Abstract

High-throughput imaging (HTI) is a promising tool in the discovery of cellular disease mechanisms. While traditional approaches to identify disease pathways often rely on knowledge of the causative genetic defect, HTI-based screens offer an unbiased discovery approach based on any morphological or functional defects of disease cells or tissues. Here we provide an overview of the use of HTI for the study of human disease mechanisms. We discuss key technical aspects of HTI and highlight representative examples of its practical applications for the discovery of molecular mechanisms of disease, focusing on infectious diseases and host-pathogen interactions, cancer, and a rare genetic disease. We also present some of the current challenges and possible solutions offered by recent novel cell culture systems and genome engineering approaches.

Keywords: fluorescence microscopy, RNAi screening, chemical screening, high-throughput imaging, high-content imaging, automation, phenotypic profiling

Introduction

High-throughput imaging (HTI) refers to the use of automated microscopy and image analysis to visualize and quantitatively capture cellular features at a large scale. A typical HTI pipeline consists of automated liquid handling for reagent dispensing and staining, high-throughput microscopy for automated image acquisition, automated image analysis for cellular features extraction, and statistical data analysis (Fig. 1, Key Figure).

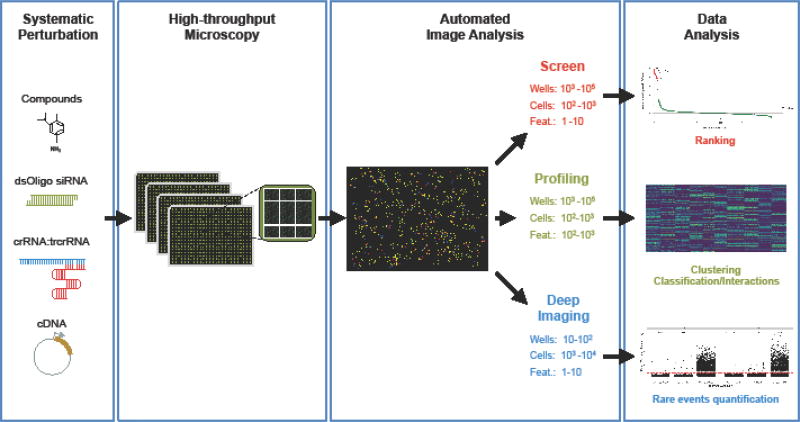

Fig. 1. Key Figure. Principles of High-Throughput Imaging (HTI).

HTI is a sequential workflow of automated operations. Cells are treated in a multi-well format with perturbing agents (small molecules, siRNA, CRISPR/Cas9 reagents (crRNA:trcrRNA), plasmid vectors) to systematically probe their effect on cellular phenotypes. Automated microscopes then acquire images of treated cells in multiple plates, and automated image analysis is used to extract multiparametric cellular features datasets from the images. In screening applications, a small number (1–10) of these features is used to measure the activity of a large number (103-105) of perturbations on one or few selected molecular pathways, and to rank treatments based on their biological effect in the HTI assay. In profiling assays, a large number (102–103) of cellular features are used to construct multiparametric phenotypic profiles that can be used in statistical learning approaches to cluster and classify a large number (103–105) of perturbations in functional groups, or to measure interactions between pairwise combinations of treatments. In deep imaging assays, automated microscopy and HCA is leveraged to generate datasets of few (10–102), selected cellular features for a large (103–104) number of cells per experimental condition to precisely quantify rare but biologically important cellular events. The upper leftmost panel was adapted from [85]. The lower leftmost panel was adapted from [38].

At the center of any HTI approach is a robust phenotypic assay such as the localization of a marker protein or a morphological cellular feature (Fig. 1, Key Figure). Fluorescent reagents, chemical dyes, genetically encoded fluorescent proteins, or fluorophore-conjugated antibodies and oligonucleotides, are typically used to specifically label cellular nucleic acids, proteins, compartments or organelles of interest. Systematic perturbations using small molecules, RNA interference (RNAi) or Clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR)/Cas9 are then applied with the goal of identifying and studying factors that control the cellular phenotypes monitored in the readout assay (Fig. 1, Key Figure) [1–3]. High-throughput fluorescence or bright-field microscopes are routinely used to acquire large numbers of images, in some applications up to 105 per day (Fig. 2A). Image datasets are processed using automated image analysis to quantitatively extract morphological features from images at the single cell level (Fig. 2B) [4]. These features may measure changes in the position, morphology, intensity or texture of the assay marker in response to the perturbing agents. The set of perturbing agents that induce a change in the cellular features that are being interrogated points to cellular pathways involved in establishment or maintenance of the phenotype of interest.

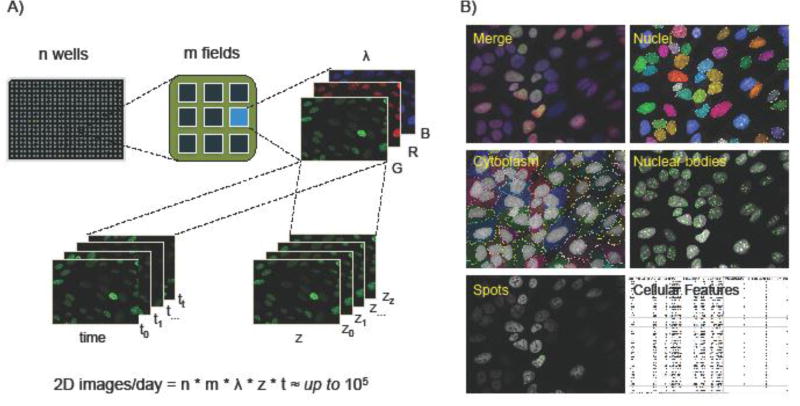

Fig. 2. A) Automated Microscopy.

Automated microscopes can be programmed to acquire images in all wells at randomly pre-selected positions (fields of view) in each well, in multiple spectral channels to visualize different fluorescent cellular markers in individual cells, in multiple z-planes, and, using integrated environmental chambers, at multiple time points to measure changes in the kinetic properties of molecular processes in live cells. Depending on the biological question addressed by the HTI assay and on its format (Screening, profiling, deep imaging), automated microscopy can generate large datasets of images (generally up to 105 per day) by selecting different combinations of the image acquisition dimensions mentioned above. B) Automated image analysis. Automated image analysis extracts numerical cellular features from multichannel fluorescence microscopy images. In a typical analysis workflow, nuclear segmentation is based on a fluorescent DNA stain to generate a nuclear region of interest (ROI). The nuclear ROI is then expanded and, with the addition of information from a cytoplasmic stain channel, a cytoplasmic ROI is generated. Other cellular compartments or features such as spots and nuclear bodies (or vesicles, neurites, and cellular processes; not shown) are segmented by HCA based on the presence of other appropriate fluorescent cellular markers to generate additional compartment-specific ROI’s. HCA can measure up to a 1000 different numerical cellular features in different classes (Counts, intensity, texture, morphology, topology, relational), which can then be used in downstream statistical analysis steps as a proxy to quantify biological processes (See Fig. 1, Key Figure).

The use of HTI has several advantages over conventional plate reader based discovery methods, such as luminescence or whole-well fluorescence. It permits testing of biological questions using large numbers of experimental treatments, in large cellular populations, and in an unbiased fashion. More importantly, HTI allows systematic probing of changes to cellular phenotypes rather than use of a single select cellular feature, and it offers extensive flexibility in use of a wide array of experimental systems and most cellular phenotypes observable with a traditional microscope can be used as assay readouts. Just as in traditional low throughput fluorescence microscopy applications, HTI preserves cellular integrity, provides spatial and kinetic information about biological processes, and can be multiplexed to study multiple phenotypes in the same experiment. Furthermore, HTI compounds these advantages with the generation of quantitative measurements on a large scale. HTI is highly versatile in its applications and can be adapted to various purposes by use of different classes of perturbing reagents, fluorescent markers, and downstream statistical analysis of the data, while maintaining the general structure of the HTI workflow of automated liquid handling, high-throughput microscopy and automated image analysis. For all these reasons, HTI has become one of the tools of choice to identify novel cellular pathways involved in a variety of human diseases, to dissect their molecular mechanisms, and to discover potential therapeutic treatments.

HTI modalities have been used to explore a wide range of biological problems. In this review, we focus on a selected set of paradigmatic and bona fide HTI assays, which exploit complex morphological cellular traits, as opposed to non-microscopy based high-throughput approaches. These phenotypic assays highlight the power of this technique to probe the molecular mechanisms of major representative disease groups, including infectious diseases, cancer and rare monogenic diseases.

High-Throughput Imaging Modalities

Broadly speaking, HTI approaches can be functionally grouped in three classes: screening, profiling and deep imaging (Fig. 1, Key Figure). The most traditional use of HTI is in screening (Fig 1, Key Figure). Chemical compounds were among the first perturbing reagents to be used in combination with HTI for screening purposes [5]. Since then, screening of large and chemically diverse collections of compounds through HTI for compound identification and validation has become one of the methods of choice in drug discovery [6]. In an operationally similar but conceptually different approach, referred to as chemical genetics screening, HTI is used to screen libraries of characterized chemical inhibitors with known biological targets, with the aim of identifying genes or pathways involved in the regulation of a cellular phenotype. Examples of this approach include screens to probe mechanisms of permissivity to bacterial infection [7] or the formation of cellular stress granules [8]. RNAi is the second major class of perturbing reagents that have been used in HTI screens [1,2]. Arrayed RNAi screens, performed in multi-well plates or on printed glass slides, have now been extensively applied to the study of a variety of cellular pathways such as mitosis [9–12], endocytosis [13,14], the DNA damage response [15–20], autophagy [21,22], mitophagy [23] and genomic positioning in the nucleus [24], among others. More recently, CRISPR/Cas9-based genome editing reagents have been used side-by-side with siRNA oligos as perturbing treatments in an HTI screen to identify factors regulating nuclear area in the HCT116 colon cancer cell line [25]. While in terms of consistency the screening results obtained in this study with CRISPR/Cas9 reagents were more robust than the ones obtained with siRNA oligos [25], adoption of CRISPR/Cas9 as a tool for arrayed screen is still in its infancy, and more work will be needed to extrapolate the results of this study to other cell types and HTI assays. A further possibility is the use of pooled CRISPR/Cas9 screens as a potential alternative to HTI screens [26,27]. In pooled screens a large single cell population is infected with libraries of lentiviral vectors expressing the CRISPR/Cas9 components and enrichment or depletion of target genes upon selective pressure is typically measured by next generation sequencing. Compared to arrayed HTI screens, pooled CRISPR/Cas9 screens allows using genome-wide libraries that include many targeting reagents per gene and do not necessitate the use of expensive microplates, transfection reagents, and automated liquid handling equipment [3]. However, pooled CRISPR/Cas9 screens are currently of limited use in HTI approaches as it is often experimentally difficult to identify the affected gene at the single cell level in a population. As a consequence, arrayed HTI screens are still the technique of choice when the assay readout is phenotypic in nature (i.e. when a microscope image is needed).

While screening approaches are generally limited to the measurement of one or few parameters, HTI profiling takes advantage of the ability to generate large multiparametric datasets of cellular features generated by HCA and statistical learning methods to classify and cluster treatments based on the similarities of the phenotypes they induce [28] (Fig. 1, Key Figure). HTI-based profiling is increasingly becoming a powerful approach to functionally annotate libraries of compounds [29–31]. For example, an unbiased multiplexed cytological assay termed Cell Painting [32,33], based on use of a combination of multiple fluorescent chemical dyes to label several cellular compartments including nucleus, nucleoli, Golgi and plasma membrane, F-actin, mitochondria and ER, uses HCA to extract about 1000 cellular features from stained cells to define phenotypic fingerprints that can then be used to functionally cluster libraries of compounds [30], siRNA [34] and cDNA overexpressed allelic variants [35], based on the phenotypic response they elicit.

Finally, in deep imaging approaches [36], advantage is taken of the large amount of single-cell data generated by HTI to deeply interrogate the effect of a select few experimental perturbations, typically on the order of 10 to 100, but in much larger large cellular populations (up to 5*105) than in a typical HTI approach to identify and study rare but important biological events (Fig. 1, Key Figure). This strategy enabled, for example, the study of biogenesis of rare chromosomal translocations in living cells, which only occur in 1:500 cells in the population [37–39]. The cells of interest were identified by randomly acquiring information for tens of thousands of cells per treatment and then selecting few cells of interest [37].

HTI Applications to Study Disease

Infectious Diseases

HTI is a key resource to study infectious diseases, particularly host-pathogen interactions using both RNAi and chemical genetics screens [40]. These experiments have revealed important cellular determinants of infection susceptibility and have suggested possible targets for host-directed antibacterial and antiviral therapies.

In a landmark application, HTI-based assays were used to measure the entry of Vesicular Stomatitis Virus (VSV) and Simian Virus 40 (SV40) into mammalian cells as a proxy to characterize the activity of clathrin-mediated (CME) and caveolae- or lipid raft-mediated endocytosis, respectively [13]. These assays were used to screen an siRNA library targeting the human kinome to identify cellular pathways involved in the regulation of these endocytosis pathways. The study revealed extensive, but surprisingly nuanced, involvement of kinases in the specific regulation of either VSV or SV40 infection. 35% of all kinases knocked-down had an effect on either virus, and 80% of these were specific for one of the two viruses, but not the other one [13]. Interestingly, to further cluster kinases into functional subgroups, the authors also used a battery of secondary HTI assays to measure specific cellular phenotypes at different stages of CME or clathrin- and caveolae-mediated endocytosis elicited by RNAi knockdowns. These experiments confirmed that most kinases have specific roles in regulation of either one of these pathways, but also revealed the existence of negative feedback coordination of their function and the extensive involvement of established signaling pathways in regulating endocytosis and viral entry. This study represented one of the first examples of the application of HTI to systematically probe cellular pathways involved in viral entry and subsequent HTI-based RNAi screens have identified cellular genes required for the replication of several viral families [41].

One of the strengths of HTI, which is particularly pertinent to the study of viral infections, is the generation of single cell data both for cellular and viral markers, enabling correlation of cellular state with viral infection rates and with modulation of host molecular pathways [42]. This cross-correlation approach enables a more precise quantitation of infection rates by correcting for indirect cellular heterogeneity, either pre-existing or RNAi induced, in the infected population data [43]. Furthermore, an RNAi screen combined with an HTI-based workflow to reconstruct temporal infection trajectories in fixed cells based on cellular and viral markers, revealed that rotavirus induces reorganization of membranes, inhibition of host protein translation, and alterations in the RNA processing machinery in an ordered fashion along the different stages of infection [44]. The identification in this approach of genes that stalled the rotavirus replication cycle at different points demonstrates that HCA can not only be used to identify host genes involved in viral replication, but also to gain insight into their specific mechanistic role at different stages of infection.

Another major focus of HTI in the study of infectious disease has been the analysis of intracellular bacterial pathogens. HTI based genome-wide RNAi screens in D. melanogaster cells revealed the existence of several cellular pathways necessary for intracellular infection by L. monocytogenes [45] or M. fortuitum [46]. The two screens revealed the existence of genes and cellular pathways that are pathogen-specific, such as the Tor kinase for L. monocytogenes and the dTip60 histone acetyltransferase for M. fortuitum, as well as others that are more generally required for intracellular pathogenesis including vesicular trafficking, Cdc42 signaling, and the Arp2/3 complex [45], suggesting the existence of cellular factors that could be potentially targeted pharmacologically by broad-spectrum anti-bacterial compounds. HTI was also used in a chemical genetics screen to isolate AKT1 as one of the human kinases necessary for intracellular growth of S. typhimurium and M. tubercolosis, and to identify AKT1 inhibitors as potential host-specific antibacterial drugs for these pathogens [7].

More recently, HTI was used not only to screen for chemical inhibitors of intracellular mycobacterial growth, but also to map their mechanism of action to known cellular pathways based on imaging-based profiling [47]. A collection of 2,000 bioactive compounds was screened in an HTI-assay to measure intracellular M. bovis growth in primary human macrophages. The assay leveraged multi-parametric HCA not only to identify active compounds, but also to cluster them in groups based on both bacterial intracellular phenotypes and host phenotypes. Based on these criteria, 115 active compounds were shown to inhibit M. bovis intracellular growth without causing host cytotoxicity phenotypes. Since mycobacterial intracellular growth heavily relies on the host endocytosis system, while at the same time hijacking it, possible effects of these compounds on these pathways were tested by phenotypic profiling, using an HTI assay previously optimized to profile genes based on their effect on endocytosis by RNAi screening [14]. By using this assay to match chemical and reverse genetics HTI fingerprints, it was possible to show that hit compounds found in the chemical screen fell into two separate clusters [47]. One cluster of compounds inhibited M. bovis intracellular growth by modulating autophagy, while the other acted by accelerating lysosomal trafficking. HCA was also used to further dissect the fine details of the molecular pathways affected by few selected compounds, including autophagy and endocytosis [47]. This multi-pronged approach is highly effective in that it increases the confidence in the molecular mechanism of the chemical hits, and allows generation of novel hypotheses on how to inhibit mycobacterial growth with other compounds modulating the same cellular pathways, but not present in the original library used in the screen.

Altogether, HTI has emerged as a powerful tool to study host-pathogen interactions for two reasons: it allows testing of thousands of experimental conditions to discover cellular factors promoting or preventing pathogen replication, while at the same time providing key molecular insights in the mechanisms and cellular pathways affected by viral or bacterial infection.

Cancer

HTI is a useful tool to discover novel genetic and chemical vulnerabilities of cancers through phenotypic screening. As an example, an imaging based RNAi screen for proliferation and differentiation of neuroblastoma (NB) cells identified, among other hits, the KMT5A (SETD8) lysine-methyltransferase enzyme as an essential factor for NB survival and maintenance of an undifferentiated state [48]. The HTI assay used in the screen measured the number of nuclei as a proxy for proliferation capacity of the NB cell line and total neurite length as a surrogate for morphologic differentiation. As a validation of the screening hit, RNAi knock-down of KMT5A expression reduced cellular proliferation, increased formation of neurites and induced apoptosis in NB cells via activation of a p53-dependent pathway. Independent confirmation of the hit came from the finding that UNC0379, a selective chemical inhibitor of KMT5A, phenocopied in HTI live-cell experiments the results obtained with RNAi knockdown, and led to a reduction of tumor growth in a xenograft mouse model of neuroblastoma [48].

In a similar approach to identify vulnerabilities of specific brain tumors, live-cell HTI was used to discover and study compounds to inhibit cell growth of Glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) [49]. GBM presents with both genetic and phenotypic intra- and inter-tumor heterogeneity in patients. This represents a considerable obstacle for traditional chemical screening and identification of effective and broad-spectrum treatments for GBM, because GBM cell lines do not fully capture this inherent heterogeneity, fail to recapitulate the disease phenotypes in cell culture, and as such are a suboptimal proxy for the disease [50]. To overcome this challenge, glioblastoma neuronal stem cell (GNS) lines obtained from 3 patients affected by different molecular GBM subtypes and, as a negative control, an embryonal neural stem cell (NS) line were screened in a live-cell HTI assay against a panel of 160 kinase inhibitors [49]. The use of multiple GNS lines containing different cell subtypes enabled identification of candidate molecules with wide spectrum activity against GBM. J101, a compound originally annotated as a PDGF Receptor Kinase inhibitor IV, was identified as a selective proliferation inhibitor for all three GNS cell lines, but not for the NS cell line, revealing a cancer-specific vulnerability in GBM. Based on the cellular phenotype it elicited, it was also possible to demonstrate that J101 induced cytostasis by inhibiting the mitotic kinase PLK1, and that other, more specific inhibitors of PLK1 were highly effective in blocking GNS proliferation in cell culture [49]. The results of this study demonstrate the potential of using cancer patient cell lines in combination with HTI phenotypic screening to tease out the effect of cellular heterogeneity on the response to chemical treatments during the screening phase, and to gain insights into the relevant mechanism of action while validating hit compounds.

These conclusions are strengthened by a recent chemical screen for the identification of compounds overcoming resistance to the drug venetoclax, an apoptosis enhancer, in a model of chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) [51]. Unstimulated CLL patient-derived cells are sensitive to venetoclax-mediated killing in cell culture, whereas stimulation via IL2 and Toll-like receptor (TLR7/8), a treatment mimicking the leukemic environment in patients, renders them insensitive to this drug in the same experimental conditions. An HTI assay using combinations of cellular features related to mitochondrial potential, apoptotic markers, and nuclear condensation was optimized to measure sensitization to venetoclax killing in IL2 and Toll-like receptor (TLR7/8) stimulated (2S) cells [51]. The assay was then used to screen a library of 320 kinase inhibitors against 2S cells from 13 patients in the presence of venetoclax to identify positive synergistic drug-drug interactions. Interestingly, the screen led to the identification of the FDA approved drug sunitinib as a potentiator of the effect of venetoclax in 8 out 13 of the 2S cell lines by the inhibition of the Bcl-xl/Mcl-1 anti-apoptotic axis. These observations further suggest that, in order to identify effective broad-spectrum chemical treatments for cancer, it is advisable to devise HTI cellular assays closely modeling specific cellular environments of tumors, and capable of capturing the often observed patient-to-patient heterogeneity in the response to anti-cancer treatments.

Chemical screening for anti-cancer compounds is not the only application of HTI to study the molecular mechanisms of cancer. In fact, cellular profiling by HTI has also been used to systematically identify interactions between cellular pathways and functionally annotated chemical compounds in cancer cells on a large scale [52]. In a prominent application of this approach, isogenic HCT116 colon cancer cell lines were genetically engineered to either remove a mutated proto-oncogene allele and keep only its wild-type counterpart (CTNNB1, KRAS, and PI3KCA), or to knock-out genes belonging to signaling pathways involved in cancer (PTEN, AKT1, AKT1 and AKT2, MAP2K1, MEK1, MAP2K2, MEK2, TP53, and BAX). This panel of 12 isogenic cells lines and 2 HCT116 parental cell lines were challenged with a library of 1,280 pharmacologically active compounds. HCA was used to extract a set of 20 relevant cellular features related to cell number, nuclear shape, nuclear texture, and actin network morphology to create a genotype-specific phenotypic signature in the untreated state. Alterations of these morphological fingerprints induced by compound treatments were then used to study interactions between specific compounds and different genetic backgrounds. The analysis of these interaction networks led to three main conclusions: They confirmed crosstalk between different oncogenic signaling pathways (e.g. KRAS and PI3K), and led to the discovery of novel synthetic lethal interactions between some of these pathways (e.g. DNA alkylation and AKT signaling), which could potentially be chemically targeted for more effective anti-cancer combination therapies. Furthermore, the authors observed that profiling compounds with multiparametric HCA phenotypic analysis in different genetic backgrounds improved the performance, over either approach alone, in clustering chemically similar compounds into the same functional group, such as in the case of the glucocorticosteroids betamethasone and beclomethasone. Finally, the approach revealed the existence of non-specific polypharmacological effects of previously annotated compounds including proteasome inhibition by the EGFR inhibitor tryphostin AG555, and by the ALDH inhibitor disulfiram. Overall, this study demonstrates that HTI can be used to precisely profile large collections of experimental perturbations to dissect gene function in normal and cancer cells and to identify potential cancer-specific genetic weaknesses that can be potentially exploited by combination pharmacological approaches [53].

Monogenic Diseases

The rate at which disease-causing mutations are identified is rapidly accelerating due to the increased throughput of DNA sequencing methods. However, despite the identification of these mutations, the molecular pathways driving the disease phenotype can often not be identified based on genetic information alone. To overcome this limitation, HTI assays that take advantage of cellular models recapitulating monogenic disease phenotypes are powerful tools in combination with screening libraries of siRNAs or compounds to identify cellular pathways involved in the molecular etiology of disease. The premature aging disorder Hutchinson-Gilford Progeria Syndrome (HGPS) is a well-characterized paradigmatic example of how application of HTI can help in the elucidation of driver pathways of a monogenic disease.

HGPS is caused by a single de novo mutation in the LMNA gene, which leads to the production of Progerin, a dominant negative version of lamin A, a key structural component of the nuclear envelope [54,55]. Progerin expression in HGPS patient primary fibroblasts acts in a dominant fashion to cause a wide spectrum of reversible nuclear defects, including down-regulation of other components of the nuclear envelope, such as lamin B1, and upregulation of the DNA damage response, as measured by an increase of histone ɣ-H2AX phosphorylation [56]. The identity of cellular pathways that give rise to these phenotypes in HGPS cells downstream of progerin are only partially known. To identify and study these pathways, an inducible fibroblast cell line expressing progerin and capable of recapitulating the multiple HGPS cellular phenotypes was generated [57]. This cell line was used in an HTI chemical screen of a library of FDA-approved compounds to identify small molecules that prevent the formation of multiple HGPS phenotypes. Importantly, the concomitant inclusion of multiple phenotypic HGPS markers allowed simultaneous probing of different molecular pathways involved in the disease and increased the stringency of the screen, resulting in a highly selective hit-rate below 1% [57]. The screen led to the identification, among other hits, of agonists of retinoid acid receptors (RXR) as suppressors of the progerin-induced phenotypes in HGPS patient cells [57]. This conclusion was confirmed by the independent identification of retinoids as suppressors of HGPS cellular phenotypes in a chemical screen using an assay based on iPS-derived HGPS mesenchymal stem cells (MSC) [58]. The effect of retinoids is mostly liked due to the presence of a retinoic acid response element in the promoter of the LMNA gene, resulting in repression of progerin expression in the presence of retinoids [59]. HGPS MSC cells were also used in an HTI-based drug screen for the discovery of novel farnesyl transferase inhibitors (FTI) [60], the first class of compounds under clinical trial evaluation for HGPS [61]. A high-throughput antibody-based assay using these cells identified a validated set of 11 active compounds, including 6 containing one or more aminopyrimidine (AP) groups, in a screen of 21,608 small molecules [60]. Using the previously reported premature osteogenic differentiation of HGPS cells as an assay [58], and an HTI assay measuring nuclear morphological defects in HGPS MSC cells, mono-aminopyrimidines (Mono-AP’s) acted as particularly potent suppressors of HGPS phenotypes, possibly by directly binding and inhibiting farnesyltransferase (FT) and farnesyl pyrophosphate synthase (FFPS), two enzymes involved in prelamin A farnesylation.

In a modification of these approaches, an HTI HGPS phenotype assay was also successfully used in a targeted RNAi screen of 320 E1, E2 and E3 ubiquitin ligases to identify cellular genes and pathways that modulate, and possibly suppress, HGPS phenotypes in vitro and in vivo [62]. Three of the top validated HGPS phenotype modulators discovered by the RNAi knockdown were CAND1, RBX1 and CUL3, which together with KEAP1 encode for an E3 ubiquitin ligase complex that targets NRF2, a key transcription factor activating a protective antioxidant cellular response and previously implicated in aging, for proteolytic destruction by the proteasome [63]. HTI-based assays were further used to analyze the molecular links between progerin and NRF2. The results of these experiments showed that progerin impairs NRF2 transcriptional activation function in HGPS patient cells, leading to a stunted antioxidant response and high-levels of oxidative damage. Thus, HTI led to the identification and characterization of the NRF2 pathway as a molecular driver pathway in HGPS etiology, and as a potential therapeutic target for the amelioration of HGPS symptoms [62].

Another example for the application of HTI to identify small molecules capable of reverting pathological phenotypes in a cellular model of monogenic disease, is cerebral cavernous malformation (CCM), which is often caused by mutations in the CCM2 gene [64]. Using a modified Cell Painting approach, an assay based on a multiparametric fingerprint of cellular features capable of distinguishing cells that exhibit the CCM phenotype from control cells was optimized and used to screen a library of 2, 200 known drugs and biologically active compounds to identify small molecules that reverted the CCM phenotype. A machine learning-based model used to generate the HTI phenotypic fingerprint lead to the identification of 38 compounds in the primary screen, and, as demonstrated by downstream validation experiments, outperformed a qualitative visual assessment of the same images. Furthermore, 2 of these primary hits, tempol and colechalciferol, were active in subsequent in vivo assays using a mouse models of CCM [64].

These examples serve as a proof-of-principle for the use of HTI to screen large collections of reagents for the identification of genes or compounds regulating complex cellular pathological phenotypes of monogenic diseases. In addition, they also indicate that HTI-based profiling can be used to define fingerprints for previously unknown cellular phenotypes associated with specific monogenic diseases, and that these profiles can be then used to discover novel compounds reverting these pathological phenotypes.

Concluding Remarks: Challenges and Future Directions

HTI approaches are powerful discovery tools for the elucidation of disease mechanisms. One of the limitations of current HTI applications is the predominant use of cancer cell lines due to the complex logistics associated with large-scale screens, including the requirement for relatively large cell numbers. One obvious drawback of these simple, homogeneous cellular systems is their inability to capture the rich crosstalk between specialized cell types in tissues and organs, and the genetic diversity from patient to patient. In addition, cancer cell lines are often karyotypically unstable and their expansion as homogenous 2D monolayers on plastic does not reflect physiological cellular growth conditions. For these reasons, concerted efforts are now made to move away from the use of cancer cell lines to better mimic the physiological environment, diseases context, and responses to pharmacological treatments [65].

The use of patient-derived iPS or stem cells is a first step in developing physiologically more relevant screening systems [66]. iPS cells can be obtained from reprogramming of patient cells, are genomically stable, can be propagated indefinitely, and can be differentiated in a variety of cell lineages to model disease in relevant cell types. In addition to the previously mentioned HGPS-iPS cells [58,60], iPS cells obtained from patients affected by sporadic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (sALS) were differentiated into motor neurons and used in an endpoint assay to screen 1,757 bioactive compounds by measuring aggregation of the RNA binding protein TDP-43 in the nucleus via HTI [67]. A similar approach using embryonic stem cells (ESC) derived motor neurons and microglia was used to screen for compounds protecting from neurodegeneration associated with microglial activation [68], or X-linked Fragile Mental Retardation (FMR) patient-derived reprogrammed iPS cells to identify small molecules relieving the epigenetic silencing of the FMRP protein [69].

The capacity to model monogenic diseases using iPS cells will be greatly expanded by genome editing with RNA-guided nucleases such as the CRISPR/Cas9 system, which allows the specific introduction of pathogenic mutations in wild-type iPS cells [70], or their correction in patient-derived iPS cells [71,72]. This approach will provide matched isogenic controls for HTI screening purposes, thus isolating the contribution of specific pathogenic mutations from confounding effects due to heterogeneity in genetic backgrounds of iPS cell donors. Furthermore, CRISPR/Cas9 will also be instrumental to label endogenous proteins with genetically encoded fluorescent tags in iPS cells [73], potentially on a large scale [74,75], with the goal of generating novel HTI-based assays to be used in chemical or RNAi screens.

Another major step forward in the use of more physiological cellular assays in HTI will be the adoption of 3D organoid cell culture systems. Organoids are self-organizing cellular structures mimicking the cellular composition and 3D tissue architecture of an intact organ, and can be obtained from mouse and human tissue biopsies or iPS cells [76]. For example, intestinal epithelial organoids can be propagated in vitro and maintained in culture indefinitely under conditions that mimic the extracellular matrix and the stem cell niche environment [77–79]. Recent studies indicate that intestinal epithelial organoids can be isolated from groups of patients and banked to provide collections of organoid cell lines for genomic analysis and for drug screening [80,81]. Importantly for HTI applications, organoids can be imaged in 3D at low to medium-throughput [81]. Furthermore, they can be genetically engineered in a serial fashion with CRISPR/Cas9 to knock-out tumor suppressor genes, or introduce oncogenic mutations, to partially recapitulate colorectal cancer development in a dish [81–83]. While challenges remain to make intestinal epithelial organoids a feasible and reproducible experimental system for HTI screens [84], it will be interesting to see this model system applied in conjunction with HTI to study stem cell biology, colorectal cancer and other intestinal diseases.

Taken together, the past decade has seen dramatic growth of HTI applications in probing cellular pathways involved in disease with RNAi screens and in identifying new therapeutic small molecules by chemical screening. Moving forward (see Outstanding Questions), the combination of HTI with more physiological cell culture systems, such as stem cells, iPS cells and organoids, and robust genome editing technologies will expand the addressable range of disease-related biological questions and will be a rich new source of insights into the molecular mechanisms of disease.

Supplementary Material

Trends Box.

HTI is a powerful method in basic research, drug development and discovery of disease mechanisms.

HTI uses automated microcopy and image analysis to extract numerical cellular features that can be used to measure cellular pathways activity and/or morphological phenotypes.

HTI assays can be used to screen and profile large collections of perturbing reagents (Compounds, RNAi, CRISPR/Cas9), or to precisely quantify rare biological events.

Since HTI assays can be adapted to study a wide variety of cellular phenotypes, this technique has been adopted to identify cellular pathways and genes altered in pathogen infection, cancer and monogenic diseases, among others.

HTI has utility in chemical screens to discover novel cancer vulnerabilities for potential pharmacological intervention.

Outstanding Questions.

Will the use of CRISPR/Cas9 reagents become a complement or a substitute of RNAi in arrayed HTI screens? Will activation/inhibition CRISPR/Cas9 (CRISPRa/CRISPRi) assays become a routine element in the HTI reverse genetic screening toolset?

Will it be possible to use CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing approaches to efficiently generate large panels of known disease-associated allelic variants in a wild-type iPS cells background to screen with HTI for genotype-phenotype associations, and to then identify compounds that can revert these diseased cellular phenotypes?

Will 3D organoids become routinely used in HTI approaches to screen more complex phenotypes that better recapitulate disease in cell culture? To optically section these thick biological samples in 3D in a rapid manner, will fast 3D fluorescence microscopy techniques, such as light sheet fluorescence microscopy, become available in a multi-well, high-throughput format?

How will recent advances in statistical learning algorithms, including deep learning, for image and object classifications, to systematically discover previously unknown disease-associated cellular phenotypes influence future HTI approaches?

Acknowledgments

The NCI High-Throughput Imaging Facility (HiTIF) and the Misteli lab are supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), National Cancer Institute, the Center for Cancer Research. We would like to thank Prabhakar Gudla (HiTIF) for assistance with Fig. 1, Key Figure.

Glossary

- High-Throughput Imaging (HTI)

a technique combining automated liquid handling, high-throughput microscopy, and automated image analysis in a single workflow.

- High-Content Screening

An HTI approach which uses quantitation of large datasets of multiparametric morphological features as a readout.

- Automated liquid handling

a set of experimental steps to simultaneously move large numbers of liquid samples from one or more source vessels, usually multi-well plates, to destination vessels using programmable, multichannel robotic dispensing devices.

- Automated image analysis

unattended image processing workflow aimed at the identification of cellular and subcellular objects from a microscopy image, and at the extraction of cellular features that can be used to quantify or classify these objects.

- Imaging-based profiling

A workflow which uses HTI to identify hits in a small molecule, RNAi or CRISPR-screening.

- RNA interference (RNAi)

double-stranded RNA based method to silence the expression of a gene via the sequence-specific targeting of its mRNA for degradation.

- Clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic rpeats (CRISPR)/Cas9

method based on Cas9, a programmable bacterial RNA binding nuclease that can be targeted to bind specific regions in the genome. CRISPR/Cas9 can be used to knock-out genes and non-coding DNA regions via DNA double-strand breaks generation, edit genomic regions via DNA homologous recombination or deamination, or to target chromatin modifiers to change the epigenetic environment in a DNA sequence specific fashion.

- Kinome

the complete set of genes encoding kinases in a genome.

- Cytostasis

suppression of cell growth.

- Isogenic

cell lines or organisms sharing the same genetic background.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Conrad C, Gerlich DW. Automated microscopy for high-content RNAi screening. J. Cell Biol. 2010;188:453–461. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200910105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boutros M, et al. Microscopy-Based High-Content Screening. Cell. 2015;163:1314–1325. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wade M. High-Throughput Silencing Using the CRISPR-Cas9 System: A Review of the Benefits and Challenges. J. Biomol. Screen. 2015;20:1027–1039. doi: 10.1177/1087057115587916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ljosa V, Carpenter AE. Introduction to the quantitative analysis of two-dimensional fluorescence microscopy images for cell-based screening. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2009;5:e1000603. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Haggarty SJ, et al. Dissecting cellular processes using small molecules: identification of colchicine-like, taxol-like and other small molecules that perturb mitosis. Chem. Biol. 2000;7:275–286. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(00)00101-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bickle M. The beautiful cell: high-content screening in drug discovery. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2010;398:219–226. doi: 10.1007/s00216-010-3788-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kuijl C, et al. Intracellular bacterial growth is controlled by a kinase network around PKB/AKT1. Nature. 2007;450:725–730. doi: 10.1038/nature06345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wippich F, et al. Dual specificity kinase DYRK3 couples stress granule condensation/dissolution to mTORC1 signaling. Cell. 2013;152:791–805. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.01.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Neumann B, et al. High-throughput RNAi screening by time-lapse imaging of live human cells. Nat. Methods. 2006;3:385–390. doi: 10.1038/nmeth876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Neumann B, et al. Phenotypic profiling of the human genome by time-lapse microscopy reveals cell division genes. Nature. 2010;464:721–727. doi: 10.1038/nature08869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schmitz MHA, et al. Live-cell imaging RNAi screen identifies PP2A–B55alpha and importin-beta1 as key mitotic exit regulators in human cells. Nat. Cell Biol. 2010;12:886–893. doi: 10.1038/ncb2092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cuylen S, et al. Ki-67 acts as a biological surfactant to disperse mitotic chromosomes. Nature. 2016;535:308–312. doi: 10.1038/nature18610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pelkmans L, et al. Genome-wide analysis of human kinases in clathrin- and caveolae/raft-mediated endocytosis. Nature. 2005;436:78–86. doi: 10.1038/nature03571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Collinet C, et al. Systems survey of endocytosis by multiparametric image analysis. Nature. 2010;464:243–249. doi: 10.1038/nature08779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Doil C, et al. RNF168 binds and amplifies ubiquitin conjugates on damaged chromosomes to allow accumulation of repair proteins. Cell. 2009;136:435–446. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.12.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Paulsen RD, et al. A genome-wide siRNA screen reveals diverse cellular processes and pathways that mediate genome stability. Mol. Cell. 2009;35:228–239. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.06.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smogorzewska A, et al. A genetic screen identifies FAN1, a Fanconi anemia-associated nuclease necessary for DNA interstrand crosslink repair. Mol. Cell. 2010;39:36–47. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.06.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.O’Connell BC, et al. A genome-wide camptothecin sensitivity screen identifies a mammalian MMS22L–NFKBIL2 complex required for genomic stability. Mol. Cell. 2010;40:645–657. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.10.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fuchs F, et al. Clustering phenotype populations by genome-wide RNAi and multiparametric imaging. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2010;6:370. doi: 10.1038/msb.2010.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Adamson B, et al. A genome-wide homologous recombination screen identifies the RNA-binding protein RBMX as a component of the DNA-damage response. Nat. Cell Biol. 2012;14:318–328. doi: 10.1038/ncb2426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Orvedahl A, et al. Image-based genome-wide siRNA screen identifies selective autophagy factors. Nature. 2011;480:113–117. doi: 10.1038/nature10546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McKnight NC, et al. Genome-wide siRNA screen reveals amino acid starvation-induced autophagy requires SCOC and WAC. EMBO J. 2012;31:1931–1946. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2012.36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hasson SA, et al. High-content genome-wide RNAi screens identify regulators of parkin upstream of mitophagy. Nature. 2013;504:291–295. doi: 10.1038/nature12748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shachar S, et al. Identification of Gene Positioning Factors Using High-Throughput Imaging Mapping. Cell. 2015;162:911–923. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.07.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tan J, Martin SE. Validation of Synthetic CRISPR Reagents as a Tool for Arrayed Functional Genomic Screening. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0168968. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0168968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shalem O, et al. Genome-scale CRISPR-Cas9 knockout screening in human cells. Science. 2014;343:84–87. doi: 10.1126/science.1247005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang T, et al. Genetic screens in human cells using the CRISPR-Cas9 system. Science. 2014;343:80–84. doi: 10.1126/science.1246981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Caicedo JC, et al. Applications in image-based profiling of perturbations. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2016;39:134–142. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2016.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Perlman ZE, et al. Multidimensional drug profiling by automated microscopy. Science. 2004;306:1194–1198. doi: 10.1126/science.1100709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wawer MJ, et al. Toward performance-diverse small-molecule libraries for cell-based phenotypic screening using multiplexed high-dimensional profiling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2014;111:10911–10916. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1410933111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Reisen F, et al. Linking phenotypes and modes of action through high-content screen fingerprints. Assay Drug Dev. Technol. 2015;13:415–427. doi: 10.1089/adt.2015.656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gustafsdottir SM, et al. Multiplex cytological profiling assay to measure diverse cellular states. PLoS One. 2013;8:e80999. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0080999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bray M-A, et al. Cell Painting, a high-content image-based assay for morphological profiling using multiplexed fluorescent dyes. Nat. Protoc. 2016;11:1757–1774. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2016.105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Singh S, et al. Morphological Profiles of RNAi-Induced Gene Knockdown Are Highly Reproducible but Dominated by Seed Effects. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0131370. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0131370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rohban MH, et al. Systematic morphological profiling of human gene and allele function via Cell Painting. Elife. 2017:6. doi: 10.7554/eLife.24060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Roukos V, Misteli T. Deep Imaging: the next frontier in microscopy. Histochem. Cell Biol. 2014;142:125–131. doi: 10.1007/s00418-014-1239-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Roukos V, et al. Spatial dynamics of chromosome translocations in living cells. Science. 2013;341:660–664. doi: 10.1126/science.1237150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Burman B, et al. Quantitative detection of rare interphase chromosome breaks and translocations by high-throughput imaging. Genome Biol. 2015;16:146. doi: 10.1186/s13059-015-0718-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Burman B, et al. Histone modifications predispose genome regions to breakage and translocation. Genes Dev. 2015;29:1393–1402. doi: 10.1101/gad.262170.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brodin P, Christophe T. High-content screening in infectious diseases. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2011;15:534–539. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2011.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ramage H, Cherry S. Virus-Host Interactions: From Unbiased Genetic Screens to Function. Annu Rev Virol. 2015;2:497–524. doi: 10.1146/annurev-virology-100114-055238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Snijder B, et al. Population context determines cell-to-cell variability in endocytosis and virus infection. Nature. 2009;461:520–523. doi: 10.1038/nature08282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Snijder B, et al. Single-cell analysis of population context advances RNAi screening at multiple levels. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2012;8:579. doi: 10.1038/msb.2012.9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Green VA, Pelkmans L. A Systems Survey of Progressive Host-Cell Reorganization during Rotavirus Infection. Cell Host Microbe. 2016;20:107–120. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2016.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Agaisse H, et al. Genome-wide RNAi screen for host factors required for intracellular bacterial infection. Science. 2005;309:1248–1251. doi: 10.1126/science.1116008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Philips JA, et al. Drosophila RNAi Screen Reveals CD36 Family Member Required for Mycobacterial Infection. Science. 2005;309:1251–1253. doi: 10.1126/science.1116006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sundaramurthy V, et al. Integration of chemical and RNAi multiparametric profiles identifies triggers of intracellular mycobacterial killing. Cell Host Microbe. 2013;13:129–142. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2013.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Veschi V, et al. Epigenetic siRNA and Chemical Screens Identify SETD8 Inhibition as a Therapeutic Strategy for p53 Activation in High-Risk Neuroblastoma. Cancer Cell. 2017;31:50–63. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2016.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Danovi D, et al. A high-content small molecule screen identifies sensitivity of glioblastoma stem cells to inhibition of polo-like kinase 1. PLoS One. 2013;8:e77053. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0077053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pollard SM, et al. Glioma stem cell lines expanded in adherent culture have tumor-specific phenotypes and are suitable for chemical and genetic screens. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;4:568–580. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Oppermann S, et al. High-content screening identifies kinase inhibitors that overcome venetoclax resistance in activated CLL cells. Blood. 2016;128:934–947. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-12-687814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Breinig M, et al. A chemical-genetic interaction map of small molecules using high-throughput imaging in cancer cells. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2015;11:846. doi: 10.15252/msb.20156400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Luo J, et al. Principles of cancer therapy: oncogene and non-oncogene addiction. Cell. 2009;136:823–837. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.02.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Eriksson M, et al. Recurrent de novo point mutations in lamin A cause Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome. Nature. 2003;423:293–298. doi: 10.1038/nature01629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.De Sandre-Giovannoli A, et al. Lamin a truncation in Hutchinson-Gilford progeria. Science. 2003;300:2055. doi: 10.1126/science.1084125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Scaffidi P, Misteli T. Reversal of the cellular phenotype in the premature aging disease Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome. Nat. Med. 2005;11:440–445. doi: 10.1038/nm1204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kubben N, et al. A high-content imaging-based screening pipeline for the systematic identification of anti-progeroid compounds. Methods. 2016;96:46–58. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2015.08.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lo Cicero A, et al. A High Throughput Phenotypic Screening reveals compounds that counteract premature osteogenic differentiation of HGPS iPS-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:34798. doi: 10.1038/srep34798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Swift J, et al. Nuclear lamin-A scales with tissue stiffness and enhances matrix-directed differentiation. Science. 2013;341:1240104. doi: 10.1126/science.1240104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Blondel S, et al. Drug screening on Hutchinson Gilford progeria pluripotent stem cells reveals aminopyrimidines as new modulators of farnesylation. Cell Death Dis. 2016;7:e2105. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2015.374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gordon LB, et al. Clinical trial of a farnesyltransferase inhibitor in children with Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2012;109:16666–16671. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1202529109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kubben N, et al. Repression of the Antioxidant NRF2 Pathway in Premature Aging. Cell. 2016;165:1361–1374. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lo S-C, Hannink M. CAND1-mediated substrate adaptor recycling is required for efficient repression of Nrf2 by Keap1. Mol Cell. Biol. 2006;26:1235–1244. doi: 10.1128/MCB.26.4.1235-1244.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gibson CC, et al. Strategy for identifying repurposed drugs for the treatment of cerebral cavernous malformation. Circulation. 2015;131:289–299. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.010403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Horvath P, et al. Screening out irrelevant cell-based models of disease. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2016;15:751–769. doi: 10.1038/nrd.2016.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Avior Y, et al. Pluripotent stem cells in disease modelling and drug discovery. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2016;17:170–182. doi: 10.1038/nrm.2015.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Burkhardt MF, et al. A cellular model for sporadic ALS using patient-derived induced pluripotent stem cells. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 2013;56:355–364. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2013.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Höing S, et al. Discovery of inhibitors of microglial neurotoxicity acting through multiple mechanisms using a stem-cell-based phenotypic assay. Cell Stem Cell. 2012;11:620–632. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kaufmann M, et al. High-Throughput Screening Using iPSC-Derived Neuronal Progenitors to Identify Compounds Counteracting Epigenetic Gene Silencing in Fragile X Syndrome. J. Biomol Screen. 2015;20:1101–1111. doi: 10.1177/1087057115588287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Paquet D, et al. Efficient introduction of specific homozygous and heterozygous mutations using CRISPR/Cas9. Nature. 2016;533:125–129. doi: 10.1038/nature17664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Xie F, et al. Seamless gene correction of β-thalassemia mutations in patient-specific iPSCs using CRISPR/Cas9 and piggyBac. Genome Res. 2014;24:1526–1533. doi: 10.1101/gr.173427.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Li HL, et al. Precise correction of the dystrophin gene in duchenne muscular dystrophy patient induced pluripotent stem cells by TALEN and CRISPR-Cas9. Stem Cell Reports. 2015;4:143–154. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2014.10.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Roberts B, et al. Systematic gene tagging using CRISPR/Cas9 in human stem cells to illuminate cell organization. bioRxiv at. 2017 doi: 10.1091/mbc.E17-03-0209. < http://biorxiv.org/content/early/2017/03/31/123042.abstract>. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 74.Kamiyama D, et al. Versatile protein tagging in cells with split fluorescent protein. Nat. Commun. 2016;7:11046. doi: 10.1038/ncomms11046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Leonetti MD, et al. A scalable strategy for high-throughput GFP tagging of endogenous human proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2016;113:E3501–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1606731113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Fatehullah A, et al. Organoids as an in vitro model of human development and disease. Nat. Cell Biol. 2016;18:246–254. doi: 10.1038/ncb3312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Sato T, et al. Single Lgr5 stem cells build crypt-villus structures in vitro without a mesenchymal niche. Nature. 2009;459:262–265. doi: 10.1038/nature07935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Jung P, et al. Isolation and in vitro expansion of human colonic stem cells. Nat. Med. 2011;17:1225–1227. doi: 10.1038/nm.2470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Sato T, et al. Long-term expansion of epithelial organoids from human colon, adenoma, adenocarcinoma, and Barrett’s epithelium. Gastroenterology. 2011;141:1762–1772. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.07.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.van de Wetering M, et al. Prospective derivation of a living organoid biobank of colorectal cancer patients. Cell. 2015;161:933–945. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.03.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Verissimo CS, et al. Targeting mutant RAS in patient-derived colorectal cancer organoids by combinatorial drug screening. Elife. 2016:5. doi: 10.7554/eLife.18489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Drost J, et al. Sequential cancer mutations in cultured human intestinal stem cells. Nature. 2015;521:43–47. doi: 10.1038/nature14415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Matano M, et al. Modeling colorectal cancer using CRISPR-Cas9-mediated engineering of human intestinal organoids. Nat. Med. 2015;21:256–262. doi: 10.1038/nm.3802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Ranga A, et al. Drug discovery through stem cell-based organoid models. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2014;69–70:19–28. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2014.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Pegoraro G, et al. Identification of mammalian protein quality control factors by high-throughput cellular imaging. PLoS One. 2012;7:e31684. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0031684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.