Abstract

Purpose

African American women with breast cancer have higher cancer-specific and overall mortality rates. Obesity is common among African American women and contributes to breast cancer progression and numerous chronic conditions. Weight loss interventions among breast cancer survivors positively affect weight, behavior, biomarkers, and psychosocial outcomes, yet few target African Americans. This article examines the effects of Moving Forward, a weight loss intervention for African American breast cancer survivors (AABCS) on weight, body composition, and behavior.

Patients and Methods

Early-stage (I-III) AABCS were randomly assigned to a 6-month interventionist-guided (n = 125) or self-guided (n = 121) weight loss program supporting behavioral changes to promote a 5% weight loss. Anthropometric, body composition, and behavioral data were collected at baseline, postintervention (6 months), and follow-up (12 months). Descriptive statistics and mixed models analyses assessed differences between groups over time.

Results

Mean (± standard deviation) age, and body mass index were 57.5 (± 10.1) years and 36.1 (± 6.2) kg/m2, respectively, and 82% had stage I or II breast cancer. Both groups lost weight. Mean and percentage of weight loss were greater in the guided versus self-guided group (at 6 months: 3.5 kg v 1.3kg; P < .001; 3.6% v 1.4%; P < .001, respectively; at 12 months: 2.7 kg v 1.6 kg; P < .05; 2.6% v 1.6%; P < .05, respectively); 44% in the guided group and 19% in the self-guided group met the 5% goal. Body composition and behavioral changes were also greater in the interventionist-guided group at both time points.

Conclusion

The study supports the efficacy of a community-based interventionist-guided weight loss program targeting AABCS. Although mean weight loss did not reach the targeted 5%, the mean loss of > 3% at 6 months is associated with improved health outcomes. Affordable, accessible health promotion programs represent a critical resource for AABCS.

INTRODUCTION

Breast cancer mortality rates are highest for African American (AA) women, even after controlling for demographic, diagnostic, and treatment-related factors.1,2 All-cause mortality rates are also higher for AA breast cancer survivors (AABCS) due to high rates of comorbid conditions, such as diabetes and hypertension.3-5 Ninety-two percent of white women will survive at least 5 years after diagnosis, compared with 81% of AA women. These differences are not easily explained and involve multiple issues; obesity and lifestyle factors are important contributors.6,7 Evidence from a 2014 meta-analysis of 82 studies found that prediagnosis and postdiagnosis obesity was associated with higher breast cancer–specific and overall mortality; overweight was associated with higher overall mortality.8 Over 82% of AA women are classified as overweight/obese, and 56.6% have obesity.9 The likelihood of an AA woman being overweight or obese when diagnosed with breast cancer is high. Women often gain weight in the years after their diagnosis, with some data suggesting AA women gain twice as much weight as white women.10-13

Weight loss intervention trials with breast cancer survivors report improvements in diet and physical activity, biomarkers of inflammation and insulin resistance, and quality of life, but inclusion of AABCS is limited.14,15 Considering the high rates of mortality, comorbidities, and obesity among AABCS, weight loss is an important priority. However, due to a complex interaction of environmental, societal, and policy-related factors, weight management may be uniquely challenging for many AAs in the United States, particularly those with limited income.16-18 AA women are under-represented in weight loss trials, and if they do participate, they are more apt to drop out and lose less weight.19,20 The feasibility of weight loss interventions for AABCS is established; however, previous studies were underpowered and none examined body composition.21-23 We report the effects of a 6-month interventionist-guided versus a self-guided weight loss program on anthropometric, body composition, and behavioral outcomes in overweight/obese AABCS postintervention and at the 12-month follow-up.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Study Design

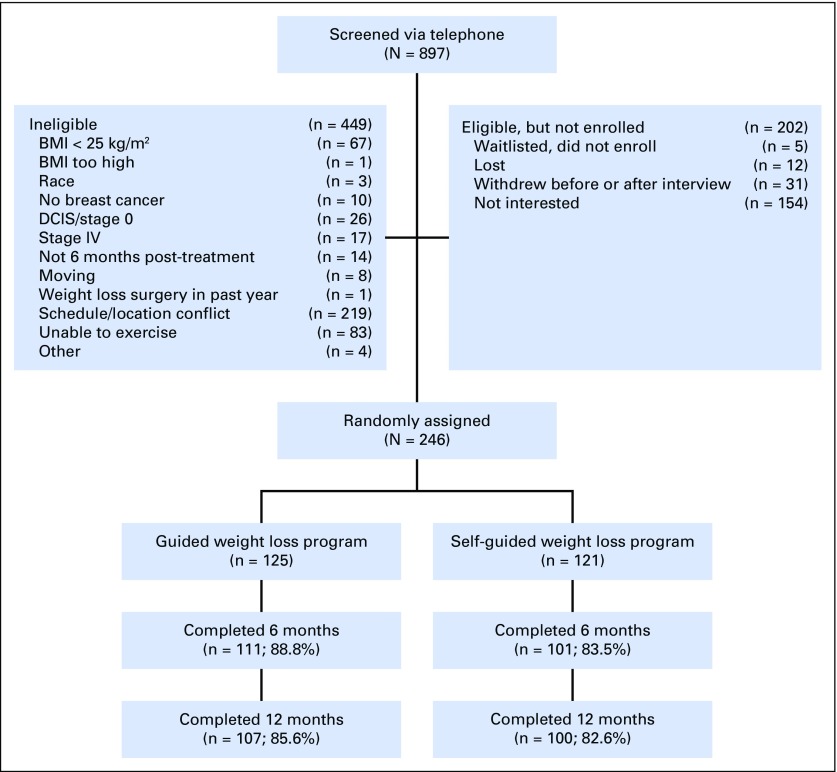

Moving Forward was a community-based, randomized, weight loss intervention trial with 246 overweight/obese AABCS (Fig 1). Survivors were recruited between September 2011 and September 2014. Detailed methods were published previously.24

Fig 1.

Flow of participants through the Moving Forward Study. BMI, body mass index.

Patient Population

Eligible participants were AABCS (stages I-III), were ≥ 18 years of age, had a body mass index (BMI) of ≥ 25 kg/m2, had completed cancer treatment at least 6 months before recruitment (hormonal therapy allowed), were physically able to participate in a moderate physical activity program per health-care provider approval, and were agreeable to study procedures. Women were excluded if they were pregnant or planning to become pregnant during the study, taking prescription weight loss medication, or planning weight loss surgery in the coming year. Recruitment involved direct contact by letter and phone using hospital cancer registry contact information from three Chicago-area academic cancer centers and community-based efforts, including referrals from oncologists, flyers, social media, and presentations. The respective institutional review boards approved all study procedures, and each participant provided written informed consent. Women were randomly assigned using a random digit generator after the baseline interview.

Interventions

Participants were randomly assigned to either the 6-month Moving Forward Interventionist-Guided program (MFG) or the Moving Forward Self-Guided program (SG). Program goals for the 6-month period were identical: 5% weight loss achieved by decreased caloric intake (−500 kcal daily), increased fruit and vegetable consumption, and increased physical activity (minimum ≥ 150 minutes per week) on the basis of the American Cancer Society cancer survivor guidelines.25 The cognitive-behavioral weight loss intervention was grounded within a socioecological model26,27 to promote self-efficacy, social support, and perceived access to community-based healthy eating and activity resources.24,28,29 To enhance its cultural relevance, the intervention was guided by the framework of Kreuter et al30 using strategies that were (1) peripheral (logo, recruitment materials, exercise music); (2) evidential (evidence on health impact of breast cancer, obesity, comorbidities in AA community); (3) constituent (intervention was developed in collaboration with AABCS; led by individuals with whom participants could identify); and (4) sociocultural (honored values, such as the woman’s central role in families, the importance of religion and worship and how it affects health perspectives, heavier body image ideals, and traditional importance of food).

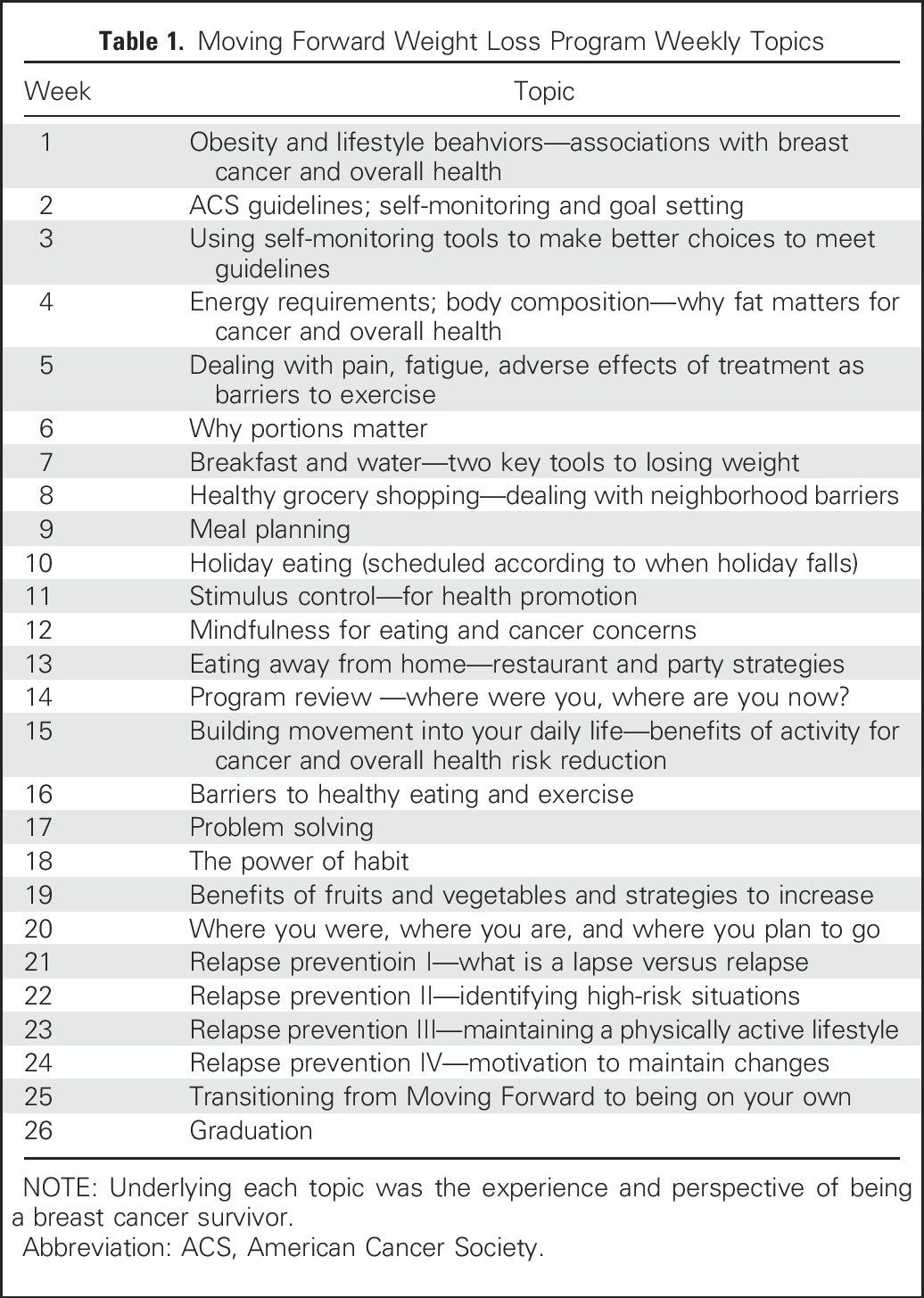

MFG included twice-weekly in-person classes with supervised exercise and twice-weekly text messaging targeting enhanced self-efficacy, social support, and access to health promotion resources. Weekly Class 1 (90 minutes) began with weighing in and supervised exercise, followed by 45- to 60-minute interactive learning modules (Table 1) that addressed knowledge (eg, relationship between obesity and cancer/health), attitudes (eg, cancer/health fatalism), and cognitive behavioral strategies (eg, self-monitoring, goal setting). Participants received a program binder with hand-outs, recipes, and other supportive materials as a resource for review, reinforcement, and reminders. Weekly Class 2 (60 minutes) was a stand-alone 60-minute exercise class that included aerobic and resistance exercise training. Classes were held in the evening (6-8 pm) at neighborhood Chicago Park District facilities and were led by a study-trained community nutritionist and exercise trainer. SG participants also received the program binder, but no classes or text messaging. They met once with a nonintervention staff member to receive and review program materials. At 6 months, both groups received monthly newsletters with reinforcing information from the curriculum, news of local healthy eating and exercise resources, and participant testimonials. The choice of the SG comparator was based on strong feedback from our study advisory committee (comprising disparities researchers and AABCS), referring oncologists, and community stakeholders. A conventional usual-care or even an attention placebo group would necessitate the withholding of lifestyle information with known benefits on health. The committee deemed this unethical and further surmised that accrual for this community-based intervention would be nearly impossible. Budgetary and time constraints precluded the use of a wait-list control group.

Table 1.

Moving Forward Weight Loss Program Weekly Topics

Measurements

Anthropometric, body composition, and behavioral outcomes were measured at baseline, 6 months, and 12 months. Height (baseline only) was measured to the nearest 0.1 cm using a portable stadiometer (Seca, Chino, CA). Weight was measured to the nearest 0.1 kg using a digital scale (Tanita; Arlington Heights, IL), with participants wearing light clothes without shoes. Two measurements for height and weight were taken; a discrepancy of more than 0.5 cm for height or 0.2 kg for weight resulted in a third measurement. The mean of the two most closely aligned measurements were used to calculate BMI (weight [kg]/height [m2]). Waist and hip circumference were measured with participants standing without outer garments and with empty pockets. Waist circumference was measured to the nearest 0.1 cm at the umbilicus during gentle expiration. Hip circumference was recorded as the maximum circumference over the buttocks. Two measurements were taken, with a discrepancy of more than 1 cm resulting in a third measurement. The mean of the two measurements most closely aligned were used for analyses. Body composition, specifically, body fat and lean tissue mass, was measured by dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry using the ilunar device (software version 13.6; GE, Chicago, IL).31 Dietary intake assessment was interviewer administered using the Block 2005 Food Frequency Questionnaire, which has been validated with diverse populations.32,33 Results were procured from Nutrition Quest to determine consumption of energy, fruits and vegetables, fat, fiber, meat, and added sugars. Physical activity, including the frequency and duration of moderate and vigorous activity over the last 6 months, was measured by the Modified Activity Questionnaire.34 Medical record abstraction and self-report questionnaires provided information on comorbidities, breast cancer diagnosis, and treatment information.

Statistical Analyses

Descriptive statistics were reported for all outcomes of interest at baseline, including anthropometric and behavioral outcomes. Outcomes for MFG and SG groups at various times were assessed using a linear mixed effects model, with random effects terms to account for the correlation in repeated measures (including baseline) from a single woman. Interaction terms were included in the linear model to account for differences in trend across time between groups. A compound symmetry covariance structure was assumed for the correlation between outcomes from the same woman across time.35,36 For each outcome, adjusted differences in mean using the linear model, as well as estimated standard errors for the adjusted differences, were reported. At each of the 6-month and the 12-month follow-ups, the statistical significance of the difference between outcomes between the MFG and SG terms was assessed by the P value of the appropriate interaction term in the linear model. Difference across time within the SG, as well as within the MFG, were compared using appropriate contrast terms. An overall significance level of .05 was used, with multiplicity corrections wherever necessary. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS software version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Participants

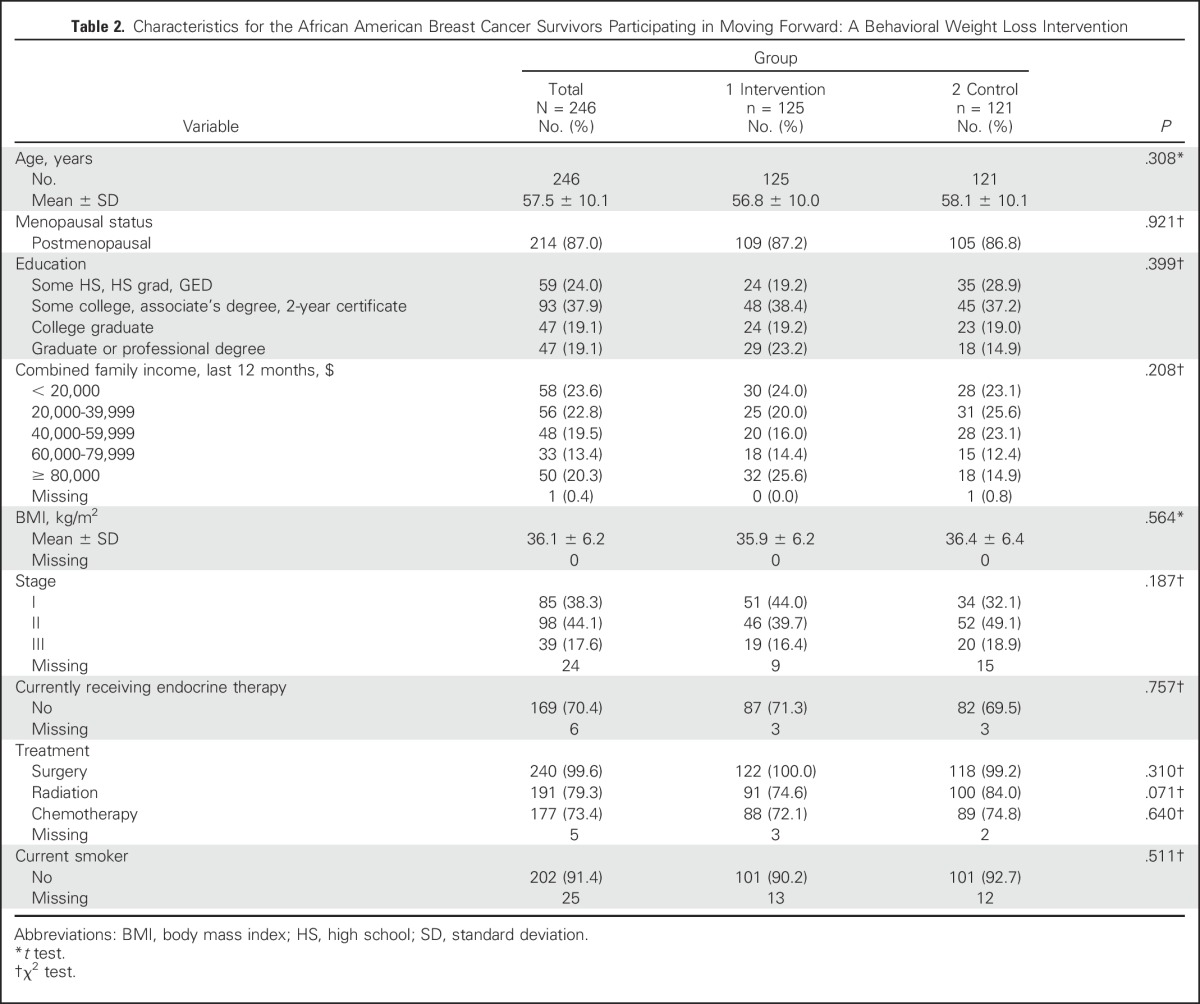

A total of 897 women were screened, resulting in 246 randomly assigned to MFG (n = 125) or SG (n = 121; Table 2; Fig 1). Recruitment letters on the basis of tumor registry contact information were the most successful recruitment mode, followed by community event presentations. Retention was 86% (n = 212) at 6 months and 84% (n = 206) at 12 months. Groups were comparable at baseline. Mean (standard deviation [SD]) age was 57.5 (10.1) years, mean (SD) BMI was 36.1 (6.2) kg/m2, and 82% were diagnosed with stage I or II disease; 58.1% reported having hypertension, and 23.4% reported having diabetes. Participants were a mean of 6.7 years from diagnosis and reflected a broad range of education and income levels.

Table 2.

Characteristics for the African American Breast Cancer Survivors Participating in Moving Forward: A Behavioral Weight Loss Intervention

MFG Intervention Attendance

Participants attended an average of 55% of the 48 classes offered. Interestingly, if women attended the first class, their mean attendance increased to 61%. Average attendance at the first weekly class, which included education, support, and supervised exercise, was higher (75%) than that for the second class (50%), which included supervised exercise only.

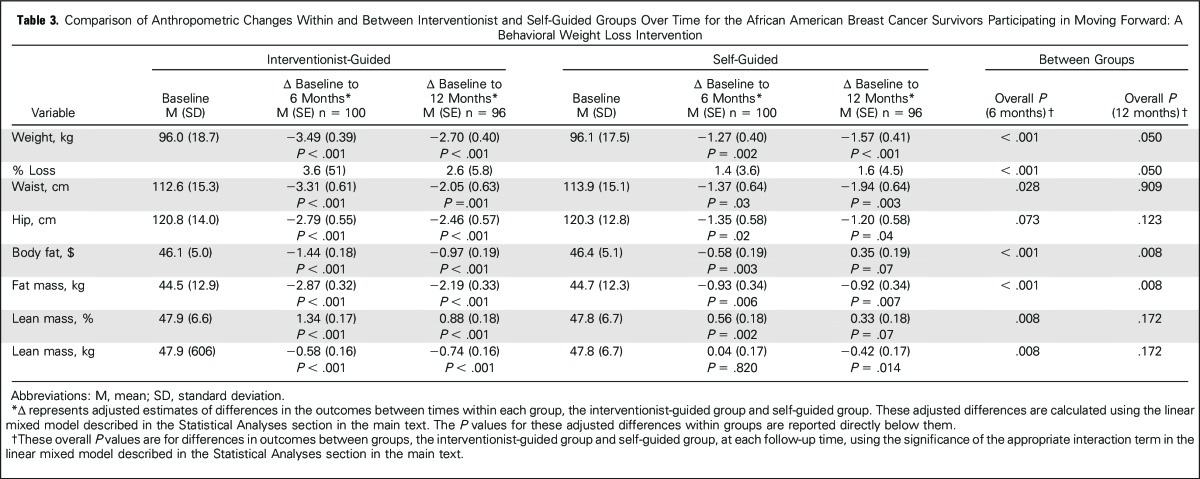

Anthropometric Outcomes

Within both groups, weight, waist and hip circumferences, and body fat were significantly reduced at both time points (Table 3). Lean mass decreased slightly, but relative to total mass, the percentage of lean mass increased. Greater attendance in MFG was associated with greater weight losses (P = .019). Smoking was not associated with weight loss. Between groups, MFG demonstrated significantly greater improvements than SG for weight and percentage of weight loss (−3.49 kg v −1.27 kg; P < .001; 3.6% v 1.4%, respectively), waist circumference (−3.31 cm v −1.37 cm; P = .028), percentage of body fat (−1.44 v −0.58; P < .001), fat mass (−2.87 kg v −0.93 kg; P < .001), and percentage of lean mass (01.34 v 0.56; P = .008) at 6 months, and for weight (−2.70 kg v −1.57 kg; P < .05), percentage of body fat (−0.97 v 0.35; P = .008), and fat mass (−2.19 kg v −0.92 kg; P = .008) at 12 months. In terms of clinically meaningful weight losses, 68.2% of MFG participants lost ≥ 3% compared with 44.4% of SG; 44.3% of MFG and 19% of SG lost ≥ 5% (P < .05). MFG showed greater losses of lean mass (kg) compared with SG at both time points, but relative lean mass increased more in MFG. No between-group differences were noted for hip circumference.

Table 3.

Comparison of Anthropometric Changes Within and Between Interventionist and Self-Guided Groups Over Time for the African American Breast Cancer Survivors Participating in Moving Forward: A Behavioral Weight Loss Intervention

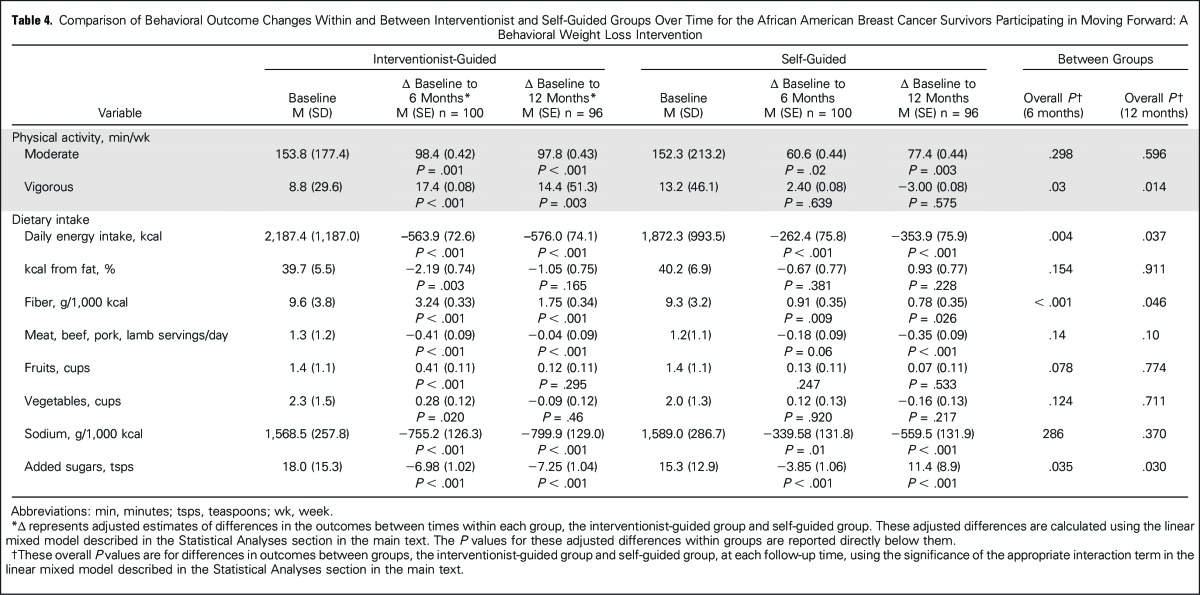

Behavioral Outcomes

Within-group improvements were significant for moderate activity, daily energy intake, fiber, sodium, and added sugars in both groups at 6 and 12 months (Table 4; P < .05). MFG participants also showed improvements for percentage of calories from fat, fruits, and vegetables at 6 months and for vigorous activity and meat at 6 and 12 months (P < .01). SG participants had decreased meat intake at 12 months only (P < .001), but no changes were observed in vigorous activity, fruit intake, or vegetable intake at either time point. Between groups, MFG showed greater beneficial changes for vigorous activity, daily energy intake, fiber intake, and added sugars at both time points (P < .05). More MFG compared with SG participants (64.9% v 44.6% at 6 months; P = .003; 65.4% v 52.0% at 12 months; P < .05) engaged in > 150 minutes of weekly physical activity, a benchmark associated with improved health outcomes.37 Groups did not differ on percentage of calories from fat, fruits, vegetables, or meat at any point. No adverse events were reported.

Table 4.

Comparison of Behavioral Outcome Changes Within and Between Interventionist and Self-Guided Groups Over Time for the African American Breast Cancer Survivors Participating in Moving Forward: A Behavioral Weight Loss Intervention

In summary, to our knowledge, the Moving Forward study is the first fully powered intervention trial to examine a targeted weight loss intervention’s effects on anthropometrics, body composition, and behavioral outcomes among AABCS. By design, both groups showed positive changes. However, MFG demonstrated significantly greater improvements for weight, percentage of weight loss, waist circumference, body fat and lean mass, vigorous activity, daily energy intake, fiber, sodium, and added sugars postintervention; benefits remained for weight, body fat and percentage of lean body mass, vigorous activity, fiber, and added sugars at the 12-month follow-up.

Overweight and obesity in breast cancer survivors is associated with increased risk of all-cause mortality, breast cancer mortality, recurrence, and comorbidities. Weight management is particularly crucial for AABCS, given the high rates of obesity-related comorbidities. For ethical reasons, Moving Forward was intended to induce weight loss in both study groups, However, MFG participants lost more than twice as much as SG participants. This level of weight loss is superior to that reported in the few studies conducted with AABCS and in most trials with AA women in the general population.21,23,38,39 For example, two 12-week pilot intervention studies with AABCS reported mean weight losses of below 1 kg.21,23 In keeping with the literature showing racial differences in weight loss in noncancer populations, mean weight loss in our study was lower than that reported in many trials with white breast cancer survivors.15,40-42

Currently, weight loss benchmarks associated with reduction in breast cancer mortality or recurrence are not established.14 However, in 2013, an expert panel formed by the National Institutes of Health provided graded evidence statements noting that weight loss beginning at 3% (for glycemic measures and triglycerides) and 5% (for blood pressure, HDL and LDL cholesterol) should be considered clinically meaningful.37,43,44 It is encouraging that mean percentage of weight loss for MFG (3.6%) met the lower benchmark and that 44% of participants lost at least 5% (compared with 19% of SG participants). To encourage larger weight losses in future trials, emphasis and consideration should be given to the recommended energy prescription. A 2014 study examining differential weight loss among white and AA women receiving identical interventions found that despite equivalent adherence between groups, AA women lost an average of 3.6 kg less than white women.45 The authors concluded that the lower energy requirement observed among AA women suggested that they required a lower energy prescription to support weight losses equivalent to that of white participants. Per the Moving Forward intervention prescription, the MFG demonstrated a mean caloric deficit of over 500 kcal and a significant increase in moderate and vigorous physical activity. Although greater deficits would lead to greater weight losses, difficulty maintaining the changes should be balanced with the advantages of smaller lifestyle changes that may be more easily maintained.

Despite the modest weight loss, both groups showed significant improvements in body fat (% and kg) and central adiposity. This is the first study to examine body composition changes in a weight loss trial with AABCS using dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry, a more precise methodology. These findings have important implications for potential biologic pathways associated with breast cancer recurrence and comorbidities. Reductions in weight, body fat, and waist circumference reduce inflammation and insulin resistance, which are associated with reduced risk of breast cancer recurrence and multiple chronic health conditions.14,15 Compared with available data primarily from white breast cancer survivors, our study showed smaller changes, likely relative to the amount of weight lost.46-48 Future studies will examine the associations between body composition changes and biomarkers of overall health and breast cancer recurrence in AABCS.42 This is a significant limitation in the current literature on weight loss in AAs in the general population as well.20 We also observed small lean mass (kg) losses in the MFG group. Weight reduction by caloric restriction alone often leads to lean mass losses that can be associated with sarcopenia and unfavorable metabolic profiles.46 Integrating resistance exercise/strength training into weight management interventions can preclude such losses. Importantly we did not detect any sarcopenia at the beginning and end of our trial. In fact, we observed increases in percentage of lean mass, with greater improvements noted for MFG. This is likely owing to the twice-weekly exercise classes that included at least 20 minutes of strength training. Although most participants had little experience with strength training, they were interested in understanding why such training mattered for health and quality of life. Participants were also eager to monitor their progress. Informal strength assessments were conducted at the beginning, midway through, and at the end of the 6 months. These assessments provided motivation for maintaining and/or increasing efforts.

Within-group anthropometric and behavioral improvements remained at the 12-month follow-up, but most attenuated compared with those observed immediately postintervention for MFG participants. These findings highlight the need for ongoing support and accountability during the maintenance phase. Although we provided informational newsletters to all participants (MFG and SG), MFG participants were accustomed to class participation and support. These results underscore the need for and interest in health promotion resources among AABCS, which can be accessed easily and affordably. Interestingly, SG participants continued to show subtle improvements from baseline to the 12-month follow-up for many outcomes. Conceivably, the minimal contact provided via newsletters promoted behavioral changes that led to continued, albeit small, weight reductions.

Strengths of the current study include the randomized design, a focus on an understudied group with a history of disparate health outcomes, recruitment of a diverse study sample (age, education, income), a culturally informed intervention developed with the targeted population, high retention, and the inclusion of body composition measurements. Although all study measures were well validated, diet and physical activity data were based on self-report. Additional limitations included selection bias, lack of a true control group, and limited generalizability because only AABCS were engaged. Also, because we did not expect changes in the SG group, we did not collect data on their engagement with study materials.

In conclusion, the Moving Forward weight loss trial supports the efficacy of an interventionist-guided and a self-guided weight loss program for AABCS. However, the interventionist-guided program led to greater weight loss than other studies involving AABCS, and a subset met the intended goal of 5%. Notably, Moving Forward was conducted collaboratively within public recreation system facilities. As the cancer survivor population grows, ongoing community-based programs that support healthy lifestyles are required. This is particularly true for AABCS, who have high rates of obesity, often live in resource-poor neighborhoods, and face multiple barriers to healthy lifestyles.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We are grateful to all of the participants who devoted their time and energy to this trial in the hopes of making a difference for other African American women. We thank the Chicago Park District for accommodating the program and providing space and discounted memberships. We are also grateful to the many health care providers and community-based organizations that welcomed the study team to post flyers or attend their events to share information about breast cancer and the Moving Forward trial. Thanks are also owed to Erin Harmann, who provided administrative support for the manuscript.

Footnotes

Supported by funding to M.R.S. from the National Cancer Institute (CA154406 and CA154406S).

Clinical trial information: NCT02482506.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Melinda Stolley, Patricia Sheean, Ben Gerber, Claudia Arroyo, Giamila Fantuzzi, Angela Odoms-Young, Lisa Sharp

Financial support: Patricia Sheean

Administrative support: Claudia Arroyo, Lauren Matthews, Roxanne Dakers, Katya Seligman

Provision of study materials or patients: Ben Gerber, Desmona Strahan, Cynthia Carridine-Andrews, Susan Hong, Kent Hoskins, Virginia Kaklamani

Collection and assembly of data: Melinda Stolley, Patricia Sheean, Claudia Arroyo, Desmona Strahan, Roxanne Dakers, Cynthia Carridine-Andrews, Katya Seligman, Sparkle Springfield, Susan Hong, Kent Hoskins, Virginia Kaklamani

Data analysis and interpretation: Melinda Stolley, Patricia Sheean, Linda Schiffer, Anjishnu Banerjee, Alexis Visotcky, Lauren Matthews, Lisa Sharp

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Efficacy of a Weight Loss Intervention for African American Breast Cancer Survivors

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/jco/site/ifc.

Melinda Stolley

No relationship to disclose

Patricia Sheean

No relationship to disclose

Ben Gerber

No relationship to disclose

Claudia Arroyo

No relationship to disclose

Linda Schiffer

No relationship to disclose

Anjishnu Banerjee

No relationship to disclose

Alexis Visotcky

No relationship to disclose

Giamila Fantuzzi

No relationship to disclose

Desmona Strahan

No relationship to disclose

Lauren Matthews

No relationship to disclose

Roxanne Dakers

No relationship to disclose

Cynthia Carridine-Andrews

No relationship to disclose

Katya Seligman

No relationship to disclose

Sparkle Springfield

No relationship to disclose

Angela Odoms-Young

No relationship to disclose

Susan Hong

Consulting or Advisory Role: Watermark Research Partners

Kent Hoskins

No relationship to disclose

Virginia Kaklamani

No relationship to disclose

Lisa Sharp

No relationship to disclose

REFERENCES

- 1.Joslyn SA, West MM: Racial differences in breast carcinoma survival. Cancer 88:114-123, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Newman LA, Griffith KA, Jatoi I, et al. : Meta-analysis of survival in African American and white American patients with breast cancer: Ethnicity compared with socioeconomic status. J Clin Oncol 24:1342-1349, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tammemagi CM, Nerenz D, Neslund-Dudas C, et al. : Comorbidity and survival disparities among black and white patients with breast cancer. JAMA 294:1765-1772, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eley JW, Hill HA, Chen VW, et al. : Racial differences in survival from breast cancer. Results of the National Cancer Institute black/white cancer survival study. JAMA 272:947-954, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gerend MA, Pai M: Social determinants of black-white disparities in breast cancer mortality: A review. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 17:2913-2923, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McKenzie F, Jeffreys M: Do lifestyle or social factors explain ethnic/racial inequalities in breast cancer survival? Epidemiol Rev 31:52-66, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chlebowski RT, Chen Z, Anderson GL, et al. : Ethnicity and breast cancer: Factors influencing differences in incidence and outcome. J Natl Cancer Inst 97:439-448, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chan DS, Vieira AR, Aune D, et al. : Body mass index and survival in women with breast cancer-systematic literature review and meta-analysis of 82 follow-up studies. Ann Oncol 25:1901-1914, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, et al. : Prevalence of childhood and adult obesity in the United States, 2011-2012. JAMA 311:806-814, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Irwin ML, McTiernan A, Baumgartner RN, et al. : Changes in body fat and weight after a breast cancer diagnosis: Influence of demographic, prognostic, and lifestyle factors. J Clin Oncol 23:774-782, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Saquib N, Flatt SW, Natarajan L, et al. : Weight gain and recovery of pre-cancer weight after breast cancer treatments: Evidence from the women’s healthy eating and living (WHEL) study. Breast Cancer Res Treat 105:177-186, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Demark-Wahnefried W, Winer EP, Rimer BK: Why women gain weight with adjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 11:1418-1429, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8223(99)00298-9. Rock CL, Flatt SW, Newman V, et al: Factors associated with weight gain in women after diagnosis of breast cancer. Women’s Healthy Eating and Living Study Group. J Am Diet Assoc 99:1212-1221, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Playdon M, Thomas G, Sanft T, et al. : Weight loss intervention for breast cancer survivors: A systematic review. Curr Breast Cancer Rep 5:222-246, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reeves MM, Terranova CO, Eakin EG, et al. : Weight loss intervention trials in women with breast cancer: A systematic review. Obes Rev 15:749-768, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Paxton RJ, Phillips KL, Jones LA, et al. : Associations among physical activity, body mass index, and health-related quality of life by race/ethnicity in a diverse sample of breast cancer survivors. Cancer 118:4024-4031, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dennis Parker EA, Sheppard VB, Adams-Campbell L: Compliance with national nutrition recommendations among breast cancer survivors in “stepping stone.” Integr Cancer Ther 13:114-120, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Paxton RJ, Taylor WC, Chang S, et al. : Lifestyle behaviors of African American breast cancer survivors: A Sisters Network, Inc. study. PLoS One 8:e61854, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Foster GD, Wadden TA, Swain RM, et al. : Changes in resting energy expenditure after weight loss in obese African American and white women. Am J Clin Nutr 69:13-17, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kumanyika SK, Whitt-Glover MC, Gary TL, et al. : Expanding the obesity research paradigm to reach African American communities. Prev Chronic Dis 4:A112, 2007 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sheppard VB, Hicks J, Makambi K, et al. : The feasibility and acceptability of a diet and exercise trial in overweight and obese black breast cancer survivors: The Stepping STONE study. Contemp Clin Trials 46:106-113, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Delgado-Cruzata L, Zhang W, McDonald JA, et al. : Dietary modifications, weight loss, and changes in metabolic markers affect global DNA methylation in Hispanic, African American, and Afro-Caribbean breast cancer survivors. J Nutr 145:783-790, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. doi: 10.1007/s00520-015-2984-2. Chung S, Zhu S, Friedmann E, et al: Weight loss with mindful eating in African American women following treatment for breast cancer: A longitudinal study. Support Care Cancer 24:1875-1881, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Stolley MR, Sharp LK, Fantuzzi G, et al. Study design and protocol for moving forward: A weight loss intervention trial for African-American breast cancer survivors. BMC Cancer 15:1018, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Rock CL, Doyle C, Demark-Wahnefried W, et al. : Nutrition and physical activity guidelines for cancer survivors. CA Cancer J Clin 62:243-274, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bandura A. Social Foundations of Thought and Action. Englewood Cliffs, NJ, Prentice-Hall, 1986 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stokols D: Translating social ecological theory into guidelines for community health promotion. Am J Health Promot 10:282-298, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stolley MR, Sharp LK, Oh A, et al. : A weight loss intervention for African American breast cancer survivors, 2006. Prev Chronic Dis 6:A22, 2009 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stolley MR, Sharp LK, Wells AM, et al. : Health behaviors and breast cancer: Experiences of urban African American women. Health Educ Behav 33:604-624, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kreuter MW, Lukwago SN, Bucholtz RD, et al. : Achieving cultural appropriateness in health promotion programs: Targeted and tailored approaches. Health Educ Behav 30:133-146, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Going SB, Massett MP, Hall MC, et al. : Detection of small changes in body composition by dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry. Am J Clin Nutr 57:845-850, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Block G, Hartman AM, Dresser CM, et al. : A data-based approach to diet questionnaire design and testing. Am J Epidemiol 124:453-469, 1986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Block G, Woods M, Potosky A, et al. : Validation of a self-administered diet history questionnaire using multiple diet records. J Clin Epidemiol 43:1327-1335, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kriska A, Caspersen C: Introduction to a collection of physical activity questionnaires. Med Sci Sports Exerc 29:5-9, 1997 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. McCulloch CE, Searle SR, Neuhaus JM (eds): Generalized, Linear, and Mixed Models. Hoboken, NJ, Wiley, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Cohen J, Cohen P, West SG, et al (eds): Applied Multiple Regression/Correlation Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences (ed 3). New York, NY, Routledge Academic, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jensen MD, Ryan DH, Apovian CM, et al. : 2013 AHA/ACC/TOS guideline for the management of overweight and obesity in adults: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the Obesity Society. J Am Coll Cardiol 63,2985-3023, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. doi: 10.1111/obr.12203. Kong A, Tussing-Humphreys LM, Odoms-Young AM, et al: Systematic review of behavioural interventions with culturally adapted strategies to improve diet and weight outcomes in African American women. Obes Rev 15:62-92, 2014 (suppl 4) [Erratum: J Am Coll Cardiol 63:3029-3030, 2014] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Greenlee HA, Crew KD, Mata JM, et al. : A pilot randomized controlled trial of a commercial diet and exercise weight loss program in minority breast cancer survivors. Obesity (Silver Spring) 21:65-76, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Harrigan M, Cartmel B, Loftfield E, et al. : Randomized trial comparing telephone versus in-person weight loss counseling on body composition and circulating biomarkers in women treated for breast cancer: The lifestyle, exercise, and nutrition (LEAN) study. J Clin Oncol 34:669-676, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rock CL, Flatt SW, Byers TE, et al. : Results of the exercise and nutrition to enhance recovery and good health for you (ENERGY) trial: A behavioral weight loss intervention in overweight or obese breast cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol 33:3169-3176, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kumanyika SK, Whitt-Glover MC, Haire-Joshu D: What works for obesity prevention and treatment in black Americans? Research directions. Obes Rev 15:204-212, 2014. (suppl 4) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Williamson DA, Bray GA, Ryan DH: Is 5% weight loss a satisfactory criterion to define clinically significant weight loss? Obesity (Silver Spring) 23:2319-2320, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. doi: 10.1002/oby.20819. Ryan D, Heaner M: Guidelines (2013) for managing overweight and obesity in adults. Preface to the full report. Obesity (Silver Spring) 22:S1-S3, 2014 (suppl 2) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.DeLany JP, Jakicic JM, Lowery JB, et al. : African American women exhibit similar adherence to intervention but lose less weight due to lower energy requirements. Int J Obes 38:1147-1152, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Thomson CA, Stopeck AT, Bea JW, et al. : Changes in body weight and metabolic indexes in overweight breast cancer survivors enrolled in a randomized trial of low-fat vs. reduced carbohydrate diets. Nutr Cancer 62:1142-1152, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mefferd K, Nichols JF, Pakiz B, et al. : A cognitive behavioral therapy intervention to promote weight loss improves body composition and blood lipid profiles among overweight breast cancer survivors. Breast Cancer Res Treat 104:145-152, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jen KL, Djuric Z, DiLaura NM, et al. : Improvement of metabolism among obese breast cancer survivors in differing weight loss regimens. Obes Res 12:306-312, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]