Abstract

In support of ongoing research in the study of corneal and skin wound healing, we sought to improve on previously published results by using iontophoresis to deliver RNA interference-based oligonucleotides. By using a electromechanics-based approach, we were able to devise a two-phase solution that separated the buffering solution from the antisense oligonucleotide (ASO) solution. The separation was obtained by making the drug solution a higher density than the buffer, leading it to sink directly onto the tissue surface. This change immediately decreased the distance that the ASO would have to travel before delivery. The changes enabled delivery into ex vivo skin and corneas in 10 or fewer minutes and into in vivo corneas in 5 min. In vivo studies demonstrated short-term bioavailability of at least 24 h, a lack of chemical or thermal injury, a lack of interference in the healing of a corneal injury, and an antisense effect till at least day 7, but not day 14. The only side-effect observed was postdelivery edema that was not present when the vehicle alone was iontophoresed. This suggests that electro-osmotic flow from the delivery chamber was not the mechanism, but that the delivered solute likely increased the tissue's osmolarity. These results support the continued development and utilization of this ASO delivery approach in research-grade oligonucleotides to probe molecular biological pathways and in support of testing therapeutic ASOs in the skin and cornea.

Keywords: : antisense, iontophoresis, delivery, cornea, skin, biological variance

Introduction

Growth factors are biological molecules that are found to be necessary to support the growth of tissue through actions of proliferation, migration, and extracellular matrix protein production. Many growth factors are proteins, rendering them as targetable by RNA interference (RNAi) mechanisms of control. The targeted reduction of a growth factor, or several growth factors, is the subject of ongoing research both as a tool for probing the molecular biology of these growth factors and as possible future drugs [1,2]. However, owing to their size and charge, the RNAi oligonucleotides have proved challenging to deliver into the tissue of interest, with adequate diffusion throughout the tissue, and with adequate uptake into the targeted cells.

One approach to improve delivery and uptake is the use of electromotive force to selectively drive the highly charged oligonucleotides into the targeted tissue. This process is termed iontophoresis when it is employed for drug delivery, but it is physically not different from electrophoresis. Iontophoresis has been successfully used to deliver small-molecule drugs and dyes into a variety of tissues for both research [3–7] and therapeutic [8–11] applications. More recently, it has been employed in the transepithelial delivery of riboflavin into the cornea before corneal crosslinking to treat keratoconus [12–17]. The success of these efforts has encouraged additional research into improving the delivery of oligonucleotide-based drugs. Berdugo et al. were the first to report successful delivery and short-term bioavailability of fluorescently labeled reporter antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs) into rat corneas [18] by using a 90 min treatment time. However, others have also reported success in delivering oligonucleotides [19], proteins or other macromolecules [19,20], or plasmids [21] into a variety of ocular tissues.

In setting out to employ iontophoresis in the studying of fibrosis in the cornea and skin, we found only a few theoretical treatments of the subject that could provide guidance for improving on the efficacy, safety, and treatment duration. There are at least two theories that we found to explain iontophoresis in the literature, though neither stands up to scrutiny. Faraday's Electrochemical Law is considered by some to describe iontophoretic delivery [22–24], but instead, it solely describes the generation of electrolytic byproducts, since it lacks any considerations of how far the molecule would need to travel to be delivered. Another explanation is the Nernst-Planck kinetic electrodiffusion theory, which employs a statistical mechanics approach [23]. However, a cursory examination again reveals a lack of spatial terms that are necessary to predict delivery times and tissue penetration depth. To improve iontophoresis as a nucleic acid therapy tool, a new model based on simple mechanics and electromotive force was employed. The general principles of this model were used to guide an initial nonoptimized design to enable delivery of an ASO into tissue without major chemical or thermal damage.

The simple mechanics approach begins with the observation that diffusive forces are not enough to surmount the resistance to delivery. At the molecular level, the drug is attempting to be delivered in-between the polar heads of the lipid bilayer to enter a cell, or in-between those same heads at the cell-cell boundary to penetrate the tissue. The combined resistance due to the size and polarity effectively forms a barrier that requires more force to surmount. For charged drugs, placing them in an electric field will impart an additional force on the drug, which may be able to overcome the barrier; the higher the electric field, the higher the force. The electric field is defined as the gradient of voltage throughout a medium, and in the context of iontophoresis, the voltage drop across a solution is proportional to the force imparted on the charged molecules in that solution. Iontophoretic delivery conditions are typically described by using current density, and by substituting the definition of resistance into Ohm's Law, the electric field in the direction of the current (V/x) is proportional to the current density and resistivity of the medium (Equation 1).

|

Equation 1. Ohm's Law Links the Electric Field and Current Density. V is the voltage, I is the current, and R is the resistance. When the definition of resistance is substituted, a relationship between the current density (I/A), the electric field (V/x), and the resistivity (ρ) is found, which is consistent with the reported findings for iontophoretic delivery where higher current densities and solvent resistivity lead to better delivery.

On this basis, 18.2 MΩ diH2O might seem the best vehicle, since it maximizes the voltage drop and therefore the electromotive force on the drug; however, in practice, electrolysis and tissue sensitivity to the electrolytic byproducts obviate the use of diH2O in most situations (Fig. 1). Some issues such as keratinized skin may be able to tolerate this exposure for short durations, whereas the tissues of the ocular surface cannot do so. Physiologically tolerable buffers are required and can be analytically tested for adequacy by properly employing Faraday's Electrochemical Law. Simply put, the amount of charge delivered to a solution (the current × dosing time, converted to an electron quantity basis) is the maximum amount of electrolytic byproducts that could be generated. By ensuring that the solution's buffering capacity could handle that much acid/base at either electrode, the caustic materials can be managed. This approach does not account for the fact that the caustic agents must migrate through the delivery solution to the tissue surface; it, therefore, safely underestimates the amount of safe treatment time.

FIG. 1.

A pilot study guided by the initial literature review. (A) Corneal opacification when following the current literature's suggested methods. The animal was not allowed to leave general anesthesia and was immediately euthanized. (B) Ex vivo testing with Nile Blue (as a pH indicator). (C) The migrating cylindrical front of solvent with pH >8.0 would explain the observed opacification pattern.

The use of the simple electromechanics approach also provides insight into spatial considerations of the design of the iontophoresis system. The different regions (tissues and fluids) in between the electrodes should be considered separately for design purposes, and the desired physical effects should be explicitly stated. For instance, the material in direct contact with the tissue needs to be tolerated by the tissue, [2] the material in direct contact with the electrodes needs to be able to manage/buffer the caustic electrolytic byproducts, [3] the medium used to carry the drug should have minimal, if any, nondrug ions, and [4] the medium used to carry the drug should be as physically close to the target as possible. Immediately apparent is that constraints 2 and 3 suggest the need for a dual-phase system, with separate buffering and drug solutions. This separation could also help with constraint 4 as well (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Physical considerations enable substantial improvement of iontophoresis. The physical model of the iontophoresis setup as described in the literature (left) and as is proposed for improved performance and safety (right).

With these a priori design constraints in mind, a dual-phase system with a physically distinct buffering phase and drug phase was designed and tested for its ability to deliver a 20 nt ssDNA oligonucleotide. We sought to determine whether the improved method of iontophoresis, with adequate buffering and reduced drug transport distance, could deliver an ASO into external surfaces of the body, including normal keratinized skin, highly keratinized skin, the intact cornea, debrided dermis, a sutured surgical incision in skin, and excimer-ablated corneas. Furthermore, to determine the tolerability of the treatment, we sought to determine whether iontophoresis of the ASOs impaired epithelial healing of excimer-ablated rabbit corneas. Finally, after determining the nature of the statistical distribution of a target gene during corneal wound healing, we sought to determine the capacity of iontophoretically delivered ASOs to reduce target protein levels 1 and 2 weeks after treatment.

Materials and Methods

The primary oligonucleotide used throughout is a 20 nt ASO that came paired with a goat polyclonal antibody raised against it (reporter ASO) [25]. Another ASO with the same sequence, but without the protecting chemistries, was synthesized with the addition of a 5′ end labeled 5′-carboxyfluoresecin (5-FAM ASO) to more readily visualize the oligonucleotide. To reduce the risk of monitoring nonattached 5-FAM, the oligonucleotides were ordered, desalted, and purified by HPLC (Integrated DNA Technologies, Inc., San Diego, CA). For in vitro studies with the unlabeled oligonucleotide, the ASO was mixed with diluted Nile Blue, which binds to the ASO via ionic interactions [26] for real-time visualization.

In vitro testing of the dual-phase system

Initial testing of traditional single-phase and proposed dual-phase systems was carried out in vitro by using the unlabeled reporter ASO and Nile Blue as a visualization agent [26]. One milliliter of low-melt agarose at 1.5% w/v in 0.25 × Tris Acetate EDTA (TAE) was used to model a target tissue. The agarose was directly cast into an acetyl homo polymer resin-based cup, which is the same cup that will be used in vivo. Once solidified, the cup is placed in a bath with a platinum-receiving electrode (+) submerged in the trial buffer. The cup is then filled with the test solution(s), and a platinum delivery electrode (−, for nucleic acids) is added. The electrodes were then attached to a power supply, and the test was conducted with a constant direct current of 2.0 mA (1.9 mA/cm2) for 6 min. The gels were removed from the cup and imaged together. The distance and density of the band in the gel were grossly compared for the different buffers and conditions tested.

Iontophoretic delivery of reporter ASOs into the cornea

To determine the threshold for delivery, a series of treatments with increasing currents was tested. First, in ex vivo intact corneas, and then in ex vivo excimer wounded rabbit corneas were used to model two different situations. First, frozen whole rabbit globes (Pel-Freez, LLC., Rogers, AR) were thawed. For the injury model, a central wound was created by using an excimer laser that was set to phototherapeutic keratectomy (PTK) mode (6.0 mm diameter, 125 μm depth, Fig. 3A). A platinum loop electrode was placed on a block of polystyrene and covered with buffer-soaked gauze. A thawed intact eye, or injured eye, was immobilized with dissection pins through the residual conjunctiva or muscles (Fig. 3B). The cup and delivery electrode were placed on top and held in place before buffer and drug solution loading. Next, 1.0 mL of HEPES buffer was added; then, 250 μL of a solution of 15% sucrose and ASO was added. The ASO/sucrose solution was added with a pipette with the tip as close to the tissue surface as possible to minimize mixing.

FIG. 3.

The ex vivo rabbit eye setup. (A) A typical phototherapeutic keratectomy wound in the center of an ex vivo cornea, 6.0 mm in diameter, 125 μm deep. (B) For both the intact and wounded models, the apparatus was the same.

For the intact cornea studies, 80 μg of the reporter ASO was used whereas160 μg of the 5-FAM ASO was used for the injured corneas. The eyes were subjected to iontophoresis for 5 min by using currents of 1.5, 2.0, 3.0, 4.0, or 5.0 mA for the intact corneas and 0.0, 1.0, 2.0, or 3.0 mA for the injured corneas. All corneas were fixed overnight. The intact corneas were paraffin embedded and sectioned, whereas the injured corneas were cryoprotected and finally embedded in OCT for cryosectioning.

The paraffin-embedded sections were stained by using a modification of a previously reported protocol for this ASO [27] by using an alkaline phosphate system (Vector Labs, Burlingame, CA) with a red chromogenic and fluorescent substrate (Vector Labs). The sections from the intact corneas were counterstained with hematoxylin and permanently mounted. The frozen sections were mounted with DAPI containing medium, and the 5-FAM ASO was observed by direct fluorescence microscopy. All micrographs from each group were obtained by using the same imaging parameters, allowing relative quantitative comparisons among the micrographs.

To quantify the number of cells transfected by this method, nonviable, intact ex vivo corneas were treated with 80 μg of 5-FAM ASO for 5 min at 4.0 mA (n = 4). An 8.0 mm biopsy punch was used to harvest the central cornea. The corneas were briefly fixed in 10% neutral buffer formalin for 30 min. The epithelium was then separated from the stroma by using EDTA as reported elsewhere [28]. The endothelium was collected by pealing of Descemet's membrane. Naïve corneas were similarly processed to serve as negative controls. The epithelium, stroma, and endothelium were then separately subjected to Trypsin digestion overnight at 4°C in preparation for fluorescence-assisted cell sorting (FACS) analysis. Of note, this process failed to separate the stromal tissue, and, therefore, the stroma was not analyzed in this manner. After trypsin digestion, the cells were re-suspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) with 0.5% Triton X100 to permeabilize the cells. Propidium iodide (PI) was added to the cell suspensions as per the manufacturer's instructions (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) to directly label the cells' nuclei.

The cells were then analyzed on a BD FACSCanto II at the McKnight Brain Institute (Gainesville, FL). Briefly, for each cell layer, the negative controls were subjected to a test run. The cells were primarily gated by PI signals to prevent false positives due to ASO+ aggregates, and secondarily, the green fluorescence channel was set just above the autofluorescence signal in the controls for each cell layer. The controls and replicated treatment samples were then analyzed with this tissue-specific gate. Separately, additional corneas were processed similarly, but each layer was formalin fixed and mounted with DAPI-containing media for confocal microscopic examination.

Ex vivo testing of intact mouse skin and cornea

Due to the reduced tissue size, another cup was used for the mouse cadaver experiments. A micro-spin resin column was used with the buffer loaded on top, and the delivery solution into the nipple below. Care was given to reduce or eliminate all bubbles between the two phases. The delivery electrode was placed in the upper reservoir whereas the receiving electrode was wrapped in buffer-soaked gauze and attached to the ear (for the eye) or the leg (for the foot). The delivery conditions were tested at 5.0 mA for 5.0 min in both tissues. On completion, the tissues were imaged with a digital SLR camera with macro flash and lens. The macro flash was filtered with cobalt blue gels to excite the 5-FAM, and the lens filtered the blue light with a deep yellow filter. The shutter speed was chosen to enable the ambient lighting to contribute to the image (yellow background).

Ex vivo testing of porcine skin

The conditions used for all of the deliveries into the porcine skin were the same as was done for the intact cornea, except that the current was set to 4.0 mA and the treatment duration was 10 min. Four different scenarios were tested. The intact highly keratinized plantar skin and intact apical shaved skin were tested as were the debrided plantar surface and a surgical incision in the apical skin.

In vivo testing of intact rabbit corneas

All of the rabbits used here were treated in a manner that was consistent with the ARVO Statement for the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research. A small-scale experiment was conducted to determine whether the ex vivo delivery into intact corneas could be repeated in vivo. The corneas were dosed with a 1:1 mixture of the nuclease-resistant reporter ASO and the nuclease-labile 5-FAM ASO. Iontophoresis was performed by using a current of 4.0 mA for 5 min; on completion, the solution was aspirated out of the cup. The corneas were immediately observed and imaged after delivery by using the same camera as described earlier, but this time without contribution of ambient light (black background). Corneas were collected immediately (0 h) or 24 h later and fixed in neutral buffered formalin for paraffin embedding, sectioning, and immunohistochemical staining as described earlier, but they were not counterstained with hematoxylin. The corneas were imaged for green fluorescence (nuclease-labile ASO) and red fluorescence (nuclease-resistant ASO). All sections were counterstained with DAPI.

Tolerability of iontophoresed ASOs in healing corneas

To establish whether the iontophoresis and the ASOs were well tolerated, we conducted some preliminary experiments measuring the effects of treatments on the acute phase of corneal wound healing by using the early phases of our previously reported model [29], including after re-epithelialization by daily fluorescein staining and macrophotography, and corneal edema via daily pachymetry measurements.

A total of seven rabbits received bi-lateral central corneal wounds and were treated with iontophoretically delivered ISIS 124189 (CTGF ASO) [25] in one eye and a universal control ISIS 29848 (Control ASO) [25] in the contralateral eye. An ASO dose of 0.45 mg in 500 μL of 15% sucrose was used for both treatment and control ASOs. As described earlier, iontophoresis was performed by using a current of 4.0 mA for 5 min; on completion, the solution was aspirated out of the cup. An additional three rabbits received the same wound in one eye and no further intervention. To understand the source of edema that was observed immediately after iontophoresis, six additional rabbits received the same bi-lateral wounds as described earlier. One eye received iontophoresis with only the 15% sucrose vehicle to control for electro-osmotic flow of water, and the other received CTGF ASO. The corneal thickness was measured both before and after excimer laser PTK and then again immediately after iontophoresis.

Statistical assessment of CTGF upregulation in injured corneas

Using the same in vivo injury model described earlier, both corneas from eight total rabbits were injured. The corneas from four rabbits were harvested on day 1 and 4 more were harvested on day 2 postinjury, and they were processed and analyzed for CTGF mRNA content in the stroma and epithelium as has been previously reported [30]. The mRNA content between days 1 and 2 was internally normalized by using the lowest quantity sample. The values were then plotted to visualize the distribution of CTGF quantities among replicate corneas. A pooled, one-tailed, lognormal Student's t-test was chosen [31] and supported by the known fact of CTGF upregulation in the stroma between days 1 and 2 [30].

Efficacy of iontophoresed anti-CTGF ASOs in healing corneas

Using the same model described earlier, 12 rabbits were bi-laterally injured and dosed with anti-CTGF in one eye and control ASO in the other. Six rabbits were euthanized at day 7 postinjury, and the remaining six were euthanized at day 14. The corneas were collected, and an 8 mm biopsy was used to collect the wound. The corneal button was immediately snap frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored in liquid nitrogen until it was assayed.

CTGF quantification via ELISA

The snap-frozen corneal buttons were thawed on ice; then, they were individually removed from their storage tubes, diced, placed in a 1.5 mL tube with 600 μL of extraction buffer (PBS pH 7.4 + 0.1% Triton X100, 5 mM EDTA, 2 mM PMSF, 0.24 mg/mL levamisole), and ground with a dounce homogenizer. Next, the base of the tube was submerged in iced saline and the homogenate and remaining tissue were subjected to ultrasonication. The homogenate was cleared by centrifugation, and the supernatant was transferred to a fresh tube. A portion of the supernatant was aliquoted separately for total protein quantification via BCA Assay (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Rockford, IL) by using the manufacturer's instructions.

The total extractable CTGF was measured via a sandwich ELISA in a 96-well plate. Briefly, the wells were coated with 50 μL of 2 μg/mL polyclonal anti-CTGF antibody (C7978-25C; US Biological, Inc., Swampscott, MA) in 0.1 M carbonate buffer (pH 9.5) overnight at 4°C. The wells were blocked with 300 μL per well of SuperBlock TBS (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Rockford, IL) as directed. Diluted SuperBlock (1/10th into TBS) was used as the reagent dilutent. Two replicate wells per sample (50 μL/well) were plated. A standard curve was plated in duplicate by using recombinant human CTGF (C7978-25R; US Biological, Inc.) at concentrations of 400, 200, 100, 50, 25, 12.5, 6.25, and 0.0 ng/mL. The plate was sealed and incubated for 1 h at 30°C. The plate was then washed three times with 300 μL/well of tris buffered saline with 0.05% (v/v) Tween 20 (TBST). Fifty microliters of 200 ng/mL biotinylated anti-CTGF probe antibody (C7978-25D; US Biological, Inc.) was applied to each well, sealed, and incubated at 30°C for 1 h. The plate was then washed as described earlier. The plate was finally incubated with 1:10,000 streptavidin-alkaline phosphatase (Zymed, Inc., Carlsbad, CA) at 30°C for 1 h. The plate was washed four times with 300 μL/well with TBST, and the plate was slapped dry. The ELISA was developed with PNPP in basic ethanolamine (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Rockford, IL). The plate was continuously monitored, with the absorbance at 450 nm being measured every 10 min for an hour. The CTGF values were normalized via the BCA results and represented as ng CTGF/mg of BSA equivalent units.

Results

The first experiments sought to determine the anticipated relative delivery of ASOs in different buffers in single- and new dual-phase arrangements (Fig. 4). In all cases, the lower the ionic strength, the better the delivery for the single phase, with no visibly detectable delivery when PBS was used in the single-phase configuration, a faint band with the TAE, and a very dense band with the ddh2O. The dual-phase arrangement improved delivery in all cases. These results support the approach of using a buffer to mitigate electrolysis and a separate less conductive drug phase to bring the drug closer to the target tissue and focus on the electromotive force. These results indicated the need for a buffer that was both better for drug delivery than PBS and nonirritating on the ocular surface, such as the Tris and EDTA in TAE. A 25 mM HEPES buffer was chosen (pH 6.8 for the delivery chamber and 7.9 for the receiving electrode) and was predicted to provide an adequate buffering capacity based on Faraday's Electrochemical Law and the Henderson-Hasselbalch equation. This buffer was tested in the same manner as the others and performed adequately (not shown).

FIG. 4.

In vitro testing of single- versus dual-phase arrangements. The graphic depicts the gross arrangement (not to scale) of the single- and dual-phase systems. PBS, phosphate-buffered saline; TAE, Tris Acetate EDTA.

Ex vivo testing of intact rabbit corneas

The gel tested to date is more porous than the cornea and is expected to have different electrical conductivity properties. To determine the current that would generate an adequate electromotive force on the drug to penetrate the intact cornea, we tested the delivery conditions in ex vivo rabbit eyes (Fig. 5). We found that there was no substantial penetration into the epithelium until 2.0 mA. A current of 3.0 mA had some stromal penetration whereas 4.0 and 5.0 had very good penetration. The corneas subjected to 5.0 mA began to show some signs of epithelial damage, though we were unable to control for tissue age or other possible causes as well. When we stained the tissues via immunohistochemical staining for the reporter ASO, the amount of background staining on the slide was proportional to the amount of ASO staining in the tissue. We believe that this was due to abundant ASO in the tissue, which was not adequately fixed to the tissue and spilled onto the slide during the initial rehydration and/or other prestaining steps.

FIG. 5.

Ex vivo results in intact rabbit corneas. The pink on the background is believed to be excess oligonucleotide, since it was not stained in the control (subset panels at the bottom) and the degree of staining was roughly consistent with the amount of oligonucleotide in the stroma (none was seen for the 1.5, 2.0, or 3.0 mA samples). The black boxes roughly correlate to the higher magnification fields above them. The scale bars represent 100 μm.

Photographs of the intact corneas treated with the 5-FAM ASO show similar areas of coverage, but with differing patterns of delivery (Fig. 6A). By confocal microscopy, the same pattern was seen for both the epithelium and stroma, where most cells had some evidence of ASO, but the cell-to-cell amount varied (Fig. 6B). FACS analysis revealed no detectable 5-FAM ASO in any of the endothelia tested, but an average of 96.8% of epithelial cells were transfected. This finding is consistent with the results seen in Fig. 5, where only the epithelium and anterior stroma had ASOs.

FIG. 6.

Quantifying the number of ASO+ Cells. (A) Macrophotographs of postdelivery fluorescence with the epithelial cell transfection rates noted. (B) Confocal micrographs of whole mounted epithelium and stroma. (C) The gating scheme used for the fluorescence-assisted cell sorting analysis. ASO, antisense oligonucleotide.

Ex vivo testing of excimer-ablated rabbit corneas

For some of our models, we anticipate delivering oligonucleotides into wounded corneas, so we performed another ex vivo experiment to determine whether a lower current would be adequate for delivery (Fig. 7). In the wounded ex vivo corneas, topical delivery of the labeled ASO (0.0 mA for 5 min) resulted in no detectable delivery. A delivery current of 1.0 mA for 5 min resulted in trace amounts of green fluorescence. For current values of 2.0 and 3.0 mA, the epithelium at the wound margin and the anterior stroma possessed high levels of green fluorescence that were homogenously distributed in an electrophoretic gel-like band. Both the penetration depth and intensity of green fluorescence were the highest in the 3.0 mA-treated cornea. Also apparent is that the progress through the peripheral epithelium did slow the progression of the ASO band.

FIG. 7.

Ex vivo results in an excimer-ablated rabbit cornea. The scale bars represent 75 μm. Ep, epithelium; Str, stroma; En, endothelium.

Ex vivo testing of intact mouse skin and cornea

Our initial success in our primary model prompted us to test whether we could also deliver the labeled ASO into a secondary model: the cornea and skin of ex vivo mice (Fig. 8). The initial delivery into the plantar surface of a mouse cadaver evidenced good penetration and distribution, but it may have disrupted the stratum corneum and may have resulted in a blister-like structure. Very good delivery was also seen in the cornea, but with no apparent damage.

FIG. 8.

Ex vivo results in an intact mouse skin and cornea. The 5-FAM ASO as seen before, during, and after delivery by macrophotography and fluorescence microscopy. SC, stratum corneum; EPI, epidermis; Derm, dermis; Epi, epithelium; Str, stroma; Endo, endothelium.

Ex vivo testing of intact pig skin

Using the same setup developed for the eye, we sought to test a more relevant model for skin delivery by using a porcine trotter obtained from an abattoir. Attempts were made to deliver the labeled ASO into the thick plantar surface and the apical skin surface (Fig. 9). Nearly no delivery was seen on the plantar surface, and no penetration was observed in sections of the dosed tissue. On the apical skin surface, punctate coverage on the skin was grossly observed and very good penetration was observed in sections. The source/localization of the punctate pattern has not yet been positively identified to correlate with a specific skin structural elements, glands, or micro-organs.

FIG. 9.

Ex vivo results in an intact pig skin. Testing delivery on regular and highly keratinized pig skin.

Ex vivo testing of damaged pig skin

Similar to our initial development in the rabbit cornea, some skin models include delivery into injured or denuded skin (Fig. 10). The plantar stratum corneum and epidermis were debrided from the trotter's plantar surface, whereas a surgical incision with interrupted sutures was created on the apical surface. The plantar dermis was well covered and had good penetration. The skin surrounding the incision recapitulated the previously observed punctate pattern, whereas the ASO was also delivered into the tissue faces in the incision.

FIG. 10.

Ex vivo results in a disrupted pig skin. A model for scenarios with the underlying dermis as the drug target and debridement being acceptable (chronic wounds). Also, delivery into a sutured surgical incision.

In vivo testing of intact rabbit corneas

We next sought to determine whether the results from the intact ex vivo trials could be achieved in vivo. We also sought to determine, qualitatively, whether the protected ASO would remain for at least 24 h by dosing the eyes with a mixture of the labeled ASO for immediate visualization and the protected reporter ASO for later immunohistochemical staining (Fig. 11). The delivery proceeded without any chemical or thermal burns. The yellow of the 5-FAM was immediately visible and fluorescently unambiguous with good central coverage and some evidence of a nearly overlapping punctate pattern at the periphery. A day later, no labile ASO was detected and a highly punctate pattern from the epithelium, though until about midway into the stroma, was present. The more homogenous staining at the posterior cornea is in a pattern that is consistent with edge effects, since it is confined to regions of tissue pockets and wrinkles.

FIG. 11.

In vivo delivery of ASOs into an intact cornea. The 5-FAM ASO could be immediately visualized either in native light (yellow) or via blue-excited green fluorescence. Green is nuclease-labile ASO, whereas red is nuclease-resistant ASO detected by immunostaining. All corneal sections are depicted as epithelium up, endothelium down. The scale bars represent 100 μm. The 1° antibody withheld control was equivalently exposed, but it had no strong substrate development (not shown).

In vivo testing of excimer-ablated rabbit corneas

Next, we sought to test the acute wound-healing response of the injured cornea to iontophoretically deliver ASOs by using two different ASOs. As described earlier, we saw no evidence of chemical or thermal burns. Corneas that received iontophoresis with an ASO, but not iontophoresis of the vehicle, presented with immediate edema (Fig. 12A). That immediate swelling appeared to resolve to normal postinjury levels for one ASO, but not the control (Fig. 12B). The wound closure appeared graphically slightly slower than the nonintervention control, but it was not statistically significant (Fig. 12C), and since all of the corneas were healed by days 3 or 4, the closures were not clinically significantly different for this model.

FIG. 12.

The early physiological response to CTGF ASO delivered by iontophoresis. (A) Edema in corneas treated with iontophoresis of an ASO versus the carrier solution. (B) The postsurgery edema time course. (C) The epithelial closure time course. Note: (B, C) are from the same group of corneas. For the ASO treated, n = 7; for the nonintervention (No Tx), n = 3. (D) A typical corneal wound closure time course where closure by days 3 or 4 is typical.

Efficacy of iontophoresed anti-CTGF ASOs in healing corneas

In the final experiments, we sought to determine the nature of CTGF upregulation and the ability for an iontophoresed anti-CTGF ASO to reduce CTGF protein levels in wounded rabbit corneas. Previous data have revealed an increase in CTGF protein levels in wounded rabbit corneas from day 1 to 2, with a high degree of variability in the stroma [30,32,33]. When internally normalized values were plotted, the data appeared to be highly asymmetrically distributed about the mean, with most grouping together below the mean with a single outlier (Fig. 13A, C) well above the mean. Such apparent outliers in biological data can often be due to the data being non-Gaussian, and instead being a lognormal distribution [31]. A Student's t-test on the nontransformed data was not able to accurately detect the known differences between days 1 and 2 (Fig. 13A), whereas the t-test on the log10 normalized data could do so (Fig. 13B). The nontransformed CTGF protein values trended toward significance (Fig. 13C, P = 0.07) on day 7, whereas the transformed data reached statistical significance (Fig. 13D, P < 0.05). Neither approach reached significance for the day 14 values.

FIG. 13.

The statistical distribution of CTGF in healing corneas and CTGF reduction by an ASO. (A) The internally normalized levels of CTGF mRNA in the epithelium and stroma 1 and 2 days after injury. (B) The log10-transformed mRNA data. The red circle represents the potential “outlier,” whereas the green represents the otherwise closely aggregated samples. (C) The nontransformed results from the CTGF ELISA and (D) the log10-transformed ELISA data.

Discussion

Both the use of electromechanical force for analysis of DNA (agarose gel) and the purification of labeled oligonucleotides (SDS-PAGE) of DNA are well established and are known to not modify DNA. We showed that a new design of these tools, informed by simple electromechanics, has the ability to buffer the electrolytic byproducts of iontophoresis without sacrificing ASO delivery by using a simple dual-phase system. We believe that the combined effects of separating the buffer and the drug, and moving the drug closer to the intended target were the major changes that enabled the good delivery results reported here on a time scale of only 5 to 10 min, depending on the tissue. We believe that these results support the simple theoretical explanation based on electromechanics, and we believe that the theory can be used to further improve and optimize delivery for a variety of tissues.

One point of inconsistency was in the distribution of the ASO in intact skin versus the cornea. The intact skin, unlike the cornea, contains heterogeneous features, including hair follicles and a variety of glands. In principle, there does not appear to be an expectation that manipulating the iontophoretic conditions will adequately address this difference. To the extent that a more homogenous distribution across the treated skin is necessary, chemical modifications to the skin, vehicle, or ASO may be needed. Otherwise, the punctate pattern seen on the epidermal skin should be taken into account if it is the target tissue. A second point of inconsistency was apparent in the amount of ASO delivered to each cell. The FACS analysis indicated that an average 96.8% of cells were transfected, whereas both the photographs and micrographic analysis evidenced a varying amount of ASO per cell.

From the outset of this project, we anticipated that the concentration of the ASO delivered into the tissue would be theoretically greater than an injection, since the bulkiness of the solvent would be limiting. We also believed that the tissue disruption and damage due to the injection bleb would be completely obviated. The blister-like structure seen in the mouse cadaver paw may or may not have been a thermal injury, and it may be evidence that the tissue still has an injection-like bleb. In the cornea, where there was no blister-like structure, there was immediate edema. Electro-osmotic flow (as is used in reverse osmosis) may have explained the immediate edema, whereas the control without any deliverable ions did not present with elevated edema, suggesting that the bulk of the effect was due to the osmotic pressure of the delivered ASO. This same phenomenon would be expected to be possible even in a cadaver, since it is a purely physical chemistry effect, with the water being drawn to locations with higher total solute concentration. Interestingly, though less specific than visible labels, the edema might be utilizable as a metric for delivery success.

The consequences to tissue spread and uptake of the edema are not known, and may very well increase the spread, at the cost of uptake (via dilution). However, in our results so far, the ASOs do not appear to be driven around cells (ie, there are no gaps in fluorescence corresponding to cell membranes). Instead, it appears that the process of iontophoresis may directly drive some ASOs into the cells at the time of delivery. Additional experimentation is required to more conclusively demonstrate that the mechanism is direct delivery, later uptake, or a combination of the two.

The delivery into the injured cornea evidenced a very electrophoresis-like band pattern. The band thickness and final location in the tissue is an unanticipated parameter that must be controlled. For instance, if our targeted cells were only the most apical of the stromal fibroblasts, they may have been passed over by the band in the 3.0 mA control. We anticipate that oligonucleotide concentration and drug solution volume are likely to affect the drug band shape. However, delivery current and dose duration will certainly control the band's penetration depth. Additional work understanding how to control the band's shape and ultimate penetration depth is crucial for efficacious targeting of the cells of interest.

The lack of results in the plantar surface may be due to the delivery conditions chosen, since they were selected for their ability to deliver into the more fragile cornea. We do not know at present whether there are a priori principles that would deem a tissue impenetrable by iontophoresis. It is possible that some tissues would need pretreatment, if there was an identifiable impediment to delivery. Additional work with the more resilient tissues such as the plantar surface of the foot would be necessary to determine if this is the case.

In seeking to test the toleration of the iontophoresis and ASOs by the cornea, we found no effect on re-epithelialization and some effect on edema. Although we had previously published a reduction in re-epithelialization in the absence of CTGF [30], we did not find the same result here. We anticipate that this was due to the fact that we did not dose the limbal epithelial cells that are known to be the drivers of epithelial wound closure [34,35]. In so doing, we may have avoided the effect on re-epithelialization that was present in the CTGF knockout mouse model. The effect seen in the postsurgical edema may be explained by the yet-to-be understood effects of our previous finding of CTGF expression in the endothelium [30]. Although the effect seen is plausible, it is not currently supported by our data given that no ASO was detected in the endothelium either by direct staining for it (Fig. 5) or by FACS analysis.

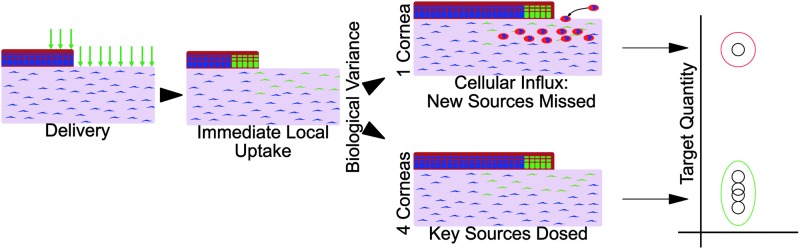

In seeking to determine whether iontophoretically delivered ASOs can reduce target gene protein levels, we found the same high degree of biological variance that we had previously seen in immunofluorescent staining results [30]. Although the statistical literature suggests that many biological variables follow a lognormal distribution, they do not address the reason. In our results, approximately one out of five corneas had extremely high levels, regardless of treatment, till day 7. Drawing on our previously reported data, this difference may be attributed to the highly variable occurrence of neutrophil influx into the cornea, especially since those neutrophils stained highly positive for CTGF [30]. These results highlight a crucial limitation of the method described here, in that only the cells present at the time of treatment can be affected. Cells such as neutrophils, which invade the tissue ∼1 to 2 days later, will be wholly unaffected (Fig. 14). Precise knowledge of all cellular sources of the RNAi target, and their timing and localization is essential for the design and implementation of RNAi dosing methods and strategies. The single-dose approach tested here would be insufficient, and it would require follow-up doses to address neutrophil-sourced CTGF.

FIG. 14.

The hypothetical source for biological variance and its consequences for RNA interference therapies. After a single dose, ASOs are found within the dosed cells. Afterward, stochastic events can lead to a splitting of the study population. In healing corneas, an influx of CTGF+ neutrophils has been observed and would not be affected by the initial dose. The anticipated consequences of such an occurrence are consistent with the observed results in both CTGF mRNA and protein in healing corneas.

Our work reported here shows that ASOs can be delivered into cells, they can persist for at least 24 h, and the cornea can tolerate the delivery mechanism and the delivered ASO. Furthermore, we have shown that the effects of a single dose of an anti-CTGF ASO can result in lower CTGF concentrations in healing corneas for as many as 7 days. A substantial amount of work remains to better design dosing levels, and especially dose timing to ensure that cells arriving into tissues later in the wound-healing process are also treated. The success of any drug development program is highly contingent on the model used, knowledge of the source(s) of the targeted protein, and it is crucial to understand the potential sources of biological variance. Although we do not believe that the anti-CTGF results presented here are adequate to support its use as a therapy, we believe that in sharing our progress on iontophoretic delivery and a theoretical basis for understanding how it works, others seeking to target a wide variety of RNAi targets in either the skin or ocular surface could use this approach and the framework of understanding to support their continued research on RNAi as a research tool or possible therapeutic modality.

We began this research to determine whether injections, which are painful in the skin and severely difficult, if not impossible, in the cornea, could be avoided. Conceptually, we also believe that the selective delivery of the oligonucleotides could possibly improve the volume of tissue coverage by obviating the transfer of bulk solvent. Although the initial literature reports suggested that a 90 min delivery was necessary, we believed that if we could improve on the dosing time, iontophoresis would enable an interesting new approach to nucleotide-based therapeutics. By applying some basic concepts from simple mechanics and electromechanics, we believe that our data support the fact that a dual-phase iontophoresis design enables a new approach to efficacious delivery of oligonucleotide-based drugs.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by R01 Regulation of Stromal Wound Healing (R01-EY05587); NEI T32 Vision Training grant (T32-EY007132); and NEI Vision Core (EY021721); it was also supported in part by an unrestricted grant from Research to Prevent Blindness.

Author Disclosure Statement

D.J.G.: Patent: U.S. 8,838,229, issued: yes, licensed: no, royalties: no, Grant: Trainee on a NEI T32 Vision Training grant (T32-EY007132). S.S.T.: Patent: U.S. 8,838,229, issued: yes, licensed: no, royalties: no, Grant: Unrestricted grant from Research to Prevent Blindness. G.S.S.: Patent: U.S. 8,838,229, issued: yes, licensed: no, royalties: no, Grant: PI on a R01 Regulation of Stromal Wound Healing (R01-EY05587). All three authors are co-inventors on a patent (U.S. 8,838,229), which has been issued, but has neither been licensed nor generated any royalties.

References

- 1.Sriram S, Robinson P, Pi L, Lewin AS. and Schultz G. (2013). Triple combination of siRNAs targeting TGFbeta1, TGFbetaR2, and CTGF enhances reduction of collagen I and smooth muscle actin in corneal fibroblasts. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 54:8214–8223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sisco M, Kryger ZB, O'Shaughnessy KD, Kim PS, Schultz GS, Ding XZ, Roy NK, Dean NM. and Mustoe TA. (2008). Antisense inhibition of connective tissue growth factor (CTGF/CCN2) mRNA limits hypertrophic scarring without affecting wound healing in vivo. Wound Repair Regen 16:661–673 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rae JL. and Blankenship JE. (1973). Bioelectric measurements in the frog lens. Exp Eye Res 15:209–217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Araie M. and Maurice DM. (1985). A reevaluation of corneal endothelial permeability to fluorescein. Exp Eye Res 41:383–390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Koretz JF, Bertasso AM, Neider MW, True-Gabelt BA. and Kaufman PL. (1987). Slit-lamp studies of the rhesus monkey eye: II. Changes in crystalline lens shape, thickness and position during accommodation and aging. Exp Eye Res 45:317–326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tsukahara Y. and Maurice DM. (1995). Local pressure effects on vitreous kinetics. Exp Eye Res 60:563–573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ostrin LA. and Glasser A. (2007). Edinger-Westphal and pharmacologically stimulated accommodative refractive changes and lens and ciliary process movements in rhesus monkeys. Exp Eye Res 84:302–313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Behar-Cohen FF, Parel JM, Pouliquen Y, Thillaye-Goldenberg B, Goureau O, Heydolph S, Courtois Y. and De Kozak Y. (1997). Iontophoresis of dexamethasone in the treatment of endotoxin-induced-uveitis in rats. Exp Eye Res 65:533–545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Halhal M, Renard G, Courtois Y, BenEzra D. and Behar-Cohen F. (2004). Iontophoresis: from the lab to the bed side. Exp Eye Res 78:751–757 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eljarrat-Binstock E, Raiskup F, Stepensky D, Domb AJ. and Frucht-Pery J. (2004). Delivery of gentamicin to the rabbit eye by drug-loaded hydrogel iontophoresis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 45:2543–2548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Frucht-Pery J, Mechoulam H, Siganos CS, Ever-Hadani P, Shapiro M. and Domb A. (2004). Iontophoresis-gentamicin delivery into the rabbit cornea, using a hydrogel delivery probe. Exp Eye Res 78:745–749 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Novruzlu S, Turkcu UO, Kvrak I, Kvrak S, Yuksel E, Deniz NG, Bilgihan A. and Bilgihan K. (2015). Can Riboflavin penetrate stroma without disrupting integrity of corneal epithelium in rabbits? Iontophoresis and ultraperformance liquid chromatography with electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry. Cornea 34:932–936 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mastropasqua L, Nubile M, Calienno R, Mattei PA, Pedrotti E, Salgari N, Mastropasqua R. and Lanzini M. (2014). Corneal cross-linking: intrastromal riboflavin concentration in iontophoresis-assisted imbibition versus traditional and transepithelial techniques. Am J Ophthalmol 157:623–630.e621 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gore DM, O'Brart DP, French P, Dunsby C. and Allan BD. (2015). A comparison of different corneal iontophoresis protocols for promoting transepithelial riboflavin penetration. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 56:7908–7914 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cassagne M, Laurent C, Rodrigues M, Galinier A, Spoerl E, Galiacy SD, Soler V, Fournie P. and Malecaze F. (2016). Iontophoresis transcorneal delivery technique for transepithelial corneal collagen crosslinking with riboflavin in a rabbit model. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 57:594–603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bikbova G. and Bikbov M. (2014). Transepithelial corneal collagen cross-linking by iontophoresis of riboflavin. Acta Ophthalmol 92:e30–e34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Arboleda A, Kowalczuk L, Savoldelli M, Klein C, Ladraa S, Naud MC, Aguilar MC, Parel JM. and Behar-Cohen F. (2014). Evaluating in vivo delivery of riboflavin with coulomb-controlled iontophoresis for corneal collagen cross-linking: a pilot study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 55:2731–2738 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Berdugo M, Valamanesh F, Andrieu C, Klein C, Benezra D, Courtois Y. and Behar-Cohen F. (2003). Delivery of antisense oligonucleotide to the cornea by iontophoresis. Antisense Nucleic Acid Drug Dev 13:107–114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hao J, Li SK, Liu CY. and Kao WW. (2009). Electrically assisted delivery of macromolecules into the corneal epithelium. Exp Eye Res 89:934–941 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Molokhia SA, Jeong EK, Higuchi WI. and Li SK. (2009). Transscleral iontophoretic and intravitreal delivery of a macromolecule: study of ocular distribution in vivo and postmortem with MRI. Exp Eye Res 88:418–425 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Souied EH, Reid SN, Piri NI, Lerner LE, Nusinowitz S. and Farber DB. (2008). Non-invasive gene transfer by iontophoresis for therapy of an inherited retinal degeneration. Exp Eye Res 87:168–175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu JC. and Sun Y. (1994). Transdermal delivery of proteins and peptides by iontophoresis: development, challenges, and opportunities. In: Drugs and the Pharmaceutical Sciences: Drug Permeation Enhancement, Theory and Applications, 1st edn. Hsieh D, ed. Marcel Dekker, New York, NY, Vol. 62, pp 247–272 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hill JM, O'Callaghan RJ. and Hoben JA. (1993). In: Drugs and the Pharmaceutical Sciences: Ophthalmic Drug Delivery Systems, 1st edn. Mitra AK, ed. Marcel Dekker, New York, NY, Vol. 58, pp 331–354 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wong O. (1994). In Drugs and the Pharmaceutical Sciences: Drug Permeation Enhancement, Theory and Applications, 1st edn. Hsieh D, ed. Marcel Dekker, New York, NY, Vol. 62, pp 219–246 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Uchio K, Graham M, Dean NM, Rosenbaum J. and Desmouliere A. (2004). Down-regulation of connective tissue growth factor and type I collagen mRNA expression by connective tissue growth factor antisense oligonucleotide during experimental liver fibrosis. Wound Repair Regen 12:60–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Adkins S. and Burmeister M. (1996). Visualization of DNA in agarose gels as migrating colored bands: applications for preparative gels and educational demonstrations. Anal Biochem 240:17–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Butler M, Hayes CS, Chappell A, Murray SF, Yaksh TL. and Hua XY. (2005). Spinal distribution and metabolism of 2′-O-(2-methoxyethyl)-modified oligonucleotides after intrathecal administration in rats. Neuroscience 131:705–715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hattori T, Chauhan S, Lee H, Ueno H, Dana R, Kaplan D. and Saban D. (2011). Characterization of langerin-expressing dendritic cell subsets in the normal cornea. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 52:4598–4604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gibson DJ. and Schultz GS. (2013). A corneal scarring model. Methods Mol Biol 1037:277–298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gibson DJ, Pi L, Sriram S, Mao C, Petersen BE, Scott EW, Leask A. and Schultz GS. (2014). Conditional knockout of CTGF affects corneal wound healing. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 55:2062–2070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Motulsky H. (2014). Intuitive Biostatistics: A Nonmathematical Guide to Statistical Thinking, Third edn. Oxford University Press, New York [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yang YM, Wu XY. and Du LQ. (2006). [The role of connective tissue growth factor, transforming growth factor and Smad signaling pathway during corneal wound healing]. Zhonghua Yan Ke Za Zhi 42:918–924 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shi L, Chang Y, Yang Y, Zhang Y, Yu FS. and Wu X. (2012). Activation of JNK signaling mediates connective tissue growth factor expression and scar formation in corneal wound healing. PLoS One 7:e32128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kinoshita S, Friend J. and Thoft RA. (1981). Sex chromatin of donor corneal epithelium in rabbits. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 21:434–441 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Buck RC. (1985). Measurement of centripetal migration of normal corneal epithelial cells in the mouse. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 26:1296–1299 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]