Abstract

In multicellular organisms, relations among parts and between parts and the whole are contextual and interdependent. These organisms and their cells are ontogenetically linked: an organism starts as a cell that divides producing non-identical cells, which organize in tri-dimensional patterns. These association patterns and cells types change as tissues and organs are formed. This contextuality and circularity makes it difficult to establish detailed cause and effect relationships. Here we propose an approach to overcome these intrinsic difficulties by combining the use of two models; 1) an experimental one that employs 3D culture technology to obtain the structures of the mammary gland, namely, ducts and acini, and 2) a mathematical model based on biological principles.

The typical approach for mathematical modeling in biology is to apply mathematical tools and concepts developed originally in physics or computer sciences. Instead, we propose to construct a mathematical model based on proper biological principles. Specifically, we use principles identified as fundamental for the elaboration of a theory of organisms, namely i) the default state of cell proliferation with variation and motility and ii) the principle of organization by closure of constraints.

This model has a biological component, the cells, and a physical component, a matrix which contains collagen fibers. Cells display agency and move and proliferate unless constrained; they exert mechanical forces that i) act on collagen fibers and ii) on other cells. As fibers organize, they constrain the cells on their ability to move and to proliferate. The model exhibits a circularity that can be interpreted in terms of closure of constraints.

Implementing the mathematical model shows that constraints to the default state are sufficient to explain ductal and acinar formation, and points to a target of future research, namely, to inhibitors of cell proliferation and motility generated by the epithelial cells. The success of this model suggests a step-wise approach whereby additional constraints imposed by the tissue and the organism could be examined in silico and rigorously tested by in vitro and in vivo experiments, in accordance with the organicist perspective we embrace.

Keywords: Ductal morphogenesis, Mathematical models, Organicism, Organizational closure, Acinar morphogenesis, Mammary gland morphogenesis

“Theory and fact are equally strong and utterly interdependent; one has no meaning without the other. We need theory to organize and interpret facts, even to know what we can or might observe. And we need facts to validate theories and give them substance.”

Stephen Jay Gould. (1998). Leonardo’s Mountain of Clams and the Diet of Worms: Essays on Natural History, 155.

1. Introduction

Scientific theories provide organizing principles and construct objectivity by framing observations and experiments (Longo and Soto, 2016). On the one hand, theories construct the proper observables and on the other they provide the framework for studying them. Good theories, like Newton’s law of inertia and the conservation of momentum from his 3rd law were never abandoned but were reinstated while physics underwent further theoretical changes. Indeed, a deeper understanding of these principles was gained through E. Noether’s theorems which justify the conservation properties of energy and momenta in terms of symmetries in the state equations (van Fraassen, 1989). However, a theory does not need to be “right” to guide the praxis of good experiments. Even a “wrong” theory can be useful if, when proven incorrect it is modified or even dismissed.

Here we demonstrate that the application of the principles we propose to use for the construction of a theory of organisms results in a better understanding of morphogenesis (the generation of biological form) than the common practice of using metaphors derived from the mathematical theory of information as theoretical background [for a critique see Perret and Longo (2016) and Longo et al. (2015)]. Our approach diverges from the biophysical methodology which is based on conservation principles and their associated symmetries, on the one hand, and with optimization principles, on the other. In contrast, biology is about an incessant breaking of symmetries (Longo et al., 2015; Longo and Montévil, 2011; Longo and Soto, 2016). Taking mammary gland morphogenesis as an example, here we show that our theoretical principles are useful to provide a framework for the mathematical modeling of tissue morphogenesis. We will focus on the manner in which we propose to deal with cellular behavior.

2. Theoretical principles

We begin by identifying a foundational principle, the default state of cells, which is proliferation with variation and motility. This default state is a manifestation of the agency of living objects, and thus, a cause; it does not need an explanation or an external cause (Longo et al., 2015; Soto et al., 2016). The default state is what happens when nothing is done to the system. Second, we adopt the notion that organismal constraints prevent the expression of the default state. This means that constraints determine when proliferation with variation and/or motility are allowed to instantiate. Third, we consider it essential to stress that biological processes make full sense only in the context of the organism in which they take place. As stated by Claude Bernard: “The physiologist and the physician must never forget that the living being comprises an organism and an individuality. If we decompose the living organism into its various parts, it is only for the sake of experimental analysis, not for them to be understood separately. Indeed, when we wish to ascribe to a physiological quality its value and true significance, we must always refer to this whole and draw our final conclusions only in relation to its effects in the whole.” We address this aspect of biological integration using the notion of closure of constraints (see Mossio et al., 2016). These constraints are considered “local invariants” because they do not change at the time scale of the process they influence. In an organism, these constraints depend collectively on each other thus attaining closure. In turn, closure provides an understanding of the relative stability of biological organizations. Fourth, organisms spontaneously undergo variation. A fundamental generator of variation is the default state. Unlike physical systems, biological ones are not framed by invariants and invariant preserving transformations. Instead, the flow of time is associated with qualitative changes of organization that cannot be stated a priori. This original feature is directly related to the historical nature of biological objects, since a specific object is the result of this unpredictable accumulation of changes (Longo et al., 2015; Montévil et al., 2016). Another notion that becomes fundamental through this principle of variation is that of contextuality. Indeed, understanding biological organization requires taking into account its interaction with the surrounding environment, both at a given time-point and through the successive environments that biological objects traverse (Soto and Sonnenschein, 2005) (see Miquel and Hwang, 2016; Montévil et al., 2016; Sonnenschein and Soto, 2016). In addition to the role that constraints play in canalizing processes, they make possible the appearance of new constraints and thus changes of organization. Lastly, the framing principle states that biological phenomena should be understood as the non-identical iterations of morphogenetic processes. Biological processes iterate at all levels of organization. Organization involves iteration through the circularity of closures, but organization itself is also iterated as reproduction. Inside organisms, structures are also iterated, for example in the case of branching morphogenesis. In all cases, the principle of variation applies so that each iteration may be associated with unpredictable qualitative changes (Longo et al., 2015).

Together these principles provide a genuinely biological framework for the understanding of organismal phenomena. This framework combines the integrative viewpoint inherited from physiology, the centrality of biological variation that derives from the theory of evolution and the default state that links organismal and evolutionary biology.

3. The mammary gland as a model system

The mammary gland is made up of two main tissue types, namely, i) the epithelial parenchyma, its function is to produce and deliver milk, and ii) the stroma which surrounds and supports the epithelium. The stroma is composed of various cell types (fibroblasts, adipocytes, and immune cells), blood vessels, nerves, and an extracellular fibrous matrix of which the main component is collagen type-I. In the resting gland the epithelium is organized into a ductal tree. During pregnancy a second epithelial compartment, the alveoli, develop from the ducts; these are the structures that produce and secrete milk. Throughout development, reciprocal interactions between the epithelium and the stroma are responsible for the structure and function of mammary glands. Perturbations of epithelial-stromal interactions result in various pathologies including neoplasms (Soto and Sonnenschein, 2011; Sonnenschein and Soto, 2016).

The mammary gland undergoes morphological and functional changes throughout life. Mammary organogenesis has been studied in most detail in rodents. In mice, the mammary placodes become visible between embryonic day (E) 11 and 12 and they then develop into mammary buds by E13. At this time, several layers of mesenchyme condense surrounding the buds in a concentric fashion. In female mouse embryos the mammary bud sprouts and invades the presumptive fat pad. At E18, the mammary epithelium consists of an incipient ductal tree (Balinsky, 1950; Robinson et al., 1999). Although fetal mammary gland development occurs even in the absence of receptors for mammotropic hormones suggesting that these hormones are not required at this stage, fetal mammary morphogenesis can be altered by exposure to hormonally-active chemicals (Vandenberg et al., 2007). From the onset of puberty, the development of the mammary gland is subject to hormonal regulation. At the onset of puberty, estrogens induce the formation of club-shaped structures at the end of the ducts, called terminal end buds (TEBs). Thereafter, the epithelium begins to fill the fat pad and branches. Progesterone induces lateral branching. If pregnancy occurs, prolactin in combination with estrogen and progesterone initiates a characteristic lobuloalveolar development [reviewed in Brisken and O’Malley (2010)]. When lactation ceases, involution of the alveolar structures occurs and the mammary gland returns to its resting state.

3.1. Biological models for the study of mammary gland biology

3D culture systems allow for the dynamic study of epithelial morphogenesis and the organization of the stroma. These models are intended to mimic conditions prevailing in a living organism while reducing the number of constraints present in vivo to those which theoretically and/or empirically are considered to be the most relevant ones for the subject study. When designing a 3D culture model one must first define the main characteristics of the target tissue that the model aims to reproduce, and which stage of mammary gland development the investigator is interested in reproducing in vitro. The objective of mimicking the tissue of origin is tempered by the need to make it manageable by reducing the model to a few components. This allows the researcher to infer from these results the contribution of these components to the mammary gland phenotype in vivo. The resulting model may then be compared to more complex ones resulting from the step-wise addition of relevant components, and eventually to the behavior of the gland in situ.

Epithelial–stromal interactions can be studied using 3D co-cultures of epithelial and stromal cells by analyzing matrix remodeling and epithelial morphogenesis. With regard to matrices the most biologically relevant ones are those that provide the structure and rigidity of the model tissue that allows the cellular components to attain characteristics seen in the breast.

Here we focus on collagen-based matrices since collagen is a main component of the mammary stroma that allows for breast epithelial cells to organize into structures that closely resemble those observed in vivo (Krause et al. 2008, 2012; Dhimolea et al., 2010; Speroni et al., 2014; Barnes et al., 2014).

3.1.1. MCF10A 3D culture model

To test the mathematical model, we used data generated using the MCF10A 3D culture model described in Barnes et al. (2014). In this 3D culture model, the proportion of acinar and ductal structures can be modified by changing the concentration of reconstituted basement membrane (Matrigel) in the extracellular matrix (ECM) (Krause et al., 2008; Barnes et al., 2014). Briefly, MCF10A human breast epithelial cells were seeded in either bovine type-I collagen matrix or in mixed matrices containing collagen and Matrigel at 5 and 50% v/v. The final collagen concentration in all gels was 1.0 mg/ml. Gels were prepared by carefully pouring 500 μl of the cell-matrix mixture into wells of a glass-bottomed 6 well plate. The gels were allowed to solidify for 30 min at 37 °C before adding 1.5 ml of cell maintenance culture medium into each well. Cultures were maintained at 37 °C in an atmosphere containing 6% CO2/94% and 100% humidity 5 or 7 days, and the medium was changed every 2 days. Live cell-imaging was conducted with a Leica SP5 microscope (Leica-Microsystems, Germany). Simultaneous reflectance confocal microscopy (RCM) and bright-field images were acquired using a 40×, 1.1 numerical aperture, water immersion objective with separate photomultiplier tubes using the Argon 488 nm laser line. The RCM signal was collected between wavelengths of 478–498 nm with a pinhole size of 57 μm. For additional details see (Barnes et al., 2014).

3.2. Current mathematical models of mammary gland morphogenesis

Several types of mathematical models have been used for the study of mammary gland morphogenesis. These models focus on distinct aspects of this phenomenon, and address a given aspect at a particular time and space scale. These diverse models also focus on different kinds of determinants, some chemical, some mechanical, some both.

Oftentimes the modelers make mathematical hypotheses on the behavior of cells without making explicit the broader biological significance of these hypotheses. Our mathematical model instead is based on general biological principles. Some models seem to implicitly rely on the default state that we propose: that is, cells spontaneously move or proliferate and the model discusses specific constraints on these behaviors. In other models, cells are quiescent without any constraints acting on them and chemicals stimulate proliferation and/or movement without removing constraints. Still, in other models even opposite behaviors co-exist and no explicit attempt to reconcile these opposites is made. In Table 1 we review the way several models deal with cell behavior.

Table 1.

Cell behavior according to current mathematical models of mammary gland morphogenesis.

| Object studied | Modeling cell proliferation | Modeling motility | Implicit default state | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Collagen network remodeling | Not discussed | ECM constrains movement. | Motility | (Harjanto and Zaman, 2013) |

| Collagen and fibroblasts | Not discussed | Cells spontaneously exert forces and move. Stress may prevent motion. | Motility | (Dallon et al., 2014) |

| Acinus in 2D | Limited space prevents proliferation. Although not included in the math model, it is stated that proliferation is regulated by signals/growth factors. | Not discussed | Proliferation (quiescence is invoked the Discussion). | (Rejniak and Anderson, 2008) |

| Acinus in 3D | Only cells adjacent to the basement membrane proliferate. Cells have a proliferative potential that decreases at each division. | Not discussed | Shifts from proliferation to quiescence as time elapses. Not discussed for inner cells. | (Tang et al., 2011) |

| Review on biophysical cell self- assembly | No proliferation | Cells show trend to move modeled by a parameter formally similar to temperature. | If this “temperature parameter” is an intrinsic property of cells, the default state is motility, otherwise quiescence. | (Neagu, 2006) |

| Terminal End Buds | No causal analysis (measured or assessed indirectly). | NA | (Paine et al., 2016) | |

| Epithelial tree | Components resulting from the action of matrix metalloproteinases are inferred to stimulate cell proliferation. | Not discussed | Quiescence | (Grant et al., 2004) |

In these models assumptions on cell behavior are largely ad hoc, varying from one model to another. Occasionally, the model and its interpretation in the Discussion are inconsistent. For example, in Rejniak and Anderson (2008) proliferation is constrained by the available space but it is also attributed to “signals”.

Various models implicitly adopt the premise that the default state of cells is proliferation or motility. Other models (Grant et al., 2004) do not adopt this premise; however they may be reinterpreted by adopting our principles. In the Grant et al. model, the matrix metalloproteinases are assumed to have a positive effect on proliferation by degrading the ECM. Because the authors also infer that the default state is quiescence, they assume that this degradation produces a chemical which stimulates proliferation. A simpler hypothesis that we favor is that this degradation removes the mechanical constraint of the ECM on the default state of cell proliferation with variation and motility. To our knowledge, no model of mammary gland morphogenesis has taken both aspects of our default state into account.

The main aim of this article is to emphasize that making explicit the assumption that the default state is proliferation with variation and motility enables us to model morphogenesis on precise theoretical bases. The models reviewed above focus on different aspects of mammary gland morphogenesis. For instance, models of ECM remodeling focus on fibroblasts and do not discuss epithelial morphogenesis. Several agent-based models focus on the behavior of epithelial cells during acinus formation in conditions that preclude ductal morphogenesis. Finally, other models focus on larger scale organogenesis but do not provide a detailed account of cellular behavior. Determinants of these models are either chemical, mechanical forces or empty space. Note however that in most cases morphogenesis is assumed to be driven by chemical interactions (Iber and Menshykau, 2013). This article will focus on the formation of epithelial structures, mostly ducts but also acini on the basis of mechanical interactions between cells and between cells and the ECM.

Mammary gland morphogenesis in vivo requires an interplay between the epithelial compartment and the stroma which contains fibroblasts, adipocytes and ECM. Our simplified model contains epithelial cells and a stroma devoid of cells but containing the ECM which in vivo would be a product of the stromal cells. The assumption that the ECM is the mechanically important component of the stroma opens the possibility to explore a set of minimal and manageable conditions that allow for a bi-stable determination of acini and ducts, the two structures that characterize the mammary gland parenchyma. In the rest of the text we will discuss all experimental results and mathematical assumptions under the hypothesis that the default state of cells is proliferation with variation and motility.

3.3. From the 3D culture model to a mathematical model

3.3.1. Proliferation

As expected from the default state, breast epithelial cells proliferate maximally in serumless medium. Addition of hormone-free serum to culture medium results in a dose-dependent inhibition of cell proliferation. This is due to the effect of serum albumin, a main constraint for the proliferation of estrogen-target cells. This constraint could be lifted by lowering albumin or serum concentration, a procedure easily performed in 2D cell cultures, or by adding estrogens, which is the natural way the organism uses to neutralize the effect of serum albumin (Sonnenschein et al., 1996).

Additional constraints are those imposed by cell-cell contact, which are weaker in 2D culture than in 3D. This is because 3D structures allow for cell-cell contact in practically all directions, while in 2D these contacts are more restricted. For example, the estrogen-sensitive T47D cell line is inhibited from proliferating when placed in medium containing serum. This constraint is lifted by the addition of estrogen. When placed in 2D culture, the cell number ratio between serum plus estrogen and serum without estrogen is 3.75, while the same experiment performed in 3D culture results in a ratio of 2.5 (Speroni et al., 2014). These data indicate that the organization of cells into epithelial structures constrains cell proliferation more effectively than the one in 2D culture, where cells are not organized into closely packed epithelial structures. Additionally, in 2D cultures cells attach to the bottom of the culture dish, a surface that is exceedingly more rigid than the conditions these very cells encounter within the tissue of origin. In contrast, 3D cultures could be engineered to mimic the rigidity of the tissue of origin.

3.3.2. Motility

In classical mechanics, motion is a consequence of external forces. In biology, the situation is different but compatible with mechanics. Cells need a configuration of forces to be able to move; for example, they need a support to be able to crawl on it, or fibers to which they can attach and pull in order to move. However, unlike inert objects, cells initiate movement on their own. In other words, they are autonomous agents which express their default state (Sonnenschein and Soto, 1999). Cells move unless there are constraints which prevent them from doing so. Reciprocally, a given mechanical force acting upon biological entities such as cells produces clearly different effects than forces acting on inert matter (Soto et al., 2008; Longo and Montévil, 2014). For example, gravity in mechanics is just a force proportional to the mass of the object and oriented towards the center of the earth. In biology, however, gravity becomes a constant constraint, which has not been altered since the origin of life. Biological organization reacts to it in various ways. For example, swim bladders, wings, limbs and tree trunks are responsive to gravitational force but are not explained by it. The behavior of molecules in cells and the overall behavior of tissues and organs are massively impacted when in microgravity conditions (Bizzarri et al., 2014).

The constraints to motility that cells experience in the tissue environment can be modeled in a 3D culture system. In this system, the tissue environment is recreated by the matrix in which the cells are seeded. Cells exert their motility by using filopodia and pseudopodia. When they encounter a structure such as a fiber they can use it for locomotion or pull on it to attach. Breast epithelial cells seeded in a matrix emit projections in all directions soon after seeding (Fig. 1; Video 1). This process allows cell elongation which precedes the formation of ducts (tubular structures) and branching (Barnes et al., 2014). Amorphous, non-fibrilar matrix proteins as well as fibers also oppose migration and cause resistance due to their relative rigidity and their lack of pores (Fig. 2). Breast epithelial cells growing in a non-fibrilar matrix display limited motility and emit short projections into the matrix that retract soon afterwards. Cells rotate and divide resulting in the formation of an acinus, a sphere with a central lumen (Tanner et al., 2012) (Fig. 3; Video 2). Cell movement is also constrained by the pore size of the matrix, this is mostly determined by fiber alignment, fiber density and abundance of non-fibrous matrix materials. Other factors such as pore size and matrix rigidity could contribute to the morphological differences of the epithelial structures. Pore size is bigger in the fibrilar matrix than in the globular matrix (Fig. 2). The globular matrix is stiffer than the fibrilar matrix, however this proved to be a minor contributor to epithelial phenotype compared to collagen fiber distribution (Barnes et al., 2014).

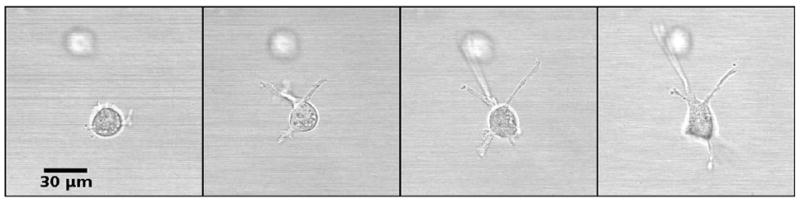

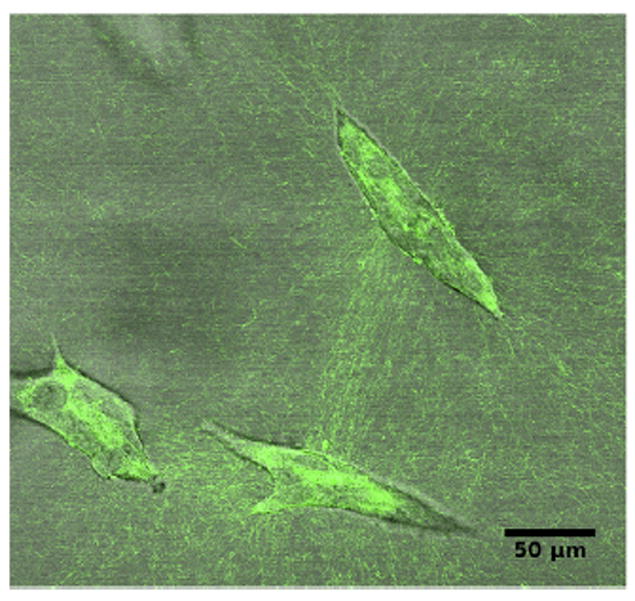

Fig. 1.

Projections of breast epithelial cells seeded in a fibrilar matrix. Soon after seeding cells emit projections in all directions; these projections are involved in collagen organization. Still images from Video 1 at 3, 4, 5 and 6 h after seeding.

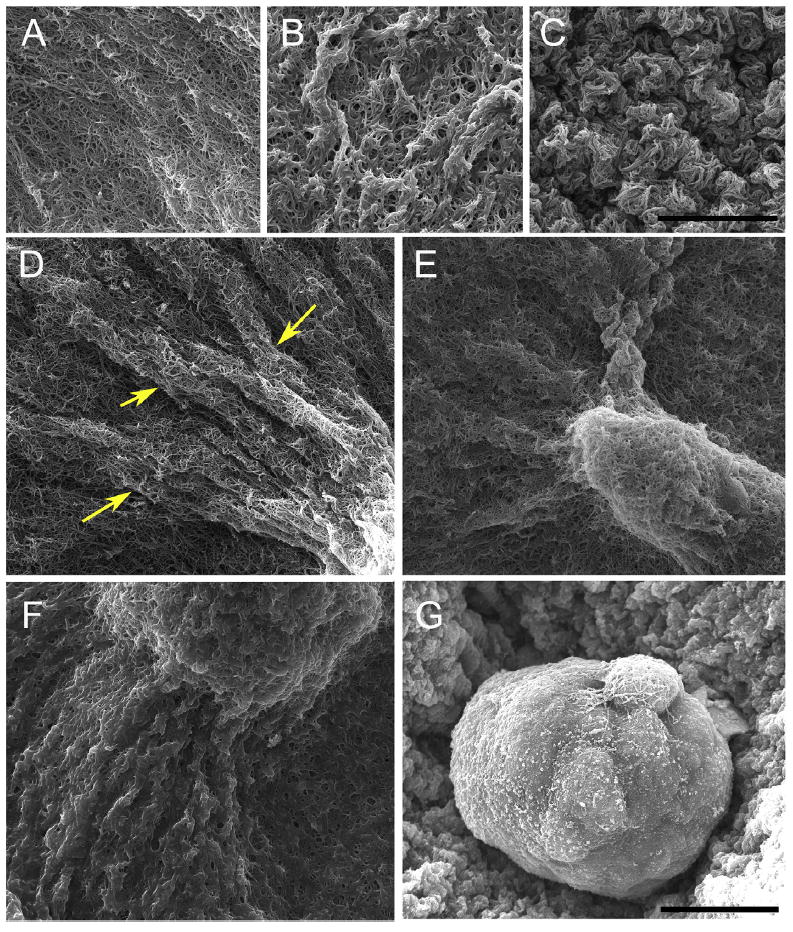

Fig. 2.

SEM images of epithelial structures and their matrix at day 5. (A) Collagen fibers are clearly distinguished in a collagen-only matrix. (B) Addition of 5% Matrigel results in a globular rather than fibrilar matrix. (C) The globular matrix is more compact in 50% Matrigel. (D) Tube-like cell processes (arrows) are observed at the tip of a duct in a collagen-only matrix. (E) Ductal and (F) acinar structures in 5% Matrigel; Matrigel forms a localized coating in areas surrounding the acinus. (G) An acinus grown in 50% Matrigel; collagen fibers are not visible. Scale bar, 10 μm in A to C and 15 μm in D to G. Reproduced with permission from Barnes et al. (2014).

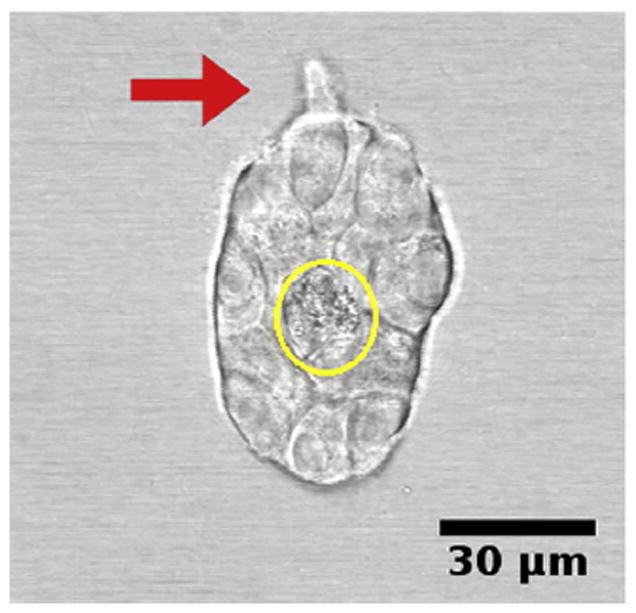

Fig. 3.

Breast epithelial cells forming an acinus in a non-fibrilar matrix at day 4. Cells display limited motility and emit only short projections into the matrix (arrow). Cells rotate and divide resulting in the formation of an acinus, a sphere with a central lumen (circle). Still image from Video 2.

Supplementary data related to this article can be found online at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2016.08.004.

3.3.2.1. Cell adhesion

Cells can adhere to each other after division of their progenitor; they can also attach to any migrant cells they encounter. Once an epithelial structure, such as a duct or an acinus, is formed, adhesion will be maintained as new cells are formed or replaced. Adhesion constrains the motion of cells. During ductal morphogenesis, single cells can detach from the main structure and may also be incorporated back into the structure from which they detached (Fig. 4, Video 3). This phenomenon suggests an environment-sensing strategy as well as a means used by epithelial structures to modify the matrix prior to growth in a certain direction. During lumen formation, cells migrate toward the periphery of the epithelial structure leaving a space that will be filled by fluid.

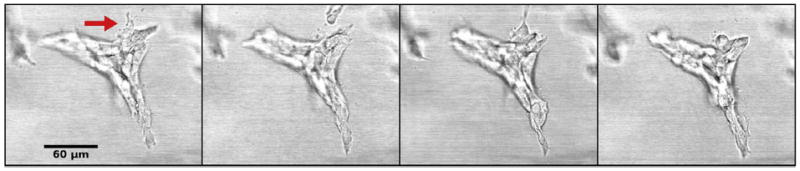

Fig. 4.

Branching duct at day 7 of culture. A cell (arrow) detaches from the main structure and is incorporated back into the same structure. Still images from Video 3, each frame corresponds to one hour.

Supplementary data related to this article can be found online at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2016.08.004.

3.3.3. Determination of the system

The increase in cell number due to the unconstrained default state brings about re-distribution of fluids, reorganization of fibers and a certain degree of matrix compression, and/or matrix degradation. Elongation is accompanied by fiber organization into bundles projecting in the direction of the ductal tip (Barnes et al., 2014). Collagen bundles facilitate the merging of epithelial structures initially positioned at a long distance range (Guo et al., 2012) (Fig. 5, Video 4).

Fig. 5.

Collagen fibers and breast epithelial structures after 6 days in culture. Cells organize collagen in a collagen only matrix and the collagen bundles (green) facilitate the merging of epithelial structures. Still image from Video 4.

Supplementary data related to this article can be found online at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2016.08.004.

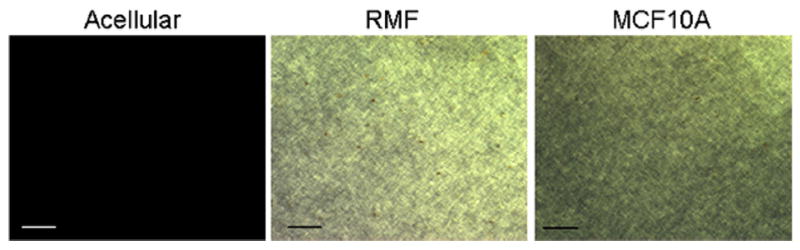

Acellular collagen gels contain small fibers that are not seen using the classical picrosirius red/polarized light method to visualize collagen fibers. However, a similar collagen gel containing cells reveals a very different picture; twenty-four hours after seeding the cells, small yellow fibers are detected (Fig. 6). This experiment shows that cells organize collagen fibers. In other words, cells exert forces upon fibers, and fibers transmit these forces for quite long distances (Guo et al., 2012).

Fig. 6.

Evidence of cell activity on collagen organization. Collagen fibers rearrangement in a fibrillar matrix containing no cells, fibroblasts (RMF) or MCF10A breast epithelial cells, 24 h after seeding. Whole mount picrosirius red staining/polarized light imaging; scale bar 100 μm. Reproduced with permission from Dhimolea et al. (2010).

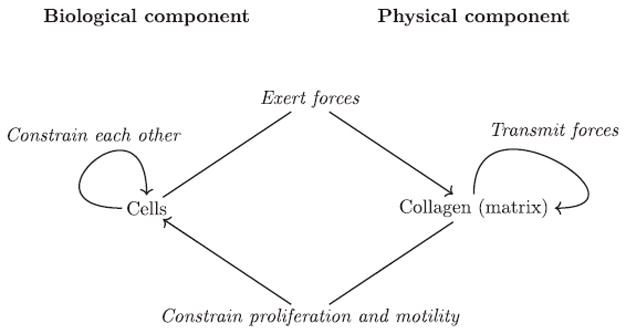

As collagen fibers progressively organize, they constrain the proliferation and motility of cells. These constraints may be positive like those that facilitate cell migration along fibers or negative like the ones hindering migration orthogonally, and those due to “pore” formation when the collagen fibers organize into a network. Additionally, cells constrain other cells mechanically. The reciprocal interactions between the collagen and the cells are illustrated in Fig. 7 which emphasizes the separation of the system into a physical component, the collagen, and a biological component, the cells. In this diagram the behavior of the cells is determined by the default state and the constraints exerted on it.

Fig. 7.

Schematic representation of the determination of the 3D biological model. We analyze morphogenesis as the interaction between a physical and a biological component. The physical component is mostly made out of collagen and is determined by physical principles in the absence of cells. Collagen undergoes spontaneous gel formation; however, its structure does not change much spontaneously after this process. Cells are agents which act upon other cells and collagen fibers organizing them. The formation of epithelial structures by cells is modeled from the default state; cells and collagen constrain this default state.

4. Implementing a model based on these principles

We propose a mathematical model of morphogenesis in 3D cultures that we analyze by computer simulations. In this article this model is used as a proof of concept. A mathematical description of our model is provided in Appendix 1. Our model is based on the principles that we propose for the construction of a theory of organisms. Our theoretical framework restricts what is acceptable in order to model cellular behavior. For example, it is unacceptable for cells to be proliferatively quiescent without an explicit constraint keeping them in this state. Of course, in the presence of a strong constraint cells will become quiescent and will remain as such for the duration of the constraint.

4.1. Components of the model

The 3D culture gel is represented as a lattice, in three dimensions. The model is based on different layers that interact with each other:

A mechanical forces layer. Each elementary cube of our model exerts forces on the adjacent cubes. Forces propagate in space. Their orientation and propagation depends on the orientation of collagen fibers.

A cellular layer, which has three possible states: presence of a live cell, a dead cell (in the case of lumen formation), or no cell, in which case the cube contains ECM.

The collagen layer is approached at a mesoscopic scale and does not represent individual fibers. Each cube of collagen has a main orientation which will transmit forces farther, and this orientation is random in the initial conditions. This orientation is also relevant for cellular behavior (see below). Note that this layer represents the cytoskeleton in the cubes occupied by cells. Collagen tends to align with forces that are exerted on it.

An inhibitory layer. Cells around the lumen produce a short range inhibition of both proliferation and motility. This layer can be interpreted either as the formation of a basal membrane or as a chemical inhibitor. Both aspects are biologically relevant and could be split into two different types of inhibition in future work.

A “nutrient” layer governed by diffusion. Cells consume nutrients. If there are not enough nutrients, cells die leading to lumen formation. The main point here is not to produce an accurate account of lumen formation, but instead to take into account the consequences of lumen formation on morphogenesis as a lumen would disrupt the transmission of forces.

4.2. Cellular behavior

Cells express four different behaviors:

Cells exert forces on each other and on the collagen network. The orientation of these forces is influenced by both the neighboring cells and there is also a random component. The magnitude of the force depends on the content of the neighboring cube. More precisely, the force exerted depends on the position with respect to the cell, the orientation of the cytoskeleton of the cell and the orientation of the collagen fibers in the case of an action upon a collagen fiber or fascicle. Additionally, cells tend to oppose strong mechanical stress.

Cells have a defined generation time and divide, except when there are constraints which prevents them from doing so. The new cell will occupy a random spot. When this spot is already occupied, the cell cannot proliferate; the cell will make another attempt at the next iteration of the simulation loop.

Cells move randomly unless this movement is constrained.

Cells die when they lack nutrients. Unlike the other behaviors, this one is an ad-hoc addition to create a lumen, since steps involved in lumen formation are not well known. There is evidence for cell death and for cell migration, but the cue provoking lumen formation is unknown.

In this analysis, cell motility has two components: the forces exerted by cells and cell movement. Cell movement involves detachment and reattachment to other cells and to the extracellular matrix.

4.3. Constraints on proliferation

Cells tend to proliferate along the direction of forces. The stronger the forces, the stronger the constraint becomes. In the case of three cells being aligned, the one in the middle may be unable to proliferate if there is a force in the direction of their alignment.

Strong mechanical stress slows down proliferation; this constraint is not required for the model to work.

The inhibitory layer prevents proliferation.

4.4. Constraints on cell movement

A strong mechanical stress slows down movement; this is not required for the model to work. Also, as the number of neighboring cells increases, the stronger the effect of cell adhesion, which prevents the cell from initiating movement.

Movement is facilitated when it occurs along collagen fibers.

Movement is facilitated towards other cells.

The inhibitory layer prevents movement.

4.5. Results of implementing the mathematical model

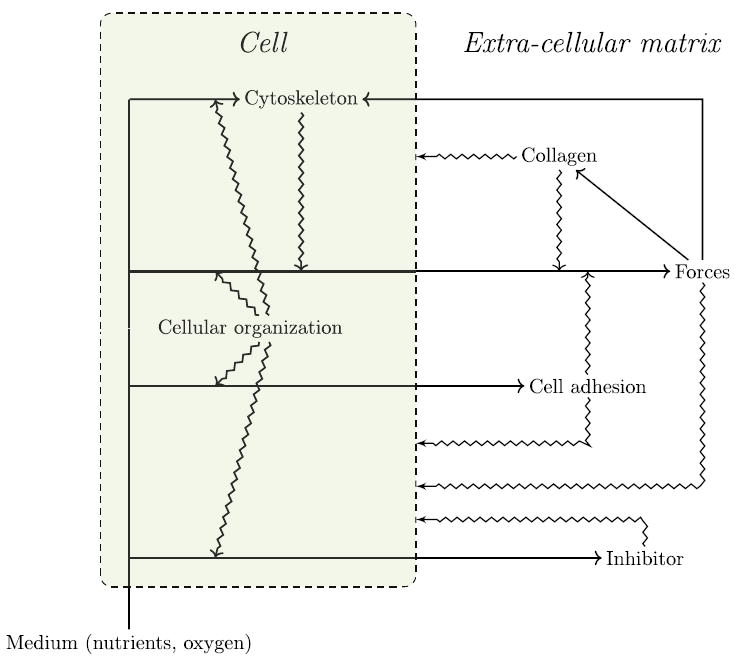

The model that we propose exhibits a circularity that can be interpreted in terms of closure (Fig. 8). This circularity concerns constraints acting on i) processes such as physical forces and ii) directly on the default state.

Fig. 8.

Schematic representation of the theoretical model. Chemical energy and chemicals from the medium are transformed by cells into the constraints at play in the system. Processes of transformation are represented by straight arrows. The action of constraints on these processes are represented by zig-zag arrows. Constraints on the default state point to a cell. All cells in the model are represented by a single cell (green). Note that we single out the cytoskeleton as a particularly relevant aspect of cellular organization in our model. This scheme shows the circularity of the reciprocal interactions and how cells collectively constitute their own constraints leading to morphogenesis.

The implementation of this mathematical model generates biologically relevant results. When in collagen, cells form elongated structures that can be interpreted as ducts. When we remove the effects of collagen’s fibrilar structure, in order to mimic a globular matrix (Matrigel), cells form spherical structures.

4.5.1. Duct formation

A single cell is surrounded by collagen. This cell starts to exert forces on the collagen and organizes it. The cell will proliferate and may move. The epithelial structure acquires additional cells through cell proliferation. Cells move but they mostly stay attached to the structure. Cells in the middle of the structure can neither move nor proliferate. The cells exert forces on each other and on the collagen. This leads to the appearance of a dominant direction in which these forces are exerted and collagen is reorganized. This direction is often that of the forces exerted initially by the first cell and also depends on initial collagen configuration. Motility and proliferation are facilitated along this main direction, while they are inhibited in the direction perpendicular to this force. As a result, the structure acquires an elongated shape. The structure grows following this dynamic until it reaches a size large enough for the lumen to form at the thickest part of the structure, which is close to the initial position of the first cell. In the context of lumen formation the inhibitor constrains proliferation and motility and inhibits the growth in the width of the structure in the vicinity of a lumen. In contrast, the tips of the elongated structure are not inhibited and elongate further without apparent restriction (Fig. 9, Videos 5 and 6).

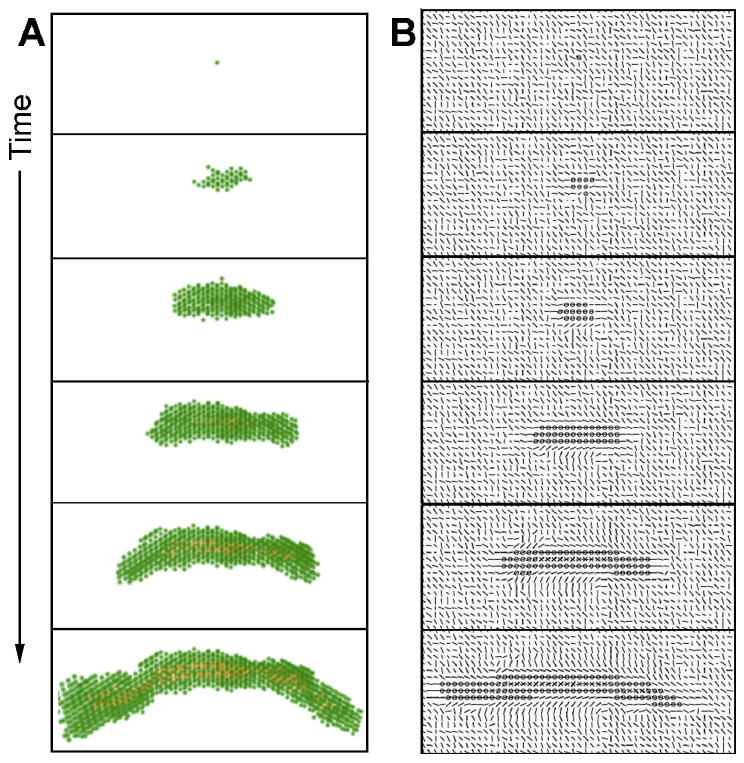

Fig. 9.

Formation of a duct by the mathematical model. A) cells are represented in green and the ductal lumen in orange, in three dimensions and over time. B) depiction of a plane of the model over time. The lines represent collagen orientation; shorter lines mean that the orientation of collagen is mostly along the vertical axis. Circles represent cells, and crosses represent lumen. Cells organize collagen over time by exerting forces, and collagen constrains cell proliferation and motility. These interactions lead to the emergence of a main direction of growth. See also corresponding Videos 5 and 6.

Supplementary data related to this article can be found online at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2016.08.004.

In some cases, the constraints leading to duct formation can become disorganized at one of the tips. In such case, the main direction of forces exerted may change, leading to a change in the growth direction of the duct. In other cases, this disorganization leads to a bifurcation in the main direction of the constraints and to branching (Videos 7 and 8). These phenomena will be the subject of further studies.

Supplementary data related to this article can be found online at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2016.08.004.

4.5.2. Acinus formation

The addition of Matrigel to a collagen matrix changes the gel properties by coating the collagen fibers and thus hindering fiber organization (Barnes et al., 2014). In this case, collagen fibers are not accessible to the epithelial cells, which prevents the establishment of a main direction in the forces exerted by the cells. Moreover, these forces are exerted exclusively on cells rather than on fibers. As a result, the epithelial structure grows in an isotropic manner, and when the lumen is formed and the inhibitor is secreted, all cells are constrained. The acinus being formed is a smooth structure due to the constrained motility of cells, each of which is constrained by the many cells surrounding them (Fig. 10, Video 9).

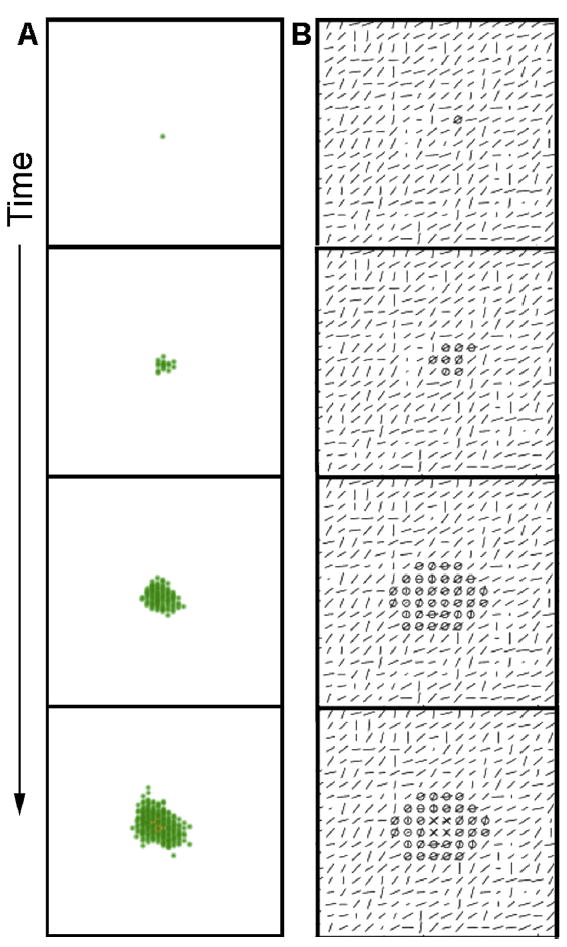

Fig. 10.

Formation of an acinus by the mathematical model. A) cells are represented in green and the lumen in orange, in 3 dimensions over time. B) depiction of a plane of the model over time. The lines represent collagen orientation; shorter lines mean that the orientation of collagen is along the vertical axis. Circles represent cells, and crosses represent lumen. Here we remove the interactions between the ECM and the cells in order to mimic the effect of Matrigel. In this condition, the cells proliferate and move in an isotropic manner leading to the formation of a rounded structure. See also corresponding Video 9.

Supplementary data related to this article can be found online at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2016.08.004.

5. The in vitro system and the organism

How faithfully does this in vitro system represent a phenomenon occurring inside the organism? By accepting the reciprocal relationship between the whole (organism) and its parts, it is difficult to conceive that a sub-system would operate in a biologically relevant fashion when outside the organism. However, there are examples in embryology of the relative autonomy of parts at a particular point in space-time, as for example, the autonomy of limb morphogenesis upon transplantation of the limb morphogenetic field to an ectopic location. Additionally, parceling a whole does not prevent us from ascertaining whether or not the in vitro process arrives at similar outcomes as those observed in vivo.

Which constraints are required for a relevant model of tissue morphogenesis?

Biological meaning is construed by applying similar constraints to those which operate in vivo and which seem to play a role in the determination of the phenomenon. In this way, we can “reduce” the number of constraints to those necessary to answer our specific question. Deviations from expected results may potentially indicate additional constraints which could then be identified.

Constraints that are absolutely required to allow the cells to continue being alive (pH, nutrients, temperature) and to express their default state in conditions that replicate as much as possible the conditions present in the organism. The “optimization” of these basal conditions is done experimentally by ascertaining that the cells can proliferate as fast as possible and that the cellular phenotype that we wish to study is obtained. This is done in 2D cultures.

Another consideration is the historicity and specificity of biological systems. For example, fibroblasts to be used in a 3D culture of the mammary gland are isolated from human breast tissue and used within 6 passages to avoid excessive deviation from the in situ condition. Along the same lines, established epithelial cells are maintained in standardized conditions that result in the reproducibility of the phenomenon studied (i.e., duct formation) and the cell phenotype (i.e., response to a given hormone).

In vitro 3D models allow researchers to manipulate constraints beyond the range operating in vivo. That is, constraints are determined by the organism and its parts, while in the in vitro model the researcher also plays a direct role in modifying these constraints and parameterizing them. For example, we can manipulate the rigidity of the mammary gland model to that of bone, and learn how rigidity affects shape beyond the limits imposed by the organism (Weaver et al., 1995). This type of manipulation revealed that high rigidity inhibits lumen formation and makes epithelial structures disorganize in a way reminiscent of neoplasms (Paszek et al., 2005).

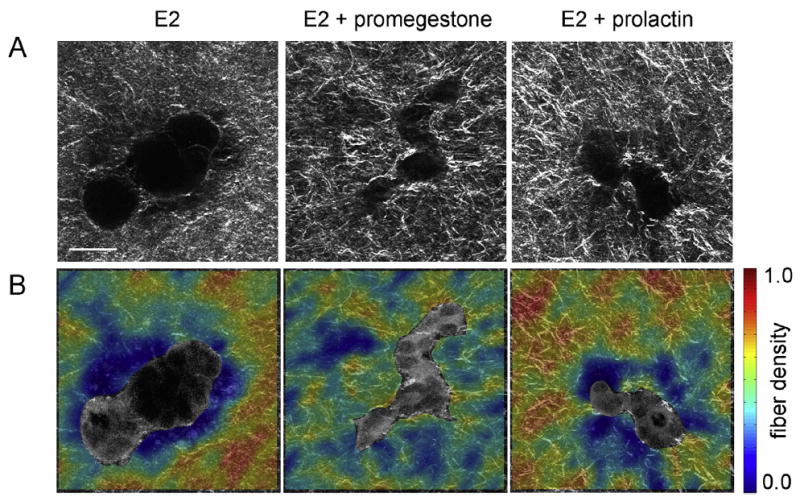

Specific organism level constraints induce the tissue to undergo morphological changes required for proper organ function at the right time. Hormone action on the mammary gland is an example of this. At the onset of puberty, estrogen influences the formation of TEBs, the structure at the end of the ducts that invades the stroma and guides ductal growth until the ductal tree fills the fat pad. Progesterone promotes side-branching and during pregnancy prolactin facilitates acinar development in preparation for lactation. A classical biochemical interpretation would reduce the phenomenon to a hormone-receptor interaction triggering signaling pathways inside the cell. However, this approach does not have the capacity to explain the shape changes resulting from these hormonal influences. From the tissue perspective, exposure to hormones leads to changes in collagen fiber organization which enable the cells to generate various epithelial organization patterns. In a hormone-sensitive 3D culture model, epithelial structures resulting from exposure to estrogen in combination with a progestogen or prolactin were more irregular in shape than the elongated, smooth structures resulting from exposure to estrogen alone. Consistently, combined hormone treatment resulted in higher collagen density variability within 20 μm from the epithelial structure compared to E2 alone (Speroni et al., 2014) (Fig. 11).

Fig. 11.

Effect of exposure to hormones on epithelial morphogenesis. Hormones acting on cells generate changes in collagen fiber organization which enable the cells to generate various epithelial organization patterns. Hormone-sensitive epithelial structures resulting from exposure to estrogen (E2) in combination with promegestone or prolactin were more irregular in shape than the elongated, smooth structures resulting from exposure to E2 alone. Consistently, combined hormone treatment resulted in higher collagen density variability within 20 μm from the epithelial structure compared to E2 alone. (A) Second harmonic generation (SHG) images, collagen fibers in white; (B) fiber density maps on merged SHG and two-photon excited fluorescence channels. Scale bar: 50 μm. Reproduced with permission from Speroni et al. (2014).

6. Conclusions

We posited that experimental research guided by the global theoretical approach that we are proposing would be different from that of the prevailing ones which are mostly guided by the metaphors of information, signal and program borrowed from mathematical information theories (Longo et al., 2012). Often times, modelers entering biological research treat biological objects as if they were either physical objects or computer programs. In this issue, we have presented critiques to these approaches and suggested biological singularities that have to be taken into consideration when constructing a biological theory (Longo and Soto, 2016; Longo et al., 2015). On the one hand, the metaphorical use of information pushes the experimenter to seek causality in terms of discrete structures, namely molecules, in particular DNA. This view precludes physical “constraints”, like the ones analyzed here, to causally contribute to the generation and maintenance of the organism unless they are digitally encoded as molecular signs. On the other hand, biophysical approaches involve hypotheses which are not sound in biology, such as optimization principles in the behavior of cells. The approach adopted herein is based on two of the principles proposed as foundations for a theory of organisms, namely, the default state and organizational closure. We explored whether it would be possible and informative to model epithelial glandular morphogenesis from these biological principles, rather than the usual procedure of transferring mathematical structures developed for the understanding of physical phenomena into biological ones or proposing that cells follow a program. It is worth stressing that the former represents true mathematical modeling which is based on the theoretical framework of the discipline to which the modeled phenomenon pertains, while the latter, properly described as imitation, uses principles from one discipline and applies them to another without a critical appraisal of their theoretical meaning when transported into a different theoretical context.

In this initial modeling effort, applying the two principles (default state and constraints leading to closure) were sufficient to show the formation of ducts and acini. Cells generated forces that were transmitted to neighboring cells and collagen fibers, which in turn created constraints to movement and proliferation (Figs. 7 and 8). Additionally, constraints to the default state are sufficient to explain ductal and acinar formation, and point to a target of future research, namely, the inhibitors of cell proliferation and motility which in this mathematical model are generated by the epithelial cells. Finally, the success of this modeling effort performed as a “proof of principle” opens the possibility for a step-wise approach whereby additional constraints imposed by the tissue (e.g., additional cell types) and the organism (e.g., hormones) could be assessed in silico and rigorously tested by in vitro and in vivo experiments.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was conducted as part of the research project “Addressing biological organization in the post-genomic era” which is supported by the International Blaise Pascal Chairs, Region Ile de France (AMS: Pascal Chair 2013). Additional support to AMS was provided by Grant R01ES08314 from the U. S. National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences and Mael Montévil was supported by Labex “Who am I?”, Laboratory of Excellence No. ANR-11-LABX-0071. The funders had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. The authors are grateful to Cheryl Schaeberle for her critical input and Clifford Barnes for image acquisition.

Footnotes

Appendix A. Mathematical description of the model

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2016.08.004.

The authors have no competing financial interests to declare.

References

- Balinsky BI. On the prenatal growth of the mammary gland rudiment in the mouse. J Anat. 1950;84:227–235. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes C, Speroni L, Quinn K, Montévil M, Saetzler K, Bode-Animashaun G, McKerr G, Georgakoudi I, Downes S, Sonnenschein C, Howard CV, Soto AM. From single cells to tissues: interactions between the matrix and human breast cells in real time. PLoS One. 2014;9:e93325. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0093325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bizzarri M, Cucina A, Palombo A, Masiello MG. Gravity sensing by cells: mechanisms and theoretical grounds. Rend Fis Acc Lincei. 2014;25(Suppl 1):S29–S38. [Google Scholar]

- Brisken C, O’Malley B. Hormone action in the mammary gland. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2010;2:a003178. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a003178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dallon JC, Evans EJ, Ehrlich P. A mathematical model of collagen lattice contraction. J R Soc Interface. 2014;11:20140598. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2014.0598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhimolea E, Maffini MV, Soto AM, Sonnenschein C. The role of collagen reorganization on mammary epithelial morphogenesis in a 3D culture model. Biomaterials. 2010;31:3622–3630. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.01.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant MR, Hunt CA, Xia L, Fata JE, Bissell MJ. Modeling mammary gland morphogenesis as a reaction-diffusion process. Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society, JEMBS ’04 26th Annual International Conference of the IEEE; 2004. pp. 679–682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo CL, Ouyang M, Yu JY, Maslov J, Price A, Shen CY. Long-range mechanical force enables self-assembly of epithelial tubular patterns. Proc Nat Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:5576–5582. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1114781109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harjanto D, Zaman MH. Modeling extracellular matrix reorganization in 3D environments. PLoS One. 2013;8:e52509. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0052509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iber D, Menshykau D. The control of branching morphogenesis. Open Biol. 2013;3:130088. doi: 10.1098/rsob.130088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause S, Jondeau-Cabaton A, Dhimolea E, Soto AM, Sonnenschein C, Maffini MV. Dual regulation of breast tubulogenesis using extracellular matrix composition and stromal cells. Tissue Eng Part A. 2012;18:520–532. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2011.0317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause S, Maffini MV, Soto AM, Sonnenschein C. A novel 3D in vitro culture model to study stromal-epithelial interactions in the mammary gland. Tissue Eng Part C Methods. 2008;14:261–271. doi: 10.1089/ten.tec.2008.0030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longo G, Miquel P-A, Sonnenschein C, Soto AM. Is information a proper observable for biological organization? Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 2012;109:108–114. doi: 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2012.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longo G, Montévil M. From physics to biology by extending criticality and symmetry breakings. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 2011;106:340–347. doi: 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2011.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longo G, Montévil M. Perspectives on Organisms: Biological Time, Symmetries and Singularities. Springer; Berlin: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Longo G, Montévil M, Sonnenschein C, Soto AM. In search of principles for a theory of organisms. J Biosci. 2015;40:955–968. doi: 10.1007/s12038-015-9574-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longo G, Soto AM. Why do we need theories? Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 2016;122:4–10. doi: 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2016.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miquel PA, Hwang SY. From physical to biological individuation. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 2016;122:51–57. doi: 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2016.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montévil M, Mossio M, Pocheville A, Longo G. Theoretical principles for biology: variation. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 2016;122:36–50. doi: 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2016.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mossio M, Montévil M, Longo G. Theoretical principles for biology: organization. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 2016;122:24–35. doi: 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2016.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neagu A. Computational modeling of tissue self-assembly. Mod Phys Lett. 2006;20:1217. [Google Scholar]

- Paine I, Chauviere A, Landua J, Sreekuman A, Cristini V, Rosen J, Lewis MT. A geometrically-constrained mathematical model of mammary gland ductal elongation reveals novel cellular dynamics within the terminal end bud. PLoS Comput Biol. 2016;12:e1004839. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1004839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paszek MJ, Zahir N, Johnson KR, Lakins JN, Rozenberg GI, Gefen A, Reinhart-King CA, Margulies SS, Dembo M, Boettiger D, Hammer DA, Weaver VM. Tensional homeostasis and the malignant phenotype. Cancer Cell. 2005;8:241–254. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perret N, Longo G. Reductionist perspectives and the notion of information. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 2016;122:11–15. doi: 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2016.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rejniak KA, Anderson AR. A computational study of the development of epithelial acini: II. Necessary conditions for structure and lumen stability. Bull Math Biol. 2008;70:1450–1479. doi: 10.1007/s11538-008-9308-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson GW, Karpf ABC, Kratochwil K. Regulation of mammary gland development by tissue interaction. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia. 1999;4:9–19. doi: 10.1023/a:1018748418447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonnenschein C, Soto AM. Carcinogenesis explained within the context of a theory of organisms. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 2016;122:70–76. doi: 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2016.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonnenschein C, Soto AM. The Society of Cells: Cancer and Control of Cell Proliferation. Springer Verlag; New York: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Sonnenschein C, Soto AM, Michaelson CL. Human serum albumin shares the properties of estrocolyone-I, the inhibitor of the proliferation of estrogen-target cells. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 1996;59:147–154. doi: 10.1016/s0960-0760(96)00112-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soto AM, Longo G, Montévil M, Sonnenschein C. The biological default state of cell proliferation with variation and motility, a fundamental principle for a theory of organisms. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 2016;122:16–23. doi: 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2016.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soto AM, Sonnenschein C. Emergentism as a default: cancer as a problem of tissue organization. J Biosci. 2005;30:103–118. doi: 10.1007/BF02705155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soto AM, Sonnenschein C. The tissue organization field theory of cancer: a testable replacement for the somatic mutation theory. BioEssays. 2011;33:332–340. doi: 10.1002/bies.201100025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soto AM, Sonnenschein C, Miquel P-A. On physicalism and downward causation in developmental and cancer biology. Acta Biotheor. 2008;56:257–274. doi: 10.1007/s10441-008-9052-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speroni L, Whitt GS, Xylas J, Quinn KP, Jondeau-Cabaton A, Georgakoudi I, Sonnenschein C, Soto AM. Hormonal regulation of epithelial organization in a 3D breast tissue culture model. Tissue Eng Part C Methods. 2014;20:42–51. doi: 10.1089/ten.tec.2013.0054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang J, Enderling H, Becker-Weimann S, Pham C, Polyzos A, Chen CY, Costes SV. Phenotypic transition maps of 3D breast acini obtained by imaging-guided agent-based modeling. Integr Biol. 2011;3:408–421. doi: 10.1039/c0ib00092b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanner K, Mori H, Mroue R, Bruni-Cardoso A, Bissell MJ. Coherent angular motion in the establishment of multicellular architecture of glandular tissues. Proc Nat Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:1973–1978. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1119578109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Fraassen BC. Laws and Symmetry. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Vandenberg LN, Maffini MV, Wadia PR, Sonnenschein C, Rubin BS, Soto AM. Exposure to environmentally relevant doses of the xenoestrogen bisphenol-A alters development of the fetal mouse mammary gland. Endocrinology. 2007;148:116–127. doi: 10.1210/en.2006-0561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weaver VM, Howlett AR, Langton-Webster B, Petersen OW, Bissell MJ. The development of a functionally relevant cell culture model of progressive human breast cancer. Semin Cancer Biol. 1995;6:175–184. doi: 10.1006/scbi.1995.0021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.