Abstract

Background

A growing body of evidence suggests that healthcare practitioners who enhance how they express empathy can improve patient health, and reduce medico-legal risk. However we do not know how consistently healthcare practitioners express adequate empathy. In this study, we addressed this gap by investigating patient rankings of practitioner empathy.

Methods

We conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of studies that asked patients to rate their practitioners’ empathy using the Consultation and Relational Empathy (CARE) measure. CARE is emerging as the most common and best-validated patient rating of practitioner empathy. We searched: MEDLINE, Embase, PsycINFO, Cinahl, Science & Social Science Citation Indexes, the Cochrane Library and PubMed from database inception to March 2016. We excluded studies that did not use the CARE measure. Two reviewers independently screened titles and extracted data on average CARE scores, demographic data for patients and practitioners, and type of healthcare practitioners.

Results

Sixty-four independent studies within 51 publications had sufficient data to pool. The average CARE score was 40.48 (95% CI, 39.24 to 41.72). This rank s in the bottom 5th percentile in comparison with scores collected by CARE developers. Longer consultations (n = 13) scored 15% higher (42.60, 95% CI 40.66 to 44.54) than shorter (n = 9) consultations (34.93, 95% CI 32.63 to 37.24). Studies with mostly (>50%) female practitioners (n = 6) showed 16% higher empathy scores (42.77, 95% CI 38.98 to 46.56) than those with mostly (>50%) male (n = 6) practitioners (34.84, 95% CI 30.98 to 38.71). There were statistically significant (P = 0.032) differences between types of providers (allied health professionals, medical students, physicians, and traditional Chinese doctors). Allied Health Professionals (n = 6) scored the highest (45.29, 95% CI 41.38 to 49.20), and physicians (n = 39) scored the lowest (39.68, 95% CI 38.29 to 41.08). Patients in Australia, the USA, and the UK reported highest empathy ratings (>43 average CARE), with lowest scores (<35 average CARE scores) in Hong Kong.

Conclusions

Patient rankings of practitioner empathy are highly variable, with female practitioners expressing empathy to patients more effectively than male practitioners. The high variability of patient rating of practitioner empathy is likely to be associated with variable patient health outcomes. Limitations included frequent failure to report response rates introducing a risk of response bias. Future work is warranted to investigate ways to reduce the variability in practitioner empathy.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s12909-017-0967-3) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Empathy, Consultation, Communication, Practitioner, Expectations

Background

A growing number of randomized trials show that when healthcare practitioners are encouraged to enhance how they express empathy, this can reduce patient pain, [1, 2] lower patient anxiety, [3] increase patient satisfaction, [4, 5] improve medication adherence, [6, 7] and ameliorate other patient health outcomes. [8–11]. For example, Chassany’s [1] empathy training intervention for general practitioners (GPs) (n = 180) reduced pain in osteoarthritis patients (n = 842) by one point on a 10-point VAS (P < 0.0001). These modest benefits are comparable to many pharmaceutical interventions without the adverse events. Hence some authors have recently called for efforts to encourage empathic care [12].

Supporting the view that empathic care should be encouraged, the extent to which healthcare practitioners express empathy seems to be lacking in some cases, [13–16] and it may decline with time in practice [17]. The increased burden of paperwork, which takes up a quarter of practitioner time, [18] may be a barrier to empathic care. However we do not know the prevalence of inadequate empathy. If adequate empathy is rare, then patients and practitioners would both likely benefit if practitioners reinforced how they display empathy. In this study, we aimed to address this gap by conducting a systematic review of patient ratings of practitioner empathy.

An obstacle to empathy research is that practitioner empathy is difficult to define theoretically [19, 20]. At the same time there is an emerging consensus that empathy can be operationalized as a healthcare practitioner’s ability to understand a patient’s point of view, express this understanding, and make a recommendation that reflects the shared understanding [21, 22]. More importantly for present purposes, while empathy is measured using different scales, [23, 24] only one patient-rating of practitioner empathy demonstrated evidence of reliability, [25] internal validity and consistency: CARE [25, 26]. From a patient health perspective, patient ratings of practitioner empathy are likely to be important. We therefore limited our review to studies that used the CARE measure.

Objectives

Our primary objective was to measure the extent to which patients (of any type) report their healthcare practitioners (of any type) to be empathic. Our secondary objective was to compare differences in empathy ratings between different practitioner groups (male versus female, consultation times, different types of practitioners, and practitioners in different countries).

Methods

Protocol and registration

The protocol for this review was published in PROSPERO (record no. CRD42016037456). We made two changes to the protocol. In the protocol we proposed to analyze CARE scores before and after training, however there were insufficient studies to complete this analysis. We also had insufficient data to perform the proposed analyses comparing practitioners with 10 years or more experience with those who had less than 10 years experience. Neither of these changes was related to our main study aim.

Eligibility criteria

We included any study where patients rated their practitioners’ empathy using the CARE measure. We included ratings of any practitioner including nurses, doctors, alternative practitioners, and medical students. We included studies in any language, provided that the translation of the CARE questionnaire was validated.

We excluded studies that used other measures of empathy, because only CARE has been validated. An added benefit of this approach is that it reduced heterogeneity. We excluded studies where practitioners were reported to have been trained in empathy prior to being rated by patients, since we were interested in pre-training empathy ratings. Where the publications included surveys of more than one group of practitioners the surveys were treated independently.

CARE asks patients to answer 10 questions about the consultation with their practitioner such as whether the practitioner: made the patient feel at ease, really listened and understood, showed compassion, and explained things clearly (see Additional file 1). Each question can be answered by ticking one of five options: poor, fair, good, very good, excellent, does not apply, with the lowest being given a score of ‘1’, and the highest a score of ‘5’. Hence, the maximum CARE score is 50. The developers of the CARE measure have produced normative values based on administration of their questionnaire [27]. They found that the mean CARE score was 45.75, and that 5% of CARE scores fell above 48.32, and 5% fell below 40.72.

Information sources and search

We searched the following databases: MEDLINE (OvidSP) [1946–09/03/2016], Embase (OvidSP) [1974 to 2016 March 08], PsycINFO (OvidSP) [1967–09/03/2016], Cinahl (EBSCOHost), Science & Social Science Indexes (Web of Science, Thomson Reuters) [1945–09/03/2016], Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials [Issue 2 of 12, February 2016], Cochrance Database of Systematic Reviews [Issue 3 of 12, March 2016] and Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects [issue 2 of 4, April 2015] (via Cochrane Library, Wiley) and Pubmed (see Additional file 2 for search strategy). We also searched the Web of Science Core Collection, Scopus and Google Scholar for studies that have cited the CARE measure, [25] and any record that includes the full name of the measure (consultation and relational empathy). Additionally, we contacted authors of studies to ask whether they are aware of any additional studies.

Data collection, extraction, and management

After piloting the extraction sheet by two authors (JH, KM), two authors (LS, AU) independently screened all titles and abstracts and extracted data. Discrepancies were resolved with discussion by a third author (JH). We extracted data about: type of practitioner, percentage female practitioners, country, average CARE score, and individual CARE scores (where available).

We assessed risk of bias within studies by measuring response rates. It was not feasible to assess risk of bias across studies, for example by conducting a funnel plot since there was no reason to suspect higher (or lower) CARE scores varying with sample size. There was insufficient data to investigate risk of bias across studies.

Statistical analyses were performed using the program Comprehensive Meta Analysis [28]. We provided the mean and 95% confidence interval of the CARE score. We contacted study authors via email to obtain missing data with respect to participants, outcomes, or summary data. Participant data were analysed as reported. We conducted preplanned subgroup analyses to assess the extent to which proportion of female practitioners, consultation duration, type of practitioner, and country played a role. To evaluate the predictive value of gender and consultation time with respect to CARE scores we performed a multivariable regression analysis, with gender and consultation time included as the independent variables, and CARE scores included as the dependent variable.

Sensitivity and subgroup analyses

We conducted four preplanned subgroup analyses.

Longer (>10 min) consultations compared with shorter (≤ 10 min) consultations. This was based on average consultation times in UK general practice [29].

Gender: average empathy ratings of mostly (>50%) female compared with average ratings of mostly (>50%) male practitioners.

When there were at least three studies within the same country, we conducted a subgroup analysis with those three countries, and compared it with the complement. We chose three studies because fewer than three makes meta-analysis problematic and increases the likelihood of basing conclusions on anomalous results.

Types of practitioners (physicians, medical students, alternative practitioners, etc.). If there were at least three studies that measured patient ratings of specific types of practitioners, we conducted a subgroup analysis of this group, and compared it with the complement.

Results

Main results

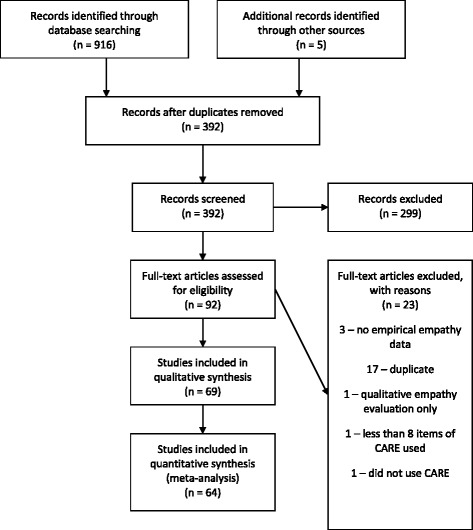

Our search yielded 392 independent records, of which 69 studies met our inclusion criteria (see Supplemental Material). Of these, 64 independent study groups (within 51 publications) had sufficient data to be included in our meta-analysis (see Table 1, Fig. 1, Additional file 3). See Additional file 4 for excluded studies.

Table 1.

Study groups included in meta-analysis (n = 64 published in 51 articles)

| Study | Country | Type of Providers | N Providers | % Female | N Patients | Mean (SD) consultation time (min) | Mean CARE score (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aomatsu (2014) | Japan | Physicians/Primary Care | 9 | N/A | 272 | 17.2 (14.3) | 38.4 (8.6) |

| Attar (2012) | India | Physicians/Specialists | N/A | 1.00 | 53 | N/A | 29.4 (10.9) |

| Bikker (2005) | UK | Physicians/CAM | 9 | N/A | 187 | 50.1 (14.0) | 45.0 (7.0) |

| Bikker (2015) | UK | Nurses | 17 | N/A | 774 | 13.0 (7.6) | 45.9 (5.9) |

| Birhanu (2012) | Ethiopia | Mixed | N/A | N/A | 768 | 6.3 (2.6) | 31.3 (8.3) |

| Buecken (2012) | Germany | Physicians/Specialists | N/A | N/A | 541 | N/A | 39.9 (9.1) |

| Chen (2015) | Hong Kong | Medical Students | 158 | 0.39 | 9 | 15.0 (N/A) | 35.8 (7.3) |

| Chung (2012) | South Korea | Physicians/CAM | 1 | 0.00 | 143 | 5.0 (N/A) | 38.0 (6.9) |

| Chung, Yip (2016) | Hong Kong | TCM practitioners | N/A | N/A | 514 | N/A | 34.2 (8.1) |

| Fogarty (2013) | Australia | TCM practitioners | 1 | 1.00 | 18 | 60.0 (N/A) | 49.8 (0.6) |

| Fritzsche (2011a) | China | Physicians/Specialists | 2 | N/A | 28 | N/A | 45.0 (5.2) |

| Fritzsche (2011b) | China | Physicians/Specialists | 5 | N/A | 37 | N/A | 36.7 (7.7) |

| Fritzsche (2011c) | China | Physicians/CAM | 4 | N/A | 31 | N/A | 42.9 (7.3) |

| Fung (2009) | Hong Kong | Physicians/Primary Care | 13 | N/A | 228 | 5.7 (3.9) | 31.8 (8.9) |

| Griffin (2014a) | UK | Physicians/Primary Care | N/A | N/A | 444 | N/A | 39.7 (9.9) |

| Griffin (2014b) | UK | Nurses | N/A | N/A | 444 | N/A | 30.4 (9.5) |

| Gu (2015) | Hong Kong | N/A | 332 | N/A | 332 | N/A | 31.0 (9.3) |

| Hanzevacki (2015) | Croatia | Physicians/Primary Care | 8 | N/A | 568 | 6.8 (N/A) | 35.9 (4.2) |

| Jani (2012) | UK | Physicians/Primary Care | 47 | N/A | 163 | 9.5 (4.5) | 43.8 (6.9) |

| Johnson (2012) | UK | Mixed | 21 | N/A | 1103 | N/A | 45.2 (6.2) |

| Johnston (2015) | UK | Mixed | 17 | N/A | 30 | N/A | 39.9 (8.7) |

| Joice (2010) | UK | Psychotherapist | N/A | N/A | 141 | N/A | 39.0 (8.0) |

| Kersten (2012) | UK | TCM practitioners | N/A | N/A | 213 | N/A | 42.2 (6.8) |

| Lafreniere (2015) | US | Physicians/Specialists | 44 | 0.57 | 244 | 41.2 (23.4) | 44.6 (6.7) |

| LaVela (2015) | US | Physicians/Specialists | N/A | N/A | 389 | N/A | 40.1 (9.9) |

| Lee (2012) | South Korea | Physicians/CAM | 1 | 0.00 | 110 | N/A | 36.0 (8.4) |

| Lelorain (2015) | France | Physicians/Specialists | 28 | N/A | 201 | 26.0 (14.0) | 38.4 (8.9) |

| MacPherson (2003) | UK | TCM practitioners | N/A | N/A | 135 | N/A | 45.5 (6.7) |

| Menendez (2015) | US | Physicians/Specialists | 4 | N/A | 112 | 11.0 (7.0) | 46.0 (6.8) |

| Mercer (2004) | UK | Physicians/Primary Care | N/A | N/A | 10 | N/A | 39.2 (10.8) |

| Mercer (2005) | UK | Physicians/Primary Care | 26 | N/A | 3044 | N/A | 40.9 (8.8) |

| Mercer (2008a) | UK | Physicians/Primary Care | 5 | 0.60 | 323 | 10.0 (N/A) | 42.4 (8.1) |

| Mercer (2008b) | UK | Physicians/Specialists | 31 | N/A | 1582 | N/A | 43.8 (6.6) |

| Mercer (2008c) | UK | Physicians/Specialists | 25 | N/A | 1015 | N/A | 43.5 (7.4) |

| Mercer (2011) | Hong Kong | Physicians/Primary Care | 20 | 0.30 | 984 | 5.5 (2.9) | 34.6 (8.8) |

| Murphy (2013a) | UK | Allied health professionals | N/A | N/A | 13 | N/A | 43.4 (7.4) |

| Murphy (2013b) | UK | Physicians/Primary Care | N/A | N/A | 86 | N/A | 43.9 (7.6) |

| Neumann (2007) | Germany | Physicians/Specialists | N/A | N/A | 326 | N/A | 37.1 (11.1) |

| Nezenega (2013) | Ethiopia | Mixed | N/A | N/A | 531 | 7.1 (4.4) | 35.9 (8.5) |

| Ohm (2013) | Germany | Medical Students | 30 | 0.73 | 5 | N/A | 41.3 (6.3) |

| Parrish (2016) | US | Physicians/Specialists | 5 | N/A | 112 | 10.0 (5.6) | 43.0 (8.0) |

| Place (2016a) | UK | Allied health professionals | N/A | 53 | N/A | 45.7 (5.1) | |

| Place (2016b) | UK | Allied health professionals | N/A | 217 | N/A | 46.3 (5.6) | |

| Pollak (2015) | US | Physicians/Specialists | 2 | N/A | 21 | N/A | 46.0 (4.2) |

| Price (2006) | UK | TCM practitioners | 15 | N/A | 52 | N/A | 42.4 (6.9) |

| Price (2008) | UK | Physicians/Primary Care | 35 | N/A | 2550 | 10.2 (5.5) | 43.2 (7.7) |

| Quaschning (2013) | Germany | Mixed | N/A | N/A | 402 | N/A | 41.5 (7.3) |

| Rees (2014) | UK | Allied health professionals | N/A | N/A | 225 | N/A | 43.1 (7.8) |

| Scales (2008) | US | Allied health professionals | 1 | N/A | 411 | N/A | 47.6 (4.4) |

| Scarpellini (2014) | Brazil | Physicians/Specialists | 12 | N/A | 12 | N/A | 41.4 (6.0) |

| Scheffer (2013a) | Germany | Medical Students | N/A | N/A | 103 | N/A | 45.4 (5.5) |

| Scheffer (2013b) | Germany | Medical Students | N/A | N/A | 94 | N/A | 41.7 (9.0) |

| Steinhausen (2014) | Germany | Physicians/Specialists | N/A | N/A | 120 | N/A | 38.0 (9.8) |

| Tran (2012) | Australia | Physicians/Primary Care | 3 | N/A | 38 | 15.0 (4.0) | 43.4 (4.2) |

| Weiss (2015) | UK | Mixed | 51 | 0.69 | 207 | N/A | 43.0 (7.4) |

| Wong (2013) | Hong Kong | Physicians/Primary Care | 9 | N/A | 1030 | 7.7 (4.7) | 34.4 (7.8) |

| Wu (2015a) | China | Physicians/Specialists | N/A | N/A | 199 | N/A | 39.6 (8.3) |

| Wu (2015b) | China | Physicians/CAM | N/A | N/A | 146 | N/A | 41.2 (8.6) |

| Wu (2015c) | China | Physicians/Specialists | N/A | N/A | 139 | N/A | 38.4 (8.7) |

| Yu (2015a) | Hong Kong | Physicians/not specified | 6 | 0.33 | 179 | 4.5 (2.4) | 29.2 (7.4) |

| Yu (2015b) | Hong Kong | Physicians/Specialists | 7 | 0.57 | 207 | 10.5 (8.6) | 35.5 (8.9) |

| Yu (2015c) | Hong Kong | Physicians/Primary Care | 14 | 0.50 | 435 | 7.4 (4.8) | 35.7 (8.3) |

| Zilliacus (2011a) | Australia | Physicians/Specialists | N/A | N/A | 178 | N/A | 41.3 (9.6) |

| Zilliacus (2011b) | Australia | Genetic Counselor | N/A | N/A | 152 | N/A | 44.6 (7.8) |

Fig. 1.

PRISMA Flow diagram

The 64 study groups were from 15 different countries: UK (n = 23), USA (n = 6), Hong Kong (n = 9), Germany (n = 7), Australia (n = 4), China (n = 6), Ethiopia (n = 2), South Korea (n = 2), and one study from each of Brazil, Croatia, France, India, and Japan. The types of practitioners included primary care physicians, practitioners of Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM), medical students, allied health professionals, and other specialists.

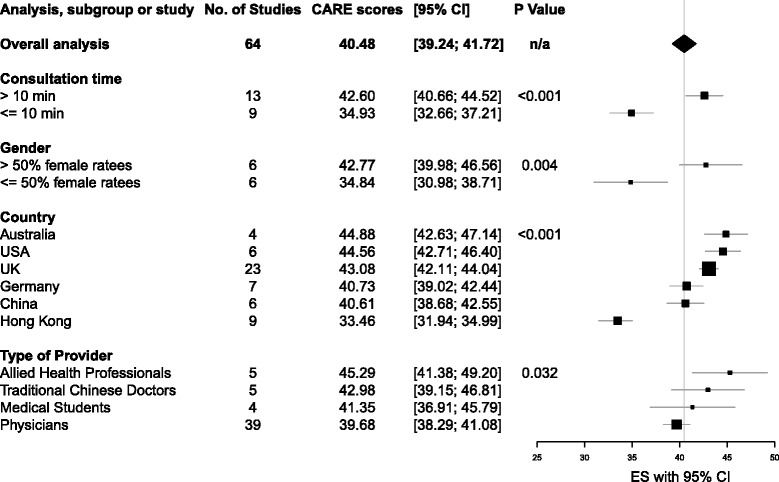

The average CARE score for the 64 study groups was 40.48 (95% CI, 39.24 to 41.72) (see Table 2, Fig. 2). Twenty-two studies reported consultation times. Longer consultations (≥10 min; n = 13) scored higher (42.60, 95% CI 40.69 to 44.52) than shorter (<10 min; n = 9) consultations (34.93, 95% CI 32.66 to 37.21). This difference of 7.67 points (15%) between longer and shorter consultations was highly significant (P < 0.001). Twelve studies provided data on the gender of practitioners (Table 2). Studies with predominantly female practitioners (n = 6) showed higher empathy scores (42.77, 95% CI 38.98 to 46.56) than those with predominantly male practitioners (n = 6, 34.85, 95% CI 30.98 to 38.71). This difference of 7.92 points (16%) was statistically significant (P = 0.004).

Table 2.

Summary of results from subgroup analyses

| Analysis | No. studies | Average CARE score (95% confidence interval) | P-value for difference (if applicable) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 64 | 40.48 (39.24 to 41.72) | n/a |

| Longer versus shorter consultations | 22 | ||

| Longer consultations (<10 min) | 13 | 42.60 (40.69 to 44.52) | <0.001 |

| Shorter consultations (≥10 min) | 9 | 34.93 (32.66 to 37.21) | |

| Proportion of female practitioners | 12 | ||

| < 50% female practitioners | 6 | 34.85 (30.98 to 38.71) | 0.004 |

| ≥ 50% female practitioners | 6 | 42.77 (38.98 to 46.56) | |

| By Country | 55 | ||

| UK | 23 | 43.08 (42.11 to 44.04) | No significant difference between UK, USA, Australia, Germany and China lower than USA and Australia, Hong Kong lower than all other countries |

| USA | 6 | 44.56 (42.71 to 46.40) | |

| Australia | 4 | 44.88 (42.63 to 47.14) | |

| Germany | 7 | 40.73 (39.02 to 42.44) | |

| China | 6 | 40.61 (38.68 to 42.55) | |

| Hong Kong | 9 | 33.46 (31.94 to 34.99) | |

| By type of provider | 53 | ||

| Allied Health Professionals | 5 | 45.29 (41.38 to 49.20) | 0.032 |

| Medical Students | 4 | 41.35 (36.91 to 45.79) | |

| Physicians | 39 | 39.68 (38.29 to 41.08) | |

| Traditional Chinese Doctors | 5 | 42.98 (39.15 to 46.81) |

Fig. 2.

Comparison of average CARE score within subgroups

Fifty-five study groups could be included in the pre-planned subgroup analysis by country (Table 2). Highest empathy scores were found in Australia (n = 4, 44.88, 95% CI 42.63 to 47.14), USA (n = 6, 44.56, 95% CI 42.71 to 46.40) and UK (n = 23, 43.07, 95% CI 42.11 to 44.04). Scores were lowest in Hong Kong (n = 9, 33.46, 95% CI 31.94 to 34.99). Scores in Germany (n = 7, 40.72, 95% CI 39.02 to 42.44) and China (n = 6, 40.61, 95% CI 38.68 to 42.55) were in-between. We added an exploratory analysis by country including all 64 study groups and found that scores in India (n = 1, 29.49, 95% CI 24.18 to 34.80) were lower than those in Hong Kong. Scores in the UK, USA and Australia were highest (See Additional file 5).

We found at least three studies each measured empathy in the following types of providers: physicians, medical students, allied health professionals, and practitioners of Traditional Chinese Medicine (Table 2). There was statistically significant heterogeneity between these (P = 0.032), with allied health professionals scoring the highest (n = 5, 45.29, 95% CI 41.38 to 49.20), and physicians scoring the lowest (n = 39, 39.68, 95% CI 38.29 to 41.08). We found no differences between primary care physicians, specialists, and complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) providers, (P = 0.386) (see Table 3).

Table 3.

CARE scores by physician specialty

| Analysis | No. studies | Average CARE score (95% confidence interval) |

|---|---|---|

| CAM | 5 | 40.83 (37.78 to 43.87) |

| Primary Care | 14 | 38.96 (37.14 to 40.76) |

| Specialists | 19 | 40.49 (38.93 to 42.05) |

A multivariable regression analysis was performed to analyze the predictive value of gender and consultation time with respect to CARE scores. Consultation duration was the only significant predictor for CARE scores (Table 4).

Table 4.

Multivariable regression analysis, with proportion of female practitioners and consultation time as independent variables and CARE scores as dependent variable (n = 8)

| Variable | Coefficient (ß) | Standard error | 95% CI | Wald χ2 | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 33.40 | 2.82 | 27.87 to 38.93 | 11.84 | <0.0001 |

| Proportion of female practitioners | 1.04 | 8.05 | −14.74 to 16.82 | 0.13 | 0.897 |

| Consultation duration | 0.26 | 0.11 | 0.04 to 0.48 | 2.27 | 0.023 |

Risk of bias

The response rate was reported in 20 of the 53 studies (38%), with the average rate being high (69%, ranging from 21% to 100%). The uncertainty about the remaining response rates entails a risk of response bias.

Discussion

We found that patient rating of practitioner empathy is highly variable, with some practitioners being reported to express empathy much less effectively to patients than others. Female practitioners, allied health professionals, those who spend more time with patients, and practitioners from Australia, the US, and the UK seem to display empathy more effectively than other practitioners. In addition, the average care score we identified was low in comparison with normative values, falling in the lowest 5% of CARE scores measured by the developers of the questionnaire [27]. The highly variable scores we found are likely to be associated with variable patient outcomes [9–11, 30].

Strengths and limitations

This is the first systematic review to investigate the extent to which healthcare practitioners are empathic. Another strength is that it used measures of the only validated patient-rated measure of practitioner empathy. As such, it provides a good indication of the differences between perceived empathy across gender, disciplines, and countries.

There are also several potential limitations. First, our method for measuring the difference between female and male practitioners was likely to be an underestimate. If studies with majority female practitioners resulted in greater patient-rated empathy, it is reasonable to assume that if all the practitioners were female, the difference between male and female practitioners would have been greater. In the context of this observational research we do not know whether the additional time caused female practitioners to be more empathic, or whether female practitioners’ higher empathy caused them to spend more time with patients, or whether these two factors cannot be separated. Second, response bias [26, 31, 32] could have affected the results. Patients who know they are rating their practitioners may wish to please their practitioners, [33] for example by giving them higher scores than they otherwise would [31, 32]. The lack of response rate reporting in most of the studies makes the extent of this problem unclear. Furthermore, selection bias might have influenced the results: the CARE questionnaire could be delivered in areas where the empathy of the practitioners is believed to be anomalous (either particularly high or particularly low). Next, the comparison between countries could have been influenced by the number of studies per country. Specifically, some of the countries with low scores had very few studies (Croatia had 1, Ethiopia had 2, and India had 1). Moreover in spite of validation of CARE translations, patients in different countries may have divergent prior expectations and beliefs about what it means to be an empathic practitioner. Finally, the comparison with normative values (resulting in the average score we found being in the lowest 5%) is problematic. In spite of being relatively low, the average score is still above 40. Further work needs to be done to investigate the meaning of average CARE scores.

Conclusions

Implications for clinical practice and clinical research

The way different healthcare practitioners express empathy to patients is low (on average) in comparison with normative scores, and highly variable. Given the likely association between practitioner empathy and patient outcomes, further research is now warranted to investigate how these findings can be used to improve patient care. Future reports of the CARE questionnaire should include all the potentially relevant factors we have identified here, especially details about response rates, and also consultation duration, gender, experience of practitioners, and other demographic details of patient raters and practitioners.

Additional files

The CARE Measure Questionnaire © Stewart W Mercer 2004. Actual questionnaire used within studies to measure patient perception of practitioner empathy (permission obtained). (DOCX 108 kb)

Search Strategy. Search terms used to identify studies for electronic searches. (DOCX 12 kb)

Studies that used the CARE measure (starred (*) studies not included in meta-analysis). References to studies not included in meta-analysis because they did not meet the inclusion criteria. (DOCX 141 kb)

Reasons for excluding studies identified in the search that were excluded from meta-analysis (n = 23). Summary of justification for not including studies in meta-analysis. (DOCX 48 kb)

CARE scores by country (all 64 studies included). Additional subgroup analysis by country. (DOCX 16 kb)

Acknowledgments

Bridget Johnson, Stewart Mercer, Vincent Chung, and Michelle Dossett shared their data with us when it was missing from published reports. Sir Muir Gray came up with the title for the paper. Claire Madigan provided some useful suggestions to improve the manuscript.

Funding

JH was supported by the Nuffield Department of Primary Care Health Sciences. KM received support from the Theophrastus Foundation and the Schweizer-Arau Foundation, Germany.

Availability of data and materials

All data available in manuscript, supplemental material, or by contacting authors.

Authors’ contributions

JH drafted the protocol; KM helped develop the protocol. JH piloted the data extraction form with help from KM. NR conducted the search; LS and AU completed the searches, conflicts were resolved by discussion with JH. KM conducted the statistical analyses. JH drafted the final manuscript with help from KM. LS, AU, and NR also helped to develop the final manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not relevant (systematic review).

Consent for publication

Not relevant (systematic review).

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s12909-017-0967-3) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Contributor Information

J. Howick, Phone: +44 (0) 1865 289258, Email: jeremy.howick@phc.ox.ac.uk

L. Steinkopf, Email: lsteinko@gmail.com

A. Ulyte, Email: agne.ulyte1@gmail.com

N. Roberts, Email: nia.roberts@bodleian.ox.ac.uk

K. Meissner, Email: karin.meissner@hs-coburg.de

References

- 1.Chassany O, Boureau F, Liard F, Bertin P, Serrie A, Ferran P, Keddad K, Jolivet-Landreau I, Marchand S. Effects of training on general practitioners' management of pain in osteoarthritis: a randomized multicenter study. J Rheumatol. 2006;33(9):1827–1834. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vangronsveld KL, Linton SJ. The effect of validating and invalidating communication on satisfaction, pain and affect in nurses suffering from low back pain during a semi-structured interview. Eur J Pain. 2012;16(2):239–246. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2011.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fujimori M, Shirai Y, Asai M, Kubota K, Katsumata N, Uchitomi Y. Effect of communication skills training program for oncologists based on patient preferences for communication when receiving bad news: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(20):2166–2172. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.51.2756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Soltner C, Giquello JA, Monrigal-Martin C, Beydon L. Continuous care and empathic anaesthesiologist attitude in the preoperative period: impact on patient anxiety and satisfaction. Brit J Anaesth. 2011;106(5):680–686. doi: 10.1093/bja/aer034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Little P, White P, Kelly J, Everitt H, Mercer S. Randomised controlled trial of a brief intervention targeting predominantly non-verbal communication in general practice consultations. Brit J Gen Pract. 2015;65(635):e351–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Kim SS, Kaplowitz S, Johnston MV. The effects of physician empathy on patient satisfaction and compliance. Eval Health Prof. 2004;27(3):237–251. doi: 10.1177/0163278704267037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Attar HS, Chandramani S. Impact of physician empathy on migraine disability and migraineur compliance. Annals of Indian Academy of Neurology. 2012;15(Suppl 1):S89–S94. doi: 10.4103/0972-2327.100025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Di Blasi Z, Harkness E, Ernst E, Georgiou A, Kleijnen J. Influence of context effects on health outcomes: a systematic review. Lancet. 2001;357(9258):757–762. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04169-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Derksen F, Bensing J, Lagro-Janssen A. Effectiveness of empathy in general practice: a systematic review. Br J Gen Pract. 2013;63(606):e76–e84. doi: 10.3399/bjgp13X660814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kelm Z, Womer J, Walter JK, Feudtner C. Interventions to cultivate physician empathy: a systematic review. BMC Med Educ. 2014;14:219. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-14-219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mistiaen P, van Osch M, van Vliet L, Howick J, Bishop FL, Di Blasi Z, Bensing J, van Dulmen S. The effect of patient-practitioner communication on pain: a systematic review. Eur J Pain. 2015;20(5):675–688. doi: 10.1002/ejp.797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Howick J, Rees S. Overthrowing barriers to empathy in healthcare: empathy in the age of the internet. J R Soc Med. 2017:141076817714443. http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/0141076817714443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Parker SM, Clayton JM, Hancock K, Walder S, Butow PN, Carrick S, Currow D, Ghersi D, Glare P, Hagerty R, et al. A systematic review of prognostic/end-of-life communication with adults in the advanced stages of a life-limiting illness: patient/caregiver preferences for the content, style, and timing of information. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2007;34(1):81–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2006.09.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Abraham A. Care and compassion: report of the health service ombudsman on ten investigations into NHS care of older people, fourth report if the health service commissioner for England; session 2010–2011. In. Edited by service PaH. London: The Stationary Office; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Francis R. Report of the mid Staffordshire foundation NHS trust public inquiry volumes 1–3, HC-898-I-III. In. London: The Stationary Office; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Davies HT, Mannion R. Will prescriptions for cultural change improve the NHS? BMJ. 2013;346:f1305. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f1305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Neumann M, Edelhauser F, Tauschel D, Fischer MR, Wirtz M, Woopen C, Haramati A, Scheffer C. Empathy decline and its reasons: a systematic review of studies with medical students and residents. Acad Med. 2011;86(8):996–1009. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e318221e615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Magasine GP. Quarter of GPs spend half their time on paperwork. In: GP Online: Haymarket Media Group Limited; 2012.

- 19.Aring CD. Sympathy and empathy. J Am Med Assoc. 1958;167(4):448–452. doi: 10.1001/jama.1958.02990210034008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Halpern J. From detached concern to empathy: humanizing medical practice. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Larson EB, Yao X. Clinical empathy as emotional labor in the patient-physician relationship. JAMA. 2005;293(9):1100–1106. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.9.1100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Decety J, Fotopoulou A. Why empathy has a beneficial impact on others in medicine: unifying theories. Front Behav Neurosci. 2014;8:457. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2014.00457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hemmerdinger JM, Stoddart SDR, Lilford RJ. A systematic review of tests of empathy in medicine. BMC Medical Education. 2007;7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Hojat M, Gonnella JS, Nasca TJ, Mangione S, Veloksi JJ, Magee M. The Jefferson scale of physician empathy: further psychometric data and differences by gender and specialty at item level. Acad Med. 2002;77(10 Suppl):S58–S60. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200210001-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mercer SW, Maxwell M, Heaney D, Watt GC. The consultation and relational empathy (CARE) measure: development and preliminary validation and reliability of an empathy-based consultation process measure. Fam Pract. 2004;21(6):699–705. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmh621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mercer SW, McConnachie A, Maxwell M, Heaney D, Watt GC. Relevance and practical use of the consultation and relational empathy (CARE) measure in general practice. Fam Pract. 2005;22(3):328–334. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmh730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.CARE Measure. http://www.measuringimpact.org/s4-care-measure. Accessed 31 July 2017.

- 28.Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins JPT. Comprehensive meta-analysis. In., 2.2.064 edn. Biostat: Englewood, NJ; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 29.NHS general practitioner (GP) services. http://www.nhs.uk/NHSEngland/AboutNHSservices/doctors/Pages/gp-appointments.aspx. Accessed 31 July 2017.

- 30.Kelley JM, Kraft-Todd G, Schapira L, Kossowsky J, Riess H. The influence of the patient-clinician relationship on healthcare outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. PLoS One. 2014;9(4):e94207. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0094207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Worsley A, Baghurst KI, Leitch DR. Social desirability response bias and dietary inventory responses. Hum Nutr Appl Nutr. 1984;38(1):29–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hróbjartsson A, Kaptchuk T, Miller FG. Placebo effect studies are susceptible to response bias and to other types of biases. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64(11):1223–1229. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2011.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Allan LG, Siegel S. A signal detection theory analysis of the placebo effect. Eval Health Prof. 2002;25(4):410–420. doi: 10.1177/0163278702238054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

The CARE Measure Questionnaire © Stewart W Mercer 2004. Actual questionnaire used within studies to measure patient perception of practitioner empathy (permission obtained). (DOCX 108 kb)

Search Strategy. Search terms used to identify studies for electronic searches. (DOCX 12 kb)

Studies that used the CARE measure (starred (*) studies not included in meta-analysis). References to studies not included in meta-analysis because they did not meet the inclusion criteria. (DOCX 141 kb)

Reasons for excluding studies identified in the search that were excluded from meta-analysis (n = 23). Summary of justification for not including studies in meta-analysis. (DOCX 48 kb)

CARE scores by country (all 64 studies included). Additional subgroup analysis by country. (DOCX 16 kb)

Data Availability Statement

All data available in manuscript, supplemental material, or by contacting authors.