Abstract

Esophageal cancer is an aggressive tumor and is the sixth leading cause of cancer death worldwide. ATP is well known to regulate cancer progression in a variety of models by different mechanisms, including P2X7R activation. This study aimed to evaluate the role of P2X7R in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) proliferation. Our results show that treatment with high ATP concentrations induced a decrease in cell number, cell viability, number of polyclonal colonies, and reduced migration of ESCC. The treatment with the selective P2X7R antagonist A740003 or siRNA for P2X7 reverted this effect in the KYSE450 cell line. In addition, results showed that P2X7R is highly expressed, at mRNA and protein levels, in KYSE450 lineage. Additionally, KYSE450, KYSE30, and OE21 cells express P2X3R, P2X4R, P2X5R, P2X6R, and P2X7R genes. P2X1R is expressed by KYSE30 and KYSE450, and only KYSE450 expresses the P2X2R gene. Furthermore, esophageal cancer cell line KYSE450 presented higher expression of E-NTPDases 1 and 2 and of Ecto-5′-NT/CD73 when compared to normal cells. This cell line also exhibits ATPase, ADPase, and AMPase activity, although in different levels, and the co-treatment of apyrase was able to revert the antiproliferative effects of ATP. Moreover, results showed high immunostaining for P2X7R in biopsies of patients with esophageal carcinoma, indicating the involvement of this receptor in the growth of this type of cancer. The results suggest that P2X7R may be a potential pharmacological target to treat ESCC and can lead us to further investigate the effect of this receptor in cancer cell progression.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s11302-017-9559-2) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: P2X7R, Esophageal cancer, Proliferation, ATP, Ectonucleotidases

Introduction

Esophageal carcinoma is classified as the sixth most common cause of death due to cancer in the world and has substantial effect on public health [1]. In southern Brazil, without considering the non-melanoma skin tumors, esophageal cancer is the fifth most common cause of death that may be related to the excessive drinking of mate herb (Ilex paraguariensis) in high temperature, very common in this region [2], among other possible causes [3]. The main risk factors are smoking and alcohol intake [4, 5], genetic factors, and HPV infection [6]. This malignancy has a very poor survival rate, and esophageal cancer mortality closely follows the geographical patterns for incidence, and the highest mortality rates are found in Eastern and Southern Africa and East Asia [7].

Tumors originated in the esophageal mucosa are classified into two major histologic types: adenocarcinoma (AC) and esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC). The incidence of AC has increased greatly in the past 40 years (approximately 600% since the 1970s) [8]. Many researchers have suggested that the concurrent epidemic of obesity associated with persistent gastroesophageal reflux from areas with specialized intestinal metaplasia in the distal esophagus (i.e., Barrett esophagus) may explain at least part of this increase [8, 9]. ESCC is still the predominant form of esophageal neoplasia worldwide [10], and AC may be associated with a better long-term prognosis after resection than ESCC [9]. In fact, ESCC comprehends more than 90% of esophageal cancers and the prognosis for this type of cancer is poor. Generally, the overall 5-year survival rate is 10–15%, especially in cases in which the disease is detected at advanced stages [11–13].

The purinergic signaling was first proposed in 1972, and further, the role of ATP as a proinflammatory mediator was established [14, 15]. The conversion of ATP/ADP to adenosine is a result of coaction of cell-surface purinergic enzymes called ectonucleotidases, such as E-NTPDase1 (CD39) or E-NTPDase2 and Ecto-5′-nucleotidase/CD73 (CD73) [16]. ATP and ADP are the main ligands of the P2 purinergic receptors and the ionotropic P2X and metabotropic P2Y receptors [17]. Nucleotides and nucleosides accumulate within the tumor microenvironment [14, 15], and ATP is known to inhibit the growth of cancer cells in a variety of models and through different mechanisms [18]. In effect, P2X7 receptor (P2X7R) has attracted much of the attention during the last years in the context of cancer disease [19–24]. Our group has characterized two glioma cell lines (GL261 and M059J) as sensitive to high concentrations of ATP and to the P2X7R agonist BzATP [25, 26]. Furthermore, other studies in the literature also showed the antiproliferative effect of ATP-P2X7R pathway in human melanoma, gliomas, and human cervical epithelial cells [27–29]. However, other groups demonstrated that P2X7R can accelerate tumor growth [30–33]. Whether extracellular ATP accumulation will turn out to be beneficial or detrimental for the host will depend on ATP concentration, the rate of degradation to adenosine, the panel of P2 receptors expressed by the cancer cells, and by the infiltrating inflammatory cells [14].

Whereas the role of purinergic system has been widely described in different types of tumors, little is known about the effect of high ATP concentrations in ESCC. Therefore, the characterization of purinergic receptors, particularly the P2XR, in this type of tumor becomes of great interest. Accordingly, in this study, we investigated the role of P2X7 receptor in human esophageal squamous cell carcinoma proliferation.

Materials and methods

Reagents

To develop this paper, some specific reagents were used. For cell culture, the fetal bovine serum (FBS), cell culture medium, penicillin/streptomycin, and trypsin/EDTA were purchase from GIBCO/Invitrogen (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA). The nucleotides ATP, ADP, AMP, and adenosine as well the antagonist of P2X7R (A740003), unspecific antagonist of P2R (Pyridoxal phosphate-6-azo(benzene-2,4-disulfonic acid) tetrasodium salt hydrate - PPADS and suramin), and apyrase were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich.

Esophageal cell lines and cell culture

Cell lines KYSE30, KYSE450, and KYSE520 (obtained commercially from Deutsche Sammlung von Mikroorganismen und Zellkulturen), originally established from surgical specimens of primary esophageal squamous cell carcinomas (ESCC) and OE21, donated by Dr. Luis Felipe Ribeiro Pinto (INCA) were maintained in RPMI cell culture medium, supplemented with 10% FBS, 50 units of penicillin/mL, and 50 mg streptomycin/mL. Primary normal esophageal epithelial cells (EPC2) established from normal human esophagus was maintained in Keratinocyte-SFM medium (Gibco BRL, Rockville, MD, USA) containing bovine pituitary extract (40 mg/mL). All cell lines were maintained in a humidified cell incubator (37 °C, 5% CO2, and 95% humidity).

Cell viability

To evaluate the cell viability, the experiments were performed as described previously by Gehring [26]. Cell lines were seeded at a density of 6.5 × 103 per well on a 96-well plate with 100 μL of culture medium. After, the cells were treated with different concentrations of ATP by 24 and 48 h. At the end of this period, the medium was removed, the cells were washed with PBS, and 100 μL of 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide solution (MTT) (MTT 5 mg/mL in PBS in 90% DMEM supplemented with FBS 10%) was added to the cells and incubated for 3 h. The formazan crystals were dissolved with 100 μL of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO). The absorbance was quantified in 96-well plates (Spectra Max M2e, Molecular Devices) at 570 nm. This absorbance was linearly proportional to the number of live cells with active mitochondria.

Cell counting

Cells were plated at 15 × 103 cells/well per well, in 24-well plates, with RPMI medium supplemented with 10% FBS and grown for 24 h. After this time, the medium was removed and RPMI medium supplemented with 5% FBS was added and the cells were incubated for more 24 h. At 48 h, the medium supplemented with 5% FBS was changed by RPMI medium supplemented with 0.5% FBS. This method of FBS reduction is used for obtaining all cells in the same condition, to synchronize the cell cycle. The cells with medium supplemented with 0.5% FBS were incubated for more 24 h and then were treated with ATP 1, 3, and 5 mM. Following treatment, the cell number was determined at 24, 48, and 72 h. At the end of the period of the treatment, the medium was removed and the cells were washed with calcium and magnesium-free medium (CMF) and 100 μL of 0.23% trypsin/EDTA solution was added to detach the cells. Following that, the cell number was determined by Countess FL cell counter (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA). The results were expressed as percent in relation to control.

Clonogenic assay

Esophageal cancer cell lines, KYSE30, KYSE450, and OE21, were plated around 2 × 102 cells per well in a 12-well plate. After 24 h, cells were treated with ATP 1, 3, and 5 mM and maintained in culture for 10 days. The treatments were renovated once every 2 days. At the end of the experiment, the cells were washed with PBS, fixed with formalin 4% for 5 min, and stained with gentian violet by 5 min. At the sequence, cells were washed two times with PBS and stored at room temperature to dry. After 24 h, the images were obtained by Cyber-shot DSC-W510 Sony Picture 12.1 M pixels and the number of colonies was determined by WCFI ImageJ software (NIH) (http://www.uhnresearch.ca/facilities/wcif/imagej/). The results were demonstrated as absolute number of colonies.

Scratch-wound migration assay

The migration assay was performed as described [56]. Before plating the cells in the 12 multiwell plates, two parallel lines are drawn at the underside of the plates with a Sharpie Marker. These lines served as fiducial marks for the wounded areas to be analyzed. The cells were cultured 70% of confluence as described above. Before making wound in the cell monolayer, the culture medium was aspirated and was added with calcium-free PBS to prevent killing of cells at the edge of the wound by exposure to high calcium concentrations. One scratch width was made perpendicular to the marker lines with a yellow P200 pipette tip. This procedure makes possible to image the entire width of the wound using a ×10 objective. The wounds are observed using phase contrast microscopy on an inverted microscope. Images were taken at regular intervals of 0, 24, and 48 h. Images are analyzed by digitally drawing lines (using Adobe Photoshop) averaging the position of the migrating cells at the wounded edges. The cell migration distance is determined by measuring the width of the wound divided by two and by subtracting this value from the initial half-width of the wound.

RT-PCR

The expression of purinergic receptors P2X (1–7) was conducted by RT-PCR technique. KYSE30, KYSE450, and OE21 esophageal cancer cell lines were seeded at 2 × 105 cells per well in six-well plates and grown for 24 h. After, total RNA were isolated with TRIzol LS reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. The total RNA was quantified by spectrophotometry, and the cDNA were synthesized with ImProm-II™ Reverse Transcription System (Promega) from 1 μg total RNA, in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. In the sequence, reaction mixes were used for RT-PCR in a total volume of 25 μL which included 12.5 μL of the GoTaq Green Master Mix (Promega), 2.5 μL of each specific primer at 10 μM (Table 1), 2 μL of respective cDNA samples, and nuclease-free water up to a total volume of 25 μL. The PCR cycling conditions were as follows: 10 min at 90 °C, 45 s at 95 °C, 45 s at 60 °C to primer annealing, and 45 s at 72 °C. All PCR reactions were carried out for 40 cycles and included a final 10-min extension at 72 °C. Ten microliters of the RT-PCR reaction was analyzed on a 2.0% agarose gel containing ethidium bromide and visualized under ultraviolet light. As a control for cDNA synthesis, glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) PCR was performed. Negative controls were performed by substituting the templates for DNAse/RNAse-free distilled water in each PCR reaction.

Table 1.

Primer sequence used to RT-PCR and RT-qPCR analysis

| Gene | Primer sequence RT-qPCR |

|---|---|

| ENTPD1a F | 5′-CTACCCCTTTGACTTCCA-3′ |

| ENTPD1a R | 5′-CTCCCCCAAGGTCCAAAGC-3′ |

| ENTPD2a F | 5′-GGGTGCACGCATCCTCTCG-3′ |

| ENTPD2a R | 5′-CCTCGCTGGCTCTGTCCTC-3′ |

| CD73a F | 5′-GCTGGCGCCTGGGAGCTTAC-3′ |

| CD73a R | 5′-TCCAGCAGCAGCACGTTGGG-3′ |

| P2X7a F | 5′-AGGCAGTGGAAGAGGCCCCC-3′ |

| P2X7a R | 5′-AGTTGTGGCCGGGGAAGTCG-3′ |

| Gene | Primer sequence RT-PCR |

| P2RX1 F | 5′-GCTGGTGCGTAATAAGAAGGTG-3′ |

| P2RX1 R | 5′-ATGAGGCCGCTCGAGGTCTG-3′ |

| P2RX2 F | 5′-AGGTTTGCCAAATACTACAAGATC-3′ |

| P2RX2 R | 5′-GCTGAACTTCCCGGCCTGTC-3′ |

| P2RX3 F | 5′-CTTCACCTATGAGACCACCAAG-3′ |

| P2RX3 R | 5′-CGGTATTTCTCCTCACTCTCTG-3′ |

| P2RX4 F | 5′-GATACCAGCTCAGGAGGAAAAC-3′ |

| P2RX4 R | 5′-GCATCATAAATGCACGACTTGAG-3′ |

| P2RX5 F | 5′-GGCATTCCTGATGGCGCGTG-3′ |

| P2RX5 R | 5′-GGCACCAGGCAAAGATCTCAC-3′ |

| P2RX6 F | 5′-AGCACTGCCGCTATGAACCAC-3′ |

| P2RX6 R | 5′-AGTGAGGCCAGCAGCCAGAG-3′ |

| P2RX7 F | 5′-TGATAAAAGTCTTCGGGATCCGT-3′ |

| P2RX7 R | 5′-TGGACAAATCTGTGAAGTCCATC-3′ |

| GAPDH F | 5′-AACGGATTTGGTCGTATTGGGC-3′ |

| GAPDH R | 5′-CTTGACGGTGCCATGGAATTTG-3′ |

F forward, R reverse

aMelting curve analysis was performed to determine the specificity for each qPCR reaction

Real time (RT-qPCR)

The expression of E-NTPDase1, E-NTPDase2, and CD73 and P2X7R in esophageal cancer cell lines was conducted by quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) technique. KYSE30, KYSE450, and OE21 esophageal cancer cells and EPC2, representative of a normal esophageal tissue, were seeded at 2 × 105 cells per well in six-well plates and grown for 24 h. After, total RNA were isolated and quantified and cDNA were synthesized as described in RT-PCR method. RT-qPCR was performed using SYBR Green I (Invitrogen) to detect double-strand cDNA synthesis. Reactions were done in a volume of 25 μL using 12.5 μL of diluted cDNA (1:50), containing a final concentration of 0.2× SYBR Green I (Invitrogen), 100 μM dNTP, 1× PCR Buffer, 3 mM MgCl2, 0.25 U Platinum Taq DNA Polymerase (Invitrogen), and 200 nM of specific primers listed in Table 1. At the end of cycling protocol, a melting curve analysis was included and fluorescence measured from 60 to 99 °C. Relative expression levels were determined with 7500 Fast Real Time System Sequence Detection Software v.2.0.5 (Applied Biosystems). The efficiency per sample was calculated using LinRegPCR 11.0 Software (http://LinRegPCR.nl). Relative mRNA expression levels of different cell lines were determined using the ΔCq method using GAPDH expression as endogenous control for each lineage.

Western blotting

Confluent esophageal cell cultures were washed three times with ice cold Tris–saline buffer (150 mM NaCl, 20 mM Tris, pH 7.5) and lysed in cell lysis buffer (100 mM NaCl, 1% Nonidet P40, 1 mM sodium orthovanadate, 100 mM sodium fluoride, 0.5 μg/mL aprotinin, 1 μg/mL leupeptin and 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 20 mM Tris, pH 7.5), incubated on ice for 20 min, and then centrifuged for 5 min at 14,000×g and 4 °C. Protein concentrations were measured using a Bio-Rad DC kit (Hercules, CA, USA) detergent compatible protein assay, according to the manufacturer’s protocol. SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) was performed by loading 60 μg of protein on a 4–12% polyacrylamide gel (50 μL/well) under non-reducing conditions followed by transfer to PVDF membrane (Immobilon P, Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA) by semidry electroblotting. After blocking with 5% milk in Tris–saline buffer containing 0.1% Tween 20, membranes were probed with an appropriate antibody to P2X7R Alomone Labs (diluted 1:1000) at 4 °C overnight and visualized using horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA) (diluted 1:10,000), followed by enhanced chemiluminescence assay (New England Nuclear, Beverly, MA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The resulting bands were subjected to densitometric analysis with the ImageJ software. P2X7R levels were normalized by comparison to GAPDH.

RNA interference

siRNA specific to human P2X7R were expressed using the pSilenceradeno 1.0-CMV System (Ambion) targeting mRNA sequences specific to P2X7R. KYSE450 cells were seeded in six-well plates (80% confluence) and transfected with P2X7R siRNA plasmid (0.5 μg) using the transfection reagent Lipofectamine 2000. The silencing cells were nominated as KYSE450 siP2X7R cells, and the control cells of this experiment were nominated KYSE450 GFP−/− cells. Expression levels of P2X7R were analyzed 48 h after transfection through Western Blotting assay. After the silencing, KYSE450 GFP−/− cells and KYSE450 siP2X7R cells were plated. Following 24 h MTT experiments were performed to investigate the effect of P2X7R silencing on cell viability. In addition, to evaluate the effect of ATP, siP2X7R cell line was treated with ATP 2.5 and 5 mM and the cell viability was performed 24 h after treatment.

E-NTPDase activity

In order to determine E-NTPDase activities, ESCC lineages (KYSE30, KYSE450, and OE21) were trypsinized and 1 × 105 cells were added to the reaction mixture containing 50 mM Tris–HCl (pH 8.0) and 5 mM CaCl2 (for E-NTPDase activities) or 50 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.2) and 5 mM MgCl2 (CD73 activity) in a final volume of 200 μL. Samples were preincubated for 10 min at 37 °C before starting the reaction with the addition of substrate (ATP, ADP, or AMP) to a final concentration of 1 mM. The reaction was stopped after 30 min with the addition of 200 μL of trichloroacetic acid at a final concentration of 5%. The samples were chilled on ice for 10 min and 1 mL of a colorimetric reagent composed of 2.3% polyvinyl alcohol, 5.7% ammonium molybdate, and 0.08% malachite green was added in order to determine the inorganic phosphate released (Pi) [34]. The quantification of Pi released was determined spectrophotometrically at 630 nm, and the specific activity was expressed as nanomole Pi per minute per 105 cells. In order to correct nonenzymatic hydrolysis of the substrates, controls with the addition of the enzyme preparation after the addition of trichloroacetic acid were used.

Human sample immunohistochemistry

The expression of P2X7R receptors in esophageal tissue was assessed by immunostaining of formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded material. Histological samples of human ESCC and esophageal tissue samples of patients with esophagitis were collected, between July and December 2015, from patients who underwent endoscopic procedures with biopsies and/or surgical resection at Pontificia Universidade Católica do Rio Grande do Sul (PUCRS, Porto Alegre, Brazil). The diagnosis was reviewed by two certified pathologists with at least 20-year experience in surgical pathology. Samples were obtained in accordance with approved ethical standards of the Institutional Research Ethics Committee (CAAE 49696115.0.0000.5336). The biopsies were processed as previously as described by Gehring et al. [26]. Anti-P2X7R antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) was used at the dilution of 1:100 followed by anti-IGG peroxidase and diaminobenzidine (DAB) staining with positive and negative external tissue samples as controls. The samples were lightly counterstained with hematoxylin in order to confirm the tumor localization. P2X7R expression was analyzed by WCFI ImageJ software (NIH) (http://www.uhnresearch.ca/facilities/wcif/imagej/) as follows: the immunohistochemistry sample images were captured and saved in TIFF uncompressed format with the same white balance calibration and time exposure by a RETIGA 2000R CCD videocamera (QImaging, Surrey, Canada) attached to a Zeiss Axioskop 40 microscope (Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany). The microscope was adjusted at a fixed light intensity level, Koehler illumination adjustment, and fixed condenser iris aperture. The image files were submitted to color deconvolution with “Plugins/Color Functions” and “H&E DAB.”

Statistical analyses

The statistical test used was one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by Tukey-Kramer post hoc test or Student’s t test. Results were presented as standard error of the mean. GraphPad Prism 5.0® program was used to generate graphs. P values <0.05 were taken to indicate statistical significance.

Results

High ATP levels are cytotoxic to human ESCC cells

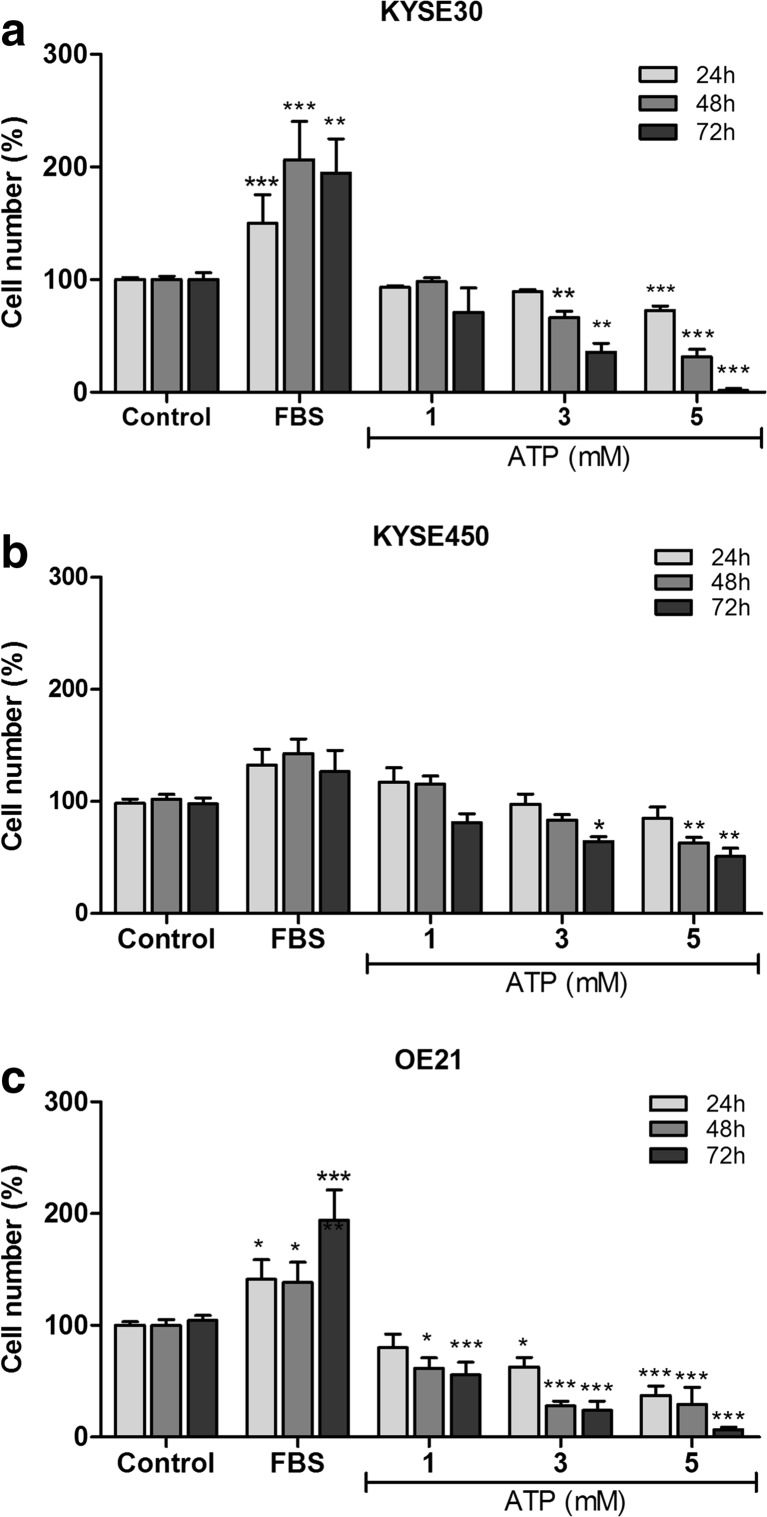

In this study, we first tested the effect of ATP treatment (1, 3, or 5 mM) after 24, 48, and 72 h on the proliferation of ESCC lineages (KYSE30, KYSE450, and OE21). As shown in Fig. 1, ATP 5 mM promoted a reduction on the number of cells in KYSE30 and OE21 lineages in all times evaluated. KYSE450 presented a significant reduction on the number of cells after 48 and 72 h of treatment with high ATP concentration (5 mM). In addition, when the esophageal cancer cells were treated with ATP 3 mM, it was observed that there was a significant reduction in the cell number of KYSE450 after 72 h, KYSE30 after 48 and 72 h, and OE21 in all the times tested. ATP 1 mM was effective in decreasing the cell number just in OE21 lineage after 48 and 72 h posttreatment (Fig. 1). We also have performed cell counting experiments with lower ATP concentrations (50, 100, and 500 μM), and there were no differences observed in the number of cells (data not shown).

Fig. 1.

Evaluation of cell number after ATP treatment on human ESCC cell lines. The cell counting experiments were used as indicative of cell proliferation on KYSE30 (a), KYSE450 (b), and OE21 (c) cell lines. The cells were evaluated after 24, 48, and 72 h under treatment with ATP (1, 3, or 5 mM). The medium DMEM supplemented with 10% of FBS was used a positive control of cell proliferation. The experiments were performed three times in triplicate. Each column represents the mean ± SEM, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001, and the results were established in relation to control cells

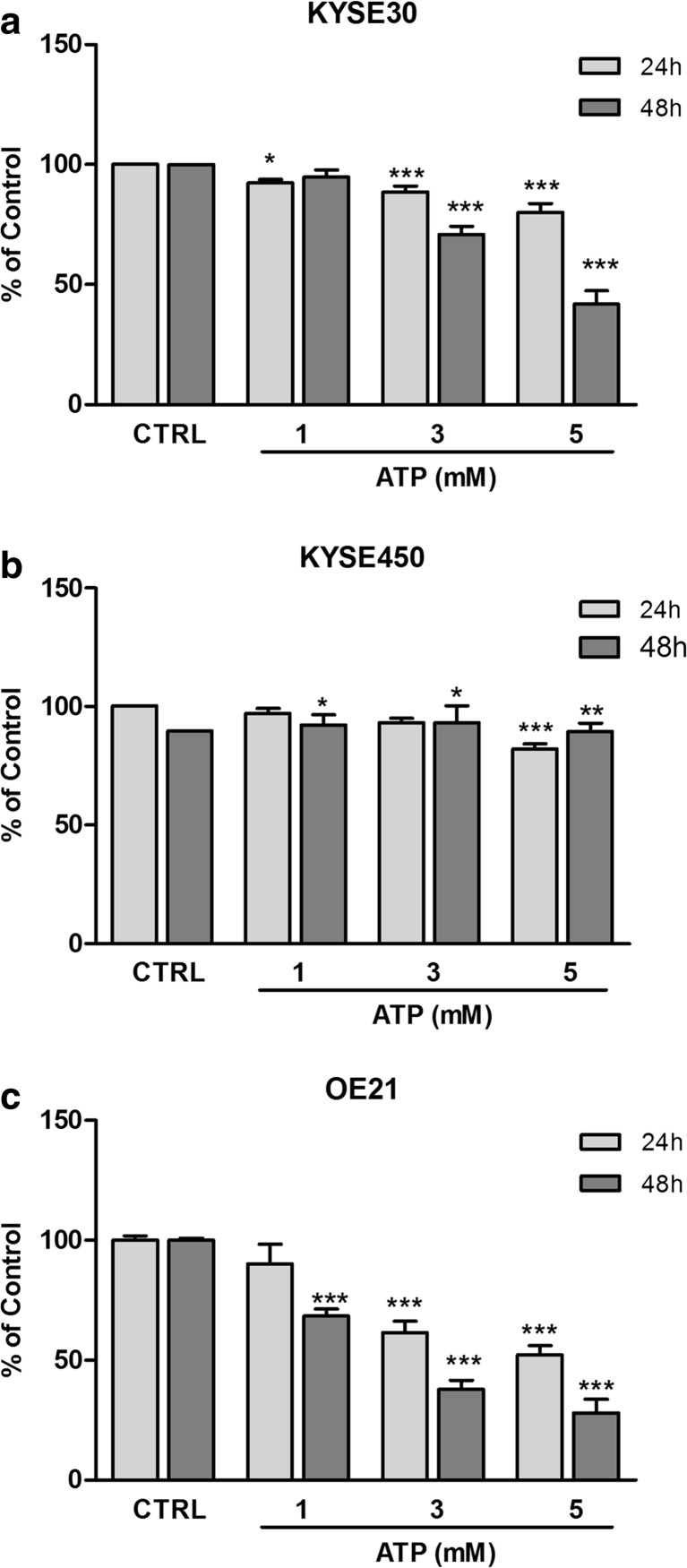

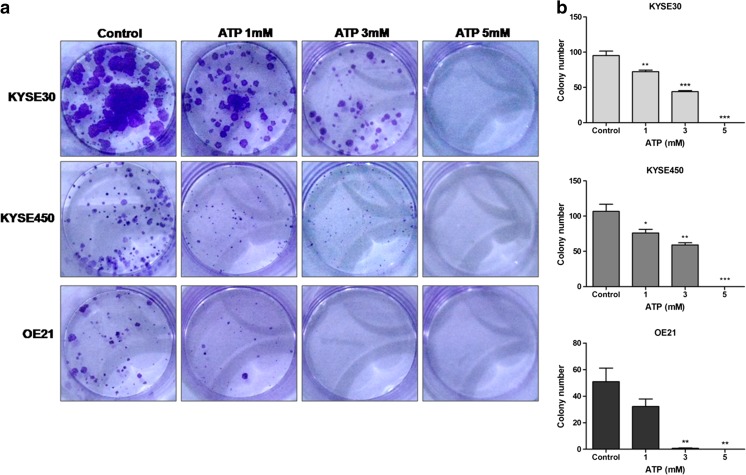

To confirm previous data, we investigated the effect of ATP on ESCC cell viability through MTT assay. Our analysis demonstrated that treatment with ATP 3 or 5 mM significantly reduced the viability of KYSE30 (Fig. 2a), KYSE450 (Fig. 2b), and OE21 cells (Fig. 2c) after 24 and 48 h posttreatment. Furthermore, treatment with ATP 1 mM significantly reduced OE21 and KYSE450 cell viability 48 h and KYSE30 after 24 h posttreatment. In addition, to better evaluate the antiproliferative effect of ATP treatment, we performed the clonogenic assay (Fig. 3). We observed that long-term treatment (10 days) with ATP 1, 3, and 5 mM reduced significantly the number of polyclonal colonies and their diameter when compared to control in all cell lines tested. Taken together, these results suggest that treatment with ATP can reduce esophageal cancer cell proliferation when this nucleotide is administrated at high concentrations. Lastly, we evaluated the effects of high ATP concentrations on KYSE450 cell migration. Interestingly, we observed that this nucleotide reduced the migration of cells after 24 h of ATP 5 mM treatment and cells treated with ATP 1 and 3 mM reduced migration after 48 h (Fig. S1).

Fig. 2.

Evaluation of cell viability after ATP treatment on human ESCC cell lines. Cell viability was evaluated by MTT 24 and 48 h after treatment with ATP (1, 3, or 5 mM) in KYSE30 (a), KYSE450 (b), and OE21 (c) cell lines. Each column represents the mean ± SEM, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001. The experiments were performed three times in triplicate to KYSE30 and OE21 and five times in triplicate to KYSE450. The results were established in relation to control cells (not treated and considered as 100% of cell viability)

Fig. 3.

Ability of ESCC cells to form new colonies after ATP treatment. The clonogenic assay was performed to evaluate the interference of ATP on cell proliferation after 10 days of treatment as described in “Material and Methods.” Evaluation of polyclonal cell population (a) and quantification of colony number (b). Each column represents the mean ± SEM, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001, and the results were established in relation to control cells. The experiments were performed in triplicate

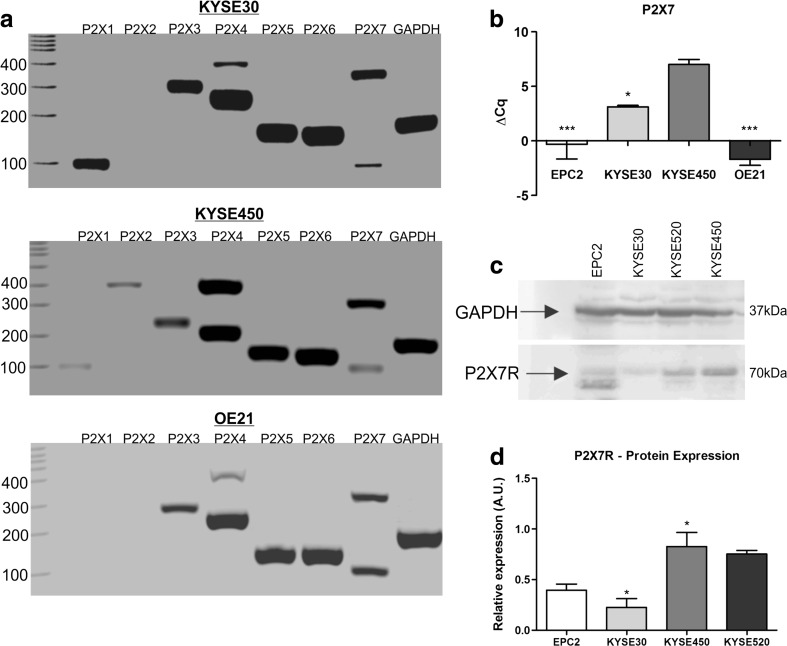

ESCC cells express multiple P2X purinergic receptors subtypes

In order to understand the molecular mechanism involved in reduction of ESCC proliferation, purinergic P2X receptors expression profile was studied by RT-PCR (Fig. 4a). KYSE30 cell line expressed P2X1, P2X3, P2X4, P2X5, P2X6, and P2X7, while KYSE450 expressed all P2X receptors described in literature. OE21 lineage expressed P2X3, P2X4, P2X5, P2X6, and P2X7 purinergic receptors. It is worth to mention that we identified two bands in P2X4 and P2X7 PCR analysis, and this is possibly due to the amplification of other variants existing for the two genes [57]. This set of results demonstrates that the majority of P2X receptors were expressed in ESCC cell lines evaluated.

Fig. 4.

Analysis of P2X receptor expression profile in human ESCC cell lines. Expression of purinergic receptors P2X1–7 in KYSE30, KYSE450, and OE21 cells lines by RT-PCR (a). GAPDH expression was used as reference gene. RT-qPCR analysis of P2X7R relative expression was performed, and the values were shown as ΔCq relative expression in relation to GAPDH in EPC2, KYSE30, KYSE450, and OE21 cell lines (b) and the significance was described as *p < 0.05 and *** p < 0.001 indicating difference in relation to KYSE450. Representative Western blotting assays showing positivity to P2X7R in EPC2, KYSE30, KYSE450, and KYSE520 cells (c). Relative P2X7R levels obtained by analysis of protein bands detected by Western blot were compared to GAPDH expression levels (d) and the significance was described as *p < 0.05 and *** p < 0.001 indicating difference in relation to EPC2. Each column represents the mean ± SEM and the experiments were performed three times in triplicate

Subsequently, as P2X7 receptor (P2X7R) is the most studied purinergic receptor in cancer and it is activated by high ATP concentrations, we focus on investigating its role in ESCC proliferation. Confirming our hypothesis, KYSE450 presented a prominent expression of P2X7R when compared to the other ESCC cells evaluated and also to EPC2, representative of a normal esophageal tissue (Fig. 4b). These results are in agreement with the P2X7R protein expression presented in Fig. 4c, d.

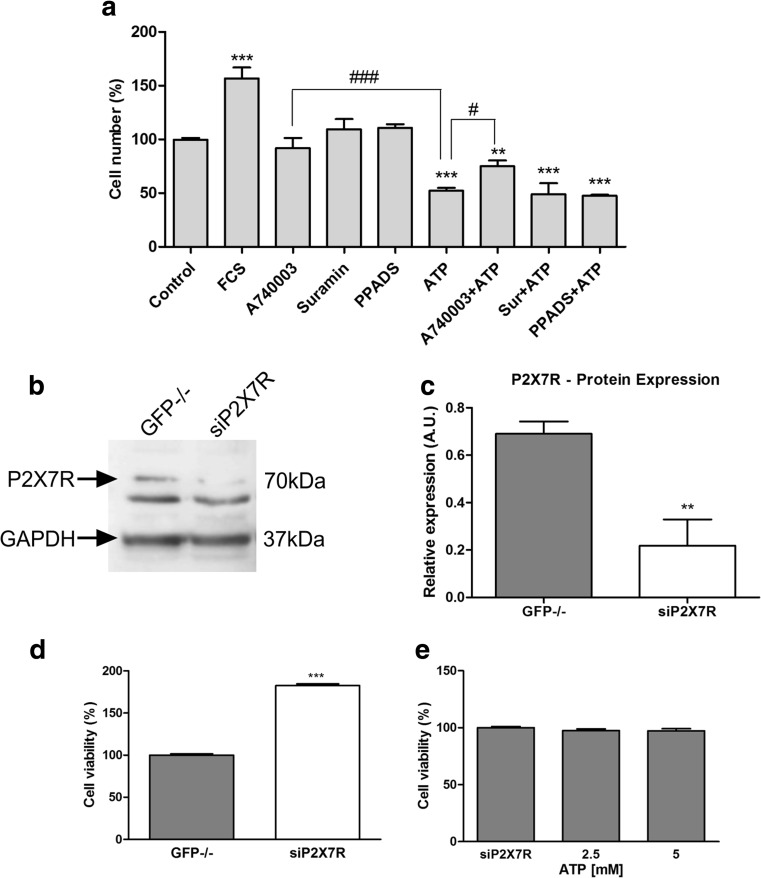

High ATP levels induce cytotoxicity through P2X7R on KYSE450 human ESCC

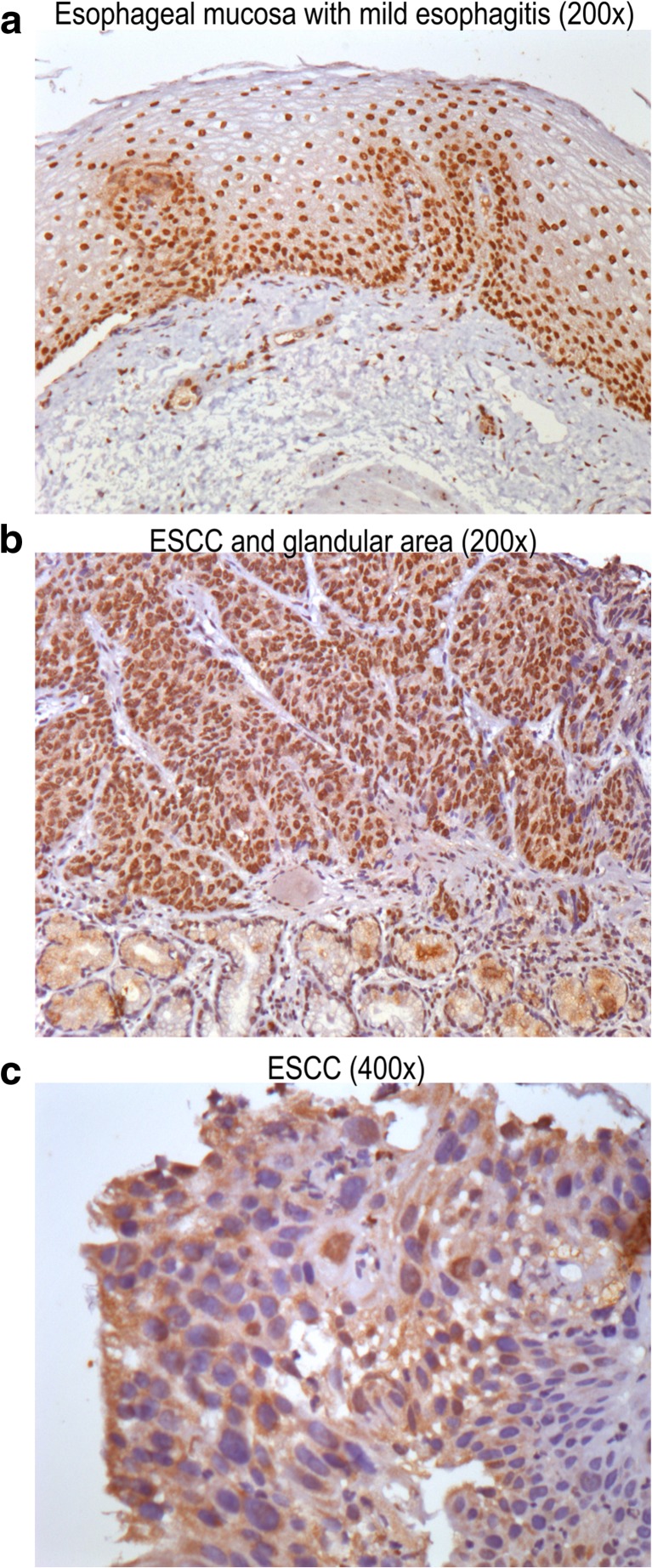

As it is known high ATP concentrations activate P2X7R while they desensitize the other P2X receptors [35, 36]. To confirm the participation of P2X7R in ATP cytotoxic effects, we performed a set of pharmacological antagonism experiments. As demonstrated in Fig. 5a, the selective P2X7R antagonist, A740003 (10 μM), was effective in reverting the cytotoxic effect of ATP 5 mM. In addition, suramin (30 μM) or PPADS (10 μM) that are described as unspecific P2R antagonists did not present any effects in modulating ATP cytotoxicity. Besides, A740003, suramin, and PPADS alone maintained the number of cells similar to control. Next, we generated ESCC cells where P2X7R gene was inhibited by siRNA technology (KYSE450 siP2X7). As seen in Fig. 5b, c, P2X7R silencing on KYSE450 was confirmed by Western Blotting assays and compared to KYSE450 GFP−/− cells. GFP−/− siRNA vector was used as siRNA control and did not show any significant difference in P2X7R protein expression levels when compared to KYSE450 WT cells (data not shown). In order to investigate the P2X7R silencing effect on KYSE450 cells, we analyzed the cell viability of these cells when compared to KYSE450 GFP−/− cells. KYSE450 siP2X7 showed an accelerated growth rate of 82 ± 2% cells, when compared to KYSE450 GFP−/− (Fig. 5d), suggesting that the low P2X7R expression may confer proliferative capacity for this esophageal cancer cell line, and the presence of P2X7R, when stimulated by ATP, reduces the proliferation of cancer cells. We further treated KYSE450 siP2X7 cells with ATP (2.5 and 5 mM). As expected, ATP-induced cytotoxicity was abolished in the siP2X7R cells (Fig. 5e), confirming that ATP induces a decrease in cell viability via P2X7R in KYSE450 cells. Human samples of esophageal biopsies of mild esophagitis (Fig. 6a) and squamous cell carcinoma (Fig. 6b, c) were analyzed regarding P2X7R expression by immunohistochemistry. Representative images demonstrate an area of normal-appearing esophageal mucosa showing marked nuclear positivity for P2X7R (Fig. 6a), whereas immunoreactive receptors were markedly increased in ESCC (Fig. 6b, c) showing nuclear positivity for P2X7R. Figure 6B depicts ESCC cells among glandular epithelium showing membrane positivity for P2X7R. Some cells of lamina propria and a few glandular cells also present nuclear positivity.

Fig. 5.

Modulation of P2X7R reduces the effect cytotoxic generated by ATP in high concentrations. a Pharmacological modulation of P2X7R was performed by cell counting after treatment with A740003 10 μM, a specific antagonist of P2X7R, suramin 30 μM, and PPADS 10 μM as unspecific antagonist of P2X receptors and ATP 5 mM. The treatment was performed after sequential reduction of FBS concentration, and the cell counting was performed after 48 h posttreatment. The difference in relation to control was determined as **p < 0.01 and ***p < 0.001. The difference of ATP 5 mM was determined as #p < 0.05 and ###p < 0,001. b Representative Western blotting assays showing positivity to P2X7R in KYSE450 GFP−/− and KYSE450 siP2X7R. c Relative P2X7R levels obtained by analysis of protein bands detected by Western blot were compared to GAPDH expression levels and the significance was described as **p < 0.01 and indicated difference in relation to GFP−/−. d Effect of P2X7R silencing on cell viability. After 48 h of silencing, the cells were plated and MTT assays were performed following 24 h. The significance was described as ***p < 0.001 and indicated difference in relation to GFP−/−. e Effect of ATP (2.5 and 5 mM) treatment on siP2X7R cell viability. The experiments were performed three times in triplicate

Fig. 6.

Immunostaining for P2X7 receptors in human esophageal samples. Representative images demonstrate the area of normal appearing esophageal mucosa with mild esophagitis (DAB, nuclear brown staining, ×200) (a), ESCC and glandular cells (b), and ESCC area (DAB, membrane brown staining, ×400) (c)

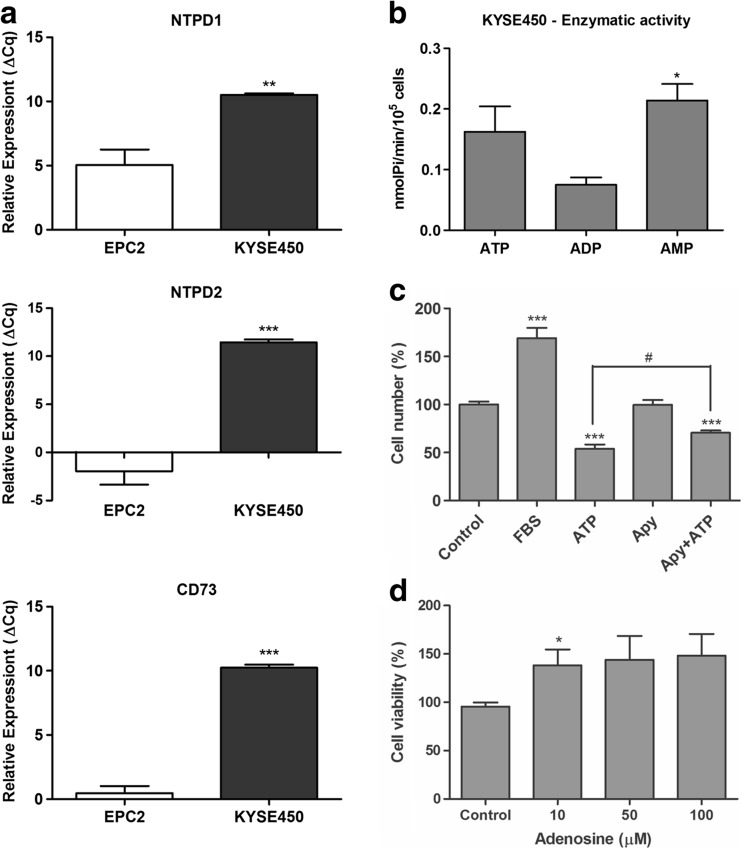

E-NTPDases and CD73 expression profile on human ESCC

With the intention to explain the nucleotide metabolism in ESCC cell lines, we evaluated E-NTPDase1 and 2 and CD73 expression levels using RT-qPCR (Fig. 7a and S2A) and determined their enzymatic activity (Fig. 7b and S2B). KYSE450 presented higher levels of NTPD1 and 2 expression when compared to ECP2 cells (Fig. 7a). In agreement to the elevated expression of NTPDases, we demonstrated that this cell line showed an elevated ATP hydrolysis (Fig. 7b). Besides, our data showed that KYSE450 and the other ESCC cell lines studied presented a low ADPase activity when compared to ATP hydrolysis activity. The low hydrolysis of ADP could maintain higher levels of this nucleotide leading to ESCC cell proliferation. This postulation might be supported by the results presented in Fig. 7c, where the additional treatment with apyrase promoted a reduction of ATP cytotoxic effect.

Fig. 7.

Evaluation of E-NTPDases and CD73 expression and activity in KYSE450 esophageal cancer cell line. a RT-qPCR analysis of NTPD1, NTPD2, and CD73 relative expression was performed and the values were showed as ΔCq relative expression in relation to GAPDH in EPC2 and KYSE450 cell lines. The significance was described as **p < 0.01 and ***p < 0.001 and indicated difference in relation to EPC2 cell line. b Evaluation of enzymatic activity as described in “Material and Methods” section. *P < 0.05 and indicated difference in relation to ADP hydrolysis. c Cell counting of KYSE450 after 48 h under treatment with apyrase (2 U/mL) and ATP 5 mM. ***P < 0.001 indicated difference of control and #p < 0.05 indicated difference of ATP treatment. d Cell viability assays performed after 24 h under treatment with adenosine and *p < 0.05 indicated difference of control. All experiments were performed three times in triplicate

Moreover, ESCC cell lines presented an elevated expression of CD73 when compared to EPC2 cells (Fig. 7a and S2A), and this enzyme is active to hydrolyze AMP (Fig. 7b and S2B). It is known that CD73 is very important into the final step of extracellular ATP catabolism [58], mainly to produce extracellular adenosine which is presented to be very important to favoring cancer cell progression [59]. Here, we showed that adenosine, a P1R agonist, also can favor the KYSE450 ESCC cell line, to increase the cell viability at 10 μM (Fig. 7d). On the other hand, either adenosine (50, 100 μM) or caffeine (50, 100, 150 μM) (data not shown) altered proliferation in the esophageal lineage studied.

Discussion

The understanding of purinergic signaling in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma is important to set up opportunities for treating this type of tumor, as ATP is actively released in the extracellular tumor microenvironment in response to tissue damage and cellular stress [37–40]. Concomitantly, a wide range of chemotherapeutic agents and radiation cell exposition can also liberate high amounts of ATP into the extracellular space [41, 42]. Importantly, the final outcome of ATP, whether it will turn out to be beneficial or detrimental for the host, depends on the ATP concentration, the panel of purinergic receptors expressed on the tumor and infiltrating inflammatory cells, and the degradation rate of the nucleotide-hydrolyzing enzymes (E-NTPDases and CD73) [14]. Our hypothesis was that P2X7 receptor activation by ATP at high concentrations could inhibit human esophageal cancer cell proliferation.

The data showed herein demonstrated that ATP (1, 3, and 5 mM) treatment reduced KYSE30, KYSE450, and OE21 cell number, cell viability, and the formation of polyclonal colonies. These results are in accordance to previous published studies suggesting that ATP in high concentrations can produce cancer cell cytotoxicity [25, 26], mainly by stimulating P2X receptors [28, 29].

Interestingly, our study showed that high ATP concentrations diminished cell migration on the esophageal cancer cells analyzed in a scratch-wound migration assay. Several studied using pharmacological approaches suggested an important role of P2X7 in cancer cell migration/invasion, in different types of cancer [60–62]. In fact, it was previously shown that the P2X7R is involved in invasive properties related to the activation of Ca(2+)-activated SK3 potassium channels. The effect of P2X7 on cancer cells invasion was also associated to the increase of cysteine cathepsins in the extracellular medium [63].

Subsequently, we analyzed P2X receptor profile expressed on human ESCC cell lines. P2X3R, P2X4R, P2X5R, P2X6R, and P2X7R were expressed in all ESCC cells, while only the KYSE30 and KYSE450 presented P2X1R expression, and only KYSE450 expressed P2X2R. The different purinergic receptor subtypes expressed by cancer cells with widely diverse affinity confer to purinergic signaling an amazing plasticity [44]. P2X7R has several features that distinguish it from other members of the family of P2X receptors [35, 40], making this the most studied purinergic receptor in oncology. In fact, in order to understand the effects of ATP in ESCC, we further identified and compared P2X7R expression in ESCC to normal cells. In agreement with previous literature reports that have shown P2X7R expression in several cancers including glioma [26], neuroblastoma [19], osteosarcoma [20], squamous cell carcinoma of the skin [21], prostate carcinoma [22], and melanoma [23], our data showed that KYSE30, KYSE450, and OE21 cell lines expressed differently the P2X7R. Besides, EPC2 esophageal normal cells showed lower expression of P2X7R when compared to cancer cells. Hence, as we observed that high ATP concentrations reduced ESCC cell proliferation, we further investigated whether ATP cytotoxicity was mediated by P2X7R. To achieve this goal, we carried out pharmacological experiments with purinergic receptor antagonists. Important evidence confirming our hypothesis was the ability of the selective P2X7 antagonist A740003 to block the effect of ATP (5 mM). The other nonspecific antagonists (suramin and PPADS) were not able to revert ATP effect, indicating that, at least in the cells tested, the effects observed are due to the activation of ATP-P2X7R. On the other hand, previous study has shown that ATP (IC50 = 450 + 31 mM) inhibited cell proliferation in the esophageal cell lineage Kyse-140, and this effect was related to P2Y2 receptors [66]. Currently, there is a discrepancy regarding the ATP-P2X7R role in cancer cells which is probably due to different P2 receptor expression levels in the cancer cells and their different functionality [18, 64].

We also silenced P2X7R on KYSE450 cells (KYSE450 siP2X7R) and treatment of KYSE450 siP2X7R cells with ATP led to no significant changes on cell viability, showing that ATP-induced cytotoxicity through P2X7R pathway. Two opposite hypotheses have been proposed concerning the involvement of P2X7R in tumor progression. Whether the ATP/P2X7R pathway exerts a suppressive or enhancing tumor effect is still controversial [27, 44]. One possible explanation for resistance to cell death induced via ATP/P2X7R can be a mutation/truncation in the C-terminal region (P2X7B receptor), which plays a crucial role on the pore formation, and apoptosis induction [45–47]. Another explanation is based on the fact that during ATP/P2X7R-induced cytotoxicity, some accessory proteins that are required for mediating the toxic effects of ATP, such as pannexin, are missing [25]. However, many studies have shown that the stimulation of P2X7R with high ATP concentrations provokes a strong cytotoxic response in cancer cell lines that express high levels of P2X7R that have a good P2X7R pore capacity and/or present the full-length P2X7R isoform [25, 26, 48–51]. Furthermore, cancer cells can utilize extracellular ATP-P2X7R pathway in different scenarios: (a) extracellular ATP can be perceived as a death-related signal, then cancer cells could downregulate P2X7R expression to avoid apoptosis and continue growing in an ATP rich microenvironment or (b) cancer cells could use ATP as an invasion-promoting signal in order to escape this microenvironment, survive, and colonize new niches [52]. Interestingly, we also observed that KYSE450 siP2X7 cells acquired an accelerated growth rate when compared to KYSE450 GFP−/− cells, suggesting that P2X7R modulates cell death. These data are in agreement with other studies showing that P2X7R downregulation may promote lung tumor progression [51] and P2X7R suppression using shRNA exerts a promoting effect on glioma growth in vivo, which was related to upregulated EGFR, HIF-1α, and VEGF expression [28]. Interestingly, immunohistochemical analysis showed marked cytosol and nuclear immunoreactivity for P2X7R in ESCC in the tumoral and adjacent tissues, while the immunoreactive P2X7R receptors in normal tissue area showed marked nuclear positivity just in nuclei. The increased expression of P2X7 receptors in both tissues could be related to the inflammatory process and was previously described in other cancer types [49, 53]. It is relevant to note that inflammatory reaction is a histological feature characteristic of esophagitis and also described in several different cancer types, including ESCC [54, 55].

Accordingly, this study also characterized human ESCC cell lines regarding the E-NTPDase1, E-NTPDase2 and CD73 expression and activity, as well as the correlation with the expression of P2X7R receptor profile in these lineages. We showed, for the first time, that all ESCC cell lines express significant levels of E-NTPD1, E-NTPD2, and CD73 enzymes. It is known that E-NTPDase1 hydrolyzes ATP and ADP equally well; moreover, it hydrolyzes ATP almost directly to AMP with the transient production of minor amounts of free ADP. In contrast, ADP is released upon ATP hydrolysis by E-NTPDase2, then accumulates and it is slowly dephosphorylated to AMP [43]. In addition, EPC2 esophageal normal cells show lower expression of all enzymes evalutared here, when compared to cancer cells. Furthermore, we analyzed the enzymatic activity of E-NTPDase1, E-NTPDase2 and CD73 through the hydrolysis rate of ATP, ADP, and AMP. The ESCC cell lines studied presented a higher ATPase than ADPase activity, most likely because these cells express more E-NTPD1 than E-NTPD2 and thus hydrolyze more efficiently ATP than ADP. One could infer that the elevated ATP hydrolysis might be acting as a defense mechanism of ESCC cells against the cytotoxic effect of ATP-P2X7R. The ESCC lineages also presented high AMPase activity. The profile of AMP hydrolysis is in accordance of CD73 expression, and we suggested that this enzyme is responsible to the hydrolysis of this nucleotide. CD73 is very well characterized in different types of malignant tumors mainly by producing adenosine that stimulates cancer cell progression [15]. Furthermore, in this study, we have shown that the co-treatment of ATP plus apyrase has reverted the inhibitory effect of ATP 5 mM, demonstrating that the reduction observed on esophageal cancer cell proliferation is due to ATP and not to its degradation products. So, we could assume that when there are high ATP levels, which are cytotoxic to the ESCC cells through P2X7R activation, this nucleotide can be depleted by a cascade of ectonucleotidases. The same pattern of nucleotide hydrolysis was observed in T24 bladder cancer cell line [65].

In conclusion, we showed that treatment with extracellular ATP activates P2X7 receptor leading to the decrease of cell proliferation and migration, and it is tempting to suggest that P2X7R activation could represent a potential therapeutic alternative for ESCC treatment. Furthermore, our study showed, for the first time, that human ESCC cell lines express E-NTPD1 and 2 and CD73 and activity of these enzymes and revealed the P2X receptor profile expressed by these cancer cells. Moreover, a better understanding of the context of ATP signaling in esophageal cancer can be used to develop and/or to improve therapies for ESCC.

Electronic supplementary material

ATP reduces the cell migration in KYSE450 cancer cell line. (A) Representative images of ATP treatments at various times after monolayer wounding. (B) Quantification of cell migration assays. The means shown were obtained from 10 measurements of each time point and condition. The experiment was performed two times in triplicate. (TIFF 10159 kb)

Evaluation of E-NTPDases and CD73 expression and activity in EPC2, KYSE30, and OE21 esophageal cancer cell line. (A) RT-qPCR analysis of NTPD1, NTPD2, and CD73 relative expression was performed and the values were showed as ΔCq relative expression in relation to GAPDH in EPC2, KYSE30, and OE21 cancer cell lines. The significance was described as **p < 0.01 and ***p < 0.001 and indicate difference in relation to EPC2 cell line and #p < 0.05 and ###p < 0.001 indicating difference of KYSE30. (B) Evaluation of enzymatic activity as described in “Material and Methods” section. *P < 0.05 and indicate difference in relation to ADP hydrolysis. (TIFF 7227 kb)

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by CAPES and CNPq scholarships, PUCRS, and FINEP research grant “Implantação, Modernização e Qualificação de Estrutura de Pesquisa da PUCRS” (PUCRSINFRA) no. 01.11.0014-00. We would like to thank Dr. Guido Lenz from UFRGS for P2X7R antibody donation, Dr. Mohamed I Parker from ICGEB, Dr. Ana Maria O. Battastini from UFRGS, and Dr. Maria Martha Campos from PUCRS for their intellectual and technical advice.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflicts of interest

André A Santos Jr declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Angélica R Cappellari declares that she has no conflict of interest.

Fernanda O de Marchi declares that she has no conflict of interest.

Marina P Gehring declares that she has no conflict of interest.

Aline Zaparte declares that she has no conflict of interest.

Caroline A Brandão declares that she has no conflict of interest.

Tiago Giuliani Lopes declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Luis Felipe Ribeiro Pinto that he has no conflict of interest.

Vinicius Duval da Silva declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Robson Coutinho-Silva declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Juliano D Paccez declares that she has no conflict of interest.

Luiz F Zerbini declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Fernanda B Morrone declares that she has no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

Histological samples of human ESCC and esophageal tissue samples of patients with esophagitis were collected, between July and December 2015, from patients who underwent endoscopic procedures with biopsies and/or surgical resection at Pontificia Universidade Católica do Rio Grande do Sul (PUCRS, Porto Alegre, Brazil). The diagnosis was reviewed by two certified pathologists with at least 20-year experience in surgical pathology. Samples were obtained in accordance with approved ethical standards of the Institutional Research Ethics Committee (CAAE 4969 6115.0.0000.5336).

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s11302-017-9559-2) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

References

- 1.Zhang Y, Pan T, Zhong X, Cheng C. Nicotine upregulates microRNA-21 and promotes TGF-beta-dependent epithelial-mesenchymal transition of esophageal cancer cells. Tumour Biol. 2014;35(7):7063–7072. doi: 10.1007/s13277-014-1968-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Instituto Nacional de Câncer José de Alencar Gomes da Silva (2015) Estimate (2016) - Cancer Incidence in Brazil. Rio de Janeiro, INCA

- 3.Dawsey SM, Fagundes RB, Jacobson BC, Kresty LA, Mallery SR, Paski S, van den Brandt PA. Diet and esophageal disease. Ann N Y AcadSci. 2014;1325:127–137. doi: 10.1111/nyas.12528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morita M, Kumashiro R, Kubo N, Nakashima Y, Yoshida R, Yoshinaga K, Saeki H, Emi Y, KakejiY SY, Toh Y, Maehara Y. Alcohol drinking, cigarette smoking, and the development of squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus: epidemiology, clinical findings, and prevention. Int J ClinOncol. 2010;15(2):126–134. doi: 10.1007/s10147-010-0056-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Verschuur EM, Siersema PD. Diagnostics and treatment of esophageal cancers. NedTijdschrTandheelkd. 2010;117(9):427–431. doi: 10.5177/ntvt.2010.09.10128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dandara C, Li DP, Walther G, Parker MI. Gene-environment interaction: the role ofSULT1A1 and CYP3A5 polymorphisms as risk modifiers for squamous cell carcinoma of the oesophagus. Carcinogenesis. 2006;27(4):791–797. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgi257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Ervik M, (2013) GLOBOCAN 2012 cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: IARC cancer base no. 11. International Agency for Research on Cancer. Accessed Jan 2016

- 8.Rubenstein JH, Shaheen NJ. Epidemiology, diagnosis, and management of esophageal adenocarcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2015;149(2):302–317. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.04.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Siewert JR, Stein HJ, Feith M, Bruecher BL, Bartels H, Fink U. Histologic tumor type is an independent prognostic parameter in esophageal cancer: lessons from more than 1,000 consecutive resections at a single center in the Western world. Ann Surg. 2001;234(3):360–367. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200109000-00010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang Y. Epidemiology of esophageal cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19(34):5598–5606. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i34.5598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wu L, Herman JG, Brock MV, Wu K, Mao G, Yan W, Nie Y, Liang H, Zhan Q, Li W, Guo M. Silencing DACH1 promotes esophageal cancer growth by inhibiting TGF-beta signaling. PLoS One. 2014;9(4):e95509. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0095509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yao R, Chen Z, Zhou C, Luo M, Shi X, Li J, Gao Y, Zhou F, Pu J, Sun H, He J. Xerophilusin B induces cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma cells and does not cause toxicity in nude mice. J Nat Prod. 2015;78(1):10–16. doi: 10.1021/np500429w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xue L, Yang L, Jin ZA, Gao F, Kang JQ, Xu GH, Liu B, Li H, Wang XJ, Liu LJ, Wang BL, Liang SH, Ding J. Increased expression of HSP27 inhibits invasion and metastasis in human esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. TumourBiol. 2014;35(7):6999–7007. doi: 10.1007/s13277-014-1946-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Di Virgilio F. Purines, purinergic receptors, and cancer. Cancer Res. 2012;72(21):5441–5447. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-1600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Burnstock G, Di Virgilio F. Purinergic signalling and cancer. Purinergic Signal. 2013 doi: 10.1007/s11302-013-9372-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bastid J, Regairaz A, Bonnefoy N, Dejou C, Giustiniani J, Laheurte C, Cochaud S, Laprevotte E, Funck-Brentano E, Hemon P, Gros L, Bec N, Larroque C, Alberici G, Bensussan A, Eliaou JF. Inhibition of CD39 enzymatic function at the surface of tumor cells alleviates their immunosuppressive activity. Cancer immunology research. 2015;3(3):254–265. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-14-0018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.White N, Burnstock G. P2 receptors and cancer. Trends PharmacolSci. 2006;27(4):211–217. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2006.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Di Virgilio F, Ferrari D, Adinolfi E. P2X(7): a growth-promoting receptor-implications for cancer. Purinergic Signal. 2009;5(2):251–256. doi: 10.1007/s11302-009-9145-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Larsson KP, Hansen AJ, Dissing S. The human SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cell-line expresses a functional P2X7 purinoceptor that modulates voltage-dependent Ca2+ channel function. J Neurochem. 2002;83(2):285–298. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2002.01110.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gartland A, Hipskind RA, Gallagher JA, Bowler WB. Expression of a P2X7 receptor by a subpopulation of human osteoblasts. J Bone Miner Res. 2001;16(5):846–856. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2001.16.5.846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Greig AV, Linge C, Healy V, Lim P, Clayton E, Rustin MH, McGrouther DA, Burnstock G. Expression of purinergic receptors in non-melanoma skin cancers and their functional roles in A431 cells. J Invest Dermatol. 2003;121(2):315–327. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2003.12379.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Calvert RC, Shabbir M, Thompson CS, Mikhailidis DP, Morgan RJ, Burnstock G. Immunocytochemical and pharmacological characterisation of P2-purinoceptor-mediated cell growth and death in PC-3 hormone refractory prostate cancer cells. Anticancer Res. 2004;24(5A):2853–2859. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Slater M, Scolyer RA, Gidley-Baird A, Thompson JF, Barden JA. Increased expression of apoptotic markers in melanoma. Melanoma Res. 2003;13(2):137–145. doi: 10.1097/00008390-200304000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Roger S, Jelassi B, Couillin I, Pelegrin P, Besson P, Jiang LH. Understanding the roles of the P2X7 receptor in solid tumour progression and therapeutic perspectives. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2015;1848(10 Pt B):2584–2602. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2014.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tamajusuku AS, Villodre ES, Paulus R, Coutinho-Silva R, Battasstini AM, Wink MR, Lenz G. Characterization of ATP-induced cell death in the GL261 mouse glioma. J Cell Biochem. 2010;109(5):983–991. doi: 10.1002/jcb.22478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gehring MP, Pereira TC, Zanin RF, Borges MC, Filho AB, Battastini AM, Bogo MR, Lenz G, Campos MM, Morrone FB. P2X7 receptor activation leads to increased cell death in a radiosensitive human glioma cell line. Purinergic Signal. 2012;8(4):729–739. doi: 10.1007/s11302-012-9319-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.White N, Butler PE, Burnstock G. Human melanomas express functional P2X(7)receptors. Cell Tissue Res. 2005;321(3):411–418. doi: 10.1007/s00441-005-1149-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fang J, Chen X, Zhang L, Chen J, Liang Y, Li X, Xiang J, Wang L, Guo G, Zhang B, Zhang W. P2X7R suppression promotes glioma growth through epidermal growth factor receptor signal pathway. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2013;45(6):1109–1120. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2013.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang Q, Wang L, Feng YH, Li X, Zeng R, Gorodeski GI. P2X7 receptor-mediated apoptosis of human cervical epithelial cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2004;287(5):C1349–C1358. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00256.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ryu JK, Jantaratnotai N, Serrano-Perez MC, McGeer PL, McLarnon JG. Block ofpurinergic P2X7R inhibits tumor growth in a C6 glioma brain tumor animal model. Journal ofneuropathology and experimental neurology. 2011;70(1):13–22. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0b013e318201d4d4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Adinolfi E, Capece M, Franceschini A, Falzoni S, Giuliani AL, Rotondo A, Sarti AC, Bonora M, Syberg S, Corigliano D, Pinton P, Jorgensen NR, Abelli L, Emionite L, Raffaghello L, Pistoia V, DiVirgilio F. Accelerated tumor progression in mice lacking the ATP receptor P2X7. Cancer Res. 2015;75(4):635–644. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-1259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Giannuzzo A, Pedersen SF, Novak I. The P2X7 receptor regulates cell survival, migration and invasion of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma cells. Mol Cancer. 2015;14(1):203. doi: 10.1186/s12943-015-0472-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vazquez-Cuevas FG, Martinez-Ramirez AS, Robles-Martinez L, Garay E, Garcia-Carranca A, Perez-Montiel D, Castaneda-Garcia C, Arellano RO. Paracrine stimulation of P2X7 receptor by ATP activates a proliferative pathway in ovarian carcinoma cells. J Cell Biochem. 2014;115(11):1955–1966. doi: 10.1002/jcb.24867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chan KM, Delfert D, Junger KD. A direct colorimetric assay for Ca2+-stimulated ATPase activity. Anal Biochem. 1986;157(2):375–380. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(86)90640-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kim M, Jiang LH, Wilson HL, North RA, Surprenant A. Proteomic and functional evidence for a P2X7 receptor signalling complex. EMBO J. 2001;20(22):6347–6358. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.22.6347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ralevic V, Burnstock G. Receptors for purines and pyrimidines. Pharmacol Rev. 1998;50(3):413–492. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pellegatti P, Raffaghello L, Bianchi G, Piccardi F, Pistoia V, Di Virgilio F. Increased level of extracellular ATP at tumor sites: in vivo imaging with plasma membrane luciferase. PLoS One. 2008;3(7):e2599. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Quail DF, Joyce JA. Microenvironmental regulation of tumor progression and metastasis. Nat Med. 2013;19(11):1423–1437. doi: 10.1038/nm.3394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Michaud M, Martins I, Sukkurwala AQ, Adjemian S, Ma Y, Pellegatti P, Shen S, Kepp O, Scoazec M, Mignot G, Rello-Varona S, Tailler M, Menger L, Vacchelli E, Galluzzi L, Ghiringhelli F, di Virgilio F, Zitvogel L, Kroemer G. Autophagy-dependent anticancer immune responses induced by chemotherapeutic agents in mice. Science. 2011;334(6062):1573–1577. doi: 10.1126/science.1208347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stagg J, Smyth MJ. Extracellular adenosine triphosphate and adenosine in cancer. Oncogene. 2010;29(39):5346–5358. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Martins I, Tesniere A, Kepp O, Michaud M, Schlemmer F, Senovilla L, Seror C, Metivier D, Perfettini JL, Zitvogel L, Kroemer G. Chemotherapy induces ATP release from tumor cells. Cell Cycle. 2009;8(22):3723–3728. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.22.10026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ohshima Y, Tsukimoto M, Takenouchi T, Harada H, Suzuki A, Sato M, Kitani H, Kojima S. Gamma-irradiation induces P2X(7) receptor-dependent ATP release from B16 melanoma cells. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1800(1):40–46. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2009.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Robson SC, Sevigny J, Zimmermann H. The E-NTPDase family of ectonucleotidases: structure function relationships and pathophysiological significance. Purinergic Signal. 2006;2(2):409–430. doi: 10.1007/s11302-006-9003-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.North RA. Molecular physiology of P2X receptors. Physiol Rev. 2002;82(4):1013–1067. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00015.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bianco F, Colombo A, Saglietti L, Lecca D, Abbracchio MP, Matteoli M, Verderio C. Different properties of P2X(7) receptor in hippocampal and cortical astrocytes. Purinergic Signal. 2009;5(2):233–240. doi: 10.1007/s11302-009-9137-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cheewatrakoolpong B, Gilchrest H, Anthes JC, Greenfeder S. Identification and characterization of splice variants of the human P2X7 ATP channel. Biochem Biophys ResCommun. 2005;332(1):17–27. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.04.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Adinolfi E, Cirillo M, Woltersdorf R, Falzoni S, Chiozzi P, Pellegatti P, Callegari MG, Sandona D, Markwardt F, Schmalzing G, Di Virgilio F. Trophic activity of a naturally occurring truncated isoform of the P2X7 receptor. FASEB J. 2010;24(9):3393–3404. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-153601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Di Virgilio F, Chiozzi P, Falzoni S, Ferrari D, Sanz JM, Venketaraman V, Baricordi OR. Cytolytic P2X purinoceptors. Cell Death Differ. 1998;5(3):191–199. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gehring MP, Kipper F, Nicoletti NF, Sperotto ND, Zanin R, Tamajusuku AS, Flores DG, Meurer L, Roesler R, Filho AB, Lenz G, Campos MM, Morrone FB. P2X7 receptor as predictor gene for glioma radiosensitivity and median survival. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2015;68:92–100. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2015.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ghiringhelli F, Apetoh L, Tesniere A, Aymeric L, Ma Y, Ortiz C, Vermaelen K, Panaretakis T, Mignot G, Ullrich E, Perfettini JL, Schlemmer F, Tasdemir E, Uhl M, Genin P, Civas A, Ryffel B, Kanellopoulos J, Tschopp J, Andre F, Lidereau R, McLaughlin NM, Haynes NM, Smyth MJ, Kroemer G, Zitvogel L. Activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome in dendritic cells induces IL-1beta-dependent adaptive immunity against tumors. Nat Med. 2009;15(10):1170–1178. doi: 10.1038/nm.2028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Boldrini L, Giordano M, Ali G, Melfi F, Romano G, Lucchi M, Fontanini G. P2X7 mRNA expression in non-small cell lung cancer: microRNA regulation and prognostic value. Oncol Lett. 2015;9(1):449–453. doi: 10.3892/ol.2014.2620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Roger S, Pelegrin P. P2X7 receptor antagonism in the treatment of cancers. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2011;20(7):875–880. doi: 10.1517/13543784.2011.583918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kwon JH, Nam ES, Shin HS, Cho SJ, Park HR, Kwon MJ. P2X7 receptor expression in coexistence of papillary thyroid carcinoma with Hashimoto's thyroiditis. Korean J Pathol. 2014;48(1):30–35. doi: 10.4132/KoreanJPathol.2014.48.1.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lin EW, Karakasheva TA, Hicks PD, Bass AJ, Rustgi AK. The tumor microenvironment in esophageal cancer. Oncogene. 2016 doi: 10.1038/onc.2016.34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.O'Sullivan KE, Phelan JJ, O'Hanlon C, Lysaght J, O'Sullivan JN, Reynolds JV. The role of inflammation in cancer of the esophagus. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;8(7):749–760. doi: 10.1586/17474124.2014.913478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Valster A, Tran NL, Nakada M, Berens ME, Chan AY, Symons M. Cell migration and invasion assays. Methods. 2005;37:208–215. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2005.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Welter-Stahl L, Silva CM, Schachter J, Persechini PM, Soza HS, Ojcius DM, Coutinho-Silva R. Expression of purinergic receptors and modulation of P2X7 function by the inflammatory cytokine IFNY in human epithelial cells. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1788:1176–1187. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2009.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yegutkin GG. Nucleotide- and nucleoside-converting ectoenzymes: important modulators of purinergic signaling cascade. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1783:673–694. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2008.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Spychala J. Tumor-promoting functions of adenosine. Pharmacological & Therapeutics. 2000;87:161–173. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(00)00053-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wei W, Ryu JK, Choi HB, McLarmon JG. Expression and function of the P2X7 receptor in rat C6 glioma cells. Cancer Lett. 2008;260(1):79–78. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2007.10.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Jelassi B, Anchelin M, Chamouton J, Cayuela ML, Clarysse L, Li J, Goré J, Jiang LH, Roger S. Anthraquinone emodin inhibits human cancer cell invasiveness by antagonizing P2X7 receptors. Carcinogenesis. 2013;34(7):1487–1496. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgt099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ghalali A, Wiklund F, Zheng H, Stenius U, Högberg J. Atorvastatin prevents ATP-driven invasiveness via P2X7 and EHBP1 signaling in PTEN-expressing prostate cancer cells. Carcinogenesis. 2014;35(7):1547–1555. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgu019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Jelassi B, Chantôme A, Alcaraz-Pérez F, Baroja-Mazo A, Cayuela ML, Pelegrin P, Surprenant A, Roger S. P2X(7) receptor activation enhances SK3 channels- and cystein cathepsin-dependent cancer cells invasiveness. Oncogene. 2011;30(18):2108–2122. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Morrone FB, Gehring MP, Nicoletti Natália F. Calcium channels in malignant brain tumors. Mol Pharmacol. 2016;90(3):403–409. doi: 10.1124/mol.116.103770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Stella J, Bavaresco L, Braganhol E, Rockenbach L, Farias PF, Wink M, Azambuja AA, Barrios CH, Morrone FB, Battastini AMO. Differential ectonucleotidase expression in human bladder cancer cell lines. Urology Oncology. 2010;28:260–267. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2009.01.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Maaser K, Höpfner M, Kap H, Sutter AP, Barthel B, von Lampe B, Zeitz M, Scherübl H. Extracellular nucleotides inhibit growth of human oesophageal cancer cells via P2Y(2)-receptors. Br Jn. 2002;86(4):636–644. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

ATP reduces the cell migration in KYSE450 cancer cell line. (A) Representative images of ATP treatments at various times after monolayer wounding. (B) Quantification of cell migration assays. The means shown were obtained from 10 measurements of each time point and condition. The experiment was performed two times in triplicate. (TIFF 10159 kb)

Evaluation of E-NTPDases and CD73 expression and activity in EPC2, KYSE30, and OE21 esophageal cancer cell line. (A) RT-qPCR analysis of NTPD1, NTPD2, and CD73 relative expression was performed and the values were showed as ΔCq relative expression in relation to GAPDH in EPC2, KYSE30, and OE21 cancer cell lines. The significance was described as **p < 0.01 and ***p < 0.001 and indicate difference in relation to EPC2 cell line and #p < 0.05 and ###p < 0.001 indicating difference of KYSE30. (B) Evaluation of enzymatic activity as described in “Material and Methods” section. *P < 0.05 and indicate difference in relation to ADP hydrolysis. (TIFF 7227 kb)