Abstract

C3 exoenzymes (members of the ADP-ribosyltranferase family) are produced by Clostridium botulinum (C3bot1 and -2), Clostridium limosum (C3lim), Bacillus cereus (C3cer), and Staphylococcus aureus (C3stau1–3). These exoenzymes lack a translocation domain but are known to specifically inactivate Rho GTPases in host target cells. Here, we report the crystal structure of C3bot1 in complex with RalA (a GTPase of the Ras subfamily) and GDP at a resolution of 2.66 Å. RalA is not ADP-ribosylated by C3 exoenzymes but inhibits ADP-ribosylation of RhoA by C3bot1, C3lim, and C3cer to different extents. The structure provides an insight into the molecular interactions between C3bot1 and RalA involving the catalytic ADP-ribosylating turn–turn (ARTT) loop from C3bot1 and helix α4 and strand β6 (which are not part of the GDP-binding pocket) from RalA. The structure also suggests a molecular explanation for the different levels of C3-exoenzyme inhibition by RalA and why RhoA does not bind C3bot1 in this manner.

Keywords: ADP-ribosylation, protein–protein interaction, x-ray crystallography

Bacteria produce many enzymes that show extraordinary specificity for mammalian intracellular proteins. The specificity of these bacterial enzymes has not only made them a valuable tool for elucidating the cellular functions of their targets but has also increased our understanding of protein interactions. Clostridium botulinum is no exception, producing two classes of enzymes that have very specific protein targets, the neurotoxins A–G and the ADP-ribosyltransferases C2, C3bot1, and C3bot2. C2 and C3bot are part of a larger family of ADP-ribosylating toxins (1, 2), including diphtheria toxin and cholera toxin, which cleave NAD and transfer ADP-ribose to target proteins. Although the members of this family have homologous enzymatic domains and similar active sites, these toxins ADP-ribosylate and, therefore, disable a range of cellular targets.

C3bot1 (3, 4) is the prototype of the subgroup of C3 ADP-ribosyltransferases that are distinctive in their lack of cell-binding or translocation domains (5). Although C3bot1 is expressed alongside the neurotoxins in C. botulinum, the role of C3bot1 in pathogenesis is unclear because it lacks a translocation domain and has no obvious method of gaining entry into mammalian cells. However, the discovery of the specificity of C3bot1 for the Ras-related Rho GTPases A–C (6–8) has resulted in the long-term use of C3bot1 as a molecular tool for the study of Rho proteins in mammalian cells (9). The other members of the C3 family include C3lim (from Clostridium limosum), C3cer (from Bacillus cereus), and C3stau1–3 (from Staphylococcus aureus) and are also known as epidermal differentiating inhibitors (EDINs) A–C (5). Of these EDINs, only C3stau1 and -2 have been shown to have a different target specificity from that of C3bot1, ribosylating the homologous RhoE and Rnd3 proteins in addition to RhoA–C (10). Rho GTPases regulate many signaling pathways through control of the cytoskeleton and transcription, including cell-cycle progression, chemotaxis, cell transformation, and apoptosis (11). These functions of Rho are sufficient to explain the distinctive morphological changes observed after the addition of C3bot1 to the cytosol of cells. These changes are specific to cell type, and the observation that neuronal PC12 cells exhibit neural outgrowth (12) and experiments showing that C3bot1 can cause regeneration of injured axons in vivo (13) suggested a possible usefulness in treating neuronal disorders (14).

The recent discovery of the ability of RalA, another Ras-related GTPase, to bind C3bot1 (15) led to a new question of C3 specificity. RalA and RalB (with 86% sequence identity), constitute a distinct family of Ras-related GTPases, of which RalA is the most similar to Ras H, N, and K (with 48% sequence identity) (16). RalA mediates a distinct downstream signaling pathway from Ras that facilitates cellular transformation (17). RalA is also thought to be involved in numerous signaling cascades, including regulation of the cytoskeleton (18), vesicle trafficking, and endocytosis (19–22). Recently, it has been shown that Ral GTPases are important in human cell proliferation and survival (23). RalA is not ribosylated by C3bot1 and lacks a target residue equivalent to the one in RhoA (Asn-41). Instead, C3bot1 and RalA bind in a manner that prevents ribosylation of RhoA by C3bot1 and the stimulation of phospholipase D1 activity by RalA (15). The inhibition of C3bot1 by RalA and the subsequent interference with RalA function may partly explain some experimental cellular effects of C3bot1 that were independent of Rho (15). Interestingly, the interaction also increases the glycohydrolase activity of C3bot1 that takes place in the absence of Rho. This interaction with RalA has also been shown to be common with C3lim and C3cer (but not C3stau2), although the affinity for RalA seems to vary. In the case of C3bot1 and C3lim, however, the complex seems to be very tight, with the Kd of RalA for C3lim being 12 nM (15).

The structures of C3bot1 and RalA are already known but have revealed these proteins to be very flexible, leaving large uncertainties as to how and in what conformation they might interact. The structures of C3bot1 (24–26) and C3stau2 (27) in the presence and absence of NAD have shown that the key regions involved in NAD binding and ADP-ribosylation undergo conformational changes. RalA, like other small GTPases, contains two flexible switch regions (28). The signaling status of the Ras-related GTPases is determined by the conformation of these switch regions, which alter shape depending on whether GTP or GDP is bound.

To understand the specificity of C3bot1 interactions, we have determined the structure of C3bot1 and RalA in the presence of GDP at a resolution of 2.66 Å. The structure provides an insight into the specific recognition of RalA by C3bot1 and, by sequence comparison with other C3 exoenzymes, suggests why the binding strength of this interaction varies among them. Furthermore, by superposition of RhoA and Ras with RalA, we propose to answer why they do not bind C3 in a similar manner.

Experimental Procedures

Protein Expression and Purification. The human RalA gene clone (as a pGEX–2T fusion) was a kind gift of Hiroshi Koide (Kanazawa University, Kanazawa, Japan). The plasmid was transferred to the Escherichia coli host strain JM109 for expression. The clone was inoculated into 100 ml of Terrific Broth (Becton Dickinson) supplemented with 0.5% glucose and 100 μg/ml ampicillin and grown overnight at 37°C. The culture was diluted 1:50 in fresh medium and grown for 4 h at 37°C (OD600 ≈ 0.8). Expression was induced by the addition of isopropyl β-d-thiogalactoside to a final concentration of 1 mM, and the culture was grown for an additional 4 h at 25°C. The cells were harvested by centrifugation and resuspended in 50 mM BisTris (pH 7.0)/0.5 M NaCl/1 mg/ml lysozyme and left on ice for 45 min. The cells were lysed by sonication, and the cell debris was removed by centrifugation.

The RalA–GST fusion protein was initially purified by GST-affinity chromatography. The protein bound to the GST-trap column (Amersham Pharmacia) equilibrated with 50 mM Bis-Tris (pH 7.0)/0.5 M NaCl and was eluted with 20 mM Tris (pH 8.0)/0.2 M NaCl/10 mM reduced glutathione as a single peak. The peak was dialyzed overnight into 20 mM Hepes (pH 7.3)/150 mM NaCl/5 mM MgCl2/2.5 mM CaCl2 with 1 unit of thrombin per 100 μg of protein. The cleaved RalA was separated from the GST by reapplication to the GST-trap column and collection of the nonbound protein. The RalA protein was concentrated in a 10-kDa centrifugal concentrator (Amicon) and applied to a Superdex 200 gel filtration column (Amersham Pharmacia) equilibrated with 20 mM Hepes (pH 7.3)/20 mM NaCl/5 mM MgCl2/1 mM EDTA. The purified sample was further concentrated to 10 mg/ml and stored for crystallization at –20°C.

C3bot1 was expressed and purified as described in ref. 25. Briefly, the protein was expressed in E. coli JM109 as a maltose-binding fusion protein. The soluble lysate was passed through an SP Sepharose column equilibrated with 20 mM Hepes/NaOH (pH 7.3). The protein was then eluted with an ascending NaCl concentration gradient and treated with factor Xa to release C3bot1. The protein was further purified by cation-exchange and gel-filtration chromatography and, finally, concentrated. The final preparation (at 10 mg/ml concentration) was stored at –20°C in 20 mM Hepes/NaOH (pH 7.3)/120 mM NaCl for crystallization.

X-Ray Crystallographic Analysis. Native gels were run with various ratios of C3bot1 to RalA. These gels showed a band that could indicate a complex with a 1:2 molar ratio of C3bot1 to RalA, and therefore this ratio was used to set up crystallization trials. Hanging drops containing 2.0 μl of C3bot1–RalA complex (6.67 mg/ml RalA and 3.33 mg/ml C3bot1 mixture stabilized overnight at 4°C) and 2.0 μl of reservoir solution [0.1 M Hepes (pH 7.3)/12–15% ethylene glycol/14–18% polyethylene glycol (PEG) 8000] were incubated at 16°C and produced crystals within 3–4 d.

Diffraction data to 2.66 Å were collected from a single cryocooled (100 K) crystal with 25% ethylene glycol on station PX9.6 of the synchrotron radiation source (Daresbury, U.K.) by using a Quantum 4 charge-coupled-device detector (Area Detection Systems, Poway, CA). The data were processed and scaled by using the hkl-2000 software package (HKL Research, Charlottesville, VA) (29, 30). The symmetry and systematic absences were consistent with the P212121 space group (unit cell dimensions, a = 56.63 Å; b = 90.84 Å; and c = 100.40 Å) with one C3bot1–RalA complex per asymmetric unit, and the crystals contained ≈54% solvent. Data reduction was carried out by using the CCP4 program truncate (31) (Table 1).

Table 1. Crystallographic data.

| Resolution range, Å | 50-2.66 |

| No. of reflections measured | 242,860 |

| No. of unique reflections | 15,556 |

| I/σ(I) (outer shell*) | 14.6 (5.8) |

| Completeness (outer shell*), % | 99.8 (99.9) |

| Rsymm (outer shell*), % | 11.1 (26.0) |

| Rcryst, % | 20.6 |

| Rfree†, % | 27.4 |

| Average temperature factor Å2 | |

| RalA main-chain (side-chain) | 20.4 (21.9) |

| C3 main-chain (side-chain) | 21.9 (22.8) |

| Ligand | 20.0 |

| Solvent | 25.6 |

| Mg2+ ion | 19.3 |

| RMSD from ideal values | |

| Bond lengths, Å | 0.006 |

| Bond angles, ° | 1.1 |

RMSD, root-mean-square deviation.

Outer shell, 2.76-2.66 Å.

Rfree calculation used 917 (5.9%) reflections.

The structure of the C3bot1–RalA complex was determined by the molecular replacement method with the CCP4 program molrep (32) by using Protein Data Bank entries 1G24 for native C3bot1 (24) and 1UAD for RalA from the RalA–Sec5 complex (28) as search models. Initial refinement of the structure was carried out by using the CCP4 program refmac5 (33), which improved the model. Subsequent rounds of refinement were carried out by using the cns suite (Yale University, New Haven, CT) (34), and the model was built by using the program o (35) (Uppsala University, Uppsala, Sweden). In each data set, a set of reflections was kept aside for Rfree calculation (36). Water molecules were added by using the waterpick module of cns. The clear continuous density observed (in both the 2Fo – Fc and Fo – Fc sigma-weighted maps) in the GTP-binding pocket during the final stages of the refinement was interpreted as GDP. All figures were generated by using molscript (37) and rendered in povray (www.povray.org).

Results and Discussion

Overall Structure of the C3bot1–RalA Complex. The final refined structure of the C3bot1–RalA complex at a resolution of 2.66 Å (Fig. 1) has a conventional R factor (Rcryst) of 20.64% and a free R factor (Rfree) of 27.36% (Table 1). The final model of the complex contains 3,010 protein atoms, 260 water molecules, and one GDP molecule, with a Mg2+ ion, bound to RalA. The side chains for residues 54, 106, 152, 181, and 182 in C3bot1 and residues 11 and 119 in RalA were partially disordered and modeled on the basis of weak density with zero occupancy. The backbone density for residues 210 and 211 in C3bot1 was also unclear, but those residues were also modeled on the basis of weak density with zero occupancy. Analysis of the Ramachandran plot generated by using the program procheck (38) indicated that 86.5% of the residues lie in the most favorable region, and ≈13.2% lie in the additionally allowed regions.

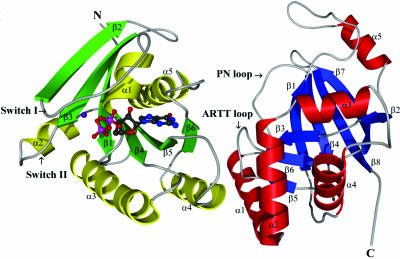

Fig. 1.

Ribbon representation of the C3bot1–RalA complex. The RalA is drawn with the helices in yellow and the strands in green. The C3bot1 has the helices in red and the strands in blue. The GDP (colored by atom) and Mg2+ ion (purple) are shown in the GDP-binding pocket of RalA. The switch I and II regions of RalA and the ADP-ribosylating turn–turn (ARTT) and phosphate-nicotinamide (PN) loops of C3bot1 are labeled.

C3bot1. The overall topology of C3bot1 in the complex is similar to that of previously determined structures of native C3bot1 molecules (24–26) (Fig. 1). Briefly, the structure of C3bot1 consists of a mixed α/β core. A five-stranded mixed β-sheet (β1, β2, β4, β7, and β8) stacks perpendicularly against a three-stranded antiparallel β-sheet (β3, β5, and β6) with four helices (α1, α2, α3, and α4) arrayed around the three-stranded sheet plus a fifth helix (α5) flanking the five-stranded sheet. A least-squares superposition of the C3bot1 from the RalA complex (present study) and free form (PDB ID code 1G24) (24) yields a root-mean-square deviation of 0.79 Å for 207 Cα atoms. The largest noticeable difference between the structures is the conformation of the ARTT loop. This loop, comprising residues 207–214, houses the catalytic residue Glu-214 and has been shown to be key in facilitating ADP-ribosyltransfer (24, 26). There is also a change in conformation for residues 232–236 between strands β7 and β8 on the surface of the molecule.

RalA and GDP Binding. The RalA molecule is constructed from a six-stranded mixed β-sheet sandwiched between five α-helices (Fig. 1); three helices (α2, α3, and α4) lie below the plane of the β-sheet, and two helices (α1 and α5) lie above. RalA, like the other related low-molecular-weight GTPases, possesses two switch regions that form part of the GDP-binding pocket and change conformation on GTP or GDP binding. In RalA, the switch regions comprise residues 40–48 (switch I, between helix α1 and strand β2) and residues 70–78 (switch II, between helix α2 and strand β3). These regions, which display a wide range of conformations among known GTPase structures, are well ordered in the C3bot1–RalA complex structure. Although GDP was not in the crystallization solution, a large patch of continuous-difference electron density was noticed around the switch I region. During refinement, this electron density was modeled as a GDP molecule and a Mg2+ ion (coordinating the GDP molecule), resulting in a drop in the R factors and significant improvement in the electron-density map around this region. The GDP-binding site has a total buried surface area of 808.9 Å2, 9.25% of the RalA–GDP total surface area (8,743.8 Å2). The binding of GDP to RalA in the C3bot1–RalA complex is somewhat different than that of GppNHp (guanosine 5′-[β,γ-imido]triphosphate, a nonhydrolyzable GTP analogue) to RalA in the RalA–Sec5 complex (28), following the normal mode of GDP binding seen in other small G proteins (39). The guanine base is recognized by residues from the consensus sequence NKXD (loop between α4 and β5) with Lys-128 and Asp-130 making direct interaction with the nucleotide. In addition, part of the loop located between helix α5 and strand β6 acts as a recognition site for the guanine base in both structures. The loop (also known as a P loop), connecting strand β1 and helix α1, houses the α- and β-phosphate groups. The binding of GDP requires coordination by the Mg2+ ion (square pyramidal geometry) that binds the β-phosphate oxygen. The other coordinating atoms for the Mg2+ are provided by three water molecules and the Oγ atom of Ser-28 from the α1 helix.

Superposition of the RalA molecule from the C3bot1–RalA complex with the RalA–Sec5 complex (PDB ID code 1UAD) (28) shows a root-mean-square deviation of 1.2 Å for 172 Cα atoms, although this value is biased by different conformation of the switch I and switch II regions (root-mean-square deviations of 2.6 and 2.2 Å, respectively). The striking conformational differences in the RalA switch regions between the Sec5 and the C3bot1 complexes, in particular, switch I, can be attributed to the different nucleotides bound, the GTP analogue GppNHp in the Sec5 complex, and GDP in our C3bot1 complex. An exchange of GDP to GTP would be unlikely to cause any changes in the RalA–C3bot1 structure, however, because the switch regions are not involved in the binding of C3bot1, and previous studies have shown the binding to be nucleotide-independent (15).

The C3bot1–RalA Interface. Sixteen residues (nine from C3bot1 and seven from RalA, which are well ordered and clearly defined in the electron-density map) provide all the interactions at the binding interface (Fig. 2A). The contact residues on C3bot1 are positioned on helices α1 and α2 and the ARTT loop. The contacts on the RalA molecule are distributed on helix α4 and strand β6. This orientation of the complex is notable because RalA binds C3bot1 at the same position that RhoA is presumed to bind (at the ARTT loop) but in a different orientation. The ribosylation target of C3bot1 in RhoA (Asn-41) is close to switch I, but, in the C3bot1–RalA complex, the switch regions I and II and the GDP-binding pocket are on the opposite side of RalA to the binding interface. The interaction of RalA with the ARTT loop of C3bot1, the C3bot1 active site, implies that RalA inhibits RhoA ribosylation by blocking the RhoA-binding site.

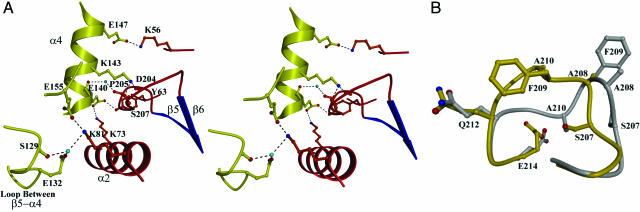

Fig. 2.

The C3bot1–RalA interface and ARTT loop. (A) Close-up stereoview of the interface between C3bot1 (red and blue) and RalA (yellow) with two water molecules (turquoise). The dashed lines represent hydrogen bonds. (B) Superposition of the ARTT loop from the native C3bot1 structure (gray) and the complex (yellow).

There are a total of 22 interactions at the interface between 14 RalA atoms (3 main-chain and 11 side-chain atoms) and 14 C3bot1 atoms (6 main-chain and 8 side-chain atoms) (Tables 2, 3, and 4). Some 642.3 Å2 of the total accessible surface area is buried at the interface upon complex formation (compared with 925 Å2 in the Sec5–RalA complex) (28), equivalent to 3.5% of the total surface area of the C3bot1–RalA complex.

Table 2. Details of interface interactions between C3bot1 and RalA.

| C3bot1 residue | B factor, Å2 | RalA residue | B factor, Å2 | Distance D... A, Å |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asp-204 O | 20.7 | Lys-143 Nζ | 21.8 | 2.6 |

| Ser-207 O | 33.1 | Lys-143 Nζ | 21.8 | 2.6 |

| Lys-56 Nζ | 32.3 | Glu-147 Oε2 | 45.0 | 2.8 |

| Lys-73 Nζ | 22.4 | Glu-140 Oε1 | 25.4 | 2.9 |

| Tyr-63 Oη | 27.2 | Glu-140 Oε2 | 24.9 | 2.7 |

| Lys-81 Nζ | 22.4 | Glu-155 Oε1 | 20.1 | 2.6 |

Table 3. Contacts in the C3bot1–RalA structure.

| RalA residue | C3bot1 residue | Distance, Å |

|---|---|---|

| Val-139 Cγ2 | Val-77 Cγ1 | 3.6 |

| Glu-140 Cα | Ile206 Cγ2 | 4.0 |

| Glu-140 Cβ | Ile-206 Cγ2 | 3.6 |

| Glu-140 Cδ | Tyr-63 Oη | 3.5 |

| Lys-73 Nζ | 3.8 | |

| Glu-140 Oε2 | Tyr-63 Cζ | 3.4 |

| Lys-143 Cδ | Pro-205 C | 3.9 |

| Pro-205 O | 3.5 | |

| Asp-204 O | 3.7 | |

| Ser-207 O | 3.6 | |

| Lys-143 Cε | Ser-207 O | 3.4 |

| Lys-143 Nζ | Asp-204 C | 3.7 |

| Ser-207 C | 3.4 |

van der Waals contact distances are calculated by using the program CONTACT (31).

Table 4. Water-mediated hydrogen bonds.

| C3bot1 residue | Distance to H2O, Å | RalA residue | Distance to H2O, Å |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lys-81 Nζ | 2.9 | Ser-129 O | 2.6 |

| Glu-132 Oε1 | 3.0 | ||

| Pro-205 O | 2.6 | Glu-140 O | 2.6 |

The Role of the C3bot1 ARTT and PN Loops at the Interface. The ARTT loop (residues 207–214) in the C3bot1 has been established by structural and mutational studies to be the key region responsible for ADP-ribose transfer. It contains residues Gln-212 and Glu-214 conserved across all C3 exoenzymes, which are essential for the transfer of ADP-ribose onto the Asn-41 of RhoA (26, 40). The ARTT loop also contains Phe-209, which has been implicated in RhoA binding by mutational studies with a Phe-209-Ala C3bot1 mutant (15). Interestingly, the ability of this mutant to bind RalA suggested that RalA did not interact with the ARTT loop. In our structure, this loop is well ordered, apart from residues Ala-210 and Gly-211.

The interface is centered on the ARTT loop of C3bot1, and the Lys-143 of RalA sits in a groove of the ARTT loop, forming hydrogen bonds with the main-chain carbonyls of Asp-204 and Ser-207 (Fig. 2 A). The main-chain carbonyl oxygen of Pro-205 in the ARTT loop also forms a water-mediated interaction with the main-chain carbonyl oxygen of Glu-140 on helix α4 of RalA. The interface is anchored at both ends, however, by three salt bridges (referred to as hydrogen bonds because of their distance and angle but which could be partly electrostatic in nature). The two lysine residues (Lys-73 and Lys-81) that lie on helix α2 of C3bot1 anchor the bottom half of the interface, forming hydrogen bonds with Glu-140 and Glu-155 (RalA), respectively, and also water-mediated interactions with Glu-132 and the carbonyl oxygen of Ser-129. Lys-56 from C3bot1 and Glu-147 from RalA anchor the top end of the interface.

A comparison of the RalA–C3bot1 complex with the native (24) and NAD-bound (26) C3bot1 structures shows that part of the ARTT loop undergoes a significant conformational change upon RalA binding (root-mean-square deviation of 2.94 Å for six Cα atoms between residues Ile-206 and Gly-211) different from that seen for NAD binding (Fig. 2B). The C3bot1 residues Ser-207 and Ala-208 are slightly twisted in the RalA-bound structure, so that the carbonyl oxygen of Ser-207 is positioned optimally for binding to the Lys-143 of RalA. The side chain of Ser-207 is placed on the inside of the loop (aligning with Ala-210 in the native structure), effectively shortening the loop by a residue and placing Ala-208 (in the complex) in the same place as Phe-209 (in the native structure). In the native structure, the Phe-209 ring protrudes into the solvent, but the effective shortening of the ARTT loop in the complex allows the phenylalanine ring to rotate and face away from the interface, preventing disruption of the bond between Lys-56 (RalA) and Glu-147 (C3bot1). The shift of this hydrophobic residue may also facilitate the interaction of Lys-143 (RalA) and Asp-204 (C3bot1) and explains why the Phe-209-Ala mutation had no effect on RalA binding (15). The alternate conformation of the ARTT loop also appears to indicate that Ala-210 is shifted so that it points inwards, toward the core of C3bot1. The apparent kink in the loop at Ala-210 and Gly-211, although unclear in the density map, is necessary to bring the sequence back into line with the native structure because the position of Gln-212 is similar in the two structures (displacement for Cα of 0.39 Å).

Although the ARTT loop undergoes a large shift upon RalA binding, the catalytic residue, Glu-214, is in the same position and available for NAD hydrolysis. Because the mechanism of NAD hydrolysis is not fully understood, how the binding of RalA increases the rate of hydrolysis (15) is not clear, although this finding is similar to the increase in NAD hydrolysis observed on binding mutant RhoA with ADP-ribose-acceptor residue removed (41). However, it is possible that either the conformation of the ARTT loop or a difference in its mobility may contribute toward these observations.

The previously determined C3bot1–NAD structure has shown that the PN loop (residues 177–186), connecting strands β3 and β4, rearranges to enclose the nicotinamide moiety of the NAD upon binding (26) and is, therefore, thought to play a key role in NAD hydrolysis. The loss of Arg-186 (in the PN loop) has been shown to abolish NAD binding and prevent ribosylation of RhoA (26). NAD is not bound to the C3bot1–RalA complex and the PN loop, which is 10 Å away from the nearest RalA residue, adopts a conformation similar to the free-C3bot1 structure and is not involved in RalA binding. It has been suggested that changes in the structure of the PN loop may account for the increased rate of glycohydrolysis observed upon C3bot1 binding to RalA (15), but this suggestion is not supported by our structure. It would be supposed that the PN loop would change conformation upon NAD binding of the C3bot1–RalA complex, but, from comparison with the C3bot1-NAD complex, it seems very unlikely that this change in conformation would cause the PN loop to interact with the RalA.

Implications of the C3bot1–RalA Interaction for Other C3 Exoenzymes. The structure of the C3bot1–RalA complex highlights structural elements relevant for the recognition of C3 exoenzymes by RalA. It is known that RalA inhibits the ribosylation of RhoA by C3cer and C3lim as well as C3bot1. This inhibition is to a lesser extent than C3bot1 (63% for C3lim and 24% for C3cer, measured as the percentage of ribosylated RhoA compared with C3bot1 after 30 min), suggesting a lower binding affinity for RalA (15). Interestingly, the closely related C3 exoenzyme C3stau2 from S. aureus, which shares 35% similarity with C3bot1, shows no binding to RalA. A comparison of the sequence alignment of the related C3 exoenzymes C3bot1, C3lim, C3cer, and C3stau2 with our structure allows us to offer an explanation for these differences (Fig. 3A).

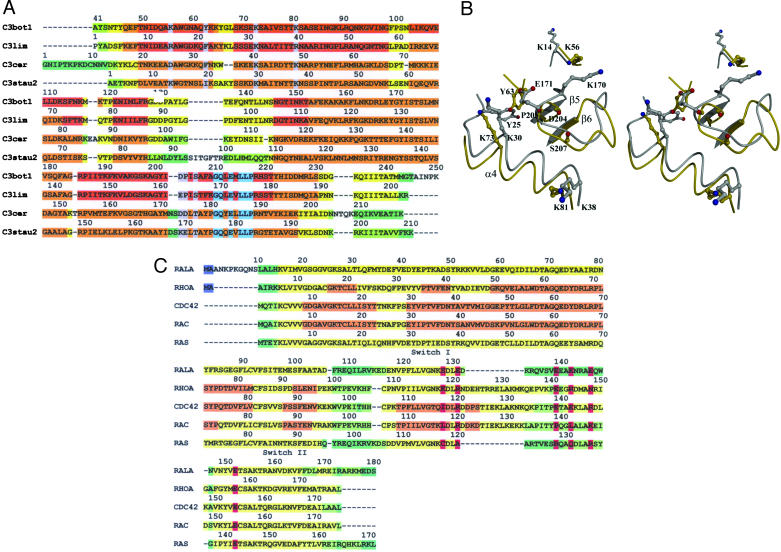

Fig. 3.

Comparison of the interface regions for the C3 exoenzymes and the Rho and Ras GTPases. (A) Sequence alignment performed by t-coffee (43) of the related C3 exoenzymes, colored by similarity, with orange being the most similar and green the least similar. The sequences are numbered starting at the first residue of the mature protein, with the exception of C3bot1, which is numbered like the crystal structures (24–26). The residue to which the number applies is the one under the first digit. The conserved residues within the ARTT loop (207–214) are highlighted in turquoise. The seven residues that interact (through H-bond) with RalA (K56, Y63, K73, K81, D204, P205, and S207) are shaded in gray. (B) Detailed stereoview of the C3bot1 (gold) RalA-binding region illustrating all the residues involved in the binding and their equivalent residues in the overlaid C3stau2 (silver). (C) Sequence alignment performed by t-coffee (43) of the related GTPases, colored by similarity and numbered as in A. The sequences are all numbered from the first residue of the protein. The residues that interact (through H-bond) with C3bot1 (highlighted in red) are S129, E132, E140, K143, E147, and E155.

Of the six residues in C3bot1 involved in direct RalA binding, Lys-56, Tyr-63, Lys-81, and Asp-204 are not conserved in C3lim (although it is the backbone carbonyl of Asp-204 that binds RalA), offering an obvious explanation for the difference in binding strength. However, the substitutions are conservative, and the ability of C3lim to bind RalA suggests that C3lim still offers a functional binding face. C3cer appears to have a lower affinity for RalA than C3bot1 and C3lim that is consistent with RalA's additional sequence differences. C3cer and C3stau2 have two extra residues in the ARTT loop that could interfere with binding. The superposition of C3stau2 (27) with the C3bot1–RalA complex (Fig. 3B) reveals that the extra length of the ARRT loop may be the cause of its inability to bind RalA. The two additional residues in the ARTT loop of C3stau2, Lys-170 and Glu-171, extend the ARTT loop forward into the RalA interface region. In particular, the exchange of Pro-205 (C3bot1) to Glu-171 (C3stau2) would obscure the hydrogen bond between Asp-168 (equivalent to Asp-204 in C3bot1) and Lys-143 (RalA) and the water-mediated interaction between Glu-140 (RalA) and the backbone at this position (Pro-205 in C3bot1). The equivalent residues in the C3cer are smaller (both aspartate) and are presumably less detrimental to RalA binding.

This comparison of the C3 exoenzymes, therefore, also allows speculation as to which residues in the interface are most crucial to the interaction. It is interesting to note that the residues conserved between C3bot1 and C3lim (Pro-205, Ser-207, and Lys-73 in C3bot1) and the presumably conserved interaction of the backbone oxygen at Asp-204 in C3bot1 are clustered at the center of the interface. It is also two of these interactions (of Asp-204 and Pro-205 in C3bot1) that may be disrupted in C3stau2 by the extra length of the ARTT loop. These central interactions would therefore appear to be the key residues in the interface, held in position to different extents by the outer interactions. Of the two outer interactions, the bonds formed by the two lysines of C3bot1 (Lys-56 and Lys-81) would appear to promote a more ideal binding face than the equivalent two arginines in C3lim, as judged by the biochemical data (15).

The Specificity of RalA for C3bot1. The well documented specificity of C3bot1 for ribosylation of RhoA-C by the ARTT loop and our findings that RalA binds at the same site lead to the question of whether RhoA or other GTPases could bind C3bot1 in the same orientation as RalA. The sequence alignment of RalA with Ras, RhoA, and the Rho-related Rac and Cdc42 shows that not all the RalA-binding residues are conserved across these GTPases (Fig. 3C). Of the four direct-binding residues involved in the RalA interface, only Glu-147 is conserved in all five GTPases. In particular, Ras replaces the Glu-140 and Glu-147 of RalA with the positively charged arginines, disallowing interactions with the Lys-73, Tyr-63, and Lys-56 of C3bot1. These sequence differences in Ras would prevent half of the direct-binding interactions available to RalA in the C3bot1–RalA complex. Also, RhoA, Cdc42, and Rac all show a conserved change of Glu-132 (RalA) to an arginine that may affect the water-mediated interaction with the Lys-81 of C3bot1. Similarly, this residue is replaced by an alanine in Ras.

Surprisingly, RhoA shows the greatest degree of similarity to RalA at these residues, even though RhoA is ribosylated by C3bot1 at Asn-41. Because this ribosylation occurs on the opposite side of RhoA from the equivalent RalA-binding face, it is presumed that the residues around the ribosylation site provide a better interface. These comparisons suggest that the interaction between RalA and C3bot1 is not related to the highly specific ribosylating activity that C3bot1 possesses for RhoA but is more dependent on specific RalA residues not present in RhoA. In particular, the Lys-143 of RalA, which makes two of the central interactions of the interface and sits in a groove of the ARTT loop, is not conserved in any of the other GTPases. It is this residue and Glu-140 that form the central interactions presumed to be common between C3bot1 and C3lim. Additionally, Lys-143 and Glu-140 bury 94 Å2 and 90 Å2 of solvent-accessible surface area, respectively, upon complex formation, making them ideal candidates for anchoring residues (42).

Conclusion. The structure of the C3bot1–RalA complex has answered some important questions about the unusual nature of the C3bot1–RalA interaction. The binding of RalA to the ARTT loop of C3bot1, blocking the presumed RhoA-binding site, explains its inability to ribosylate RhoA. The variation in binding affinity for RalA observed among the C3 exoenzymes is proposed to be due to sequence differences at the RalA interface and the variation in ARTT loop lengths. Similarly, sequence differences between RalA and the Ras- and Rho-related GTPases explain why the latter cannot imitate the RalA binding.

Acknowledgments

We thank the scientists at the Synchrotron Radiation Source (Daresbury, U.K.) and Shalini Iyer for help with x-ray data collection and Matthew Baker for help with computing. This work was supported by a joint postgraduate studentship from the Health Protection Agency and University of Bath (to K.P.H.).

Author contributions: K.P.H., J.M.S., and K.R.A. performed research; K.P.H. and K.R.A. analyzed data; and K.P.H., H.R.E., C.C.S., and K.R.A. wrote the paper.

Abbreviations: ARTT, ADP-ribosylating turn–turn; PN, phosphate-nicotinamide.

Data deposition: The atomic coordinates and structure factors for the C3bot1–RalA complex have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, www.pdb.org (PDB ID code 1WCA).

References

- 1.Passador, L. & Iglewski, W. (1994) Methods Enzymol. 235, 617–631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kreuger, K. M. & Barbieri, J. T. (1995) Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 8, 34–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Popoff, M. R., Hauser, D., Boquet, P., Eklund, M. W. & Gill, D. M. (1991) Infect. Immun. 59, 3673–3679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aktories, K., Rosener, S., Blaschke, U. & Chhatwal, G. S. (1988) Eur. J. Biochem. 172, 445–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wilde, C. & Aktories, K. (2001) Toxicon 39, 1647–1660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aktories, K., Braun, U., Rosener, S., Just, I. & Hall, A. (1989) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 158, 209–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chardin, P., Boquet, P., Madaule, P., Popoff, M. R., Rubin, E. J. & Gill, D. M. (1989) EMBO J. 8, 1087–1092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Williamson, K. C. L., Smith, A., Moss, J. & Vaughan, M. (1990) J. Biol. Chem. 265, 32820–32829. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aktories, K. & Hall, A. (1989) Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 10, 415–418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wilde, C., Chhatwal, G. S., Schmalzing, G., Aktories, K. & Just, I. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 9537–9542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ridley, A. J. (2001) Trends Cell Biol. 11, 471–477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rubin, E. J., Gill, D. M., Boquet, P. & Popoff, M. R. (1988) Mol. Cell. Biol. 8, 418–426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lehmann, M., Fournier, A., Selles-Navarro, I., Dergham, P., Sebok, A., Leclerc, N., Tigyi, G. & McKerracher, L. (1999) J. Neurosci. 19, 7537–7547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Watanabe, Y., Morimatsu, M. & Syuto, B. (2000) J. Vet. Med. Sci. 62, 473–478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wilde, C., Barth, H., Sehr, P., Han, L., Schmidt, M., Just, I. & Aktories, K. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 14771–14776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chardin, P. & Tavitian, A. (1986) EMBO J. 5, 2203–2208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Urano, T., Emkey, R. & Feig, L. A. (1996) EMBO J. 15, 810–816. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ohta, Y., Suzuki, N., Nakamura, S., Hartwig, J. H. & Stossel, T. P. (1999) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96, 2122–2128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nakashima, S., Morinaka, K., Koyama, S., Ikeda, M., Kishida, M., Okawa, K., Iwamatsu, A., Kishida, S. & Kikuchi, A. (1999) EMBO J. 18, 3629–3642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jullien-Flores, V., Dorseuil, O., Romero, F., Letourneur, F., Saragosti, S., Berger, R., Tavitian, A., Gacon, G. & Camonis, J. H. (1995) J. Biol. Chem. 270, 22473–22477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moskalenko, S., Henry, D. O., Rosse, C., Mirey, G., Camonis, J. H. & White, M. A. (2002) Nat. Cell Biol. 4, 66–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sugihara, K., Asano, S., Tanaka, K., Iwamatsu, A., Okawa, K. & Ohta, Y. (2002) Nat. Cell Biol. 4, 73–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chien, Y. & White, M. A. (2003) EMBO Rep. 4, 800–806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Han, S., Arvai, A. S., Clancy, S. B. & Tainer, J. A. (2001) J. Mol. Biol. 305, 95–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Evans, H. R., Holloway, D. E., Sutton, J. M., Ayriss, J., Shone, C. C. & Acharya, K. R. (2004) Acta Crystallogr. D 60, 1502–1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Menetrey, J., Flatau, G., Stura, E. A., Charbonnier, J. B., Gas, F., Teulon, J. M., Le Du, M. H., Boquet, P. & Menez, A. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 30950–30957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Evans, H. R., Sutton, J. M., Holloway, D. E., Ayriss, J., Shone, C. C. & Acharya, K. R. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 45924–45930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fukai, S., Matern, H. T., Jagath, J. R., Scheller, R. H. & Brunger, A. T. (2003) EMBO J. 22, 3267–3278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Otwinowski, Z. (1993) DENZO: An Oscillation Data Processing Program for Macromolecular Crystallography (Yale Univ. Press, New Haven, CT).

- 30.Otwinowski, Z. (1993) SCALEPACK: Software for the Scaling Together of Integrated Intensities Measured on a Number of Separate Diffraction Images (Yale Univ. Press, New Haven, CT).

- 31.Collaborative Computational Project, No. 4 (1994) Acta Crystallogr. D 50, 760–763.15299374 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vagin, A. & Teplyakov, A. (2000) Acta Crystallogr. D 56, 1622–1624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Murshudov, G. N. (1997) Acta Crystallogr. D 53, 240–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brünger, A. T., Adams, P. D., Clore, G. M., DeLano, W. L., Gros, P., GrosseKunstleve, R. W., Jiang, J. S., Kuszewski, J., Nilges, M., Pannu, N. S., et al. (1998) Acta Crystallogr. D 54, 905–921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jones, T. A., Zou, J. Y., Cowan, S. W. & Kjeldgaard, M. (1991) Acta Crystallogr. A 47, 109–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brünger, A. T. (1992) Nature 355, 472–474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Esnouf, R. M. (1997) J. Mol. Graphics 15, 132–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Laskowski, R. A., MacArthur, M. W., Moss, D. S. & Thornton, J. M. (1993) J. Appl. Crystallogr. 26, 283–291. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Takai, Y., Sasaki, T. & Matozaki, T. (2001) Physiol. Rev. 81, 153–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sekine, A., Fujiwara, M. & Narumiya, S. (1989) J. Biol. Chem. 264, 8602–8605. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wilde, C., Genth, H., Aktories, K. & Just, I. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 16478–16483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rajamani, D., Thiel, S., Vajda, S. & Camacho, C. J. (2004) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101, 11287–11292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Notredame, C., Higgins, D. G. & Heringa, J. (2000) J. Mol. Biol. 302, 205–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]