0423-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leukefeld CG, Marks KR, Stoops WW, Reynolds B, Lester C, Sanchez L, Martin CA. Substance misuse and abuse. In: Gulotta TP, Adams GR, Evans M, editors. Handbook of adolescent behavioral problems. 2. New York, NY: Springer; 2015. pp. 495–513. [Google Scholar]

- Liddle HA, Rowe CL, Dakof GA, Henderson CE, Greenbaum PE. Multidimensional family therapy for young adolescent substance abuse: Twelve month outcomes of a randomized controlled trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2009;77:12–25. doi: 10.1037/a0014160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moule P, Evans D, Pollard K. Using the plan-do-study-act model: Pacesetters experiences. International Journal of Healthcare Quality Assurance. 2012;26(7):593–600. doi: 10.1108/IJHCQA-09-2011-0053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse. Criminal neglect: Substance abuse, juvenile justice and the children left behind. New York, NY: National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse at Columbia University; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Orwin RG, Edwards JM, Buchanan RM, Flewelling RL, Landy AL. Data- driven decision-making in the prevention of substance-related harm: Results from the Strategic Prevention Framework State Incentive Grant Program. Contemporary Drug Problems. 2012;39(1):73–106. [Google Scholar]

- Pearson FS, Shafer MS, Dembo R, del Mar Vega-Debién G, Pankow J, Duvall JL, Belenko S, Frisman LK, Visher CA, Pich M, Patterson Y. Efficacy of a process improvement intervention on delivery of HIV services to offenders: A multisite trial. American Journal of Public Health. 2014;104(12):2385–2391. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters DH, Adam T, Alonge O, Agyepong IA, Tran N. Implementation research: What it is and how to do it. British Medical Journal. 2013;347:f6753. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f6753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proctor EK, Landsverk J, Aarons G, Chambers D, Glisson C, Mittman B. Implementation research in mental health services: An emerging science with conceptual, methodological, and training challenges. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. 2009;36(1):24–34. doi: 10.1007/s10488-008-0197-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proctor E, Luke D, Calhoun A, McMillen C, Brownson R, McCrary S, Padek M. Sustainability of evidence-based healthcare: Research agenda, methodological advances, and infrastructure support. Implementation Science. 2015;10(1):88. doi: 10.1186/s13012-015-0274-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuyler Ikemoto G, Marsh JA. Cutting through the “data-driven” mantra: Different conceptions of data-drive decision-making. Evidence and Decision Making: Yearbook of the National Society for the Study of Education. 2007;106(1):105–131. [Google Scholar]

- Scott RA, Shore AR. Why sociology does not apply: A study of the use of sociology in public planning. New York, NY: Elsevier; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Stone AL, Becker LG, Huber AM, Catalano RF. Review of risk and protective factors of substance use and problem use in emerging adulthood. Addictive Behaviors. 2012;37:747–775. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Systems-level implementation of Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2013. Technical Assistance Publication (TAP) Series 33. HHS Publication No. (SMA) 13-4741. [Google Scholar]

- Swift W, Coffey C, Carlin JB, Degenhardt L, Patton GC. Adolescent cannabis users at 24 years: Trajectories to regular weekly use and dependence in young adulthood. Addiction. 2008;103:1361–1370. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02246.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabak RG, Khoong EC, Chambers DA, Brownson RC. Bridging research and practice: Models for dissemination and implementation research. American Journal of Preventative Medicine. 2012;43:337–350. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.05.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor MJ, McNicholas C, Nicolay C, Darzi A, Bell D, Reed JE. Systematic review of the application of the plan–do–study–act method to improve quality in healthcare. BMJ Quality and Safety. 2014;23(4):290–298. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2013-001862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker SC, Bumbarger BK, Phillippi SW. Achieving successful evidence-based practice implementation in juvenile justice: The importance of diagnostic and evaluative capacity. Evaluation and Program Planning. 2015;52:189–197. doi: 10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2015.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wasserman G, McReynolds L, Schwalbe CS, Keating J, Shane A. Psychiatric disorder, comorbidity, and suicidal behavior in juvenile justice youth. Criminal Justice and Behavior. 2010;379(12):1361–1376. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss G. The fourth wave: Juvenile justice reforms for the twenty-first century. New York, NY: National Campaign to Reform State Juvenile Justice Systems; Winter. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Welsh WN, Knudsen HK, Knight K, Ducharme L, Pankow J, Urbine T, Lindsey A, Abdel-Salam S, Wood J, Monico L, Link N, Albizu-Garcia C, Friedmann PD. Effects of an organizational linkage intervention on inter-organizational service coordination between probation/parole agencies and community treatment providers. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. 2016;43(1):105–121. doi: 10.1007/s10488-014-0623-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson A, Lynn J. A common sense approach to improving advance care planning using the “Plan-Do-Study-Act” cycle. BMJ Supportive and Palliative Care. 2011;1:85. [Google Scholar]

- Wiltsey Stirman S, Kimberly J, Cook N, Calloway A, Castro F, Charns M. The sustainability of new programs and innovations: a review of the empirical literature and recommendations for future research. Implementation Science. 2012;7(1):17. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-7-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winters KC, Lee CY. Likelihood of developing an alcohol and cannabis use disorder during youth: Association with recent use and age. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2008;92(1–3):239–247. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young DW, Dembo R, Henderson CE. A national survey of substance abuse treatment for juvenile offenders. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2007;32(3):255–266. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2006.12.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]