Abstract

Histotripsy, a form of therapeutic ultrasound that uses the mechanical action of microbubble clouds for ablation lysis, is under development to treat chronic deep vein thrombosis (DVT). We hypothesize that combining thrombolytic agents with histotripsy will enhance clot lysis. Recombinant tissue plasminogen activator (rt-PA) and rt-PA-loaded echogenic liposomes that entrain octafluoropropane microbubbles (OFP t-ELIP) were used in combination with highly shocked histotripsy pulses. Fully retracted porcine venous clots, with similar features of DVT occlusions, were exposed either to histotripsy pulses alone (peak negative pressures of 7–20 MPa), histotripsy and OFP t-ELIP, or histotripsy and rt-PA. Microbubble cloud activity was monitored with passive cavitation imaging during histotripsy exposure. The power levels of cavitation emissions from within the clot were not statistically different between treatment types, likely due to the near instantaneous rupture and deletion of OFP t-ELIP. The thrombolytic efficacy was significantly improved in the presence of rt-PA. These results suggest the combination of histotripsy and rt-PA could serve as a potent therapeutic strategy for the treatment of DVT.

Keywords: Histotripsy, Deep vein thrombosis, Passive cavitation imaging, Echogenic liposomes

Introduction

Deep vein thrombosis (DVT) is a major public health problem, affecting 5% of the population (Wells et al 2014) with an estimated $10 billion healthcare cost in the United States (Grosse 2012). The standard of care for DVT is anticoagulation therapy (Beckman et al 2010). Acute thrombus formation can occur in hypercoagulable patients (Patel et al 2000). The most severe acute consequence of DVT is phlegmasia cerulea dolens, a critical obstruction of iliofemoral venous return, which is prevalent in 4% of DVT patients (Lin et al 2005, Oguzkurt et al 2011). Clinical presentation of phlegmasia cerulea dolens requires amputation in 15% of patients due to venous gangrene (Patel et al 1998), and has a 25% mortality rate (Lin et al 2005, Hood et al 1993). For critical venous obstructions, catheter-directed thrombolytic drugs (Augustinos 2004) are the frontline therapy for recanalization (Kalagher and Kane 2014). However, thrombi formed in the deep veins have chronic components that are fibrous and stiff (Hirsh and Hoak 1996), retracted (Strandness and Van Breda 1994), and unresponsive to thrombolytic drugs (Weisel 2007). Mechanical embolectomy as an adjuvant to catheter-directed thrombolytics has also been employed for the treatment of DVT (Mumoli et al 2012). Chronic thrombi can fragment during mechanical embolectomy (Marder et al 2006, Worku et al 2015, Kassas 2013), causing incomplete thrombus removal (Donaldson et al 2015), pulmonary embolization, and a high likelihood of re-thrombosis (Watson et al 2009). Improved clinical outcomes and a reduction in re-thrombosis are associated with the complete removal of the thrombus (Avgerinos et al 2015, Gibson et al 2014, Aziz and Comerota 2012).

Histotripsy is a form of therapeutic ultrasound that employs the mechanical action of microbubble clouds to ablate tissue (Xu et al 2006), including thrombi (Zhang et al 2015b). The development of histotripsy to ablate thrombi appears promising in vitro (Maxwell et al 2009). Recanalization with histotripsy was demonstrated successfully in only 7 of 12 thrombi in a porcine femoral DVT model in vivo (Maxwell et al 2011a). Residual thrombus is associated with increased rates of post thrombotic syndrome (Avgerinos et al 2015), and reoccurrence of thrombus formation in DVT (Watson et al 2009). Histotripsy as a stand-alone therapy neglects the known synergy between ultrasound and thrombolytic drugs (Bader et al 2015a). The addition of a thrombolytic would further break down thrombus debris generated during the histotripsy ablation, minimizing the potential for pulmonary embolism or thrombogenic particulates.

Echogenic liposomes (ELIP) have previously been developed as a carrier for therapeutic drugs (Laing et al 2012). Thrombolytic-loaded ELIP (t-ELIP) target fibrin (Tiukinhoy-Laing et al 2007), and can be acoustically activated for localized drug delivery (Shaw et al 2009a, Smith et al 2010). Encapsulation of the thrombolytic drug recombinant tissue plasminogen activator (rt-PA) may reduce systemic toxicity compared to direct intravenous injection (Turi et al 1993), and protect rt-PA from plasminogen activator inhibitors present in vivo (Shaw et al 2007). Gas microbubbles entrained within ELIP can act as cavitation nuclei (Bader et al 2015b), and may serve as sites for shockwave scattering to initiate microbubble cloud formation (Tran et al 2005).

The objective of this study is to determine the thrombolytic efficacy of histotripsy in combination with rt-PA or t-ELIP for simultaneous mechanical ablation and enzymatic lysis of venous porcine clots in vitro. A new formulation of t-ELIP encapsulating octafluoropropane (OFP) gas microbubbles was employed. This high molecular weight gas is thought to promote sustained microbubble activity for ultrasound enhancement of thrombolysis (Bader et al 2015b). The number density, shell properties, and enzymatic activity of rt-PA-loaded echogenic liposomes entrained with OFP microbubbles, OFP t-ELIP, were characterized. Thrombolytic efficacy for ablation of venous porcine blood clots was evaluated with and without OFP t-ELIP or with and without rt-PA. The spatial location and power of cavitation activity were gauged using passive cavitation imaging (Haworth et al 2012, Gyöngy et al 2008, Salgaonkar et al 2009). Finally, the expansion of OFP t-ELIP under excitation by a histotripsy pulse was investigated by numerical integration of the Marmottant model (Marmottant et al 2005a) and compared to an analytic model for endogenous cavitation nuclei (Bader and Holland 2016).

Materials and Methods

Venous clot formation

Porcine venous blood was collected aseptically from donor hogs (Lampire Biologicals, Pipersville, PA USA), anticoagulated with a citrate-phosphate-dextrose solution (final concentrations in blood: 16.1 mM sodium citrate, 17.6 mM D-glucose, 1.96 mM citric acid, and 2.3 mM NaH2PO4) and shipped on ice overnight to the University of Cincinnati. Before coagulation, the blood was incubated at 37.3°C for 20 min while exposed to room air to equilibrate gas content, as confirmed with a dissolved oxygen meter (DO110, Oakton Instruments, Vernon Hills, IL USA). The blood was recalcified with CaCl2 to a final concentration of 16.1 mM and mixed with BaSO4 (11.1% w/v), a radio-opaque agent that allows for visualization of the clot under computed tomography angiography. The blood/BaSO4 solution was pipetted into a borosilicate glass Pasteur pipet (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA USA) primed with bovine thrombin (13.2% v/v). The pipets were incubated at 37.3°C for 3 hours during coagulation, and placed in a laboratory refrigerator at 4°C for a minimum of 3 days before experimental treatment to allow for consistent clot retraction. The clot diameter was 4.05 ± 0.35 mm, and clots were cut to 1 cm length prior to treatment. These methods of clot formation were similar to those implemented in other thrombolysis studies (Sutton et al 2013, Datta et al 2006, Holland et al 2008, Hitchcock et al 2011). Furthermore, rt-PA lytic efficacy of these fully retracted clots was limited (9.4 ± 1.5 % mass loss), similar to the chronic thrombi found in DVT.

Preparation of recombinant tissue plasminogen activator

Recombinant tissue-type plasminogen activator (rt-PA) was obtained from the manufacturer (Activase®, Genentech, San Fransisco, CA, USA) as lyophilized powered. Each vial was mixed with sterile water to a concentration of 1 mg/mL per manufacturer instructions, aliquoted into 1.0 mL centrifuge tubes, and stored at −80 °C. The enzymatic activity of rt-PA is stable over a period of at least 7 years using this protocol (Shaw et al 2009b).

OFP t-ELIP Formulation

Echogenic liposomes were prepared at the University of Texas Health Sciences Center (Houston, TX, USA) using methods similar to those previously reported (Laing et al 2012). The lipid composition was DPPC:DOPC:DPPG:Chol in a 46:23:23:8 molar ratio (DPPC = 1,2-dipalmitoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine; DOPC = 1,2-Dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine; DPPG = 1,2-dipalmitoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoglycerol; Chol = Cholesterol). Component lipids were dissolved in chloroform and the solution evaporated. The resulting film was placed under vacuum for complete removal of the chloroform overnight, and then rehydrated with 200 µL of rt-PA (1 mg/mL) and 300 µL of Mannitol (0.32 M) for each 5 mg of lipid. Free rt-PA was separated from the entrapped ELIP by centrifugation at 16,000 rpm for 20 min at room temperature (25°C). The resultant liposomal pellet was resuspended with 0.32 M Mannitol and kept at −70°C for 2 h. The samples were lyophilized for 48 hours and then kept at 4°C overnight. The air headspace was evacuated from vials containing the final lipid/rt-PA samples, and reloaded with 2 mL (1 atm partial pressure) of OFP.

Vials of OFP t-ELIP containing 4 mg of lipid and 160 µg of rt-PA were shipped to the University of Cincinnati on ice. Prior to reconstitution, the vials were evacuated for 60s at 10 mmHg (1.33 kPa) and filled with OFP to attain a partial pressure of 2 atm. Three hours after pressurization with OFP, a 22-gauge needle was used to equilibrate the partial pressure of OFP to 1 atm, and the OFP t-ELIP were reconstituted with 400 µL of 0.2 µm filtered, deionized, air saturated (100% dissolved oxygen) water (NANOPure, Barnstead Inernational, Dubuque, IA, USA), and diluted into porcine plasma to obtain a final lipid concentration of 1.2 mg/mL.

OFP t-ELIP Characterization

A sample of the reconstituted OFP t-ELIP suspension was diluted (1:40000 v/v) into room temperature, air-saturated phosphate-buffered saline (Sigma-Aldrich) and the size distribution was measured using an impedance-based particle sizer (Multisizer 4, Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA USA). Each measurement analyzed 100 µL of the diluted sample through a 30 µm aperture over 30 s. Each measurement produced a number density histogram, which was corrected for the amount of dilution, with bins spaced between 0.65 µm and 18 µm (0.08 µm bin size). This histogram was transformed into a volume-weighted distribution for further analysis. The results from three measurements, each using a fresh vial of OFP t-ELIP, were averaged to produce a final volume-weighted size distribution.

The frequency-dependent attenuation coefficient, α(f) in dB/cm, was determined using a broadband substitution technique as described in Raymond et al (2014). Briefly, OFP t-ELIP were diluted (1:200) into a reservoir containing aerated phosphate-buffered saline, stirred, and allowed to flow by gravity into a sample chamber with acoustically transparent polycarbonate film windows (CLINIcell 25, Mabio, Tourcoing, France). The reservoir, sample chamber, and transducers were mounted in a test tank filled with deionized water maintained at 37°C±0.5°C using a circulating water bath (Neslab EX, Newington, NH, USA). A pair of broadband transducers (PI-20, Olympus NDT, Waltham, MA, USA) were used to acquire the through-transmission spectrum over the frequency range 2–25 MHz (31 kPa peak negative pulse pressure). The attenuation spectrum was computed from the received amplitude spectra in the absence (diluent alone) and the presence of the OFP t-ELIP, respectively. Acoustic attenuation measurements were made using five separate vials of OFP t-ELIP. The elasticity and viscosity of the OFP t-ELIP shell were determined by minimizing the sum-squared difference in errors between the estimated and measured attenuation coefficients, as described in Raymond et al (2014).

The enzymatic activity of rt-PA and OFP t-ELIP were measured using a spectrophotometric method (Verheijen et al 1985). Thawed rt-PA or reconstituted OFP t-ELIP were diluted into a solution of phosphate buffer solution (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) and 1% Triton-X (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) to achieve target concentrations of rt-PA between 0.3 and 3 µg/mL in disposable cuvettes used for spectrophotometric measurement. The amount of Triton-X employed in the solution exceeded the critical micelle concentration (0.015%) (Triton-X Product Information Sheet, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) to ensure rupture of the lipid shell surrounding t-ELIP and release of the associated rt-PA. The solution with released rt-PA was subsequently diluted into a pre-warmed solution (37 °C) of 0.5% phosphate buffer solution and a chromogenic substrate (S-2288, Chromogenix, DiaPharma Group, Inc., Westchester, OH, USA). The chromogenic substrate was hydrolyzed by rt-PA and allowed spectrophotometric measurement of the change of absorbance at 405 nm over time, which was proportional to the enzymatic activity of rt-PA. A spectrophotometer (UV-1700, Shimadzu, Japan) with temperature controller (TCC-240A, Shimadzu, Japan) was used to record the absorbance of the solution over the course of 5 minutes at 37 °C. The rt-PA activity was measured in terms of the change in absorbance over time (ΔAbs/min).

Histotripsy Insonation

Histotripsy pulses were generated with a 1-MHz, 8 annular element array with a 10-cm aperture and 9-cm focal length (Imasonic, Voray sur l’Ognon, France). All elements of the transducer were simultaneously driven in parallel by a custom designed and built class D amplifier and matching network (Hall and Cain 2006). The transducer had previously been calibrated at the focus for shockwave amplitudes up to 107 MPa peak positive pressure (18.3 MPa peak negative pressure) with a fiber optic hydrophone (FOPH 2000, RP Acoustics, e.K., Leutenbach, Germany) (Bader and Holland 2016). In this study, histotripsy pulses were generated for pulse durations of 5 µs, 20 Hz pulse repetition frequency (PRF), and peak negative pressures based on the free field calibration between 7 and 20 MPa. Peak negative pressures greater than 18 MPa were estimated by an element by element calibration following Maxwell et al (2013). The pulse duration for these insonations are consistent with previous studies of clot lysis with histotripsy (Maxwell et al 2009), and the PRF is similar to that used for histotripsy insonation of exogenous cavitation nuclei (Vlaisavljevich et al 2013).

Passive Cavitation Imaging

A passive cavitation image (PCI) spatially maps a specified frequency bandwidth of acoustic emissions generated by cavitation (Salgaonkar et al 2009, Gyöngy et al 2008). Each pixel (image location) of the PCI is proportional to the power of the acoustic emissions. To form PCIs, cavitation emissions were passively recorded during the histotripsy insonation with an L7-4 imaging array (ATL, Bothell, WA, USA) using a Verasonics ultrasound research scanner (Vantage 256, Verasonics, Inc., Kirkland, WA, USA). The imaging array was oriented to monitor cavitation activity along the axial-lateral plane of the histotripsy transducer at a distance of 30 mm from the focus (see Fig. 1). Peak cavitation emissions occurred during the 5 µs insonation. Cavitation emissions were beamformed in the frequency domain using a delay, sum, and integrate method (Haworth et al 2012). Briefly, the power spectra of the passively detected emissions were computed. The frequency domain data was phase-shifted based on the time-of-flight from a location in the imaging plane to each element of the imaging array. The phase-shifted data was then summed over each element of the array. The frequency-dependent power in the summed waveform was computed and used to assign pixel values in the PCI. The magnitude of the pixel was proportional to the averaged acoustic power received in the frequency range of interest with units of mV2. The cavitation emissions generated by the histotripsy-induced microbubble clouds were observed to have a broad frequency spectrum (Fig. 2). Thus, the recorded spectra were processed between 2.5 and 8.5 MHz to generate a passive cavitation image (PCI) (Haworth et al 2012). The same L7-4 imaging array was also employed to acquire plane wave B-mode images.

Fig 1.

Overhead view of experimental set up for histotripsy ablation of porcine clots. The L7-4 imaging array was oriented to monitor cavitation activity along the axial/elevational plane of the histotripsy transducer. The elevational dimension, not shown, is perpendicular to both the lateral and axial dimensions (into the page).

Fig 2.

Representative scattered power spectra acquired from acoustic emissions generated by histotripsy-induced microbubble clouds within a porcine whole blood clot without OFP t-ELIP (a) and with OFP t-ELIP (b) (1-MHz fundamental frequency, 5 µs pulse duration, 20 Hz pulse repetition frequency). The peak negative pressures for each insonation are indicated in the legend. Each power spectra was normalized by the maximum power while insonifying with a peak negative pressure of 20 MPa either without (a) or with (b) OFP t-ELIP.

Experimental Protocol

The porcine clot was cut to 1-cm length, blotted (Sutton et al 2013), and then weighed with a laboratory balance. The clot was inserted into a 6 mm diameter, 0.1 mm thick low-density polyethylene (LDPE) tube filled with either porcine plasma alone (Lampire Biologicals, Pipersville, PA, USA), porcine plasma and OFP t-ELIP, or porcine plasma and rt-PA. The LDPE tube has an acoustic impedance similar to that of a vessel wall (Hoskins 2007, Maev 2008). The rt-PA concentration was 24 µg/mL, which is consistent with previous studies employing porcine clots for sonothrombolysis (Holland et al 2008, Datta et al 2008). The concentration of OFP t-ELIP (1.2 mg/mL lipid concentration) was adjusted to have equivalent enzymatic activity to the unencapsulated rt-PA after complete release with Triton-X. The LPDE tube was affixed to a three-axis positioning system (TDC001, Thorlabs Inc., Newton, NJ, USA) and submerged within a tank of deionized, degassed (20% dissolved oxygen), filtered (10 µm pore size) water. The water temperature was maintained at 37.3 ± 0.5°C with a custom heating system. The clot was positioned in the focus of the histotripsy transducer, such that the axis of the clot was perpendicular to the central axis of the histotripsy transducer (see Fig. 1). The clot was translated laterally in 1 mm increments, and 2000 histotripsy pulses were applied at each location (10 total locations). Cavitation emissions were passively acquired at the first insonation location with the L7-4 imaging array every fifth histotripsy pulse (400 total frames). Emissions at this location were assumed to be representative at all 10 insonation locations. A plane wave B-mode image was also acquired after passive acquisition of cavitation emissions. The total treatment time was approximately 20 min, after which the residual clot segment was removed from the tube, blotted, and then weighed. Thrombolytic efficacy of the treatment was recorded by computing the percent mass loss. In a subset of each treatment type, a 200 µL sample of porcine plasma containing clot debris, or clot debris and residual rt-PA and lipid, was collected and diluted into phosphate buffered saline (1:2000 v/v). The size distribution was measured between 0.65 µm and 18 µm using an impedance-based particle sizer (Multisizer 4, Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA, USA). Each measurement analyzed 100 µL of the diluted sample through a 30-µm aperture over 30 s. A total of 6 clots were used for each given treatment type and peak negative pressure of the histotripsy pulse (72 clots in total).

For each passively acquired cavitation data set, the emissions were processed offline to form 400 PCIs. The pixel intensity is proportional to the acoustic power. The averaged acoustic power within the clot and the location of the maximum acoustic power along the axial dimension of the histotripsy transducer were computed for each data set (N = 6). To determine the average acoustic power within the clot for a given data set, all 400 PCI frames were averaged temporally. The clot location was manually segmented based on the plane wave B-mode image (Fig. 3), and the temporally averaged PCI was integrated along the axial dimension at a fixed elevational location. The axial and elevational dimensions are in reference to the histotripsy field (Fig. 1). The acoustic power was only integrated along the axial dimension because of the limited elevational resolution of the delay, sum, and integration method (Coviello et al 2015). Within the clot, the location of the maximum acoustic power along the axial dimension of the histotripsy transducer was also recorded for each pulse, and was found to have a Gaussian distribution (p > 0.05 for Lilliefors test). The variability of the axial location of the largest PCI pixel amplitude for each data set was evaluated as the full width, half maximum of the Gaussian distribution. To maximize the dynamic range visible in Fig. 3, the color bar uses a decibel scale where 0 dB represents the maximum pixel amplitude in the PCI.

Fig 3.

(Top panel) For a given data set, all 400 PCI frames were temporally averaged (hot colormap). The axial and elevational directions are in reference to the histotripsy transducer (Fig. 1). The histotripsy pulse is propagating along the axial dimension (from left to right) in the image. The artifact along the elevational direction of the histotripsy transducer occurs because of the elongated point spread function in the direction normal to the face of the linear array (Haworth et al 2012). A duplex averaged PCI/plane wave B-mode image (grayscale) allowed comparison of the temporally averaged acoustic power with the clot. The dotted and dashed line notes the elevational position of the maximum pixel amplitude of the PCI. (Bottom panel) The temporally averaged PCI amplitude as a function of the axial dimension at a fixed elevational location (dotted and dashed line in top panel). The boundaries of the lumen are denoted in green, and the clot boundaries are noted in blue.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using the MATLAB Statistical Toolbox (The Mathworks, Natick, MA, USA). Statistical differences in means of the thrombolytic efficacy and the acoustic power within the clot, and the variability of the location of the maximum acoustic power along the axial dimension of the histotripsy source were determined by one-way unbalanced ANOVA with an α level of 0.05. Adjusted p values based on Tukey’s honest significant difference test were calculated to elucidate significant differences between the means of treatment cohorts. The correlation between the thrombolytic efficacy, acoustic power within the clot, variability of the acoustic power along the axial dimension of the histotripsy transducer, and peak negative pressure were calculated using the Pearson’s linear correlation coefficient in MATLAB® (The Mathworks, Natick, MA, USA). A p-value less than 0.05 was used as a requirement for significant correlation.

Numerically Calculated Response of OFP t-ELIP to Histotripsy Pulses

The radial oscillations of encapsulated cavitation nuclei in response to histotripsy excitation were calculated by numerical integration of the Marmottant Model (Marmottant et al 2005a). An adaptive fourth-order Runga-Kutta algorithm was implemented in MATLAB® (The Mathworks, Natick, MA, USA) to carry out the integration. The Marmottant model has the form:

| (1) |

where R is the time dependent bubble radius, the diacritic dot denotes the temporal derivative, c is the sound speed of the medium (1540 m/s), µ is the dynamic viscosity (0.005 kg/m•s (Holland and Apfel 1989)), κ is the polytropic exponent of OFP (1.09 (Sarkar et al 2009a)) and ρ is the medium density (1000 kg/m3). The terms χ and κS depend upon the shell elasticity and dilation viscosity, respectively, derived from the measured shell parameter of OFP t-ELIP from the attenuation measurements described above. The time-dependent source term in (1), pAC, was implemented with calibrated histotripsy waveforms with peak negative pressures of 7.1, 13.9, and 18.3 MPa. The maximum size of a cavitation nucleus without a shell were computed analytically following Bader and Holland (2016), and compared to the numerical calculations for encapsulated microbubbles.

Results

OFP t-ELIP Characterization

The results of the enzymatic activity assay revealed that each reconstituted vial of OFP t-ELIP contained 200 µg/mL active rt-PA. The volume-weighted size distribution and attenuation spectrum for OFP t-ELIP are shown in Figures 4a and 4b, respectively. The size distribution peaks at 1.7 µm diameter, consistent with previous measurements of other ELIP formulations (Raymond et al 2014). The attenuation coefficient increases with frequency up to 15 MHz, with an asymptote of 31 dB/cm. The dashed line in Fig. 4b indicates the predicted attenuation as a function of frequency based on the de Jong model using the best fits for the shell parameters of OFP t-ELIP (κS = 2.15 N/m, χ = 1.64 × 10−8 N/m). The coefficient of determination of the fit to the data was 0.91, consistent with previous measurements of other ELIP formulations (Raymond et al 2014).

Fig 4.

a. The mean volume-weighted size distribution measurements of OFP t-ELIP between 0.65 and 10 µm. The error bars represent one standard deviation (N = 5).

b. The measured attenuation coefficient as a function of frequency (solid line) and theoretical fit to the de Jong model (dashed line) based on the estimated shell parameters of OFP t-ELIP. The error bars represent one standard deviation (N = 5). The coefficient of determination of the fit to the data was 0.91. The number density of liposomes employed for the attenuation measurement was 1.9 ×108 liposomes/mL. Following Raymond et al (2014), the estimated number density of bubbles for the attenuation measurement was 5.4 ×106 bubbles/mL.

Thrombolytic Efficacy

The mass loss as a function of the peak negative pressure of the histotripsy insonation is shown in Fig. 5. For all treatment arms, the thrombolytic efficacy increased with the peak negative pressure of the histotripsy pulse. As indicated in Table 1, the combination of histotripsy and rt-PA or OFP t-ELIP significantly increased the thrombolytic efficacy compared to histotripsy alone, except for OFP t-ELIP and histotripsy compared to histotripsy alone at 20 MPa peak negative pressure. The combination of histotripsy and rt-PA was significantly better than the all other treatment groups at peak negative pressures 14 and 20 MPa. It is notable that histotripsy insonation of the clot at 20 MPa in the presence of either rt-PA or OFP t-ELIP did not significantly improve the thrombolytic efficacy compared to that obtained at 14 MPa for these treatments. The spectrophotometric method was used also to measure the enzymatic activity of rt-PA alone (no clot) after histotripsy exposure. The rt-PA sample was diluted to 1 µg/mL, and the enzymatic activity recorded. No degradation of the enzymatic activity of rt-PA was observed by exposure to histotripsy between 0 MPa and 20 MPa peak negative pressure (Supplemental Fig. 1).

Fig 5.

Thrombolytic efficacy for histotripsy alone, histotripsy and OFP t-ELIP, and histotripsy and rt-PA reported in terms of percent clot mass loss. The p values between treatment arms are indicated in Table 1. The asterisks (*) indicate that the thrombolytic efficacy of that treatment arm is greater than all other treatment arms for that particular peak negative pressure (p < 0.05). The error bars represent one standard deviation (N = 6).

Table 1.

The Tukey’s honest significance test adjusted p vales comparing the treatment arms for the thrombolytic efficacy, shown in Fig. 5. The peak negative pressure is reported for each treatment arm.

| 0 MPa | Histotripsy+rt-PA | Histotripsy+OFP t-ELIP | |

| Histotripsy | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| Histotripsy+rt-PA | – | 0.65 | |

| 7 MPa | Histotripsy+rt-PA | Histotripsy+OFP t-ELIP | |

| Histotripsy | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| Histotripsy+rt-PA | – | 0.05 | |

| 14 MPa | Histotripsy+rt-PA | Histotripsy+OFP t-ELIP | |

| Histotripsy | 0.00 | 0.01 | |

| Histotripsy+rt-PA | – | 0.00 | |

| 20 MPa | Histotripsy+rt-PA | Histotripsy+OFP t-ELIP | |

| Histotripsy | 0.00 | 0.34 | |

| Histotripsy+rt-PA | – | 0.01 |

Particulate Debris

The size distribution of debris collected after treatment is shown in Fig. 6. Over 99.7% of the particulates were less than 5 µm for all treatment arms, and over 99.99% of the debris was less than 10 µm for all treatment arms. This range of particulate size distribution is consistent with previous observations of histotripsy induced thrombolysis (Maxwell et al 2009, Zhang et al 2015b).

Fig 6.

Size distribution of debris measured after treatment at 0 MPa (a), 7 MPa (b), 14 MPa (c), and 20 MPa (d) peak negative pressure. The error bars represent one standard deviation (N = 3). Note that residual lipid and rt-PA may be present in addition to clot debris for the rt-PA and OFP t-ELIP arms.

Passive Cavitation Imaging

Each pixel (i.e. image location) of the computed PCI represents the acoustic power between 2.5 and 8.5 MHz. The acoustic power within the clot increased with the insonation pressure for all treatment arms, as depicted in Fig. 7. For a given peak negative pressure, the bubble activity generated within the different treatment arms was equivalent, except for histotripsy and histotripsy and rt-PA at 7 MPa peak negative pressure. The variability of the location of the maximum PCI pixel amplitude along the axial dimension of the histotripsy source decreases significantly decreases with increasing peak negative pressure for histotripsy and histotripsy and OFP t-ELIP (Fig. 8). At 20 MPa peak negative pressure, the combination of rt-PA and histotripsy had a greater axial variability than the other two treatment arms (histotripsy with and without OFP t-ELIP). No significant differences were observed amongst the treatment arms for the other histotripsy pulse amplitudes.

Fig 7.

The acoustic power within the clot for each treatment arm. The error bars represent one standard deviation (N = 6). The acoustic power within the clot significantly increased with the peak negative pressure of the histotripsy pulse for all treatment arms. At a given peak negative pressure, there was no significant difference between the treatment arms.

Fig 8.

The variability of the location of the maximum PCI pixel amplitude along the axial dimension of the histotripsy source as a function of the peak negative pressure of the histotripsy pulse. The error bars represent one standard deviation (N = 6). The variability significantly decreases with the peak negative pressure for histotripsy and histotripsy and OFP t-ELIP. The asterisks (*) indicate that the axial variability of that treatment arm is greater than all other treatment arms for that particular peak negative pressure of the histotripsy pulse.

Numerical Computation

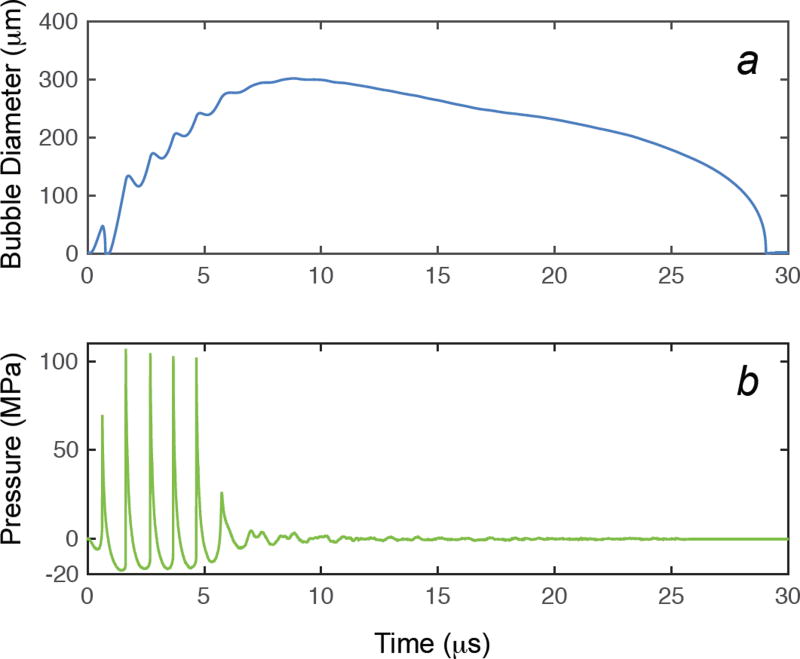

The response of a single encapsulated OFP gas bubble to histotripsy excitation was numerically calculated with the Marmottant equation for initial diameters between 15 nm and 5 µm. The measured shell elasticity and viscosity of microbubbles within OFP t-ELIP (κS = 2.15 N/m, χ = 1.64 × 10−8 N/m) were employed in Eq. (1). A representative measured histotripsy pulse and the corresponding calculated response of a 1.7 µm diameter microbubble and the excitation histotripsy pulse are shown in Fig. 9. The microbubble expands and undergoes an inertial collapse over the first cycle of the pulse. During the subsequent cycles, the dynamics of the microbubble are dominated by the tensile portion of the histotripsy pulse. The impact of the compressive shockwaves only slightly retards the microbubble growth. The microbubble continues to grow after the completion of the histotripsy pulse due to the momentum of the bubble wall, and collapses under atmospheric pressure.

Fig 9.

The response of a shelled microbubble using the Marmottant equation (Strandness and Van Breda 1994, Marmottant et al 2005b), Eq. (1), is shown in panel a. The viscoelastic shell properties of OFP t-ELIP derived from the attenuation measurements were used in the calculation. The experimentally measured waveform used as the excitation source in the computation is shown in panel b. The initial diameter of the cavitation nuclei was 1.7 µm.

Microbubble cloud formation is initiated after the first cycle of the histotripsy pulse (Maxwell et al 2011b), when expansion of the precipitating microbubble is large enough to scatter a significant portion of the incident shockwave. The maximum size of the encapsulated OFP microbubble was numerically computed using only the first fully developed shockwave of the histotripsy pulse (i.e. the second cycle of the histotripsy pulse) as the excitation source. In addition, the maximum size of an OFP bubble without a viscoelastic shell was computed analytically following Bader and Holland (2016). For nuclei larger than 500 nm in diameter, the maximum diameter was observed to be only weakly dependent on the initial diameter (Fig. 10). The maximum diameters after histotripsy exposure of the shelled OFP nano- and microbubbles were slightly less than that of the unshelled OFP nano- and microbubbles, likely due to the added damping and elasticity of the shell.

Fig 10.

Maximum size of the bubble as a function of initial size for shelled microbubbles calculated by numerical integration of the Marmottant model (symbols) and unshelled microbubbles without shell encapsulation using the analytic theory of Bader and Holland (solid lines). The peak negative pressure of the histotripsy pulse is shown in the legend.

Discussion

Thrombolytic Efficacy

Combinatory approaches have previously been employed for the treatment of acute DVT (Chinsakchai et al 2010). Here, we reported on the use of histotripsy as a potential adjuvant therapy to the established clinical protocol of catheter-directed thrombolytics (Patel et al 1998, Mewissen et al 1999) for the ablation of chronic thrombi resistant to pharmomechanical intervention (Whittaker and Przyklenk 2009). The thrombolytic rt-PA was administered in our static in vitro model using fully retracted clots with and without liposomal encapsulation.

The combination of rt-PA and histotripsy was more efficacious than histotripsy alone (Fig. 5). The thrombolytic efficacy correlated with the peak negative pressure of the histotripsy pulse for all treatment arms. Maxwell et al (2009) observed that the lytic rate increased linearly with the peak negative pressure of histotripsy pulse between 6 and 12 MPa. The percent mass loss of clots treated with rt-PA and OFP t-ELIP without histotripsy exposure was equivalent (0 MPa peak negative pressure). Shaw et al (2009a) also observed increased thrombolytic efficacy (fractional clot loss) for rt-PA and air-filled t-ELIP treated human clots in the absence of ultrasound compared to plasma alone. Mass loss for clots exposed to OFP t-ELIP in the absence of ultrasound may be due to localized passive release of the drug. In addition, some rt-PA could be intercalated within the lipid bilayer and lytically active (Smith et al 2010).

It is not apparent why the histotripsy and rt-PA arm is more efficacious than the histotripsy and OFP t-ELIP at peak negative pressure greater than 14 MPa. The enzymatic activity and cavitation activity are equivalent between the two treatment arms. One potential is that the addition of the encapsulated microbubbles would create a two-phase medium (i.e. bubbly liquid) surrounding the clot. The high frequency components of the shockwave would be rapidly attenuated when propagating through the bubbly liquid (Watanabe and Prosperetti 1994). Mitigation of the shockwave amplitude decreases the propensity for cloud activity (Maxwell et al 2011b), potentially limiting the ablative qualities of the histotripsy pulse (Duryea et al 2015). It is also possible that low encapsulation of rt-PA into the liposome reduces the efficacy of histotripsy and OFP t-ELIP.

Measurement of Particulate Debris

The size of particles after treatment were predominately less than 10 µm for all treatment arms (Fig. 6), which is consistent with previous observations of histotripsy induced thrombolysis (Zhang et al 2015b, Maxwell et al 2009). The combination of histotripsy and thrombolytic resulted in a significantly larger number of particulates less than 5 µm. A portion of these particles are likely fibrin degradation products resulting from cleaving of the fibrin mesh resulting from rt-PA acting on the clot. Additionally, the ruptured amphiphilic lipid particulates will preferentially form micelles (Basu and Basu 2002) which would be present for insonation of OFP t-ELIP.

Over 99% of the particle debris was less than 5 µm for all treatment arms. Porcine red blood cells are between 4–5 µm (Lewis 1996). Interestingly, the combination of histotripsy insonation and rt-PA or OFP t-ELIP generated significantly more particles in this size range than histotripsy insonation alone (Fig. 11). The ablative qualities of histotripsy primarily result in acellular debris (Maxwell et al 2009). Our results suggest the addition of thrombolytic to histotripsy may result in a decrease in hemolysis, which would decrease the likelihood of acute renal failure due to massive hemolysis (Arslan et al 2007). Future studies are required to determine the degree of hemolysis.

Fig 11.

Percent of debris measured after treatment between 4–5 µm, the typical size of porcine red blood cells, compared to the total number of particles measured (0.65–18 µm). The error bars represent one standard deviation (N = 3). The addition of thrombolytic significantly increased the number of particulates in this range, suggesting preservation of red blood cells for the combined histotripsy and thrombolytic treatment arms.

Cavitation Activity

Passive cavitation images were employed to monitor the acoustic power scattered during the histotripsy excitation. Both B-mode images (Hall et al 2007) and color Doppler (Zhang et al 2015a) have been employed to monitor cavitation activity during histotripsy pulses. However, these imaging modalities provide only spatial information of cavitation activity, and do not elucidate information on the mechanical action of the cavitation known to be responsible for the ablative qualities of histotripsy (Xu et al 2006). The resultant cavitation-generated acoustic emissions can be mapped directly with passive cavitation imaging (PCI).

The acoustic power within the clot was not significantly different between the treatment arms, even with the addition of OFP gas entrained within the OFP t-ELIP. This may be due in part to near instantaneous rupture of the OFP microbubbles by the first histotripsy pulse (Marmottant et al 2005). The likelihood of rupturing the shell of encapsulated microbubbles is quantified by the cavitation index (Bader and Holland 2012), which is defined as the ratio of the peak negative pressure to the center frequency of the insonation. Shell rupture becomes more likely as the cavitation index exceeds 0.02. For the insonation parameters employed in this study the cavitation index ranged from 7–20, indicating a strong likelihood of rupture. Numerical integration of the Marmottant equation (Marmottant et al 2005) for OFP t-ELIP microbubbles indicated a several hundred fold expansion of the initial microbubble (figures 9 and 10). The predicted expansion ratio of the shelled microbubble would suggest the initial cavitation nuclei were likely destroyed within the first pulse and did not result in sustained microbubble activity. The addition of flow to the model would allow replenishment of the cavitation nuclei (Hitchcock et al 2011, Bader et al 2015c).

The fate of the residual OFP gas cores is unknown. Unshelled bubbles with an OFP gas core smaller than 0.5 µm diameter would dissolve into solution within 50 ms (Sarkar et al 2009), which is less than the period between histotripsy pulses in the present study. The attenuation spectrum of OFP t-ELIP is most prominent above 15 MHz (Fig. 4b), which would indicate a large number of acoustically active ELIP less than 0.4 µm diameter (Marmottant et al 2005). Coalescence of the bubbles may also occur (Postema et al 2004, Bader et al 2015c). Alternatively, complex dynamics of the microbubble cloud that are not properly modeled here may contribute. Regardless, the response of a cavitation nucleus appears independent of the initial conditions (e.g. shelled or unshelled), as indicated in Fig. 10.

Vlaisavljevich et al (2015) employed perfluoropentane nanodroplets as exogenous nuclei for histotripsy-generated microbubble cloud formation. Using high-speed videography and passive cavitation detection, copious cavitation was initially observed. However, no cavitation was observed after 16 pulses for 1.5 MHz pulse delivered at 1 Hz. Equivalent cavitation activity was detected throughout all 2000 histotripsy pulses in this study, even without the addition of exogenous nuclei. The sustained bubble activity observed might be due in part to the relatively higher PRF compared to that employed by Vlaisavljevich et al (20 Hz vs. 1 Hz). The presence of the LDPE tube containing the clot might have obviated the need for the addition of exogenous cavitation nuclei (Xu et al 2007).

Numerical Computation of OFP Microbubble Response

The growth of the initial microbubble nucleus is the precipitating event for the formation of the ablative microbubble cloud (Maxwell et al 2011b). Without exogenous nuclei, microbubble clouds are hypothesized to form from endogenous nanometer-sized nuclei present in the tissue (Maxwell et al 2013). Copious cavitation nuclei are likely present in this study from the tube surface and plasma, which were in the pre-focal region of the histotripsy field (Xu et al 2007). The calculated maximum size of a microbubble exposed to a histotripsy pulse is nearly independent of its initial size and is not strongly affected by the presence of the shell (Fig. 10), consistent with previous computations of microbubbles excited by shockwaves (Bader and Holland 2016, Church 1989, Iloreta et al 2008).

Study Limitations

The in vitro clot model used in this study allowed an in-depth study of thrombolytic mechanisms. However, several aspects of this in vitro study limit the applicability of these findings. The static fluid system used in this study neglected a continuous reperfusion of the thrombolytic, as would occur for catheter-directed thrombolytics (Patel et al 1998). In addition, some flow would occur even for a nearly occlusive thrombus (White et al 1989), which may contribute to both the replenishment of cavitation nuclei and the lytic rate (Bajd et al 2010).

Cavitation emissions were only recorded at the first insonation location of the clot, and were assumed to be representative of the insonation at all locations. Over the 20 min duration of the treatment, heating effects were negligible for the low duty cycle histotripsy insonation (Parsons et al 2006). Partial diffusion of the OFP gas through the encapsulating shell would occur over the 20 min treatment duration in the absence of histotripsy pulses (Raymond 2015). Once the encapsulated microbubble were exposed to histotripsy pulses, however, the lipid shell ruptured, followed by a rapid loss of echogenicity (Bader and Holland 2012, Radhakrishnan et al 2013).

The arrangement of the imaging array allowed for resolution of cavitation along the central axis of the histotripsy transducer. However, this geometry would be difficult to implement for in vivo studies depending on the available acoustic paths. In the future, an imaging array that is in-line with the central axis of the histotripsy transducer would be more practical for PCI guidance of histotripsy. The delay, sum, and integration method used to process the PCI has larger range resolution than azimuthal resolution. Although very computationally intensive, using robust Capon beamforming to process the PCI would provide improved spatial resolution (Coviello et al 2015).

A relatively low dose of histotripsy pulses were applied in each arm of the study, which allowed elucidation of subtle differences between the treatment groups. The efficacy of histotripsy as a stand-alone treatment can be optimized through modifying the insonation scheme (e.g. PRF, pulse duration, and amplitude) (Xu et al 2007). Further studies are required to determine the optimal parameters for histotripsy in combination with rt-PA.

The clinically administered dose of rt-PA in humans is 3.15 µg/mL (Tanswell et al 1991). Porcine blood has a much lower concentration of plasminogen compared to human blood (Lewis 1996), and therefore is less responsive to rt-PA. The concentration of rt-PA used in these studies (24 µg/mL) was larger than the dose administered clinically, but is within the range employed for porcine thrombolysis studies (Datta et al 2008, Holland et al 2008).

Only clot debris less than 18 µm diameter was measured in this study. Particulates larger than a few micrometers are sparse for clots exposed to histotripsy pulses (Maxwell et al 2009, Zhang et al 2015b). The clinical scenario of an occluding thrombus was not modeled here (Liebeskind et al 2011). Encapsulation of the thrombolytic within an echogenic liposome may reduce systemic exposure of rt-PA of patients, decreasing the risk of bleeding. The systemic toxicity and side effects of the treatment could also not be ascertained in this in vitro model. Further in vivo studies are needed to assess the potential reduction of adverse bioeffects in vivo.

The enzymatic activity of OFP t-ELIP was only assessed after the addition of the surfactant Triton-X, which ensured the release of any encapsulated lytic. Future studies will explore the efficiency of encapsulation of thrombolytic in OFP t-ELIP, and the release profile after histotripsy exposure.

Summary

Histotripsy is a promising ultrasound ablative therapy for the treatment of deep vein thrombosis. This study employed histotripsy in combination with a thrombolytic for clot lysis. In addition, histotripsy was used to trigger localized release of the potent thrombolytic rt-PA from echogenic liposomes. Passive cavitation imaging was employed to monitor microbubble cloud formation. Improved thrombolytic efficacy was generally observed for the combination of rt-PA and histotripsy. No significant differences were observed in the power of cavitation emissions or the spatial location of cavitation for histotripsy insonation of OFP t-ELIP versus insonation of plasma or plasma and rt-PA. However, numerical studies of the oscillations of encapsulated OFP microbubbles entrained within OFP t-ELIP suggest near instantaneous rupture of the lipid shell when exposed to histotripsy pulses. Nevertheless, these results suggest that the synergistic effects of histotripsy combined with the administration of rt-PA could be a compelling technique for treating highly retracted clots typical of deep vein thrombosis.

Supplementary Material

The enzymatic activity of rt-PA following exposure to histotripsy insonation (N = 3 for each pressure). The thrombolytic rt-PA was diluted into 0.5% bovine serume albumin and exposed to histotripsy pulses using the set-up described in Figure 1 of the revised manuscript. After exposure, the enzymatic activity of the rt-PA was measured using the spectrophotometric method described in the methods section. Adjusted p values based on Tukey’s HSD test were greater than 0.05, indicating exposure to histotripsy did not significantly alter the enzymatic activity or rt-PA for the range of peak negative pressures used in this study.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded in part by the Focused Ultrasound Foundation (319R1) and the National Institutes of Health (R01 NS047603).

References

- Arslan B, Turba U, Matsumoto A. Acute Renal Failure Associated with Percutaneous Mechanical Thrombectomy for Iliocaval Venous Thrombosis. Semin intervent Radiol. 2007;24:288–95. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-985736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Augustinos P. Invasive Approaches to Treatment of Venous Thromboembolism. Circulation. 2004;110:I-27–I-34. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000140900.64198.f4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avgerinos ED, Hager ES, Naddaf A, Dillavou E, Singh M, Chaer RA. Outcomes and predictors of failure of thrombolysisfor iliofemoral deep venous thrombosis. J Vasc Surg. 2015;3:35–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jvsv.2014.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aziz F, Comerota AJ. Quantity of residual thrombus after successful catheter-directed thrombolysis for iliofemoral deep vein thrombosis correlates with recurrence. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2012;44:210–3. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2012.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bader KB, Holland CK. Predicting the growth of nanoscale nuclei by histotripsy pulses. Phys Med Biol. 2016 doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/61/7/2947. (In Press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bader KB, Holland CK. Gauging the likelihood of stable cavitation from ultrasound contrast agents. Phys Med Biol. 2012;58:127–44. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/58/1/127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bader KB, Bouchoux G, Holland CK. Sonothrombolysis. In: Escoffre J-M, Bouakaz A, editors. Therapeutic Ultrasound. Springer; 2015a. pp. 1–34. [Google Scholar]

- Bader KB, Bouchoux G, Peng T, Klegerman ME, McPherson DD, Holland CK. Thrombolytic efficacy and enzymatic activity of rt-PA-loaded echogenic liposomes. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2015b:1–12. doi: 10.1007/s11239-015-1204-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bader KB, Gruber MJ, Holland CK. Shaken and Stirred. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2015c;41:187–96. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2014.08.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bajd F, Vidmar J, Blinc A, Serša I. Microscopic clot fragment evidence of biochemo-mechanical degradation effects in thrombolysis. Thromb Res. 2010;126:137–43. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2010.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basu SC, Basu M. Liposome Methods and Protocols. Springer Science & Business Media; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Beckman MG, Hooper WC, Critchley SE, Ortel TL. Venous Thromboembolism. Am J Preven Med. 2010;38:S495–S501. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chinsakchai K, Duis ten K, Moll FL, de Borst GJ. Trends in Management of Phlegmasia Cerulea Dolens. Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2010;45:5–14. doi: 10.1177/1538574410388309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Church CC. A theoretical study of cavitation generated by an extracorporeal shock wave lithotripter. J Acoust Soc Am. 1989;86:215. doi: 10.1121/1.398328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coviello C, Kozick R, Choi J, Gyöngy M, Jensen C, Smith PP, Coussios C-C. Passive acoustic mapping utilizing optimal beamforming in ultrasound therapy monitoring. J Acoust Soc Am. 2015;137:2573–85. doi: 10.1121/1.4916694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Datta S, Coussios C-C, Ammi AY, Mast TD, de Courten-Myers GM, Holland CK. Ultrasound-Enhanced Thrombolysis Using Definity® as a Cavitation Nucleation Agent. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2008;34:1421–33. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2008.01.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Datta S, Coussios C-C, McAdory LE, Tan J, Porter T, De Courten-Myers G, Holland CK. Correlation of cavitation with ultrasound enhancement of thrombolysis. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2006;32:1257–67. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2006.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donaldson CW, Baker JN, Narayan RL, Provias TS, Rassi AN, Giri JS, Sakhuja R, Weinberg I, Jaff MR, Rosenfield K. Thrombectomy using suction filtration and veno-venous bypass: Single center experience with a novel device. Cathet Cardiovasc Intervent. 2015;86:E81–7. doi: 10.1002/ccd.25583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duryea AP, Roberts WW, Cain CA, Hall TL. Removal of residual cavitation nuclei to enhance histotripsy erosion of model urinary stones. IEEE Trans Ultrason Ferroelect Freq Contr. 2015;62:896–904. doi: 10.1109/TUFFC.2015.7001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson CJ, Britton KA, Miller AL, Loscalzo J. Out of the Blue. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1742–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcps1213589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grosse SD. Incidence-based cost estimates require population-based incidence data. A critique of Mahan et al. Thromb Haemost. 2012;107:192–3. doi: 10.1160/TH11-09-0666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gyöngy M, Arora M, Noble JA, Coussios CC. Use of passive arrays for characterization and mapping of cavitation activity during HIFU exposure. IEEE Ultrason Symp. 2008:871–4. [Google Scholar]

- Hall T, Cain C. A low cost compact 512 channel therapeutic ultrasound system for transcutaneous ultrasound surgery AIP Conf Proc. 2006;829:445. [Google Scholar]

- Hall T, Fowlkes J, Cain C. A real-time measure of cavitation induced tissue disruption by ultrasound imaging backscatter reduction. IEEE Trans Ultrason Ferroelect Freq Contr. 2007;54:569–75. doi: 10.1109/tuffc.2007.279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haworth KJ, Mast TD, Radhakrishnan K, Burgess MT, Kopechek JA, Huang S-L, McPherson DD, Holland CK. Passive imaging with pulsed ultrasound insonations. J Acoust Soc Am. 2012;132:544. doi: 10.1121/1.4728230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirsh J, Hoak J. Management of Deep Vein Thrombosis and Pulmonary Embolism. Circulation. 1996;93:2212–45. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.93.12.2212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hitchcock KE, Ivancevich NM, Haworth KJ, Stamper DNC, Vela DC, Sutton JT, Pyne-Geithman GJ, Holland CK. Ultrasound-enhanced rt-PA Thrombolysis in an ex vivo Porcine Carotid Artery Model. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2011;37:1240–51. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2011.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland CK, Apfel RE. Improved Theory for the Prediction of Microcavitation Thresholds. IEEE Trans Ultrason Ferroelect Freq Contr. 1989;36:204–8. doi: 10.1109/58.19152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland CK, Vaidya SS, Datta S, Coussios C-C, Shaw GJ. Ultrasound-enhanced tissue plasminogen activator thrombolysis in an in vitro porcine clot model. Thromb Res. 2008;121:663–73. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2007.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hood DB, Weaver FA, Modrall JG, Yellin AE. Advances in the treatment of phlegmasia cerulea dolens. Am J Surg. 1993;166:206–210. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(05)81057-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoskins PR. Physical Properties of Tissues Relevant to Arterial Ultrasound Imaging and Blood Velocity Measurement. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2007;33:1527–39. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2007.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iloreta JI, Fung NM, Szeri AJ. Dynamics of bubbles near a rigid surface subjected to a lithotripter shock wave. Part 1. Consequences of interference between incident and reflected waves. J Fluid Mech. 2008;616:43. [Google Scholar]

- Kalagher SD, Kane DD. Phlegmasia cerulea dolens: before and after lysis. Intern Emerg Med. 2014;10:103–4. doi: 10.1007/s11739-014-1086-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kassas S. Catheter extraction of high risk right atrial clot, technical tips, and lessons learned. successes and failures. Cathet Cardiovasc Intervent. 2013;84:1197–201. [Google Scholar]

- Laing ST, Moody MR, Kim H, Smulevitz B, Huang S-L, Holland CK, McPherson DD, Klegerman ME. Thrombolytic efficacy of tissue plasminogen activator-loaded echogenic liposomes in a rabbit thrombus model. Thromb Res. 2012;130:629–35. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2011.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis JH. Comparative Hemostasis in Vertebrates. New York: Plenum Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Liebeskind DS, Sanossian N, Yong WH, Starkman S, Tsang MP, Moya AL, Zheng DD, Abolian AM, Kim D, Ali LK, Shah SH, Towfighi A, Ovbiagele B, Kidwell CS, Tateshima S, Jahan R, Duckwiler GR, Vinuela F, Salamon N, Villablanca JP, Vinters HV, Marder VJ, Saver JL. CT and MRI Early Vessel Signs Reflect Clot Composition in Acute Stroke. Stroke. 2011;42:1237–43. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.605576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin SC, Mousa A, Bernheim J, Dayal R. Endoluminal Recanalization in a Patient with Phlegmasia Cerulea Dolens Using a Multimodality Approach. Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2005;39:273–279. doi: 10.1177/153857440503900309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maev RG. Acoustic Microscopy: Fundamentals and Applications. Weinheim, Germany: Wiley VCH; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Marder VJ, Chute DJ, Starkman S, Abolian AM, Kidwell C, Liebeskind D, Ovbiagele B, Vinuela F, Duckwiler G, Jahan R, Vespa PM, Selco S, Rajajee V, Kim D, Sanossian N, Saver JL. Analysis of Thrombi Retrieved From Cerebral Arteries of Patients With Acute Ischemic Stroke. Stroke. 2006;37:2086–93. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000230307.03438.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marmottant P, van der Meer S, Emmer M, Versluis M, de Jong N, Hilgenfeldt S, Lohse D. A model for large amplitude oscillations of coated bubbles accounting for buckling and rupture. J Acoust Soc Am. 2005;118:3499. [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell AD, Cain CA, Duryea AP, Yuan L, Gurm HS, Xu Z. Noninvasive Thrombolysis Using Pulsed Ultrasound Cavitation Therapy – Histotripsy. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2009;35:1982–94. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2009.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell AD, Cain CA, Hall TL, Fowlkes JB, Xu Z. Probability of Cavitation for Single Ultrasound Pulses Applied to Tissues and Tissue-Mimicking Materials. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2013;39:449–65. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2012.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell AD, Owens G, Gurm HS, Ives K, Myers DD, Jr, Xu Z. Noninvasive Treatment of Deep Venous Thrombosis Using Pulsed Ultrasound Cavitation Therapy (Histotripsy) in a Porcine Model. J Vasc Intervent Radiol. 2011a;22:369–77. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2010.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell AD, Wang T-Y, Cain CA, Fowlkes JB, Sapozhnikov OA, Bailey MR, Xu Z. Cavitation clouds created by shock scattering from bubbles during histotripsy. J Acoust Soc Am. 2011b;130:1888. doi: 10.1121/1.3625239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mewissen MW, Seabrook GR, Meissner MH, Cynamon J, Labropoulos N, Haughton SH. Catheter-directed thrombolysis for lower extremity deep venous thrombosis: report of a national multicenter registry. Radiol. 1999;211:39–49. doi: 10.1148/radiology.211.1.r99ap4739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mumoli N, Invernizzi C, Luschi R, Carmignani G, Camaiti A, Cei M. Phlegmasia Cerulea Dolens. Circulation. 2012;125:1056–7. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.051912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oguzkurt L, Ozkan U, Gulcan O, Koca N, Gur S. Endovascular treatment of acute and subacute iliofemoral deep venous thrombosis using manual aspiration thrombectomy: long-term result of 139 patients from a single center. Diagn Interv Radiol. 2011 doi: 10.4261/1305-3825.DIR.5175-11.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons JE, Cain CA, Abrams GD, Fowlkes JB. Pulsed cavitational ultrasound therapy for controlled tissue homogenization. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2006;32:115–29. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2005.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel NH, Plorde JJ, Meissner M. Catheter-directed thrombolysis in the treatment of phlegmasia cerulea dolens. Ann Vasc Surg. 1998;12:471–5. doi: 10.1007/s100169900187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel NH, Stookey KR, Ketcham DB, Cragg AH. Endovascular management of acute extensive iliofemoral deep venous thrombosis caused by May-Thurner syndrome. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2000;11:1297–302. doi: 10.1016/s1051-0443(07)61304-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Postema M, Marmottant P, Lancée CT, Hilgenfeldt S, de Jong N. Ultrasound-induced microbubble coalescence. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2004;30:1337–44. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2004.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radhakrishnan K, Bader KB, Haworth KJ, Kopechek JA, Raymond JL, Huang S-L, McPherson DD, Holland CK. Relationship between cavitation and loss of echogenicity from ultrasound contrast agents. Phys Med Biol. 2013;58:6541–63. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/58/18/6541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raymond JL. Bioactive gas encapsulation and release from echogenic liposomes, thesis, University of Cincinnati 2015 [Google Scholar]

- Raymond JL, Haworth KJ, Bader KB, Radhakrishnan K, Griffin JK, Huang S-L, McPherson DD, Holland CK. Broadband attenuation measurements of phospholipid-shelled ultrasound contrast agents. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2014;40:410–21. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2013.09.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salgaonkar VA, Datta S, Holland CK, Mast TD. Passive cavitation imaging with ultrasound arrays. J Acoust Soc Am. 2009;126:3071. doi: 10.1121/1.3238260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar K, Katiyar A, Jain P. Growth and Dissolution of an Encapsulated Contrast Microbubble: Effects of Encapsulation Permeability. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2009;35:1385–96. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2009.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw GJ, Dhamija A, Bavani N, Wagner KR, Holland CK. Arrhenius temperature dependence of in vitrotissue plasminogen activator thrombolysis. Phys Med Biol. 2007;52:2953–67. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/52/11/002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw GJ, Meunier JM, Huang S-L, Lindsell CJ, McPherson DD, Holland CK. Ultrasound-enhanced thrombolysis with tPA-loaded echogenic liposomes. Thromb Res. 2009a;124:306–10. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2009.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw GJ, Sperling M, Meunier JM. Long-term stability of recombinant tissue plasminogen activator at −80 C. BMC Res Notes. 2009b;2:117. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-2-117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith DAB, Vaidya SS, Kopechek JA, Huang S-L, Klegerman ME, McPherson DD, Holland CK. Ultrasound-Triggered Release of Recombinant Tissue-Type Plasminogen Activator from Echogenic Liposomes. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2010;36:145–57. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2009.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strandness DE, Van Breda A. Vascular diseases: surgical and interventional therapy. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Sutton JT, Ivancevich NM, Perrin SR, Jr, Vela DC, Holland CK. Clot Retraction Affects the Extent of Ultrasound-Enhanced Thrombolysis in an Ex Vivo Porcine Thrombosis Model. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2013;39:813–24. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2012.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanswell P, Seifried E, Stang E, Krause J. Pharmacokinetics and hepatic catabolism of tissue-type plasminogen activator. Arzneimittel-Forschung. 1991;41:1310–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiukinhoy-Laing SD, Buchanan K, Parikh D, Huang S, MacDonald RC, McPherson DD, Klegerman ME. Fibrin targeting of tissue plasminogen activator-loaded echogenic liposomes. J Drug Targe. 2007;15:109–14. doi: 10.1080/10611860601140673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran BC, Seo J, Hall TL, Fowlkes JB, Cain CA. Effects of contrast agent infusion rates on thresholds for tissue damage produced by single exposures of high-intensity ultrasound. IEEE Trans Ultrason Ferroelect Freq Contr. 2005;52:1121–30. doi: 10.1109/tuffc.2005.1503998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turi ZG, Goldberg S, LittleJohn JK, VanderArk C, Shadoff N, Karlsberg R, Williams J, Butman S, Stadius ML, Wise K. Dose-related efficacy and bleeding complications of double-chain tissue plasminogen activator in acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol. 1993;71:1009–14. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(93)90564-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verheijen JH, de Jong YF, Chang GTG. Quantiative analysis of the composition of mixtures of one-chain and two-chain tissue-type plasminogen activator with a spectrophotometric method. Thromb Res. 1985;39:281–8. doi: 10.1016/0049-3848(85)90223-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vlaisavljevich E, Aydin O, Durmaz YY, Lin K-W, Fowlkes B, ElSayed M, Xu Z. Effects of ultrasound frequency on nanodroplet-mediated histotripsy. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2015;41:2135–47. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2015.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vlaisavljevich E, Durmaz YY, Maxwell A, ElSayed M, Xu Z. Nanodroplet-Mediated Histotripsy for Image-guided Targeted Ultrasound Cell Ablation. Theranostics. 2013;3:851–64. doi: 10.7150/thno.6717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe M, Prosperetti A. Shock waves in dilute bubbly liquids. J Fluid Mech. 1994;274:349–81. [Google Scholar]

- Watson T, Shantsila E, Lip GY. Mechanisms of thrombogenesis in atrial fibrillation: Virchow’s triad revisited. The Lancet. 2009;373:155–66. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60040-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisel JW. Structure of fibrin: impact on clot stability. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2007;5(Suppl 1):116–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2007.02504.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells PS, Forgie MA, Rodger MA. Treatment of Venous Thromboembolism. J Am Med Assoc. 2014;311:717. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White RH, McGahan JP, Daschbach MM, Hartling RP. Diagnosis of deep-vein thrombosis using duplex ultrasound. Ann Intern Med. 1989;111:297–304. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-111-4-297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whittaker P, Przyklenk K. Fibrin architecture in clots. Blood Cell Mol Dis. 2009;42:51–6. doi: 10.1016/j.bcmd.2008.10.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Worku B, Blake K, Gulkarov I, Sista A, Salemi A. Percutaneous Removal of Filter-Induced Iliocaval Thrombus Using the AngioVac Device. Innovations. 2015;10:212–4. doi: 10.1097/IMI.0000000000000156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Z, Fowlkes JB, Cain CA. A new strategy to enhance cavitational tissue erosion using a high-intensity, initiating sequence. IEEE Trans Ultrason Ferroelect Freq Contr. 2006;53:1412–24. doi: 10.1109/tuffc.2006.1665098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Z, Hall TL, Fowlkes JB, Cain CA. Effects of acoustic parameters on bubble cloud dynamics in ultrasound tissue erosion (histotripsy) J Acoust Soc Am. 2007;122:229. doi: 10.1121/1.2735110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Miller RM, Lin K-W, Levin AM, Owens GE, Gurm HS, Cain CA, Xu Z. Real-time feedback of histotripsy thrombolysis using bubble-induced color Doppler. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2015a;41:1386–401. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2014.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Owens GE, Gurm HS, Ding Y, Cain CA, Xu Z. Noninvasive thrombolysis using histotripsy beyond the intrinsic threshold (microtripsy) IEEE Trans Ultrason Ferroelect Freq Contr. 2015b;62:1342–55. doi: 10.1109/TUFFC.2015.007016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

The enzymatic activity of rt-PA following exposure to histotripsy insonation (N = 3 for each pressure). The thrombolytic rt-PA was diluted into 0.5% bovine serume albumin and exposed to histotripsy pulses using the set-up described in Figure 1 of the revised manuscript. After exposure, the enzymatic activity of the rt-PA was measured using the spectrophotometric method described in the methods section. Adjusted p values based on Tukey’s HSD test were greater than 0.05, indicating exposure to histotripsy did not significantly alter the enzymatic activity or rt-PA for the range of peak negative pressures used in this study.