Although medicine has always been saturated with narrative knowledge, it is only over the past 40 years that there has been an increase in writing, research, and teaching about narrative medicine and narrative-based practices. Narrative medicine practices are bringing the power of story-based telling, appreciation, and analysis into the routines of scientific clinical work.1–9

Stirrings that first suggested medical stories would break free of the assumptions and techniques of clinical history-taking can be found in Sigmund Freud’s early case histories, notable for their storied qualities, the fiction of physician-writers such as Anton Chekhov and William Carlos Williams, the case writings of Alexander Luria, and the work of Edith and Michael Balint with London general practitioners in the 1950s. During the 1970s and 1980s, linguists and sociologists, including Elliot Mishler and his colleagues, pioneered efforts to study clinical conversations, discovering how disparate and in conflict were the “Voice of Medicine” and the “Voice of the Lifeworld”.10 Gradually, medical educators and practitioners borrowed some of the techniques and approaches of literary studies, history, philosophy, and other humanities disciplines to provide what medicine was lacking: a means to recognise and comprehend the singular and the particular in illness in addition to its pathological and psychological dimensions.

Humanities scholars and clinicians began to write and read medical discourse in new ways6 that took account of developing narratological ideas in medicine.1–4,7 They also began to study texts written by patients, caregivers, and creative writers,11 generating powerful frameworks for understanding the biographical, mental, and physical disruption brought about by illness. Today, patients, clinicians, and the culture at large are representing events and concerns of health and illness in diverse media—text, film, photography, fine arts, performance arts—and creating innovative ways to comprehend and convey their meanings.

Narrative medical practices and sensitivities help clinicians appreciate relational styles of thought and interaction in medicine that go beyond disease-framed, chronological history-taking.1,4,6,7–9 Scholars of the humanities, social scientists, and clinicians researching and using these approaches will converge at A Narrative Future for Healthcare conference at King’s College London, UK, on June 19–21 to sharpen and critique narrative concepts and methods in health care. Among the topics that will be explored at the conference are the narrative codes and techniques which shape clinical conversations, the marked proliferation in the past 20 years of life-writings emanating from health and social care situations, metaphors for illness and mental health, and the role of film and graphic novels in medical education.

Narrative medicine practices have coalesced from the intersection of literary studies, creative writing, disability studies, and narrative ethics with the health-care disci plines of nursing, social work, and medicine. The resultant practices are more able to elicit and work with stories of illness and fractured lifeworlds than they could in the past, and acknowledge the role of expressive storytelling and story-listening in medicine as forms of exploration, assimilation, and communication that promise better understanding and improvement of health care.

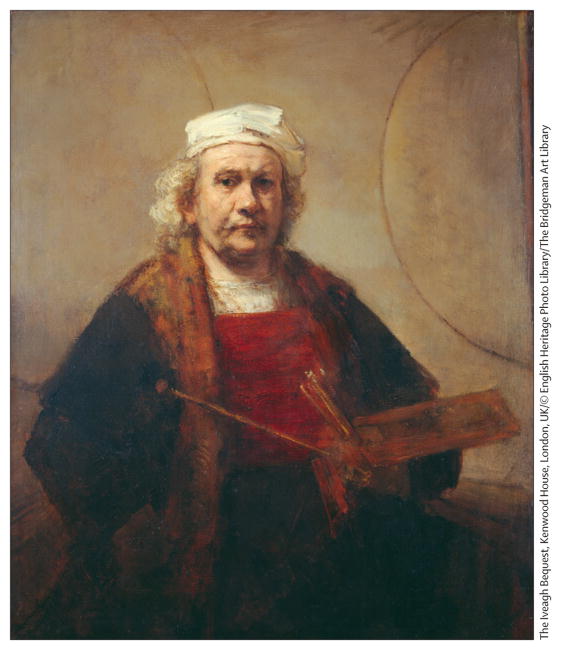

Self Portrait (c. 1665) (oil on canvas) by Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn (1606–69)

Acknowledgments

BH and RC are coorganisers of the conference A Narrative Future for Healthcare, which has received funding from a Wellcome Trust strategic award. BH has been the recipient of a grant from Novartis to set up seminars in literature and medicine and has been the recipient of a non-pharmaceutically related honorarium from GlaxoSmithKline. RC receives support from NIH grant R25 HL108014.

Contributor Information

Brian Hurwitz, Centre for the Humanities and Health, King’s College London, London WC2R 2LS, UK.

Rita Charon, Program in Narrative Medicine, College of Physicians and Surgeons, Columbia University, NY, NY, USA.

References

- 1.Charon R. Narrative medicine. New York: Oxford University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Greenhalgh P, Hurwitz B, editors. Narrative-based medicine: dialogue and discourse in clinical practice. London: BMJ Books; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hurwitz B. Narrative and the practice of medicine. Lancet. 2000;356:2086–89. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)03412-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Launer J. Narrative-based primary care. Abingdon: Radcliffe Medical Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brody H. Stories of sickness. New Haven: Yale University Press; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kleinman A. The illness narratives. New York: Basic Books; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hunter KM. Doctors’ stories: the narrative structure of medical knowledge. New Jersey: Princeton University Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Charon R, Trautmann Banks J, et al. Literature and medicine: contributions to clinical practice. Ann Intern Med. 1995;122:599–606. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-122-8-199504150-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hurwitz B, Skultans V, Greenhalgh P, editors. Narrative research in health and illness. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing BMJ Books; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mishler EG. The discourse of medicine: dialectics of medical interviewing. Norwood, NJ: Ablex Corp; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Frank A. The wounded storyteller: body illness and ethics. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]