Abstract

Aims: Cigarette smoke (CS)-mediated acquired cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR)-dysfunction, autophagy-impairment, and resulting inflammatory–oxidative/nitrosative stress leads to chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)-emphysema pathogenesis. Moreover, nitric oxide (NO) signaling regulates lung function decline, and low serum NO levels that correlates with COPD severity. Hence, we aim to evaluate here the effects and mechanism(s) of S-nitrosoglutathione (GSNO) augmentation in regulating inflammatory-oxidative stress and COPD-emphysema pathogenesis.

Results: Our data shows that cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) colocalizes with aggresome bodies in the lungs of COPD subjects with increasing emphysema severity (Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease [GOLD] I − IV) compared to nonemphysema controls (GOLD 0). We further demonstrate that treatment with GSNO or S-nitrosoglutathione reductase (GSNOR)-inhibitor (N6022) significantly inhibits cigarette smoke extract (CSE; 5%)-induced decrease in membrane CFTR expression by rescuing it from ubiquitin (Ub)-positive aggresome bodies (p < 0.05). Moreover, GSNO restoration significantly (p < 0.05) decreases CSE-induced reactive oxygen species (ROS) activation and autophagy impairment (decreased accumulation of ubiquitinated proteins in the insoluble protein fractions and restoration of autophagy flux). In addition, GSNO augmentation inhibits protein misfolding as CSE-induced colocalization of ubiquitinated proteins and LC3B (in autophagy bodies) is significantly reduced by GSNO/N6022 treatment. We verified using the preclinical COPD-emphysema murine model that chronic CS (Ch-CS)-induced inflammation (interleukin [IL]-6/IL-1β levels), aggresome formation (perinuclear coexpression/colocalization of ubiquitinated proteins [Ub] and p62 [impaired autophagy marker], and CFTR), oxidative/nitrosative stress (p-Nrf2, inducible nitric oxide synthase [iNOS], and 3-nitrotyrosine expression), apoptosis (caspase-3/7 activity), and alveolar airspace enlargement (Lm) are significantly (p < 0.05) alleviated by augmenting airway GSNO levels. As a proof of concept, we demonstrate that GSNO augmentation suppresses Ch-CS-induced perinuclear CFTR protein accumulation (p < 0.05), which restores both acquired CFTR dysfunction and autophagy impairment, seen in COPD-emphysema subjects.

Innovation: GSNO augmentation alleviates CS-induced acquired CFTR dysfunction and resulting autophagy impairment.

Conclusion: Overall, we found that augmenting GSNO levels controls COPD-emphysema pathogenesis by reducing CS-induced acquired CFTR dysfunction and resulting autophagy impairment and chronic inflammatory–oxidative stress. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 27, 433–451.

Keywords: : CFTR, COPD, emphysema, GSNO, GSNOR, NO

Introduction

Chronic inflammation and unabated oxidative/nitrosative stress are important mediators of cigarette smoke (CS)-induced chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)-emphysema pathogenesis (4, 35, 62). The overactivation of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species (ROS/RNS) causes dysregulation of several key cellular homeostasis mechanisms, including autophagy that has been recently shown to be impaired in COPD-emphysema and cystic fibrosis (CF) subjects (10, 38, 64). Under normal conditions, lung function is maintained by the bioavailable nitric oxide (NO) and S-nitrosoglutathione (GSNO), which is a member of the S-nitrosothiols (SNOs) group of bioactive NO reservoirs (13, 63). In the lung, NO signaling is crucial for maintaining normal airway smooth muscle tone and keeping inflammation in check (63). Hence, intracellular levels of GSNO are tightly regulated by S-nitrosoglutathione reductase (GSNOR), an enzyme that degrades GSNO (51, 63). Altered expression of GSNOR is reported in a variety of disease conditions such as those involving cardiopulmonary and gastrointestinal systems (26, 41, 51, 63). In asthma subjects, the low GSNO/NO levels are attributed to elevated GSNOR activity that induces GSNO catabolism, hampering GSNO/NO-mediated bronchodilatory and anti-inflammatory functions (6, 51). Moreover, current smokers and severe COPD subjects also demonstrate low NO levels, where increased levels of serum asymmetric dimethylarginine (ADMA) are described as the cause of this imbalance (1). The low NO and high ADMA levels also correlate with the severity of airflow obstruction in COPD subjects, thus highlighting the importance of NO signaling in COPD-emphysema pathogenesis (1). The low NO levels in current smokers and severe COPD patients involve CS-induced and ROS/RNS-mediated peroxynitrite formation, as ex-smokers demonstrate an elevated fraction of exhaled nitric oxide (FeNO), compared to current smokers with COPD (37, 60). It is important to note that FeNO is substantially low in current smokers with COPD (42). Thus, in contrast to asthma (58), FeNO levels are not a reliable marker for predicting COPD lung disease state. Nonetheless, changes in GSNO/NO levels are shown to modulate autophagy and disease causing processes in COPD-emphysema subjects, but mechanisms are unknown.

Innovation.

Cigarette smoke (CS)-induced acquired cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) dysfunction results in autophagy impairment and inflammatory–oxidative stress that mediates chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)-emphysema pathogenesis, but underlying mechanisms are still unclear. Our study identifies CS-induced accumulation of CFTR in perinuclear aggresome bodies as a novel causal mechanism of acquired CFTR dysfunction. Moreover, our data demonstrate the potential of S-nitrosoglutathione (GSNO) augmentation strategy for COPD-emphysema as it controls CS-induced acquired CFTR dysfunction, autophagy impairment, and inflammatory–oxidative stress.

We have recently demonstrated the crucial role of inflammatory–oxidative stress and the resulting autophagy impairment in tobacco smoke-induced COPD-emphysema pathogenesis (9–11, 43, 61). Moreover, CS exposure also leads to a significant decrease in cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) protein expression (7), and accumulation of CFTR protein in the aggresome bodies (as shown in this study), which correlates with COPD-emphysema severity (10, 64, 65). A recent study shows that CFTR also regulates autophagy responses, as loss of CFTR due to ΔF508-CFTR misfolding leads to ROS-mediated autophagy impairment (38). Interestingly, GSNO is known to regulate the expression, maturation, and function of CFTR protein (17, 71). In fact, CF-patients have reduced GSNO levels and augmenting GSNO levels is a promising therapeutic strategy currently being developed for treating obstructive CF-lung disease (71). The therapeutic benefits of GSNO are evident from the fact that nearly 20 clinical trials have investigated its potency in multiple disease states (13). In recent years, an alternate mechanism of GSNO induction via pharmacological inhibition of the enzyme, GSNOR, has shown therapeutic potential in controlling chronic inflammatory and obstructive lung disease states, such as asthma and CF (51, 63, 71). Out of the several inhibitors tested, the drug of choice is N6022, a potent reversible inhibitor of GSNOR (27, 63). Treatment with N6022 reduces key asthma symptoms in ovalbumin-induced animal models by virtue of its anti-inflammatory, bronchodilatory, and smooth muscle relaxant properties (6). Also, N6022 shows promising therapeutic efficacy and safety profile in animal models of dextran sulfate sodium-induced inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and a rat model of salt-induced hypertension (19, 27, 63).

The exact role of GSNO in regulating autophagy is still unclear with some reports suggesting its autophagy-inducing potential (44). Thus, the present study was designed to evaluate the impact of GSNO supplementation in regulating CS-induced acquired CFTR dysfunction and the ensuing autophagy responses that regulate chronic inflammatory–oxidative stress in the airways. We hypothesize that GSNO augmentation, either by direct administration of GSNO or treatment with GSNOR inhibitor (N6022), will be therapeutically beneficial for COPD-emphysema subjects due to its ability to increase CFTR maturation/expression by facilitating its rescue from aggresome bodies as a potential mechanism for controlling CS-induced autophagy impairment, chronic inflammatory–oxidative stress, and emphysema progression.

Results

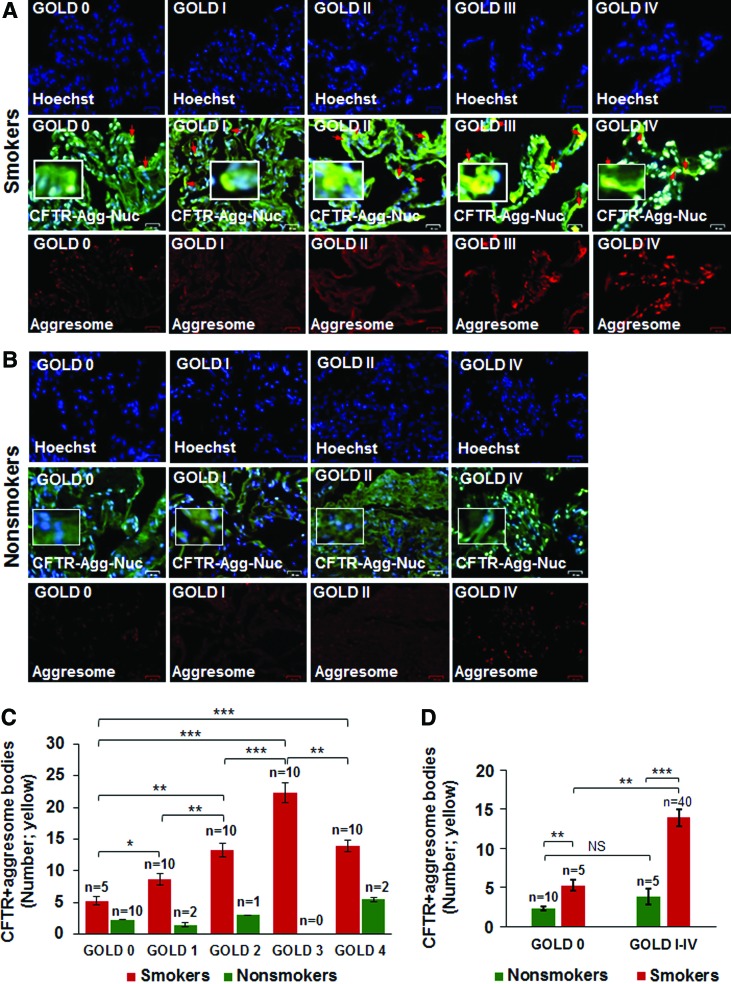

CFTR colocalizes with aggresome bodies in human lung tissues with increasing severity of emphysema

Previous reports from our group have shown that expression of membrane-localized CFTR protein decreases, while the number of aggresome bodies increases in the lungs of COPD subjects with increasing emphysema severity (Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease [GOLD] I − IV) compared to nonemphysema controls (GOLD 0) (7, 10, 64). We wanted to evaluate whether misfolded-CFTR itself localizes in aggresome bodies as a mechanism of reduced CFTR function (acquired CFTR dysfunction) observed in COPD subjects (24). We found a significant increase in CFTR colocalization within perinuclear aggresome bodies with increasing emphysema severity (Fig. 1A, C, from GOLD 0 to GOLD III, r = −0.88; red arrows: perinuclear CFTR accumulation). Although we observed an increase in CFTR aggresome colocalization in very severe emphysema subjects (GOLD IV) compared to nonemphysema (GOLD 0) and mild emphysema (GOLD I) subjects, the total expression in GOLD IV subjects decreased when compared to GOLD III subjects, as anticipated, due to substantial tissue destruction. Next, we demonstrate that smokers (GOLD 0 or GOLD I − IV) show a significant increase in perinuclear CFTR aggresome colocalization compared to nonsmokers (Fig. 1A−D, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001). Moreover, the smokers with a greater disease severity (GOLD I − IV) show a comparatively higher increase in CFTR aggresome colocalization compared to GOLD 0 nonemphysema subjects (Fig. 1D, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001). Thus, our data suggests that perinuclear accumulation of CFTR into aggresome bodies in smokers and COPD-emphysema subjects serves as a mechanism for acquired CFTR-dysfunction seen in COPD patients (24). Therefore, we next utilized the in vitro and preclinical models of CS-induced COPD-emphysema to verify if rescuing aggresome-localized CFTR could ameliorate CS-induced autophagy impairment, chronic inflammatory–oxidative stress, and resulting lung tissue damage.

FIG. 1.

Increased colocalization of CFTR with aggresome bodies in human lung tissues with increasing emphysema severity. (A, B) The paraffin-embedded longitudinal lung tissue sections from nonemphysema (GOLD 0) and emphysema (GOLD I − IV), smokers and nonsmoker subjects were costained with aggresome-specific dye [red, bottom panel of (A, B)], CFTR (green), and Hoechst dye (nucleus, blue). The merged images (scale bar, 25 μm) were used to count the number of CFTR-positive aggresome bodies (yellow) in the perinuclear region depicted by red arrows, and high-magnification images are shown as insets. (C) The data indicate a significant statistical correlation between increased CFTR aggresome colocalization with decreasing lung function (FEV-1% predicted) and increasing severity of emphysema (GOLD I − IV) compared to nonemphysema (GOLD 0) control subjects [mean ± SEM, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, r = −0.88; “n” numbers shown in (C)]. (D) The graph indicates a significant increase in CFTR aggresome colocalization in smokers (GOLD 0 and GOLD I − IV) compared to nonsmokers (GOLD 0 or GOLD I − IV). Also, smokers with greater emphysema severity (from GOLD I − IV) demonstrate a higher increase in CFTR aggresome colocalization compared to GOLD 0 smoker subjects, verifying that aggresome localization of CFTR is directly correlated to COPD-emphysema pathogenesis. Scale bar, 25 μM, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. CFTR, cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; GOLD, Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease; SEM, standard error of the mean. To see this illustration in color, the reader is referred to the web version of this article at www.liebertpub.com/ars

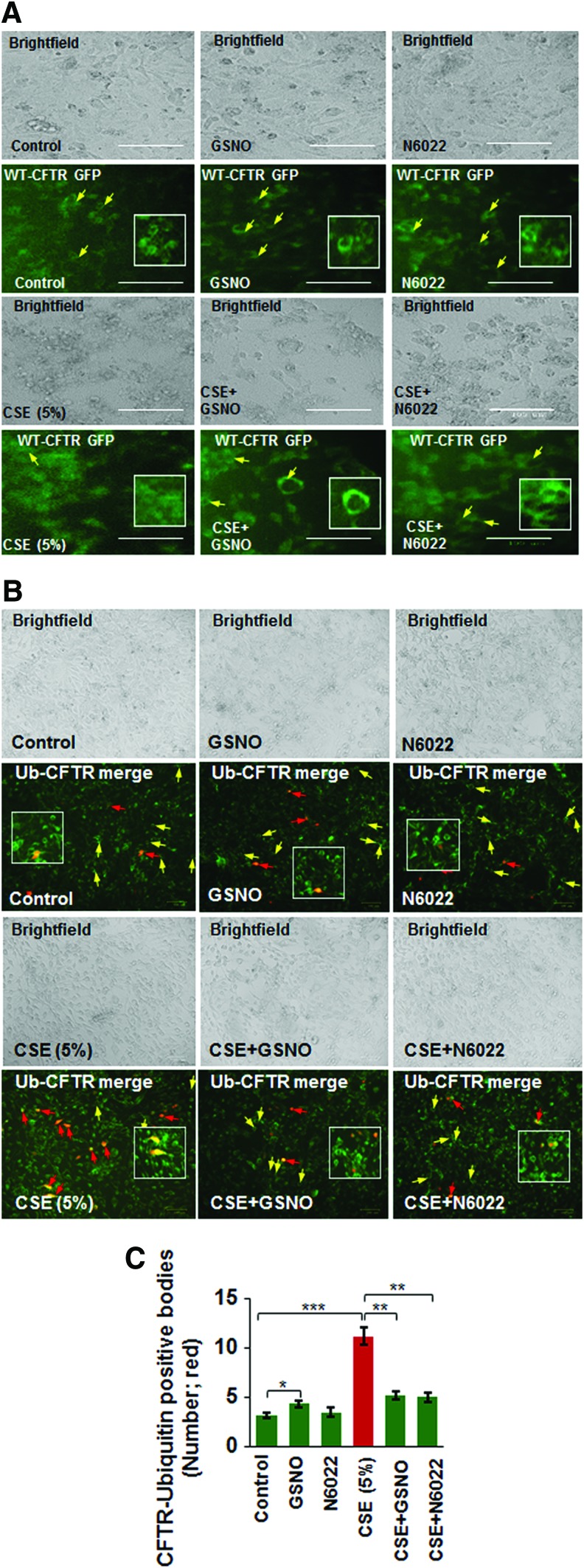

Augmenting GSNO levels restores cigarette smoke extract-induced decrease in membrane CFTR by rescuing it from aggresome bodies

Apart from its known anti-inflammatory properties (21, 63), GSNO has been recently shown to be beneficial in CF lung disease by virtue of its potential to rescue misfolded CFTR to the plasma membrane (69). Since misfolded/defective CFTR promotes aggresome formation (38) and our current human data (Fig. 1) shows that CFTR colocalizes with aggresome bodies with increasing severity of emphysema, we aimed to evaluate if aggresome-localized CFTR is rescued by augmenting intracellular GSNO levels. We demonstrate here that GSNO augmentation using GSNO or GSNOR inhibitor (N6022) rescues the cigarette smoke extract (CSE)-induced decrease in membrane CFTR (Fig. 2A) by significantly inhibiting its aggresome localization (CFTR ubiquitin [Ub]-positive bodies, yellow, red arrows; Fig. 2B, C, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001). The data imply that restoring GSNO levels corrects CS-induced acquired CFTR dysfunction, suggesting its potential in improving COPD-emphysema-related pathologies.

FIG. 2.

CSE-induced decrease in membrane CFTR and its aggresome accumulation is restored by augmenting GSNO levels. (A) Beas2b cells were transiently transfected with WT-CFTR GFP plasmid (24 h) and treated with 5% CSE and/or GSNO/N6022 (10 μM) for 12 h. The expression of WT-CFTR was analyzed by fluorescence microscopy, while the cell morphology and numbers are depicted using brightfield images of the same areas. The data shows that CSE-induced decrease in membrane CFTR expression is reinstated by GSNO augmentation (yellow arrows and insets, scale bar: 100 μm). (B, C) The WT-CFTR GFP and Ub-RFP plasmids were used to transiently transfect Beas2b cells for 24 h and cells were treated with 5% CSE and/or GSNO/N6022 (10 μM) for 12 h. Fluorescence and brightfield images were captured and the number of cells positive for both Ub (red) and WT-CFTR (green) were counted (yellow, red arrows), indicative of WT-CFTR accumulation in aggresomes. The data indicate that GSNO augmentation significantly reduces the CSE-induced increase in aggresome accumulation of WT-CFTR (red arrows) and enhances membrane WT-CFTR expression (yellow arrows) that was diminished by CSE treatment (mean ± SEM; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, scale bar: 100 μm). The inset shows an enlarged selected area to better visualize the membrane expression of WT-CFTR and its colocalization with Ub. CSE, cigarette smoke extract; GFP, green fluorescent protein; GSNO, S-nitrosoglutathione; RFP, red fluorescent protein; Ub, ubiquitin; WT-CFTR, wild-type cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator. To see this illustration in color, the reader is referred to the web version of this article at www.liebertpub.com/ars

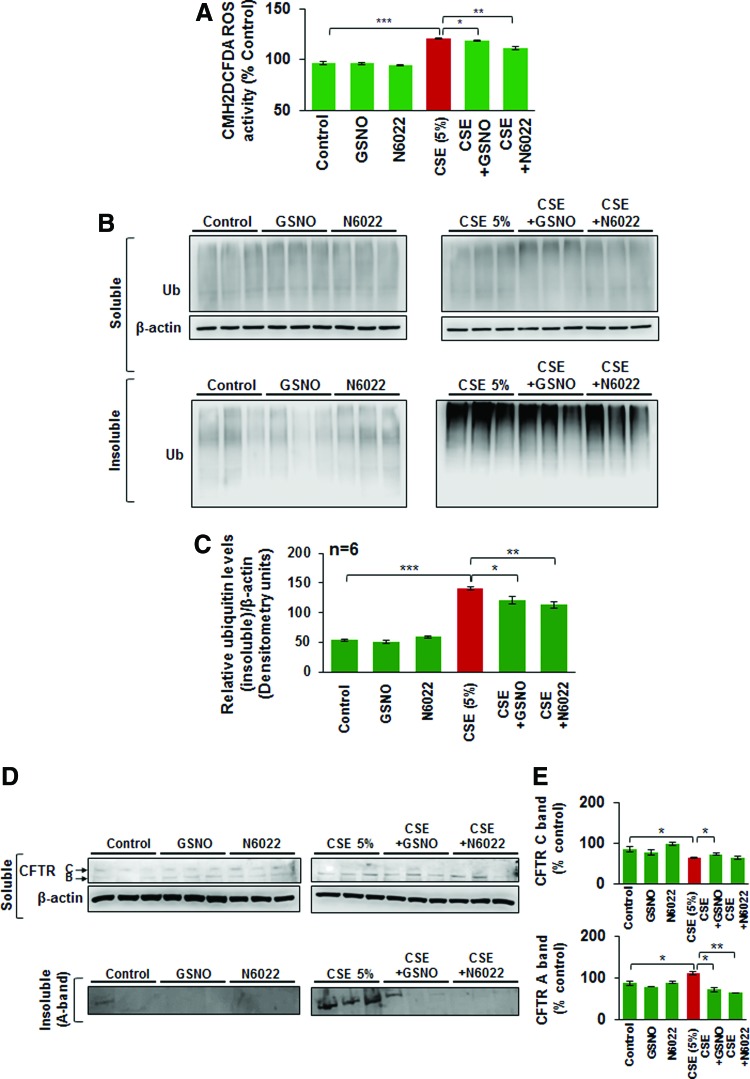

CSE-induced ROS activation and resulting autophagy impairment are alleviated by restoring intracellular GSNO levels

Exposure to CS leads to ROS-mediated oxidative stress that is known to inhibit autophagy mechanisms (36, 38, 39, 55) that play a crucial role in COPD-emphysema pathogenesis. Thus, we tested the effects of restoring GSNO levels as an antioxidant strategy, in controlling CSE-induced ROS activation. Our data show that CSE (5%)-induced ROS activation in Beas2b cells is significantly reduced by restoring GSNO levels using GSNO or GSNOR inhibitor (N6022) (Fig. 3A, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001). We have recently shown that tobacco smoke or e-cigarette vapor (eCV) induced ROS activity that initiates autophagy impairment and COPD-emphysema pathogenesis (11, 61). Moreover, treatment with cysteamine (CYS), an antioxidant drug with autophagy-inducing properties, controls tobacco smoke/eCV-mediated inflammatory–oxidative stress and development of COPD-emphysema-like pathologies (10, 11). Here, we demonstrate that restoring GSNO levels by using GSNO or GSNOR inhibitor, N6022, controls CSE-induced autophagy impairment in Beas2b cells, as seen by a significant decrease in CSE-induced accumulation of ubiquitinated proteins in the insoluble protein fractions (Fig. 3B, C, and Supplementary Fig. S1 [Supplementary Data are available online at www.liebertpub.com/ars], *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001). Moreover, we also found that CSE-induced decrease in mature wild-type cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (WT-CFTR; C-band) is partially restored by GSNO augmentation, while the increase in aggresome CFTR (A band) is significantly diminished (Fig. 3D, E, and Supplementary Fig. S2, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01), thus validating our microscopy data in Figure 2. These data suggest that restoring GSNO levels controls CS-induced oxidative stress and autophagy impairment that would provide therapeutic benefits in COPD-emphysema. Moreover, this observation also verifies other reports showing that GSNO augmentation may have a positive effect on autophagy (44).

FIG. 3.

Restoring GSNO levels reduces CSE-induced ROS activation and autophagy impairment. (A) Beas2b cells were treated with 5% CSE and/or GSNO/N6022 (10 μM) for 12 h and CM-DCFDA ROS indicator dye was added for last 30 min to quantify changes in ROS activity. The data shows that CSE-induced ROS activation is significantly alleviated by treatment with GSNO or N6022 (mean ± SEM, n = 3, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001). (B, C) Western blot showing changes in accumulation of ubiquitinated proteins in the soluble and insoluble protein lysates isolated from Beas2b cells treated with 5% CSE and/or GSNO/N6022 (10 μM) for 12 h. The data indicate that CSE-mediated increase in accumulation of ubiquitinated proteins in the insoluble protein fractions (aggresomes) is significantly decreased by treatment with GSNO or N6022. Data represent mean ± SEM of six replicates (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001). β-actin was used as the loading control. (D, E) Beas2b cells were transiently transfected with WT-CFTR and treated with 5% CSE and/or GSNO/N6022 (10 μM) for 12 h. Western blot showing that augmenting GSNO elevates the CSE-induced decrease in mature CFTR (C-band), while significantly rescuing the CFTR protein accumulation in the aggresomes (A-band). Data analysis is shown as mean ± SEM of three replicates (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01). These results demonstrate that augmentation of GSNO levels, either directly using GSNO or by inhibiting GSNOR can control CSE-induced oxidative stress and autophagy impairment by rescuing CFTR protein from aggresomes. GSNOR, S-nitrosoglutathione reductase; ROS, reactive oxygen species. To see this illustration in color, the reader is referred to the web version of this article at www.liebertpub.com/ars

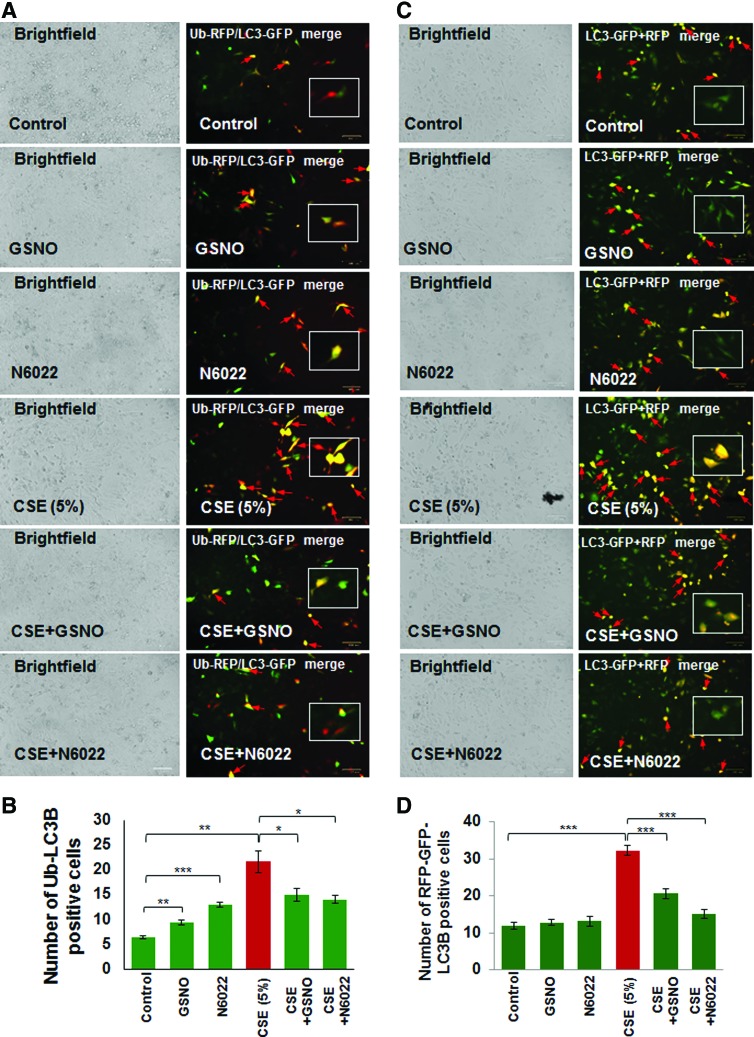

Autophagy inhibition can be quantified by counting the number of cells showing colocalization of ubiquitinated proteins (Ub) and LC3B as previously described (10, 11, 61). Here we report that CSE-induced elevation in Ub-LC3B colocalization (aggresome formation, red arrows) is significantly (p < 0.05) inhibited by restoring intracellular GSNO levels using GSNO or GSNOR inhibitor (N6022) treatment (Fig. 4A, B, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001). Moreover, we also found that CSE induces green fluorescent protein (GFP)/red fluorescent protein (RFP)-positive autophagosomes (yellow puncta bodies, red arrows), indicative of impaired autophagy flux, which is restored by GSNO augmentation using GSNO or GSNOR inhibitor (N6022) treatment (Fig. 4C, D, ***p < 0.001). Thus, our data help to clarify the contrasting reports regarding the effect of GSNO on autophagy and confirm that GSNO induces autophagy as it protects from CSE-induced autophagy impairment.

FIG. 4.

GSNO or GSNOR inhibitor (N6022) treatment restores CSE-impaired autophagy. (A) Beas2b cells were transiently cotransfected with Ub-RFP and LC3B-GFP, the autophagy protein light chain-3 plasmids. After 24 h of transfection, cells were treated with CSE (5%), GSNO, and/or N6022 (10 μM) for 12 h and fluorescence images were captured. The images were used to count the number of cells positive for ubiquitinated protein accumulation (red), LC3B-containing puncta-bodies (green) and/or their colocalization (yellow, insets). Scale bar, 100 μm. (B) Data analysis is shown as mean ± SEM of three replicates (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001). The results demonstrate that enhancing GSNO levels by GSNO or N6022 treatment controls CSE-induced aggresome formation (Ub-LC3B positive, yellow) potentially via inhibition of ROS activity. (C) Beas2b cells were incubated with BacMam reagent (with Premo™ Autophagy Tandem Sensor RFP-GFP-LC3B) for 16 h followed by treatment with CSE (5%), GSNO, and/or N6022 (10 μM) for 12 h followed by fluorescence microscopy-based analysis to quantify changes in autophagy flux. The data are shown as mean ± SEM of eight replicates (***p < 0.001) and indicate that CSE-impaired autophagy flux (formation of GFP/RFP-positive autophagosomes, yellow, insets) can be restored by augmenting GSNO levels, using GSNO or N6022 treatment. To see this illustration in color, the reader is referred to the web version of this article at www.liebertpub.com/ars

Elevated membrane CFTR expression/function corrects CSE-induced autophagy impairment

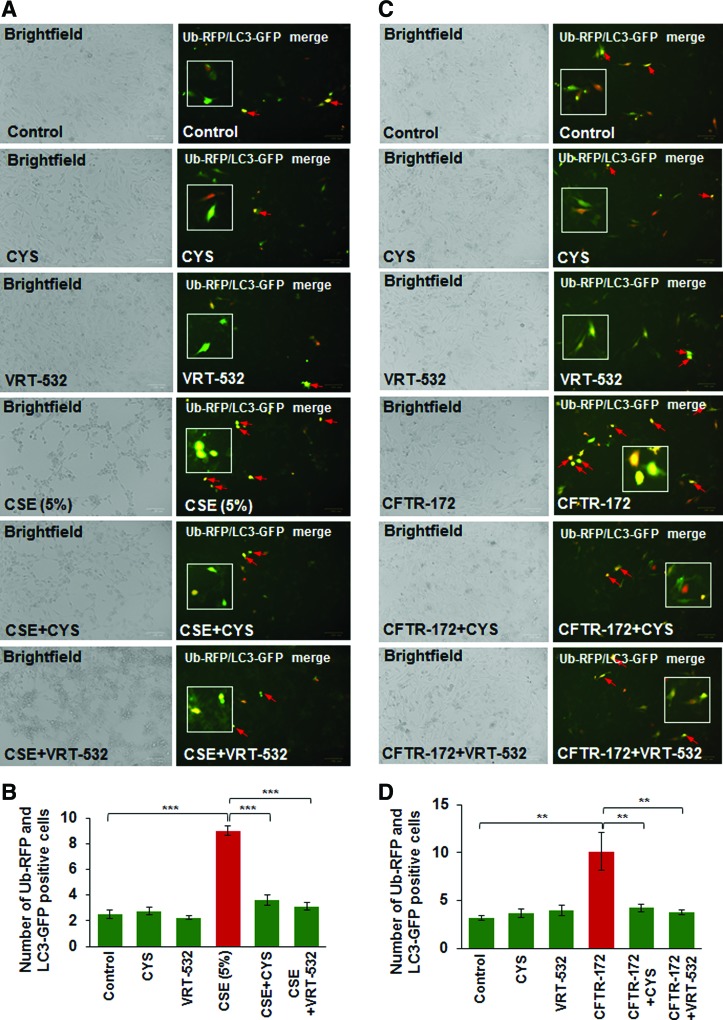

We and others have shown that diminished levels of membrane-localized mature CFTR protein, due to genetic causes (as in CF) or CS-mediated acquired CFTR-dysfunction, leads to autophagy impairment (8, 38). In this study, we further verified the mechanistic role of CFTR in regulating autophagy responses and demonstrate that CSE induces colocalization of Ub-RFP and LC3B-GFP (yellow, red arrows), indicative of protein misfolding and aggresome formation, which is significantly decreased by treatment with either CYS [an antioxidant drug known to promote membrane trafficking/localization of ΔF508-CFTR protein (23) or VRT-532, a known corrector potentiator of mutant CFTR protein (46) [Fig. 5A, B, ***p < 0.001]). Next, we exposed Beas2b cells to CFTR inhibitor-172 to investigate the specificity of functional CFTR protein in regulating autophagy responses. We observed a significant increase in Ub-RFP and LC3B-GFP colocalization, which was diminished by either CYS or VRT-532 treatment (Fig. 5C, D, **p < 0.01), confirming that CFTR dysfunction leads to autophagy impairment (38). We have recently shown that CS-induced perinuclear accumulation of transcription factor-EB (TFEB), the master regulator of autophagy, into aggresome bodies mediates COPD-emphysema pathogenesis (10). Here we report that treatment of Beas2b cells with CFTR inhibitor-172 leads to increased perinuclear accumulation of TFEB and p62 (impaired autophagy marker) that was significantly rescued by VRT-532 (Supplementary Fig. S3, ***p < 0.001), suggesting the potential mechanism by which CFTR may regulate key autophagy pathways. Thus, we predicted that restoration of CSE-mediated decrease in membrane CFTR expression by GSNO treatment can similarly alleviate autophagy impairment.

FIG. 5.

Modulating CFTR membrane expression/function restores autophagy. (A) Beas2b cells were transiently cotransfected with Ub-RFP and LC3B-GFP, the autophagy protein light chain-3 plasmids. Twenty-four hours after transfection, the cells were treated with CSE (5%), CYS (250 μM), and/or VRT-532 (10 μM) for 12 h and fluorescence images were captured. These images were used to count the number of cells positive for ubiquitinated protein accumulation (red), LC3B-containing puncta-bodies (green), and/or their colocalization (yellow, insets). Scale bar, 100 μm. (B) Data analysis is shown as mean ± SEM of eight replicates (***p < 0.001) and indicate that CSE-induced aggresome formation can be controlled by treatment with either CYS, an antioxidant drug with autophagy-inducing properties, or a CFTR corrector- potentiator drug, VRT-532. (C) The Beas2b cells were transiently cotransfected with Ub-RFP and LC3B-GFP as described above in (A), and treated with CFTR-172 (10 μM), CYS (250 μM), and/or VRT-532 (10 μM) for 12 h followed by fluorescence microscopy to detect Ub-LC3B-positive puncta-bodies (yellow, insets, scale bar, 100 μm). The analysis of the data shown in (D) (mean ± SEM of eight replicates, **p < 0.01) implies that inhibition of CFTR function leads to aggresome formation that can be reduced by treatment with either CYS, an antioxidant drug with autophagy-inducing properties, or a CFTR corrector-potentiator drug, VRT-532. CYS, cysteamine. To see this illustration in color, the reader is referred to the web version of this article at www.liebertpub.com/ars

Chronic cigarette smoke-induced autophagy impairment is alleviated by augmenting intracellular GSNO levels

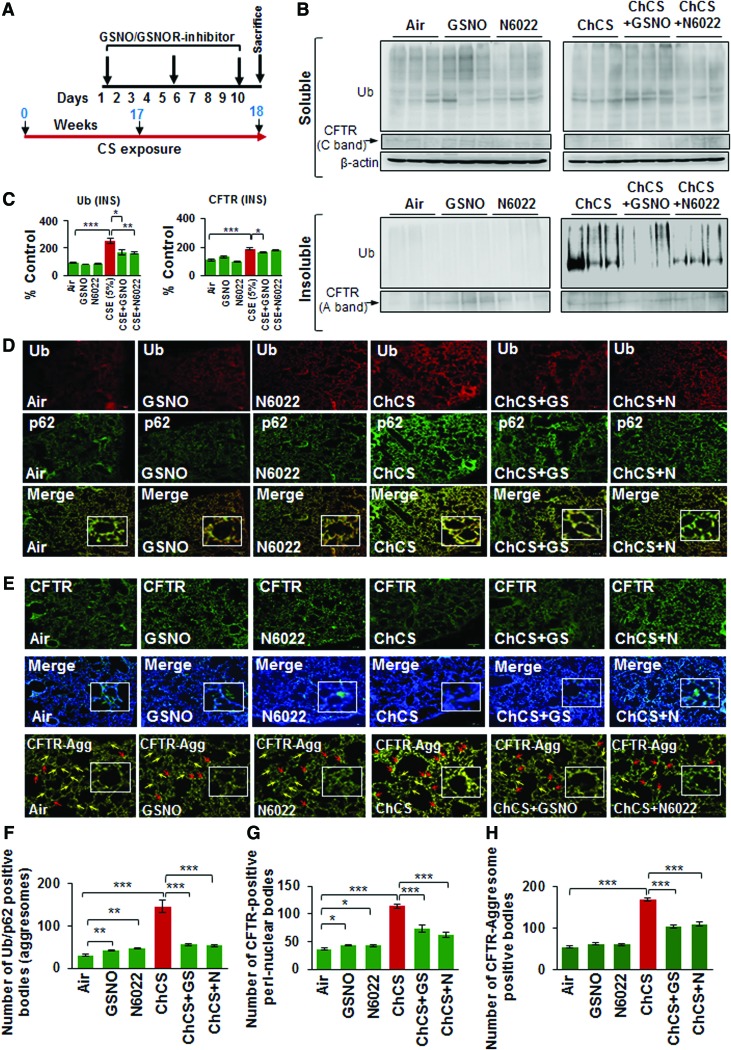

Chronic cigarette smoke (Ch-CS) exposure causes autophagy impairment that correlates with emphysema in COPD subjects (10, 64). Although we have shown that restoring the CS-impaired autophagy by autophagy-inducing drugs ameliorates chronic obstructive lung disease and emphysema pathogenesis (10, 64), here we tested a novel hypothesis that restoring intracellular GSNO levels could have a positive effect on CS-induced autophagy impairment and emphysema by controlling the acquired CFTR dysfunction. We exposed C57BL/6 mice to side-stream CS for 18 weeks and performed intratracheal treatments with vehicle (phosphate-buffered saline [PBS]), GSNO, or N6022 (GSNOR inhibitor), as indicated by the scale shown in Figure 6A. We observed that GSNO augmentation significantly decreases Ch-CS-induced accumulation of ubiquitinated proteins (Ub) and CFTR (A-band) in the insoluble protein fractions of murine lungs (Fig 6B, C, and Supplementary Fig. S4, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001). We confirmed these findings by immunostaining and show that Ch-CS-induced colocalization of ubiquitinated proteins (Ub) and p62 is significantly diminished by GSNO/GSNOR inhibitor (N6022)-mediated increase in intracellular GSNO levels (Fig 6D, F, and Supplementary Fig. S5, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001). Moreover, GSNO augmentation significantly reduces CS-induced increase in the number of CFTR-positive perinuclear bodies (Fig. 6E, G, and Supplementary Fig. S5, *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001) that are aggresomes (Fig. 6E, bottom panel, and 6H and Supplementary Fig. S5, ***p < 0.001). The exact role of GSNO in regulating autophagy responses is elusive and ours is the first report showing that restoring intracellular GSNO levels controls chronic CS-induced CFTR dysfunction and resulting autophagy impairment.

FIG. 6.

Augmenting intracellular GSNO levels controls Ch-CS-induced autophagy impairment and aggresome formation. (A) Scale depicting the timeline for Ch-CS exposure (18 weeks) and drug treatments (days 1, 5, and 9 before termination) and termination of experiment. (B) Immunoblots showing the levels of ubiquitinated proteins (Ub) and CFTR in the soluble and insoluble protein fractions isolated from murine lung lysates collected from C57BL/6 mice (n = 4) exposed to RA or Ch-CS (18 weeks, 5 h/day, 5 days/week) and/or treated with vehicle control (PBS), GSNO, and/or N6022 [4 mg/kg body weight, i.t., three total doses with a gap of 3 days as shown in (A)]. The changes in expression of protein were normalized to β-actin (loading control) for each experimental group. (C) The data shows that augmenting GSNO intracellular levels significantly controls Ch-CS-induced accumulation of ubiquitinated proteins (Ub) and CFTR in the insoluble protein fractions (aggresomes). The data represent mean ± SEM of three replicates (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001). (D, E) Immunostaining of longitudinal lung sections isolated from C57BL/6 mice exposed to RA or Ch-CS exposure (18 weeks, 5 h/day, 5 days/week) and/or treated with vehicle control (PBS), GSNO, and/or N6022 (4 mg/kg body weight, i.t., three total doses with a gap of 3 days) shows that induction of cellular GSNO levels significantly diminishes the colocalization of ubiquitinated proteins (Ub) and impaired autophagy marker, p62 (yellow, insets, F), and also substantially decreases CS-induced perinuclear (G, CFTR nucleus costaining, insets) aggresome localization of CFTR (CFTR aggresome costaining, red arrows, insets, H). The data imply that restoring GSNO levels rescues CFTR protein (yellow arrows) from perinuclear aggresome bodies as a potential mechanism to control CFTR-dependent autophagy and inflammation in murine lungs of CS-induced COPD-emphysema experimental group (n = 4, mean ± SEM, *p < 0.5, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, scale bar, 100 μm). Ch-CS, chronic cigarette smoke; CS, cigarette smoke; i.t., intratracheal; PBS, phosphate-buffered saline; RA, room air. To see this illustration in color, the reader is referred to the web version of this article at www.liebertpub.com/ars

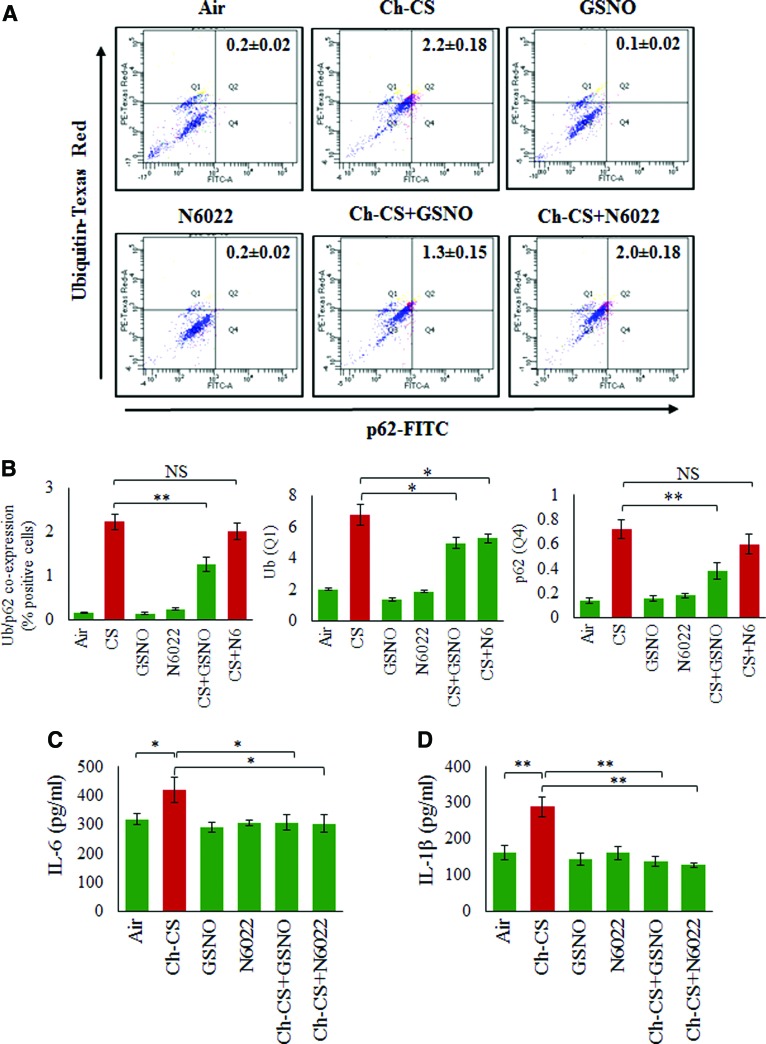

Restoring intracellular GSNO levels mitigates chronic CS-induced aggresome formation and inflammatory response in the airway

We have recently shown that Ch-CS exposure leads to a significant increase in coexpression of ubiquitinated proteins (Ub) and the impaired autophagy marker, p62, in the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) cells, which was controlled by treatment with CYS, an antioxidant drug with autophagy-inducing property (10, 66). In the present study, we report that GSNO augmentation by GSNO or GSNOR inhibitor (N6022) could modulate Ch-CS-induced coexpression of ubiquitinated proteins (Ub) and the impaired autophagy marker, p62, in the BALF-cells (Fig. 7A, B, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01). Specifically, we found that GSNO treatment was more potent in reducing the Ub-p62 coexpression (aggresome bodies), compared to GSNOR inhibitor, at the selected equimolar in vivo doses (4 mg/kg body weight), although both GSNO and GSNOR inhibitor (N6022) were capable of significantly (p < 0.05) reducing the levels of ubiquitinated proteins (Ub). Inhibition of GSNOR showed a trend towards a decrease in p62 protein levels. Since airway inflammation is a crucial mediator of COPD-emphysema pathogeneses (4), we next evaluated the effect of augmenting GSNO levels by GSNO or GSNOR inhibitor (N6022) on changes in the levels of proinflammatory cytokines (interleukin [IL]-6 and IL-1β) in the BALF. An earlier study suggests that treatment with GSNO reduced the expression of inflammatory cytokines and inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) in a rat model of ischemia/reperfusion injury (33). In accord with its known anti-inflammatory property, our results demonstrate that GSNO augmentation significantly decreases the levels of Ch-CS-induced inflammatory cytokines, IL-6 and IL-1β (Fig. 7C, D, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01), while partially reducing the total number of F/480+ macrophages and CD4+ T cells (data not shown). These data demonstrate the protective role of GSNO augmentation strategy in controlling CS-induced inflammation in COPD-emphysema subjects.

FIG. 7.

Chronic CS-induced aggresome formation and inflammation are mitigated by restoring GSNO levels. (A) Flow cytometry analysis of BALF cells isolated from C57BL/6 mice exposed to RA or Ch-CS exposure (18 weeks, 5 h/day, 5 days/week) and/or treated with vehicle control (PBS), GSNO, and/or N6022 (4 mg/kg body weight, i.t., “three” total doses with a gap of 3 days). (B) The data shows that Ch-CS-mediated increase in expression of ubiquitinated proteins (Ub) is significantly reduced by GSNO and GSNOR inhibitor (N6022) treatment, although impaired autophagy marker (p62) is inhibited only by GSNO. Moreover, CS-induced coexpression of Ub-p62 is also significantly inhibited by GSNO but the effect of GSNOR inhibition is not significant. (C, D) ELISA-based analysis of BALF from mice lungs as described in (A) shows that an increase in GSNO (by GSNO or N6022 treatment) significantly decreases the Ch-CS-induced inflammatory cytokine, IL-6 and IL-1β, levels. All graphs represent average of four replicates, mean ± SEM, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01. The data suggests that restoring GSNO levels mitigates Ch-CS-induced autophagy impairment and inflammation highlighting its ability to control chronic inflammatory response in COPD-emphysema. BALF, bronchoalveolar lavage fluid; ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; IL, interleukin. To see this illustration in color, the reader is referred to the web version of this article at www.liebertpub.com/ars

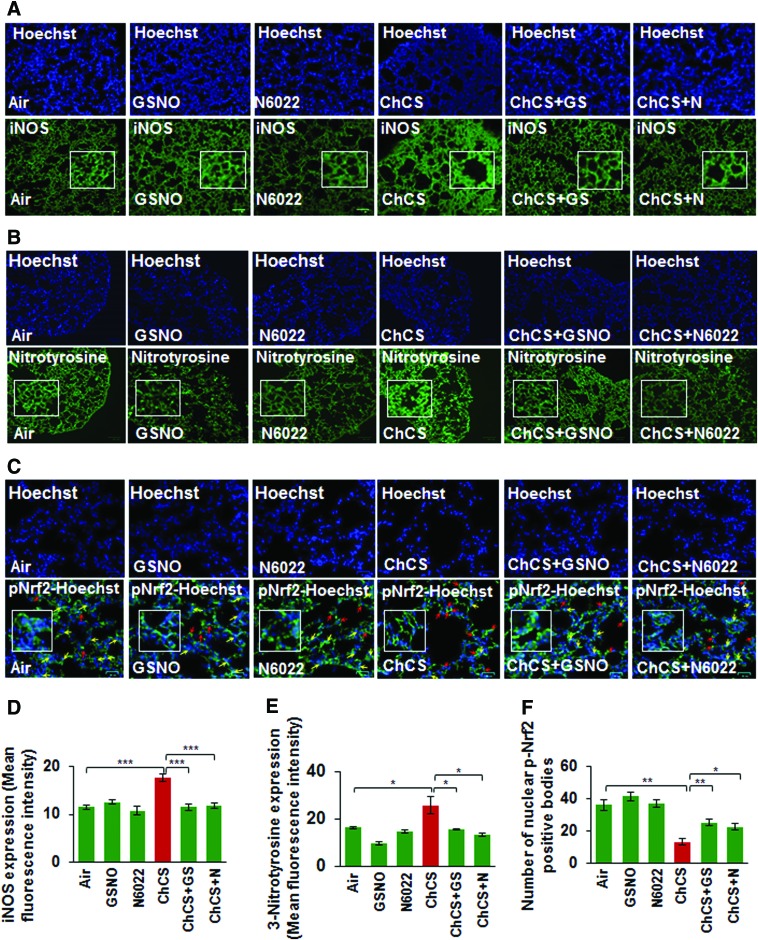

GSNO augmentation controls Ch-CS-induced oxidative-nitrosative stress

Increased expression of iNOS is implicated in a variety of pathological conditions (15, 40, 48, 68) and elevated oxidative-nitrosative stress triggers high iNOS levels (35). CS exposure-induced oxidative-nitrosative stress elevates iNOS expression that results in generation of toxic NO metabolites, which cause severe lung damage (29). GSNO has been previously reported to diminish iNOS expression levels (33, 59) and in-line with this prior observation, we demonstrate that Ch-CS-induced iNOS expression is significantly controlled by restoring GSNO levels by GSNO or GSNOR inhibitor, N6022 (Fig. 8A, D, ***p < 0.001). We also demonstrate that CS-induced 3-nitrotyrosine expression (a marker of cellular damage due to reactive nitrogen species, [RNS]) was diminished by GSNO or N6022 treatment (Fig. 8B, E, *p < 0.05). Moreover, we show that CS-induced decrease in nuclear localization of p-Nrf2, a critical regulator of antioxidant response pathways (12), is significantly elevated by GSNO augmentation by GSNO or N6022 treatment (Fig. 8C, F, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01), suggesting its therapeutic potential in controlling oxidative-nitrosative stress.

FIG. 8.

Augmentation of GSNO controls Ch-CS-induced nitrosative/oxidative stress. (A, B) Immunostaining of longitudinal lung sections from C57BL/6 mice exposed to RA or Ch-CS exposure (18 weeks, 5 h/day, 5 days/week) and/or treated with vehicle control (PBS), GSNO, or N6022 (4 mg/kg body weight, i.t., “three” total doses with a gap of 3 days) demonstrates that Ch-CS-mediated increase in iNOS and 3-nitrotyrosine (nitrosative/oxidative stress markers) expression (high-magnification images shown as insets) is significantly diminished by restoring intracellular GSNO levels by GSNO or GSNOR inhibitor (N6022). (C) The longitudinal lung sections described in (A) were immunostained with p-Nrf2 (antioxidant response marker) and the data indicate that Ch-CS-induced decrease in nuclear localization of p-Nrf2 (yellow arrows, insets) is significantly restored by GSNO or GSNOR inhibitor (N6022)-mediated augmentation of GSNO levels. The data also demonstrate that p-Nrf2 accumulates in the perinuclear spaces (red arrows) in Ch-CS-exposed mice lungs, which can be rescued by GSNO augmentation. (D–F) Data analysis represents average of four replicates shown as mean ± SEM [*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, scale bar: 100 μm in (A, B), 25 μm in (C)]. These findings suggest a potential therapeutic advantage of elevating lung GSNO levels in Ch-CS-mediated COPD-emphysema. iNOS, inducible nitric oxide synthase. To see this illustration in color, the reader is referred to the web version of this article at www.liebertpub.com/ars

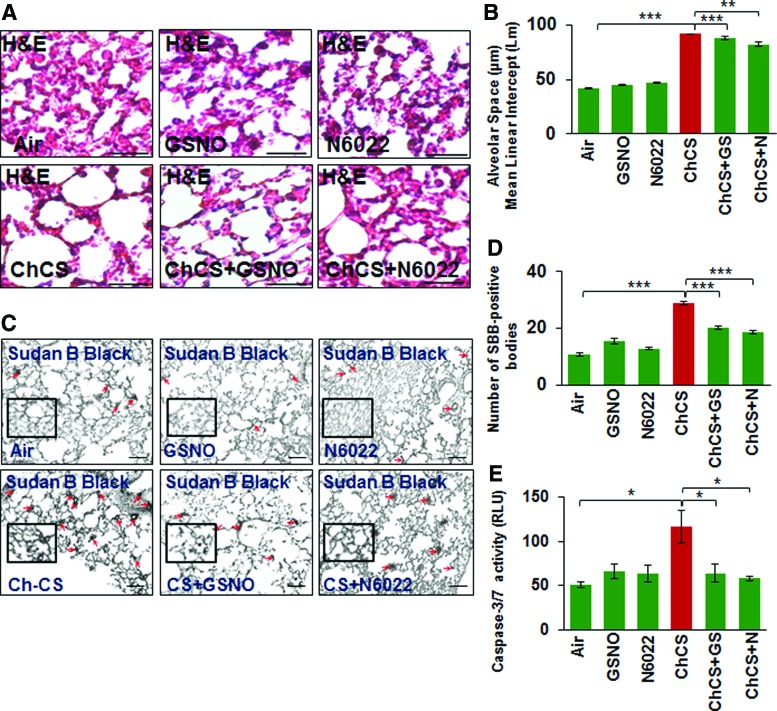

GSNO ameliorates Ch-CS-induced COPD-emphysema

To further verify the role of GSNO in emphysema pathogenesis, we tested the efficacy of GSNO or GSNOR inhibitor (N6022) in reducing CS-induced alveolar airspace enlargement (Lm) in murine lungs. Our data suggest that augmenting GSNO level results in a significant decrease in CS-induced lung damage (Lm), thus confirming its protective role in COPD-emphysema pathogenesis (Fig. 9A, B, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001). In addition, we observed that GSNO augmentation significantly reduces CS-induced cellular senescence and apoptotic cell death in murine lungs (Fig. 9C, D, *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001), confirming its effectiveness in controlling key pathological mechanisms mediating COPD-emphysema pathogenesis.

FIG. 9.

Augmenting GSNO physiological levels ameliorates structural and cellular changes related to COPD-emphysema pathogenesis. (A) The H&E staining of the longitudinal lung sections from C57BL/6 mice exposed to RA or Ch-CS exposure (18 weeks, 5 h/day, 5 days/week) and/or treated with vehicle control (PBS), GSNO, or N6022 (4 mg/kg body weight, i.t., “three” total doses with a gap of 3 days) demonstrates that restoration of intracellular GSNO significantly decreases the Ch-CS-induced alveolar airspace enlargement (Lm) indicative of emphysema. (B) Data represent mean ± SEM of four replicates (**p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, scale bar, 50 μm). (C, D) The mice lung sections as described above in (A) were stained with senescence marker dye, Sudan Black B. The data (mean ± SEM, n = 4, scale bar, 100 μm) verifies that restoring intracellular GSNO levels, by either GSNO or GSNOR inhibitor, can significantly (***p < 0.001) control alveolar cell senescence (red arrows, insets), a typical pathological feature of COPD-emphysema. (E) The caspase-3/7 activity in the total protein lysates isolated from murine lungs of these experimental groups [described in (A)] demonstrates that GSNO augmentation diminishes Ch-CS-induced caspase-3/7 activity demonstrating its ability to control apoptosis and resulting emphysema pathogenesis. H&E, hematoxylin and eosin. To see this illustration in color, the reader is referred to the web version of this article at www.liebertpub.com/ars

Discussion

Several studies now highlight the protective role of autophagy in tobacco smoke/eCV-induced COPD-emphysema pathogenesis (10, 11, 25, 31, 61). Exposure to CS induces oxidative-nitrosative stress and inflammation in the lungs that plays a crucial role in COPD-emphysema pathologies (34, 36, 47). CS-induced hyperactivation of ROS (oxidative stress) and iNOS (nitrosative stress) results in lung injury, inflammation, and cell death eventually causing lung alveolar cell wall destruction as a mechanism for emphysema pathogenesis (4, 35). We have previously shown that CS-induced autophagy impairment and the resulting aggresome formation are prognostic indicators of emphysema severity in COPD-emphysema subjects (10, 64). Intriguingly, we and others have shown that a dysfunctional CFTR protein leads to autophagy impairment that results in heightened inflammatory–oxidative stress in the airways (8, 38, 65). Also, human lung cells/mice exposed to CSE/CS, and COPD-emphysema subjects demonstrate diminished membrane CFTR expression and function (7, 14, 16, 54), which depicts the acquired CFTR dysfunction in COPD subjects (24, 52). Thus, strategies to reinstate the acquired CFTR dysfunction could have substantial therapeutic benefit in CS-induced COPD-emphysema, by controlling autophagy impairment and resulting inflammatory–oxidative stress.

It is important to note that pulmonary inflammatory–oxidative state and smooth muscle function in the airways is also regulated by NO-signaling (50, 57), which involves endogenous SNOs, such as GSNO (6, 13). The crucial role of GSNO in controlling airway tone and inflammation is evident and its augmentation is currently being utilized as a therapeutic strategy to combat airway inflammation (anti-inflammatory effects) and restore bronchoconstriction (bronchodilatory effects) (19, 27, 53). GSNO is formed by S-nitrosation of glutathione (GSH) and thought to mediate the downstream signaling effects of NO (13). Moreover, GSNO serves as a reservoir of endogenous NO, and its role in several disease states highlights the importance of regulating intracellular GSNO levels (6, 13, 27, 67). The enzyme, GSNOR, catalyzes the degradation of GSNO and helps in maintaining normal cellular GSNO levels (13). Elevated GSNOR activity has been implicated in respiratory diseases such as asthma and CF (6, 26). Moreover, it is perceived that NO generated via oxidative-nitrosative stress mediated pathological manifestations observed in neurodegenerative diseases (49). Thus, exposure to environmental toxins or the normal aging process can trigger higher than normal physiological levels of NO that causes aberrant protein S-nitrosylation, which triggers protein misfolding and aggregation leading to cellular injuries/death in neurodegenerative disorders. In addition, increased NO levels cause elevated generation of RNS, such as peroxynitrite that causes neurodegenerative disease states (45). Thus, generation of peroxynitrite from the interaction between superoxide (O2-) and NO could be attributed to the low NO bioavailability in oxidative-nitrosative stress-related pathological conditions such as COPD-emphysema (67), thereby disrupting normal NO-related functions in the lung. Thus, augmenting homeostatic NO or GSNO levels by inhibition of GSNOR is currently being evaluated for treatment of asthma and CF (26). In the present study, we wanted to evaluate the impact of restoring normal physiological GSNO or NO levels on acquired CFTR dysfunction, and resulting autophagy impairment and chronic inflammatory–oxidative stress using experimental in vitro and murine models of COPD-emphysema.

We report here that CFTR colocalizes with aggresome bodies with increasing severity of emphysema (GOLD I − IV) in COPD subjects (Fig. 1A–D), while smokers in either GOLD 0 (nonemphysema) or emphysema (GOLD I − IV) group had higher CFTR aggresome colocalization compared to nonsmokers. Our in vitro and murine data demonstrate a novel beneficial role of GSNO augmentation in controlling CS-induced acquired CFTR dysfunction (Figs. 2, 3, and 6), autophagy impairment, and resulting inflammatory–oxidative stress (14, 16) that mediates COPD-emphysema pathogenesis (7, 8, 24). Surprisingly, there are no studies showing the exact role of GSNO in the pathogenesis of COPD-emphysema although many of the pathological manifestations of these obstructive lung conditions are similar. CS exposure induces ROS-mediated deleterious effects on the airway, which includes oxidative stress-mediated protein misfolding (28) and aggresome pathology (10, 38), resulting in cellular senescence (20) and apoptosis (18). Similar to previous reports that have shown the antioxidant effects of GSNO (32, 56), we demonstrate here that CS-induced ROS activation, cellular senescence (Sudan Black B staining), and apoptosis (caspase-3/7 activity) are significantly decreased by GSNO augmentation using GSNO or GSNOR inhibitor, N6022 (Figs. 3A and 9C, D). These findings support our notion that augmenting GSNO levels could protect against CS-induced COPD-emphysema pathologies.

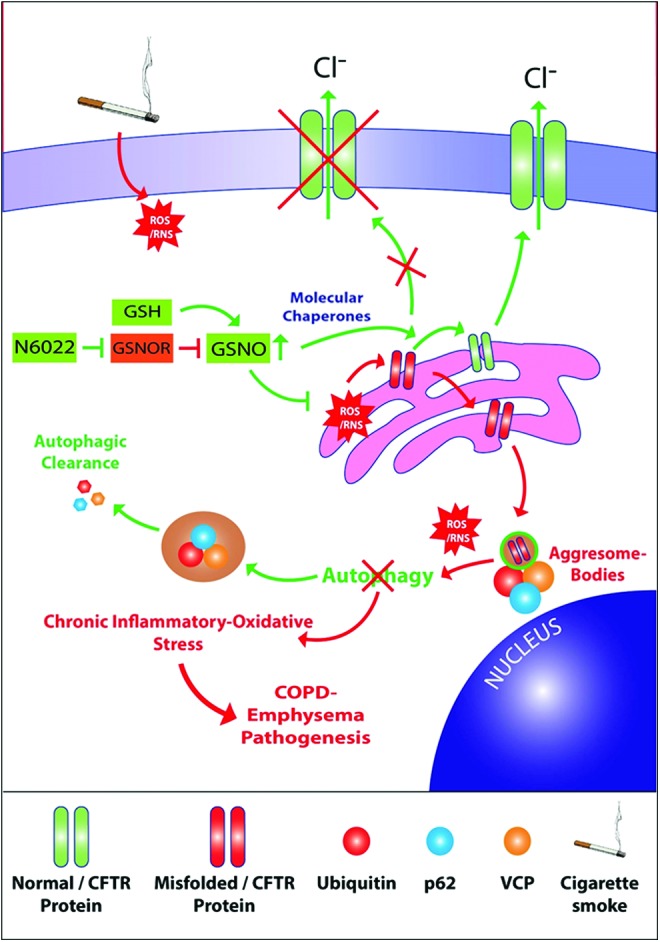

We also evaluated the impact of our GSNO augmentation strategy on the homeostatic autophagy process that is impaired on exposure to CS. Recent reports from our group and others demonstrate that CS exposure induces autophagy impairment marked by formation of perinuclear aggresome bodies (10, 25, 38, 64, 65). Notably, we and others have established the crucial role of ROS activation in protein misfolding, proteostasis and autophagy impairment and resulting aggresome pathology (10, 25, 38, 64). Thus, we postulated that augmentation of intracellular GSNO should at very least protect against CS-induced and ROS-mediated protein misfolding of CFTR and other ubiquitinated proteins. Interestingly, our GSNO augmentation strategy using GSNO or GSNOR inhibitor (N6022) not only significantly elevates CSE/CS-induced CFTR expression and overall protein misfolding (Fig. 2 − 4 and 6) but also autophagy impairment (Figs. 3B, C, 4, 6, and 7A, B), thus demonstrating for the first time that GSNO modulates critical autophagy responses in the airway via restoring CFTR from aggresome bodies. CS exposure also triggers severe pulmonary intrusion of inflammatory cells, which release protein-degrading enzymes (proteases) causing lung tissue destruction and continued inflammation leading to COPD-emphysema symptoms (2–5). GSNO has been shown to have potent anti-inflammatory properties and thus utilized to suppress inflammation in diverse disease states such as asthma (6, 27, 63), CF (70), ischemia/reperfusion-induced brain injury (32), chronic cerebral hypoperfusion (67), experimental periodontal disease (22), and so on. In the present study, CS-induced increase in levels of BALF-inflammatory cytokines, IL-6 and IL-1β, is significantly reduced by GSNO augmentation that is achieved by treatment with GSNO or GSNOR inhibitor (N6022) (Fig. 7C, D). Thus, we propose that augmenting GSNO levels could have therapeutic benefits in COPD-emphysema by correcting CS-induced acquired CFTR dysfunction and the resulting autophagy impairment and chronic inflammatory–oxidative stress (Fig. 10).

FIG. 10.

Schematic showing mechanism for correction of acquired CFTR dysfunction in COPD-emphysema by GSNO augmentation. CS exposure leads to ROS- and RNS-mediated protein misfolding, resulting in perinuclear accumulation of CFTR and ubiquitinated proteins. Thus, CS-ROS/RNS-mediated CFTR dysfunction impairs autophagy, resulting in induction of chronic inflammatory–oxidative stress followed by development and progression of severe emphysema in COPD subjects. Moreover, diminished GSNO/NO levels, due to CS-induced peroxynitrite, a highly reactive molecule, result in low bioavailability of NO. Thus, augmentation of GSNO allows rescue of functional CFTR on the plasma membrane, in addition to restoration of autophagy that can control chronic inflammatory–oxidative stress responses. Moreover, restoring normal GSNO levels, either directly by administration of GSNO or via treatment with GSNOR inhibitor (N6022), controls CS-induced acquired CFTR dysfunction, autophagy impairment, and resulting inflammatory–oxidative stress. In summary, GSNO augmentation strategy provides substantial therapeutic advantage in ameliorating CS-mediated COPD-emphysema pathogenesis by regulating mechanisms involved in initiation and progression of lung disease. NO, nitric oxide; RNS, reactive nitrogen species. To see this illustration in color, the reader is referred to the web version of this article at www.liebertpub.com/ars

Next, we confirmed potential mechanism(s) by which GSNO might be exerting its protective effects against CS-induced lung pathologies. GSNO has been evaluated by various clinical trials for CF and is reported to augment the maturation and expression of CFTR-protein by modulating CFTR co-chaperones such as Hsp70/Hsp90 (69, 71). We have previously shown that CS exposure decreases membrane/lipid raft CFTR protein expression and a decrease in membrane/raft CFTR expression is not only associated with severity of emphysema in COPD subjects (7) but also critical for emphysema progression in experimental preclinical CF models (8). Our present data shows for the first time that CS induces perinuclear accumulation of CFTR in aggresome bodies that was significantly restored by GSNO or GSNOR (N6022) treatment-mediated augmentation of GSNO levels (Fig. 5E, G, H). The data imply that CS-induced acquired CFTR dysfunction and the resulting autophagy impairment potentiate chronic inflammatory–oxidative stress that could be reverted by GSNO-augmentation, thus suggesting its potential therapeutic utility in COPD-emphysema treatment. Also, smokers with COPD-emphysema have a significantly higher expression of iNOS that is controlled by GSNO (30, 33). We verified that Ch-CS-induced iNOS and 3-nitrotyrosine (marker of cellular damage due to RNS) expression in murine lungs can be suppressed by augmenting GSNO levels (Fig. 8A, B). Thus, our data indicate that GSNO protects against pulmonary emphysema by controlling oxidative-nitrosative stress (p-Nrf2/iNOS/nitrotyrosine expression levels) and acquired CFTR dysfunction.

In conclusion, our study highlights the crucial role of GSNO signaling in ameliorating CS-induced acquired CFTR dysfunction and resulting autophagy impairment and chronic inflammation that triggers COPD-emphysema progression. Thus, we demonstrate the potential of GSNO augmentation as a therapeutic intervention strategy for controlling COPD-emphysema pathophysiology, which warrants further clinical evaluation.

Materials and Methods

Human subject's samples

The paraffin-embedded lung tissue sections were obtained from NHLBI Lung Tissue Research Consortium (LTRC, NIH). The clinical severity, sample size, and classification of COPD subjects were determined on the basis of the stages defined by GOLD (control nonemphysema [GOLD 0] and COPD-emphysema [GOLD I − IV], n = 10–15 for each group with total of 60 samples). The number of smokers and nonsmokers in each COPD GOLD stage is shown in Figure 1C. Our study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB), Central Michigan University and Johns Hopkins University, as “not a human subject research,” under exemption No. 4 and the subjects' lung function data and clinical parameters were obtained from LTRC without disclosing subjects' name and personal information. The classification of the nonemphysema and COPD-emphysema subjects used in this study is previously reported (9). We made sure that nonemphysema or COPD subjects had no other underlying condition other than emphysema for COPD subjects. Although each COPD group (GOLD I − IV) had one patient whose first-degree blood relative suffered from chronic bronchitis.

Murine experiments

We used our CMU IACUC-approved procedures to expose C57BL/6 mice (8 weeks, n = 4) to Ch-CS as previously described (9) and/or treated by intratracheal instillation with GSNO (4 mg/kg body weight), GSNOR inhibitor (N6022, 4 mg/kg body weight), or PBS vehicle control. Briefly, the mice were exposed to room air (control) or Ch-CS (18 weeks) using the TE-2 cigarette smoking machine (Teague Enterprises). The CS was generated by burning 3R4F (0.73 mg nicotine per cigarette) research grade cigarettes (Tobacco Research Institute, University of Kentucky, Lexington, KY) and mice were exposed to direct whole-body smoke for 3 h/day followed by another 2 h in the same chamber without burning more cigarettes. This protocol resulted in an average total particulate matter (TPM) of 150 mg/m3. For treatment, the mice received a total of three doses of the drugs within a 10-day interval (scale, Fig. 5A) before terminal euthanasia following our IACUC-approved protocols. The lung tissues and BALF samples were collected from each group for further analysis by immunoblotting, immunofluorescence microscopy, and flow cytometry.

Western blotting

Western blotting was performed according to our recently described protocol (10, 11) to quantify changes in expression and/or accumulation of ubiquitinated proteins (Ub) and CFTR in the soluble and insoluble protein fractions isolated from murine lungs and Beas2b-cells. The β-actin was used as the loading control. All antibodies were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology with the exception of CFTR (181, rabbit polyclonal) and β-actin, procured from Sigma.

Immunostaining, lung morphometry, and caspase-3/7 assay

The human lung tissue sections were costained with aggresome-specific dye (red, PROTEOSTAT Aggresome Detection Kit; Enzo Life Sciences) and CFTR primary antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) followed by the anti-rabbit CFL-488 secondary antibody (green). The nucleus was stained using the Hoechst stain and images were captured using the Zoe™ Fluorescent cell imager (Bio-Rad). Lung tissues from all the six different murine experimental groups (n = 4; room air, GSNO, N6022, Ch-CS, Ch-CS+GNSO, and Ch-CS+N6022) were collected in 10% neutral buffer formalin. The lung tissue was prepared for histology by preparing paraffin blocks that were cut into 5 μm sections. These sections were then deparaffinized and stained using our previously described immunostaining protocol (9, 10). The primary antibodies used were CFTR (rabbit polyclonal; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), p62 (rabbit polyclonal; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), iNOS (rabbit polyclonal; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), 3-nitrotyrosine (rabbit polyclonal; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), p-Nrf2 (rabbit monoclonal; Abcam), or Ub (mouse polyclonal; Santa Cruz Biotechnology). The secondary antibodies were anti-rabbit CFL-488 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and anti-mouse Texas Red (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). In a parallel experiment, these murine lung tissue sections were costained with aggresome-specific dye (red, PROTEOSTAT Aggresome Detection Kit; Enzo Life Sciences) and CFTR primary antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) followed by the anti-rabbit CFL-488 secondary antibody (green). Hoechst stain was used to identify the nucleus. Sections were then mounted on slides using 90% glycerol, and Zoe Fluorescent cell imager (Bio-Rad) was used to visualize tissue areas. These sections were also stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) or Sudan Black B to monitor alveolar tissue destruction by quantifying changes in mean alveolar diameter (Lm), or cellular senescence, respectively, as recently described (10, 64). For the immunofluorescence staining in Beas2b cells, the primary antibodies used were TFEB (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and p62 (mouse monoclonal; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) followed by anti-rabbit CFL-488 (green) and anti-mouse Texas Red (red) secondary antibodies. The Caspase-Glo™ 3/7 assay kit (Promega) was used to quantify the changes in caspase-3/7 activity in total lung lysates from the same groups of mice using recently described protocol (10).

Cell culture, transfections, autophagy reporter/flux, and ROS assay

Beas2b cells were cultured as recently described (10, 11) and were cotransfected with Ub-RFP and LC3B-GFP plasmids using Lipofectamine® 2000 (24 h; Invitrogen) and treated with control (PBS), GSNO (10 μM), N6022 (10 μM), 5% CSE, CSE+GSNO, or CSE+N6022 for 12 h. In a parallel experiment, functional autophagy was quantified using the Premo™ Autophagy Tandem Sensor RFP-GFP-LC3B assay kit (Molecular Probes) as recently described (10, 61). Briefly, Beas2b cells were incubated with BacMam reagent for 16 h followed by treatment with control (PBS), GSNO (10 μM), N6022 (10 μM), CSE (5%), CSE+GSNO, or CSE+N6022 for 12 h. In a separate experiment, the WT-CFTR protein colocalized with ubiquitinated proteins in Beas2b cells was visualized by transiently transfecting cells with Ub-RFP and/or WT-CFTR GFP plasmids (24 h) followed by treatment with control (PBS), GSNO (10 μM), N6022 (10 μM), 5% CSE, CSE+GSNO, or CSE+N6022 for 12 h. Cells were visualized using the Zoe Fluorescent cell imager (Bio-Rad) as recently described (10, 11). The changes in ROS levels were quantified in the similar experimental groups using the CM-DCFDA ROS indicator dye (Invitrogen) as recently described (11).

Flow cytometry and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

Flow cytometry was performed as recently described (10, 11) to monitor changes in the number of Ub-p62+ cells in either Beas2b cells or BALF cells exposed to room air or CS and treated with PBS, GSNO, or N6022. The data were acquired using the BD FACS Aria flow cytometer and analyzed by the FACS Diva Software as recently described (10, 11). To quantify changes in the levels of IL-6 and IL-1β cytokines in BALF samples of each experimental group, standard enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) was performed as previously described (7, 10).

Statistical analysis

Data are shown as mean ± standard error of the mean for n = 3–4 replicates from at least three experiments. A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey's post hoc test or one-tailed Student's t-test was performed to determine significant changes in treatment groups compared to controls. A p-value of ≤0.05 was considered a significant change. In addition, Pearson's correlation analysis was used to determine the correlation between the two data sets and the correlation coefficient is shown as “r” value. Immunoblotting data were quantified using the ImageJ software (NIH).

Supplementary Material

Abbreviations Used

- ADMA

asymmetric dimethyl arginine

- BALF

bronchoalveolar lavage fluid

- CF

cystic fibrosis

- CFTR

cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator

- Ch-CS

chronic cigarette smoke

- COPD

chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- CS

cigarette smoke

- CSE

cigarette smoke extract

- CYS

cysteamine

- DSS

dextran sulfate sodium

- eCV

e-cigarette vapor

- FeNO

fractional exhaled nitric oxide

- GFP

green fluorescent protein

- GOLD

Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease

- GSNO

S-nitrosoglutathione

- GSNOR

S-nitrosoglutathione reductase

- IL

interleukin

- LTRC

Lung Tissue Research Consortium

- NO

nitric oxide

- p62/SQSTM1

sequestosome 1

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

- RFP

red fluorescent protein

- RNS

reactive nitrogen species

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- SNOs

S-nitrosothiols

- TFEB

transcription factor-EB

- Ub

ubiquitin

- WT-CFTR

wild-type cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator

Acknowledgments

We thank the NHLBI Lung Tissue Research Consortium (LTRC, NIH) for providing human lung tissue sections and Philip Oshel, Director of the Microscopy Core Facility, Central Michigan University, for help with the confocal microscopy experiments. We also thank April Ilacqua, FACS student technician, for assistance during the flow cytometry experiments. The study was supported by the Flight Attendant Medical Research Institute's (FAMRI), Young Clinical Scientist Award (YCSA_082131) to N.V. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, and decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

Authors' Contributions

Conception and design: N.V.; analysis and interpretation: N.V., M.B.; experimental contribution: M.B., N.V., D.S., K.W., K.B.; drafting of manuscript and editing: M.B., N.V.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Aydin M, Altintas N, Cem Mutlu L, Bilir B, Oran M, Tulubas F, Topcu B, Tayfur I, Kucukyalcin V, Kaplan G, and Gurel A. Asymmetric dimethylarginine contributes to airway nitric oxide deficiency in patients with COPD. Clin Respir J 2015, [Epub ahead of print]; DOI: 10.1111/crj.12337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barnes PJ. New concepts in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Annu Rev Med 54: 113–129, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barnes PJ. The cytokine network in asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Clin Invest 118: 3546–3556, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barnes PJ. Inflammatory mechanisms in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Allergy Clin Immunol 138: 16–27, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barnes PJ, Shapiro SD, and Pauwels RA. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: Molecular and cellular mechanisms. Eur Respir J 22: 672–688, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blonder JP, Mutka SC, Sun X, Qiu J, Green LH, Mehra NK, Boyanapalli R, Suniga M, Look K, Delany C, Richards JP, Looker D, Scoggin C, and Rosenthal GJ. Pharmacologic inhibition of S-nitrosoglutathione reductase protects against experimental asthma in BALB/c mice through attenuation of both bronchoconstriction and inflammation. BMC Pulm Med 14: 3, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bodas M, Min T, Mazur S, and Vij N. Critical modifier role of membrane-cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator-dependent ceramide signaling in lung injury and emphysema. J Immunol 186: 602–613, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bodas M, Min T, and Vij N. Critical role of CFTR-dependent lipid rafts in cigarette smoke-induced lung epithelial injury. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 300: L811–L820, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bodas M, Min T, and Vij N. Lactosylceramide-accumulation in lipid-rafts mediate aberrant-autophagy, inflammation and apoptosis in cigarette smoke induced emphysema. Apoptosis 20: 725 − 739, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bodas M, Patel N, Silverberg D, Walworth K, and Vij N. Master autophagy regulator transcription factor-EB (TFEB) regulates cigarette smoke induced autophagy-impairment and COPD-emphysema pathogenesis. Antioxid Redox Signal 2016, [Epub ahead of print]; DOI: 10.1089/ars.2016.6842 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bodas M, Westpal C, Thompson-Carpenter R, Mohanty D, and Vij N. Nicotine exposure induces bronchial epithelial cell apoptosis and senescence via ROS mediated autophagy-impairment. Free Radic Biol Med 97: 441 − 453, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boutten A, Goven D, Boczkowski J, and Bonay M. Oxidative stress targets in pulmonary emphysema: Focus on the Nrf2 pathway. Expert Opin Ther Targets 14: 329–346, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Broniowska KA, Diers AR, and Hogg N. S-nitrosoglutathione. Biochim Biophys Acta 1830: 3173–3181, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cabanski M, Fields B, Boue S, Boukharov N, DeLeon H, Dror N, Geertz M, Guedj E, Iskandar A, Kogel U, Merg C, Peck MJ, Poussin C, Schlage WK, Talikka M, Ivanov NV, Hoeng J, and Peitsch MC. Transcriptional profiling and targeted proteomics reveals common molecular changes associated with cigarette smoke-induced lung emphysema development in five susceptible mouse strains. Inflamm Res 64: 471–486, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Campos D, Ravagnani FG, Gurgueira SA, Vercesi AE, Teixeira SA, Costa SK, Muscara MN, and Ferreira HH. Increased glutathione levels contribute to the beneficial effects of hydrogen sulfide and inducible nitric oxide inhibition in allergic lung inflammation. Int Immunopharmacol 39: 57–62, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cantin AM. Cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator. Implications in cystic fibrosis and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Ann Am Thorac Soc 13 Suppl. 2: S150–S155, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen L, Patel RP, Teng X, Bosworth CA, Lancaster JR, Jr, and Matalon S. Mechanisms of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator activation by S-nitrosoglutathione. J Biol Chem 281: 9190–9199, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Circu ML. and Aw TY. Reactive oxygen species, cellular redox systems, and apoptosis. Free Radic Biol Med 48: 749–762, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Colagiovanni DB, Drolet DW, Langlois-Forget E, Piche MP, Looker D, and Rosenthal GJ. A nonclinical safety and pharmacokinetic evaluation of N6022: A first-in-class S-nitrosoglutathione reductase inhibitor for the treatment of asthma. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol 62: 115–124, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Colavitti R. and Finkel T. Reactive oxygen species as mediators of cellular senescence. IUBMB Life 57: 277–281, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Corti A, Franzini M, Scataglini I, and Pompella A. Mechanisms and targets of the modulatory action of S-nitrosoglutathione (GSNO) on inflammatory cytokines expression. Arch Biochem Biophys 562: 80–91, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.de Menezes AM, de Souza GF, Gomes AS, de Carvalho Leitao RF, Ribeiro Rde A, de Oliveira MG, and de Castro Brito GA. S-nitrosoglutathione decreases inflammation and bone resorption in experimental periodontitis in rats. J Periodontol 83: 514–521, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.De Stefano D, Villella VR, Esposito S, Tosco A, Sepe A, De Gregorio F, Salvadori L, Grassia R, Leone CA, De Rosa G, Maiuri MC, Pettoello-Mantovani M, Guido S, Bossi A, Zolin A, Venerando A, Pinna LA, Mehta A, Bona G, Kroemer G, Maiuri L, and Raia V. Restoration of CFTR function in patients with cystic fibrosis carrying the F508del-CFTR mutation. Autophagy 10: 2053–2074, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dransfield MT, Wilhelm AM, Flanagan B, Courville C, Tidwell SL, Raju SV, Gaggar A, Steele C, Tang LP, Liu B, and Rowe SM. Acquired cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator dysfunction in the lower airways in COPD. Chest 144: 498–506, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fujii S, Hara H, Araya J, Takasaka N, Kojima J, Ito S, Minagawa S, Yumino Y, Ishikawa T, Numata T, Kawaishi M, Hirano J, Odaka M, Morikawa T, Nishimura S, Nakayama K, and Kuwano K. Insufficient autophagy promotes bronchial epithelial cell senescence in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Oncoimmunology 1: 630–641, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gaston B, Singel D, Doctor A, and Stamler JS. S-nitrosothiol signaling in respiratory biology. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 173: 1186–1193, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Green LS, Chun LE, Patton AK, Sun X, Rosenthal GJ, and Richards JP. Mechanism of inhibition for N6022, a first-in-class drug targeting S-nitrosoglutathione reductase. Biochemistry 51: 2157–2168, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gregersen N. and Bross P. Protein misfolding and cellular stress: An overview. Methods Mol Biol 648: 3–23, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gupta I, Ganguly S, Rozanas CR, Stuehr DJ, and Panda K. Ascorbate attenuates pulmonary emphysema by inhibiting tobacco smoke and Rtp801-triggered lung protein modification and proteolysis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 113: E4208−E4217, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jiang WT, Liu XS, Xu YJ, Ni W, and Chen SX. Expression of nitric oxide synthase isoenzyme in lung tissue of smokers with and without chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Chin Med J (Engl) 128: 1584–1589, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kelsen SG. The unfolded protein response in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Ann Am Thorac Soc 13 Suppl. 2: S138–S145, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Khan M, Sakakima H, Dhammu TS, Shunmugavel A, Im YB, Gilg AG, Singh AK, and Singh I. S-nitrosoglutathione reduces oxidative injury and promotes mechanisms of neurorepair following traumatic brain injury in rats. J Neuroinflammation 8: 78, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Khan M, Sekhon B, Giri S, Jatana M, Gilg AG, Ayasolla K, Elango C, Singh AK, and Singh I. S-Nitrosoglutathione reduces inflammation and protects brain against focal cerebral ischemia in a rat model of experimental stroke. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 25: 177–192, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kirkham PA. and Barnes PJ. Oxidative stress in COPD. Chest 144: 266–273, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lanzetti M, da Costa CA, Nesi RT, Barroso MV, Martins V, Victoni T, Lagente V, Pires KM, e Silva PM, Resende AC, Porto LC, Benjamim CF, and Valenca SS. Oxidative stress and nitrosative stress are involved in different stages of proteolytic pulmonary emphysema. Free Radic Biol Med 53: 1993–2001, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee H, Park JR, Kim EJ, Kim WJ, Hong SH, Park SM, and Yang SR. Cigarette smoke-mediated oxidative stress induces apoptosis via the MAPKs/STAT1 pathway in mouse lung fibroblasts. Toxicol Lett 240: 140–148, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Logotheti H, Pourzitaki C, Tsaousi G, Aidoni Z, Vekrakou A, Ekaterini A, and Gourgoulianis K. The role of exhaled nitric oxide in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease undergoing laparotomy surgery - The noxious study. Nitric Oxide 61: 62 − 68, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Luciani A, Villella VR, Esposito S, Brunetti-Pierri N, Medina D, Settembre C, Gavina M, Pulze L, Giardino I, Pettoello-Mantovani M, D'Apolito M, Guido S, Masliah E, Spencer B, Quaratino S, Raia V, Ballabio A, and Maiuri L. Defective CFTR induces aggresome formation and lung inflammation in cystic fibrosis through ROS-mediated autophagy inhibition. Nat Cell Biol 12: 863–875, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Maiuri MC, Criollo A, and Kroemer G. Crosstalk between apoptosis and autophagy within the Beclin 1 interactome. EMBO J 29: 515–516, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Malaviya R, Sunil VR, Venosa A, Vayas KN, Heck DE, Laskin JD, and Laskin DL. Inflammatory mechanisms of pulmonary injury induced by mustards. Toxicol Lett 244: 2–7, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Malerba M. and Montuschi P. Non-invasive biomarkers of lung inflammation in smoking subjects. Curr Med Chem 19: 187–196, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Malerba M, Radaeli A, Olivini A, Damiani G, Ragnoli B, Montuschi P, and Ricciardolo FL. Exhaled nitric oxide as a biomarker in COPD and related comorbidities. Biomed Res Int 2014: 271918, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Min T, Bodas M, Mazur S, and Vij N. Critical role of proteostasis-imbalance in pathogenesis of COPD and severe emphysema. J Mol Med (Berl) 89: 577–593, s2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Montagna C, Rizza S, Maiani E, Piredda L, Filomeni G, and Cecconi F. To eat, or NOt to eat: S-nitrosylation signaling in autophagy. FEBS J 283: 3857 − 3869, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nakamura T. and Lipton SA. Protein S-nitrosylation as a therapeutic target for neurodegenerative diseases. Trends Pharmacol Sci 37: 73–84, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ni I, Ji C, and Vij N. Second-hand cigarette smoke impairs bacterial phagocytosis in macrophages by modulating CFTR dependent lipid-rafts. PLoS One 10: e0121200, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nyunoya T, Mebratu Y, Contreras A, Delgado M, Chand HS, and Tesfaigzi Y. Molecular processes that drive cigarette smoke-induced epithelial cell fate of the lung. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 50: 471–482, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Oliveira-Paula GH, Lacchini R, and Tanus-Santos JE. Inducible nitric oxide synthase as a possible target in hypertension. Curr Drug Targets 15: 164–174, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pannu R. and Singh I. Pharmacological strategies for the regulation of inducible nitric oxide synthase: Neurodegenerative versus neuroprotective mechanisms. Neurochem Int 49: 170–182, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Perez-Zoghbi JF, Bai Y, and Sanderson MJ. Nitric oxide induces airway smooth muscle cell relaxation by decreasing the frequency of agonist-induced Ca2+ oscillations. J Gen Physiol 135: 247–259, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Que LG, Yang Z, Stamler JS, Lugogo NL, and Kraft M. S-nitrosoglutathione reductase: An important regulator in human asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 180: 226–231, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rab A, Rowe SM, Raju SV, Bebok Z, Matalon S, and Collawn JF. Cigarette smoke and CFTR: Implications in the pathogenesis of COPD. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 305: L530–L541, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Raffay TM, Dylag AM, Di Fiore JM, Smith LA, Einisman HJ, Li Y, Lakner MM, Khalil AM, MacFarlane PM, Martin RJ, and Gaston B. S-nitrosoglutathione attenuates airway hyperresponsiveness in murine bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Mol Pharmacol 90: 418–426, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Raju SV, Jackson PL, Courville CA, McNicholas CM, Sloane PA, Sabbatini G, Tidwell S, Tang LP, Liu B, Fortenberry JA, Jones CW, Boydston JA, Clancy JP, Bowen LE, Accurso FJ, Blalock JE, Dransfield MT, and Rowe SM. Cigarette smoke induces systemic defects in cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator function. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 188: 1321–1330, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rao P, Ande A, Sinha N, Kumar A, and Kumar S. Effects of cigarette smoke condensate on oxidative stress, apoptotic cell death, and HIV replication in human monocytic cells. PLoS One 11: e0155791, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rauhala P, Lin AM, and Chiueh CC. Neuroprotection by S-nitrosoglutathione of brain dopamine neurons from oxidative stress. FASEB J 12: 165–173, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Reynaert NL, Ckless K, Wouters EF, van der Vliet A, and Janssen-Heininger YM. Nitric oxide and redox signaling in allergic airway inflammation. Antioxid Redox Signal 7: 129–143, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ricciardolo FL, Sorbello V, and Ciprandi G. FeNO as biomarker for asthma phenotyping and management. Allergy Asthma Proc 36: e1–e8, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rosales MA, Silva KC, Duarte DA, de Oliveira MG, de Souza GF, Catharino RR, Ferreira MS, Lopes de Faria JB, and Lopes de Faria JM. S-nitrosoglutathione inhibits inducible nitric oxide synthase upregulation by redox posttranslational modification in experimental diabetic retinopathy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 55: 2921–2932, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Santini G, Mores N, Shohreh R, Valente S, Dabrowska M, Trove A, Zini G, Cattani P, Fuso L, Mautone A, Mondino C, Pagliari G, Sala A, Folco G, Aiello M, Pisi R, Chetta A, Losi M, Clini E, Ciabattoni G, and Montuschi P. Exhaled and non-exhaled non-invasive markers for assessment of respiratory inflammation in patients with stable COPD and healthy smokers. J Breath Res 10: 017102, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Shivalingappa PC, Hole R, Westphal CV, and Vij N. Airway exposure to e-cigarette vapors impairs autophagy and induces aggresome formation. Antioxid Redox Signal 2015, [Epub ahead of print]; DOI: 10.1089/ars.2015.6367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sugiura H. and Ichinose M. Nitrative stress in inflammatory lung diseases. Nitric Oxide 25: 138–144, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sun X, Wasley JW, Qiu J, Blonder JP, Stout AM, Green LS, Strong SA, Colagiovanni DB, Richards JP, Mutka SC, Chun L, and Rosenthal GJ. Discovery of S-nitrosoglutathione reductase inhibitors: Potential agents for the treatment of asthma and other inflammatory diseases. ACS Med Chem Lett 2: 402–406, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tran I, Ji C, Ni I, Min T, Tang D, and Vij N. Role of cigarette smoke-induced aggresome formation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease-emphysema pathogenesis. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 53: 159–173, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Vij N. Nano-based rescue of dysfunctional autophagy in chronic obstructive lung diseases. Expert Opin Drug Deliv 1–7, 2016, [Epub ahead of print]; DOI: 10.1080/17425247.2016.1223040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Vij N, Chandramani P, Westphal C, Hole R, and Bodas M. Cigarette smoke induced autophagy-impairment accelerates lung aging, COPD-emphysema exacerbations and pathogenesis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 193: A2334, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Won JS, Kim J, Annamalai B, Shunmugavel A, Singh I, and Singh AK. Protective role of S-nitrosoglutathione (GSNO) against cognitive impairment in rat model of chronic cerebral hypoperfusion. J Alzheimers Dis 34: 621–635, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Won JS, Singh AK, and Singh I. Lactosylceramide: A lipid second messenger in neuroinflammatory disease. J Neurochem 103 Suppl. 1: 180–191, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zaman K, Bennett D, Fraser-Butler M, Greenberg Z, Getsy P, Sattar A, Smith L, Corey D, Sun F, Hunt J, Lewis SJ, and Gaston B. S-Nitrosothiols increases cystic fibrosis transmembrane regulator expression and maturation in the cell surface. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 443: 1257–1262, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zaman K, Carraro S, Doherty J, Henderson EM, Lendermon E, Liu L, Verghese G, Zigler M, Ross M, Park E, Palmer LA, Doctor A, Stamler JS, and Gaston B. S-nitrosylating agents: A novel class of compounds that increase cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator expression and maturation in epithelial cells. Mol Pharmacol 70: 1435–1442, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zaman K, Sawczak V, Zaidi A, Butler M, Bennett D, Getsy P, Zeinomar M, Greenberg Z, Forbes M, Rehman S, Jyothikumar V, DeRonde K, Sattar A, Smith L, Corey D, Straub A, Sun F, Palmer L, Periasamy A, Randell S, Kelley TJ, Lewis SJ, and Gaston B. Augmentation of CFTR maturation by S-nitrosoglutathione reductase. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 310: L263−L270, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.