Abstract

The reaction of [Fe2(μ-OH)2(6-Me3-TPA)2]2+ (1) [6-Me3-TPA, Tris(6-methyl-2-pyridylmethyl)amine] with O2 in CH2Cl2 at –80°C gives rise to two new intermediates, 2 and 3, before the formation of previously characterized [Fe2(O)(O2)(6-Me3-TPA)2]2+ (4) that allow the oxygenation reaction to be monitored one electron-transfer step at a time. Raman evidence assigns 2 and 3 as a diiron–superoxo species and a diiron–peroxo species, respectively. Intermediate 2 exhibits its ν(O–O) at 1,310 cm–1 with a –71-cm–1 18O isotope shift. A doublet peak pattern for the 16O18O isotopomer of 2 in mixed-isotope Raman experiments strongly suggests that the superoxide ligand of 2 is bound end-on. This first example of a nonheme iron–superoxo intermediate exhibits the highest frequency ν(O–O) yet observed for a biomimetic metal–dioxygen adduct. The bound superoxide of 2, unlike the bound peroxide of 4, is readily reduced by 2,4-di-tert-butylphenol via a proton-coupled electron-transfer mechanism, emphasizing that metal–superoxo species may serve as oxidants in oxygen activation mechanisms of metalloenzymes. The discovery of intermediates 2 and 3 allows us to dissect the initial steps of dioxygen binding at a diiron center leading to its activation for substrate oxidation.

Keywords: nonheme diiron enzymes, oxygen activation, superoxo intermediate

The first step in the oxygen activation mechanisms of metalloenzymes is typically the binding of dioxygen, resulting in electron transfer from metal to O2 to form a metal–superoxo species (1–5). This conversion is best exemplified by heme proteins and synthetic iron porphyrin complexes where there is strong crystallographic and spectroscopic evidence for an  formulation (6, 7). Crystallographic evidence for an analogous formulation has also recently been reported for a copper enzyme peptidylglycine α-hydroxylating monooxygenase (PHM) (8). Furthermore, synthetic copper(I) and nickel(I) complexes react with O2 to give rise to copper and nickel superoxo species (9–16). In contrast, despite extensive investigations on their reactions with O2, superoxo intermediates have not yet been observed with nonheme diiron centers in enzymes or model complexes. Instead, diiron(III)-peroxo intermediates have been identified in several cases, and mechanistic hypotheses for their formation logically include an iron(II)iron(III)-superoxo species as a precursor (17–20). Previously, we reported the oxygenation of the diiron(II) complex, [Fe2(μ-OH)2(6-Me3-TPA)2](OTf)2 (1) [6-Me3-TPA, Tris(6-methyl-2-pyridylmethyl)amine], in CH2Cl2 at –60°C to form a dark green intermediate, 4, formulated as [FeIII2(O)(O2)(6-Me3-TPA)2]2+ (21) and characterized to have a (μ-oxo)(μ-1,2-peroxo)diiron(III) core (22). This intermediate formed with kinetics that were first order in diiron(II) complex and first order in O2 (23, 24). Here, we report studies at –80°C that have led to the observation of intermediate species before the formation of 4, including spectroscopic evidence for a diiron–superoxo intermediate 2 as well as detailed mechanistic analysis for the conversion of 2 to 4.

formulation (6, 7). Crystallographic evidence for an analogous formulation has also recently been reported for a copper enzyme peptidylglycine α-hydroxylating monooxygenase (PHM) (8). Furthermore, synthetic copper(I) and nickel(I) complexes react with O2 to give rise to copper and nickel superoxo species (9–16). In contrast, despite extensive investigations on their reactions with O2, superoxo intermediates have not yet been observed with nonheme diiron centers in enzymes or model complexes. Instead, diiron(III)-peroxo intermediates have been identified in several cases, and mechanistic hypotheses for their formation logically include an iron(II)iron(III)-superoxo species as a precursor (17–20). Previously, we reported the oxygenation of the diiron(II) complex, [Fe2(μ-OH)2(6-Me3-TPA)2](OTf)2 (1) [6-Me3-TPA, Tris(6-methyl-2-pyridylmethyl)amine], in CH2Cl2 at –60°C to form a dark green intermediate, 4, formulated as [FeIII2(O)(O2)(6-Me3-TPA)2]2+ (21) and characterized to have a (μ-oxo)(μ-1,2-peroxo)diiron(III) core (22). This intermediate formed with kinetics that were first order in diiron(II) complex and first order in O2 (23, 24). Here, we report studies at –80°C that have led to the observation of intermediate species before the formation of 4, including spectroscopic evidence for a diiron–superoxo intermediate 2 as well as detailed mechanistic analysis for the conversion of 2 to 4.

Materials and Methods

General Materials. Complex 1·(OTf)2 was prepared anaerobically according to literature procedures (21), and [Fe2(OD)2(6-Me3-TPA)2](OTf)2 was prepared by using the same procedure in the presence of 10 eq of D2O. All manipulations with complex 1 and solutions thereof were carried out under inert atmosphere by using a glovebox filled with nitrogen. Dichloromethane was distilled from CaH2 under nitrogen. 2,4-di-tert-butylphenol (DTBP) was purchased from Aldrich and used as received. Saturated solutions of O2 in CH2Cl2 for the kinetic studies were prepared by bubbling the dried O2 gas through the solvent for 10 min at room temperature. The concentration of O2 in this saturated solution was accepted to be as reported in the literature (25), 5.80 mM at 293 K. Fifty percent randomly 18O-labeled O2 (25% 16O2, 50% 16O18O, 25% 18O2), D2O, and CD2Cl2 were purchased from Cambridge Isotope Labs, and 99% 18O-labeled O2 was purchased from Isotec.

Sample Preparation. For UV-visible experiments, an anaerobic solution of 1·(OTf)2 (3.3 mg) in dry CH2Cl2 (3 ml) was introduced into a 1-cm-path-length cuvette and then cooled to 193 K in a Unisoku cryogenic cell holder attached to a Hewlett–Packard 8453A diode array spectrophotometer. O2 gas was bubbled through the solution for 5 min, and the formation of 2 was complete within 1 h. For Raman samples, 5 mM solutions of 1·(OTf)2 in CH2Cl2 or CD2Cl2 were used.

Raman Spectroscopy. Resonance Raman spectra were recorded at a resolution of 4 cm–1 on an Acton AM-506 spectrophotometer, using a Kaiser Optical holographic supernotch filter with a Princeton Instruments LN/CCD-1100-PB/UVAR detector cooled with liquid nitrogen. Laser excitation was provided by a Spectra-Physics 2060-KR-RS krypton ion laser. Solutions to be studied were transferred and frozen onto a gold-plated copper cold finger in thermal contact with a Dewar flask containing liquid nitrogen. The spectra were obtained at ≈77 K by using a 135°-backscattering geometry, and the Raman frequencies were referenced to indene. For each sample, the entire spectral range was obtained by collecting spectra at two different frequency windows with accumulation times of 8–16 min, and the resulting spectra were spliced together. Baseline corrections (polynomial fits) and curve fits (Gaussian functions) were carried out by using the program grams/ai (Thermo Galactic, Salem, NH). The simulated spectra for each species were obtained from the curve fits of each peak.

Kinetics Analyses. Kinetic measurements were performed with a Hewlett–Packard 8453A diode array spectrophotometer equipped with a Unisoku cryostat to control the temperature within ±1°C. Kinetic analysis of the formation of 2 followed the usual procedure for a second-order reaction, and activation parameters were obtained by employing the following equations (for detailed procedures, see Supporting Text, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site).

|

[1] |

|

[2] |

The absorbance change for the conversion of 2 to 4 showed biphasic behavior, which was analyzed by the equation

|

[3] |

to give two first-order rate constants, kα and kβ (kα < kβ). Activation parameters for both steps were obtained by using Eq. 2. To gain insight into the assignments of kα and kβ, the variations in the concentrations of 2–4 during the course of the reaction were simulated by using the program kinsim (www.biochem.wustl.edu/cflab/message.html).

Results

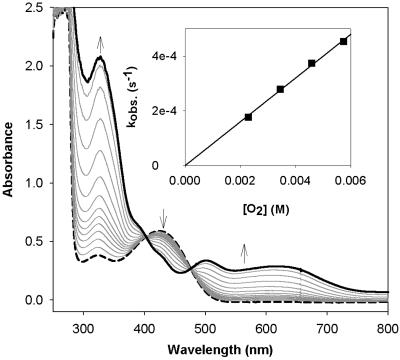

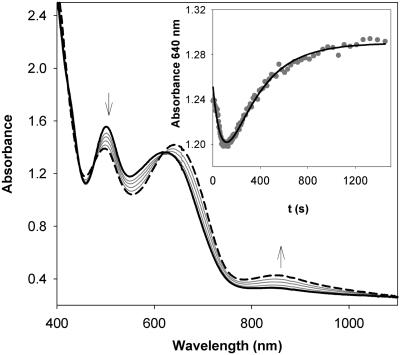

Oxygenation of 1. As previously reported, bubbling O2 through a solution of [Fe2(μ-OH)2(6-Me3-TPA)2](OTf)2 (1) in CH2Cl2 at –60°C affords over a period of 25 min a dark green O2 adduct, 4, which is best described as a (μ-oxo)(μ-1,2-peroxo)diiron(III) species with characteristic features at 494 nm (ε = 1,100 M–1·cm–1), 648 nm (ε = 1,200 M–1·cm–1), and 846 nm (ε = 230 M–1·cm–1) (21). When the oxygenation is instead carried out at –80°C for 1 h, an olive green species, 2, is obtained with three intense absorption bands at 325 nm (ε = 10,300 M–1·cm–1), 500 nm (ε = 1,400 M–1·cm–1), and 620 nm (ε = 1,200 M–1·cm–1) (Fig. 1), which are similar to, but distinct from, those associated with 4. This transformation could not be reversed by bubbling Ar through the solution of 2 for 30 min. Upon warming to –60°C, 2 converts to 4 and the characteristic near-infrared band of 4 at 846 nm, absent in 2, grows in (Fig. 2). This conversion is irreversible; lowering the temperature back to –80°C does not elicit any absorbance change.

Fig. 1.

Formation of 2 (solid line) at –80°C by bubbling O2 through a solution of 1 (dashed line) (0.2 mM) in CH2Cl2. (Inset) Plot of pseudo-first-order rate constants for the formation of 2 (0.1 mM) vs. concentration of O2 (2.30–5.76 mM) at –80°C.

Fig. 2.

Conversion of 2 (solid line) to 4 (dashed line) initiated by raising the temperature from –80°C to –60°C. (Inset) Plot of the absorbance change at 640 nm against time, showing a sharp decrease followed by a slow increase.

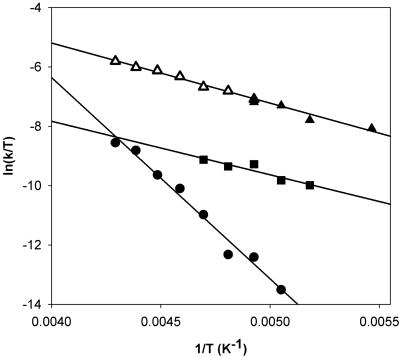

The kinetics for the oxygenation of 1 at –80°C could easily be monitored at 325 nm. Analysis of the monophasic absorbance increase at this wavelength as a function of [O2] according to Eq. 1 gave pseudo-first-order rate constants (Table 3, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site), from which was obtained the second-order rate constant, (8.0 ± 0.1) × 10–2 M–1·s–1. Values at two more temperatures, –75°C and –90°C, could be obtained, but the acquisition of additional temperature points was limited on the low side by the melting point of the solvent, CH2Cl2 (–95°C), and on the high side by the direct conversion of 1 to 4, as reported previously. Fig. 3 shows the Eyring plot for the oxygenation of 1 in the temperature range of –40°C to –90°C. The lower temperature points represent the conversion of 1 to 2 obtained in this study (Fig. 3, filled triangles), whereas the higher temperature points (Fig. 3, open triangles) represent data reported earlier by Kryatov et al. (23, 24) for the conversion of 1 to 4. Remarkably, all data points lie on the same straight line, corresponding to the activation parameters ΔH‡ = 16 ± 2 kJ·mol–1 and ΔS‡ = –167 ± 10 J·mol–1·K–1 (Table 1). Thus, the conversions of 1 to 2 and 1 to 4 share the same rate-determining step.

Fig. 3.

Eyring plots for the formation of 2 at lower temperature (▴), the formation of 4 at higher temperature (▵), and two stages of the conversion from 2 to 4 (• and ▪).

Table 1. Activation parameters of oxygenation of nonheme iron complexes.

| ΔH‡, KJ.mol-1 | ΔS‡, J.mol-1.K-1 | Ref. | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 → 2 (-90 to -75°C) | 16 ± 2 | -167 ± 10 | This work |

| 1 → 4 (>-70°C) | 16 ± 2 | -177 ± 10 | 22 and 23 |

| [Fe2(OH)2(TPA)2]2+ | 30 ± 4 | -94 ± 10 | 23 |

| [Fe2(OH)2(BQPA)2]2+ | 36 ± 4 | -80 ± 10 | 23 |

| [Fe2(OH)2(BnBQA)2]2+ | 16 ± 2 | -108 ± 10 | 23 |

| Hemerythrin | 16.8 | -46 | 25 |

| Myohemerythrin | 1.3 ± 0.4 | -121 ± 4 | 26 |

| [Fe2(Et-HPTB)(OBz)](BF4)2 | 15.4 ± 0.6 | -121 ± 3 | 27 |

| [Fe2(HPTP)(OBz)](BPh4)2 | 16.5 ± 0.4 | -114 ± 2 | 27 |

| [Fe2(HPTP)(OBz)2](BPh4) | 16.7 ± 2 | -132 ± 8 | 28 |

| [Fe2(HPTMP)(OBz)](BPh4)2 | 42.2 ± 1.6 | -63 ± 6 | 27 |

| [Fe2(PXDK)(O2CtBu)2(Melm)2] | ∼11 | ∼-150 | 29 |

| [Fe2(o-Xy2BzO)4(Py)2] | 4.7 ± 0.5 | -178 ± 10 | 30 |

| [Fe2(o-Xy2BzO)4(Melm)2] | 10.1 ± 1.0 | -153 ± 10 | 30 |

| [Fe2(o-Xy2BzO)4(THF)2] | 14.0 ± 1.0 | -135 ± 10 | 30 |

| 2 → 3 | 56 ± 3 | -25 ± 15 | This work |

| 3 → 4 | 15 ± 3 | -203 ± 16 | This work |

TPA, tris(2-pyridylmethyl)amine; BQPA, bis(2-quinolylmethyl)(2-pyridylmethyl)amine; BnBQA, benzyl-bis(2-quinolylmethyl)amine; Et-HPTB, N,N,N′,N′-tetrakis[(N-ethyl-2-benzimidazolyl)methyl]-2-hydroxy-1,3-diaminopropane; OBz, benzoate; HPTP, N,N,N′,N′-tetrakis(2-pyridylmethyl)-2-hydroxy-1,3-diaminopropane; HPTMP, N,N,N′,N′-tetrakis(6-methyl-2-pyridylmethyl)-2-hydroxy-1,3-diaminopropane; H2PXDK, m-xylylenediamine bis(propyl Kemp's triacid)imide; Melm, N-methylimidazole; o-Xy2BzO, o-dixylylbenzoate; Py, pyridine; THF, tetrahydrofuran.

Scrutiny of the spectral data associated with the conversion of 2 to 4 (Fig. 2) shows the involvement of yet another species, 3. When the absorbance change at 640 nm is plotted against time (Fig. 2 Inset), two phases are observed, a sharp decrease followed by a slow increase. Analysis of these data according to Eq. 3 afforded two first-order rate constants (Table 4, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site), but their sequence could not be unambiguously established. The temperature profile for this conversion was obtained in the range of –40°C to –80°C by firstly generating 2 at –80°C and then monitoring its transformation at the higher temperature. For this set of data, two sets of activation parameters (Table 1) could be extracted for the two phases of the reaction. The slow step shows a higher energy barrier, ΔH‡ = 56 ± 3 kJ·mol–1, and negligible activation entropy, ΔS‡ = –25 ± 15 J·mol–1·K–1, whereas the fast step displays a lower energy barrier, ΔH‡ = 15 ± 3kJ·mol–1, and a rather large and negative activation entropy, ΔS‡ = –203 ± 16 J·mol–1·K–1. Kinetic simulations were carried out under two mechanistic scenarios: (i) a slow reaction (2 → 3) followed by a fast reaction (3 → 4); and (ii) a fast reaction (2 → 3) followed by a slow reaction (3 → 4). In the first case, the maximum amount of 2 that can be generated represents 71% of the starting diiron complex after 1 h at –80°C. In contrast, in the second case, the amount of 2 reaches a maximum at 6.3% after 5 min and then starts to decrease. After 1 h, only a trace amount of 2 (<1%) would be expected (see Figs. 6 and 7 and Table 5, which are published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). A careful examination of the UV-visible spectra collected during the formation of 2 shows that absorbance changes in the 300- to 1,000-nm range unambiguously show monophasic behavior. So far none of the absorbance changes is found to correlate with the variation of [2] simulated in the second case. It is unlikely that the extinction absorption coefficient of 2 is close to zero in the whole range of 300–1,000 nm, especially, when a resonance Raman spectrum of 2 was obtained with an excitation wavelength of 647.1 nm (a detailed description of the resonance Raman experiments can be found in the next section). Thus, the first mechanistic scenario is strongly favored.

Because the conversion of 1 to 4 involves the loss of a water molecule derived from the two hydroxo bridges (Scheme 1), kinetic studies were also conducted with the Fe2(μ-OD)2 precursor to determine whether O–H bond breaking was a significant component in any of the three steps observed. It is clear from these studies that a kinetic isotope effect, if at all present, would be small and could not be resolved because of the small absorbance changes and the rapidity of the conversion. Thus, other factors besides O–H bond breaking act as the more significant barriers to the transformation of the bis(μ-hydroxo)diiron(II) precursor 1 to the ultimate (μ-oxo)(μ-1,2-peroxo)diiron(III) product 4.

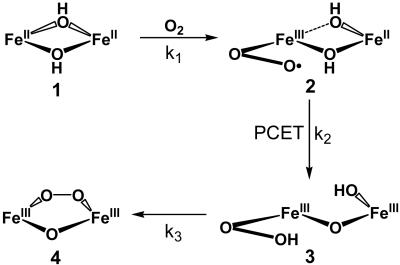

Scheme 1.

Proposed mechanism for oxygenation of 1.

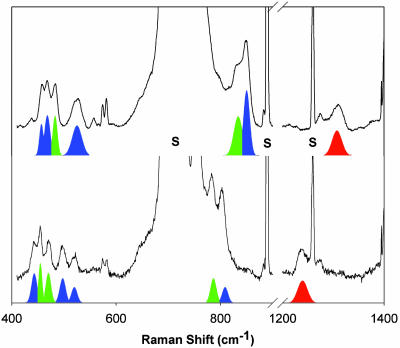

Resonance Raman Characterization. Resonance Raman spectroscopy has been a valuable tool for establishing the nature of metal–O2 adducts because of the sensitivity of the O–O stretching frequency to redox state. Fig. 4 shows the resonance Raman spectra of samples generated by exposure of 1 to 16O2 (Upper) or 18O2 (Lower) at –80°C with 647.1-nm excitation. (Unfortunately, the use of higher-energy excitation led to photodecomposition.) There are six 18O-sensitive bands, which can be assigned to one of three intermediates (2–4) and are listed in Table 2. Bands at 848 (–46) and 530 (–20) cm–1, and the Fermi doublet at 462 (–21) cm–1 are readily identified as the ν(O–O), νas(Fe–O) and νs(Fe–O) modes of 4, respectively, based on a previous study (21, 22). The three remaining bands at 1,310 (–71), 831 (–47), and 483 (–20) cm–1 exhibit frequencies and isotopic shifts that indicate their assignment to ν(O–O)superoxo, ν(O–O)peroxo, and ν(Fe–O) modes, respectively.

Fig. 4.

Resonance Raman spectra of the dark olive green solution generated from the reaction of 1 with 16O2 (Upper) or 18O2 (Lower) in CH2Cl2 at –80°C. All of the spectra were obtained at 77 K with an excitation wavelength of 647.1 nm. Color-coded features associated with 2 (red), 3 (green), and 4 (blue) were fit by using the program grams/ai (Thermo Galactic); solvent bands are labeled with “S.”

Table 2. Vibration frequencies of metal superoxo and hydroperoxo species, for comparison with the Raman data for intermediates 2–4.

| Complexes | v(O-O) | v(M-O) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 1,310 (-71) | — | This work |

| Fe(phthalocyan)O2 | 1,207 (-63) | 488 (-22) | 31 |

| Hemoglobin/O2 | 1,107 (-42) | 571 (-31) | 6 |

| Myoglobin/O2 | 1,103 (-38) | 572 | 6 |

| Synthetic heme/O2 complexes | 1,104-1,195 | 509-575 | 6 |

| Cu(L)O2 (L = N4, N3O) | 1,117-1,122 | — | 12-15 |

| Cu(TptBu,iPr)O2 | 1,112 (-52) | — | 9 |

| Cu(TpAd,iPr)O2 | 1,043 (-59) | — | 11 |

| Cu(2,6-Pr2NN)O2 | 968 (-51) | — | 10 |

| 3 | 831 (-47) | 483 (-20) | This work |

| OxyHr (FeIII-O-FeIIIOOH) | 844 (-48) | 503 (-24) | 32 |

| Fe2(μ-O)(μ-Ph4DBA)(TMEDA)2(OOH) | 843 (-46) | — | 33 |

| Fe2(BEPEAN)(μ-O)(OOH) | 868 (-40) | — | 34 |

| [Fe(H2BPPA)(OOH)]2+ | 830 (-17) | 621 (-22) | 35 |

| 4 | 848 (-46) | 530 (-20), 462 (-21) | 21 |

TptBu,iPr, hydrotris(3-tert-butyl-5-isopropyl-1-pyrazolyl)borate; TpAd,iPr, hydrotris(3-adamantyl-5-isopropyl-1-pyrazolyl)borate; 2,6-Pr2NN,2-(2,6-diisopropylphenyl)-aminopent-2-en-4-(2,6-diisopropylphenyl)imine anion; oxyHr, oxyhemerythrin; Ph4DBA, dibenzofuran-4,6-bis(diphenylacetate); TMEDA, N,N,N′,N′-tetramethylethyl-enediamine; BEPEAN, 2,7-bis(bis(2-(2-pyridyl)ethyl)aminomethyl)-1,8-naphthyridine; H2BPPA, bis(6-pivalamido-2-pyridylmethyl)-2-pyridylmethylamine.

A second resonance Raman spectrum was collected after warming up the sample to –70°C and maintaining it at this temperature for 15 min before freezing it for the Raman experiment. Under these conditions, the band at 1,310 cm–1 is still observed, but the bands at 831 and 483 cm–1 have vanished (Fig. 8, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site), indicating that they derive from two different species. A time-profile UV-visible experiment was conducted under the same conditions and the absorbance change at 640 nm shows that the fast phase of the conversion of 2 to 4 was complete within 5 min, whereas the slow phase lasted over an hour (Fig. 9, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). The concurrence in the fast phase of the UV-visible spectral changes with the disappearance of the two Raman bands at 831 and 483 cm–1 leads to the conclusion that 2 is an intermediate that exhibits the ν(O–O)superoxo at 1,310 cm–1 and 3 is another intermediate, with a ν(O–O)peroxo at 831 cm–1 and a ν(Fe–O) at 483 cm–1. Thus, the mechanistic scenario favored in the previous section is confirmed, with the 2 → 3 conversion being the slow step.

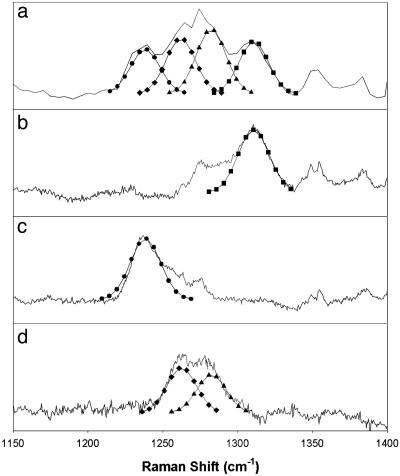

The nature of dioxygen intermediates 2 and 3 was further probed by mixed isotope Raman experiments to determine whether the dioxygen moiety is bound symmetrically or asymmetrically with respect to the metal center. Fig. 5 shows the 1,150- to 1,400-cm–1 region of the Raman spectrum of a sample of 2 obtained from 50% 18O-enriched O2 and compares it with corresponding spectra obtained from pure 16O2 and 18O2. Upon subtraction of the components that arise from the pure isotopomers shown in Fig. 5 b and c, the complex pattern seen in Fig. 5a becomes a doublet with peaks at 1,262 and 1,282 cm–1 (Fig. 5d). The complex pattern in Fig. 5a can thus be fit with four equally intense bands of comparable linewidth at 1,239, 1,262, 1,282, and 1,310 cm–1, which are assigned to the various isotopomers of an end-on bound iron–superoxo unit. Such a well resolved isotopic pattern has not yet been reported for a metal–superoxo complex but is similar to those previously observed for the end-on bound hydroperoxo ligands in oxyhemerythrin (37) and [Fe(N4Py)(η1-OOH)]2+ [N4Py, N,N-bis(2-pyridylmethyl)-bis(2-pyridyl)methylamine] (38) but distinct from the simpler patterns associated with symmetrically bound peroxides in [Fe(N4Py)(η2-OO)]+ (38) and the peroxo intermediates of nonheme diiron enzymes such as the D84E R2 protein of E. coli ribonucleotide reductase (17), fatty acid desaturase (18), and ferritin (19). Unfortunately, no insight into the dioxygen binding mode in 3 could be obtained from a similar analysis of its ν(O–O) features, because of spectral interference from 4 and solvent bands.

Fig. 5.

The ν(O–O) region in the resonance Raman spectra of 2 generated from the reaction of 1 with mixture of 16O2 (25%), 16O18O (50%), and 18O2 (25%) (a); 16O2 (b); or 18O2 (c) in CD2Cl2 at –80°C. All of the spectra were obtained at 77 K with an excitation wavelength of 647.1 nm. (d) Difference spectrum obtained by subtraction of spectra b and c from a. Curves associated with ν(Fe16O-16O) (▪), ν(Fe16O-18O) (▴), ν(Fe18O-16O) (♦), and ν(Fe18O-18O) (•) of comparable linewidth (full width at half maximum ∼ 23 cm–1) were fit by using the program grams/ai (Thermo Galactic).

Other spectroscopic experiments were considered to further establish the nature of 2, but none proved feasible. Intermediate 2 was found to be EPR silent, consistent with the anticipated antiferromagnetic coupling between the superoxide and the incipient diiron(II, III) center that would be expected to form upon one-electron transfer from the precursor diiron(II) center to O2. Alternatively, characterization by Mössbauer and x-ray absorption spectroscopic methods was prevented because of the opacity of the solvent CH2Cl2 to 6- to 14-keV (1 eV = 1.602 × 10–19 J) x-rays. Unfortunately, generation of intermediate 2 (as well as 3) can only be carried out in CH2Cl2.

Reaction with DTBP. The reactivities of 2 and 4 toward DTBP were compared. When DTBP is added to 4 at –60°C, no absorbance change is observed, showing that 4 does not react with this substrate. In contrast, 2 is readily reduced by DTBP at –80°C to generate 3,3′,5,5′-tetra-tert-butyl-2,2′-biphenol as the oxidized product, accompanying the absorbance decrease at 500 and 620 nm. Titration experiments (Fig. 10, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site) show that 0.65 eq of DTBP is consumed upon oxidation. This observation is in good agreement with the 71% value calculated by the kinetic simulation for the fraction of 2 present. Kinetic studies of this reaction show first-order dependencies on [2] and [DTBP] (Fig. 11 and Table 6, which are published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). When d1-DTBP was used, a small kinetic isotope effect of 1.5 was found, suggesting that the oxidation of DTBP involves an O–H bond cleavage component in the rate-determining step.

Discussion

In this work, we have uncovered two intermediates, 2 and 3, in the low-temperature oxygenation of bis(μ-hydroxo)diiron(II) complex 1 to form a (μ-oxo)(μ-1,2-peroxo)diiron(III) species, 4 (Scheme 1). Intermediates 2 and 3 are formulated to be diiron(II,III)-superoxo and diiron(III)-hydroperoxo species, reminiscent of the chemistry of oxyhemerythrin (37). These results afford an unprecedented opportunity to dissect this transformation one electron-transfer step at a time.

Metal-superoxo species are almost always proposed to be formed in the initial dioxygen binding step to the reduced metal center in the oxygen activation mechanisms of metalloenzymes (1–5). Such species have been found in the reactions of O2 with heme proteins and models (6, 7) as well as with one copper enzyme (8) and several synthetic copper and nickel complexes (9–16). Such species have also been invoked in the mechanisms for nonheme iron enzymes, but only indirect evidence has been obtained to date (39–41). The best evidence derives from the observed formation of Fe–NO adducts analogous to the related iron–superoxo complexes in the enzyme mechanisms (42–47). For nonheme diiron proteins, diiron–superoxo species are proposed as the initial intermediates in the oxygenation of the oxygen carrier deoxyhemerythrin to oxyhemerythrin (33, 48) and of reduced methane monooxygenase (designated as intermediate P* or Hsuperoxo) en route to the formation of the peroxo intermediate called P or Hperoxo (39, 49). The trapping and Raman characterization of intermediate 2 in the reaction of 1 with O2 at –80°C in this work provide a documented biomimetic example of a diiron–superoxo complex.

Intermediate 2 exhibits a ν(O–O) band at 1,310 cm–1 that is well separated from the ν(O–O) bands of subsequent peroxo intermediates 3 and 4 near 850 cm–1 (Fig. 4). The ν(O–O) frequency and its 71-cm–1 downshift upon 18O substitution unequivocally assign it as arising from a bound superoxide. Furthermore, the spectral pattern it exhibits in the mixed isotope Raman experiment (Fig. 5) strongly suggests an end-on bound superoxide. The ν(O–O) found for 2 is at least 100 cm–1 higher than those observed for the O2 adducts of heme proteins, synthetic iron porphyrins, and biomimetic copper complexes (Table 2), making 2 the metal–superoxo complex with by far the highest ν(O–O) yet reported. Its high frequency very likely reflects the effect of the three sterically encumbering 6-methyl substituents on the TPA ligand framework that lengthen the Fe–N bonds (50). These substituents give rise to a strongly Lewis acidic iron center and limit the extent to which electron density can be transferred from the metal center to the bound O2. Moreover, this factor probably also inhibits the electron transfer from the other iron(II) center, thereby extending the lifetime of 2 and allowing it to be observed.

More quantitative insight can be obtained from the Eyring plots (Fig. 3) for the individual steps in the transformation of 1 to 4. The activation enthalpy for the 1 → 2 step is quite small (≈16 kJ·mol–1) but comparable to those for the oxygenation of hemerythrin and most of the nonheme diiron model compounds (Table 1). However, the activation entropy for the 1 → 2 step is significantly larger than many of the other values in Table 1, probably because of the severe steric congestion about the diiron(II) center that requires appreciable structural reorganization for dioxygen binding (24). In contrast, the 2 → 3 step has a much higher activation enthalpy, ΔH‡ = 56 ± 3 kJ·mol–1, and a much smaller activation entropy, ΔS‡ =–25 ± 15 J·mol–1·K–1. Thus, 2 can be accumulated by increasing the O2 concentration to accelerate the 1 → 2 step and lowering the temperature to slow down the 2 → 3 step more than the 1 → 2 step. Indeed, kinetic simulations estimate 71% as the maximal fraction of 2 that can form at –80°C.

Kinetic analysis shows strong evidence for yet another intermediate, 3, the most fleeting of the three observed in this reaction sequence. Nevertheless, 3 can be identified by its Raman features as a peroxo intermediate that is distinct from 4. Given the proposed structures for 2 and 4, the most logical structural postulate for 3 is that suggested in Scheme 1, wherein the bound superoxide of 2 is converted to a hydroperoxide in 3. Given the negligible observed kinetic isotope effect associated with the 2 → 3 step, the larger activation enthalpy associated with this step very likely derives not from hydrogen-atom transfer, but from a proton-coupled electron transfer that is modulated by the redox potential of the remaining iron(II) center. A mechanism analogous to the 1 → 2 and 2 → 3 steps has been proposed by Solomon and Brunold (33, 48) on the basis of density functional theory calculations for the formation of oxyhemerythrin. Indeed, the vibrational features of 3 are quite similar to those of oxyhemerythrin and its models (Table 2) (33–35). However, unlike for oxyhemerythrin (37, 51), direct spectroscopic evidence for the proposed Fe-η1-OOH mode could not be obtained for 3.

Lastly, the trapping of 2 has allowed us to investigate its reactivity. We have found it to react with DTBP at –80°C, in contrast to 4, which is completely inert toward this substrate at –60°C. This contrasting behavior demonstrates that 2 is in fact a more reactive species than 4. The oxidation of DTBP by 2 occurs with a kinetic isotope effect of 1.5, strongly implicating a proton-coupled electron-transfer mechanism (52–54), in line with the negligible kinetic isotope effect for the 2 → 3 conversion. Efforts to determine the nature of the diiron reaction product and detailed kinetic analyses are in progress. The observed oxidative reactivity of this diiron–superoxo complex follows recent postulates that a copper–superoxo species may act as the hydrogen-atom abstracting agent in the cleavage of the substrate C–H bond in the mechanism of peptidylglycine α-hydroxylating monooxygenase (55, 56). A Cu-η1-O2 adduct has recently been observed crystallographically for this enzyme (8), and its 11-Å distance to the other copper center has made it difficult to imagine an efficient electron-transfer pathway to form a putative copper(II)-peroxo or hydroperoxo oxidant. Therefore, our observation that 2 can carry out one-electron oxidation of DTBP, whereas 4 cannot, supports the emerging realization that metal–superoxo complexes may play a more important role in dioxygen activation mechanisms than previously perceived.

In summary, we have identified two intermediates, 2 and 3, in the oxygenation of [Fe2(μ-OH)2(6-Me3-TPA)2](OTf)2 (1) in CH2Cl2 at –80°C. Intermediate 2 has been assigned as a diiron(II, III) complex with an end-on bound superoxide, whereas intermediate 3 is proposed to be a diiron(III)-hydroperoxide complex with a structure similar to oxyhemerythrin. The discovery of 2 and associated kinetic studies support the initial steps in postulated oxygen activation mechanisms for nonheme diiron enzymes and, moreover, provide a unique opportunity to scrutinize experimentally the oxygenation of a diiron(II) center, one electron-transfer step at a time.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant GM-38767.

Author contributions: X.S. and L.Q. designed research; X.S. performed research; X.S. analyzed data; and X.S. and L.Q. wrote the paper.

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

Abbreviations: 6-Me3-TPA, Tris(6-methyl-2-pyridylmethyl)amine; DTBP, 2,4-di-tert-butylphenol.

References

- 1.Lippard, S. J. & Berg, J. M. (1994) Principles of Bioinorganic Chemistry (University Science Books, Mill Valley, CA).

- 2.Sono, M., Roach, M. P., Coulter, E. D. & Dawson, J. H. (1996) Chem. Rev. 96, 2841–2887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ferguson-Miller, S. & Babcock, G. T. (1996) Chem. Rev. 96, 2889–2907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blackman, A. G. & Tolman, W. B. (2000) Struct. Bonding 97, 179–211. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Costas, M., Mehn, M. P., Jensen, M. P. & Que, L., Jr. (2004) Chem. Rev. 104, 939–986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Momenteau, M. & Reed, C. A. (1994) Chem. Rev. 94, 659–698. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schlichting, I., Berendzen, J., Chu, K., Stock, A. M., Maves, S. A., Benson, D. E., Sweet, R. M., Ringe, D., Petsko, G. A. & Sligar, S. G. (2000) Science 287, 1615–1622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Prigge, S. T., Eipper, B. A., Mains, R. E. & Amzel, L. M. (2004) Science 304, 864–867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fujisawa, K., Tanaka, M., Moro-oka, Y. & Kitajima, N. (1994) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 116, 12079–12080. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Spencer, D. J. E., Aboelella, N. W., Reynolds, A. M., Holland, P. L. & Tolman, W. B. (2002) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 124, 2108–2109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen, P., Root, D. E., Campochiaro, C., Fujisawa, K. & Solomon, E. I. (2003) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 125, 466–474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jazdzewski, B. A., Reynolds, A. M., Holland, P. L., Young, V. G., Kaderli, S., Zuberbühler, A. D. & Tolman, W. B. (2003) J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 8, 381–393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weitzer, M., Schindler, S., Brehm, G., Schneider, S., Hörmann, E., Jung, B., Kaderli, S. & Zuberbühler, A. D. (2003) Inorg. Chem. 42, 1800–1806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Komiyama, K., Furutachi, H., Nagatomo, S., Hashimoto, A., Hayashi, H., Fujinami, S., Suzuki, M. & Kitagawa, T. (2004) Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 77, 59–72. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schatz, M., Raab, V., Foxon, S. P., Brehm, G., Schneider, S., Reiher, M., Holthausen, M. C., Sundermeyer, J. & Schindler, S. (2004) Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 43, 4360–4363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fujita, K., Schenker, R., Gu, W., Brunold, T. C., Cramer, S. P. & Riordan, C. G. (2004) Inorg. Chem. 43, 3324–3326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moënne-Loccoz, P., Baldwin, J., Ley, B. A., Loehr, T. M. & Bollinger, J. M., Jr. (1998) Biochemistry 37, 14659–14663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Broadwater, J. A., Ai, J., Loehr, T. M., Sanders-Loehr, J. & Fox, B. G. (1998) Biochemistry 37, 14664–14671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moënne-Loccoz, P., Krebs, C., Herlihy, K., Edmondson, D. E., Theil, E. C., Huynh, B. H. & Loehr, T. M. (1999) Biochemistry 38, 5290–5295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tshuva, E. Y. & Lippard, S. J. (2004) Chem. Rev. 104, 987–1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.MacMurdo, V. L., Zheng, H. & Que, L., Jr. (2000) Inorg. Chem. 39, 2254–2255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dong, Y., Zang, Y., Kauffmann, K., Shu, L., Wilkinson, E. C., Münck, E. & Que, L., Jr. (1997) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 119, 12683–12684. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kryatov, S. V., Rybak-Akimova, E. V., MacMurdo, V. L. & Que, L., Jr. (2001) Inorg. Chem. 40, 2220–2228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kryatov, S. V., Taktak, S., Korendovych, I. V., Rybak-Akimova, E. V., Kaizer, J., Torelli, S., Shan, X., Mandal, S., MacMurdo, V., Mairata i Payeras, A. & Que, L., Jr. (2005) Inorg. Chem. 44, 85–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Battino, R. (1981) Oxygen and Ozone (Pergamon, New York).

- 26.Petrou, A. L., Armstrong, F. A., Sykes, A. G., Harrington, P. C. & Wilkins, R. G. (1981) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 670, 377–384. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lloyd, C. R., Eyring, E. M. & Ellis, W. R., Jr. (1995) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 117, 11993–11994. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Feig, A. L., Becker, M., Schindler, S., van Eldik, R. & Lippard, S. J. (1996) Inorg. Chem. 35, 2590–2601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Costas, M., Cady, C. W., Kryatov, S. V., Ray, M., Ryan, M. J., Rybak-Akimova, E. V. & Que, L., Jr. (2003) Inorg. Chem. 42, 7519–7530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Herold, S. & Lippard, S. J. (1997) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 119, 145–156. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kryatov, S. V., Chavez, F. A., Reynolds, A. M., Rybak-Akimova, E. V., Que, L., Jr., & Tolman, W. B. (2004) Inorg. Chem. 43, 2141–2150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bajdor, K., Oshio, H. & Nakamoto, K. (1984) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 106, 7273–7274. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brunold, T. C. & Solomon, E. I. (1999) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 121, 8277–8287. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mizoguchi, T. J. & Lippard, S. J. (1998) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 120, 11022–11023. [Google Scholar]

- 35.He, C., Barrios, A. M., Lee, D., Kuzelka, J., Davydov, R. M. & Lippard, S. J. (2000) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 122, 12683–12690. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wada, A., Ogo, S., Nagatomo, S., Kitagawa, T., Watanabe, Y., Jitsukawa, K. & Masuda, H. (2002) Inorg. Chem. 41, 616–618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Klotz, I. M. & Kurtz, D. M., Jr. (1984) Acc. Chem. Res. 17, 16–22. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Roelfes, G., Vrajmasu, V., Chen, K., Ho, R. Y. N., Rohde, J.-U., Zondervan, C., la Crois, R. M., Schudde, E. P., Lutz, M., Spek, A. L., et al. (2003) Inorg. Chem. 42, 2639–2653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lee, S.-K. & Lipscomb, J. D. (1999) Biochemistry 38, 4423–4432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chiou, Y.-M. & Que, L., Jr. (1995) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 117, 3999–4013. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mehn, M. P., Fujisawa, K., Hegg, E. L. & Que, L., Jr. (2003) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 125, 7828–7842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Arciero, D. M., Orville, A. M. & Lipscomb, J. D. (1985) J. Biol. Chem. 260, 14035–14044. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chen, V. J., Orville, A. M., Harpel, M. R., Frolik, C. A., Surerus, K. K., Münck, E. & Lipscomb, J. D. (1989) J. Biol. Chem. 264, 21677–21681. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Haskin, C. J., Ravi, N., Lynch, J. B., Munck, E. & Que, L., Jr. (1995) Biochemistry 34, 11090–11098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rocklin, A. M., Tierney, D. L., Kofman, V., Brunhuber, N. M. W., Hoffman, B. M., Christoffersen, R. E., Reich, N. O., Lipscomb, J. D. & Que, L., Jr. (1999) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96, 7905–7909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rodriguez, J. H., Xia, Y.-M. & Debrunner, P. G. (1999) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 121, 7846–7863. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Coufal, D. E., Tavares, P., Pereira, A. S., Hyunh, B. H. & Lippard, S. J. (1999) Biochemistry 38, 4504–4513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Brunold, T. C. & Solomon, E. I. (1999) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 121, 8288–8295. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gherman, B. F., Baik, M.-H., Lippard, S. J. & Friesner, R. A. (2004) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 126, 2978–2990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zang, Y., Kim, J., Dong, Y., Wilkinson, E. C., Appelman, E. H. & Que, L., Jr. (1997) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 119, 4197–4205. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shiemke, A. K., Loehr, T. M. & Sanders-Loehr, J. (1984) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 106, 4951–4956. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rhile, I. J. & Mayer, J. M. (2004) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 126, 12718–12719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Osako, T., Ohkubo, K., Taki, M., Tachi, Y., Fukuzumi, S. & Itoh, S. (2003) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 125, 11027–11033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Huang, H., Sommerfeld, D., Dunn, B. C., Eyring, E. M. & Lloyd, C. R. (2001) J. Phys. Chem. A 105, 3536–3541. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chen, P. & Solomon, E. I. (2004) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 126, 4991–5000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Evans, J. P., Ahn, K. & Klinman, J. P. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 49691–49698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.