Abstract

Background: In most of the world, diagnostic surgery remains the most frequent approach for indeterminate thyroid cytology. Although several molecular tests are available for testing in centralized commercial laboratories in the United States, there are no available kits for local laboratory testing. The aim of this study was to develop a prototype in vitro diagnostic (IVD) gene classifier for the further characterization of nodules with an indeterminate thyroid cytology.

Methods: In a first stage, the expression of 18 genes was determined by quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) in a broad histopathological spectrum of 114 fresh-tissue biopsies. Expression data were used to train several classifiers by supervised machine learning approaches. Classifiers were tested in an independent set of 139 samples. In a second stage, the best classifier was chosen as a model to develop a multiplexed-qPCR IVD prototype assay, which was tested in a prospective multicenter cohort of fine-needle aspiration biopsies.

Results: In tissue biopsies, the best classifier, using only 10 genes, reached an optimal and consistent performance in the ninefold cross-validated testing set (sensitivity 93% and specificity 81%). In the multicenter cohort of fine-needle aspiration biopsy samples, the 10-gene signature, built into a multiplexed-qPCR IVD prototype, showed an area under the curve of 0.97, a positive predictive value of 78%, and a negative predictive value of 98%. By Bayes' theorem, the IVD prototype is expected to achieve a positive predictive value of 64–82% and a negative predictive value of 97–99% in patients with a cancer prevalence range of 20–40%.

Conclusions: A new multiplexed-qPCR IVD prototype is reported that accurately classifies thyroid nodules and may provide a future solution suitable for local reference laboratory testing.

Keywords: : indeterminate thyroid nodules, gene classifier, qPCR, in vitro diagnostic test

Introduction

In the last decade, a significant increase in the incidence of thyroid cancer has been reported worldwide mainly due to the extensive availability of routine high-resolution ultrasound (1–3). Consequently, a growing number of fine-needle aspiration (FNA) biopsies are being performed to determine if thyroid nodules in asymptomatic patients are malignant (4). In the United States, approximately 350,000 FNAs are performed each year, of which 20% are reported as indeterminate (5). Based on current practice, surgery is recommended for a significant number of these cases, although the malignancy prevalence in indeterminate thyroid nodules (ITN) is 15–25% (6). Thus, a significant number of unnecessary surgeries are performed yearly, exposing patients to surgical risks and permanent hormone supplementation, as well as generating major costs to health systems (3).

Recently, several molecular tests have emerged to improve the diagnosis of ITN based on two strategies (7). One approach is to rule in malignancy based on the detection of specific DNA mutations and/or chromosomal rearrangements (8). This approach requires high specificity and positive predictive value (PPV) to identify patients who would benefit from surgery (6). The alternative approach is to rule out malignancy, which uses mRNA or microRNA gene expression profiles, where high sensitivity and negative predictive value (NPV) are required to recommend clinical follow-up safely (9–12). New tests with sufficient predictive values to rule in and rule out malignancy have been described. Such tests could reduce the need for diagnostic lobectomy in low-risk patients while providing guidance for surgery for high-risk cases (12–14).

Although these tests provide a solution for ITN, access to these assays is still limited, since they require shipping samples overseas to centralized laboratories that have developed in-house “laboratory-developed tests.” Moreover, in the absence of an in vitro diagnostic test (IVD or Kit) for local reference clinical laboratories, surgery remains the most frequent choice to determine the definitive diagnosis of ITN in most of the world. An IVD requires a reduced number of biomarkers, low turnaround time, and high compatibility with widely available diagnostic platforms (e.g., real-time polymerase chain reaction [qPCR]). In addition, an IVD should achieve an NPV of at least 95% (similar to the estimated true negative rate of Bethesda II cytology) and be cost-effective (i.e., specificity >78% in order to reduce unnecessary surgeries significantly) (6,15). To the authors' knowledge, no IVD for ITN with these features has been reported, thus limiting the access of patients to molecular diagnostic evaluation as an alternative to surgery.

The purpose of this study was to develop a prototype test able to classify thyroid nodules accurately and which can be performed as an IVD assay in reference laboratories. Using a multicenter cohort, a novel multiplexed-10-gene qPCR thyroid genetic classifier (TGC) with high sensitivity and specificity is reported.

Materials and Methods

Sample collection

Fresh tissue thyroid biopsies (hereafter referred to as “tissue biopsies”) were prospectively collected between 2013 and 2014 at the clinical hospital of the Pontifical Catholic University. Tissue biopsies were collected in the operating room from patients undergoing lobectomy or total thyroidectomy and immediately placed in RNALater (Ambion). FNA samples were prospectively collected by ultrasound guidance between 2014 and 2015 in five academic centers, stabilized in RNAprotect Cell Reagent (Qiagen) and stored at −80°C until RNA extraction. Patients signed an informed consent, previously approved by the Ethics Committee of each institution. The surgical pathology report was used as the gold standard for comparing both the tissue biopsies and the FNA cytologies in the Bethesda III, IV, V, and VI categories. Since cases with Bethesda II did not undergo surgery, the cytology was considered as the gold standard (6).

Patients cohorts

Samples from tissue biopsies were stratified per histological diagnosis. Then, samples from each subtype diagnosis were randomly assigned to the training or the testing set (Fig. 1). The minimum sample size for each set was calculated based on the World Health Organization recommendations for clinical studies with a power of 80% and 95% accuracy (16). A blinded operator to the molecular diagnosis matched the classifier score to the respective surgical pathological report for each patient.

FIG. 1.

Study design flow diagram.

After at least six months of follow-up of a multicenter cohort of 1056 FNA samples, a surgical pathology report (gold standard) was obtained in 91/189 indeterminate cases (Bethesda III/IV; Fig. 1). To complete the cohorts, an additional 45 non-indeterminate samples were randomly selected (15 Bethesda V/VI and 30 Bethesda II; Fig. 1). Samples were then stratified per the cytology report and outcome (cancer/benign) and randomly assigned, as shown in Figure 1.

Histopathological characteristics and the TNM stage of all malignant samples are described in Supplementary Table S1 (Supplementary Data are available online at www.liebertpub.com/thy).

RNA extraction and cDNA synthesis

Total RNA from tissue biopsies and FNAs was extracted with the RNeasy Plus-Mini Kit (Qiagen). Total RNA concentration was determined using the Qubit RNA HS Assay Kit and Qubit® 3.0 fluorometer (Invitrogen). Reverse transcription reactions were performed in a final volume of 20 μL by using 1 μg of total RNA from tissue biopsies or 50 ng from FNA with the Improm II™ Reverse Transcription System (Promega) following the manufacturer's instructions.

Biomarkers selection

Biomarkers for consideration were identified from a PubMed search (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/) for genes reported to show differential expression and/or biological significance in thyroid carcinogenesis/inflammation. To avoid genomic amplification, primers used for tissue biopsy analysis were designed in different exons using the Primer-BLAST software (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/tools/primer-blast/). For FNA samples, specific commercially available Taqman probes were purchased (Thermo Fisher). The list of primers and Taqman assays for the target genes are shown in Supplementary Table S2.

qPCR

Briefly, for tissue biopsies, reverse transcription (RT) reactions were performed with 1000 ng of total RNA. All qPCR reactions were performed in a final volume of 20 μL of reaction mixture containing 2 μL of cDNA, 10 μL of 2 × Brilliant II SYBR Green qPCR Master Mix (Agilent), 250 nM of each primer, and nuclease-free water. All qPCR reactions were run in the Rotor-Gene Q cycler (Qiagen). Conditions for amplification were: 10 min at 95°C, followed by 40 cycles of 20 s at 95°C, 20 s at 60°C, and 20 s at 72°C. Melting curve analysis was performed by increasing the temperature 1°C/s, from 72°C to 95°C. Reactions with a cycle threshold >35 and/or deficient melting curves were not considered.

For FNA samples, multiplex qPCR reactions of the prototype IVD were designed to include one target gene and two reference genes. Reactions were standardized following the manufactures recommendations (https://tools.thermofisher.com/content/sfs/manuals/taqman_optimization_man.pdf). All qPCR reactions were performed by adding 2 μL of 1:5 RT reaction dilution in a final volume of 20 μL containing 10 μL of 2 × Taqman Multiplex Master Mix with Mustang Purple (Life Technologies), sequence-specific Taqman® assays (Thermo Fisher), and nuclease-free water. All qPCR reactions were run in the Rotor-Gene Q thermocycler (Qiagen). Conditions for amplification were: 10 min at 95°C, followed by 40 cycles of 10 s at 95°C, and 20 s at 60°C.

Classifier development

Initially, classifiers were developed using linear discriminant analysis (LDA) (17) or non-linear discriminant analysis (NLDA) (18) with a cross-validation sequence using SPSS v15.0 software (SPSS, Inc.). To optimize classifier performance further, a novel statistical outlier classifying system (OCS) was developed to identify and classify samples with atypical gene expression profiles. Briefly, for each biomarker a Gaussian equation for gene expression distribution was calculated, and outlier values were defined as those >95th percentile or <5th percentile. Then, outlier values were identified for all genes in each sample (Fig. 2C, step 1). In samples with at least one outlier value, the probability of being malignant or benign was calculated for each outlier gene. Probabilities were then integrated into a linear function generating a composite score (Fig. 2C, step 2). Samples with composite scores greater than defined cutoff values were classified as malignant or benign with 100% accuracy (Fig. 2C, step 2). Samples with no outlier values (step 1) or with a composite score not classified by OCS (step 2) followed the discriminant analysis classification process (Fig. 2C, step 3). Thus, the OCS and discriminant analysis approaches were sequentially combined in a final algorithm, as shown in Figure 2C.

FIG. 2.

Development of a thyroid genetic classifier (TGC) that effectively classifies indeterminate thyroid nodules (ITN). (A) Differential gene expression between malignant and benign tissue biopsy samples. Gene expression was determined by quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) in 71 benign and 43 malignant fresh tissue biopsies. To calculate the gene expression for each sample (benign or malignant), the target gene was normalized by two reference genes (Supplementary Table S2). Bars represent the differential gene expression of malignant samples with respect to the average gene expression of benign (*p < 0.05). (B) TGC-3 shows high and reproducible sensitivity and specificity. Comparative performance of three genetic classifiers developed by two different approaches: non-linear discriminant analysis (TGC-1 and TGC-2) and LDA (TGC-3). Values of sensitivity (white circles) and specificity (black circles) are shown for classifiers trained with and without outlier classifying system (OCS). The testing set sensitivity and specificity is shown only for classifiers also trained by the OCS. (C) TGC model. High-level diagram of the final algorithm. Gene expression data were analyzed through three consecutive steps. In step 1, values <5th percentile or >95th percentile were identified for each gene (atypical values). Then, a lineal function integrated the atypical values of each sample obtaining the OCS score. Two cutoff points were set to classify samples with higher or lower OCS scores as malignant or benign, respectively, with 100% of accuracy (step 2). In step 3, samples without atypical values and samples that were not classified in step 2 were classified based on lineal discriminant analysis. Finally, output scores from both, OCS and discriminant analysis, were integrated to assess the performance of the classifiers (step 4).

Statistical analysis

Collected data were organized in Microsoft® Office Excel 2011 v14.0, and plotted in GraphPad v5.0 (GraphPad Software, Inc.). For tissue biopsies, gene expression was analyzed by Pfaffl's method (19,20). Sensitivity, specificity, PPV, NPV, positive likelihood ratio (LR+), negative likelihood ratio (LR–), and the area under the curve (AUC) were estimated by receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves. Multiple comparison tests were performed using Tukey's range test. Significant differential expression was estimated by Wilcoxon's signed-rank test. Significant p-values were set <0.05. All statistical analysis was performed using SPSS v15.0 software.

Results

TGC effectively classifies thyroid nodules in tissue biopsies

The expression level of 18 genes was determined by qPCR in a broad spectrum of histopathological categories of 114 tissue biopsies (Supplementary Table S3). By Pfaffl's analysis, six genes (CCR3, KRT19, TIMP1, CLDN1, HMOX1, and CCR7) were significantly overexpressed (p < 0.05), while three genes (SPAG9, CXADR, and NECTIN1) were significantly underexpressed with respect to benign (p < 0.05; Fig. 2A). The diagnostic performance of each gene is shown in Supplementary Table S4. No single gene reached the minimum required performance to classify thyroid nodules properly as malignant or benign. However, KRT19, TIMP1, and CLDN1 showed the greatest relative fold change of gene expression (Fig. 2A) and the best diagnostic performance (AUC >0.80; Supplementary Table S4). Thus, a classifier using these genes was developed by non-stepwise LDA, reaching a sensitivity of 88% [confidence interval (CI) 74–96%], specificity of 39% [CI 28–52%], and AUC of 0.85 [CI 0.76–0.90]. Classifier performance was similar to that observed for each individual gene (corrected p-value >0.05; Supplementary Fig. 1A). Considering that synergistic performance was not observed for these three genes, a close correlation between them was hypothesized. In fact, Spearman's test showed that KRT19, TIMP1, and CLDN1 are significantly correlated (p < 0.01; Supplementary Fig. S1B, C, and D), suggesting that they correctly and incorrectly identified malignancy in the same cases. In the same discovery cohort but using all 18 genes, three additional gene classifiers were developed by NLDA (TGC-1, TGC-2) and stepwise-LDA (TGC-3). TGC-1 (CXCR3, CLDN1, CCR7, and TIMP1) and TGC-2 (CXADR, CLDN1, HMOX1, and CCR3) reached a sensitivity of 88% and 84%, and a specificity of 52% and 77%, respectively (Fig. 2B). TGC-3 (CLDN1, AFAP1L2, CXADR, HMOX1, CXCR3, and CXCL10) achieved a sensitivity of 93% [CI 80–98%] and a specificity of 58% (CI 45–69%] (Fig. 2B).

Although TGC-1, TGC-2, and TGC-3 provided improved sensitivity and specificity, they did not achieve the appropriate performance to be clinically useful. This could be explained, in part, by a broad distribution of gene expression data. In fact, analysis of the data revealed that expression values for at least one or more genes were outliers (i.e., >95th percentile or <5th percentile) in approximately 55% of samples. To address data dispersion, a statistical OCS was developed to identify outlier gene expression and assign the probability of the sample being benign or malignant for each gene. Then, probabilities were integrated into a linear function, generating a composite score (Fig. 2C, steps 1 and 2). Cutoff scores were set sufficiently conservative in order to assure that samples that met OCS criteria were classified with 100% accuracy. Considering that OCS identified and correctly classified samples with outlier expression profiles, it was hypothesized that a TGC developed by combining OCS and discriminant analysis in a two-step process could improve the diagnostic performance of TGCs. Therefore, samples not identified as outliers by OCS were used to train classifiers by NLDA or LDA in a second step (Fig. 2C, step 3). Overall, the OCS improved classifier performance with a significant increase of specificity in TGCs 1 and 3, reaching 66% and 81%, respectively (Fig. 2B). The performance of TGCs was tested in an independent cohort of 139 tissue biopsies. Only the TGC-3, augmented by four additional genes following the OCS analysis including CCR3, KRT19, TIMP1, and CCR7, showed a clinically acceptable performance, with a sensitivity of 93% [CI 80–98%] and a specificity of 81% [CI 72–88%] (Fig. 2B). Based on these results, a combined approach of OCS and stepwise-LDA was selected as the definitive development strategy to define the final algorithm (Fig. 2C).

An IVD-TGC effectively classifies ITN in FNA samples

A prototype multiplexed qPCR-IVD classifier (IVD-TGC) was developed based on the 10-gene signature and the combined OCS/stepwise-LDA approach used in TGC-3. A total of 1056 FNA samples were collected from a prospective multicenter cohort. A training set was built by randomly selecting 45 non-indeterminate cases and randomly assigning 24 indeterminate cases. The remaining 67 indeterminate cases were used as the independent statistical validation set (Fig. 1). Details of both cohorts are described in Table 1. In the training set, the diagnostic performance achieved an AUC of 0.99 [CI 0.97–1.00], a sensitivity of 93% [CI 74–99%], a specificity of 91% [CI 77–97%], a LR+ of 9.72 [CI 3.81–24.85], and a LR– of 0.08 [CI 0.02–0.31] (Table 2). The PPV and NPV were 86% [CI 67–96%] and 95% [CI 82–99%], respectively. The OCS step correctly classified two malignant and eight benign samples, representing 15% of the cohort (Fig. 3). In the statistical validation set, the IVD-TGC reproduced its performance, showing an AUC of 0.97 [CI 0.93–1.00], a sensitivity of 96% [CI 75–99%], a specificity 87% [CI 75–95%], a LR+ of 7.16 [CI 3.38–15.16], and a LR– of 0.05 [CI 0.01–0.36] (Table 2), The PPV and NPV were 78% [CI 57–90%] and 98% [CI 85–100%], respectively. The OCS step classified two malignant and five benign samples, representing 10% of the cohort (Fig. 3).

Table 1.

Clinical Truth of Fine-Needle Aspiration Biopsies

| Training set | Statistical validation set | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bethesda category | II | III | IV | V–VI | Total | III | IV | Total | p-Value |

| Proportion of indeterminate samples | 24 (35%) | 67 (100%) | |||||||

| Benign | 30 (71%) | 7 (17%) | 5 (12%) | 42 | 14 (31%) | 31 (69%) | 45 | n.s. | |

| Follicular hyperplasia | 5 (17%) | 2 (29%) | 0 (0%) | 7 (17%) | 4 (29%) | 15 (48%) | 19 (42%) | ||

| Colloid nodule | 18 (60%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 18 (43%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | ||

| Adenomatoid hyperplasia | 0 (0%) | 3 (43%) | 1 (20%) | 4 (10%) | 1 (7%) | 3 (10%) | 4 (9%) | ||

| Chronic thyroiditis | 7 (23%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 7 (17%) | 3 (21%) | 2 (6%) | 5 (11%) | ||

| Follicular adenoma | 0 (0%) | 1 (14%) | 3 (60%) | 4 (10%) | 5 (36%) | 10 (32%) | 15 (33%) | ||

| Hürthle cell adenoma | 0 (0%) | 1 (14%) | 1 (20%) | 2 (5%) | 1 (7%) | 1 (3%) | 2 (4%) | ||

| Malignant | 3 (11%) | 9 (33%) | 15 (56%) | 27 | 5 (23%) | 17 (77%) | 22 | n.s. | |

| Papillary thyroid carcinoma | |||||||||

| Usual type | 1 (33%) | 1 (11%) | 11 (73%) | 13 (48%) | 2 (40%) | 4 (24%) | 6 (27%) | ||

| Follicular variant | 2 (67%) | 2 (22%) | 1 (7%) | 5 (19%) | 2 (40%) | 5 (29%) | 7 (32%) | ||

| Hürthle cell variant | 0 (0%) | 1 (11%) | 3 (20%) | 4 (15%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (6%) | 1 (5%) | ||

| Follicular thyroid carcinoma | |||||||||

| Microinvasive | 0 (0%) | 3 (33%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (11%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (18%) | 3 (14%) | ||

| Widely invasive | 0 (0%) | 2 (22%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (7%) | 1 (20%) | 2 (12%) | 3 (14%) | ||

| Medullary thyroid carcinoma | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (12%) | 2 (9%) | ||

| Total | 69 | 67 | |||||||

| Cancer prevalence | 39% | 33% | n.s. | ||||||

n.s., not significant.

Table 2.

Statistical Performance of IVD-TGC

| FNAB training set | FNAB statistical validation set | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Statistical parameter | Value | CI | Value | CI |

| Cancer prevalence | 39% | [28 – 52%] | 33% | [22 – 45%] |

| Area under the ROC | 0.99 | [0.97 – 1.00] | 0.97 | [0.93 – 1.00] |

| Sensitivity | 93% | [74 – 99%] | 96% | [75 – 99%] |

| Specificity | 91% | [77 – 97%] | 87% | [73 – 95%] |

| Positive likelihood ratio | 9.72 | [3.81 – 24.85] | 7.16 | [3.38 – 15.16] |

| Negative likelihood ratio | 0.08 | [0.02 – 0.31] | 0.05 | [0.01 – 0.36] |

| Positive predictive value | 86% | [67 – 96%] | 78% | [57 – 90%] |

| Negative predictive value | 95% | [82 – 99%] | 98% | [85 – 100%] |

IVD-TGC, in vitro diagnostic thyroid genetic classifier; FNAB, fine-needle aspiration biopsy; CI, confidence interval; ROC, receiver operating characteristic curve.

FIG. 3.

TGC effectively classifies ITN fine-needle aspiration (FNA) biopsy samples. Dispersion graph of TGC scores from FNA training and statistical validation sets. Cutoff score to classify samples as malignant or benign was 0.32. The OCS classified samples with TGC score of 1 as malignant and samples with TGC score of 0 as benign.

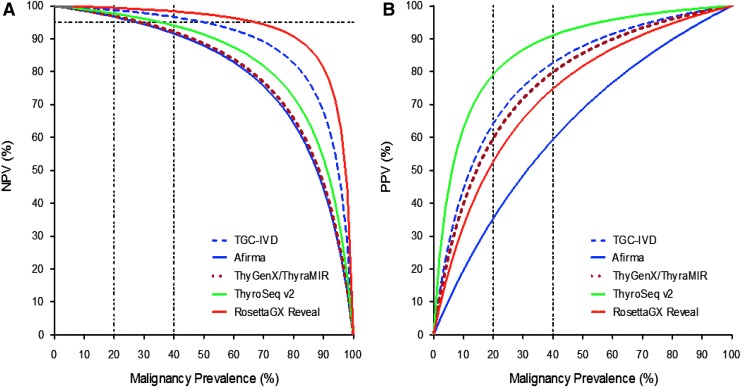

IVD-TGC reaches high theoretical diagnostic performance in a broad cancer prevalence range

The predictive values of the IVD-TGC were estimated using Bayes' theorem. The NPV and PPV of the classifier were compared with commercially available molecular tests for indeterminate cytology (e.g., Afirma, ThyGenX/ThyraMIR, ThyroSeqv2, and RosettaGX Reveal; Fig. 4). In this analysis, the performance of prototype studies for each test was considered, as reported in the literature (9,11,13,14). In a cancer prevalence range for indeterminate cytologies of 20–40%, which is reported in most clinical centers, a 95% NPV was set to rule out malignancy, with a maximum residual risk of cancer of 5%, associated with benign cytology (6). The predicted NPV remained >95% for RosettaGX Reveal and the IVD-TGC (Fig. 4A), while the PPV was >80% only for ThyroSeq v2 (Fig. 4B).

FIG. 4.

Bayes' theorem analysis shows a high theoretical performance of the in vitro diagnostic (IVD) TGC. Expected predictive performance of the IVD-TGC and other genetic classifiers (Afirma, ThyGenX/ThyraMIR, ThyroSeq v2, and RosettaGX Reveal) was assessed in a broad cancer prevalence considering the sensitivity and specificity reported in the prototype studies. (A) Estimated negative predictive value (NPV) for IVD-TGC and other molecular tests. A NPV of 95% was set as the minimum value to rule out malignancy. (B) Estimated positive predictive value for IVD-TGC and other molecular tests.

Discussion

In the United States, new emerging molecular tests able to improve the nature of ITN have gained adoption, helping to identify patients who could avoid surgery (10,12–14,21). This has been supported by the new 2015 American Thyroid Association guidelines, which have recommended considering molecular testing in patients with Bethesda III and IV cytologies (6). Accumulating evidence is showing clinical utility and cost-effectiveness for these assays (7,15,22), suggesting that the demand for molecular testing will increase. However, given the limited access of patients to centralized testing systems outside the United States, diagnostic surgery continues to be the most frequent approach in the rest of the world. To address this problem, the objective was to develop a high-performance diagnostic prototype assay for ITN, such that its technical complexity would allow its use as an IVD in reference laboratories. This study reports a new 10-gene TGC based on a multiplexed qPCR design, which accurately classifies thyroid nodules, providing optimal performance for both strategies (i.e., to rule in and rule out a malignancy) in samples with an indeterminate thyroid cytology. The achieved performance and prototype configuration sets the basis for an IVD test, which may provide a future solution for ITN diagnosis in reference laboratories.

To account for most frequent cell subtypes observed in FNA samples, a variety of epithelial and inflammatory biomarkers were chosen, which have previously shown a differential expression between benign and malignant thyroid nodules (23–25). When the diagnostic performance of each individual gene was analyzed, three predominantly epithelial biomarkers showed AUCs >0.80 (KRT19, TIMP1, and CLDN1). However, combining them in a classifier did not significantly improve the AUC, which may be explained by a close biological relationship between them, as shown by the finding of a high statistical gene expression correlation (Supplementary Fig. S1). When classifiers were trained with all 18 genes, including epithelial and inflammatory markers, an improvement in sensitivity and specificity was observed (Fig. 2B). It is likely that the inclusion of inflammatory biomarkers representing a broader spectrum of cell types significantly improved the discrimination between malignant and benign thyroid nodules, although the individual AUC of several genes was low. This highlights that the use of high-performing biomarkers (epithelial) alone is insufficient to reach optimal diagnostic performance, and including apparently poor-performing biomarkers (mostly inflammatory) seems to be key for correct ITN classification. Consistently, previous gene classifiers have been reported to include a combination of both epithelial and inflammatory biomarkers, where poorly performing genes may help to recognize stromal or inflammatory patterns of cell populations associated with different histopathology subtypes (11,26,27).

Despite the improved sensitivity observed in classifiers trained with all genes, the classifiers trained by two classical approaches (LDA and NLDA) in a stepwise sequence did not reach the target specificity (80%) recommended for molecular diagnosis of ITN (6). Further detailed analysis of the data showed that almost two thirds of patient samples had at least one gene with an expression value of more than two standard deviations, suggesting that data dispersion might have reduced the performance of the classifier. To address this issue, a new statistical method was developed that would identify and classify samples with outlier gene expression profiles with 100% accuracy (OCS). Remarkably, by adding this new step to the algorithm, a significant improvement of performance was observed in specificity of at least two classifiers. In addition, it is noteworthy that the OCS identified 11% of benign cases in the statistical validation set, confirming its utility in classifying true negative samples, thereby improving specificity. However, only one classifier (TGC-3), developed by LDA, showed consistent OCS improvement of specificity, while classifiers generated by NLDA did not provide reproducible performance. This may be explained by the complex non-linear equations generated by NLDA, which may increase the risk of classifier overfitting in the training set. Wylie et al. have reported that a simple linear equation for a miRNA classifier is more robust and presents lower error rates than more complex equations developed by other machine learning approaches (12). Thus, the present findings indicate that the proper classification of outlier samples improves specificity, and that a simple equation generated by LDA contributes to the robustness of the algorithm.

Currently, there are few validated multianalyte tests in IVD format in oncology, given the challenge of rigorous controls required to guarantee simultaneous reproducibility of multiple analytes. Further, the algorithm is considered a separate medical device, requiring significant independent validation for Food and Drug Administration clearance. To the best of the authors' knowledge, no clinically useful IVD has been reported for the diagnosis of ITN. For breast cancer, Endopredict is an eight-gene qPCR classifier in IVD format, successfully validated in both analytical and clinical studies (28,29). In addition, Endopredict has shown 100% reproducibility among seven laboratories, providing evidence that multi-analyte-qPCR gene expression IVD tests can be a reliable system for more complex IVD testing in oncology (29). In this study, the best classifier generated with fresh tissue samples was used as a guide to develop a prototype test with the basic features of a qPCR IVD assay. This was achieved by using highly specific and sensitive Taqman multiplexed amplification of target sequences, together with two reference genes, which allowed the number of reactions to be reduced and the normalization of the biomarker expression levels to be optimized. This assay configuration was used to analyze a set of 136 FNA samples obtained from a prospective multicenter study (Fig. 1), showing an excellent and consistent performance in the statistical validation set, even surpassing the observed in tissue biopsies (Table 2).

Predictive values of molecular classifiers depend on the prevalence of malignancy. Thus, the recommendation is to interpret these tests in light of the reported cancer prevalence in each institution (30,31). Bayes' theorem analysis showed that the TGC-IVD would theoretically perform optimally as a rule-in/rule-out test in a cancer prevalence range of 20–40%. Therefore, data from the TGC-IVD could potentially result in a reduced number of unnecessary surgeries when the test result is negative and could be used to support surgery in the case of a positive result. Given the strong dependency between the clinical utility of classifiers and the prevalence of malignancy in ITN, it is necessary to consider the recent reclassification of non-invasive encapsulated follicular variant of papillary thyroid carcinoma as non-invasive follicular thyroid neoplasm with papillary-like nuclear features (NIFTP) (32). Since there is a high frequency of follicular variant cancers in ITN, reclassification to NIFTP would reduce the prevalence of malignancy in indeterminate FNAs, which in turn would affect the predictive performance of available diagnostic tests. Although NIFTP are low-risk lesions, the NIFTP cases of the training set were considered as malignant in order to develop the classifier, since this reclassification was suggested after the study had concluded. However, further genetic profiling may allow this histological subtype to be accurately predicted.

In summary, this study reports a novel test that accurately classifies ITN in a prototype IVD format. This was possible by utilizing an optimized machine learning approach that identified a small gene signature able to classify ITN accurately. In addition, the data highlight the importance of including biomarkers found in a wide range of thyroid nodules, and of addressing gene expression variability (outliers) for establishing accurate diagnoses. Although the data are encouraging, two ongoing independent multicenter clinical validity trials in a large set of indeterminate samples should further determine the clinical performance of this assay. The clinical validation of the TGC-IVD could potentially help clinicians and patients to have access to a widely available test that accurately identifies benign and malignant thyroid nodules, thereby helping to reduce the rate of unnecessary diagnostic surgeries in patients with ITN.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Bryan McIver, Pablo Valderrabano, and Chris Holsinger for their helpful and valuable comments of this study. This work was supported by the Biomedical Research Consortium (grant no. 13CTI-21526P2 and CORFO 14IEAT-28672).

Author Disclosure Statement

N.M., M.B., G.M., and E.B. are employed by GeneproDX. H.E.G. owns shares at GeneproDX. H.E.G., J.R.M., and S.V. are inventors of Patent WO2014085434 A1. No competing financial interests exist for the remaining authors.

References

- 1.Sipos JA, Mazzaferri EL. 2010. Thyroid cancer epidemiology and prognostic variables. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 22:395–404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pellegriti G, Frasca F, Regalbuto C, Squatrito S, Vigneri R. 2013. Worldwide increasing incidence of thyroid cancer: update on epidemiology and risk factors. J Cancer Epidemiol 2013:965212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Davies L, Welch HG. 2014. Current thyroid cancer trends in the United States. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 140:317–322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sosa JA, Hanna JW, Robinson KA, Lanman RB. 2013. Increases in thyroid nodule fine-needle aspirations, operations, and diagnoses of thyroid cancer in the United States. Surgery 154:1420–1426; discussion 1426–1427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Faquin WC, Bongiovanni M, Sadow PM. 2011. Update in thyroid fine needle aspiration. Endocr Pathol 22:178–183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haugen BRM, Alexander EK, Bible KC, Doherty G, Mandel SJ, Nikiforov YE, Pacini F, Randolph G, Sawka A, Schlumberger M, Schuff KG, Sherman SI, Sosa JA, Steward D, Tuttle RMM, Wartofsky L. 2016. 2015 American Thyroid Association management guidelines for adult patients with thyroid nodules and differentiated thyroid cancer. Thyroid 26:1–133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nishino M. 2016. Molecular cytopathology for thyroid nodules: a review of methodology and test performance. Cancer Cytopathol 124:14–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nikiforova MN, Wald AI, Roy S, Durso MB, Nikiforov YE. 2013. Targeted next-generation sequencing panel (ThyroSeq) for detection of mutations in thyroid cancer. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 98:E1852–1860 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bar D, Yanai GL, Goren Y, Shtabsky A, Zubkov A, Morgenstern S, Strenov Y, Feinmesser M, Kravtsov V, Leon ME, Granstrem O, Vorobyov S, Hajdúch M, VandenBusshce C, Ashkenaz K, Sanden M, Mitchell H, Noller M, Dromi N, Tabak S, Kadosh E, Meiri E. 2015. MicroRNA-based diagnostic assay for accurate thyroid nodule classification. Presented at the 15th International Thyroid Congress (ITC) and 85th Annual Meeting of the American Thyroid Association (ATA), Orlando, FL [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alexander EK, Kennedy GC, Baloch ZW, Cibas ES, Chudova D, Diggans J, Friedman L, Kloos RT, LiVolsi VA, Mandel SJ, Raab SS, Rosai J, Steward DL, Walsh PS, Wilde JI, Zeiger MA, Lanman RB, Haugen BR. 2012. Preoperative diagnosis of benign thyroid nodules with indeterminate cytology. New Engl J Med 367:705–715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chudova D, Wilde JI, Wang ET, Wang H, Rabbee N, Egidio CM, Reynolds J, Tom E, Pagan M, Rigl CT, Friedman L, Wang CC, Lanman RB, Zeiger M, Kebebew E, Rosai J, Fellegara G, LiVolsi VA, Kennedy GC. 2010. Molecular classification of thyroid nodules using high-dimensionality genomic data. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 95:5296–5304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wylie D, Beaudenon-Huibregtse S, Haynes BC, Giordano TJ, Labourier E. 2016. Molecular classification of thyroid lesions by combined testing for miRNA gene expression and somatic gene alterations. J Pathol Clin Rese 2:93–103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Labourier E, Shifrin A, Busseniers AE, Lupo MA, Manganelli ML, Andruss B, Wylie D, Beaudenon-Huibregtse S. 2015. Molecular testing for miRNA, mRNA, and DNA on fine-needle aspiration improves the preoperative diagnosis of thyroid nodules with indeterminate cytology. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 100:2743–2750 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nikiforov YE, Carty SE, Chiosea SI, Coyne C, Duvvuri U, Ferris RL, Gooding WE, Hodak SP, LeBeau SO, Ohori NP, Seethala RR, Tublin ME, Yip L, Nikiforova MN. 2014. Highly accurate diagnosis of cancer in thyroid nodules with follicular neoplasm/suspicious for a follicular neoplasm cytology by ThyroSeq v2 next-generation sequencing assay. Cancer 120:3627–3634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Labourier E. 2016. Utility and cost-effectiveness of molecular testing in thyroid nodules with indeterminate cytology. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 85:624–631 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lemeshow S, Hosmer DW, Jr, Klar J, and Lwanga SK. 1990. Adequacy of Sample Size in Health Studies. John Wiley, Chichester, United Kingdom [Google Scholar]

- 17.McLachlan G. 2004. Discriminant Analysis and Statistical Pattern Recognition. John Wiley, Chichester, United Kingdom [Google Scholar]

- 18.Melo F, Sali A. 2007. Fold assessment for comparative protein structure modeling. Protein Sci 16:2412–2426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bustin SA, Benes V, Garson JA, Hellemans J, Huggett J, Kubista M, Mueller R, Nolan T, Pfaffl MW, Shipley GL, Vandesompele J, Wittwer CT. 2009. The MIQE guidelines: minimum information for publication of quantitative real-time PCR experiments. Clin Chemi 55:611–622 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pfaffl MW. 2001. A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Res 29:e45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nikiforov YE, Carty SE, Chiosea SI, Coyne C, Duvvuri U, Ferris RL, Gooding WE, LeBeau SO, Ohori NP, Seethala RR, Tublin ME, Yip L, Nikiforova MN. 2015. Impact of the multi-gene ThyroSeq next-generation sequencing assay on cancer diagnosis in thyroid nodules with atypia of undetermined significance/follicular lesion of undetermined significance cytology. Thyroid 25:1217–1223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Najafzadeh M, Marra CA, Lynd LD, Wiseman SM. 2012. Cost-effectiveness of using a molecular diagnostic test to improve preoperative diagnosis of thyroid cancer. Value Health 15:1005–1013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Guhanandam H, Rajamani R, Noorunnisa N, Durairaj M. 2016. Expression of cytokeratin-19 and thyroperoxidase in relation to morphological features in non-neoplastic and neoplastic lesions of thyroid. J Clin Diagn Res 10:EC01–03 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ma H, Xu S, Yan J, Zhang C, Qin S, Wang X, Li N. 2014. The value of tumor markers in the diagnosis of papillary thyroid carcinoma alone and in combination. Polish J Pathol 65:202–209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mathur A, Weng J, Moses W, Steinberg SM, Rahbari R, Kitano M, Khanafshar E, Ljung BM, Duh QY, Clark OH, Kebebew E. 2010. A prospective study evaluating the accuracy of using combined clinical factors and candidate diagnostic markers to refine the accuracy of thyroid fine needle aspiration biopsy. Surgery 148:1170–1176; discussion 1176–1177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gomez-Rueda H, Palacios-Corona R, Gutierrez-Hermosillo H, Trevino V. 2016. A robust biomarker of differential correlations improves the diagnosis of cytologically indeterminate thyroid cancers. Int J Mol Med 37:1355–1362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tomei S, Marchetti I, Zavaglia K, Lessi F, Apollo A, Aretini P, Di Coscio G, Bevilacqua G, Mazzanti C. 2012. A molecular computational model improves the preoperative diagnosis of thyroid nodules. BMC Cancer 12:396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Denkert C, Kronenwett R, Schlake W, Bohmann K, Penzel R, Weber KE, Hofler H, Lehmann U, Schirmacher P, Specht K, Rudas M, Kreipe HH, Schraml P, Schlake G, Bago-Horvath Z, Tiecke F, Varga Z, Moch H, Schmidt M, Prinzler J, Kerjaschki D, Sinn BV, Muller BM, Filipits M, Petry C, Dietel M. 2012. Decentral gene expression analysis for ER+/Her2– breast cancer: results of a proficiency testing program for the EndoPredict assay. Virchows Arch 460:251–259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kronenwett R, Bohmann K, Prinzler J, Sinn BV, Haufe F, Roth C, Averdick M, Ropers T, Windbergs C, Brase JC, Weber KE, Fisch K, Muller BM, Schmidt M, Filipits M, Dubsky P, Petry C, Dietel M, Denkert C. 2012. Decentral gene expression analysis: analytical validation of the Endopredict genomic multianalyte breast cancer prognosis test. BMC Cancer 12:456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reed MJ, Sperry SM, Gailey MP, Jensen CS, Robinson RA, Funk GF, Pagedar NA. 2016. Correlating thyroid cytology and histopathology: implications for molecular testing. Head Neck 38:1104–1106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Valderrabano P, Leon ME, Centeno BA, Otto KJ, Khazai L, McCaffrey JC, Russell JS, McIver B. 2016. Institutional prevalence of malignancy of indeterminate thyroid cytology is necessary but insufficient to accurately interpret molecular marker tests. Eur J Endocrinol 174:621–629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nikiforov YE, Seethala RR, Tallini G, Baloch ZW, Basolo F, Thompson LD, Barletta JA, Wenig BM, Al Ghuzlan A, Kakudo K, Giordano TJ, Alves VA, Khanafshar E, Asa SL, El-Naggar AK, Gooding WE, Hodak SP, Lloyd RV, Maytal G, Mete O, Nikiforova MN, Nose V, Papotti M, Poller DN, Sadow PM, Tischler AS, Tuttle RM, Wall KB, LiVolsi VA, Randolph GW, Ghossein RA. 2016. Nomenclature revision for encapsulated follicular variant of papillary thyroid carcinoma: a paradigm shift to reduce overtreatment of indolent tumors. JAMA Oncol 2:1023–1029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.