Abstract

Objective

To assess women’s preferences for contraception after delivery, and to compare use with preferences.

Methods

In a prospective cohort study of women aged 18–44 years who wanted to delay childbearing for at least 2 years, we interviewed 1,700 participants from eight hospitals in Texas immediately postpartum and at 3 and 6 months after delivery. At 3 months, we assessed contraceptive preferences by asking what method women would like to be using at 6 months. We modeled preference for highly effective contraception and use given preference according to childbearing intentions using mixed-effects logistic regression, testing for variability across hospitals and differences between those with and without immediate postpartum long-acting reversible contraception (LARC) provision.

Results

Approximately 80% completed both the 3 and 6-month interviews (1367/1700). Overall, preferences exceeded use for both LARC: 40.8% [n=547] vs. 21.9% [n=293] and sterilization: 36.1% [n=484] vs. 17.5% [n=235]. In the mixed-effects logistic regression models, several demographic variables were associated with a preference for LARC among women who wanted more children, but there was no significant variability across hospitals. For women who wanted more children and had a LARC preference, use of LARC was higher in the hospital that offered immediate postpartum provision (p<0.035), as it was for US-born women (OR 2.08, 95% CI 1.17–3.69) and women with public prenatal care providers (OR 2.04, 95% CI 1.13–3.69). In the models for those who wanted no more children, there was no significant variability in preferences for long-acting or permanent methods across hospitals. However, use given preference varied across hospitals (P<0.001) and was lower for Black women (OR 0.26, 95% CI 0.12–0.55), and higher for US-born women (OR 2.32, 95% CI 1.36–3.96), those over 30 (OR 1.82, 95% CI 1.07–3.09), and those with public prenatal care providers (OR 2.04, 95% CI 1.18–3.51).

Conclusion

Limited use of long-acting and permanent contraceptive methods after delivery is associated with indicators of provider and system-level barriers. Expansion of immediate postpartum LARC provision as well as contraceptive coverage for undocumented women could reduce the gap between preference and use.

INTRODUCTION

In the United States, about half of postpartum women use the least effective methods of contraception, including condoms and withdrawal, or no method at all.(1) This frequently results in interpregnancy intervals less than 18 months and high rates of unintended pregnancy, which are associated with adverse birth outcomes.(2,3) In contrast, little use is made of long-acting reversible contraception (LARC) in the postpartum period. Not only are very few implants and IUDs placed immediately postpartum, but use of these methods remains limited in the 6 months after delivery.(1,4) This limited use of LARC may be due to provider and health system-level barriers rather than to lack of demand.(4–10) If so, immediate postpartum provision of LARC could increase use.(3,11)

Although there is substantial use of female sterilization after delivery, with most procedures occurring immediately postpartum, there are indications of barriers even for this widely used permanent method. Among the barriers for women with public insurance coverage during pregnancy, such as Medicaid and CHIP, are the Medicaid consent form and the requirement that it be completed 30 days prior to the procedure, insufficient reimbursement for hospitals and providers, arbitrary assumptions about who is an appropriate candidate for sterilization, availability of an operating room, and lack of insurance coverage for contraception. (12–18)

In this study, we assess the types of contraception women would prefer to be using after delivery, as well as the factors associated with use of LARC or sterilization among women with a preference for these methods. We focus on publicly insured women in Texas, a state in which funding for family planning has become substantially more restricted since 2011, and where previous studies have found restricted access to more expensive, longer-term methods.(14,20,21)

MATERIALS AND METHODS

For this prospective study, participants were recruited after delivery from 8 hospitals across 6 cities. We aimed to enroll 100 participants from a hospital in Odessa, 300 from each hospital selected in Austin, Edinburg, and Dallas, 400 from 2 hospitals in Houston, and 300 from 2 hospitals in El Paso for a total sample of 1700 women. The hospitals were chosen to reflect the experiences of women delivering with public insurance at larger hospitals in Texas’ urban centers. Two hospitals that we initially approached declined to participate, and were replaced with hospitals from the same city. The 3 hospitals in Austin and El Paso were included in a precursor to this study.(20,21) Five of the eight hospitals were formally connected with an academic department. One hospital, “Hospital 8”, was the only facility in our study that had implemented immediate postpartum placement of IUDs and implants at the time we recruited participants. The initial sample size was chosen so as to have 90 percent power (alpha = 0.05, two-sided) to test for differences of .20 or more in the proportion of women obtaining their preferred method across sites.

Eligible participants were between 18 and 44 years old, spoke English or Spanish, had delivered a single, healthy baby whom they expected to go home with them upon discharge, wanted to delay childbearing for at least two years, lived in Texas within the hospital’s catchment area, and planned to live in the area for at least one year. All participants had their births covered by public insurance or had no insurance. After obtaining signed informed consent from participants, we administered a 20-minute face-to-face baseline interview in either English or Spanish.

Baseline interviews took place between October, 2014 and April, 2016. Follow-up interviews were conducted by phone at 3 and 6 months after delivery. Three-month interviews were completed in August 2016, and 6-month interviews were completed in November 2016. Twelve-, 18-, and 24-month follow-up interviews are in progress. Participants were offered $30 compensation for the baseline interview at recruitment and $15 for each subsequent interview by phone for a total of $105 for all completed interviews. One hospital limited compensation for the baseline interview to $15.

The baseline questionnaire collected information on demographic and socioeconomic variables including age, parity, relationship status, race or ethnicity, education, insurance status (public or none), and nativity (U.S. born or foreign-born). We classified the location of women’s prenatal care into private practice vs publicly funded clinics; we included women who received prenatal care in Mexico or who had no prenatal care with women obtaining care at public clinics due to the small sample (<2%) in these groups.

Insurance status, future childbearing intentions, and contraceptive use were assessed at baseline and in each of the follow-up interviews. Women’s childbearing intentions were assessed using the question “Do you plan to have more children in the future?”

To capture actual use at each interview, we asked women what method of contraception they were currently using. To capture methods that women may not have considered birth control, we also asked women if they were using less effective methods, such as condoms or withdrawal, whether they were abstinent, or whether their partners were using any methods. The very small number of women who stated that they were using 2 methods together were classified as using the more effective method.

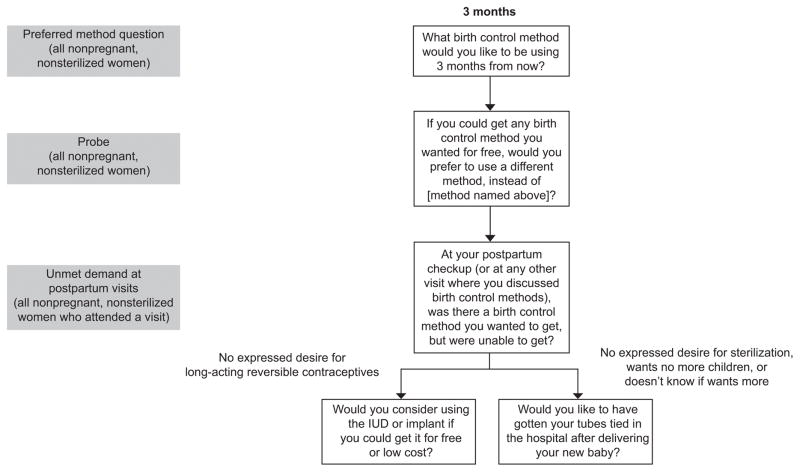

To assess participants’ contraceptive preferences during the 3-month interview, we asked women their preferred method directly and then asked a series of prompts (Figure 1). We began by asking all non-sterilized participants what method they would like to be using by the time their baby turned 6 months old. We chose 6 months since by that time most women have resumed sexual relations, and will no longer be relying on exclusive breastfeeding as contraception. Next, we asked women what method they would like to be using at 6 months if they could get any method for free. We paid specific attention to preferences for LARC, vasectomy, or female sterilization because prior research has demonstrated many women prefer to be using these methods postpartum but are not using them due to a range of barriers not associated with other methods such as a high upfront cost and method availability at hospitals and health care practices.(6,21,22) Among women who attended a postpartum visit, we asked if there was a method they wanted to get at their postpartum visits that they were unable to get. Then, following a previous study, (20) we asked women who had not previously mentioned an interest in LARC whether they would consider using an IUD or implant if it were free. Finally, to ensure a preference for sterilization was fully captured, women who had not previously expressed a desire for tubal ligation and who did not want any more children or did not know if they wanted more children in the future were asked “Would you like to have had a tubal ligation in the hospital right after you had your new baby?” (14)

Figure 1.

Survey questions used to measure contraceptive preferences. IUD, intrauterine device.

We distinguished between a participant’s preferred contraceptive method measured directly (“unprompted”), and a method mentioned in response to any of the method preference prompts, terming the latter an “elicited preference”. We then classified both the unprompted preference and the elicited preference according to method efficacy and reversibility. The lowest method category, which we term less effective methods, includes condoms, withdrawal, spermicides, sponges, fertility-based awareness methods (including the rhythm method), and abstinence. The next category, which we term “hormonal methods” includes combined and progestin-only contraceptive pills, injectables, the vaginal ring, and the patch. The third group, LARC, includes the implant, copper IUD, and the levenorgestrel releasing intrauterine system. We also distinguished a fourth group for permanent methods: female sterilization and vasectomy. If a participant answered different methods to the series of preference prompts, her elicited preference was categorized based on the most effective or permanent method mentioned. Women who had obtained a tubal ligation, or whose partners or spouses had obtained a vasectomy were classified as having a preference for a permanent method.

We examined the distribution of the sample by hospital and socio-demographic characteristics (age group, parity, educational attainment, race/ethnicity, and nativity), type of prenatal care provider, insurance status, and relationship status. We also reviewed retention rates by hospital and socio-demographic characteristics. Then, using the same four-tier categorization used for method preferences, we examined use of contraception by method at each interview up to 6 months after delivery, contrasting the experience of participants recruited at Hospital 8 that offered immediate postpartum LARC with all other hospitals. Then, at 6 months after delivery, we compared the percentages of participants using methods in each category with the percentage stating an unprompted preference for a method in that category, as well as the percentage stating an elicited preference for a method in that category. Next, we examined the methods actually being used by women who had expressed a preference for a highly effective method, distinguishing between women who wanted more children and those who did not plan to have another child.

The remaining analysis focused on the factors associated with preference for highly effective methods, and with the likelihood of actually using these methods among women who expressed a preference for them. We were interested in how both preferences and use among those with a preference might vary according to social and demographic factors, as well as by the hospital at which the participant was recruited. We conducted separate analyses for women who did and did not want more children since the former might be less interested in using a highly effective method after delivery.

For women who wanted more children or were unsure of their intentions, we modeled two dichotomous outcomes. The first was a preference (either elicited or unprompted) for LARC at the 3-month interview, while the second was use of LARC at the 6-month interview among women who expressed a preference for LARC. For women who wanted no more children, the two corresponding outcomes were a preference for either a long-acting or a permanent method at the 3-month interview, and use of LARC or sterilization at the 6-month interview among women who expressed a preference for either type of method.

In all four regressions, we used mixed-effects logit models to estimate fixed effects (odds ratios) associated with socio-demographic characteristics, type of prenatal care provider, and insurance and relationship status, as well as random effects for each hospital. Mixed-effects models can account for the potential association of outcomes of women in the same hospital through the hospital-level random effects. The extent to which this variation is statistically greater than 0 was tested using likelihood-ratio chi-square tests comparing the mixed model to a standard logit model with a threshold p-value of 0.05. Empirical Bayes estimates of hospital random effects were used to quantify the expected log odds of hospital-specific outcomes. To assess the role of immediate postpartum provision of LARC, we carried out tests of difference that contrasted the average of the Emprical Bayes estimates from hospitals 1 through 7 with those of hospital 8. Stata 14’s –melogit- mixed-effects logit model routine was used for estimation and –nlcom- was used for testing contrasts.

Human subjects approval for this study was obtained from the Institutional Review Boards of the University of Texas at Austin, Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center El Paso, Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center Lubbock, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, and Las Palmas Del Sol Healthcare.

RESULTS

A total of 1,700 participants met the inclusion criteria and were enrolled in the study. There were 125 women who were eligible but did not consent to participate. A large proportion of this sample is Hispanic (81%), and nearly half of women are foreign-born (46%) (Table 1). Less than half (39%) received prenatal care at a private practice, and many (77%) had no insurance by six months after delivery. A similar percentage of women reported that they wanted more children after their delivery (44%) and reported that they did not want more (48%).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study population and the proportion of baseline sample completing 3 & 6 month interviews

| Characteristic | Distribution of Sample (n=1700) n (%) |

Percent completing both 3 & 6 month interviews (n=1367) | P+ |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hospital | <0.001 | ||

| 1 | 300 (17.7) | 88.0 | |

| 2 | 217 (12.8) | 75.6 | |

| 3 | 83 (4.9) | 85.5 | |

| 4 | 301 (17.7) | 76.7 | |

| 5 | 100 (5.9) | 67.0 | |

| 6 | 300 (17.7) | 77.7 | |

| 7 | 200 (11.8) | 82.0 | |

| 8 | 199 (11.7) | 86.9 | |

| Age | 0.002 | ||

| 18–24 | 776 (45.7) | 76.8 | |

| 25–29 | 454 (26.7) | 82.4 | |

| 30+ | 470 (27.7) | 84.5 | |

| Parity | 0.047 | ||

| 1 | 445 (26.2) | 76.9 | |

| 2 | 541 (31.8) | 80.2 | |

| 3+ | 714 (42.0) | 82.8 | |

| Education | 0.505 | ||

| <High school | 599 (35.1) | 79.5 | |

| High school | 677 (39.8) | 80.1 | |

| >High school | 424 (24.9) | 82.3 | |

| Race or ethnicity | 0.615 | ||

| Hispanic | 1374 (80.8) | 80.1 | |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 226 (13.3) | 81.0 | |

| White, Other, or Multi-race | 100 (5.9) | 84.0 | |

| Nativity | 0.001 | ||

| U.S. | 914 (53.8) | 77.5 | |

| Foreign | 786 (46.2) | 83.8 | |

| Prenatal care provider | 0.790 | ||

| Private (US) | 663 (39.0) | 80.1 | |

| Public (US), Private or Public (MX), None | 1037 (61.0) | 80.6 | |

| Insurance status at 6 months* | |||

| Insured | 318 (23.3) | - | |

| Uninsured | 1049 (76.7) | - | |

| Relationship status at 6 months* | |||

| Married | 461 (33.7) | - | |

| Cohabitating | 526 (38.5) | - | |

| Single | 380 (27.8) | - | |

| Childbearing intentions at 6 months* | |||

| Want more children | 601 (44.0) | - | |

| Want no more children | 652 (47.7) | - | |

| Don’t know | 114 (8.3) | - | |

| Total | 1700 | 80.4 | |

Includes 1,367 who completed the 3 & 6 month interview

For difference in follow-up across categories

Overall, retention at 6 months after delivery was 80% with 1,373 participants completing both the 3 and 6-month follow-up interviews. Retention varied across hospitals from 67% to 88%. Retention was also higher among older, higher parity, and foreign-born participants.

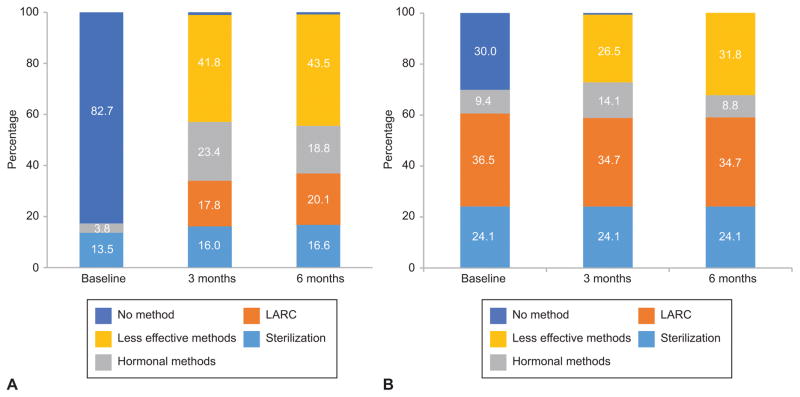

There is a large and significant difference (p < 0.001) in the distribution of method use between Hospital 8 and all other hospitals at baseline, 3 and 6 months after delivery (Figure 2). In Hospital 8, that provided immediate postpartum LARC, 36% of participants took advantage of this option, and LARC use remained near that level during the next six months after delivery. Use of sterilization and hormonal methods also varied little across the 3 interviews. Among women recruited at the other hospitals, contraceptive use increased from 17% at baseline to nearly 100% at the 3-month interview, but changed little between the 3-month and the 6-month interviews. Additionally, a much smaller percentage were using LARC at 3 months and 6 months compared with Hospital 8, and a higher percentage were using hormonal and less-effective methods.

Figure 2.

Contraceptive use at various durations postpartum. Percent of women using sterilization, long-acting reversible contraceptives (LARC), hormonal methods, less-effective methods, and no method at baseline, 3 months, and 6 months postpartum among women at all hospitals except Hospital 8 (A) and among women at Hospital 8 (B).

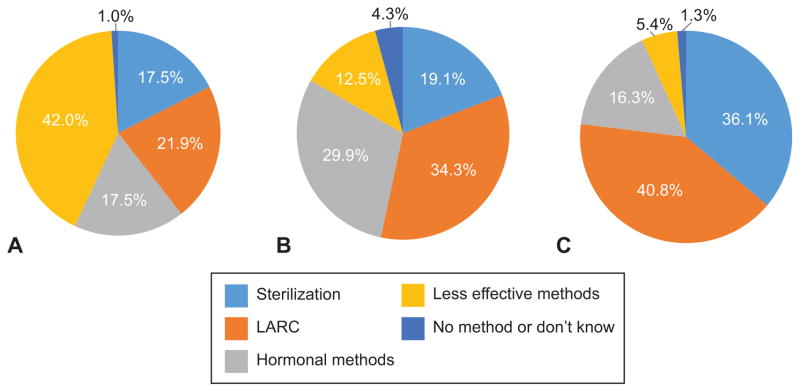

The unprompted preference for both LARC and hormonal methods was substantially greater than actual use (Figure 3). Including women’s responses to prompts regarding LARC and sterilization (elicited preference) resulted in nearly a doubling of preference for permanent methods and a widening of the discrepancy between preferences and use.

Figure 3.

Contraceptive use and method preference at 6 months postpartum. Type of contraceptive method used (A), method preference (B), and elicited method preference (C) at 6 months postpartum. LARC, long-acting reversible contraceptives.

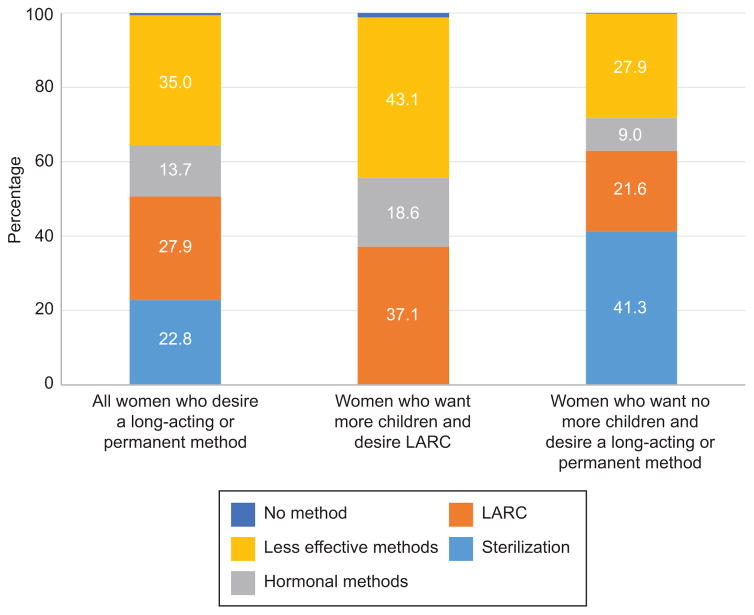

Among all women who had an elicited preference for a long-acting or permanent method at the 3–month interview, more than a third were using a less effective method such as condoms or withdrawal at 6 months, and about one sixth were using hormonal methods (Figure 4). The percentages using less effective or hormonal methods among women who wanted more children were even greater.

Figure 4.

Methods being used at 6 months postpartum among all women who desire a long-acting or permanent method, women who want more children (or are unsure) and desire long-acting reversible contraceptives (LARC), and women who want no more children and desire a long-acting or permanent method.

In the multivariable model of elicited preference for LARC among women who wanted more children or were unsure, there were no significant differences across hospital of recruitment (Table 2). Women age 30 and over were less likely to prefer LARC than younger women, and Non-Hispanic Blacks and Whites were less likely to prefer LARC compared to Hispanics. Also, participants who had a public prenatal care provider were more likely to prefer LARC than those with a private provider, while cohabiting women were more likely to prefer LARC than married women.

Table 2.

Odds ratios (95% CIs) for contraceptive preferences and use by desire for additional children†

| Covariate | Models for Women Who Want More Children or are Unsure | Models for Women Who Do Not Want More Children | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preference for LARC at 3 mos. (n=702) | LARC use at 6 mos. given preference at 3 mos. (n=420) | Preference for long-acting or permanent method at 3 mos. (n=638) | Use of long-acting or permanent method given preference at 3 mos. (n=569) | |||||

|

| ||||||||

| Age in years | ||||||||

| 18–24 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| 25–29 | 1.03 | (0.69, 1.54) | 0.89 | 0.52, 1.51 | 1.14 | 0.53, 2.47 | 1.46 | 0.85, 2.50 |

| 30+ | 0.46 | (0.27, 0.79) | 1.51 | 0.69, 3.31 | 0.65 | 0.31, 1.35 | 1.82 | 1.07, 3.09 |

| Parity | ||||||||

| 1 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| 2 | 1.22 | 0.84, 1.77 | 1.19 | 0.73, 1.95 | 2.77 | 1.13, 6.79 | 1.27 | 0.53, 3.07 |

| 3+ | 1.10 | 0.68, 1.77 | 1.00 | 0.51, 1.95 | 4.56 | 1.87, 11.13 | 1.86 | 0.79, 4.43 |

| Education | ||||||||

| <High school | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| High school | 1.17 | 0.78, 1.74 | 0.86 | 0.51, 1.44 | 1.02 | 0.54, 1.92 | 0.91 | 0.58, 1.44 |

| >High school | 1.31 | 0.82, 2.07 | 1.21 | 0.65, 2.23 | 1.31 | 0.61, 2.82 | 1.55 | 0.90, 2.69 |

| Race or ethnicity | ||||||||

| Hispanic Black or White | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Non-Hispanic Black | 0.39 | 0.23, 0.66 | 0.97 | 0.44, 2.14 | 0.86 | 0.35, 2.10 | 0.26 | 0.12, 0.55 |

| White & Other | 0.45 | 0.23, 0.89 | 0.59 | 0.21, 1.67 | 2.50 | 0.54, 11.63 | 0.52 | 0.22, 1.24 |

| Nativity | ||||||||

| Foreign | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| U.S. | 1.10 | 0.71, 1.70 | 2.08 | 1.17, 3.69 | 0.78 | 0.38, 1.64 | 2.32 | 1.36, 3.96 |

| Prenatal Care Provider | ||||||||

| Private | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Public (US), Mexico, None | 1.76 | 1.18, 2.63 | 2.04 | 1.13, 3.69 | 0.97 | 0.49, 1.89 | 2.04 | 1.18, 3.51 |

| Insurance status at 6 months | ||||||||

| Insured | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Uninsured | 1.43 | 0.98, 2.10 | 0.73 | 0.43, 1.24 | 0.98 | 0.48, 1.98 | 0.72 | 0.43, 1.22 |

| Relationship status at 6 months | ||||||||

| Married | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Cohabitating | 1.70 | 1.17, 2.47 | 0.94 | 0.56, 1.56 | 0.80 | 0.43, 1.51 | 1.23 | 0.77, 1.95 |

| Single | 1.54 | 0.99, 2.39 | 0.77 | 0.42, 1.41 | 1.10 | 0.55, 2.22 | 0.94 | 0.58, 1.53 |

| Tests of Random Effects | ||||||||

| Likelihood ratio test of mixed effects model vs. logistic model (p-values) | 0.484 | 0.005 | 0.161 | <0.001 | ||||

| Hospital 8 vs. all other hospitals (p-values) | – | 0.033 | – | 0.063 | ||||

Odds ratios were estimated for mixed effects logistic regression models.

Bold indicates significance at the 95% confidence level.

Numbers are odds ratios followed by 95% confidence intervals.

The multivariable model for use of LARC at 6 months among women with a preference for these methods demonstrated a significant difference across hospital of recruitment; women recruited at Hospital 8 were significantly more likely to be using LARC than women recruited at the other hospitals. Also, women born in the U.S. and those who had a public prenatal care provider were more likely to be using LARC if they preferred one of these methods.

Among women who wanted no more children there was no significant variability in preference across hospital of recruitment, and parity was the only variable significantly associated with preference for a long-acting or permanent method. In the model for use of a long-acting or permanent method among women with an elicited preference for one, there was significant variance across hospitals, but not between Hospital 8 and the others. Additionally, use of a long-acting or permanent method was lower among Non-Hispanic Blacks than among Hispanics, and higher among women 30+ compared to younger women and among US-born participants compared to the foreign-born. Finally, participants who received their prenatal care from a public clinic were more likely to use LARC or a permanent method than those who obtained care from a provider in private practice.

DISCUSSION

Our findings demonstrate substantial differences between the contraceptive methods used 6 months after delivery and the methods Texas women said they would prefer to be using at that time. Many more had a preference for LARC or sterilization than were actually using these methods. Moreover, about a third of women who reported a preference for or interest in using a long-acting or permanent method were using less effective methods such as condoms or withdrawal 6 months after delivery. The multivariable mixed-effects models of preferences for long-acting and permanent methods did not show significant variation across hospital of delivery, indicating that demand for highly effective contraception was not a localized phenomenon. In contrast, the models of using a long-acting or permanent method among participants who expressed a preference for such a method did show significant variation across hospitals. We believe that this variation together with the covariates identified in these models point to policy improvements that could lead to more women in Texas being able to access their preferred method of contraception.

The experience of the women recruited at the one hospital offering immediate postpartum LARC provision highlights the potential of policies that would permit hospitals and providers to be reimbursed for LARC placement outside the global delivery fee. More than a third of women who did not want to get pregnant in the next 2 years took advantage of this opportunity. Use of LARC remained high during the 6 months after delivery, and women with a preference for LARC who wanted more children were significantly more likely to realize that preference in this hospital than in the rest of the sample. While implementation of immediate postpartum LARC presents challenges and barriers that are not yet well understood,(23) the uptake of immediate postpartum provision at this hospital in Texas is surprisingly large. This uptake may be related to longstanding use of immediate postpartum placement of IUDs in Mexican public health institutions, coupled with the high proportion Mexican-origin foreign born participants among women delivering at this hospital. (24)

A second finding with policy implications is the disadvantage that foreign-born women have in both models of use given preference. The likely explanation is lack of insurance coverage for undocumented migrants for contraception after delivery. In Texas, undocumented women may be eligible to receive prenatal and postpartum care through the CHIP Perinatal program, which covers medical care related to the “unborn child.” CHIP Perinatal benefits include two postpartum visits, but contraception is not a covered benefit. Although the majority of the 15 states (including Texas) that provide undocumented women with coverage through the CHIP “unborn child” option do not cover contraception, Michigan recently proposed expanding postpartum coverage to include contraceptive services.(25) Texas and other states with the CHIP “unborn child” option should explore expanding the definition of postpartum services to include contraception.

A third finding worth noting are the differences associated with type of prenatal care provider. Not only are women who want more children more likely to have a preference for LARC if they received their prenatal care from a public clinic as compared to a private provider, but the likelihood of them actually using a highly effective method given preference is greater irrespective of childbearing intentions. This association may be due to the greater familiarity of personnel at public clinics with contraceptive method medical eligibility criteria, experience with counseling about and placement of IUDs and implants, the greater likelihood of stocking these methods, and the ability to obtain them at reduced prices.(26) It may be possible to narrow the gap in LARC provision by increasing communication between private providers and academic medical centers, as well through augmented outreach by the national and regional offices of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

Another notable finding is that Non-Hispanic Blacks who want no more children, and who would like to be using a long-acting or permanent method are less likely than other groups to obtain their preferred method. This result is in line with one previous study of unmet sterilization requests,(27) as well as qualitative work reporting that Black women encountered provider reluctance or refusal to perform sterilization procedure after their decision had been made.(16)

A limitation of this study is that the sample is not representative of the entire population of women who have Medicaid-paid deliveries in Texas. Compared with all Medicaid-paid deliveries statewide in 2013, our sample includes more Hispanic women (81% in the study vs. 49% statewide) and fewer White women (6% vs. 30%).(28) The proportion of Black women in our sample is also slightly less than among the statewide Medicaid deliveries (13% vs. 18%). These differences likely result from not including smaller hospitals serving rural area where births are disproportionately to White women,(29) and possibly from differences by race or ethnicity in the willingness of new mothers to participate in the study.

This study suggests that the limited use of long-acting and permanent contraceptive methods in the postpartum period by public patients in Texas results more from provider and system-level barriers than preferences. Further implementation of immediate postpartum LARC provision and extension of CHIP to include postpartum family planning for undocumented mothers could both help to reduce the current discrepancy between preferences and use, thereby reducing the incidence of unintended pregnancy and induced abortion.

Acknowledgments

Supported by a grant from the Susan Thompson Buffett Foundation, and a center grant from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (5 R24 HD042849) awarded to the Population Research Center at the University of Texas at Austin. The authors thank the following individuals who served as site investigators: Aida Gonzalez, MSN, RN, Moss Hampton, MD, Ted Held, MD, MPH, Nima Patel-Agarwall, MD, Sireesha Reddy, MD, Ruby Taylor, DNP, RN, Cristina Wallace, MD. Kami Geoffray, JD, offered helpful suggestions.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure

The authors did not report any potential conflicts of interest.

Each author has indicated that he/she has met the journal’s requirements for authorship.

References

- 1.White K, Teal SB, Potter JE. Contraception After Delivery and Short Interpregnancy Intervals Among Women in the United States. Obstet Gynecol. 2015 Jun;125(6):1471–7. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gemmill A, Lindberg LD. Short interpregnancy intervals in the United States. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122(1):64–71. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3182955e58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Teal SB. Postpartum Contraception: Optimizing Interpregnancy Intervals. Contraception. 2014;89(6):487–8. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2014.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zapata LB, Murtaza S, Whiteman MK, Jamieson DJ, Robbins CL, Marchbanks PA, et al. Contraceptive counseling and postpartum contraceptive use. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;212(2):171, e1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2014.07.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wilson EK, Fowler CI, Koo HP. Postpartum Contraceptive Use Among Adolescent Mothers in Seven States. J Adolesc Health. 2013 Mar;52(3):278–83. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zerden ML, Tang JH, Stuart GS, Norton DR, Verbiest SB, Brody S. Barriers to Receiving Long-acting Reversible Contraception in the Postpartum Period. Womens Health Issues [Internet] 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2015.06.004. [cited 2015 Sep 2]; Available from: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1049386715000924. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Luchowski AT, Anderson BL, Power ML, Raglan GB, Espey E, Schulkin J. Obstetrician-gynecologists and contraception: long-acting reversible contraception practices and education. Contraception. 2014 Jun;89(6):578–83. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2014.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Biggs MA, Arons A, Turner R, Brindis CD. Same-day LARC insertion attitudes and practices. Contraception. 2013 Nov;88(5):629–35. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2013.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ogburn JA, Tony, Espey E, Stonehocker J. Barriers to intrauterine device insertion in postpartum women. Contraception. 2005 Dec;72(6):426–9. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2005.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vaaler ML, Kalanges LK, Fonseca VP, Castrucci BC. Urban-rural differences in attitudes and practices toward long-acting reversible contraceptives among family planning providers in Texas. Womens Health Issues. 2012 Mar;22(2):e157–62. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2011.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aiken ARA, Creinin MD, Kaunitz AM, Nelson AL, Trussell J. Global fee prohibits postpartum provision of the most effective reversible contraceptives. Contraception. 2014 Nov;90(5):466–7. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2014.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zite N, Borrero S. Female sterilisation in the United States. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2011 Oct;16(5):336–40. doi: 10.3109/13625187.2011.604451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zite N, Wuellner S, Gilliam M. Barriers to obtaining a desired postpartum tubal sterilization. Contraception. 2006;73(4):404–7. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2005.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Potter JE, White K, Hopkins K, McKinnon S, Shedlin MG, Amastae J, et al. Frustrated demand for sterilization among low-income Latinas in El Paso, Texas. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2012 Dec;44(4):228–35. doi: 10.1363/4422812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gilliam M, Davis SD, Berlin A, Zite NB. A qualitative study of barriers to postpartum sterilization and women’s attitudes toward unfulfilled sterilization requests. Contraception. 2008 Jan;77(1):44–9. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2007.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Borrero S, Nikolajski C, Rodriguez KL, Creinin MD, Arnold RM, Ibrahim SA. “Everything I know I learned from my mother...or not”: perspectives of African-American and white women on decisions about tubal sterilization. J Gen Intern Med. 2009 Mar;24(3):312–9. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0887-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lawrence RE, Rasinski KA, Yoon JD, Curlin FA. Factors influencing physicians’ advice about female sterilization in USA: a national survey. Hum Reprod. 2011 Jan 1;26(1):106–11. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deq289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Allen RH, Desimone M, Boardman LA. Barriers to completion of desired postpartum sterilization. R I Med J. 2013;96(2):32–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.White K, Potter JE, Hopkins K, Grossman D. Variation in postpartum contraceptive method use: results from the Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS) Contraception. 2014 Jan;89(1):57–62. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2013.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Potter JE, Hopkins K, Aiken AR, Hubert C, Stevenson AJ, White K, et al. Unmet demand for highly effective postpartum contraception in Texas. Contraception. 2014 Nov;90(5):488–95. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2014.06.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Potter JE, Hubert Lopez C, Stevenson AJ, Hopkins K, Aiken ARA, White K, et al. Barriers to Postpartum Contraception in Texas and Pregnancy within Two Years of Delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2015 doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tang JH, Dominik R, Re S, Brody S, Stuart GS. Characteristics associated with interest in long-acting reversible contraception in a postpartum population. Contraception. 2013 Jul;88(1):52–7. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2012.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hofler LG, Cordes S, Cwiak CA, Goedken P, Jamieson DJ, Kottke M. Implementing Immediate Postpartum Long-Acting Reversible Contraception Programs. Obstet Gynecol. 2017 Jan;129(1):3–9. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Potter JE, Hubert C, White K. The availability and use of postpartum LARC in Mexico and among Hispanics in the United States. Matern Child Health J. 2016 Aug;26:1–9. doi: 10.1007/s10995-016-2179-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Michigan Department of Health and Human Services Medical Services Administration. Family Planning Services for Maternity Outpatient Medical Services (MOMS) Program EnrolleesProposed Policy Draft [Internet] Michigan Department of Health and Human Services Medical Services Administration; 2017. [cited 2016 Mar 21]. Available from: http://ac.els-cdn.com/S1054139X97002024/1-s2.0-S1054139X97002024-main.pdf?_tid=2f3cbbb2-ef77-11e5-bf6d-00000aacb35d&acdnat=1458573267_fca67922c25cd711cf44ed799c49ae76. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Biggs MA, Harper CC, Malvin J, Brindis CD. Factors influencing the provision of long-acting reversible contraception in California. Obstet Gynecol. 2014 Mar;123(3):593–602. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zite N, Wuellner S, Gilliam M. Failure to obtain desired postpartum sterilization: Risk and predictors. Obstet Gynecol. 2005 Apr;105(4):794–9. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000157208.37923.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Texas Health and Human Services Commission. Texas Medicaid and CHIP in Perspective, Tenth Edition [Internet] Texas Health and Human Services Commission; 2015. [cited 2017 Jan 12]. Available from: https://hhs.texas.gov/sites/hhs/files/documents/services/health/medicaid-chip/book/pink-book.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lichter DT, Sanders SR, Johnson KM. Hispanics at the Starting Line: Poverty among Newborn Infants in Established Gateways and New Destinations. Soc Forces. 2015 Sep;94(1):209–35. [Google Scholar]