Abstract

Nanomaterials are increasingly used as drug carriers for cancer therapy. Nanomaterials also appeal to researchers in the areas of cancer diagnosis and biomarker discovery. Several antitumor nanodrugs are currently being tested in preclinical and clinical trials and show promise in therapeutic and other settings. We review the development of nanomaterial drug carriers, including liposomes, polymer nanoparticles, dendritic polymers, and nanomicelles, for the diagnosis and treatment of various cancers. The prospects of nanomaterials as drug carriers for future clinical applications are also discussed.

Keywords: nanoparticles, drug carriers, cancer treatment, delivery system, clinical trials

1. Introduction

According to the World Health Organization's World Cancer Report 2014, cancer caused 8.2 million deaths worldwide in 2012, and this number is expected to rise to 22 million by 2035 (1). Along with surgery and radiotherapy, chemotherapy is a mainstay of cancer treatment. Chemotherapy is the most frequently used systemic treatment for suppressing cancer cell proliferation, disease progression and metastasis. However, chemotherapeutic drugs not only kill proliferating cancer cells but also inevitably attack normal cells, causing adverse effects. Therefore, antitumor drug vehicles that maintain or improve the efficacy of chemotherapy while reducing the severity of reactions and side effects are urgently needed.

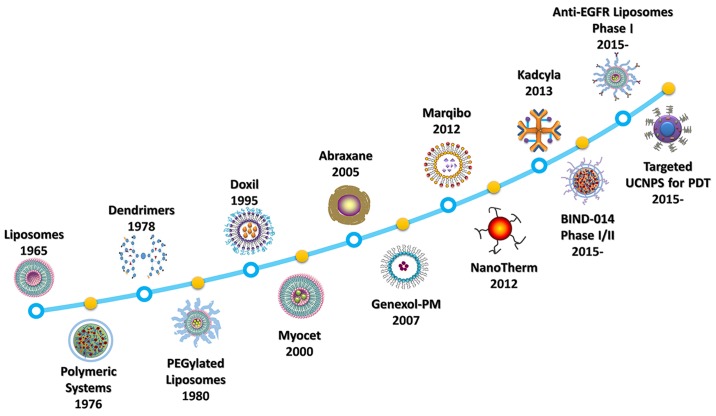

Nanoparticles, which can be adapted to have various biological properties and can be used in a range of settings, provide a safer and effective means of delivering chemotherapy (2–4). In the past decade, approximately 12,000 reports on the topic of nanomaterials as drug carriers in cancer treatment have been published. However, there remains a gap between technological advances and clinical applications. Many nanodrugs have been developed over the last 50 years (Fig. 1). In 1965, a group led by Bangham discovered liposomes (5). A liposomal formulation of doxorubicin (Doxil), was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 1995 for treating AIDS-related Kaposi sarcoma (6). In 2005, an albumin-based nanoparticle, protein-bound paclitaxel (Abraxane) (7), has been approved by the FDA for clinical use in the treatment of breast cancer, non-small cell lung cancer, and pancreatic cancer. More recently, in 2013, targeted ado-trastuzumab emtansine (DM1) (Kadcyla) was approved for use in patients with human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive breast cancer (8).

Figure 1.

Timeline of the development of nanomedicines. Liposomes (5), polymeric systems (151), dendrimers (152), and PEGylated liposomes (153) were developed as nanodrug carriers in the early phase of discovery (before 1995). Doxil (doxorubicin) was the first FDA-approved liposome for use in cancer (154). As nanomedicine developed, the non-PEGylated liposome Myocet (doxorubicin) (155), the albumin-based nanoparticle (NP) Abraxane (doxorubicin) (63), the PEG-PLA polymeric micelle Genexol-PM (paclitaxel) (98), the vincristine sulfate liposome Marqibo (156), the iron oxide NP NanoTherm (157), and the targeted ado-trastuzumab emtansine (DM1) liposome Kadcyla (158) have been approved for clinical use. PEG-PLGA polymeric NPs (BIND-014) completed phase II clinical trials in advanced cancers (68) and anti-epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) immunoliposomes is in phase II clinical trials recruiting of breast cancer (159,160). The physical properties of upconversion nanoparticles (UCNPs) used in photodynamic therapy (PDT) also represent a promising direction in future research (115).

Nanomaterials have a number of advantages as drug carriers. Nanocarriers can: i) increase water solubility and protect drugs dissolved in the bloodstream, improving the pharmacokinetic and pharmacological properties of the drugs; ii) target the delivery of drugs in a tissue- or cell-specific manner, thereby limiting drug accumulation in the kidneys, liver, spleen, and other non-targeted organs and enhancing therapeutic efficacy; and iii) deliver a combination of imaging and therapeutic agents for real-time monitoring of therapeutic efficacy (9,10).

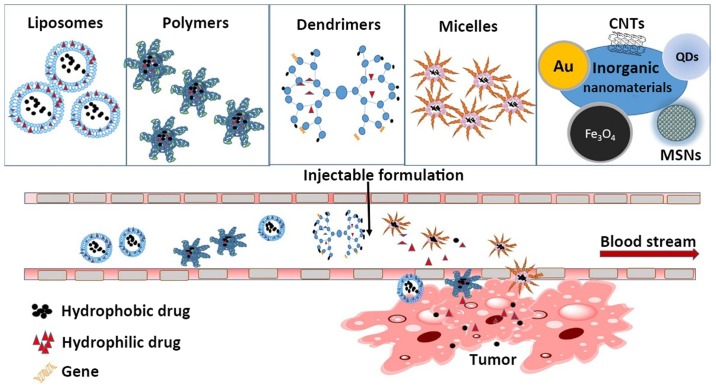

This review summarizes recent developments in the use of nanomaterials in cancer therapy. Specifically, we discuss the use of liposomes, polymer nanoparticles, dendritic polymers, and micelles as drug carriers (Fig. 2). Each category of nanomaterials has unique strengths and limitations; thus, a major goal of this review is to unveil the emerging possibilities of different nanovectors for different therapeutic applications, their relevant molecular targets, and their advantages and disadvantages.

Figure 2.

Nanomaterials used as drug carriers for cancer therapy. With their distinct biological characteristics, nanomaterials can improve the enhanced permeability and retention effect, increase bioavailability, reduce the toxicity of chemotherapy drugs, release hydrophobic or hydrophilic chemotherapy drugs into the bloodstream, and achieve cytotoxic effects against cancer cells. CNTs, carbon nanotubes; QDs, quantum dots; MSNs, metal nanoparticles.

2. Liposomes

Liposomes consist of an aqueous core surrounded by one or several layers of phospholipids and cholesterol that form a lipid bilayer. Because of this unique structure, liposomes can load and hold hydrophilic agents in the aqueous compartment and hydrophobic agents in the lipid space (11). Because their composition is similar to that of the cell membrane, liposomes are more biocompatible than other synthetic materials. In addition, distinct surface modification with functional ligands and differences in size and charge make liposomes coat with polyethylene glycol (PEG) useful for specific drug delivery tasks.

Liposomes have several additional advantages as nanocarriers for drug delivery applications. Liposomes protect the loaded drug from degradation and prevent undesirable exposure of the drug to the environment, which may slow the rate of drug release (12–14). Specific lipid species, such as cholesterol and rigid saturated lipids, stabilize the lipid bilayer to resist attack from plasma proteins and reduce drug leakage (13,14). However, the present challenge facing the development of liposomes as drug carriers is how to control their distribution and removal in vivo.

Recently, a number of studies have focused on modifying liposome drug-releasing mechanisms. For example, drug release from liposomes can be triggered by ultrasound (15,16), enzymes (17,18), light (19,20), magnetism (21–23), or hyperthermia (24). Drug-releasing liposomes may also be combined with ligand-mediated targeted delivery of nucleic acids (25–28).

Further, multifunctional and multicomponent formulations (29) have been designed to enhance localization selectivity, allowing specific targeting of distinct tissue types. Chen et al (30) used a glycyrrhetinic acid (GA)-modified liposome to load oxaliplatin (OX) for liver-targeted biodistribution studies and demonstrated that the ratio of the area under the curve (AUC) of GA-OX-liposomes to the AUC of OX-liposomes was 3.84. These results suggest that liposomes exhibit excellent tissue- and organ-specific targeting.

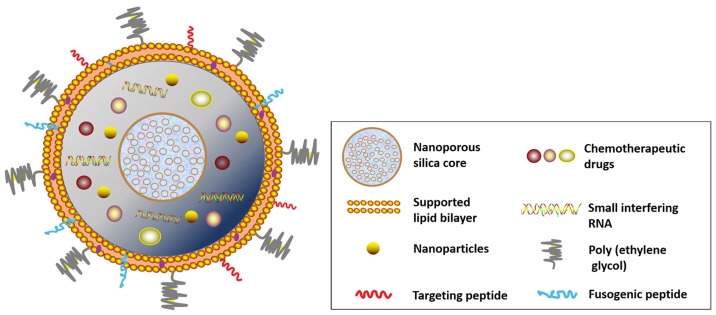

Liposomes not only increase the intracellular uptake of drugs but also can be used to modify anticancer agents, antibiotics, and DNA. Using an AAN-TAT-liposome platform, Liu et al (31) created a doxorubicin carrier that enhanced the drug tumoricidal effect and reduced systemic adverse effects. The RNA liposome platform is another promising strategy for boosting therapeutic efficacy (32). Recently, protocells have been designed to incorporate various types of modification to achieve a comprehensive nanodrug delivery system (Fig. 3). Chemotherapy agents, short interfering RNA, and nanoparticles, for instance, can be coupled with or encapsulated in a nanoporous silica core for simulating chemotherapy treatment with site-specific drug delivery. The supporting lipid bilayer can also be decorated with surface-targeting molecules, such as fusogenic peptide and polyethylene glycol, according to tumor type or vasculature.

Figure 3.

Lipid bilayer-wrapped nanoporous drug delivery system in protocells. It can be decorated with multi-types chemotherapy agents and surface-targeting molecules.

Liposomes can also be used as a nonviral vector for gene delivery, making the liposome/DNA complex one of the most promising tools for cancer gene therapy (33). For example, Felgner and colleagues (34) developed cationic liposome-mediated gene delivery, in which a liposome was incorporated with an antisense oligodeoxynucleotide specific for growth factor receptor-bound protein 2 (Grb2) mRNA (L-Grb2). These liposomes inhibited Grb2 protein expression, reduced proliferation of bcr-abl-positive leukemia cells, and extended survival durations in mice bearing bcr-abl-positive leukemia xenografts (35) (Table I).

Table I.

Liposome formulations in clinical trials or clinical use.

| Product | Drug | Status | Applications | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Doxil | Doxorubicin | Approved | Kaposi sarcoma, ovarian and breast cancers | (6,161) |

| DaunoXome | Daunorubicin | Approved | Kaposi sarcoma | (162) |

| LipoDox | Doxorubicin | Approved | Ovarian and breast cancers | (163) |

| Myocet | Doxorubicin | Approved | Combination therapy for metastatic breast cancer | (155) |

| Marqibo | Vincristine | Approved | Metastatic malignant uveal melanoma | (156) |

| Onivyde | Irinotecan | Approved | Advanced pancreatic cancer | (164) |

| Lipoplatin | Cisplatin | Phase III | Pancreatic, head and neck, breast, gastric, and non-squamous non-small cell lung cancers, mesothelioma | (165) |

| Stimuvax | BLP25 Tecemotide | Phase III | Vaccine for multiple myeloma-developed encephalitis | (166) |

| ThermoDox | Doxorubicin | Phase III | Non-resectable hepatocellular carcinoma | (167) |

| CPX-351 | Cytarabine + daunorubicin | Phase III | Acute myeloid leukemia | (168) |

| Aroplatin | Cisplatin analog | Phase II | Metastatic colorectal carcinoma | (169) |

| Atragen | Tretinoin | Phase II | Acute promyelocytic leukemia, hormone-refractory prostate cancer | (170) |

| Atu027 | PKN3 siRNA | Phase II | Solid tumors | (171) |

| EndoTAG-1 | Paclitaxel | Phase II | Breast and pancreatic cancers | (172) |

| LEP-ETU | Paclitaxel | Phase II | Ovarian, breast, and lung cancers | (173) |

| LE-SN38 | SN38 | Phase II | Metastatic colorectal cancer | (174) |

| MBP-426 | Oxaliplatin | Phase II | Gastric, gastroesophageal, and esophageal adeno-carcinomas | (175) |

| OSI-211 | Lurtotecan | Phase II | Ovarian and head and neck cancers | (176) |

| SPI-077 | Cisplatin | Phase II | Ovarian and head and neck cancers | (177) |

| Liposomal annamycin | Annamycin | Phase I/II | Acute lymphocytic leukemia | (178) |

| S-CKD-602 | Camptothecin analog | Phase I/II | Recurrent or progressive carcinoma of the uterine cervix | (179) |

| OSI-7904L | Thymidylate synthase inhibitor | Phase I/II | Advanced colorectal, head and neck, gastric, and gastroesophageal cancers | (180) |

| Anti-EGFR immuno-liposomes | Doxorubicin | Phase I | Solid tumors | (159) |

| INX-0076 | Topotecan | Phase I | Advanced solid tumors | (181) |

| INX-0125 | Vinorelbine | Phase I | Advanced solid tumors | (182) |

| LEM-ETU | Mitoxantrone | Phase I | Leukemia, breast, stomach, liver, and ovarian cancers | (183) |

| Liposomal Grb-2 | Grb2-antisense oligodeoxynucleotide | Phase I | Acute myeloid leukemia, chronic myelogenous leukemia, and acute lymphoblastic leukemia | (184) |

| Lipoxal | Oxaliplatin | Phase I | Advanced gastrointestinal cancer | (185) |

| LiPlaCis | Cisplatin | Phase I | Advanced or refractory tumors | (186) |

EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor.

3. Polymers

Polymers can be categorized as: i) natural polymers, such as proteins, peptides, glycans, starches, and cellulose; ii) synthetic polymers, which are synthesized from natural monomers, for instance, polylactic acid (PLA) and poly (lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA); and iii) microbial fermentation polymers, such as polyhydroxybutyrate (36). Natural and synthetic polymers constitute a diversified platform for synthesis of a variety of nanoparticles, including liposomes, dendrimers, and micelles (Fig. 2).

Polymer nanoparticles, micelles, nanosponges (37,38), nanogels (39), and nanofibers for wound healing have been widely investigated (40,41). Natural polymers that are extensively used in nanoparticle synthesis include chitosan, dextran, albumin, heparin, gelatin, and collagen (42,43). Chitosan-coated PLGA nanoparticles (44,45) and chitosan nanoparticles (46–49) can carry and deliver proteins in an active form and transport them to specific organs. Synthetic polymers, such as PEGylated PLA nanoparticles and PLA-PEG-PLA nanoparticles (50–54), poly-PLGA nanoparticles (55), monomethoxypolyethylene glycol-block-polycaprolactone nanoparticles (56), and N-(2-hydroxypropyl)-methacrylamide copolymers (57), assist in the transport of proteins within the drug capsules. Furthermore, a PEG coating improves the stability of PLA nanoparticles exposed to gastrointestinal fluids and prolonged circulating time (58). Thermosensitive polymers, for which temperature is the triggering signal, can also be used to control and target drug delivery (59).

Nanosponges, which are made from biocompatible, biodegradable polymer nanoparticles, are prepared by fusing erythrocyte membrane vesicles onto PLGA nanoparticles by means of extrusion. Nanosponges are composed of hyper-cross-linked cyclodextrins connected in a three-dimensional network. Nanosponges form porous nanoparticles with sizes <500 nm, so they easily circulate in the bloodstream. As ‘sponges’, they can absorb toxins, secretions, and fragments produced by tumor cells themselves (37,38,60). Their spherical shape and negative surface charge give them a good capacity for incorporating small molecules, macromolecules, ions, and gases within their structure. Therefore, nanosponges have been designed to improve chemotherapeutic efficacy by targeting drug-resistant cells (60–62). The erythrocyte membrane can be used as a cloak containing >3,000 nanosponges. Once they are fully loaded with toxins, nanosponges are safely disposed of by the liver with low toxicity. Therefore, nanosponges are designed to work with any type of cancer or poisoning that exhibits dysregulation of, or abnormalities in, cellular membranes.

Among the polymer-based delivery systems, only one albumin-based nanoparticle, protein-bound paclitaxel (Abraxane) (63), has been approved by the FDA for clinical use in the treatment of breast cancer, non-small cell lung cancer, and pancreatic cancer (Table II). Albumin nanoparticle that incorporates paclitaxel has improved the water solubility of the drug and reduced its dose-limiting toxicity by modifying its pharmacokinetic formulation (64). Given these successes, various albumin-based nanoparticles, such as ABI-008 (65), ABI-009 (66), and ABI-011 (67), are currently undergoing clinical trials. BIND-014 (68) is the first PEG-PLGA targeted polymeric nanoparticle to reach phase I/II studies for the treatment of metastatic cancer and KRAS-positive or squamous cell non-small cell lung cancer. Its pharmaceutical activity is 10-fold higher than that of conventional docetaxel in tumor sites, and it prolongs the time the drug is maintained in the circulation. Also, a targeted cyclodextrin-polymer hybrid nanoparticle (CALAA-01), a short interfering RNA inhibitor designed to inhibit tumor growth and/or reduce tumor size (69), was tested in phase I clinical trial. Current research on polymer nanocarriers focuses on elucidating their mechanisms of action, environmental responses, active targeting, and composite materials. Relevant diagnostic and therapeutic platforms still need to be constructed and evaluated.

Table II.

Drug-loaded polymer nanoparticles in clinical trials or clinical use.

| Product | Drug | Platform | Status | Applications | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abraxane | Paclitaxel | Albumin nanoparticle | Approved | Breast cancer, non-small cell lung cancer, pancreatic cancer | (63) |

| BA-003 | Doxorubicin | Polymeric nanoparticle | Phase III | Hepatocellular carcinoma | (187) |

| DHAD-PBCA-NPs | Mitoxantrone | Polymeric nanoparticle | Phase II | Hepatocellular carcinoma | (188) |

| ProLindac | DACHPt | HPMA-polymeric nanoparticle | Phase II/III | Advanced ovarian cancer | (189) |

| ABI-008 | Docetaxel | Albumin nanoparticle | Phase I/II | Metastatic breast cancer, prostate cancer | (65) |

| ABI-009 | Rapamycin | Albumin nanoparticle | Phase I/II | Solid tumors | (66) |

| ABI-011 | Thiocolchicine dimer | Albumin nanoparticle | Phase I/II | Solid tumors, lymphoma | (190) |

| BIND-014 | Docetaxel | PEG-PLGA polymeric nanoparticle | Phase I/II | Non-small cell lung cancer | (68) |

| Cyclosert | Camptothecin | Cyclodextrin nanoparticle | Phase I/II | Solid tumors, rectal cancer, renal cell carcinoma, non-small cell lung cancer | (191) |

| CALAA-01 | siRNA targeting | Cyclodextrin nanoparticle | Phase I | Solid tumors | (69) |

| Docetaxel-PNP | Docetaxel | Polymeric nanoparticle | Phase I | Solid tumors | (192) |

| Nanotax | Paclitaxel | Polymeric nanoparticle | Phase I | Peritoneal neoplasms | (193) |

DHAD-PBCA-NPs, mitoxantrone-loaded polybutylcyanoacrylate nanoparticles; DACHPt, dicholoro (1,2-diaminocyclohexane) platinum (II); HPMA, N-(2-hydroxypropyl) methacrylamide.

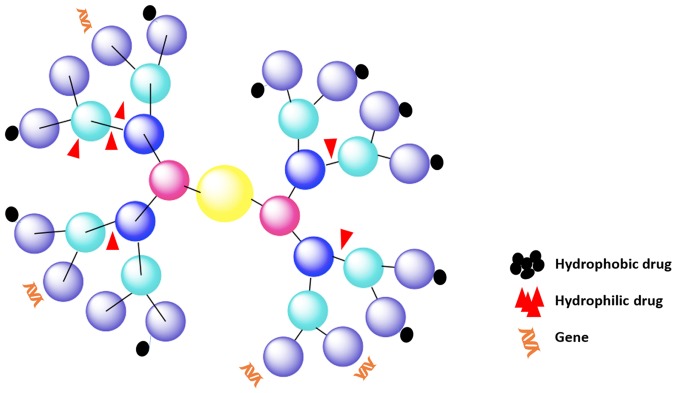

4. Dendrimers

Dendrimers are a unique class of polymeric macromolecules found in nature. Dendrimers began to be synthesized during the period 1970–1990 by Buhleier et al (70) and Tomalia et al (71). They are globular, nanosized (1–100 nm) macromolecules with complex spherical structures. Dendrimers are characterized by: i) a central core; ii) branches, called ‘generations’, emanating from the core; iii) repeat units with at least one branch junction; and iv) many terminal functional groups (Fig. 4) (72,73). Unlike linear polymers, dendrimers have a precisely controllable architecture with tailor-made surface groups. The branches of dendrimers can be decorated with a wide variety of molecules that can be utilized for passive entrapment and eventual release of drugs or other cargoes. The molecular structure of dendrimers can be fine-tuned, and because they are geometrically symmetrical and have many peripheral functional groups, an internal molecular cavity, controlled molecular weight, and nanometer size, they are excellent nanocarriers with good fluid mechanic performance, versatility, and strong adsorption ability.

Figure 4.

Structure of a dendrimer with four generations of side branches. Each generation is represented with a different color.

Dendrimers are self-assembled and stabilize by forming organic or inorganic hybrid nanoparticles. Dendrimers can be linked to liposomes (74–76), nanoparticles (77,78), and carbon nanotubes (79–81) to modulate their solubility for use as drug carriers (74,82) and target-specific carriers (82–84) of detecting agents (such as dye molecules), affinity ligands, radioligands, imaging agents, or pharmaceutically active anticancer compounds.

Thanks to recent advances in synthetic chemistry and characterization techniques, novel dendritic carriers are rapidly being developed. Dendrimers are being widely investigated as gene delivery vectors. For example, polyamidoamine (PAMAM) dendrimers have the ability to condense DNA for transfection. Liu et al (85) used five fluorinated polypropylenimine (PPI) dendrimers to improve DNA transfection efficacy. The heptafluorobutyric acid modified on the PPI dendrimer improved the efficacy of enhanced green fluorescent protein transfection in all five fluorinated PPI dendrimers by 89% over that of regular PPIs. The uptake efficacy achieved with PPI dendrimers (as indicated by both the percentage of positively stained cells and the mean fluorescence intensity) was superior to that of G5-Arg110, bPEI 25K, and four commercial transfection reagents, including Lipofectamine 2000 (with as high as 71% improvement).

Highly branched dendrimer-amplified aptamer probes can be easily rebuilt and have high affinity and specificity for a wide range of targets. They are able to reach various targets with such high sensitivity, reliability, and selectivity because of their novel optical, magnetic, electric, chemical, and biological properties (86). For instance, surface-functionalized PAMAM dendrimers with carboxyl groups, whose particles are spherical colloidal crystal clusters decorated with dendrimer-amplified aptamer probes, are designed to immobilize DNA aptamers; thus, they can serve as high-efficacy probes that target cancer cells. Malik et al (87) showed that conjugates of cisplatin with the negatively charged 4th-generation PEGylated PAMAM dendrimer exhibited antitumor activity against B16F10 solid melanoma tumors. Methotrexate conjugated to PEGylated poly-L-lysine (PLL) dendrimers (G5, PEG1100) has been shown to accumulate in HT1080 fibrosarcoma tumors in rats and mice (88). Al-Jamal et al (89) reported that the complexation of doxorubicin with the novel 6th-generation cationic PLL dendrimer Gly-Lys63 (NH2)64 (molecular weight 8149 kDa) produced systemic anti-angiogenic activity in tumor-bearing mice. Dendrimer nanotechnology has also been used to produce contrast agents, including agents used in molecular imaging (90). Qiao and Shi (86), and Yang et al (91), for instance, successfully synthesized ultrasmall iron oxide nanoparticles by conjugating them with Arg-Gly-Asp-modified dendrimers (G5.NHAc-RGD-Fe3O4 NPs) for targeted magnetic resonance imaging of C6 glioma cells.

Dendrimers have the advantages of being biocompatible and easily eliminated from the body. PAMAM dendrimer nanoparticles, with their large number of surface amino groups, are more biocompatible and circulate for longer in the serum than do small-molecule drugs. Dendrimer nanoparticles are eventually eliminated from the human body through the kidneys along the same metabolic pathways taken by folate (84,92), growth factors (93), peptides (94,95), and antibodies (96). However, dendrimers also have the drawbacks of being cytotoxic to normal cells, and that the end groups present on their peripheries (97) such as PAMAM, PPI, and PLL are cationic groups with physiological stability. This stability increases their cytotoxicity that can inevitably attack normal cells.

5. Micellar nanoparticles

Micellar nanoparticles possess a core and a shell structure. PEG is often used as a hydrophilic shell; shells with hydrophobic domains include PLA (52), PLGA (44,45), polystyrene, poly (cyanoacrylate), poly (vinylpyrrolidone), and polycaprolactone (56). These copolymers are widely used owing to their natural biodegradability and biocompatibility as well as their ability to entrap hydrophobic drugs. A primary mPEG-PLA polymeric micelle loaded with paclitaxel (Genexol-PM) was approved by the FDA in 2007 (98,99). It is loaded with a free-Taxol formulation and has been shown to reduce the severity of toxic effects such as hypersensitivity reactions, hyperlipidemia, and peripheral neuropathy.

Micellar nanoparticles are obtained from self-assembly of amphiphilic block copolymers in aqueous media above the critical micelle concentration (100). The core, consisting of the hydrophobic domain, acts as a reservoir and protects the drug from being dissolved, whereas the hydrophilic shell mainly confers aqueous solubility and steric stability to the micellar structure (27). With this technique, undissolvable drugs, such as paclitaxel and docetaxel, can be covered with a water-solute layer to enhance their hydrophilicity and ultimately facilitate their bioavailability. The hydrophilic shell affords protection and lengthens circulation in vivo, providing enhanced permeability and retention. In recent years, a number of nanomicellar drugs have advanced to clinical trials or to the market (Table III).

Table III.

Micellar nanoparticles in clinical trials or clinical use.

| Product | Drug | Platform | Status | Applications | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genexol-PM | Paclitaxel | mPEG-PLA polymeric micelle | Approved | Breast cancer | (98) |

| Paclical | Paclitaxel | Polymeric micelle | Phase III | Ovarian cancer | (194) |

| SP1049C | Doxorubicin | Pluronic L61 and F 127 polymeric micelle | Phase II/III | Lung cancer | (195) |

| NK105 | Paclitaxel | PEG-PAA polymeric micelle | Phase II/III | Breast and gastric cancers | (196) |

| NC-6004 | Cisplatin | PEG-PGA polymeric micelle | Phase II/III | Solid tumors, gastrointestinal and genitourinary cancers | (197) |

| NK012 | SN-38 | PEG-PGA polymeric micelle | Phase II | Colorectal, lung, and ovarian cancers | (198) |

| Lipotecan | Camptothecin analog | Polymeric micelle | Phase I/II | Liver and renal cancer | (199) |

| NC-4016 | Oxaliplatin | Polymeric micelle | Phase I | Solid tumors | (200) |

| NC-6300 | Epirubicin | PEG-b-PAH polymeric micelle | Phase I | Solid tumors | (201) |

| NK911 | Doxorubicin | PEG-PAA polymeric micelle | Phase I | Solid tumors | (202) |

mPEG, methoxypolyethylene glycol; PLA, polylactic acids; PEG, polyethylene glycol; PAA, polyacrylic acid; PGA, polyglutamic acid; PAH, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon.

With the rise of precision medicine, micellar nanoparticles have become increasingly important for passive targeted cancer therapy. Peptide modification on the surface of the micelle can be used effectively for precise targeting. Integrin-binding sequence peptides with covalent bonds to the micelle can actively target tumors (101). Block copolymers are environmental response modifiers that display a physico-chemical response to stimuli such as temperature (102–104), pH (105), light (106), or electricity (107). Some block copolymers can produce functional signals and higher levels of signaling (103,108); thus, micelles made from them are called ‘intelligent’ block copolymer micelles. The self-assembly of such polypeptide-based copolymers can be triggered by temperature and pH changes (105). Poly (N-isopropylacrylamide) (PNIPAM) is a temperature-sensitive polymer segment with a lowest critical solution temperature of 31–32°C (105). It quickly switches from a hydrated to a dehydrated state, using PNIPAM-OH and the ring-opening polymerization reaction synthesis of PLA (PNIPAM-b-PLA) (104) and self-assembles into dual-response micelle carriers. A series of dual-stimuli responsive polymers such as PNIPAM-b-PGA and PNIPAM-b-PLL have been synthesized as copolymer micelle materials (108). Doxorubicin can be effectively encapsulated in PNIPAM-block-poly (L-histidine) (PNIPAM-b-PLH) micelle carriers as a controlled delivery system for the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma (109). Light-sensitive groups, including the azide, cinnamon acyl, screw pyran, coumarin, and 2-nitrobenzyl groups, have also been widely used in cancer therapeutic settings (106,110,111). Photodynamic therapy (PDT) is a non-invasive treatment modality for a variety of diseases including cancer (112). PDT based on upconversion nanoparticles (UCNPs) has received much attention in recent years. Under near-infrared (NIR) light excitation, UCNPs are able to emit high-energy visible light, which can activate surrounding photosensitizer (PS) molecules to produce singlet oxygen and kill cancer cells (113,114) also represent a promising direction in future research (115,116).

The greatest benefit of biodegradable drug delivery systems is the controlled release of the drug payload to a specific site and the degradation into nontoxic materials for elimination from the body via metabolic pathways (117). Organelle-targeted biodegradable copolymers, mitochondria-targeting gold-peptide, and radiation-hyperthermia nanoassembly-copolymers (118,119) are used to evaluate micro-environmental change by taking advantage of the sensitivity of mitochondria to temperature elevation. In the presence of a thermal stimulus, the passive targeted biodegradable micellar nanoparticles of a copolymer-controlled drug release system are activated, resulting in slow degradation of the nanoparticles into smaller fragments and the release of carried products, which eventually enhance the drug's cytotoxic effects on cancer cells. Currently, new biocompatible and/or biodegradable stimuli-responsive copolymers that form stable micellar systems capable of encapsulating a broad range of chemotherapeutic agents are being developed (120,121).

It is generally accepted that nonviral vectors are safer than viral vectors for gene transfer (122). Biodegradable copolymers based on polylysine were the first nanoparticles used for gene transfer. Currently, PEG-grafted PLGA-PLL (123), pluronic polyethylenimine (PEI), polyphosphoric acid (124), and phosphate (125) micelles are being used as gene carriers for biological separation and cancer diagnosis. However, applications of cationic polymer-based gene delivery systems are limited because the polymers interact with the cell membrane and produce increased toxicity (122).

6. Inorganic nanomaterials

Various forms of inorganic nanoparticles, including quantum dots, superparamagnetic iron oxides, gold nanoparticles, carbon nanotubes, and other metallic and non-metallic nanoparticles or nanoclusters, enhance the efficiency of radiotherapy and improve tumor imaging (119,126). Several of these inorganic nanoparticles are sufficiently small (10–100 nm) to penetrate the capillaries and can be taken up in distinct tissues. Others are larger and need to be delivered at disease-specific anatomic sites for passive targeting. Multifunctional nanodevices are also emerging as tools to target cancer (42,43,127). Such devices can contain not only the drug payload but also specific receptor-targeting agents, such as antibodies or ligands, as well as magnetic resonance imaging contrast agents. Quantum dots and gold nanoparticles exhibit unique optical, electrical, and magnetic properties (128) that are beneficial for imaging the intracellular localization and trafficking of multifunctional carriers. Drugs can also be delivered at specific sites after they are attached, encapsulated, absorbed, entrapped, or dissolved in the nanomaterial matrix. However, in early-stage clinical trials, some inorganic nanomaterials, such as gold nanoparticles (129) and silica nanoparticles (130), have encountered obstacles, including toxicity and a lack of stability. Of the iron oxide nanoparticles, NanoTherm (131), used for the treatment of glioblastoma, is the only one that has obtained approval for clinical use. With NanoTherm, tumors can be thermally ablated by magnetic hyperthermia induced by entrapped superparamagnetic iron oxides.

7. Challenges for extending patient survival by using nanocarriers

Many solid tumors develop several biological features distinguished from those of normal tissues (132). Abnormal tumor structures including physically compromised vasculature, abnormal extracellular matrix (ECM), and high interstitial fluid pressure (IFP), can create constraints that compromise effective delivery of nanotherapeutics (133,134). There are also extravascular barriers to overcome, whereby nanoparticles can extravasate but cannot penetrate through the ECM of the tumors (135). It is well recognized that the irregularity of the tumor vasculature with its abnormal blood flow and impaired venous and lymphatic drainage creates high interstitial fluid pressure, making the diffusion of nutrients and chemotherapeutics throughout the tumor very inefficient, thus presenting challenges to effective diffusion of nanocarriers as well (136).

Liposomes and polymers are the most widely used biodegradable nanocarriers because of their biocompatibility, biodegradability, and mechanical properties. However, because of adverse effects and the still-unclear mechanisms of interaction among nanoparticles, the tumor microenvironment, and tumor cells, these nanocarriers may offer only brief extension of patient survival (Table IV). Despite numerous achievements in liposomal drug delivery, current liposomal formulations have primarily reduced systemic toxicity rather than increasing efficacy. For instance, hydrophilic drugs such as cisplatin are decorated with liposomal bilayers to reduce drug internal toxicity. However, it needs time to degrade the liposome vehicle for the release of the embedded pharmaceutical. Therefore, long systemic circulation and minimal side effects could result in poor efficacy in vivo. Nevertheless, it is still challenging to achieve an optimal balance between high and specific drug bioavailability in tumor tissue and prolonged liposome stability in systemic circulation (137).

Table IV.

Nanomaterials as drug carriers: advantages and disadvantages.

| Nanomaterials | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|

| Liposomes | Controlled release, reduced toxicity, improved stability | Distribution and removal mechanism, breakage in vivo |

| Polymers | Variety, controllable molecular weight | Inflammatory response, degradation pathway |

| Dendrimers | Nanosized cavity, controlled release, self-assembly | Immunoreaction, hematological toxicity |

| Micellar nanoparticles | Simple prescription, passive targeting | Scale-up production, cytotoxicity |

| Inorganic nanomaterials | Multifunctional, modifiable, ability to combine diagnosis and treatment | Metal toxicity, stability, storage |

Despite many advances in the production of more stable, efficient, and safe biopolymers, there remain controversies regarding the safety of polymeric nanomaterials. Some polymers are themselves cytotoxic (41,138). It has been demonstrated, for example, that PEI destabilizes the plasma membrane and activates effector caspase-3; thus, PEI appears to be a proapoptotic agent (138). Inflammatory and immune responses have also been reported (139–141). However, PLGA can be formulated as an acidic product to provoke inflammatory responses, and it has shown minimal systemic toxicity and excellent biocompatibility in vitro and in vivo (142). Thus, advancements in formulating, synthesizing, and modifying biodegradable polymers promise to improve treatment efficacy and reduce adverse effects.

Compared to other types of nanocarriers, dendrimers provide more opportunities for design and adaptation owing to their peculiar tailor-made surfaces. Toxicity associated with dendrimers is primarily attributed to the end groups present on their peripheries (97). Cationic dendrimers with high charge density and high molecular weight, such as PAMAM, PPI, and PLL, are more stable in physiological conditions. This stability increases their cytotoxicity, owing to the excess positive charges on the periphery, which destabilize the cell membrane. However, stability may also cause several adverse effects (143–145). Fortunately, neutral or anionic groups such as sulfonated, carboxylated, and phosphonated groups have been shown to be less toxic (73). In light of this progress, the next step will be to modify the surface groups of dendrimers with minimally toxic reagents in order to adapt them to physiological conditions.

Other nanoparticles of particularly urgent concern are micelles and inorganic nanomaterials, which present challenges with instability, potential toxicity, cytotoxicity, immune response, and chronic inflammation (146,147). For specific targeted therapy, micelles and inorganic nanomaterials can be decorated with receptor-stimuli agents such as PH, light and magnetic resonance imaging contrast agents, one major limitation of this treatment methodology in clinical applications is the poor tissue penetration ability (148,149).

Research aimed at overcoming these drawbacks will facilitate the use of nanomaterials as drug delivery vehicles and eventually improve patient survival. Ideally, an anticancer nanotherapeutic should be able to reach tumors without systemic loss, easily penetrate into the core of the tumor mass, enter tumor cells where their target molecules reside, and completely eradicate the tumors.

8. Conclusion and prospects

Nanotechnology receives extraordinary attention, and its applications in cancer treatment are relatively new and ever-evolving. Nonetheless, it is clear that nanomaterials are promising tools for cancer treatment. In spite of the progress being made in developing drug delivery systems for cancer therapy, a number of critical issues still need to be addressed. Molecularly targeted drugs preferentially modulate functional proteins, so they can be used to treat diseases (150), like cancers, that are characterized by abnormal protein expression and activation. However, such targeting mechanisms can be challenged by the stability of nanomaterials, the development of multi-drug resistance, and the dysregulated accumulation of cancer cells. The ability to decorate nanomaterial shells with multiple chemically or physically active components permits the delivery of different drugs. Therefore, nanomaterial drug carriers can be organized and optimized for site-specific chemotherapy, thermotherapy, photodynamic therapy, and radiotherapy. Although the benefits of metal-based nanoparticles are remarkable, toxicity remains a critical issue. Nano-toxicological issues also need to be addressed so that more effective cancer therapeutic strategies can be developed. Notably, combination therapeutic regimens for different cancer types remain a challenge because of the diverse mechanisms of cancer development. Combination therapy with nanoparticle drug carriers, therefore, warrants further study at the preclinical and clinical levels. Other challenges exist for modified and functionalized nanomaterials with well-established formulations, including improving the localization, biodistribution, biocompatibility, and efficacy of nanodrug systems in vivo, to meet the requirements of precision cancer diagnosis and therapy.

Acknowledgements

We thank Ms. Yazmin Salina at the Department of Clinical Cancer Prevention, and Dr Amy Ninetto, ELS at the Department of Scientific Publications, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center for proofreading and editing of this manuscript. This study was supported by the Scholarship Award for Excellent Doctoral Student Granted of Yunnan Province (6011418150 to Z. Li), the Foundation of Leading Talent Program of Health and Family Planning Commission of Yunnan Province (no. L-201205 to K. Wang), and the Foundation of Institute of Gastroenterology, Research institutions attached to Health and Family Planning Commission of Yunnan Province (2014NS122 to K. Wang).

References

- 1.Shanthi M. Global Status Report on Noncommunicable Diseases 2014. Geneva: WHO Press, World Health Organization; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2.LaVan DA, McGuire T, Langer R. Small-scale systems for in vivo drug delivery. Nat Biotechnol. 2003;21:1184–1191. doi: 10.1038/nbt876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shi J, Xiao Z, Kamaly N, Farokhzad OC. Self-assembled targeted nanoparticles: Evolution of technologies and bench to bedside translation. Acc Chem Res. 2011;44:1123–1134. doi: 10.1021/ar200054n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Langer R. New methods of drug delivery. Science. 1990;249:1527–1533. doi: 10.1126/science.2218494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bangham AD, Standish MM, Watkins JC. Diffusion of univalent ions across the lamellae of swollen phospholipids. J Mol Biol. 1965;13:238–252. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(65)80093-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.James ND, Coker RJ, Tomlinson D, Harris JR, Gompels M, Pinching AJ, Stewart JS. Liposomal doxorubicin (Doxil): An effective new treatment for Kaposi's sarcoma in AIDS. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 1994;6:294–296. doi: 10.1016/S0936-6555(05)80269-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Green MR, Manikhas GM, Orlov S, Afanasyev B, Makhson AM, Bhar P, Hawkins MJ. Abraxane, a novel Cremophor-free, albumin-bound particle form of paclitaxel for the treatment of advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. Ann Oncol. 2006;17:1263–1268. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdl104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kamaly N, Xiao Z, Valencia PM, Radovic-Moreno AF, Farokhzad OC. Targeted polymeric therapeutic nanoparticles: Design, development and clinical translation. Chem Soc Rev. 2012;41:2971–3010. doi: 10.1039/c2cs15344k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Burgess P, Hutt PB, Farokhzad OC, Langer R, Minick S, Zale S. On firm ground: IP protection of therapeutic nanoparticles. Nat Biotechnol. 2010;28:1267–1270. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Farokhzad OC, Langer R. Impact of nanotechnology on drug delivery. ACS Nano. 2009;3:16–20. doi: 10.1021/nn900002m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gulati M, Grover M, Singh S, Singh M. Lipophilic drug derivatives in liposomes. Int J Pharm. 1998;165:129–168. doi: 10.1016/S0378-5173(98)00006-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Scherphof G, Roerdink F, Waite M, Parks J. Disintegration of phosphatidylcholine liposomes in plasma as a result of interaction with high-density lipoproteins. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1978;542:296–307. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(78)90025-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Allen TM, Cleland LG. Serum-induced leakage of liposome contents. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1980;597:418–426. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(80)90118-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Senior J, Gregoriadis G. Is half-life of circulating liposomes determined by changes in their permeability? FEBS Lett. 1982;145:109–114. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(82)81216-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huang S-L, MacDonald RC. Acoustically active liposomes for drug encapsulation and ultrasound-triggered release. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2004;1665:134–141. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2004.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ueno Y, Sonoda S, Suzuki R, Yokouchi M, Kawasoe Y, Tachibana K, Maruyama K, Sakamoto T, Komiya S. Combination of ultrasound and bubble liposome enhance the effect of doxorubicin and inhibit murine osteosarcoma growth. Cancer Biol Ther. 2011;12:270–277. doi: 10.4161/cbt.12.4.16259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pak CC, Erukulla RK, Ahl PL, Janoff AS, Meers P. Elastase activated liposomal delivery to nucleated cells. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1999;1419:111–126. doi: 10.1016/S0005-2736(98)00256-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meers P. Enzyme-activated targeting of liposomes. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2001;53:265–272. doi: 10.1016/S0169-409X(01)00205-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gerasimov OV, Boomer JA, Qualls MM, Thompson DH. Cytosolic drug delivery using pH- and light-sensitive liposomes. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 1999;38:317–338. doi: 10.1016/S0169-409X(99)00035-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bondurant B, Mueller A, O'Brien DF. Photoinitiated destabilization of sterically stabilized liposomes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2001;1511:113–122. doi: 10.1016/S0005-2736(00)00388-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Du B, Han S, Li H, Zhao F, Su X, Cao X, Zhang Z. Multi-functional liposomes showing radiofrequency-triggered release and magnetic resonance imaging for tumor multi-mechanism therapy. Nanoscale. 2015;7:5411–5426. doi: 10.1039/C4NR04257C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Arie AA, Lee JK. Effect of boron doped fullerene C 60 film coating on the electrochemical characteristics of silicon thin film anodes for lithium secondary batteries. Synth Met. 2011;161:158–165. doi: 10.1016/j.synthmet.2010.11.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dao TT, Matsushima T, Murata H. Organic nonvolatile memory transistors based on fullerene and an electron-trapping polymer. Org Electron. 2012;13:2709–2715. doi: 10.1016/j.orgel.2012.07.041. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Papahadjopoulos D, Jacobson K, Nir S, Isac T. Phase transitions in phospholipid vesicles. Fluorescence polarization and permeability measurements concerning the effect of temperature and cholesterol. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1973;311:330–348. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(73)90314-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Landen CN, Jr, Chavez-Reyes A, Bucana C, Schmandt R, Deavers MT, Lopez-Berestein G, Sood AK. Therapeutic EphA2 gene targeting in vivo using neutral liposomal small interfering RNA delivery. Cancer Res. 2005;65:6910–6918. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miller CR, Bondurant B, McLean SD, McGovern KA, O'Brien DF. Liposome-cell interactions in vitro: Effect of liposome surface charge on the binding and endocytosis of conventional and sterically stabilized liposomes. Biochemistry. 1998;37:12875–12883. doi: 10.1021/bi980096y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wolfrum C, Shi S, Jayaprakash KN, Jayaraman M, Wang G, Pandey RK, Rajeev KG, Nakayama T, Charrise K, Ndungo EM, et al. Mechanisms and optimization of in vivo delivery of lipophilic siRNAs. Nat Biotechnol. 2007;25:1149–1157. doi: 10.1038/nbt1339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang Z, Yu Y, Dai W, Lu J, Cui J, Wu H, Yuan L, Zhang H, Wang X, Wang J, et al. The use of a tumor metastasis targeting peptide to deliver doxorubicin-containing liposomes to highly metastatic cancer. Biomaterials. 2012;33:8451–8460. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.08.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Irvine DJ. Drug delivery: One nanoparticle, one kill. Nat Mater. 2011;10:342–343. doi: 10.1038/nmat3014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen J, Jiang H, Wu Y, Li Y, Gao Y. A novel glycyrrhetinic acid-modified oxaliplatin liposome for liver-targeting and in vitro/vivo evaluation. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2015;9:2265–2275. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S81722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 31.Liu Z, Xiong M, Gong J, Zhang Y, Bai N, Luo Y, Li L, Wei Y, Liu Y, Tan X, et al. Legumain protease-activated TAT-liposome cargo for targeting tumours and their microenvironment. Nat Commun. 2014;5:4280–4291. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Davis ME, Zuckerman JE, Choi CHJ, Seligson D, Tolcher A, Alabi CA, Yen Y, Heidel JD, Ribas A. Evidence of RNAi in humans from systemically administered siRNA via targeted nanoparticles. Nature. 2010;464:1067–1070. doi: 10.1038/nature08956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee JH, Lee MJ. Liposome mediated cancer gene therapy: Clinical trials and their lessons to stem cell therapy. Bull Korean Chem Soc. 2012;33:433–442. doi: 10.5012/bkcs.2012.33.2.433. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Felgner PL, Gadek TR, Holm M, Roman R, Chan HW, Wenz M, Northrop JP, Ringold GM, Danielsen M. Lipofection: A highly efficient, lipid-mediated DNA-transfection procedure. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:7413–7417. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.21.7413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tari AM, Gutiérrez-Puente Y, Monaco G, Stephens C, Sun T, Rosenblum M, Belmont J, Arlinghaus R, Lopez-Berestein G. Liposome-incorporated Grb2 antisense oligodeoxynucleotide increases the survival of mice bearing bcr-abl-positive leukemia xenografts. Int J Oncol. 2007;31:1243–1250. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yu L, Dean K, Li L. Polymer blends and composites from renewable resources. Prog Polym Sci. 2006;31:576–602. doi: 10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2006.03.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hu C-MJ, Fang RH, Copp J, Luk BT, Zhang L. A biomimetic nanosponge that absorbs pore-forming toxins. Nat Nanotechnol. 2013;8:336–340. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2013.54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hu C-MJ, Zhang L, Aryal S, Cheung C, Fang RH, Zhang L. Erythrocyte membrane-camouflaged polymeric nanoparticles as a biomimetic delivery platform. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:10980–10985. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1106634108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sinha M, Banik RM, Haldar C, Maiti P. Development of ciprofloxacin hydrochloride loaded poly (ethylene glycol)/chitosan scaffold as wound dressing. Nat Mater. 2013;20:799–807. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nguyen TTT, Ghosh C, Hwang S-G, Dai Tran L, Park JS. Characteristics of curcumin-loaded poly (lactic acid) nanofibers for wound healing. J Mater Sci Mater Med. 2013;48:7125–7133. doi: 10.1007/s10853-013-7527-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tan S, Gan C, Li R, Ye Y, Zhang S, Wu X, Yang YY, Fan W, Wu M. A novel chemosynthetic peptide with β-sheet motif efficiently kills Klebsiella pneumoniae in a mouse model. Int J Nanomedicine. 2015;10:1045–1059. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S73303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Janib SM, Moses AS, MacKay JA. Imaging and drug delivery using theranostic nanoparticles. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2010;62:1052–1063. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2010.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Grossman JH, McNeil SE. Nanotechnology in cancer medicine. Phys Today. 2012;65:38–42. doi: 10.1063/PT.3.1678. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mishra S, De A, Mozumdar S. Drug Delivery System. Clifton: Springer; 2014. Synthesis of thermoresponsive polymers for drug delivery; pp. 77–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gundogdu N, Cetin M. Chitosan-poly (lactide-co-glycolide) (CS-PLGA) nanoparticles containing metformin HCl: Preparation and in vitro evaluation. Pak J Pharm Sci. 2014;27:1923–1929. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tajmir-Riahi HA, Nafisi Sh, Sanyakamdhorn S, Agudelo D, Chanphai P. Applications of chitosan nanoparticles in drug delivery. Methods Mol Biol. 2014;1141:165–184. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-0363-4_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Malhotra M, Tomaro-Duchesneau C, Saha S, Prakash S. Intranasal delivery of chitosan-siRNA nanoparticle formulation to the brain. Methods Mol Biol. 2014;1141:233–247. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-0363-4_15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Raja MAG, Katas H, Wen Jing T. Stability, intracellular delivery, and release of siRNA from chitosan nanoparticles using different cross-linkers. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0128963. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0128963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Malhotra M, Tomaro-Duchesneau C, Saha S, Prakash S. Intranasal delivery of chitosan-siRNA nanoparticle formulation to the brain. In: Jain KK, editor. Drug Delivery System. New York, NY: Springer; 2014. pp. 233–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yang X, Wu S, Wang Y, Li Y, Chang D, Luo Y, Ye S, Hou Z. Evaluation of self-assembled HCPT-loaded PEG-b-PLA nanoparticles by comparing with HCPT-loaded PLA nanoparticles. Nanoscale Res Lett. 2014;9:2408. doi: 10.1186/1556-276X-9-687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sun C, Wang X, Zheng Z, Chen D, Wang X, Shi F, Yu D, Wu H. A single dose of dexamethasone encapsulated in polyethylene glycol-coated polylactic acid nanoparticles attenuates cisplatin-induced hearing loss following round window membrane administration. Int J Nanomedicine. 2015;10:3567–3579. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S77912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rabanel J-M, Faivre J, Tehrani SF, Lalloz A, Hildgen P, Banquy X. Effect of the polymer architecture on the structural and biophysical properties of PEG-PLA nanoparticles. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2015;7:10374–10385. doi: 10.1021/acsami.5b01423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Diou O, Greco S, Beltran T, Lairez D, Authelin J-R, Bazile D. A method to quantify the affinity of cabazitaxel for PLA-PEG nanoparticles and investigate the influence of the nano-assembly structure on the drug/particle association. Pharm Res. 2015;32:3188–3200. doi: 10.1007/s11095-015-1696-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Asadi H, Rostamizadeh K, Salari D, Hamidi M. Preparation of biodegradable nanoparticles of tri-block PLA-PEG-PLA copolymer and determination of factors controlling the particle size using artificial neural network. J Microencapsul. 2011;28:406–416. doi: 10.3109/02652048.2011.576784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Xie Y, Yi Y, Hu X, Shangguan M, Wang L, Lu Y, Qi J, Wu W. Synchronous microencapsulation of multiple components in silymarin into PLGA nanoparticles by an emulsification/solvent evaporation method. Pharm Dev Technol. 2016;21:672–679. doi: 10.3109/10837450.2015.1045616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Xiong W, Peng L, Chen H, Li Q. Surface modification of MPEG-b-PCL-based nanoparticles via oxidative self-polymerization of dopamine for malignant melanoma therapy. Int J Nanomed. 2015;10:2985–2996. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S79605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhang R, Luo K, Yang J, Sima M, Sun Y, Janát-Amsbury MM, Kopeček J. Synthesis and evaluation of a backbone biodegradable multiblock HPMA copolymer nanocarrier for the systemic delivery of paclitaxel. J Control Release. 2013;166:66–74. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2012.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wang Q, Tang H, Wu P. Aqueous solutions of poly (ethylene oxide)-poly (N-isopropylacrylamide): Thermosensitive behavior and distinct multiple assembly processes. Langmuir. 2015;31:6497–6506. doi: 10.1021/acs.langmuir.5b00878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.James Priya H, John R, Alex A, Anoop KR. Smart polymers for the controlled delivery of drugs - a concise overview. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2014;4:120–127. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2014.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Trotta F, Dianzani C, Caldera F, Mognetti B, Cavalli R. The application of nanosponges to cancer drug delivery. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2014;11:931–941. doi: 10.1517/17425247.2014.911729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hu C-MJ, Fang RH, Wang K-C, Luk BT, Thamphiwatana S, Dehaini D, Nguyen P, Angsantikul P, Wen CH, Kroll AV, et al. Nanoparticle biointerfacing by platelet membrane cloaking. Nature. 2015;526:118–121. doi: 10.1038/nature15373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hu CM, Fang RH, Luk BT, Zhang L. Nanoparticle-detained toxins for safe and effective vaccination. Nat Nanotechnol. 2013;8:933–938. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2013.254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Miele E, Spinelli GP, Miele E, Tomao F, Tomao S. Albumin-bound formulation of paclitaxel (Abraxane ABI-007) in the treatment of breast cancer. Int J Nanomed. 2009;4:99–105. doi: 10.2147/ijn.s3061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hawkins MJ, Soon-Shiong P, Desai N. Protein nanoparticles as drug carriers in clinical medicine. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2008;60:876–885. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2007.08.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zheng Y-R, Suntharalingam K, Johnstone TC, Yoo H, Lin W, Brooks JG, Lippard SJ. Pt (IV) prodrugs designed to bind non-covalently to human serum albumin for drug delivery. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136:8790–8798. doi: 10.1021/ja5038269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Cirstea D, Hideshima T, Rodig S, Santo L, Pozzi S, Vallet S, Ikeda H, Perrone G, Gorgun G, Patel K, et al. Dual inhibition of akt/mammalian target of rapamycin pathway by nanoparticle albumin-bound-rapamycin and perifosine induces antitumor activity in multiple myeloma. Mol Cancer Ther. 2010;9:963–975. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-09-0763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Fu Q, Sun J, Zhang W, Sui X, Yan Z, He Z. Nanoparticle albumin-bound (NAB) technology is a promising method for anti-cancer drug delivery. Recent Patents Anticancer Drug Discov. 2009;4:262–272. doi: 10.2174/157489209789206869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Von Hoff DD, Mita MM, Ramanathan RK, Weiss GJ, Mita AC, LoRusso PM, Burris HA, III, Hart LL, Low SC, Parsons DM, et al. Phase I study of PSMA-targeted docetaxel-containing nanoparticle BIND-014 in patients with advanced solid tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2016;22:3157–3163. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-2548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zuckerman JE, Gritli I, Tolcher A, Heidel JD, Lim D, Morgan R, Chmielowski B, Ribas A, Davis ME, Yen Y. Correlating animal and human phase Ia/Ib clinical data with CALAA-01, a targeted, polymer-based nanoparticle containing siRNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:11449–11454. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1411393111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Buhleier E, Wehner W, Vögtle F. ‘Cascade’- and ‘nonskid-chain-like’ syntheses of molecular cavity topologies. Synthesis (Mass) 1978;155–158:1978. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Tomalia DA, Baker H, Dewald J, Hall M, Kallos G, Martin S, Roeck J, Ryder J, Smith P. A new class of polymers: Starburst-dendritic macromolecules. Polym J. 1985;17:117–132. doi: 10.1295/polymj.17.117. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Gillies ER, Fréchet JM. Dendrimers and dendritic polymers in drug delivery. Drug Discov Today. 2005;10:35–43. doi: 10.1016/S1359-6446(04)03276-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kesharwani P, Jain K, Jain NK. Dendrimer as nanocarrier for drug delivery. Prog Polym Sci. 2014;39:268–307. doi: 10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2013.07.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Khopade AJ, Caruso F, Tripathi P, Nagaich S, Jain NK. Effect of dendrimer on entrapment and release of bioactive from liposomes. Int J Pharm. 2002;232:157–162. doi: 10.1016/S0378-5173(01)00901-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Papagiannaros A, Dimas K, Papaioannou GT, Demetzos C. Doxorubicin-PAMAM dendrimer complex attached to liposomes: Cytotoxic studies against human cancer cell lines. Int J Pharm. 2005;302:29–38. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2005.05.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Purohit G, Sakthivel T, Florence AT. Interaction of cationic partial dendrimers with charged and neutral liposomes. Int J Pharm. 2001;214:71–76. doi: 10.1016/S0378-5173(00)00635-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Karadag M, Geyik C, Demirkol DO, Ertas FN, Timur S. Modified gold surfaces by 6-ferrocenyl)hexanethiol/dendrimer/gold nanoparticles as a platform for the mediated biosensing applications. Mater Sci Eng C. 2013;33:634–640. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2012.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Tao X, Yang Y-J, Liu S, Zheng Y-Z, Fu J, Chen J-F. Poly (amidoamine) dendrimer-grafted porous hollow silica nanoparticles for enhanced intracellular photodynamic therapy. Acta Biomater. 2013;9:6431–6438. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2013.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Yoshioka H, Suzuki M, Mugisawa M, Naitoh N, Sawada H. Synthesis and applications of novel fluorinated dendrimer-type copolymers by the use of fluoroalkanoyl peroxide as a key intermediate. J Colloid Interface Sci. 2007;308:4–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2006.12.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Zeng Y-L, Huang Y-F, Jiang J-H, Zhang X-B, Tang C-R, Shen G-L, Yu R-Q. Functionalization of multi-walled carbon nanotubes with poly (amidoamine) dendrimer for mediator-free glucose biosensor. Electrochem Commun. 2007;9:185–190. doi: 10.1016/j.elecom.2006.08.052. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Tang L, Zhu Y, Yang X, Li C. An enhanced biosensor for glutamate based on self-assembled carbon nanotubes and dendrimer-encapsulated platinum nanobiocomposites-doped polypyrrole film. Anal Chim Acta. 2007;597:145–150. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2007.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Prajapati RN, Tekade RK, Gupta U, Gajbhiye V, Jain NK. Dendimer-mediated solubilization, formulation development and in vitro-in vivo assessment of piroxicam. Mol Pharm. 2009;6:940–950. doi: 10.1021/mp8002489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Chauhan AS, Sridevi S, Chalasani KB, Jain AK, Jain SK, Jain NK, Diwan PV. Dendrimer-mediated transdermal delivery: Enhanced bioavailability of indomethacin. J Control Release. 2003;90:335–343. doi: 10.1016/S0168-3659(03)00200-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Quintana A, Raczka E, Piehler L, Lee I, Myc A, Majoros I, Patri AK, Thomas T, Mulé J, Baker JR., Jr Design and function of a dendrimer-based therapeutic nanodevice targeted to tumor cells through the folate receptor. Pharm Res. 2002;19:1310–1316. doi: 10.1023/A:1020398624602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Liu H, Wang Y, Wang M, Xiao J, Cheng Y. Fluorinated poly (propylenimine) dendrimers as gene vectors. Biomaterials. 2014;35:5407–5413. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2014.03.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Qiao Z, Shi X. Dendrimer-based molecular imaging contrast agents. Prog Polym Sci. 2015;44:1–27. doi: 10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2014.08.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Malik N, Evagorou EG, Duncan R. Dendrimer-platinate: A novel approach to cancer chemotherapy. Anticancer Drugs. 1999;10:767–776. doi: 10.1097/00001813-199909000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Kaminskas LM, Kelly BD, McLeod VM, Boyd BJ, Krippner GY, Williams ED, Porter CJ. Pharmacokinetics and tumor disposition of PEGylated, methotrexate conjugated poly-l-lysine dendrimers. Mol Pharm. 2009;6:1190–1204. doi: 10.1021/mp900049a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Al-Jamal KT, Al-Jamal WT, Wang JT-W, Rubio N, Buddle J, Gathercole D, Zloh M, Kostarelos K. Cationic poly-L-lysine dendrimer complexes doxorubicin and delays tumor growth in vitro and in vivo. ACS Nano. 2013;7:1905–1917. doi: 10.1021/nn305860k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Huang Z, Sengar RS, Nigam A, Abadjian MC, Potter DM, Grotjahn DB, Wiener EC. A fluorinated dendrimer-based nanotechnology platform: New contrast agents for high field imaging. Invest Radiol. 2010;45:641–654. doi: 10.1097/RLI.0b013e3181ee6e06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Yang J, Luo Y, Xu Y, Li J, Zhang Z, Wang H, Shen M, Shi X, Zhang G. Conjugation of iron oxide nanoparticles with RGD-modified dendrimers for targeted tumor MR imaging. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2015;7:5420–5428. doi: 10.1021/am508983n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Shi X, Wang SH, Van Antwerp ME, Chen X, Baker JR., Jr Targeting and detecting cancer cells using spontaneously formed multifunctional dendrimer-stabilized gold nanoparticles. Analyst (Lond) 2009;134:1373–1379. doi: 10.1039/b902199j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Thomas TP, Shukla R, Kotlyar A, Liang B, Ye JY, Norris TB, Baker JR., Jr Dendrimer-epidermal growth factor conjugate displays superagonist activity. Biomacromolecules. 2008;9:603–609. doi: 10.1021/bm701185p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Hill E, Shukla R, Park SS, Baker JR., Jr Synthetic PAMAM-RGD conjugates target and bind to odontoblast-like MDPC 23 cells and the predentin in tooth organ cultures. Bioconjug Chem. 2007;18:1756–1762. doi: 10.1021/bc0700234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Lesniak WG, Kariapper MS, Nair BM, Tan W, Hutson A, Balogh LP, Khan MK. Synthesis and characterization of PAMAM dendrimer-based multifunctional nanodevices for targeting alphavbeta3 integrins. Bioconjug Chem. 2007;18:1148–1154. doi: 10.1021/bc070008z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Thomas TP, Patri AK, Myc A, Myaing MT, Ye JY, Norris TB, Baker JR., Jr In vitro targeting of synthesized antibody-conjugated dendrimer nanoparticles. Biomacromolecules. 2004;5:2269–2274. doi: 10.1021/bm049704h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Chen H-T, Neerman MF, Parrish AR, Simanek EE. Cytotoxicity, hemolysis, and acute in vivo toxicity of dendrimers based on melamine, candidate vehicles for drug delivery. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:10044–10048. doi: 10.1021/ja048548j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Ahn HK, Jung M, Sym SJ, Shin DB, Kang SM, Kyung SY, Park JW, Jeong SH, Cho EK. A phase II trial of Cremorphor EL-free paclitaxel (Genexol-PM) and gemcitabine in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2014;74:277–282. doi: 10.1007/s00280-014-2498-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Park S, Healy KE. Nanoparticulate DNA packaging using terpolymers of poly (lysine-g-(lactide-b-ethylene glycol)) Bioconjug Chem. 2003;14:311–319. doi: 10.1021/bc025623b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Sun T-M, Du J-Z, Yan L-F, Mao H-Q, Wang J. Self-assembled biodegradable micellar nanoparticles of amphiphilic and cationic block copolymer for siRNA delivery. Biomaterials. 2008;29:4348–4355. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.07.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Gao Y, Zhou Y, Zhao L, Zhang C, Li Y, Li J, Li X, Liu Y. Enhanced antitumor efficacy by cyclic RGDyK-conjugated and paclitaxel-loaded pH-responsive polymeric micelles. Acta Biomater. 2015;23:127–135. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2015.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Kohori F, Sakai K, Aoyagi T, Yokoyama M, Sakurai Y, Okano T. Preparation and characterization of thermally responsive block copolymer micelles comprising poly (N-isopropylacrylamide-b-DL-lactide) J Control Release. 1998;55:87–98. doi: 10.1016/S0168-3659(98)00023-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.He C, Zhao C, Chen X, Guo Z, Zhuang X, Jing X. Novel pH- and temperature-responsive bock copolymers with tunable pH-responsive range. Macromol Rapid Commun. 2008;29:490–497. doi: 10.1002/marc.200700721. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Xu F, Yan T-T, Luo Y-L. Studies on micellization behavior of thermosensitive PNIPAAm-b-PLA amphiphilic block copolymers. J Nanosci Nanotechnol. 2012;12:2287–2291. doi: 10.1166/jnn.2012.5705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Zhao C, Zhuang X, He C, Chen X, Jing X. Synthesis of novel thermo-and pH-responsive poly (L-lysine)-based copolymer and its micellization in water. Macromol Rapid Commun. 2008;29:1810–1816. doi: 10.1002/marc.200800494. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Saravanakumar G, Lee J, Kim J, Kim WJ. Visible light-induced singlet oxygen-mediated intracellular disassembly of polymeric micelles co-loaded with a photosensitizer and an anticancer drug for enhanced photodynamic therapy. Chem Commun (Camb) 2015;51:9995–9998. doi: 10.1039/C5CC01937K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Bae J, Maurya A, Shariat-Madar Z, Murthy SN, Jo S. Novel redox-responsive amphiphilic copolymer micelles for drug delivery: Synthesis and characterization. AAPS J. 2015;17:1357–1368. doi: 10.1208/s12248-015-9800-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Liu Y, Li C, Wang HY, Zhang XZ, Zhuo RX. Synthesis of thermo- and pH-sensitive polyion complex micelles for fluorescent imaging. Chemistry. 2012;18:2297–2304. doi: 10.1002/chem.201102704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Johnson RP, Jeong YI, John JV, Chung CW, Kang DH, Selvaraj M, Suh H, Kim I. Dual stimuli-responsive poly (N-isopropylacrylamide)-b-poly (L-histidine) chimeric materials for the controlled delivery of doxorubicin into liver carcinoma. Biomacromolecules. 2013;14:1434–1443. doi: 10.1021/bm400089m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Zhou F, Zheng B, Zhang Y, Wu Y, Wang H, Chang J. Construction of near-infrared light-triggered reactive oxygen species-sensitive (UCN/SiO2-RB + DOX)@PPADT nanoparticles for simultaneous chemotherapy and photodynamic therapy. Nanotechnology. 2016;27:235601. doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/27/23/235601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Wu HQ, Wang CC. Biodegradable smart nanogels: A new platform for targeting drug delivery and biomedical diagnostics. Langmuir. 2016;32:6211–6225. doi: 10.1021/acs.langmuir.6b00842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Moan J, Peng Q. An outline of the hundred-year history of PDT. Anticancer Res. 2003;23A:3591–3600. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Castano AP, Mroz P, Hamblin MR. Photodynamic therapy and anti-tumour immunity. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:535–545. doi: 10.1038/nrc1894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Krammer B. Vascular effects of photodynamic therapy. Anticancer Res. 2001;21B:4271–4277. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Monge-Fuentes V, Muehlmann LA, de Azevedo RB. Perspectives on the application of nanotechnology in photodynamic therapy for the treatment of melanoma. Nano Rev. 2014;5:24381–24395. doi: 10.3402/nano.v5.24381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Wang C, Cheng L, Liu Z. Upconversion nanoparticles for photodynamic therapy and other cancer therapeutics. Theranostics. 2013;3:317–330. doi: 10.7150/thno.5284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Marin E, Briceño MI, Caballero-George C. Critical evaluation of biodegradable polymers used in nanodrugs. Int J Nanomed. 2013;8:3071–3090. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S47186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Ma X, Wang X, Zhou M, Fei H. A mitochondria-targeting gold-peptide nanoassembly for enhanced cancer-cell killing. Adv Healthc Mater. 2013;2:1638–1643. doi: 10.1002/adhm.201300037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Jung HS, Han J, Lee J-H, Lee JH, Choi JM, Kweon HS, Han JH, Kim JH, Byun KM, Jung JH, et al. Enhanced NIR radiation-triggered hyperthermia by mitochondrial targeting. J Am Chem Soc. 2015;137:3017–3023. doi: 10.1021/ja5122809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Biswas S, Kumari P, Lakhani PM, Ghosh B. Recent advances in polymeric micelles for anti-cancer drug delivery. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2016;83:184–202. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2015.12.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Dewit MA, Gillies ER. A cascade biodegradable polymer based on alternating cyclization and elimination reactions. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:18327–18334. doi: 10.1021/ja905343x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Deming TJ. Synthetic polypeptides for biomedical applications. Prog Polym Sci. 2007;32:858–875. doi: 10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2007.05.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Sun J, Chen X, Lu T, Liu S, Tian H, Guo Z, Jing X. Formation of reversible shell cross-linked micelles from the biodegradable amphiphilic diblock copolymer poly (L-cysteine)-block-poly (L-lactide) Langmuir. 2008;24:10099–10106. doi: 10.1021/la8013877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Dourado ER, Pizzorno BS, Motta LM, Simao RA, Leite LF. Analysis of asphaltic binders modified with PPA by surface techniques. J Microsc. 2014;254:122–128. doi: 10.1111/jmi.12123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Kim IB, Han MH, Phillips RL, Samanta B, Rotello VM, Zhang ZJ, Bunz UH. Nano-conjugate fluorescence probe for the discrimination of phosphate and pyrophosphate. Chemistry. 2009;15:449–456. doi: 10.1002/chem.200801403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Chen PC, Mwakwari SC, Oyelere AK. Gold nanoparticles: From nanomedicine to nanosensing. Nanotechnol Sci Appl. 2008;1:45–65. doi: 10.2147/NSA.S3707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Huang H-C, Barua S, Sharma G, Dey SK, Rege K. Inorganic nanoparticles for cancer imaging and therapy. J Control Release. 2011;155:344–357. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2011.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Namiki Y, Fuchigami T, Tada N, Kawamura R, Matsunuma S, Kitamoto Y, Nakagawa M. Nanomedicine for cancer: Lipid-based nanostructures for drug delivery and monitoring. Acc Chem Res. 2011;44:1080–1093. doi: 10.1021/ar200011r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Libutti SK, Paciotti GF, Byrnes AA, Alexander HR, Jr, Gannon WE, Walker M, Seidel GD, Yuldasheva N, Tamarkin L. Phase I and pharmacokinetic studies of CYT-6091, a novel PEGylated colloidal gold-rhTNF nanomedicine. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:6139–6149. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-0978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Benezra M, Penate-Medina O, Zanzonico PB, Schaer D, Ow H, Burns A, DeStanchina E, Longo V, Herz E, Iyer S, et al. Multimodal silica nanoparticles are effective cancer-targeted probes in a model of human melanoma. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:2768–2780. doi: 10.1172/JCI45600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Sanchez C, Belleville P, Popall M, Nicole L. Applications of advanced hybrid organic-inorganic nanomaterials: From laboratory to market. Chem Soc Rev. 2011;40:696–753. doi: 10.1039/c0cs00136h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Jain RK, Stylianopoulos T. Delivering nanomedicine to solid tumors. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2010;7:653–664. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2010.139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Kamaly N, Yameen B, Wu J, Farokhzad OC. Degradable controlled-release polymers and polymeric nanoparticles: Mechanisms of controlling drug release. Chem Rev. 2016;116:2602–2663. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Holback H, Yeo Y. Intratumoral drug delivery with nanoparticulate carriers. Pharm Res. 2011;28:1819–1830. doi: 10.1007/s11095-010-0360-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Jain RK, Martin JD, Stylianopoulos T. The role of mechanical forces in tumor growth and therapy. Annu Rev Biomed Eng. 2014;16:321–346. doi: 10.1146/annurev-bioeng-071813-105259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Kim KY. Nanotechnology platforms and physiological challenges for cancer therapeutics. Nanomedicine (Lond) 2007;3:103–110. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2006.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Liu D, He C, Wang AZ, Lin W. Application of liposomal technologies for delivery of platinum analogs in oncology. Int J Nanomed. 2013;8:3309–3319. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S38354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Moghimi SM, Symonds P, Murray JC, Hunter AC, Debska G, Szewczyk A. A two-stage poly (ethylenimine)-mediated cytotoxicity: Implications for gene transfer/therapy. Mol Ther. 2005;11:990–995. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2005.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Lü J-M, Wang X, Marin-Muller C, Wang H, Lin PH, Yao Q, Chen C. Current advances in research and clinical applications of PLGA-based nanotechnology. Expert Rev Mol Diagn. 2009;9:325–341. doi: 10.1586/erm.09.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Kim J, Dadsetan M, Ameenuddin S, Windebank AJ, Yaszemski MJ, Lu L. In vivo biodegradation and biocompatibility of PEG/sebacic acid-based hydrogels using a cage implant system. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2010;95:191–197. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.32810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Nicolete R, dos Santos DF, Faccioli LH. The uptake of PLGA micro or nanoparticles by macrophages provokes distinct in vitro inflammatory response. Int Immunopharmacol. 2011;11:1557–1563. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2011.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Ceonzo K, Gaynor A, Shaffer L, Kojima K, Vacanti CA, Stahl GL. Polyglycolic acid-induced inflammation: Role of hydrolysis and resulting complement activation. Tissue Eng. 2006;12:301–308. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.12.301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Madaan K, Kumar S, Poonia N, Lather V, Pandita D. Dendrimers in drug delivery and targeting: Drug-dendrimer interactions and toxicity issues. J Pharm Bioallied Sci. 2014;6:139–150. doi: 10.4103/0975-7406.130965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Jain K, Kesharwani P, Gupta U, Jain NK. Dendrimer toxicity: Let's meet the challenge. Int J Pharm. 2010;394:122–142. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2010.04.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Ma Y, Mou Q, Wang D, Zhu X, Yan D. Dendritic polymers for theranostics. Theranostics. 2016;6:930–947. doi: 10.7150/thno.14855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Dreaden EC, Austin LA, Mackey MA, El-Sayed MA. Size matters: Gold nanoparticles in targeted cancer drug delivery. Ther Deliv. 2012;3:457–478. doi: 10.4155/tde.12.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Gu Y, Zhong Y, Meng F, Cheng R, Deng C, Zhong Z. Acetal-linked paclitaxel prodrug micellar nanoparticles as a versatile and potent platform for cancer therapy. Biomacromolecules. 2013;14:2772–2780. doi: 10.1021/bm400615n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Idris NM, Gnanasammandhan MK, Zhang J, Ho PC, Mahendran R, Zhang Y. In vivo photodynamic therapy using upconversion nanoparticles as remote-controlled nanotransducers. Nat Med. 2012;18:1580–1585. doi: 10.1038/nm.2933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Yang Y, Shao Q, Deng R, Wang C, Teng X, Cheng K, Cheng Z, Huang L, Liu Z, Liu X, et al. In vitro and in vivo uncaging and bioluminescence imaging by using photocaged upconversion nanoparticles. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2012;51:3125–3129. doi: 10.1002/anie.201107919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Chen H, Yang Z, Ding C, Chu L, Zhang Y, Terry K, Liu H, Shen Q, Zhou J. Fragment-based drug design and identification of HJC0123, a novel orally bioavailable STAT3 inhibitor for cancer therapy. Eur J Med Chem. 2013;62:498–507. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2013.01.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Langer R, Folkman J. Polymers for the sustained release of proteins and other macromolecules. Nature. 1976;263:797–800. doi: 10.1038/263797a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Lee CC, MacKay JA, Fréchet JMJ, Szoka FC. Designing dendrimers for biological applications. Nat Biotechnol. 2005;23:1517–1526. doi: 10.1038/nbt1171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Torchilin VP. Immunoliposomes and PEGylated immunoliposomes: Possible use for targeted delivery of imaging agents. Immunomethods. 1994;4:244–258. doi: 10.1006/immu.1994.1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Immordino ML, Dosio F, Cattel L. Stealth liposomes: Review of the basic science, rationale, and clinical applications, existing and potential. Int J Nanomed. 2006;1:297–315. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Batist G, Ramakrishnan G, Rao CS, Chandrasekharan A, Gutheil J, Guthrie T, Shah P, Khojasteh A, Nair MK, Hoelzer K, et al. Reduced cardiotoxicity and preserved antitumor efficacy of liposome-encapsulated doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide compared with conventional doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide in a randomized, multicenter trial of metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:1444–1454. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.5.1444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Silverman JA, Deitcher SR. Marqibo® (vincristine sulfate liposome injection) improves the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of vincristine. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2013;71:555–564. doi: 10.1007/s00280-012-2042-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157.Verma J, Lal S, Van Noorden CJ. Inorganic nanoparticles for the theranostics of cancer. Eur J Nanomed. 2015;7:271–287. doi: 10.1515/ejnm-2015-0024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 158.Kim MT, Chen Y, Marhoul J, Jacobson F. Statistical modeling of the drug load distribution on trastuzumab emtansine (Kadcyla), a lysine-linked antibody drug conjugate. Bioconjug Chem. 2014;25:1223–1232. doi: 10.1021/bc5000109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]