Abstract

Many examples of the appearance of similar traits in different lineages are known during the evolution of organisms. However, the underlying genetic mechanisms have been elucidated in very few cases. Here, we provide a clear example of evolutionary parallelism, involving changes in the same genetic pathway, providing functional adaptation of RH1 pigments to deep-water habitats during the adaptive radiation of East African cichlid fishes. We determined the RH1 sequences from 233 individual cichlids. The reconstruction of cichlid RH1 pigments with 11-cis-retinal from 28 sequences showed that the absorption spectra of the pigments of nine species were shifted toward blue, tuned by two particular amino acid replacements. These blue-shifted RH1 pigments might have evolved as adaptations to the deep-water photic environment. Phylogenetic evidence indicates that one of the replacements, A292S, has evolved several times independently, inducing similar functional change. The parallel evolution of the same mutation at the same amino acid position suggests that the number of genetic changes underlying the appearance of similar traits in cichlid diversification may be fewer than previously expected.

Keywords: rhodopsin, adaptation

Morphologically and functionally similar characters often evolve more than once because of the operation of similar selective pressures in different lineages of organisms. One of the fundamental questions concerning character similarity is whether the genetic mechanisms underlying similar evolutionary changes are the same or are different. Similar evolutionary changes caused by the same genetic mechanism are the result of parallelism, whereas those changes produced by different mechanisms are because of convergence (1). Although a few cases of both parallelism and convergence in Drosophila pigmentation have been recently observed (2–4), the genetic bases of the appearance of similar characters largely remain to be elucidated.

In East Africa, Lakes Victoria and Malawi harbor endemic cichlid fish communities comprising ≈450–700 species, whereas Lake Tanganyika holds ≈250 species (5). These communities are ecologically and morphologically highly diverse but encompass relatively low genetic diversity, particularly in Malawi and Victoria (6–11). Cichlids are becoming a model system for understanding the genetic basis of vertebrate speciation (12, 13). Parallel appearances of similar feeding morphologies (8, 14) and nuptial coloration (15) in different lakes or lineages have been documented. The repeated evolution of similarly adapted cichlid species in various lineages in the same lake or even in different lakes presents an opportunity to explore the issue of convergence and parallelism. Recently, several studies of genes underlying the diversity of cichlids have been reported (12, 16–21). Here, we focus on one of those genes, a rhodopsin, RH1, which is an excellent candidate to test for evolutionary parallelism, because repeated amino acid replacements occurring at multiple positions were suggested to have arisen convergently as functional adaptation (22).

Visual pigment is a seven-transmembrane α-helical protein that contains a light-absorbing chromophore, retinal (23, 24). Vertebrate visual pigments are classified into five groups in the phylogenetic tree (25), and one of the groups is called Rh or RH1, to which rhodopsins, visual pigments in rod photoreceptor cells responsible for scotopic (twilight) vision, belong (25, 26). The absorption spectrum of a visual pigment can be altered by amino acid substitutions within the protein moiety of the visual pigment, and key replacement positions are located close to the retinal-binding pocket (26–28). The chromophore is 11-cis aldehyde of either vitamin A1 (retinaldehyde) or vitamin A2 (3,4-didehydroretinaldehyde) (23). Red-shifts of 10–40 nm can be achieved by changing chromophores from A1 to A2 (29).

The evolution of visual pigments serves as a prime model for the study of molecular adaptation in vertebrates (26, 28), and several such cases have been reported in primates (30), birds (26), and fishes (31, 32). For example, color vision in primates shows a correlation between molecular adaptation and ecological specialization (33–35) in that spectral sensitivity of eyes match the animal's environment, allowing for the processing of greater amounts of information. The visual system of the Comoran coelacanth (32) and deep-water Cottoid fishes in Lake Baikal (31) have rod cells in which the peak sensitivity of visual pigments is blue-shifted to a range of 470–490 nm, because longer and short wavelengths are more rapidly attenuated with increasing water depth, and blue-green light (470–490 nm) penetrates to the greatest depth in clear-water habitats (36). Aquatic environments provide a great diversity of photic conditions, varying in aspects such as turbidity, color, and brightness (28). The purpose of our study was to investigate the evolution of the RH1 gene in cichlid fishes of the East African Great Lakes in the course of their adaptation to various lacustrine habitats.

Materials and Methods

DNA Sequencing and Sequence Analysis. Determination of the cichlid RH1 gene was as described (22). Nucleotide sequences were deposited in GenBank under accession nos. AB084924–AB084947, AB185213–AB185242, AB185390, and AB196147.

Comparison of Absorption Spectra of Cichlid RH1 Pigments. RH1 coding sequences were amplified by means of PCR using the cichlid genome as template with a pair of PCR primers designated RH1HindIIIF and RH1KpnIR (see Supporting Materials and Methods, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). PCR products were digested with KpnI and HindIII, and fragments were cloned into a pFLAG-CMV-5a (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis) expression vector. Their expression and characterization was performed according to the method of Ueyama et al. (ref. 37, and for procedural details, see Supporting Materials and Methods).

Chromophore Use. Adult cichlids were dark-adapted for 12 h, then decapitated and enucleated. Retinal was extracted from crude eye-cup homogenates or isolated retina as an oxime, as described (refs. 38–40, and for procedural details, see Supporting Materials and Methods).

Construction of RH1 Mutants. In vitro mutagenesis of the RH1 was performed by extension of DNA synthesis of overlapped oligonucleotide primers using PCR (41).

Results

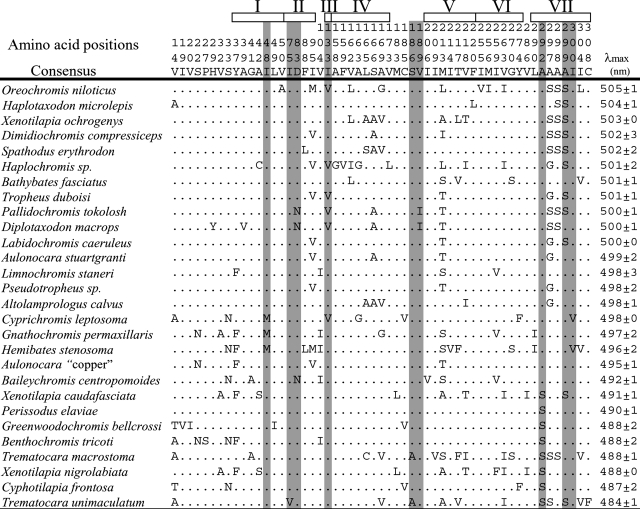

Sequence Analysis of Cichlid RH1 Genes. We sequenced the RH1 partial coding region (924 bp corresponding to amino acids 13–320 among 354 of the full-length of the cichlid RH1 protein) of 56 species (Fig. 4, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). Among all sequences, 56 amino acid positions were variable, 42 positions were within the region of transmembrane helices, and 7 positions were close to the retinal-binding pocket. The other 14 variable positions were within the region of extracellular loops, and 2 positions were close to the retinal-binding pocket (Table 1).

Table 1.

The informative positions of amino acid replacements among 28 cichlid RH1 genes, with λmax values

Read vertically, the top three lines specify the amino acid positions in the cichlid RH1 pigment. A dot indicates an amino acid identical to the RH1 consensus. Open boxes at the top indicate the positions of the seven transmembrane regions. Shaded columns indicate the amino acid replacements that line the chromophore-binding pockets or are in close proximity to the chromophore. The position of residues in each helix is based on the model of Baldwin (61) and on the crystal structure of bovine rhodopsin (62).

Absorption Spectra. To test the relationships between the absorption spectra and ecology, we reconstructed RH1 pigments and measured the absorption spectra for 28 cichlid species from African rivers and the three Great Lakes. First, we examined the chromophore usage in laboratory-bred individuals of a Victorian “Haplochromis sp.” and the Malawian Dimidiochromis compressiceps. The ratio of A1 to A2 was revealed to be ≈10:1 (data not shown), indicating that the predominant chromophore type of visual pigments in these cichlids is A1-derived. This result is consistent with the previous data of cichlid visual pigments (21, 42). We thus reconstructed all studied cichlid RH1 pigments with A1-derived retinal.

Absorption spectra were represented by their peak spectral sensitivity (λmax) values. In the 28 cichlid species tested, the λmax values of the RH1 pigments varied from 484 ± 1 nm in Trematocara unimaculatum to 505 ± 1 nm in Oreochromis niloticus (Table 1). From repeated measurements of 35 samples, we determined that the mean measurement error (with 95% confidence intervals) was 1.4 ± 0.25 nm.

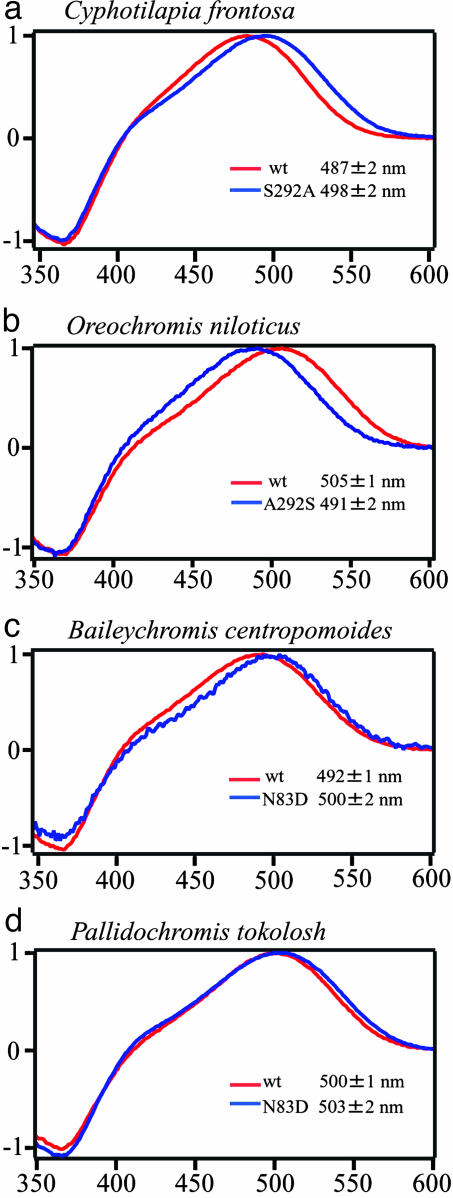

Amino Acids Responsible for the Differences in λmax Values. To identify the residues responsible for spectral tuning of these pigments, we focused on amino acids near the chromophore. Among the variable amino acids, those at positions 83 and 292 were expected to be located in the transmembrane region, close to the retinal-binding pocket. At these positions, we constructed mutated cichlid RH1 pigments, such as S292A (amino acid change from serine to alanine at the position 292), A292S, D83N, and N83D. RH1 sequences came from the Tanganyikan cichlids Baileychromis centropomoides, Cyphotilapia frontosa, Limnochromis staneri, and Trematocara macrostoma, the Malawian Diplotaxodon macrops, Pallidochromis tokolosh, and the widely distributed O. niloticus. Fig. 1 shows representative results of absorption spectra with λmax values of wild-type and mutated RH1. In the RH1 of C. frontosa (Fig. 1a), the S292A mutation led to a shift in the peak sensitivity (λmax) from 487 ± 2 nm to 498 ± 2 nm, an 11-nm shift toward the red end of the spectrum. Similarly, in T. macrostoma, a 12-nm red-shift, from 488 ± 1 nm to 500 ± 1 nm, was observed in the S292A mutant. The reverse A292S mutation in the RH1 pigment of O. niloticus caused the λmax value to shift 14 nm toward blue from 505 ± 1nmto491 ± 2 nm (Fig. 1b). In the RH1 pigment of B. centropomoides, the N83D mutation caused an 8-nm shift of the λmax value toward red from 492 ± 1 nm to 500 ± 2 nm (Fig. 1c). However, N83D caused only slight shifts of the λmax values from 500 ± 1 nm to 503 ± 1nmin P. tokolosh (Fig. 1d), and from 500 ± 1nmto502 ± 2 nm in D. macrops (data not shown) pigments. In the RH1 pigment of L. staneri, the reverse mutation D83N also caused the slight shift of λmax value from 498 ± 3 nm to 494 ± 1 nm (data not shown).

Fig. 1.

Absorption spectra of the wild-type (wt) and mutated RH1 pigments evaluated by the dark–light difference spectra. When the pigment was not bleached, RH1 pigments have λmax values at ≈500 nm. When the regenerated pigments were exposed to light, new absorption peaks at ≈360 nm were observed, indicating that 11-cis-retinal in the pigment was isomerized by light, and all-transretinal oxime was released. In the different spectra, positive peaks at wavelengths of ≈500 nm correspond to the visual pigment; negative peaks at 360 nm are derived from release of retinal oxime. Red and blue lines indicate the absorption spectra of wild-type and mutated RH1 pigments from C. frontosa (a), O. niloticus (b), B. centropomoides (c), and P. tokolosh (d), respectively.

Discussion

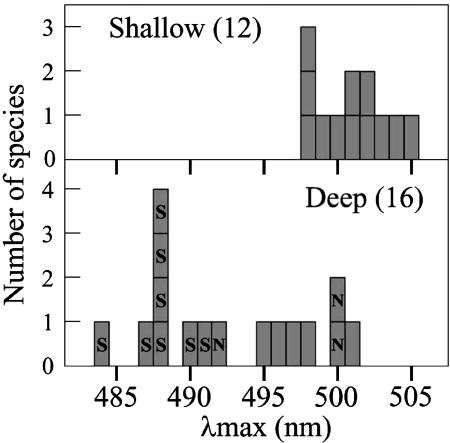

Spectral Tuning for Adaptation to Deep-Water Habitats. The wide range of absorption spectra of the RH1 pigments observed in cichlids (Table 1) raises the issue of its evolutionary significance. With the exception of a chameleon, the λmax values of terrestrial vertebrate RH1 pigments have been found to range from 495 to 508 nm (26, 43). For 19 of the surveyed cichlid species, the λmax values of RH1 pigments fell within this “normal” range (Table 1; 495 ± 1 nm in Aulonocara “copper” to 505 ± 1 nm in O. niloticus). Peak sensitivities of RH1 lay outside this range and shifted toward blue in nine of the species analyzed (Table 1; 484 ± 1 nm in T. unimaculatum to 492 ± 1 nm in B. centropomoides). For the species sampled from Lakes Malawi and Tanganyika, we have examined data on their ecology and habitat preferences (refs. 44–46, Table 2, and Supporting References, which are published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). The λmax values of the RH1 pigments from all shallow-water cichlid species in our study fell within the range of terrestrial vertebrate RH1 pigments. All of the blue-shifted species live in relatively deep waters in Lake Tanganyika, which has clear water, except near some river estuaries. Thus, the blue shift of their λmax values appears to result from adaptation to deep-water environments (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Frequency distributions of λmax of cichlid RH1 pigments. λmax values were grouped according to whether the species occupy shallow- or deep-water habitats. Each square represents 1 species (total 28). S, 292S; N, 83N; within the square.

However, many deep-water species did not show a blue shift, including the Tanganyikan Bathybates fasciatus, Hemibates stenosoma, Gnathochromis permaxillaris, and L. staneri, and the Malawian D. macrops and P. tokolosh. Perhaps such species have other adaptations to the deep-water visual environment, such as having large eyes, as have D. macrops (47), P. tokolosh (48), and H. stenosoma (49). Other deep-water species may not constantly live in the light-limited depth water zone: L. staneri, H. stenosoma, and B. fasciatus have broad depth ranges, and some species are believed to migrate to the surface at night (44).

Effect of D83N and A292S in Cichlid RH1 Pigments. Several mutation analysis studies targeting positions 83 and 292 have been conducted. S292A in RH1 pigments in coelacanth or a replacement at the corresponding position in mammalian red and green pigments shifts the λmax values 8–28 nm toward red (32, 50, 51), although the reverse mutation in human pigment did not cause any change (52). It was also reported that D83N in bovine RH1 pigment shifts the λmax values 6 nm toward blue (53). In the present study, we demonstrated that A292S and S292A were responsible for significant spectral shifts of >10 nm in cichlid RH1 pigments. We found that D83N caused an 8-nm spectral shift toward blue in B. centropomoides RH1 pigments, but smaller spectral shifts in two Malawian cichlids (2–3 nm) and in L. staneri RH1 pigments (4 nm), which is close to the measurement error of the λmax values in this study amounting to ± 1.4 nm. It is likely that substitutions at other sites affect the spectral tuning of RH1 pigments, in addition to those that we have studied. This assumption might explain the observations that D83N seemed to cause minimal spectral shift in some cases, and might also explain the substantial differences in peak sensitivities of O. niloticus (λmax = 505 ± 1 nm) and A.“copper” (λmax = 495 ± 1 nm), despite their having the same amino acids at both positions 83 and 292 (Table 1). However, the independent fixation of the D83N mutation in deep-water species in both lakes, and its absence from shallow water and riverine species, suggests that it may have functional significance in adaptation to deep water, even though our estimates of the resulting shifts in peak sensitivity were less than the range of measurement error in the present study.

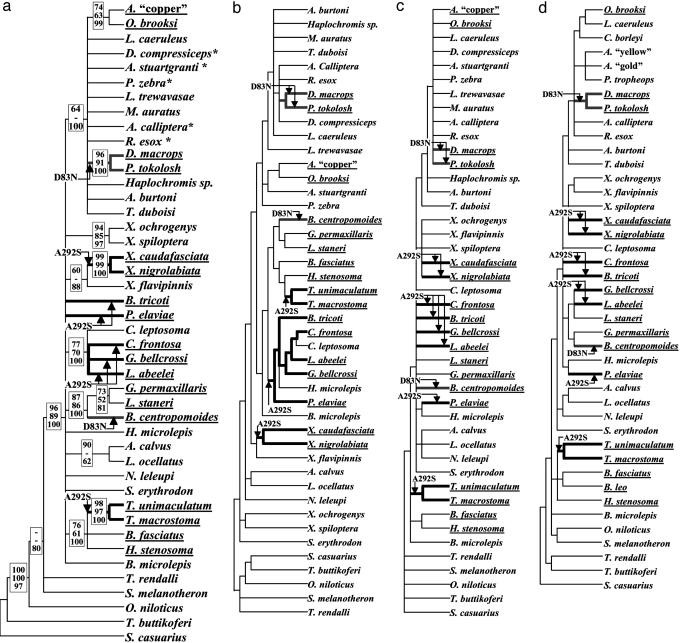

Parallel Adaptations to Deep-Water Habitat by the Same Nucleotide Changes. Trees based on RH1 sequences, mitochondrial ND2 sequences, and on SINE insertions all indicated an independent origin of the D83N substitution (a nucleotide substitution G247A) in Lake Tanganyika Baileychromis and the Lake Malawi deep-water taxa (Fig. 3). Assuming a single gain of D83N at the base of the Tanganyika radiation increases tree length by minimally 14 mutation steps, based on an analysis using the software package macclade (54). However, we did not obtain strong evidence that D83N necessarily results in a significant change in λmax. Further examination of RH1 functions may be illuminating.

Fig. 3.

Phylogenetic relationships among East African cichlid fishes, demonstrating the multiple origin of specific adaptations to deep-water habitat by means of amino acid substitutions from D to N at position 83 (“Malawi/Baileychromis-type;” bold gray branches) and from A to S at position 292 (“Tanganyika-type;” bold black branches). Arrows indicate the occurrence of amino acid replacements of A292S and D83N at the branches. The deep-water species are underlined. (a) Strict consensus tree based on 924 bp of the RH1 gene summarizing the results of maximum parsimony (equal weights, heuristic search, random addition of taxa, 10 replicates; tree length, 270 mutations; CI excluding uninformative characters, 0.46), neighbor-joining (TrN+I+Γ model) and Bayesian inference (2,000,000 generations, no chains, trees sampled every 100 generations, and burn-in of 10,000). Bootstrap values for parsimony (above) and neighbor joining (center), and Bayesian posterior probabilities (below) are shown, when >50. Asterisks indicate where other taxa not shown (see Supporting Materials and Methods) had identical sequences. (b) RH1 gene tree obtained by Bayesian inference. (c) The phylogenetic tree based on SINEs (55, 56). (d) Strict consensus based on the NADH2 gene obtained by neighbor-joining (substitution model HKY+I+G), weighted maximum parsimony [search parameters and weights are as in Salzburger et al. (63), 127 most parsimonious trees] and Bayesian analysis (10 chains, 2 Mio generations, 1 tree saved per 100 generations, and burnin factor of 1 Mio). In this tree, we used existing sequences from some haplochromine species closely related to those used in the RH1 and SINE trees. These taxon substitutions would be unlikely to influence the structure of the tree in relation to the nodes where RH1 transitions are believed to occur.

From the relatively poorly resolved strict consensus RH1 gene tree (Fig. 3a), A292S (a nucleotide substitution G874T) appeared to evolve independently between one and three times, according to a reconstruction of ancestral states by using macclade (54). By using a two-tailed Kishino–Hasegawa test (options: full optimization and 1,000 bootstrap replicates, see Supporting Materials and Methods) to test a number of trees derived by various methods, including the consensus tree, the best likelihood ratio score was assigned to a tree obtained by Bayesian inference (Fig. 3b), followed by a neighbor-joining tree (data not shown). Both indicate three independent A292S transitions. Estimates of the species phylogeny derived from SINE insertions (55, 56) across the genome (Fig. 3c) and from mitochondrial NADH2 sequences (Fig. 3d) were also consistent with multiple independent origins of S at position 292. The A292S mutation is clearly functional. In most cases, the deep-water species with A292S had close relatives found in shallow water for at least part of their range and in which position 292 was A and the RH1 pigment was not shifted toward blue (see Supporting Materials and Methods).

Thus, it seems likely that fixation of spectral shift mutations at the same base position, A292S, occurred multiple times in deep-water-dwelling Lake Tanganyikan cichlids. This finding may be the result of independent mutational events at position 292 in different lineages. Another possibility is that the A292S transition might have arisen once early in the history of the Tanganyikan radiation, but many of the descendent species maintained A/S polymorphism, with fixation for S occurring independently in deep-water lineages, and fixation for A in other species, including all those remaining in shallow water. Persistent polymorphism in a functional gene, however, seems implausible (it is not an obvious case to propose frequency-dependent selection), and we did not find any instances of A/S polymorphism among any of the taxa investigated (466 alleles tested, see Supporting Materials and Methods).

Introgressive hybridization, reported to have occurred in African cichlid radiations (57, 58), might also cause the appearance of parallel evolution of a trait. In this case, the genetic basis of the trait may have arisen less often that it appears from a phylogeny estimate, and have been transmitted horizontally between lineages by introgression. Fixation may then have occurred, particularly when introgression was followed by strong directional selection for adaptive traits, such as appropriate variants of a functional gene like RH1. The broad compatibility of the phylogeny of the major lineages estimates from mitochondrial NADH2 sequences and from the mainly SINE insertions provides no evidence for introgression. In phylogenies based on each of these methods, several independent A292S changes could be observed. Although it seems unlikely, the possibility remains that the similarity of the RH1 tree to other estimates of the species tree may be the result of recombination of introgressed RH1 sequences with ancestral RH1 sequences with eventual repeated independent fixation of an RH1 sequence that largely retains the character of the ancestral sequence of the particular lineage, but which has gained an S at position 292 from introgression.

It is believed that the replacement A292S resulting in blue shifts of RH1 pigments has occurred several times during the 400 million years of vertebrate evolution (26, 59, 60). In the present study, however, we have demonstrated that the same replacement has occurred in cichlids over a very short evolutionary period of a few million years, although several amino acid positions are known to shift the λmax of RH1 pigment (26). The repeated fixation of the same substitution at the same position may indicate that the number of genes and/or amino acid positions responsible for the functional diversity of cichlid fishes in the African Great Lakes might be fewer than previously expected by assuming convergence.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. T. Sato for helpful discussions and Ms. K. Sakai for technical assistance. This work was supported by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology of Japan (N.O.), the Austrian Academy of Sciences (S.K.), the Austrian Science Foundation (C.S.), and the Natural Environment Council U.K. (G.F.T.).

Author contributions: N.O. designed research; T.S. performed research; T.S., Y.T., H.I., G.F.T., S.K., C.S., and Y.S. analyzed data; and T.S., Y.T., H.I., G.F.T., S.K., C.S., Y.S., and N.O. wrote the paper.

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

Data deposition: The sequences reported in this paper have been deposited in the GenBank database (accession nos.AB084924–AB084947, AB185213–AB185242, AB185390, and AB196147).

References

- 1.Hodin, J. (2000) J. Exp. Zool. 288 1–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gompel, N. & Carroll, S. B. (2003) Nature 424 931–935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sucena, E., Delon, I., Jones, I., Payre, F. & Stern, D. L. (2003) Nature 424 935–938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wittkopp, P. J., Williams, B. L., Selegue, J. E. & Carroll, S. B. (2003) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100 1808–1813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Turner, G. F., Seehausen, O., Knight, M. E., Allender, C. J. & Robinson, R. L. (2001) Mol. Ecol. 10 793–806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Meyer, A., Kocher, T. D., Basasibwaki, P. & Wilson, A. C. (1990) Nature 347 550–553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sturmbauer, C. & Meyer, A. (1992) Nature 358 578–581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kocher, T. D., Conroy, J. A., McKaye, K. R. & Stauffer, J. R. (1993) Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2 158–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bowers, N., Stauffer, J. R. & Kocher, T. D. (1994) Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 3 75–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Salzburger, W., Meyer, A, Baric, S., Verheyen, E. & Sturmbauer, C. (2002) Syst. Biol. 51 113–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Terai, Y., Takezaki, N., Mayer, W. E., Tichy, H., Takahata, N., Klein, J. & Okada N. (2004) J. Mol. Evol. 58 64–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Terai, Y., Mayer, W. E., Klein, J., Tichy, H. & Okada, N. (2002) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99 15501–15506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kocher, T. D. (2004) Nat. Rev. Genet. 5 288–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rüber, L., Verheyen, E. & Meyer, A. (1999) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96 10230–10235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Allender, C. J., Seehausen, O., Knight, M. E., Turner, G. F. & Maclean, N. (2003) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100 14074–14079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Terai, Y., Morikawa, N., Kawakami, K. & Okada, N. (2002) Mol. Biol. Evol. 19 574–578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Terai, Y., Morikawa, N. & Okada, N. (2002) Mol. Biol. Evol. 19 1628–1632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Terai, Y., Morikawa, N., Kawakami, K. & Okada, N. (2003) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100 12798–12803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Albertson, R. C., Streelman, J. T. & Kocher, T. D. (2003) J. Hered. 94 291–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Albertson, R. C., Streelman, J. T. & Kocher, T. D. (2003) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100 5252–5257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carleton, K. L. & Kocher, T. D. (2001) Mol. Biol. Evol. 18 1540–1550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sugawara, T., Terai, Y. & Okada, N. (2002) Mol. Biol. Evol. 19 1807–1811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wald, G. (1968) Nature 219 800–807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shichida, Y. & Imai, H. (1998) Cell Mol. Life Sci. 54 1299–1315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Okano, T., Kojima, D., Fukada, Y., Shichida, Y. & Yoshizawa, T. (1992) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 89 5932–5936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yokoyama, S. (2000) Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 19 385–419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kochendoerfer, G. G., Lin, S. W., Sakmar, T. P. & Mathies, R. A. (1999) Trends Biochem. Sci. 24 300–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bowmaker J. K. (1995) Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 15 1–31. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Munz, F. W. & McFarland, W. N. (1977) in The Visual System in Vertebrates, ed. Crescitelli, F. (Springer, New York), pp. 193–274.

- 30.Shyue, S. K., Hewett-Emmett, D., Sperling, H. G., Hunt, D. M., Bowmaker, J. K., Mollon, J. D. & Li, W. H. (1995) Science 269 1265–1267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hunt, D. M., Fitzgibbon, J., Slobodyanyuk, S. J., & Bowmaker, J. K. (1996) Vision Res. 36 1217–1224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yokoyama, S., Zhang, H., Radlwimmer, F. B. & Blow, N. S. (1999) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96 6279–6284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jacobs, G. H., Neitz, M., Deegan, J. F. & Neitz, J. (1996) Nature 382 156–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jacobs, G. H. (1996) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93 577–581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sumner, P. & Mollon, J. D. (2000) J. Exp. Biol. 203 1963–1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Locket, N. A. (1977) in The Visual System in Vertebrates, ed. Crescitelli, F. (Springer, New York), Vol. 7, pp. 67–192. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ueyama, H., Kuwayama, S., Imai, H., Tanabe, S., Oda, S., Nishida, Y., Wada, A., Shichida, Y. & Yamade, S. (2002) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 294 205–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Imamoto, Y., Yoshizawa, T. & Shichida, Y. (1996) Biochemistry 35 14599–14607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Imai, H., Hirano, T., Terakita, A., Shichida, Y., Muthyala, R. S., Chen, R. L., Colmenares, L. U. & Liu, R. S. (1999) Photochem. Photobiol. 70 111–115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kito, Y., Seki, T., Suzuki, T. & Uchiyama, I. (1986) Vision Res. 26 275–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ho, S. N., Hunt, H. D., Horton, R. M., Pullen, J. K. & Pease, L. R. (1989) Gene 77 51–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Muntz, W. R. (1976) Vision Res. 16 897–903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kraft, T. W., Schneeweis, D. M. & Schnapf, J. L. (1993) J. Physiol. 464 747–765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Coulter, G. W. (1991) in Lake Tanganyika and Its Life, ed. Coulter, G. W. (Oxford Univ. Press, London), pp. 151–199.

- 45.Greenwood, P. H. (1991) in Cichlid Fishes: Behaviour, Ecology, and Evolution, ed. Keenleyside, M. H. A. (Chapman & Hall, London), pp. 86–102.

- 46.Fryer, G. & Iles, T. D. (1972) The Cichlid Fishes of the Great Lakes of Africa: Their Biology and Evolution (Oliver and Boyd, Edinburgh).

- 47.Turner, G. F. & Stauffer, J. R. (1998) Ichthyol. Explor. Freshwaters 8 239–252. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Turner, G. F. (1994) Ichthyol. Explor. Freshwaters 5 377–383. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Anker, G.C. & Dullemeijer, P. (1996) in Fish Morphology: Horizon of New Research, eds. Datta Munshi, J. S. & Dutta, H. M. (A. A. Balkema Publishers, Brookfield, VT), pp. 1–20.

- 50.Sun, H., Macke, J. P. & Nathans, J. (1997) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94 8860–8865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fasick, J. I. & Robinson, P. R. (2000) Visual Neurosci. 17 781–788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fasick, J. I., Lee, N. & Oprian, D. D. (1999) Biochemistry 38 11593–11596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nathans, J. (1990) Biochemistry 29 937–942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Maddison, W. P. & Maddison, D. R. (1992) macclade: Analysis of Phylogeny and Character Evolution (Sinauer, Sunderland, MA), Version 3.0.

- 55.Takahashi, K., Terai, Y., Nishida, M. & Okada, N. (2001) Mol. Biol. Evol. 18 2057–2066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Takahashi K, Okada N. (2002) Mol. Biol. Evol. 19 1303–1312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Seehausen, O. (2004) Trends Ecol. Evol. 19 198–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Salzburger, W., Baric, S. & Sturmbauer, C. (2002b) Mol. Ecol. 11 619–625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hope, A. J., Partridge, J. C., Dulai, K. S. & Hunt, D. M. (1997) Proc. R. Soc. London Ser. B 264 155–163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hunt, D. M., Dulai, K. S., Partridge, J. C., Cottrill, P. & Bowmaker, J. K. (2001) J. Exp. Biol. 204 3333–3344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Baldwin, J. M. (1993) EMBO J. 12 1693–1703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Palczewski, K., Kumasaka, T., Hori, T., Behnke, C. A., Motoshima, H., Fox, B. A., Le Trong, I., Teller, D. C., Okada, T., Stenkamp, R. E., et al. (2000) Science 289 739–745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]