Abstract

Lignocellulosic biomass is the only renewable carbon resource available in sufficient amount on Earth to go beyond the fossil-based carbon economy. Its transformation requires controlled breakdown of polymers into a set of molecules to make fuels, chemicals and materials. But biomass is a network of various inter-connected polymers which are very difficult to deconstruct optimally. In particular, saccharification potential of lignocellulosic biomass depends on several complex chemical and physical factors. For the first time, an easily measurable fluorescence properties of steam-exploded biomass samples from miscanthus, poplar and wheat straw was shown to be directly correlated to their saccharification potential. Fluorescence can thus be advantageously used as a predictive method of biomass saccharification. The loss in fluorescence occurring after the steam explosion pretreatment and increasing with pretreatment severity does not originate from the loss in lignin content, but rather from a decrease of the lignin β-aryl-ether linkage content. Fluorescence lifetime analysis demonstrates that monolignols making lignin become highly conjugated after steam explosion pretreatment. These results reveal that lignin chemical composition is a more important feature to consider than its content to understand and to predict biomass saccharification.

Introduction

Lignocellulosic biomass is considered as a sustainable and alternative source of fuels, chemicals and materials. It refers to plant dry matter from various sources which are available or grown nearly in any location on Earth: agricultural by-products (e.g. cereal leaves and straws), wood (e.g. forest trees and short rotation crops) and dedicated crops (e.g. miscanthus). Lignocellulosic biomass production (crop residues and wood) in Europe was close to 750 million tons in 20111. In comparison to another plant product like starch, lignocellulosic biomass does not compete with feedstock. Therefore, valorisation of lignocellulosic biomass is expected to favour the transition from a fossil carbon-based to a green carbon-based economy, thus limiting greenhouse gas emission and climate changes which are strong policy priorities in Europe1.

Lignocellulosic biomass from grass and wood is mainly composed of three types of polymers that account for more than 90% of their dry weight: cellulose, hemicellulose and lignin2. Such polysaccharides and polyphenols are of great interest for producing green chemicals and materials, for example to produce composites including fibres or to ferment sugars in different compounds, including biofuels. But the high chemical and structural complexity of lignocellulosic biomass at different length-scales is also a limitation for the development of economically viable transformation3: that is why lignocellulosic biomass is known as a recalcitrant material4, 5.

Different routes exist for processing lignocellulose, often involving some pretreatments which are due to increase the efficiency of catalysts leading to products of interest6. The use of enzymes and micro-organisms is relevant since they are more selective (enzymes are specific catalysts) and saves more energy (enzymes work in mild temperature conditions and can often be recycled). But enzymatic catalysts which perform the hydrolysis reaction are nearly inactive if they are applied directly onto native raw lignocellulose biomass. A physicochemical pretreatment is necessary, to make the substrate less recalcitrant. Only after, a specific enzymatic hydrolysis of cellulose and hemicellulose is performed, in order to obtain the highest rate of sugars subsequently fermented by yeasts into fuels and chemicals7.

Making lignocellulose biomass less recalcitrant goes through the development of optimal pretreatments to favour the action of enzymes and of cellulases in particular8, 9. Many different pretreatments have been studied and can be applied to lignocellulosic biomass10, each having some advantages and drawbacks regarding efficiency, cost and production of inhibitors11. One efficient and industrially well-established pretreatment is steam explosion (SE). During SE, chipped biomass is subjected to high pressure water steam at temperatures ranging from 170 to 220 °C for a few minutes before a rapid return to atmospheric pressure, resulting in the biomass explosion10. SE efficiency is mainly due to the large increase of pore size and accessible surface area, combined with hemicellulose hydrolysis and partial lignin solubilisation10, 12, 13. Some acid catalysts such as dilute sulfuric acid can also be added to increase SE efficiency. Temperature and time of SE process have to be carefully controlled according to biomass characteristics (species, particle size, moisture) since some hydrolysis and fermentation inhibitors can be generated under high severity conditions11, 14.

Saccharification of pretreated biomass is dependent on many different physical and chemical factors15, so predicting glucose yield based on easily measurable parameters is very challenging. Lignin content and cellulose crystallinity are generally recognized as dominating factors16. Accessible surface area of pine wood pretreated with ionic liquid was perfectly fitted with saccharification, contrarily to lignin content17. The role of water interactions (state and location) with lignocellulose was also shown to be important in SE biomass18. Recent in-depth statistical analysis of the weight of different structural factors controlling hydrolysability of pretreated biomasses showed that many factors were involved and not a single one could explain saccharification19–21. Moreover, measuring parameters such as lignin content, cellulose crystallinity or porosity (for example through Simons’s staining or thermoporosimetry) is not straightforward nor rapid. Spectral parameters from infra-red spectroscopy data can more advantageously be used to accurately predict glucose yield after hydrolysis of wheat straw22, 23. Overall, relative importance of chemical and structural factors depends on biomass species, pretreatment type and process conditions, no general factor has been revealed until now24.

Another experimental parameter that can be easily measured on lignocellulosic samples is fluorescence. Plant cell wall are autofluorescent materials, containing some endogenous fluorophores, in particular aromatic molecules: monolignols in lignin25, ferulic acid and cinnamic acids in hemicellulose26. Lignin content in biomass feedstock is in the range 15–30%2. It is made of three different monolignols: coniferyl alcohol (CA), p-coumaryl alcohol and sinapyl alcohol (SA)25. Interestingly, these monolignols are non-conjugated moieties but display a high fluorescence27. Lignin autofluorescence is typically multimodal28 and highly complex, as revealed for example through lifetime imaging indicating variable spatial lignin distribution and spectral properties29. For imaging purpose, lignin autofluorescence is detrimental for detecting transgenic proteins in planta but particularly useful for observing plant cell wall architecture30. Overall, cell wall fluorescence depends on lignin composition, type and content of inter-linkages between monolignols and surrounding environment (vicinity of other fluorophores, interactions with other molecules, pH, ionic strength). So all these parameters possibly affect fluorophore extinction coefficient, quantum yield and lifetime thus modifying the fluorescence absorption, emission and intensity31. Goal of this study is to explain the loss in fluorescence observed in steam-exploded biomass samples and how it can be directly correlated to biomass digestibility.

Results

Enzymatic saccharification of biomass samples from miscanthus, poplar and wheat straw was conducted for 48 hrs and glucose concentration was evaluated for the untreated and pretreated samples at different severity factors (CSF) (Table 1 from ref. 32). Glucose release was lower in untreated samples, with notable difference between poplar (less than 1 g/L, corresponding to a glucose conversion yield of 7%) and wheat straw (more than 4 g/L, glucose yield of 51%). For samples pretreated with a severity of 2.0, glucose concentration reached 8–9 g/L and even more than 10 g/L for CSF 2.8, the highest severity tested. This means that pretreatment has increased by more than 2-fold (for wheat straw) to 10-fold (for poplar) the release of glucose, so that glucose yield was close to 100%. These results are in agreement with those previously published33.

Table 1.

Glucose concentration in g/L after a 48-hour saccharification by the Cellic CTec2 cocktail. NA: sample not available.

| Miscanthus | Poplar | Wheat straw | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Untreated | 1.82 ± 0.09 | 0.71 ± 0.13 | 4.41 ± 0.06 |

| Pretreated - CSF 2.0 | 8.42 ± 0.18 | 7.87 ± 0.66 | 9.06 ± 0.02 |

| Pretreated - CSF 2.6 | 10.48 ± 0.38 | 9.87 ± 0.23 | 10.46 ± 0.02 |

| Pretreated - CSF 2.7 | 10.67 ± 0.47 | NA | 10.31 ± 0.10 |

| Pretreated - CSF 2.8 | 10.11 ± 0.43 | 10.15 ± 0.51 | 10.36 ± 0.39 |

Means and standard deviations are based on measurements done in triplicate.

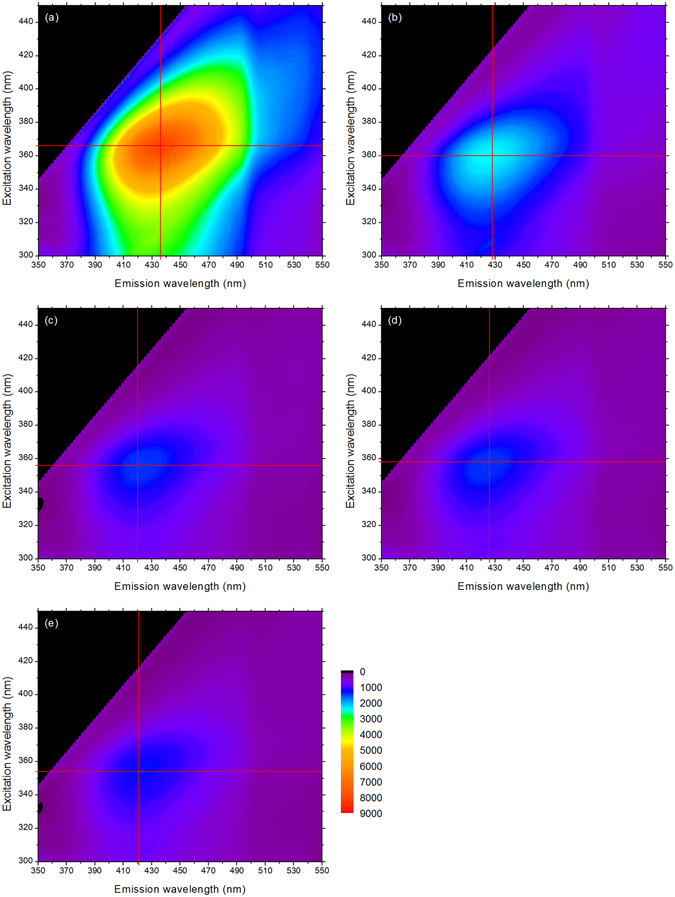

The same samples used for the saccharification measurements were used to prepare some KBr disks. KBr is commonly mixed with samples to be analysed by infrared spectroscopy since it is known to have a very low spectral absorption34. Some disks containing only KBr were prepared and analysed to check KBr absorption in the range 300–800 nm was negligible (data not shown). Fluorescence spectra measurements were performed for all untreated and pretreated samples with the same acquisition parameters. Only the gain value was adapted for each biomass species to get the highest fluorescence intensity value for the untreated samples. Fluorescence spectra are presented as 3D contour maps (Fig. 1; Supplementary Figs 1 and 2). For facilitating comparison, the maximum fluorescence intensity values were determined and are reported in Table 2, with corresponding maximum excitation and emission values. For miscanthus, untreated sample maximum fluorescence intensity (Fig. 1) reaches more than 8000. Even for the less drastically pretreated sample, maximum intensity is decreased by more than 3-fold. When CSF increases, intensity continues to decrease to be finally divided by 6. For poplar, untreated sample fluorescence intensity (Supplementary Fig. 1) also reaches more than 8000, but pretreated sample with CSF 2.0 has a maximum intensity only decreased by a bit more than 2-fold. Again, intensity is minimum for the most severely treated sample and gets divided by 6. Finally, for wheat straw (Supplementary Fig. 2), shape of the 3D map of the untreated sample is slightly different: instead of being circular like for miscanthus and poplar, it displays a larger surface for high excitation and emission values. Interestingly, fluorescence intensity for sample with CSF 2.0 is only decreased by 30%, and decreased by less than 50% for the most drastically treated sample.

Figure 1.

3D fluorescence contour map of miscanthus (a) untreated sample and pretreated samples with (b) CSF = 2.0, (c) CSF = 2.6, (d) CSF = 2.7, (e) CSF = 2.8. The red cross indicates the maximum fluorescence intensity value.

Table 2.

Maximum fluorescence intensity and corresponding excitation (λEX) and emission (λEM) wavelengths of untreated (UN) and pretreated samples from Fig. 1 and Supplementary Figs 1 and 2.

| Miscanthus | Poplar | Wheat straw | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maximum fluorescence intensity | λEX (nm) | λEM (nm) | Maximum fluorescence intensity | λEX (nm) | λEM (nm) | Maximum fluorescence intensity | λEX (nm) | λEM (nm) | |

| UN | 8100 | 366 | 436 | 8307 | 376 | 445 | 7536 | 358 | 441 |

| CSF 2.0 | 2450 | 360 | 428 | 3225 | 358 | 416 | 5086 | 352 | 424 |

| CSF 2.6 | 1480 | 356 | 420 | 1862 | 360 | 422 | 3921 | 348 | 422 |

| CSF 2.7 | 1462 | 358 | 426 | ND | ND | ND | 4030 | 352 | 422 |

| CSF 2.8 | 1342 | 354 | 421 | 1409 | 358 | 418 | 3994 | 352 | 417 |

| ΔCSF 2.8/UN | −84% | −12 | −15 | −83% | −18 | −27 | −47% | −6 | −24 |

Standard deviations from fluorescence intensity measurements done in triplicate are below 5%. ΔCSF 2.8/UN: variation between pretreated sample with CSF 2.8 and untreated sample.

Examination of maximum excitation and emission wavelengths (λEX and λEM) variations depending on pretreatment severity (Table 2) shows important decreases of both parameters: λEX is shifted from −6 to −18 nm (hypsochromic effect) while λEM is more altered with variations from −15 to −27 nm. Overall, each biomass has a different fluorescence profile along pretreatment severity: miscanthus is the most affected for the intensity loss, while poplar seems a little less modified for intermediate severity samples but maximum λEX and λEM are largely altered; wheat straw appears as the sample for which fluorescence is much less affected by pretreatment. Considering samples analysed, pretreatment has led to important decreases of fluorescence intensity (hypochromic effect) and to a blue-shift of both λEX and λEM (hypsochromic effect).

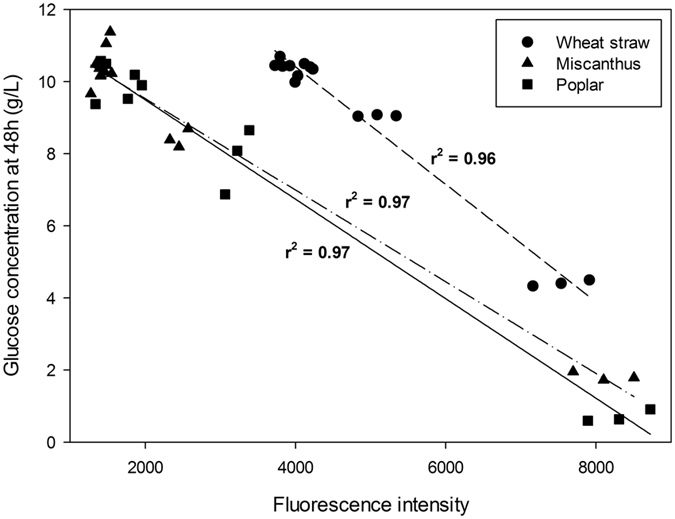

It has been shown previously on the same samples32 that when pretreatment severity was increased, saccharification was largely improved, while fluorescence intensity was reduced. Given that the fluorescence measurements can be easily carried out, it seemed interesting to try correlating the fluorescence intensity measured for each sample with the corresponding saccharification data. As a result, glucose concentration released after 48 hrs saccharification was plotted against maximum fluorescence intensity (Fig. 2). Calculated correlation coefficients indicated a very strong correlation between the two parameters since r 2 was in the range 0.96–0.97 (Fig. 2). Getting such a good agreement using between 12 and 15 different analysed samples for each biomass is particularly strong. To our knowledge, this is the first time that the glucose concentration released after the saccharification of untreated and steam-exploded samples from three different biomass species and using a commercial enzyme cocktail can be simply described by fluorescence measurement.

Figure 2.

Correlation between glucose concentration released after 48 hrs saccharification (from Table 1) and maximum fluorescence intensity (from Table 2) of untreated and pretreated samples. Correlation coefficient and related correlation line are drawn for each biomass sample (wheat straw: short dash line; miscanthus: dash and dot line; poplar: solid line).

Discussion

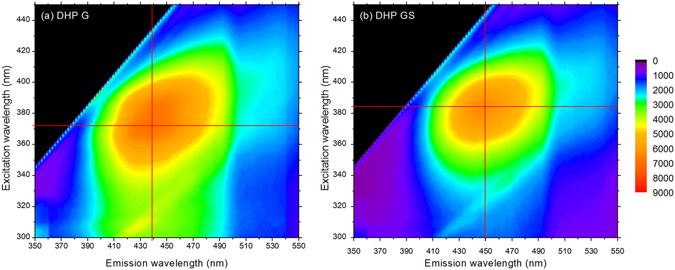

Effect of SE pretreatment on plant cell walls from different species has been well characterized regarding accessibility, chemical modifications and saccharification11, 20. But few studies have analysed the induced modification of lignin and its fluorescence. More generally, origin of lignin fluorescence has been mostly investigated in model lignin compounds35. In-depth characterization of model CA dilignols suggested that fluorophores are not significantly electronically coupled to one another and can be seen as isolated fluorophores27. But even model lignin polymers fluorescence differs significantly depending on their composition36. Recently, it has been proposed that lignin fluorescence may originate from its aggregation due in particular to clustering of the carbonyl groups37. Since the origin of lignocellulose fluorescence is questionable, some model lignin dehydrogenative polymers (DHPs) made of 100% CA (DHP G) and 50% CA + 50% SA (DHP GS) were synthesized38. Their fluorescence spectra (Fig. 3) indicates maximum λEX/λEM of 372 nm/439 nm and 382 nm/450 nm, respectively, in agreement with the values previously presented36. Patterns of native lignocellulosic samples (Fig. 1, Supplementary Figs 1 and 2) and of DHPs (Fig. 3) are very similar, demonstrating that autofluorescence of biomass mainly originates from lignin fluorescence.

Figure 3.

3D fluorescence contour map of model lignin DHPs: (a) DHP G made of 100% coniferyl alcohol and (b) DHP GS made of 50% coniferyl alcohol +50% sinapyl alcohol. The red cross indicates the maximum fluorescence intensity value.

Based on these information, the important loss in fluorescence observed in the SE samples can be attributed to one or several of the following causes: decrease of lignin content; alteration of linkages between monolignols making lignin; modification of the cross-linkages between lignin and hemicellulose and of the organization of the polymers (mainly cellulose and hemicellulose) surrounding lignin. If SE samples fluorescence was expected to be mainly influenced by the packing polymers around lignin, a possible approach could be to assay the lignin chemical and physical accessibility in the pretreated samples39, 40, but since samples were “exploded” after pretreatment, these techniques could not be applied. Previously, an in-depth chemical analysis of the same pretreated samples was performed. Results have shown that lignin content increased with increasing severity32 (Table 3) due to hemicellulose hydrolysis10. So loss in fluorescence cannot be attributed to some variations in the content of lignin.

Table 3.

Content in lignin and β-O-4′ inter-unit cross-linkages of untreated (UN) and pretreated samples (from ref. 32) and correlation coefficient between [β-O-4′] and fluorescence maximum intensity (from Table 2).

| [lignin] (% in weight) | [β-O-4′] (% of aromatic rings) | Fluorescence maximum intensity | Correlation coefficient | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Miscanthus | UN | 25.5 | 42.1 | 8100 | 0.99 |

| CSF 2.0 | 27.2 | 13.3 | 2450 | ||

| CSF 2.6 | 29.1 | 8.5 | 1480 | ||

| CSF 2.7 | 29.6 | 4.2 | 1462 | ||

| CSF 2.8 | 29.7 | ND | 1342 | ||

| Poplar | UN | 29.5 | 43.1 | 8307 | 0.91 |

| CSF 2.0 | 30.5 | 31.0 | 3225 | ||

| CSF 2.6 | 33.0 | 13.0 | 1862 | ||

| CSF 2.7 | ND | ND | ND | ||

| CSF 2.8 | 33.4 | 6.8 | 1409 | ||

| Wheat straw | UN | 24.6 | 45.3 | 7536 | 0.99 |

| CSF 2.0 | 24.6 | 20.3 | 5086 | ||

| CSF 2.6 | 27.3 | 12.4 | 3921 | ||

| CSF 2.7 | 27.2 | 8.1 | 4030 | ||

| CSF 2.8 | 30.1 | 9.3 | 3994 |

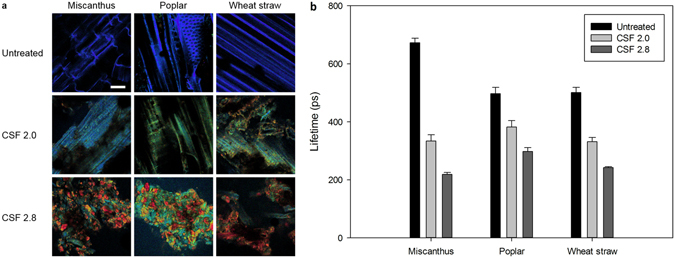

Besides, content in lignin inter-unit linkages (β-O-4′, β-5′, and β-β′) was also determined by 2D NMR32 (Table 3). In particular, the β-aryl ether linkages (β-O-4′) content was noticed to decrease with increasing pretreatment severity. Determination of the correlation coefficient between the β-aryl ether linkage content and the fluorescence maximum intensity for each untreated and pretreated biomass sample gives a very strong positive correlation (Table 3). If this correlation seems rational based on the fact that fluorescence of plant cell wall originates from lignin, this means that other parameters characterizing fluorescence, namely maximum fluorescence emission intensity and fluorescence lifetime (τ), should also be affected by SE pretreatment31. First, to illustrate the impact of pretreatment on fluorescence emission, spectral imaging of SE samples was done with a 750 nm biphoton wavelength (Fig. 4a). No differences based on biomass species could be noticed, rather an increasing shift of fluorescence emission with increasing severity was observed. Fluorescence lifetime of a fluorophore describes the fluorescence decay from an excited state to the ground state. Dissipation of energy through the emission of a photon is notably favoured by the presence of electron-rich bonds41. Determination of fluorescence lifetime of SE samples shows that untreated samples have higher τ values than pretreated samples, whatever the biomass species considered are (Fig. 4b). This means that high severity pretreatment, which was shown to be accompanied by lignin recondensation32, modifies the electronic environment of lignin, probably by the creation of highly conjugated monolignols. Overall, results on fluorescence characterization show that the loss in fluorescence observed after SE pretreatment can be directly attributed to the degradation of the β-aryl-ether linkages occurring during lignin depolymerisation/recondensation. In addition, recondensed lignin becomes an electron-dense polymer, despite the loss of β-aryl-ether linkages, involving the creation of uncharacterized linkages.

Figure 4.

Fluorescence properties of untreated and pretreatd samples. (a) Spectral image of autofluorescence after a bi-photon excitation at 750 nm, emission measured from 420 nm (blue) to 722 nm (red); scale-bar is 10 µm. (b) Fluorescence lifetime of untreated and pretreated samples. Fluorescence lifetime values are averaged from measurements on three different samples.

Regarding the correlation between biomass autofluorescence and saccharification potential, it was previously tested by measuring fluorescence, but at only two excitation wavelengths (405 and 561 nm), and only qualitative trends could be proposed42. Contrarily to this study and others43, biomass autofluorescence analysis presented here has been thoroughly made on a wide range of excitation wavelengths (300–450 nm), which has led to uncovering this new correlation between sample fluorescence and saccharification rate. So even if lignin content and saccharification efficiency are considered to be negatively correlated15, it does not seem to be a general trend. Rather, it seems pretreatment type and characterization of pretreatment effect on lignin chemical properties are more important to consider than lignin content alone to explain saccharification efficiency44. This result is for example consistent with the higher saccharification measured in transgenic poplar in which β-aryl-ether linkage content was decreased45. Consequently, this parameter is particularly important to take into account in the frame of pretreatment conditions optimisation and in the design of genetically modified lignins45–47.

In summary, pretreatment of lignocellulosic biomass is a crucial step in biorefineries to increase the accessibility of enzymes and to optimize their activity. SE is recognized as one of the most efficient existing pretreatments. But depending on biomass origin, the different parameters controlling the steam explosion step (temperature, pH, acid content) must be adapted. Consequently, biomass is more or less affected regarding its architecture and composition, so that saccharification can liberate more or less glucose. The simple, fast and cheap measurement of 3D fluorescence contour maps has been shown to be highly correlated to the glucose concentration released after 48 hrs. This technique can thus be used as a predictive method to determine the saccharification rate of steam-exploded pretreated samples, saving much time and materials. The origin of the fluorescence loss after SE pretreatment was unambiguously attributed to the loss in β-aryl-ether linkages in lignin, likely accompanied by the creation of highly conjugated linkages between monolignols which remain to be characterized.

Methods

Biomass pretreatment and hydrolysis

Three native and steam exploded Miscanthus x giganteus, poplar and wheat straw residues were selected and provided by Procethol 2 G (Pomacle, France)32. Each experimental condition imparted different severity which can be expressed as a combined severity factor (CSF). CSF was calculated using the following equation48:

| 1 |

where t is the reaction time (min), T is the operating temperature (°C), T R is the reference temperature (100 °C) and pH is that of the sulfuric acid solution used for biomass samples pre-soaking. The different CSF values ranged from 2.0 to 2.8.

Enzymatic saccharification assays of both native and steam exploded samples were used as received, without washing or further milling, using the commercial cellulase preparation Cellic CTec2 ®, courteously provided by Novozymes (Bagsværd, Danemark) as detailed previously32.

Spectrofluorimetry

For other experiments, samples were ball-milled in a 25 mL jar with 20 × 20 mm ZrO2 ball bearings using a Retsch MM2000 mixer mill for 2 min to achieve a size less than 80 µm. Disks were prepared by mixing 2 mg of biomass sample and 200 mg of KBr. Fluorescence spectra of the disks were measured in a Jasco FP-8300 instrument (Lisses, France). Acquisition parameters were as follows: range/precision for excitation and emission were 250–600 nm/2 nm and 260–650 nm/1 nm, respectively; excitation and emission bandwidth was 2.5 nm; scan speed was 1000 nm/min; gain value was adapted depending on the biomass considered: 600 V, 650 V and 700 V for miscanthus, poplar and wheat straw, respectively. Spectra acquisition was performed using Jasco Spectra Manager software.

Dehydrogenative polymer (DHP) synthesis was performed as previously explained38 and their fluorescence spectra was recorded with the same parameters as above, using a gain value of 750 V.

Autofluorescence and lifetime measurements

Spectral images were acquired using laser scanning microscope LSM 710 NLO Zeiss (Zeiss SAS, Germany) coupled with Chameleon TiSa accordable 80 Mhz pulsed laser (COHERENT,USA). Sample excitation was performed at 750 nm with two-photon laser and spectral images were acquired using spectral detector of the microscope on 32 channels between 420 and 722 nm with 20× objective (NA 0.8).

Lifetime measurements were acquired using a MW-FLIM detector system along the SPC 150 photocounting card from Becker & Hickl (Becker & Hickl, Germany). This system allowed to do lifetime measurements along 12.5 ns time-windows with a 16 spectral channels detector driven by SPCM software (Becker & Hickl). Lifetime trace of emitted photons was accumulated during 30 s simultaneously on all spectral channels of the MW-FLIM detector. Each lifetime trace was acquired on 1024 temporal channels. Lifetime traces were then processed using SPCMImage software (Becker & Hickl).

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

Anouck Habrant is acknowledged for the synthesis of model DHP lignin. This work was supported by BPI France in the frame of the Futurol project.

Author Contributions

T.A. and G.P. designed the research, T.A. and C.T. performed the experiments, G.P. drafted the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at doi:10.1038/s41598-017-08740-1

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Scarlat N, Dallemand J-F, Monforti-Ferrario F, Nita V. The role of biomass and bioenergy in a future bioeconomy: policies and facts. Environ. Dev. 2015;15:3–34. doi: 10.1016/j.envdev.2015.03.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pauly M, Keegstra K. Plant cell wall polymers as precursors for biofuels. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2010;13:305–312. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2009.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Viikari L, Vehmaanperä J, Koivula A. Lignocellulosic ethanol: From science to industry. Biomass Bioener. 2012;46:13–24. doi: 10.1016/j.biombioe.2012.05.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Himmel ME, et al. Biomass recalcitrance: Engineering plants and enzymes for biofuels production. Science. 2007;315:804–807. doi: 10.1126/science.1137016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burton RA, Gidley MJ, Fincher GB. Heterogeneity in the chemistry, structure and function of plant cell walls. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2010;6:724–732. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cherubini F, Stromman AH. Chemicals from lignocellulosic biomass: opportunities, perspectives, and potential of biorefinery systems. Biofuels Bioprod. Biorefining. 2011;5:548–561. doi: 10.1002/bbb.297. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chundawat SPS, Beckham GT, Himmel ME, Dale BE. Deconstruction of lignocellulosic biomass to fuels and chemicals. Annu. Rev. Chem. Biomol. Eng. 2011;2:121–145. doi: 10.1146/annurev-chembioeng-061010-114205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhao XB, Zhang LH, Liu DH. Biomass recalcitrance. Part II: fundamentals of different pre-treatments to increase the enzymatic digestibility of lignocellulose. Biofuels Bioprod. Biorefining. 2012;6:561–579. doi: 10.1002/bbb.1350. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Galbe M, Zacchi G. Pretreatment: The key to efficient utilization of lignocellulosic materials. Biomass Bioener. 2012;46:70–78. doi: 10.1016/j.biombioe.2012.03.026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Silveira MHL, et al. Current pretreatment technologies for the development of cellulosic ethanol and biorefineries. ChemSusChem. 2015;8:3366–3390. doi: 10.1002/cssc.201500282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sun S, Sun S, Cao X, Sun R. The role of pretreatment in improving the enzymatic hydrolysis of lignocellulosic materials. Biores. Technol. 2016;199:49–58. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2015.08.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Donaldson LA, Wong KKY, Mackie KL. Ultrastructure of steam-exploded wood. Wood Sci. Technol. 1988;22:103–114. doi: 10.1007/BF00355846. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Muzamal, M., Jedvert, K., Theliander, H. & Rasmuson, A. Structural changes in spruce wood during different steps of steam explosion pretreatment. Holzforschung69 (2015).

- 14.Zhai R, Hu J, Saddler JN. What are the major components in steam pretreated lignocellulosic biomass that inhibit the efficacy of cellulase enzyme mixtures? ACS Sus. Chem. Eng. 2016;4:3429–3436. doi: 10.1021/acssuschemeng.6b00481. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhao XB, Zhang LH, Liu DH. Biomass recalcitrance. Part I: the chemical compositions and physical structures affecting the enzymatic hydrolysis of lignocellulose. Biofuels Bioprod. Biorefining. 2012;6:465–482. doi: 10.1002/bbb.1331. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhu L, O’Dwyer JP, Chang VS, Granda CB, Holtzapple MT. Structural features affecting biomass enzymatic digestibility. Bioresour Technol. 2008;99:3817–3828. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2007.07.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Torr KM, Love KT, Simmons BA, Hill SJ. Structural features affecting the enzymatic digestibility of pine wood pretreated with ionic liquids. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2016;113:540–549. doi: 10.1002/bit.25831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu Z-H, Chen H-Z. Biomass–water interaction and its correlations with enzymatic hydrolysis of steam-exploded corn stover. ACS Sus. Chem. Eng. 2016;4:1274–1285. doi: 10.1021/acssuschemeng.5b01303. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pihlajaniemi V, et al. Weighing the factors behind enzymatic hydrolyzability of pretreated lignocellulose. Green Chem. 2016;18:1295–1305. doi: 10.1039/C5GC01861G. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gaur R, et al. Evaluation of recalcitrant features impacting enzymatic saccharification of diverse agricultural residues treated by steam explosion and dilute acid. RSC Adv. 2015;5:60754–60762. doi: 10.1039/C5RA12475A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Monschein M, Nidetzky B. Effect of pretreatment severity in continuous steam explosion on enzymatic conversion of wheat straw: Evidence from kinetic analysis of hydrolysis time courses. Biores. Technol. 2016;200:287–296. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2015.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bekiaris G, et al. Rapid estimation of sugar release from winter wheat straw during bioethanol production using FTIR-photoacoustic spectroscopy. Biotech. Biofuels. 2015;8 doi: 10.1186/s13068-015-0267-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hou S, Li L. Rapid characterization of woody biomass digestibility and chemical composition using near-infrared spectroscopy. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2011;53:166–175. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-7909.2010.01003.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.DeMartini JD, et al. Investigating plant cell wall components that affect biomass recalcitrance in poplar and switchgrass. Energy Environ. Sci. 2013;6 doi: 10.1039/c3ee23801f. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ralph J. Hydroxycinnamates in lignification. Phytochem. Rev. 2010;9:65–83. doi: 10.1007/s11101-009-9141-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lichtenthaler HK, Schweiger J. Cell wall bound ferulic acid, the major substance of the blue-green fluorescence emission of plants. J. Plant Physiol. 1998;152:272–282. doi: 10.1016/S0176-1617(98)80142-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dean JC, Walsh PS, Biswas B, Ramachandran PV, Zwier TS. Single-conformation UV and IR spectroscopy of model G-type lignin dilignols: the beta-O-4 and beta-beta linkages. Chem. Sci. 2014;5:1940–1955. doi: 10.1039/c3sc53260g. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Donaldson L, Radotić K, Kalauzi A, Djikanović D, Jeremić M. Quantification of compression wood severity in tracheids of Pinus radiata D. Don using confocal fluorescence imaging and spectral deconvolution. J. Struct. Biol. 2010;169:106–115. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2009.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Donaldson LA, Radotic K. Fluorescence lifetime imaging of lignin autofluorescence in normal and compression wood. J. Microsc. 2013;251:178–187. doi: 10.1111/jmi.12059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Billinton N, Knight AW. Seeing the wood through the trees: a review of techniques for distinguishing green fluorescent protein from endogenous autofluorescence. Anal. Biochem. 2001;291:175–197. doi: 10.1006/abio.2000.5006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Paës G. Fluorescent probes for exploring plant cell wall deconstruction: a review. Molecules. 2014;19:9380–9402. doi: 10.3390/molecules19079380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Auxenfans, T., Crônier, D., Chabbert, B. & Paës, G. Understanding the structural and chemical changes of plant biomass following steam explosion pretreatment. Biotech. Biofuels10 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Chandra RP, Arantes V, Saddler J. Steam pretreatment of agricultural residues facilitates hemicellulose recovery while enhancing enzyme accessibility to cellulose. Biores. Technol. 2015;185:302–307. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2015.02.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kirkland JJ. Quantitative application of potassium bromide disk technique in infrared spectroscopy. Anal. Chem. 1955;27:1537–1541. doi: 10.1021/ac60106a010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Radotic K, et al. Component analysis of the fluorescence spectra of a lignin model compound. J. Photochem. Photobiol. 2006;83:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2005.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Djikanović D, et al. Structural differences between lignin model polymers synthesized from various monomers. J. Polym. Environ. 2012;20:607–617. doi: 10.1007/s10924-012-0422-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xue Y, et al. Aggregation-induced emission: the origin of lignin fluorescence. Polymer Chemistry. 2016;7:3502–3508. doi: 10.1039/C6PY00244G. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Barakat A, Putaux JL, Saulnier L, Chabbert B, Cathala B. Characterization of arabinoxylan-dehydrogenation polymer (synthetic lignin polymer) nanoparticles. Biomacromolecules. 2007;8:1236–1245. doi: 10.1021/bm060885s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vaidya AA, Newman RH, Campion SH, Suckling ID. Strength of adsorption of polyethylene glycol on pretreated Pinus radiata wood and consequences for enzymatic saccharification. Biomass Bioener. 2014;70:339–346. doi: 10.1016/j.biombioe.2014.08.024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sipponen MH, Pihlajaniemi V, Littunen K, Pastinen O, Laakso S. Determination of surface-accessible acidic hydroxyls and surface area of lignin by cationic dye adsorption. Biores. Technol. 2014;169:80–87. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2014.06.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Berezin MY, Achilefu S. Fluorescence lifetime measurements and biological imaging. Chem. Rev. 2010;110:2641–2684. doi: 10.1021/cr900343z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Meineke, T., Manisseri, C. & Voigt, C. A. Phylogeny in defining model plants for lignocellulosic ethanol production: a comparative study of Brachypodium distachyon, wheat, maize, and Miscanthus x giganteus leaf and stem biomass. PLoS One9 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 43.Donaldson L. Softwood and hardwood lignin fluorescence spectra of wood cell walls in different mounting media. IAWA J. 2013;34:3–19. doi: 10.1163/22941932-00000002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sathitsuksanoh, N., Xu, B., Zhao, B. Y. & Zhang, Y. H. P. Overcoming biomass recalcitrance by combining genetically modified switchgrass and cellulose solvent-based lignocellulose pretreatment. PLoS One8 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 45.Cai Y, et al. Enhancing digestibility and ethanol yield of Populus wood via expression of an engineered monolignol 4-O-methyltransferase. Nat. Commun. 2016;7 doi: 10.1038/ncomms11989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Loqué D, Scheller HV, Pauly M. Engineering of plant cell walls for enhanced biofuel production. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2015;25:151–161. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2015.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mottiar Y, Vanholme R, Boerjan W, Ralph J, Mansfield SD. Designer lignins: harnessing the plasticity of lignification. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2016;37:190–200. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2015.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Overend RP, Chornet E, Gascoigne JA. Fractionation of lignocellulosics by steam-aqueous pretreatments. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. 1987;321:523–536. doi: 10.1098/rsta.1987.0029. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.