Abstract

The protein kinase C (PKC) is a family of serine/threonine kinases that are key regulatory enzymes involved in growth, differentiation, cytoskeletal reorganization, tumor promotion, and migration. We investigated the functional involvement of PKC isotypes and of E-cadherin in the regulation of the locomotion of six human colon-adenocarcinoma cell lines. The different levels of the PKC α and the E-cadherin expression have predictable implications in the spontaneous locomotory activity. With the use of PKC α–specific inhibitors (safingol, Go6976) as well as the PKC δ–specific inhibitor rottlerin, we showed that only PKC α plays a major role in the regulation of tumor cell migration. The results were verified by knocking out the translation of PKC isozymes with the use of an antisense oligonucleotide strategy. After stimulation with phorbol ester we observed a translocation and a colocalization of the activated PKC α at the plasma membrane to the surrounding extracellular matrix. Furthermore, we investigated the functional involvement of E-cadherin in the locomotion with the use of a blocking antibody. A high level of PKC α expression together with a low E-cadherin expression was strongly related to a high migratory activity of the colon carcinoma cells. This correlation was independent of the differentiation grade of the tumor cell lines.

INTRODUCTION

Cell migration is an essential step for embryonic development, wound healing, immune response, and tumor cell migration, that is, invasion and metastasis (Horwitz and Parsons, 1999). However, the transduction pathways that guide signals into the cell leading to migration are poorly understood. Different families of cell surface receptors are required to transduce external signals (e.g., from the ECM) for cell migration. Receptors of the families of integrins, cadherins, and selectins are mediating cell–cell interactions as well as cell–ECM contacts (Maaser et al., 1999). These adhesive interactions are important for migration because they also regulate intracellular signal transduction pathways (Clark and Brugge, 1995). Alterations in the expression of integrins and cadherins have been associated with changes in the migratory activity and phenotype of cells (Hynes, 1992; Filardo et al., 1996; Huttenlocher et al., 1998; Rigot et al., 1998). It is known that PKC mediates migration via integrins (Rigot et al., 1998; Kiley et al., 1999; Ng et al., 1999) and is involved in the signaling of serpentine receptors as well as growth factor receptors (Entschladen and Zanker, 2000). Treatment with the phorbol ester phobol-12-myristate-13-acetate (PMA) increased the rate of cell division and induced cell migration, but the naturally occurring activators of protein kinase C (PKC) in vivo are the diacylglycerols (DAGs) and arachidonic acid, which are provided by phospholipases (Clemens et al., 1992).

The PKC is a family of serine/threonine kinases consisting of at least 11 isoenzymes divided into 3 subfamilies (Hofmann, 1997). These 3 groups have different characteristics that serve for classification: classic PKC isozymes: α, βI, βII, γ; novel PKCs: δ, ε, θ, η; and atypical PKCs: λ, ξ, ι. The isotypes are classified according to their requirements for calcium ions and phospholipids (e.g., phosphatidylserine and DAG) or phorbol esters (e.g., PMA) for activation. Only the classic PKC isotypes possess a binding site for calcium ions. This region is lacking in the novel and atypical PKCs, whereas the atypical PKCs are also lacking the binding site for DAG and phorbol esters. The PKC isozymes contain an amino-terminal regulatory domain and a carboxy-terminal catalytic domain, which are linked by a hinge region. It is important for the activation of the catalytic domain to open the hinge region after removal of the pseudosubstrate region from the catalytic site (Bruins and Epand, 1995). The regulatory domain of classic PKC isozymes consists of two domains, C1 and C2. The C1 region is responsible for DAG and phorbol ester binding, whereas the C2 region mediates the binding of calcium and negatively charged phosphatidylserine. The PKC requires acidic phospholipids for its activity and in the presence of activators the enzyme has the highest binding affinity for membranes containing phosphatidylserine. The activation of PKC by phosphorylation of serine and threonine residues is controlled by several modes, for example, autophosphorylation (Flint et al., 1990) as well as phosphorylation by other PKC isotypes (transphosphorylation; Pears et al., 1992).

The presence of several isozymes in one cell and differential activation or inhibition by different stimuli suggest that each PKC isotype is involved in the regulation of different functions and has a unique role in the cell. However, the biological significance of the heterogeneity in the PKC family is not clear (Radominska-Pandya et al., 2000). The pattern of PKC isotype expression is distinct between different tissues (Nishizuka, 1988) and differs even in the same tissue. In T lymphocytes the PKC isotype expression depends on the activation state of the cells (Corrigan et al., 1995). In macrophages the PKC δ isotype is known to phosphorylate pleckstrin, which remains phosphorylated 60 min after phagocytosis (Brumell et al., 1999). The myristoylated, alanine-rich C-kinase substrate (MARCKS) is also a conversant PKC substrate in fibroblasts and brain cells. The phosphorylation of MARCKS is found not to be specific for a special PKC isotype: conventional (c)PKC β1, novel (n)PKC δ, and PKC ε efficiently phosphorylated the MARCKS protein in vitro (Herget et al., 1995).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and Cell Culture

All cell lines used in this study were human colon carcinoma cells obtained from the DSMZ (Deutsche Sammlung von Mikroorganismen und Zellkulturen, Braunschweig, Germany) except SW 480 and SW 620, which were obtained from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Rockville, MD). The differentiation grades of the tumor cell lines were taken from the data sheets of the supplying companies. The poorly differentiated (grade III-IV) SW 480 cells and the metastatic SW 620 cell line were grown in antibiotic-free Leibovitz L-15 medium (PAA Laboratories GmbH, Linz, Austria), supplemented with 10% FCS in a humidified atmosphere without CO2 addition (Leibovitz et al., 1976). The moderately differentiated (grade II) Colo 320 cells were grown in RPMI 1640 medium (Life Technologies, Karlsruhe, Germany), supplemented with 10% FCS and 1% penicillin/streptomycin in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere (Quinn et al., 1979). The well-differentiated (grade I) HT 29 cells were grown in McCoy's 5A medium (PAA Laboratories GmbH), supplemented with 10% FCS and 1% penicillin/streptomycin in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere (von Kleist et al., 1975). The moderately to poorly differentiated (grade II-III) SW 403 cells were grown in Dulbecco's MEM medium (PAA Laboratories GmbH) and the poorly differentiated (grade III) SW 948 cells were grown in Leibovitz L-15 medium, both supplemented with 10% FCS and 1% penicillin/streptomycin in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere (Leibovitz et al., 1976).

Preparation of Three-dimensional ECM Lattices

Cultured cells were harvested with the use of a trypsin/EDTA solution. An amount of 6 × 104 cells was mixed with 150 μl buffered liquid collagen (pH 7.4, 1.63 mg/ml collagen type I; Collagen Corporation, Fremont, CA) containing minimal essential medium (Sigma, Deisenhofen, Germany) as well as the investigated substances: PMA, calphostin C (CC), rottlerin, safingol, and Go6976 (all provided by Calbiochem, Bad Soden, Germany). This mixture was loaded into self-constructed chambers as described previously (Friedl et al., 1995; Entschladen et al., 1997) with minor modifications.

Three-dimensional Cell Migration Assay

After polymerization of the collagen, the chambers were sealed, and cell locomotion within the three-dimensional collagen lattice was recorded by time-lapse videomicroscopy at 37°C for 12 h. For analysis of the migratory activity, 30 cells of each sample were randomly selected, and two-dimensional projections of paths were digitized as x/y-coordinates in 20-min intervals by computer-assisted cell tracking. For the analysis of the displacement (i.e., the part of cells that moved within the observation period) 40 cells were randomly selected, and whether they developed migratory activity within the whole observation period of 12 h was evaluated.

Flow Cytometry

The viability of the cells was investigated by flow cytometry, subsequent to the migration experiments. Because the cells had been incorporated into a collagen gel, a collagenase digestion (collagenase type I; Collagen Corporation, Fremont, CA) for 20 min at 37°C was performed before flow cytometry. Propidium iodide (PI) was used to distinguish nonviable from viable cells at a wavelength of 488 nm. PI was added to a final concentration of 2 μg/ml. PI-negative (viable) cells were gated because of morphology and lack of fluorescence. The expression of E-cadherin also was measured by flow cytometry. The mouse mAb against human E-cadherin (clone 67A4) was purchased from Coulter-Immunotech (Krefeld, Germany). A secondary fluorescein isothiocyanate–conjugated goat anti-mouse antibody obtained from Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories (West Grove, PA) was used for detection. The mean fluorescence intensity of specifically bound E-cadherin was measured compared with the binding of an isotypic control mouse antibody (Coulter-Immunotech).

Immunoblotting

The total amount of all classic and novel PKC isozymes (α, β, γ, δ, ε, θ, and η) was analyzed by immunoblotting as described previously (Entschladen et al., 1997). Colon carcinoma cells (4 × 105 to 8 × 105) were lysed in Laemmli sample buffer (Laemmli, 1970) and incubated for 10 min at 95°C. Proteins were separated with the use of PAGE according to the method of Laemmli and were transferred to an Immobilion-P membrane (Millipore, Bedford, MA) followed by blocking of the membranes with 5% dry milk powder (1 h, 20°C). After incubation of the membrane (2 h, 20°C) with the primary monoclonal antibodies against the various PKC isotypes (purchased from Transduction Laboratories, Lexington, KY), the membrane was washed vigorously with PBS-Tween. Subsequently, the membrane was first incubated with a peroxidase-linked anti-mouse antibody (1 μg/ml, 2 h, 20°C) and then with a chemiluminescence substrate (2 min, 20°C; Boehringer Mannheim). The chemiluminescence signal was detected by exposure to a Kodak X-OMAT AR film sheet (Sigma). Staining intensities were analyzed with a 300-dpi, 8-bit flatbed scanner and quantified with the use of National Institutes of Health Image software version 1.57 (Bethesda, MD).

Incubation with Antisense Oligonucleotides

The PKC (α, β, γ, and δ) isotype–specific phosphorothiolated antisense oligonucleotides (AO) and the control AO have been designed and manufactured by Biognostic GmbH (Goettingen, Germany). The efficiency of these AO to inhibit PKC isotype expression in SW 480 colon carcinoma cells was successfully shown by Hochegger et al. (1999). After preparation of a 100 μM stock solution of each (AO), an amount of 3 × 105 cells was incubated in a 5 μM solution (24–36 h, 37°C). The uptake of the oligonucleotides was checked by the addition of fluorescein isothiocyanate-labeled control AO in test samples with the use of flow cytometry and confocal laser scan microscopy for detection. To assess the effectiveness of the expression of the blocking AO, an immunoblot was performed as described above.

Confocal Laser Scan Microscopy

For immunofluorescence staining of the PKC α isoenzyme, 50 μl of a suspension of 1 × 105 colon carcinoma cells in PBS or PBS containing 50 ng/ml PMA was mixed with 100 μl buffered collagen, and the solution was transferred onto a coverslip. After 30 min of polymerization of the collagen matrix, cells were fixed with 3.7% paraformaldehyde (15 min, 20°C) and subsequently were permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100 (10 min, 20°C). Thereafter, the samples were incubated with 10 μg/ml (2 h, 20°C) of monoclonal mouse anti–PKC α antibody (purchased from Transduction Laboratories). After washing with PBS, the samples were incubated (2 h, 20°C) with 10 μg/ml a Rhodamine Red–conjugated AffiniPure Fab Fragment of a goat anti-mouse antibody (Dianova, Hamburg, Germany). After an additional washing step, the coverslips were inverted and mounted on slides. Confocal laser scanning microscopy with the use of a Leica TCS 4D microscope (Leica, Inc., Heidelberg, Germany) was performed as previously described (Friedl et al., 1997).

RESULTS

Migratory Activity and Displacement

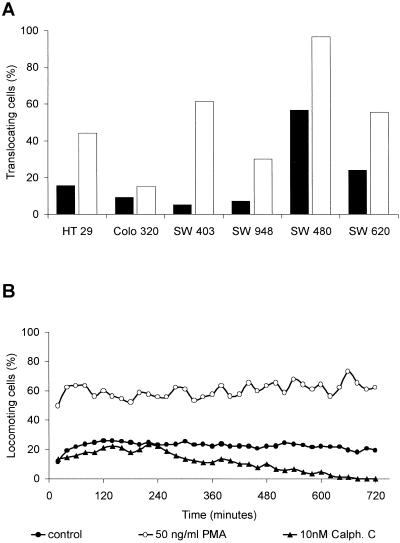

At first, we investigated the spontaneous migratory behavior of six different colon carcinoma cell lines: HT 29 (grade I), Colo 320 (grade II), SW 403 (grade II-III), SW 948 (grade III), SW 480 (grade III-IV), and the metastatic cell line SW 620 (the cell lines are ranked from well to poorly differentiated). All cell lines developed spontaneous locomotory activity (Figure 1A), but there was no correlation between the differentiation grade of the tumor cell lines and the migratory activity. Interestingly, migration of cells of the metastasis (SW 620) was lower than the migration of the parental primary tumor cell line (SW 480). These primary tumor cells developed the highest level of spontaneous migratory activity with >60% displacement. The metastatic cell line SW 620 had the second highest level of migrating cells, but the cells of this cell line reached only 25% displacement. All other cell lines remained around ∼10% displacement (Figure 1A). SW 480 cells had the highest level of locomotory activity throughout the observation period of 12 h (Figure 1B); these cells migrate with a mean migratory activity of 20–25% locomoting cells, whereas all other cell lines did not reach 10% locomotory activity.

Figure 1.

Locomotory activity of human colon carcinoma cell lines of different tumor grades. (A) Tumor cells (cell lines are ranked by differentiation grade) within a collagen matrix were observed for displacement during an observation period of 12 h. Forty randomly selected cells (n = 3, in total 120 cells) were analyzed, whether or not they were exhibiting spontaneous locomotory activity (displacement from the starting point, ▪). Addition of phorbol esters (50 ng/ml PMA, □) increased the percentage of translocating cells in all six tumor cell lines. The proportion between the locomotory activity of untreated cells compared with the activity of cells after addition of the phorbol ester was not related to the differentiation grade. (B) Spontaneous migration of untreated SW 480 cells (●; 30 randomly selected cells; n = 3, in total 90 cells); migration after PKC activation with 50 ng/ml PMA (○); and inhibition with 10 nM CC (▴).

Activation and Inhibition of Spontaneous Tumor Cell Migration

Addition of PKC activators such as phorbol esters (e.g., PMA) increased the percentage of locomoting cells in all six colon carcinoma cell lines (Figure 1A). The tumor cell line SW 480 reached nearly 100% displacement after addition of 50 ng/ml PMA. In all other cell lines an enhancement of migrating cells was observed after stimulation with the phorbol ester. The highest increase of displacement after PMA addition was detected at the grade II-III colon adenocarcinoma cell line SW 403, the cell line with the lowest spontaneous displacement. Interestingly, there was no correlation between the increase of locomotory activity after PMA addition and the differentiation grades.

To give further evidence (beside the activating effect of PMA) that the migration of the colon carcinoma cells was PKC dependent, we investigated whether inhibitors of the PKC reduced the spontaneous migration. For these investigations we first used the PKC-specific inhibitor CC, which is not PKC isotype specific. CC inhibits all DAG-requiring PKC isozymes (Bruns et al., 1991). With the use of the SW 480 cells, we found a total inhibition of migratory activity (Figure 1B). Ten hours after addition of 10 nM CC the locomotion of the cells stopped completely. This reduction was not due to cell death, as assessed by flow cytometry.

We concluded from these experiments concerning the activation and inhibition of the PKC that this enzyme plays a central role in the regulation of migration. We found that migration was controlled either by classic or by novel PKC isotypes, because PMA enhanced the migratory activity. Therefore, we excluded an involvement of the atypical PKC isozymes λ, ξ, and ι.

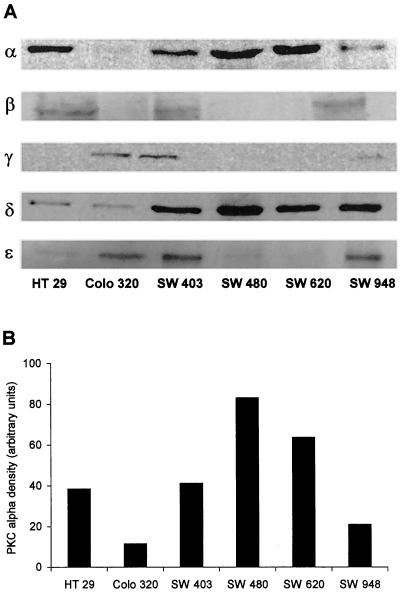

Analyses of the Expression of Different PKC Isotypes

Western blot analyses were made to determine the PKC isotypes expressed in the investigated cell lines. By comparison, the PKC isozyme levels of the colon carcinoma cell lines with high, moderate, and poor differentiation grades differences were detectable concerning the PKC isoenzyme expressions (Figure 2A). The PKC isozymes β and γ were not detectable in more than half of the investigated cell lines or showed only a slight expression. PKC α and δ isozymes were detectable in all six cell lines, although the cell line Colo 320 revealed a very faint PKC α expression. Therefore, we focused our investigations on these two PKC isozymes. The PKC α density of the colon carcinoma cell lines was analyzed with the use of the NIH image software version 1.57 and are shown as black bars in Figure 2B. The highest PKC α density was observable in the poorly differentiated tumor cell line SW 480, whereas the moderately differentiated Colo 320 cell line contained the lowest PKC α density, and the well differentiated HT 29 cell line had the fourth highest PKC α density. Again, there was no correlation between PKC α density and the differentiation grade of the cell lines.

Figure 2.

Immunoblot analysis of six human colon carcinoma cell lines at different tumor stages. (A) Antibodies against the classic and novel PKC isozymes α, β, γ, δ, and ε were used, and specifically bound antibodies were detected with the use of a secondary peroxidase-linked mouse anti-human antibody. (B) The PKC α densities of the PKC α blot were evaluated with the use of the NIH-image software version 1.57.

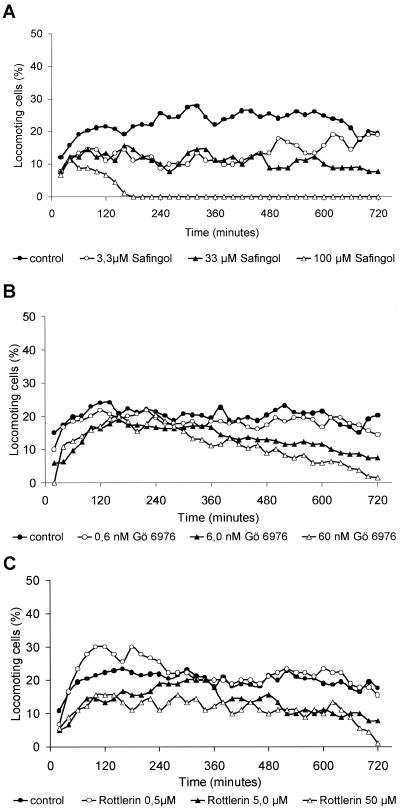

Inhibition of Spontaneous Cell Migration with the Use of PKC Isotype–specific Inhibitors

The results, obtained by the Western blot analysis, together with the findings received by the stimulation (PMA) and inhibition (CC) experiments, suggested focusing again on the PKC isozymes α and δ. We used safingol and Go6976 as PKC α–specific inhibitors and rottlerin for inhibiting the PKC δ (Figure 3, A–C). All results of the migration experiments shown in Figure 3 were carried out with the colon carcinoma cell line SW 480, because this cell line had the highest spontaneous locomotory activity, so that even a slight reduction of migration should be observable. Treatment with the PKC α–specific inhibitor safingol led to a reduction of spontaneous migration of SW 480 cells (Figure 3A). Safingol at a concentration of 33 μM reduced the migration by the half. By applying threefold higher concentrations (100 μM), migration was stopped completely after 3 h. In cells treated with a tenfold lower concentration of safingol (3.3 μM), a transient reduction of the migratory activity could be detected for 8 h, but within the last 4 h of the observation period, the migratory activity reached the level of untreated cells. We obtained identical results with the use of Go6976, another PKC α–specific inhibitor (Figure 3B). Go6976 inhibits PKC α isozymes by binding competitively to the ATP binding site on the catalytic domain of the enzyme. The viability of Go6976-treated cells was similar to the control cells. The viability of safingol-treated cells was slightly reduced (18%) compared with control cells (11%). Treatment of the SW 480 cells with Go6976 (6.0 nM) reduced the migratory activity to the half of the control level (Figure 3B). At 10-fold higher concentrations, migration decreased continuously and stopped totally at the end of the observation period. This reduction was not due to cell death as was assessed by flow cytometry (our unpublished results). Migration of the carcinoma cell line SW 480 was also reduced by the addition of the PKC δ–specific inhibitor rottlerin (Figure 3C). With the use of 5.0 μM and 50 μM of rottlerin an almost nonconcentration-dependent reduction of the migratory activity was detected. Cells treated with 0.5 μM rottlerin developed a migratory activity similar to untreated control cells. The viability of the cells after 12 h of investigation was unchanged compared with control cells.

Figure 3.

Inhibition of spontaneous migration of colon adenocarcinoma cell line SW 480 with PKC-specific inhibitors. Cell migration was recorded by time-lapse videomicroscopy, and the paths of 30 randomly selected cells were analyzed (mean value of 3 independent experiments, a total of 90 cells was analyzed). (A) Inhibition of spontaneous migration of SW 480 cells with the PKC α–specific inhibitor safingol. (B) Inhibition of spontaneous migration of SW 480 cells with the PKC α–specific inhibitor Go6976. (C) Inhibition of spontaneous migration of SW 480 cells with the PKC δ–specific inhibitor rottlerin.

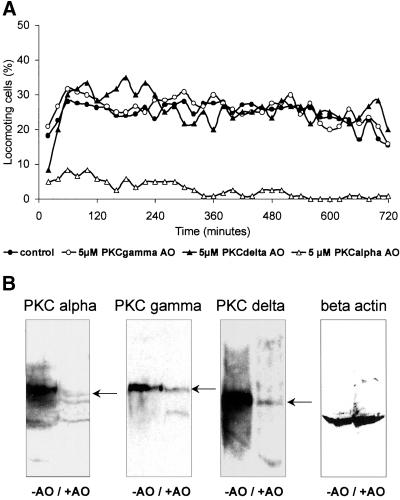

Inhibition of Migration with the Use of PKC Isotype Sequence-specific Antisense Oligonucleotides

To determine if PKC α or δ or maybe both PKC isotypes are necessary for migration of colon carcinoma cell lines, we used PKC isotype–specific AO. After incubating the SW 480 cells with 5 μM of the PKC α, δ, or γ (as a control)–specific AO for 24–36 h, cells were harvested, washed, and analyzed for migration. To test the unspecific cytotoxicity of the AO, we used PKC γ in SW 480 cells, which is not involved in migration.

The results verified the findings obtained with the pharmacological inhibitors (Figure 3, A–C). The PKC γ AO, serving as a negative control, showed no effect on the migratory activity of the colon carcinoma cells (Figure 4A). Treatment with the PKC δ AO revealed also no reduction of the migratory activity. Only the AO binding to PKC α mRNA completely abolished migratory activity. This loss of locomotion was not due to cell death, as assessed by flow cytometry. The viability of PKC α antisense treated cells was reduced compared with untreated control cells (35% vs. 15%). The inhibition of migration resulted from a decreased translation of the PKC α isotype as suggested by the Western blot analysis (Figure 4B). However, the inhibition of expression was not completely with neither AO. Therefore, we could not exclude residual side-effects of PKC isotypes other than the PKC α.

Figure 4.

Inhibition of spontaneous migration. (A) Untreated SW 480 cells and cells treated with PKC isotype-specific AO with a prior incubation of 36 h. (B) Immunoblots of 2 × 105 SW 480 cells in each lane treated with the AO to control inhibition of the PKC isotype expression in control cells (left lane) compared with cells treated with AO (right lane). To show that the applied amount of protein was equal in each lane, a beta actin immunostaining was performed.

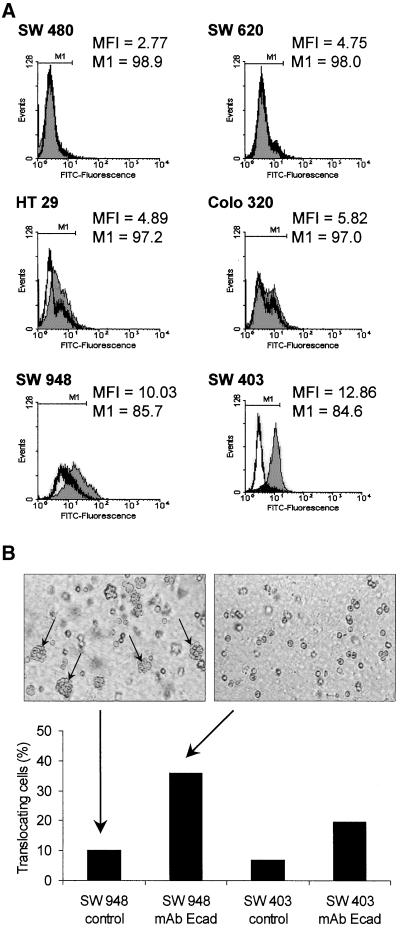

Analysis of the E-Cadherin Expression and Influence on Cell Migration

We also investigated the expression levels of E-Cadherin in all six colon carcinoma cell lines (Figure 5A). The metastatic cell line SW 620 and the grade III cell line SW 480 contained no detectable amounts of E-cadherin, whereas the cell lines HT 29, Colo 320, SW 948, and SW 403 expressed different levels of this adhesion molecule. With a mean fluorescence of 2.77, the cell line SW480 showed the lowest E-cadherin expression compared with the mean fluorescence intensity of 10.03 for the SW 948 cell lines and 12.86 for the SW 403 cell line. Analyzing the expression of specifically bound antibodies of each cell line compared the unspecific binding of an isotypic control, only these two cell lines, SW 948 and SW 403, revealed markedly higher expression of the E-cadherin–specific antibody (14.3% and 15.4%, E-cadherin-positive cells, respectively; Figure 5A). To give evidence for a functional dependence between displacement and E-cadherin content, we investigated the migratory activity by adding monoclonal blocking antibodies against E-cadherin. The SW 403 and SW 948 cell lines expressed high levels of E-cadherin but showed a spontaneous migratory activity of <10% locomoting cells. With the use of a E-cadherin–blocking antibody to prevent the development and rearrangement of cell clusters, we were able to increase the quantity of locomotory active cells to 36% in SW 948 cells and to 20% in SW 403 cells (Figure 5B). Screen shots of untreated SW 948 cells as well as of cells treated with the blocking antibody show that this antibody prevents the development of cell clusters, and therefore, increased single cell motility was observable.

Figure 5.

Determination of the E-cadherin expression of the colon carcinoma cell lines analyzed by flow cytometry. (A) Graphs show the expression of E-cadherin compared with the isotypic control (MFI, mean fluorescence intensity; M1, E-cadherin–positive cells compared with the marker region of the isotypic control adjusted to 99%). (B) Increase of the percentage of translocating SW 403 and SW 948 cells treated with E-cadherin–blocking antibodies compared with untreated cells (▪). Size of screen shots 400 × 600 μm2. Arrows, nonlocomotory cell clusters.

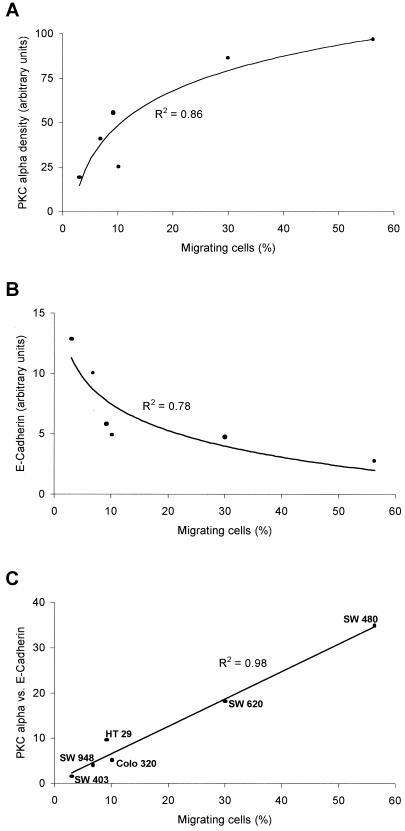

Correlations between Migration Activity, PKC α Density, and E-Cadherin Expression

In essence, the PKC α density of the six tumor cell lines showed a positive correlation (R2 = 0.88) to the migratory activity (Figure 6A). Cell lines with a high PKC α density showed a high rate of translocating cells. In turn, the cell surface expression of E-cadherin displayed a negative correlation (R2 = 0.78) to the quantity of migrating cells (Figure 6B), meaning that cells with a high amount of E-cadherin showed a limited displacement. Because not only the PKC α density was decisive for migration but also the content of E-cadherin, we calculated the quotient of the PKC α density and the E-cadherin content of the six colon carcinoma cell lines. This quotient correlates to the migratory activity of the cell lines and gives a nearly linear correlation (R2 = 0.98) (Figure 6C). In conclusion, the capability of the different human tumor cells for migratory activity is dependent on the expression of E-cadherin expressed on the cell surface as well as on the content of PKC α.

Figure 6.

Correlation between migratory activity, PKC α and E-cadherin expression. (A) Translocating cells vs. PKC α density displayed as logarithmic correlation (R2 = 0.86) showing a positive correlation between the spontaneous locomotory activity of the colon carcinoma cells and the of PKC α. (B) translocating cells vs. the expression of E-cadherin diagrammed as a curve showing a logarithmic correlation (R2 = 0.78). (C) Quotient of the PKC α density and E-cadherin vs. the percentage of translocating cells results in a correlation coefficient of R2 = 0.98.

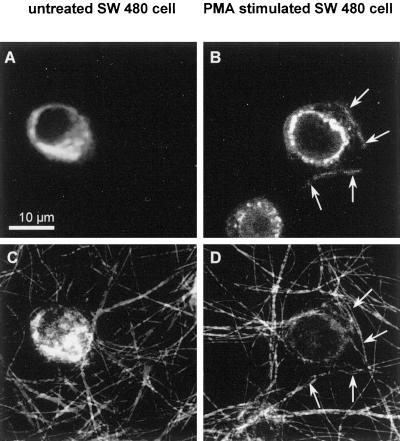

Translocation of the Activated PKC α to the Membranes

Translocation of the activated PKC from the cytoplasm to the membranes has been shown by various groups (Haller et al., 1998; Almholt et al., 1999; Gschwend et al., 2000). We investigated the displacement of PKC α after activation with PMA. Here we show that in the human colon carcinoma cell lines PKC α is translocated after activation to the plasma membrane as well as to the nuclear membrane (Figure 7B). At the plasma membrane PKC α was predominantly colocalized within contact areas of the cell to the surrounding collagen fibers (Figure 7D, colocalization is indicated by arrows.) Untreated control cells showed no translocation of PKC α (Figure 7A) and no colocalization of PKC α with the surrounding ECM (Figure 7C).

Figure 7.

Intracellular localization of PKC α. Immunofluorescence staining of PKC α–bound fluorescence. (A) Localization of PKC α within the cytoplasm of an untreated SW 480 cell, and (B) translocation of activated PKC α isozymes to the plasma membrane (arrows) as well as to the nuclear membrane. Reflection images of collagen fibers and of an untreated cell within a three-dimensional collagen matrix (C) and of an activated SW 480 cell (D). Arrows in B and D indicate the colocalization of activated PKC α (translocated to the plasma membrane) with the surrounding collagen fibers.

DISCUSSION

The migration of tumor cells comprises intensive interactions with the surrounding ECM. These interactions are managed by focal adhesion contacts (Burridge et al., 1988). Focal adhesions are multiprotein complexes that connect the ECM to the intracellular actin (Jockusch et al., 1995) and tubulin (Horwitz and Parsons, 1999) cytoskeletons via integrin receptors (Burridge et al., 1988; Hynes, 1992; Clark and Brugge, 1995). The flexible change between adhesive and nonadhesive states as well as the cytoskeletal rearrangement are regulated by enzymatically active proteins that are present in these focal adhesions (Entschladen and Zanker, 2000). Among them are the PKC isotypes, which have repeatedly and convincingly been shown to be associated with focal adhesions: the PKC α is associated with focal adhesions in rat embryo fibroblasts (Jaken et al., 1989; Liao et al., 1994). Adams et al. (Adams et al., 1999) established the matrix-initiated, PKC-dependent regulation of fascin phosphorylation at serine 39 as a mechanism whereby matrix adhesion is coupled to the organization of cytoskeletal structure.

The translocation of PKC α to the plasma membrane and the direct colocalization with the surrounding collagen fibers (arrows in Figure 7, B, D, and F) is a further indication of the involvement of PKC isozymes in the rearrangement of the cytoskeleton. Chapline et al. (Chapline et al., 1998) also showed that PKCs directly interact with a group of substrate proteins, STICKs (substrates that interact with C-kinase). These STICKs are involved in cytoskeletal remodeling, shown by immunostaining of actin depending on the phosphorylation state. Furthermore Ng et al. (1999) provided evidence for a key regulatory role of PKC isozymes for the β1 integrin traffic in migrating human breast carcinoma cells. Kiley et al. (Kiley et al., 1999) pointed toward an involvement of the PKC δ in tumor progression and cytoskeletal remodeling. Barry and Chritchley (1994) found out that PKC δ plays a central role in the regulation of focal adhesion contacts of Swiss 3T3 fibroblasts. TNF-α was shown to contribute to insulin resistance in rat adipocytes by altering PKC β translocation from the membrane to cytosol (Miura et al., 1999). Therefore, PKC isotypes have distinct functions in the regulation of different cellular signaling pathways.

We present here strong evidence for an involvement of the PKC α isotype in the regulation of colon carcinoma cell migration with the use of pharmacological inhibitors and genetic antisense oligonucleotide tools. The reduced migratory activity after treatment with the PKC δ–specific inhibitor rottlerin is probably due to a cross-reaction inhibition of the PKC α, because the results derived with PKC δ AOs did not support a functional role of this isotype in cell migration of colon carcinoma cell lines. At least, there was still a residual expression of each PKC isotype after treatment with the specific AO. Therefore, as mentioned before, we cannot completely exclude a minimal side effect of the PKC δ on the regulation of migration; however, the results clearly show the prominent role of the PKC α. Furthermore, the PKC α expression is positively correlated to the migratory activity of tumor cells but not to the differentiation grades. Frey et al. (1997) have shown in an elegant way, that PKC α in nontransformed intestinal epithelial cells plays an important role by regulating the growth via modulation of Cip/Kip family cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors and the retinoblastoma suppressor protein. Thus, the PKC α is a key enzyme in transformed and untransformed cells of the intestinal epithelium with respect to growth and migration regulation. However, downstream in the signal transduction pathway regulating the migratory activity, other PKC isotypes might be involved that need an activation by PKC α–dependent pathways. Such a functional link has been shown for the integrin phosphorylation by the PKC ζ in neutrophil granulocytes (Laudanna et al., 1998; Entschladen and Zanker, 2000).

With the use of phorbol esters as a positive control for induction of migration, we found that the PKC-activator PMA triggered the physical translocation of the PKC α isozyme from the cytosol to the plasma membrane of colon carcinoma cells as described by Almholt et al. (1999) in baby hamster kidney cells (Almholt et al., 1999). We could also show a translocation of PKC α isozymes to the nuclear membrane of SW 480 colon carcinoma cells, as described by Haller et al. in smooth muscle cells (Haller et al., 1998) and by Wagner et al. in fibroblasts (Wagner et al., 2000). Jaken et al. (1989)support the viewpoint that the PKC α is involved in the regulation of focal adhesion contacts.

Beside integrins, which are main constituents for the ECM–cell interactions in focal adhesion, other cytoskeletal adhesion molecules are involved in adhesive processes related to tumor cell migration. E-cadherin is an important adhesion molecule for cell–cell adhesions. The expression of an activated PKC α isotype alters the functionality of E-cadherin (Batlle et al., 1998), which results in low cell aggregations. Gabbert et al. (1996) showed, for gastric cancer tissue specimens, that the tumor differentiation grade correlates with the E-cadherin expression but not with the prognostic parameters such as the depth of invasion, the lymph node involvement, and the vascular invasion.

Because Batlle et al. (1998) provided evidence for a regulatory function of the PKC α in E-cadherin–mediated cell–cell interactions, we investigated the expression of E-cadherin. Interestingly, the level of E-cadherin expression of the six colon carcinoma cell lines was negatively correlated with the migratory activity of the cells. The higher the PKC α expression and the lower the E-cadherin expression was, the higher was the migratory activity of the tumor cells, leading to a strong linear correlation (R2 = 0.98).

Such a correlation between PKC α and E-cadherin expression, and locomotory activity was not only found for cells of different colon carcinoma cells but also for three bladder carcinoma cell lines (TCC-SUP, T 24, and HT 1376). The cell lines TCC-SUP and T 24 show a high spontaneous migratory activity (85 and 65% locomoting cells, respectively), whereas the HT 1376 cell line showed only minor locomotory activity (20% locomoting cells). Related to this, the two highly active cell lines exhibited a high expression level of PKC α, but no E-cadherin expression was detectable. In contrast the HT 1376 cells had a tenfold lower expression of PKC α and a high amount of E-cadherin on the cell surface.

In summary, a high level of PKC α expression simultaneously with a low E-cadherin level predicts an elevated migratory activity of colon carcinoma cells. However, this correlation is independent of the differentiation grade of the tumor cells.

Our results suggest, that the PKC α and E-cadherin expression of human intestinal cells underlies individual differences. As a consequence of these differences, the locomotory activity of human intestinal cells might differ individually. Maturating normal colon cells migrate from the crypta to the top of the villus. Cells with a high intrinsic PKC α and low E-cadherin expression would reach the top of the villus in a shorter period than cells with a low expression of PKC α and a high E-cadherin expression. In case of mutations and the development of a tumor, transformed cells with a high intrinsic PKC α and low E-cadherin expression would be more motile, and the likelihood to built metastases at early stages of the tumor growth is greater than in cells with a low PKC α and a high E-cadherin expression. However, the high motility of transformed cells might be an advantage, because these cells from which otherwise a solid tumor develops, quickly reach the top of the villus and are shed there by the peristaltic motion, except that these tumor cells acquire concomitantly with cell migration an invasive phenotype, entering the mucosa, submucosa, and adjacent lymph nodes to form solid metastases. This body of work can be taken as a database for understanding the processes that might underlie invasion and metastasis. However, in addition to the herein described involvements of the PKC α and E-cadherin, further signaling events remain to be elucidated.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Britta Reubke-Gothe for excellent technical assistance. This work was supported by the Deutsche Krebshilfe, Bonn, Germany, and the Fritz-Bender-Foundation, Munich, Germany.

Abbreviations used:

- AO

antisense oligonucleotides

- CC

calphostin C

- DAG

diacylglycerol

- ECM

extracellular matrix

- MARCKS

myristoylated, alanine-rich C kinase substrate

- PI

propidium iodide

- PKC

protein kinase C

- PMA

phorbol-12-myristate-13-acetate

REFERENCES

- Adams JC, Clelland JD, Collett GD, Matsumura F, Yamashiro S, Zhang L. Cell-matrix adhesions differentially regulate fascin phosphorylation. Mol Biol Cell. 1999;10:4177–4190. doi: 10.1091/mbc.10.12.4177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almholt K, Arkhammar PO, Thastrup O, Tullin S. Simultaneous visualization of the translocation of protein kinase Calpha-green fluorescent protein hybrids and intracellular calcium concentrations. Biochem J. 1999;337:211–218. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barry ST, Critchley DR. The RhoA-dependent assembly of focal adhesions in Swiss 3T3 cells is associated with increased tyrosine phosphorylation and the recruitment of both pp125FAK and protein kinase C-delta to focal adhesions. J Cell Sci. 1994;107:2033–2045. doi: 10.1242/jcs.107.7.2033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batlle E, Verdu J, Dominguez D, del Mont Llosas M, Diaz V, Loukili N, Paciucci R, Alameda F, de Herreros AG. Protein kinase C-alpha activity inversely modulates invasion and growth of intestinal cells. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:15091–15098. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.24.15091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruins RH, Epand RM. Substrate-induced translocation of PKC-alpha to the membrane. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1995;324:216–222. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1995.0033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brumell JH, Howard JC, Craig K, Grinstein S, Schreiber AD, Tyers M. Expression of the protein kinase C substrate pleckstrin in macrophages: association with phagosomal membranes. J Immunol. 1999;163:3388–3395. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruns RF, Miller FD, Merriman RL, Howbert JJ, Heath WF, Kobayashi E, Takahashi I, Tamaoki T, Nakano H. Inhibition of protein kinase C by calphostin C is light-dependent. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1991;176:288–293. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(91)90922-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burridge K, Fath K, Kelly T, Nuckolls G, Turner C. Focal adhesions: transmembrane junctions between the extracellular matrix and the cytoskeleton. Annu Rev Cell Biol. 1988;4:487–525. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.04.110188.002415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapline C, Cottom J, Tobin H, Hulmes J, Crabb J, Jaken S. A major, transformation-sensitive PKC-binding protein is also a PKC substrate involved in cytoskeletal remodeling. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:19482–19489. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.31.19482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark EA, Brugge JS. Integrins and signal transduction pathways: the road taken. Science. 1995;268:233–239. doi: 10.1126/science.7716514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clemens MJ, Trayner I, Menaya J. The role of protein kinase C isoenzymes in the regulation of cell proliferation and differentiation. J Cell Sci. 1992;103:881–887. doi: 10.1242/jcs.103.4.881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan E, Kelleher D, Feighery C, Long A. Protein kinase C isoform expression in CD45RA+ and CD45RO+ T lymphocytes. Immunology. 1995;85:299–303. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Entschladen F, Niggemann B, Zanker KS, Friedl P. Differential requirement of protein tyrosine kinases and protein kinase C in the regulation of T cell locomotion in three-dimensional collagen matrices. J Immunol. 1997;159:3203–3210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Entschladen F, Zanker KS. Locomotion of tumor cells. a molecular comparison to migrating pre- and postmitotic leukocytes. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2000;126:671–681. doi: 10.1007/s004320000143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filardo EJ, Deming SL, Cheresh DA. Regulation of cell migration by the integrin beta subunit ectodomain. J Cell Sci, 1996;109:1615–1622. doi: 10.1242/jcs.109.6.1615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flint AJ, Paladini RD, Koshland DE., Jr Autophosphorylation of protein kinase C at three separated regions of its primary sequence. Science. 1990;249:408–411. doi: 10.1126/science.2377895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frey MR, Saxon ML, Zhao X, Rollins A, Evans SS, Black JD. Protein kinase C isozyme-mediated cell cycle arrest involves induction of p21(waf1/cip1) and p27(kip1) and hypophosphorylation of the retinoblastoma protein in intestinal epithelial cells. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:9424–9435. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.14.9424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedl P, Maaser K, Klein CE, Niggemann B, Krohne G, Zanker KS. Migration of highly aggressive MV3 melanoma cells in 3-dimensional collagen lattices results in local matrix reorganization and shedding of alpha2 and beta1 integrins and CD44. Cancer Res. 1997;57:2061–2070. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedl P, Noble PB, Walton PA, Laird DW, Chauvin PJ, Tabah RJ, Black M, Zanker KS. Migration of coordinated cell clusters in mesenchymal and epithelial cancer explants in vitro. Cancer Res. 1995;55:4557–4560. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabbert HE, Mueller W, Schneiders A, Meier S, Moll R, Birchmeier W, Hommel G. Prognostic value of E-cadherin expression in 413 gastric carcinomas. Int J Cancer. 1996;69:184–189. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(19960621)69:3<184::AID-IJC6>3.0.CO;2-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gschwend JE, Fair WR, Powell CT. Bryostatin 1 induces prolonged activation of extracellular regulated protein kinases in, and apoptosis of LNCaP human prostate cancer cells overexpressing protein kinase calpha. Mol Pharmacol. 2000;57:1224–1234. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haller H, Lindschau C, Maasch C, Olthoff H, Kurscheid D, Luft FC. Integrin-induced protein kinase Calpha and Cepsilon translocation to focal adhesions mediates vascular smooth muscle cell spreading. Circ Res. 1998;82:157–165. doi: 10.1161/01.res.82.2.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herget T, Oehrlein SA, Pappin DJ, Rozengurt E, Parker PJ. The myristoylated alanine-rich C-kinase substrate (MARCKS) is sequentially phosphorylated by conventional, novel and atypical isotypes of protein kinase C. Eur J Biochem. 1995;233:448–457. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1995.448_2.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hochegger K, Partik G, Schorkhuber M, Marian B. Protein-kinase-C iso-enzymes support DNA synthesis and cell survival in colorectal-tumor cells. Int J Cancer. 1999;83:650–656. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19991126)83:5<650::aid-ijc14>3.0.co;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann J. The potential for isoenzyme-selective modulation of protein kinase C. FASEB J. 1997;11:649–669. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.11.8.9240967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horwitz AR, Parsons JT. Cell migration—movin'on. Science. 1999;286:1102–1103. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5442.1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huttenlocher A, Lakonishok M, Kinder M, Wu S, Truong T, Knudsen KA, Horwitz AF. Integrin and cadherin synergy regulates contact inhibition of migration and motile activity. J Cell Biol. 1998;141:515–526. doi: 10.1083/jcb.141.2.515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hynes RO. Integrins: versatility, modulation, and signaling in cell adhesion. Cell. 1992;69:11–25. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90115-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaken S, Leach K, Klauck T. Association of type 3 protein kinase C with focal contacts in rat embryo fibroblasts. J Cell Biol, 1989;109:697–704. doi: 10.1083/jcb.109.2.697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jockusch BM, Bubeck P, Giehl K, Kroemker M, Moschner J, Rothkegel M, Rudiger M, Schluter K, Stanke G, Winkler J. The molecular architecture of focal adhesions. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 1995;11:379–416. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.11.110195.002115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiley SC, Clark KJ, Goodnough M, Welch DR, Jaken S. Protein kinase C delta involvement in mammary tumor cell metastasis. Cancer Res. 1999;59:3230–3238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laemmli UK. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laudanna C, Mochly-Rosen D, Liron T, Constantin G, Butcher EC. Evidence of zeta protein kinase C involvement in polymorphonuclear neutrophil integrin-dependent adhesion and chemotaxis. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:30306–30315. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.46.30306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leibovitz A, Stinson JC, McCombs W B, 3rd, McCoy CE, Mazur KC, Mabry ND. Classification of human colorectal adenocarcinoma cell lines. Cancer Res. 1976;36:4562–4569. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao L, Ramsay K, Jaken S. Protein kinase C isozymes in progressively transformed rat embryo fibroblasts. Cell Growth Differ. 1994;5:1185–1194. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maaser K, Wolf K, Klein CE, Niggemann B, Zanker KS, Brocker EB, Friedl P. Functional hierarchy of simultaneously expressed adhesion receptors: integrin alpha2beta1 but not CD44 mediates MV3 melanoma cell migration and matrix reorganization within three-dimensional hyaluronan-containing collagen matrices. Mol Biol Cell. 1999;10:3067–3079. doi: 10.1091/mbc.10.10.3067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miura A, Ishizuka T, Kanoh Y, Ishizawa M, Itaya S, Kimura M, Kajita K, Yasuda K. Effect of tumor necrosis factor-alpha on insulin signal transduction in rat adipocytes: relation to PKCbeta and zeta translocation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1999;1449:227–238. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4889(99)00016-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng T, Shima D, Squire A, Bastiaens PI, Gschmeissner S, Humphries MJ, Parker PJ. PKCalpha regulates beta1 integrin-dependent cell motility through association and control of integrin traffic. EMBO J. 1999;18:3909–3923. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.14.3909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishizuka Y. The molecular heterogeneity of protein kinase C and its implications for cellular regulation. Nature. 1988;334:661–665. doi: 10.1038/334661a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pears C, Stabel S, Cazaubon S, Parker PJ. Studies on the phosphorylation of protein kinase C-alpha. Biochem J. 1992;283:515–518. doi: 10.1042/bj2830515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn LA, Moore GE, Morgan RT, Woods LK. Cell lines from human colon carcinoma with unusual cell products, double minutes, and homogeneously staining regions. Cancer Res. 1979;39:4914–4924. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radominska-Pandya A, Chen G, Czernik PJ, Little JM, Samokyszyn VM, Carter CA, Nowak G. Direct interaction of all trans-retinoic acid with protein kinase C. Implications for PKC signaling and cancer therapy. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:22324–22330. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M907722199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rigot V, Lehmann M, Andre F, Daemi N, Marvaldi J, Luis J. Integrin ligation and PKC activation are required for migration of colon carcinoma cells. J Cell Sci. 1998;111:3119–3127. doi: 10.1242/jcs.111.20.3119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Kleist S, Chany E, Burtin P, King M, Fogh J. Immunohistology of the antigenic pattern of a continuous cell line from a human colon tumor. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1975;55:555–560. doi: 10.1093/jnci/55.3.555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner S, Harteneck C, Hucho F, Buchner K. Analysis of the subcellular distribution of protein kinase Calpha using PKC-GFP fusion proteins. Exp Cell Res. 2000;258:204–214. doi: 10.1006/excr.2000.4925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]