Abstract

Background

There are few previous studies investigating the relationship of dental fear and anxiety (DFA) with dental pain among children and adolescents. To address this issue, we examined the literature published between November 1873 and May 2015 to evaluate the prevalence of DFA and dental pain among children and adolescents, and their relationships with age and sex.

Methods

We performed a broad search of the PubMed database using 3 combinations of the search terms dental fear, anxiety, and dental pain and prevalence. A large proportion of the identified articles could not be used for the review due to inadequate end points or measures, or because of poor study design. Thirty-two papers of acceptable quality were identified and reviewed.

Results

We found that the prevalence of DFA was estimated to be 10%, with a decrease in prevalence with age. It was more frequently seen in girls, and was related to dental pain.

Conclusions

We concluded that dental fear, anxiety, and pain are common, and several psychological factors are associated with their development. In order to better understand these relationships, further clinical evaluations and studies are required.

Keywords: Adolescent, Child, Dental Anxiety, Dental Fear, Pain, Prevalence

INTRODUCTION

Children's uncooperativeness in dentistry has been conceptualized in different ways. Dental fear (DF) and dental anxiety (DA) are used to denote early signs of dental phobia (DP): an excessive or unreasonable fear or anxiety with regard to the challenge/threat of dental examination and treatment, which influences daily living and results in prolonged avoidance of dental treatment [1]. Dental anxiety and fear (DFA) in children has been recognized in many countries as a public health dilemma [2], and has been studied at length. In the late 1960s, Norman Corah developed the Dental Anxiety Scale (DAS), providing an organizing principle to examine this issue [3]. Dental fear is a normal emotional reaction to one or more specific threatening stimuli within the dental situation, while DA denotes a state of apprehension that something dreadful will happen in relation to dental treatment, coupled with a sense of losing control. Dental phobia represents a severe type of DA and is characterized by marked and persistent anxiety in relation either to clearly discernible situations/objects (e.g., drilling, injections) or to dental situations in general [4]. Henry Lautch investigated whether these patients'fear was related to the nature and the characteristics of dental care [5], while Elliot Gale concluded that clinicians needed to assess the situation of the patient, rather than actual pain under any circumstances, when assessing DF [6]. Moore et al compared the overall demographic trends and their relation to the factors and degrees of DF [7].

Among other physical problems seen after birth and persisting into adolescence, toothache due to dental caries often begins in infant. Despite great progress in dental health through dentistry, most youths require dental treatment of various forms. However, teenagers, who are often immature psychologically and physically, can manifest a great fear of dental treatment. Holtzman et al found that, patients for fear of dental treatment missed appointments 3 times more than other patients. They did find that as age increased, fear and anxiety decreased, measured through physiological responses to critical reaction symptoms, such as patients'muscle tension when sitting in the dental chair; further, that younger women expressed more DF than older women, while men reporting DF was unrelated to age [8]. Similarly, many investigators have reported fear of dental treatment in children that may result in treatment management difficulties [9]. Behavior management problems are also related to dental factors, such as earlier negative treatment experiences [10,11], particularly injection, drilling, and extraction, which have been shown to carry the most negative emotional loads [12,13]. Furthermore, the dentist's attitude toward the pediatric patient is of vital importance for good treatment outcomes [14]. A study of children aged 5 to 11 years by Milgrom et al. [15] suggested that conditioning is an important contributor to DF in childhood and adolescence. Prevalence estimates of childhood DF vary considerably, from 3% to 43% in different populations [4]. However, there are few previous studies examining the relationship of DFA to dental pain among children and adolescents. Thus, the purpose of this study was to examine the literature regarding the prevalence of DFA associated with dental pain.

Materials And Methods

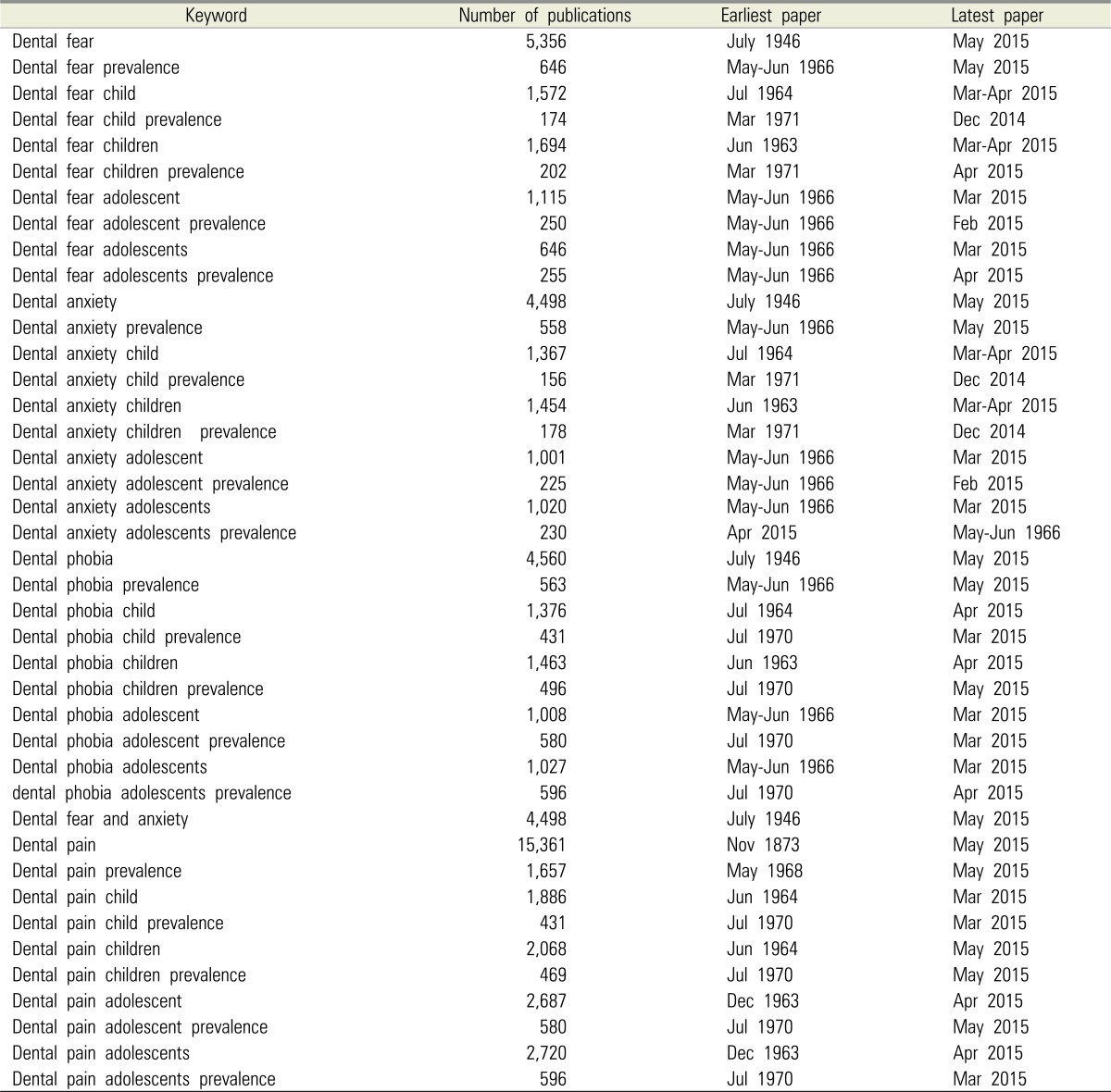

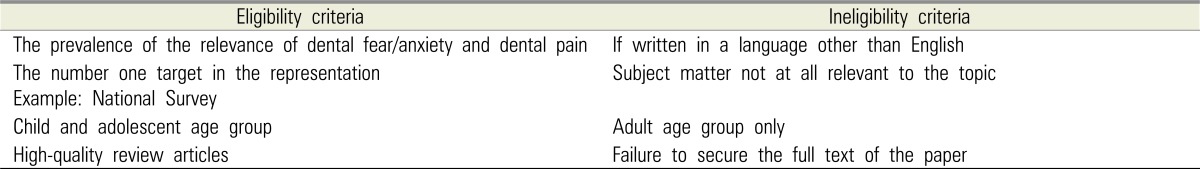

A broad search of the PubMed database was performed using 3 combinations of the following search terms: dental fear, anxiety, and dental pain and prevalence. The search was limited to publications in English that included children and adolescents aged 0 to 18 years. The cut-off date was the end of May 2015. The keywords used and the search results are shown in Table 1. Relevant publications were identified after reviewing the abstracts. Table 2 shows the eligibility and ineligibility criteria for this study.

Table 1. Keywords searched on Medline (late May 2015) and number of publications found.

Table 2. Eligibility and ineligibility criteria for the study.

RESULTS

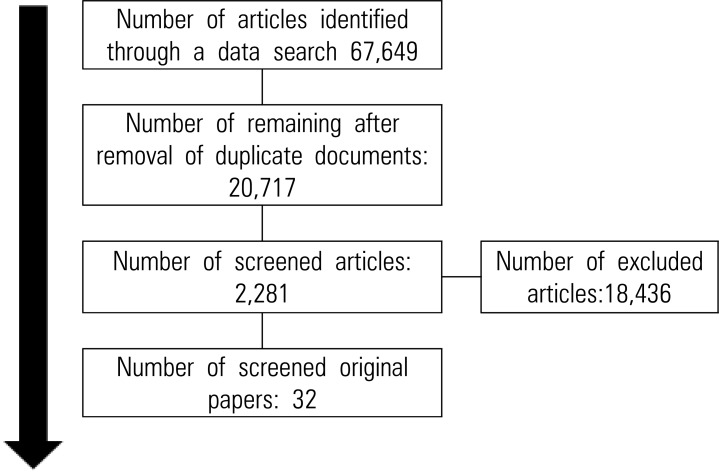

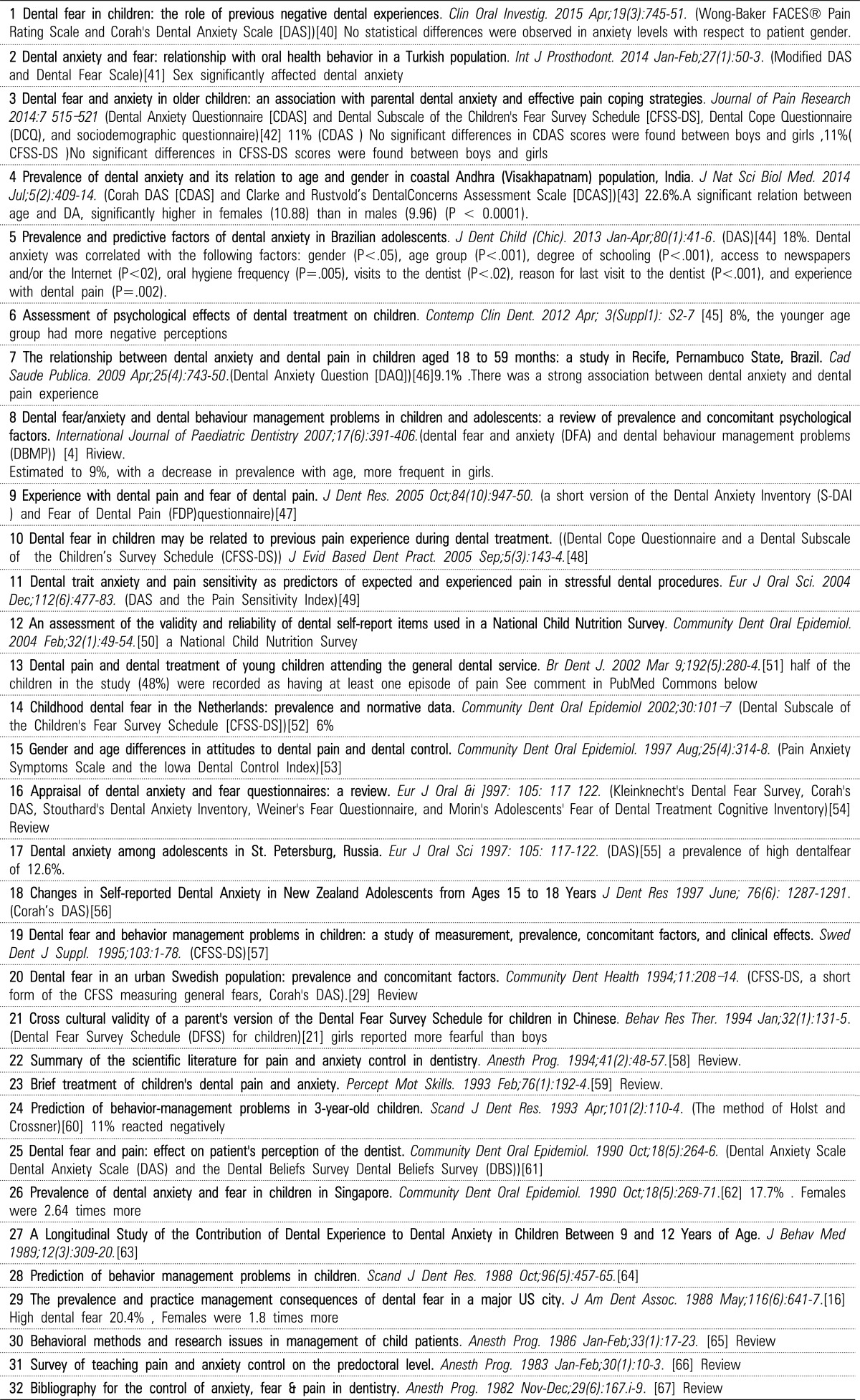

The literature selection process was performed as seen in Fig. 1. Combining the search terms dental fear, anxiety, and dental pain and prevalence, the number of screened articles was 2,281. Much work has been published on the prevalence of dental pain, but relatively little on the prevalence of DFA. Two separate researchers selected articles. However, a large proportion of the identified articles could not be used for the review due to inadequate end points and measures or poor study design. Finally, 32 relevant articles with acceptable end points were identified and retrieved (Table 3). After that, critical assessment was performed on each article, examining the prevalence of DFA and dental pain, with differences based on age and sex.

Fig. 1. The flow of the literature selection process.

Table 3. List of selected articles that used fear anxiety and pain measurement tools.

The included articles were published between 1982 and 2015; the number of individuals surveyed for DFA varied from 52 to 4505. The prevalenceof DFA was estimated at 10%, with a decrease in prevalence with age. Dental fear and DA was more frequently seen in girls, and was related to dental pain.

DISCUSSION

Fear or anxiety about dental treatment is very common. One study suggests that, in the US, more than 80% of the population fears dental treatment, and 20% avoids the dentist due to severe DF [16]. Avoiding dental treatment due to anxiety and fear exacerbates problems related to patients' oral health. Further, treating anxious patients tends to be both more difficult and more time-consuming. Because dental patients feel anxiety and fear associated with dental treatment, it has been vital for dentists to construct an environment that alleviates patient worries. Effective regulation of anxiety and pain is an essential element of dental care, allowing many patients, who previously could not be treated, to receive dental treatment, due to the extensive and various ways available to control anxiety and pain. In attempts to solve these problems, studies examining causes of DFA, as well as its prevalence, patient categories, and its impact on intra-oral and extra-oral environments and treatment plans have been conducted. However, the use of such methods in clinical situations is low due to lack of understanding, time constraints, and translation difficulties.

Dental anxiety and DF among both adults and children has been recognized as a problem area in clinical dentistry for many years, but only a small number of investigations have tried to depict the epidemiologic public health factors related to DF in countries and cultures other than Western Europe and North America. Approximately 10% to 20% of the adult population in the western industrialized world report high DA; most also report this reaction as having developed in childhood [17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25]. Although negative dental experiences are often cited as the major factor in the development of DA, very few studies have provided prevalence data. Prevalence estimates of childhood DF vary considerably, from 3% to 43% in different populations [2,15,26,27,28,29,30]. These differences in prevalence estimates may be due to several parameters, such as methodological or cultural variables, in the populations surveyed. For example, instruments used in these studies vary from behavioral rating scales to several forms of fear questionnaires, such as the DAS [3] and the Dental Subscale of the Children's Fear Survey Schedule [31]. Corah's DAS, published in 1969, consists of 4 questions with 5 answer alternatives for each [6] the scores may range from 4 (no anxiety) to 20 (high anxiety) [3]. The Dental Fear Survey (DFS), originally a 27-item self-assessment survey published by Kleinknecht et al. in 1973, was later revised to a 20-item version [32]. Two items focus on avoidance, 5 on self-perceived signs of physiological arousal, 12 on fear of specific dental situations and procedures, and 1 (item 20) on DF in general. Each question has 5 unimodal answer alternatives using an ordinal level of measurement. The summed scores may range from 20 (no fear) to 100 (terrified), but the DFS is primarily designed to detect the fear induced by the separate items.

In 1990, Weiner and Smehhan published the Fear Questionnaire (FQ), consisting of 2 parts [33]. Part A contains 16 five-point questions. Approximately one half of the list was similar to the Anticipated Anxiety Level Chart [34,35,36], with which commonly occurring general and dental fears were studied. Part B examines autonomic stress reactions in particular, with 18 five-point questions, of which 3questions deal with severe anxiety attacks. The answer alternatives are unimodal and are of the ordinal level of measurement. The 2 parts of the FQ contain 4 orthogonal, reliable factors. Four factor indices are computed, for "generalized (endogenous) fear," "dental specific fear," "endogenous anxiety symptoms," and "exogenous anxiety symptoms." The 4 scales show intercorrelation ranging from 0.21 to 0.52, and were therefore considered to be only modestly related [33]. In 1991, Gauthier et al. published the Adolescents' Fear of Dental Treatment Cognitive Inventory (AFDTCI), developed by Morin in 1987. The AFDTCI evaluates thoughts and ideas that an adolescent may experience during dental treatment. The questionnaire originally consisted of 42 questions with ordinal 1- to 5-point scales, but after assessment by 8 experts, it was reduced to 29 items. A test using adolescent subjects (n = 343) led to the removal of 6 more items, leaving 23 items in all. The scores on the AFDTCI may range from 23 (no fear) to 115 (high fear) [37].

Fear of pain was found to be the most important predictor of DA; issues of control were also related to DA. Therefore, it was predicted that gender and age differences would be reflected in attitudes toward pain and control. Childhood fears are often related to developmental changes in children, and the nature of fears prominent in a child's life also seems to depend on the child's age [38,39]. For a preschool-aged child, attachment and separation anxiety often play an important role, whereas at a later age (≥ 8 years), fear of bodily injury and social ostracization become more prominent. Most of these developmental age-appropriate fears decrease or disappear as children grow older, due to increased ego strength and cognitive ability development, thus providing children with adequate coping styles. Accordingly, from a developmental perspective, young children are expected to suffer some degree of fear when visiting the dentist for the first time, possibly due to being separated from a parent, not understanding the dental procedures, or associating these with other, age-appropriate fears. In most children, this fear will probably decrease after visiting the dentist more often and thereby becoming habituated to the dental situation. However, in a small subgroup of children, fear seems to persist into adulthood and become chronic. It has been suggested that patients need to have the attitude and desire to actively use these evaluation methods, rather than paying constant attention to the anxiety regarding dental care.

CONCLUSION

Dental fear, DA, and dental pain are common, and several psychological factors are associated with the development of these problems. The prevalence of DFA is estimated to affect 10% of the population, with a decrease in prevalence with age. We also found that DFA was more frequently seen in girls, and that it was related to dental pain. In order to better understand these relationships, further clinical evaluations and studies are required. Further research, using more appropriate methods, is needed to clarify the role of dental pain in the genesis of DFA.

Footnotes

Funding: The authors deny any conflicts of interest.

Declaration of interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th ed. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alvesalo I, Murtomaa H, Milgrom P, Honkanen A, Karjalainen M, Tay KM. The dental fear survey schedule: a study with Finnish children. Int J Paediatr Dent. 1993;3:193–198. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-263x.1993.tb00083.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Corah NL. Development of a dental anxiety scale. J Dent Res. 1969;48:596. doi: 10.1177/00220345690480041801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Klingberg G, Broberg AG. Dental fear/anxiety and dental behaviour management problems in children and adolescents: a review of prevalence and concomitant psychological factors. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2007;17:391–406. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-263X.2007.00872.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lautch H. Dental Phobia. Br J Psychiatry. 1971;119:151–158. doi: 10.1192/bjp.119.549.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gale EN. Fears of the dental situation. J Dent Res. 1972;51:964–966. doi: 10.1177/00220345720510044001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moore R, Birn H, Kirkegaard E, Brødsgaard I, Scheutz F. Prevalence and characteristics of dental anxiety in Danish adults. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1993;21:292–296. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1993.tb00777.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Holtzman JM, Berg RG, Mann J, Berkey DB. The relationship of age and gender to fear and anxiety in response to dental care. Spec Care Dentist. 1997;17:82–87. doi: 10.1111/j.1754-4505.1997.tb00873.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Holst A, Schroder U, Ek L, Hallonsten AL, Crossner CG. Prediction of behavior management problems in children. Scand J Dent Res. 1988;96:457–465. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.1988.tb01584.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wright GZ, Alpern GD, Leake JL. A crossvalidation of variables affecting children's cooperative behavior. J Can Dent Assoc (Tor) 1973;39:268–273. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Holst A, Crossner CG. Management of dental behavior problems. A 5-year follow-up. Swed Dent J. 1984;8:243–249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Holst A, Crossner CG. Direct ratings of acceptance of denial treatment in Swedish children. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1987;15:258–263. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1987.tb00533.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Holst A, Ek L. Effect of systematized "behavior shaping" on acceptance of dental treatment in children. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1988;16:349–355. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1988.tb00580.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Corah NL, O'shea RM, Bissel GD. The dentist-patient relationship: perceptions by patients of dentist bebavior in relation to satisfaction and anxiety. J Am Dent Assoc. 1985;111:443–446. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1985.0144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Milgrom P, Mandel L, King B, Weinstein P. Origins of childhood dental fear. Behav Res Ther. 1995;33:313–319. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(94)00042-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Milgrom P, Fiset L, Melnick S, Weinstein P. The prevalence and practice management consequences of dental fear in a major US city. J Am Dent Assoc. 1988;116:641–647. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1988.0030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gatchel RJ, Ingersoll BD, Bowman L, Robertson MC, Walker C. The prevalence of dental fear and avoidance:a recent survey study. J Am Dent Assoc. 1983;107:609–610. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1983.0285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kumar S, Bhargav P, Patel A, Bhati M, Balasubramanyam G, Duraiswamy P, et al. Does dental anxiety influence oral health-related quality of life? Observations from a cross-sectional study among adults in Udaipur district, India. J Oral Sci. 2009;51:245–254. doi: 10.2334/josnusd.51.245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gatchel RJ. The prevalence of dental fear and avoidance: expanded adult and recent adolescent surveys. J Am Dent Assoc. 1989;118:591–593. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1989.0068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schwarz E. Dental anxiety in young adult Danes under alternative dental care programs. Scand J Dent Res. 1990;98:442–450. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.1990.tb00996.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stouthard ME, Hoogstraten J. Prevalence of dental anxiety in The Netherlands. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1990;18:139–142. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1990.tb00039.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hakeberg M, Berggren U, Carlsson SG. Prevalence of dental anxiety in an adult population in a major urban area in Sweden. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1992;20:97–101. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1992.tb00686.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grytten J, Holst D, Rossow I, Vasend O, Wang N. 100,000 more adults visit the dentist; a few results of November 1989. Nor Tannlaegeforen Tid. 1990;100:414–422. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hakansson J. Dental care habits, attitudes towards dental health and dental status among 20-60 year-old individualsin Sweden [thesis] Sweden: University of Ltuid; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Berggren U. Dental fear and avoidance; a study of etiology, consequences and treatment [thesis] Sweden: Goteborg University; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Paryab M, Hosseinbor M. Dental anxiety and behavioral problems: a study of prevalence and related factors among a group of Iranian children aged 6-12. J Indian Soc Pedod Prev Dent. 2013;31:82–86. doi: 10.4103/0970-4388.115699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chellappah NK, Vignesha H, Milgrom P, Lo GL. Prevalence of dental anxiety and fear in children in Singapore. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1990;18:269–271. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1990.tb00075.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bedi R, Sutcliffe P, Donnan PT, McConnachie J. The prevalence of dental anxiety in a group of 13- and 14-year old Scottish children. Int J Paediatr Dent. 1992;2:17–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-263x.1992.tb00003.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Klingberg G, Berggren U, Noren JG. Dental fear in an urban Swedish population: prevalence and concomitant factors. Community Dent Health. 1994;11:208–214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Milgrom P, Jie Z, Yang Z, Tay KM. Cross-cultural validity of a parent's version of the Dental Fear Survey Schedule for Children in Chinese. Behav Res Ther. 1994;32:131–135. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(94)90094-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cuthbert MI, Melamed BG. A screening device: children at risk for dental fears and management problems. ASDC J Dent Child. 1982;49:432–436. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kleinknecht RA, Klepac RK, Alexander LD. Origins and characteristics of fear of dentistry. J Am Dent Assoc. 1973;86:842–848. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1973.0165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Weiner AA, Sheehan DV. Etiology of dental anxiety: psychological trauma or CNS chemical imbalance? Gen Dent. 1990;38:39–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Weiner AA. Theory and management of anxiety and phobic disorders as they interrelate to the dental visit. Analgesia. 1980;11:5–13. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Weiner AA. The basic principle of fear, anxiety and phobias as they relate to the dental visit. Quintessence Int Dent Dig. 1980;11:119–123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Weiner AA. The clinical treatment of fear, anxiety and phobias as they relate to the dental visit (II) Quintessence Int Dent Dig. 1980;11:69–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gauthier JG, Ricard S, Morin BA, Dufour L, Brodeur JM. La peur destraitements chez les jeunes adolescents: développement et évaluation d'une mesure cognitive. J Can Dent Assoc. 1991;57:658–662. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ferrari M. Fears and phobias in childhood: some clinical and developmental considerations. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 1986;17:75–87. doi: 10.1007/BF00706646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Prins PJM, Wit de CAM, Goudema PP. Angst in ontwikkelings-psychopathologisch perspectief (Anxiety from the developmental psychopathology perspective) Kind Adolescent. 1997;18:185–199. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mendoza-Mendoza A, Perea MB, Yañez-Vico RM, Iglesias-Linares A. Dental fear in children: the role of previous negative dental experiences. Clin Oral Investig. 2015;19:745–751. doi: 10.1007/s00784-014-1380-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yüzügüllü B, Gülşahi A, Celik C, Bulut S. Dental anxiety and fear: relationship with oral health behavior in a Turkish population. Int J Prosthodont. 2014;27:50–53. doi: 10.11607/ijp.3708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Coric A, Banozic A, Klaric M, Vukojevic K, Puljak L. Dental fear and anxiety in older children: an association with parental dental anxiety and effective pain coping strategies. J Pain Res. 2014;7:515–521. doi: 10.2147/JPR.S67692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mohammed RB, Lalithamma T, Varma DM, Sudhakar KN, Srinivas B, Krishnamraju PV, et al. Prevalence of dental anxiety and its relation to age and gender in coastal Andhra (Visakhapatnam) population, India. J Nat Sci Biol Med. 2014;5:409–414. doi: 10.4103/0976-9668.136210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.de Carvalho RW, de Carvalho Bezerra Fãlcao PG, de Luna Campos GJ, de Souza Andrade ES, do Egito Vasconcelos BC, da Silva Pereira MA. Prevalence and predictive factors of dental anxiety in Brazilian adolescents. J Dent Child (Chic) 2013;80:41–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mittal R, Sharma M. Assessment of psychological effects of dental treatment on children. Contemp Clin Dent. 2012;3(Suppl 1):S2–S7. doi: 10.4103/0976-237X.95093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Oliveira MM, Colares V. The relationship between dental anxiety and dental pain in children aged 18 to 59 months: a study in Recife, Pernambuco State, Brazil. Cad Saude Publica. 2009;25:743–750. doi: 10.1590/s0102-311x2009000400005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Van Wijk AJ, Hoogstraten J. Experience with dental pain and fear of dental pain. J Dent Res. 2005;84(10):947–950. doi: 10.1177/154405910508401014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Guelmann M. Dental fear in children may be related to previous pain experience during dental treatment. J Evid Based Dent Pract. 2005;5:143–144. doi: 10.1016/j.jebdp.2005.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Klages U, Ulusoy O, Kianifard S, Wehrbein H. Dental trait anxiety and pain sensitivity as predictors of expected and experienced pain in stressful dental procedures. Eur J Oral Sci. 2004;112:477–483. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.2004.00167.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jamieson LM, Thomson WM, McGee R. An assessment of the validity and reliability of dental self-report items used in a National Child Nutrition Survey. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2004;32:49–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2004.00126.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Milsom KM, Tickle M, Blinkhorn AS. Dental pain and dental treatment of young children attending the general dental service. Br Dent J. 2002;192:280–284. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4801355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ten Berge M, Veerkamp JS, Hoogstraten J, Prins PJ. Childhood dental fear in the Netherlands: prevalence and normative data. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2002;30:101–107. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0528.2002.300203.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Liddell A, Locker D. Gender and age differences in attitudes to dental pain and dental control. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1997;25:314–318. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1997.tb00945.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schuurs AH, Hoogstraten J. Appraisal of dental anxiety and fear questionnaires: a review. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1993;21:329–339. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1993.tb01095.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bergius M, Berggren U, Bogdanov O, Hakeberg M. Dental anxiety among adolescents in St. Petersburg, Russia. Eur J Oral Sci. 1997;105:117–122. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.1997.tb00189.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Thomson WM, Poulton RG, Kruger E, Davies S, Brown RH, Silva PA. Changes in Self-reported Dental Anxiety in New Zealand Adolescents from Ages 15 to 18 Years. J Dent Res. 1997;76:1287–1291. doi: 10.1177/00220345970760060801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Klingberg G. Dental fear and behavior management problems in children. A study of measurement, prevalence, concomitant factors, and clinical effects. Swed Dent J Suppl. 1995;103:1–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hassett LC. Summary of the scientific literature for pain and anxiety control in dentistry. Anesth Prog. 1994;41:48–57. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Heitkemper T, Layne C, Sullivan DM. Brief treatment of children's dental pain and anxiety. Percept Mot Skills. 1993;76:192–194. doi: 10.2466/pms.1993.76.1.192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Holst A, Hallonsten AL, Schröder U, Ek L, Edlund K. Prediction of behavior-management problems in 3-year-old children. Scand J Dent Res. 1993;101:110–114. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.1993.tb01098.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kunzelmann KH, Dünninger P. Dental fear and pain: effect on patient's perception of the dentist. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1990;18:264–266. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1990.tb00073.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chellappah NK, Vignehsa H, Milgrom P, Lam LG. Prevaience of dental anxiety and fear in children in Singapore. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1990;18:269–271. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1990.tb00075.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Murray P, Liddell A, Donohue J. A Longitudinal Study of the Contribution of Dental Experience to Dental Anxiety in Children Between 9 and 12 Years of Age. J Behav Med. 1989;12:309–320. doi: 10.1007/BF00844874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Holst A, Schröder U, Ek L, Hallonsten AL, Crossner CG. Prediction of behavior management problems in children. Scand J Dent Res. 1988;96:457–465. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.1988.tb01584.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ridley-Johnson R, Melamed BG. Behavioral methods and research issues in management of child patients. Anesth Prog. 1986;33:17–23. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Jaffe M. Survey of Teaching Pain and Anxiety Control on the Predoctoral Level. Anesth Prog. 1983;30(1):10–13. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.McAlister GL, Richardson CL. Bibliography for the Control of Anxiety, Fear & Pain in Dentistry. Anesth Prog. 1982;29:11. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]