Abstract

Background:

The current cross-sectional study was carried out to determine relationships between self-care and depression in patients with cancer.

Materials and Methods:

From October to December, 2015, 380 patients with cancer admitted to the associated university’s medical sciences hospitals (Sari, Iran), were entered into the study using non random sampling (accessible sampling). Data were collected by demographic questionnaire, Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) and a Self-care Questionnaire.

Results:

Males (48.4±13±39; CI95: 46.4-50.4) were older than females (45.3±18.4; CI95:42.8-47.9). Spearman correlation analysis results showed that there was a significant negative correlation between self-care and depression (r= -0.134, P<0.05) and also a significant inverse relationship between physical (r= -0.166, P=0.001), psychological (r= -0.207, P<0.001) and emotional self-care (r= -0.179, P<0.001) with depression.

Conclusions:

It appears that self-care measures such as training of physical exercises, promotion of physical self-care, holding counseling sessions and psychotherapy can reduce depression levels.

Keywords: Depression, cancer, pain, patients, Iran

Introduction

Cancer is a common disease which may be diagnosed in the advanced stages and after several side effects and may even cause death (Knight et al., 1997). Cancer is the second leading cause of death in most industrialized and developed countries, it also is one of the most dangerous and painful diseases today. According to statistics 10.8 people per 100 thousand people are diagnosed with the disease annually (Habek et al., 2004).

By 2002, the rate of the cancer patients was estimated to be 9-10 million people worldwide and statistics indicate the growth of this figure to 16 million until 2020 (Eheman et al., 2012). According to the World Health Organization`s (WHO) report, it is estimated that the number of deaths due to cancer in the United States of America (USA) increase to more than 800 thousand people and it is expected that this trend continues to be upward (Habek et al., 2004). In Iran, from 1986 to 2006 the number of cancer patients has increased 3.3 times (Mousavi et al., 2009).

Cancer reduces the ability of individuals to play a role and lead them to a feeling of lack of competence which reduces the confidence of the people and ultimately can cause psychological reactions such as depression, anxiety and stress (Noghani Fatemeh, 2006). Many studies have suggested that depression is one of the most common psychiatric disorders in patients with cancer (Hong and Tian, 2014; Walker et al., 2014; Wagner et al., 2017). Depression is very harmful in these patients because it causes patients to surrender in front of disease. In the other word, depressed people don’t fight with disease effectively and don’t attempt to live longer. Depression is more severe among people who are diagnosed with cancer than those who only suffer from depression (Breitbart, 1995).

Since 1960, many research groups have done studies to investigate depression in cancer patients (Hong and Tian, 2014; Walker et al., 2014; Li et al., 2016). According to various studies the prevalence of depression in advanced cancer patients have been reported to be between 1.5 % to 30 % (Arrieta et al., 2013; Currier and Nemeroff, 2014; Lie et al., 2015) which in a case study on 4,007 patients with cancer from 7 different countries this was stated to be 16.5 % (Mitchell et al., 2011). Consolidated data suggest that 24.6 % of cancer patients in the world suffer from at least one variety of classes of depression syndrome (Currier and Nemeroff, 2014).

One of the most effective ways to control the psychological effects of chronic diseases (including depression) is self-care (Ludman et al., 2004). Thus it can be stated that depression is one of the consequences of ignoring self-care, (Education; Gonzalez et al., 2008; Tung et al., 2013). As Orem defined, self-care includes all activities to protect the life, health and well-being (Weng et al., 2008). Self-care includes all activities to prevent, treat and cure diseases that improve the quality of life, patient satisfaction, and increase rehabilitation (Sajjadi et al., 2008; Krebber et al., 2014). Many of the studies stated that self-care significantly improves depressive symptoms (Gonzalez et al., 2008; Bagher-Nesami et al., 2016). While another study found no connection between improving depression and self-care practices such as exercise and diet (Franklin et al., 2011).

Given the urgency of this issue, the contradictions among studies and the lack of this study in Iranian patients with cancer (according to available database), further studies in order to investigate self-care and depression in cancer patients is needed. The current study was carried out to determine the relationship between self-care and depression in patients with cancer.

Materials and Methods

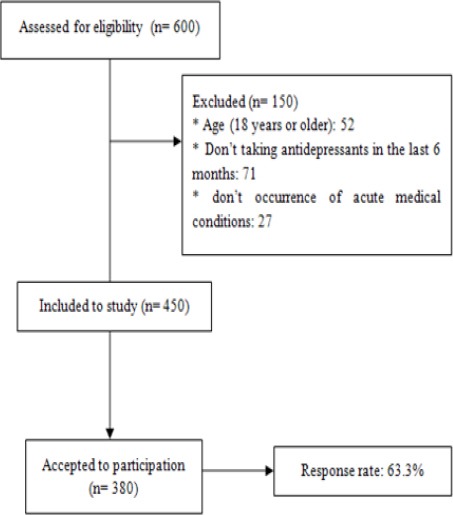

In this cross-sectional study (October to December, 2015) 380 cancer patients that were admitted to one of the associated university’s medical sciences hospitals (Sari, Iran) were entered to the study using non random sampling (accessible sampling). In this interval of four months, about 600 patients were admitted to the oncology ward of these hospitals. From these, 450 patients had the inclusion criteria’s (according to Diagram 1). 380 patients were accepted to participate in this study with the response rate of 63.3 %. The adequacy of the sample size was calculated to be 380 based on two-sided significant degree α=0.05 and test power of 80 (d=0.3) by G*power 3.0.10 software.

Diagram 1.

Inclusion Stages of Cancer Patients

Inclusion criteria included age (18 years or older), cancer treatment with radiation, chemotherapy or surgery, don’t taking antidepressants in the last 6 months, don’t transfer of patients to other hospitals and don’t occurrence of acute medical conditions (such as loss of consciousness).

After explaining the purpose of the study and how to complete the questionnaire, informed consent form was signed by qualified patients. Then the necessary explanation regarding the objectives of the study was given to patients and the questionnaires were distributed. Explanation was given to the patients if a question was vague. It should be noted this explanation was only in order to avoid ambiguity and without any kind of bias.

Data Collection tools

Data were collected by demographic questionnaire, Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) and Self-care questionnaire. Demographic questionnaire included items such as age, sex, education level, economic status, family history of cancer and stage of the cancer.

CES-D is a 20-option tool which is used to measure symptoms associated with depression that have been experienced in the past week (Vilagut et al., 2016). Each of the 20 options available in this instrument is measured using the Likert scale as follows: 0 = rarely or never (less than one day), 1 = occasionally or in few cases (1 to 2 days), 2 = occasionally or a moderate amount of time (3 to 4 days), 3 = most of the time or all the time (5 to 7 days) (Knight et al., 1997). Total scores range from 0 to 60. Knight and colleagues (1997) have reported reliability of these instruments to be 0.88 using Cronbach’s alpha (Knight et al., 1997). In this study, the reliability of the instrument was calculated to be 0.741 using Cronbach’s alpha on cancer patients.

Self-care Questionnaire (adapted from checklists published by the Ministry of Health) contained 34 parameters which included 4 overall scales of self-care (physical, psychological care, emotional and spiritual self-care) (Education). The scoring method was based on Likert from 1 to 5 (in this case, do not have a program, never, rarely, sometimes or always) (Bagher-Nesami et al., 2016). The scale scores range from 34 to 170 and a score of 34-67, 68-101, 102-135, 136-170 indicate poor, average, good and excellent level of self-care respectively. Bagheri Nesami, et al., (2015) have calculated its reliability to be 0.83 by evaluation of this tool in the elderlies. Also In another study the reliability of this instrument was calculated to be 0.841 by intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) (Bagher-Nesami et al., 2016). In this study, the reliability of this tool in cancer patients was calculated to be 0.792 by Cronbach’s alpha.

Statistical analysis

The statistical package for social sciences, version 20.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) were utilized for data analysis. First descriptive statistics for continuous variables were shown as means with standard deviation (SD) and n (%) for the categorical variables. Spearman’s correlations were used to probe the relationship between self-care and depression. Finally the predictors associating with depression were determined using Generalized Linear models (GLM). Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

Ethical considerations

This study was confirmed by the associated university’s medical sciences ethics committee (IR.MAZUMS.REC.95.S.105). Patients were informed about the goals and stages of the study so that their participation was voluntary. Patients passed the study`s stages in a quiet room. To ensure that a wide range of patients involved in the study, a trained researcher who was a member of the study provided the supplies. All patient information was undetectable by assigning a code to each patient.

Results

Demographic and illness characteristics of 380 patients with cancer are summarized in Table 1 and 2. Males (48.4±13.4; CI95:46.4-50.4) are older than females (45.3±18.4; CI95:42.8-47.9). The mean total score of depression and self-care were (24.14±5.4; CI95:23.6-24.7) and (131.7±12.5; CI95:130.5-132.98), respectively. 69.9 % of patients under treatment had higher depression in early stages of disease. The rate of depression in women (58.8%) and singles (86.6%) were higher than men and marrieds.

Table 1.

Demographic Profile of Participants (N=380)

| Characteristic | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 175 (46.1) |

| Female | 205 (53.9) |

| Economic Situation | |

| Weak | 110 (28.9) |

| Average | 204 (53.7) |

| Good | 66 (17.4) |

| Education | |

| Illiterate | 210 (55.3) |

| Diploma | 138 (36.3) |

| Bachelor of sciences | 22 (5.8) |

| Master of Science and above | 10 (2.6) |

| Marital | |

| Single | 51 (13.4) |

| Married | 329 (86.6) |

| Characteristic | Mean(SD) |

| Age | 46.7 (16.3) |

* Number of patients who had these diseases

Table 2.

Illness profile of participants (N=380)

| Characteristic | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Family history of cancer | |

| Yes | 112 (29.5) |

| No | 268 (70.5) |

| Depression | |

| Down | 261 (68.7) |

| Up | 119 (31.3) |

| Past medical history* | |

| Cardiac diseases | 46 (12.1) |

| Respiratory diseases | 34 (8.9) |

| Gastric diseases | 41 (10.8) |

| Urinary diseases | 26 (6.8) |

| History of cigarette smoking | |

| Yes | 71 (18.7) |

| No | 309 (81.3) |

| Cancer stage | |

| One | 132 (34.7) |

| Two | 133 (35.0) |

| Tree | 92 (24.2) |

| Four | 23 (6.1) |

| Characteristic | Mean (SD) |

| Self-Care | 131.7 (12.4) |

| Depression | 24.1 (5.4) |

Spearman correlation analysis results showed that there was a significant negative correlation between self-care and depression (r = -0.134, P<0.05) and also according to Table 3, there was a significant and inverse relationship between physical (r = -0.166, P=0.001), psychological (r= -0.207, P<0.001) and emotional self-care (r = -0.179, P<0.001) with depression.

Table 3.

Matrix Correlation between Sub-Scales of Self- Care and Depression (N=380)

| Physical Self-care | Psychological Self-care | Emotional Self-care | Spiritual Self-care | Depression | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical Self-care | Pearson Correlation | 1 | 0.194** | 0.464** | 0.275** | -0.166** |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.001 | ||

| Psychological Self-care | Pearson Correlation | 0.194** | 1 | 0.360** | 0.357** | -0.207** |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Emotional Self-care | Pearson Correlation | 0.464** | 0.360** | 1 | 0.374** | -0.179** |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Spiritual Self-care | Pearson Correlation | 0.275** | 0.357** | 0.374** | 1 | 0.005 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.927 | ||

| Depression | Pearson Correlation | -0.166** | -0.207** | -0.179** | 0.005 | 1 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.001 | 0 | 0 | 0.927 |

Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed).

According to the GLM presented in Table 4, a significant relationship was observed between depression and level of education (P<0.05), the economy (P<0.05), age (B= -0.068, P=0.004), sex (B=2.065, P<0.001), marital status (B=4.635, P<0.001) and the history of smoking (B= -2.486, P=0.001).

Table 4.

Predictors of Depression in Cancer Patients (N=380)

| Variable | B | SE | 95% CI | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Education | |||||

| Illiterate | 7.02 | 1.59 | 3.91 | 10.14 | 0.000b |

| Diploma | 6.24 | 1.52 | 3.26 | 9.21 | 0.000b |

| BS | 1.65 | 1.72 | -1.72 | 5.03 | 0.338 |

| MSc and upper | 0a | . | . | ||

| Economic Situation | |||||

| Weak | 1.18 | 0.78 | -0.36 | 2.71 | 0.133 |

| Average | -1.08 | 0.72 | -2.5 | 0.34 | 0.136 |

| Good | 0a | . | . | . | . |

| Cancer stage | |||||

| One | 9.07 | 1.18 | 8.39 | 13.03 | 0.000b |

| Two | 9.22 | 1.07 | 8.52 | 12.71 | 0.000b |

| Three | 6.89 | 1.18 | 5.81 | 10.44 | 0.000b |

| Four | 0a | . | . | . | . |

| Past medical history | |||||

| Cardiac diseases | 0.74 | 0.43 | -0.21 | 1.64 | 0.084 |

| Respiratory diseases | 0.81 | 0.52 | -0.12 | 1.96 | 0.092 |

| Gastric diseases | 0.91 | 0.51 | -0.19 | 2.27 | 0.076 |

| Urinary diseases | 0a | . | . | . | . |

| Age | -0.07 | 0.02 | -0.11 | -0.02 | 0.004b |

| Gender | 2.06 | 0.60 | 0.88 | 3.25 | 0.001b |

| Marital | 4.64 | 0.94 | 2.79 | 6.48 | 0.000b |

| History of cigarette smoking | -2.49 | 0.72 | -3.91 | -1.06 | 0.001b |

| Family history of cancer | -0.35 | 0.57 | -1.47 | 0.76 | 0.537 |

a, Set to zero because this parameter is redundant; b, Statistically significant at p ≤ 0.05

Discussion

This study aimed to determine the relationship between self-care and depression in patients with cancer. The results showed a significant negative correlation between self-care and depression in cancer patients. In line with the findings of the present study, Park, et al. (2004) in their study on diabetic patients, and Weng, et al., (2008) on a study on renal transplant patients found a significant negative relationship between depression and self-care. Findings of Sajjadinia and colleagues (2008) on dialysis patients showed that prevalence of depression is lower in patients with high levels of self-care than others. Fear of death, lack of awareness of treatment, changes in the body of the patient during chemotherapy and radiotherapy, economic problems and also provides the necessary conditions for the existence of psychological problems such as depression in patients with cancer (Krebber et al., 2014). Therefore, practicing self-care programs (both physical and psychological) causes significant reduction of symptoms of depression in people who, according to their particular circumstances are vulnerable to psychological problems.

Exercise is one of physical self-care programs and in recent years it has been proved that exercise is a useful method for reducing mental illnesses such as depression (Franklin et al., 2011). Their results showed that physical activity reduces stress on patients and increase their self-esteem (Ho, 2005). The study of Ebadinejad and colleagues (2015) also showed that doing exercise significantly decreases depression in children with cancer. These findings are consistent with the results of this study, which showed significant and negative relationship between physical self-care and depression in patients with cancer. Daily exercising and group activities can be brought vitality to patients which is effective on the treatment of depression. As Jeong, et al., (2005) showed that body movements with music affect the secretion of serotonin and dopamine and these two as chemical mediators, decrease depression in adolescents with depression.

Another important result of this study was the relationship between depression and psychological self-care. Psychological self-care consists of taking all necessary measures to reduce stress and mental tension including attending group psychotherapy, psychological counseling sessions with a psychiatrist and a psychologist, looking at life from the perspective of concept therapy, reduction of the stress resulting from the sufferings of life and finding an appropriate method for having a pleasant life in the current situation (Mercer et al., 2012; Chiang et al., 2015).

The present study showed that depression and emotional self-care had significant and negative relationships in patients with cancer. Most patients with cancer suffer from psychological problems caused by the disease, such as chemotherapy and bone marrow transplantation that these problems can be controlled with emotional self-care. Self-efficacy practices are among the effective programs in emotional self-care (Maeda et al., 2013). Oh and colleagues (1997) showed that after practicing self-efficacy exercises the amount of self-care and life expectancy has increased significantly in patients with cancer Which results in lower rates of depression in these patients.

According to present findings, spiritual self-care and religious affiliation was not a good predictor for determining depression in patients. In line with these findings, the study of Murphy et al., (2000) also concluded that there wasn’t a clear link between these two variables. Also Braam, et al., (1996) stated that it seems there is no clear connection between religious affiliation and severity of depression in the patient population. But, in a study on elderly people resided in cancer homes, patients with cardiac disorders and healthy ones a significant relationship between religiosity and depression has been reported (Musick et al., 1998; Eliassen et al., 2005; Koenig, 2007). Possible causes of this paradox can be the difference in population, age range and cultural differences of the participants.

Limitations of the study

The most important limitation of this study was no access to patients in other hospitals in the province and the country which makes not generalize the results due to small sample size, also cultural differences of patients which was not controllable in this study. Impatience and imprecision of some of the patients at the completion of questionnaires due to disease-related treatment affects the results. Therefore, it is suggested that because of the importance of this issue in the future, these studies be carried out more frequently and with greater breadth on cancer patients.

Application of the results

Depression as a consequence of cancer should be one of the nursing diagnoses in care centers. Given the prevalence of depression in these patients, putting psychotherapy sessions for early detection of depression and if necessary starting therapy sessions and using antidepressants is necessary. Also, considering the significant effect of self-care programs on depression, it is anticipated that with the necessary training of aspects of self-care (e.g., physical and psychological) for these patients, one can have beneficial effects on their mental health.

According to the results, the negative correlation between self-care and depression was significant. Also physical, psychological and emotional self-care were significantly and inversely associated with depression. There was a significant relationship between depression and demographic variables such as education level, economic status, age and sex. So it seems that self-care measures such as training of physical exercises, promotion of physical self-care, holding counseling sessions and psychotherapy can reduce depression levels.

References

- Arrieta Ó, Angulo LP, Núñez-Valencia C, et al. Association of Depression and Anxiety on Quality of Life, Treatment Adherence, and Prognosis in Patients with Advanced Non-small Cell Lung Cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20:1941–1941. doi: 10.1245/s10434-012-2793-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagher-Nesami M, Goudarzian AH, Mirani H, et al. Association Between Self-care Behaviors and Self-esteem of Rural Elderlies;Necessity of Health Promotion. Mater Sociomed. 2016;28:41–41. doi: 10.5455/msm.2016.28.41-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagheri Nesami M, Goudarzian AH, Ardeshiri M, et al. Self-care behavior and its related factors in the community-dwelling elderlies in Sari, 2014. J Clin Nurs. 2015;4:48–48. [Google Scholar]

- Braam AW, Beekman ATF, van Tilburg TG, et al. Religious involvement and depression in older Dutch citizens. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1997;32:284–284. doi: 10.1007/BF00789041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breitbart W. Identifying patients at risk for, and treatment of major psychiatric complications of cancer. Support Care Cancer. 1995;3:45–45. doi: 10.1007/BF00343921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiang YZ, Bundy C, Griffiths CEM, et al. The role of beliefs:lessons from a pilot study on illness perception, psychological distress and quality of life in patients with primary cicatricial alopecia. Br J Dermatol. 2015;172:130–130. doi: 10.1111/bjd.13259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Currier MB, Nemeroff CB. Depression as a risk factor for cancer:from pathophysiological advances to treatment implications. Annu Rev Med. 2014;65:203–21. doi: 10.1146/annurev-med-061212-171507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebadinejad Z, Rassouli M, Payandeh A, et al. The Effect of aerobics on mild depression in Children with Cancer. Medsurg Nurs. 2015;4:35–35. [Google Scholar]

- Education MoHaM. Health Education & Promotion Dept [Online] Available: http://iec.behdasht.gov.ir/index.aspx?fkeyid=&siteid=143&pageid=52912&p=2 .

- Eheman C, Henley SJ, Ballard-Barbash R, et al. Annual Report to the Nation on the status of cancer, 1975-2008, featuring cancers associated with excess weight and lack of sufficient physical activity. Cancer. 2012;118:2338–2338. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eliassen AH, Taylor J, Lloyd DA. Subjective religiosity and depression in the transition to adulthood. J Sci Study Relig. 2005;44:187–187. [Google Scholar]

- Franklin BA, Trivax JE, Vanhecke TE Exercise and Depression. In ‘Psychiatry and Heart Disease’. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2011. pp. 211–22. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez JS, Peyrot M, McCarl LA, et al. Depression and diabetes treatment nonadherence:a meta-analysis. Diabetes Care. 2008;31:2398–2398. doi: 10.2337/dc08-1341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Habek D, Cerkez JH, Galić J, et al. Acute abdomen as first symptom of acute Leukemia. 2004;3 doi: 10.1007/s00404-002-0453-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho RTH. Effects of dance movement therapy on Chinese cancer patients:A pilot study in Hong Kong. Arts Psychother. 2005;32:337–337. [Google Scholar]

- Hong JS, Tian J. Prevalence of anxiety and depression and their risk factors in Chinese cancer patients. Support Care Cancer. 2014;22:453–453. doi: 10.1007/s00520-013-1997-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong YJ, Hong SC, Lee MS, et al. Dance movement therapy improves emotional responses and modulates neurohormones in adolescents with mild depression. Int J Neurosci. 2005;115:1711–1711. doi: 10.1080/00207450590958574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight RG, Williams S, McGee R, et al. Psychometric properties of the Centre for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) in a sample of women in middle life. Behav Res Ther. 1997;35:373–373. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(96)00107-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenig HG. Religion and remission of depression in medical inpatients with heart failure/pulmonary disease. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2007;195:389–389. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e31802f58e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krebber AMH, Buffart LM, Kleijn G, et al. Prevalence of depression in cancer patients:a meta-analysis of diagnostic interviews and self-report instruments. Psychooncology. 2014;23:121–121. doi: 10.1002/pon.3409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M, Kennedy EB, Byrne N, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of collaborative care interventions for depression in patients with cancer. Psychooncology. 2016 doi: 10.1002/pon.4286. doi:10.1002/pon.4286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lie HC, Hjermstad MJ, Fayers P, et al. Depression in advanced cancer;Assessment challenges and associations with disease load. J Affect Disord. 2015;173:176–176. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2014.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludman EJ, Katon W, Russo J, et al. Depression and diabetes symptom burden. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2004;26:430–430. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2004.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeda U, Shen B-J, Schwarz ER, et al. Self-efficacy mediates the associations of social support and depression with treatment adherence in heart failure patients. International J Behav Med. 2013;20:88–88. doi: 10.1007/s12529-011-9215-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mercer SW, Gunn J, Bower P, et al. Managing patients with mental and physical multimorbidity. BMJ. 2012;345:e5559. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e5559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell AJ, Chan M, Bhatti H, et al. Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and adjustment disorder in oncological, haematological, and palliative-care settings:a meta-analysis of 94 interview-based studies. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12:160–160. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70002-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mousavi SM, Gouya MM, Ramazani R, et al. Cancer incidence and mortality in Iran. Ann Oncol. 2009;20:556–556. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdn642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy PE, Ciarrocchi JW, Piedmont RL, et al. The relation of religious belief and practices, depression, and hopelessness in persons with clinical depression. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2000;68:1102–1102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musick MA, Koenig HG, Hays JC, et al. Religious Activity and Depression among Community-Dwelling Elderly Persons with Cancer:The Moderating Effect of Race. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 1998;53:218–218. doi: 10.1093/geronb/53b.4.s218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noghani FMZ, Bohrani N, Ghodarti V. The comparison of self esteem between male and female cancer patients. HAYAT. 2006;12:33–33. [Google Scholar]

- Oh PJ, Lee EO, Tae YS, et al. Effects of a program to Promote self-efficacy and hope on the self:Care behaviors and the quality of life in patients with leukemia. J Nurs Acad Soc. 1997;27:627–627. [Google Scholar]

- Park H, Hong Y, Lee H, et al. Individuals with type 2 diabetes and depressive symptoms exhibited lower adherence with self-care. J Clin Epidemiol. 2004;57:978–978. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2004.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sajjadi M, Akbari A, Kianmehr M, et al. The relationship between self-care and depression in patients undergoing hemodialysis. Quarterly of Horizon of Med Sci. 2008;14:13–13. [Google Scholar]

- Tung HH, Lin CY, Chen KY, et al. Self-management intervention to improve self-care and quality of life in heart failure patients. Congest Heart Fail. 2013;19:9–9. doi: 10.1111/chf.12014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vilagut G, Forero CG, Barbaglia G, et al. Screening for depression in the general population with the center for epidemiologic studies depression (CES-D):A systematic review with meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0155431. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0155431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner LI, Pugh SL, Small W, et al. Screening for depression in cancer patients receiving radiotherapy:Feasibility and identification of effective tools in the NRG Oncology RTOG 0841 trial. Cancer. 2017;123:485–485. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker J, Sawhney A, Hansen CH, et al. Treatment of depression in adults with cancer:a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Psychol Med. 2014;44:897–897. doi: 10.1017/S0033291713001372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weng LC, Dai YT, Wang YW, et al. Effects of self-efficacy, self-care behaviours on depressive symptom of Taiwanese kidney transplant recipients. J Clin Nurs. 2008;17:1786–1786. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2007.02035.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]