Abstract

Insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-I) is the key regulator of fetal growth. IGF-I bioavailability is markedly diminished by IGF binding protein-1 (IGFBP-1) phosphorylation. Leucine deprivation strongly induces IGFBP-1hyperphosphorylation, and plays an important role in fetal growth restriction (FGR). FGR is characterized by decreased amino acid availability, which activates the amino acid response (AAR) and inhibits the mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathway. We investigated the role of AAR and mTOR in mediating IGFBP-1 secretion and phosphorylation in HepG2 cells in leucine deprivation. mTOR inhibition (rapamycin or raptor+rictor siRNA), or activation (DEPTOR siRNA) demonstrated a role of mTOR in leucine deprivation-induced IGFBP-1 secretion but not phosphorylation. When the AAR was blocked (U0126, or ERK/GCN2 siRNA), both IGFBP-1 secretion and phosphorylation (Ser101/Ser119/Ser169) due to leucine deprivation were prevented. CK2 inhibition by TBB also attenuated IGFBP-1 phosphorylation in leucine deprivation. These results suggest that the AAR and mTOR independently regulate IGFBP-1 secretion and phosphorylation in leucine deprivation.

Keywords: Leucine deprivation, HepG2 cells, IGFBP-1 phosphorylation, AAR, mTOR

1. Introduction

Fetal Growth Restriction (FGR) is primarily a result of placental insufficiency, i.e. the inability of the placenta to effectively deliver nutrients and oxygen to the fetus1. A lack of adequate nutritional supply results in reduced overall fetal growth in favour of channelling limited resources to preserving brain function2. FGR affects ~6 to 8% of all pregnancies1. Severe FGR babies are born under the 3rd percentile of expected birth weight and are predisposed to greater risks of childhood and adult metabolic, cardiovascular, and neurological complications2. The mechanisms by which the fetus signals nutrient deficiency to attenuating fetal growth are not well understood.

Insulin-like growth factor I (IGF-I) is the key regulator of fetal growth. Deficiency in IGF-I bioavailability and subsequent bioactivity is associated with FGR onset3. The bioavailability of IGF-I is regulated by IGF binding protein-1 (IGFBP-1)4, which is secreted by the fetal liver and is the key circulating fetal IGFBP during gestation5. IGFBP-1 functions by binding IGF-I and sequestering it from its receptor, IGF-1R, consequently preventing it from transducing its mitogenic signals6. IGF-I bioavailability is strongly influenced by the phosphorylation status of IGFBP-17, with hyperphosphorylation increasing the binding affinity of IGFBP-1 for IGF-I, resulting in increased sequestering of IGF-I and its decreased bioavailability8–10.

Human FGR fetuses often have decreased fetal circulating levels of essential amino acids, such as leucine1,11. In our laboratory, we have previously demonstrated that leucine deprivation triggered hyperphosphorylation of IGFBP-1 in HepG2 cells12, which markedly increases the affinity of IGFBP-1 for IGF-I (~30-fold) and decreases IGF-I bioavailability13. Although modest increases in IGFBP-1 levels were found in HepG2 cells cultured in lower leucine concentrations (70 and 140 μM Leu), leucine deprivation (0 μM) distinctly increased total IGFBP-1 levels as well as IGFBP-1 phosphorylation compared to the control (450 μM leucine)12. Further, elevated circulating IGFBP-1 and decreased IGF-I are strongly correlated with FGR onset14–16. More recently, we have demonstrated in a baboon model that FGR is associated with IGFBP-1 hyperphosphorylation in the human fetal circulation and in the fetal liver17. These data are consistent with the possibility that increased phosphorylation of IGFBP-1 plays an important role in FGR pathogenesis. We have also previously found that inhibition of fetal hepatic mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR) signaling decreases IGF-I bioavailability by activating casein kinase II (CK2), providing a strong link between increased IGFBP-1 phosphorylation and FGR17. However, the mechanisms underlying IGFBP-1 hyperphosphorylation in leucine deprivation remain to be established.

FGR is characterized by decreased amino acid availability, which activates the amino acid response (AAR) and inhibits mTOR signaling18. The AAR signaling pathway is highly responsive to changes in amino acid availability, and mTOR signaling is also sensitive to oxygen and glucose levels19. mTOR controls cell growth and metabolism, which is primarily mediated by effects on protein translation20. mTOR exists in two complexes, mTOR Complex 1 (mTORC1) and 2, with the protein raptor associated to mTORC1 and rictor associated to mTORC2. mTORC1 phosphorylates p70-S6K and 4E-BP1, resulting in increased protein translation20,21. mTORC2 phosphorylates Akt and PKCα and regulates cell metabolism and survival21. Amino acids, oxygen and growth factor signaling activate mTORC1 signaling22,23. Rapamycin is a specific mTORC1 inhibitor, although recent reports, including our own, indicate that rapamycin also can inhibit mTORC2 after prolonged incubation at high doses17,21.

The AAR pathway is activated under conditions of cellular nutrient stress18,24–26. General control non-derepressible 2 (GCN2) is the key sensor of cellular nutrient status, which is activated upon sensing excess uncharged cytoplasmic tRNAs27,28. Leucine deprivation activates and phosphorylates GCN2 at Thr898 which subsequently phosphorylates eukaryotic initiation factor 2 (eiF2) at Ser51 of the alpha subunit (eiF2α)29. Phosphorylated eiF2α (Ser51) proceeds to inhibit eIF2B activity and therefore overall global protein synthesis while concurrently promoting the translation of certain stress-responsive mRNAs, including activating transcription factor 4 (ATF4)27. ATF4 is a critical stress-responsive transcription factor, which, when synthesized, promotes the transcription of several growth-arresting genes. eiF2α phosphorylation and total ATF4 expression levels are therefore functional readouts of AAR activity. Regulation of IGFBP-1 secretion and phosphorylation by the AAR signaling pathway has not previously been reported in any tissue.

In this study, we hypothesized that inhibition of mTOR signaling and AAR activation increase IGFBP-1 secretion and phosphorylation in response to amino acid deprivation. We used a HepG2 cell line as a model system for human fetal hepatocytes to explore mechanistic links between mTOR and AAR signaling and IGFBP-1 phosphorylation under leucine deprivation (0 μM) and with leucine (450 μM). We studied the secretion and phosphorylation (Ser101, Ser119 and Ser169) of IGFBP-1 in HepG2 cells in response to mTOR inhibition (rapamycin) or AAR inhibition (U0126). Alternatively, cells were transfected with siRNA targeting raptor+rictor or DEP domain-containing mTOR-interacting protein (DEPTOR) (to inhibit or activate mTORC1 and C2, respectively), and ERK and/or GCN2 (to inhibit ERK-mediated AAR) in cells cultured with or without leucine. Finally, we verified that changes in IGFBP-1 phosphorylation under leucine deprivation translate to altered IGF-I bioactivity by employing an IGF-IR autophosphorylation assay, which supported the functional significance of our findings.

2. Methods

2.1 Cell culture

Human hepatocellular carcinoma cells (HepG2), purchased from ATCC (Mananassas, VA), were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium with nutrient mixture F-12 (DMEM/F-12) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Invitrogen Corp., Carlsbad, CA). Cells were incubated at 37°C in 20% O2 and 5% CO2.

2.2 Leucine deprivation

HepG2 cells were treated in specialized DMEM:F12 selectively deprived and restored of specific amino acids as previously reported12. Cells were cultured in the specialized media either deprived (0 μM leucine) or supplemented with 450 μM leucine and incubated as described previously.

Cells were cultured in leucine plus or leucine deprived media during rapamycin (100 nM), U0126 (10 μM), or TBB (1 μM) treatment or following transfection with siRNA. Cell media and cell lysate were collected following 24 hour (chemical treatments) or 72 hour (siRNA treatments) exposure to the specialized media.

2.3 Inhibitor treatments

HepG2 cells were plated at 75% confluence in 12-well culture dishes for 24 hours and starved for 6 hours in 2% FBS (DMEM:F12) prior to treatments with chemical inhibitors. As previously reported17, HepG2 cells were subject to rapamycin dose-dependency and subsequently treated in 100 nM rapamycin for 24 hours. HepG2 cells were also subject to 10μM U0126 or 1 μM TBB for 24 hours after assessment via dose-dependency experiments (data not shown) post-6 hour starvation. After treatments, cell media and cell lysate were prepared as previously17,30–32 and stored at −80°C.

2.4 RNA interference silencing

HepG2 cells were plated at 65% confluence in 12-well culture plates. Silencing using siRNA against raptor+rictor, DEPTOR, GCN2 (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA) or ERK (Cell Signaling Technologies, Beverly, MA, USA) in HepG2 cells was achieved using transfection17 with 100 nM siRNA and 5 μL Dharmafect transfection reagent 4 (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL, USA) in regular, serum free DMEM:F12. To simultaneously ensure maximal silencing and maximize cell survival, the transfected cell media was replaced after 24 hours with specialized leucine plus or leucine deprived media and studied after 72 hours (96 hours following transfection). Western immunoblot analysis was used to determine the efficiency of target silencing.

2.5 Cell viability assay

We tested the effect of leucine deprivation, U0126, and TBB treatments on cell viability using the Trypan Blue exclusion assay to ensure these treatments did not sacrifice cell viability. Following leucine deprivation, U0126, and TBB treatments, cells were trypsinized and re-suspended in 10% FBS media. Cell suspensions were diluted 1:1 with 0.4% trypan blue and counted with the Countess Automated Cell Counter (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA). A measure of live/total cells was used as an indicator of cell survival.

2.6 SDS-PAGE and Western Blotting

Equal amounts of cell lysate protein (35–50 μg) were separated on SDS-PAGE gel to determine total expression and phosphorylation of p70-S6K at Thr389, Akt at Ser473, ERK at Thr202/Tyr204, eiF2α at Ser51, GCN2 at Thr898, and pIGF-1R β at Tyr1135, as well as total expression levels of siRNA target proteins, ATF4 and β-actin. IGFBP-1 secretion and phosphorylation (30–40 μl) at Ser101, 119 and 169 by HepG2 cells were determined using equal volume of cell media.

For blocking nitrocellulose membranes in immunoblot analyses, either 5% skim milk or 5% BSA was diluted in Tris-buffered saline (TBS) plus 0.1 % Tween-20 and shaken with blots for 1 hour. All primary antibodies were obtained from Cell Signaling Technologies (Beverly, MA, USA) with the exception of monoclonal antihuman IGFBP-1 (mAb 6303) (Medix Biochemica, Kauniainen, Finland), phospho- and total GCN2 (Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA). Custom IGFBP-1 polyclonal antibodies targeting Ser101, Ser119, and Ser169 (generated at YenZyme Antibodies LLC, San Francisco, CA, USA) have been previously validated and used to detect phosphorylation of IGFBP-1 in cell media blots. Primary antibodies were all used at a dilution of 1:1000, and peroxidase-labelled goat-anti mouse or goat-anti rabbit antibodies (1:10000, BioRad Laboratories Inc.) were used as secondary antibodies. Band intensities were determined using densitometry in Image Lab (Beta 3) software (BioRad).

2.7 IGF-I receptor activation assay

P6 mouse embryo fibroblast cells that over-express human IGF-1R33(a gift from Dr. R. Baserga, Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia, PA) were cultured in DMEM:F12 with sodium pyruvate supplemented with 10% FBS. Treatments were performed in FBS-free conditions.

The P6 cell bioassay was performed as previously described30. Aliquots of HepG2 cell media from various treatments containing equal concentrations of IGFBP-1 were buffer-exchanged to P6 cell media and incubated with rhIGF-I for two hours at room temperature. P6 cells were treated for 10 minutes with the P6 media containing IGFBP-1/IGF-I complexes. Cells were subsequently lysed and samples were separated using SDS-PAGE gels and immunoblot analysis was performed to asses IGF-1R autophosphorylation using phosphosite-specific IGF-1Rβ (Tyr1135) primary antibody.

2.8 Data presentation and statistics

Data was analysed using GraphPad Prism 5 (Graph Pad Software Inc., CA). For each quantified protein, the mean density of the control sample bands was assigned an arbitrary value of 1, and individual densitometry values were expressed relative to this mean. We employed One-way analysis of variance with Dunnet’s Multiple Comparison Post-Test and expressed results as the mean ± SEM. Significance was accepted at *p<0.05.

3. Results

3.1 Rapamycin and/or leucine deprivation inhibit mTOR signaling

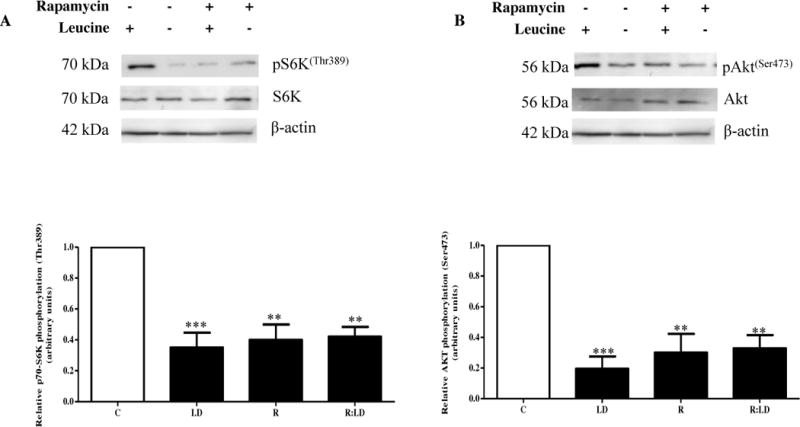

First, we assessed changes in mTORC1 and C2 signaling in response to leucine deprivation and rapamycin as a pharmacological inhibitor. Based on our previous dose dependency data12 for leucine and rapamycin concentrations, we cultured HepG2 cells in media with leucine (450 μM) or deprived of leucine (0 μM), with or without rapamycin (100 nM). We assessed changes in mTORC1 and C2 signaling activity in response to leucine deprivation and/or rapamycin by investigating changes in phosphorylation of downstream effectors p70-S6K at Thr389 and Akt at Ser473 as functional readouts of mTORC1 and C2 activity, respectively.

As evidenced in Figure 1A–B, we noted a significant decrease in mTORC1 and C2 signaling by leucine deprivation, rapamycin treatment, and leucine deprivation and rapamycin combined, indicated by decreased phosphorylation of p70-S6K at Thr389 (−60%) and Akt at Ser473 (−65–70%) under these three treatments. These data demonstrate that both mTORC1 and C2 activity are significantly inhibited by rapamycin. In addition, leucine deprivation inhibited mTORC1 and C2 activity to the same extent as rapamycin with no additive effect when the two treatments were combined (Figure 1A–B), supporting that the degrees to which mTORC1 and C2 were inhibited were not significantly different between treatments.

Figure 1. The effect of rapamycin and/or leucine deprivation on IGFBP-1 secretion and phosphorylation.

HepG2 cells were treated with rapamycin (100 nM) and cultured in leucine plus (450 μM Leu) or leucine deprived (0 μM) media for 24 hours (n=3 each).

A. A representative immunoblot of HepG2 cell lysate assayed for S6K (Thr389) phosphorylation. Equal amounts of total protein (35 μg) were loaded per well. Rapamycin and leucine deprivation both separately inhibited mTORC1 activity. Combined leucine deprivation+rapamycin did not further prevent S6K phosphorylation than either treatment alone. B. A representative immunoblot of HepG2 cell lysates assayed for Akt (Ser473) phosphorylation. Equal protein (35 μg) was loaded. Both rapamycin and leucine deprivation separately and together inhibited mTORC2 activity, evidenced through reduced Akt (Ser 473) phosphorylation to the same extent in all treatments. C. A representative western immunoblot of HepG2 cell media displaying total IGFBP-1 secretion in control, leucine deprivation, rapamycin, and combined leucine deprivation+rapamycin treatments. Equal aliquots of cell media were loaded per well. Leucine deprivation and rapamycin treatment both significantly induced IGFBP-1 secretion to the same extent, and combined treatment did not display an additive effect in total IGFBP-1 output. D–F. Representative western immunoblots of control, leucine deprivation, rapamycin, and leucine deprivation+rapamycin HepG2 cell media assayed for IGFBP-1 phosphorylated at Ser101, Ser119, and Ser169. Equal amounts of cell media were loaded per well. Leucine deprivation and rapamycin both induced IGFBP-1 phosphorylation, although the effect was significantly greater in leucine deprivation regardless of the presence of rapamycin. Combined leucine deprivation and rapamycin treatments induced IGFBP-1 phosphorylation to same extent as leucine deprivation alone. Values are displayed as mean + SEM. *p<0.05, **p=0.001–0.05, ***p <0.001 versus control; One-way analysis of variance, Dunnet’s Post-Test. n=3.

3.2 mTOR inhibition increases IGFBP-1 secretion but not IGFBP-1 phosphorylation in leucine deprivation

To test our hypothesis that mTOR signaling is responsible for changes in IGFBP-1 secretion and phosphorylation in amino acid limitation, we first investigated the effects of rapamycin and leucine deprivation on IGFBP-1 secretion and phosphorylation in HepG2 cells singly and combined. To examine these changes, we resolved equal volumes of HepG2 cell media from rapamycin- treated cells with leucine (450 μM) or in leucine deprived (0 μM) conditions (Figure 1C–F). As demonstrated in Figure 1C, IGFBP-1 secretion was increased (+400%) both in leucine deprivation and rapamycin and this effect was not additive when both treatments were combined. To investigate whether this effect was consistent with IGFBP-1 phosphorylation, we used phosphosite-specific antibodies against IGFBP-1 at Ser101, Ser119 and Ser169 (Figure 1D–F). We demonstrated that while rapamycin consistently induced IGFBP-1 phosphorylation (Ser101, +400%, Ser119, +200% and Ser169, +400%), leucine deprivation caused a profound increase in IGFBP-1 phosphorylation beyond that seen by rapamycin treatment alone (Ser101, +1000%, Ser119, +500% and Ser169, +1200%) (Figure 1D–F). Further, there was no additive effect on IGFBP-1 phosphorylation at any of the three sites in combined leucine deprivation and rapamycin treatment compared to leucine deprivation alone (Figure 1D–F), suggesting that mTOR signaling does not induce IGFBP-1 phosphorylation in a parallel mechanism, but rather contributes partially to IGFBP-1 phosphorylation induced by leucine deprivation. Together, these findings strongly suggest that while leucine deprivation inhibited mTOR signaling to the same extent as rapamycin, changes in IGFBP-1 phosphorylation under nutrient deprivation are only in part regulated by mTOR signaling. While mTOR inhibition was sufficient to induce total IGFBP-1 secretion to the same extent as leucine deprivation with no additive effects, suggesting that mTOR signaling and leucine deprivation function in a common mechanism to induce total IGFBP-1 secretion, additional mechanisms are involved in regulation of IGFBP-1 phosphorylation.

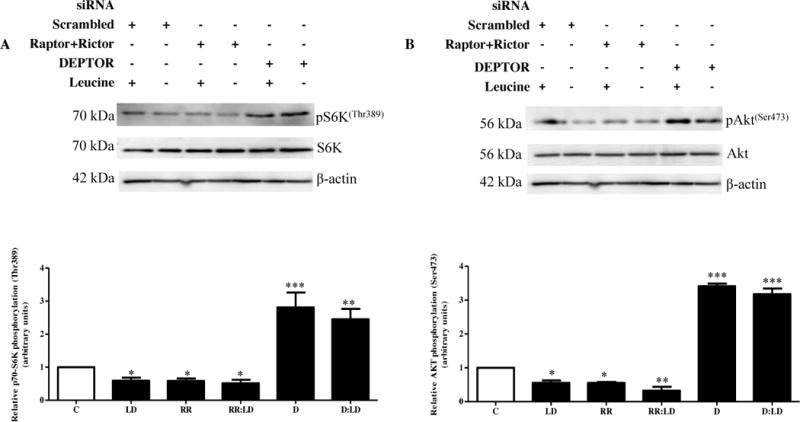

3.3 Inhibition of mTOR signaling by raptor and rictor silencing confirms that mTOR induces IGFBP-1 secretion, but not phosphorylation during leucine deprivation

For selective inhibition of mTOR complexes, we employed an RNAi strategy to silence both raptor and rictor in leucine or leucine deprived conditions with HepG2 cells. Primarily, we confirmed efficient silencing of both raptor (−45–50%) and rictor (−50%) (Figure S1A–B). Raptor+rictor silencing successfully inhibited mTORC1 activity as seen by reduced (−50%) phosphorylation of p70-S6K (Thr389) to a similar extent as leucine deprivation or combined leucine deprivation and raptor+rictor silencing (Figure 2A). Similarly, mTORC2 activity was reduced to a similar extent in leucine deprivation, raptor+rictor silencing and combined leucine deprivation and raptor+rictor silencing as assessed by a reduction in phosphorylation of Akt (−50%) at Ser473 (Figure 2B). We therefore confirmed the ability of raptor+rictor silencing to effectively inhibit mTORC1 and C2 signaling.

Figure 2. The effect of raptor+rictor or DEPTOR silencing on IGFBP-1 secretion and phosphorylation in leucine deprivation.

HepG2 cells were treated with scrambled, raptor+rictor, or DEPTOR siRNA for 24 hours and subsequently cultured in leucine plus (450 μM Leu) or leucine deprived (0 μM Leu) media for 72 hours (n=3 each).

A. A representative western immunoblot of HepG2 cell lysates (35 μg per lane) displaying S6K (Thr389) phosphorylation. Raptor+rictor silencing inhibited S6K (Thr389) phosphorylation to the same extent as leucine deprivation. DEPTOR silencing induced S6K (Thr389) phosphorylation regardless of leucine status. B. A representative western immunoblot of Akt (Ser473) phosphorylation in HepG2 cell lysates silenced with raptor+rictor or DEPTOR siRNA with or without leucine deprivation. Equal protein loading (35 μg) was conducted. Raptor+rictor inhibited Akt (Ser473) phosphorylation to a similar extent as leucine deprivation, and combined raptor+rictor and leucine deprivation did not further reduce Akt (Ser473) phosphorylation. DEPTOR silencing induced Akt (Ser473) phosphorylation regardless of leucine status. C. A representative western immunoblot of total IGFBP-1 secretion in equal amounts of cell media of scrambled, raptor+rictor, DEPTOR siRNA with and without leucine deprivation HepG2 cells. Raptor+rictor, leucine deprivation, and combined raptor+rictor and leucine deprivation all induced IGFBP-1 secretion to a similar extent. DEPTOR silencing attenuated leucine deprivation-induced IGFBP-1 secretion. D–F. Representative western immunoblots of HepG2 cell media treated with scrambled, raptor+rictor, or DEPTOR siRNA with or without leucine deprivation and assayed for IGFBP-1 phosphorylation at Ser101, Ser119 and Ser169. Raptor+rictor induced IGFBP-1 phosphorylation at all three sites, but not to the same extent as leucine deprivation. DEPTOR siRNA failed to attenuate IGFBP-1 phosphorylation at all three sites. Values are displayed as mean + SEM. *p< 0.05, **p= 0.001–0.05, ***p < 0.0001 versus control; One-way analysis of variance;; Dunnet’s Multiple Comparison Test; n=3.

Next, we sought to assess whether raptor+rictor silencing translated to changes in IGFBP-1 secretion and phosphorylation. We demonstrated that raptor+rictor silencing induced total IGFBP-1 secretion (+350%) to levels comparable to leucine deprivation with or without raptor+rictor silencing (+400%), and that combined raptor+rictor silencing and leucine deprivation had no additive effect on IGFBP-1 secretion compared to leucine deprivation alone (Figure 2C). As expected, raptor+rictor silencing induced IGFBP-1 phosphorylation at all three sites (Ser101, +400%, Ser119, +200% and Ser169, +400%) but was unable to achieve the phosphorylation induced in the presence of leucine deprivation (Ser101, +2000%, Ser119, +1100% and Ser169, +2300%) (Figure 2D–F).

3.4 Activation of mTORC1 and C2 signaling by DEPTOR silencing attenuates leucine deprivation-induced IGFBP-1 secretion but not phosphorylation

To further study changes in IGFBP-1 secretion and phosphorylation under mTOR signaling, we selectively activated the mTOR pathway using siRNA against DEPTOR, an endogenous inhibitor against mTORC1 and C2 activity. To maximize cell viability, serum free DMEM:F12 media containing transfection reagent was aspirated immediately following the 24 hour transfection period. Cell media were subsequently replaced with DMEM with (450 μM) or without (0 μM) leucine for an additional 72 hours. We first confirmed that our RNAi approach efficiently reduced (−50%) DEPTOR expression (Figure S1C). Analysis of cell lysates was used to examine changes in phosphorylation of downstream mTOR effectors (Figure 2A–B). DEPTOR silencing successfully induced p70-S6K (Thr389) phosphorylation (+250%) (Figure 2A) and Akt (Ser473) phosphorylation (+300%) (Figure 2B) regardless of leucine status, supporting that constitutive activation of the mTOR pathway induces mTORC1 and C2 signaling downstream of leucine deprivation.

We proceeded to test whether mTOR activation was able to prevent changes in IGFBP-1 secretion and phosphorylation caused by leucine deprivation. Activating mTOR signaling by DEPTOR silencing successfully attenuated leucine deprivation-induced IGFBP-1 secretion (+400%) (Figure 2C) but was unable to prevent leucine deprivation-induced phosphorylation (Ser101, +2000%, Ser119, +1000% and Ser169, +2300%) of IGFBP-1 at all three phosphosites (Figure 2D–F). Since mTORC1 and C2 inhibition induced total IGFBP-1 secretion only to the same extent as leucine deprivation, and since mTORC1 and C2 activation completely prevents this induction, we assert that mTOR signaling is the key mechanism implicated in IGFBP-1 secretion, but not phosphorylation, induced by leucine deprivation.

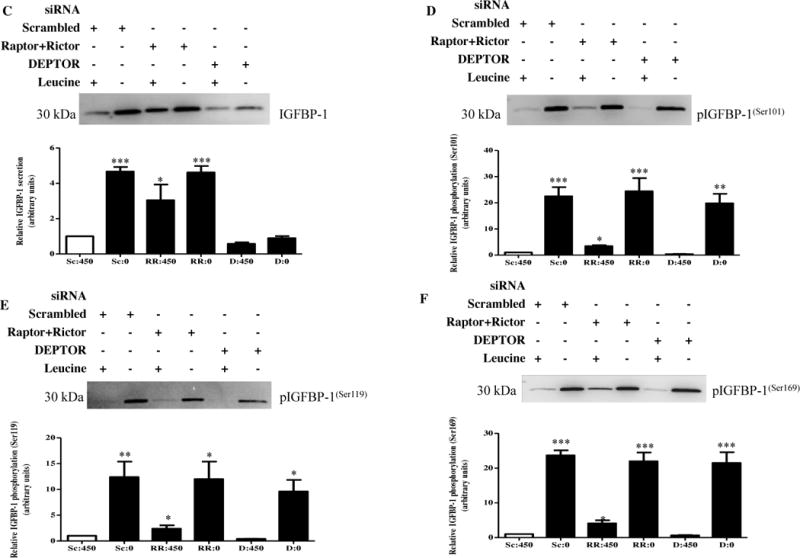

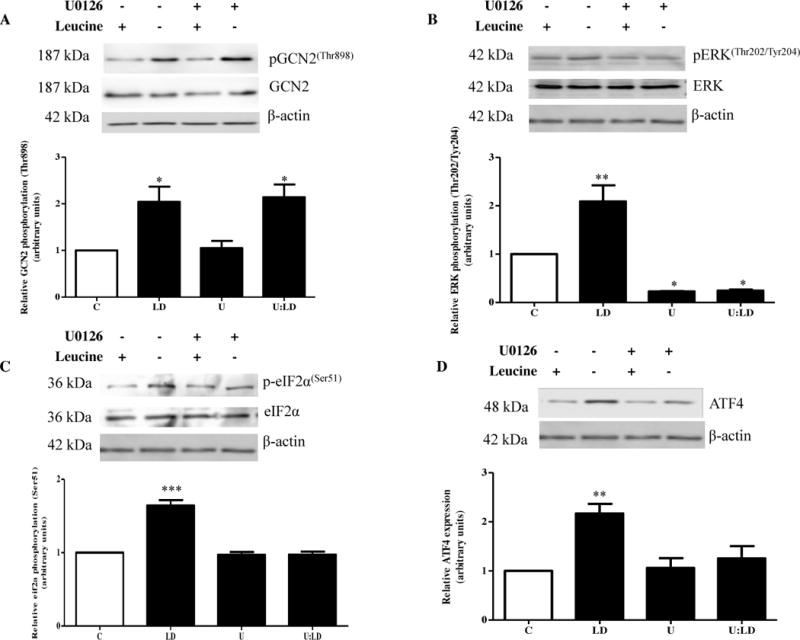

3.5 Inhibition of AAR (MEK/ERK) signaling attenuates the amino acid response triggered by leucine deprivation

To investigate stress-responsive pathways other than mTOR that may be involved in regulating IGFBP-1 phosphorylation under leucine deprivation, we inhibited AAR signaling, which is activated under cellular amino acid deprivation. To chemically inhibit AAR signaling, we used AAR (MEK1/2) inhibitor U0126 (10 μM) since MEK signaling is necessary for GCN2-mediated eiF2α phosphorylation (Ser51) and subsequent propagation of the AAR. We tested the effects of U0126 on leucine-mediated IGFBP-1 secretion and phosphorylation.

GCN2 was activated, as indicated by an increase in GCN2 (Thr898) phosphorylation, under leucine deprivation (+200%) regardless of MEK status (Figure 3A). Leucine deprivation also induced MEK activity proportionate to GCN2 as indicated by increased ERK (Thr202/Tyr204) phosphorylation (+200%), which was on the contrary decreased in the presence of U0126 (−50%) regardless of leucine status (Figure 3B).

Figure 3. Effect of pharmacological AAR inhibitor U0126 (MEK1/2) on IGFBP-1 secretion and phosphorylation.

HepG2 cells were treated with U0126 (10 μM) and cultured in leucine plus (450 μM Leu) or leucine deprived (0 μM) media for 24 hours (n=3 each).

A. Representative western immunoblot of HepG2 cell lysates (50 μg per lane) tested for GCN2 (Thr898) phosphorylation. The AAR was activated by leucine deprivation regardless of the presence of U0126. B. A representative western immunoblot of HepG2 cell lysates display induced ERK (Thr202/Tyr204) phosphorylation in leucine deprivation, and reduced ERK (Thr202/Tyr204) phosphorylation in the presence of U0126 regardless of leucine status. Equal protein was loaded in each lane (35 μg). C. A representative western immunoblot of eiF2α (Ser51) phosphorylation (35 μg total protein/lane) indicates hyperphosphorylation in leucine deprivation which was prevented in the presence of U0126, suggesting that MEK/ERK inhibition successfully attenuated the AAR response. D. Representative western immunoblot of total ATF4 expression (50 μg total protein/lane). Total ATF4 expression was increased in leucine deprivation, and remained similar to control in the presence of U0126 regardless of leucine status, supporting attenuation of the AAR pathway by U0126 in leucine deprivation. E. A representative western immunoblot indicating total IGFBP-1 secretion in HepG2 cell media in control, leucine deprivation, U0126, and leucine deprivation+U0126 treatments. Equal volumes of media were loaded. U0126 reduced total IGFBP-1 secretion regardless of leucine status and no increase in total IGFBP-1 secretion was seen in leucine deprivation when the inhibitor was present. F–H. Representative western immunoblots of HepG2 cell media from control, leucine deprivation, U0126, and leucine deprivation+U0126 treated cells. IGFBP-1 phosphorylation at Ser101, Ser119, and Ser169, which is induced in leucine deprivation, is reduced in the presence of inhibitor. No difference in phosphorylation at all three sites is seen between leucine plus or leucine deprived media in the presence of inhibitor. Values are displayed as mean + SEM. *p< 0.05, **p= 0.001–0.05, ***p < 0.0001 versus control; One-way analysis of variance; Dunnet’s Multiple Comparison Test; n=3.

Figures 3C–D indicate that leucine deprivation and subsequent GCN2 activation further stimulate the AAR as evidenced by an increase in eiF2α (Ser51) phosphorylation (+150%) and total ATF expression (+200%) in leucine deprived samples. However, AAR (MEK/ERK) inhibition with U0126 was successful in preventing leucine deprivation-induced AAR propagation downstream of GCN2. We concluded this because in the presence of the inhibitor, leucine deprivation was unable to induce eiF2α (Ser51) phosphorylation and ATF4 expression beyond control values (Figure 3C–D). Together, these data advocate the importance of MEK/ERK signaling in AAR propagation and confirm that chemical inhibition of AAR (MEK1/2) is sufficient in attenuating the AAR cascade.

3.6 AAR (MEK/ERK) inhibition prevents leucine deprivation-induced IGFBP-1 secretion and phosphorylation

We assessed whether attenuation of the AAR results in changes in downstream IGFBP-1 secretion and phosphorylation. Total IGFBP-1 secretion was induced (+200%) in leucine deprivation and reduced (−50%) in the presence of U0126, regardless of leucine status (Figure 3E). IGFBP-1 phosphorylation was profoundly induced (Ser101, +700%, Ser119, +250% and Ser169, +900%) under leucine deprivation and reduced (−50%) at all three phosphosites regardless of leucine status when AAR (MEK/ERK) was inhibited (Figure 3F–H). Importantly, there was no difference in IGFBP-1 secretion or phosphorylation between with and without leucine treatments in the presence of inhibitor (Figure 3E–H). We also further verified our data by using selective AAR (MEK1) inhibitor (PD98059, 10 μM) which produced comparable results (data not shown). To validate changes in IGFBP-1 secretion and phosphorylation, we performed the Trypan Blue exclusion assay and demonstrated no significant change in post-treatment cell viability between treatment conditions (Figure S2).

3.7 siRNA silencing of ERK (to inhibit ERK-mediated AAR) prevents leucine deprivation-induced IGFBP-1 secretion and phosphorylation

To verify that changes in IGFBP-1 secretion and phosphorylation under leucine deprivation and inhibition by U0126 were specific and that effects were targeted, in a subset of experiments, cells were treated with siRNA against ERK to attenuate ERK-mediated AAR signaling. First, we validated ERK silencing efficiency by assessing cell lysates for total ERK expression (−45%) (Figure S3). GCN2 (Thr898) phosphorylation was induced by leucine deprivation (+200%) regardless of ERK status (Figure 4A). Although leucine deprivation triggered AAR signaling, it was not stimulated downstream of GCN2 in cells where ERK was silenced as seen by a lack of induction in eiF2α (Ser51) phosphorylation and ATF4 expression, which were otherwise both triggered (+200%) in leucine deprivation (Figure 4B–C).

Figure 4. Effects of ERK siRNA on IGFBP-1 secretion and phosphorylation.

HepG2 cells were treated with scrambled or ERK siRNA for 24 hours and subsequently cultured in leucine plus (450 μM Leu) or leucine deprived (0 μM Leu) media for 72 hours (n=3 each).

A. A representative western immunoblot of HepG2 cell lysates (50 μg per lane) displaying GCN2 (Thr898) phosphorylation. Leucine deprivation induced GCN2 (Thr898) phosphorylation regardless of ERK status. B–C. Representative western immunoblots of HepG2 cell lysates treated with scrambled or ERK siRNA with or without leucine deprivation. Equal total protein was loaded in each lane (50 μg). Phosphorylation of eiF2α (Ser51) and total ATF expression were induced in leucine deprivation in HepG2 cells treated with scrambled, but not ERK, siRNA, suggesting that reduction of ERK successfully attenuated leucine deprivation-induced AAR at the point following GCN2-mediated AAR activation. D. A representative western immunoblot of total IGFBP-1 secretion in equal amounts of cell media of HepG2 cell media treated with scrambled or ERK siRNA with and without leucine deprivation. ERK inhibition attenuated leucine deprivation-induced total IGFBP-1 secretion. E–G. Representative western immunoblots of HepG2 cell media treated with scrambled or ERK siRNA with or without leucine deprivation and assayed for IGFBP-1 phosphorylation at Ser101, Ser119 and Ser169. Leucine deprivation induced IGFBP-1 phosphorylation at all three sites, and the effect was prevented when ERK was silenced. Values are displayed as mean + SEM. *p< 0.05, **p= 0.001–0.05, ***p < 0.0001 versus control; One-way analysis of variance; Dunnet’s Multiple Comparison Test; n=3.

We examined whether ERK silencing (to inhibit ERK-mediated AAR) was able to attenuate IGFBP-1 secretion and phosphorylation in HepG2 cells. IGFBP-1 secretion and phosphorylation at all three sites (Ser101, Ser119, Ser169) remained consistent with control values in the presence or absence of leucine when ERK was silenced (Figures 4D–G), supporting our finding that IGFBP-1 secretion and phosphorylation under leucine deprivation is mediated by the AAR in a MEK-ERK dependant mechanism.

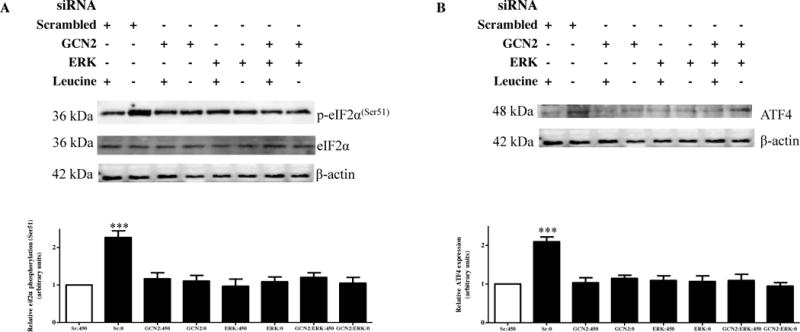

3.8 AAR inhibition via GCN2 silencing and ERK inhibition (to inhibit ERK-mediated AAR) act in a common mechanism to regulate IGFBP-1 secretion and phosphorylation in leucine deprivation

To verify that MEK/ERK inhibition-mediated regulation of IGFBP-1 secretion and phosphorylation functions in accordance with the AAR, we inhibited AAR signaling via GCN2 silencing in tandem with MEK/ERK signaling and assessed changes in downstream AAR effectors and IGFBP-1 secretion and phosphorylation. We used siRNA to knockdown GCN2 to prevent AAR-sensing, separately and together with ERK siRNA. We first confirmed GCN2 (−50%) and ERK (−50%) knockdown efficiency using cell lysates (Figure S4A–B). GCN2 and ERK silencing, separately and together, prevented AAR propagation downstream of GCN2 as seen by a lack of increase in eiF2α (Ser51) phosphorylation and ATF4 expression in leucine deprivation by cells silenced for GCN2 and/or ERK, both of which were otherwise induced (+200%) by leucine deprivation (Figure 5A–B). Silencing of either or both proteins also attenuated the induction of IGFBP-1 secretion and phosphorylation in leucine deprivation (Figure 5C–F). Interestingly, there was no additional reduction in IGFBP-1 secretion or phosphorylation in leucine plus or leucine deprived samples when both pathways were inhibited simultaneously (Figure 5A–D) suggesting that MEK/ERK signaling and the AAR function in a common mechanism to regulate both IGFBP-1 secretion and phosphorylation in leucine deprivation.

Figure 5. Effects of ERK and/or GCN2 silencing on IGFBP-1 secretion and phosphorylation.

HepG2 cells were treated with scrambled, ERK, GCN2or ERK+GCN2 siRNA for 24 hours and subsequently cultured in leucine plus (450 μM Leu) or leucine deprived (0 μM Leu) media for 72 hours (n=3 each).

A. A representative western immunoblot of HepG2 cell lysates (50 μg per lane) displaying eiF2α (Ser51) phosphorylation demonstrate induction of phosphorylation under leucine deprivation, an effect attenuated to the same extent when GCN2 and/or ERK was silenced. B. A representative western immunoblot of total ATF4 expression in HepG2 cell lysates silenced with GCN2 and/or ERK siRNA with or without leucine deprivation. Equal protein loading (50 μg) was performed. ATF4 expression was increased in leucine deprivation, an effect prevented by silencing of either complex singly or combined. C. A representative western immunoblot of total IGFBP-1 secretion in equal amounts of cell media of HepG2 cells treated with scrambled, ERK, GCN2, or combined ERK+GCN2 siRNA with and without leucine deprivation. Leucine deprivation-mediated IGFBP-1 secretion was attenuated in HepG2cells treated silenced for GCN2 and ERK separately and together. Silencing of both compounds had no subtractive effect on total IGFBP-1 secretion. D–F. Representative western immunoblots of HepG2 cell media treated with scrambled, ERK, GCN2, or ERK+GCN2 siRNA with or without leucine deprivation and assayed for IGFBP-1 phosphorylation at Ser101, Ser119 and Ser169. GCN2 and ERK silencing inhibited leucine deprivation-induced IGFBP-1 phosphorylation at all three sites, with no additional effects when the two siRNAs were combined. Values are displayed as mean + SEM. *p< 0.05, **p= 0.001–0.05, ***p < 0.0001 versus control; One-way analysis of variance; Dunnet’s Multiple Comparison Test; n=3.

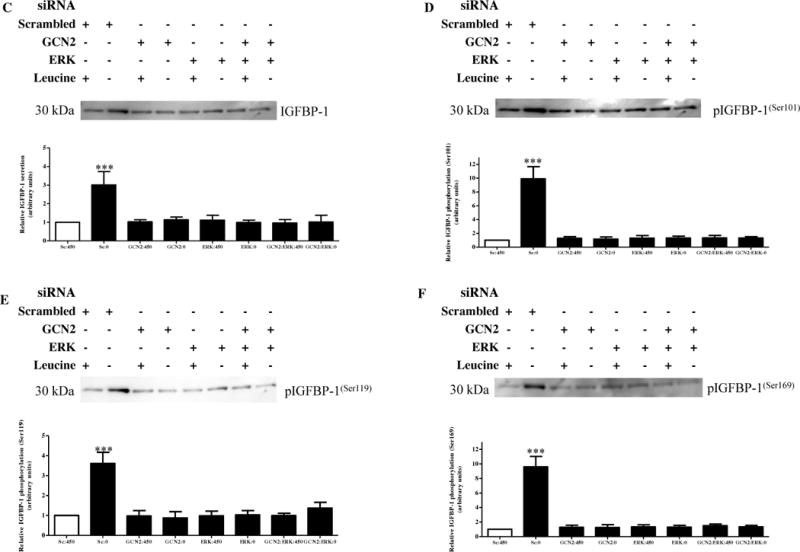

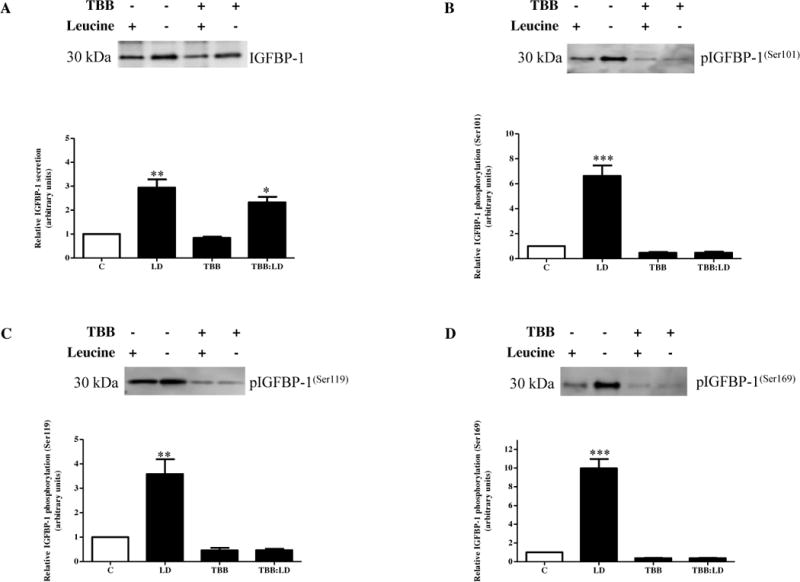

3.9 IGFBP-1 phosphorylation induced by leucine deprivation is mediated by CK2

We have hereby established that the AAR is responsible for mediating total IGFBP-1 secretion as well as IGFBP-1 phosphorylation in leucine deprivation, and that mTOR signaling partially regulates IGFBP-1 phosphorylation but is the key mechanistic link between nutrient deprivation and total IGFBP-1 secretion. Based on previous data from our lab that CK2 mediates mTOR-induced IGFBP-1 phosphorylation, we investigated whether CK2 is also involved in leucine deprivation-mediated IGFBP-1 phosphorylation. We inhibited CK2 signaling using CK2 inhibitor TBB (1 μM) in leucine plus or leucine deprived media. Following treatments, evaluation of HepG2 cells indicated intact cellular morphology, and Trypan Blue exclusion assay demonstrated that TBB treatments did not significantly alter the vitality of HepG2 cells (Figure S5), supporting that normal cell physiology was intact post-treatment.

Leucine deprivation significantly induced total IGFBP-1 secretion (+250–300%) regardless of whether they were treated with TBB, suggesting that CK2 is not involved in regulating total IGFBP-1 secretion during leucine deprivation (Figure 6A). However, similar to MEK/ERK- dependent AAR inhibition, TBB prevented the phosphorylation of IGFBP-1 at all three phosphosites as seen by an overall reduction of IGFBP-1 phosphorylation at all three sites (−60%) in TBB-treated cells and no significant increase in phosphorylation in leucine deprived versus leucine plus samples when both are treated with TBB (Figure 6B–D). Therefore, since inhibition of CK2 activity attenuated leucine deprivation-induced IGFBP-1 phosphorylation without affecting total IGFBP-1 secretion, we assert that CK2 may potentially be the major kinase responsible for IGFBP-1 phosphorylation under conditions of leucine deprivation.

Figure 6. The effect of CK2 inhibition on IGFBP-1 secretion and phosphorylation.

A. A representative blot of equal volumes of HepG2 cell media treated with leucine plus (control), leucine deprivation, TBB (1 μM), or leucine deprivation+TBB. TBB did not inhibit leucine deprivation-induced total IGFBP-1 secretion. B–D. Representative western immunoblots of equal volumes of HepG2 cell media assessed for IGFBP-1 phosphorylation at Ser101, Ser119, and Ser169. Leucine deprivation was unable to induce IGFBP-1 phosphorylation in TBB-treated cells at all three phosphosites. Values are displayed as mean + SEM. *p< 0.05, **p= 0.001–0.05, ***p < 0.0001 versus control; One-way analysis of variance; Dunnet’s Multiple Comparison Test; n=3.

3.10 Increases in IGFBP-1 phosphorylation due to leucine deprivation inhibit IGF-I bioactivity

To assess whether changes in IGFBP-1 phosphorylation under leucine deprivation effectively regulate IGF-I bioactivity, we employed an IGF-I receptor (IGF-1Rβ) autophosphorylation assay in P6 cells to test for IGF-IR (Tyr1135) autophosphorylation, an indicator of IGF-I bioactivity and cell growth and proliferation, during leucine deprivation. When P6 cells were incubated with 25 ng/mL IGF-I only (positive control), we observed a profound increase in IGF-IR (Tyr1135) phosphorylation (+2500%) compared to P6 cells without IGF-I (negative control) (Figure 7), demonstrating the ability of IGF-I to stimulate IGF-1R autophosphorylation in P6 cells. P6 cells were also treated with IGF-I plus post-treatment HepG2 cell media (leucine plus or leucine deprivation). The amount of leucine plus or leucine deprivation media used in the treatment was adjusted for total IGFBP-1 to ensure changes in IGF-IR phosphorylation were due to differences in free circulating IGF-I varied by levels of IGFBP-1 phosphorylation rather than total circulating IGFBP-1.

Figure 7. The effect of leucine deprivation-induced IGFBP-1 phosphorylation on IGF-RI autophosphorylation.

HepG2 cells were treated in leucine plus (450 μM Leu) or leucine deprived (0 μM Leu) for 24 hours (n=3). Equal concentrations of IGFBP-1 in HepG2 cell media were mixed with P6 media (serum free) and human recombinant IGF-I (25 ng/mL) for 2 hours to allow IGFBP-1 to sequester IGF-I. Ten minute exposure toP6 cells allowed the induction of IGF-I-mediated IGF-1Rβ autophosphorylation (Tyr1135).

A representative western immunoblot of whole-cell lysates (50 μg) from P6 cells overexpressing IGF-IR. Blots were assessed for IGF-IR autophosphorylation (Tyr1135). Increased IGFBP-1 phosphorylation due to leucine deprivation resulted in significantly decreased IGF-1R activation. Values are displayed as mean + SEM. *p< 0.05, **p= 0.001–0.05, ***p < 0.0001 versus control; One-way analysis of variance; Dunnet’s Multiple Comparison Test; n=3.

Basal IGFBP-1 levels (leucine plus media) reduced IGF-IR autophosphorylation (−40%), and IGF-I induction of IGF-IR phosphorylation was almost completely abolished (−90%) in the presence of leucine deprivation media due to the presence highly phosphorylated IGFBP-1species in these conditioned mediums (Figure 7). These data provide strong evidence that the hyperphosphorylation of IGFBP-1 in leucine deprivation effectively inhibits IGF-I bioactivity through reduced IGF-IR autophosphorylation.

4. Discussion

In this study, we use HepG2 cells, a model of fetal hepatocytes, to show for the first time that the AAR regulates IGFBP-1 secretion and phosphorylation in amino acid deprivation. Although mTOR inhibition induced IGFBP-1 secretion in leucine deprivation, it failed to increase IGFBP-1 phosphorylation to the levels caused by leucine deprivation alone. Activation of mTOR validated these findings, suggesting that mTOR regulates IGFBP-1 secretion but not IGFBP-1 phosphorylation in leucine deprivation. However, when the AAR was blocked, it prevented both IGFBP-1 secretion and phosphorylation in response to leucine deprivation. These findings are compatible with the hypothesis that mTOR inhibition and AAR activation increase IGFBP-1 secretion and phosphorylation independently in response to amino acid deprivation. This study provides a novel understanding of the mechanisms modulating IGF-I bioavailability and potentially fetal growth under nutrient restricted conditions.

Hypoxia and nutrient deprivation are leading causes of FGR1,11, a perinatal disorder leading to severe childhood and adult metabolic and neurological complications. IGF-I is the key regulator of fetal growth beginning at ~20-weeks gestation34 and its altered circulating levels during gestation are correlated with severe fetal growth complications35–37. IGF-I bioavailability is strongly influenced by the phosphorylation status of IGFBP-1, with hyperphosphorylation increasing the binding affinity for IGF-I and consequently resulting in its decreased bioactivity in FGR31. We have previously demonstrated that hypoxia and leucine deprivation lead to hyperphosphorylation of IGFBP-1 in vitro12. Previous literature reports and our recent studies indicate that FGR is associated with marked IGFBP-1 hyperphosphorylation in the circulation and in the liver15,38, the primary source of IGFBP-1 in the fetus, which is consistent with the possibility that increased phosphorylation of IGFBP-1 plays an important role in the development of FGR. However, the molecular mechanisms regulating hepatic IGFBP-1 secretion and phosphorylation in hypoxia and leucine deprivation are largely unknown.

FGR is characterized by decreased amino acid availability, which is known to activate the AAR39,40 and inhibit the mTOR signaling pathway22,41. We therefore investigated these two regulatory pathways, linking reduced nutrient availability to IGFBP-1 secretion and phosphorylation and consequently, reduced IGF-I bioavailability and downstream IGF-I mitogenic actions.

To test our hypothesis, we employed widely used HepG2 cells as an in vitro model, as they are sensitive to hypoxia and leucine deprivation and exhibit many characteristics of fetal hepatocytes: they synthesize α-fetoprotein at a high rate and predominantly express several fetal enzymes, isozymes and IGF and mTOR system proteins42–44. Furthermore, in our previous study, we had confirmed that the mTOR-mediated IGFBP-1 phosphorylation studied in HepG2 cells was consistent with fetal baboon liver/primary hepatocytes17, contributing to physiological relevancy of our findings.

The mTOR pathway modulates cell growth and function in response to changes in the levels of growth factors, such as IGF-I and nutrients, and is down-regulated under reduced cellular energy states19,21,23,41. Our results with pharmacological inhibitor (rapamycin) and RNAi based inhibition of mTORC1 and C2 signaling have previously demonstrated induced IGFBP-1 secretion and phosphorylation in HepG2 cells17. In the present study, we extended these studies and our new findings demonstrated that while mTOR signaling plays a vital role in regulating IGFBP-1 secretion, interestingly, leucine deprivation impinges on additional mechanisms to produce its downstream stress response on IGFBP-1 secretion and phosphorylation.

Leucine deprivation significantly induces IGFBP-1 mRNA expression to ranges observed in protein-restricted animals45 and is consistently reduced in humans with malnutrition46,47. It has also been reported that leucine deprivation is sufficient in inducing maximal IGFBP-1 mRNA expression compared to the individual or combined restriction of any other essential amino acid48. It is well established that the AAR signal transduction pathway is activated by limitation or imbalance of essential amino acids. It has also been previously shown that deprivation of a single essential amino acid leucine is sufficient to induce AAR activation via GCN2 phosphorylation49. The role of AAR in regulation of IGFBP-1 phosphorylation has however not previously been reported in any tissue.

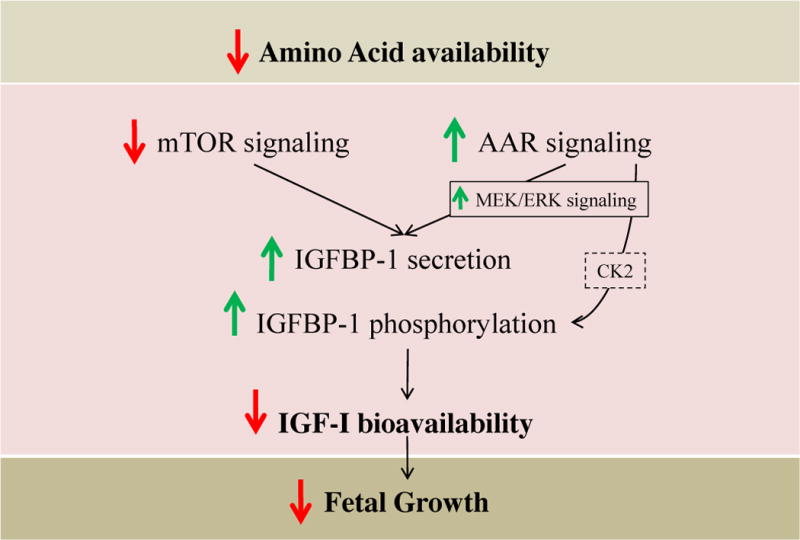

In concordance with literature reports49, we showed that leucine deprivation activated the AAR, as expected, and that this effect was attenuated downstream of GCN2 when MEK/ERK was inhibited. Attenuating the AAR via MEK/ERK and/or GCN2 inhibition/silencing clearly prevented induction of IGFBP-1 secretion and phosphorylation due to leucine deprivation; this importantly shows that the mitogenic MEK/ERK cascade mediates leucine deprivation-induced IGFBP-1 secretion and phosphorylation via its interactions with the AAR pathway. This crosstalk is vital in transducing the AAR and elucidating downstream changes in IGFBP-1 secretion and phosphorylation, suggesting that MEK/ERK-dependant AAR signaling is the key mechanism involved in fetal hepatic IGF-I regulation. Since inhibition of the AAR was sufficient to attenuate this response, we assert that IGFBP-1 secretion and phosphorylation is regulated primarily by the AAR in a MEK-dependant manner while mTOR contributes a significant role in regulation of IGFBP-1 secretion. It is unclear whether the AAR and mTOR signaling function in common or parallel mechanisms to regulate IGF-I bioavailability. In light of our findings, we propose a model where amino acid deficiency inhibits hepatic mTOR signaling while simultaneously inducing the AAR pathway, leading to an increase in IGFBP- phosphorylation and decreased fetal cell growth and proliferation (Figure 8).

Figure 8. Proposed model of fetal growth regulation in FGR.

Amino acid limitation causes a decrease in mTOR signaling which leads primarily to an increase in IGFBP-1 secretion. A concurrent induction in the AAR pathway signals an increase in IGFBP-1 secretion and phosphorylation, potentially through CK2, to regulate IGF-I bioavailability and decreased downstream fetal growth.

Although increased total IGFBP-1secretion is a strong indicator of reduced IGF-I bioavailability, we assert that the pathogenesis of FGR is due primarily to site-specific changes in IGFBP-1 phosphorylation, supported by our earlier data that show increases (30–300-fold) in IGF-1 affinity to be linked with marked increase in specific phospho-IGFBP-1 isoforms (Ser101, Ser119, Ser169)30. The three phosphorylated serine residues in IGFBP-1 conform to a general CK2 recognition motif50. CK2 modulates IGF-I activity by hyperphosphorylation of IGFBP-1 in HepG2 cells51. Furthermore, we have demonstrated that CK2 is a mechanistic link between mTOR inhibition and IGFBP-1 phosphorylation in fetal liver17. Consistent with our previous study, here we demonstrated that CK2 plays a key role in IGFBP-1 phosphorylation under leucine deprivation. CK2 intervenes laterally, impinging on many signaling pathways at different levels51. Our results implicate CK2 as a possible link between nutrient deficiency and increased IGFBP-1 phosphorylation in the AAR signaling pathway.

In conclusion, to best of our knowledge, this is the first report that investigated AAR as a key mechanism in the regulation of IGFBP-1 phosphorylation under leucine deprivation. Our results demonstrate that mTOR signaling modulates IGFBP-1 secretion and support a new role for the AAR in IGFBP-1 secretion and phosphorylation to decrease in IGF-I bioavailability under nutrient deprivation. We speculate that limited amino acid availability contributes to FGR by increasing IGFBP-1 secretion and phosphorylation via mTOR inhibition and AAR activation in the fetal liver.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the National Institute of Health (HD 078313 to MBG and TJ) and the Lawson Health Research Institute (to MBG). NM received the Department of Pediatrics (UWO) Graduate Student Scholarship.

References

- 1.Maulik D. Fetal growth restriction: The etiology. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2006;49(2):228–235. doi: 10.1097/00003081-200606000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pallotto EK, Kilbride HW. Perinatal outcome and later implications of intrauterine growth restriction. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2006;49(2):257–269. doi: 10.1097/00003081-200606000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Leger J, Oury JF, Noel M, et al. Growth factors and intrauterine growth retardation. I. serum growth hormone, insulin-like growth factor (IGF)-I, IGF-II, and IGF binding protein 3 levels in normally grown and growth-retarded human fetuses during the second half of gestation. Pediatr Res. 1996;40(1):94–100. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199607000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clemmons DR, Busby WH, Arai T, et al. Role of insulin-like growth factor binding proteins in the control of IGF actions. Prog Growth Factor Res. 1995;6(2–4):357–366. doi: 10.1016/0955-2235(95)00013-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Han VK, Matsell DG, Delhanty PJ, Hill DJ, Shimasaki S, Nygard K. IGF-binding protein mRNAs in the human fetus: Tissue and cellular distribution of developmental expression. Horm Res. 1996;45(3–5):160–166. doi: 10.1159/000184780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gibson JM, Westwood M, Lauszus FF, Klebe JG, Flyvbjerg A, White A. Phosphorylated insulin-like growth factor binding protein 1 is increased in pregnant diabetic subjects. Diabetes. 1999;48(2):321–326. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.48.2.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jones JI, D’Ercole AJ, Camacho-Hubner C, Clemmons DR. Phosphorylation of insulin-like growth factor (IGF)-binding protein 1 in cell culture and in vivo: Effects on affinity for IGF-I. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991;88(17):7481–7485. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.17.7481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Frost RA, Tseng L. Insulin-like growth factor-binding protein-1 is phosphorylated by cultured human endometrial stromal cells and multiple protein kinases in vitro. J Biol Chem. 1991;266(27):18082–18088. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yu J, Iwashita M, Kudo Y, Takeda Y. Phosphorylated insulin-like growth factor (IGF)-binding protein-1 (IGFBP-1) inhibits while non-phosphorylated IGFBP-1 stimulates IGF-I- induced amino acid uptake by cultured trophoblast cells. Growth Horm IGF Res. 1998;8(1):65–70. doi: 10.1016/s1096-6374(98)80323-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Frost RA, Bereket A, Wilson TA, Wojnar MM, Lang CH, Gelato MC. Phosphorylation of insulin-like growth factor binding protein-1 in patients with insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus and severe trauma. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1994;78(6):1533–1535. doi: 10.1210/jcem.78.6.7515391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miller J, Turan S, Baschat AA. Fetal growth restriction. Semin Perinatol. 2008;32(4):274–280. doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2008.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Seferovic MD, Ali R, Kamei H, et al. Hypoxia and leucine deprivation induce human insulin-like growth factor binding protein-1 hyperphosphorylation and increase its biological activity. Endocrinology. 2009;150(1):220–231. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-0657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee PD, Conover CA, Powell DR. Regulation and function of insulin-like growth factor-binding protein-1. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1993;204(1):4–29. doi: 10.3181/00379727-204-43630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Watson CS, Bialek P, Anzo M, Khosravi J, Yee SP, Han VK. Elevated circulating insulin-like growth factor binding protein-1 is sufficient to cause fetal growth restriction. Endocrinology. 2006;147(3):1175–1186. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-0606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Larsson A, Palm M, Basu S, Axelsson O. Insulin-like growth factor binding protein-1 (IGFBP-1) during normal pregnancy. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2013;29(2):129–132. doi: 10.3109/09513590.2012.730574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reece EA, Wiznitzer A, Le E, Homko CJ, Behrman H, Spencer EM. The relation between human fetal growth and fetal blood levels of insulin-like growth factors I and II, their binding proteins, and receptors. Obstet Gynecol. 1994;84(1):88–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Abu Shehab M, Damerill I, Shen T, et al. Liver mTOR controls IGF-I bioavailability by regulation of protein kinase CK2 and IGFBP-1 phosphorylation in fetal growth restriction. Endocrinology. 2014;155(4):1327–1339. doi: 10.1210/en.2013-1759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Strakovsky RS, Zhou D, Pan YX. A low-protein diet during gestation in rats activates the placental mammalian amino acid response pathway and programs the growth capacity of offspring. J Nutr. 2010;140(12):2116–2120. doi: 10.3945/jn.110.127803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Roos S, Powell TL, Jansson T. Placental mTOR links maternal nutrient availability to fetal growth. Biochem Soc Trans. 2009;37(Pt 1):295–298. doi: 10.1042/BST0370295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang X, Proud CG. mTORC1 signaling: What we still don’t know. J Mol Cell Biol. 2011;3(4):206–220. doi: 10.1093/jmcb/mjq038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Foster KG, Fingar DC. Mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR): Conducting the cellular signaling symphony. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(19):14071–14077. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R109.094003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li F, Yin Y, Tan B, Kong X, Wu G. Leucine nutrition in animals and humans: MTOR signaling and beyond. Amino Acids. 2011;41(5):1185–1193. doi: 10.1007/s00726-011-0983-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chotechuang N, Azzout-Marniche D, Bos C, et al. mTOR, AMPK, and GCN2 coordinate the adaptation of hepatic energy metabolic pathways in response to protein intake in the rat. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2009;297(6):E1313–23. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.91000.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kilberg MS, Pan YX, Chen H, Leung-Pineda V. Nutritional control of gene expression: How mammalian cells respond to amino acid limitation. Annu Rev Nutr. 2005;25:59–85. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.24.012003.132145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhou D, Pan YX. Gestational low protein diet selectively induces the amino acid response pathway target genes in the liver of offspring rats through transcription factor binding and histone modifications. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1809(10):549–556. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2011.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thiaville MM, Dudenhausen EE, Zhong C, Pan YX, Kilberg MS. Deprivation of protein or amino acid induces C/EBPbeta synthesis and binding to amino acid response elements, but its action is not an absolute requirement for enhanced transcription. Biochem J. 2008;410(3):473–484. doi: 10.1042/BJ20071252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hinnebusch AG. Translational regulation of yeast GCN4. A window on factors that control initiator-trna binding to the ribosome. J Biol Chem. 1997;272(35):21661–21664. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.35.21661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dong J, Qiu H, Garcia-Barrio M, Anderson J, Hinnebusch AG. Uncharged tRNA activates GCN2 by displacing the protein kinase moiety from a bipartite tRNA-binding domain. Mol Cell. 2000;6(2):269–279. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)00028-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Deng J, Harding HP, Raught B, et al. Activation of GCN2 in UV-irradiated cells inhibits translation. Curr Biol. 2002;12(15):1279–1286. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)01037-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Abu Shehab M, Iosef C, Wildgruber R, Sardana G, Gupta MB. Phosphorylation of IGFBP-1 at discrete sites elicits variable effects on IGF-I receptor autophosphorylation. Endocrinology. 2013;154(3):1130–1143. doi: 10.1210/en.2012-1962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Abu Shehab M, Khosravi J, Han VK, Shilton BH, Gupta MB. Site-specific IGFBP-1 hyperphosphorylation in fetal growth restriction: Clinical and functional relevance. J Proteome Res. 2010;9(4):1873–1881. doi: 10.1021/pr900987n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Abu Shehab M, Inoue S, Han VK, Gupta MB. Site specific phosphorylation of insulin-like growth factor binding protein-1 (IGFBP-1) for evaluating clinical relevancy in fetal growth restriction. J Proteome Res. 2009;8(11):5325–5335. doi: 10.1021/pr900633x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Valentinis B, Baserga R. IGF-I receptor signalling in transformation and differentiation. Mol Pathol. 2001;54(3):133–137. doi: 10.1136/mp.54.3.133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chellakooty M, Vangsgaard K, Larsen T, et al. A longitudinal study of intrauterine growth and the placental growth hormone (GH)-insulin-like growth factor I axis in maternal circulation: Association between placental GH and fetal growth. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89(1):384–391. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-030282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sifakis S, Akolekar R, Kappou D, Mantas N, Nicolaides KH. Maternal serum insulin-like growth factor (IGF-I) and binding proteins IGFBP-1 and IGFBP-3 at 11–13 weeks’ gestation in pregnancies delivering small for gestational age neonates. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2012;161(1):30–33. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2011.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McIntyre HD, Serek R, Crane DI, et al. Placental growth hormone (GH), GH-binding protein, and insulin-like growth factor axis in normal, growth-retarded, and diabetic pregnancies: Correlations with fetal growth. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2000;85(3):1143–1150. doi: 10.1210/jcem.85.3.6480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hayati AR, Cheah FC, Yong JF, Tan AE, Norizah WM. The role of serum insulin-like growth factor I (IGF-I) in neonatal outcome. J Clin Pathol. 2004;57(12):1299–1301. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2004.017566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Iwashita M, Sakai K, Kudo Y, Takeda Y. Phosphoisoforms of insulin-like growth factor binding protein-1 in appropriate-for-gestational-age and small-for-gestational-age fetuses. Growth Horm IGF Res. 1998;8(6):487–493. doi: 10.1016/s1096-6374(98)80302-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Neerhof MG, Thaete LG. The fetal response to chronic placental insufficiency. Semin Perinatol. 2008;32(3):201–205. doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2007.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Regnault TR, de Vrijer B, Galan HL, Wilkening RB, Battaglia FC, Meschia G. Umbilical uptakes and transplacental concentration ratios of amino acids in severe fetal growth restriction. Pediatr Res. 2013;73(5):602–611. doi: 10.1038/pr.2013.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Roos S, Jansson N, Palmberg I, Saljo K, Powell TL, Jansson T. Mammalian target of rapamycin in the human placenta regulates leucine transport and is down-regulated in restricted fetal growth. J Physiol. 2007;582(Pt 1):449–459. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.129676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kelly JH, Darlington GJ. Modulation of the liver specific phenotype in the human hepatoblastoma line hep G2. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol. 1989;25(2):217–222. doi: 10.1007/BF02626182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wilkening S, Stahl F, Bader A. Comparison of primary human hepatocytes and hepatoma cell line Hepg2 with regard to their biotransformation properties. Drug Metab Dispos. 2003;31(8):1035–1042. doi: 10.1124/dmd.31.8.1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Maruyama M, Matsunaga T, Harada E, Ohmori S. Comparison of basal gene expression and induction of CYP3As in HepG2 and human fetal liver cells. Biol Pharm Bull. 2007;30(11):2091–2097. doi: 10.1248/bpb.30.2091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Straus DS, Burke EJ, Marten NW. Induction of insulin-like growth factor binding protein-1 gene expression in liver of protein-restricted rats and in rat hepatoma cells limited for a single amino acid. Endocrinology. 1993;132(3):1090–1100. doi: 10.1210/endo.132.3.7679969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Grimble RF, Whitehead RG. Fasting serum-aminoacid patterns in kwashiorkor and after administration of different levels of protein. Lancet. 1970;1(7653):918–920. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(70)91047-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Baertl JM, Placko RP, Graham GG. Serum proteins and plasma free amino acids in severe malnutrition. Am J Clin Nutr. 1974;27(7):733–742. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/27.7.733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jousse C, Bruhat A, Ferrara M, Fafournoux P. Physiological concentration of amino acids regulates insulin-like-growth-factor-binding protein 1 expression. Biochem J. 1998;334(Pt 1):147–153. doi: 10.1042/bj3340147. (Pt 1) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Thiaville MM, Pan YX, Gjymishka A, Zhong C, Kaufman RJ, Kilberg MS. MEK signaling is required for phosphorylation of eIF2alpha following amino acid limitation of HepG2 human hepatoma cells. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(16):10848–10857. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M708320200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Litchfield DW. Protein kinase CK2: Structure, regulation and role in cellular decisions of life and death. Biochem J. 2003;369(Pt 1):1–15. doi: 10.1042/BJ20021469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ankrapp DP, Jones JI, Clemmons DR. Characterization of insulin-like growth factor binding protein-1 kinases from human hepatoma cells. J Cell Biochem. 1996;60(3):387–399. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4644(19960301)60:3<387::aid-jcb10>3.0.co;2-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.