Abstract

Introduction

Recent studies report racial disparities among individuals in organized colorectal cancer (CRC) programs; however, there is a paucity of information on CRC screening utilization by race/ethnicity among newly age-eligible adults in such programs.

Methods

This was a retrospective cohort study among Kaiser Permanente Northern California enrollees who turned age 50 years between 2007 and 2012 (N=138,799) and were served by a systemwide outreach and facilitated in-reach screening program based primarily on mailed fecal immunochemical tests to screening-eligible people. Kaplan-Meier and Cox model analyses were used to estimate differences in receipt of CRC screening in 2015–2016.

Results

Cumulative probabilities of CRC screening within 1 and 2 years of subjects’ 50th birthday were 51% and 73%, respectively. Relative to non-Hispanic whites, the likelihood of completing any CRC screening was similar in blacks (hazard ratio, 0.98; 95% CI=0.96, 1.00), 5% lower in Hispanics (hazard ratio, 0.95; 95% CI=0.93, 0.96), and 13% higher in Asians (hazard ratio, 1.13; 95% CI=1.11, 1.15) in adjusted analyses. Fecal immunochemical testing was the most common screening modality, representing 86% of all screening initiations. Blacks and Hispanics had lower receipt of fecal immunochemical testing in adjusted analyses.

Conclusions

CRC screening uptake was high among newly screening-eligible adults in an organized CRC screening program, but Hispanics were less likely to initiate screening near age 50 years than non-Hispanic whites, suggesting that cultural and other individual-level barriers not addressed within the program likely contribute. Future studies examining the influences of culturally appropriate and targeted efforts for screening initiation are needed.

INTRODUCTION

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most common cancer and second leading cause of cancer death in the U.S.1 Despite its effectiveness, CRC screening remains underutilized. Fifty-eight percent of eligible adults were up to date with recommended CRC screening in 2013, a level well below nationwide screening goals.2,3 CRC screening is especially underutilized in racial/ethnic minorities including Asians and Hispanics where less than 45% of people in these groups are reported to be up to date with CRC screening versus 60% in whites.4,5 Blacks have historically had lower CRC screening prevalence than whites, a disparity that has been the focus of several studies given the higher disease burden in this group.5–10 Factors contributing to lower CRC screening uptake in racial/ethnic minorities are complex but could be addressed through programs that improve awareness and access to health care, and mitigate cultural and logistic barriers to receiving needed services.11–14 Further, delay in screening initiation can contribute to disparities and may predict future cancer screening behaviors.15 Thus, timely screening initiation can be an important target of intervention for boosting screening rates in diverse populations. However, the impact of such programs and screening initiation has not been well studied.

In 2007, Kaiser Permanente Northern California (KPNC), an integrated health system that insures and provides health care, launched a CRC screening program using population health management approaches. The program identifies screening-eligible average-risk adults and mails a fecal immunochemical test (FIT) kit annually to their home address. An in-reach component reminds individuals and offers screening at healthcare encounters. Despite rapid CRC screening uptake throughout the program, recent studies of the program reported lower odds of CRC screening in blacks and Hispanics relative to whites, calling for increased understanding of these differences.16,17 Thus, the objective of the present study was to examine time to receipt of CRC screening from age 50 years in a program with uniform population health approaches to delivery of screening according to race/ethnicity. Detailed patterns of the type of test utilized to better understand potential racial differences in CRC screening within the organized screening program were also examined.

METHODS

Study Population

Data on KPNC enrollees who turned age 50 years between 2007 and 2012, after the program was in place, were used in this study. KPNC provides health care to >3.8 million people annually (representing about 22% of Northern California’s adults aged 22–64 years18) across 17 medical centers in the region. KPNC’s CRC screening activities and population health management methods have been described previously.16,19 Briefly, at the program’s onset in 2007, FIT kits, along with instructions, were mailed to randomly selected adults who were not up to date with recommended CRC screening in weekly batches during the first 9–10 months of each calendar year. The goal is to screen all eligible people by the end of a person’s 51st birth year, in accordance with Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set measures.20 Several years into the program, FIT kits were mailed on or near their 50th birthday. Non-responders received phone or mailed reminders. Electronic medical record reminders were used to offer screening during in-person healthcare visits, hereafter referred to as in-reach screening. Approval for this study was obtained from IRBs at KPNC and Emory University.

People who had prior CRC, colorectal surgery, or inflammatory bowel disease diagnosis, or a strong family history of heredity cancers were excluded as were individuals who had received colonoscopy, FIT, or sigmoidoscopy prior to their 50th birthday; were enrolled in KPNC for <12 months; lived outside the KPNC service area; or had missing data on race/ethnicity or other key covariates.

Measures

The outcome was time to the receipt of the first CRC screening test (FIT, colonoscopy, or sigmoidoscopy) after age 50 years. Receipt of FIT and mailing dates were based on electronic laboratory and mailing records, respectively. Current Procedural Terminology and ICD codes were used to identify colonoscopy and sigmoidoscopy.

The primary independent variable was race/ethnicity categorized as non-Hispanic white (white), non-Hispanic black (black), Hispanic, Asian or Pacific Islanders (Asian), Native American, and multiple races. To account for changes in screening initiation throughout the program, year of a person’s 50th birthday (2007, 2008, 2009, 2010, 2011, and 2012) was included as a covariate. Insurance payer (commercial, Medicaid, Medicare, and other) and Census tract poverty indices (low [0%–3.9%], medium [4%–7.9%], and high [≥8%]) were used as markers of SES. Preferred language (English/non-English) was used as measure of acculturation. Additional covariates included family history of CRC according to electronic medical records, geographic region where a person received the majority of their health care (medical service area), gender, Charlson comorbidity score (categorized as 0, 1, ≥2), and BMI category.21

Statistical Analysis

Chi-square and Wilcoxon signed rank tests (with α=0.05 for significance) were used to examine differences in subjects’ characteristics according to race/ethnicity. People were followed from their 50th birthday until the earliest of receipt of a CRC screening, date of death, date when no longer enrolled in KPNC, or the end of the follow-up period (December 31, 2013). Kaplan–Meier product-limit estimator with log-rank statistics were used to derive the cumulative probability of receipt of CRC screening according to race/ethnicity. Among individuals receiving FIT, the time from their 50th birthday until they were mailed a FIT kit was calculated and used to represent “program” delays and the time from receiving a FIT and the lab date was used to represent “individual” delays. To determine potential differences in receipt of FIT in outreach versus in-reach settings, FIT occurring before the first mailed kit was categorized as “in-reach” whereas FIT following a mailed kit was deemed to occur through “outreach.”

Cox proportional hazard models were used to estimate hazard ratios (HRs) and corresponding 95% CIs. A series of models were performed to evaluate for potential attenuation of the association between race/ethnicity and CRC screening initiation by covariates. Each model accounted for clustering of people within medical service areas using a sandwich covariance estimator. The proportional hazard assumption was tested using log–log survival curves as well as log–time and covariate interaction terms. Insurance type and year of 50th birthday violated these assumptions and were adjusted for in-strata. Interactions between race/ethnicity and all other covariates were examined.

Several sensitivity analyses were conducted. Subdistribution hazard models, accounting for competing events such as deaths, were carried out.22 For test-specific models, receipt of testing modalities other than the outcome of interest were deemed as competing events as well. Log binomial models were used to assess whether differences in follow-up time influenced results. Analyses of FIT among people who were mailed FIT kits were used to help determine if receipt of a mailed FIT kits accounted for potential differences in CRC screening. Additionally, models adjusting for receipt of a mailed FIT kit were conducted among people who had not been screened by their 51st birthday. Statistical analyses were performed with SAS, version 9.3 and Stata SE, version 12 in 2015 and 2016.

RESULTS

There were 234,265 adults who turned age 50 years between 2007 and 2013 in KPNC who were potentially eligible for this study. After exclusions, the final analytic sample contained 138,799 individuals (Appendix Table 1). Among this sample, 56.7% were white, 8.2% were black, 17.4% were Hispanic, 16.8% were Asian, and <2% were Native American or coded as multiracial (Table 1). Blacks and Hispanics were more likely to be insured through Medicaid or reside in higher-poverty areas, and tended to have more comorbid conditions than whites and Asians. The average number of months enrolled in KPNC since a person’s 50th birthday was shorter in Hispanics (44.7 months, p<0.001) and blacks (45.8 months, p=0.014) compared with whites (46.3 months).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Newly Eligible Enrollees for Colorectal Cancer Screening, Kaiser Permanente Northern California 2007–2012 (n=138,799)

| Categories | Total | White | Black | Hispanic | Asian | Native American | Multiple races | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||||

| N=138,799 N (%) |

N=78,728 N (%) |

N=11,328 N (%) |

N=24,160 N (%) |

N=23,386 N (%) |

N=489 N (%) |

N=708 N (%) |

||

| Year of 50th birthday | ||||||||

| 2007 | 23,040 (16.6) |

13,594 (17.3) |

1,839 (16.2) |

3,735 (15.5) |

3,687 (15.8) |

80 (16.4) |

105 (14.8) |

0.0001 |

| 2008 | 23,259 (16.8) |

13,391 (17) |

1,926 (17) |

3,976 (16.5) |

3,784 (16.2) |

67 (13.7) |

115 (16.2) |

|

| 2009 | 23,567 (17) |

13,570 (17.2) |

1,928 (17) |

4,012 (16.6) |

3,836 (16.4) |

76 (15.5) |

145 (20.5) |

|

| 2010 | 23,933 (17.2) |

13,535 (17.2) |

2,009 (17.7) |

4,161 (17.2) |

4,002 (17.1) |

105 (21.5) |

121 (17.1) |

|

| 2011 | 22,770 (16.4) |

12,724 (16.2) |

1,861 (16.4) |

4,123 (17.1) |

3,870 (16.5) |

75 (15.3) |

117 (16.5) |

|

| 2012 | 22,230 (16) |

11,914 (15.1) |

1,765 (15.6) |

4,153 (17.2) |

4,207 (18) |

86 (17.6) |

105 (14.8) |

|

| Male | 62,055 (44.7) |

35,544 (45.1) |

4,842 (42.7) |

11,099 (45.9) |

10,023 (42.9) |

232 (47.4) |

315 (44.5) |

0.0001 |

| Insurance category | ||||||||

| Commercial | 121,84 1 (87.8) |

68,557 (87.1) |

9,964 (88) |

21,368 (88.4) |

20,911 (89.4) |

417 (85.3) |

624 (88.1) |

0.0001 |

| High deductible commercial | 7,397 (5.3) |

5,117 (6.5) |

158 (14) |

971 (4) |

1,094 (4.7) |

25 (5.1) |

32 (4.5) |

|

| Medicare+Commercial | 7,187 (5.2) |

3,857 (4.9) |

810 (7.2) |

1,377 (5.7) |

1,071 (4.6) |

36 (7.4) |

36 (5.1) |

|

| Medicaid | 1,190 (0.9) |

526 (0.7) |

326 (2.9) |

207 (0.9) |

118 (0.5) |

a | a | |

| Other | 1,184 (0.9) |

671 (0.9) |

70 (0.6) |

237 (1) |

192 (0.8) |

a | a | |

| Language preference | ||||||||

| Not English | 11,250 (8.1) |

614 (0.8) |

53 (0.5) |

6,879 (28.5) |

3,675 (15.7) |

20 (4.1) |

a | 0.0001 |

| English | 122,16 2 (88) |

75,069 (95.4) |

10,635 (93.9) |

16,335 (67.6) |

19,012 (81.3) |

451 (92.2) |

660 (93.2) |

|

| Missing | 5,387 (3.9) |

3,045 (3.9) |

640 (5.6) |

946 (3.9) |

699 (3) |

18 (3.7) |

39 (5.5) |

|

| BMI category | ||||||||

| Underweight | 958 (0.7) |

529 (0.7) |

35 (0.3) |

57 (0.2) |

333 (14) |

a | a | 0.0001 |

| Normal | 37,575 (27.1) |

21,514 (27.3) |

1,514 (13.4) |

3,811 (15.8) |

10,477 (44.8) |

a | a | |

| Overweight | 50,253 (36.2) |

27,988 (35.6) |

3,610 (31.9) |

9,135 (37.8) |

9,097 (38.9) |

155 (31.7) |

268 (37.9) |

|

| Obese | 50,013 (36) |

28,697 (36.5) |

6,169 (54.5) |

11,157 (46.2) |

3,479 (14.9) |

246 (50.3) |

265 (37.4) |

|

| Charlson Comorbidity Score | ||||||||

| 0 | 114,375 (82.4) |

66,449 (84.4) |

8,793 (77.6) |

19,029 (78.8) |

19,168 (82) |

389 (79.6) |

547 (77.3) |

0.0001 |

| 1 | 17,055 (12.3) |

8,714 (111) |

1,662 (14.7) |

3,547 (14.7) |

2,945 (12.6) |

73 (14.9) |

114 (16.1) |

|

| ≥2 | 7,369 (5.3) |

3,565 (4.5) |

873 (7.7) |

1,584 (6.6) |

1,273 (5.4) |

27 (5.5) |

47 (6.6) |

|

| Family history documented | 7,294 (5.3) |

4,463 (5.7) |

692 (6.1) |

981 (4.1) |

1,107 (4.7) |

21 (4.3) |

30 (4.2) |

0.0001 |

| Area-based poverty | ||||||||

| Low 0–3.9% | 51,455 (37.1) |

33,111 (42.1) |

2,601 (23) |

6,419 (26.6) |

8,917 (38.1) |

147 (30.1) |

260 (36.7) |

0.0001 |

| Med 4–7.9% | 40,627 (29.3) |

23,806 (30.2) |

2,549 (22.5) |

6,629 (27.4) |

7,291 (31.2) |

141 (28.8) |

211 (29.8) |

|

| High >=8% | 46,717 (33.7) |

21,811 (27.7) |

6,178 (54.5) |

11,112 (46) |

7,178 (30.7) |

201 (41.1) |

237 (33.5) |

|

| Testing characteristics | ||||||||

| Received CRC screening before the end of followup | 114,949 (82.8) |

65,102 (82.7) |

9,220 (81.4) |

19,361 (80.1) |

20,296 (86.8) |

383 (78.3) |

587 (82.9) |

0.0001 |

| Type of test among individuals who completed a CRC screening test | ||||||||

| FIT | 98,453 (85.6) |

55,911 (85.9) |

7,505 (81.4) |

16,724 (86.4) |

17,472 (86.1) |

340 (88.8) |

501 (85.3) |

0.0001 |

| Sigmoidoscopy | 6,749 (5.9) |

3,953 (6.1) |

638 (6.9) |

1,021 (5.3) |

1,086 (5.4) |

14 (3.7) |

37 (6.3) |

|

| Colonoscopy | 9,747 (8.5) |

5,238 (8) |

1,077 (117) |

1,616 (8.3) |

1,738 (8.6) |

29 (7.6) |

49 (8.3) |

|

| Mailed a FIT kit at least once before follow-up | 119,925 (86.4) |

68,245 (86.7) |

9,621 (84.9) |

21,110 (87.4) |

19,906 (85.1) |

419 (85.7) |

624 (88.1) |

0.0001 |

| Time followed in study | Mean (SD) |

Mean (SD) |

Mean (SD) |

Mean (SD) |

Mean (SD) |

Mean (SD) |

Mean (SD) |

|

| Months followed until CRC screening or censoring | 17.6 (16.57) |

17.9 (16.71) |

18.5 (17.07) |

18.6 (16.99) |

15.4 (15.16) |

18.7 (16.72) |

18 (16.91) |

|

| Months followed from 50th birthday until no longer enrolled in KPNC | 45.8 (20.58) |

46.3 (20.57) |

45.8 (20.42) |

44.7 (20.5) |

45.1 (20.72) |

44.2 (20.55) |

46.7 (20.2) |

|

Note: Boldface indicates statistical significance (p<0.05).

Data suppressed to protect individuals’ confidentiality (fewer than 11 respondents included)

CRC, colorectal cancer; FIT, fecal immunochemical test; HD, high deductible

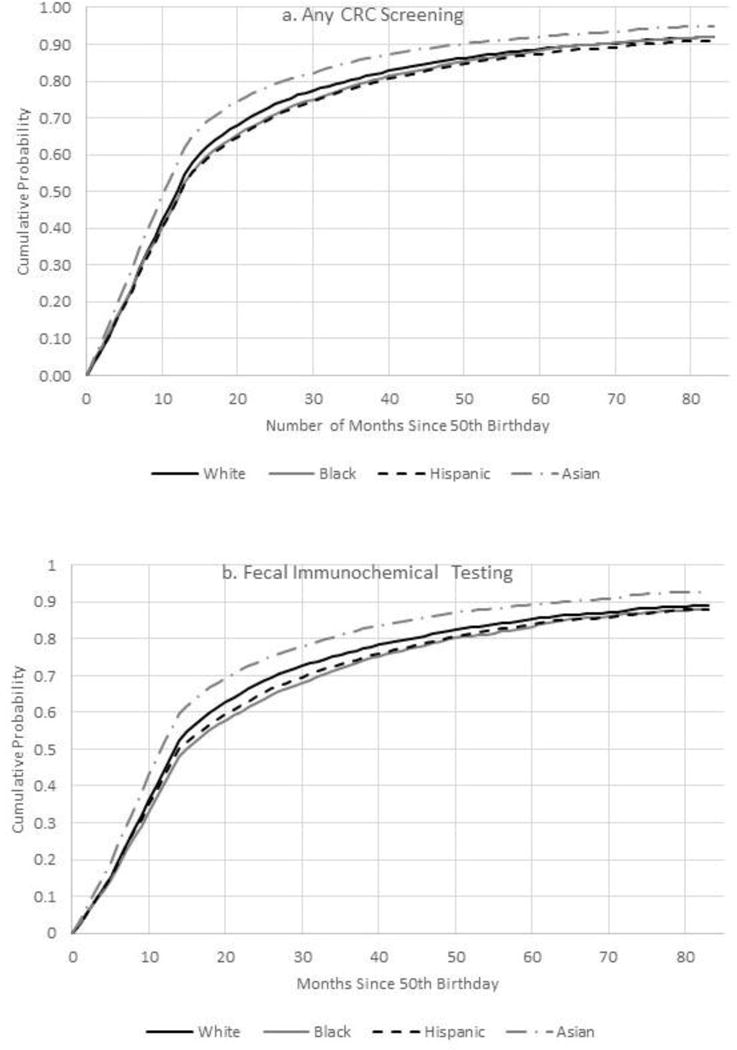

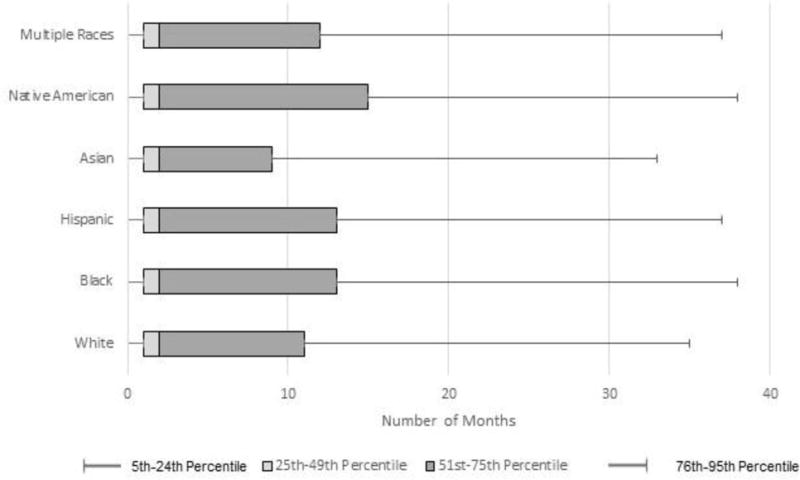

The overall cumulative probabilities of any CRC screening within 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, and 7 years of a person’s 50th birthday were 50.9%, 72.9%, 81.1%, 85.9%, 89.0%, 91.1%, and 92.2%, respectively. By the end of follow-up, the cumulative probability of receiving any CRC screening modality was highest in Asians (94.8%), followed by whites (91.9%), multiracial (91.9%), blacks (91.8%), Hispanics (90.9%), and Native Americans (90.9%) (p-value<0.001) (Figure 1A). In multivariable Cox models, relative to whites, the likelihood of initiating CRC screening was similar in blacks (HR=0.98, 95% CI=0.96, 1.00), 5% lower in Hispanics (HR=0.95, 95% CI=0.93, 0.96), and 13% higher in Asians (HR=1.13, 95% CI=1.11, 1.15) (Table 2). Results from models accounting for competing events were generally similar (Appendix Table 1) as were log binomial models indicating that differences in competing events and follow-up did not account for the variations in CRC screening utilization by race/ethnicity, respectively (Appendix Tables 2 and 3).

Figure 1.

A–D. Cumulative probability of colorectal testing by type of test, Kaiser Permanente Northern California 2007–2012.a

aNote lines for blacks (solid grey) and Hispanics (dashed line in black) overlap. Lines for white, black, Hispanic, and Asian are only displayed to improve visibility.

CRC, colorectal cancer

Table 2.

Adjusted Models for Colorectal Cancer Screening Among Newly Eligible Enrollees, Kaiser Permanente Northern California 2007-2012

| Model | Any CRC screening | FIT | Colonoscopy | Sigmioidoscipy | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||

| HR | 95% CI | HR | 95% CI | HR | 95% CI | HR | 95% CI | |||||

| Unadjusted Modelsa | ||||||||||||

| White | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||||||

| Black | 0.96 | 0.94 | 0.98 | 0.91 | 0.88 | 0.93 | 1.09 | 1.00 | 1.19 | 1.41 | 1.32 | 1.50 |

| Hispanic | 0.94 | 0.92 | 0.95 | 0.94 | 0.93 | 0.96 | 0.82 | 0.76 | 0.87 | 0.98 | 0.93 | 1.04 |

| Asian | 1.19 | 1.17 | 1.21 | 1.20 | 1.18 | 1.22 | 1.05 | 0.98 | 1.11 | 1.22 | 1.16 | 1.29 |

| Native American | 0.90 | 0.82 | 1.00 | 0.93 | 0.84 | 1.03 | 0.55 | 0.32 | 0.92 | 0.86 | 0.60 | 1.24 |

| Multiple races | 1.00 | 0.92 | 1.09 | 1.00 | 0.91 | 1.09 | 1.04 | 0.75 | 1.43 | 1.04 | 0.79 | 1.38 |

| Partially adjusted modelsb | ||||||||||||

| White | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||||

| Black | 0.97 | 0.95 | 0.99 | 0.94 | 0.92 | 0.97 | 0.99 | 0.90 | 1.08 | 1.19 | 1.11 | 1.28 |

| Hispanic | 0.94 | 0.92 | 0.95 | 0.94 | 0.93 | 0.96 | 0.77 | 0.72 | 0.83 | 1.06 | 1.05 | 1.11 |

| Asian | 1.13 | 1.11 | 1.14 | 1.14 | 1.12 | 1.16 | 0.87 | 0.81 | 0.93 | 1.18 | 1.18 | 1.25 |

| Native American | 0.91 | 0.82 | 1.01 | 0.93 | 0.84 | 1.04 | 0.58 | 0.35 | 0.99 | 0.92 | 0.92 | 1.32 |

| Multiple races | 0.97 | 0.95 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.91 | 1.08 | 1.09 | 0.79 | 1.51 | 0.96 | 0.96 | 1.28 |

| Fully adjusted modelsc | ||||||||||||

| White | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||||

| Black | 0.98 | 0.96 | 1.00 | 0.95 | 0.93 | 0.98 | 1.03 | 0.95 | 1.13 | 1.21 | 1.13 | 1.30 |

| Hispanic | 0.95 | 0.93 | 0.96 | 0.94 | 0.93 | 0.96 | 0.81 | 0.75 | 0.87 | 1.06 | 1.00 | 1.13 |

| Asian | 1.13 | 1.11 | 1.15 | 1.14 | 1.12 | 1.16 | 0.88 | 0.82 | 0.94 | 1.18 | 1.12 | 1.25 |

| Native American | 0.91 | 0.82 | 1.01 | 0.93 | 0.84 | 1.04 | 0.60 | 0.35 | 1.01 | 0.93 | 0.64 | 1.33 |

| Multiple races | 1.00 | 0.92 | 1.09 | 1.00 | 0.91 | 1.09 | 1.10 | 0.80 | 1.53 | 0.97 | 0.73 | 1.29 |

Note: Boldface indicates statistical significance (p<0.05)

Cox Proportional Hazard Models are adjusted for race/ethnicity.

Cox Proportional Hazard Models are adjusted for year of 50th birthday, gender, BMI category, Charlson Comorbidity, family history, service area.

Cox Proportional Hazard Models are adjusted for year of 50th birthday, gender, insurance, language preference, BMI category, Charlson Comorbidity, family history, service area, Census-tract poverty

CRC, colorectal cancer; FIT, fecal immunochemical test; HR, hazard ratio

There was no significant interaction between race/ethnicity and other covariates (data not shown), including language preference, where CRC screening use among English-preferring Asians and Hispanics were similar to their non–English preferring counterparts.

The majority (86.4%) of people were mailed at least one FIT during follow-up. This proportion was slightly lower in blacks (84.9%) relative to whites (86.7%) (Table 1). Among participants who were not mailed a FIT, >93% received CRC screening either through in-reach FIT (44%), colonoscopy (21%), or sigmoidoscopy (29%). The remaining 7% had not received testing before the end of follow-up and a substantial proportion (40%) of these individuals were in the most recent birth cohorts (i.e., turned age 50 years in 2012).

The most common form of CRC screening was FIT, representing 85.6% of initial CRC tests received, and the cumulative probability of FIT ranged from 87.9% in Hispanics to 92.8% in Asians (Figure 1B). In adjusted Cox models compared with whites, receipt of FIT versus having no CRC tests was significantly lower in Hispanics (HR=0.94, 95% CI=0.93, 0.96) and blacks (HR=0.95, 95% CI=0.93, 0.98) but higher in Asians (HR=1.14, 95% CI=1.12, 1.16) (Table 2). Sensitivity analyses adjusting for receipt of a mailed FIT kit among enrollees not screened by their 51st birthday (Appendix Table 4) and analyses restricted to individuals mailed at least one FIT kit (Appendix Table 5) were similar to the main findings.

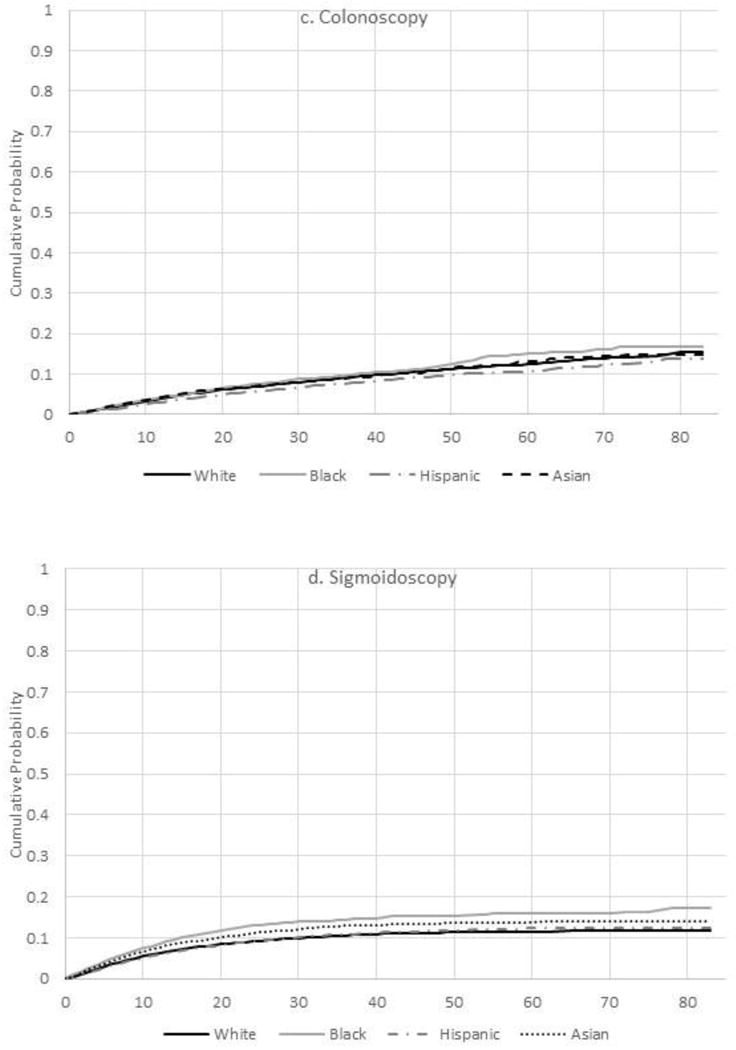

Among those completing FIT, in-reach FIT accounted for 22.6% of all tests and ranged from 21.5% in whites to 26.5% in Asians (p<0.001) (Appendix Table 6). The remaining 77.4% of adults receiving FIT did so through outreach, where the median time from 50th birthday to FIT mailing (i.e., program delay) was 13 months regardless of race/ethnicity. The median time from FIT mailing to laboratory testing (i.e., individual delay) was 2 months and the distribution was left skewed (Figure 2). Individual times to return tended to be longer in Hispanics (p<0.001) and blacks (p<0.001) relative to whites.

Figure 2.

Months from fecal immunochemical test mail to return date, Kaiser Permanente Northern California 2007–2012.a

aThe 5th, 25th, Median, 75th, and 95th percentiles of the number of months from FIT mail date to return date are presented. Wilcoxon Signed Rank Test p-values relative to white: black (p<0.001), Hispanic (p<0.001), Asian (p<0.001), Native American (p=0.002), multiple races (p=0.714). There were 119,925 people included in this graph who were mailed a FIT kit.

FIT, Fecal Immunochemical Test

Colonoscopy was significantly less common among Hispanics (HR=0.81, 95% CI=0.75, 0.87) and Asians (HR=0.88, 95% CI=0.82, 0.94) relative to whites (Table 2). By contrast, sigmoidoscopy use was 41% and 22% greater in blacks and Asians compared with whites, respectively.

DISCUSSION

In the current study of a screening program that used population health management approaches, the cumulative probability of completing CRC screening within 1 and 2 years of becoming age eligible was 51% and 73%, respectively, and approached 90% over a 7-year follow-up period in the program. Hispanics had slightly lower CRC screening uptake compared with whites whereas Asians had higher uptake, a pattern that was consistent throughout the study period. FIT represented a large majority (86%) of all CRC tests as result of the systemwide outreach based primarily on mailed FITs and although most people returned FIT kits in a timely fashion (within 2 months of being mailed a kit), Hispanics and blacks were less likely to return kits before the end of follow-up.

The overall high uptake of CRC screening and only modest differences by race/ethnicity diverge from nationwide patterns and those in California.2,23 For example, among people aged 50–54 years in the National Health Interview Survey and California Health Interview Survey, only 39% and 43% were screened, respectively.4,24 Greater CRC screening use among Asians and marginally lower screening in Hispanics relative to whites in the current study, within an integrated healthcare system with more equal access to care, differs from markedly lower CRC screening prevalence in Asians and Hispanics across the U.S., in the absence of organized screening programs.2,11,25 Additionally, comparable CRC screening uptake in blacks relative to whites in the current study is in contrast to historically lower screening in this group, but is more similar to contemporary data suggesting a narrowing in these differences.17,26

The favorable patterns in the present study were unlikely to be due solely to having insurance, as Asian, blacks, and Hispanics in other insured populations have lower CRC screening adoption relative to whites.7,26,27 These high screening rates are likely due to a variety of mechanisms stemming from the population health management strategies used.16 First, mailed introductory letters and FIT kits serve as a reminder and increase awareness of the need to be screened, which may account for higher CRC screening among Asians who tend to have positive attitudes toward screening when presented with the opportunity.28 Second, screening through outreach potentially overcomes competing demands during a clinical encounter including in those with comorbid conditions that do not preclude a benefit from screening, or a provider screening recommendation, which are barriers in Hispanics and blacks in other settings.29 Additionally, a mailed FIT is non-invasive, and does not require an individual to take time off work or incur opportunity costs, making it an easily accessible option for newly eligible adults. This tactic may be particularly salient for Hispanics and blacks who tend to be employed in service-and production-related industries with limited paid time off benefits30,31.

Despite these encouraging results, blacks and Hispanics were still somewhat less likely to return FIT kits, which was not a result of differences in the presumed opportunity to be screened. The overall probabilities of being mailed a FIT kit and the average time from 50th birthday to mailing was 13 months, a timeframe reflecting Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set measures, were uniform across racial and ethnic groups. These results suggests that factors such as beliefs, attitudes, and perceptions of CRC screening not addressed in the current organized screening program could play a role.11,32,33 Specific barriers described among Hispanics include embarrassment and fear of tests as well as perceptions that screening is not needed in the absence of symptoms.35–37 Hispanics are also more likely than whites to report that they would delay stool-based testing if a doctor gave it to them.28 Unlike previous investigations,11,33 language preference did not predict CRC screening or modify the association between Hispanic ethnicity and CRC screening in the current study, likely reflecting the insured population-and language-specific outreach instructions. In other studies, blacks reported fear and embarrassment as obstacles to screening in addition to mistrust in the medical system.37 Some of these barriers may be addressed with more-tailored and -targeted approaches38,39; however, the effectiveness and the cost-benefit of adjuvant program components has not been investigated and warrants future study.

Two previous studies of KPNC enrollees aged 50–75 years noted lower CRC screening utilization among Hispanics and blacks relative to whites, although these did not evaluate initial screening uptake as in the current study.16,17 In the current study, similar findings for newly screening-eligible Hispanics were observed, though, black–white differences were confined to FIT and sigmoidoscopy testing.18 The lack of black-white differences in colonoscopy in the present study could be related to lower frequency of use of colonoscopy among newly screening-eligible adults. Greater use of sigmoidoscopy in blacks and Asians compared with whites was a finding consistent with previous studies indicating slower transition to newer medical technologies in racial/ethnic minorities.16,40 A previous study of newly screening-eligible enrollees in an integrated health system located in Washington state who received mailed and in-person clinic reminders reported similar CRC screening uptake in blacks and Hispanics. These discrepant findings could result from differences in sample size and composition as well as programmatic factors.41

Limitations

There are some limitations of this study. First, some tests may have been done for non-screening indications, although this would be less likely with outreach programs. Second, people excluded because of missing race/ethnicity information (n=14,947) had lower CRC screening use (63%) compared with people with non-missing race/ethnicity (>90%). If racial/ethnic minorities were over-represented in those with these missing data, then disparities observed in the current study are likely a conservative estimate. Incorporating individuals with missing race/ethnicity dampened the estimated overall receipt of CRC screening, marginally, to 89%. There are ongoing efforts in KPNC to improve the completeness of these data in medical records, including the expansion racial/ethnic categories that minorities may feel more comfortable reporting or identify with.42 During the time of the current study, data on specific ethnicity or country of origin (e.g., Korean for Asians and Mexican for Hispanics) were not available.25,43 Though, there is evidence that the concordance between race recorded in medical records and self-reported data is good to excellent in KPNC.44 It was also assumed that mailed FIT kits were delivered with no information regarding delivery confirmation. Additionally, area-based poverty measures were used, which may be discordant with individual-level SES; however, area-based indicators are correlated with health behaviors.45 Lastly, results from KPNC’s integrated health system may not be generalizable to other healthcare settings, although programmatic approaches to cancer screening are widely used in different types of healthcare delivery systems.

CONCLUSIONS

Among adults who newly became screening eligible in KPNC’s program, CRC screening uptake was considerably higher and differences by race/ethnicity were modest and narrower than previously reported in the overall U.S. or California populations. However, Hispanics were still less likely to be screened than whites, which could be due to factors not addressed in the current population health management approach, but may be addressed using other methods such as tailored and targeted culturally appropriate messaging. The effectiveness and cost–benefit of adjuvant program components in the current study population have not been investigated and warrant future study.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was conducted within the National Cancer Institute-funded Population-based Research Optimizing Screening through Personalized Regimens consortium, which conducts multisite, coordinated, transdisciplinary research to evaluate and improve cancer screening processes and supported by a grant from the National Cancer Institute at NIH (#U54 CA163262). Funding for data analysis and manuscript preparation was provided by the American Cancer Society’s Department of Intramural Research.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

No financial disclosures were reported by the authors of this paper.

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2015. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65(1):5–29. doi: 10.3322/caac.21254. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fedewa SA, Sauer AG, Siegel RL, Jemal A. Prevalence of Major Risk Factors and Use of Screening Tests for Cancer in the United States. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2015;24(4):637–652. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-15-0134. https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-15-0134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Colorectal Cancer Roundtable. 2016 http://nccrt.org/about/

- 4.DHHS US. National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) Public Use Data Release. Hyattsville, MD: U.S. DHHS; 2013. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shapiro JA, Klabunde CN, Thompson TD, Nadel MR, Seeff LC, White A. Patterns of colorectal cancer test use, including CT colonography, in the 2010 National Health Interview Survey. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2012;21(6):895–904. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-12-0192. https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-12-0192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lansdorp-Vogelaar I, Kuntz KM, Knudsen AB, van Ballegooijen M, Zauber AG, Jemal A. Contribution of screening and survival differences to racial disparities in colorectal cancer rates. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2012;21(5):728–736. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-12-0023. https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-12-0023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Doubeni CA, Laiyemo AO, Klabunde CN, Young AC, Field TS, Fletcher RH. Racial and ethnic trends of colorectal cancer screening among Medicare enrollees. Am J Prev Med. 2010;38(2):184–191. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.10.037. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2009.10.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Laiyemo AO, Doubeni C, Pinsky PF, et al. Race and colorectal cancer disparities: health-care utilization vs different cancer susceptibilities. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2010;102(8):538–546. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djq068. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djq068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Siegel R, Desantis C, Jemal A. Colorectal cancer statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin. 2014;64(2):104–117. doi: 10.3322/caac.21220. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shapiro JA, Seeff LC, Thompson TD, Nadel MR, Klabunde CN, Vernon SW. Colorectal cancer test use from the 2005 National Health Interview Survey. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17(7):1623–1630. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-2838. https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-2838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jerant AF, Fenton JJ, Franks P. Determinants of racial/ethnic colorectal cancer screening disparities. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(12):1317–1324. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.12.1317. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.168.12.1317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Doubeni CA, Laiyemo AO, Young AC, et al. Primary care, economic barriers to health care, and use of colorectal cancer screening tests among Medicare enrollees over time. Ann Fam Med. 2010;8(4):299–307. doi: 10.1370/afm.1112. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.1112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liss DT, Baker DW. Understanding current racial/ethnic disparities in colorectal cancer screening in the United States: the contribution of socioeconomic status and access to care. Am J Prev Med. 2014;46(3):228–236. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2013.10.023. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2013.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gupta S, Sussman DA, Doubeni CA, et al. Challenges and possible solutions to colorectal cancer screening for the underserved. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2014;106(4):dju032. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dju032. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/dju032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rauscher GH, Hawley ST, Earp JA. Baseline predictors of initiation vs. maintenance of regular mammography use among rural women. Prev Med. 2005;40(6):822–830. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.09.029. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.09.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mehta SJJC, Quinn VP, Schottinger JE, et al. Race/Ethnicity and Adoption of a Population Health Management Approach to Colorectal Cancer Screening in a Community-Based Healthcare System. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(11):1323–1330. doi: 10.1007/s11606-016-3792-1. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-016-3792-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Burnett-Hartman AN, Mehta SJ, Zheng Y, et al. Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Colorectal Cancer Screening Across Healthcare Systems. Am J Prev Med. 2016;51(4):e107–115. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2016.02.025. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2016.02.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gordon NP. Internal Division of Research report. Oakland, CA: Kaiser Permanente Northern California Division of Research; 2012. Similarity of the Adult Kaiser Permanente Membership in Northern California to the Insured and General Population in Northern California: Statistics from the 2007 California Health Interview Survey. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Steenkamer BM, Drewes HW, Heijink R, Baan CA, Struijs JN. Defining Population Health Management: A Scoping Review of the Literature. Popul Health Manag. 2017;20(1):74–85. doi: 10.1089/pop.2015.0149. https://doi.org/10.1089/pop.2015.0149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.National Committee on Quality Assurance. NQF-Endorsed Measures Specifications. 2016 www.ncqa.org/LinkClick.aspx?fileticket=POLoMIAi3Mo%3d&tabid=59&mid=1604&forcedownload=true.

- 21.WHO. BMI Classification. 2016 May 16; http://apps.who.int/bmi/index.jsp?introPage=intro_3.html.

- 22.Fine JP, Gray RJ. A proportional hazards model for the subdistribution of a competing risk. J Am Stat Assoc. 1999;94(446):496–509. https://doi.org/10.1080/01621459.1999.10474144. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maxwell AE, Crespi CM. Trends in colorectal cancer screening utilization among ethnic groups in California: are we closing the gap? Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18(3):752–759. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0608. https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Public Use File Release 1. Los Angeles, CA: UCLA: Center for Health Policy Research; 2011. 2009 California Health Interview Survey. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fedewa SA, Sauer AG, Siegel RL, Smith RA, Torre LA, Jemal A. Temporal Trends in Colorectal Cancer Screening among Asian Americans. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2016;25(6):995–1000. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-15-1147. https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-15-1147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fedewa SA, Goodman M, Flanders WD, et al. Elimination of cost-sharing and receipt of screening for colorectal and breast cancer. Cancer. 2015;121(18):3272–3280. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29494. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.29494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.White A, Vernon SW, Franzini L, Du XL. Racial and ethnic disparities in colorectal cancer screening persisted despite expansion of Medicare’s screening reimbursement. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2011;20(5):811–817. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-0963. https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-0963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Walsh JM, Kaplan CP, Nguyen B, Gildengorin G, McPhee SJ, Perez-Stable EJ. Barriers to colorectal cancer screening in Latino and Vietnamese Americans. Compared with nonLatino white Americans. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19(2):156–166. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.30263.x. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.30263.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ahmed NU, Pelletier V, Winter K, Albatineh AN. Factors explaining racial/ethnic disparities in rates of physician recommendation for colorectal cancer screening. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(7):e91–99. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301034. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2012.301034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Peipins LA, Soman A, Berkowitz Z, White MC. The lack of paid sick leave as a barrier to cancer screening and medical care-seeking: results from the National Health Interview Survey. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:520. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-520. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-12-520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Labor Force Characteristics by Race and Ethnicity, 2014. Published 2014. www.bls.gov/opub/reports/race-and-ethnicity/archive/labor-force-characteristics-by-race-and-ethnicity-2014.pdf.

- 32.Stimpson JP, Pagan JA, Chen LW. Reducing racial and ethnic disparities in colorectal cancer screening is likely to require more than access to care. Health Aff (Millwood) 2012;31(12):2747–2754. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.1290. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2011.1290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jerant AF, Arellanes RE, Franks P. Factors associated with Hispanic/non-Hispanic white colorectal cancer screening disparities. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(8):1241–1245. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0666-1. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-008-0666-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Getrich CM, Sussman AL, Helitzer DL, et al. Expressions of machismo in colorectal cancer screening among New Mexico Hispanic subpopulations. Qual Health Res. 2012;22(4):546–559. doi: 10.1177/1049732311424509. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732311424509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Coronado GD, Farias A, Thompson B, Godina R, Oderkirk W. Attitudes and beliefs about colorectal cancer among Mexican Americans in communities along the U.S.-Mexico border. Ethn Dis. 2006;16(2):421–427. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fernandez ME, Wippold R, Torres-Vigil I, et al. Colorectal cancer screening among Latinos from U.S. cities along the Texas-Mexico border. Cancer Causes Control. 2008;19(2):195–206. doi: 10.1007/s10552-007-9085-6. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10552-007-9085-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.James AS, Campbell MK, Hudson MA. Perceived barriers and benefits to colon cancer screening among African Americans in North Carolina: how does perception relate to screening behavior? Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2002;11(6):529–534. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Freeman KL, Jandorf L, Thompson H, DuHamel KN. Colorectal Cancer Brochure Development for African Americans. J Health Dispar Res Pract. 2010;3(3):43–56. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cooperman JL, Efuni E, Villagra C, DuHamel K, Jandorf L. Colorectal cancer screening brochure for Latinos: focus group evaluation. J Cancer Educ. 2013;28(3):582–590. doi: 10.1007/s13187-013-0506-9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13187-013-0506-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Groeneveld PW, Sonnad SS, Lee AK, Asch DA, Shea JE. Racial differences in attitudes toward innovative medical technology. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(6):559–563. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00453.x. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00453.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wernli KJ, Hubbard RA, Johnson E, et al. Patterns of colorectal cancer screening uptake in newly eligible men and women. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2014;23(7):1230–1237. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-13-1360. https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-13-1360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. G. Kaiser Permanente: Evolution of Data Collection on Race, Ethnicity, and Language Preference Information. 2014 www.ahrq.gov/research/findings/final-reports/iomracereport/reldataapg.html.

- 43.Siegel RL, Fedewa SA, Miller KD, et al. Cancer statistics for Hispanics/Latinos, 2015. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65(6):457–480. doi: 10.3322/caac.21314. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gomez SL, Kelsey JL, Glaser SL, Lee MM, Sidney S. Inconsistencies between self-reported ethnicity and ethnicity recorded in a health maintenance organization. Ann Epidemiol. 2005;15(1):71–79. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2004.03.002. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annepidem.2004.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Diez-Roux AV, Kiefe CI, Jacobs DR, Jr, et al. Area characteristics and individual-level socioeconomic position indicators in three population-based epidemiologic studies. Ann Epidemiol. 2001;11(6):395–405. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(01)00221-6. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1047-2797(01)00221-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.