Abstract

Purpose

To examine prevalence and correlates of health-risk behaviors in 12–17.5 year olds investigated by child welfare and compare risk-taking over time and with a national school-based sample.

Methods

Data from the National Survey of Child and Adolescent Well-being (NSCAW II) were analyzed to examine substance use, sexual activity, conduct behaviors, and suicidality. In a weighted sample of 815 adolescents aged 12–17.5 years, prevalence and correlates for each health-risk behavior were calculated using bivariate analyses. Comparisons to data from NSCAW I and the Youth Risk Behavior Survey were made for each health-risk behavior.

Results

Overall, 65.6% of teens reported at least one health-risk behavior with significantly more teens in the 15–17.5 year age group reporting such behaviors (81.2% vs 54.4%, p≤0.001). Almost 75% of teens with a prior out-of-home placement and 77% of teens with CBCL scores ≥ 64 reported at least one health-risk behavior. The prevalence of smoking was lower than in NSCAW I (10.5% vs. 23.2%, p ≤0.05) as was that of sexual activity (18.0% vs. 28.8%, p≤0.05). Prevalence of health-risk behaviors was lower among older teens in the NSCAW II sample (n=358) compared to the 2011 YRBS high school-based sample with the exception of suicidality, which was approximately 1.5 times higher (11.3% (95% CI: 6.5%, 19.0%) vs 7.8% (95% CI: 7.1%, 8.5%)).

Conclusion

Health-risk behaviors in this population of vulnerable teens are highly prevalent. Early efforts for screening and interventions should be part of routine CWS monitoring.

Keywords: adolescent, teens, health-risk behavior, social risk, child welfare, child welfare investigation, foster care, National Survey of Child and Adolescent Well-Being

Introduction

Health-risk behaviors in adolescents are common and challenging for parents, educators, and the health care system. Rates of substance use, risky sexual behaviors, and misconduct vary across population-based studies; however, the prevalence of such behaviors is high, regardless of the study sample. These behaviors are a major public health concern targeted by Healthy People 2020,1 not only because they may lead to morbidity and mortality in adolescence,2,3 but also because they contribute to poor health throughout adulthood.4,5

Prior research suggests that teens who have been victims of maltreatment may be at higher risk for a number of health-risk behaviors.6–8 Existing research varies considerably in methodology from population-based, cross-sectional surveys9–10 to prospective cohort studies with matched controls,7,11 a number of which were initiated several decades ago. Results are mixed, in that several studies show that some health-risk behaviors such as alcohol use, drug use, and suicidality are consistently higher among teens who have experienced maltreatment,7,9,10 while others suggest that substantiated maltreatment does not have a strong clear link with risk into adulthood for alcohol use11 or drug use.12 Prior research is also limited with respect to the association between health-risk behaviors and different levels of involvement with child welfare services among teens. Most studies examining teens involved with child welfare focus on those who are placed in foster care,13–16 despite the fact that teens investigated for child maltreatment are far more likely to remain at home following investigation than to be placed out of home.15,17 Data from the 2000 National Household Survey on Drug Abuse suggest that adolescents aged 12–17 who had ever been in foster care had a higher prevalence of psychiatric symptoms, drug use disorders, and suicide attempts than those never placed in foster care.13 Two prior studies, both based on the National Survey of Child and Adolescent Well-Being (NSCAW I), a nationally representative, longitudinal study of children ages birth to 14 years, did include children who remained in their homes. One examined health-risk behaviors in teens referred to child welfare and found that almost half of teens 12–14 endorsed at least one health-risk behavior.18 Using the same data, Orton and colleagues identified that 19% used an illegal substance in the past 30 days.19 While these studies evaluated children living in both out-of-home and in-home placements, only younger teens ages 12–14 were included in NSCAW I.

This study examines data from the second National Survey of Child and Adolescent Well-being (NSCAW II), a nationally representative sample of children up to age 17.5 years who were investigated due to suspected maltreatment ten years after NSCAW I. Teens in this sample, especially those who remained at home, represent a population at risk that has not been extensively studied in previous reports of health-risk behaviors in children. Using data from this national cohort, we examine the prevalence and correlates of health-risk behaviors for the full age range of teens from 12–17.5 years investigated by child welfare, including those who remain at home and those placed in foster care. Further, for younger teens (12–14 year of age), we compare the prevalence of health-risk behaviors reported in NSCAW II to those reported in NSCAW I to examine trends in health-risk behaviors among younger teens over the course of a decade to understand secular changes that may be occurring in health-risk behaviors among teens in contact with child welfare. Finally, for older teens, we compare rates of health-risk behaviors in teens referred to child protection to teens responding to the Youth Risk Behavior Survey, a national school-based survey conducted among students in grades 9–12.

Methods

Design and Analytic Sample

We used data from NSCAW II, a three-year longitudinal study of 5,872 youth ages 0–17.5 years referred to US child welfare agencies, for whom an investigation of potential maltreatment was completed during the sampling period, February, 2008 to April, 2009. The study excluded agencies in eight states in which law required first contact of a caregiver by agency staff rather than by study staff. Data from initial interviews were collected within approximately 4 months of completed child welfare investigations. NSCAW II, like its predecessor NSCAW I, employed a two stage stratified sample design. The first stage selected geographic areas containing a population served by a single child welfare agency. These primary sampling units (PSUs), typically counties, served as the basis from which a sample of children was drawn. NSCAW II used NSCAW I PSUs whenever possible. Of the 92 NSCAW I PSUs, 71 were eligible and agreed to participate in NSCAW II and 10 additional PSUs were added to replace the PSUs not participating. This sample was constructed to be representative of all children in the United States who were subjects of agencies’ investigations for alleged maltreatment during the sampling period.20 These data come from the baseline interviews completed between March, 2008 and September, 2009. Analyses reported in this manuscript used data only on children ≥12 years of age at the time of the baseline interview (N=815) and their caregivers. All procedures for NSCAW II were approved by the Research Triangle Institute’s IRB and all analytic work on the NSCAW II de-identified data by the Rady Children’s Hospital IRB.

Additional analyses for specific health-risk behaviors described below utilized comparative data from two sources. For children aged 12–14 years, we used comparison data from NSCAW I. Sampling strategies in NSCAW I were the foundation for NSCAW II and have been described elsewhere.20 Sampling strategies in the two NSCAW studies, a decade apart, were designed to generate estimates of the same national population of children for whom a child welfare investigation occurred. For children aged 15–17.5 years, we used comparison data from the 2011 Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System (YRBS), a national school-based survey conducted by the CDC in 47 states, six territories, two tribal government jurisdictions, and 22 localities. The surveys were conducted among students in grades 9–12 during October 2010—February 2011, and included questions on several types of health-risk behaviors that contribute to leading causes of death and disability among youth and adults.3,21–23 The national YRBS uses a three-stage, cluster sample design to produce a nationally representative sample of students in grades 9–12 in the 50 states and the District of Columbia. The methodology for this sampling has been described in detailelsewhere.23

Measures

Sociodemographic variables included child’s age, sex, race, location of placement, type of alleged maltreatment, and prior history of involvement with child welfare. Placement was described as in-home without ongoing child welfare services (CWS), in-home with continuing CWS, non-relative foster care, or kinship care (formal and informal). Adolescents who were placed in group or residential settings were not included in these analyses because of small numbers (N =69) and because group homes/residential placement are used as a therapeutic modality for the outcomes assessed in this study. Adolescents’ behavioral functioning was assessed using the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL), which was administered to caregivers. The CBCL consists of 120 items related to behavior problems, scored on a 3-point scale ranging from “not true” to “often true.” Raw scores are converted to T-scores with a total T-score of ≥64 considered clinically significant.24

Health-Risk Behaviors

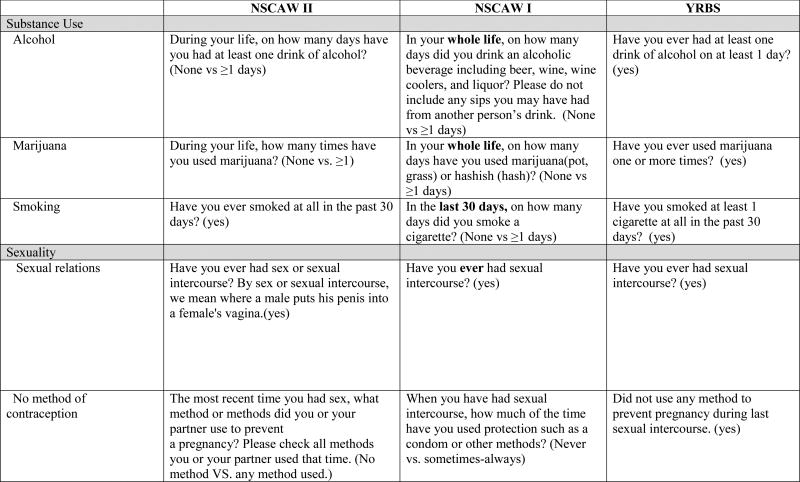

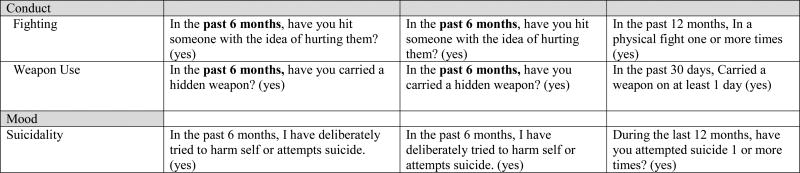

Outcomes of interest in this study were the following health-risk behaviors: substance use (lifetime alcohol use, lifetime marijuana use, smoking in the past 30 days), sexual activity (has ever had sexual relations, no method of contraception used during last sexual contact among those who answered “yes” to having had sexual relations), conduct (endorsed fighting, carried a weapon in the past 6 months), and suicidality. Figure 1 summarizes the content of each question from each of the three data sources used in this study.

Figure 1.

Specific Questions from 3 National Surveys

Analyses

All analyses used weighted data. Analysis weights for NSCAW I and II were constructed in stages corresponding to the stages of the sample design, accounting for the probability of county selection and the probability of each child’s selection within a county, given the youth’s county of residence. Weights were further adjusted to account for population differences from those expected, small deviations from the original plan that occurred during sampling, and for non-response patterns and for replacement PSUs. The weighting process for NSCAW II was more complex than for NSCAW I.20 Non-weighted cell sizes are presented for some analyses to provide detail about the amount of data upon which analyses are based. All NSCAW parameters (i.e., means, percentages, etc.) were generated using the weights and can be inferred to the U.S. child welfare population.20

For the YRBS sample, weights based on student sex, race/ethnicity and school grade were applied to each record to adjust for student non-response and oversampling of black and Hispanic students. The weighted estimates are representative of all students in grades 9–12 who attend private and public schools in the United States.23

Analyses utilized descriptive statistics to summarize the percentage of individuals who endorsed any of the health-risk behaviors. Significance of bivariate associations was assessed using Chi-Square for categorical variables. The customary level of statistical significance, p≤0.05, was used in all analyses. Additional multivariate analyses were run for the outcomes of alcohol use, unprotected sex, and suicidality. For 12–14 year-olds, the prevalence of health-risk behaviors was compared between NSCAW I and II. Finally, the prevalence of health-risk behaviors and associated 95% confidence intervals were calculated among 15–17.5 year-olds in NSCAW II and the 9–12th grade YRBS sample. All NSCAW analyses were conducted using SAS-Callable SUDAAN, version 11.0.25 All YRBS percentages came from the Center for Disease Control website.22

Results

Table 1 shows health-risk behaviors of teens in the NSCAW II sample at the initial assessment (Wave 1). Overall, 65.6% of teens reported at least one health-risk behavior, with significantly more teens in the 15–17.5 year age group reporting such behaviors (81.2% vs 54.4%, p≤0.001). Almost 75% of teens with a prior out-of-home placement and 77% of teens with CBCL scores ≥ 64 reported at least one health-risk behavior. Substance use, particularly alcohol and marijuana use, was significantly higher in older teens. Marijuana use was more prevalent in teens with prior out-of-home placement and higher CBCL scores (p ≤0.01, p ≤ 0.05, respectively). Smoking was reported more often among teens who had not been previously reported to CWS and among those with higher CBCL scores. (p ≤0.05). Risky sexual activity was more prevalent in older teens, those with prior out-of-home placement and among those with higher CBCL scores. No use of any contraception among those who reported prior sexual relations was endorsed more by females (28.3% vs 8.2%, p ≤0.05), teens who reported physical or sexual abuse (37.4%) compared to neglect (3.5%) or other types of abuse (8.7%. p≤0.001, p≤0.05 respectively), and among teens without prior out of home placement (22.2% vs. 5.4%, p≤0.05). There were statistically significant differences in rates of fighting among those teens with prior reports of maltreatment (17.3% vs 8.6%, p≤0.05) and weapon carrying among teens with prior out-of-home placement and with higher CBCL scores. Finally, suicidality was endorsed more often by females than males (19.0 vs 6.4%, p≤0.01), those who reported physical or sexual abuse (21.5% vs. 10.4% and 7.9%, p≤0.05, p≤0.001 respectively), and by teens with higher CBCL scores (29.0% vs. 7.3%, p ≤0.01). Suicidality was reported less often by black teens (5.0%) compared to white (12.9%) and Hispanic (18.5%) teens, and teens of other race/ethnicity (23.3%, p≤0.05 for all comparisons).

Table 1.

NSCAW II, wave 1 data (n=815): Health-risk Behaviors by Teen Sociodemographic, Placement and Caregiver Characteristics

| Any Health-risk behaviors |

Substance use | Sexuality | Conduct | Mood | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alcohol life time |

Marijuana life time |

Smoked past 30 days |

Sexual relations |

No method of contraceptionŧ |

Fighting | Weapon | Suicidality | ||

| %(se) | %(se) | %(se) | %(se) | %(se) | %(se) | %(se) | %(se) | %(se) | |

| Total | 65.6(2.4) | 47.7(2.9) | 26.1(2.8) | 14.4(1.9) | 33.7(2.4) | 19.9(3.4) | 15.2(2.3) | 7.0(1.2) | 13.9(2.2) |

| Child age | *** | *** | *** | *** | |||||

| 12–14 | 54.4(3.5) | 37.8(3.0) | 15.2(1.9) | 11.0(2.4) | 19.2(2.8) | 26.4(5.1) | 14.4(2.9) | 4.6(1.3) | 15.9(2.9) |

| 15–17 | 81.2(3.3) | 61.2(4.5) | 40.8(5.0) | 19.0(3.4) | 53.2(4.2) | 16.8(3.8) | 16.2(3.0) | 10.1(2.5) | 11.3(3.1) |

| Child sex | * | ** | |||||||

| Male | 63.4(4.2) | 46.0(3.9) | 27.4(4.4) | 12.0(2.9) | 34.9(3.8) | 8.2(3.8) | 15.9(3.2) | 9.2(2.4) | 6.4(2.1) |

| Female | 67.2(2.9) | 48.9(3.7) | 25.2(3.0) | 16.1(2.7) | 32.9(3.1) | 28.3(5.7) | 14.7(3.1) | 5.5(1.5) | 19.0(3.3) |

| Child Race | * | ||||||||

| Black | 65.2(4.0) | 39.7(5.6) | 23.2(6.4) | 11.9(4.6) | 42.0(5.2) | 7.5(4.3) | 14.4(4.4) | 7.3(2.4) | 5.0(2.0) |

| White | 63.1(4.0) | 47.3(4.3) | 24.2(4.2) | 14.5(2.9) | 32.5(4.3) | 24.7(5.0) | 15.1(3.0) | 5.0(1.5) | 12.9(2.8) |

| Hispanic | 70.9(4.9) | 51.6(5.9) | 28.9(4.6) | 14.2(3.4) | 28.5(4.9) | 13.5(5.6) | 17.1(5.5) | 7.6(2.3) | 18.5(5.3) |

| Other | 67.4(7.2) | 55.5(8.2) | 34.0(9.8) | 20.1(8.0) | 42.8(9.3) | 37.7(16.7) | 11.6(5.8) | 14.3(6.7) | 23.3(9.6) |

| Primary Type of maltreatment | ** | * | |||||||

| Physical /Sexual abuse | 65.0(4.1) | 46.9(4.4) | 27.9(4.1) | 16.8(3.6) | 31.1(4.1) | 37.4(7.6) | 15.1(3.3) | 6.1(1.6) | 21.5(4.5) |

| Neglect | 60.0(4.6) | 34.0(5.5) | 16.7(4.0) | 9.1(2.9) | 32.2(4.9) | 3.5(2.6) | 10.3(3.3) | 5.9(2.4) | 10.4(3.2) |

| Other Abuse | 65.4(5.5) | 50.9(6.1) | 27.1(5.3) | 17.1(3.5) | 35.5(5.2) | 8.7(4.0) | 18.7(5.5) | 8.5(3.1) | 7.9(2.1) |

| Child placement | |||||||||

| IH no CWS | 65.9(3.5) | 50.0(4.1) | 23.1(3.4) | 13.6(2.7) | 31.9(3.7) | 23.2(5.3) | 13.2(3.3) | 5.2(1.5) | 14.9(3.5) |

| IH, with CWS | 63.6(3.6) | 44.5(4.7) | 24.9(3.6) | 17.6(3.4) | 33.1(4.5) | 19.6(5.5) | 14.6(3.4) | 6.1(1.5) | 14.3(2.5) |

| Foster Home | 67.7(8.0) | 51.2(8.7) | 31.7(7.2) | 8.1(2.7) | 43.6(7.6) | 12.6(4.9) | 17.4(3.9) | 6.4(2.5) | 13.9(6.2) |

| Formal/Informal Kin | 68.0(7.1) | 43.5(8.2) | 40.0(8.4) | 13.3(4.7) | 39.6(8.2) | 11.7(7.3) | 24.2(8.1) | 16.1(5.0) | 9.1(4.0) |

| Any prior reports of maltreatment | * | * | |||||||

| Yes | 63.0(3.3) | 41.7(4.2) | 23.3(3.5) | 11.1(2.2) | 32.8(3.3) | 18.6(4.4) | 17.3(3.3) | 6.3(1.5) | 13.9(2.6) |

| No | 65.8(4.3) | 53.9(4.3) | 30.7(5.5) | 24.6(5.0) | 36.5(5.0) | 13.5(6.6) | 8.6(1.8) | 7.7(2.6) | 11.9(3.0) |

| # OOH prior to W1 interview date | * | ** | * | * | * | ||||

| 0 | 61.3(2.8) | 44.0(3.5) | 19.1(2.6) | 14.0(2.5) | 29.3(2.7) | 22.2(4.9) | 12.9(2.6) | 4.2(1.2) | 13.2(2.4) |

| 1+ | 74.8(5.5) | 53.8(6.5) | 44.7(7.2) | 14.8(4.6) | 46.6(7.0) | 5.4(1.9) | 22.5(6.6) | 14.3(3.8) | 10.4(3.6) |

| Teen Behavioral functioning (CBCL scores) | ** | * | * | * | * | ** | |||

| >=64 | 77.0(4.1) | 53.1(4.5) | 33.0(4.0) | 23.7(4.3) | 42.8(4.7) | 28.7(7.6) | 21.4(5.2) | 13.4(2.8) | 29.0(5.5) |

| <64 | 59.5(3.1) | 45.1(3.7) | 22.0(2.9) | 10.5(1.9) | 28.7(2.7) | 11.6(3.1) | 11.9(2.8) | 4.1(1.2) | 7.3(2.5) |

p ≤ 0.05,

p ≤ 0.01,

p ≤ 0.001

(among teens who had reported sexual relations)

Table 2 shows prevalence of health-risk behaviors by age and placement location. Regardless of where teens lived or were placed after investigation, older teens reported higher rates of at least one health-risk behavior. Older teens living at home after investigation without continuing CWS involvement reported statistically higher rates of alcohol and marijuana use, and sexual activity compared with younger teens. Similar patterns were seen among teens who remained at home with continuing CWS involvement; older teens reported more alcohol and marijuana use and sexual activity. Interestingly, a higher percentage of younger teens at home with continuing CWS involvement endorsed suicidality (18.0 vs 8.2%, p ≤0.05). Among teens in foster care, significant differences were observed between older and younger teens for marijuana use (43.4% vs 15.4%, p ≤0.05), sexual activity (59.3 vs 21.7%, p≤0.05) and no method of contraception among sexually active teens (46.1% vs 3.8%, p≤0.05). Standard errors were also larger for this subgroup because of its smaller sample size. Older teens in kinship care had significantly higher rates of most health-risk behaviors with the exception of three: no use of contraception, fighting, and suicidality.

Table 2.

NSCAW II, wave 1 data, Health-risk Behaviors by Age and Placement Location

| Any Health-risk behaviors |

Substance use | Sexuality | Conduct | Mood | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alcohol life time |

Marijuana life time |

Smoked past 30 days |

Sexual relations |

No method of contraceptionŧ |

Fighting | Weapon use | Suicidality | ||

| %(se) | %(se) | %(se) | %(se) | %(se) | %(se) | %(se) | %(se) | %(se) | |

| IH no CWS | ** | * | ** | ** | |||||

| 12–14 | 56.0(5.2) | 43.1(5.2) | 13.8(2.4) | 11.2(3.7) | 20.8(4.5) | 23.8 (6.5) | 12.7(4.4) | 4.8(2.1) | 16.8(4.6) |

| 15–17 | 81.2(4.8) | 60.4(5.6) | 36.7(7.3) | 17.1(4.8) | 48.3(6.9) | 22.8(7.7) | 13.9(4.0) | 5.8(2.4) | 12.0(5.1) |

| IH CWS | *** | ** | * | *** | * | ||||

| 12–14 | 52.4(3.5) | 34.6(3.5) | 16.0(3.4) | 14.1(4.4) | 16.3(3.2) | 26.9(10.3) | 15.8(3.5) | 5.0(1.7) | 18.0(3.2) |

| 15–17 | 82.2(6.2) | 60.9(8.4) | 39.3(8.5) | 23.2(4.6) | 60.6(6.9) | 16.4(6.6) | 12.5(4.1) | 8.1(4.0) | 8.2(3.1) |

| Foster | * | * | * | * | |||||

| 12–14 | 42.9(10.9) | 34.2(10.0) | 15.4(6.6) | 4.9(3.0) | 21.7(7.7) | 46.1(12.8) | 18.2(6.6) | 2.4(2.1) | 10.7(5.0) |

| 15–17 | 85.8(5.2) | 63.4(11.0) | 43.4(9.9) | 10.3(4.4) | 59.3(10.2) | 3.8(2.5) | 16.9(5.1) | 9.2(4.2) | 15.8(9.3) |

| Formal/Informal Kin | ** | * | * | * | * | ||||

| 12–14 | 53.7(10.8) | 16.8(6.0) | 20.6(8.2) | 1.6(1.1) | 17.8(9.0) | 36.1(24.2) | 18.6(10.2) | 3.1(2.2) | 4.9(2.1) |

| 15–17 | 78.3(8.1) | 63.1(10.0) | 54.3(10.8) | 21.7(8.0) | 55.9(10.3) | 5.8(3.6) | 28.3(11.0) | 25.8(8.3) | 12.1(7.0) |

p ≤ 0.05,

p ≤ 0.01,

p ≤ 0.001

(among teens who had reported sexual relations)

Multivariate models examined three health-risk behaviors that contribute most significantly to mortality and morbidity for teens: alcohol use, unprotected sex, and suicidality. These models confirmed the independent contributions of age, sex, prior out of home placement and high CBCL score to health-risk outcomes (tables not shown).

To assess prevalence of health-risk behaviors among younger teens over the past decade, data from NSCAW I and II were compared as shown in Table 3. The prevalence of smoking in NSCAW II was half what it was in NSCAW I (10.5% vs. 23.2%, p ≤0.05), and the prevalence of sexual activity was lower in NSCAW II as well (18.0% vs. 28.8% ,p ≤0.05). Although the prevalence of suicidality was higher in NSCAW II, this difference did not reach statistical significance.

Table 3.

Trends in Teen Health-risk Behaviors for Younger Teens: NSCAW I and NSCAW II

| NSCAW I | NSCAW II | |

|---|---|---|

| 12–14 years (n=654, 50.9%) |

12–14 years (n=444, 49.1%) |

|

| %(se) | %(se) | |

| Any risk problems | 59.8(4.5) | 53.9(3.7) |

| Alcohol life time use | 43.4(3.7) | 37.9(3.2) |

| Marijuana life time use | 17.9(4.4) | 15.4(2.0) |

| Smoke past 30days | 23.2(3.8)* | 10.5(2.2) |

| Sexual relations | 28.8(5.1)* | 18.0(2.4) |

| No method of contraception | 22.3(8.7) | 24.6 (5.5) |

| Fighting | 12.9(2.9) | 13.8(2.9) |

| Use of Weapon | 7.7(2.3) | 4.7(1.4) |

| Suicidality | 11.1(2.8) | 15.6(2.8) |

p ≤ 0.05

Finally, Table 4 shows that rates of health-risk behaviors among older teens in the NSCAW II sample (n=358) compared to the 2011 YRBS national sample are similar. However, fighting was reported by more teens in the YRBS sample 32.8% (95% Confidence Interval (CI): 31.5%, 34.1%) vs. 16.2% (95% CI: 11.1%, 23.1%). Suicidality among the teens with CWS involvement was approximately 1.5 times higher than the YRBS sample (11.3% (95% CI: 6.5%, 19.0% vs 7.8% (95% CI: 7.1%, 8.5%).

Table 4.

Comparison of Health-risk Behaviors in Older Teens Investigated by CWS with School-based Sample

| NSCAW II | YRBS 2011 | |

|---|---|---|

| 15–17.5 year old (n=358) |

9–12 graders | |

| % (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | |

| Any risk problems | 81.2(73.7–86.9) | -- |

| Alcohol life time use | 61.2(51.9–69.7) | 70.8 (69.0–72.5) |

| Marijuana life time use | 40.8(31.3–51.2) | 39.9 (37.8–42.1) |

| Smoke past 30days | 19.0(13.1–26.8) | 18.1(16.7–19.5) |

| Sexual relations | 53.2(44.8–61.5) | 47.4 (45–49.9) |

| No Method of contraception | 16.8 (10.4–25.8) | 12.9 (11.6–14.2) |

| Fighting | 16.2(11.1–23.1) | 32.8 (31.5–34.1) |

| Use of Weapon | 10.1(6.1–16.3) | 16.6 (15.4–18.0) |

| Suicidality | 11.3(6.5–19.0) | 7.8 (7.1–8.5) |

Discussion

This study shows high rates of health-risk behaviors in this sample of adolescents investigated by US child welfare services for alleged maltreatment. In our sample, 65.6% of teens reported at least one health-risk behavior, with significantly more teens in the 15–17.5 year age group reporting risky behaviors. Similar to findings in broader population studies, older adolescents reported a higher likelihood than younger adolescents of having engaged in a number of health-risk behaviors including use of alcohol and marijuana and sexual activity.22,26 Given that some questions asked about lifetime engagement in specific behaviors (e.g., alcohol and marijuana use, sex), it is not surprising that prevalence rates are higher in older teens.

Gender and race/ethnicity were also related to the likelihood of engagement in health-risk behaviors. Females were much more likely than males to report having attempted to harm themselves or commit suicide, black youth were much less likely to report having engaged in most health-risk behaviors, especially suicidality than youth from other race/ethnic backgrounds. Both of these results are consistent with findings from broader population studies of adolescent engagement in health-risk behaviors.21,22 Prior research has found that black teens score higher on measures of individualism than do white teens, which may lower suicide rates by enhancing self-esteem, and that rural residence and strong social support are also protective factors.27,28

The most consistent predictor of engagement in health-risk behaviors was adolescent mental health. Adolescents with CBCL scores above the clinical cut-off were much more likely to report having used marijuana, smoked, had sex (and unprotected sex), and attempted to harm themselves or commit suicide. With regard to self-harmful behavior, teens with clinical level mental health concerns were over 3 times more likely to report such behavior than those below the clinical cutoff, with 29% reporting having engaged in such behavior in the last 6 months. This finding is consistent with previous literature showing the relationship between poor mental health functioning and high rates of health-risk behaviors.29,30

Our analyses also revealed that frequency of health-risk behaviors was relatively similar across different living situations and placement types. Adolescents remaining at home without CWS reported rates of engagement in health-risk behaviors similar to those of adolescents placed in non-relative or formal and informal kinship care, with one exception. Our data suggest that children who remained in home with or without continuing CWS involvement had high rates of suicidality, especially younger teens. Further, over the past decade, prevalence of suicidality among younger teens has not dropped significantly. This is concerning and is consistent with past research that shows the association between maltreatment and higher prevalence of suicidality in teens in both cross-sectional, population-based studies, and prospective cohort studies.7,10,31 The stressful life events that brought the family into the child welfare system may remain present and can disrupt the development of healthy coping skills. Unlike younger children, teens investigated for child maltreatment are more likely to remain at home following investigation15,17 and may receive fewer services than teens in foster care that potentially could address their risky health behaviors.32

Rates of occurrence of most health-risk behaviors were relatively unchanged for teens examined in NSCAW I and in NSCAW II, sampled about a decade apart. The exceptions were smoking and engagement in sex, two health-risk behaviors that have been declining at a broader population level over the course of the last decade.22,33,34 Such reductions must be considered in the context of secular changes in norms for all youth, including those in contact with child welfare services, relative to individual experiences. Rates of smoking dropped by more than half across one decade and of early sexual involvement by 10%, both of which are considerable decreases. Such substantial decreases may be due to public anti-smoking education campaigns funded by the tobacco settlement as well as increased rates of condom use due to public health efforts, both of which occurred during the past decade.

Finally, rates of health-risk behaviors appeared to be fairly similar between youth coming into contact with child welfare services as for youth in the broader population of adolescents. In this study, due to limitations in the comparability of questions between data sets, we were only able to make comparisons of health-risk behaviors for a modest number of key risk behaviors including substance use, sexual behavior, conduct problems, and evidence of self-harm/suicide. Rates were relatively high for all teens. In some areas, teens with child welfare involvement reported lower rates of health-risk behaviors (e.g., fighting and carrying a weapon) than teens in the YRBS. This is striking given that the YRBS survey includes only teens who are in school and present on the day of the survey, which might result in a slight tendency toward underestimation of risk behaviors among all US adolescents. One might legitimately be concerned about whether teens with child welfare involvement might have an increased predisposition to under-report engagement in health-risk behaviors due to their involvement with child welfare. This possible explanation has been proposed by other investigators.17,35 This is certainly a possibility, but the YRBS was completed using pencil-and-paper, while NSCAW was completed using a computer-assisted audio survey that made answers to questions completely confidential. At the very least, the NSCAW survey methods substantially increased the likelihood of yielding data that would not be compromised by reporting bias due to concerns about confidentiality, but there is no way to assure completely that the adolescents trusted that confidentiality.

Although these data provide a unique opportunity to examine health-risk behaviors among teens in the child welfare system, they are not without limitations. Most of the variables examined, including the outcome variables, are self-reported by the teen and the teen’s caregiver with no independent corroboration. These data must also be interpreted in the context of the method of ascertainment, the assessment tools and the time frame considered for each of the health-risk behaviors examined. This study presented data on only those health-risk behaviors that we deemed close enough in measurement that comparisons could be presented, but it is always important to carefully consider the comparability of data collection methods across surveys. Ideally we would like to have been able to compare health-risk behaviors more comprehensively between surveys with regard to their occurrence and frequency. This report underscores that a “lack of standardization in the measurement of health and health care quality limits the ability to identify, monitor, and address persistent health disparities among children and adolescents.”36 The YRBS and NSCAW, among other data collection tools such as Monitoring the Future, and the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health (ADDHealth), all have strengths, yet the inconsistencies in measurement across these studies designed to understand the health of our nation’s youth hinders our ability to compare health status across samples and requires selective comparisons, such as seen in our study.

Our study highlights the fact that a nationally representative sample of teens involved with CWS face likelihoods of health-risk behaviors very similar to other youth in the country, suggesting that targeting these risks should occur at time points similar for children involved with CWS as for youth in the general population. All teens, but especially those who are already identified as at higher risk because of events that brought them to the attention of child protection, report high rates of health-risk behaviors. Although the priorities of the child welfare system are to ensure safety, permanency and well-being of children, historically the system has focused mostly on the first two priorities. Data from the Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study and recent biologic studies in epigenetics demonstrate that early childhood experiences have life-long consequences, especially on mood and suicidality.4,37–39 Our data suggest that early screening and on-going interventions for adolescent health-risk behaviors should be part of routine CWS monitoring at the initial point of contact for all teens, regardless of subsequent placement, and especially for younger teens.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) award P30-MH074678; PI: J. Landsverk and NIMH award P30-MH090322; PI: K. Hoagwood. We thank NIMH for the support but acknowledge that the findings and conclusions in this manuscript are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of NIMH. This document includes data from the National Survey of Child and Adolescent Well-Being, which was developed under contract with the Administration on Children, Youth, and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (ACYF/DHHS). The data have been provided by the National Data Archive on Child Abuse and Neglect. The information and opinions expressed herein reflect solely the position of the author(s). Nothing herein should be construed to indicate the support or endorsement of its content by ACYF/DHHS.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributions and Implications:

Using data from the first and second National Survey of Child and Adolescent Well-being (NSCAW I and II), this study reports on the prevalence and correlates of health-risk behaviors in adolescents investigated by US child welfare agencies. Additionally, the analysis compares changes in prevalence of health-risk behaviors for younger adolescents investigated by child welfare over a decade and compare rates among older adolescents to prevalence of these behaviors from a national school-based sample.

Contributor Information

Amy Heneghan, Palo Alto Medical Foundation and the Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine

Ruth E.K. Stein, Department of Pediatrics; Albert Einstein College of Medicine/Children’s Hospital at Montefiore, New York, NY

Michael S. Hurlburt, School of Social Work, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA

Jinjin Zhang, Child and Adolescent Services Research Center, Rady Children’s Hospital, San Diego, CA

Jennifer Rolls-Reutz, Child and Adolescent Services Research Center, Rady Children’s Hospital, San Diego, CA

Bonnie D. Kerker, Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, New York University School of Medicine, New York, NY; Nathan Kline Institute of Psychiatric Services, Orangeburg, NY.

John Landsverk, Child and Adolescent Services Research Center, Rady Children’s Hospital, San Diego, CA

Sarah McCue Horwitz, Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, New York University School of Medicine, New York, NY

References

- 1. [Accessed 9/13/14];Adolescent Health: Healthy people 2020. http://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topicsobjectives2020/overview.aspx?topicid=2.

- 2.Resnick MD, Bearman PS, Blum RW, Bauman KE, Harris KM, Jones J, Tabor J, Beuhring T, Sieving RE, Shew M, Ireland M, Bearinger LH, Udry JR. Protecting adolescents from harm: Findings from the National Longitudinal Study on Adolescent Health. JAMA. 1997;278:823–832. doi: 10.1001/jama.278.10.823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grunbaum JA, Kann L, Kinchen SA, Williams B, Ross JG, Lowry R, Kolbe L. Youth risk behavior surveillance--United States, 2001. J Sch Health. 2002 Oct;72(8):313–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2002.tb07917.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, et al. Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults: The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) study. Am J PrevMed. 1998;14:245–258. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(98)00017-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shonkoff JP, Garner AS, Siegel BS, Dobbins MI, Earls MF, et al. Technical Report: The lifelong effects of early childhood adversity and toxic stress. From The Committees on Psychosocial Aspects of Child and Family Health; Early Childhood, Adoption and Dependent Care, and Section on Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics. Pediatrics. 2012;129:1. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-2663. e232-e246; published ahead of print December 26, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hussey JM, Chang JJ, Kotch JB. Child Maltreatment in the United States: Prevalence, Risk Factors, and Adolescent Consequences. Pediatrics. 2006;118:933–942. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-2452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wilson HW, Windom CS. Predictors of Drug-Use Patterns in Maltreated Children, Matched Controls Followed up into Middle Adulthood. J Stud. Alcohol Drugs. 2010;71:801–809. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2010.71.801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Landsverk JA, Garland AF, Leslie LK. Mental health services for children reported to child protective services. In: Myers JE, Berliner L, Briere J, et al., editors. APSAC Handbook on Child Maltreatment. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2002. pp. 487–507. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kirkpatrick DG, Acierno R, Schnurr PP, Saunders B, Resnick HS, Best CL. Risk factors for adolescent substance abuse and dependence: Data for a national sample. J Counseling Clinical Psychology. 2000;68:19–30. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.68.1.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Riggs S, Alario AJ, McHorney C. Health-risk behaviors and attempted suicide in adolescents who report prior maltreatment. J Pediatrics. 1990;116:815–821. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(05)82679-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Windom Windom CP, White HR, Czaja SJ, Marmorstein NR. Long-term effects of Child abuse and neglect on alcohol use and excessive drinking in middle adulthood. J. Stud. Alcohol Drugs. 2007;68:317–326. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2007.68.317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wilson HW, Windom CS. The role of youth problem behaviors in the path from child abuse and neglect to prostitution: A prospective examination. J of Research on Adolescence. 2010;20:210–236. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2009.00624.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pilowsky DJ, Wu LT. Psychiatric symptoms and substance use disorders in a nationally representative sample of American adolescents involved with fostercare. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2006;38:351–358. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Keller TE, Salazar AM, Courtney ME. Prevalence and timing of diagnosable mental health, alcohol, and substance use problems among older adolescents in the child welfare system. Children and Youth Services Review. 2010;32:626–634. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2009.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McMillen JC, Zima BT, Scott LD, Auslander WF, Munson MR, Ollie MT, Spitznagel EL. Prevalence of psychiatric disorders among older youths in the foster care system. Journal Amer Acad of Child &Adolesc Psych. 2005;44:88–95. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000145806.24274.d2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Woods SB, Farineau HM, McWey LM. Physical health, mental health, and behaviour problems among early adolescents in foster care. Child Care Health Dev. 2012 doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2011.01357.x. [Epub ahead of print]PMID: 22329484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Horwitz SM, Hurlburt MS, Cohen SD, Zhang J, Landsverk J. Predictors of placement for children who initially remained in their homes after an investigation for abuse or neglect. Child Abuse Negl. 2011;35(3):188–98. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2010.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Leslie LK, James S, Monn A, Kauten MC, Zhang J, Aarons G. Health-Risk behaviors in young adolescents in the child welfare system. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2010;47:26–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.12.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Orton HD, Riggs PD, Libby AM. Prevalence characteristics of depression substance use in a U.S. child welfare sample. Children and Youth Services Review. 2009;31(6):649–653. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dowd K, Dolan M, Wallin J, Miller K, Biemer P, Aragon-Logan E, et al. National Survey of Child and Adolescent Well-Being II: Combined waves 1–2: Data file user’s manual restricted release version. Ithaca, NY: National Data Archive on Child Abuse and Neglect; 2011. http://www.casacolumbia.org/templates/NewsRoom.aspx?articleid=631&zoneid=51. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kann L, Kinchen S, Shanklin SL, Flint KH, Hawkins J, Harris WA, Lowry R, Olsen EO, McManus T, Chyen D, Whittle L, Taylor E, Demissie Z, Brener N, Thornton J, Moore J. Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance — United States. Division of Adolescent and School Health, National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STD and TB Prevention, CDC ICF International; Rockville, Maryland Westat, Rockville, Maryland: 2013. e ZazaS. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) [Accessed on 4/15/14];1991–2013 High School Youth Risk Behavior Survey Data. Available at http://nccd.cdc.gov/youthonline/

- 23.Brener ND, Kann L, Kinchen S, et al. Methodology of the Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System. MMWR 2013; 53 (No RR-12).26 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Methodology of the Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System – 2013. MMWR. 2013;62(1) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Achenbach TM, Rescorla LA. Manual for the ASEBA Preschool forms and Profiles. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont Department of Psychiatry; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 25.SUDAAN. Research Triangle Institute: SUDAAN User’s Manual: Release 10.0 [computer program] Research Triangle Park, NC: Research Triangle Institute; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mahalik JR, Levine Coley R, McPherran Lombardi C, Doyle Lynch A, Markowitz AJ, Jaffee SR. Changes in health-risk behaviors for males and females from early adolescence through early adulthood. Health Psychology. 2013;32:685–694. doi: 10.1037/a0031658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Joe S, Baser RE, Breeden G, Neighbors HW, Jackson JS. Prevalence of and risk factors for lifetime suicide attenpts among blacks in the United States. JAMA. 2006;296:2112–2123. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.17.2112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gibbs JT. African-American suicide: a cultural paradox. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 1997 Spring;27(1):68–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chartier MJ, Walker JR, Naimark B. Health-Risk Behaviors and Mental Health Problems as Mediators of the Relationship Between Childhood Abuse and Adult Health. American Journal of Public Health. 2009;99:847–854. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.122408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Katon W, Richardson L, Russo J, McCarty CA, Rockhill C, McCauley E, Richards J, Grossman DC. Depressive symptoms in adolescence: the association with multiple health-risk behaviors. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2010;32(3):233–239. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2010.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miller AB, Esposito-Smythers C, Weismoore JT, Renshaw KD. The relationship between child maltreatment and adolescent suicidal behavior: A systematic review and critical examination of the literature. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 2013;16:146–172. doi: 10.1007/s10567-013-0131-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stein REK, Hurlburt MS, Heneghan AM, Zhang J, Rolls-Reutz J, Landsverk J, Horwitz SM. Health status and type of out-of-home placement: Informal kinship care in an investigated sample. Academic Pediatrics. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2014.04.002. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) [Accessed 8/1/14];Trends in the Prevalence of Tobacco Use National YRBS: 1991—2013. http://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/yrbs/pdf/trends/us_tobacco_trend_yrbs.pdf.

- 34.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) [Accessed 8/1/14];Trends in the Prevalence of Sexual Behaviors and HIV Testing National YRBS: 1991—2013. http://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/yrbs/pdf/trends/us_sexual_trend_yrbs.pdf.

- 35.Tourangeau R, Smith TW. Asking sensitive questions: The impact of data collection mode, question format, and question content. Public Opinion Quart. 1996;60:275–304. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Institute of Medicine and National Research Council. Children’s Health, the Nation’s Wealth: Assessing and Improving Child Health. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]; Institute of Medicine and National Research Council. Child and Adolescent Health and Health Care Quality: Measuring What Matters. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dube S, Anda R, Felitti V, Chapman D, Williamson D, Giles W. Childhood abuse, household dysfunction, and the risk of attempted suicide throughout the life span: findings from the Adverse Childhood Experiences study. JAMA. 2001;286:3089–3096. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.24.3089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chapman DP, Whitfield CL, Felitti VJ, Dube SR, Edwards VJ, Anda RF. Adverse childhood experiences and the risk of depressive disorders in adulthood. J Affect Disord. 2004;82:217–25. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2003.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Romens SE, McDonald J, Svaren J, Pollak SD. Associations Between Early Life Stress and Gene Methylation in Children. Child Development. 2014;00:1–7. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12270. (2014) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]