Abstract

Objective

Cumulative adverse childhood experiences (ACE) can have profound and lasting effects on parenting. Parents with a history of multiple ACE have greater challenges modulating their own stress responses and helping their children adapt to life stressors. This paper examines pediatric practice in inquiring about parents’ childhood adversities as of 2013.

Methods

Using data from the 85th Periodic Survey of the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), we restricted analyses to the 302 pediatricians exclusively practicing general pediatrics who answered questions regarding their beliefs about childhood stressors, their role in advising parents, and whether they asked about parents’ ACE. Weighted descriptive and logistic regression analyses were conducted.

Results

Despite endorsing the influence of positive parenting on a child’s life-course trajectory (96%), that their advice can impact parenting skills (79%), and that screening for social-emotional risks is within their scope of practice ((81%), most pediatricians (61%) did not inquire about parents’ ACE. Pediatricians who believed that their advice influences positive parenting skills inquired about more parents’ ACE

Conclusion

As of 2013, few pediatricians inquired about parents’ ACE despite recognizing their negative impact on parenting behaviors and child development‥ Research is needed regarding the best approaches to the prevention and amelioration of ACE and the promotion of family and child resilience. Pediatricians need resources and education about the AAP’s proposed dyadic approach to assessing family and child risk factors and strengths and to providing guidance and management.

Keywords: Adverse Childhood Experiences, Parents’ ACE, parenting, pediatric primary care

INTRODUCTION

Cumulative Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE), especially in the first 3 years of life, have profound and lasting negative effects on physical health,1 brain development,1,2 and mental health.3,4 The original ACE study demonstrated a dose-dependent impact of early life intra-familial adversities (such as maltreatment, exposure to domestic violence and parental mental health and substance abuse problems) on later-in-life risk-taking, unhealthy lifestyles, and disease. Moreover, cumulative ACE are also associated with suboptimal parenting styles. 4–7 Parents with a history of multiple ACE have greater challenges modulating their own stress responses and helping their children adapt to life stressors.6,7

Recent research in immunology, genetics, endocrinology, neuroscience and child development has led to an understanding of how ACE lead to chronic activation of the body’s physiologic stress responses and inflammatory pathways and lead to the biological embedding of stress. 3,5,6 Moreover, intra-familial ACE, probably through changes in gene regulation, unless buffered, can increase the likelihood of intergenerational transmission of trauma and adversity. 6,8,9

Parenting, however, occurs in a broad ecological context.10 Only one third of maltreating parents report being victimized as children,11 implying that factors beyond ACE, such as personality, coping skills, and social supports may buffer the impact of ACE on parenting. 11,12 However, other factors, such as poverty, unemployment and intimate partner violence may exacerbate the impact. Simply put, while parents’ ACE are an important determinant of parenting and children’s outcomes, other salient factors can also impact those outcomes.9

Since 2012, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) has made significant efforts to raise pediatricians’ awareness about ACE and their effects on early brain and child development.13–15 The AAP now emphasizes a dyadic approach to the prevention and amelioration of ACE and encourages pediatricians to promote resilience through early identification and management of families at risk, a focus on child and family strengths, and teaching positive parenting strategies.15–18 In 2013, despite the absence of validated screening tools for this purpose, the AAP recommended that pediatricians inquire about both parent and child ACE and for adversities beyond the original ACE at well child visits.16,19–21

In 2013, the AAP included questions about ACE on the Periodic Survey (PS85) to better understand whether and how pediatricians are utilizing knowledge about ACE in their practices. The survey appeared shortly after the first policy statement on toxic stress, and largely predated the AAP’s emphasis on a two-generation approach and the availability of validated ACE screening tools. The survey thus provides valuable baseline data about pediatricians’ practices prior to the development of AAP recommendations. In a previous analysis of this survey, we examined pediatricians’ beliefs about the impact of ACE and their perceived role in inquiring about children’s ACE and offering parenting advice.22 In this paper, we analyzed much of the same survey data to determine: 1) the number of parents’ ACE pediatricians inquire about; 2) the association between_respondents’ personal and practice characteristics and inquiring about parents’ ACE; and, 3) the association between respondents’ attitudes/beliefs about ACE and the number of parents’ ACE they inquire about.

METHODS

Survey Administration

The AAP Periodic Survey (PS) is a national survey of U.S. non-retired AAP members (N=54,491 in 2013) that has been conducted multiple times yearly since 1987 to inform policy, develop new initiatives or evaluate current projects and practice (www.AAP.org). The 2013 questionnaire was sent 7 times to 1617 randomly selected members beginning in July 2013 and ending in December 2013. This questionnaire, which is available through the AAP Department of Research, was 8 pages in length, was pretested for clarity and approved by the AAP Institutional Review Board prior to the first mailing. 594 (36.7%) pediatricians responded to the 2013 survey.

Survey Questions

The respondents were asked a broad range of questions used in previous Periodic Surveys about socio-demographic and practice characteristics. Additionally, the survey included questions about 8 of the original ACE and one other adversity, food insecurity. Using a 4-point ordinal scale (all, most, some, none), pediatricians were asked to select what proportion of parents they ask about their experiences with 8 specific ACE (physical or sexual abuse, emotional abuse, physical or emotional neglect, domestic violence, parent mental illness, parent substance abuse, raised by one parent and incarceration of a caregiver) and food scarcity, as a child.14 We included food scarcity, or food insecurity, which was the only non-ACE social determinant of health inquired about in the survey, since it is a recognized marker for poor health outcomes. No other social determinants of health were inquired about in the survey. Due to the small proportion of responses in the “all” category for each ACE, the “all” and “most” categories were combined in the analyses. The number of ACE pediatricians ask most/all parents about was then categorized as: none, 1–2, 3–9. We chose these categories because adult data indicates that ACE scores greater than 3 are predictive of poorer outcomes.

Pediatricians were queried about their familiarity with the original ACE study (very, somewhat, vaguely, not at all). A series of 7 questions with responses on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree were used to assess respondents’ beliefs about: the pathophysiology of ACE; the impact of excessive prolonged stress on children; the impact of ACE on parenting; and, the role of protective factors. For positively worded questions, strongly agree/agree responses were compared to neutral, disagree and strongly disagree; for negatively worded questions, strongly disagree/disagree were compared to the other three categories. Physicians were also asked if significant adversity in childhood was related to 7 health outcomes (yes, no, don’t know). Additionally, using the 5-point Likert scale described above, pediatricians were asked to rate their level of agreement that: 1) screening for social emotional risk factors within the family was beyond the scope of the pediatric medical home; and, 2) pediatric advice has little impact on parenting skills. Lastly, pediatricians were asked if they had received training during their residency or fellowship about positive parenting techniques for parents of children or adolescents.

Statistical Analyses

Respondents were nearly identical to full AAP membership on sex and region and to non-respondents, except they were slightly older than non-respondents (46.6 vs 43.6 years). Sample weights were created to minimize potential bias due to differential non-response and to ensure that the respondents were representative of the membership. Logistic regression was used to estimate the probability of responding to the survey to create a propensity score; auxiliary information available for both responders and non-responders were included as predictors (age, sex, region, and membership status). The final logistic regression model included the three-way interaction of age, sex, and region as well as their two-way interactions and main effects; those who did not respond were more likely to be younger females practicing in the Northeast or Midwest. Ten groups were created using deciles of the propensity score distribution, and the average propensity score ( ) was calculated for each group. The sample weight was the inverse of the average propensity score ( ) for each group. The sample weights were rescaled such that the average was 1 and the sum was equal to the analytic sample size.

Weighted means and standard errors were used to summarize continuous measures, while categorical measures were summarized using weighted percentages. Bivariate associations with the number of ACE pediatricians ask most/all patients’ parents about were assessed using weighted logistic regression and the Rao-Scott Chi-Square test. Statistical significance was set at p<.05. Analyses were performed using procedures appropriate for survey data in SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Physician and Practice Characteristics

The analyses were restricted to the 302 physicians who completed their residency training, exclusively practice general pediatrics, and completed the majority of the survey questions about ACE. About two-thirds of the analytic sample were female, with an average age in the mid- forties, and distributed relatively evenly by length of time they were in practice <10 years, 10–19 years and ≥20 years (Table 1). Less than half (48%) reported residency or fellowship training in positive parenting techniques.

Table 1.

Physician/Practice Characteristics, and Familiarity with ACEs and Positive Parenting for the Analytic Sample and Bivariate Associations With the Number of Parents’ Childhood ACEs that Pediatricians Ask Most/All Patients’ Parents

| Number of Parents’ Childhood ACEs Pediatricians Ask Most/All Patients’ Parents |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Analytic Sample (n=302) |

None (n=183) |

1–2 (n=72) |

3–9 (n=47) |

p-val | |

| Physician Characteristics | |||||

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 31.9 | 58.6 | 21.1 | 20.3 | .27 |

| Female | 68.1 | 61.6 | 25.3 | 13.1 | |

| Age, yrs; mean (SE) | 46.0 (0.6) | 45.4 (0.8) | 45.8 (1.3) | 48.4 (1.8) | .30 |

| Race/Ethnicity | |||||

| Caucasian | 74.6 | 60.0 | 24.7 | 15.3 | .96 |

| Asian | 11.5 | 58.9 | 24.6 | 16.5 | |

| Other/Unknown | 13.9 | 65.3 | 19.7 | 15.0 | |

| Years in Practice | |||||

| 1–4 | 21.3 | 70.6 | 20.0 | 9.4 | .29 |

| 5–9 | 16.5 | 57.5 | 25.7 | 16.8 | |

| 10–19 | 29.6 | 51.8 | 30.8 | 17.4 | |

| ≥20 | 32.6 | 64.0 | 18.9 | 17.1 | |

| Practice characteristics | |||||

| Area | |||||

| Urban | 39.1 | 65.4 | 15.7 | 18.9 | .05 |

| Suburban | 50.7 | 56.5 | 31.3 | 12.2 | |

| Rural | 10.2 | 60.3 | 20.9 | 18.8 | |

| Type of Practice | |||||

| 1 or 2 physicians | 8.7 | 61.3 | 20.8 | 17.9 | .41 |

| Group practice | 52.7 | 61.7 | 27.3 | 11.0 | |

| Multi-specialty | 12.1 | 52.6 | 26.5 | 20.9 | |

| Medical School / parent university | 7.2 | 69.6 | 11.7 | 18.7 | |

| Other | 19.3 | 58.9 | 19.3 | 21.8 | |

| Practice Characteristics | |||||

| Ambulatory visits per week | |||||

| ≥ 100 | 34.8 | 61.9 | 21.4 | 16.7 | .73 |

| < 100 | 65.2 | 60.2 | 25.2 | 14.6 | |

| Caucasian patients, % | |||||

| <75% | 77.1 | 62.3 | 21.3 | 16.4 | .15 |

| ≥75% | 22.9 | 55.7 | 32.5 | 11.8 | |

| Patient insurance | |||||

| <80% have private insurance | 60.3 | 64.2 | 19.4 | 16.4 | .25 |

| ≥80% have private insurance | 25.6 | 56.1 | 31.1 | 12.8 | |

| Unknown | 14.1 | 53.2 | 30.6 | 16.2 | |

| Positive Parenting Techniques and Familiarity with ACEs | |||||

| Residency or fellowship training in positive parenting techniques for parents of children or adolescents | |||||

| No | 52.3 | 64.7 | 22.5 | 12.8 | .26 |

| Yes | 47.7 | 56.1 | 25.6 | 18.3 | |

| Familiarity with ACEs study | |||||

| Very | 2.3 | 58.8 | 14.3 | 26.9 | .48 |

| Somewhat | 8.4 | 59.8 | 26.1 | 14.1 | |

| Vaguely | 13.4 | 69.0 | 11.2 | 19.8 | |

| Not at all | 76.0 | 59.1 | 26.4 | 14.5 | |

Weighted mean (SE) or weighted % shown

Weighted % shown

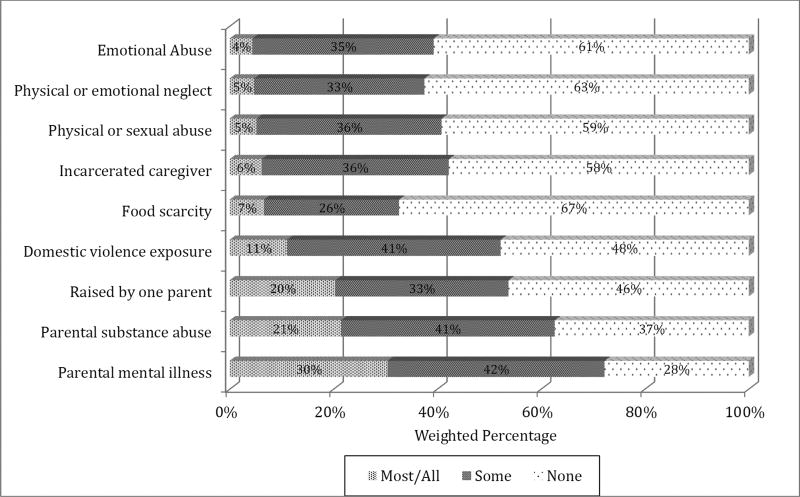

Asking about Parental ACE

Pediatricians recall asking only a small proportion of their patients’ parents about their childhood adversities (Figure 1). Overall, 61% did not ask most/all parents about any parental ACE: 24% asked about 1–2 parental ACE, and only 15% asked about 3 or more parental ACE. The most frequently asked about parental ACE was a family history of mental illness, but only 30% of respondents asked most/all parents about this, while 42% asked some parents. About 20% of pediatricians asked most/all parents about parental substance abuse (21%) and whether they were raised by a single parent (20%). In addition, 11% of respondents asked most/all parents about exposure to domestic violence and less than 7% asked most/all parents about having an incarcerated caregiver, a history of maltreatment (physical or sexual abuse, emotional abuse, and neglect) or childhood food insecurity.

Figure 1.

Weighted Percentage of Pediatricians Who Ask Patients’ Parents About their Adverse Childhood Experiences

Familiarity with the ACE Study and Beliefs About the Impact of ACE

As we reported previously,22 respondents were largely unfamiliar with the ACE study. Only 2% were very familiar, 8% were somewhat familiar, 13% were vaguely familiar, and 76% were not at all familiar with the ACE study (Table 1). Only 34% of all general pediatricians agreed/strongly agreed that prolonged or excessive physiologic stress in childhood can result in epigenetic modification of DNA (Table 2). Moreover, just over half (57%) agreed/strongly agreed that brief periods of stress can have a positive effect on a child by serving to motivate and build resilience.

Table 2.

Beliefs About the Impact of ACEs for the Analytic Sample and Bivariate Associations with the Number of Parents’ Childhood ACEs Pediatricians Ask Most/All Patients’ Parents*

| Analytic Sample (n=302) |

Number of Parents’ Childhood ACEs Pediatricians Ask Most/All Patients’ Parents |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| None (n=183) |

1–2 (n=72) |

3–9 (n=47) |

p-val | ||

| Prolonged or excessive physiologic stress in childhood can result in epigenetic modification of the DNA | |||||

| Disagree* | 66.3 | 61.3 | 25.1 | 13.6 | .44 |

| Agree | 33.7 | 58.6 | 22.2 | 19.2 | |

| Prolonged or excessive physiologic stress in childhood can disrupt brain development and impair educational achievement | |||||

| Disagree* | 3.7 | 81.9 | 8.4 | 9.7 | .32 |

| Agree | 96.3 | 59.7 | 24.6 | 15.7 | |

| Persistent physiologic stress in childhood can make children less capable of coping with future stress | |||||

| Disagree* | 8.3 | 59.3 | 19.9 | 20.8 | .71 |

| Agree | 91.7 | 60.6 | 24.4 | 15.0 | |

| Brief periods of stress can have a positive effect on a child by serving to motivate and build resilience | |||||

| Disagree* | 42.8 | 58.2 | 24.4 | 17.4 | .68 |

| Agree | 57.2 | 62.4 | 23.6 | 14.0 | |

Weighted % shown

Disagree includes neutral, disagree, strongly disagree; agree includes agree and strongly agree.

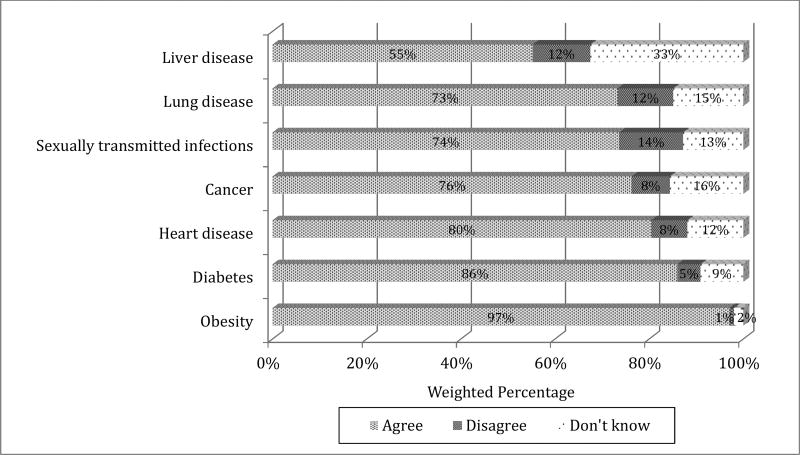

Nearly all respondents recognized the impact of ACE on developmental and mental health outcomes. Specifically, they agreed that prolonged or excessive stress can have a negative impact on brain development and educational achievement (96%) and coping with future stress (92%) (Table 2). In addition, the majority of pediatricians agreed that prolonged or excessive physiologic stress can result in a variety of poor physical health outcomes (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Beliefs About Whether Health Outcomes Are Associated with Significant Adversity in Childhood

Parenting and the Role of the Pediatrician

As shown in Table 3, and reported in Kerker et. al, 2015, the majority of pediatricians recognized the potential negative impact of parental ACE on the parent-child relationship: 58% agreed or strongly agreed that parents who have experienced significant adversity in childhood have a harder time forming stable and supportive relationships with their children. Moreover, 84% of pediatricians agreed that stable and supportive adult relationships can mitigate the negative effects of persistent childhood stress, and 96% disagreed that positive parenting has little influence on a child’s life-course trajectory. Altogether, 79% disagreed that advice from pediatricians has little effect on influencing positive parenting skills among patients’ parents and 81% disagreed that screening for social-emotional risk factors within the family are beyond the scope of the pediatric medical home.

Table 3.

Beliefs About Relationships and the Pediatricians’ Role for the Analytic Sample and Bivariate Associations with Number of Parents’ Childhood ACEs Pediatricians Ask Most/All Patients’ Parents

| Analytic Sample (n=302) |

Number of Parents’ Childhood ACEs Pediatricians Ask Most/All Patients’ Parents |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| None (n=183) |

1–2 (n=72) |

3–9 (n=47) |

p-val | ||

| Parents who have experienced significant adversity in childhood have a harder time forming stable and supportive relationships with their children | |||||

| Disagree* | 41.7 | 57.0 | 29.9 | 13.1 | .11 |

| Agree | 58.3 | 63.2 | 19.7 | 17.1 | |

| Stable and supportive adult relationships can mitigate the negative effects of persistent childhood stress | |||||

| Disagree* | 16.4 | 45.3 | 39.4 | 15.3 | .02 |

| Agree | 83.6 | 63.7 | 20.7 | 15.6 | |

| Positive parenting has little influence on a child’s life-course trajectory | |||||

| Disagree** | 95.6 | 60.9 | 23.6 | 15.5 | .76 |

| Agree | 4.4 | 53.2 | 32.6 | 14.2 | |

| Advice from pediatricians has little effect on influencing positive parenting skills among patients’ parents | |||||

| Disagree** | 78.8 | 55.8 | 25.7 | 18.5 | .003 |

| Agree | 21.2 | 77.6 | 18.1 | 4.3 | |

| Screening for social emotional risk factors within the family are beyond the scope of the pediatric medical home | |||||

| Disagree** | 81.1 | 58.8 | 24.1 | 17.1 | .22 |

| Agree | 18.9 | 68.4 | 23.2 | 8.4 | |

Weighted % shown

Disagree includes neutral, disagree and strongly disagree; agree includes agree and strongly agree

Disagree includes disagree and strongly disagree; agree includes neutral, agree and strongly agree

Bivariate Associations with the Number of Parent ACE Pediatricians Ask Most/All Patients’ Parents

A greater proportion of pediatricians practicing in suburban areas asked most/all parents about 1–2 ACE compared to pediatricians practicing in urban areas (Table 1). No other physician/practice characteristics were associated with asking about parental ACE, including training in positive parenting techniques and familiarity with the ACE Study. Respondents who agreed that advice from pediatricians influences positive parenting skills among patients’ parents were significantly more likely to ask parents about 3 or more specific ACE, although 56% of this group still did not ask parents about any of the 8 parental ACE or food insecurity (Table 3). Unexpectedly, those who agree that stable and supportive adult relationships can mitigate the negative effects of persistent childhood stress were less likely to inquire about parents’ ACE. None of the other beliefs about the impact of excessive childhood stress was significantly associated with asking about parents’ ACE or food insecurity (Tables 2 and 3).

DISCUSSION

This is the first national study to examine whether pediatricians inquire about parents’ ACE. We examined data from the AAP’s Periodic Survey, conducted in 2013 regarding screening for both parents’ and children’ ACE. The survey largely predated the AAP’s educational efforts around ACE and the pathophysiology of stress. Thus, this study serves as a baseline for future investigations regarding the degree and timing of implementation of the AAP’s recommendations. We also examined whether respondents’ beliefs about the impact of parents’ ACE, the role of positive parenting skills in ameliorating the impact of childhood adversities, and the pediatrician’s role in advising parents about parenting, affected inquiring about parents’ ACE.

Given that this survey largely predated AAP efforts to educate pediatricians about ACE and toxic stress, it is not surprising that few pediatricians inquired about parents’ ACE. Only 15% of pediatricians asked most/all parents about 3 or more ACE. Inquiry about parents’ ACE, however, was associated with respondents’ beliefs in the potential positive impact of their advice in influencing parenting strategies, although not associated with their training experience, age, or gender. Other findings are more difficult to understand. Pediatricians who believed that supportive adult relationships mitigate the negative effects of childhood stress were less likely to ask about most/all parental ACE and those practicing in suburban settings were more likely to ask about 1–2 parental ACE than those in other settings.

In the years since the PS85 survey was conducted, the AAP has made significant efforts to fill the knowledge gap identified in this study among pediatricians.1,2,6,13–15,23 The AAP has also emphasized the role of positive parenting in promoting child resilience in response to stress.13,14,24 Our results indicate that there was ample need for the AAP and other organizations to engage in these educational efforts as of 2013.

Families identify pediatricians as the most trusted and helpful early childhood professionals and interact with them frequently when children are young.25,26 Parents rely on pediatricians for advice about parenting and help with managing child behavioral, mental health and developmental problems.26 And, pediatricians recognize that how parents raise their children is heavily rooted in the parents’ own childhood experiences.15,21,27

One of the major challenges, moving forward, will be deciding which families to screen. The unexpected high prevalence of ACE in a relatively low risk population in the initial studies suggests the need for universal assessment.23,27 The long-term negative effects of childhood adversity and its impact on parenting imply that pediatricians should, as the AAP recommends, adopt a two-generation approach to all families in order to reduce missed opportunities for intervention.28 Pediatricians are the first professionals with expertise in child development and family dynamics that parents encounter and those who gain insight into parents’ ACE can better understand the attitudes, strengths and challenges an individual brings to parenting their children.12,15,24 While remediation later in life can have some benefit,19,29 the earlier in life pediatricians act to identify and assess and address parental stress, the better the potential outcomes for children. However, pediatricians have many competing demands on their time. As child development experts and prevention professionals, pediatricians will need validated screening instruments to identify children and parents at risk for poor outcomes that can be easily and efficiently implemented.

There is substantial literature about the negative impact of parental stress on child and family outcomes30–35 and the power of efficacious interventions to support positive child development.36 Fortunately, there is a growing array of evidence-based interventions that have been shown to improve family dynamics, reduce parent stress, improve child mental health outcomes and normalize diurnal cortisol regulation. 8,28,34,37 However, pediatricians will need tools to educate and empower parents, promote positive parenting, and to connect families to potentially therapeutic community programs and effective trauma-informed mental health services. 27

One reason pediatricians were not asking about parents” ACE in 2013 was the lack of knowledge about them. Once knowledge expands, other barriers may emerge, including lack of confidence or skills in asking uncomfortable questions, lack of time, limited reimbursement, and a lack of specific resources for parents who have experienced significant ACE. ACE may also be a particularly sensitive topic for pediatricians to ask about and future studies should explore barriers and facilitators.

Medical school and pediatric residency curricula should include scientific information about the impact of ACE and toxic stress on early brain development because of its relevance across the life-course, and pediatricians should take a dyadic developmental approach to child health.19,28,38 In pediatrics, weaving educational modules into maintenance of certification and other educational venues (EQuIP, etc.), and widely distributed publications (AAP news, etc.) may help raise pediatrician awareness.

Pediatricians also have a role in advocacy for evidence-based, cost-effective interventions shown to improve child outcomes,15,19 including nurse home-visiting programs,39,40 quality early childhood education41, and public health campaigns promoting positive parenting strategies (e.g., Triple P).19,29 And, finally, a trauma exposure prevention and research agenda should include a focus on both child and parent resilience. 27

While the major strength of this study is that it is based on a nationally representative sample, this is counterbalanced by several limitations. The response rate was suboptimal, although not unusual for surveys of physician.39,42 Analysis of response bias in AAP surveys also shows little non-response bias.43 Examination of the survey sample and AAP membership shows no differences on a limited set of characteristics, and the survey was weighted for non-response. However, it is unlikely that all of the non-response bias was corrected since we have only a limited number of characteristics on which to compare responders and non-responders and it is likely that those pediatricians interested in the topic were more likely to respond.29 It is also possible that non-respondents rarely screen for parental ACE, in which case our findings may over-estimate the prevalence of pediatricians who ask about parents’ ACE. Given the possibility of response bias for professionally desirable behaviors, it is possible that respondents overestimated how often they inquire about parents’ ACE. Finally, as with all cross-sectional studies, the results are associations and do not imply causality.

CONCLUSIONS

This examination of a national survey of pediatricians in 2013 predated much of the AAP’s educational efforts around ACE and toxic stress and thus serves as a baseline for future studies. Pediatricians seemed to have an intuitive understanding that childhood adversity and stress have negative long-term effects on health, mental health and were more likely to inquire about parents’ ACE if they believed their advice impacted parenting. However, the data suggest that there is a need for a robust national educational campaign around ACE, toxic stress and positive parenting and for resources, such as validated ACE screeners. A research agenda should address barriers to inquiring about parents’ ACE and strategies to overcome them, as well as interventions to improve the identification and amelioration of ACE and the promotion of child and family resilience.

What’s New

Pediatricians have an intuitive understanding that childhood adversity impacts an individual’s future health, mental health and parenting, but pediatricians only infrequently inquire about parental ACE. The data in this paper serve as a baseline for future studies in pediatric practice change.

Acknowledgments

Funding Source: American Academy of Pediatrics supported this research. NIMH P30 MH09 0322 (PI K. Hoagwood) supported Dr. Kerker, Dr. Storfer-Isser, Dr. Hoagwood and Dr. Horwitz’s participation in this research.

Abbreviations

- ACE

Adverse Childhood Experiences

- AAP

American Academy of Pediatrics

- PS

Periodic Survey

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Financial Disclosure: None

Conflict of Interest: None

Contributors’ Statement:

Moira Szilagyi, M.D., Ph.D.: Dr. Szilagyi developed a portion of the survey, conceptualized the analyses, drafted the initial manuscript and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Bonnie D. Kerker, Ph.D.: Dr. Kerker conceptualized the analyses, critically reviewed all drafts, and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Amy Storfer-Isser, Ph.D.: Dr. Storfer-Isser conducted the analyses, drafted sections of the manuscript, critically reviewed all drafts, and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Ruth EK Stein, M.D.: Dr. Stein participated in the development of the survey, critically reviewed all drafts, and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Andrew Garner, M.D., Ph.D.: Dr. Garner developed a portion of the survey, critically reviewed all drafts, and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Karen G. O’Connor, B.S.: Ms. O’Connor designed and conducted the survey, critically reviewed all drafts, and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Kimberly E. Hoagwood, Ph.D.: Dr. Hoagwood critically reviewed all drafts and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Sarah M. Horwitz, Ph.D.: Dr. Horwitz participated in the development of the survey, critically reviewed all drafts, and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

References

- 1.Anda R, Felitti V, Bremner J, et al. The enduring effects of abuse and related adverse experiences in childhood. A convergence of evidence from neurobiology and epidemiology. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2006;256:174–86. doi: 10.1007/s00406-005-0624-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McEwen BS, Gianaros PJ. Central role of the brain in stress and adaptation: links to socioeconomic status, health, and disease. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;1186:190–222. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05331.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maughan A, Cicchetti D, Toth SL, Rogosch FA. Early-occurring maternal depression and maternal negativity in predicting young children’s emotion regulation and socioemotional difficulties. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2007;35:685–703. doi: 10.1007/s10802-007-9129-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown G, Craig T, Harris T. Parental maltreatment and proximal risk factors using the Childhood Experience of Care; Abuse (CECA) instrument: A life-course study of adult chronic depression. J Affective Disorders. 2008;110:222–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2008.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rikhye K, Tyrka A, Kelly M, et al. Interplay between childhood maltreatment, parental bonding, and gender effects: impact on quality of life. Child Abuse Negl. 2008;32:19–34. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2007.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van der Kolk B. Developmental Trauma Disorder. Psychiatric Annals. 2005;35:401–8. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mantymaa M, Puura K, Luoma I, Latva R, Salmelin RK, Tamminen T. Predicting internalizing and externalizing problems at five years by child and parental factors in infancy and toddlerhood. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 2012;43:153–70. doi: 10.1007/s10578-011-0255-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bernard K, Hostinar CE, Dozier M. Intervention Effects on Diurnal Cortisol Rhythms of Child Protective Services-Referred Infants in Early Childhood: Preschool Follow-up Results of a Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169:112–9. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2014.2369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Banyard VL, Williams LM, Siegel JA. The impact of complex trauma and depression on parenting: an exploration of mediating risk and protective factors. Child maltreatment. 2003;8:334–49. doi: 10.1177/1077559503257106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Belsky J. The determinants of parenting: a process model. Child development. 1984;55:83–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1984.tb00275.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kaufman J, Zigler E. Do abused children become abusive parents? Am J Orthopsychiatry. 1987;57:186–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.1987.tb03528.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Horwitz S, Hurlburt M, Heneghan A, et al. Persistence of mental health problems in very young children investigated by US child welfare agencies. Acad Pediatr. 2013;13:524–30. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2013.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shonkoff JP, Garner AS, Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of C et al. The lifelong effects of early childhood adversity and toxic stress. Pediatrics. 2012;129:e232–46. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-2663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Garner AS, Shonkoff JP, Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of C et al. Early childhood adversity, toxic stress, and the role of the pediatrician: translating developmental science into lifelong health. Pediatrics. 2012;129:e224–31. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-2662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johnson SB, Riley AW, Granger DA, Riis J. The science of early life toxic stress for pediatric practice and advocacy. Pediatrics. 2013;131:319–27. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-0469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cohen J, Kelleher K, Mannarino A. Identifying, treating and referring traumatized children: the role of pediatric providers. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2008;162:447–52. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.162.5.447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dowd M, Forkey H, Gillespie R, Petterson T, Spector L, Stirling J. Trauma Toolbox for Primary Care. American Academy of Pediatrics; 2014. 2014 ed. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hagan J, Shaw J, Duncan P, editors. Guidelines for Health Supervision of Infants, Children and Adolescents. Third. 2008. Bright Futures. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Conti G, Heckman JJ. The developmental approach to child and adult health. Pediatrics. 2013;(131 Suppl 2):S133–41. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-0252d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Finkelhor D, Shattuck A, Turner H, Hamby S. Improving the adverse childhood experiences study scale. JAMA Pediatr. 2013;167:70–5. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Forkey H, Szilagyi M. Foster care and healing from complex childhood trauma. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2014;61:1059–72. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2014.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kerker B, Storfer-Isser A, Szilagyi M, et al. Do pediatricians ask about adverse childhood experiences in pediatric primary care? Acad Pediatr. 2016;16:154–60. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2015.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Felitti V, Anda R, Nordenberg D, et al. Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. Am J Prev Med. 1998;14:245–58. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(98)00017-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shonkoff JP, Boyce WT, McEwen BS. Neuroscience, molecular biology, and the childhood roots of health disparities: building a new framework for health promotion and disease prevention. JAMA. 2009;301:2252–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Young KT, Davis K, Schoen C, Parker S. Listening to parents. A national survey of parents with young children. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1998;152:255–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moseley KL, Freed GL, Goold SD. Which sources of child health advice do parents follow? Clin Pediatr. 2011;50:50–6. doi: 10.1177/0009922810379905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dowd M, Gillespie R. Practical approaches in the primary care setting with patients exposed to violence American Academy of Pediatrics. 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Garner AS, Forkey H, Szilagyi M. Translating Developmental Science to Address Childhood Adversity. Acad Pediatr. 2015;15:493–502. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2015.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Davidson RJ, McEwen BS. Social influences on neuroplasticity: stress and interventions to promote well-being. Nat Neurosci. 2012;15:689–95. doi: 10.1038/nn.3093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Choe D, Olson S, Sameroff A. Effects of early maternal distress and parenting on the development of children’s self-regulation and externalizing behavior. Dev Psychopathol. 2013;25:437–63. doi: 10.1017/S0954579412001162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cicchetti D, Rogosch FA. The impact of child maltreatment and psychopathology on neuroendocrine functioning. Dev Psychopathol. 2001;13:783–804. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Malik N, Boris N, Heller S, Harden B, Squires J, Chazan-Cohen R. Risk for maternal depression and child aggression in Early Head Start Families: A test of ecological models. Infant Mental Health J. 2007;28:171–91. doi: 10.1002/imhj.20128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Min MO, Singer LT, Minnes S, Kim H, Short E. Mediating links between maternal childhood trauma and preadolescent behavioral adjustment. J Interpers Violence. 2013;28:831–51. doi: 10.1177/0886260512455868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fisher PA, Stoolmiller M. Intervention effects on foster parent stress: associations with child cortisol levels. Dev Psychopathol. 2008;20:1003–21. doi: 10.1017/S0954579408000473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Owen AE, Thompson MP, Kaslow NJ. The mediating role of parenting stress in the relation between intimate partner violence and child adjustment. J Fam Psychol. 2006;20:505–13. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.20.3.505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tu M, Gruneau R, Petrie-Thomas J, Haley D, Weinberg J. Maternal stress and behavior modulate relationships between neonatal stress, attention and basal cortisol at 8 months in preterm infants. Develop Psychobiol. 2007;491:150–64. doi: 10.1002/dev.20204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fisher PA, Gunnar MR, Dozier M, Bruce J, Pears KC. Effects of therapeutic interventions for foster children on behavioral problems, caregiver attachment, and stress regulatory neural systems. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2006;1094:215–25. doi: 10.1196/annals.1376.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Szilagyi M, Halfon N. Pediatric Adverse Childhood Experiences: Implications for Life Course Health Trajectories. Academic pediatrics. 2015;15:467–8. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2015.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Asch DA, Jedrziewski MK, Christakis NA. Response rates to mail surveys published in medical journals. J Clin Epidemiol. 1997;50:1129–36. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(97)00126-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Olds DL, Eckenrode J, Henderson CR, Jr, et al. Long-term effects of home visitation on maternal life course and child abuse and neglect. Fifteen-year follow-up of a randomized trial. JAMA. 1997;278:637–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Muennig P, Schweinhart L, Montie J, Neidell M. Effects of a prekindergarten educational intervention on adult health: 37-year follow-up results of a randomized controlled trial. Am J Public Health. 2009;99:1431–7. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.148353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cummings SM, Savitz LA, Konrad TR. Reported response rates to mailed physician questionnaires. Health Serv Res. 2001;35:1347–55. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cull WL, O’Connor KG, Sharp S, Tang SF. Response rates and response bias for 50 surveys of pediatricians. Health Serv Res. 2005;40:213–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2005.00350.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]