Abstract

Background:

The aims of this study were to evaluate the Jalowiec Coping Scale (JCS) psychometrically in Iranian women with multiple sclerosis (MS) and to identify the most frequent and efficacious coping strategies.

Methods:

A total of 306 women with MS participated in a cross-sectional study. A demographics questionnaire, the JCS, and the Perceived Stress Scale were administered. Forward-backward translation was used to achieve a Persian version of the scale. Cronbach α and test-retest were assessed for reliability. Convergent and discriminant validity were tested using an item-scaling procedure. The association of the JCS with perceived stress was examined using multiple regression. The factor structure was also explored using rotated exploratory factor analysis.

Results:

Participants had a mean (SD) age of 32.0 (6.6) years, and nearly half reported visual impairment as the first symptom of disease. Cronbach α for the scale was 0.898 and for the subscales ranged from 0.254 to 0.778. Relatively good convergent and discriminant validity were achieved (success rate ≥69%). Subscales assessing optimistic, fatalistic, and emotive coping predicted stress levels. A four-factor solution explained 30% of the total variance. Optimistic and supportive coping styles were the most common and effective styles, respectively, reported.

Conclusions:

The JCS may be useful in assessing coping strategies in Iranian women with MS. Further studies are needed to better understand how coping styles used in practice are similar to their theoretical constructs.

Multiple sclerosis (MS) has been recognized as a common neurologic disorder that is characterized by progressive demyelination of the central nervous system. Several disease-modifying drugs are available, but they are not completely effective in all people with MS and they do not usually reverse existing symptoms.1 MS usually occurs in young adults and is more frequent in females.2,3 Globally, more than 2 million people are affected by MS.4 This disease is not limited to specific geographic areas, but in some countries it is considered to be a serious clinical condition. Many developed and developing countries report a high prevalence rate of MS.5 For example, in the United States, 12,000 new cases of MS are recorded annually, and in Australia more than 23,000 people have MS.6,7 Although preliminary investigations have categorized Iran regions as having less than 5 cases of MS per 100,000 population, several reports have indicated rates of 12 to 14 cases per 100,000 in those aged 16 to 50 years, with a presence in women twice as often as in men.3,8

People with MS have many stressors due to their disease. Psychological problems such as denial of disease, depression, anxiety, and negative changes in lifestyle and decreased social interactions affect up to 80% of people with MS.9,10 Moreover, symptoms such as pain, blurred vision, fatigue, dizziness, physical imbalance, and urologic and sexual dysfunctions negatively affect health-related quality of life in these patients.11 Therefore, coping with such problems may be a key to the management of MS and its associated symptoms.

Coping has been defined as a way of appraising life stressors and applying strategies to adjust to them.12 According to Lazarus and Folkman,13 people cope with stress by using a combination of problem- and emotion-focused coping strategies. The former is based on changing or managing the issues underlying the stress, and the latter involves managing emotional reactions to stress. Strategies such as planning, responding, and information seeking are examples of problem-focused coping, and worry, avoidance, and self-blaming are examples of emotion-focused coping.13 Increased stress and depressive disorders in patients with MS may be related to higher use of emotion-focused coping and lower use of problem-focused coping, leading to poor adjustment.14,15 Investigation of coping styles has improved the understanding of how patients with MS handle their symptoms and has assisted in the development of interventions to increase health-related quality of life and the likelihood of employment.11,16

Males and females with MS cope differently with problems. Studies show that women with MS experience higher levels of emotion-focused coping than men.14,15 However, there is only a small body of research on coping styles in patients with MS, especially in women. This may be due to a lack of standard instruments for assessing coping style. Instruments such as the Ways of Coping Questionnaire,17 Coping Orientation for Problem Experiences,14 the Coping Self-efficacy Scale,15 and the Brief COPE Inventory18 have been used in patients with MS. Nevertheless, there is limited evidence regarding the psychometric properties of measures of coping for use in patients with MS.

Jalowiec developed the Jalowiec Coping Scale (JCS) based on information provided by Lazarus and Folkman to assess problem- and emotion-focused strategies of coping. An important advantage of the JCS over other coping scales is the inclusion of ratings of perceived efficiency for each strategy.19 The multiple dimensions that the scale assesses can help investigators distinguish between different coping styles. The JCS, to our knowledge, has not yet been tested in patients with MS, and studies of the scale in populations with different cultural backgrounds are lacking. Therefore, we decided to examine the psychometric properties of the JCS in women with MS from Iran and to explore the coping styles that are used most frequently and effectively by these patients.

Methods

Design and Sample

This was a cross-sectional study that examined a convenience sample of members of the Iran MS Society located in Tehran. Overall, 332 people were invited, and 26 (8%) declined. Sample size was calculated so that at least five people per item were included so that factor analysis could be conducted. Data collection took place between April and June 2015. The inclusion criteria were a diagnosis of MS based on the McDonald criteria,20 Persian speaking, and age between 18 and 60 years. Patients who were pregnant, had a history of psychosis or other serious mental problems (eg, cognitive disorders), or were diagnosed as having physical or neurologic conditions not related to MS were excluded. Trained researchers administered the questionnaire during face-to-face interviews. Written informed consent was obtained from all the participants, and the study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Baqiyatallah University of Medical Sciences (Tehran, Iran).

The JCS

The JCS includes 60 items with two ratings each assessing the frequency and the effectiveness of different coping behaviors. Each item has a 4-point rating from never used (0) to often used (3) for the frequency rating and from not helpful (0) to very helpful (3) for the effectiveness rating. Items are categorized into eight style subscales: confrontive (10 items), evasive (13 items), optimistic (9 items), fatalistic (4 items), emotive (5 items), palliative (7 items), supportive (5 items), and self-reliant (7 items). The confrontive subscale asks about how the person deals with problems and situations; the evasive domain includes coping behaviors performed to avoid problems; optimistic items involve coping by thinking positively and optimistically about situations; the fatalistic dimension includes coping strategies involving pessimism, hopelessness, and feeling little control over situations and that results are inevitable; the emotive coping style consisted of items that involve worrying, emotional release, and self-blame; palliative coping style behaviors are engaged in to reduce stress and achieve a state of calm; the supportive domain is related to the use of personal, professional, or spiritual support systems to cope; and the self-reliant domain contains coping strategies that involve dependence on self to resolve stressful situations. The total score for the JCS ranges from 0 to 180, and subscale scores range from 0–12 to 0–39. Higher scores indicate greater use or greater effectiveness of coping strategies.19,21

Translation and Adaptation of the JCS

Following the guidelines provided by Beaton et al.,22 the first step of the translation process involved contacting the original developer of the JCS and requesting permission to translate the questionnaire. Then, two bilingual translators, who were native speakers of Persian and fluent in English, conducted the translation of the English version into Persian. One translator was a specialist in health psychology and the other was an expert in sociology. To produce a common translation from the two independent translations, a group session including two health education specialists, two nurses, and the initial translators was held. After a consensus on forward translation was arrived at, back translation was conducted by two English teachers who were not previously exposed to the questionnaire. Next, all translated versions of the questionnaire were discussed by the expert panel to achieve a prefinal version for field testing. To assess the clarity and understandability of the last version of the measure, 20 women with MS with a mean (SD) age of 29 (5.1) years completed the questionnaire and gave feedback on the clarity of the questions and responses. The final version was then arrived at and used for psychometric testing in this study.

Other Measures

Demographic and Disease-Related Data

Demographic information on age, marital status, education, number of children, employment, economic status, and insurance status, along with disease characteristics such as duration of disease, onset of first symptoms, and chief complaint related to the disease, were asked about.

Perceived Stress Scale

A validated Persian version of the 10-item Cohen Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) was administered.23 The PSS measures the perception of individuals regarding degree of stress experienced due to stressful life situations. The PSS asks respondents to state their feelings and thoughts about different dimensions such as control, confidence, and coping with stress during the past month using a 5-point response format (never = 0 to very often = 4). Higher scores indicate greater levels of perceived stress.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics such as mean (SD) and number (percentage) were used to describe study variables. The internal consistency of the scale was assessed using the Cronbach α. Test-retest reliability was performed by testing the stability of the scale over 2 weeks in a separate small sample involving 25 women with MS. Limits of detectable change were performed to assess the responsiveness of the scale by measuring floor and ceiling effects. If measures are higher than 20%, then scale detection may be impaired.24

Convergent and discriminant validity of the scale was tested by the item-scaling test. According to this procedure, items that theoretically should be related to a subscale are correlated with the total subscale score using Pearson correlation. Pearson correlation coefficients (r) that are on average higher than 0.4 with the subscale indicate acceptable convergent validity. Conversely, if the associations between items and their hypothesized subscale are stronger than the associations between these items and nonhypothesized subscales, then discriminant validity is established.25 We explored criterion-related validity of the JCS by examining relationships between the whole scale and its subscales with perceived stress, and also by examining the predictability of subscales of JCS with the total PSS score. A linear multiple regression model assessed this relationship. Assumptions necessary for linear regression, such as normality of distribution, homoscedasticity, and lack of collinearity, were examined before analysis.

Finally, the factor structure of the JCS was investigated using exploratory factor analysis (EFA). We evaluated the suitability of data to perform EFA using the Bartlett test of sphericity and the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin test. Principal components analysis with Varimax rotation was used to perform the EFA. Criteria to extract factors followed the Kaiser rule (eigenvalue > 1), scree plot, and rotated factor loadings exceeding 0.35. All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 20 software (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY). Statistical significance was set at P < .05.

Results

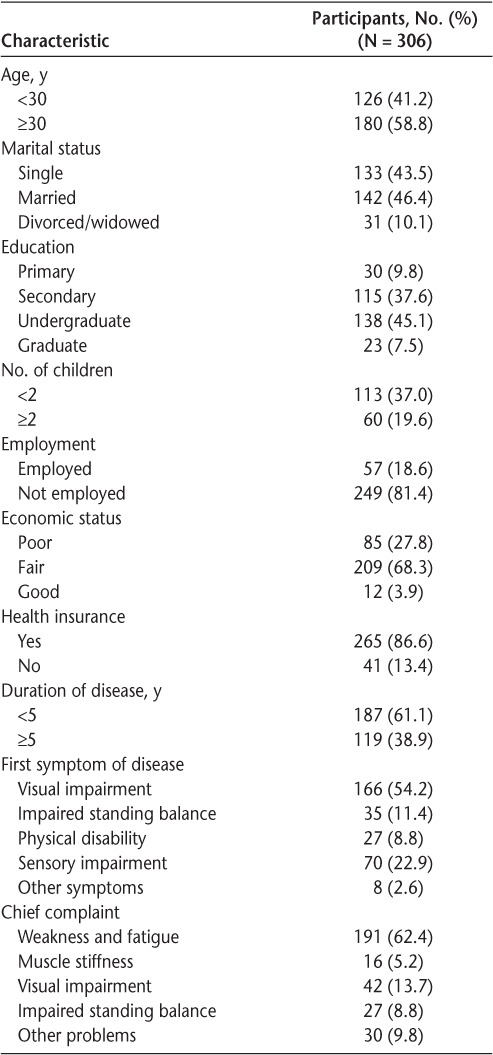

Participants had a mean (SD) age of 32.0 (6.6) years, and 46% were married. More than half of the sample had a university education. Thirty-seven percent of women who were married had fewer than two children. Nearly 80% of the respondents were not employed, and 70% appraised their family economic status as fair. Only 13% of the sample had no health insurance, and the mean (SD) time diagnosed as having MS was 5.0 (4.55) years. Approximately half of the sample indicated that visual impairment was the first symptom of the disease, and weakness/fatigue was the most prevalent symptom (62%) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Participant characteristics

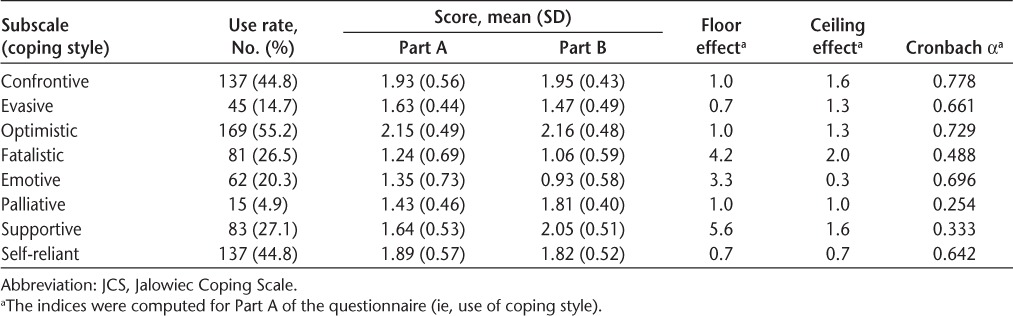

Table 2 provides descriptive statistics for the subscales of the JCS along with floor and ceiling effects and Cronbach α values. The most commonly used coping styles were optimistic, confrontive, and self-reliant. The most effective coping styles as reported by participants were optimistic, supportive, and confrontive. Floor and ceiling effects for all the subscales ranged from 0.3 to 5.6. Except for the palliative, supportive, and fatalistic coping styles, the remaining styles had a Cronbach α value greater than 0.64. The α value for the scale as a whole was 0.898. Stability over time was adequate, with high test-retest correlations for coping style subscales (r = 0.81–0.86).

Table 2.

Characteristics of the JCS subscales (N = 306)

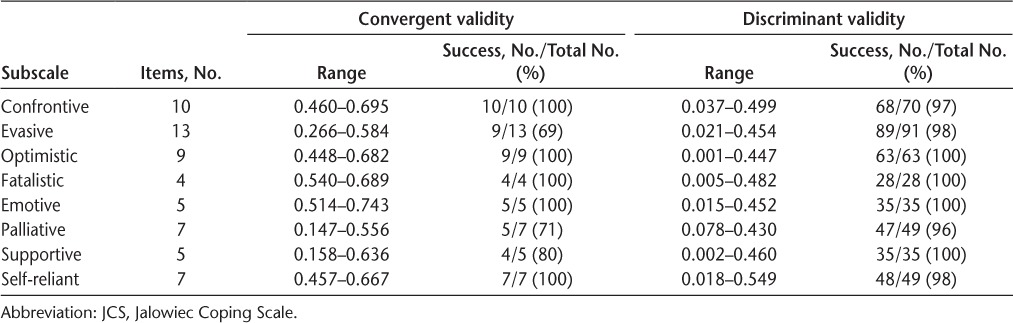

Convergent validity of the JCS subscales indicated that 69% or more were correlated with hypothesized dimensions. Discriminant validity indicated that all the subscales had a success rate near 100% in terms of stronger relationships to their hypothesized dimension than to other dimensions (Table 3).

Table 3.

Item-scaling test for convergent and discriminant validity of the JCS (Part A)

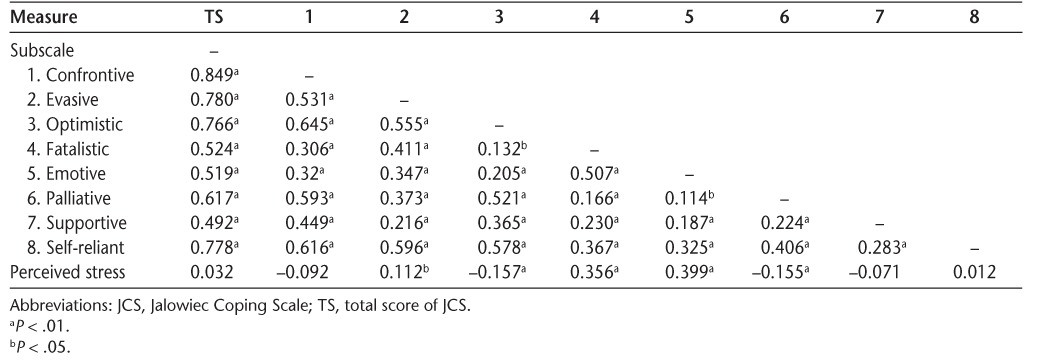

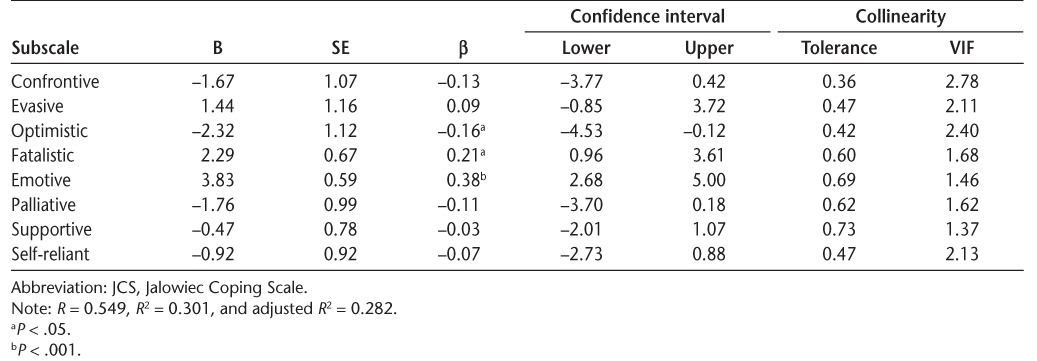

Significant associations between subscales and total JCS scores were r > 0.492. However, some dimensions of the JCS, such as confrontive, supportive, and self-reliant coping styles, were not significantly correlated with perceived stress. All subscales of the JCS were moderately to strongly correlated with each other (P < .01) (Table 4). Multiple regression analysis confirmed a significant association between perceived stress (PSS) and emotive, optimistic, and fatalistic coping styles. As indicated in Table 5, there was no collinearity between the JCS subscales in predicting stress (VIF ≤ 2.78; tolerance, 0.36–0.73). Nearly 30% of the total variance was explained with JCS subscales.

Table 4.

Associations between the JCS subscales (Part A) and perceived stress by Spearman rho correlation

Table 5.

Predictive value of the JCS subscales (Part A) regarding perceived stress using multiple regression

A Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin test value of 0.704 and a significant Bartlett test result (P < .001) indicated that the data were suitable for factor analysis. Initial EFA without rotation based on the Kaiser rule revealed 19 extra table factors. To reduce the number and integrate factors, a scree plot (Supplementary Figure 1, which is published in the online version of this article at ijmsc.org) was used, and a four-factor solution was selected. Factor loadings of these components based on Varimax rotation are provided in Supplementary Table 1. These factors explained 33% of the total variance in scale scores.

Discussion

The purpose of the present study was to assess the psychometric properties of the Persian version of the JCS in Iranian women with MS. The scale showed adequate validity and reliability. However, theoretical rationales proposed by the original authors for categorizing coping styles differed somewhat in this sample. One-third of the scale variance was explained by four factors. Nevertheless, optimistic, confrontive, and self-reliant coping styles were more frequent than other styles, and participants indicated that the most effective coping styles were optimistic, supportive, and confrontive.

Disease-related characteristics of the sample were notable. Visual impairment was the most common first symptom that participants experienced. In a study of 303 people with MS, Jasse et al.26 found that 35% reported visual impairment as the first symptom of the disease, which is comparable with the present study. In addition, weakness and fatigue were the most problematic issues reported by patients in the present study, which is consistent with other studies of patients with MS. For example, in an international Web-based study, two-thirds of patients with MS experienced clinically significant fatigue.27

Another notable characteristic of the present sample was the high unemployment rate. Because many patients with MS in the present study had physical or visual disabilities, it is understandable that employment was likely difficult. Defining jobs that they may be able to perform will increase their ability to find employment and, therefore, help in their coping with the disease.

The Persian version of the JCS in this study had satisfactory reliability in terms of internal consistency and stability over time. The Cronbach α value for coping styles such as palliative, supportive, and fatalistic did not achieve the criterion for minimal acceptability. Many authors suggest that α values should be higher than 0.7, although several investigators have argued that greater than 0.6 may also be adequate.24 In a sample of patients with end-stage renal disease, Lindqvist et al.28 reported α values for the JCS that ranged from 0.85 for confrontive to 0.46 for emotive coping styles. The Norwegian version of the JCS had α values ranging from 0.55 for the fatalistic dimension to 0.88 for the confrontive coping style.21 In the study by Ulvik et al.29 that examined the revised JCS in patients waiting for angiography, α values ranged from 0.48 to 0.81, and the strongest values were for the confrontive, evasive, and optimistic coping styles. In light of results from these studies, it seems that the problem-focused coping styles have higher internal consistency than the emotion-focused coping styles. Nevertheless, the overall α value for the JCS in the present study was congruent to that reported in previous studies.21,28,29 Significant relationships between subscales of the JCS are another indicator of the scale's internal consistency. The stability of the scale over time in the present study was also similar to that reported by others.19

Validity of the JCS was examined using multiple methods, including convergent, divergent, and criterion validity, as well as by identifying the underlying factor structure of the scale. All the subscales except evasive, palliative, and supportive achieved acceptable convergent validity. This may be because several items of these styles overlap with other coping styles assessed by the JCS, and as Jalowiec and colleagues19 also emphasized, determining distinct coping strategies for each style is difficult and many are interrelated. However, the findings from tests of discriminant validity indicated that the categorization of coping styles at least theoretically had a solid basis. We also assessed associations between scores on the PSS and the JCS to see how these scales might be correlated. Interestingly, some subscales, such as the confrontive, supportive, and self-reliant styles, did not relate to stress scores on the PSS. Although these subscales were among the coping styles that were most commonly used and judged to be effective, it may seem paradoxical that they were not correlated with perceived stress. The issue may be due to the extensive range of coping styles assessed by the JCS compared with the limited number of items assessed by the PSS. In other words, there are many coping styles that may not be related to the type of stress assessed by the PSS. Alternatively, this may also mean that these coping styles are not particularly effective in reducing stress.

We found that the optimistic coping style was the most influential coping style in reducing stress in terms of self-perceived effectiveness and when predicting perceived stress in regression analyses. On the other hand, emotive and fatalistic styles were associated with increased perceived stress. Several studies have examined coping style and associations with mental health states in people with MS. McCabe et al.17 found that patients with MS usually ignored problem-focused coping strategies and did not use social support–seeking behaviors, resulting in maladjustment to the disease. This finding is consistent with the present results showing that emotion-oriented coping strategies were not associated with lower stress levels. Tan-Kristanto and Kiropoulos,18 in a study of newly diagnosed people with MS, also reported that emotional coping was a common coping style that was significantly correlated with anxiety, explaining 37% of the variance in this outcome.

The four-factor solution in the present study explained nearly 30% of the total variance. The factor structure of the JCS has been explored in previous studies, and these studies also could not confirm the theoretical constructs of the scale. Gulick30 conducted factor analysis of the JCS in 156 caregivers of people with MS, obtaining a six-factor structure. In another study of patients with psoriasis, a three-factor solution was found,21 and likewise in the study by Sigstad et al.31 of patients with antibody deficiency, the subscales of the JCS grouped in three factors consisting of 1) optimistic; 2) evasive, fatalistic, and self-reliant; and 3) confrontive, emotive, palliative, and supportive styles. The present study found a similar factor structure as that reported by Sigstad et al., with most evasive and optimistic subscale items loading on factor 1; palliative, emotive, and fatalistic items loading on factor 2; many confrontive and supportive items loading on factor 3; and, finally, several self-reliance items loading on factor 4.

The strengths of the present study are a relatively large sample, collection of a comprehensive set of demographic and disease characteristics, and a high response rate and very little missing data. In addition, this study used a validated, widely used measure of coping for the first time for Iranian women with MS. Nevertheless, there are some limitations to the present study that should be considered. First, this was a convenience sample, and these findings may not generalize to all women with MS in Iran. Second, using in-person interviews for collecting data may have introduced biases related to respondents providing socially desirable or stereotyped responses. Third, we surveyed only females, and studies in males with MS are also needed. Finally, classification of patients using a disability index such as the Expanded Disability Status Scale might have provided a better description of respondents' MS severity that could influence coping strategies. Thus, careful assessment of disability is suggested for future studies of this type.

Conclusion

The JCS seems to be a valid and reliable tool for assessing coping styles in Iranian women with MS. The grouping of coping styles based on the developer's suggestions may not correspond to the types of coping that women with MS in Iran use to adapt to their illness. This study also suggests that several frequently used coping styles, at least in this population, are not associated with lower stress levels. In contrast, optimistic and supportive coping styles are associated with lower stress levels. Given the positive association between the optimistic coping style and stress reduction in Iranian women with MS, and because problem-focused coping is infrequently used in such patients, programs should be developed to educate patients regarding the application of effective coping strategies, particularly if these findings are replicated.

PracticePoints

The Jalowiec Coping Scale may be a valid and reliable tool for assessing coping style in women with MS.

Emotion-focused coping is common in women with MS.

Given the effectiveness of optimistic and social support coping strategies, these should receive special attention when planning disease management strategies in this population.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Jalowiec for permission to use the JCS in this study. Also, we would like to extend our appreciation to the staff and managers of the Iran MS Society for collaboration in data collection.

Financial Disclosures

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1. Rodriguez M. Advances in Multiple Sclerosis and Experimental Demyelinating Diseases. Berlin, Germany: Springer; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Matthews WB, Rice-Oxley M.. Multiple Sclerosis: The Facts. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Etemadifar M, Sajjadi S, Nasr Z, . et al. Epidemiology of multiple sclerosis in Iran: a systematic review. Eur Neurol. 2013; 70: 356– 363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. What is multiple sclerosis? U.S. National Library of Medicine. http://ghr.nlm.nih.gov/condition/multiple-sclerosis. Published 2015. Accessed February 8, 2016.

- 5. Heydarpour P, Khoshkish S, Abtahi S, Moradi-Lakeh M, Sahraian MA.. Multiple sclerosis epidemiology in Middle East and North Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neuroepidemiology. 2015; 44: 232– 244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Campbell JD, Ghushchyan V, Brett McQueen R, . et al. Burden of multiple sclerosis on direct, indirect costs and quality of life: national US estimates. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2014; 3: 227– 236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hollingworth S, Walker K, Page A, Eadie M.. Pharmacoepidemiology and the Australian regional prevalence of multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2013; 19: 1712– 1716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Moghtaderi A, Rakhshanizadeh F, Shahraki-Ibrahimi S.. Incidence and prevalence of multiple sclerosis in southeastern Iran. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2013; 115: 304– 308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Dehnavi SR, Heidarian F, Ashtari F, Shaygannejad V.. Psychological well-being in people with multiple sclerosis in an Iranian population. J Res Med Sci. 2015; 20: 535– 539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Taylor KL, Hadgkiss EJ, Jelinek GA, . et al. Lifestyle factors, demographics and medications associated with depression risk in an international sample of people with multiple sclerosis. BMC Psychiatry. 2014; 14: 327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wilski M, Tasiemski T.. Health-related quality of life in multiple sclerosis: role of cognitive appraisals of self, illness and treatment. Qual Life Res. 2016; 25: 1761– 1770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Marks D. Health Psychology: Theory, Research, and Practice. 3rd ed. Los Angeles, CA: Sage; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lazarus RS, Folkman S.. Stress, Appraisal, and Coping. New York, NY: Springer; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Goretti B, Portaccio E, Zipoli V, . et al. Impact of cognitive impairment on coping strategies in multiple sclerosis. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2010; 112: 127– 130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Mikula P, Nagyova I, Krokavcova M, . et al. Coping and its importance for quality of life in patients with multiple sclerosis. Disabil Rehabil. 2014; 36: 732– 736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Strober LB, Arnett PA.. Unemployment among women with multiple sclerosis: the role of coping and perceived stress and support in the workplace. Psychol Health Med. 2015; October 12: 1– 9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. McCabe MP, McKern S, McDonald E.. Coping and psychological adjustment among people with multiple sclerosis. J Psychosom Res. 2004; 56: 355– 361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Tan-Kristanto S, Kiropoulos LA.. Resilience, self-efficacy, coping styles and depressive and anxiety symptoms in those newly diagnosed with multiple sclerosis. Psychol Health Med. 2015; 20: 635– 645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Jalowiec A, Murphy SP, Powers MJ.. Psychometric assessment of the Jalowiec Coping Scale. Nurs Res. 1984; 33: 157– 161. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. McDonald WI, Compston A, Edan G, . et al. Recommended diagnostic criteria for multiple sclerosis: guidelines from the International Panel on the diagnosis of multiple sclerosis. Ann Neurol. 2001; 50: 121– 127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wahl A, Moum T, Hanestad BR, Wiklund I, Kalfoss MH.. Adapting the Jalowiec Coping Scale in Norwegian adult psoriasis patients. Qual Life Res. 1999; 8: 435– 445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Beaton DE, Bombardier C, Guillemin F, Ferraz MB.. Guidelines for the process of cross-cultural adaptation of self-report measures. Spine. 2000; 25: 3186– 3191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Maroufizadeh S, Zareiyan A, Sigari N.. Reliability and validity of Persian version of perceived stress scale (PSS-10) in adults with asthma. Arch Iran Med. 2014; 17: 361– 365. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Gallagher P, Desmond D, MacLachlan M.. Psychoprosthetics. London, UK: Springer; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ware JE Jr, Gandek B.. Methods for testing data quality, scaling assumptions, and reliability: the IQOLA Project approach. International Quality of Life Assessment. J Clin Epidemiol. 1998; 51: 945– 952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Jasse L, Vukusic S, Durand-Dubief F, . et al. Persistent visual impairment in multiple sclerosis: prevalence, mechanisms and resulting disability. Mult Scler. 2013; 19: 1618– 1626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Weiland TJ, Jelinek GA, Marck CH, . et al. Clinically significant fatigue: prevalence and associated factors in an international sample of adults with multiple sclerosis recruited via the internet. PLoS One. 2015; 10: e0115541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lindqvist R, Carlsson M, Sjoden PO.. Coping strategies and styles assessed by the Jalowiec Coping Scale in a random sample of the Swedish population. Scand J Caring Sci. 2000; 14: 147– 154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ulvik B, Johnsen TB, Nygard O, Hanestad BR, Wahl AK, Wentzel-Larsen T.. Factor structure of the revised Jalowiec Coping Scale in patients admitted for elective coronary angiography. Scand J Caring Sci. 2008; 22: 596– 607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Gulick EE. Coping among spouses or significant others of persons with multiple sclerosis. Nurs Res. 1995; 44: 220– 225. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Sigstad HM, Stray-Pedersen A, Froland SS.. Coping, quality of life, and hope in adults with primary antibody deficiencies. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2005; 3: 31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.